Danny Dorling's Blog, page 36

January 24, 2017

Theresa May’s Industrial Strategy must work for Sheffield, the city of low pay

The Prime Minister has launched her much-vaunted industrial strategy. The measure of its success has to be whether it works for cities like Sheffield and the rest of the North.

The Resolution Foundation released a report last week which found that incomes in Sheffield have not recovered, and nor grown, nine years on from the financial crash. Sheffield is now the lowest paid city in the UK.

But there is stark inequality within and not just between our great cities. Eight years ago, A Tale of Two Cities was released which shone a light on that inequality. You can track the route of the 83 bus from one of the seven hills that Sheffield sits on through the city centre to one of the poorest wards. In just 40 minutes life expectancy falls by 10 years.

But similar bus routes which match inequality can be found all over the country. These journeys highlight how Britain has divided over the last three decades. If you ride these routes you see the signs of an economic model which has unquestionably failed us all. Many people at the wealthier end of the routes are now no longer doing well. In particular, affluent elderly residents also suffer when health and social care fails. The young are reporting lost hope in our future with 2017 revealing the worse ever outcomes reported in an annual survey of their prospects.

Read more in the Yorkshire Post

Illustration by Joseph P Kelly

January 20, 2017

Housing crisis grows – first fall in home movers for five years

On January 20th 2017 the BBC announced the first fall in the numbers of people moving home in the last five years. The reason was the growing housing crisis.

Last year I gave a talk in Manchester about the housing crisis and how and why I thought it was growing in importance then. Because of the location of building in which the talk was held, it began with a historical diversion: “160 years ago, that’s only your great great great grand parents’ time ago, this city of Manchester had a housing crisis.

On this exact spot – or more likely a floor below us – people were living in jerry built housing that was so bad that life expectancy fell below 25 years. The reason for this crisis was immigration. So yes immigration can cause a housing crisis; although not the one that we have at present.

In the 1840s Manchester was sucking people into its mills, many fleeing from famine in Ireland. Combine this with badly built housing and you have a housing crisis, the same kind of crisis that is happening in slums and shanty towns around the poor world now. Manchester did this first. But our current housing crisis has nothing to do with immigration”

read more from that ‘Housing Crisis’ talk;

… or listen to a recent interview that took place on BBC Radio 2:

…or see here for a book published a couple of years ago on why the crisis was coming and what could be done when it hits.

January 19, 2017

Migration, Europe, bias in research, health, education and housing

It’s remarkable how little research is available comparing the success of different countries’ immigration policies. This is partly because it is such a delicate topic, and partly because there are so many different criteria to judge what makes a successful policy. If the criterion is simply to keep people out, North Korea has the best policies.

Despite what some tabloid newspaper writers might think, it is generally good news if you live in a place where immigrants keep turning up. Affluent countries that have attracted high numbers of immigrants tend to be socially successful countries. The best countries for immigration are not only welcoming to immigrants but are also worth staying in, in that they have affordable housing and transport, good public education and healthcare, and jobs that are well paid.

read more here – a series of interviews given recently to the website “The Question”.

Or listen here to a talk about how living and working in the most economically unequal country in Europe may effect how we work and think, and then what we produce, as researchers working in the UK today:

January 4, 2017

House prices in London are falling

In mid-December the Land Registry revealed its latest data on housing prices. These showed that average prices had fallen in five London boroughs in October, up from three in September and just one borough in August. The largest fall, in Kensington and Chelsea, was almost 5 per cent.

Across all of London, prices fell by 1.2 per cent in October, the largest monthly fall recorded since 2011. The Evening Standard reported the story with a reassuring quote from an estate agent saying that: “The industry will really start to stutter to a halt as Christmas approaches, so any panic over falling house prices should be taken with a pinch of salt.” However, another estate agent broke ranks to say that sale volumes were now “critically low.”

An even more dramatic story emerged on 22nd December, with Yahoo reporting: “House prices in parts of central London have collapsed by as much as 13 per cent over the last year, according to new figures from property consultancy and advisory Knight Frank.” This one was illustrated by a three-dimensional map of the capital showing the central boroughs sinking beneath the river Thames. But again there was a semi-reassuring quote suggesting the falls would “bottom out” in 2017, with a rider about political uncertainty.

How did the government react to these events? It re-released details of a scheme it had first announced two years ago to provide some funding to allow more private building on brown field sites and a few “garden villages” all of which is in jeopardy with the fall in housing prices spread out from the capital as they have tended to do in the past. Falling prices make housing more affordable, but they also make solutions to the housing crisis based on ‘nudging’ the private market far less likely to work.

For a discussion of these issues on BBC Radio 2 listen here:

or read more – Prospect Magazine Blog, January 4th 2017 or a lot more on the housing crisis in “All That is Solid”

December 23, 2016

Review of Utopia by Thomas More, introduced by China Miéville and concluded by Ursula Le Guin

In 1968 Ursula Le Guin wrote the Wizard of Earthsea for me. I knew it, as I am sure thousands of other children also knew. I felt my imagination grow and my horizons expand. I saw myself in her story. Utopia is about imagination, how hard it is to imagine, but what imagination can achieve. So place Thomas More’s story between the words of two living fiction writers and you imagine something new.

“Utopianism isn’t hope, still less optimism: it is need, and it is desire” declares China Miéville in the opening essay of Verso’s quincentenary edition of Utopia. Then, with little hope, and even less optimism he begins a second essay title ‘the limits to Utopia’ with the recent report (part-funded by NASA, no less) that warned of the imminent collapse of global civilization resulting from the climate change that is coming; an immanent collapse that our unleashing of corporate monsters will make ‘difficult to avoid’.

This December marks 500 years since Thomas More’s wonder. An idea sparked in his mind by the voyages of the The Santa María, Niña and Pinta – tiny ships, no bigger than modern spaceship capsules, and named after saints and a girl. Five hundred years separate’s those voyages from the Apollo missions and the doomed Schiaparelli Mars Lander that crashed into the dust of the red planet on the anniversary of the first publication of More’s utopian dreams.

Today, in vessels named after ancient Greek (and Roman) gods and Victorian (Italian) astronomers, we no longer discover new worlds, but crash into dead red ones, as if desperately seeking an escape from the planet we are currently destroying.

Utopia can be toxic. We live in a profit-maximizing world in which it is rational “…for the institutions of our status quo to do what they do”. Profit-maximization was once someone’s utopian dream, someone Euclidean rationality. Many now dream of a better world, but often only after the apocalypse to come, and there are as many versions of that apocalypse to choose between as there are Utopias.

Thomas More’s Utopia consisted of magnificent houses that were three stories high, with glazed glass windows for all. People living in them wear “the same sort of clothes, without any distinction except what is necessary to distinguish the two sexes…”. We are living in that particular Utopia today. Our parents did not. They, and all their forebears back at least to More’s time, had stricter uniforms and traditions.

Look at our clothes today, look at our homes today, read the words from half a millennia ago and wonder how, in less than half a century, we have changed so much that what was More’s utopian vision is now, for many, reality. People today have many trades, they have some democracy and yet we are still burning up our planet and have unleashed the suited and booted corporate mad men upon ourselves. Where did they come from?

“Utopia has been Euclidean, it has been European, and it has been masculine”, concludes Ursula Le Guin in the essay that follows More’s story in this 500-year reappraisal. And she is right. The utopia that is now home to so much of humanity, living in multi-story dwellings, all wearing the same sort of clothes, is of Europe spread worldwide, it is of world of straight lines and perfect solids.

For Ursula Le Guin the many century voyage to Utopia passes by Copernicus learning that the earth is not the centre, through Darwin’s realisation that man is not either, to some place new. Imagination, she says, is our escape route. “It has no place in the vocabulary of profit making”. Earthsea was a children’s story set in an imaginary archipelagos of islands, a place of many possibilities. Reprinting Utopia between contemporary stories succeeds because its stretches our imaginations to further shores, in search of the farthest shore.

Utopia by Thomas More, Verso 2016 edition

December 22, 2016

Don’t mention this around the Christmas table: Brexit, inequality and the demographic divide

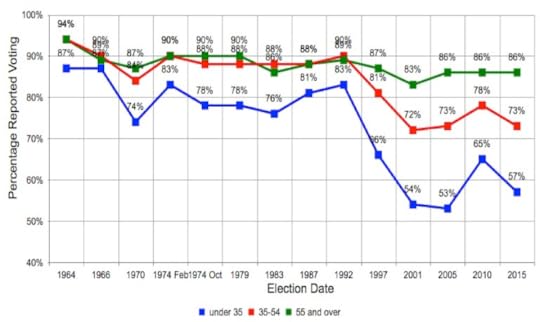

Brexit voting patterns appear to divide along the lines of age (above all else), then by social attitudes, and then by education, with older, socially conservative and less well-educated voters more likely to vote to leave the EU than younger, socially liberal and more educated voters.

However, a large proportion of votes to leave the EU might be understood to be a visceral reaction from those who have felt increasingly powerless as a result of globalisation, widening economic inequalities and a failure of successive UK government administrations to redistribute income and wealth more equitably for more than thirty, almost forty, years.

This is a reaction that it is easier to have if you are old enough to remember more equitable times, when it was possible to find a home and start a family in your twenties or early thirties and when full employment was a reality.

Since the early 1990s fewer younger adults have voted in UK general elections. That trend coincided with the rise of individualism among the young as they were taught more and more that their futures depended on their own individual efforts. We should not have been surprised that fewer younger than older people voted in the 2016 Brexit referendum in the UK.

Voting by age group in the UK 1964 to 2015

December 21, 2016

The Creation of Inequality: Myths of Potential and Ability

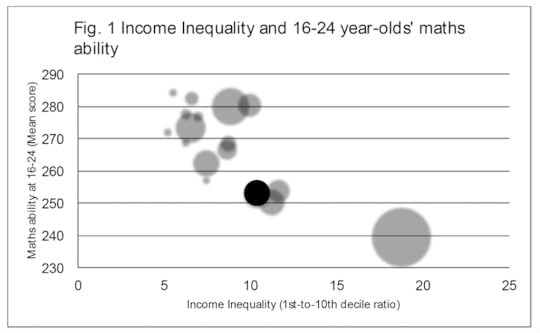

The old myth about the ability and variability of potential in children is a comforting myth, especially for those who are uneasy with the degree of inequality they see and would rather seek to justify it than confront it.

The myth of inherent potential helps some explain to themselves why they are privileged. Extend the myth to believe in inherited ability and some can come to believe that their children will inherit part of a greater potential.

These beliefs create and sustain inequality in society and allow for the creation of levels of ignorance in populations. This article uses insights from social geography and the sociology of education to examine how the myths are sustained past and present.

It notes that countries with the highest degree of income inequality and the most unequal education systems have the worst outcomes for young adults, and these are the countries in which eugenic notions of inherited ability are resurfacing.

Maths ability for those aged 16 to 24 in 2012

December 15, 2016

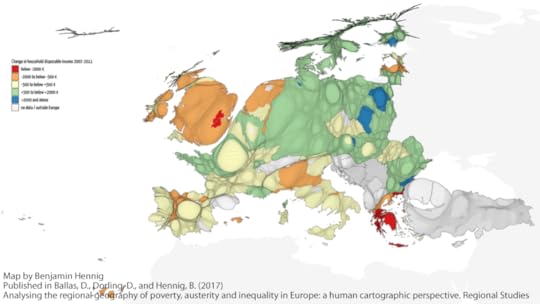

Analysing the regional geography of poverty, austerity and inequality in Europe

This paper presents a human cartographic approach to the analysis of the impact of austerity and the economic crisis across Europe’s regions.

First, the paper reflects on past insights and debates on the analysis and mapping of poverty and wealth and of the effects of austerity in particular. It then presents and discusses a wide range of cartograms and maps (including the subjects of unemployment and poverty as well as related themes such as educational attainment and migration).

These images highlight social and spatial inequalities and also illustrate that the most severe social divides within Europe are more often within states rather than between them. To that end the paper also argues the case for a co-ordination of urban, regional, national and European policies and EU spending to ameliorate the impacts of austerity and to enhance social and territorial cohesion.

Finally, the paper highlights the increasingly important role of geographers and of the field of Regional Studies in so many recent debates about the future of the European project and of the possibility of a Europe of cities and regions rather than a Europe of nation-states.

Figure A.7: Change in household disposable income 2007-2011

In straitened circumstances: A review of Austerity Blues

The Left are busy looking back instead of devising laws to address inequalities.

Four decades ago The City University of New York charged no tuition fees, and all its students were taught by full-time staff. Today, fees cover half of all teaching costs and half of professors are part-timers. At Arizona State University, Michael Crow, the president, who is ridiculed throughout this angry, sometimes despondent and frequently eye-opening book, has proclaimed himself a “knowledge enterprise architect” – a sure sign that we are entering the end times.

Like bank robbers of old, investors turn to students “because that is where the money is”. The banks no longer have money in their vaults. The vaults are empty; the money has already been lent many times over. Today, if you want to make money, you prey on the hopes and dreams of the young. Lend them their tuition fees, pay them as little as possible as they work part time while studying, and fail more black and poor students than you used to, so that they have to try, and pay, again and again. Be sure to exploit your own children less.

The Left and Right have swapped roles. Now the Right describes itself, however mendaciously, as progressive, and on the side of working people. The Left harks back to earlier days, aiming to conserve what was previously achieved as it laments the passing of time. In the US, the Right complains of low completion rates and soaring tuition costs. It blames a lack of corporate entrepreneurship in the management of public universities, arguing that it would ensure competition, drive down costs and drive out inefficient professionals.

The UK and USA tax too lowly and spend too little on the public good, but to reverse that takes planning:

Public Spending in proportion to GDP in twelve rich countries

Source: Figure 2 from “A Better Politics”

Those on the Left have to stop complaining and start planning. Planning for when the bankruptcies begin and the debt is not repaid, and for when Ohio State’s parking lots are needed for a better purpose than parking cars. What should we be dreaming for now? It cannot simply be a return to conserving the past. What laws need to be rewritten to take back control?

We can wait until the system breaks, until the credit ratings of entire countries (such as the US and UK) are downgraded as it is realised that their student debt cannot be repaid, or can only be repaid by increasing other debts, such as in housing. Or we can point out now to “investors” that the risk they are taking is higher than they think and watch them pull out. This book describes the problems, but if we are to save the soul of higher education, we need to offer more solutions.

Austerity Blues: Fighting for the Soul of Public Higher Education

By Michael Fabricant and Stephen Brier

Johns Hopkins University Press, 320pp, £22.00

ISBN 9781421420677

Published 29 November 2016

December 13, 2016

Geography, Health, Austerity and Europe – where next for the countries of the UK?

Public Lecture given by Danny Dorling at the University of Swansea, December 12th 2016. Co-hosted by the Department of Geography and The Regional Collaboration for Health, a partnership between Swansea University, ABMU and Hywel Dda University Health Boards.

Some points made during the lecture included:

When it comes to NHS health spending and provision, choices over taxation, education, housing and wealth we would do well to look to France. France is no Utopia, but compared with the UK, it has six more doctors to treat every 10,000 patients (21% more per person), 35 more hospital beds per 10,000 people (130% more per person), and people stay in hospital for less time on average (5.6 days instead of 6.9 days). The productivity of those in work is higher partly because health is better and people are not forced into low paid employment. There is a clear and present danger that leading French politicians will seek to portray their country as a failing state in the race for votes in 2017. But if that can be avoided then we should not assume that the inequality and poor health that helped get Brexit over the line and Trump into power will necessarily play out that way in France. Facts, and how they are presented, will matter more than ever before.

Really taking back control means:

.Taxing at the normal European level

.Spending on education & health normally

.Having housing laws that are fair to tenants

.Working towards a basic income for all

.No sanctions and student loans for the young

.Introducing a fair system of voting (PR)

.Not allowing the 1% who take a 7th of everything every year in the UK – to also run political parties, newspapers, companies, even university building programmes unchallenged. This is best done by reducing their income/wealth – and that can be done in many ways – which they are aware of.

Read more here (free low resolution PDF)

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers