Danny Dorling's Blog

November 23, 2025

The BBC, inequality, and the Multi-Coloured Swap Shop

The BBC was once an engine of progressive change driving British society to greater equality – Danny Dorling asks what changed, and why?

This article makes an unconventional argument, that the BBC was pro-egalitarian until the late 1970s and then a less benign dominance took hold. Slowly at first, but later that new dominance grew to have a negative influence over British culture, politics, and economics.

Using the BBC’s commissioned children’s television shows by way of playful example – which might mean more to the older reader – I argue that in the 1930s, the last time the UK was as economically unequal as it is today, many social engines were pushing British society towards greater equality.

From 1922, and for at least half a century, inequality in income fell every year, until around the advent of the Multi-Coloured Swap Shop in 1976 – coincidence, not cause. Class divides tumbled and we began to better understand each other.

However, in more recent decades, our increasingly London-centric media has more often provided excuses for trying to explain away huge inequalities as if they were inevitable. This has led to the current impasse whereby, as Adam Bienkov wrote in Byline Times: “…the BBC continues down its recent path of seeking to appease and co-opt the very forces whose political and commercial interests demand its destruction.”

Engines of Equality

The BBC has always been a London institution. London was home to 7.5 million people in 1921, roughly a fifth of the then population of England and Wales. A million fewer lived there by 1981, and nearer to just one in eight as a proportion. The national populations were rising, London was shrinking. However, by 2021, the census recorded the capital’s population at nearly 8.9 million; a proportional rise as well as an absolute one, to one in six people in England and Wales.

This demographic trend reflected many other changes; not least the fall and rise in national economic inequality – which today is again at a high peak. When inequality fell nationally, that was not because London depopulated, but because arguments for greater social justice were often made effectively, if not always overtly, by people and institutions in London.

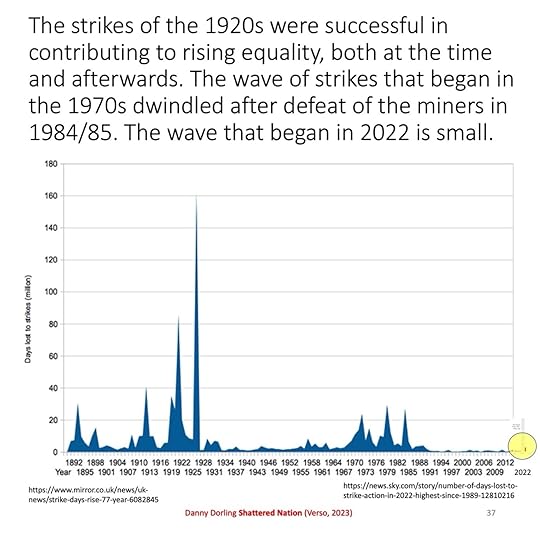

Figure 1: Days lost to strikes in Britain 1880s to 2020s

Many separate but connected engines of equality fired up in 1922. Northern Ireland was less than a year old, having been created by the British Government when it partitioned the island of Ireland. A revolution in Russia had concentrated the minds of the British upper classes. The recently-founded Labour Party was in disarray (not unlike today). New higher levels of taxation had been required to pay for war, and those new taxes had begun to eat away at the wealth of aristocracy. Strikes abounded, far more than at any other time in British history, (see Figure 1). The world, and especially Britain, was changing rapidly – turning towards great equality. The huge drop in strikes after the 1920s and 30s is partly testament to changes in national sentiment, often led by people in or near London – John Maynard Keynes in the 30s and William Beveridge in the 40s come to mind.

Culture and media in Britain were moving from theatre and newspaper to broadcasting and radio. London was the centre and at the centre of London was the BBC.

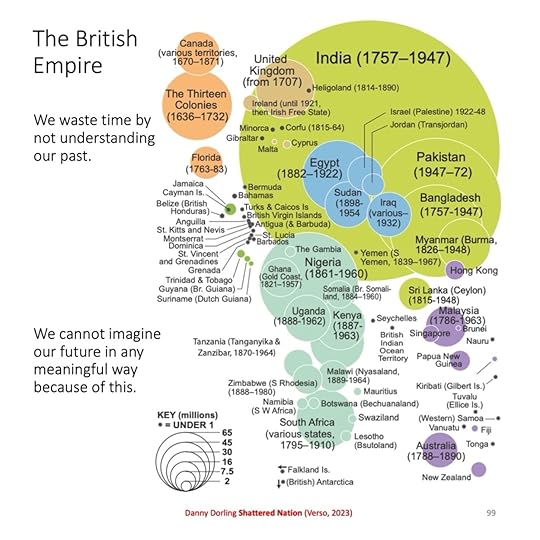

The young men and women that the BBC relied upon back then are often portrayed as ‘stuffy’ today – but they were a part of the generation that had seen their parents and grandparents take Britain into two World Wars, and lament the loss of a London-centred empire; an empire that more and more progressive young people would realise was coming to an end (Figure 2). The most progressive realised it could not be justified.

When the British Broadcasting Corporation was born, it was the mouthpiece of an empire which still looked like Figure 2, bar the thirteen colonies (which had become the USA) and a few other mostly white places. The BBC staff were often technically able and often very young. They also included many at the forefront of much of the new thinking that was emerging out of the 1914-1918 ‘war to end all wars’. However, they were also regularly vetted to ensure their political views were ‘sound’.

Figure 2: The maximum extent of the British empire

Many of the men who first worked at the BBC had fought alongside others who they would not normally have seen as equals. They were influenced by new thinking. Two young men, both born in Calcutta and Exeter respectively, met as boys at Rugby school just before the century turned: R. H. Tawney and William Temple. Tawney would go on to have great influence at this time on our understanding of political and economic history, and William became chair of the General Advisory Council of the BBC in the 1930s. When economic and social inequalities last fell in the UK, a part of what made that happen were the changing views of the younger members of the British upper classes.

A third young man Tawney and Temple met at Balliol College, Oxford, was William Beveridge. A product of empire, born in Rangpur (in what is now Bangladesh), he famously helped usher in the welfare state. One of Beveridge’s key advisors was the son of Joseph Rowntree; Beveridge’s assistant was Harold Wilson. These were the generation that most influenced the thoughts of those who first worked in the BBC, alongside a grudging but growing understanding that, in future, far fewer posts of influence would be held entirely exclusively by men.

Behind the scenes, more women were employed. In contrast, it was the print media that most remained the bastion of men. With hindsight, it was unsurprising that the London-based BBC became one of the more positive parts of the engine for increasing equality.

When you broadcast, your message cannot be separated so that only a few can hear it. You cannot overtly tell your listeners that most of them are beneath you. Broadcasting was, by definition, broad. A universal service was created; the same information being made available to all – although it came from London.

It was in promoting universality that the London-centred BBC was most obviously an engine for increasing equality. The printed press produced papers aimed at different social classes and nothing for the large numbers of adults that were still illiterate. But the voices emanating from the wireless could be understood by all. Although initially only a few could afford a wireless.

The BBC had to talk on everyone’s level, it also began to develop a Reithian creed to disseminate “All that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement. [where] The preservation of a high moral tone is obviously of paramount importance”. Of course, one man’s idea of what is best differs from another, as do views of which morals are high. But it is worth remembering London’s past contributions to progress and not seeing the capital as trying to hold change back.

It may seem odd to refer to the early work within London of the BBC as progressive but, for its times, it was. On 2 November 1936 the first BBC television broadcast was made. Those stilted announcements in Received Pronunciation English, read by a man in a dinner jacket, were talking to people while looking them in the eye and knowing that they too were looking back at him, albeit through the screen. At first, the announcers knew that it was only the most affluent who could purchase a television set and live within range of Alexandra Palace, to view those first flickering images. Nevertheless, the founding principal of the BBC was a dedication to giving everyone the same high-quality information and entertainment.

There was propaganda too of course. Television came to Britain on 22 March 1935, after having arrived in Germany a year earlier (via the USA, where broadcasting had begun in 1928). A television service was seen as vital so that the home population could be spoken to directly.

Those in the know knew that war was coming again. It had already begun in Spain. In 1936 in Catalonia, George Orwell wrote that: “Waiters and shop-workers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared.” In 1938, when Homage to Catalonia was published, the young men and women at the BBC would read Orwell’s words. And then they too would go to war. His words and thoughts also reflected and helped form the new thinking in London in the 1930s and 40s.

The wireless programs and television broadcasts from London were innovative. Woman’s Hour was first broadcast in 1923. Listen With Mother was introduced in 1950. This was a shift away from talking to largely upper class women, the first female listeners who could afford a wireless. This shift was towards instead conversing with many more mothers and children. The Second World War accelerated many other cultural trends, and again this acceleration was often from London and its satellite cities.

Adult comedy arrived and was almost instantly subversive. Beyond Our Ken aired on radio from 1958-1964. It parodied the politicians, politics, and the stuffy culture of the day. Round The Horn was satire broadcast on BBC radio between 1965 and 1968. Monty Python’s Flying Circus was aired from 1969 onwards.

All this was unimaginable when the BBC began in 1922. But this was 1960s London.

The most subversive of all, the greatest engine of equality, was children’s television. Imports of 1930s Micky Mouse cartoons began to be replaced by home grown creations during the corporation’s second quarter century. Muffin the Mule in 1946. But there was quickly more, much more. What began as the Railway Series, in 1953, become Thomas and Friends. Again, some of the nastier elements of the children’s books the series was based on were tempered. The Referend Awdry, who had created Thomas the Tank Engine, although a pacifist, had some issues which the early BBC smoothed over.

Blue Peter began in 1958. Named after the signal flag for the letter P that in Britain had been hoisted, ever since 1802, once a merchant vessel is ready to sail (from London docks mostly in those early years of the nineteenth century). Thus, the new flagship children’s programme began with an image of Britain’s great nautical past – two years after the Suez Crisis, and the loss of all British naval control East of Eden. Within a decade, the London docks were closed, and we children who grew up ready to sail into the world were making do with toilet rolls and sticky-backed-plastic – imported through other means.

The 1960s were the BBC’s and London’s most innovative decade. Planes, trains, ships and automobiles – all symbols of industrial prowess – featured often in the early children’s programming of the BBC. But less so in Play School (1964), The Magic Roundabout (1965-1977), Jackanory (1965), or Camberwick Green (in colour in 1966) which starred a fire engine and a set of workers from that most working class of all the public services – the fire service. Most importantly, in terms of discussing inequality, opportunity and the future of the British capital, all the key cultural and political decisions to put out this socially more equalizing propaganda were being made in London.

Camberwick Green

Pugh, Pugh, Barney McGrew, Cuthbert, Dibble and Grub might have loyally rescued cats stuck up trees in a fictional middle England village, but they did so through to the advent of the first national pay strike by fire workers in November 1977. Although the children’s show never featured a strike.

Nevertheless, it was subversive because it presented all the people of the village as being of equal worth. They might have known their function, and almost all of them were men, but there was no squire in the village, no boss, no big house on the hill, just a windmill that was useful for grinding flour.

Dr Mopp was no more important than Peter the Postman; Windy Miller was on the same level as Mr Crockett the Garage Man. Roger Varley the Sweep did not have to look up to PC McGarry (or down on him); Mr Dagenham the Salesman, Mr Carraway the Fishmonger, and Mickey Murphy the Baker were friends. Mrs Honeyman and her baby (introduced on 28 March 1966) were concerned about the inequitable distribution of childcare.

It was from London that this story was piped out to the airwaves; 1960s London. The times, they were a-changing, and the BBC was helping to change them, reflecting London upper-middle-class thinking of the day.

This was my BBC, the programmes I saw as a child. The BBC had softened the Tank Engine tales to be suitable for the new times. Bolshie the Bus was still named after the Bolsheviks (the bus approved of strikes). However, the Fat Controller was no longer presented as someone to aspire to be. Far better, a working-class workaday hero, like Thomas.

It was not just ‘loony-left’ councils and the Inner London Educational Authority that were decades ahead of their time – the London mainstream was, including the BBC.

We each have our own favourites, and they very much depend on our age. From 1969 to 1973 I avidly followed the Clangers on BBC1. I had seen the moon landing live. I understood every word that the soup dragon said, although I didn’t know that the Clangers, when whistling, were actually ‘swearing their little heads off’. Nevertheless, I got the gist. The joy, and the sentiment.

But what did John Reith and his now old generation make of all this? Reith died in 1971. In 1975 a series of excerpts were published from his diaries which suggested he would not have approved.

The BBC content was becoming ever more progressive despite the frowns of a few – Britain had also become the most equitable it had ever been in terms of income inequality and the speed of the breaking down of class and gender barriers. In the 1970s of all the larger European countries, only Sweden matched the UK. The BBC with its London thinking had helped drive that growth in equality.

For my parents’ generation, after Reverend Wilbert Awdry (1911-1997), the second of St Peter’s College Oxford’s most famous alumni, Ken Loach (1936-) also became a BBC star content creator. Early on much of what he created was first broadcast by the BBC. From episodes of Z-Cars (1964), and seminal films like Up the Junction (1965), Cathy Come Home (1966), Poor Cow (1967), Kes (1969), and The Price of Coal (1977), to later works such as The Wind that Shakes the Barley (2006), The Angels’ Share (2012), The Spirit of ’45 (2013), I, Daniel Blake (2016), and Sorry We Missed You (2019).

There was much more than that from Loach, and a deluge of radical television films from others. The list above is just a summary of some of his best-known material, but you won’t see these later tales told on the BBC.

It was not Loach who had changed though. It was the Beeb and sentiment in parts of London.

Loach was painted as a pariah when he explained that in his view the BBC had played an “absolutely shameless role [in] the destruction of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership” of the Labour Party. In 2023, the BBC reported how parts of the Labour party, including its leadership, now viewed appearing with Loach on stage as a reason for not allowing Jamie Driscoll to stand for political office in North East England.

What can explain this transformation of London mainstream upper-middle-class thinking, as exemplified by the BBC from progressive to regressive – at least in how Ken Loach recently describes it? Why did London start to kick down on the regions?

London changed. It gentrified. Who worked in the BBC changed. The whole of the UK became more economically inequal, so the top tenth of people, the graduates among them who had the best-chances of working at the BBC and living in central London, were now coming with the experience of being more separated from the rest of society.

Don’t be fooled by the occasional additional ‘regional accent’ or more ‘older female faces’, or a greater ethnic diversity in front of the camera (if not behind it) – to be able to be a part of the engine of culture in the country that polarized the most in all of Europe increasingly meant to have been born to life’s winners.

The views of politicians, of Secretaries of State for culture, media and sport, also weigh heavy: As Tom Mills states in his 2020 book The BBC: Myth of a Public Service “…the contemporary BBC is no more free from the influence of powerful interests than it was in the 1930s.”

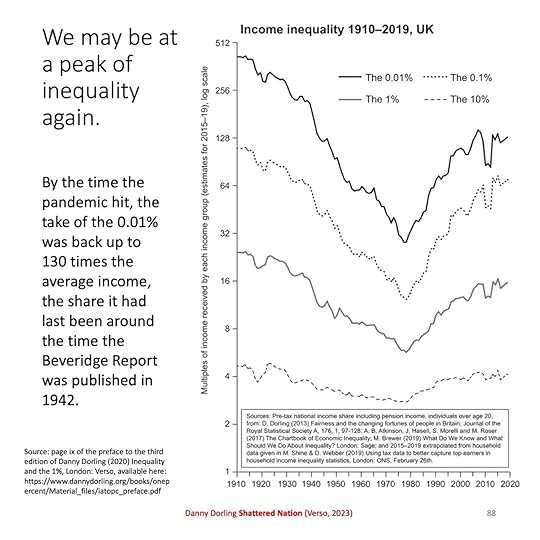

Figure 3: The long-term trend in inequality, UK 1910-2019

The graph above (Figure 3) may be helpful here. The BBC had to stay neutral and did stay neutral. It had to be impartial and remained impartial. It is just that what it meant to be neutral, to be impartial, in Britain had changed, and at its heart by income we have become ever more unequal each year after the late 1970s. So, to be neutral, if upper-middle-class London based, is to be with the folk who have more. A million-pound house became normal, for those who can influence culture the most.

The Turn towards Inequality

I did not grow up in London, but I imbibed London culture as a child through the BBC. My 1970s watching of children’s television did not include Ken Loach’s films. Instead, in 1972 I first saw Newsround. I watched Noel Edmunds and his Multi-coloured Swap Shop in 1976, but knew that Tiswas on ITV, and Sally James, was better (1974-1982). I was aged 14 in 1982. All but the most sheltered of boys knew that Sally was better than Noel. Tiswas was filmed in Birmingham, Swap Shop in London.

Grange Hill (1978-2008), filmed in London, was a valiant attempt by the BBC to try to regain ground it had begun to lose to ITV. Unfortunately, it was the only comprehensive school in Britain where no child ever said “fuck” (as some 1980s alternative comics once explained on BBC TV). I later learnt that it was required voyeurism among a great many of those who I met at university; those whose parents and been able and were willing to ‘send them private’.

For most children, Grange Hill slowly moved away from being reality television, away from being subversive and progressive, and became a series of public health announcements, strung together for the lower orders with the off-putting message: ‘just say no’ (to drugs).

London was becoming more different. The 1991 census revealed it as being the only place in the UK where a majority of adults aged 16-65 were not married. That was a part of the reason it was so progressive. But increasingly, our TV and radio was not being produced by young men and women who had a sense that much of the generation above them had got it wrong, had failed to prevent two world wars and had subjected entire continents to their racist beliefs. Programmes were no longer being scheduled by those who had a sense of urgency about the need for a more equitable future.

The various new manifestations of the General Advisory Council of the BBC were no longer chaired by people like Bishop Temple who had lived through the great social transformation. Yes, the BBC had regional outposts, wildlife filming was based in Bristol, but these were always outposts. The move to Salford was cosmetic. It implied devolution; but power, people and money were again being concentrated in London as most regional BBC offices faced cutbacks.

By 2015, the 1% in Britain were again taking a huge share of everything – more than their equivalents in any of European country. In London the 1% is nearer 10% of the population, is nearer to ‘normal’ for the creators of culture.

The British might have always been a little stuffy, but there was a time when London was breaking that tradition – long before ‘cool Britannia’.

In its early days, BBC technical ability and flair mattered as much as the old school tie. Always, as Ken (Loach) and Wilbert (Awdry) illustrated, an Oxford University background remained an advantage, and Cambridge too, especially as regards presenting the Today Programme. However, what was seen as talented, began to change. Spitting Image (1984–1996) was no match for That Was the Week That Was (1962-63), but better than what little satire came after 1996. New Labour and Cool Britannia came with less fun.

The rapid increase in income polarisation that occurred across the UK from the 1970s onwards meant that a job in the BBC became an ever more coveted aspiration for those families increasingly desperate that their offspring should stay in the top 10%. Joan Bakewell could appear on Late Night Line-up in the 1960s despite being the granddaughter of factory workers. In contrast, most of the intellectuals on screen today grew up in ‘the 10%’. This was a group that by the end of the 1980s came to take and spend 40% of all income each year in the UK. To move to London and live in London today, to work at the BBC now, usually requires a little ‘family money’.

It is well known that our actors, sports folk, and media stars are now from less economically diverse backgrounds than in our more equal past. The expense of London is one reason.

More of those on screen were women, or black, or brown, or mixed, or talked in non-received English, but that window dressing could not disguise the growing exclusivity of who now got to the top. Social mobility was now falling. The British state was moving rightwards, having only very recently seen its two main political parties swing so far to the left, competing to see which could build the most council houses each year in the 1950s and 1960s. Very few council houses were built after 1979. The state began to wither, and a part of that withering concerned the budget of the corporation.

Crackerjack, filmed initially in west and then central London, ended in December 1984, as the children of the miners looked forward to their first Christmas without enough food. Roland Rat (filmed in Camden) appeared on the BBC in 1986, just as the Conservatives enacted the Big Bang in the City of London and financiers cheered from their open windows on hearing of the top rate of tax falling to 40%. Appropriately Roland had been poached from ITV in 1985. The BBC became more commercial and less cerebral. On arriving Roland (Rat) announced ‘I saved TV-am and now I’m here to save the BBC’.

Newsround joined Grange Hill in 1986 in drawing its youngest viewers into the war against drugs. London could diversify and kept much light industry. Far away from London, when shipbuilding went, and there was little chance of a new winter coat, shoes for the wife, or a bicycle on the boy’s birthday, that heroin became so very attractive. Personal responsibility became the new order of the day.

The Radio One roadshow began in the summer of 1986, shortly after the miners had been comprehensively defeated – free entertainment for those without loads of money – coming to a beach or park somewhere you; but just for one day – and just once in your life (if you were lucky).

Playschool ended in 1988, appropriately alongside most voluntary playgroups in Britain which folded as private for-profit nurseries took over the childcare industry. It was replaced by Playbus, later Playdays, from 1988-1997. Sadly, play was going out of vogue in those dark years of high but still rising economic inequality and mass youth unemployment. But at least there were still no foodbanks. Years later the BBC, very solidly still from London, was reporting the provision of foodbanks as being positive aspects of life in northern towns.

John Craven stepped down from Newsround in 1989 to host Countryfile – rural idyll escapism with an occasional nod to struggling hill farmers.

My view of London as so dominant was formed when I moved to Newcastle upon Tyne in 1986 and stayed there for a decade. I had gone to Newcastle to study. Why Newcastle? Because of Jools and Paula. It was from the banks of the Tyne that Jools Holland and Paul Yates broadcast The Tube between 1982 and 1987. That it was broadcast on Channel 4 showed that the BBC was facing public sector competition. That Channel 4 was publicly owned showed that competition was possible without profit.

Who knew then, that in just three decades time (in 2023), the BBC would be tasked with creating an annual quota of stories from the extremities of Britain telling tales of how life on the edge was not so bad after all? Among my generation, political views today often reflect where people spent their 20s (in the 1980s and 1990s) – in bustling London and the South-East, or in the periphery where the majority of more than three million unemployed lived.

There was a sense when I was young that the turn to inequality and wealth (and poverty) concentration in London was not inevitable. The BBC, by broadcasting The Young Ones in the early to mid 1980s, demonstrated that you no longer needed to attend Oxford of Cambridge to be a success. One possible hidden message between the lines of the first appearance on screen of Rik Mayall (Manchester), Adrian Edmondson (Manchester) and Nigel Planner (Sussex and the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art) was that the cultural dominance of London was ending.

Prior to the 1980s, almost all subversive comedy on the BBC had been created by those who had first been students in the Cambridge Footlights or the Oxford Revue and lived in London. Perhaps due to the early influence of The Clangers and Camberwick Green, I believed that the world was changing and becoming more equal. As a teenager I thought that the 1980s and Mrs Thatcher (a London MP) would be only a brief aberration – I was very mistaken.

One of the writers of The Young Ones, Alexei Sayle (Garnett College, Roehampton), was even allowed to have his own series on BBC2 in the late 1980s and mid 1990s; but the UK was shifting rapidly politically rightwards in those years, and London again increased its cultural dominance.

So dominant it could move a chunk of the BBC to Salford, Greater Manchester, and produce programmes from there, as if they were made in London – can you tell the difference?

The BBC and its London message are the family you have always grown up with. You know them. They are in your living room. If you are an avid listener their words are in your ears, from the very moment when you wake in the morning to just before you go to sleep. Their stories are your stories. If you meet a BBC presenter it is difficult not to say hello, as if you have always known them. But they long ago stopped being the working parts of an engine of equality and became slowly, but certainly by today, chief apologists for and advocates of an economic logic of rising inequality.

There was nothing deliberate in this. Nothing was planned. It was not a conspiracy. All that happened is that they – the presenters, producers, writers, editors, advisors, heads of programming, trustees, board members, the entire machinery – tried to stay in the middle. And the middle moved.

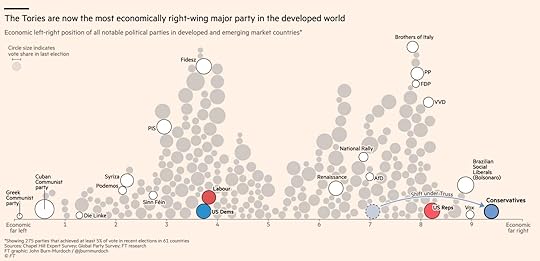

The middle in the UK moved far further to the political right in the last four decades than it has done in any other state in the world (according to analysis published in the FT) [see directly below]. At the very heart of this shift were changes that look place within London. They are most obvious in terms of the cultural changes and have been illustrated here using the BBC as an example.

It is possible that today we are beginning to see a change around again. But if it happens it will be evident in what an institution such as the BBC in London does and says. As I write, in November 2025, the key issues is how will the BBC, and the UK as a whole, stand up to Donald Trump? Or will it decide that it should be impartial, and to be impartial means to grovel?

Biographical note: Danny Dorling is a professor in the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford, and a Fellow of St Peter’s College. He is a patron of RoadPeace. Comprehensive Future, and Heeley City Farm. In his spare time, he makes sandcastles.

For where this article was originally published and a PDF copy, click here.

John Burn-Murdoch (2022) The Tories have become unmoored from the British people, The Financial Times, September 30th 2022:

Which parties are most left and right wing economically worldwide

Camberwick Green, a haven of social equality. Photo: Moviestore Collection/Alamy

October 29, 2025

Playing chicken with voters

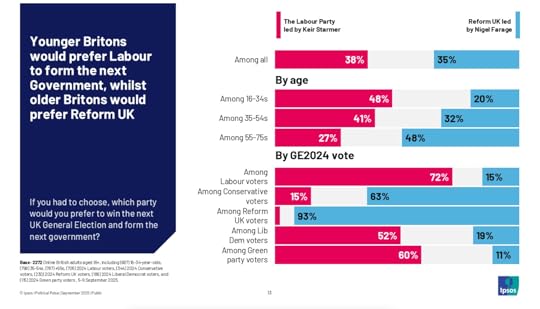

In September 2025, the British Election Study (BES) team released the latest results of a continuous survey of voters. What they were interested in was the decline in support for the Labour Party since the General Election of 2024. A year on from that election, support for the party of government had plummeted. The team summarized this thus: “Labour’s support has splintered into mostly indecision or left-liberal parties, but they’ve also lost their few right-wing voters.”1 For as long as it had been carrying out these post-election polls, a drop in support of such magnitude in such a short space of time had not been recorded previously. It is fair to say that the current volatility is unprecedented.

Half of those who had voted for Labour in the General Election of 2024 said that they would not have done so again if there had been an election in early summer 2025. The first figure here summarizes the changes and also helps to explain why political party strategists in Britain may be making certain assumptions that it could be dangerous to make. To understand that we have to look through the latest voting swings in some detail.

James David Griffiths, Ed Fieldhouse, Jane Green, and Stuart Perrett, ‘Looking for Labour’s lost voters’, The British Election Study, 3 September 2025

James David Griffiths, Ed Fieldhouse, Jane Green, and Stuart Perrett, ‘Looking for Labour’s lost voters’, The British Election Study, 3 September 2025.

First, look at how the 2024 Labour support has split and where so much of it has gone to. Losing the goodwill of half of your supporters is very hard to do in such a short time. One way of trying to understand why support fell away so fast is to consider the direction of where it went to. No other political party suddenly appeared to be a wonderful new home to head for. Most people who said they would no longer definitely vote for Labour ticked that they no longer knew how they would vote or had become undecided. However, despite the “Don’t Knows” receiving so many Labour votes, the size of that group did not grow overall. The next two largest groups headed to the Greens and the Liberals, but they were small groups of voters, just as small as was the group of Labour voters who said that they would now vote for Reform. The swings in votes thus displayed the effect of disillusionment, not a rush to one alternative.

Second, look at the Liberal Democrats. Their net support hardly changed at all over the course of this most recent year. That was despite that party also losing the loyalty of almost half the people who had voted for them in 2024! British voters are increasingly fickle; loyalties are easily switched, making predicting the future a much more dangerous game than it was in the past.

Third, look at all the minor parties: the SNP, Plaid, Greens and others; these are the next groups shown directly below the Liberals in the diagram. The nationalist voters were the only groups that tended to stay loyal. Nationalism, the hope for independence in Scotland and Wales, is a long game. The SNP had also done badly in 2024, so were holding on to their most loyal voters. In contrast, the Greens had done well but did not lose much support and grew in strength because of defections from Labour. In contrast again, the votes for other very minor parties splintered but the others picked up just as many from elsewhere and so remained tiny but persisting. All these polls were taken before a “left party” (that has yet to choose its actual name) was haphazardly formed in the autumn of 2025. The temptation to form a “left party” is more obvious when you consider just how volatile voters were becoming. It is easy to see why later national polls suggest that as many as one in five voters might at some points consider voting for such a party,2 and also why that proportion could crumble a few weeks later at the chaotic formation of that party. It might just as easily rise up again in future.

Fourth, please pay the most attention to the grey “Don’t Know” block. People do not like saying that they do not know, and so far fewer said they did not know than actually did not know or could not be bothered to vote in the 2024 general election. Because of this, when you look at the grey bars in the figure above, try to think of them as being representative of a far greater group of people than are implied by the figure. That group gained most from Labour and lost most to Reform. Voters almost never move from Labour directly to Reform.

Fifth: Reform – the light blue/cyan, chunk of voters that has doubled in size in such a short time. Reform did this firstly by losing hardly any of the supporters they had in 2024, secondly by picking up a large chunk of Conservative voters, and thirdly by taking a sizable number of Don’t Knows. I labour these facts as some strategists assume that because these silos are where the support has come from, most of the growing strength of Reform is limited, “capped” by the availability of people from these positions. That would be foolhardy to assume, not least because the “Don’t Know” pool remains just as large as it was before, and is in reality larger than surveys imply.

Sixth, and last, spare a thought for the Conservatives. Despite seeing their support fall to an unprecedented low in 2024, they managed to lose almost half of those supporters again in the space of around a year! Note also that although they lost the most to Reform, they also lost a sizable number to the now newly undecided. The Conservative Party is a very old party and remains the official opposition. Unlike Reform, it has a party structure, proper local branches, and a history. Nevertheless, it is in dire straits.

One view is that it looks increasingly likely that the next general election will be a two-horse race between Labour and Reform. People who would like to vote Liberal where Labour has won before will have to vote Labour if they want to ensure that Nigel Farage’s party does not secure an outright majority. The same applies for almost everyone who normally votes Green, except the few Greens that now live in seats with a Green MP. This view suggests that the better Reform performs in the opinion polls in future, the more likely it is that on the day a volatile electorate holds its nose and votes for the party of government, even if they very much do not like this government, to avoid something much worse. If that were to happen, it would require a high turnout from the young in particular, who already most dislike Reform and the racism associated with that party. The second diagram shown in this piece was taken from a report of polling in September 2025.3

So, what is the greatest danger? It could be in making the assumed 2029 general election already a perceived two-way fight between two parties; then support for Reform is further bolstered in the coming years. The danger is that Labour strategists continue to take the issues that Reform voters appear to care most about and try to pander to them, so as to try to hold on to the 27% of voters aged 55–75 years (see the diagram) who they might assume they are most likely to lose in future because of the average and typical views of people of those ages. But that 27% will not be like so many other older people. The greatest danger (I worry) is that in doing so they disillusion more and more of what remains of their existing support, especially among the old loyalists, and do not inspire younger people, who are most likely to be ambivalent, to vote for them.

Ipsos, ‘Britons split on whether they would prefer Labour or Reform UK to win the next election’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 28 September 2025

Ipsos, ‘Britons split on whether they would prefer Labour or Reform UK to win the next election’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 28 September 2025.

Imagine the changes that occur between 2024 and 2025 happening again and again in the three years to come. Those years cannot be as volatile again with as much movement, as that is almost impossible. However, they do not need to be as volatile to be devastating. Imagine a muted continuation of these swings. The Labour vote continues to fall, Reform continues to rise, but at the same time both expressed support for other parties and people willing to say they “Don’t Know” grows. A huge amount changes week by week and month by month in politics. But if what is currently occurring continues, then the hope of a positive change will falter further.

We are in a game of “chicken.” It is a stupid game to play. An alternative would be to try far harder to reduce support for Reform now, rather than assume that the volatile electorate will do “the right thing” on the day.

References

1 James David Griffiths, Ed Fieldhouse, Jane Green, and Stuart Perrett, ‘Looking for Labour’s lost voters’, The British Election Study, 3 September 2025.https://www.britishelectionstudy.com/...

2 Ipsos, ‘One in five Britons would consider voting for a new left-wing party, rising to one in three young people and Labour voters’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 20 August 2025. https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/one-five-...

3 Ipsos, ‘Britons split on whether they would prefer Labour or Reform UK to win the next election’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 28 September 2025. https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/britons-s...

For where this article was originally published and a PDF of it click here.

August 29, 2025

Born to Rule is a fascinating book, with only a few small...

Born to Rule is a fascinating book, with only a few small faults. It demonstrates using better data than others have yet amassed, how almost a third of one (good) definition of the British elite attended only one of two universities (Oxford and Cambridge) and how, of those, a third attended only one of only nine elite schools; but most importantly it demonstrates who everyone else who enters the elite is always in some way ‘connected’, and that British society does not appear to have become more meritocratic over time.

The book is written in three parts: Firstly, three chapters concerning who the British elite are and how we can know. Secondly, three chapters on how the elite reproduce and keep their privilege and how people in positions of power who appear not to be from elite backgrounds so rarely are what they initially seem. Thirdly, three chapters on why this matters. The book ends with a concise conclusion and call for action, and a thorough methodological appendix on the sources used –hitherto unavailable details on all members of Who’s Who born after 1830, 214 in-depth interviews or analysis of previous interviews carried out with surviving members, and a further 144 interviews of those who answered a survey. The appendix also details how the probate registry, established in 1858, was interrogated to ascertain the wealth of the elite and their relatives.

The key source for this book is Who’s Who. At any one time only 0.05% of the British public are in Who’s Who. The authors of this book have taken the database from 1890 to the present day and worked out what it takes to be somebody to get into the elite. Over sixty percent of people in Who’s Who are related to some on else who is included. The descendants of people in Who’s Who are 120 times more likely to be in than the general population. Much higher if they attended Oxbridge (350 times higher), and even the graduates of the lesser, but still elite, London Universities are 100 times more likely to enter the elite than the common ‘man’. Women who attended an elite girl’s school are some 20 times more likely than average to ‘become’ elite. Member of the British elite are hardly ever ‘self-made’.

One question is book poses: is how did these families keep their positions at the top of society? It reveals that within just five years of the end of World War Two, the richest 1% of people in Britain began to routinely hide at least 60% of their collective wealth from the government to shield it from inheritance tax; the money was hidden away, presumably illegally. A huge amount of that money had come from colonies, from plantations and from the labour of black and brown subjects of the British empire. Empire still matters greatly. Only 4% of new entrants to the elite are not white, whereas 25% are women and the remaining (almost three quarters of) newcomers remain white men. Some findings are stunning: Not a single person from a family with negligible wealth made it into the British elite, ever (see page 113).

Some of the elite appear to deliberately include lowbrow interests to appear less separated. Born to Rule gives the example of the sociologist (Baron) Anthony Giddens mentioning his support for the football team Tottenham Hotspur among his interests. Others replied to the interviewers’ questions on whether it is possible to distinguish between good and bad taste, in Latin: ‘De gustibus non est disputandum {translation: there is no accounting for taste}.’

I spotted only a single possible error in the book, on page 147. The Freedom of Information request answered by my university giving the income distribution of undergraduates almost certainly only relates to poorer undergraduates applying for means tested help. The authors did express surprise that the income of the 99th percentile of those Oxford university students’ parents was only £100,000 a year, with 1% having higher incomes than that. That was the figure for ones who thought they were poor.

This is an excellent book detailing a meticulous and careful study. Its authors have suggestions to address the problems of nepotism, corruption and lack-of-ability amongst those who still run Britain today. The target audience is sociologists and anyone interested in class, or the UK.

For where this review was originally published and a PDF of it click here.

The original cover of the book (first edition).

August 28, 2025

Asset managers work to increase wealth over time

On July 1st 2025, journalist Polly Toynbee wrote a story in The Guardian beneath the title: ‘To all who think capitalism can drive progressive change, it won’t – and here’s the shocking proof’ [1]. She was writing about the behaviour of one group of what are called asset managers.

I wanted to know what asset managers did, so I looked up an article on the web titled ‘What Is Asset Management, and What Do Asset Managers Do?’ written by Akhilesh Ganti in May 2025. I learned that “Asset management is the practice of investing money on behalf of clients. Asset managers work to increase wealth over time.” [2] This growth appears to be almost entirely in the wealth of the already very wealthy. Ganti’s article suggested that the take of the asset managers reduces to below 1% commission once they are dealing with many millions of a rich person’s assets, and that “There are many types of asset managers. Some work for family offices and wealthy individuals and others are employed by major banks and institutional investors.”

Ganti mentioned in particular the largest asset managers in the USA and how much money was under their control, suggesting that US law required them to put the profit requirements (or words to that effect) of their clients first, above their own personal desires, wants and feelings — and with no mention of any other important goals in a society when it came to asset management. The largest asset managers, and the amount of wealth they manage — wealth that they invest to turn into even more wealth, largely at the expense of the millions of little people who lose out — in descending order are: BlackRock ($9.46 trillion), Vanguard Group ($7.25 trillion), Fidelity Management and Research ($3.88 trillion), The Capital Group ($2.5 trillion), and Amundi ($2.1 trillion).

So, what has this to do with Toynbee’s story? Well, she was writing about a smaller asset management company, Aberdeen Group plc, which a quick web search (Wikipedia) suggests had £0.5 trillion of assets under management in 2024; small compared to the largest US firms, but no minnow.

In her story, Toynbee tells of asset manager Aberdeen’s surprise cut to funding research into inequality. This was done by altering who the trustees of a charity it had set up were, which has “…left those that used its grants for good works reeling.” For 16 years, the asset managers — which she describes as a wealth management and investment company — “sponsored some of the most influential research into inequality and its financial causes.” Toynbee puts the sudden change of heart down to events in the USA, saying that “Wildfires started by President Trump are engulfing global companies as his administration attempts to bar asset and retirement plan managers from considering environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions and targets private sector diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives with executive orders. Companies doing good are at risk. I ask Aberdeen if that’s why it has shut down the trust. It denies it strongly, saying it is just a ‘natural evolution’.”

Natural evolution is a strange argument to raise as a case for moving in a suddenly different direction. Evolution tends to take place slowly, gradually. More importantly, it is what occurs in nature, not something in the very unnatural and inorganic world of Scottish financiers — those not directly controllable by US law. Perhaps the person who coined that phrase “natural evolution” for why the decision was made to possibly cut all the funding into studying inequality and its ill-effects was thinking along more fictional Darwinian lines? The kind of lines illustrated in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, which was partly about how some people think of evolution. The questions raised concern who survives and who does not, what charitable bodies can and cannot do, and what is the fit and proper place for activities and people deemed to be of different kinds and different merits.

We now know that the charity funding so much of the now-threatened research could only operate at the largesse of the asset managers. The list of bodies the asset management firm’s generosity used to fund is long and included: the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), the Resolution Foundation, the Royal United Services Institute, Bright Blue, the New Economics Foundation, the Centre for the Analysis of Taxation (CenTax), the Child Poverty Action Group, the High Pay Centre, and Transport for All. It has also funded funeral poverty research by Quaker Social Action and consumer research by Which? At the time the decision was made to end its operations as normal, the trust reportedly had £3.6m promised to various bodies, including no doubt some of those listed above.

£3.6 million is a little less than 1% of 1% of the assets this globally small asset management outfit handles at any one time. Less than 1% of 1% of their monies. But none of the monies come from any of their clients — the charity was set up because of a mutual organisation, Standard Life, being incorporated into the asset managers when it demutualised. Established in 2009 as the Standard Life Foundation, it received a substantial donation from the unclaimed assets of Standard Life’s demutualisation. Most importantly, there is no equivalent funded through any other asset or wealth management firm, so the cut represents the elimination of 100% of this type of financier-funded research into inequality and its financial causes.

One of the organisations having some of its funding cut is the High Pay Centre. The Aberdeen group was titled Abrdn until a change to the more pronounceable version — with the vowels — in early 2025. Have a look at the front cover of the Annual Report of the High Pay Centre published in June 2025, and the logo at the very top. And then look at the slightly podgy man in the brown-green clothes sitting on the tallest pile of silver coins, or at the slightly more suave fellow with the blue suit and red tie striding beside the tallest pile of gold coins.

Figure 2: Front cove r of the 2025 High Pay Centre Research Report

Is it possible that having their logo at the top of reports titled ‘CEO to Worker Pay Gaps in the FTSE 350’ [3] might have annoyed someone whose day job involved overseeing deals that sometimes included people at the top of some of the 350 largest public companies in the UK — as well as myriads of smaller, entirely private companies?[3]

So, what were groups like the High Pay Centre publishing that might cause someone to think they should not be funded? In that latest report, it explained that after a brief initial fall in the greed of the greediest after 2018 (aided greatly by the arrival of the pandemic in China in late 2019), pay inequalities were increasing again in the years 2021, 2022, and 2023. However, the inequalities fell in 2024, as the first graph in that report shows. It is possible to reduce inequalities in pay, even in an era of Trump; but to do so requires reporting and observing — seeing what is happening and, in some cases, shaming.

Figure 2: Ratios of Top pay to lower and average pay, UK, 2019-2024

Perhaps someone does not want you to know that inequalities in extreme earnings can be reduced? Or perhaps there are other views they fear being aired?

Here are some words from within that High Pay Report, which was funded by asset managers who now no longer wish to fund such work:

‘Limitarianism’ and the re-distribution of earnings

Insights from the pay ratio disclosures are very relevant to an emerging debate about ‘limitarianism’ — the notion that in a world of finite resources, there should be an upper limit on individual wealth — and growing interest in the potential to raise living standards of those in the middle and at the bottom by redistributing the excess income and wealth of those at the top.

The premise of this argument is very simple. Those at the top hoard excessive income and wealth beyond that necessary to proportionately incentivise and reward innovation and productivity. If this income and wealth were shared more evenly throughout society, it would significantly raise living standards. The debate has mostly focused on taxation of the super-rich, in particular a wealth tax on multi-million pound fortunes. However, if we want to address the problem of extreme and inefficient concentrations of income and wealth, then it should be a priority to prevent them from emerging in the first place. This could mean regulating CEO to worker pay gaps.

There has been much speculation as to whether what occurred under the direction of people at Aberdeen was “in the best interests of the charity” [5] it had helped found. The Times questioned why “The chief executive and all ten independent trustees of Abrdn Financial Fairness Trust were removed in a shift away from funding research.” [6] As the old phrase goes, “damaged people damage people, hurt people hurt people.” There will come a time in the future when the decisions made to end the current work of the Financial Fairness Trust of the Aberdeen investment managers will be scrutinised and researched in great detail. I would not be surprised to find it linked through to more general histories of those at the top of British society with the power to harm others — perhaps doing it because they too were harmed, and hold inside themselves an anger? I have absolutely no idea, but I would be interested to know if there are links. [7]

Asset managers work to increase the wealth of the wealthy over time — how long should we tolerate them, and how they behave? When you hear people argue against “a wealth tax on multi-million pound fortunes” — think back to how the richest people in the world try to control the debate, what we know, and what we can know.

References

1 https://www.theguardian.com/commentis...

2 https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/...

3 https://highpaycentre.org/ceo-to-work...

4 https://highpaycentre.org/wp-content/...

5 https://www.dsc.org.uk/content/i-wish...

6 https://www.thetimes.com/business-mon...

7 https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/40676...

for where this article was originally published and a pdf of it click here.

July 16, 2025

How to Transform an Unequal Britain

When Keir Starmer became Prime Minister he promised ‘change’, and this promise was beefed up in his 2024 Christmas message with his six promises.

1. ‘More money in the pockets of working people’

Note This could be interpreted as more than the future rise for middle class, so lowering income inequalities. It could be interpreted as more than inflation, so increasing living standards. It was not clear.

2. ‘Building 1.5m homes and fast-tracking planning decisions on at least 150 major infrastructure projects’

Note No change from his previous promise of the ’40 new hospitals’ kind, but it might become an actual change. A promise to speed up decisions to make the decisions of whether something may be allowed.

3. ‘Treating 92 percent of NHS patients within 18 weeks’

Note It is worth comparing this to the ambition of the 1945 Labour government, creating an entire National Health Service from scratch, out of the then mess of charity and private healthcare existing provision.

4. ‘Recruiting 13,000 more police officers, special constables and PCSOs in neighbourhood roles’

Note A very technocratic solution to the breakdown of community cohesion and the disorder this can generate. More people walking around in a variety of uniforms, some of them on our streets.

5. ‘Making sure three-quarters of five-year-olds are school-ready’

Note Why not all of them? Or why not school at age 6 as elsewhere in Europe? And very little detail on how struggling families with children under age five will actually be helped, including helped to have hope.

6. ‘95% clean power by 2030’

Note This is the promise the far right attack the most. As Nigel Farage said at the time: “I think net zero is going to be an absolute catastrophe, electorally, for Labour.” Starmer could have said “affordable clean power”.

Contrast the above list to what Labour succeeded in enacting in 1945. The 1942 Beveridge report in which Beveridge was clear that the minimum benefits he proposed “should be given as of right and without means test, so that individuals may build freely upon it,” and that “no means test of any kind can be applied to the benefits of the scheme.” Or contrast it to the list that Gordon Brown produced in his Leader’s Speech to Labour Party Conference made in 2009:

“If anyone says that to fight doesn’t get you anywhere, that politics can’t make a difference, that all parties are the same, then look what we’ve achieved together since 1997: the winter fuel allowance, the shortest waiting times in history, crime down by a third, the creation of Surestart, the Cancer Guarantee, record results in schools, more students than ever, the Disability Discrimination Act, devolution, civil partnerships, peace in Northern Ireland, the social chapter, half a million children out of poverty, maternity pay, paternity leave, child benefit at record levels, the minimum wage, the ban on cluster bombs, the cancelling of debt, the trebling of aid, the first ever Climate Change Act; that’s the Britain we’ve been building together, that’s the change we choose.”

A cynic replies: A winter fuel allowance would not be required in a country with a decent social security system. We wait months, years even, for hospital appointments when our health service was once the best in the world. University student numbers increase. University management can profit by taking more and never mind the declining quality of education provided in return, or the mounting student debt. Half a million children can be taken out of poverty, but by such a small margin that neither they nor their families notice the difference.

Gordon Brown claimed, in much the same way that Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves now do, that almost all good only comes from economic growth:

“Growth is progress. Growth is what has given the world the tablet you’re reading this book on, the medicines by your bedside, the economic breakthroughs that have lifted billions out of poverty.”

That claim of Brown’s appeared in Permacrisis: “A Plan to Fix a Fractured World” a book he authored alongside Mohammad El-Erian (chief economic adviser at Allianz, the corporate parent of PIMCO) and Michael Spence (who in 1999 joined Oak Hill Capital Partners is a private equity firm headquartered in New York City, with more than $19 billion of committed capital). Brown and his co-authors, of course, were wilfully missing. A former Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer and prime minister whose politics were so often positioned as ‘Brownite’ rather than full on modernising ‘Blairite really shouldn’t need reminding by their book’s reviewer:

“They assume the development of a tablet computer is due to economics rather than developments in universities and other state-funded bodies which created the micro-components that that enable a computer to be transmuted into tablet form. Computers, and electricity before that, were not products of “the market” but technological inventions that have been marketised.”

If Keir Starmer wants to aim for a target that is far easier to achieve than he may realise, he should say he wants to reduce economic inequalities by a greater amount than either of his immediate forebears as Labour prime ministers managed, Blair and Callaghan (see Figure below). But to do so means breaking with their, and his, fixation on a model of economic growth that contributes next to nothing towards such a reduction. More often than not, it does the reverse.

… Chapter continues

For the full chapter and link to the original source click here.

Cover of the Starmer Symptom

July 8, 2025

Very Long-Term International Housing Price Trends

Against the backdrop of recent global house price inflation, this paper addresses the question commonly asked about asset price booms and crises: ‘Is this time different?’ To identify the distinctive characteristics of today’s house price booms, we examined the long-term history of housing prices in five capital cities: Amsterdam, London, Beijing, Seoul, and Tokyo. Specifically, we employed house price, annual income, and average expenditure data to estimate real house price indices from the 1620s to the 2020s. The findings indicate that recent house price inflation is distinct not in severity but in synchronicity. The amplitude of house price booms and busts has remained consistent. However, house price cycles that historically moved independently have in recent decades more often been showing similar variations both regionally and internationally in recent decades. Now, prices tend to rise and fall together, but do not rise above the historical peaks of the past.

1. Introduction

Although housing boom and bust cycles have repeated throughout history (Bordo and Landon-Lane 2014), the continuing global house price inflation of the last decade has raised concerns over housing affordability and widening wealth inequality (Piketty 2017). International organisations, including the UN, recently highlighted the severity of the crisis and urged re-thinking solutions (United Nations 2023). The bourgeoning discourse on the housing crisis recalls the typical question regarding all price booms and financial crises: ‘Is this time different?’

We try to answer the question of whether today is different by tracing the long-term history of house prices in five European and Asian cities: London, Amsterdam, Beijing, Seoul, and Tokyo. Specifically, we compare historical and modern real house price trends, calculated using house price and income data from different sources, to identify the distinct features of current house price booms.

2. Data and methodology

We collected historical and modern house price data for five cities from various sources and estimated real house price indices to compare them over time and between places. Here, the term ‘real’ means house prices compared to contemporary annual incomes or average expenditures. The minimum value of each data series was used as the base of the real house index and set as 100. The cities we selected were chosen because they have the most extensive and reliable time series data. Table 1 provides the details on data sources and estimation methodologies.

Table 1 Data sources and processing {see published paper – link at the bottom of this page}

3. Results

Figure 1 outlines the five cities’ historical and modern real house price indices. House price boom and bust cycles have repeated several times in the selected cities, while the peak of each cycle does not exceed 500 (five times the lowest ever recorded real prices), except in modern Beijing, where the inflation-adjusted index almost reaches 730. However, Beijing’s Price-to-Income Ratio (PIR) does not exceed 250, so its range is similar to other house price cycles. It is also worth noting that historical house price cycles have moved independently, whereas modern cycles have become much more synced with each other and indicate the boom phase that has recently caused consternation. Furthermore, house prices in Asian cities plunged in the late 20th century when the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) broke out and Japan’s bubble economy collapsed. Conversely, European cities experienced house price inflation during the same period. Thus, the current global synchronisation is unusual. Given this coincidence, this time might be different.

… paper continues….

For A PDF of the full paper and place of original publication, click here.

Figure 1:

June 27, 2025

The Real ‘Strangers’ Among Us

Those who declare the UK to be an island of estranged individuals are the ones who should be looking closer to home, writes Danny Dorling

Imagine our communities in years to come. The elderly, smiling on park benches as parades of perambulators pass by. The young, pushing grandchildren – Britain’s next generation – and everyone with happiness in their hearts.

Imagine a future of harmony, a sense of community, a feeling of quiet progress. Children doing well and mixing happily with others. Cities rebuilt, renewed; all neighbourhoods safe and clean. Britain a pleasant land of friends and acquaintances, of nods and smiles, of familiarity and comfort. Social hierarchies smoothed down to gently rolling hills of mild privilege above wide meadows of decentness.

During the 1950s, more so in the 1960s, and especially in the 1970s, this future mostly came to pass. Children’s families had security of tenure. They lived in homes from which they could not be evicted if the rent or mortgage were paid – and it almost always was paid. There was full employment (for men). Cheap new housing (for most). New schools and hospitals (for all). A green and pleasant land, if a little rose-tinted around the edges of our memories.

For a time, the most strangest and unusual of all people, the aristocracy, and the somewhat weird servant-keeping classes had largely disappeared – because they had assimilated.

But then new strangers began to appear among us. People whose lives resembled ours less and less. Increasingly speaking differently, living in enclaves, taking much more than their fair share. We did not see their children in the parades of perambulators. They began to bring up their children separately from ours. They hoarded money, looked after their own, and were increasingly remote from the rest of society – while telling us how essential their presence, and contribution, was.

Occasionally these incomers took over whole neighbourhoods, although more often they just built higher walls and clustered together in streets where they felt safer –away from us. As social interactions diminished, they succeeded more and more in avoiding our eyes, and then our spaces. We began to notice that they dressed differently, behaved differently. In their minds the worst thing that could happen would be if one of their children fell in love with one of ours.

The new strangers hid their real religion and beliefs; their laws about what was right and wrong, acceptable and forbidden. They had their own customs and traditions, rituals, holidays, words and manners. They talked of how today is not a progressive era, but a tragic one. They pretended to feel our pain, saying that ‘things don’t always get better’ and implying they had the solution – which was to accept having them in charge. They claimed to be traditionalists – but they were immigrants; the real strangers in this land.

These strangers were once a part of us. They never quite belonged, but in the past they could mostly pass as normal, despite, as children, usually looking and sounding a little different. They might have been brought up separately, in minor private schools, or schools that had been grammars; but back then their parents were not paid that much more than everyone else. They might have had a little property, or been highly successful professionals. A stockbroker in the 1960s was usually not rich, just well-off. Work in the City was once a relatively normal job, unlike today when being successful in finance sets you so utterly apart.

But despite always having had some advantage, in those days they could pass for one of us. In their youth they listened to the same music, and tried to dress and speak the same as us. Today, their children are far easier to identify just from a single spoken sentence, or a haircut, or how they walk tall.

Strangers in the city

Today, fees for private schools are very much higher. To separate yourself, you have to be able to take a much greater share of other people’s money. House prices around favoured state schools mean you cannot live there unless you, or a close relative, have somehow expropriated greatly. Today, no one makes their way into these areas by their own sweat and toil. Inheritance matters once again. This is why they don’t want their children mixing with yours.

These strangers are fixated on you and what you think and feel because they fear you. They need to tell you what is good for you because they have financial interests to protect, and greatly unequal wealth distribution to maintain. They tell you that growth, not redistribution, is the answer. They push a politics of what ‘most people in this country would agree with’. They talk about Muslims and anti-racism ‘wokeness’, to show how connected they are to the masses.

These strangers peddle stories of the dangers of immigrants and ‘grooming gangs’, and how young men need to have strong, macho role models, and of what they call common sense.

To protect what they and their families have stolen – or, in softer language, amassed – they need you to be afraid. Not of them, of course, because they do not want you to see them as strangers – they are your clever friend, they roll up their shirt sleeves and occasionally wear hard hats. Instead, they want you to be afraid of imaginary monsters in the dark.

These strangers inhabit think tanks and policy units. They attend dinner parties and rub shoulders with the great and good of the media, universities and business. We used to call it gentrification when they took over whole neighbourhoods. What an old fashioned class-war concept, they reply. The strangers are pleased if you know that they once attended a state school – their badge of having once mixed. But school choice for their children is a private matter, not open for discussion.

The strangers malign the past, discrediting the old politics of achieving a good home and life for everyone. Instead they promote private house-building wherever there is ‘demand’, rather than better using the stock and space we have.

They are patronizing. They tell you not to worry your little heads over economics. It is complex, they say; and what they are offering is the only way possible. Work very hard, and perhaps you can join the adults in the room who look after the little people. They do, however, have to discipline the poor: those who have too many children, the disabled who do not try hard enough to work, and the old who have not saved enough money to avoid going cold in winter.

In their youth, these strangers had more leisure than most. Looked after financially by their parents, they could travel, and dabble in whatever was fashionable in political fringes. Many have a story of their exciting activist past. They have always lived elite and economically secure lives, but thought they were normal.

They are strangers today because they are as distant from the rest of us as the old-fashioned one-nation Conservatives once were. Some may have a sense of why people in the UK really are estranged. But they will not fit in with their peers if they mention it is really about money; not skin colour, not immigration, not tradition. Very often they cut their political teeth in gentrifying London boroughs around the turn of the millennium. They are almost always white, mostly men, mostly in their 50s and 60s. Often they turn their jeans up to try to mimic the cool of their youth, sometimes to help highlight their statement trainers, or exciting socks.

They are the beneficiaries of social atomisation. The ones whose parents grabbed more and more when the old solidarity was dismantled in the 1980s. They are the products of people who ‘bought well’. Under their rule the price of beer rose in pubs so that only they can drink in them. A third of children in England now grow up in a home owned by a private landlord. Even more children now have no summer holiday. Under the strangers’ rule, schools have been academised, hospitals split into competing trusts, and doctor and dentist become distant.

As they carefully curate their own children’s futures, they peddle myths: that darker-skinned people are the strangers; that racism is understandable and acceptable; that we have to tighten our borders, celebrate the best of our history, grow our military, double down.

They tell us that there is no alternative – other than the fascists who will come if we don’t accept their slightly more mild-mannered, but still racist, future. Under their rule they will deport more people on planes than the last lot. They will appear on our screens with more and more Union flags behind them. And they will warn you of the threat of strangers. In reality, however, it is their kind you will never actually meet.

They don’t live near you or mix with you, and they want far better things for their children than yours: houses, education, private health care, villas abroad. Your children will, at best, work to keep their offspring in the manner to which they have become accustomed. They have no wish to sit on a park bench in their old age, looking out at a mixed society as perambulators pass by. They only imagine themselves as safe if Britain can be an island of strangers. And they want you to fear – or better still hate – your neighbour.

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here.

June 26, 2025

Calling Out Racist and Jingoistic Rhetoric

“…examines the rise of nationalist and exclusionary rhetoric in British political discourse, calling out the quiet normalisation of racism and jingoism at the highest levels of government. Drawing on recent political statements, Dorling argues for the urgent need to challenge these narratives and defend a more inclusive, honest understanding of national identity.”

On May 21st, 2025, former Prime Minister Gordon Brown was questioned about the Labour Government’s possible winter fuel allowance U-turn by the Sky News journalist Sophy Ridge. That day, the current Prime Minister had indicated that he was minded to re-look at the decision to scrap the payments for pensioners who were not the poorest of all pensioners. [1]

Brown appeared to choose his words carefully. By omission, they could be interpreted as implying that he believed that people should be allowed to fall into poverty if they had not “served the country well.” But why promote a policy that appeared to differentiate between an undeserving-poor and the apparently deserving-poor? And why make some kind of measure of national service or patriotism the loadstone of determination? Here is what he said exactly: “To me the issue is, nobody should be pushed into poverty if they’re doing the right thing. Nobody who’s working hard, or nobody who’s served their country well over their lifetime, should be pushed into poverty, if we can avoid it.”

You might read those words another way. You might not worry about the phrase ‘the right thing’ or ‘their country’. You might not note, perhaps with surprise, the emphasis on hard work as what is required not to be pushed into poverty (‘working hard’). You might, or might not, be concerned that ‘served their country’ is mentioned with all its military overtones. You might not have noticed the caveat at the end about this all only being conditional: ‘if we can avoid it’.

You might think I am being pedantic, splitting hairs, pointing out small issues and giving them undue importance. That might be the case, if it were only one aged former Prime Minister saying such things. But Brown’s comments appeared as part of a pattern of talking up the rights of some people of this country, especially those who had ‘served well’, and by omission talking down others not mentioned. Note also that this older population mentioned here are largely white. However, it was not just older people who had served that were being highlighted by former and current government ministers and Prime Ministers in the springtime. White children were also being singled out.

Just over a week after Brown spoke, the Labour Government’s Education Secretary, Bridget Phillipson, launched what was termed: ‘an independent inquiry into white working-class children’s progress at school’. The Times newspaper reported this announcement under the headline ‘White working-class children “betrayed by politicians”’, and quoted Phillipson as saying: “The data shows a clear picture. Across attendance, attainment and life chances, white working-class children and those with special educational needs and disabilities do exceptionally poorly. Put simply, these children have been betrayed — left behind in society’s rear-view mirror. They are children whose interests too many politicians have simply discarded.” [2]

Anyone who speaks in public chooses which statistics to highlight and how to interpret them, what to put emphasis on, and what to ignore. Data never shows a clear picture. It is just numbers. The description of data reveals the picture that the person interpreting it chooses to paint, and how they choose to present it. This does not mean that anything goes. A lie is clearly a lie, a fact is clearly a fact, but data doesn’t contain words like ‘betrayal’, or show that it is because some children are both white and working class that they do badly. What it does show is that children in London do especially well, and that is not, of course, because of the often-darker colour of their skin. It is because they live in London; it is their geography, not their class or ethnicity, that matters most here.

The advisers to ministers will know this. Over four years ago they will have read newspaper stories of academic reports, and studies from the Office for Students with titles such as: ‘Geography, not race, explains the disparity in England’s educational outcomes’. These studies explained that “white students who receive free school meals in London have pulled away from those in other parts of the country with their rate of HE participation 8% higher than any other region, at 44.7%.”[3] – in other words, being white and probably working class, and definitely poor, was far less of a problem if you had many potential black and brown school friends living in your neighbourhoods.

So why do Labour Ministers and Prime Ministers say such unhelpful things about some groups explicitly being more apparently deserving, or losing out, than others? Why pontificate over who has served the ‘country’ of the UK well? Why concentrate on this apparent white working-class construct both existing (as a useful thing to talk about) and having been apparently neglected?

One reason why is who advises the government now. What happens in the public sector, and why you are reading the magazine this article appears in, is due to the beliefs of government advisers as well as politicians. They determine policy. The coterie of current influential government advisers includes people who say of the Labour party: “It doesn’t know how to deal with race, except to be anti-racist or to go along with DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion]…” [4] — which reads like a complaint about being anti-racist. The same key government adviser goes on to claim: “The problem is that the left has convinced itself that we’re an immigrant nation, and we’re not. We’re just not…”

This should raise more questions. Why do some of those who currently have the ear of power think that the UK is a single nation? We have not referred to Scotland as Northern Britain since Victorian times. Where on earth do they think most of these islands’ inhabitants or their recent ancestors came from? Most people living in Britain at some point in their personal family history, if they go back far enough, have at least some relatives that were from abroad. So many of us even have surnames that mean our father’s father’s fathers were living abroad, not too many generations ago. [5]

If you do not believe me, try to imagine what the decennial British censuses have revealed ever since country of birth was first asked, in 1841. Censuses can be used to see what the origins of us were, back to our parents, through to our great-great-great-great-grandparents. Almost unique among states, the British state has one of the longest records of ‘who do you think you are’, and that is before you even consider that almost all the subjects of the empire were at one point or another legally British. It was the ‘British empire’.