The BBC, inequality, and the Multi-Coloured Swap Shop

The BBC was once an engine of progressive change driving British society to greater equality – Danny Dorling asks what changed, and why?

This article makes an unconventional argument, that the BBC was pro-egalitarian until the late 1970s and then a less benign dominance took hold. Slowly at first, but later that new dominance grew to have a negative influence over British culture, politics, and economics.

Using the BBC’s commissioned children’s television shows by way of playful example – which might mean more to the older reader – I argue that in the 1930s, the last time the UK was as economically unequal as it is today, many social engines were pushing British society towards greater equality.

From 1922, and for at least half a century, inequality in income fell every year, until around the advent of the Multi-Coloured Swap Shop in 1976 – coincidence, not cause. Class divides tumbled and we began to better understand each other.

However, in more recent decades, our increasingly London-centric media has more often provided excuses for trying to explain away huge inequalities as if they were inevitable. This has led to the current impasse whereby, as Adam Bienkov wrote in Byline Times: “…the BBC continues down its recent path of seeking to appease and co-opt the very forces whose political and commercial interests demand its destruction.”

Engines of Equality

The BBC has always been a London institution. London was home to 7.5 million people in 1921, roughly a fifth of the then population of England and Wales. A million fewer lived there by 1981, and nearer to just one in eight as a proportion. The national populations were rising, London was shrinking. However, by 2021, the census recorded the capital’s population at nearly 8.9 million; a proportional rise as well as an absolute one, to one in six people in England and Wales.

This demographic trend reflected many other changes; not least the fall and rise in national economic inequality – which today is again at a high peak. When inequality fell nationally, that was not because London depopulated, but because arguments for greater social justice were often made effectively, if not always overtly, by people and institutions in London.

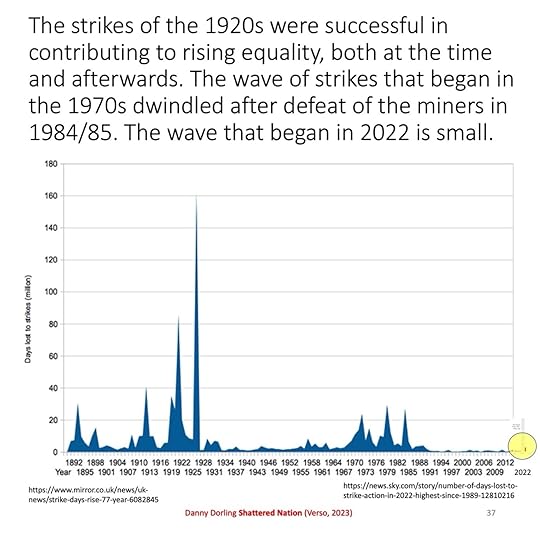

Figure 1: Days lost to strikes in Britain 1880s to 2020s

Many separate but connected engines of equality fired up in 1922. Northern Ireland was less than a year old, having been created by the British Government when it partitioned the island of Ireland. A revolution in Russia had concentrated the minds of the British upper classes. The recently-founded Labour Party was in disarray (not unlike today). New higher levels of taxation had been required to pay for war, and those new taxes had begun to eat away at the wealth of aristocracy. Strikes abounded, far more than at any other time in British history, (see Figure 1). The world, and especially Britain, was changing rapidly – turning towards great equality. The huge drop in strikes after the 1920s and 30s is partly testament to changes in national sentiment, often led by people in or near London – John Maynard Keynes in the 30s and William Beveridge in the 40s come to mind.

Culture and media in Britain were moving from theatre and newspaper to broadcasting and radio. London was the centre and at the centre of London was the BBC.

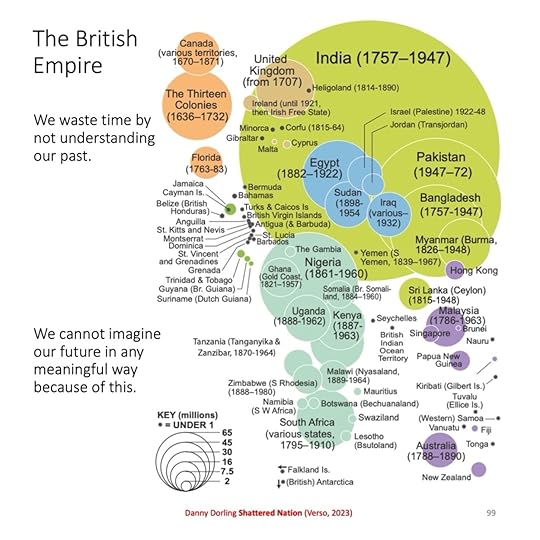

The young men and women that the BBC relied upon back then are often portrayed as ‘stuffy’ today – but they were a part of the generation that had seen their parents and grandparents take Britain into two World Wars, and lament the loss of a London-centred empire; an empire that more and more progressive young people would realise was coming to an end (Figure 2). The most progressive realised it could not be justified.

When the British Broadcasting Corporation was born, it was the mouthpiece of an empire which still looked like Figure 2, bar the thirteen colonies (which had become the USA) and a few other mostly white places. The BBC staff were often technically able and often very young. They also included many at the forefront of much of the new thinking that was emerging out of the 1914-1918 ‘war to end all wars’. However, they were also regularly vetted to ensure their political views were ‘sound’.

Figure 2: The maximum extent of the British empire

Many of the men who first worked at the BBC had fought alongside others who they would not normally have seen as equals. They were influenced by new thinking. Two young men, both born in Calcutta and Exeter respectively, met as boys at Rugby school just before the century turned: R. H. Tawney and William Temple. Tawney would go on to have great influence at this time on our understanding of political and economic history, and William became chair of the General Advisory Council of the BBC in the 1930s. When economic and social inequalities last fell in the UK, a part of what made that happen were the changing views of the younger members of the British upper classes.

A third young man Tawney and Temple met at Balliol College, Oxford, was William Beveridge. A product of empire, born in Rangpur (in what is now Bangladesh), he famously helped usher in the welfare state. One of Beveridge’s key advisors was the son of Joseph Rowntree; Beveridge’s assistant was Harold Wilson. These were the generation that most influenced the thoughts of those who first worked in the BBC, alongside a grudging but growing understanding that, in future, far fewer posts of influence would be held entirely exclusively by men.

Behind the scenes, more women were employed. In contrast, it was the print media that most remained the bastion of men. With hindsight, it was unsurprising that the London-based BBC became one of the more positive parts of the engine for increasing equality.

When you broadcast, your message cannot be separated so that only a few can hear it. You cannot overtly tell your listeners that most of them are beneath you. Broadcasting was, by definition, broad. A universal service was created; the same information being made available to all – although it came from London.

It was in promoting universality that the London-centred BBC was most obviously an engine for increasing equality. The printed press produced papers aimed at different social classes and nothing for the large numbers of adults that were still illiterate. But the voices emanating from the wireless could be understood by all. Although initially only a few could afford a wireless.

The BBC had to talk on everyone’s level, it also began to develop a Reithian creed to disseminate “All that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement. [where] The preservation of a high moral tone is obviously of paramount importance”. Of course, one man’s idea of what is best differs from another, as do views of which morals are high. But it is worth remembering London’s past contributions to progress and not seeing the capital as trying to hold change back.

It may seem odd to refer to the early work within London of the BBC as progressive but, for its times, it was. On 2 November 1936 the first BBC television broadcast was made. Those stilted announcements in Received Pronunciation English, read by a man in a dinner jacket, were talking to people while looking them in the eye and knowing that they too were looking back at him, albeit through the screen. At first, the announcers knew that it was only the most affluent who could purchase a television set and live within range of Alexandra Palace, to view those first flickering images. Nevertheless, the founding principal of the BBC was a dedication to giving everyone the same high-quality information and entertainment.

There was propaganda too of course. Television came to Britain on 22 March 1935, after having arrived in Germany a year earlier (via the USA, where broadcasting had begun in 1928). A television service was seen as vital so that the home population could be spoken to directly.

Those in the know knew that war was coming again. It had already begun in Spain. In 1936 in Catalonia, George Orwell wrote that: “Waiters and shop-workers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared.” In 1938, when Homage to Catalonia was published, the young men and women at the BBC would read Orwell’s words. And then they too would go to war. His words and thoughts also reflected and helped form the new thinking in London in the 1930s and 40s.

The wireless programs and television broadcasts from London were innovative. Woman’s Hour was first broadcast in 1923. Listen With Mother was introduced in 1950. This was a shift away from talking to largely upper class women, the first female listeners who could afford a wireless. This shift was towards instead conversing with many more mothers and children. The Second World War accelerated many other cultural trends, and again this acceleration was often from London and its satellite cities.

Adult comedy arrived and was almost instantly subversive. Beyond Our Ken aired on radio from 1958-1964. It parodied the politicians, politics, and the stuffy culture of the day. Round The Horn was satire broadcast on BBC radio between 1965 and 1968. Monty Python’s Flying Circus was aired from 1969 onwards.

All this was unimaginable when the BBC began in 1922. But this was 1960s London.

The most subversive of all, the greatest engine of equality, was children’s television. Imports of 1930s Micky Mouse cartoons began to be replaced by home grown creations during the corporation’s second quarter century. Muffin the Mule in 1946. But there was quickly more, much more. What began as the Railway Series, in 1953, become Thomas and Friends. Again, some of the nastier elements of the children’s books the series was based on were tempered. The Referend Awdry, who had created Thomas the Tank Engine, although a pacifist, had some issues which the early BBC smoothed over.

Blue Peter began in 1958. Named after the signal flag for the letter P that in Britain had been hoisted, ever since 1802, once a merchant vessel is ready to sail (from London docks mostly in those early years of the nineteenth century). Thus, the new flagship children’s programme began with an image of Britain’s great nautical past – two years after the Suez Crisis, and the loss of all British naval control East of Eden. Within a decade, the London docks were closed, and we children who grew up ready to sail into the world were making do with toilet rolls and sticky-backed-plastic – imported through other means.

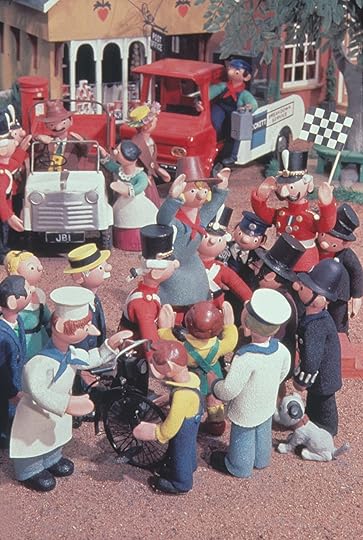

The 1960s were the BBC’s and London’s most innovative decade. Planes, trains, ships and automobiles – all symbols of industrial prowess – featured often in the early children’s programming of the BBC. But less so in Play School (1964), The Magic Roundabout (1965-1977), Jackanory (1965), or Camberwick Green (in colour in 1966) which starred a fire engine and a set of workers from that most working class of all the public services – the fire service. Most importantly, in terms of discussing inequality, opportunity and the future of the British capital, all the key cultural and political decisions to put out this socially more equalizing propaganda were being made in London.

Camberwick Green

Pugh, Pugh, Barney McGrew, Cuthbert, Dibble and Grub might have loyally rescued cats stuck up trees in a fictional middle England village, but they did so through to the advent of the first national pay strike by fire workers in November 1977. Although the children’s show never featured a strike.

Nevertheless, it was subversive because it presented all the people of the village as being of equal worth. They might have known their function, and almost all of them were men, but there was no squire in the village, no boss, no big house on the hill, just a windmill that was useful for grinding flour.

Dr Mopp was no more important than Peter the Postman; Windy Miller was on the same level as Mr Crockett the Garage Man. Roger Varley the Sweep did not have to look up to PC McGarry (or down on him); Mr Dagenham the Salesman, Mr Carraway the Fishmonger, and Mickey Murphy the Baker were friends. Mrs Honeyman and her baby (introduced on 28 March 1966) were concerned about the inequitable distribution of childcare.

It was from London that this story was piped out to the airwaves; 1960s London. The times, they were a-changing, and the BBC was helping to change them, reflecting London upper-middle-class thinking of the day.

This was my BBC, the programmes I saw as a child. The BBC had softened the Tank Engine tales to be suitable for the new times. Bolshie the Bus was still named after the Bolsheviks (the bus approved of strikes). However, the Fat Controller was no longer presented as someone to aspire to be. Far better, a working-class workaday hero, like Thomas.

It was not just ‘loony-left’ councils and the Inner London Educational Authority that were decades ahead of their time – the London mainstream was, including the BBC.

We each have our own favourites, and they very much depend on our age. From 1969 to 1973 I avidly followed the Clangers on BBC1. I had seen the moon landing live. I understood every word that the soup dragon said, although I didn’t know that the Clangers, when whistling, were actually ‘swearing their little heads off’. Nevertheless, I got the gist. The joy, and the sentiment.

But what did John Reith and his now old generation make of all this? Reith died in 1971. In 1975 a series of excerpts were published from his diaries which suggested he would not have approved.

The BBC content was becoming ever more progressive despite the frowns of a few – Britain had also become the most equitable it had ever been in terms of income inequality and the speed of the breaking down of class and gender barriers. In the 1970s of all the larger European countries, only Sweden matched the UK. The BBC with its London thinking had helped drive that growth in equality.

For my parents’ generation, after Reverend Wilbert Awdry (1911-1997), the second of St Peter’s College Oxford’s most famous alumni, Ken Loach (1936-) also became a BBC star content creator. Early on much of what he created was first broadcast by the BBC. From episodes of Z-Cars (1964), and seminal films like Up the Junction (1965), Cathy Come Home (1966), Poor Cow (1967), Kes (1969), and The Price of Coal (1977), to later works such as The Wind that Shakes the Barley (2006), The Angels’ Share (2012), The Spirit of ’45 (2013), I, Daniel Blake (2016), and Sorry We Missed You (2019).

There was much more than that from Loach, and a deluge of radical television films from others. The list above is just a summary of some of his best-known material, but you won’t see these later tales told on the BBC.

It was not Loach who had changed though. It was the Beeb and sentiment in parts of London.

Loach was painted as a pariah when he explained that in his view the BBC had played an “absolutely shameless role [in] the destruction of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership” of the Labour Party. In 2023, the BBC reported how parts of the Labour party, including its leadership, now viewed appearing with Loach on stage as a reason for not allowing Jamie Driscoll to stand for political office in North East England.

What can explain this transformation of London mainstream upper-middle-class thinking, as exemplified by the BBC from progressive to regressive – at least in how Ken Loach recently describes it? Why did London start to kick down on the regions?

London changed. It gentrified. Who worked in the BBC changed. The whole of the UK became more economically inequal, so the top tenth of people, the graduates among them who had the best-chances of working at the BBC and living in central London, were now coming with the experience of being more separated from the rest of society.

Don’t be fooled by the occasional additional ‘regional accent’ or more ‘older female faces’, or a greater ethnic diversity in front of the camera (if not behind it) – to be able to be a part of the engine of culture in the country that polarized the most in all of Europe increasingly meant to have been born to life’s winners.

The views of politicians, of Secretaries of State for culture, media and sport, also weigh heavy: As Tom Mills states in his 2020 book The BBC: Myth of a Public Service “…the contemporary BBC is no more free from the influence of powerful interests than it was in the 1930s.”

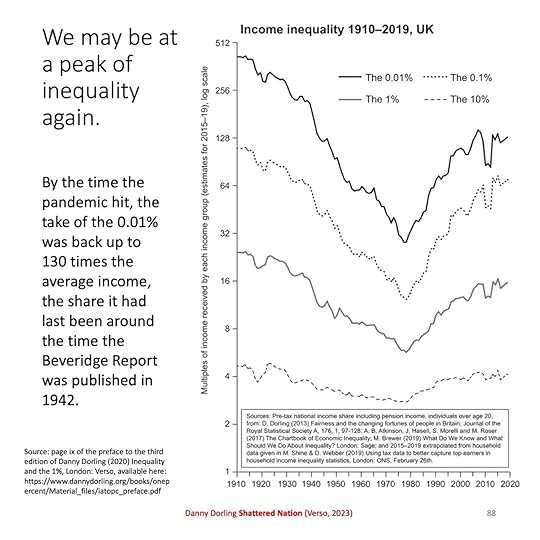

Figure 3: The long-term trend in inequality, UK 1910-2019

The graph above (Figure 3) may be helpful here. The BBC had to stay neutral and did stay neutral. It had to be impartial and remained impartial. It is just that what it meant to be neutral, to be impartial, in Britain had changed, and at its heart by income we have become ever more unequal each year after the late 1970s. So, to be neutral, if upper-middle-class London based, is to be with the folk who have more. A million-pound house became normal, for those who can influence culture the most.

The Turn towards Inequality

I did not grow up in London, but I imbibed London culture as a child through the BBC. My 1970s watching of children’s television did not include Ken Loach’s films. Instead, in 1972 I first saw Newsround. I watched Noel Edmunds and his Multi-coloured Swap Shop in 1976, but knew that Tiswas on ITV, and Sally James, was better (1974-1982). I was aged 14 in 1982. All but the most sheltered of boys knew that Sally was better than Noel. Tiswas was filmed in Birmingham, Swap Shop in London.

Grange Hill (1978-2008), filmed in London, was a valiant attempt by the BBC to try to regain ground it had begun to lose to ITV. Unfortunately, it was the only comprehensive school in Britain where no child ever said “fuck” (as some 1980s alternative comics once explained on BBC TV). I later learnt that it was required voyeurism among a great many of those who I met at university; those whose parents and been able and were willing to ‘send them private’.

For most children, Grange Hill slowly moved away from being reality television, away from being subversive and progressive, and became a series of public health announcements, strung together for the lower orders with the off-putting message: ‘just say no’ (to drugs).

London was becoming more different. The 1991 census revealed it as being the only place in the UK where a majority of adults aged 16-65 were not married. That was a part of the reason it was so progressive. But increasingly, our TV and radio was not being produced by young men and women who had a sense that much of the generation above them had got it wrong, had failed to prevent two world wars and had subjected entire continents to their racist beliefs. Programmes were no longer being scheduled by those who had a sense of urgency about the need for a more equitable future.

The various new manifestations of the General Advisory Council of the BBC were no longer chaired by people like Bishop Temple who had lived through the great social transformation. Yes, the BBC had regional outposts, wildlife filming was based in Bristol, but these were always outposts. The move to Salford was cosmetic. It implied devolution; but power, people and money were again being concentrated in London as most regional BBC offices faced cutbacks.

By 2015, the 1% in Britain were again taking a huge share of everything – more than their equivalents in any of European country. In London the 1% is nearer 10% of the population, is nearer to ‘normal’ for the creators of culture.

The British might have always been a little stuffy, but there was a time when London was breaking that tradition – long before ‘cool Britannia’.

In its early days, BBC technical ability and flair mattered as much as the old school tie. Always, as Ken (Loach) and Wilbert (Awdry) illustrated, an Oxford University background remained an advantage, and Cambridge too, especially as regards presenting the Today Programme. However, what was seen as talented, began to change. Spitting Image (1984–1996) was no match for That Was the Week That Was (1962-63), but better than what little satire came after 1996. New Labour and Cool Britannia came with less fun.

The rapid increase in income polarisation that occurred across the UK from the 1970s onwards meant that a job in the BBC became an ever more coveted aspiration for those families increasingly desperate that their offspring should stay in the top 10%. Joan Bakewell could appear on Late Night Line-up in the 1960s despite being the granddaughter of factory workers. In contrast, most of the intellectuals on screen today grew up in ‘the 10%’. This was a group that by the end of the 1980s came to take and spend 40% of all income each year in the UK. To move to London and live in London today, to work at the BBC now, usually requires a little ‘family money’.

It is well known that our actors, sports folk, and media stars are now from less economically diverse backgrounds than in our more equal past. The expense of London is one reason.

More of those on screen were women, or black, or brown, or mixed, or talked in non-received English, but that window dressing could not disguise the growing exclusivity of who now got to the top. Social mobility was now falling. The British state was moving rightwards, having only very recently seen its two main political parties swing so far to the left, competing to see which could build the most council houses each year in the 1950s and 1960s. Very few council houses were built after 1979. The state began to wither, and a part of that withering concerned the budget of the corporation.

Crackerjack, filmed initially in west and then central London, ended in December 1984, as the children of the miners looked forward to their first Christmas without enough food. Roland Rat (filmed in Camden) appeared on the BBC in 1986, just as the Conservatives enacted the Big Bang in the City of London and financiers cheered from their open windows on hearing of the top rate of tax falling to 40%. Appropriately Roland had been poached from ITV in 1985. The BBC became more commercial and less cerebral. On arriving Roland (Rat) announced ‘I saved TV-am and now I’m here to save the BBC’.

Newsround joined Grange Hill in 1986 in drawing its youngest viewers into the war against drugs. London could diversify and kept much light industry. Far away from London, when shipbuilding went, and there was little chance of a new winter coat, shoes for the wife, or a bicycle on the boy’s birthday, that heroin became so very attractive. Personal responsibility became the new order of the day.

The Radio One roadshow began in the summer of 1986, shortly after the miners had been comprehensively defeated – free entertainment for those without loads of money – coming to a beach or park somewhere you; but just for one day – and just once in your life (if you were lucky).

Playschool ended in 1988, appropriately alongside most voluntary playgroups in Britain which folded as private for-profit nurseries took over the childcare industry. It was replaced by Playbus, later Playdays, from 1988-1997. Sadly, play was going out of vogue in those dark years of high but still rising economic inequality and mass youth unemployment. But at least there were still no foodbanks. Years later the BBC, very solidly still from London, was reporting the provision of foodbanks as being positive aspects of life in northern towns.

John Craven stepped down from Newsround in 1989 to host Countryfile – rural idyll escapism with an occasional nod to struggling hill farmers.

My view of London as so dominant was formed when I moved to Newcastle upon Tyne in 1986 and stayed there for a decade. I had gone to Newcastle to study. Why Newcastle? Because of Jools and Paula. It was from the banks of the Tyne that Jools Holland and Paul Yates broadcast The Tube between 1982 and 1987. That it was broadcast on Channel 4 showed that the BBC was facing public sector competition. That Channel 4 was publicly owned showed that competition was possible without profit.

Who knew then, that in just three decades time (in 2023), the BBC would be tasked with creating an annual quota of stories from the extremities of Britain telling tales of how life on the edge was not so bad after all? Among my generation, political views today often reflect where people spent their 20s (in the 1980s and 1990s) – in bustling London and the South-East, or in the periphery where the majority of more than three million unemployed lived.

There was a sense when I was young that the turn to inequality and wealth (and poverty) concentration in London was not inevitable. The BBC, by broadcasting The Young Ones in the early to mid 1980s, demonstrated that you no longer needed to attend Oxford of Cambridge to be a success. One possible hidden message between the lines of the first appearance on screen of Rik Mayall (Manchester), Adrian Edmondson (Manchester) and Nigel Planner (Sussex and the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art) was that the cultural dominance of London was ending.

Prior to the 1980s, almost all subversive comedy on the BBC had been created by those who had first been students in the Cambridge Footlights or the Oxford Revue and lived in London. Perhaps due to the early influence of The Clangers and Camberwick Green, I believed that the world was changing and becoming more equal. As a teenager I thought that the 1980s and Mrs Thatcher (a London MP) would be only a brief aberration – I was very mistaken.

One of the writers of The Young Ones, Alexei Sayle (Garnett College, Roehampton), was even allowed to have his own series on BBC2 in the late 1980s and mid 1990s; but the UK was shifting rapidly politically rightwards in those years, and London again increased its cultural dominance.

So dominant it could move a chunk of the BBC to Salford, Greater Manchester, and produce programmes from there, as if they were made in London – can you tell the difference?

The BBC and its London message are the family you have always grown up with. You know them. They are in your living room. If you are an avid listener their words are in your ears, from the very moment when you wake in the morning to just before you go to sleep. Their stories are your stories. If you meet a BBC presenter it is difficult not to say hello, as if you have always known them. But they long ago stopped being the working parts of an engine of equality and became slowly, but certainly by today, chief apologists for and advocates of an economic logic of rising inequality.

There was nothing deliberate in this. Nothing was planned. It was not a conspiracy. All that happened is that they – the presenters, producers, writers, editors, advisors, heads of programming, trustees, board members, the entire machinery – tried to stay in the middle. And the middle moved.

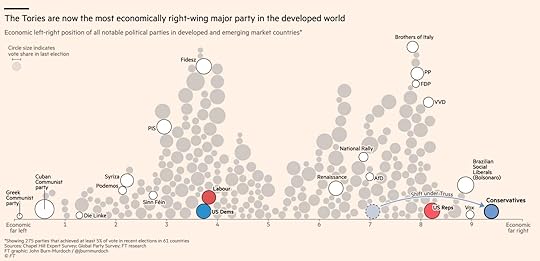

The middle in the UK moved far further to the political right in the last four decades than it has done in any other state in the world (according to analysis published in the FT) [see directly below]. At the very heart of this shift were changes that look place within London. They are most obvious in terms of the cultural changes and have been illustrated here using the BBC as an example.

It is possible that today we are beginning to see a change around again. But if it happens it will be evident in what an institution such as the BBC in London does and says. As I write, in November 2025, the key issues is how will the BBC, and the UK as a whole, stand up to Donald Trump? Or will it decide that it should be impartial, and to be impartial means to grovel?

Biographical note: Danny Dorling is a professor in the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford, and a Fellow of St Peter’s College. He is a patron of RoadPeace. Comprehensive Future, and Heeley City Farm. In his spare time, he makes sandcastles.

For where this article was originally published and a PDF copy, click here.

John Burn-Murdoch (2022) The Tories have become unmoored from the British people, The Financial Times, September 30th 2022:

Which parties are most left and right wing economically worldwide

Camberwick Green, a haven of social equality. Photo: Moviestore Collection/Alamy

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers