Danny Dorling's Blog, page 3

November 18, 2024

Review of The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World by David Graeber and published by Allen Lane

The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World brings together a selection of writings spanning two decades by the renowned anthropologist and anarchist David Graeber. The book reveals both Graeber’s original, profound impact on anarchist thought and the limitations of his idealist vision for a better society which lacked a practical roadmap for its realisation.

The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World. David Graeber. Allen Lane. 2024.

The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World coverThe Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World is a collection of previously published articles, almost all sole authored by the academic, activist and anarchist, David Graeber. Graeber’s philosophy is that everyone is an anarchist at heart: none of us like being bossed around. Though he has a point, this idea risks underestimating the degree to which people vary, and to which we can all be conditioned by our circumstances. That said, I have always enjoyed what he has to say because it is so often novel, bringing to light ideas that are rarely discussed in the academic mainstream. His influence is greater than any other recent anarchist, especially following the 2011 publication of Debt: The First 5000 years, published in the year when almost a thousand occupy movement encampments were briefly established in cities in over eighty countries. Before him,the best known modern anarchist was Colin Ward, author of The Child in the City (1978), who had a less combative style.

Graeber died four years before this latest book was published. Giving an overview of Graeber’s thinking and his contribution to anarchist thought in the text’s foreword, Rebecca Solnit writes: “In order to believe that people can govern themselves in the absence of coercive institutions and hierarchies, anarchists must have great faith in ordinary people, and David did.” What may grate on readers is Solnit’s assumption that some people are ordinary while others are great, that only some have the courage of their convictions. Graeber also moves between suggesting we can all be anarchists, to putting a few on much higher pedestals than others. At times he talks despairingly of many of his colleagues.

Solnit […] highlight[s] to readers how unusual Graeber was, but in doing so she inadvertently illustrates the tendency of anarchists to think they hold a monopoly over supposedly dangerous ideas.

(How) can anarchist thought flourish, or even exist at all, within educational institutions? Another of Solnit’s quotations of Graeber’s words in the foreword suggests that universities:

…ostensibly designed to give scholars the security to be able to say dangerous things have been transformed into a system so harrowing and psychologically destructive that, by the time scholars find themselves in a secure position, 99 percent of them have forgotten what it would even mean to have a dangerous idea.

What’s clear in this quote is a strong criticism of the type of thinking institutions foster, and of the vast majority of what he considers to be his misguided academic colleagues who capitulated to it. Solnit selects this claim to highlight to readers how unusual Graeber was, but in doing so she inadvertently illustrates the tendency of anarchists to think they hold a monopoly over supposedly dangerous ideas.

When we get to the actual meat of the book, a collection of essays ranging on topics from inequality and technology to democracy and protest, there is much to be recommended. It begins with a discussion that includes issues of tolerance, mutual accommodation and kindness; moves on to have a pop at Eurocentrism and especially the: “Eurocentric variety represented by Kant or Zižek” (46). (Ironically, there is a notable Americentrism to most of the works in the collection and perhaps to the kind of anarchism he espoused.)

We find details of his own background, his grandfather’s university degree, and some very honest and open autobiography about his experience of: “bounc[ing] back and forth” between different state and private institutions (60). Interestingly, in other sections, as well as in a 2014 Op-Ed in The Guardian, he frames himself differently, foregrounding his identity as the “child of a working-class family”. We get a sense from the writings in this collection that Graeber had a split view of himself, working-class sometimes, child of the elite at others. In a way he was the child in the city who was the most famous cheerleader of the children who flocked to camp in the cities in 2011.

His ideas sometimes feel utopian, leaving others to think through the messiness of implementation

Graeber was often bullied as a child and turns the memories of that, along with a little research, into an anecdote. These experiences appear to have had a significant impact on his thinking. At one point he writes: “It turns out that most bullies act like self-satisfied little pricks not because they are tortured by self-doubt, but because they actually are self-satisfied little pricks. Indeed, such is their self-assurance that they create a moral universe in which their swagger and violence becomes the standard by which all others are to be judged; weakness, clumsiness, absentminded-ness, or self-righteous whining are not just sins, but provocations that would be wrong to leave unaddressed” (185). His broader philosopher describes a world of mostly good people, ordinary people, dominated by a few bullies; if we could only see through them and understand that their power relies on our complicity and subservience, we would uncover a truth usually hidden from us.

Graeber offers a very wide definition of what it is to be an anarchist, one he first published in 2000, defining them as “simply people who believe human beings are capable of behaving in a reasonable fashion without having to be forced to” (243). They are the ordinary people who “can organise themselves and their communities without needing to be told how [… and] power corrupts” (244). There is something evangelical about Graeber’s anarchism, but also something a little naive. In another definition of an anarchist, he uses the analogy of someone who refrains from elbowing his way to the front of the bus queue, without the need of an enforcing police presence. But what occurs when someone does get an elbow in the face, or is pushed under the bus? His ideas sometimes feel utopian, leaving others to think through the messiness of implementation, like his idea for blowing up endless office blocks, the hallmarks of capitalism, that crowd our cities, and replace them with “museums of care” that could become free universities, social centres and shelters for those in need. But how would such spaces run, who would fund and clean them? Would they really police themselves

In a commentary on Abdullah Öcalan’s political thought, published only a few months before he died, Graeber suggested that “it might be curious to ask ourselves how much time would have to pass or what would have to happen for the intellectual world to treat Öcalan’s ideas in the same way that they do those of Walter Benjamin, Georges Bataille, Simone de Beauvoir, or Frantz Fanon—to name a few politically engaged scholars who were neither party leaders nor academics—or even a theorist comedian like Slavoj Žižek…”

Perhaps Öcalan’s words will change the world, or how we think of the world, but more likely they will be forgotten. Graeber’s might also change the world; but if they do, it may not be as he expected. The “ultimate hidden truth” could be that underlying modern anarchism is a particular naivety to which this book is a good guide. Perhaps it is possible to organise ourselves and our communities with very few police, but it’s hard to imagine we can do without them entirely. Achieving this is not possible with ideas alone, with a wing and a prayer, but would require transformative collaborative action. Just as Ward’s The Child and the City is little remembered or discussed today, it is equally possible that this collection, and Graeber’s many other books, will become absorbed into wider thinking and understanding around anarchism. It may not be the ultimate hidden truth it purports to be, but rather a step on the way to more effective political action.

Note: This review gives the views of the author (Danny Dorling) and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

For a PDF of this article and where it was first published click here.

November 11, 2024

Rethinking tomorrow for the next generation

In many ways in the UK, we are currently at a peak of injustice and we have to choose which to turn. We could take the US route and following the United States of America up an even higher peak, or we could turn in another direction.

Reducing injustice does not mean that all suddenly becomes fine. It means that more victories are being won than defeats are occurring. But life can, and usually does, feel worse when you begin to come down from the peak of inequality, as it did in the UK in both the 1920s and the 1930s. Globally, there are also more victories now than defeats.

Extreme poverty is falling across most of the globe; but we do not know if we are at a peak of injustice worldwide. As Oxfam explained at the start of 2024 in regard to the global situation: ‘Extreme poverty leapt up during COVID-19, and whilst it began to fall again, it is nowhere near its pre-crisis trend, and the impact of the global food and cost of living crisis is likely to have a further negative impact.’

Infant mortality is definitely falling worldwide, while access to education, better housing and better healthcare are – on average – all still rising. We cannot now claim that each passing year is worse than the one before, as we could do when the pandemic hit in 2020, and even more so in 2021. We could do so when the wealth of billionaires was skyrocketing; it is plateauing now. We could do so when tens of thousands were dying in natural disasters for want of basic infrastructure, warnings and concern. We can’t say that now.

The situation could worsen. Dystopian predictions abound. Wars begin, new genocides are committed. Despots get away scot-free, or even become the president of the United States. Corporations still rule the world. The planet is certainly warming and the weather is becoming more erratic. And yet most years are now better than the year before, for most of us in the world. Pandemics that kill many people are becoming less, not more, prevalent, despite our huge populations.

Democracy is not collapsing worldwide. Greater rights for women continue to be won, with more victories each year than defeats. The 2022 overruling of (Roe v Wade) abortion rights in the US impacted upon only two per cent of the world’s people, the women of the USA.

In 1913, at the age of 32, The Oxford academic R. H. Tawney explained that what thoughtful rich people call the problem of poverty, thoughtful poor people call with equal justice a problem of riches … those of us who spend time considering ‘what we can do for the poor,’ would be better occupied in reflecting what the poor ought to do with us. And in the late 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. quoted the solution proposed by a US official, the assistant director of the Office of Economic Opportunity, Hyman Bookbinder: ‘the poor can stop being poor if the rich are willing to become even richer at a slower rate’.

Facebook’s (now Meta’s) US co-founder, Chris Hughes, gladly tells people he has just been lucky, not talented: he happened to share a room with a geek who came up with the idea of writing a computer programme to mimic an American university tradition, the ‘college face-book’. Of course, it was not just luck. It was also inherited wealth that put the two of them at Harvard, an ultra-elite and expensive university.

Mark Zuckerberg and Hughes even attended the same private prep school, so it was not exactly the craziest of coincidences for these two young men, who had led the same life as teenagers, to end up in the same room on campus. However, rising above his privilege, Chris later in life, along with eighteen other American multi-millionaires and billionaires, has called for the USA to have a substantial wealth tax so that the ‘fortunate’ rather than the less fortunate are those who mostly pay for state spending. Among the signatories to his wealth tax proposal were not only those like Hughes who had had the privilege – or luck – to network as students with fellow future tech entrepreneurs, but also those who had inherited enormous family businesses, such as Abigail Disney. There could easily be many more such enlightened and extremely affluent people in the future.

What would it take for Britain, to shift even marginally (at first) from so much extreme competition to more cooperation and compassion? Compassion comes through understanding people, not numbers. But without the numbers we would know so much less.

It was through the crushing of compassion, the evisceration of empathy, that enough of our children’s grandparents were tricked into believing that there was no such thing as society. Their children suffered. Their grandchildren live parallel lives as a result, making them the most divided children in Europe, and the most divided British children for almost a century.

No child in the UK should have to go without necessities. Every child should at the very least be able to enjoy a single week of annual holiday (not only staying with family or friends).

What our society needs, and our children need, is for you and me (and enough of the new British government) to care for them now, to care enough, to give a damn, to see that their lives – each one of them – are perfectly ordinary. It is the place and time they have been born into that is extraordinary. As yet, the new Labour government has proposed to introduce few measures that will increase fairness and reduce inequality for the children of the UK.

The text above is an edited extract from pages 188 to 189 of ‘Seven Children’.

—

Radix is the radical centre think tank. We welcome all contributions which promote system change, challenge established notions and re-imagine our societies. .

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here.

October 29, 2024

Review of ‘Wealth, Poverty and Enduring Inequality’ by Sarah Kerr, ‘Let’s talk about wealth, baby’

.. let’s talk about you and me;

let’s talk about all the good things,

and the bad things, that may be….

A new book examines the self-sustaining dynamic of extreme wealth and its political influence. Is it time to switch our focus from the problem of poverty to the problem posed by the rich?

Review of Wealth, Poverty and Enduring Inequality: Let’s Talk Wealtherty by Sarah Kerr (Policy Press, 2024)

Introducing a new word into the English language is no easy task. A colleague of mine claims that a medical paper he coauthored years ago was the original source for the phrase “vanilla sex,” originally referring to sex unlikely to result in much calorie-reducing physical exercise.

While the definition of vanilla sex remains somewhat vague, “wealtherty,” by contrast, was clearly and thoroughly defined in the 2021 article that was the prelude to Sarah Kerr’s 2024 book, Wealth, Poverty and Enduring Inequality: Let’s Talk Wealtherty:

“I am proposing a pivot to a new articulation of the problem: wealtherty. Wealtherty is the state or condition of prosperity in abundance of possessions or riches, plus concomitant political power and influence, and resultant risks to the democratic process. This articulation assumes that the social (of social policy) is made up of richer and poorer people. It assumes that there is such a thing as morally and politically unjustifiable surplus wealth and that this wealth bleeds into socially damaging political influence. It assumes that the existence of surplus wealth in conditions of urgent unmet needs is intolerable. It assumes a set of restricted capabilities (such as media and political influence) that are usually only accessible to those with money and influence, and which, in their operation, can cause harm to others. Finally, transposing theories of privilege from race, wealtherty exists when this dynamic is self-sustaining and has made itself invisible – a form of wealth privilege, which makes it unlikely that beneficiaries of the system will be motivated to enact change.”

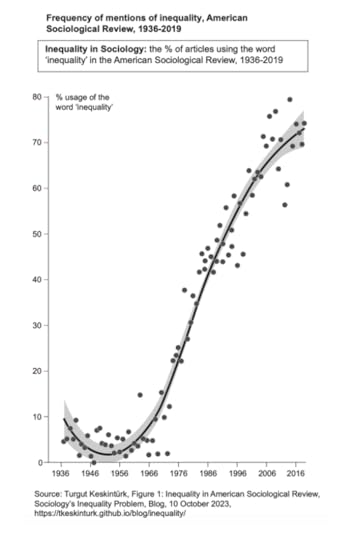

Example of the rise in interest in inequality

In a few years, like vanilla sex, wealtherty might also find itself in common use — but that will depend on whether others begin to adopt the word. I think it might have been better had the book simply been titled The Rich: Wealth, Poverty and Enduring Inequality. But I could be wrong.

There are, of course, many books whose titles play on the phrase “the rich.” I own a few of them myself. The one I have enjoyed the most, George Kirstein’s The Rich: Are They Different?, was first published in 1968. I enjoyed it both because so much of what it says remains true today and because it shows that society’s critics managed to dislike the greed and duplicity of the wealthy at a time when their riches were at a historical low. By “low,” I mean the lowest in all of recorded world history.

One of the main differences between the wealthy of half a century ago and today is the shamelessness with which the wealthy now boast about their filthy lucre. Conversely, Kirstein’s book noted that in the 1960s in the United States, “the rich dislike being set apart from the rest of society; they do not talk about their wealth, indeed they often deny possessing it; they are quite aware that their problems and concerns are laughable to the vast majority of their fellows.”

One of Sarah Kerr’s achievements in Wealth, Poverty and Enduring Inequality (Wealtherty, for short) is to illustrate that today’s rich are less self-aware — less conscious, more socially oblivious — than their equivalents were in the 1960s.

The Wealth Problem

It’s rare for an academic book to deliver on its promises, but this one largely does. Kerr defines her terms as clearly and concisely as possible and is quick to explain that the book “is normative (wants to change things) as much as sociological (interested in how and why things exist like they do) and there’s little point wanting to change things, but then only talking to people who already know what you’re talking about.”

But why the subtitle, Let’s Talk Wealtherty? The book’s central argument is that poverty is no longer a helpful concept — it has outlived its usefulness. Our problem now is not the poor; it is the rich. Instead of looking down, we need to look up. We need to focus on the lived experience of the rich who cause harm and listen to what they have to say about why they do it. If we truly care about inequality and about poverty, we should have our eyes firmly focused on the rich — we should focus on the carriers of the disease, not the symptoms. As the graph I have provided here shows, drawn from a study originally reported only in grey literature, sociologists now understand that inequality matters. Kerr’s claim is that the sociologists, and all of us, have not been paying enough attention to the rich.

Kerr opens with R. H. Tawney’s 1931 statement on the “problem of riches” — “what thoughtful rich people call the problem of poverty, thoughtful poor people call with equal justice the problem of riches.” Tawney’s observation highlights the social and economic power structures that define how we think about wealth, which is a concept echoed in older activist academic statements that now seem obvious but were revolutionary in their time. For example, Karl Marx’s 1852 remark about the events of November 9, 1799 — “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past” — underscores how the structures of wealth and power are inherited from previous generations, constraining individual and collective action.

Whatever one thinks of the old Rhinelander, his omission from Kerr’s text is glaring, given Marx’s centrality to discussions of wealth distribution. Most commentators make at least one nod in his direction. Yet there is only one brief reference to Marxist historians, dated 1975, and one mention of a book that touches on Marx, gender, and feminism.

When Sociology Meets Fine Print

After a rollercoaster start, Wealtherty settles down into the very densest of literature reviews. Kerr makes sweeping claims about the need for a fundamental shift in the focus of British sociology, so it makes sense that she wants to demonstrate the thoroughness of her research. But only a few future PhD students will find the exhaustive list of sources useful — there are some thirty-nine sources cited on page fifteen alone. This isn’t meant as criticism, just an observation: the small print is in your face, which may reassure some readers but put off others. Similarly, and in contrast with the dearth of Marx citations, the literature review features a heavy dose of Michel Foucault, with nine of his works cited throughout.

If we truly care about inequality and about poverty, we would have our eyes firmly focused on the rich.

While transparency about one’s approach, understanding, and sources may be commendable, much of this earlier material might have been better suited to an appendix for the more curious readers to turn to if they wished. Some will likely give up by page twenty-two, after wading through dense paragraphs with lines such as, “Without wishing to overtheorize the Tōhaku image, the trees on the left might be considered to visualize Savage’s understanding of duration.” These asides can be frustrating because there is much that is of great value in the book. A careful editor could have rearranged or trimmed some sections and suggested maintaining the engaging tone of the book’s beginning throughout.

The UK usually ranks as the most economically unequal country in Europe by income distribution.

Henry Nicholls / AFP via Getty Images

Language matters, as Wealtherty explains at length. At times, though, especially in the sections on the history of wealth and poverty studies, I couldn’t help but feel the intended audience was almost entirely academic. However, by the time we get to part two, we dive into the story of recent British politics and the rise of think tanks designed to spread harmful ideas to provide cover for their rich masters — an excellent and engrossing account. But it did leave me wondering: Why did these groups find such success in Britain, compared to other European countries?

Wealtherty rarely steps beyond the small island of Britain, which is useful in some ways. It’s satisfying to have concise biographies of some of the most hideous characters in all of recent British history collected together in one place. However, what’s missing is an explanation of why these people were taken seriously in the first place. While their vicious, antisocial conduct is made clear, the book doesn’t quite explain what made them that way and what made their ideas socially acceptable. For details on who these people are, you’ll have to read the book yourself — it’s worth it for the brilliant photographs, the diagrams, and portraits of the rich, which vividly capture their power over, and poorly disguised contempt for, others. This book provides brilliant insights into the current state of Britain — a very sad story.

The Different Faces of Inequality

Wealtherty contains some international comparisons. One of the book’s graphs shows curves from the 2018 World Inequality Report, which depict similar inequality trends in the United Kingdom and United States as in Spain, Japan, France, and Germany. But the way the wealthy use their power — and are permitted to be powerful — varies country to country. In some places, such as some parts of the UK, landowners might control vast wealth, but others have rights to access and use their land for things such as hiking, requiring landlords to ensure safety and upkeep. The creates a different balance of power, even if the wealthy appear equally rich in monetary terms.

While the United States is now one of the most unequal countries in the rich world, it was far more equitable in terms of income and wealth in the 1960s.

Public wealth may have fallen in all the countries included in the World Inequality Report Kerr cites, but public spending has risen across the board — though less so in the United Kingdom and United States. More could have been made of these international comparisons, rather than simply suggesting that Britain’s story is mirrored elsewhere. Interestingly, the latest World Inequality Report (2024) shows a sharp and sudden drop in the UK’s top incomes derived from wealth holdings, a trend not seen elsewhere. We don’t yet know why this is happening — or how accurate these findings are — but hopefully this book will be updated in a future second edition to address this very recent change.

Jumping to the conclusion, the book calls for defining extreme wealth as a social problem and debunking the myth that inequality can ever be benign. However, some of the proposed solutions, including reserving spots at elite universities for the “top one or two pupils from every school” assumes that such top students exist in all schools and that maintaining a hierarchy among universities is a good idea.

On this score, Wealtherty itself could use some debunking. Schools don’t contain inherent “top” students — only those elevated by the prevailing norms of the day.

Kerr’s Sociological Review article, which this review opened with, concludes by calling for the rejection of “poverty as the articulation of our social problem tout court and move on.” The phrase “tout court” means with no addition, with no qualification — simply and completely. This may feel harsh, considering how hard British academics fought in the 1980s to reclaim the word “poverty” after it was effectively banned by Mrs Thatcher’s government. Then again, her government would have loathed this book’s focus on the rich — and it is a very much needed survey of their depredations.

As George Kirstein’s 1968 book on the rich I mentioned earlier made clear, the rich are different from us because “they have enough money.” No individual needs more than what the richest tenth of people had in the United States in 1968. While the United States is now one of the most unequal countries in the rich world, it was far more equitable in terms of income and wealth in the 1960s (though not in terms of race or gender). The UK, too, was much more equal then. Today it ranks as the most economically unequal country in Europe by income distribution, occasionally competing with Bulgaria for the top slot.

Wealtherty is especially timely in light of this shift. It was written as the UK took a radical turn, with its leading political party adopting some of the most extreme positions of any party in a wealthy or middle-income country on the planet. The book effectively shows that this political leap wasn’t accidental but a direct result of the pernicious influence of a small group of the extremely rich and their enablers.

For a PDF of this review and where it was originally published click here.

Peak Injustice and Seven Children

By 2023 the latest statistics, looked at in the round, began to suggest that it was not fanciful to believe that we had seen income inequality peak in 2018 and wealth inequality peak shortly afterwards. In early 2024 The Times reported that: ‘Some major UK employers spend tens of millions on two or three executives alone. This inevitably means there is less available for their lower-earning colleagues.’ This gross economic inequality was not just as measured between individuals but included income and wealth inequality between areas becoming extreme. How we treat others, what we tolerate and ignore, is at the core of injustice.

So why write a book on peak injustice now? The title comes from a Guardian article published in 2017, ‘We’ve hit peak injustice’, in which Hugh Muir explained that:

‘Revelations about the wealthy buying citizenships confirm a sorry truth: the migration door, closed to the poor, swings open to those with vast fortunes… In our regression from liberal aspiration to the brutal realities of Trump and Brexit, one of the nirvanas set aside has been the notion of a world without borders. ‘America first,’ says the president. ‘Britain first and always,’ chant the Brexiters. The majority demand is for migration curbs in principle, even if they are unlikely to be achieved in practice. The global village will be refashioned with barbed-wire fencing. And yet in this, as in most things, money talks.’

The Labour Party had become just as divided as the Tories by 2023 and into 2024. Although they presented a more unified public face, they had become run by zealotry, paranoia, and a command-and-control style that backfired and looked weak. Even when this ensured an election victory on 4 July 2024, what was actually won?

Voters in the 2023 Uxbridge and South Ruislip by-election explained to the BBC that the Labour Party ‘don’t offer anything new, exciting or different’. Labour Party members felt that they ‘were just fodder’ for a central party machine not interested in them.

Looking back over the past half-century, we could choose any one of a number of examples of people saying extreme things and claim each as evidence that a peak of injustice had been reached. It would not have been. Attacks have been made on political parties for selling out their principles in every decade of the past 50 years.

No matter how much of a betrayal or provocation the latest government announcement may appear to be, why should we take any such claims today with anything other than a pinch of salt? Even as the articles and books began to be printed thick and fast suggesting that we really had got it all wrong by not fixing the roofs of our school and hospital buildings before they began to crumble, and the insulation and heating in our homes before the mould spread, let alone our broken society before it fractured, it began to become clear that we were no longer easily shocked.

When the new government was formed in July 2024 few people had great expectations, despite the opportunities there were. Taxes in the UK now amount to 37 per cent of national income: ‘the highest level seen in the UK since the 1940s’. Yet that is less than almost any other country in Europe secures – apart from Ireland and Switzerland, where the tax take looks low because so much money today passes very lightly taxed through those economies. The UK can no longer even excel at financial chicanery.

Meanwhile, despite these higher UK taxes, the roofs on a growing number of our school buildings were threatening to literally fall down on the heads of children, because the austerity government had not fixed them while the sun was shining, despite spending more on ‘defence’ than it had done for many decades and then promising in 2024 to increase such spending further. One right-wing Labour politician, talking about the war in Ukraine, tried to suggest that all these arms exports and military posturing were about ‘desiring goodness for all mankind’.

You might believe that there is no way we could have reached the peak of injustice when we were selling more of our weapons abroad, and as the chances of those weapons being used rose, as hunger increased at home, as more and more schools were shutting because they were unsafe, as once again more and more people were sleeping rough, and then, with an accelerating boost from the cost-of-living crisis, as the black mould spreading in increasing numbers of unheated homes made more people ill, sometimes fatally. Thus, when all this was occurring, and inflation remained high, we could clearly see that our situation could still get worse.

Things will cost still more next year (inflation is unlikely to become negative). So, you might well ask, how can we be at a peak of injustice now? My answer is that we have been at such peaks before. Reducing injustice does not mean that all suddenly becomes fine. It means that more victories are being won than defeats are occurring. But life can, and usually does, feel worse when you begin to come down from the peak of inequality, as it did in the UK in both the 1920s and the 1930s. Globally, there are also more victories now than defeats.

Extreme poverty is falling across most of the globe; but we do not know if we are at a peak of injustice worldwide. As Oxfam explained at the start of 2024 in regard to the global situation: ‘Extreme poverty leapt up during COVID-19, and whilst it began to fall again, it is nowhere near its pre-crisis trend, and the impact of the global food and cost of living crisis is likely to have a further negative impact.’

Infant mortality is definitely falling worldwide, while access to education, better housing and better healthcare are – on average – all still rising. We cannot now claim that each passing year is worse than the one before, as we could do when the pandemic hit in 2020, and even more so in 2021. We could do so when the wealth of billionaires was skyrocketing; it is plateauing now. We could do so when tens of thousands were dying in natural disasters for want of basic infrastructure, warnings and concern. We can’t say that now.

The situation could worsen. Dystopian predictions abound. Wars begin, new genocides are committed. Despots get away scot-free. Corporations still rule the world. The planet is certainly warming and the weather is becoming more erratic. And yet most years are now better than the year before, for most of us in the world. Pandemics that kill many people are becoming less, not more, prevalent, despite our huge populations.

Democracy is not collapsing worldwide. Greater rights for women continue to be won, with more victories each year than defeats. The 2022 overruling of (Roe v Wade) abortion rights in the US impacted upon only two per cent of the world’s people, the women of the USA.

Today, the British government is led by a man who, in 2020, ‘was running late for an appointment with his tailor’ when he struck a cyclist. The cyclist, said by eyewitnesses to have been a food delivery rider for Deliveroo, had to be taken to hospital. The reporter suggested that the new Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer, was performing a U-turn when he hit the cyclist, who had shouted at Starmer, ‘How did you not see me?’

Not seeing is the problem.

In 1913, at the age of 32, The Oxford academic R. H. Tawney explained that what thoughtful rich people call the problem of poverty, thoughtful poor people call with equal justice a problem of riches … those of us who spend time in considering ‘what we can do for the poor,’ would be better occupied in reflecting what the poor ought to do with us. And in the late 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. quoted the solution proposed by a US official, the assistant director of the Office of Economic Opportunity, Hyman Bookbinder: ‘the poor can stop being poor if the rich are willing to become even richer at a slower rate’.

Facebook’s (now Meta’s) US co-founder, Chris Hughes, gladly tells people he has just been lucky, not talented: he happened to share a room with a geek who came up with the idea of writing a computer program to mimic an American university tradition, the ‘college face-book’. Of course, it was not just luck. It was also inherited wealth that put the two of them at Harvard, an ultra-elite and expensive university.

Mark Zuckerberg and Hughes even attended the same private prep school, so it was not exactly the craziest of coincidences for these two young men, who had led the same life as teenagers, to end up in the same room on campus. However, rising above his privilege, Chris later in life, along with eighteen other American multi-millionaires and billionaires, has called for the USA to have a substantial wealth tax so that the ‘fortunate’ rather than the less fortunate are those who mostly pay for state spending. Among the signatories to his wealth tax proposal were not only those like Hughes who had had the privilege – or luck – to network as students with fellow future tech entrepreneurs, but also those who had inherited enormous family businesses, such as Abigail Disney. There could easily be many more such enlightened and extremely affluent people in the future.

What would it take for Britain, to shift even marginally (at first) from so much extreme competition to more cooperation and compassion? Compassion comes through understanding people, not numbers. But without the numbers we would know so much less.

It was through the crushing of compassion, the evisceration of empathy, that enough of our children’s grandparents were tricked into believing that there was no such thing as society. Their children suffered. Their grandchildren live parallel lives as a result, making them the most divided children in Europe, and the most divided British children for almost a century.

No child in the UK should have to go without necessities. Every child should at the very least be able to enjoy a single week of annual holiday (not only staying with family or friends).

What our society needs, and our children need, is for you and me (and enough of the new British government) to care for them now, to care enough, to give a damn, to see that their lives – each one of them – are perfectly ordinary. It is the place and time they have been born into that is extraordinary. As yet, the new Labour government has proposed to introduce few measures that will increase fairness and reduce inequality for the children of the UK.

The text above is an edited extract from pages 13 to 21

of ‘Peak Injustice’ and pages 188 to 189 of ‘Seven Children’.

T hose two books contain the references for all quotes and other claims made above.

See: https://www.dannydorling.org/books/sevenchildren

And For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click…..> here.

October 10, 2024

Students protests and autumn 2024

All around the world, on every continent and in most major cities, university students in 2024 established peace encampments to draw attention to the ongoing horrors taking place in Gaza. They were calling for their universities to disinvest in the arms trades involved, and not to try to claim neutrality through their silence.

The United States of America was then led by a man, Jospeh Biden, unable to string a sentence together whose wife, on the 1st of July, told Vogue Magazine (of all outlets), that his family… “will not let those 90 minutes define the four years he’s been president”. Within a few weeks he declared he would no longer stand again for president.

The Prime Minster of United Kingdom at the time, Rishi Sunak, on the same day, told Sky News that he had ‘genuine concern’, as it looked as if he was going to tank in the election in three days’ time, ‘for the UK’s security in the event of a Labour win in the general election.; he tanked. The new Labour government only altered UK foreign policy slightly announcing that some arms could no longer be sold to Israel.

A day later, on the 2nd of July, it was Khan Younis was again being bombed and refugees were having again to flee. There had been no abatement in the collective punishment despite, on 24 May 2024, the World Court ordering that ‘Israel immediately halt its military offensive, and any other action in Rafah, which may inflict on the Palestinian group in Gaza conditions of life that would bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”.

Around the same time, in the New York Review of Books, Aryeh Neier, the co-founder of Human Rights Watch, wrote that that he is “now persuaded that Israel is engaged in genocide against Palestinians in Gaza”. Israel had become viewed globally as a pariah state. It closest ally was the most powerful nation on earth, The USA, was led by someone who almost everyone agreed needed to be quietly taken aside and looked after. While within Israel’s second closest ally, the credibility of the prime minster became the worse ever recorded in polling (which began in 1979).

Amid all this chaos, on University campuses across the Western World, and especially in the USA and the UK, the students were learning not only of the incompetency and complicity of the political leaders of their countries; but also, that very often, when it comes to the issues that matter most, university management does not necessarily tell the simple truth. That was an education for the students.

University management at times informed the students that they wish to focus their efforts, alongside the students, on the practical things that we can collectively do to make a difference. But do they really? Management try to divide and rule, suggesting that some students are making inaccurate statements and claims about the University.

Management says that the University has always respected the right to peaceful protest by students and staff. Management claim that it is deeply regrettable that protestors have gone beyond a line. But have they? Who drew the line? If management call the police, many students can (and did) end up in police cells. That fact, the students never forget; and their friends do not forget either; or their families; or all the other students on campus who see and hear what has happened. In my own University of Oxford all the charges against the arrest students were dropped. So were the arrested wrongful?

The students are learning that some of those who rule over them are now afraid. But they are also learning about how university management first employs the well warn tactic or trying to exhaust their opponent.

Perhaps management in other universities might learn and might talk instead of

ignoring their students? Were management too afraid to negotiate? Did those

few at the top in their huddled discussions genuinely tell each other that they thought this will wear out soon? Were the university managers ordered by their political masters, the politicians, not to talk to the students?

I am now writing in the autumn of 2024. The bombs are falling on Lebanon and well as Gaza. The students are back on their campuses. There is a new prime minster in place in the UK and soon there will be a new president elect in the USA. The Middle East is on the edge of a wider war.

It is reported now that: ‘… across the US, some university administrations have turned to “dialogue” as the way forward. They’re hoping that getting students talking to each other will serve as a salve for the turbulence of the last year, with its dramatic resignations, canceled graduations and thousands of arrests – as well as a deep disillusion among students with their universities’ ability to provide direction at a time of crisis.’

As I write, in October 2024, we do not yet know what the reactions of UK university managers will be when the protests begin again, when the thousands of names of the dead begin to be read out again; when students boycott teaching for a day; when they pitch their tents again – even perhaps in the cold of northern winters. But we do know that the more able to university authorities are beginning to realize that that dialogue will be less damaging to them than simply calling in the police. And that if the police are called they will now be much more reluctant to arrest students than they were earlier in the year.

In October 2024 police were called to a protest at the university of Manchester against the University’s ties with the arms industry, and possible links with the atrocities being committed, amongst much else. Or as the press reported ‘to protest against the establishment’s ties with BAE systems and Israeli universities they say are built on occupied land’. No arrests were made.

For a PDF of this publication, additional source material, and a link to where it was first published click here.

Protests in Malaysia

September 17, 2024

Getting shorter and going hungrier: how children in the UK live today

…why did this happen to our children? This rise in child poverty is a change that has not been found to have occurred to the same extent anywhere else in the world, among all the places that the United Nations measures in the same way.

Getting shorter and going hungrier: how children in the UK live today

Danny Dorling, University of Oxford

Children’s lives in the UK are changing.

They are becoming shorter in height. More of them are going hungry than they were a few years ago. Recently, more have died each year than they did a few years ago. Increased poverty, more destitution and the effects of ongoing austerity are the clear culprits.

But why did this happen to our children? This rise in child poverty is a change that has not been found to have occurred to the same extent anywhere else in the world, among all the places that the United Nations measures in the same way.

Change in child poverty, 2012–14 to 2019–21

UNICEF Innocenti—Global Office of Research and Foresight (2023) ‘Innocenti Report Card 18: Child poverty in the midst of wealth’, CC BY-NC-ND

UNICEF Innocenti—Global Office of Research and Foresight (2023) ‘Innocenti Report Card 18: Child poverty in the midst of wealth’, CC BY-NC-ND

The above graph tells a story of hope and success. In much of Eastern Europe, child poverty has fallen by between as much as a third – and often at least a quarter – in a mere seven years.

But it also shows that child poverty has risen the most in the UK. The poorest fifth of households in the UK are poorer than the poorest fifth in most of Eastern Europe. For many people in the UK, this will come as a surprise. Some will refuse to believe it can be this bad.

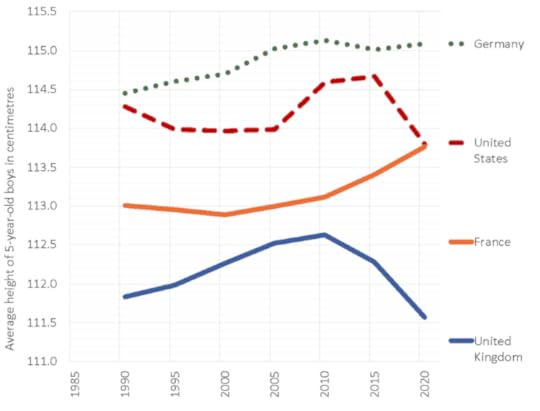

The evidence for this poverty is seen in the declining heights of five-year-olds since 2010.

Average height of five-year-old boys, 1985–2020

Average height of 5-year-old boys, 1985–2020.

Average height of 5-year-old boys, 1985–2020.Redrawn by the author from data in Press Association (2023) ‘British children shorter than other five-year-olds in Europe’, ITV News, 21 June., CC BY-NC-ND

A 5-year-old in 1990 would have been born in 1985 and their height influenced mostly by nutrition in the years 1985–1990. Those were hard years for the UK: mass poverty resulting from over three million people being out of work in the early 1980s. But the average height of children was still increasing.

It was not until 2010, for those children who had lived between 2005 and 2010, that we first saw heights plateau and then fall, coinciding with the post-2010 austerity years.

Seven Children: Inequality and Britain’s next generation.

My forthcoming book attempts to make sense of what has happened to the UK: why, in 2024, it is not merely one of the countries in Europe with a high rate of child poverty, but the one country above all others that the UN has singled out as having had the greatest rises in child poverty among all those it surveyed.

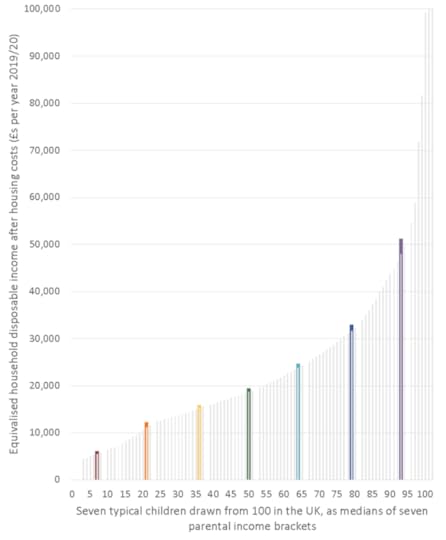

Seven children

To try to understand more about children’s lives in the UK, I constructed seven typical children. I divided all 14 million children living in the UK into seven groups of 2 million, according to the income of their families in 2018 and 2019. I then chose the middle child of each 2 million. I next looked at what had happened to those families between 2018 and 2024.

The graph below shows the annual income of each of the seven households the children were drawn from.

Annual household incomes after tax, benefits and housing costs in the UK, families with children 2019/20

Annual household incomes after tax, benefits and housing costs in the UK, families with children 2019/20: seven typical children marked in colour.

Annual household incomes after tax, benefits and housing costs in the UK, families with children 2019/20: seven typical children marked in colour.Danny Dorling, CC BY-NC-ND

The first thing to note is just how incredibly well-off the children are who are better-off than our seven typical children.

Some 6% of all children in the UK live in households richer than the best-off typical child in my analysis. Those 6% of children, the best-off children of all, live in families that each year receive and spend a third of all the income in the UK.

Front and back cover of the book – seven children.

These 6% are not typical, and neither are the 6% poorest: those most destitute, those whose families are most likely to use food banks. If you pick seven typical children, equally spaced out across the income scale, then these extremes are not part of what you see.But four of our typical seven children now live lives that most better-off people would consider to be in poverty. The other three are hardly well-off.The least well-off are in families struggling to pay bills and making sacrifices others do not have to think about. For instance, whether to save £10 a month, or have insurance against the effects of flood, fire or theft. Increasingly often they cannot afford both.

But even the most well-off of our seven children lives in a family that worries about paying for an annual holiday. That is rare among the most affluent two million families, but possible.

The UK in 2024 demonstrates to the world what living with high inequality means in a once affluent country. It means a few using up far more resources than the vast majority of other children, such as having access to many more school teachers – per child – as compared to the rest, better food, better shelter, more warmth, more toys, better material everything; often more than you might think any child needed.

In future, almost all our children will tell their stories of growing up in the UK of the 2020s and – hopefully – what changed to make things better. It is hard to imagine them becoming much worse.

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For a PDF of this article and a link to the original publication click here.

August 30, 2024

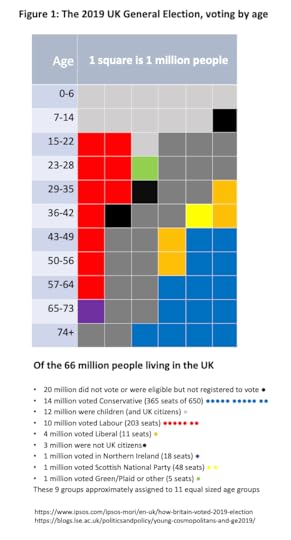

The 2024 UK General Election result by age group

Five years ago I drew a diagram to illustrate why age was such an important factor in determining the result of the previous, 2019, UK General Election. It was first shown in Public Sector Focus and contained 66 squares. Each square represented one million people living in the UK. At that time, there were about 66 million people resident in the UK. Some 20 million were adults who chose not to vote, or were eligible to vote but had not registered to (and so could not vote even if they had wanted to). Apathy was quite high in 2019; much higher than it had been in 2017.

The Conservatives won that election because, to the nearest million, 14 million adults chose to vote for them. As Figure 1 shows, most of those who did were old or very old.

The next largest group of people in the UK were 12 million children who were also UK citizens. They include more than a million 16 and 17 year olds who, one day, may be allowed to vote. Labour came fourth in 2019, after the non-voters, the Conservatives and the children, with 10 million votes. It was an impressive tally, but the votes were in the wrong places and too spread out over the age groups so the Labour party won only 203 seats in the House of Commons. Voters tend to concentrate in places by age and so, if you secure a great many votes of a particular age group, you can win more seats.

The fifth largest group were the Liberals, the sixth were people who were not UK, Irish or ‘qualifying’ Commonwealth/EU citizens and so could not vote, and the three remaining groups only secured, to the nearest million, one million votes each.

Figure 1: The 2019 UK General Election, voting by age

Figure 1: The 2019 UK General Election, voting by age

The 2019 General Election was, above all, an election about age. The old won it. More of them turned out, and their votes tended to be geographically concentrated in areas where people retire to. This included many of the red wall seats which were usually in slightly more affluent parts of the north of England to which people were, in increasing numbers, retiring.

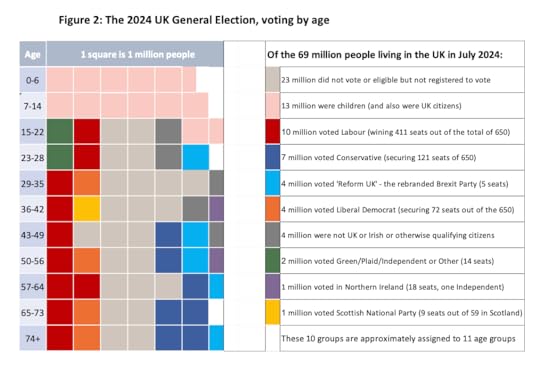

So, you may be wondering, how did the picture change in the subsequent five years when we look again at voting by age in exactly the same way? To answer this, I have redrawn the diagram to show the 2024 UK General Election result below, in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The 2024 UK General Election, voting by age

Figure 2: The 2024 UK General Election, voting by age

The first point to note about Figure 2 is that the age groups no longer contain almost exactly the same numbers of people. We have had fewer babies in the last five years and so the age group 0-6 now has only around 5.5 million members, not 6 million. However, a little net positive immigration and some ageing means that the older age groups all tend to now contain 6.5 million people rather than 6 million. This is not the case for the age group 23-28, a great many of whom left during the pandemic and because of Brexit and never came back. Similarly, the age group 65-73 has not grown in size because of few births after the post-world-war-two baby boom (they were born later, in the 1950s). Overall, though, there has been less emigration of families with children – emigration became harder after Brexit. Our adult population has grown by two million, and most of that is of people aged over 29 (see Table 2). This is because of ageing and less emigration. But what is most interesting in Figure 2 is not our changing demographics, but how our voting patterns have changed.

The greatest change is that three million fewer people chose to vote in 2024 as compared to 2019. There was a huge growth in apathy. In every single age group, apart from people aged 65+, more adults chose not to vote than to vote for any political party. At age 65+ a majority still chose to vote for the Conservatives, but that was a depleted majority (see Table 1). The Conservatives lost to apathy, and to a new alternative being offered to them. That new alternative was not Labour, even though Labour was presenting a very conservative ‘offer’.

The Labour vote actually fell between 2019 and 2024. It fell most amongst the young and overall, despite increasing a little among those aged 57-64. One result was that Labour now had a similar level of support across the whole age range. In normal times this would not be an effective way of wining seats; but the 2024 General Election was not normal. What made the election abnormal was a re-branded Brexit Party standing as ‘Reform UK’ in almost every seat in the mainland of the UK. This party took almost 4 million votes, mainly off the Tories, who lost another 3 million to people no longer voting (net). The result was to hand Labour a 411 seat majority – despite Labour wining fewer votes than it had in 2019!

The Liberal vote was also slightly lower in 2024. To the nearest million the Liberals won as many votes in 2024 as they had in 2019; but now were rewarded with 72 seats rather than just 11. That is how the UK voting system works. It would be wrong to label the UK a ‘democracy’. There is only a very weak relationship between votes and seats. I’ll leave you to study the other differences between these Figure 1 and 2 that summarise the results; but note how fractured the age 23-28 vote has become by political choices. Also note that the very small parties have to be placed somewhere in the diagram. I have tried to place them where I placed them before, but I have aged those who cannot vote by five years (and an extra million of that group have arrived – net). Brexit did not reduce immigration.

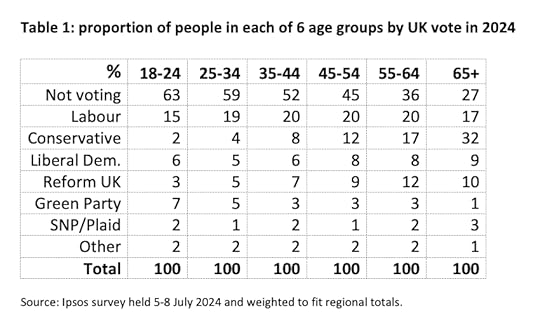

If you want to know how Figure 2 was constructed, the Table below is of the IPSOS estimates of voters turnout and voting by age. Note that this is based on a survey of ‘17,394 GB adults aged 18+, of whom 15,206 said they voted, interviewed on the online random probability Ipsos Knowledge Panel between 5-8 July 2024. The data was weighted using our normal methodology to be representative of the adult population profile of Great Britain, and then the proportions of voters for each party and non-voters were weighted to the actual results by region.’[1] IPPR research helped confirm the Ipsos findings.[2]

The figures in Table 1 were used alongside the overall party vote totals and population estimates to create the revised 2019 figure into its 2024 form. The projected population of the UK in mid-year 2024 was 69.025 million.[3] So three million more than what we thought the population was in 2019. Of those 28.809 million voted.[4] Just 59.8% of the 48 million people registered to vote. So, to the nearest million, 40 million people did not vote or were not registered to vote. Of that 40 million, 14 million were children, leaving 26 million adults who did not vote. Of those adults who did not vote, 20 million chose not, another 6 million were not registered to vote or were not permitted to register to vote. It is extremely hard to determine who does qualify to vote in the UK.[5]

Table 1: proportion of people in each of 6 age groups by UK vote in 2024

Source: Ipsos survey held 5-8 July 2024 and weighted to fit regional totals.

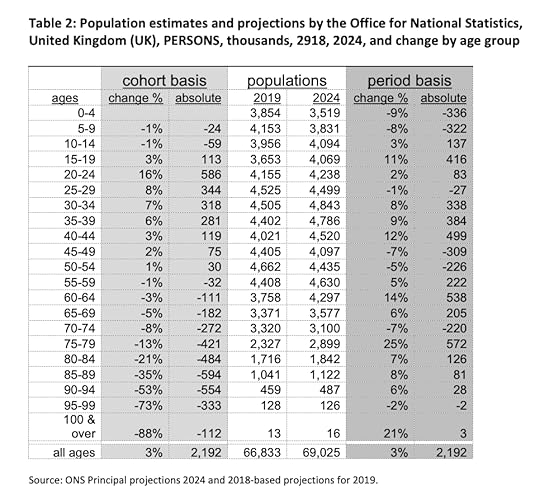

The final table here shows the population change in the UK by age for those interested in what has happened and where we are heading in terms of how many of us there are, and who will be voting at the next General Election.

The first column in Table 2 shows how each population group has changed in size compared to its numbers five year earlier. Thus, there are 1% fewer children aged 5-9 in the UK in 2024 than the numbers aged 0-4 in 2019. Deaths and net-migration are the only possible reasons. The age group that has grown the most are those aged 20-24 in 2024, by 16%; that has to be due to net in-migration. If you follow the first column of Figures in Table 2 down, you will note that the first fall is for ages 55-59. This is when deaths begin to take their toll. Follow the column down to its end and you will see that 88% of those aged 95-99 in 2019 did not make it to be 100+ in 2024.

The second column in Table 2 is the absolute number of people the percentages in the first column refer to, in thousands. The third and fourth columns are the ONS estimates and projections for the population of the UK by age in 2019 and 2024. Note that the total population estimate for 2019 is now thought to have been 66.8 million (nearer to 67). The fifth and sixth columns are the change when we just compare the age groups directly. There were 366,000 fewer children aged 0-4 in the UK in 2024 than in 2019, a 9% fall. This is greater than the 8% fall in the numbers age 5-9 in 2024. Our primary schools are going to struggle in future, then our secondary schools. We will be an even older population at the time of the next General Election, despite the continued immigration we benefit from. The final row in Table 2 shows that we grew in total population size by 3% in these five years. Without immigration we would already be a shrinking island. And, already, the 25-29 age group are fewer in number than those who were of those ages in 2019. Our future will depend as much on who comes and who goes, as on how we vote and if we ever manage to make voting fair.

Table 2: Population estimates and projections by the Office for National Statistics,

United Kingdom (UK), PERSONS, thousands, 2019, 2024, and change by age group

Source: ONS Principal projections 2024, and 2018-based projections for 2019.

References

[1] Gideon Skinner, Keiran Pedley, Cameron Garrett, Ben Roff Public Affairs (2024) How Britain voted in the 2024 election, London: Ipsos, https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/how-britain-voted-in-the-2024-election

[2] Parth Patel and Viktor Valgarðsson (2024) Half of us: Turnout patterns at the 2024 general election, London: Ippr, July, https://ippr-org.files.svdcdn.com/production/Downloads/Half_of_us_July24_2024-07-12-105904_eioz.pdf

[3] James Robards (2024) Principal projection – UK population in age groups, London: ONS, 30 January, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/datasets/tablea21principalprojectionukpopulationinagegroups

[4] Richard Cracknell and Carl Baker (2024) General election 2024 results , Research Briefing, London: House of Commons Library, 18 July, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-10009/CBP-10009.pdf

[5] The number was 7 million in England and Wales in April 2024, a million extra registered: Craig Westwood (2024) Millions of missing voters urged to register before deadline, London: The Electoral Commission, 9 April, https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/media-centre/millions-missing-voters-urged-register-deadline

For a PDF of this article and a link to the original source click here.

July 15, 2024

Reflections on the results of the General Election

Thanks to the far-far-right standing in almost every seat in the UK 2024 General Election, Labour is now in power as the party of government. Although many people think this was a forgone conclusion, just a few months earlier there had been great uncertainty over the outcome.

That uncertainty may have been a key part of the reason why the manifesto that the Labour Party presented to the British people was so lacklustre. The Labour leadership did not want to frighten voters away.

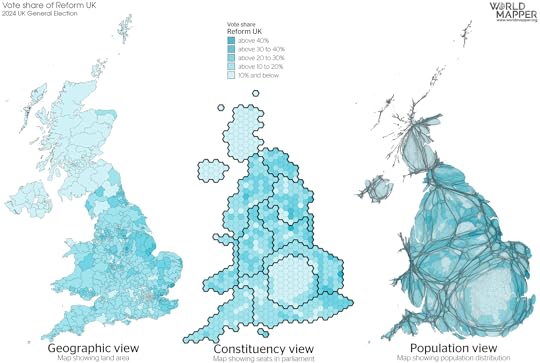

Figure 1 shows the greatest shock of the 2024 General Election, that outside Scotland, Northern Ireland and London, the far-far-right Reform UK party won a significant proportion of votes almost everywhere. This was partly because turnout was very low, but also because so many former Conservative voters defected rightwards. The geographical pattern of where the far-far-right fared well was telling – away from city centres, and especially along the coasts where older and sometimes poorer people are most concentrated (right hand cartogram in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Votes for Reform UK in the 2024 General Election (Source: https://worldmapper.org/uk-general-el...)

On 3 May 2024, Sky News forecast that there would be a hung parliament in Britain at the next General Election, with Labour winning only 294 seats given the popularity of the party at that time. Labour’s popularity actually fell during May and June 2024, from 44 per cent of voters supporting the party at the start of May, to 40 per cent by 3 July. On the day of the election, the Labour Party secured only 33.7 per cent of the vote, lower still and a lower absolute number than in 2019; but nevertheless won some 411 seats, thus securing a huge majority.

British politics has shifted greatly since Labour last won a majority of this size, in 1997. The Labour Party moved far to the political right under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The Conservatives were forced even further right, leaving the European People’s Party Group of Conservative political parties by 2014, to join a far-right grouping in the EU, and by 2022 becoming the most economically right-wing political grouping in the world, according to one analysis published by the Financial Times. Labour, in many ways having taken the political place of the Conservatives, experiences limited pressure from the political left; with only some Liberal Democrat policies, and a few more Green Party policies being to the left of Labour, at least in terms of manifesto commitments.

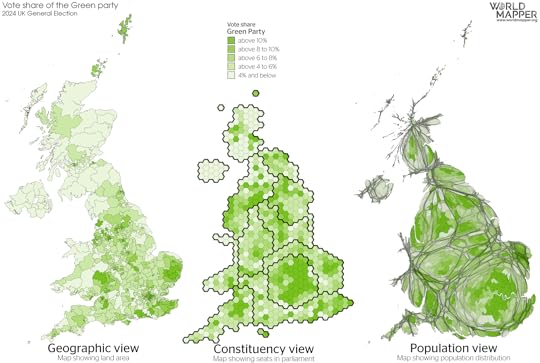

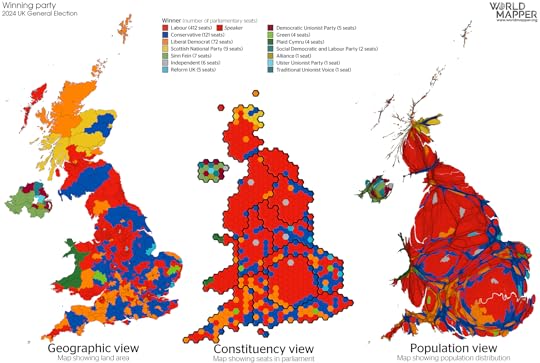

The shift in far-right Conservative vote towards the UK’s far-far-right party (Reform UK) has resulted in a further swing to the right within British politics. Despite this, the House of Commons now contains four Green MPs (the geography of the Green Party vote was the geographical antithesis of that of Reform UK; see Figure 2), four independent MPs elected for their position on the atrocities in Gaza, and the former leader of the Labour party, Jeremy Corbyn, who secured his seat for the 11th time. Reform UK only won five seats. There is no longer a single Conservative MP in Wales, the Scottish National Party lost many seats (but in a parliament in which they wield no power), and in Northern Ireland, Sinn Fein became the largest party with seven seats (which they will not sit in). This grouping may provide some voice, albeit a small one, of pressure on Labour’s left flank.

Figure 2: Votes for the Green Party in the 2024 General Election (Source: https://worldmapper.org/uk-general-el...)

Figure 3 shows how dominant Labour has become in terms of seats. Beneath the surface, however, Labour has lost half a million voters since 2019. It has increased its vote share by less than two percentage points, and only did that because more Conservative voters (who did not defect to Reform UK) chose to abstain compared to Labour voters. Labour lost several seats, including that of Jonathan Ashworth, a potential Minister, and now has a Health Secretary in an ultra-marginal constituency.

Figure 3: Which party won which seat in the 2024 General Election? (Source: https://worldmapper.org/uk-general-el...)

On the manifestos, ASAP UK analysis placed both the Greens and Liberal Democrats ahead of Labour in their policy ambitions to tackle poverty. The Intergenerational Foundation judged the Green Party manifesto to be the most friendly to the young. The High Pay Centre noted that ‘Labour commits to some degree of progressive taxation on private schools, energy giants and non-doms’, but that it was otherwise vague in its promises – other than saying that before any implementation of policy, ‘the Labour manifesto emphasises that [it] will consult fully with business and other stakeholders…’ And, given its majority, Labour’s is the only manifesto that now matters. There will be close attention given to what Labour now says and does in office, not least by the huge numbers of Labour MPs who are unlikely ever to become government ministers.

What is most unusual is that even in July 2024 we, the public, have very little idea what Labour will actually do. Most newly elected Labour MPs also do not know. At first, it appeared as if the new government were still in election mode and playing to the gallery, the one they imagined they were trying to impress: The Guardian writer Frances Ryan commented in shock a few days after the election on watching one post-election broadcast:

…it really is remarkable to hear a Labour health secretary describe calls for funding as “the begging bowl” – as opposed to, y’know, resources to pay for GP appointments, cancer treatment, and hip surgeries.

’

Perhaps most importantly of all, young people changed how they voted. Figure 4 shows that slightly fewer voted Labour in the youngest age group, than the next youngest. The Greens were most popular among the young, but so too, perhaps surprisingly, was Reform UK. Ever since 2017, a growing number of adults have been choosing not to vote at all for any of the options on offer.

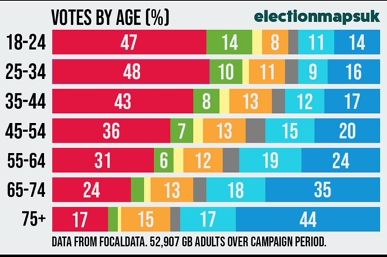

Figure 4: How people said they would vote by age in 2024 (Source: https://www.focaldata.com/blog/how-br...)

The promise of the 2024 General Election was not so much what was in the manifestos, or even what we learnt Labour might do in government in its first weeks. The promise was that the future would be different. And yet those with more stake in the future (the young age groups) were not enthusiastic in voting for this offer. Rather the voting pattern potentially shows one of growing dissent. In all age groups around four in ten of all voters did not choose to support either of the two main parties, and more than three out of every ten people who could have voted choose not to, at least not this time. Both proportions combined produce a historic high of majority dissent. Only 34 per cent of the electorate voted Labour or Conservative. Whether this reflects a lack of ambition within the manifestos to tackle the real challenges of inequality and poverty, a consequence of a very tactical, anti-Conservative election, or early signs that the contemporary political ideas are no longer resonating with the public, will only become apparent over the coming years.

Danny Dorling is Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of St Peter’s College. He is a patron of RoadPeace, Comprehensive Future and Heeley City Farm. He has published over 50 books, including the best-selling Peak Inequality: Britain’s Ticking Timebomb (2018) and Injustice: Why Social Inequality Still Persists (2014).

This article is part of a blog series published in partnership with Academics Stand Against Poverty UK, following their manifesto audit of the 2024 election. They have analysed the policies in the manifestos in relation to poverty to assess how confident they are that they will enable British society to flourish. Here, Danny Dorling offers his take on the results. Read all the articles in the Academics Stand Against Poverty blog series here…

Image credit: All maps are copyright Benjamin Hennig at worldmapper.org. Visit worldmapper.org for more Cartographic views of the 2024 election.

For where this post was originally published and a PDF of it click here.

Avoidable deaths have increased in the UK: the damning data political parties aren’t discussing

Lucinda Hiam, University of Oxford; Danny Dorling, University of Oxford, and Martin McKee, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

One question that British voters may have asked themselves during the 2024 election campaign is whether they are any better off now than they were in 2010 when the Conservative-led coalition came to power. A recent poll reveals that most Britons (73%) think they are not.

This is unsurprising given the evidence. Average incomes have grown more slowly than previously, and economic growth has lagged behind many comparable nations. Public services have worsened. Now, along with falling life expectancy and rising child deaths, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that another key measure of health has worsened: avoidable mortality.

The ONS data tracks trends at the level of local authorities in “preventable mortality”, which can be avoided through effective public health and “primary prevention” before a person becomes unwell, and in “treatable mortality”, avoidable through timely treatment once a person needs it.

When combined these two measures are termed “avoidable mortality” or “avoidable deaths”. All these measures consider only deaths in those aged under 75 and are age-standardised to enable fair comparisons, without being affected by the difference in age distributions, among local authorities and across time. While the data for England is reported by year, those for local authorities are averaged over three years to minimise the effect of short-term fluctuations, such as cold winters.

These latest statistics show sustained progress between 2000 and 2012, after which the rate of improvement slowed, before worsening from 2019 and during the pandemic. The most recent data show a slight recovery for England in 2022, but still worse than in 2019.

Avoidable, treatable and preventable deaths in England, 2001-2022

Avoidable, treatable and preventable mortality rates per 100,000 people.

Avoidable, treatable and preventable mortality rates per 100,000 people.Office for National Statistics

These findings are not, in themselves, surprising. Since the early 2010s, the UK has vied with the US for bottom place in the league table for gains in life expectancy.

ONS data published in January 2024 showed that life expectancy had returned to 2010-12 levels for females and slightly lower than over a decade ago for males. While inequalities have widened since 2010, it is shocking to see some parts of England have fared even worse than was suspected at a time when others were improving.

Those places that have done well show what was possible. Richmond upon Thames, a prosperous area in south-west London, saw a 21% reduction in avoidable deaths between 2009-11 and 2020-22, with a similar reduction in Oxford (20%).

In contrast, Castle Point, on the Essex coast, saw a 22% increase in avoidable deaths, and Walsall in the West Midlands a 19% increase.

Almost half of all local authorities experienced an increase in avoidable deaths, with increases in the rate. Over the same period (2009 to 2022), England overall experienced an increase in avoidable deaths of 1% and Wales of 1.5%.

The gap between local authorities with the highest and lowest avoidable death rates has widened, from 2.8 times in 2009-11 (with Hart in Hampshire at 162 per 100,000 people compared with Manchester at 460) to 3.4 times (with Hart again lowest, at 133 per 100,000 people and Blackpool now worst, at 455).

This widening gap reflected a combination of large improvements in places where avoidable death was already low (18% lower in Hart) and worsening where it was high (8% higher in Blackpool). The few exceptions where avoidable deaths fell from high levels did so modestly (7.9% lower in Manchester, 6.1% lower in Rhonda, 3.8% lower in Newcastle).

In general, areas with worse health in 2009-11 did less well over the next 11 years.

Ignored by all parties

These measures getting worse in an advanced industrialised country should be cause for significant alarm. Yet this information does not seem to have been discussed during the general election campaign – by any party.

The political parties’ manifestos contained shopping lists of numbers of NHS appointments that will be offered or scanners bought. Detailed analyses of the state of the nation’s health – and the reasons for its deterioration – were absent.

We might contrast, with concern, the media attention that greets the quarterly announcements of the UK’s economic growth figures with the very limited coverage of this data.

What the latest data reveals is particularly damning given the “levelling up” agenda set out by Boris Johnson in 2019, when he was campaigning for the leadership of the Conservative party. An agenda that, a recent review concluded, “has been glacial – and, on many metrics, the UK as a whole has gone into reverse”.

These are several similar reports highlighting poor progress and reversal of previously improving trends. For example, the terrible state of child health, with the Royal Society for Public Health noting how the new data show that avoidable child deaths have been rising since 2020. In England, it was 8.1 deaths per 100,000 in 2020, but 9.6 per 100,000 children in 2022.

During the election campaign of June 2024, none of the major parties set out a plan that would reverse these worrying trends. While reducing NHS waiting lists is important, it misses the bigger picture. Why are more people needing the NHS?

As well as the lack of adequate funding and workforce support for the NHS, the factors that make people unhealthy have worsened, with food poverty, education and housing particular concerns.

Stemming the flow without turning the tap off is a short-term solution for a long-term problem that requires a serious strategy – especially when the situation is getting worse.

Lucinda Hiam, DPhil Candidate, Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford; Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford, and Martin McKee, Professor of European Public Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here.

July 5, 2024

Afterword: ‘I spoke to a lady from Godalming…’

In March 2024, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, Jeremy Hunt, said:

‘I spoke to a lady from Godalming about eligibility for the government’s childcare offer which is not available if one parent is earning over £100k. That is an issue I would really like to sort out after the next election as I am aware that it is not [a] huge salary in our area if you have a mortgage to pay.’

Jeremy Hunt is not a socially aware person. That can be ascertained from the majority of the comments he has made in public since becoming a politician. He may be unusually unaware. But this particular comment was especially telling because it came at a time when Britain was experiencing its longest pay squeeze since the one that began in 1798. In fact, this comment was made on the day the British government released this country’s worst-ever statistics on poverty. They recorded the sharpest-ever rise in poverty, especially among children. Given how Hunt thinks, I doubt I have the teaching ability to explain to him why his observations were so very tone-deaf. At the same time, they reveal how many extremely well-off people in Britain think.

Lack of awareness among the elite is among our most urgent problems in Britain, and one which has only become more relevant since the hardback edition of this book was published last year. We live in a society where people in the top 1% of earners, like Hunt, mostly only ever meet people from the top 10%. When Hunt looks down, he sees someone on £100,000, treats them with pity and talks of how he can understand their plight. Those of us in the top 10% tend to look up more than we look down.

Jeremy Hunt was a student in my hometown when I was a schoolboy. I often came across his kind of people and so I got to see just how unaware they were when they were young; I also had pity for boys like him who had never been allowed to mix with other classes and who were afraid to walk the streets of Oxford because they might be set upon by the lower orders.