Danny Dorling's Blog, page 5

February 7, 2024

Full Marx for Trying: degrowth is possible – but not this way

In ‘Slow Down’, Kohei Saito insists that only ‘degrowth communism’ can save us from climate disaster – but his argument fails to convince.

Slow Down: How Degrowth Communism Can Save the Earth

Kohei Saito (translated by Brian Bergstrom), Weidenfeld and Nicolson, £22

At the end of Slow Down, its Japanese author Kohei Saito calls for the 99 per cent to be united, for the 1 per cent super-rich elites to be overthrown. Why? Because ‘the only hope humanity has left for surviving the climate crisis and bringing about a sustainable, just society is degrowth communism’.

The degrowth movement proposes a radical reappraisal of the global economy to reduce environmental degradation and reduce social inequality. It has grown greatly over the past decade, and Slow Down is just one of many books to address it – in its original 2020 Japanese edition, it reportedly sold half-a-million copies. What a pity that it is unconvincing.

For Saito, a young philosopher, the way to successfully bring about degrowth is simple: ‘… we must choose communism. We must overcome our reflex to rely on experts and the state and proceed down the path to self-governance and mutual aid,’ he writes.

Overthrowing democracy

Saito believes he can already see a ‘groundswell’ in the American city of Detroit, for instance, with the cultivation of ‘fruit and vegetables in the streets’. The revolution has begun with urban organic farming, we are told, and will overthrow democracy, which, we learn, is not long for this world. He writes: ‘In this, [Thomas] Piketty and I are in total agreement’. This may be news to the French economist Piketty.

Long before this passage, however, Saito exhibits delusions of grandeur. In spelling out how his vision of degrowth might become real, the book begins: ‘I intend to excavate and build upon a completely new, previously unexplored facet of [Karl] Marx’s thought that has been lying dormant for the past 150 years’.

Saito lambasts a number of thinkers for misunderstanding Marx. Even Engels is scolded for overediting him.

In doing so, Saito lambasts a number of thinkers and writers for misunderstanding Marx: the British geographer David Harvey; the co-founder of Novara Media Aaron Bastani; the late French philosopher and sociologist Bruno Latour; the University of California sociologist Kevin Anderson – they all get it in the neck. Even Friedrich Engels is scolded for over-editing Marx.

Each, it would seem, falls short of Saito himself who, in Slow Down, completes what Marx ‘… started in Capital by fully theorizing what degrowth communism might look like, creating a major new analysis adequate to this new age’.

How austerity generates growth

Useful work on degrowth is mentioned, such as the writing of Jason Hickel, author of Less is More. Hickel’s explanation is that austerity generates growth by causing scarcity, whereas degrowth would require the provision of an abundance which, in Hickel’s words, would ‘render growth unnecessary’.

Slow Down also has effective lines on climate change, which itself produces scarcity: ‘Climate change renders water, farmland and habitation scarce. As this scarcity rises, demand rises too, until it surpasses supply and provides a prime opportunity for capitalists to reap huge profits,’ writes Saito.

The book’s framing of the ‘99 per cent’ and the ‘1 per cent’ is problematic.

As to how we get what we need, the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers of 1844 is mentioned, but not how co-operative movements could scale up sufficiently. Spain’s Mondragon Corporation is the world leader in the co-operative movement, but is omitted – highlighting its success might imply that there is an existing alternative to Saito’s global vision.

Other problems blight Saito’s recipe for a new world order, not least his framing of the ‘99 per cent’ and the ‘1 per cent’. First, the 99 per cent that he describes are not as one. Instead, they range from the poorest souls on Earth to those who are within a whisker of being in the top 1 per cent of the income or wealth distribution.

Second, hardly any of the 1 per cent are the super-rich elite. On a global scale they are likely to include many people that the western readers of this article may know. Nor is it true that, should global warming melt more of the Antarctic ice sheets, the number of people who ‘… have to evacuate their current home [will be] in the hundreds of millions’. Climate change will probably allow for regrettable but managed relocation, not mass sudden evacuation.

Falsifying the reality of communism

Saito’s writing also suffers from its reliance on the thinking of the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. He unquestioningly adopts Žižek’s definition that ‘communism is nothing less than the conscious attempt to reconstruct the commons – knowledge, nature, human rights, society – dismantled by capitalism’.

By doing so, Saito may suffer from what the late sociologist Zygmunt Bauman said was Žižek’s falsifying of the reality of communism. ‘I am amazed (and angered!) by the widespread tendency to consider Žižek a left-wing person,’ Bauman wrote in his final publication.

As an alternative to the erratic Slow Down, try Hickel’s Less is More or indeed Bauman’s final book My Life in Fragments if you want an understanding of where degrowth might be heading and how hard it is to get there.

For a PDF of this review and where it was originally published click here.

Intro to the book

January 16, 2024

Influenza: cause or excuse? An analysis of flu’s influence on worsening mortality trends in England and Wales, 2010–19

Lu Hiam, Martin McKee, and Danny Dorling, writing in the British Medical Bulletin, 15 January 2024, All social groups in England and Wales experienced a long period of increasing life expectancy until the second decade of the 21st century, a trend mirrored within Scotland and Northern Ireland, albeit not as favourably in recent decades. Life expectancy, the most widely used summary measure of a population’s mortality experience, shocked observers when its long upward trend slowed markedly shortly after 2010. Recent gains even reversed in some groups, such as those living in poorer areas. This slowdown was also witnessed throughout the rest of the UK. Although we focus on England and Wales, some other European countries also saw slowing life expectancy improvements. However, the situation in the UK was more severe and prolonged than elsewhere in Europe, similar to what was observed in the United States. For comparison, between 2010 and 2021, life expectancy at birth increased by 0.5 and 0.3 years for women and men respectively. In contrast, the corresponding figures in Sweden were 1.4 and 1.6 years; in France, they were 0.8 and 1.4 years; and in Germany, one of the poorest performers in continental Europe, they were 0.6 and 0.7 years.

Life expectancy tends to fluctuate yearly, especially in countries with small populations where the impact of relatively few deaths can be significant. In contrast, a non-trivial change in a large country like the UK usually has an identifiable cause. For instance, life expectancy in England and Wales fell by 0.45 years between 1950 and 1951 and 0.37 years between 1967 and 1968. These decreases coincided with what was considered an influenza epidemic and a confirmed influenza pandemic, respectively.9 While there is ongoing debate about the exact causes of the high death toll in 1950/51, which was much higher than in other countries, the impact of the 1968 influenza pandemic is uncontested. The underlying upward trend in life expectancy has been attributed to reduced risk factors, especially for smoking-related cancers and cardiovascular diseases. This decrease in risk reflects improved living conditions and, particularly since the 1960s, advancements in the effectiveness and coverage of healthcare. While there is some debate about the detailed explanation of these improvements, health overall in the UK was improving. There was a widespread, albeit implicit, assumption that this would continue. However, something changed in 2012. Unlike the previous years mentioned, this was not a one-off decline but a shift in the longer-term trend.

…

Figure 5: Age-standardised mortality rate, deaths per 100,000 population, for influenza-like disease, males and females in England and Wales 2001 to 2021. Note: deaths due to the spread of Sar-CoV2 are not included.

…

Influenza did not cause the stalling and worsening mortality trends in England and Wales from 2012 onwards, which continue to the present day. Given the evidence of the greatest impact of austerity on those living in deprived areas, a next step will be to examine these trends by deprivation decile. Future research may also explore why so many people in such high positions of authority were so quick to attribute the change in overall mortality trends to influenza and were slow to correct this later and why, to this day, the negative impacts of austerity on health, not least on pandemic preparedness, are not accepted by its architects, nor by so many of those who have followed them; and why so many people in England and Wales have stood by and watched this failure of government and public health unfold.

For the full British Medical Bulletin paper and supplementary material click here.

January 3, 2024

Is Inequality Inevitable? The ‘Northern European Model’ Suggests Not

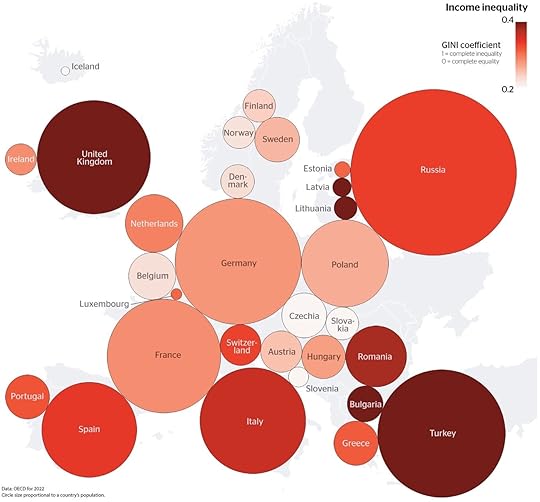

The Nordic model of capitalism has garnered substantial attention for its approach to economic and social organisation. While the five Nordic nations – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – may initially appear similar, a more in-depth examination reveals great differences both between and within them on a host of indices. The Nordic states remain most similar in reporting much lower than usual rates of income inequality. However, just how low are these rates and how distinctive are the five countries today?

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) provides valuable data on income inequality, shedding light on the economic structures of various nations. Their data shows the Nordic countries clustered together due above all else to low levels of income inequality, resulting in more equitable economic conditions for their citizens compared to many other affluent nations such as the UK, USA, Russia and Israel, which have almost identical levels of high income inequality. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the collection of consistent data is predominantly undertaken by affluent countries.

Consequently, when we discuss different models of capitalism, our focus primarily revolves around the affluent world. Here we aim to provide a mainly European perspective. One key takeaway from the available data is the dynamic nature of capitalism. A look at statistics on inequality over a short timeframe may suggest that nothing substantial is changing. However, when we broaden our perspective and examine data spanning from over a longer period, we can observe a different narrative. Over this 14-year period, the Nordic countries appear to have consistently maintained economic equity.

Our timeframe represents just a fifth of normal human life expectancy, a fraction of human history or even of more recent economic history. The Nordic countries cover a small part of the world’s population. Indeed, just how unusual are the Nordics? If we look across Europe we can see another, less cohesive, cluster of nations all exhibiting lower income inequality than the most equitable Nordic country, including Czechia, Slovakia and Slovenia. This prompts the question of why we don’t consider these countries as a similar model or template for a better world.

Differences in shared history and geographical proximity can be suggested, but the latter cannot be the sole explanation, as these countries are just as contiguous as the Nordic nations. In contemporary discussions concerning the Nordic model of capitalism, it is crucial to acknowledge the increasing similarities between these Northern European countries and many other European nations, including larger states such as France and Germany. In terms of income inequality, they are increasingly resembling the Nordic countries.

So, is the term ‘Nordic model’ still suitable? Perhaps we should consider rebranding it as the ‘Northern European model’? The Nordic five are increasingly dissimilar from each other while also gradually becoming part of a broader group of 15 countries, encompassing those slightly more and slightly less equitable. In terms of population, this represents a more substantial grouping, or ‘Nordic+’.

Within the Nordic+ cluster, there are countries that share borders with remarkably unequal states. Immediately to the west of Nordic+ is the UK and to the east is Russia, both characterised by high levels of inequality and challenges for the less fortunate. Bulgaria, the most unequal country in Europe, and Turkey, which is even more unequal and partially situated in Europe, bordering the southeast. These countries also boast outsized capital cities, further illustrating their historical significance as former centres of empires.

Other nearby countries without recent imperial legacies, such as Estonia, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland, are closer to joining Nordic+ having only slightly higher levels of inequality. Inclusion of these nations would expand the group to a club of 20 countries, making it almost all of Europe.

This discussion also highlights the ever-evolving nature of capitalism. Capitalism is not a static ‘system’ but rather an ongoing transformation, often challenging the human imagination because of our lifespan. The change is over a 400-year period, not within one lifetime.

While some argue that capitalism is a singular concept, it is becoming increasingly apparent that we live in a world characterised by plural capitalisms. These systems share some ideological aspects but exhibit substantial local variations. We are currently in a phase where we are more attuned to these distinctions, particularly between the United States and Europe, where the disparities have grown more pronounced. Growing numbers of people do not accept the story that inequality is inevitable, and in most of Europe they also do not have to live with gross inequality.

income inequality levels in European countries, latest data, OECD, November 2023.

While nations exhibit distinct social and economic characteristics, generalisations are possible. Generally, countries that are closer to the UK and the USA in their economic model tend to be more individualistic, while those farther away tend to be more collective and generous. What is equally intriguing is the increasing resemblance of many countries worldwide to the Nordic model, or in some cases, even surpassing the Nordic countries in various aspects.

The Nordic model is often perceived as institutionally distinct, with higher levels of trust in institutions. However, this trust might have originated from the Nordic countries’ historical equitable and content societies. It is not necessarily that the ‘Nordic way’ is losing its distinctiveness; rather, more nations are embracing Nordic-like characteristics and building new ideas around them.

There are remarkable achievements of the Nordic model, characterised by high innovation and remarkably low rates of exploitation and immiseration. The Nordic model is portrayed as a brief chapter in the ongoing narrative of capitalism, which, in itself, represents a transient phase in the history of humanity.

The Nordic model of capitalism is a captivating case study within the larger framework of capitalism’s evolution. It underscores the intricate interplay of economic and social dynamics, the changing landscape of capitalism, and the influence of global factors on economic systems. Understanding these nuances is vital for gaining a comprehensive view of the complex world we inhabit.

Biographies

Danny Dorling is Professor of Human Geography at the University of Oxford. Benjamin Hennig is Professor of Geography at the University of Iceland and Honorary Research Associate at the University of Oxford.

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here.

December 26, 2023

For All Those – Public Sector Sensitivities

In April 2023 Michele Lancione, a Professor of Economic and Political Geography at the Polytechnic University of Turin, was interviewed about his work. The interview appeared on the faculty of law blog at the University of Oxford (1). Michele had risen in prominence nationally, and then internationally, because he had complained that his university was allowing Frontex, the EU border agency, to subcontract work making maps concerning the activities of the agency. The agency had been accused of carrying out many serious human rights violations at the EU’s external borders.

When Professor Lancione asked the university he worked for to end its contract with the agency, he was informed (by those with the most power in his university) that the project was simply producing ‘harmless data’. He explained: ‘the collaboration was presented as proof of the department’s “research excellence”. But what my colleagues are doing is not research. It is essentially service provision. Frontex asked for maps, my department agreed to deliver maps using data that is either open source or provided by Frontex. The problem is that maps are never neutral. Indeed data, any kind of data, is never harmless. Frontex’s maps commonly show big red arrows that point from Africa to Europe. These supposedly indicate migration flows, but they produce a sense that we are under siege by threatening migrants landing on Italian shores.’

One such map is that shown here:

Source: Frontex off Campus! An Interview with Professor Michele Lancione

Professor Lancione explained to the interviewer that he was fortunate. As a full professor he could take this stance knowing that his job was fairly safe and that he was no longer seeking further promotion. However, he said, that because he had complained: ‘Some colleagues are not talking to me anymore. The head of department is not responding to me. Very high-ranking members of my university have expressed the need – in private university meetings – to “get rid of that anarchist”. I am fine in being labelled as such. But they won’t get rid of me, or of the others fighting for a more just university, very easily.’ What some of his colleagues may have most disliked was that he asked the question: ‘Can I carry [out] ‘ethical’ research work, if my Institution is doing affairs with a third party who is involved in the systematic violation of human rights?’

You might say that all this is about ‘a quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing.’ (2) But it wasn’t and it still isn’t. What do these events, taking place fairly far away in Italy, concerning a border that is no longer ours, have to do with the public sector in the UK? The answer is that they involved what you can and cannot speak out about.

On the 13th of October Susan Brown, the then majority Leader of Oxford City Council, the public sector local authority in which I both work and live, in which I was born and where I went to school (a school where the second most common language even back then was Urdu), made a statement to the press upon the resignation of two local councillors in reaction to what the Labour Leader Keir Starmer had said about the war on Gaza – on what be believed was permissible under international law – on what Starmer thought was right.

No explicit mention was made of Muslims in Oxford.

They were just a part of ‘all those’.

Words matter.

Because attitudes matter.

Words reveal your attitudes. Even if you try later, as Keir Starmer did, to say that what you said was not what you had meant.

One of the two councillors who were the first to resign replied in the pages of the Guardian newspaper. Shaista Aziz explained: ‘If Starmer can be so reckless with his words and lacking in principle now, what will happen if he becomes prime minister?’ (4)

Soon another ten local councillors resigned from the Oxford Labour party. Some resigned alone, others in groups, not all at the same time, but all having thought much more about what it was that they were being asked to be a part of by not resigning; or as Professor Lancione might have put it: being asked to think how they could be ethical if the label they held was now not.

More Labour councillors were rumoured to be on the edge of leaving. The Labour Party no longer had a majority in the City of Oxford. The minds of councillors were changing. Not just of the Labour councillors in Oxford, but soon the minds of all the city councillors from every political party. By November 28th, Oxford City Councillors unanimously voted for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. As the Oxford Mail newspaper reported ‘all members voted for it including [the now minority] city council leader Susan Brown.’ (5)

In his interview that had taken place earlier in 2023, Professor Lancione ended with his plans for the future when faced with a university that was trying to ignore all the complaints about what they were complicit in and making him complicit too. He said: ‘Personally, I am shifting this campaign into my own teaching. I hope to engage with students about the role of universities in militarisation. I also have a book coming out in July that is specifically addressed to students. Hopefully it will be seen as a guide on how to deconstruct universities’ problematic relationships. I hope it inspires them to start organising once more, with renewed energy and awareness.’

People change their minds, young people form their first opinions of international events at times like this, and of their elders, some say ‘it is too complex – you would not understand, others reply – ‘try’. I’ll end this short piece with a part of a poem, by Suheir Hammad. (6)

What I will

I will not

dance to your war

drum. I will

not lend my soul nor

my bones to your war

drum. I will

not dance to your

beating. I know that beat.

It is lifeless. I know

intimately that skin

you are hitting. It

was alive once

hunted stolen

stretched. I will

not dance to your drummed

up war. I will not pop

spin break for you. I

will not hate for you or

even hate you. I will

not kill for you. Especially

I will not die

for you. I will not mourn

the dead with murder nor

suicide. I will not side

with you nor dance to bombs

because everyone else is

dancing. Everyone can be

wrong. Life is a right not

collateral or casual.

… [continues]

REFERENCES

(1) Maurice Stierl (2023) Frontex off Campus! An Interview with Professor Michele Lancione. Available at: https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2023/04/frontex-campus-interview-professor-michele-lancione. Accessed on: 28/11/2023

(2) Neville Chamberlain (1938) Chamberlain addresses the nation on peace negotiations, BBC, 27 September, https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/chamberlain-addresses-the-nation-on-his-negotiations-for-peace/zjrjgwx

(3) Susan Brown (2013) Statement from Oxford City Council Labour Leader on Resignations of Cllrs Aziz and Latif, October 13th, https://www.oxfordlabour.org.uk/statement-from-oxford-city-council-labour-leader-on-resignations-of-cllrs-aziz-and-latif/

(4) Shaista Aziz (2023) Labour has betrayed British Muslims over Gaza – that’s why I resigned from the party, the Guardian, 24 October, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/oct/24/labour-gaza-british-muslims-starmer-betray

(5) Noor Qureshi (2023) Oxford City Council votes for Gaza ceasefire in full meeting, The Oxford Mail, 28 November, https://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/news/23953394.oxford-city-council-votes-gaza-ceasefire-full-meeting/

(6) Suheir Hammad (2017) What I will, Poems, 22 November https://www.arabworldbooks.com/en/e-zine/poems-by-suheir-hammad and https://blog.ted.com/text-of-what-i-will-by-suheir-hammad/

For where this article first appeared and a PDF copy click here.

November 28, 2023

Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World – Review

In Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World, Gordon Brown, Mohamed El-Erian and Michael Spence put forward a strategy on growth, economic management and governance to prevent crises and shape a better society. Danny Dorling contends that the book’s suggested policy solutions for economic and social problems, stemming from a hypercapitalist ethos, would entrench rather than reduce inequalities.

Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World (cover)

Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World by Gordon Brown, Mohamed El-Erian and Michael Spence, with Reid Lidow. Simon & Schuster. 2023.

Permacrisis is a remarkable book, but not for the reasons its authors might have hoped. It explains brilliantly why so much of our politics and economics is in such a terrible mess. The book argues that economic growth is progress, that we need this type of growth above all else to prosper, and that with just a minimal extra layer of regulation, such growth can spread the good life to the masses. Two quotations from Permacrisis, I believe, sum up both the core mantra of the three authors and what they think of as good growth and the good life. First, the mantra:

”You see, growth is progress. Growth is what has given the world the tablet you’re reading this book on, the medicines by your bedside, the economic breakthroughs that have lifted billions out of poverty. The problem is how growth has been achieved […] the old unsustainable “profits over people” methods of the past have outstayed their welcome and today are not just failing individuals and our environment but national economies” (14).

[The authors] assume that the development of a tablet computer is due to economics rather than developments in universities and other state-funded bodies which created the micro-components that that enable a computer to be transmuted into tablet form.

The authors make a series of assumptions that help to explain why people like them think like they do. For example, in the above quotation, they assume that the development of a tablet computer is due to economics rather than developments in universities and other state-funded bodies which created the micro-components that that enable a computer to be transmuted into tablet form. Computers, and electricity before that, were not products of “the market” but technological inventions that have been marketised.

Perhaps they choose to assume their reader uses a tablet rather than a print copy because it is impossible to argue that the invention of the book, or typesetting or the printing press, was due to economic growth. This is because it happened long before the concept of economic growth existed, when a group of monks in Korea invented movable type in 1377. Instead, it was economic growth that got us to a state, in the Netherlands in the 1990s, where we were publishing more books than people could read by those purchasing them, peaking at over a thousand new titles a year per million potential readers (see image below). At this point, middle-class Dutch people stopped buying books just to display in their homes, and the publication of new titles plummeted (see Figure 12 below from the book Slowdown).

Figure 12 from the book “Slowdown”

As the above example illustrates, economic growth can produce waste more than uplift and “progress” for the vast majority of people. Similarly, industrialisation reduced life expectancy not just in the mill towns of England, but across India. As I write global life expectancy hovers just above 70. In the US between 2020 and 2021, it dropped from 77 to 76.1, its lowest level since 1996. Most people in the world have far too little, a few have far too much. Social, medical, educational, housing, and cultural progress have all been made when the greediest aspects of market behaviour have been held in check, as the UK’s history of service provision demonstrates. Technological progress has depended on collaboration over profits. Those working in the US and UK produce very few innovations per head, as compared to people in the Nordic countries or Japan. But, the authors of this book appear utterly unaware of such arguments.

As with the tablet, the authors suggest that we have medicines because of economic growth rather than research and innovation; tellingly, the index to the book includes entries for “McKinsey” and “Pacific Investment Management Company (PIMCO)”, but none for “medicine” or “pharmaceuticals”.

As with the tablet, the authors suggest that we have medicines because of economic growth rather than research and innovation; tellingly, the index to the book includes entries for “McKinsey” and “Pacific Investment Management Company (PIMCO)”, but none for “medicine” or “pharmaceuticals”. This choice reveals what the book is actually about: the world of consultancy, international travel, and enormous amounts of money. McKinsey & Company is a global management consulting firm founded in 1926 by a University of Chicago professor (of accounting) that advises people with a lot of money how to acquire more. PIMCO, is an American investment firm that manages about two and a half trillion dollars of capital – to make more for people already rich. There is a pattern here.

Brown, El-Erian, and Spence suggest that, with a little more management by people like them, a little more of their kind of consulting, a little more of what they view as careful investment and better directing the trillions held by the world’s super rich, that we can somehow end the unsustainable “profits over people” behaviour of global economics.

The authors of this book believe that it was economic growth that “lifted billions out of poverty”. This view, along with the other core beliefs in Permacrisis, goes entirely unquestioned. Rather, Brown, El-Erian, and Spence suggest that, with a little more management by people like them, a little more of their kind of consulting, a little more of what they view as careful investment and better directing the trillions held by the world’s super rich, that we can somehow end the unsustainable “profits over people” behaviour of global economics. For them, the crisis is that they are not being listened to enough.

This brings us to how the book figures growth, and a second key quotation. In a long section celebrating the $1.50 Costco hot dog that entices shoppers through its doors, the authors explain their idea of economic growth and why they rate it so highly. Costco is a huge US chain of warehouses that started in 1976 as Price Club. It now has 125 million members, a number rising by around 6 million a year, and accelerating.

“The hotdog with the tantalising $1.50 price gets people in the door. And when they’re in the door, that’s when they see the knife set, back-yard patio set or the vacuum they can’t live without. And this business model has been a winner helping Costco reach a value in excess of $200 billion. Costco’s hotdog is a powerful and tasty reminder that growth isn’t always achieved by innovations developed in a Silicon Valley garage. Sometimes it’s as simple as keeping the price of a hotdog and soda steady – a decision that advances social goals by feeding those seeking an affordable snack, all while helping to power the growth of one of America’s largest companies. Costco’s chief financial officer was asked in late 2022 how long the $1.50 price would last. His response? Forever.” (30).

It is almost shocking to see such blatant endorsement of a particularly destructive form of economic growth, unplanned (at least as far as the consumer is concerned) instant gratification consumption, and such a warped view of social goals (to provide cheap hot dogs to the gullible).

Of the book’s authors – who were brought together by Jonny Geller of the global literary and talent agency, Curtis Brown (298) – one is Chief Advisor to “Allianz, the corporate parent of PIMCO, where he was CEO and co-CIO” (2) and husband of an executive director of Eco Oro Minerals Corp. Another was once UK Prime Minister and worked closely with Ed Balls, whose brother Andrew Balls has been for many decades a Chief Investment Officer of PIMCO (the other co-CIO). The third, who now lives in Milan, joined Oak Hill Capital in 1999 and was awarded a Nobel Prize in economics in 2001. They are what some economists view as masters of the universe: They believe their combined knowledge spans the breadth of global economic expertise: “While our personal and professional experience had natural touch points, like any good corporate merger the overlap and redundancy were minimal” (3). In fact, they are the crisis – and luckily, their beliefs are very far from permanent, sustainable or convincing, no matter how much they signal a sustainable ethos by adding the prefix ”‘eco-” before the ideas they put forward. In this book, they have encapsulated exactly what is wrong with the late twentieth-century hyper-capitalist worldview they champion that seeks to enrich the few and impoverish the rest of society.

Danny Dorling is a professor in the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford, and a Fellow of St Peter’s College. He is a patron of RoadPeace, Comprehensive Future, and Heeley City Farm. In his spare time, he makes sandcastles. Posted In: Book Reviews | Contributions from LSE Alumni | History | Sociology/Anthropology

For where this review was originally published and a pdf of it click here.

November 21, 2023

A deathly silence: why has the number of people found decomposed in England and Wales been rising?

An exploratory study has raised concerns about the increasing number of people in England and Wales whose bodies are discovered so late that they have decomposed.

The study, published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, has highlighted potential links between growing isolation and such deaths, even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study was authored by a team led by Dr Lucinda Hiam of the University of Oxford and including histopathology registrar Dr Theodore Estrin-Serlui of Imperial College NHS Healthcare Trust.

The researchers analysed data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), identifying deaths where bodies were found in a state of decomposition. They used a novel proxy: deaths coded as R98 (“unattended death”) and R99 (“other ill-defined and unknown causes of mortality”) according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and previous versions, referred to as “undefined deaths”.

The study revealed a steady increase in “undefined deaths”, i.e., deaths of people found decomposed, between 1979 and 2020 for both sexes. The proportion of total male deaths exceeded female deaths, with these deaths increasing significantly among males during the 1990 and 2000s, when overall mortality was rapidly improving. This acceleration in deaths where people are found decomposed, particularly for men, is a concerning trend, the authors said.

Supplementary Material Figure B: Number of undefined deaths by age group and sex, 1958-2021, England and Wales. Females on left panel, males on right panel

“Many people would be shocked that someone can lie dead at home for days, weeks or even longer, without anyone raising an alarm among the community they live in,” said Dr Estrin-Serlui. “The increase in people found dead and decomposed suggests wider societal breakdowns of both formal and informal social support networks even before the pandemic. They are concerning and warrant urgent further investigation.”

The authors of the study are calling on national and international authorities to consider measures that would make it possible to identify deaths where people are found decomposed more easily in routine data.

Notes to editors: A deathly silence: why has the number of people found decomposed in England and Wales been rising? (DOI: 10.1177/01410768231209001) by Lucinda Hiam, Theodore Estrin-Serlui, Danny Dorling, Martin McKee and Jon Minton was published by the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine at 00:05 hrs (UK time) on Wednesday 22 November 2023.

For the full article and where it was originally published click here.

November 14, 2023

The UK government has failed to act on extreme poverty

The UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty has said that the UK is “in violation of international law” over poverty levels. This is shocking, but not surprising, argue Lucinda Hiam and Danny Dorling.

In 2018, Philip Alston, the UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty, described in detail the “gross misery” that the UK government had “inflicted” on the population through the “punitive, mean spirited, and often callous” policies of austerity.1 Alston said the levels of child poverty in the UK were “not just a disgrace, but a social calamity and an economic disaster.”

In November 2023, Olivier De Schutter, Alston’s successor as UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty, visited the UK. So, what’s changed? The “disgrace” of child poverty has not improved. In fact, it has worsened. A reported one million children in the UK experienced destitution in 2022. This means their families “could not afford to adequately feed, clothe, or clean them, or keep them warm.” The destitution was the result of cuts to benefits and an utterly inadequate government response to the cost of living crisis. This was anticipated and, arguably, could have been prevented. The alarm has been raised repeatedly and consistently over the harms of austerity in the past decade. For example, in 2014, an open letter to then prime minister David Cameron raised substantial health concerns about the impacts of food poverty and poor nutrition. Yet, food insecurity and food bank use have increased, closely linked to government implemented austerity.

Between 2022 and 2023, the number of children living in food poverty almost doubled, and in September 2022 one quarter of households with children had experienced food insecurity in the past month, rising to 42% of households where there were three or more children. Five year old boys in Britain are now shorter than those of the same age in Europe. The trend in heights had been steadily increasing from 1990, but this ended and reversed after 2010, so much so that by 2020 they were shorter than they were in 1990. And now, in 2023, startling data from the National Child Mortality Database show rising infant and child mortality rates across England, with geographical disparities widening between regions and levels of deprivation, as well as increasing inequalities between ethnic group. Despite all this, the government is reportedly considering freezing working-age benefits—a move that the Resolution Foundation estimates would put an additional 400 000 children into absolute poverty.

The enduring disgrace of child poverty in the UK is perhaps the worst of so much that is going wrong in a state where things have fallen apart. And of course, solutions do exist in a state as rich as the UK. According to Action for Children, the temporary increase in Universal Credit during the covid-19 pandemic (by £20/week) lifted 400 000 children out of poverty. The withdrawal of this increase, combined with the cost of living crisis, meant the number of children living in poverty returned to pre-pandemic levels of 4.2 million. In contrast, in Scotland, where they have maintained child benefit payments for the third child in a family (and others), child poverty is now lower than in eight of the nine regions of England, with fewer children in poverty in Scotland (24%) than in England as a whole (31%). Furthermore, Scotland has recently raised its additional Scottish child payment to £25 a week for any child aged under 16 in any household in receipt of benefits, which will lower child poverty there further. Wales’s children’s commissioner is advocating to introduce a similar payment in Wales. Child poverty can be reduced if the will is there.

Given the levels of child poverty and hunger in the UK—often said to be the fifth richest country in the world—it is not surprising that De Schutter has found that “things have gotten worse”, saying “The warning signals that Philip Alston gave five years ago were not acted upon”. De Schutter has said that the current universal credit that a single person over 25 receives (£85/week) is “too low to protect people from poverty” and that this, in turn, is a violation of human rights law. This is consistent with evidence demonstrating that universal credit does not provide enough money to live healthily. But what impact will De Schutter’s shocking statement have?

This is not the first report of its kind, nor will it be the last. It is hard to find the words to express the impact of 13 years of a government that does not accept, let alone act upon, such damning evidence from a respected international body. But as Michael Marmot explained in February 2023, the UK government is now: “Creating the conditions for ill health by denying minimum income for a healthy life. It is government policy that people who need benefits, Universal Credit, will have only 70% of the money they need to live healthily.”

A view across London, city of poverty, in 2023

In response to the UN rapporteur, an unnamed government spokesperson made a series of claims about 1.7 million fewer people living in absolute poverty as compared to 12 years earlier and households being better-off if they worked.16 The selective use of numbers or indicators to refute the robust findings of multiple experts is not a useful response from a democratic government. De Schutter said: “There’s a huge gap, which is increasingly troubling, between the kinds of indicators the government chooses to assess its progress on one hand, and the lived experience of people living in poverty.”

Before the past 13 years of austerity, statements about the levels of poverty in the UK from international bodies like the United Nations would be shocking. But, in the UK today, these headlines, along with the evidence being given in the covid inquiry, are met by many with apathy. On 7 November 2023, the King’s Speech mentioned children in two areas: one in a welcome move to restrict sales of tobacco and electronic cigarettes to children, and the other relating to a criminal justice bill. There was no mention of the one million children living in destitution, the four million children facing food insecurity, the 4.2 million children living in poverty, or the cuts in public services, wages, and benefits that have put them there. We must demand more from our government and expect that by the time the next UN special rapporteur visits the UK, we will have seen significant positive change.

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here.

October 27, 2023

Destitution, unlike success in football, is coming home

“The government is not helpless to act; it is choosing not to”

Paul Kissack, Chief Executive of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 24 October 2023

In the summer of 2023 the England’s football team came second, to Spain in the women’s football world cup; the build-up to which meant that another story was barely noticed, and the aftermath of which – when it took a long time for the Spanish FA president to resign meant that other news did not make the news as much as it might. On Sunday 16 July 2023 it was reported that on the two child benefit cap, the one that ensures that child benefit is only paid for the first two children in a family in the UK (it does not apply in Scotland and Northern Ireland):

‘Labour had come under fresh pressure to promise to scrap the cap after it emerged that one in four children in some of England and Wales’s poorest parliamentary constituencies live in families left at least £3,000 a year out of pocket as a result. Starmer’s decision to rule out lifting the cap caused alarm among anti-poverty campaigners and despair in the Labour ranks. It would cost about £1.3bn but the shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, is said to have concluded it would be unaffordable due to the state of the economy. The stance is seen by some in the party as an indicator of the lack of strength of its determination to tackle child poverty. However, one party insider suggested Starmer could revisit the policy if the public finances improved. In February 2020, Starmer said he wanted to scrap it in order to help “tackle the vast social injustice in our country”. But this month he hinted that Labour would stick to the Tory policy. His latest remarks to the BBC’s Sunday with Kuenssberg show appeared to confirm that position.’ [1]

By September the BBC’s political editor, Laura Kuenssberg had broadcast three of her episodes of ‘State of Chaos’ concerning the collapse in ability, in authority and the sheer extreme asininity of the Conservative party in the period from Theresa May’s melancholy, through all of Boris Johnson’s jollity, up to Liz Truss’ temerity, transgression and termination. The Conservative party, a party she knew extremely well, was being written off in public. When Johnson resigned, all he could list as his tangible achievements were: ‘I have helped to deliver, among other things, a vast new railway in the Elizabeth Line and full funding for a wonderful new state of the art hospital for Hillingdon, where enabling works have already begun.’[2] In other words, the hospital had not actually been built and the Elizabeth Line had very little to do with him.

Labour was now seen by folk like Kuenssberg to be safe – willing to say, and possibly even believe, that there was no alternate to the very poorest families with children in England and Wales having to get by with three thousand pounds a year less than they would if they lived in Scotland or Northern Ireland. Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves had decided to change Labour Party policy that summer. But said that Labour ‘might’ revisit the policy should the country suddenly becoming richer again; or revisit it at some distant point in the future should we more slowly become better-off; or never revisit it at all if the sunlight uplands appeared too far away to grasp at any point in the foreseeable future.

So, what had happened to take the UK to the point where its Labour party said that reducing child poverty was now, for the foreseeable time, unaffordable?

Part of the answer was that it was the realization that we had literally run out of money. Even those who used to claim that the country could always print more as it was sovereign, were beginning to realize that, if we did that, it would only result in even less international confidence in what Britain stood for, as well as a fall in the pound, rising prices for all those foodstuffs that are imported (and every other vital good we receive from abroad), and an increase in the interest rates that we have to pay to international bankers to borrow money that had already become the highest of any large country in Europe.

We were broken.

Just two days earlier, on 14 July 2023 the Office for Budget Responsibility had reported that ‘As things stand, Britain’s long-term debt is on an “unsustainable path” that is expected to rise from about 100 per cent of GDP this year to 310 per cent by the mid-2070s. Yet this is only a baseline projection by the watchdog. It warns that public debt could reach…’[3] You really do not want to read on as their text becomes a horror story.

Later in the summer the European press reported that: ‘The UK’s second city Birmingham is bankrupt.’[4] Reports of school roofs falling in began to proliferate, over one hundred were unable to properly open in the autumn, more later, and large parts of some hospitals began to shut because the concrete above patients’ heads was now understood to be unsafe. Even an Oxford college had to put up tents because the dining hall was too dangerous to eat in [5]. A court in Germany refused to extradite a prisoner to the UK because basic living conditions and risks to life in British prisons were now so poor [6].

Figure 1: How the average height of five-year-old UK boys has changed since 1990, four ‘nations’

How the average height of five-year-old UK boys has changed since 1990, four ‘nations’

Source: Press Association (2023) British children shorter than other five-year-olds in Europe, study finds, ITV News, 21 June, https://www.itv.com/news/2023-06-21/b... [7]

You could have some sympathy for Starmer and Reeves as the bankrupt Britain news stories rolled in. Maybe it was true? Maybe we had to let the children go hungry and for them to become stunted, ever more stunted than in the mainland? A stunting that it was clear to see had begun when the heights of children born in the UK in 2005, aged five in 2010, began to no longer rise as much as in other nearby countries and then actually fell for those born in 2010, and even more for those born in 2015 (see Figure 1 for how this began before the Coalition government).

The stunting began under New Labour and then rapidly accelerated under the coalition Conservative-Liberal government. We will have to wait until children’s heights are next measured in 2025 to know whether there has been any slowdown in this tragic new trend. But we do now know that more and more children are going hungry in the UK, a majority (56%) of those with two or more siblings now several times a month. Going hungry can stunt your growth, as can poor quality cheap food.

However, at least going hungry if you have too many siblings is not the case in Scotland. So we expect the stunting to continue to England but not to have occurred to the same degree in Scotland where, throughout 2023, thanks to the Scottish Child Payment no child need now go hungry or be stunted in future [8]. Northern Ireland’ children should also fair a little better to as compared to those of England and Wales.

Perhaps someone thought it would be an interesting natural experiment to see what the effects of depriving poorer children of food in England (especially in the more expensive parts), but letting them still eat each day of the month in Scotland might be? We social scientists will be getting a lot of very useful data soon. It is just an enormous pity, a great shame, or depending on your political view even a social crime or great magnitude, that in the twenty-first century we are measuring the heights of children in the UK and asking why are they not growing as they should.

Destitution, unlike success in the football, it’s coming home.

As the summer of 2023 began, it was reported that in the most recent month: ‘one-in-eight social tenants (13%) and one-in-twelve private tenants (8%) had not eaten for a whole day for three or more occasions, because they did not have not enough money for food.’ The report explained that it was the families with children in these tenures were more likely to be among those went hungry, but so too were huge numbers of children whose parents had a mortgage, especially as interest rates rose. That report continued: ‘52% of those in the private rented sector feel their financial situation is making their mental health worse (this rises to 64% of private renters in receipt of Universal Credit or Housing Benefit).’ [9]

British born children were not suffering the worst of the new destitution. As always it is the most weak who suffer first, those with least power. New, and even more racist, immigration laws were proposed in 2023 to deny refugees even the most basic of rights, let alone food. ‘Freedom from Torture’ erected an additional blue plaque as the illegal migration bill was passed by parliament (but not yet implemented, see Figure 2 for the plaques). They reported that ‘Public figures from the Archbishop of Canterbury to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights have condemned this bill as immoral and legally dubious.’[10]

Figure 2: Blue plaques erected for the Home Secretary and the Prime Minster in 2023

Matilda Bryce (2023) Hey Suella, you’re on the wrong side of history – so we put up a blue plaque to show how your hostility will be remembered (Suella Braverman’s constituency office, Fareham), Freedom From Torture, 11 May, https://x.com/FreefromTorture/status/...

So the key question was, had the money really run out? Does Labour in England really have no option? Guardian journalist Polly Toynbee wrote in July 2023

‘Starmer’s comments about the two-child benefit cap on Sunday sent shock waves through Labour ranks: the party had attacked it time and again for affecting 1.5 million children, 1.1 million of whom are in poverty … This time, when there’s so much less money than in 1997, voters know promises are not credible unless backed with hard cash. Of course we Labour people yearn for a promise to return to the single market, for wealth taxes and the revival of every moribund public service. But only winning matters, so every obstacle has to be swerved, as the Tories try to turn attention away from their failures on the cost of living, the NHS, the economy and the climate.’[11]

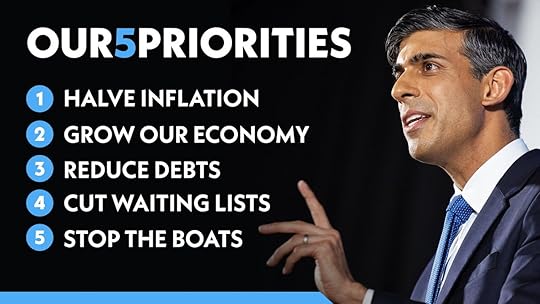

Figure 3: The Prime Minister’s five properties for 2023 (release on 4 January)

Prime Minister outlines his five key priorities for 2023, 4 January 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pr...

Toynbee was wrong. Sunak did then turn to talk more and more about the cost-of-living crisis, of cutting HS2 to Manchester, and numerous other initiatives. He suggested that he was dealing with it and did not obfuscate. He talked about the NHS and put cutting waiting-lists as his fourth priority [12], just above the small boats in his five pledges (Figure 3), and he did talk about the climate – it is just that he began to say we were doing too much too soon to try to reduce climate harm; but he did not swerve.

So does Labour have an alternative? Of course it does. Of course we need not have children being stunted in England. Of course we could still welcome refugees, not least because without them our future labour force looks weak! Destitution is coming home because that is what people in the UK are being sold as the only option by the main political parties. They are competing for a particular credibility by trying to demonstrate just how mean they can be [13]. And that, is far from good.

References

1. Pippa Crerar and Patrick Butler (2023) Labour would keep two-child benefit cap, says Keir Starmer, The Guardian, 16 July, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/...

2. Boris Johnson (2022) Resignation statement in full as Boris Johnson steps down, 9 June, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politic...

3. Ben Martin (2023) Debt, sickness and power sap UK’s finances, OBR finds, The Times, 14 July, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/de...

4. Cécile Ducourtieux (2023) The UK’s second city Birmingham is bankrupt, le Monde, 27 September, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/economy/art...

5. Maggie Wilcox (2023) St Catz replaces dining hall and JCR with marquees amidst RAAC review, Cherwell, 19 September, https://cherwell.org/2023/09/19/st-ca...

6. Katy Brady (2023) German court refuses extradition to U.K. based on prison conditions, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/...

7. Press Association (2023) British children shorter than other five-year-olds in Europe, study finds, ITV News, 21 June, https://www.itv.com/news/2023-06-21/b...

8. Liz Ditchburn (2023) Blog: why aren’t more people talking about the Scottish Child Payment? The David Hulme Institute, 18 September, https://davidhumeinstitute.org/latest...

9. Financial Fairness Trust (2023) Nearly 2m mortgagors struggling to pay for food, University of Bristol, 8 July, https://www.financialfairness.org.uk/...

10. Matilda Bryce (2023) Hey Suella, you’re on the wrong side of history – so we put up a blue plaque to show how your hostility will be remembered (Suella Braverman’s constituency office, Fareham), Freedom From Torture, 11 May, https://x.com/FreefromTorture/status/...

11. Polly Toynbee (2023) Listen up, critics: first let Labour win power. Then scrutinise its real record: Of course Keir Starmer is cautious in the runup to an election – Labour can’t change Britain from the opposition benches, The Guardian, 17 July, https://www.theguardian.com/commentis...

12. Prime Minister outlines his five key priorities for 2023, 4 January 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pr...

13. Suzanne Fitzpatrick, Glen Bramley, Morag Treanor, Janice Blenkinsopp, Jill McIntyre, Sarah Johnsen, and Lynne McMordie (2023) Destitution in the UK 2023, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/destitu...

For a PDF of this article and where it was first published click here.

October 23, 2023

Brexit – a failed project in a failing state

‘Fifty years on from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county [cricket] grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers, and—as George Orwell said—old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist.’

John Major’s speech to the Conservative Group for Europe, 22 April 1993

Thirty years ago, the Prime Minster suggested we had little to fear, that Britain would still be a country in which county cricket would be played in a weird English game where noth-ing much happens and no one really cares what the result is (when the match is ‘county’, meaning not international). He was describing the antidote to what was becoming an in-creasingly competitive and driven world, a society with increasing aspirations for excellence and productivity. County cricket implies that good enough is good enough, that it is ok to ‘coast’. Warm beer is good enough.

Warm beer may be an acquired taste and often not excellent, but it was our taste. Subur-ban housing was the least efficient way to house people ever invented, but it was our in-vention. Our British dog breeds would remain loyal and obedient, just as long as we fol-lowed Barbara Woodhouse’s advice, a darling of the 1980s British media, who promised ‘no bad dogs’ for followers of her books and television shows. We had British birds and British trees too, and when the middle class bought their children books they included titles, such as ‘one hundred British insects and invertebrates to identify in your British pond’. A few such items still exist from that past and some new posters are made each year for those who like them.

Picture of a mallard, ‘King Penguin K1 Book No. 1’, Penguin, 1939, painted by John Gould

Old maids could cycle happily and pray contentedly because they were English and England was that country which Mary Whitehouse was keeping safe from smut. We were part of the European Economic Community, but that would all come to an end shortly before Christmas 1993 after which we became a member of the European Union. We were also, and continue to be, the lowest social spending and (for the affluent) the lowest tax regime of any large country in that Union. Only Spain shortly after Franco had been in charge, and Greece shortly after the junta of the generals, spent less on public services.

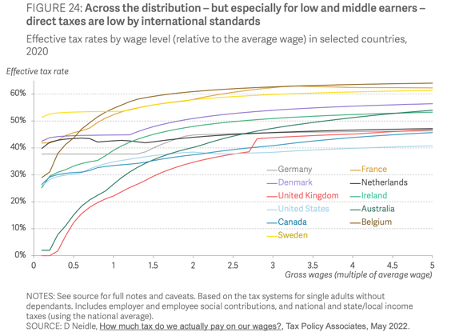

As the Resolution Foundation explained three decades later, ‘‘Tax policy choices help de-termine levels of inequality’, and UK politicians had not, in the immortal lyrics of Wham, chosen life, they chose instead, inequality.

The social failures of Brexit are, in one sense just part of a long history of social failure in a Britain dominated by England, an England dominated by the richest subjects of the mon-arch, people who mostly have at least one home in London.

In no other large country in Europe did people pay so little in direct taxation as in the UK in 2016 when the referendum was held. The poor paid very highly in indirect taxation, includ-ing through VAT and taxes on some particular goods that they more often consumed. But the poor in the UK had so little money that those taxes did not raise enough to sustain a well-functioning state in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Things were slowly falling apart. And we blamed the foreigners, the immigrants, immigration, and the European Union for allow-ing that immigration and all its weird rules (the ones that mostly only ever existed in our imaginations).

Note: the well-off pay very low taxes in the UK too, those earning 4 times average incomes pay the least in Europe.

We have a tendency to remember the past differently to how it really was, and to see as-pects of places as being unique which are actually much more universal. John Major in 1993 claimed that England was a country of long shadows, but the shadows were no longer than elsewhere in the remains of the day of our youth, and no different to shadows elsewhere in the world at our latitude. There are no special British shadows.

So too with the morning mist that he mentioned in the quote that begins this report, the dogs, the beer, the greenery. Suburban gardens in England are not some special and unique British green. But in one way Britain was already very different from other European states by 1993. No other state in Europe had just experienced such a huge rise in economic inequality – not one – and the social repercussions that followed from that.

John Major had been the last of Margaret Thatcher’s string of Chancellors of the Exchequer, the last of the men who presided over the fastest recorded tearing apart of the social fabric of a nation. He had followed in the footsteps of Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson. None of these Conservatives saw how they had cast dark shadows on a society to the extent that that there was, in Thatcher’s own words, no longer such a thing as society (‘…There are in-dividual men, and women, and there are families’ – she said, and too few asked why she thought that).

Conservative Britain was the imagined corner of a cul-de-sac, separated from its neighbours by a small stream, that would forever remain the same. Tory England, they believed, would be forever a powerful sceptred isle, another Eden, a demi-paradise, home to a happy breed of men, the envy of less happy lands, a blessed plot, a teeming womb of royal kings, of the true chivalry and of all those so numerous Christian religious services towards which old maids rode on cycles in the mist.

Source of (CC) Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/number1...

Almost a decade after John Major had tried to reassure the English that joining the Europe-an Union would alter nothing, at a private dinner in Hampshire in 2002, Margaret Thatcher was asked what her greatest achievement had been. She replied: ‘Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds’. New Labour then did nothing of any substantial effect to reverse the huge rise in inequality that John Major and his predecessors had socially engineered. Resentment and mistrust of others festered and grew.

.. continues (at great length)….

for the full report as a PDF and where it was originally published click here.

British society is heading for levelling down

In his new book “Shattered Nation: Inequality and the Geography of a Failing State”, Danny Dorling paints a bleak picture of life for many UK citizens today. Standards of living are falling across the country, yet policy-makers from across the political spectrum have failed to put forward effective measures to reverse this decline. In this Q&A with Bea White, he explains why radical change may be inevitable for a country that has run out of both money and options.

There is a perception that the shift to a Labour government in 1997 marked a sea change in British politics and efforts to make society fairer. But you argue that there was actually considerable ideological consensus between the New Labour and the Conservative government which preceded it. What is the evidence for this?

We had huge hope at first and Labour initially had a lot of credibility in the late 1990s. New Labour did do some good things – opening up to migration was a massive boost, and they increased health spending and spent more money on social housing.

It was only when I looked at the Gini coefficient of income inequality worked out by the OECD that I saw it hadn’t moved by more than 1 per cent in any year for 20 years. Our inequality was at a level where we managed to beat every other country in Western Europe. Now Bulgaria is the only country that’s more unequal than us.

The OECD ranking of countries by income inequality in October 2023. Source: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/inco...

So they didn’t change inequality. And it’s really only in hindsight that you look back see actually that was a massive failure. They wanted to seem competent. The technocrats took over. They wanted to grow the City of London – that was all about trickle down as the policy. The idea was the city gets bigger, so then we’ll have more Sure Start centres, and we’ll build brand new Academy schools. Brilliant. They built these schools in the poorest parts of town. It was great, but then suddenly we found that almost all secondary schools and universities had been privatised.

It was Labour that brought in £1000 a year tuition fees, and then raised it to 3000. It was Labour who made a deal that led to it becoming £9000 a year under the Conservatives. So they were absolutely in cahoots ideologically then, and they were in 1997 it just wasn’t quite as obvious.

When Thatcher was asked about her greatest achievement, she said “New Labour”.

What Tony Blair and Gordon Brown did by moving Labour rightwards is that they pushed the Tories way over to the right. It would have taken a super superhuman effort and ability and knowledge to turn around the biggest rise in European inequality which occurred under Thatcher. But when Margaret Thatcher was asked about her greatest achievement, she said “New Labour”.

You explain that Britain is an outlier in terms of its inequality levels across the board, in comparison to its neighbours but also in contrast to global trends. If British people are aware of this, why do they tolerate it?

I don’t think that people are aware of it. People do not know the real rate of child poverty, that the proportion of children who are poor in the southeast of England, that’s excluding London, is higher than Scotland. Hardly anybody is aware that that children in Scotland are less likely to be poor by the government’s official measure than those in the richest part of England (and that’s mainly something that occurred under New Labour). Hardly anybody knows that that there are more poor families per head in the southeast. In Oxford it is one third. We have babies being washed in cold water in now because people haven’t had their boiler on for 18 months. Unbelievable.

We think it’s inevitable. We think “Of course we’ve got to have retirement at age of 68, 69 or 70, they must be mad in France” or “We can’t possibly let in refugees like they let it in Germany.” We’ve become more American and less European in our thinking. Even if there is awareness, it’s just seen as pie in the sky.

You mention the disparity between England and Scotland. What is the impact of inequality on devolution and campaigns for it to be taken further?

The SNP [Scottish National Party] are criticised for not looking after public services enough, but they can only do that if they can raise taxes, by more than they are currently allowed to raise them. If you want to have a better housing system in Scotland, you can’t do that with some of the lowest taxes for people who are earning two or three times the average income. By low I mean lower than the take tax in other similar European countries on high earners. So it leads to pressure for greater devolution; it pushes towards more independent powers.

They and we are running out of money now in the UK. We can’t borrow more, we can’t tax it, we can’t print it because then the cost of food will go up too much. So we’re going to turn around to Scotland and tell them they’re going to have less money to spend in future. Labour have retaken a seat to Rutherglen, which they held at every election, apart from the last one, and now they think they’re going to sweep across Scotland. But things are different in Scotland now.

When it comes to addressing the spatial inequalities across the UK, do you think the Levelling Up agenda and its policies are taking an effective approach?

Well, at least we’re talking about it. But nothing that is currently being planned is going to make things more level.

In 2015, George Osborne promised that if we followed his economic plan we would be the richest country per capita on the planet by 2030, apart from a few tiny oil states. When Boris [Johnson] resigned, he made almost exactly the same promise, but slightly watered down. At the start of last summer, [Keir] Starmer makes the same promise, but only among the G7 countries. So we are promised the sunlit uplands every time, but it’s never as good as the last promise. And we are never going to get there given what’s happened to the country.

There comes a point when you can only tax the rich, otherwise people will starve.

So the most likely scenario is levelling down, because when the money runs out, you’re going to have to tax people at the top more. There comes a point when you can only tax the rich, otherwise people will starve. So we’re going to level, but it’s not up!

In higher education, we’ve seen increasing pressure on institutions from industrial action. How do you view these campaigns?

UCU, my union was arguing that people like me – a well-paid university professor needed a higher percentage increase than what we’re being offered because it’s still below inflation. They lost their dispute and I think that’s good news. It essentially means you can’t send your children to a private school, which the majority of academics in Oxford do. Or you can, but you’re going to have to ask more money from the grandparents.

It may be painful, but it’s actually levelling and it’s levelling down. The smallest pay increases are going to the highest paid people. My salary could go down by 10 per cent four times before life will get really difficult and I’ll still be much richer than most people in Oxford after that.

We’ve run out of money and the rich like me are going to have to become more normal. And the irony is this: It’s not [Jeremy] Corbyn doing this, it’s [Rishi] Sunak.

At the recent party conferences we saw the parties setting out their stalls towards the general election. Did you see indications that there will be policy proposals that might effectively address the issues you raise?

We’re a position now where we’re forced to address them – sterling has become a dangerous currency and there’s a real risk of the country going bankrupt.

The last time this happened was during World War One – when the war went on for so long that we had to raise money, and then we began to raise it from the rich as an emergency taxation that never went away. And then we became more and more equal, with levelling down for everybody.

What happened in the past was that – when the middle classes couldn’t afford to pay the doctor in the 1930s – that’s when a health service became a viable idea. We got comprehensives when the middle class could no longer afford to go private. Progressive things like the Health Service and comprehensive education have been driven by the middle class in their self-interest for their children because they’re not as rich as they were before. And it tends to be the middle class who get what they want.

Rishi Sunak promoting the Levelling Up agenda in 2021

It’s interesting Sunak has come out fighting on the anti-environment stuff. It wouldn’t take much for them to introduce some progressive policies – like a Sovereign Wealth Levy as an emergency measure on income over a certain amount. They could introduce tax policies that show a different ethos, even if they don’t raise much money.

What will [Keir] Starmer and [Rachel] Reeves do then, are they going to follow suit? Is Labour going to be the party of lower taxes for the rich?

And the policy that you can’t buy cigarettes from 14 onwards – that’s a that’s a nanny state policy. And it’s Sunak’s flagship policy!

You don’t become a society where people care for each other overnight.

There’s a danger we could become more unequal. And you don’t become a society where people care for each other overnight. Your children have to go to the same schools. It takes about two or three generations. When society becomes really unequal, we no longer think about each other as human beings. The lower orders are lower orders again. We need a shift in moral compass, decency, how people should be treated and thought about. And it happened before the question is: are we on the edge of it beginning again?

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here.

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers