Danny Dorling's Blog, page 33

November 10, 2017

7 New Maps of The World – School Geography A Level Talk

What does the world look like when you map it using data?

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford, invites us to see the world anew with 7 beautiful and unfamiliar world maps created by Ben Hennig.

These maps examine a wonderful range of geographical topics from globalisation to connectivity and challenge us to open our minds to a new, often unreported reality.

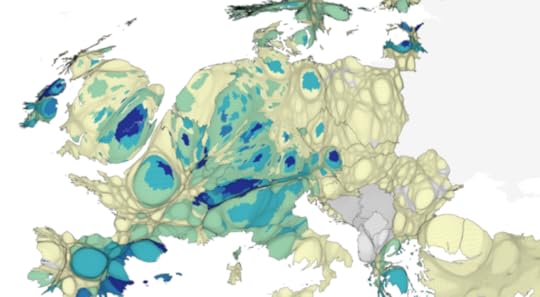

This is how Europe appears to me, with countries coloured according to when they joined the European Union, or how closely connected they are to it. And areas sized by their populations:

Major Cities of Europe labelled on an equal population cartogram

Again, here is another map of Europe with area drawn in proportion to population. Each area is shaded by the proportion of people living there not born in the state the region is in (data for 2014).

Each region of Europe is shaded by the proportion of the local population born in another country. Deepest blue is more than 20%

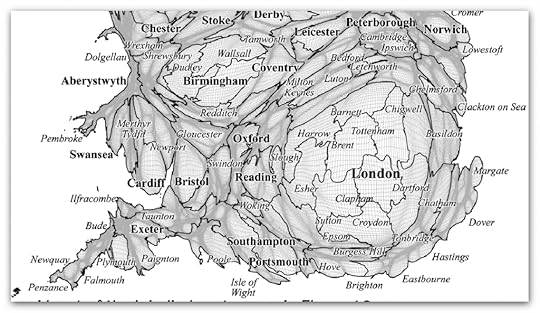

When we zoom into the south of the UK this is what we see:

Major cities and urban areas labelled on an equal population cartogram of the south of the UK

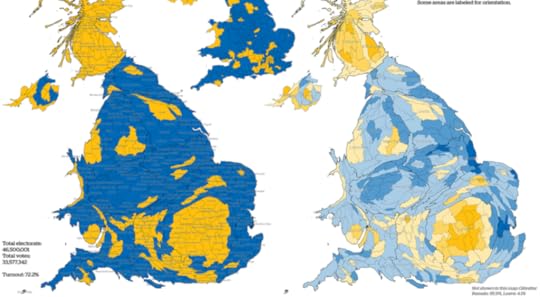

Because of differential turnout, a narrow majority of Leave voters lived in the South of England and most were middle class. Areas of high immigration voted to remain (albeit there was a minor ‘change’ effect where areas not used to migration voted leave).

Areas are shaded by whether a majority who voted voted to Leave or Remain and also by the proportions voting in these ways

Old maps in Geography textbooks used to look like this one – area not proportional to anything, but compass directions persevered as straight lines on a flat map.

Old map of the maximum extent of the British Empire

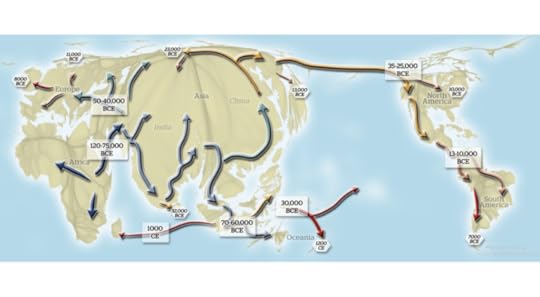

So – let’s look at seven new maps of the world starting with – Map 1: Humankind’s migration. This map shows the migration of humanity across the world based on what we currently know from mitochondrial DNA tracking. The map also shows approximate dates for arrival and dispersal in key locations. The underlying projection shows the relative population density on Earth today, resizing the land area based on the number of people living in each space.

The movement of humans across the world from when some left Africa on a global population cartogram base

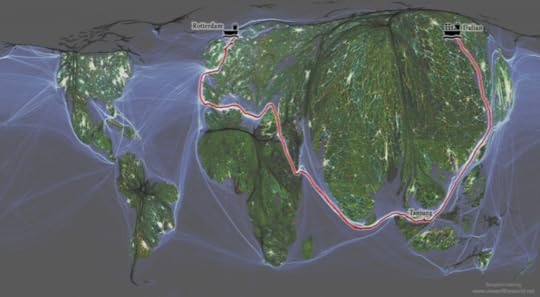

Map 2: Global connectivity. This map is a picture of the maiden voyage of MSC Oscar, which in 2015 was the world’s largest container ship: it went from Dalian, China to Rotterdam, Netherlands and is shown here in the context of the most frequent global shipping routes that can be seen in the background shown on an equal-population projection of the world. The projection shows the relative population density on Earth, resizing the land area based on the number of people living in each space.

The route of one of the world’s largest cargo ships from China to Europe

Map 3: World’s remotest places. This map shows the most remote places on the planet, the spaces where a ‘lonely planet’ can still be found. It shows areas larger, the further it takes to get to them via land travel from the nearest large city. This map and all the others shown in these slides was drawn by Ben Hennig who now works at the University of Iceland – a place that does not look that remote compared to Greenland, or the North of Canada or Tibet, but is if viewed from Europe.

Areas drawn with size in proportion to how far away they are from the nearest settlement of 50,000 people

You can zoom in and in to these maps and they sometimes change shape when you do so – because areas are affected by areas outside of the mapping box – here are the most remote places in the UK and Ireland – the more remote a place the larger it is drawn.

The further away by travel time from settlement an area is, the larger it is drawn

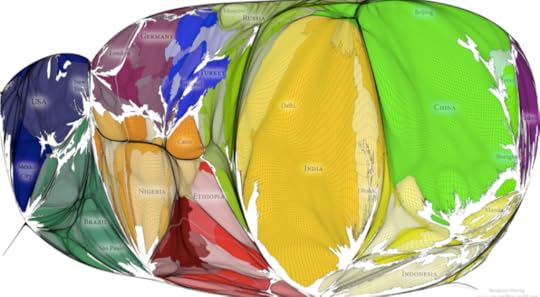

Map 4: A modern mappa mundi. This is a ‘mappa mundi’ of the modern world: in the map every small area is drawn in proportion to the population that lives there. Oceans are reduced in size to a minimum leaving almost no space between the continents. It shows today’s centre of the human planet to lie in India.

A population cartogram of the world with the seas and oceans shrunk

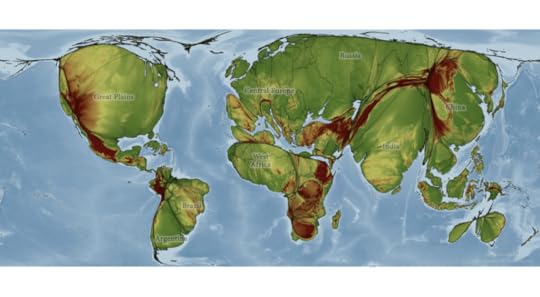

Map 5: Global croplands. Feeding a global population of 10 billion is one of the great challenges of the 21st century. This map is drawn to show where the most productive croplands are by increasing the size of those areas that are currently used for farming agricultural produce, while omitting those areas that are less suitable for agriculture or used for other purposes.

The world shaped with areas drawn in proportion as to whether they are used to produce crops

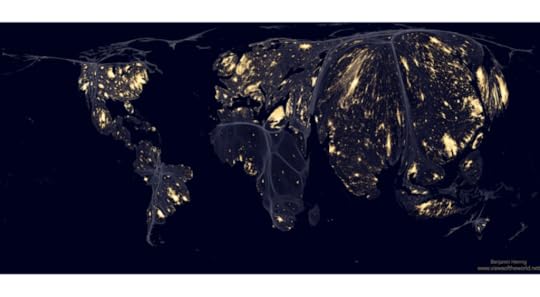

Map 6: Earth at night. This shows Earth at night on a population density map. Instead of highlighting the geographical land areas that are shining brightest at night, this map highlights where people live with and without light. The projection shows the relative population density in the world, resizing the land area based on the number of people living in each space.

The ‘Earth At Night’ composite satellite image drawn upon an equal population cartogram

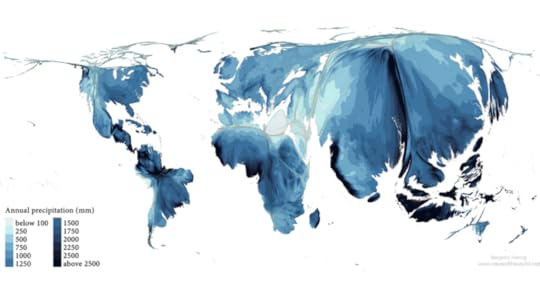

Map 7: Global precipitation patterns. This map shows the annual precipitation mapped onto a population distribution map. The underlying projection shows the relative population density on Earth today, resizing the land area based on the number of people living in each space.

Rainfall and snowfall quantities used to shade areas upon an equal population cartogram of the world

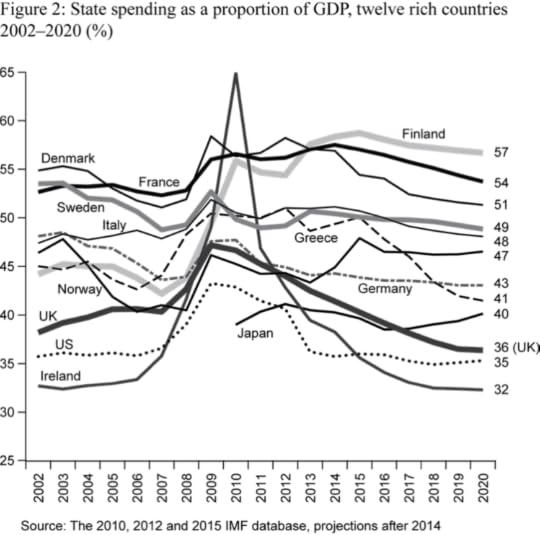

If you are interested in more about how contries compare, for instance by public spending according to the graph below, see here

The proportion of GDP spent on public services by different countries in the past and projected into the future by the IMF

And if you are interested in the book these seven maps appear in see here

November 3, 2017

Upholding the rule of law in the European Union

Open letter to Commission President Junker and European Council Presidents Tusk, 31 October 2017

UPHOLDING THE RULE OF LAW IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

Dear President Juncker, dear President Tusk:

We are scholars, politicians, public intellectuals and members of the European Parliament writing to you with the following concern:

The European Union has proclaimed the Rule of Law principle and respect for fundamental rights and freedoms to be binding on its Member States (Articles 2 and 6 of the Lisbon Treaty). The EU’s leadership has been a staunch protector of these fundamental norms, most recently in countering the Polish government’s attempts to undermine the independence of judges as well as the Hungarian government’s actions to limit civil society and media freedoms.

However, we are deeply concerned that the EU’s governing bodies are condoning the systematic violation of the Rule of Law in Spain, in particular regarding the Spanish central authorities’ approach to the 1 October referendum on Catalan independence. We do not take political sides on the substance of the dispute on territorial sovereignty and we are cognizant of procedural deficiencies in the organisation of the referendum. Our concern is with the Rule of Law as practised by an EU Member State.

The Spanish government has justified its actions on grounds of upholding or restoring the constitutional order. The Union has declared that this is an internal matter for Spain. Issues of national sovereignty are indeed a matter of domestic politics in liberal democracies. However, the manner in which the Spanish authorities have been handling the claims to independence expressed by a significant part of the population of Catalonia constitutes a violation of the Rule of Law, namely:

1/ The Spanish Constitutional Tribunal banned the referendum on Catalan independence scheduled for 1 October, as well as the Catalan Parliament session scheduled for 9 October, on grounds that these planned actions violate Article 2 of the Spanish Constitution stipulating the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation, thus rendering secession illegal. However, in enforcing in this way Article 2, the Tribunal has violated Constitutional provisions on freedom of peaceful assembly and of speech – the two principles which are embodied by referendums and parliamentary deliberations irrespective of their subject matter. Without interfering in Spanish constitutional disputes or in Spain’s penal code, we note that it is a travesty of justice to enforce one constitutional provision by violating fundamental rights. Thus, the Tribunal’s judgments and the Spanish government’s actions for which these judgments provided a legal basis violate both the spirit and letter of the Rule of Law.

2/ In the days preceding the referendum, the Spanish authorities undertook a series of repressive actions against civil servants, MPS, mayors, media, companies and citizens. The shutdown of Internet and other telecom networks during and after the referendum campaign had severe consequences on exercising freedom of expression.

3/ On referendum day, the Spanish police engaged in excessive force and violence against peaceful voters and demonstrators – according to Human Rights Watch. Such disproportionate use of force is an undisputable abuse of power in the process of law enforcement

4/ The arrest and imprisonment on 16 October of the activists Jordi Cuixart and Jordi Sànchez (Presidents, respectively, of the Catalan National Assembly and Omnium Cultural) on charges of sedition is a miscarriage of justice. The facts resulting in this incrimination cannot possibly be qualified as sedition, but rather as the free exercise of the right to peaceful public manifestation, codified in article 21 of the Spanish Constitution. The Spanish government, in its efforts to safeguard the sovereignty of the state and indivisibility of the nation, has violated basic rights and freedoms guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as by Articles 2 and 6 of the basic law of the EU (the Lisbon Treaty). The violation of basic rights and freedoms protected by international and EU law cannot be an internal affair of any government. The silence of the EU and its rejection of inventive mediation is unjustifiable.

The actions of the Spanish government cannot be justified as protecting the Rule of Law, even if based on specific legal provisions. In contrast to rule-by-law (rule by means of norms enacted through a correct legal procedure or issued by a public authority), Rule of Law implies also the safeguarding of fundamental rights and freedoms – norms which render the law binding not simply because it is procedurally correct but enshrines justice. It is the Rule of Law, thus understood, that provides legitimacy to public authority in liberal democracies.

We therefore call on the Commission to examine the situation in Spain under the Rule of Law framework, as it has done previously for other Member States.

The EU leadership has reiterated that violence cannot be an instrument in politics, yet it has implicitly condoned the actions of the Spanish police and has deemed the actions of the Spanish government to be in line with the Rule of Law. Such a reductionist, maimed version of the Rule of Law should not become Europe’s new political common sense. It is dangerous and risks causing long-term damage to the Union. We therefore call on the European Council and Commission to do all that is necessary to restore the Rule of Law principle to its status as a foundation of liberal democracy in Europe by countering any form of abuse of power committed by Member States. Without this, and without a serious effort of political mediation, the EU risks losing its citizens’ trust and commitment.

When this declaration appears, the crisis will have developed further. We follow closely the situation with the interests of democracy in Catalonia, Spain and Europe in mind, as they cannot be separated, and we insist all the more on the importance for the EU to monitor the respect of fundamental freedoms by all parties.

Signatories (in personal capacity):

Albena Azmanova, University of Kent

Barbara Spinelli, writer, Member of European Parliament

Etienne Balibar, université Paris Nanterre and Kingston University London

Cristina Lafont, Northwestern University, USA (Spanish citizen)

David Gow, editor, Social Europe

Kalypso Nicolaidis, Oxford University, Director of the Center for International Studies

Mark Davis, University of Leeds, Founding Director of the Bauman Institute

Ash Amin, Cambridge University

Yanis Varoufakis, DiEM25 co-founder

Rosemary Bechler, editor, openDemocracy

Gustavo Zagrebelsky professor of constitutional law, University Turin

Antonio Negri, Philosopher, Euronomade platform

Ulrike Guérot, Danube University Krems, Austria & Founder of the European Democracy Lab, Berlin

Costas Douzinas, Birkbeck, University of London

Judith Butler, University of California, Berkeley and European Graduate School, Switzerland

Philip Pettit, University Center for Human Values, Princeton University (Irish citizen)

Jón Baldvin Hannibalsson, former minister for foreign affairs and external trade of Iceland

Anastasia Nesvetailova, Director, City Political Economy Research Centre, City University of London

Craig Calhoun, President, Berggruen Institute; Centennial Professor at the London School of Economics

and Political Science (LSE)

Jane Mansbridge, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Arjun Appadurai, Institute for European Ethnology, Humboldt University, Berlin

Thor Gylfason, Professor of Economics at the University of Iceland and Research Fellow at CESifo,

Munich/former member Iceland Constitutional Council 2011

Judith Revel, Université Paris Nanterre

Robert Menasse, writer, Austria

Nancy Fraser, The New School for Social Research, New York (International Research Chair in Social

Justice, Collège d’études mondiales, Paris, 2011-2016)

Roberta De Monticelli, University San Raffaele, Milan.

Sophie Wahnich, directrice de recherche CNRS, Paris

Christoph Menke, University of Potsdam, Germany

Robin Celikates, University of AmsterdamEric Fassin, Université Paris-8 Vincennes – Saint-Denis

Alexis Cukier, Université Paris Nanterre

Diogo Sardinha, university Paris/Lisbon

Dario Castiglione, University of Exeter

Hamit Bozarslan, EHESS, Paris

Frieder Otto Wolf, Freie Universität Berlin

Gerard Delanty, University of Sussex

Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Coimbra University and University of Wisconsin-Madison

Sandro Mezzadra, Università di Bologna

Camille Louis, University of Paris 8 and Paris D

Philippe Aigrain, writer and publisher

Yann Moulier Boutang and Frederic Brun, Multitudes journal

Anne Querrien and Yves Citton, Multitudes journal

Susan Buck-Morss, CUNY Graduate Center and Cornell University

Seyla Benhabib, Yale University; Catedra Ferrater Mora Distinguished Professor in Girona (2005).

Bruce Robbins, Columbia University

Michèle Riot-Sarcey, université Paris-VIII-Saint-Denis

Zeynep Gambetti, Bogazici University, Istanbul (French citizen)

Andrea den Boer, University of Kent, Editor-in-Chief, Global Society: Journal of Interdisciplinary

International Relations

Moni Ovadia, writer and theatre performer

Guillaume Sibertin-Blanc, Université Paris 8 Saint-Denis

Peter Osborne, Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, Kingston University, London

Ilaria Possenti, University of Verona

Nicola Lampitelli, University of Tours, France

Yutaka Arai, University of Kent

Enzo Rossi, University of Amsterdam, Co-editor, European Journal of Political Theory

Petko Azmanov, journalist, Bulgaria

Etienne Tassin, Université Paris Diderot

Lynne Segal, Birkbeck College, University of London

Danny Dorling, University of Oxford

Maggie Mellon, social policy consultant, former executive member Women for Independence

Vanessa Glynn, Former UK diplomat at UKRep To EU

Alex Orr, exec mbr, Scottish National Party/European Movement in Scotland

Bob Tait, philosopher, ex-chair Langstane Housing Association, Aberdeen

Isobel Murray, Aberdeen University

Grahame Smith, general secretary, Scottish Trades Union Congress

Pritam Singh, Oxford Brookes University

John Weeks, SOAS, University of London

Jordi Angusto, economist at Fundació Catalunya-Europa

Leslie Huckfield, ex-Labour MP, Glasgow Caledonian University

Ugo Marani, University of Naples Federico II and President of RESeT

Gustav Horn, Scientific Director of the Macroeconomic Policy Institute of the Hans Böckler Stiftung

Chris Silver, journalist/author

James Mitchell, Edinburgh University

Harry Marsh, retired charity CEO

Desmond Cohen, former Dean, School of Social Sciences at Sussex University

Yan Islam, Griffith Asia Institute

David Whyte, University of LiverpoolKaty Wright, University of Leeds

Adam Formby, University of Leeds

Nick Piper, University of Leeds

Matilde Massó Lago, The University of A Coruña and University of Leeds

Jim Phillips, University of Glasgow

Rizwaan Sabir, Liverpool John Moores University

Pablo Ciocchini, University of Liverpool

Feyzi Ismail, SOAS, University of London

Kirsteen Paton, University of Liverpool

Stefanie Khoury, University of Liverpool

Xavier Rubio-Campillo, University of Edinburgh

Joe Sim, Liverpool John Moores University

Hannah Wilkinson, University of Keele

Gareth Dale, Brunel University

Robbie Turner, University of St Andrews

Will Jackson, Liverpool John Moores University

Louise Kowalska, ILTUS Ruskin University

Alexia Grosjean, Honorary member, School of History, University of St Andrews

Paul McFadden, York University

Phil Scraton, Queen’s University Belfast

Oscar Berglund, University of Bristol

Michael Lavalette, Liverpool Hope University

Owen Worth, University of Limerick

Ronnie Lippens, Keele University

Andrew Watterson, Stirling University

Steve Tombs, The Open University

Emily Luise Hart, University of Liverpool

David Scott, The Open University

Bill Bowring, Birkbeck College, University of London

Sofa Gradin,King’s College London

Michael Harrison, University of South Wales

PDF of letter here

October 26, 2017

Why student loans are a confidence trick for the 85%

The current system of university student funding in England is a confidence trick. It is an attempt to defraud a group of people – poorer students and their families – after having gained their trust by pretending that the system is fair and they will be treated equally. Confidence tricks work by exploiting human traits such as naivety and compassion.

Prospective students are told that it is only fair that they take out a loan to fund their studies at university because otherwise poorer people who do not go to university will, in some way, lose out. They are told that they will on average earn so much more than these people in the future that it is only right that they take out a loan.

A desire for inequality?

These arguments are based on untruths and a desire among some, latent or otherwise, for our future society to be even more unequal. Already the UK has the widest income inequality of any European country other than Lithuania. The Gini coefficient of income inequality, as measured by the OECD, is higher in the UK than it is in Israel, and only just a little lower than that of Russia. It is highly unequal countries, such as the USA and Chile, that tend to introduce the most costly and unfair student loan systems. Chile is also the only OECD country to spend more as a proportion of all secondary spending on private schools, than does the UK.

The only way the current student loans system in England can be justified is if we want the UK to continue being ‘the large country with the widest income inequalities in Europe’ for many decades to come. There is a small minority of English people who do think this is a good idea, but most don’t. For instance, 72% of people in Britain support measures such as maximum salaries for those within the top 1% of earners, 70% support higher top income tax rates, and 62% support a wealth tax on very expensive properties.

We have known that loans are unjust for some time. Even before 2012 when university fees were tripled in size:

‘…debt is unequally distributed. Students who are poor before going to university are more likely to be in debt and to leave university with the largest debts, while better-off students are less likely to have debts and leave with the lowest debts. In 2003, students whose parental annual income was less than £20,480 owed an average of £9,708, and half owed more than £10,392. Students with parental incomes over £30,502 owed just £6,806. So on graduation, the poorest students were 43 per cent more in debt than the richest.’

Students studying at university in France, Germany, Italy and Austria pay just a few hundred Euros a year in fees. In Scotland and Scandinavia they pay no fees at all. One reason that has been suggested for high fees in England is that ‘Oxford, Cambridge and Imperial College London – rank in the planet’s top 10’ when it comes to university league tables. Interestingly, English institutions top European university league tables (tables produced in England). Yet, adults in England up to age 24 are at the bottom of ability when compared to their European peers in mathematics, relatively poor at problem solving, and in the bottom half of the distribution for literacy.

Read more from the full article this extract is taken from.

The argument is expanded further in Danny’s latest book: “Do We Need Economic Inequality?”

October 25, 2017

Turning The Tide On Inequality

It is hard to believe that it is any coincidence that by far the most economically unequal large country in the European Union, the UK, was the one that narrowly voted to leave it in 2016. The UK has severe social problems due to severe economic inequality. These include an inability to see unfairness as a problem, and a susceptibility to simplistic immigration-blaming arguments.

The remainder of Europe enjoys greater equality. In every other large European country the ruling elite are far more closely connected to the people because they are economically less separated. Living standards for the median family in France and Germany are higher than in the UK, and the quality of housing is higher.

The UK recently provided the best warning within Europe of what goes wrong when you allow inequality to rise and rise ever higher. Nevertheless, there remain wide variations in economic inequality within mainland Europe that may well also be very instructive.

After the UK, the second most unequal large country in the EU is Spain. For those of us that have studied inequalities for many years there is a somewhat depressing regularity emerging between where a country ranks on the league table of economic inequality, and then its economic, social, and political difficulties.

People may say that the issue of separatism in Spain has little to do with economic inequality; but higher inequality between households within a country is often a symptom of so much more going wrong. As the former BBC economics editor Duncan Weldon recently put it when trying to explain the rise of Trump in the USA: “it’s the inequality stupid”. Weldon was not talking about the inequality between US states, but the inequality between families within those states.

Spain is not as unequal as the UK or USA. It is at no risk of leaving the EU or starting a war with North Korea. But you might be left wondering whether its national government would deal better with devolution, identity and autonomy in Catalonia if Spain taken as a whole were more equitable as a society. The ruling elite in Madrid might make fewer mistakes were Spain as cohesive as France and Germany have become. What matters most is the inequality between individuals and households in a country. The most equitable countries in the world, Norway, Sweden and Japan have few secessionist movements, much less militaristic posturing, and tend not to elect fools to high office.

Extract from a longer article published by “Social Europe” on October 25th 2017 which in turn is taken from the new book “Do we need economic inequality”

October 18, 2017

Inequality and Insurrection

Seminar by Danny Dorling in a series helping to celebrate 25 years of Development Studies in SOAS, University of London, given on October 17th, 2017

Insurrection is an uprising. Analysts and commentators on inequality have long warned that if inequality is allowed to rise too high there will be insurrection. Thomas Piketty suggested this is why elites should concern themselves with inequality.

Politicians often confuse sounding as if they care about inequality with actually caring.

This talk provides some illustrations of how things fall apart as inequality rises, when it is high and when it is tolerated. It suggests that only the most economically unequal of affluent states consider it to be reasonable to impose high private fees and student loans on education, spread debt across the young and promote precarity.

There comes a point when most people can no longer be fooled into believing that all this is fair.

Read More – on “Do We Need Economic Inequality?

October 9, 2017

Beware of Kipling-spouting politicians

The world isn’t a plum pudding anymore. It’s time for Britain to stop pretending it can carve it up—and scrap its Imperialist approach to post-Brexit trade.

Opinion piece in Prospect on-line by Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson, October 9th 2017

In October 2017, Joris Luyendijk made a heart felt plea to the English in the pages of Prospect magazine:

“Why would you allow a handful of billionaires to poison your national conversation with disinformation—either directly through the tabloids they own, or indirectly, by using those newspapers to intimidate the public broadcaster? Why would you allow them to use their papers to build up and co-opt politicians peddling those lies? Why would you let them get away with this stuff about ‘foreign judges’ and the need to ‘take back control’ when Britain’s own public opinion is routinely manipulated by five or six unaccountable rich white men, themselves either foreigners or foreign-domiciled?”

To try to answer Joris is difficult, but we are both English academics who have looked at the changing social geography of the country and how the English have been taught a particular version of their history. A huge problem is that many among us have still not yet accepted that our place in the world is not at the very top.

Had Joris been writing a few days earlier he might also have asked about why the British Ambassador had to tell his near namesake, Boris, to shut up when he was about to say something extremely offensive at a temple in Myanmar. It was, apparently, because Boris didn’t understand just how offensive it was for him to recite the lyrics of a Rudyard Kipling poem about a British soldier kissing a Burmese girl. Worse still, there is the possibility Boris did understand how offensive he was being, but did it deliberately to court favour among a certain camp at home.

The Plumb-pudding in danger – or – State Epicures taking un Petit Souper by Gillray

The Plumb-pudding in danger – or – State Epicures taking un Petit Souper by Gillray. Picture: British Library

Boris’ tone-deaf stunt is unfortunately indicative of a wider issue. Almost two centuries ago, sometime around 1818, James Gillray drew a cartoon of William Pitt and Napoleon Bonaparte desperately attempting to carve up the world, which appears as a plum pudding. These days, the carving is done by trade deal rather than sword. So where have we got to with those brilliant trade deals planned with the rest of the world after Brexit?

In September 2017, with less than eighteen months to go before the leaving bell tolls, the EU’s chief negotiator (Michel Barnier) told the world that the UK’s approach to leaving the Union was “nostalgic, unrealistic and undermined by a lack of trust.” Two weeks later, Prime Minister May suggested adding another two years before Brexit, prolonging the uncertainty and lack of clarity on trade deals; and not helping display any further signs of trust.

October 5, 2017

Economic inequality – what is it good for?

Inequality has become the defining issue of our times. It is what makes the years we are currently living through so different to those of our parents and grandparents.

Political opinion in the UK in 2017 changed at a faster rate than it has changed in many decades. This statement is true if the measure of opinion used is voting intention in polling in May, or the swing in the general election held in June.

The Labour Party rightly raised the issue of economic inequality repeatedly during the election campaign. The Conservative election manifesto advocated meritocracy as a solution, maintaining inequalities but trying to ensure that those who (they suggested) deserve the most get the most. This is part of their logic for high student fees and loans. They suggest these are reasonable as in future we should still expect to be living in a very unequal society where graduates receive much higher pay than other people.

So who are the special people, and does rewarding them much more than others really benefit all? Or has the UK become an example of political incorrectness gone mad; a place that accepts terrible inequalities as if they are reasonable and fair? The UK is now the European country with the widest income inequalities of them all. It is the poster-country for what happens if you let the rich take more and more and more. Many things go badly wrong. The population becomes desperate for change. They are told to blame shirkers, blame immigrants, blame anything but inequality. And they are told this by the few who have taken so much for so long and done such great damage.

Audio recording of a talk by Danny given in St Aldate’s Pub in Oxford based on the book “The Equality Effect” and also informed by recent events:

October 3, 2017

Delayed discharges: “up to 8,000 people die every year because of bed-blocking on NHS wards”

The increased prevalence of patients being delayed in discharge from hospital in 2015 was associated with increases in mortality, accounting for up to a fifth of mortality increases. The study by Mark Green, Danny Dorling, Jon Minton and Kate Pickett of the Universities of Liverpool, Glasgow, Oxford and York, provides evidence that a lower quality of performance of the NHS and adult social care (as a result of austerity) may be having an adverse impact on population health.

2015 saw the largest annual increase in mortality rates across the UK for almost 50 years, and mortality rates have remained high since. During the same period there have been funding crises and poorer quality of care within the NHS and adult social care.

We demonstrate a positive association between the number of patients delayed in being discharged, and the cumulative amount of time patients were delayed, to the monthly number of deaths and mortality rate. Our results present evidence that a lower quality of performance between the NHS and adult social care may explain part of the increases in mortality rates experienced in England from at least 2015 and onwards.

Reactions: The Guardian: “NHS England declined to comment. A Department of Health spokesman said: “Whilst the results of this research are limited, we are clear that no one should have to stay in a hospital bed longer than necessary.’

The Times: ‘About a fifth of the increased deaths in England and Wales between July 2014 and June 2015 may have been caused by delayed discharge from hospitals’.

The Telegraph: ‘researchers said other explanations – such as flu, the ageing population and random fluctuations could not fully explain the trends. They said the delayed discharges – which are often caused by an inability to arrange adequate social care in the community for people leaving hospital – could be preventing other, sick people from being admitted to hospital for the care they need. “While mortality rates fluctuate year on year, this was the largest rise for nearly 50 years and the higher rate of mortality has been maintained throughout 2016 and into 2017,” the authors wrote in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.’

The Yorkshire Post: reacted by explaining that ‘Meanwhile, those stuck in hospital may experience more stress and anxiety, and could receive less-good care as time goes on.’ Earlier the BBC had explained that some patients were now: ‘dying alone due to lack of NHS staff’ while Sky News reported that Jeremy Hunt the ‘Health Secretary says he disagrees with a Tory minister’s suggestion that the NHS is “close to collapse” amid rising costs of care.’

And the Daily Mail: reported that: ‘The scale of bed-blocking in the NHS is the worst it has ever been, with nearly 4,500 people trapped in hospital at any given time. The problem has more than doubled in the past seven years – from 55,332 beds that were blocked for a whole day in August 2010 to 118,131 in July 2017.’

Links to the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health to read the full paper are here

The scandal of unequal and poor health outcomes and service provision is deepening as the UK government continues to choose to fund its public services at extremely low levels (click on image below, or for more information on health spending click here):

Public Spending in proportion to GDP in twelve rich countries

September 26, 2017

The New Urban Crisis by Richard Florida – a Review

This limited survey of the effects of inequality and high house prices in cities is part of the problem, not the solution.

There is something quite shocking about seeing a new contemporary map of London in which the rich areas are labelled “primarily creative class” and the poorer parts “primarily service class”. But this is how the American writer and Toronto University professor Richard Florida portrays cities and sees people. There are those who create and those who serve them.

The book opens with its author recounting what his taxi driver told him on the way in from the airport about all the empty luxury flats in London. This feeds into his theory that the “new urban crisis” is about inequality and house prices, and would apparently be solved if only they could both be reduced a little. However, ending the real crisis might not be that simple.

Presumably the taxi driver was “service class” and Florida, who describes himself as “one of the world’s leading urbanists”, is a “creative”, but is what he is creating useful or harmful? Just above his map of London in the book, he claims that “surprisingly, there is not a single tract in London where the working class makes up a plurality of residents…” That claim is wrong, of course, but so are many of the ideas in this flawed book.

Illustration by Joseph P Kelly

Image drawn by Joseph P Kelly

September 19, 2017

Full text of original letter sent to the Financial Times: Examining the numbers on pension valuations

We are concerned about the transparency of decision making in the USS pension scheme. The USS has announced a substantial deficit, but the data and methods they have published are very limited, making them impossible to judge.

The USS manages £60bn in assets on behalf of its members. The most recent USS accounts and reports indicate the scheme has a large deficit. However, the USS provides insufficient information about the methods used to value its assets and liabilities. They present no confidence intervals around the point estimate of the deficit, indication of estimation error, or any sensitivity analyses. They provide virtually no details of what data or analytic code they used to come to their conclusions. Even the CMI 2014 report underpinning the mortality assumptions is not publicly

available.

The USS and Mercer list the assumptions used on page 106 of the most recent report. They also indicate how they have changed the assumptions between 2013 and 2017. In brief, they assume:

1. A fall in the expected long-term nominal investment return from 4.7% to 2.8%.

2. An increase in general pay growth from CPI (2.6%), to RPI + 1% (4.4%).

3. Life expectancy increasing by 1.5% per year.

We find these assumptions curious. First, how can expected investment returns have fallen by 40% in four years? Surely a collapse in returns on this scale would be reflected in the equity or bond markets? Equity markets in high income countries are up 51.7% in the last four years (11% per year). Their assumptions are consistent with a 0.33% per year return on investments after CPI. Is this rate of return possible without a global recession?

Second, in 2014 the USS assumed cumulative pay growth over the following four years of 16%. Yet general pay increases have fallen well short of this, cumulatively increasing by 5.8%. Their estimates of the deficit assume that in future general pay will rise at a rate of RPI +1% (4.4% per year). Is there any evidence that universities will award cost of living increases at this rate? Furthermore, the ONS and the RSS has repeatedly warned that the RPI is a flawed measure of inflation, and should not be used. So why are the USS using it to estimate the deficit?

Third, there has been little increase in life expectancy since 2011. The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries estimates that mortality is around 11% higher in 2016 than would have been expected based on the historical trend. This means life expectancy is lower, which will lower the USS’s liabilities.

A shorter version of this letter was published by the Financial Times on September 19th 2017. The link to that and a PDF of this version can be found here

Prof Steven Julious

Professor of Medical Statistics, University of Sheffield

Prof Mark Gilthorpe

Professor of Statistical Epidemiology, University of Leeds

Dr Fred Martineau

Clinical Research Fellow, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Abigail Fraser

Reader in Epidemiology, University of Bristol

Prof Danny Dorling

Professor of Geography, University of Oxford

Prof Yoav BenShlomo

Professor of Clinical Epidemiology, University of Bristol

Dr Rhian Daniel

Reader in Medical Statistics, Cardiff University

Sedona Sweeney

Health Economist, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Ben Goldacre

Senior Clinical Research Fellow, University of Oxford

Prof Charles Taylor

Professor of Statistics, University of Leeds

Dr Joanna Reynolds

Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Sandra Mounier-Jack

Associate Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Steven Haberman

Professor of Actuarial Science, Cass Business School, City, University of London

Prof Andrew Clare

Associate Dean, Cass Business School

Dr William Johnson

Lecturer, Loughborough University

Prof Kate Tilling

Professor of Medical Statistics, University of Bristol

Catherine Pitt

Assistant Professor of Health Economics, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof George Davey Smith

Professor of Clinical Epidemiology, University of Bristol

Dr Eleanor Hutchinson

Assistant professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Professor David Spiegelhalter

Professor of Biostatistics, University of Cambridge

Dr Tara Beattie

Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Saul Jacka

Professor, University of Warwick

Prof Martin Bobak

Professor of epidemiology, University College London

Dr Beniamino Cislaghi

Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Jonathan Sterne

Professor of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, University of Bristol

Dr Luisa Zuccolo

Senior Research Fellow, University of Bristol

Dr Natasha Howard

Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Neil Davies

Research Fellow, University of Bristol

Prof Tim Cole

Professor of medical statistics, University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health

Dr James Woodcock

Programme Lead, University of Cambridge

Dr Hynek Pikhart

Reader in Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, University College London

Dr Ana Maria Buller

Deputy Director Gender, Violence & Health Centre, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Shelley Lees

Associate Professor in Anthropology of Gender, Violence and HIV, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Graham Medley

Professor of Infectious Disease Modelling, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Marcus Munafò

Professor of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol

Dr Josephine Borghi

Associate Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Peter Green

Professorial Research Fellow, University of Bristol

Dr Sam Marsh

Teaching Fellow, University of Sheffield

Prof Guy Nason

Professor of Statistics, University of Bristol

Prof Chris Metcalfe

Professor of Medical Statistics, University of Bristol

Dr Laura Howe

Reader in Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, University of Bristol

Benjamin Palafox

Research Fellow in Pharmaceutical Policy & Economics, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Fern Terris-Prestholt

Associate Professor in the Economics of HIV, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Krishnan Bhaskaran

Associate Professor in Statistical Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Bianca De Stavola

Professor of Medical Statistics, University College London

Prof Martin McKee

Professor of European Public Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Clare Chandler

Associate Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Aaron Reeves

Associate Professorial Research Fellow, London School of Economics

Matthew Quaife

Research Fellow, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Dr Giulia Greco

Assistant Professor and MRC Fellow, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Caroline Relton

Professor, University of Bristol

Prof Qiwei Yao

Professor of Statistics, London School of Economics

Dr Melisa Martinez-Alvarez

Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Prof Simon Wood

Professor of Statistical Science, University of Bristol

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers