Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 10

July 23, 2024

Prodigal Sons in Sense and Sensibility, by Joyce Kerr Tarpley

Sense and Sensibility, more than any of Jane Austen’s other novels, is about sonship. Elsewhere I have considered two themes regarding sonship in this novel: the theme of promise-keeping and the theme of primogeniture. For the latter theme, the Bible’s Old Testament, specifically the book of Genesis, is the focus for my reading of sonship. For the present reading of sons and brothers in Sense and Sensibility, I turn once again to the Bible, this time to the New Testament Parable of the Prodigal Son. In The Prodigal Son in English and American Literature (2018), Alison M. Jack cites a commentator who explains its appeal to readers (and writers): “[M]ore than any other parable, this one—in part because of its domestic setting—has captured the imagination and emotions of readers.” Besides being the most well-known, it is also “the longest and most narratively complex” (2) of Jesus’s Parables. As such, it is an appealing literary choice for representing sons and brothers in Jane Austen’s unparalleled domestic settings.

(From Sarah: This is the eleventh guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Mansfield Park has more sons (six) and one clear-cut prodigal (Tom Bertram); however, Austen plays with the Parable as she does with the Genesis narrative in Sense and Sensibility (“Playing with Genesis”). In the original New Testament version (Luke 15:11-32), the younger son demands his inheritance, travels to a “far country” where he squanders it, suffers, experiences an epiphany, and returns to confess his sins to his father and seek redemption. In the meantime, the elder son dutifully stays home, but when his father forgives the sins of his younger “prodigal” brother and throws a party to celebrate his “rebirth,” the elder brother expresses self-righteous anger. The Parable ends with an expression of unconditional love for both sons by their God-like father figure.

Austen switches the roles with the Ferrars sons. Robert Ferrars, the younger “favorite” son, stays home with their mother. The elder son, Edward, goes away for his schooling (to Plymouth) and is essentially homeless while waiting for his mother, whose “conditional” love requires strict obedience to her wishes, to give him his inheritance. There is no God-like father figure in the novel because Austen, as a comic writer, is most interested in exploring the way in which her characters overcome their weaknesses and flaws—or the way in which they fail to do so.

In the case of the Brandons, the father sends his younger son away—exiles him to a “far country”—in order to marry off the elder son to his ward, Eliza, whose inheritance is needed to salvage the estate. Finally, in another reversal of the Parable, the elder Brandon brother squanders his inheritance and puts the estate at risk while the younger Colonel Brandon comes home (after his elder brother’s death) to save it. Willoughby, the third important son in the novel, has no brother, but like the Prodigal Son, his confession plays a major role in the novel.

“I have sinned against heaven and in thy sight” (Luke 15:18)

The key scene for Jesus’s Prodigal Son comes when he acknowledges his sins during a brief confession to his father. In Sense and Sensibility, each son who is a potential hero—Colonel Brandon, Edward Ferrars, and John Willoughby—has a confession scene during which he explains his sins to Elinor, who is the next best thing to the Parable’s father figure. Willoughby’s confession comes closest to the Prodigal Son’s because he commits the most serious sins, and he is most in need of redemption. Insofar as the confession scene is similar to the Parable, what is most noteworthy is Elinor’s willingness to forgive Willoughby, a reprobate who wreaks havoc in the lives of three women—Eliza, Marianne, and Miss Grey. Her forgiveness, despite her own recognition of Willoughby’s flaws, brings her closest to the role of the father figure in the Parable.

What’s Wrong with Willoughby’s “Confession”

Unlike the Prodigal Son in the Parable, Willoughby’s confession is neither an acknowledgement nor a repentance for his sins. His primary sin is his seduction of the fifteen-year-old Eliza, whom he left pregnant, helpless, and alone in Bath without any way to contact him. Hebrews 13:4 states the rules for Christian sexual conduct, which he has violated: “Honor marriage and guard the sacredness of sexual intimacy between wife and husband. God draws a firm line against casual and illicit sex” (Hebrews 13: 4, The Message). Moreover, according to nineteenth-century ecclesiastical law, “Willoughby’s behavior, including his sexual relationship with Eliza, is itself an implicit promise to marry her” ( “Sonship, Liberty, and Promise-Keeping”). Yet Willoughby neither acknowledges this behavior as a sin nor does he seek forgiveness for it. Instead, he blames Eliza for “the violence of her passions, [and] the weakness of her understanding,” and for not having the “common sense” to find out his whereabouts—even though he admits to not recollecting that he “had omitted to give her any direction” (Volume 3, Chapter 3).

His second sin is bearing false witness, thereby breaking one of the Ten Commandments. During his marriage ceremony to Sophia Grey, his vows are false—lies, in essence, made before God. “[F]or St. Thomas Aquinas, the vow is a commitment to God that ‘one may promise in one’s heart’” (Summa Theologica II-II. 88.1; Bronaugh 5). Moreover, his attitude toward his wife is one of contempt. He blames her, just as he does Eliza, rather than confessing that it was wrong to use her for her money when he cares nothing for her: “Do not talk to me of my wife . . . . She does not deserve your compassion—She knew I had no regard for her when we married” (Volume 3, Chapter 8).

Ironically, Willoughby is most sorry about his treatment of Marianne. By comparison, however, with his sins against Eliza and Ms. Grey, his treatment of Marianne, although cruel and thoughtless, does not rise to the same level.

Why does Willoughby confess? Two suggestive comments—one about his marital status and the other about Marianne’s—indicate that Willoughby’s motive is forgiveness with a catch—he hopes for another chance with Marianne. He fantasizes about “being at liberty again,” meaning his wife would be dead; he fantasizes about Marianne “being at liberty,” meaning he lives “in dread” of her marriage (Volume 3, Chapter 8). Willoughby, then, is still the selfish libertine who not only refuses to acknowledge his past sins, but also contemplates sins in the future. “[B]y that still ardent love for Marianne, which it is not even innocent to indulge” (Volume 3, Chapter 9), Willoughby dishonors his marriage by means of a death wish that according to Jesus’ standard (Matthew 5:28), would amount to adultery. In “Sense and Sensibility and Sin,” William Jarvis says Willoughby gives a “self-regarding confession, lacking in real penitence or any intention of reparation or amendment” (59).

If such is the case, why does Elinor forgive him? Patricia Meyers Spacks attributes Elinor’s forgiving change of heart to “a high proportion of sensibility in her make-up” and to Willoughby’s “sex appeal” (373, fn. 2). Jarvis, however, attributes it to Elinor’s “Christian and practical attitude” (59). Elinor’s forgiveness of Willoughby may seem to be unconditional; however, while she feels sorry for his loss, she recognizes that her “regret [is] rather in proportion to his wishes than to his merits” (Volume 3, Chapter 9). Elinor is affected by Willoughby’s powers but she is not unaware of being so.

In Jesus’s parable, the Prodigal Son’s confession and repentance allow him to “come home,” to be forgiven by his father, and to be restored to his family. In spite of Elinor’s forgiveness, however, Willoughby’s blindness to his sins will continue to block his happiness and his homecoming.

Quotations are from the annotated edition of Sense and Sensibility, with an introduction by Patricia Meyer Spacks (2013). The flower photos were taken last week at the Met Cloisters in New York City, by Sarah.

Works Cited

Bronaugh, Richard N. “Thomas Aquinas on Promises.” The Medieval Tradition of Natural Law. Ed. Harold J. Johnson. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan U, 1987. 1-5.

Jarvis, William. Jane Austen and Religion. Oxford, Stonesfield Press, 1996.

Tarpley, Joyce Kerr. “Playing with Genesis: Sonship, Liberty, and Primogeniture in Sense and Sensibility.” Persuasions 33 (2011), 89-102.

—. “Sonship, Liberty, and Promise-Keeping in Sense and Sensibility.” Renascence: Essays on Values in Literature 63.2 (2011), 91-109.

Originally from Newark, New Jersey (but now a proud Texan), Joyce Kerr Tarpley fell in love with Austen while traveling alone in England. “I was in my twenties, so I was close to the age of the heroine, and I found three used copies of Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, and Northanger Abbey while browsing in a London bookstore. Many years later, while pursuing a PhD in literature at the University of Dallas, what kept me going was the knowledge that I would get to write my dissertation—the first one at UD—on Austen.”

With the encouragement of one of her UD professors, the late and beloved Dr. John Alvis, Joyce queried Catholic University of America Press about publishing a book based on her dissertation. While the press made it clear they did not publish dissertations, they gave her a chance—on the recommendation of one reviewer—to revise her initial submission. Several years and many revisions later, the book, Constancy and the Ethics of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, was published.

Her other essays on Austen have appeared in Persuasions: The Journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America and Renascence: Essays on Literature and Ethics, Spirituality and Religion.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “In the Matter of Sense v. Sensibility: An Excerpt from the Upcoming Novel Austen at Sea,” is by Natalie Jenner.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Isabelle de Montolieu’s Sense and Sensibility, by Peter Sabor

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 19, 2024

Isabelle de Montolieu’s Sense and Sensibility, by Peter Sabor

Who was Isabelle de Montolieu, and why is she important to lovers of Sense and Sensibility? Born Jeanne-Isabelle-Pauline Polier de Bottens in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1751, she was twenty-four years Jane Austen’s senior.

(From Sarah: This is the tenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

This pastel portrait of about 1770 shows Isabelle de Montolieu as a young woman, shortly after her short-lived marriage to Benjamin de Crousaz, who died in 1775.

She made her reputation with Caroline de Lichtfield, ou Mémoires d’une famille prussienne, published in both Paris and London in 1786, and at once freely translated by the radical writer Thomas Holcroft as Caroline of Lichtfield. A Novel; both the French and English versions would go through many subsequent editions. In the same year, she married her second husband, the baron Louis de Montolieu. After his death in 1800, she remained a widow for over three decades, dying in Vennes, near Lausanne, in 1832 at the age of 81.

The Musée Historique Lausanne holds several portraits of her in her later years. The one here by Jacques Louis Samuel Piot was painted at the beginning of her second widowhood, when she was establishing herself as an author. Holding an opened book in one hand and a manuscript in the other, she is depicted as a woman writer at work. Her quill pen, resting in an inkwell, is ready to be used; behind the inkwell are two substantial volumes, presumably one of her own publications.

De Montolieu produced little during either of her marriages (we might speculate whether Austen would have published her novels had she accepted Harris Bigg-Wither’s proposal in December 1802), but during the last thirty years of her life she was astonishingly prolific as both an original writer and a translator of works from German and English into French.

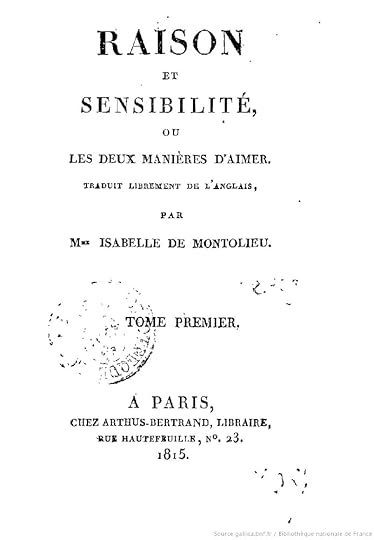

Among her translations was the first French version of Sense and Sensibility: Raison et sensibilité, ou les deux manières d’aimer (Sense and sensibility, or the two ways of loving), issued in four volumes by the Parisian publisher Claude Arthus-Bertrand in 1815. 1,000 copies were published: almost certainly a larger print run than that for the first edition of Sense and Sensibility.

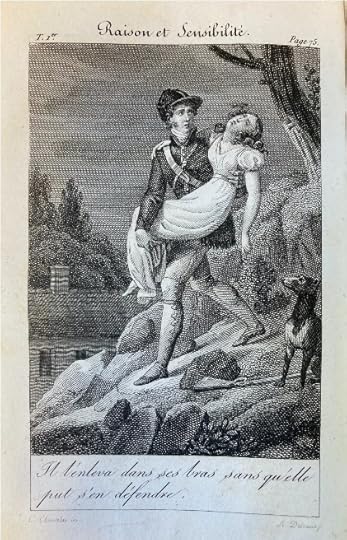

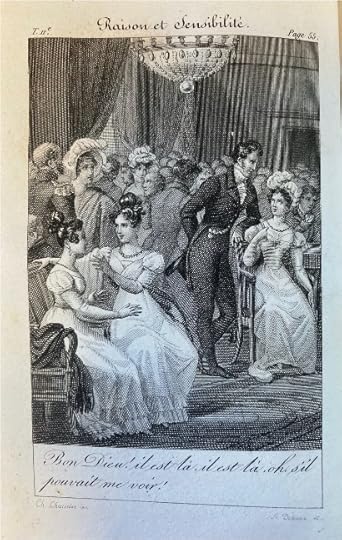

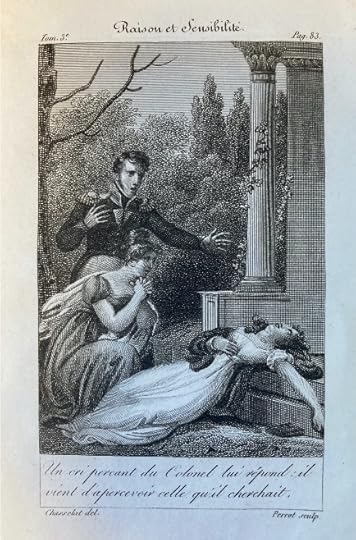

And as a further sign of the marketability of de Montolieu’s translation, in December 1827 Arthus-Bertrand published a three-volume second edition, equipped with frontispiece engravings for each volume. These engravings, designed by Charles-Abraham Chasselat and engraved by Auguste Delvaux (for volumes one and two) and Jean-Simon-Narcisse Perrot (for volume three), would have entailed a major expenditure by Arthus-Bertrand, who was evidently confident that a considerable number of readers would purchase the work. No such investment in Austen during her lifetime was shown by either of her English publishers, Thomas Egerton or John Murray, and no illustrated edition of any Austen novel in English would appear until Richard Bentley’s “standard novels” set of 1832-33.

De Montolieu’s esteem for both Austen’s novel and her own translation, expressed in a letter of 20 September 1815 to Arthus-Bertrand, is striking: “I have become attached to this work to which I have given the utmost care, and which is really very fine, and which I believe will be read with pleasure, despite the difficulty of these times” (David Gilson, A Bibliography of Jane Austen [Clarendon Press, 1985], 154). But the “care” given to Sense and Sensibility by its first translator included some substantial rewriting. For de Montolieu and her contemporaries, fidelity to the original was of little concern; instead, publishers and their chosen translators wished to turn English novels into something amenable to the taste of the French reading public. Both abridgement and expansion were commonplace. Plots were altered, often in the interest of changing the open endings favoured by Austen into something more conclusive and reassuring; French translators seem to have regarded the dull elves mocked by Austen as their principal readership. Satire and irony were generally eschewed; sentimentality and sensibility, in contrast, were highly prized. New subtitles were added (“two ways of loving”) and characters’ names were changed at will; thus Marianne and Margaret Dashwood become Maria and Emma. And the relative significance of characters can be increased or decreased. De Montolieu, for instance, had a particular fascination with Willoughby and gives him a larger role in Raison et sensibilité than the one he plays in Austen’s novel.

As an example of de Montolieu’s recasting of Sense and Sensibility, consider what she does to the unpromising Margaret Dashwood, who, Austen tells us, “was a good-humoured well-disposed girl; but as she had already imbibed a good deal of Marianne’s romance without having much of her sense, she did not, at thirteen, bid fair to equal her sisters at a more advanced period of life” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). In de Montolieu’s version, the references to Marianne’s sense and to Margaret’s shortcomings are both removed, Margaret’s name is changed, and a year is taken off her age: “Her younger sister, the young Emma, was still only a child; but at twelve years old she already promised, in a few years time, to be as beautiful and likeable as her sisters” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). Austen’s irony and satirical touches have disappeared, and Margaret/Emma is duly established as a worthy counterpart for her two admirable sisters.

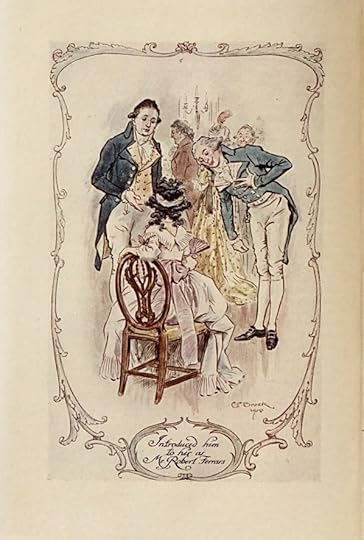

Equally striking is de Montolieu’s determination to put Marianne and Willoughby at the forefront of Raison et sensibilité, while making Elinor of no more than secondary interest and Edward of little interest at all. This is shown graphically by the three engravings chosen to illustrate the second edition of her translation.

The first depicts Marianne, with her twisted foot, in the arms of Willoughby. In Austen’s account: “The gentleman offered his services, and perceiving that her modesty declined what her situation rendered necessary, took her up in his arms without farther delay, and carried her down the hill” (Volume 1, Chapter 9). In de Montolieu’s version, the phrase “without further delay” is replaced by “sans qu’elle pût s’en défendre” (without her being able to defend herself) (Volume 1, Chapter 9), and the illustration follows suit, furnishing these words in the caption and showing Marianne in a fetching swoon: nothing so prosaic as a foot injury here.

The second illustration also makes Willoughby the dominant figure. In Sense and Sensibility, Austen gives us Marianne’s words at a fashionable party in London, when she suddenly perceives her absent suitor: “‘Good heavens!’ she exclaimed, ‘he is there—he is there—Oh! why does he not look at me? why cannot I speak to him?’” (Volume 2, Chapter 6). In the engraving, a strikingly tall and centrally placed Willoughby towers over the other figures while Elinor is placating a highly agitated Marianne, seated at the edge of the composition.

Having swooned in the first illustration and had a nervous fit in the second, Marianne has fallen into a dead faint in the third, where she is posed on the steps of a conveniently located neo-Greek temple. Elinor, looking suitably alarmed and helpless, is crouching ineffectually by her side, while a surprisingly youthful and dashing Colonel Brandon expresses his alarm in a much more dramatic manner. The scene is one of de Montolieu’s fabrications: Marianne has fainted in horror on seeing the Colonel with an attractive young woman, Madame Summers, who we subsequently discover is in fact the Eliza seduced by Willoughby (renamed Caroline here). The illustration epitomizes de Montolieu’s aims in recasting Austen’s novel. Her Colonel Brandon is a far more imposing figure than his flannel-waistcoated precursor; Elinor is a shadow of Austen’s astute and sensitive heroine; Marianne’s sensibility has been taken to a parodic extreme, akin to that of the figures populating Austen’s juvenilia; Edward, of whom de Montolieu seems to have despaired, is out of the picture; and behind everything is Willoughby, the driving force of Raison et sensibilité. He will, in de Montolieu’s version, marry Eliza/Caroline a year after the death of his wife, who had been killed after falling from her phaeton.

De Montolieu was well aware of Austen’s artistry but knew that it was alien to the taste of her readership. She devoted her utmost care to Raison et sensibilité, as she claimed. By rewriting, as well as translating, Austen’s novel, she gave her intended audience what they wanted: a version of Sense and Sensibility made palatable for French readers.

Quotations are from the Cambridge Edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited and with an introduction by Edward Copeland (2006), and from the first edition of Raison et sensibilité, ou les deux manières d’aimer (Paris: Arthus-Bertrand, 1815). Translations from the French are my own. A longer, more detailed version of this post, “Less Sense, More Sensibility: Isabelle de Montolieu’s Raison et Sensibilité,” appears in Persuasions 44 (2022), 158-70. This version appears with permission of the editor. The flower photos were taken in Quebec City by Marie Legroulx.

Peter Sabor, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, is Distinguished James McGill Professor of English at McGill University, Montreal, where he is also Director of the Burney Centre. His publications on Jane Austen include an edition of her early writings, Juvenilia (Cambridge University Press, 2006); Manuscript Works, co-edited with Linda Bree and Janet Todd (Broadview, 2013); and The Cambridge Companion to Emma (Cambridge University Press, 2015). He is also the Principal Investigator for Reading with Austen, a digital recreation of Godmersham Park Library: www.readingwithausten.com.

I took this photo of Peter (on the right) and Patrick Stokes (great-great-grandson of Jane Austen’s brother Charles Austen) at the 2017 Jane Austen Society conference in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Prodigal Sons in Sense and Sensibility,” is by Joyce Kerr Tarpley.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Landscapes of the Mind and Map in Sense and Sensibility, by Hazel Jones

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 18, 2024

“We talk also of a Laburnum”

Jane Austen died 207 years ago today, on July 18, 1817. To mark the anniversary of her death, I want to share these beautiful laburnum photos with you.

The photos were taken by Brenda Barry at the Historic Gardens in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia last month and sent to me by her sister Sandra. Sandra writes of the laburnum that “we couldn’t have timed our visit there better—it was at its height. Walking in the archway: raining sunshine. Transporting.”

Jane Austen mentions laburnum in a letter to her sister Cassandra on February 8, 1807, sent from Southampton:

Our Garden is putting in order, by a Man who bears a remarkably good Character, has a very fine complexion & asks something less than the first. The Shrubs which border the gravel walk he says are only sweetbriar & roses, & the latter of an indifferent sort—we mean to get a few of a better kind therefore, & at my own particular desire he procures us some Syringas. I could not do without a Syringa, for the sake of Cowper’s Line. —We talk also of a Laburnum. The Border under the Terrace Wall is clearing away to receive Currants and Gooseberry Bushes, & a spot is found very proper for raspberries.

In his poem The Task, William Cowper speaks of “Laburnum rich / in streaming gold; Syringa Iv’ry pure” (“A Winter Walk at Noon,” Book VI).

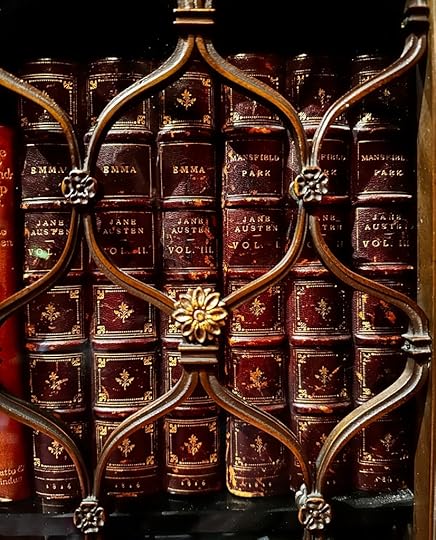

I spotted volumes by both Cowper and Austen at the Morgan Library in New York City yesterday:

I’ll be back tomorrow with the next guest post in my current blog series, “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility”: “Isabelle de Montolieu’s Sense and Sensibility,” by Peter Sabor.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.”

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Landscapes of the Mind and Map in Sense and Sensibility, by Hazel Jones

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 16, 2024

Landscapes of the Mind and Map in Sense and Sensibility, by Hazel Jones

For three years in the 1970s I lived within four miles northward of Exeter in a village on a hill overlooking the River Exe. At that time, literature degree courses focused exclusively on text, and I did not think while studying Sense and Sensibility to investigate the geographical connection between this location and the Dashwoods’ Barton, still less to map the novel’s physical and mental landscapes. That contextual interest came later, together with a wider understanding of Austen’s life and writing.

(From Sarah: This is the ninth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

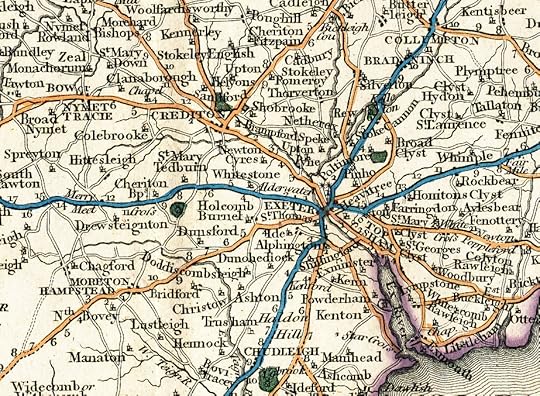

Enlarged section of Devonshire map from Cary’s New and Correct English Atlas, 1821.

The area of Devon in which Sense and Sensibility is set is and was off the main tourist trail to the seaside resorts and as such was only familiar to the local inhabitants—farmers, labourers, clergy families and landowners. A few visitors, including William Gilpin, came in search of scenery worthy of being translated into art, and left disappointed, while the Revd. John Swete, who owned property south of Exeter and applied less stringent rules to his interpretation of picturesque principles, found more to inspire his pen and paintbrush. Of the countryside to the north and west of Exeter he noted that blend of beauty and utility admired by Edward Ferrars: “it would not be very easy to point out a track of Country, in admiration of whose prospect, the Landschape Painter and the Farmer would sooner coincide” (Gray, 1999, 127) he wrote in the summer of 1797.

As is usual in Jane Austen’s novels, with the exception of Persuasion, detailed descriptions of landscape are neatly sidestepped. Of Devonshire, the reader learns that there are hills and valleys, open downs and cultivated fields, woods and pastures, fine views and dirty roads, aspects of landscape common to many counties of England. Yet the location of Barton “within four miles northward of Exeter” (Volume 1, Chapter 5) is more specific than the fictional locations in the other five novels, and the physical landscape used to greater effect in revealing mental landscapes, foreshadowing concealments and eventually facilitating openness and healing.

By the time she came to revise the manuscript of Elinor and Marianne at Chawton, she had, in the early 1800s, visited Teignmouth, Dawlish and probably Sidmouth, but the sea makes no significant appearance in Sense and Sensibility, although Dawlish is mentioned and the Dashwoods’ household possessions are transported from Sussex by sea, along the south coast of England, then up the River Exe and the new canal to the busy quay at Exeter. Sir John Middleton’s summer parties on the water happen inland, presumably on rivers and private lakes, and not even Marianne voices a longing for craggy coastal scenery. Maybe Jane Austen considered Marianne’s passion for Willoughby dangerous enough without making her wild for the sea as well. Robert Ferrars alone appears to consider the coast as a destination, and then only Dawlish. Although a fashionable destination, with smart lodging houses and a strand along which to promenade, the library there was, in Jane Austen’s opinion, “particularly pitiful & wretched” (Le Faye, 279), which made it the ideal place for these two shallow characters to exhibit themselves.

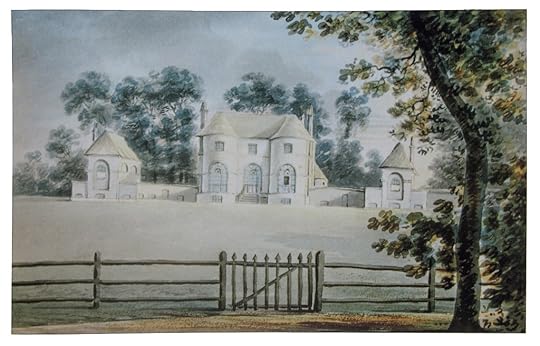

Robert Ferrars’ comments on cottages in the final version of the novel might owe something to Jane Austen’s own visit to Dawlish in 1802. It is hard to imagine his lengthy pronouncement on the luxuries of cottage drawing rooms, dining rooms, libraries and spaces for eighteen couple to dance, reproduced in a letter from one sister to the other and I suspect it was added in a later revision, when Jane Austen might have seen, on the road between Exeter and Dawlish, Mr. Lardner’s cottage. The Revd. John Swete, travelling the same road in 1796, considered this ostentatious rural retreat sufficiently picturesque to be reproduced in his travel journal.

“Cottage of Lardner Esq.” by John Swete.

Mr. Lardner’s so-called cottage would not have found a place in William Gilpin’s collection of picturesque watercolours. Using thatch as a roofing material “makes it no more a cottage, than ruffles would make a clown a gentleman,” he pronounces (Gilpin, 1798, 309). Cottages familiar to Jane Austen, John Swete, and indeed the Dashwoods in their walks through the Devon landscape, were more likely to be irregular in construction, roughly thatched and clothed in vegetation, their interiors confined, dark and damp. The building material in this part of England was predominantly cob, a mixture of clay, stones, straw, animal hair and dung. The regular appearance of Barton Cottage, together with its tiled roof, suggests that it is a brick house. With its four bedrooms, two garrets, offices and two sitting rooms it sounds as comfortable as, if somewhat smaller than, the cottage at Chawton, where, soon after the move from Southampton in 1809, Jane Austen prepared Sense and Sensibility for publication.

The reworking of the novel might have begun as early as 1801, the year Richard Buller invited the Austens to stay at his rectory at Colyton on their removal from Steventon Rectory before taking up residence in Bath. A radical adjustment in Jane Austen’s own mental landscape at this time must have proved as painful as the Dashwoods’ on the loss of a much loved home. It is to be hoped that she found some consolation in the gentle hills and valleys surrounding Buller’s rectory. Her father’s former pupil also held a perpetual curacy a few miles further west at Stoke Canon—John Swete thought the village and church of picturesque merit, describing them as “pleasing objects in the centre of the most verdant pastures” (Gray, 1999, 39)—and it is possible that Richard Buller took the Austens to Exeter and from there into the landscape “four miles northward” of the city.

Attempting to pin down exact locations has always been a compelling exercise for some readers, a number of whom have taken their research into the realms of wishful thinking, but Barton place names do proliferate in this particular region: eighteen in all. Authentic-sounding place names, together with an unerring sense of what constitutes a home, are critical elements in Austen’s fiction. In Sense and Sensibility Marianne persuades herself that the loss of Norland will break her heart, but Willoughby’s arrival at Barton is enough to reconcile her to a very different emotional and physical landscape and her previous home is all but forgotten. Both sisters shed tears on leaving Sussex, but little more is said of Elinor’s feelings of loss, beyond a regret that, unlike Marianne, she had “no companion that could make amends for what she had left behind” (Volume 1, Chapter 11). The melancholy leave-taking is counteracted almost immediately at the beginning of Chapter 6 by the Dashwood women’s first view of Barton Valley—“it gave them cheerfulness. It was a pleasant fertile spot, well wooded, and rich in pasture” (Volume 1, Chapter 6).

This is the view from the window of their carriage and other views from windows form their early impressions of the immediate landscape:

The situation of the house was good. High hills rose immediately behind, and at no great distance on each side; some of which were open downs, the others cultivated and woody. The village of Barton was chiefly on one of these hills, and formed a pleasant view from the cottage windows. The prospect in front was more extensive; it commanded the whole of the valley, and reached into the country beyond. The hills which surrounded the cottage terminated the valley in that direction; under another name, and in another course, it branched out again between two of the steepest of them. (Volume 1, Chapter 6)

Fold upon fold of the landscape is perceived through a glass clearly, while layer upon layer of secrecy and deception come to be seen through a glass darkly as the narrative unravels. What constitutes a fine or extensive prospect in terms of landscape throws into focus the significance of prospect for other characters. For John and Fanny Dashwood, Mrs. Ferrars and Lucy Steele its scope encompasses the interconnected issues of marriage, money and materiality. For Elinor and Marianne, struggling against this mercenary view of human relationships, the Barton landscape seems to promise extensive prospects, but it opens up only to close down and obscure. Among the Barton hills, and later in London, Elinor and Marianne are in effect denied an unobstructed perspective of Edward’s and Willoughby’s true motivations, a shutting out that will affect their future prospects. Neither close to, nor at a distance, can either man’s intentions be discerned. When the sisters shut themselves off from each other, their limited disclosures and concealments add an extra layer of complexity.

Beyond the windows of Barton Cottage, our first glimpse of the sisters actually in the landscape comes in Chapter 9. Marianne and Margaret venture outdoors despite the threat of bad weather and encounter Willoughby in the most dramatic of circumstances, emerging from the rain and wind to scoop Marianne into his arms. Emma Thompson makes the most of the scene in her film of 1995 by adding a thick mist. The most Jane Austen offers, on his leaving Barton Cottage is: “he then departed, to make himself still more interesting, in the midst of an heavy rain” (Volume 1, Chapter 9) but it is enough to put us a little on our guard. While Marianne questions Sir John on Willoughby’s “talents and genius,” sensible Elinor asks for more direct information: ‘“But who is he? . . . Where does he come from?”‘ (Volume 1, Chapter 9).

Apart from this first encounter and the carriage drive to Allenham, which happens off the page, scenes involving Willoughby and Marianne are always set indoors, where Willoughby’s influence leads to increasingly grave social improprieties, culminating in Marianne’s very public humiliation in London. On the day of the Whitwell picnic, rather than driving about the countryside, he heads straight for Allenham Court. This is the property he is to inherit on his cousin’s death, a house familiar to the Dashwoods only from the outside. Marianne is persuaded to penetrate this forbidden territory, thus violating Mrs. Smith’s privacy and violating too her own nature, in allowing her thoughts to take a materialistic turn, as she assesses Allenham in terms of real estate.

We never learn Willoughby’s “sentiments on picturesque beauty” (Volume 1, Chapter 10) —the countryside in Devonshire provides little more than a glorified killing ground for him—remember that he carries a gun and is accompanied by two gun dogs when we first see him. Does he prefer both to hunt and elude women in more confined spaces? The enclosed urban environment of Bath provides the location for Eliza’s seduction; London is where he tracks down a rich heiress and conceals himself from Marianne among the Bond Street shops.

One or two references to William Gilpin’s writings are relevant to an understanding of Edward Ferrars’ response to his first view of Barton valley. The description of Edward’s arrival is Gilpinesque in itself, featuring foreground, distance, prospect and animation:

Beyond the entrance of the valley, where the country, though still rich, was less wild and more open, a long stretch of the road . . . lay before them; . . . they stopped to look around them, and examine a prospect which formed the distance of their view from the cottage. . . .

Amongst the objects in the scene, they soon discovered an animated one; it was a man on horseback riding towards them. (Volume 1, Chapter 16)

Although Gilpin did not appreciate many aspects of the Devon landscape—“Its very appearance on a map, shews, in some degree, its unpicturesque form” (Gilpin, 1798, 244) he asserted—and although the golden colour of ripe cornfields disgusted him on picturesque principles, he saw, as Edward did, value in the fertile soil. He wrote of the countryside around Exeter, Colyton and Honiton, which is an extension of the landscape four miles northward of Exeter:

As the mist cleared away, and we saw more of the country around, its picturesque charms did not increase upon us. If the hills and dales, however, of which the whole country is composed, possess little of this kind of beauty, they possess what is better, the riches of soil, and cultivation in a high degree. If any valleys can be said to laugh and sing, these certainly may. Nothing can exceed either their tillage or their pasturage. (Gilpin, 1798, 272)

If Edward Ferrars’ initial assessment of Barton valley—“these bottoms must be dirty in winter” (Volume 1, Chapter 16)—is hardly of the laughing, singing variety, the reader later comprehends his negative state of mind. The influence of his engagement to Lucy Steele causes him to look down at the mud, not up at the hills. His subsequent remarks are more considered:

I call it a very fine country—the hills are steep, the woods seem full of fine timber, and the valleys look comfortable and snug—with rich meadows and several neat farmhouses scattered here and there. It exactly answers my idea of a fine country because it unites beauty with utility. (Volume 1, Chapter 18)

Far from assuming the exploitative attitude to the natural world held by the three landowning Johns—Dashwood, Middleton and Willoughby—Edward is here revealing the true landscape of his mind—his yearning for a quiet, useful, rural existence within a community of “tidy, happy villagers” (Volume 1, Chapter 18). Unlike John Dashwood, arch blighter of prospects, natural, communal and familial, Edward values a “fine prospect” (Volume 1, Chapter 18) that encompasses the promise of plenty for all who live within it.

William Gilpin’s view is not a hundred miles away from Edward’s appreciation and on this occasion it is, ironically, Marianne’s passion for “rocks and promontories, grey moss and brushwood” that is misplaced. The locations to yield such picturesque stage props are the isolated stretches of Dartmoor and places on the road along which Edward travels between Plymouth to Exeter.

“West end of Okehampton Park and Dartmoor” 1800, by John Swete.

The fertile hills and valleys of the Exe can supply no grandeur to equal these, but given Marianne’s self-delusional tendencies and love of drama, it is not surprising that she interprets the surrounding landscape in this wishful-thinking way:

. . . here is Barton valley. Look up it, and be tranquil if you can. Look at those hills! Did you ever see their equals? . . . And there, beneath that farthest hill, which rises with such grandeur, is our cottage. (Volume 1, Chapter 16)

It is wish fulfilment too that hastens Marianne’s steps towards the man on horseback on the long stretch of road, believing him to be Willoughby returning from London. Elinor, conversely, does not immediately recognise Edward because she lacks any certainty in his affection and cannot allow herself to hope. The external scene might be described as “more open”; the internal state of the characters is anything but. Off his horse, Edward demonstrates a singular lack of animation, a lowness of spirits caused by his regrettable connection with Lucy Steele, which, when the true state of affairs is eventually “decided and open”—to borrow a phrase from Emma—casts a different light on Edward’s first reaction to the Dashwoods’ proposed removal from Norland:

[Mrs. Dashwood] had great satisfaction in replying that she was going into Devonshire. —Edward turned hastily towards her . . . and in a voice of surprise and concern . . . repeated, “Devonshire! Are you, indeed, going there? So far from hence! And to what part of it?” (Volume 1, Chapter 5)

The process of illuminating the real nature of Edward’s situation happens, appropriately enough, in the open, as Lucy and Elinor walk the half mile from the Park to the Cottage. Lucy’s revelations close down Elinor’s romantic prospects as the first volume comes to an end. For the following fourteen chapters of the second volume, set primarily in London, Elinor is distanced from Marianne by the weight of this disclosure, while Marianne’s concealments have already begun, following Willoughby’s departure from Barton. The nature of the landscape stands as a metaphor for secrecy and division; the deep lanes, hills and valleys where Marianne can hide to indulge and feed her grief:

If her sisters intended to walk on the downs, she directly stole away towards the lanes; if they talked of the valley, she was as speedy in climbing the hills, and could never be found when the others set off. (Volume 1, Chapter 16)

Solitary walks in the wild areas of the grounds at Cleveland, the Palmers’ house in Somerset, “where the trees were the oldest, and the grass was the longest and wettest” (Volume 3, Chapter 6) bring on the fever that almost kills her, but recovery is gradually effected among the Devon hills. At first, on her return to Barton, the familiarity of every tree and field sparks painful recollections, but eventually the landscape becomes a place of healing where greater openness in the sisters’ relationship is nurtured. The landscape of Marianne’s mind is sufficiently altered that she is able to view more or less calmly “the important hill” behind the house where she fell and first saw Willoughby. She envisages long walks into the local landscape over the coming summer and is encouraged by Elinor to talk about past expectations and sorrows while having little faith in improved prospects for herself.

Intelligence of the new Mrs. Ferrars’ departure from the New London Inn in Exeter obliterates Elinor’s last shred of hope: “She now found, that in spite of herself, she had always admitted a hope, while Edward remained single, that something would occur to prevent his marrying Lucy” (Volume 3, Chapter 12). What Edward had felt “being within four miles of Barton” she cannot bear to determine, choosing instead to close her eyes and mind both to his prospects and her own: “she knew not what she saw, nor what she wished to see;—happy or unhappy,—nothing pleased her; she turned away her head from every sketch of him” (Volume 3, Chapter 12).

When Edward arrives in person at Barton, he comes to do away with uncertainties and establish his unquestionable identity as Elinor’s lover. The landscape serves its final purpose in providing the necessary bracing air and dry lanes for Edward to “walk himself into the proper resolution” (Volume 3, Chapter 13) to ask Elinor to marry him.

Both sisters ultimately find their happiness in the neighbouring county of Dorset, where “rather better pasturage” (Volume 3, Chapter 13) for Elinor’s cows and practicalities such as the convenient proximity of the butcher’s shop and the size of the mulberry harvest will form their concerns as married women. But it is the Devon landscape that has shaped them emotionally.

Jane Austen does not reveal whether Elinor and Marianne accept their suitors indoors or out, but, given how many of her subsequent heroes propose in the open air, let us create a pleasant prospect for ourselves where hearts and minds are opened among the enfolding hills.

A longer version of this piece appears in Persuasions Online 43.1 (2022). Reprinted here by permission of the editor. The photos at the beginning and end of this post were taken by Sarah in Washington Square and Central Park, New York City, earlier this week.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen. Gen. ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: CUP, 2005-2008.

Gilpin, William. Observations on the Western Parts of England. London: T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies, 1798.

Gray, Todd, ed. Travels in Georgian Devon: The Illustrated Journals of the Reverend John Swete (1789-1800). Tiverton: Devon Books, 1997-2000.

Le Faye, Deirdre, ed. Jane Austen’s Letters. Fourth Edition. Oxford: OUP, 2011.

Hazel Jones lectured on Jane Austen at Exeter University’s Department of Lifelong Learning and has tutored adult residential courses at various venues across the UK. She is a confirmed Jane Austen addict, having fallen in love with Henry Tilney at the age of eleven, although she has since been unfaithful to him with Mr. Darcy, Captain Wentworth, and Mr. Knightley. She is the author of Jane Austen and Marriage, Jane Austen’s Journeys, and The Other Knight Boys: Jane Austen’s Dispossessed Nephews. She is currently editor of the Jane Austen Society Annual Report.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, by Peter Sabor, is on “Isabelle de Montolieu’s Sense and Sensibility.”

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

At Home with Sense and Sensibility , by Lizzie Dunford

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 11, 2024

Jane Austen Talks to Mary Wollstonecraft: Thoughts on the Education of Marianne Dashwood, by Susan Allen Ford

From Sarah: Today is the publication date for Susan Allen Ford’s brilliant book What Jane Austen’s Characters Read (and Why). Please join me in congratulating Susan! Her book provides a new and exciting exploration of Jane Austen’s delight in “alluding to, quoting from, playing with, doing things with books.” Virginia Woolf famously said it was difficult to catch Jane Austen in the act of greatness, but with Susan as our guide, we can catch glimpses of the author’s mind at work as Austen brings her own reading into the world of her characters and builds dramatic scenes out of her engagement with other books.

It’s a great pleasure to share with you Susan’s guest post, “Jane Austen Talks to Mary Wollstonecraft: Thoughts on the Education of Marianne Dashwood.”

This is the eighth guest post in for “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!

Many years ago in a library, reading conduct books with Jane Austen in mind, I opened Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1787 Thoughts on the Education of Daughters; With Reflections on Female Conduct, in The More Important Duties of Life. Yelps of recognition threatened to get me shushed—or even ejected—as I discovered a kind of commentary on the characters and situations of Sense and Sensibility. I’d found in Wollstonecraft’s first book a companion volume to Austen’s first published novel.

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters begins with “The Nursery” and ends with “Public Places.” In between, nineteen chapters discuss moral discipline, dress, accomplishments, reading, love, matrimony, motherhood, and benevolence. As Wollstonecraft’s title suggests, there are thematic links between her conduct book and Austen’s novel. Both explore the limits and dangers of sensibility, encourage the expansion of the mind and heart, emphasize the role of reason and judgment in governing the emotions, and highlight the importance of duty to family and to God. More significant, in Marianne Dashwood’s education plot, introduced in Chapter 1 and only concluded in the final paragraphs of Sense and Sensibility, Austen illustrates Wollstonecraft’s ideas on the problems and possibilities of education. A conversation with Mary Wollstonecraft is part of the texture of Jane Austen’s first published novel.

Some readers resist the notion that Austen read Wollstonecraft (often citing her scandalous reputation). There’s no concrete evidence—no direct quotation, no mention in the novels or letters. But predating Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798), which revealed Wollstonecraft’s suicide attempts, her love affairs, and her pregnancies outside of wedlock, as well as her more radical A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Thoughts on the Education of Daughters was favorably reviewed as a thoroughly respectable (and even unsurprising) guide to female conduct. The Critical Review remarked on Wollstonecraft’s “judicious” and “correct” opinions: “The mind of the author appears to have profited by observation, and a habit of reflection: it seems both well informed, and well regulated.” The English Review commended her “good sense” and “mature[ ] reflections” on “various important situations of and incidents in the ordinary life of females,” adding that “these Thoughts [are] worthy the attention of those who are more immediately concerned in the education of young ladies.”

As further evidence of its respectability, the Lady’s Magazine published excerpts in the May, June, and July issues of 1787. The Lady’s Magazine’s influence on Austen—and particularly on Sense and Sensibility—has been documented by Edward Copeland. And it was almost ubiquitous. As Jennie Batchelor explains, “issues of the Lady’s Magazine would almost certainly have circulated among family members and were passed down through generations. They were also available for loan from the circulating libraries” (9).

So much for the accessibility. What about the connections?

Readers of Sense and Sensibility are often struck by the preponderance of spoiled children introduced, from little Harry Dashwood, whose “earnest desire of having his own way” effectively disinherits the Dashwood women, to the Middletons’ “four noisy children” (Volume 1, Chapter 7), whose introduction into the drawing room leaves no space for adult conversation. The novel’s censure, however, is directed less at the “spoilt” and “troublesome” children than at their mothers—women who have not themselves reached maturity. Wollstonecraft asks how mothers can “improve a child’s understanding, when they are scarcely out of the state of childhood themselves” (96) and adds, in a later chapter, “If she has any maternal tenderness, it is of a childish kind” (157). Austen provides enough data points in Sense and Sensibility to calculate maternal ages: Mrs. Dashwood, who has “yet to learn” how to “govern” her feelings (Volume 1, Chapter 1), is now forty; since her oldest daughter is nineteen, she apparently married at or before the age of twenty. Lady Middleton, now twenty-six or twenty-seven and whose oldest child is about six, also apparently married at nineteen or twenty. Mrs. Palmer is “several years younger than Lady Middleton” (Volume 1, Chapter 19); at the novel’s beginning, then, she is no older than twenty-one, in her first year of marriage (Volume 2, Chapter 3) and a few months away from giving birth. Wollstonecraft warns against marrying before the age of twenty: “Many are but just returned from a boarding-school, when they are placed at the head of a family, and how fit they are to manage it, I leave the judicious to judge” (96). And again, “Early marriages are, in my opinion, a stop to improvement” (93). From the evidence of these calculations, it seems that Austen agrees.

Throughout her career, Wollstonecraft is critical of the education provided to adolescents, which focuses on accomplishments, dress, and manners although to “prepare a woman to fulfil the important duties of a wife and mother, are certainly the objects that should be in view during the early period of life” (58). Although Wollstonecraft begins Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with matters of the nursery and adolescent learning, most of the work focuses on the learning that takes place while entering adulthood. The maturity that comes with experience and an openness to learning is a principal theme, and reading Sense and Sensibility through this lens emphasizes not only Marianne Dashwood’s exceptional qualities (her musicianship, for example, which Wollstonecraft would admire as “a prop to virtue” in making her “in some measure independent of the senses” [26-27]) but also her extreme youth. After all, at sixteen going on seventeen, Marianne is a bit younger than Catherine Morland—though Marianne’s talent, the breadth of her reading, and her passion for ideas might obscure that similarity.

Marianne’s extravagant language and opinions throughout the novel advertise her youthful immaturity. To some degree she reflects her mother’s mode of thinking. Just as Mrs. Dashwood tells Elinor that she “‘can feel no sentiment inferior to love’” and has “never yet known what it is to separate esteem and love” (Volume 1, Chapter 3), Marianne reacts more passionately but along the same lines to Elinor’s careful description of her feelings for Edward: “Esteem him! Like him! Cold-hearted Elinor! Oh! worse than cold-hearted! Ashamed of being otherwise” (Volume 1, Chapter 4). She speaks of the “age and infirmity” of the thirty-five-year-old Colonel Brandon (Volume 1, Chapter 8). After the revelation of Willoughby’s faithlessness, she celebrates Edward’s fidelity without recognizing the discomfort of Lucy, Edward, and Elinor (Volume 2, Chapter 13). Intriguingly, Austen’s heightening of the youthful comedy also heightens the emotional tensions of this novel.

Early on, Elinor responds to her sister’s extravagance with gentle amusement rather than disapproval. But that changes. When Colonel Brandon offers that “there is something so amiable in the prejudices of a young mind, that one is sorry to see them give way” (Volume 1, Chapter 11), we might hear Wollstonecraft’s counterargument:

The lively thoughtlessness of youth makes every young creature agreeable for the time; but when those years are flown, and sense is not substituted in the stead of vivacity, the follies of youth are acted over, and they never consider, that the things which please in their proper season, disgust out of it. (Volume 1, Chapter 4)

Elinor echoes Wollstonecraft: “There are inconveniences attending such feelings as Marianne’s, which all the charms of enthusiasm and ignorance of the world cannot atone for. Her systems have all the unfortunate tendency of setting propriety at nought” (Volume 1, Chapter 11). Marianne adopts Willoughby’s unreasonable dislike of Brandon and disregard of others. “Universal benevolence,” Wollstonecraft writes, “is the first duty, and we should be careful not to let any passion so engross our thoughts, as to prevent our practising it” (91). And, of course, Marianne also behaves in a way that might and does cause the world to perceive her as damaged.

Elinor looks forward to Marianne’s growth and experience: “A few years . . . will settle her opinions on the reasonable basis of common sense and observation” (Volume 1, Chapter 11). But Marianne does not think she needs such education. The paragraph that introduces her ends with her resistance. While Elinor knows “how to govern” her feelings, “it was a knowledge which her mother had yet to learn, and which one of her sisters had resolved never to be taught” (Volume 1, Chapter 1, my italics). At seventeen, Marianne is comically certain that her growth has stopped: “At my time of life opinions are tolerably fixed. It is not likely that I should now see or hear anything to change them” (Volume 1, Chapter 17). Wollstonecraft ties such certainties as Marianne’s to youth and a failure to exercise reason: “Hurried away by our feelings, we are apt to set those things down as general maxims, which only our partial experience gives rise to” (80-81). Sense and Sensibility consistently underscores Marianne’s youth, part of the reason for our sympathy with her: Elinor’s worries about Marianne’s relationship to Willoughby focus on a girl “so young” and “a man so little known” (Volume 2, Chapter 4).

Since Marianne Dashwood’s education is tied to her courtship plot, her opinions on love and marriage are particularly significant. Wollstonecraft is adamant (intriguingly, given her later romantic history) that sense must govern sensibility: “I am very far from thinking love irresistible, and not to be conquered. . . . A resolute endeavour will almost always overcome difficulties” (84). She is confident in the moral responsibility to recover and the ability to love again.

. . . the heart which is capable of receiving an impression at all, and can distinguish, will turn to a new object when the first is found unworthy. I am convinced it is practicable, when a respect for goodness has the first place in the mind, and notions of perfection are not affixed to constancy. Many ladies are delicately miserable, and imagine that they are lamenting the loss of a lover, when they are full of self-applause, and reflections on their own superior refinement. Painful feelings are prolonged beyond their natural course, to gratify our desire of appearing heroines, and we deceive ourselves as well as others. When any sudden stroke of fate deprives us of those we love, we may not readily get the better of the blow; but when we find we have been led astray by our passions, and that it was our own imaginations which gave the high colouring to the picture, we may be certain time will drive it out of our minds. (85-87)

That highly colored picture Wollstonecraft traces to novel reading: “It is too universal a maxim with novelists, that love is felt but once” (85). And though Austen doesn’t identify any by name, it’s clear that Marianne has been reading novels of sensibility. Not only her belief in the impossibility of second attachments but her enthusiasm for emotionally charged descriptions of landscape, her requirement that the man she will marry will display grace, spirit, fire, taste (Volume 1, Chapter 3), and her adamant assertion that “‘if there had been any real impropriety in what I did, I should have been sensible of it at the time, for we always know when we are acting wrong, and with such a conviction I could have had no pleasure’” (Volume 1, Chapter 13), all come from such novels.

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters also predicts the resolution of Marianne’s courtship plot. Marianne’s definition of what she expects in a man misses what Wollstonecraft sees as primary: “if she thinks seriously, she will chuse for a companion a man of principle; and this perhaps young people do not sufficiently attend to, or see the necessity of doing” (95). As Wollstonecraft understands, Marianne’s youth drives both her love for Willoughby and the depth of her disillusionment:

How earnestly does a mind full of sensibility look for disinterested friendship, and long to meet with good unalloyed. When fortune smiles they hug the dear delusion; but dream not that it is one. The painted cloud disappears suddenly, the scene is changed, and what an aching void is left in the heart! a void which only religion can fill up—and how few seek this internal comfort! (74-75)

Not till Marianne’s near death does she recognize her duty to think of others and her duty to God. Her “mind is awakened to reasonable exertion”; her “serious recollection” leads her to feel and acknowledge her “want of kindness to others” and the need “for atonement to my God, and to you all.” Moreover, Marianne desires to be assured that Willoughby “was not always acting a part, not always deceiving me; . . . for not only is it horrible to suspect a person, who has been what he has been to me, of such designs,—but what must it make me appear to myself?” (Volume 3, Chapter 10). Wollstonecraft anticipates the psychology of Marianne’s depression: “Perhaps a delicate mind is not susceptible of a greater degree of misery, putting guilt out of the question, than what must arise from the consciousness of loving a person whom their reason does not approve” (82-83).

Mary Wollstonecraft and Jane Austen both understand the dangers of youth and the possibility—even the probability—that women will not learn and grow. Wollstonecraft worries that early marriage, in confining women to the domestic sphere, prevents growth:

Nothing, I am sure, calls forth the faculties so much as the being obliged to struggle with the world; and this is not a woman’s province in a married state. Her sphere of action is not large, and if she is not taught to look into her own heart, how trivial are her occupations and pursuits! What little arts engross and narrow her mind! (100)

The world of Sense and Sensibility illustrates Wollstonecraft’s thesis.

What then do we make of the novel’s ending and Marianne’s transfer of affection to Brandon? In some moods, the tone of the ending has struck me (and others) as something of a betrayal of a character whose feelings are deep and in whom the reader has been encouraged to invest emotionally. But reading Sense and Sensibility after Thoughts on the Education of Daughters emphasizes Marianne’s youth, emotional extravagance, and limited perspective and highlights the ending’s comic rather than satiric edge. The conclusion underscores, almost summarizes, Wollstonecraft’s ideas.

Marianne Dashwood was born to an extraordinary fate. She was born to discover the falsehood of her own opinions, and to counteract, by her conduct, her most favourite maxims. She was born to overcome an affection formed so late in life as at seventeen, and with no sentiment superior to strong esteem and lively friendship, voluntarily to give her hand to another!—and that other, a man who had suffered no less than herself under the event of a former attachment, whom, two years before, she had considered too old to be married,—and who still sought the constitutional safe-guard of a flannel waistcoat!

But so it was. (Volume 3, Chapter 14)

Arguing for the possibility of second attachments, Wollstonecraft states, “A woman cannot reasonably be unhappy, if she is attached to a man of sense and goodness, though he may not be all she could wish” (84). Austen, however, doesn’t give us certainties in either direction.

Instead of falling a sacrifice to an irresistible passion, as once [Marianne] had fondly flattered herself with expecting,—instead of remaining even for ever with her mother, and finding her only pleasures in retirement and study, as afterwards in her more calm and sober judgment she had determined on,—she found herself at nineteen, submitting to new attachments, entering on new duties, placed in a new home, a wife, the mistress of a family, and the patroness of a village. (Volume 3, Chapter 14)

Marianne is only nineteen. Given Wollstonecraft’s caution against early marriages, what should we expect?

A longer version of this essay appears in Persuasions On-Line 43.1 (2022) as “Thoughts on the Education of Daughters in Sense and Sensibility.” It appears here by permission of the editor.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. 4th ed. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. Oxford: OUP, 2011.

—. Sense and Sensibility. Ed. Edward Copeland. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

Batchelor, Jennie. “Embroidery in Jane Austen’s Britain.” Jane Austen Embroidery: Authentic Embroidery Projects for Modern Stitchers. By Jennie Batchelor with projects by Alison Larkin. London: Pavilion, 2020. 7–13.

Copeland, Edward. Introduction. Sense and Sensibility. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. xxiii–lxv.

The Lady’s Magazine 18 (1787): 227–30, 287–88, 369–70.

Rev. of Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. Critical Review 63 (1787): 287–88.

Rev. of Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. English Review 10 (1787): 315.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. Thoughts on the Education of Daughters: With Reflections on Female Conduct, in the More Important Duties of Life. Facsimile of 1787 ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

Susan Allen Ford is Professor Emerita of English at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, and has been editor of Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line since 2006. She has published essays on Jane Austen and her contemporaries, Shakespeare, the gothic, and detective fiction. Her book, What Jane Austen’s Characters Read (and Why), is published today by Bloomsbury. Susan contributed the photos of her Mississippi garden that appear above.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post is “Landscapes of the Mind and Map in Sense and Sensibility,” by Hazel Jones.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

At Home with Sense and Sensibility, by Lizzie Dunford

Secrets and Silence in Sense and Sensibility , by Deb Barnum

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 7, 2024

At Home with Sense and Sensibility, by Lizzie Dunford

Every time I re-read Sense and Sensibility, I am struck again by its precocious brilliance. So established is Austen within the canon of the literary greats and so immeasurably vast is her influence, it is easy to forget that she was once a debut author, anxiously awaiting the public reaction to her first novel—Sense and Sensibility.

(From Sarah: This is the seventh guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

In a letter of Thursday 25th April 1811 to her sister Cassandra, Jane Austen wrote: “No indeed, I am never too busy to think of S&S. I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her sucking child.” This would not be the last reference to her books as being her offspring; in January 1813, she described the newly published Pride and Prejudice as her “darling Child” (28 January 1813)—a powerful and important reminder that the life of this famously unmarried author was anything but barren.

If to all authors their books are children, then Austen’s novels are prodigies—innovative, progressive and era-defining. As the first of her brood of prodigies Sense and Sensibility holds a special place in our understanding of both Austen the writer and Austen the woman. It also has a deep significance to the history of the home that is now Jane Austen’s House.

The first draft of what would become Sense and Sensibility belonged to the Steventon years and was part of the culmination of an apprenticeship in creative writing that had begun before Austen reached her teenage years. Later, the draft of Elinor and Marianne was part of the package of manuscripts that accompanied Austen as she moved from Steventon to Bath to Southampton to Chawton, during those peripatetic eight years that were so crucial in shaping the author who would emerge once she returned to Hampshire. It is difficult for me to be objective in assessing the significance of the move to a permanent secure home to Austen’s writing, but what is inarguable is that the Chawton years were the most productive and creative of her life. After over a decade in draft form, within eighteen months of moving to Chawton Cottage, the finished version of Sense and Sensibility was on booksellers’ shelves, with its siblings to follow in quick succession over the next six years.

Contained with the pages of Sense and Sensibility is one of the very few definite links between Austen’s lived experience and her literary creations, and it is, perhaps inevitably, connected to the home she and the women that surrounded her made in Chawton.

All of Austen’s novels are centred on the need of her young female characters to find a safe and secure home; in her contemporary context this was most easily, and most acceptably, achieved through marriage. This circumstance has all too frequently led to her books being read as pure romances (and her male leads as pure romantic heroes); a reading that misses a deep cynicism and critique of the double standards of her age. One of these double standards, and indeed double perceptions—is the imbalance between gender and the domestic. Women belong to the home, but the house belongs to men.

Nowhere in Austen’s novels is this female precarity more powerfully documented than in Sense and Sensibility. At the death of her husband, the second Mrs. Dashwood is evicted from her home to make way for her stepson and his fabulously manipulative wife. I know that I will not be alone in a series celebrating Sense and Sensibility, in championing the scene in which Mrs. Fanny Dashwood manipulates her husband into reducing his financial support for his step-family as one of the most masterful in all of English Literature (is this an opportune time to once again raise the fact that this is a debut novel?).

Norland Park might have been Mrs. Dashwood’s home, but it was never her house. In the same way, whilst Elizabeth Darcy might be mistress of Pemberley, she will never own it; that privilege will remain with her husband, and then, one assumes, her son. After their eviction the Dashwood women find refuge in a cottage provided by their generous and gregarious distant relation Sir John Middleton. Barton Cottage is in the depths of the rolling Devonshire hills; its rural and remote setting being critical to the Romantic plotline of the disastrous relationship between Marianne and Willoughby.

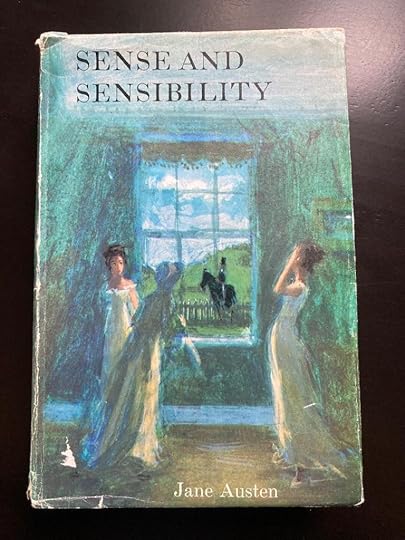

Austen had taken several holidays to Devon, and yet, when she was looking for a model for Barton Cottage, she chose much closer to home, creating in her description of the place (and it is an unusually detailed description for Austen) a portrait of the house that had become home in July 1809. Like Barton Cottage, Jane Austen’s House also has a “narrow passage . . . [leading] directly through the house into the garden behind” (Volume 1, Chapter 6). It also has two rooms, about sixteen feet square either side of this corridor, and four bedrooms and two garrets above. This description comes at the start of Chapter 6, a chapter full of a sense of both homesickness and homecoming as we see the Dashwood women arriving at and settling into the cottage.

“. . . each of them was busy in arranging their particular concerns, and endeavouring, by placing around them their books and other possessions, to form themselves a home. Marianne’s pianoforte was unpacked and properly disposed of; and Elinor’s drawings were affixed to the walls of their sitting room.” (Volume 1, Chapter 6)

For me this is one of the most poignant passages in the novel, and one that I believe offers an insight into the experiences and feelings of the Austen women during their peripatetic existence prior to moving to Chawton. It has also directly influenced how we have presented the house. Today Cassandra’s drawings hang above a pianoforte, that whilst it isn’t Jane’s, which has been lost to history, is very similar to that which she played.

This also means that today, whilst you can only visit the screen versions of Pemberley, Kellynch Hall and all the rest, you can actually visit the “real” Barton Cottage, and follow in the footsteps not just of Elinor and Marianne, but also of Austen the debut author, as she put the finishing touches to her manuscript, and then awaited its return as an actual book; the first of those precious children to be born from that special house.

Quotations are from the Macmillan Collector’s Library edition of Sense and Sensibility (2023), and the Oxford edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (3rd Edition, 1997). The photos of Jane Austen’s House are by Luke Shears and the photo of Sense and Sensibility is by Peter Smith, all included here courtesy of Jane Austen’s House.

An avid reader from a young age, Lizzie Dunford has spent her career working in and caring for writers’ houses and historic house museums. She is a dedicated exponent of the power of storytelling through objects and space and has been Director of Jane Austen’s House since 2020. She writes and presents regularly on Austen and literary houses, and can usually be found, when not at JAH, in the shed at the top of her wilderness of a garden attempting to put her own pen to paper.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post is by Susan Allen Ford: “Jane Austen Talks to Mary Wollstonecraft: Thoughts on the Education of Marianne Dashwood.”

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Secrets and Silence in Sense and Sensibility , by Deb Barnum

Mysteries of the Human Heart in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, by S.K. Rizzolo

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 5, 2024

Secrets and Silence in Sense and Sensibility, by Deb Barnum

“Come, come, let’s have no secrets among friends.”

(Volume 2, Chapter 4)

Mrs. Jennings may request “no secrets among friends,” and Marianne may “abhor all concealment” (Volume 1, Chapter 11), but Sense and Sensibility is chock full of both—many secrets, much concealed—within each character, between characters, and between the author and the reader.

(From Sarah: This is the sixth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

P.D. James, in her essay “Emma Considered as a Detective Story,” defines the detective story as one “requiring a mystery, facts which are hidden from the reader but which he or she should be able to discover by logical deduction from clues inserted in the novel with deceptive cunning but essential fairness. It is about evaluating evidence . . . it is concerned with bringing order out of disorder and restoring peace and tranquility to a world temporarily disrupted by the intrusions of alien influences.”

Such is Emma, truly a mystery, where Jane Austen gives us clues and puzzles and hints along the way, whereby we the reader can solve the underlying mystery right along with Mr. Knightley, who gets awfully close, but not quite close enough, to the solution.

But Sense and Sensibility offers no such clues to assist either the novel’s characters or the reader to any understanding of what is happening. Patricia Meyer Spacks writes: “Gradually the novel reveals that almost everyone has a secret, everyone—even characters dedicated to morality—conceals something” (“Afterword,” Sense and Sensibility [1982]). Thorell Tsomondo says: “. . . these secrets contribute to the query and puzzlement that characterizes the work” (“Imperfect Articulation: A Saving Instability in Sense and Sensibility” [Persuasions 12 (1990)]). Emma may be a mystery, but in S&S, it is all confusion, the reader not in on it. We are led to believe that Elinor is all-seeing, but indeed she often misunderstands, is wrong in her assumptions. We are presented with a Willoughby described, his true self a secret to all, as a good person, the perfect Romantic Hero (though we should have heeded the warning: “his person and air were equal to what her fancy had ever drawn for the hero of a favourite story” [Volume 1, Chapter 9])—and here Austen conceals perhaps the biggest secret of all, that it is her Colonel Brandon who is the true Romantic Hero of S&S, flannel waistcoat and all.

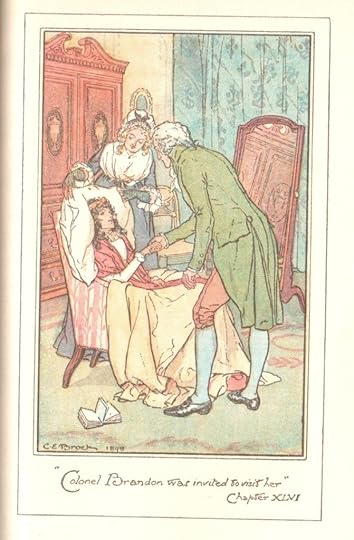

“Carried her down the hill,” C. E. Brock, S&S (courtesy of Molland’s)

Tuning into the myriad of secrets in S&S is certainly not new ground: a number of scholars have written about the issue of pervading secrecy in this novel (see references below). So these thoughts are nothing new, but I found it helpful to look at the extent of the secrecy. Indeed, the words “secret,” “secrecy,” “conceal,” “deceive,” “betray,” all appear numerous times in S&S. And more telling perhaps is the occurrence of “silent” or “silence,” certainly another aspect of secrecy—the decision not to tell, not to speak, to remain silent rather than reveal. Another word count to note is “eyes”—Austen often referring to what the eyes see when words are deceptive or untruthful, or when silence is chosen and characters rely on “the eyes” to perceive the truth: recall Elinor’s frequent reference to Lucy’s “little sharp eyes,” and Mrs. Dashwood, upon learning that her favorite Willoughby is really such a cad, remarks that “there was always a something in [his] eyes at times, which I did not like” (Volume 3, Chapter 9).

There is in S&S also an element of surprise—surprise being a secret of sorts—in the unexpected arrivals of the various heroes: Marianne declares almost verbatim on two occasions “It is he . . . I know it is!” expecting Willoughby and facing the disappointing “surprise” of Colonel Brandon and later Edward. Elinor is awaiting her mother and the Colonel and is surprised (as we all are—this feels like a Brontë novel!) when “she rushed forwards and . . . saw only Willoughby” (Volume 3, Chapter 7). (This gives short shift to a topic that needs an essay all its own!)

Secrets, of course, are a form of manipulation—and there is much of this going on as well. The story begins with a secret—on his deathbed, Henry Dashwood requests his son to help his second wife and three daughters. (Indeed the whole change in the inheritance from his Uncle to the young Dashwood boy was a secret revealed at the will-reading.) Mr. John Dashwood thought to offer a present of £1000 a-piece to each of his sisters and Mrs. Dashwood is led to believe he will take care of them in some way, “[relying] on the liberality of his intentions” (Volume 1, Chapter 3)—alas! to no avail, as Fanny Dashwood assiduously talks him out of doing anything in one of the most cringe-inducing chapters in all of literature. So the novel begins—with concealment and deception.