Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 9

August 27, 2024

Re-Reading Sense and Sensibility, by Sandra Barry

The first time I read any Jane Austen was in Grade 10 (1976-1977) at Bridgetown Regional High School, in Bridgetown, Nova Scotia. My English Literature teacher was Miss Ellen Corkum, fresh out of Teacher’s College and a favourite among the senior high students. She was a wonderful teacher, enthusiastic about literature, who encouraged us to think creatively about what we were reading. The project I did was on Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I am sure I wrote an essay, but what I remember most is spending weeks scouring magazines for images that somehow, in my view, represented the main characters. Then I created collages using the images. I remember cutting out pictures and words, arranging them on Bristol board, and meticulously lettering in the names of each character.

I suppose my essay was a kind of character analysis and the collages were a graphic complement to my words—so, a multi-media approach before I ever knew such a term. (Remember, there were no computers then, only magazines, scissors, glue and imagination.) I made collages for all the sisters, the parents and, of course, Mr. Darcy, with whom I fell in love! I remember feeling proud of my effort and I kept the collages for a long time. They are long gone now, lost in the drift of space-time. Even so, they remain vivid in my memory. I got an A. (Even the school itself is now gone, torn down, and nearby a new, state-of-the-art K-12 facility built, filled, I am sure, with computers and other wonders of modern technology.)

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-first guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

The long-term impact of this introduction was my intention to—outside any school requirement—read every Austen novel, some borrowed from the school library and some from the tiny public library in town. Eventually, I bought the Penguin paperback editions of all of Austen’s novels. (Alas, periodic culls of my library over the decades have meant that I passed on these volumes.) I do not remember when I first read Sense and Sensibility, but it was during my late teens or early twenties.

The other major impact of reading Austen was that it sent me on to the Brontës, Eliot, Dickens, James and other mid-19th century novelists. I progressed through the late-1800s until I reached an immersion in Woolf, whom I did study at university. But it all started with Austen and my fifteen-year-old self.

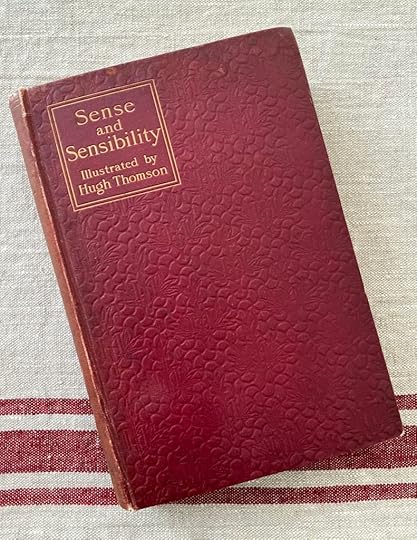

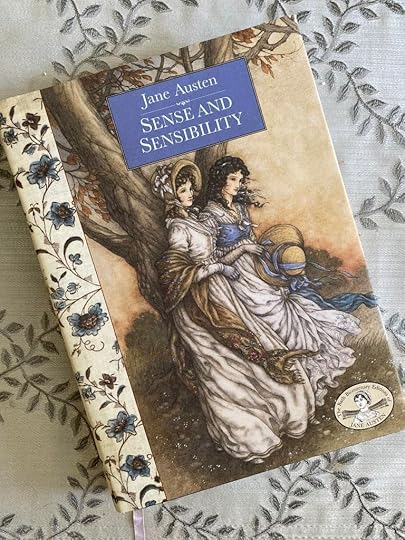

When Sarah invited me to write a guest post to help celebrate Sense and Sensibility, I was honoured and happy to agree, but it had been decades since I had read any Austen, being immersed as I have been for over thirty years in writing about the life and work of the poet Elizabeth Bishop. However, about two years ago, my sister Brenda (whose photos Sarah has shared on this blog and are in this post), also a big Austen fan, coincidentally found and bought a lovely little edition of this novel at a wonderful used bookstore in Bridgetown, Endless Shores.

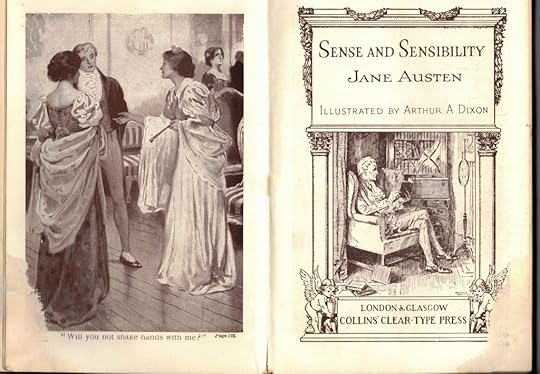

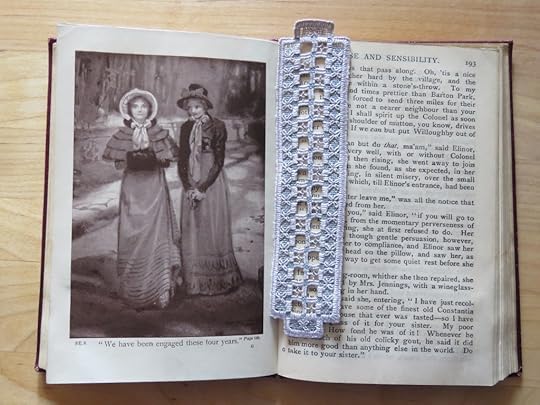

The volume is a Collins’ Clear-Type Press edition out of London and Glasgow, illustrated by Arthur A. Dixon. There is no publication date, but a rudimentary online search suggests it was published just after the turn of the 20th century, the time when Dixon was most active. It is a dear little book, only 6” x 4” with a leather cover, gold embossed words on the spine, onion skin paper and seven sepia illustrations: a lovely object to hold, just the kind of book one of Austen’s characters might hold and read in the evening in the drawing room. When Sarah invited me to contribute something, I picked it up and began to re-read it, at least four decades after first doing so.

In the interim my main Austen intake has been the movie and television adaptations of her books. I’ve lost track of how many we have watched (some better than others, and we have watched our favourite adaptations over and over again). So, it was a revelation to go back to the original words.

The primary revelation in this return was how leisurely the novel is, compared to the compression that must happen when translating to the screen. My perceptions of the characters were also challenged, so fixed have they become through the cinematic lens so ubiquitous these days.

I purposely re-read Sense and Sensibility slowly, a chapter a day, so I could ponder its quietly unfolding narrative. I could see where film-makers had lifted lines verbatim, removing them from Austen’s lush contexts. As I progressed, I tried to clear away the interpretations wrought by script writers, directors and producers. All readers bring their own sensibilities to any text (projecting, selecting, interpreting) and I wanted to let my own responses apply. And also, simply enjoy Austen’s charming, intricate, intelligent language.

Perhaps the most startling revelation for me came late, with the encounter between Elinor and the by then unhappily married Willoughby (while Marianne is still recovering). I had not remembered at all his long, self-serving explanation about his behaviour, his plea to be seen as one of the victims, his justifications which go on for pages—and Elinor’s patience and inclination, not fully conceded, to feel sorry for him. Forgive me for bringing my 21st-century sensibility to his egotistical moan: I mean, really Willoughby! It is a testament to Austen’s own keen sense of human behaviour and experience that the “happy ending” offered happens in the quietest of ways, almost as an afterthought.

I guess the question for me now is which Austen novel will I re-read next?

Sandra Barry is a poet, independent scholar and freelance editor. She is one of the founders of the Elizabeth Bishop Society of Nova Scotia and her book Elizabeth Bishop: Nova Scotia’s ‘Home-Made’ Poet was published by Nimbus in 2011. She and her sister Brenda spent last week at the Elizabeth Bishop House in Great Village, NS, where they had “time to sit for long stretches on the verandah and watch the sky and clouds and back pasture with its deer and birds.” Here’s a photo of that view, taken by Brenda:

This photo of Sandra (on the left) with Brenda and their friend Pam was taken by Greg Riley.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Sense and Sensibility Hearkens Back to Its Origins,” is by Collins Hemingway.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Writing the Musical: Sense and Sensibility, by Paul Gordon

A Song Can Sing So Much, by Lori Mulligan Davis

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 23, 2024

Writing the Musical: Sense and Sensibility, by Paul Gordon

At first, I was hesitant to write the musical of Sense and Sensibility. I had just written Emma and for the next several years I was busy with productions across the country. I wasn’t sure I had another Austen musical in me. But when Chicago Shakespeare Theatre offered to commission me to write a musical of Sense and Sensibility, I couldn’t say no, as I knew the theatre’s stellar reputation and I felt Jane Austen and I would be in good hands.

And I was right.

I suppose this would be a good time to mention that up until this point I had not read Sense and Sensibility, I had only seen the Ang Lee film (one of my all-time favorite films), so reading the novel was quite a revelation. I can’t even remember now how long it took me to complete the first draft of the show, but as soon as I started reading the book, the music came pouring out of me.

(From Sarah: This is the twentieth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

When I musicalize a novel, the most important decisions are not what to include but what not to include. With Emma, it was immediately apparent to me that I didn’t need Knightley and Emma’s brother and sister, who are a large part of the novel. They would be mentioned, of course, but I didn’t need them to appear, and the musical works quite well without them. When John Caird (Les Misérables) and I were first working on Jane Eyre for Broadway, we made the mistake of trying to “perform the novel on stage.” Then we spent the next ten years trying to fix it, and we just kept removing bits of the story until it could be performed on stage in less than three hours! But in doing so, we learned a great deal about what makes good storytelling on stage.

With Sense and Sensibility these decisions were not as clear. There was far less dialogue in the novel than Emma, and this time around I would have to write many scenes from scratch instead of lifting Jane Austen’s brilliant dialogue. And, I had the movie in my head and I couldn’t conceive of cutting any characters. But as I went deeper into the novel and started leaving the film behind, I realized that I wanted to focus entirely on Elinor and Marianne and their relationship as sisters—and so I made the painful decision to cut Mrs. Dashwood and Margaret. But that turned out to be a great decision for the stage musical.

Once my first draft was complete, we did a series of “table reads” in Chicago with just a few actors and a piano. It gave us a great sense of the shape of the show, as we continued to ask ourselves questions: Is the story clear? Is this the right song? Do we understand this relationship? How do we support the storytelling?

We were getting close to opening night when Megan McGinnis, the brilliant actor who was playing Marianne, had an idea. She felt strongly that Marianne needed a ballad in Act II. I agreed with her immediately because it resonated with me. (I love working with smart actors who understand their characters better than I do at this point in the process.)

Megan felt that a pulsating up-tempo song after Willoughby rejects Marianne for Miss Grey was not quite right and she suggested a ballad that was more reflective of the pain the character feels in the moment. She was right, and so after rehearsal I went back to my hotel room and wrote “The Swing,” which instantly became one of my favorite songs in the show.

Making theatre is such a wonderful collaborative process. So very different from what Jane Austen must have felt when she was writing Sense and Sensibility. But what I love most about this process is that I get to be on both sides of it. I’m quite isolated while I’m writing the book and the score, but as soon as I get in a room with my fellow artists, new ideas spring forth and I get to enjoy the creative vibrancy of a room full of artists.

I’m so grateful, that in my small way, I have been able to share the genius of Jane Austen with theatregoers around the country. As we celebrate her 250th birthday next year, I will continue to dedicate myself to sharing her brilliance through the magic of theatre.

Most of the photos are from the Chicago Shakespeare Theatre production of Sense and Sensibility in 2016 (plus a hydrangea photo taken by Sarah).

Paul Gordon is a Tony Award nominated composer for his musical Jane Eyre. Other works include Sense and Sensibility (winner of the 2015 Jeff Award for Best New Work), Daddy Long Legs (2009 Ovation Award, 2 Drama Desk Award nominations, Off-Broadway Alliance Award nomination and 3 Outer Critic Circle award nominations). He is the co-founder of StreamingMusicals.com, where his musicals Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Estella Scrooge, Being Earnest and No One Called Ahead can currently be streamed. (Sense and Sensibility is also available on YouTube.) Knight’s Tale, written with John Caird, has had multiple productions in Japan. His other shows include: Stellar Atmospheres, Little Dorrit, Schwab’s, Analog and Vinyl, The Front, Juliet and Romeo, Sleepy Hollow, First Night, The Circle, Ribbit, Greetings From Venice Beach and The Sportswriter. In his former life, Paul was a pop songwriter, writing several number one hits. paulgordonmusic.com

You can also find Streaming Musicals on Facebook and Instagram.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Re-Reading Sense and Sensibility,” is by Sandra Barry.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

A Song Can Sing So Much, by Lori Mulligan Davis

Of Sandwiches and Obligations, by Shawna Lemay

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 20, 2024

A Song Can Sing So Much, by Lori Mulligan Davis

Most people experience a midlife crisis, oh, in their forties? sixties? I had mine at 22, realizing I’d aged past my favorite heroines. My summer studying Shakespeare at Oxford, travel through Britain, and grad school at William and Mary were behind me. The rest of my life would be marking time. I didn’t know 22 wasn’t an age, but a year. In 2022, I was asked to be plenary speaker at my favorite Austen conference and the dramaturg for an Austen play. And not just any play! Harper College’s production of Paul Gordon’s Sense and Sensibility, a musical whose premiere I’d loved so much at Chicago Shakespeare Theater, I’d flown to San Diego to see their Old Globe remount “just one more time.”

I’m glad to say now you and I can watch the Chicago Shakespeare production anytime we choose, on the Streaming Musicals website. Whew!

(From Sarah: This is the nineteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I care, because when well done, an Austen adaptation becomes an immersive experience. My guess is Paul Gordon achieved this by approaching the show as a respectful collaboration with Jane Austen, even though by then she’d been below Winchester Cathedral for 198 years.

By adding song, Gordon neatly fits the emotional power of thirteen reading hours into an hourglass. With a skill rivaling that of the great Alan Jay Lerner, Gordon mines phrases from Sense and Sensibility that transform Elinor’s and Marianne’s grief and despair, John’s and Fanny’s greed, Sir John’s and Mrs. Jennings’s active kindness, Marianne’s flights of feeling, Marianne’s and Willoughby’s infatuation, Brandon’s longing and forbearance, Lucy’s (grammatically incorrect) crowing, Elinor’s and Edward’s resolve, Elinor’s forgiveness and release from pent-up silence, and the marrying couples’ ultimate joy into satisfying song. I alerted Chicago Shakespeare that the soundtrack needs a warning label: “Do Not Play While Driving.” I can’t help but applaud each song, even in Chicago traffic.

Here’s one to applaud: Colonel Brandon sings “Lydia,” the words a steady burst of emotion over the circumstances that devastated his life and the life of his lost beloved. It’s well worth a listen! In the streaming video, currently free, it begins at 29:14.

“Lydia” is Gordon’s name for Eliza in the novel, possibly renamed to avoid confusion with her daughter. In Austen’s day (and novels) firstborn boys or girls were often named for fathers or mothers. With neither Eliza appearing on stage, different names help the audience.

“I Hear Your Hollowed Voice”

“Each and every day,” Colonel Brandon relives Lydia’s final breath-starved farewell. The now-treatable tuberculosis was called consumption when it ravaged the 17th through 19th centuries, causing 25% of all deaths in Europe during that period and perhaps causing or contributing to Austen’s death (Brenda S. Cox, “What Killed Jane Austen?” [2021]). We now know people can safely harbor the TB bacteria (as Latent TB) inside their bodies as long as their immune system remains healthy. But if the immune system becomes compromised, Inactive TB can become Active TB weeks or even years after initial infection. Highly contagious, TB is spread by coughing, speaking, and singing. Because it can lie inactive for so long, it first was mistaken as hereditary rather than contagious. Did it orphan Lydia/Eliza? Fleeing her abusive marriage without a financial safety net, she was forced by hunger and homelessness into the poorhouse. Extreme conditions or close quarters exposed her to tuberculosis or taxed her ability to fight Latent TB. The abuses of her uncle and husband led to her death.

We were cursed right from the start

Between my father’s greed

My brother’s wrath

My misbegotten place in life.

Colonel Brandon’s father, Mr. Brandon, has a shot at being the most despicable offstage character in all of Austen.

Mr. Brandon was the trustee of his niece Lydia’s considerable fortune. As her guardian, he’d been entrusted to arrange her marriage settlements, a contract to protect her and her children. But feeling the pressure of his own debts, Mr. Brandon drafted a marriage contract solely in the groom’s favor—the loveless son he forced Lydia to marry. In the play we hear Brandon telling Elinor the story:

BRANDON

We had grown up together and loved each other from the time I can remember. But my father persuaded my elder brother to marry her. Lydia’s fortune was large and my family’s estate much encumbered.

ELINOR

From father to son. I will never cease to be surprised how easily men favor fortune over love. Was your brother at least attached to her?

BRANDON

No, he had no regard for her at all. She experienced great unhappiness. Divorce and ruin followed. I was overseas with my regiment when she was seduced by the first man to show her any kindness. By the time I could return home I found my Lydia dying of consumption, her two-year-old child by her side.

Colonel Brandon laments “antiquated customs / we’ve quite outgrown.” Those customs played into the hands of the unscrupulous Mr. Brandon, and “family is disregarded / cast out and thrown away / by senseless inconsistent laws / we still obey.” Because a wife could not own separate property (based on the husband-favoring Law of Coverture), a careful father of the bride would use the workaround of marriage settlements, legally binding financial contracts in which parents of the bride and the groom entrusted land and assets to trustees at the time of the marriage. Trustees became the legal owners of the assets, while the bride and bridegroom held beneficial ownership during life that transferred at death to “the fruit of their union” (a child or children). A bride’s father made sure the property was owned by trustees who could best protect the daughter’s and grandchildren’s interests, sometimes even if the marriage ended in divorce.

In this way, the father made sure the enticing dowry that had ensured his daughter’s marriageability would benefit her during the marriage and give her a widow’s jointure (housing bequeathed to her, specific possessions and jewelry, yearly allowance, child support for minors, etc.) if her husband died first. The contract also made sure the groom’s father would commit financially to the marriage and grandchildren. Wives in Regency England had few individual rights. The foresight of prenuptial agreements offered protection. The Lydia Bennets who decided to elope faced a lifetime without safeguards. So did someone who had Mr. Brandon negotiating both sides of the agreement.

To learn more, read Regina Jeffers’ clear explanation of marriage settlements; Mr. Brandon’s gross negligence as Lydia’s representative; and Lydia’s vulnerability under the law, as a woman, an orphan, and a minor (“Negotiating Marriage Settlements During the Regency Era” [2023]).

Colonel Brandon calls his place in life “misbegotten,” not as in “out of wedlock,” but “completely lacking in value; worthless; inspiring pity.” By law or custom, primogeniture dictated a father’s entire or primary estate be settled on the firstborn (usually a son). Entailed property was bound by legal requirements over generations. All other children had to make their own way, sometimes helped by money protected externally by the mother’s marriage settlements. In Regency England, this relegated younger sons to “the genteel occupations” (the clergy, armed forces, or law) and the daughters to the Marriage Mart.

Despite the fact that Colonel Brandon is in love with the young lady whose fortune could save the family estate, Lydia is forced to marry his brother—its heir. Colonel Brandon has joined the army, and with heroic sacrifice (which should earn him Dashing Hero Points with Marianne Dashwood), he procured an exchange to an overseas regiment to give Lydia the greatest chance to forget him. Brandon chose never to forget, but to recall her voice and face “each and every day,” long after her death. Yet, as time begins to blur the lines, another “accidental miracle” occurs in the person of Marianne Dashwood.

But Lydia there’s someone who

reminds me of you

Lydia . . .

With poetic rightness, Brandon’s lament ends with a dot-dot-dot. And the despairing lover who says “miracles are fleeting” and “life is random circumstance” tells his “departed, cherished friend” of “someone who / reminds me of you.” Marianne Dashwood shares Lydia’s “same warmth of heart, the same eagerness of fancy.” While some readers feel Marianne merely settles for the flannel-cocooned gent who aides the family, viewers of Paul Gordon’s musical applaud her choice. We’ve overheard Colonel Brandon’s heart and we hear her smile as Marianne sings, “In a moment, / There’s a sudden burst / where I finally see what I missed at first. / And the things I felt now appear reversed.”

As Marianne first sang in Act One, “Love’s a wonder.” Indeed.

Watch the musical: You can view Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s production of Paul Gordon’s musical Sense and Sensibility for free for a limited time on the Streaming Musicals website, as well as rent or buy the video via Vimeo or Amazon.

Words, words, words. That pretty much sums up Lori Mulligan Davis. A reader, writer, freelance editor, and book coach, Lori’s sure that a favorite project will ever be Brenda Cox’s Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. Though Lori has been a magazine managing editor, curriculum writer, academic-press editor, online theater reviewer, and museum educator at the Naper Settlement, this blog post proves that the Zenith of her life was speaking at the 2022 Jane Austen Summer Program on “‘I Was Quiet, But I Was Not Blind’: Sight and Silence in King Lear and Mansfield Park” and being Professor Kevin Long’s dramaturg for his production of the Paul Gordon musical Sense and Sensibility at Harper College. A former publicity director of JASNA-Greater Chicago Region, she’s current president of the Chicago region of American Christian Fiction Writers and enjoys leading writing workshops for professional writers, educators, and teens. Lori contributed the photos. She says zinnias are her favourite flower “because they seem like a bouquet within a single flower.”

Lori describes this as her “Jubilant arrival at The Old Globe Theatre, San Diego, to see Sense and Sensibility ‘one more time.’”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Writing the Musical: Sense and Sensibility,” is by Paul Gordon.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Of Sandwiches and Obligations, by Shawna Lemay

On Sense and Sensibility and Lady Susan, by Anne Giardini

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 16, 2024

Of Sandwiches and Obligations, by Shawna Lemay

We live in a time where our empathy muscles are atrophying, our ability to navigate moral and ethical concerns seems wanting in many. Myriad studies point to fiction as the most efficacious way for humans to develop empathy and refine our critical faculties. Fiction allows us to think things through, often before we encounter similar experiences in our own lives.

(From Sarah: This is the eighteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I have thought about the famous Chapter 2 of Sense and Sensibility in so many situations since reading it eons ago. The comedic timing which rapidly takes us from the resolution of John, the half-brother, giving his sisters a thousand pounds after the death of their father, to, on the advice of his wife, figuring that any gift would be “absolutely unnecessary, if not highly indecorous.”

It’s a shocking delight to trace the path whereupon John’s wife talks him down from a thousand pounds, to 500, to some unsettled amount “occasionally,” to “a present of fifty pounds now and then” to “sending them presents of fish and game, and so forth, whenever they are in season.”

Beautifully daft and absurd when in the midst of the conversation he says, “One had rather, on such occasions, do too much than too little.” And in the end, he congratulates himself on his kindness. One cannot over-praise Austen in the construction of these scenes.

One day a few weeks ago I had a shift in the inner-city library during which I interacted with houseless folks, new immigrants, among others. I’d helped some folks who were in such a bad way that they were crying, and I had some small part in sorting them out. It felt useful but also just way too insignificant. I began the walk to my car which was a ways off so I could get my parking for free. It was a fairly rough shift, honestly, as many of them will be and it’s nothing new to me—I’ve worked with this population for going on fifteen years. I was congratulating myself on the free parking as I walked, hoping my car hadn’t been ransacked, as had happened before. I was hoping I could catch a break, really, as one does. I was cutting through back alleys, and side streets. My legs were tired, and my feet hurt from being on them for six hours. All fine. It’s a blessed life and I know it, most days.

I walked by a bunch of folks perching on a cement step and they called out to me. They looked familiar. Maybe I’d seen them in the library earlier. I just wanted to get to my car several blocks away still. They wanted cash. And who carries cash these days? I called back, sorry I don’t have cash. Kept walking. Are you sure? I’m sure. Sorry. Kept walking. Can you buy us a sandwich? Kept walking. Two more steps. I stopped. Because why not? Why not? I really wanted to get home. But why not?

I look around and right there, beautiful coincidence, a convenience store. I take the one fellow with me, and he tells me his name, which I recognize. We’ve met before. At the beginning of the pandemic, I had met him on one of my very early morning city photography outings and his nickname is distinctive. Those mornings were eerie—I would usually have the downtown streets to myself along with a few houseless folks who were invariably friendly.

It’s always the hands that get me, the dirt that would take days to lift out and long soaks. I took him into the store and bought him a sandwich and a ginger ale and one for his friend, too. He wanted his heated. I got it heated. We went out. His friend thanked me, we all chatted a bit, and I carried on.

When I got to my car, I had the thought: that actually felt like the best part of the day. And it wasn’t a big deal. I’ve bought countless burgers and sandwiches and coffees for houseless folks over the years and sometimes I’ve given cash and let people have the dignity of buying their own chips and pop. It’s something they often say you shouldn’t do. I wouldn’t usually talk about this because it sounds like virtue signalling even to my ear. But you know, to heck with that. Because some days I don’t know how to get on in the world with all its misery and sorrow. And giving someone a pair of warm socks or some French fries from Dairy Queen or whathaveyou, it helps me probably more than them. I know that.

But whenever I do this, I always think about Jane Austen and Chapter 2 of Sense and Sensibility. And that piece of work, John, and his wife, an even bigger piece of work. And how if things had been just a bit different, he’d have talked himself into giving the Dashwoods some cash, and helped them find somewhere decent to live, rather than making them homeless for that bit anyway. I mean, the story would have ended right there then if he’d been a mensch.

Luckily, we see how it plays out. John is unforgiveable for always and ever. But. We are rolling down a new path.

Rumi, the 13th century Sufi mystic, said in a poem:

Don’t grieve for what doesn’t come.

Some things that don’t happen

keep disasters from happening.

In the same poem, the definition of Sufism is given as, “The feeling of joy / when sudden disappointment comes.”

And there is disappointment following the abdication of help for the Dashwood sisters and mother by their half-brother, John. But certainly, the joy is deferred until the end of the book. We won’t dwell on what would have happened if in an alternate Jane Austen reality, the Dashwoods had been treated benevolently by their brother.

Do we these days think about our obligations to one another? Perhaps not as often as we ought. In her book On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World, Danya Ruttenberg quotes an international law scholar, Louis Henken. He says that our society “focuses on rights afforded to the individual, rather than on obligations to one another. . . .”

In Lauren Berlant’s On the Inconvenience of Other People, they say that “just by existing, historically subordinated populations are deemed inconvenient to the privileged who made them so. . . .” And the sudden shift of worth and class by the Dashwoods makes them inconvenient. They have no legal rights to any money or land, and John, as we see, is easily talked down the stairs of obligation.

As the Dashwoods approach Barton Cottage, their new reduced residence, they go from “melancholy” and “dejection” to a cheerfulness in their approach. The view is of a “pleasant fertile spot, well wooded, and rich in pasture. After winding along it for more than a mile, they reached their own house” (Volume 1, Chapter 6).

In his book on contingency and Buddhist thoughts on good and evil, Stephen Batchelor talks about paths. We create a path by carving it out and “it entails both doing something and allowing something to happen. A path is both a task and a gift.”

The Dashwood sisters and Mrs. Dashwood have a new path thrust upon them. They are thrown into contingency, “if not this, then that.” And of course, their new task becomes, eventually, a gift. Their new happiness, one feels, isn’t entirely contingent on the happily ever afters that Marianne and Elinor find with Colonel Brandon and Edward Ferrars.

They have been treated without any sense of true obligation or goodness, but they have not dwelt on what is owed them but on what is. Which brings me to that beloved poem by Galway Kinnell, “Prayer,” which goes:

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

And I think that whatever might have happened along the path for Elinor and Marianne, if that had happened rather than this, well—this reader feels they would have been equal to it. They would have found some measure of joy, regardless. As luck would have it, they were helped by another connection, by relations, so their homelessness was short-lived.

Still, Austen gives us a lot to think about in terms of our obligations to one another. How easily we may be talked out of them, and what a loss to us all when we are.

Quotations are from the Oxford 3rd edition from the illustrated series The Novels of Jane Austen, edited by R.W. Chapman.

Shawna Lemay is the author of Apples on a Windowsill and other books, including the novel Everything Affects Everyone, which I wrote about here last year in a post called “Secrets that everyone knows.” She wrote “The Sponge-Cake Model of Friendship” for All Lit-Up and so, she says, it seems appropriate to follow this up (several years later) with a piece referencing sandwiches. Author photo by Robert Lemay. Sandwich photos by Shawna.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “A Song Can Sing So Much,” is by Lori Mulligan Davis.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

On Sense and Sensibility and Lady Susan, by Anne Giardini

Sense and Sensibility and Sewing, by Marilyn Smulders

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 13, 2024

On Sense and Sensibility and Lady Susan, by Anne Giardini

A strange thing happened when I opened up my old (Bantam Classics edition, January 1983) copy of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility last month. The biography of Austen inside the front cover lists Austen’s works, among them the epistolary novel Lady Susan, which is, famously, about a terrible mother. Immediately, I set Sense and Sensibility aside and picked up Lady Susan.

I so readily exchanged the confections of Sense and Sensibility for the talons of Lady Susan because another famously terrible mother, a real world one, Alice Munro, was in the news on the day I picked up Sense and Sensibility. Alice Munro, who won a Nobel Prize for literature in 2013 and who died in May of this year, was a friend of and exemplar to my mother, the writer Carol Shields, who died twenty-one years ago. My mother admired Munro’s work, as we all did, my mother, my three sisters and I. We referred to her reverentially whenever her name came up, as did others, as The Divine Alice. Now, in July 2024, Munro had been exposed to the world as having abetted and concealed sexual offences committed by Munro’s second husband, Gerald Fremlin, against her youngest daughter, Andrea, when Andrea was nine years old, and likely for a period before and after that. Faced with evidence that Fremlin had abused Andrea Munro, including Fremlin’s written admissions, Munro failed repeatedly to protect or support her daughter. Munro instead clung to her marriage to Fremlin, and even tried to shift to Andrea a portion of the blame for Fremlin’s crimes. Andrea was effectively silenced, expelled from the family, and failed over and over by adults around her who conspired to keep matters quiet. Except, that is, for a quickly dispatched criminal trial; Fremlin pled guilty; he was given a nominal sentence; everyone went on as before. Andrea did not make her situation widely known until two months after her mother’s death.

(From Sarah: This is the seventeenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I was certain I had read Lady Susan before. It is after all included in a collection of Austen’s juvenilia that I have on my bookshelves. But I had forgotten almost everything except the first chapter/letter, in which Lady Susan claims that she is going to pay her neglected daughter Frederica greater attention—by sending Frederica to a private school. This is an early, but not the first, hint in the book that Lady Susan’s stated and actual intentions do not align with each other or with what might be expected of a good mother.

The book, which was written when Austen was still in her teens, is short and tightly plotted. I finished it in one sitting, caught up in a drama in which Lady Susan is the cat and her daughter, poor, silenced, dejected, terrified, artless Frederica, is a trapped mouse left to her mother’s sharp-clawed mercies.

Bad mothers are at the centre of some of our oldest and most memorable stories. Eve raised her children in dust and pain instead of in paradise. Herodias had her daughter Salome command the head of John the Baptist. A mother, unnamed, agreed that Solomon should cut an infant into pieces. Medea slaughtered her sons. Queen Gertrude married, in haste, her husband’s murderer. Charlotte failed to protect Lolita from the predations of Humbert Humbert.

There are perfect mothers in fiction and in art as well. The saintly depictions by Dickens and Mary Cassatt come to mind. These mothers suffer from the problem of not being interesting or believable.

Normal, that is to say, inadequate, mothers are far more common, and in fact are often used by Austen as comic foils. Consider how Mrs. Bennet’s avidity to marry off her daughters in Pride and Prejudice exposes her to ridicule and disdain. Or Lady Bertram mindlessly doting on her pug in Mansfield Park.

I returned at last to Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen’s first published novel (1811), although likely her second- or third-written, to find it too makes good use of the idea of the inadequate mother, and often to comedic ends. Mothers are meant to have good sense. Mrs. Dashwood lacks good judgment and Charlotte Palmer is giddy and oblivious. Mothers are meant to be warm and loving. Fanny Dashwood, Lady Middleton and Mrs. Ferrars are lacking in affection. Mothers are meant to love all their children equally. Mrs. Jennings, Mrs. Dashwood and Mrs. Ferrars all favour their second, almost inarguably less-deserving child.

In the wake of the revelations about Munro, and the extravagant bad behaviour in the pages of Lady Susan, I found it challenging to focus on the milder failures of maternity in Sense and Sensibility. Sense and Sensibility is a comedy that ends adequately. Lady Susan is a tragedy, even if it ends well for the tender and stalwart Frederica. I reread Lady Susan, looking for and finding parallels between Frederica and Lady Susan on the one hand, and Andrea and Alice Munro on the other. As a mother, Lady Susan deprives Frederica of comfort, company, security and support. She maintains a dalliance with, and eventually marries, Sir James Martin, while at the same time trying to force Frederica, who is sixteen years old, to marry him. She is self-absorbed and secretive. She betrays her daughter’s confidences. She lies about her daughter to others. Alice Munro’s offences were real, more current, and measures worse.

Austen said of Sense and Sensibility, in a letter to her sister Cassandra dated April 25, 1811, “I am never too busy to think of S&S. I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her sucking child.”

Mothers can and do forget their children. Munro left her children behind with her first husband, Jim Munro, when Andrea was about six years old. After that, Andrea saw her mother mainly during summer holidays, time during which she strove and often failed to elicit maternal affection from her mother. Time during which crimes were committed against her.

It is impossible to know at this reach of time what Austen thought of her mother but I find it impossible to believe that their relationship was wholly satisfactory. Whatever Jane Austen thought of her own mother, her novels evidence close attention to the styles and manners of mothers in her own time, and it is a truth universally acknowledged that Austen’s writerly lens works as well in our time as in hers. As such, the novels of Jane Austen, including Lady Susan and Sense and Sensibility, provide a system for examining mothers today. My own mother reflected the good sense and equilibrium of Mrs. Weston in Emma. Yours might be more like Lady Catherine de Bourgh, in which case, may God help you. Andrea Munro drew Lady Susan.

So what is the literary chatter about Munro, who was never, after all, known to have been an excellent mother? I’ve had dozens of exchanges with friends and writers and lovers of Munro’s work (three sets that heavily overlap). Several have pointed out that it is reductive to treat these revelations as the one and only framing for Munro. To do so would be not only banal but also a denial of creativity and complexity. Others have pointed to ways in which secretiveness, blame, self-interest, and the shirking of moral responsibility are the source of so many of Munro’s stories.

There is also the fact that the bad mother is a Janus-faced trope since the attributes that subject a mother to charges that she is unfit—independence of thought, ego, ambition and the like—are also aspects of a wholly-realized self. It isn’t marriage that leads a woman to cut off her heels or toes, as Cinderella’s sisters did to try to fit into that glass (or fur) slipper, but childbirth. A good mother is expected to be selfless and abnegating. She must put her children’s interests ahead of her own. Shel Silverstein’s book, for example, The Giving Tree, is a horror story—for the tree/mother. If a “good mother” has an inner life and thoughts and desires of her own, they are expected to be set aside, or at least buried deep enough to cause no breaking of the glassy maternal and marital surface.

Munro’s work extends the margins of what we can expect of even the very best writers. She created unique and enduring worlds. It is also the case that much of her work came from the wellspring of sexual interest between men and women, and how its pursuit can drive women, and men, to behave badly. It may be the case that her kind of genius can lead to or involve or come out of hubris. None of this is an absolution or even any kind of explanation. There is no single or conclusive key to Munro’s work or life.

In the end, I concluded that Sense and Sensibility does provide a framing for my present view of Munro. It comes when Austen’s omniscient narrator reports that Marianne “felt the loss of Willoughby’s character yet more heavily than she had felt the loss of his heart.”

Anne Giardini, O.C., O.B.C., K.C., is a corporate director and writer. Her most recent publication is “Role of the Chancellor” in Conversations on Ethical Leadership: Lessons Learned from University Governance (University of Toronto Press, 2023). The flower photos were taken in Toronto in early spring.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Of Sandwiches and Obligations,” is by Shawna Lemay.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Sense and Sensibility and Sewing, by Marilyn Smulders

Reading Sense and Sensibility Through the Framework of Birth Order, by Ria Harvie

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 9, 2024

Sense and Sensibility and Sewing, by Marilyn Smulders

I did not think I could admire my favorite author more than I already did until Sarah Emsley told me that Jane Austen made quilts too. And so to celebrate, I fired up the Sense and Sensibility audiobook narrated by Rosamund Pike (Jane in the Joe Wright-directed Pride and Prejudice) and sat down at my quilt frame to stitch and delight in Austen’s story of the Dashwood sisters.

(From Sarah: This is the sixteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

The one surviving quilt that Austen worked on is a stunner, although technically not a quilt because it consists of a pieced top and a cotton back without a layer of wool or cotton batting in between. Made by Austen, her sister Cassandra and their mother, the treasured textile is stitched from more than sixty different fabrics with a large, diamond-shaped medallion in the middle. The central image of flowers in a basket is surrounded by diamond-shaped pieces of floral fabrics, cut to show off the patterns to full advantage. (In today’s quilt parlance, this is called “fussy cutting.”) The entire panel is framed by a border of diamond patches, numbering an astounding 2,500 pieces.

The quilt, or rather the “patchwork coverlet,” is dated circa 1810 and one of a few treasured examples of Austen’s needlework that are part of the collection at Jane Austen’s House in Chawton, Hampshire; others are an exquisite embroidered muslin shawl and a handkerchief embroidered in satin stitch with Cassandra’s initials, CA. In a letter written to Cassandra around that time, Austen urges her sister to find more fabrics for their queen-sized project. “Have you remembered to collect peices [sic] for the patchwork—we are at a standstill,” reminds Austen while Cassandra was staying with their brother Edward on his estate in Kent (31 May 1811). Edward’s household with its eleven children would likely have yielded a wider selection of scraps than the three women living quietly at Chawton could dream of generating with their modest dress needs.

There are a number of clues in the coverlet to tell us that Austen was as adept with a needle as she was with words. First of all, that the work survives more than two centuries after it was completed is a testament to how precious it is, obviously treated with the utmost care.

Secondly, the design is an exacting one that only an expert sewer would attempt, executed using the English paper piecing method. The individual patches of fabric were stitched to paper shapes and then hand-sewn together, with the paper removed afterwards. That the shapes were diamonds means the edges would have been cut on the bias, and thus subject to being stretched and distorted. Although I have not seen the coverlet in person, in photos it appears to be perfectly flat and straight.

Thirdly, her prowess with the needle was noted with pride by her nephew James Edward Austen some fifty years after her death.

“Her needlework both plain and ornamental was excellent, and might almost have put a sewing machine to shame,” he wrote. “She was considered especially great in satin stitch” (Memoir of Jane Austen, Chapter 5).

It is interesting that work on the coverlet coincides with the completion of the first novel Austen sent out in the world. As Lizzie Dunford notes in her post, “At Home with Sense and Sensibility,” for this series, Austen’s years at Chawton Cottage were the most “productive and creative of her life.” It appears that having a comfortable and secure place to live brought Austen’s creativity to full flower, allowing her to revise Sense and Sensibility, a manuscript she started as a teenager, and send it out to be published, with Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma soon to follow. Sewing and writing are complementary; hand sewing allows the mind to be blissfully free. Some of my best ideas are germinated while I am hand quilting or hand sewing; I expect the same was true for Austen. I can imagine her sewing patches together for the coverlet while ruminating over the novel she was working on, leaping up to her desk to jot down a perfect line or rework a passage that wasn’t quite right.

References to needlework are threaded throughout Austen’s works. Indeed, in Sense and Sensibility, a pervading image is of the Dashwood women working contentedly in their sitting room at Barton Cottage whether mending, sewing patchwork, or embroidering, and putting their work aside as someone or another—Lord John, Willoughby, Edward—barges in. It’s not a stretch to envision Jane, Cassandra, and their mother similarly occupied, working at the patchwork coverlet and chatting companionably in front of the fire at Chawton Cottage.

Most of the female characters in Sense and Sensibility are known “to be so very accomplished” (as Bingley says with wonder in Pride and Prejudice.) Elinor draws and paints; Marianne plays the pianoforte; Lucy Steele uses filigree to ingratiate herself with Lady Middleton; Charlotte Palmer embroiders; and Fanny Dashwood and Mrs. Jennings have their carpet work.

Some very memorable scenes in Sense and Sensibility feature needlework: Fanny is “sitting all alone at her carpet-work, little suspecting what is to come” when her brother Edward’s engagement to Lucy Steele is blurted out (Volume 3, Chapter 1); “violent hysterics”—and tangled wool, I dare say—ensue. And, towards the end of the novel, when Edward visits Barton Cottage and reveals that Lucy Steele has married the other Mr. Ferrars, the normally cool and collected Elinor attempts to hide her aroused feelings by keeping her eyes fixated on her sewing.

“Perhaps you do not know—you may not have heard that my brother is lately married—to the youngest—to Miss Lucy Steele.”

His words were echoed with unspeakable astonishment by all but Elinor, who sat with her head leaning over her work, in a state of agitation as made her hardly know where she was.

(Volume 3, Chapter 12)

I don’t know about you, but what sticks with me about this scene is that Elinor is going to have to tear out those stitches.

The quilt Marilyn was working on while listening to Sense and Sensibility

Marilyn Smulders enjoys sewing and quilting although she is not especially great in satin stitch. She still pinches herself about the time she stayed in one of Jane Austen’s residences near Sydney Gardens in Bath, coincidentally as the Regency Costumed Promenade sashayed by the front door. Retired as the executive director of the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia, she lives in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia with her husband Peter and two beloved pooches. Marilyn took the photos of Sense and Sensibility and her newest quilt in her tomato patch. Nicola Davison (Snickerdoodle Photography) took the photo of Marilyn with her dog Luke, below.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Reading Sense and Sensibility Through the Framework of Birth Order, by Ria Harvie

Mrs. Dashwood’s Journey of Growth in Sense and Sensibility, by Vic Sanborn

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 6, 2024

Reading Sense and Sensibility Through the Framework of Birth Order, by Ria Harvie

One of the things I noticed when reading Sense and Sensibility, and earlier in the year Pride and Prejudice, was that the siblings act very much like they are supposed to based on which sibling they are. What I mean by that is that my generation has a bunch of designated traits for each different sibling in the order of siblinghood (i.e. eldest, youngest, middle child or only child). The traits don’t fit for everyone, but generally the people in each division have the traits of that section. It also generally evens out as people get older and more mature, but for teens and young adults, it’s often easy to pick out where people rank in their families, simply based on their personalities.

(From Sarah: I’m delighted to introduce Ria’s guest post! Ria will be starting grade ten in the fall and she has just read Sense and Sensibility for the first time. This is the fifteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Eldest siblings tend to have a wide skill set. They are independent, protective, and aren’t the greatest at sharing their emotions. A lot of the elder siblings I know are the quiet ones of their friend group. They can be reckless, but in a friend group it’s often the elder sibling who is the mature one. They are always the one who is given responsibility in situations.

Middle children are the people who lead from the back. They don’t tend to expect praise or attention, and they are the type of people who are really smart and achieve a lot but might not get noticed for it. Depending on the person, they might be the type that’s always looking for someone who gives them the praise that their siblings get, or they are used to it and take praise as it comes.

Younger siblings love praise. They are often the most energetic siblings, even if they aren’t popular or extraverted (though they are still often people people). They generally are those people who don’t help out until they are asked too, but can be helpful once you ask them. They tend to be really really good at a few things. They love attention, and they are usually the least responsible, because they’ve never had to be responsible.

Only children are the most spoiled. That’s a stereotype, but it’s true that they are more likely to be the spoiled one out of the four types. They, like younger siblings, often need to be asked to help before they step in. An only child is used to attention, and they don’t crave it like younger siblings. They’re also probably either the nicest person you know, or the most annoying. They can be really bad at reading people and interacting with people, though that can vary for each person.

Jane Austen writes characters that follow these formulas. It’s something I noticed when reading Pride and Prejudice, because in that book, the main sisters all fit so easily into the categories they belong in.

Jane is the eldest sibling, and she is the shyest of the bunch. When she’s given the chance to go and get married to this hot rich dude, she’s worried about leaving her family behind. There is only one person who really knows her (Elizabeth, of course) and she talks about her emotions in a sort of shy way.

Lydia, the youngest, is the opposite of Jane. She is emotional and attention seeking all the time, she is always energetic and she’s not the best with other people’s emotions because she doesn’t exactly get that they aren’t as good at sharing as she is. She charges into a relationship without thinking about the technicalities of money or anything like that. She’s never really had to do anything for herself, she’s her mother’s favorite, and she’s very passionate about the things that she’s interested in. She is a very extreme type of younger sibling.

Mary and Kitty are middle siblings, and they are the ones who are the most forgettable. They are kind of ignored by everyone, whether that is their family, the potential suitors in the story, or the readers. We don’t really hear a lot about Kitty’s academics, but Mary is very book smart and loves studying. They both feel a bit overshadowed by their younger and older sisters. They work for attention, Kitty by acting as much like Lydia as she can, and Mary by being as smart as possible, but they are still background characters in their family.

Elizabeth is less of an overlooked member of the family, which I think can be attributed to the fact that she is super nice and funny, but also that she has accepted that she’s not as gorgeous or pure as Jane or as popular as Lydia, and she is okay with that. She tends to be very supportive of Jane, at least, and if she’s not supportive of her other siblings for most of the book it’s because she finds them young and annoying. She very much “leads from the back” throughout the entire Lydia situation at the end, and supports her siblings during the whole endeavor, and Lydia afterwards, even though she doesn’t agree with what she did.

I’d also like to mention Mr. Darcy, who acts like an only child but sometimes an elder sibling, which seeing as he is twelve years Georgiana’s elder makes a lot of sense. He is spoiled and shy and doesn’t know how to interact with people. But he’s also really responsible and capable.

In Sense and Sensibility there are three sisters: Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret.

Elinor is the eldest, and she is independent and responsible. She is even more wary about talking about her feelings than Jane. She doesn’t say stuff unless there is a point; she shares her opinions but listens to others’ too. She thinks about things like money and property when she gets a chance at marriage. Pretty typical eldest.

Marianne, though, I don’t think really fits. See, she is the middle sibling. Elinor is 19, Marianne is 17, and Margaret is 13. But Marianne very much acts like a younger sibling. She loves attention, she’s irresponsible, she loves praise and flattery, she’s extroverted. She’s emotional (she’s the ‘Sensibility’ in the title). When she falls in love she wants to get married immediately, even though there are so many problems that would come with marrying Willoughby, and when he breaks her heart she bawls about it for a month. She, like Lydia, seems to be on the extreme side of younger siblings.

Except that she’s not. She’s the middle sister. Which was extremely frustrating to me, because it’s not just her character that makes her seem like a younger sibling, in the narrative, she is, for all intents and purposes, the youngest. One of two. Margaret, the actual youngest, has no importance in the plot. She’s not there for 90% of the story, and when she is there she doesn’t bring any importance to the scenes. There have been many moments where I’ve wondered why Margaret is there at all.

Margaret has already been discussed this year by Finola Austin in the article titled “What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility With Fresh Eyes”, so I won’t go further into her character, but I do wonder what the story would be like, if Marianne acted more like a middle sister, like Elizabeth. Would she have wanted to marry Willoughby so suddenly and without thought? Would she have spent those months pining about him before deciding that it wasn’t worth it? Would the relationship between her and Willoughby even have existed, or would it have been like Elizabeth’s attraction to George Wickham? Would Colonel Brandon have told her first about the scandal with Eliza? Would she have been able to get out of the relationship without heartbreak the way that Elizabeth did?

I think that the novel would have been very different, had Marianne behaved like a middle child.

Ria Harvie is from Halifax, Nova Scotia and will be starting grade ten in the fall. In her free time she enjoys reading and writing, and she’s interested in history and literature. She sent me the sunset photos, from Kincardine, Lake Huron. I took the picture of the bouquet of flowers (above), a recent present from my friends Abby and Melanie.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Sense and Sensibility and Sewing,” is by Marilyn Smulders.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Mrs. Dashwood’s Journey of Growth in Sense and Sensibility, by Vic Sanborn

Time to Deliberate and Judge Edward Ferrars, by Deborah Knuth Klenck

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 2, 2024

Mrs. Dashwood’s Journey of Growth in Sense and Sensibility, by Vic Sanborn

Inquiring readers: This article focuses on Mrs. Henry Dashwood (Mrs. D), Mr. Dashwood’s second wife. She is one of Austen’s most likable mothers—a loving, caring woman, with the complex personality shared by most of Austen’s characters. Mrs. D’s priority is always her three girls. After enjoying a loving marriage, she is challenged to navigate a new life under reduced circumstances. This post examines Mrs. D’s journey as a widow.

(From Sarah: This is the fourteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

After Mr. Dashwood’s funeral, his women are in deep mourning. Mrs. D and her middle daughter, Marianne, are engrossed in the violence of their grief. Nineteen-year-old Elinor is more restrained. When John, Mr. Dashwood’s son from his first marriage, and his wife Fanny arrive to lay claim to Norland Park, Elinor keeps her distress to herself. She encourages her overwrought mother to endure a similar forbearance when dining with them.

Fanny’s brother, Edward, soon visits Norland Park. Despite his unprepossessing looks and relative shyness, Mrs. D notices that Elinor has taken a fancy to him. Her overly optimistic nature predicts that “In a few months, my dear Marianne . . . Elinor will in all probability be settled for life. We shall miss her, but she will be happy” (Volume 1, Chapter 3). Marianne eagerly agrees with her mother.

Fanny, uneasy about her brother’s attraction to Elinor, slyly informs Mrs. D that her mother (Mrs. Ferrars) expects Edward to marry well. Mrs. D, relegated to the status of visitor in the house she once ran, takes instant umbrage. “She gave . . . an answer which marked her contempt . . . resolving that, whatever might be the inconvenience or expense of so sudden a removal [from Norland Park], her beloved Elinor should not be exposed another week to such insinuations” (Volume 1, Chapter 4). After a six-month stay in her former home, the length of which she suffered only for her daughters’ sakes, Mrs. D accepts the offer of a cottage in Devonshire from her distant cousin, Sir John Middleton. The decision makes sense considering their reduced circumstances, since Barton Cottage comes fully furnished and at an affordable cost.

This decision did not come easily. Elinor, who keeps the books, needed to school her mother in finances. Mrs. D, still expecting some largesse from her stepson because of her husband’s wishes, first looked for lodgings in Sussex, where housing costs were prohibitive. John at first wanted to provide for his stepmother and half sisters, but was blocked by a resolute Fanny. Mrs. D realized that her stepson’s “assistance extended no farther than their maintenance for six months at Norland” (Volume 1, Chapter 5). The sum total of her inheritance is £10,000, which translates to £500 per annum, and is just enough for the family and three servants to live on. To her credit, Mrs. D accepts her financial situation with good grace.

Mrs. D views her new dwelling with equanimity, and states: “we will make ourselves tolerably comfortable” (Volume 1, Chapter 5). She judges that the few possessions she brought of the household linen, plate, and china, and Marianne’s large pianoforte are just enough. Plans are in the works, however, for more improvements, in some distant future.

Sir John, his lady, and mother-in-law, Mrs. Jennings, live in Barton Park, only a half mile from the cottage. Both Sir John and Mrs. Jennings, a coarse woman, are lively and kind. Mrs. D’s and Elinor’s gracious manners with their hosts are in stark contrast to Marianne’s, who disapproves of the hosts’ intrusive jollity and prefers to play the pianoforte away from their company.

The three men interested in Mrs. D’s two eldest daughters are strikingly different, and she adjusts her expectations for each accordingly. Colonel Brandon, Sir John’s friend, is silently struck by Marianne’s beauty and talent. Only five years younger than Mrs. D, he is as kind-hearted and resolute as she, and genuinely enjoys her company.

John Willoughby, who carries Marianne to Barton Cottage after she twists her ankle, meets Mrs. D, who instantly adores his looks and elegant manners. Mother and daughter are equally enchanted by his charms and mirror each other’s excitement, although Elinor senses that Willoughby is a bit false and forward—hints missed by her mother and sister.

Edward then visits the cottage unexpectedly, reactivating Mrs. D’s expectation that her two daughters would soon be married. Unbeknownst to her, both he and Willoughby are keeping secrets that would devastate the two sisters—and herself—if known. When Willoughby abruptly leaves Barton Cottage without plans to revisit the area, and after witnessing Marianne’s anguish at his leaving, Mrs. D, not knowing of Elinor’s own suffering after learning of Edward’s secret engagement to Lucy Steele, encourages the girls to accept Mrs. Jennings’ kind invitation for a stay in London.

Mrs. D then temporarily disappears from the story as Austen’s plot centers on the two oldest girls.

After Marianne learns of Willoughby’s engagement to an heiress at a ball in London, her visit turns into a nightmare. She becomes so emotionally distraught that a change of venue from that city to Cleveland, an estate in Somerset, is recommended. Marianne’s extreme misery leaves her ill and feverish. A concerned Elinor fears for her life, and writes an urgent letter to her mother.

Informed of Marianne’s alarming condition, Mrs. D plans to go to her as soon as possible (Volume 3, Chapter 9), but a worried Colonel Brandon, wishing to be of some use, fetches her in the night and brings her to her girls by early morning. During their carriage ride, he confesses his love for her daughter, which brings her joy in a time of uncertainty. Once with her daughter, Mrs. D’s calm demeanor soothes Marianne, which helps her to slowly recuperate.

Shortly after their return to Barton Cottage, the family mistakenly learns of Edward Ferrars’ marriage to Lucy Steele. Mrs. D then notices Elinor’s silent suffering, and realizes that she has taken her eldest daughter’s stoicism for granted. “She found that she had been misled by the careful, the considerate attention of her daughter,” and feared that “she had been unjust, inattentive, nay, almost unkind, to her Elinor,” who might be “suffering almost as much, certainly with less self-provocation, and greater fortitude [than Marianne]” (Volume 3, Chapter 11). This revelation strikes her to her very core and opens her eyes.

In less than two years and after honest self-reflection, Mrs. D’s acceptance of her circumstances helps to reduce her unrealistic expectations. She respects her daughters’ dissimilar choices for a husband. Then, at the novel’s end, Austen grants Mrs. D all she hopes for. “Mrs. Dashwood was prudent enough to remain at the cottage, without attempting a removal to Delaford [Colonel Brandon’s estate]. … Between Barton and Delaford, there was that constant communication which strong family affection would naturally dictate” (Volume 3, Chapter 14).

Quotations are from the Project Gutenberg edition of Sense and Sensibility.

About Vic (Victoire) Sanborn: Vic writes, “I was nine years old when my family emigrated from The Netherlands to the United States. In a defunct Twitter account, I presented myself as a Dutch character in a Jane Austen novel. That phrase describes me to a tee—a bit cheeky but reverential towards Austen’s awesome talent. My lovely mother gave me Pride and Prejudice when I was fourteen, and I have been an Austen fan ever since. I created the Jane Austen’s World blog in 2008, and haven’t looked back. Today, two talented authors, Brenda Cox and Rachel Dodge, help to keep the blog fresh and new.” Vic sent the photo of daylilies, which, she says, “are in full bloom in Maryland from June through August.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Reading Sense and Sensibility Through the Framework of Birth Order,” is by Ria Harvie.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Time to Deliberate and Judge Edward Ferrars, by Deborah Knuth Klenck

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 30, 2024

Time to Deliberate and Judge Edward Ferrars, by Deborah Knuth Klenck

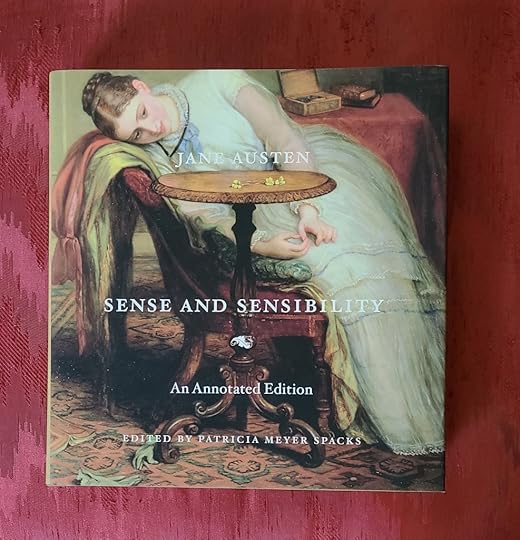

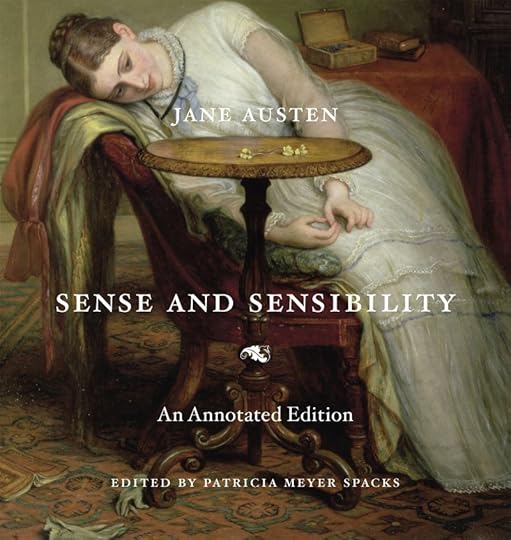

I have long thought that Edward Ferrars doesn’t get enough credit: he is adjudged by many students, critics, readers, and Jane Austen fans (in various groups on Facebook, for example) to be a rather flat character—even boring. Over thirty years ago, when Patricia Meyer Spacks was working on her book Boredom (1995), she visited my campus and met with a small group of faculty from area universities to discuss Sense and Sensibility. The consensus seemed to be that Edward was not only “boring,” but “depressed.” At the time (when I was outranked by everyone in the room), I was reluctant to wade into that controversy as a lone voice. The discussion, before consensus was reached, reminded me of the arguments students in my Jane Austen seminar had each year about whether the spirited, but wicked Henry Crawford could be redeemed at the end of Mansfield Park to become an appropriate suitor for Fanny Price. (Sometimes these debates verged on bloodshed.) I’m sure that my present audience will listen more politely.

[Of all of Austen’s works, Sense and Sensibility must have been of particular importance to Professor Spacks (who had been on my dissertation committee at Yale—another reason I didn’t speak up). Years after Boredom and our talk in Central New York, when the Belknap Press at Harvard was planning an elaborate collection of “Annotated Editions” of the novels, Spacks chose Sense and Sensibility for herself. It’s a handsome and comprehensive volume, with copious illustrations and detailed annotations. In Professor Spacks’s introductory essay, she makes clear that her opinion has not changed. Edward, she writes, is ”idle and depressed” (2013).]

(From Sarah: This is the thirteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Of course, even Edward belittles himself in hyperbolical terms as “an idle, helpless being” (Volume 1, Chapter 19). And I’ll concede that when he arrives at Norland in Volume 1, Chapter 3, his description’s underwhelming terms hardly seem to bode well:

Edward Ferrars was not recommended to [the Dashwoods’] good opinion by any peculiar graces of person or address. He was not handsome, and his manners required intimacy to make them pleasing.

These negatives go on, through “too diffident” and “neither nor” phrasing, about his family’s expectations for his future. The narrator may not give a flattering picture of Edward at this moment, but he seems more appealing when he is described as resisting the Ferrars family’s plans for him. Their vague (but always pretentious) expectations are “to see him distinguished—as—they hardly knew what,” listing such unlikely callings as entering parliament or at least becoming somehow “connected with some of the great men of the day.” The judgmental tone of this summary of the plans Edward’s sister Mrs. John Dashwood and his mother, the redoubtable, rich, and powerful Mrs. Ferrars, have for Edward should send the reader back to his introduction at Norland, so she can reconsider all those “nots” (including “not promising”) that describe him. Judging Edward has already become complicated, and Mrs. Dashwood’s initial appreciation of Edward as “quiet and unobtrusive” suddenly seems more significant (Volume 1, Chapter 3). In Volume 1, Chapter 17, Elinor warns against taking up “’a total misapprehension of [someone’s] character . . . fancying people so much more gay or grave, or ingenious or stupid than they really are,’” a danger that may be avoided by “’giving oneself time to deliberate and judge,’” advice that would be good for the reader as well as for impulsive Marianne and her sentimental mother.

[A little digression here: the independence of the widowed Mrs. Ferrars in controlling the family fortune means that she and her daughter, according to the narrator, can always transfer their ambitions (those ambitions for “they hardly knew what”) from Edward to his “more promising” younger brother Robert. By now, we know how to recast the ironic hints about the qualities that mark a man as “promising”; it makes us look forward to Robert’s appearance in the novel, to see how Austen illustrates his “promise”: then we can fully appreciate his qualifications for promotion to the role of eldest son and heir. The narrator certainly makes the most of the little scene where Robert keeps Elinor waiting at Gray’s, the London jewelers. If a career in tooth-pick-case design is one of the Ferrars family’s hopes for him, Robert is the ideal candidate, adept as he is at identifying “all the different horrors of the [ready-made] tooth-pick cases presented to his inspection” at Gray’s. (I suspect that none of the three pictured here would satisfy his exacting standards.)

Austen’s sarcasm is devastating: once Robert has chosen the ivory, gold, and pearls that will adorn his bespoke tooth-pick case, the narrator tells us, he “named the last day on which his existence could be continued without the possession of the toothpick-case,” before leaving the shop (Volume 2, Chapter 11): a “more promising” brother for Edward indeed!]

Marianne uses characteristic hyperbole to describe Edward as a “‘spiritless’” and “‘tame’” reader of poetry, “‘who [has] no taste for drawing’”; and whose eyes lack “‘that spirit, that fire, which at once announce virtue and intelligence.’” But we need to keep in mind the humble Edward of the “nots” and aim for a subtler judgment about him, closer to Elinor’s carefully qualified adverbs: “‘At first sight, his address is certainly not striking; and his person can hardly be called handsome’” (Volume 1, Chapters 3 and 4).

When he arrives at Barton Cottage, coming straight from a visit to Lucy Steele at Longstaple, Edward is obviously “not in spirits”; Elinor is mortified by his “coldness and reserve,” which are only much later to be explained by Edward’s unhappiness in his secret engagement to Lucy (Volume 1, Chapter 17). But the warmth of Mrs. Dashwood’s motherly conversation thaws Edward out, and after dinner, collected around the fire, the family has a cozy conversation, albeit about money. And here we see Edward in a meaningful relationship—not with Elinor, but with Marianne. Edward can be surprisingly sprightly with Marianne, engaging in several gentle satirical attacks on her tastes. For example, considering how the Dashwoods would spend a hypothetical surprise inheritance (a “‘large fortune apiece,’” enthuses Margaret), he predicts how the family would spend their money—on music, prints, “‘[a]nd books!—Thomson, Cowper, Scott—[Marianne would buy these poets’ works] over and over again; . . . and she would have every book that tells her how to admire an old twisted tree.’”

In mock apology to Marianne, he pleads, “’Forgive me, if I am very saucy. But I was willing to shew you that I had not forgot our old disputes.’” (Marianne, all of sixteen years old, replies, “‘I love to be reminded of the past, Edward,’” adding, to the reader’s amusement, “‘At my time of life opinions are tolerably fixed.’”) Edward’s recollection of their “‘old disputes’” makes clear that his relationship to Elinor’s sister during his visit at Norland was quite friendly, with a familiar rhythm of teasing jokes. When he and Elinor discuss Marianne’s temperament, Edward insists, “‘I have always set her down as a lively girl’” (Volume 1, Chapter 17).

An aspect of the conversation about money is a debate about how much annual income constitutes a “competence” and how much more constitutes “wealth.” Marianne insists that two-thousand-a year “‘is a very moderate income. . . . A family cannot be maintained on a smaller. . . . A proper establishment of servants, a carriage, perhaps two, and hunters, cannot be supported on less.’” Edward protests that “‘[e]very body does not hunt’” (Volume 1, Chapter 17). Even when momentarily disconcerted by questions about his ring with (presumably) Elinor’s hair, Edward can promptly return to the role of the affectionate, joking brother. When the hospitable Sir John brings up the name of the absent Willoughby and Edward sees Marianne’s blush, he whispers to her, “‘I have been guessing. Shall I tell you my guess? . . . I guess that Mr. Willoughby hunts’” (Volume 1, Chapter 18).