In the Matter of Sense v. Sensibility: An Excerpt from the Upcoming Novel Austen at Sea, by Natalie Jenner

Book Two, Chapter Nine

Sense and Sensibility

~

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

June 20, 1865

With William Stevenson in need of distraction and Thomas Nash suddenly gone, the five remaining justices agreed to hasten their next literary discussion. When asked to select the book, William, not surprisingly, chose Sense and Sensibility. With its portrayal of two very different sisters, one all head, the other all heart, Austen’s first published novel had always moved him indescribably.

“The plot commences with the loss of a beloved parent” was how William opened that evening’s discussion, voicing his usual preoccupation with death. “The oldest son now inherits the entirety of his father’s estate under the British law of primogeniture, leaving the Dashwood women rudderless, homeless, vulnerable.”

(From Sarah: This is the first-ever peek at Natalie’s new novel, Austen at Sea , which will be published in 2025! It’s also the twelfth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Justice Conor Langstaff was first to respond. He had missed the group’s last two meetings to assist at home with the arrival of twin daughters; he was also the most liberal-minded on the court when it came to women’s rights. “The legal principle of primogeniture is rooted in monarchy—the less divided up the land, the less people who own it, the less threat there is to a king. But that is of no concern in our democracy. Look at our state’s recent legislation on married women’s property rights: if anyone should be allowed to retain their earnings, make a will and likewise inherit—and keep all of that safe from a husband—it should be women.”

“Hear, hear.” To everyone’s surprise, Justice Philip Mackenzie banged his unlit pipe against the Philadelphia edition of Sense and Sensibility in his lap. One never knew where Mackenzie would land on an issue of law, but his antipathy toward their former colonizer often held the greatest sway. “I am reminded of Lord Hardwicke’s Act for the Better Preventing of Clandestine Marriage, which was largely motivated by fear of stolen fortune when young lovers run off together. Again, a sheer matter of property and intrusion by the state.”

“That legislation also gave the Church of England the right to perform all marriages in the land,” Justice Langstaff reminded the others. “Fortunately, this was undone by England’s subsequent marriage act of 1823. No nation can ignore the plurality of faiths today—even sea captains can conduct the ceremony.”

“Careful, Langstaff, don’t add to poor William’s concerns over his girls!” Justice Mackenzie warned with a laugh, causing Stevenson to redden from recognition. “Besides, there is some judicial argument against the legitimacy of marriages at sea.”

“What I find interesting about the book,” boomed Justice Roderick Norton, emphasizing this last word in an effort to redirect course, “are the number of uninterrupted, highly rhetorical speeches it contains. Pages and pages of sanctimonious dribble—when I’d be happy never to know the workings of a mind like Willoughby’s.”

“I think Austen wrote the earliest drafts as a series of letters sent back and forth amongst the characters.” At these words, the other men turned to face Justice Langstaff in both surprise and appreciation. They were each expert at locating the one most salient and significant fact in a sea of information. Langstaff could do something more, however: he could make an imaginative leap.

“I call your attention to Chapter Fifteen as evidence.” Langstaff flipped through the book to the scene where Mrs. Dashwood defends not pressing middle child Marianne on her relationship with John Willoughby, an increasingly suspect young man. “The mother’s responses to her eldest daughter’s worries over the relationship demonstrate the uninterrupted musings of someone with a captive audience and weak mind. In real conversation, she would never be allowed to proceed so far, and without interruption, by someone as rational as Elinor.”

“I posit, then, that this is Austen’s law novel,” Chief Justice Adam Fulbright declared, holding up his worn copy of Sense and Sensibility.

“How so?” asked Justice Ezekiel Peabody, always intrigued by anything to do with their profession.

“It’s about language,” the chief justice answered. “How we wield it, suppress it, indulge in it. Marianne relies on language to judge others—the unassuming Edward Ferrars for how poorly he reads poetry, the dastardly Willoughby for how well. The mother accepts as truth whatever Marianne is willing to tell her, and whatever Willoughby pleads, regardless of the evidence before her. Language is always at its most powerful when we use it to distort the perceptions of others and anticipate any retort.”

Justice Stevenson leaned forward in his seat. “Meanwhile, admirable characters such as Elinor and Colonel Brandon show their care and devotion, rather than shout it.”

“‘Actions speak louder than words,’ as the British Parliamentarian John Pym once said,” quoted Ezekiel Peabody.

The chief justice vigorously agreed. “I’m not sure I trust a man who rallies on so about his own good deeds—or lack thereof. I recall that most disturbing scene when Willoughby attempts to visit Marianne on her sick bed. He is not really there to apologize, I think. He is there to argue his case ad nauseam, confident in his right to speak without any checks on him at all. How he excuses—rationalizes—demurs! Willoughby’s chief aim, surely, is to restore the Dashwood women’s good opinion of him—he is using language purely as a tool for power and influence, not for understanding.”

“That would explain why the scene left such distaste in my mouth.” Justice Mackenzie made a sour face. “I wanted a good rinse after.”

The other men all laughed.

“And yet. . .” Everyone turned to face Justice Langstaff again. “Austen indulges, too, in that scene. She gives Willoughby a large forum, far larger than necessary. I wonder if she included the reader in that arena—wanted us also to feel something for him, in the way that Elinor begrudgingly, but eventually, does. He is surely despicable, based on the facts of his behavior, and no amount of affection to or from Marianne should change that. And yet.”

The room fell silent at this thought, a most disturbing one, that even Jane Austen, once in a while, lost control of her court.

Excerpt from AUSTEN AT SEA.

Copyright © 2025 by Natalie Jenner. All rights reserved.

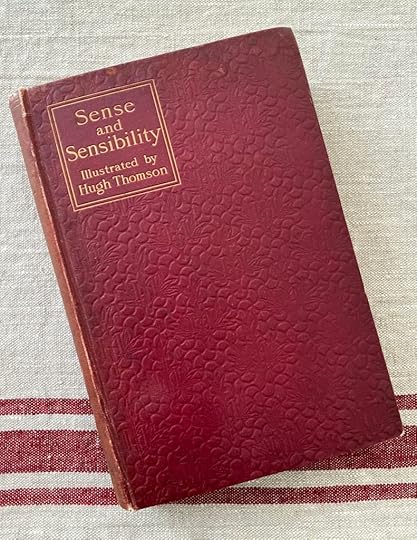

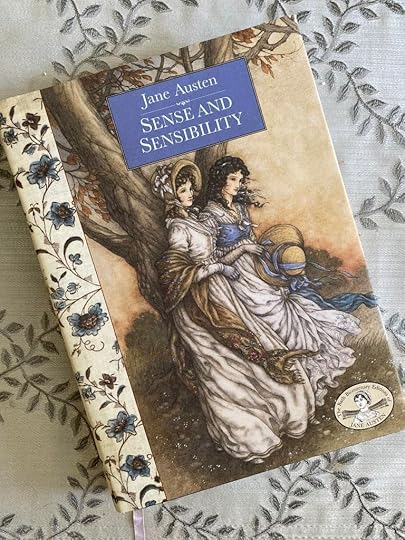

Natalie Jenner is the internationally bestselling author of The Jane Austen Society, Bloomsbury Girls, and Every Time We Say Goodbye, which have been translated into more than twenty languages worldwide. Her fourth novel, Austen at Sea, releases from St. Martin’s Press in May 2025. Formerly a lawyer, career coach, and independent bookshop owner, Natalie lives in Oakville, Ontario, with her family and two rescue dogs. The first photo is of her garden earlier this month, the second was taken in Canada’s Royal Botanical Gardens in June, and she also sent photos of her 1896 Macmillan edition of S&S and a favourite recent illustrated edition.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Time to Deliberate and Judge Edward Ferrars,” is by Deborah Knuth Klenck.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Prodigal Sons in Sense and Sensibility, by Joyce Kerr Tarpley

Isabelle de Montolieu’s Sense and Sensibility, by Peter Sabor

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.