Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 6

December 4, 2024

Christmas on the Grand Parade

All are welcome at Christmas on the Grand Parade, an annual concert at St. Paul’s Church, Halifax, with Christmas carols and readings. This year, the concert will be held on December 16th, which is Jane Austen’s 249th birthday, and I think attending will be a fabulous way to celebrate this occasion as well as the Christmas season. As I’ve mentioned here before, one of Jane Austen’s nieces was baptized at St. Paul’s, in 1809, and one of her nephews was married there, in 1848.

The concert is on Monday, December 16th at 7pm. St. Paul’s is located in the Grand Parade in downtown Halifax, Nova Scotia, across from City Hall, at 1749 Argyle St. Admission is free; there will be a free-will offering to support Phoenix, which offers services and programs for youth ages 11–24 and their families. Hope to see you there!

Performers include the St. Paul’s choir, the Bedford Brass Quintet, David Christensen (saxophone), and other musical guests. The concert will be repeated at St. Paul’s on December 24th, Christmas Eve, at 7pm.

You can find out more about Jane Austen’s connection with Halifax in the “Austens in Halifax” walking tour my friend Sheila Johnson Kindred and I created.

I was delighted to have the opportunity to speak about the history of St. Paul’s—and the connection with the Austens—in the Evenings @ Government House series last month. I’m grateful to Their Honours, The Honourable Arthur J. LeBlanc and Mrs. Patsy LeBlanc, for the warm welcome they gave my parents and me.

The response I received from the audience was wonderful and it’s likely that I’ll give the same talk again in 2025—stay tuned for more details!

Photo by Michael Creagen

It was lovely to see roses still blooming outside St. Paul’s in late November:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Stories, Girls, and “The Vanished Years,” by Sarah Emsley

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 30, 2024

Stories, Girls, and “The Vanished Years,” by Sarah Emsley

Happy 150th birthday to L.M. Montgomery! I’m planning to honour Montgomery today by going for a walk near the ocean, dipping into her novels and journals to reread passages more or less at random, and writing fiction. If you’re marking the occasion, I’d be glad to hear what Montgomery means to you and how you plan to celebrate.

Before I head out for a walk, I want to share my essay “Stories, Girls, and ‘The Vanished Years’” with you—my contribution to “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” and the final post in this month-long blog series.

I hope you’ll enjoy reading my essay, which raises questions about where stories come from and who owns them. At the end, you’ll find a postscript that includes my reflections on copyright issues in the present day as well as in relation to Montgomery’s career.

(I took this photo on the north shore of PEI last summer.)

The Mysteries of the Past

“I’d dearly love to see all the things that are in it,” says Sara Stanley in The Story Girl, after she’s told her friends and relatives the story of the blue wooden chest in the kitchen of the old King homestead in Carlisle, PEI (116). Felicity has been making “a roly-poly jam pudding for dinner” and interrupting the Story Girl’s tale to add details of her own (113). When I read the novel as a child, I too was fascinated by the old blue chest. What was in there, and would it ever be opened, and what would happen to the things inside? Like Sara and Felicity and the other children, I was indignant and sorrowful over the sad history of Rachel Ward, whose fiancé, Will Montague, had run away without a word on what was to have been their wedding day. Like Sara, I wanted to tell stories about the mysteries of the past. Reading The Story Girl and other novels by L.M. Montgomery when I was very young inspired me to start writing.

When I was ten, I wrote a story in which the narrator is certain that the childhood secrets locked inside an old trunk will help her understand the problems of the present. Her life has “turned to dust” and she has “nothing left to hold onto except this trunk,” but she threw away the key years ago, thinking she would never need it again. “I needed a second chance at life,” she says, “but it was almost impossible.”

When I was older and read Great Expectations, I felt I knew Dickens’s Miss Havisham already, because I had read the Story Girl’s story of an abandoned bride. I felt a similar recognition when I encountered Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Beatrice and Benedick in Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing: I knew these characters, because Montgomery’s Anne Shirley and Gilbert Blythe had introduced me to their arguments and their affection more vividly than any abridged version of Austen or Shakespeare could have done.

Unlike Miss Havisham, however, who wears her wedding dress for years, long after her fiancé’s disappearance, Rachel Ward packed her dress along with linens and presents and left Prince Edward Island for Montreal, taking the key with her. She left the chest in the care of her relatives, and it is alternately a burden and a kind of gift. “It was very large and heavy,” says Bev, the narrator of The Story Girl, “and Felicity generally said hard things of it when she swept the kitchen” (113). Cecily speaks of her mother’s frustration about the chest: “She said if Cousin Rachel had to move that chest every time the floor had to be scrubbed it would cure her of her sentimental nonsense” (116). At the same time, the Story Girl crafts a tale about Rachel Ward and Will Montague so full of suspense and surprise that after she has revealed Will’s betrayal on the wedding day, Bev says, “We felt as much of a shock as if we had been one of the expectant guests ourselves.” Her story, and the prohibition on opening the chest, inspire Bev and his brother to look at the chest “reverently.” “It had taken on a new significance in our eyes, and seemed like a tomb wherein lay buried some dead romance of the vanished years” (116).

Is It Beautiful or Not Beautiful?

Is the chest an ordinary object, large and inconvenient, or is it a source of mystery and inspiration? Are its contents valuable, or were they meaningful only to a small circle of people, now dispersed or dead or both? Who has the right to open the chest, and when? And what is the appropriate thing to do with its contents? Is it more exciting to speculate about what’s inside or to find out and examine the contents in detail? Where do stories come from? From nothing or from something; from the past or the present moment or even the future? Are they invented or discovered or both?

I think about these questions as I sort through my own papers and possessions. Some of them are treasures; some are not. I think of Anne Shirley telling Marilla, “[O]ne can dream so much better in a room where there are pretty things” (AGG 142–43). “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful,” said William Morris in an 1880 lecture entitled “The Beauty of Life.” He believed that “if we want art to begin at home, as it must, we must clear our houses of troublesome superfluities that are for ever in our way” (107–8).

But how do we determine what is beautiful, what is useful? What do we keep, and why? What do we give away or throw away, or recycle? It isn’t only because my family and I recently moved to a new house and have been sorting through our belongings that I’ve been meditating on these questions, although that’s part of the reason. Trying to decide what to keep and what to let go is a lifelong process. Which books or ornaments to put on the shelf; which projects, appointments, and engagements to put on the calendar. It’s like editing: you write a draft, and then work, alone or with advice from someone else, to decide which words and sentences to keep and which to cut.

In an early draft of this essay, I included the famous line from the opening of George Eliot’s novel Daniel Deronda, “Was she beautiful or not beautiful?” (34). But then I took it out, because it doesn’t address the question of usefulness. And then I brought it back and put it right here, because it still resonates, and because although the Story Girl is initially confident that Rachel Ward “must have been beautiful, of course” (114), she has occasion to reassess her assumptions after the chest is opened and the children have examined the daguerreotypes inside (317).

“Is it better like this? Or like this?” George Saunders asks when he is revising his writing. “The artist, in this model, is,” he says, “like the optometrist.” Is it clearer like this or like this? Each decision shapes the story, just as each decision we make about our possessions and about how we spend our time shapes how we live. As Shawna Lemay writes in Apples on a Windowsill, it’s possible to listen to “the music and silence in things. What do they say about us, and what are they whispering to us about our lives and this world, this planet?” (58). As she says in an interview about her book, “If we change one thing in a composition, how does that change another? And if we can recompose a still life, can we recompose our lives, our thinking?”

I’m curious about the blue chest both as it appears in The Story Girl and as a metaphor. It occurs to me that we could arrange the objects inside Rachel Ward’s old blue chest and paint or photograph them to create a still life that tells at least part of her story: the “quaint little candlestick of blue china,” “a dozen tin patty pans,” the yellowed linens, the handkerchiefs, the Rising Sun quilt, the silk wedding dress and bridal veil, the photographs and letters, among other things (315–17).

I thought about and wrote fiction inspired by the blue chest when I was young, and the Story Girl’s story about it continues to fascinate me now that I am older and am writing historical fiction about the mysteries of the past. Thus, I want to focus on this story, this metaphor—even though I confess that from the moment I first started thinking of writing about what L.M. Montgomery’s work has meant to me, the temptation to talk about Emily of New Moon as a source of creative inspiration has also been very strong.

Learning to Climb

As a young girl I was inspired by Emily Byrd Starr’s experience of “the flash,” by her delight in the natural world and her extreme sensitivity to both beauty and pain. I used to write one poetical “deskripshun” of the landscape after another in my diary (ENM 58) during long summer road trips across Canada, when my family returned to visit grandparents in Alberta, which I thought of as my true home, from Halifax, Nova Scotia, which I was sure would be only our temporary home. Although I was, thankfully, not an orphan, I was in sympathy with Emily, who had been displaced and was obliged to adapt to a new and at first uncongenial place.

I used to climb the Norway maple in the backyard of our new house in Halifax at lunchtime, first hoisting myself up onto the green wooden fence so I could reach the lowest branches of the tree (the gables of our house were white and the shutters were black, but at least the fence was green), then walking up the set of branches that resembled a perfect spiral staircase, up to the spot where four sturdy branches pointed east, west, north, and south, where I would sit down on the widest one (east) and open the plastic Sobeys bag that was tied around the tree trunk and take out a book or paper and pencil and lean back against the branch, reading or writing until it was time to climb down to the real world and walk a block and a half to go to school for the afternoon. I could tell you about the stories and poems I wrote, and I could even show you the page where, like many another young writer, I recorded my desire to follow in Montgomery’s and Emily’s footsteps, climb the Alpine Path, “And write upon its shining scroll / A woman’s humble name” (quoted in AP 10 and ENM 351). I haven’t kept everything, but I did keep that page.

I could connect the past with the present, and tell you that last year when my husband and daughter and I were searching for a new house, we sort of miraculously—“I call it providential,” Diana Barry might say—found and bought one just around the corner from the house where I grew up and where my parents still live (AGG 239; emphasis in the original). As I write (on this Saturday afternoon in January 2024), I am looking out the window of my new office, across the length of our backyard and the widths of four more yards in a row, until my eyes settle on the fifth backyard, the one in which I used to climb trees and play with my three younger siblings and a group of friends who lived on our block. When I open the blinds and look out at this view, I often think of the opening lines of Montgomery’s poem “The Gable Window”: “It opened on a world of wonder, / When summer days were sweet and long.” Although the Norway maple with the “spiral staircase” was cut down decades ago, and a neighbour’s pale green–gabled garage obscures my view of the exact spot where it once stood, I can see the silver maple that still stands next to that spot, its branches bare today against the grey winter sky, and I can almost see myself sitting in my favourite tree, at age ten, dreaming of a future as a writer. Asked if she’d still write even if she knew she would never be published, Emily says, “Why, I have to write—I can’t help it by times—I’ve just got to” (ENM 409; emphasis in the original).

The Remembrance of the Past

I want to return to the blue chest and its secrets, to my deep and abiding interest in the past: the history of other people’s lives as well as my own.

I recently heard a yoga instructor talk about letting go: “As we all know,” she said, encouraging us to release tensions and worries, aches and pains, “the past doesn’t exist anymore, right?” The quiet, reflective mood at the end of that yoga class didn’t feel like the right moment to argue. But I did want to argue. I still do. Just as the very young Anne Shirley was shaped by the loss of her parents or L.M. Montgomery was shaped by the loss of her mother, like the characters in Pride and Prejudice, we are all “marked, even scarred, by history,” as Isobel Armstrong says in her introduction to that novel (ix). We don’t have to let ourselves be defined by, or imprisoned by, the past, but I don’t think it’s possible to pretend it doesn’t exist. I agree with William Faulkner, who famously said “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Things happened to us, and to others, or we made them happen; we responded or reacted (or didn’t) to these things. And even if our memories are hazy or our records are incomplete, these things had consequences, and they meant something, and their meanings persist. The stories are still there, whether they’re told or not.

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet famously tells Mr. Darcy to “think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure,” a beautifully seductive line that is, like William Morris’s injunction about useful and beautiful things, repeated (seemingly endlessly) on posters and coffee mugs, necklaces and T-shirts. But Darcy insists on the importance of what he has learned from thinking about painful aspects of the past (327–28). This part of the conversation doesn’t usually (doesn’t ever?) make it onto posters and T-shirts. But it’s an essential part of the story of the creation of stories. Without conflict, there is no story. John Gardner writes in The Art of Fiction that “All meaning, in the best fiction, comes from—as Faulkner said—the heart in conflict with itself” (187).

“What would it be like,” Montgomery asks in a journal entry dated 30 June 1902, “to live in a world where it is always June?” (CJ 2, 57). In Anne of the Island, published in 1915, Montgomery gave these same words to Anne: “I wonder,” Anne says to Marilla and Mrs. Lynde, “what it would be like to live in a world where it was always June” (214). Montgomery is, of course, the voice of both Anne and Anne’s audience. In her journal, she asks, “Would we get tired of it? I daresay we would, but just now I feel that I could stand a good deal of it if it were as charming as today.” In the novel, it is Marilla who says, “You’d get tired of it,” and Anne agrees, but, like her creator, feels certain “that it would take me a long time to get tired of it, if it were all as charming as today. Everything loves June.” As Austen and Montgomery both knew, when we open up old chests or boxes or books or letters that hold the secrets of the past, we’re almost certain to find conflict, whether it’s conflict between people or the heart in conflict with itself or both.

Stories Told and Untold

At the end of The Story Girl, the blue chest is opened at last, and Sara Stanley and the others get to see the things inside or, rather, most of the things (314–19). Will Montague’s letters are to be burned, along with the wedding dress. The blue candlestick, pink and gold vases, handkerchiefs, and china plate that the children receive as mementos tell only part of the story, for the letters will remain unread, and even these private papers would give only Will Montague’s perspective on the romance. And since Rachel Ward herself says almost nothing, aside from leaving the key and instructions about what to do with the contents of the chest after her death, her private version of the story dies with her.

Elizabeth Waterston says in Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery that in writing The Story Girl, Montgomery “opened her own version of the blue chest,” celebrating her “memories, passions, and experiences, but also her own ambition and her own accomplishments, her books and life documents” (48). For this novel and others, Montgomery drew on her past and her papers, but she was also inspired by things she owned, such as her green and white ceramic dogs named Gog and Magog, who make an appearance in Anne of the Island (84). Like Hilary Mantel, she was “interested in art that’s found, as well as art one creates” (“Iron” 34:30). When I was younger, I thought that to write stories and novels, one had to be a natural storyteller with a talent for spinning stories out of thin air. From Montgomery, I learned that stories don’t have to come from nothing.

I’m intrigued by the difference between opening a chest or trunk of one’s own possessions and papers and opening one that contains someone else’s things. The past exists, but to whom does it belong? For several years, I’ve been working on fiction about Jane Austen and her family, to bring to life, in Montgomery’s words, the “dead romance of the vanished years.” Working with biographical material, critical studies of Austen’s novels, published and unpublished letters, and, of course, her novels, along with the stories and poems and plays she wrote when she was very young, I’ve been imagining the lives of the Austens.

It’s been helpful to think of other writers who, like me, feel qualms about writing fiction that presumes to know what was going on in the minds and private lives of people in the past. Mantel says, “I don’t think any of us escape unease about our trade” (Memoir 269). In Michael Crummey’s novel River Thieves, one character reflects that “There were things he’d seen and heard in his days he vowed to take to the grave, as if that was a safe place for the truth. But two hundred years from now, he knew, some stranger could raise his bones from the earth and put whatever words they liked in his mouth.” In a lecture called Most of What Follows Is True, Crummey says that he, as the author, is, of course, the stranger: “It’s me he is pointing to out of the pages of the novel, to say to the reader, Don’t be fooled into thinking these words are mine. No one could ever know the actual truth of who I was or what I thought or how I felt about what happened” (41–42). There’s a perpetual tension between telling stories and leaving them untold. Montgomery includes a scene in which the Story Girl dreams that they’ve opened the blue chest without Rachel’s permission. The children examine everything, “laughing, and trying the things on, and having such fun. And Rachel Ward herself came and looked at us—so sad and reproachful—and we all felt ashamed, and I began to cry, and woke up crying” (210).

What risks do we take when we turn the key and open that blue chest? What do we gain, and what might we lose? And why, I can’t help but wonder, am I spending this afternoon writing about these questions, when I had planned to spend it sorting through boxes in the spare room of our new house, deciding what to keep and what to give away? Maybe I can accomplish some of the work of sorting and letting go right here. How many nine-inch springform pans does one family need? How many teacups? (Give the extras away.) Should I keep all the dresses my mother made for me when I was young, or only my favourites? (Keep them all.) Do we really need champagne glasses, when no one in our house drinks champagne? (Probably not.) In an essay about getting “rid of [her] possessions, at least the useless ones,” Ann Patchett writes about a similar champagne-glass dilemma: “Had I imagined that, at some point, twelve people would be in my house wanting champagne?” She writes of catching herself ascribing feelings to these objects: “I had disappointed the glasses by failing to throw a party at which their existence would have been justified.” We can’t keep everything. In the end, of course, we can’t keep anything at all. As my five-year-old niece asked her mother recently, “Did you know that when we die, we can’t take anything with us? So we’ll all be naked, because clothes are things.”

The Power of the Imagination

I’ve been asking the question Mantel poses in the title of one of the Reith Lectures she gave in 2017, God’s question to the prophet Ezekiel: “Can These Bones Live?” (Memoir 284–92). Shall we attempt to bring long-dead people to life? And then put clothes on them—historically accurate clothing, if it can be found, if the research is thorough enough? And serve them sponge cake or syllabub, along with a cup of tea or a glass of wine? Like Mantel, I believe it will work, and when it does, writing feels like magic. Montgomery writes, “To breathe the breath of life into those dry bones and make them live imparts the joy of creation” (CJ 2, 174).

Mantel writes that “You cannot give a complete account. A complete thing is an exhausted thing” (Memoir 288). Or, as my grandfather used to say—about life in general, but it works also as a metaphor for writing: “Take the garbage out or it will bury you.” Mantel suggests, “You are looking for the one detail that lights up the page: one line, to perturb or challenge the reader” (Memoir 288). Yet, as she points out, “The historian will always wonder why you left certain things out, while the literary critic will wonder why you put them in” (Memoir 285). As the Story Girl says after Felicity has interrupted the story of the blue chest to add a detail, the addition “spoils the effect.” “What would you feel like,” the Story Girl asks, “if I went and kept stirring things that didn’t belong to it into that pudding?” (114).

Once the blue chest has been opened the Story Girl reflects on what they have learned about Rachel Ward. She’s making taffy during the conversation, just as Felicity was making a pudding during the group’s first discussion of the story. The Story Girl is sad and sorry that the mystery of the chest has dissipated, and thus there is no “scope for imagination,” as Anne Shirley might say (AGG 15). I would argue, however, that there’s still plenty of room to imagine, among other things, what Will Montague’s letters might have said, and what Rachel Ward’s life was like in the years that followed his betrayal. Felicity says, “It’s better to know than to imagine,” but the Story Girl is quick to object that “When you know things you have to go by facts. But when you just dream about things there’s nothing to hold you down” (319).

Like the Story Girl—and Anne Shirley, Emily Starr, and L.M. Montgomery—I believe in the power of the imagination. Rereading these novels inspires me to keep writing fiction. If I were to write a complete account of the years in which L.M. Montgomery’s stories sparked my imagination and helped shape my dreams, it would be an “exhausted thing.” I’ll add just one more scene from the backyard in which my siblings and friends and I used to play, a scene I can still picture vividly, from those years of “blithe companionship, shared thoughts, and adventuring” (SG 320), though we’re all much older now, and, on this particular snowy afternoon, there are no children or adults in my parents’ backyard or my own, or the four yards in between. Even the neighbourhood dogs are inside on this cold day, waiting for supper.

But I can see that group of us in the yard on a summer day, before I got in the habit of climbing that maple tree to write stories and pretend I was Emily Starr, before I wrote those poetical deskripshuns in my diary, so I’m probably about eight years old. I know Anne of Green Gables, but haven’t yet met Emily. Is it a perfect June day? I’m not sure, but it might be. I want to build an airplane that I can use to fly all the way from the East Coast back to the prairies, to Granny’s garden and the shed where Grandad once helped me build a small red wooden boat and the cabin at the lake that Grandpa and Grandma built. I believe it is possible to create this airplane myself, because I know my grandparents are skilled at building things and one of them served as a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. I have it all worked out, and I know how I will get to Alberta without losing my way: I’ll fly directly above the train tracks and follow them across the country.

My airplane is a wooden toy chest made by Grandad and painted bright white, with my name written in red paint in block letters, my first name on the lid and my last name on the front of the chest. I’m trying to persuade my siblings and friends to fly with me. I know how to get there, I’m saying. I have a set of wooden stilts, also made by Grandad, and I’m planning to use them to help me steer the plane. They’re only about four feet long, but, in my imagination, they are long enough to reach from my airplane high in the sky, down to the train tracks. Is anyone going to join me? It’s a plan filled with risks. It’s a long journey, and I’m not sure yet how it will go or exactly what I’ll take with me in the white chest and what I’ll leave behind. But I want to bring my family and friends, and I have all the enthusiasm and confidence of youth, and I believe I’ll get there, someday.

One might say this little story isn’t really a story, because there’s no conflict. But there is: my heart was in conflict with itself, torn between the need to live in the present moment, where my father had a job, and we had a house, and we were about to put down roots in Nova Scotia—and the strong desire to return to the past, to the place where I spent the first years of my life. I wanted to be in two places at once, and I was learning, from experience and from reading, about the power of the imagination and the joy of creation.

As many regular readers of this blog will know already, I’m the author of Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues (Palgrave) and the editor of a critical edition of Edith Wharton’s 1913 novel The Custom of the Country (Broadview). I’ve taught classes on Jane Austen in the Writing Program at Harvard University, I held a SSHRC postdoctoral fellowship at the Rothermere American Institute, University of Oxford, and I have a Ph.D. in nineteenth-century English literature from Dalhousie University. As readers of this essay will know, I live in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with my family, and I’m currently working on a novel.

My daughter took the photo of me last summer in New York City; I took the photo of my friend Marianne Ward’s copy of The Story Girl.

A postscript:

I originally wrote this essay, “Stories, Girls, and ‘The Vanished Years,’” for the “Writers and Artists Respond to L.M. Montgomery” collection at the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, after my friend Kate Scarth, editor-in-chief of the Journal, invited me to contribute a submission.

After my essay was accepted, edited, and copyedited, however, when the Journal sent me their contract, I learned that they require authors to sign a Creative Commons BY 4.0 license, which “allows the user to share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.” In other words, the author gives up copyright in her work.

I hadn’t ever been asked to sign a contract under these terms, and after consultation with the Writers’ Union of Canada, I decided not to sign, as I prefer to retain copyright for my writing. The Union’s statement on Creative Commons licenses points out that while choosing to sign this type of license is a personal decision, “once the work is released in that way it will never be under the writer’s ownership and control again. It is the equivalent of giving one’s copyright to a publisher for their sole profit and benefit, and the Union advises authors never to do that in a traditional publishing contract.” (John Degen, CEO of the Writers’ Union of Canada, has written about Creative Commons licenses in this Quill & Quire article.)

When I started writing this essay last winter on the stories we keep and the stories we give away, stories that belong to us and stories that belong to other people, I didn’t anticipate how complicated the publication process would be and I didn’t know that these complexities would be directly linked to the very questions I explore in the essay.

In the summer, Kate and I had an in-depth conversation about copyright and Creative Commons licenses, and after I had withdrawn the essay from the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, she encouraged me to publish it on my blog. I’m grateful to her for our conversation, her thoughtful consideration of the topic, and her suggestion that I consider writing this postscript about the experience. I’d also like to thank Liz Rosenberg, Jane Ledwell, and Kate for their excellent comments and suggestions during the editing and copyediting process.

As I pay tribute to L.M. Montgomery on her 150th birthday today, I—like readers around the world—appreciate the tremendous gift she gave us through her writing. She dealt with significant challenges in her career and her personal life, and I’m grateful to her for sharing these experiences in her journal and showing us how she found ways to persevere and look for joy, and friendship, and comfort in nature whenever she could.

In recent months, my sympathy for the challenges she faced as a writer has increased, as I’ve been rereading (in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, by Mary Henley Rubio [2008]) the details of her dealings with L.C. Page, the publisher who asked her to sign away the copyright of Anne of Green Gables and her next six books, including The Story Girl, and ultimately pressured her to sell all her rights in these books, including the right to receive royalties—after which he immediately sold the film rights to Anne of Green Gables and pocketed the substantial profits.

It happens that yesterday, November 29th, is the anniversary of the date Jane Austen wrote to her friend Martha Lloyd in 1812 to share the news that she had sold the copyright for Pride and Prejudice to Thomas Egerton, who had published her first novel, Sense and Sensibility.

We take risks if we open the blue chest to look at the stories of the “vanished years” inside. But it is also risky to leave it locked. I continue to believe the past is alive and with us.

(Another photo from that sunset walk on the north shore of PEI last summer.)

Works Cited

Armstrong, Isobel. Introduction. Austen, Pride and Prejudice, pp. vii–xxx.

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. 1813. Oxford UP, 1990.

Crummey, Michael. Most of What Follows Is True: Places Imagined and Real. U of Alberta P, 2019.

Eliot, George. Daniel Deronda. 1876. Penguin, 1986.

Faulkner, William. Requiem for a Nun. Random, 1951.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. Vintage, 1983.

Lemay, Shawna. Apples on a Windowsill. Palimpsest Press, 2024.

Mantel, Hilary. “The Iron Maiden.” The BBC Reith Lectures, 20 June 2017. www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b08v08m5.

—. A Memoir of My Former Self: A Life in Writing. Harper Collins, 2023.

Montgomery, L.M. The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career. 1917. Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

—. Anne of Avonlea. 1909. Tundra, 2014.

—. Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Tundra, 2014.

—. Anne of the Island. 1915. Tundra, 2014.

—. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901–1911. [CJ 2]. Edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston, Oxford UP, 2013.

—. Emily of New Moon. 1923. Tundra, 2014.

—. “The Gable Window.” The Poetry of Lucy Maud Montgomery. Edited by John Ferns and Kevin McCabe, Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1987, pp. 81–82.

—. The Story Girl. 1911. Tundra, 2014.

Morris, William. “The Beauty of Life.” 1880. Hopes and Fears for Art: Five Lectures. Longmans, Green, 1919, pp. 71–113.

Patchett, Ann. “How to Practice,” The New Yorker, 8 March 2021. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/03/08/how-to-practice.

Saunders, George. “What Writers Really Do When They Write.” The Guardian, 4 March 2017. www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/04/what-writers-really-do-when-they-write.

Waterston, Elizabeth. Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery. Oxford UP, 2008.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed my essay, I hope you’ll consider recommending this post to a friend, and if you aren’t yet a subscriber, I hope you’ll sign up to receive future posts.

You can find the complete list of contributions to “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150” here.

And if you’d like to read more about my books, you can find more details here.

This essay, photos, and additional text are copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 29, 2024

Eavesdropping, Power Plays, and Empathic Storytelling in L M. Montgomery’s Emily Trilogy, by Lesley D. Clement

“Little pitchers have big ears.” (Emily of New Moon, Chapter 17)

Courtesy of Christina Morrison

(From Sarah: This is the thirteenth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . There’s one more post in the series and it’s an essay by me, entitled “Stories, Girls, and ‘The Vanished Years.’” I’ll share it here tomorrow, on Montgomery’s 150th birthday, November 30th. Thanks for celebrating with us!)

In Eavesdropping in the Novel from Austen to Proust (2003), Ann Gaylin argues that eavesdropping “exposes the paradox of representing the ideology of separate spheres, in that the portrayal of private space requires the narrative violation of that area supposedly impervious to intrusion.” Indeed, this paradox is reflected in the etymology of the word “eavesdropping”: under the eaves, outside listening in. In a typical eavesdropping scene, a powerless person attains secret knowledge about others and/or self through private information garnered when listening from within an enclosed space: eavesdropping from behind draped windows and doorways and from closets is particularly popular; eavesdropping from under parlour tables or from overhead kitchen lofts or church steps less so.

Gaylin begins with examples of eavesdropping in much grander scenes than L.M. Montgomery’s Emily trilogy: those from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice that initiate and resolve Elizabeth Bennet’s narrative arc. The title of Gaylin’s first chapter, “I’m all ears: Pride and Prejudice, or the story behind the story,” has been a clear influence on a line of wallflowers (I recognize, of course, that Elizabeth is nobody’s wallflower), a line that leads to Julia Quinn’s creation of Bridgerton’s (assumed powerless) wallflower Penelope Featherington. Gaylin argues that the theme of identity formation in Austen’s novel is strongly connected to that of the porous boundaries between gendered spheres and the “tenuousness of the false binary” between private and public, themes that are equally clear—perhaps even more so—in later novels such as Montgomery’s Emily trilogy from the 1920s and Quinn’s Bridgerton novels from the 2000s, both periods when modes of acquiring and transmitting information were rapidly changing.

Montgomery’s Emily trilogy has scenes of both inadvertent overhearing, as with Austen’s Elizabeth, and covert eavesdropping, as with Quinn’s Penelope, that align with transgressive power plays to attain private information, such as unsanctioned reading of diaries and letters, and disseminating this information through gossip. In Austen, Quinn, and Montgomery, it is especially the eavesdropping undertaken by those deemed small and powerless that profile power struggles at the core of identity formation. With Emily, as with Penelope, there is the added layer of negotiating boundaries of what is ethical to include in one’s writing.

In the Emily trilogy, the eavesdropping scenes, like those of snooping and gossip, raise non-negotiable questions about the social practice of applying different rules for children and adults—for Montgomery, this is blatantly wrong—and more subtle questions concerning Emily’s identity formation and apprenticeship as an ethically empathic storyteller. There are several eavesdropping scenes that are primarily about game-playing power struggles in Emily of New Moon, such as those in Chapter 16, “Check for Miss Brownell” (“check” having the double entendre of “watch out” and “checkmate”): Rhoda’s eavesdropping and snitching on Emily reading her poetry to Ilse, and the aftermath of this episode, the hilarious scene of Perry’s eavesdropping from the “blackhole,” the kitchen loft, on Miss Brownell’s one-sided reporting of Emily’s behaviour at school. It is, however, the more nuanced questions that eavesdropping raises about public and private identity and Emily’s storytelling that I will focus on here.

The most obvious eavesdropping scene occurs early in Emily of New Moon, and while Emily does not gain any power or influence from what she overhears—who will be adopting her—it prepares for later eavesdropping scenes. Domestic space, the parlour, itself often a feminized space (as opposed to the male domain of office, study, or library), has been converted to a public space, even a public forum on the fate of Emily Byrd Starr. Gaylin compares the parlour to a threshold because “[i]n both sites, public and private spheres and activities converge; boundaries are fluid” with eavesdropping profiling “the importance of boundaries in the very moment and act of their being defied.” The title of Chapter 4— “A Family Conclave,” which denotes a private and often secret meeting—underscores this liminality: the Murrays have converged on Starr terrain, and their proceedings are being judged and will be circulated beyond the family conclave by Ellen Greene. The narrator hedges on the legitimacy of Emily’s eavesdropping from beneath the parlour table as a transgressive practice because Emily knows no better, but for Aunts Ruth and Elizabeth, Emily is categorically a “shameless little eavesdropper.” Meanwhile, under the table, Emily has been honing her observational and writerly skills of description and narration as she silently (for the most part) partakes of the courtroom drama of custodial responsibility, mentally defending herself and taking humorous jabs at the opposition as conveyed through the narrator’s parenthetical insertions.

Powerless once discovered, Emily at first judges herself as others have done—as a sinful transgressor—but purges the pain and humiliation by writing it out and finds satisfaction that her impressions of her relatives—her own secret knowledge—remain private. This will prove to be an illusion when Aunt Elizabeth later asserts what she thinks her right as an adult to read Emily’s private writing. Aunt Ruth is even more aggressive as she riffles through Emily’s private property to expose her niece’s slyness. The adults may not engage in shameless eavesdropping on private conversations, but reading private or intimate conversations that one has with oneself in diaries is not considered trespassing. (Aunt Elizabeth does learn to respect Emily’s boundaries, which, it might be argued, makes her a better listener to Emily’s stories later in the trilogy.)

The second main eavesdropping scene occurs in Chapter 4 of Emily Climbs, aptly titled “‘As Ithers See Us.’” While the narrator says that the earlier scene “had been voluntary, while this was compulsory,” a qualification immediately follows with “at least, the Mother Hubbard had made it compulsory,” “compulsory” because Emily thinks the wrapper makes her look “ridiculous.” The occupation in which Emily is engaged when the two inveterate gossips, Mrs. Ann Cyrilla and Miss Beulah Potter, intrude—the traditional sanding of the floor in a herringbone pattern—is a matter of family pride, but along with hearing about herself as “ithers” see her, she hears about how they perceive the Murrays: as “mean” or penny-pinching, as old-fashioned, and . . . well, as “ridiculous.” Having been caught eavesdropping from a boot closet does not deter Queen Emily; it is the pity that these gossips express towards the Murrays and their invading private lives to humiliate the Murrays publicly that Emily finds so disturbing.

Like the first eavesdropping scene, this second one finds Emily replaying and learning from what she has heard, but much more extensively and deeply than the first time, as she now takes a “dispassionate” and honest view of what she has heard. As an empathic storyteller—or quite simply as a sensitive and empathic human being—this is a vital step: to remove herself far enough from the scene so that she can widen her lens and understand that there are multiple ways of listening (not just hearing) and understanding others and self. This comes only with Emily’s growing confidence that she cannot “live in other people’s opinions” (the public view) but must continue to believe in herself and to “live in” her own truth of herself. As Emily moves from poetry to storytelling as her preferred medium, this skill will be essential, the balancing—indeed, the blurring—of her own sense of self and the ability to see the world, including herself, as “ithers” do.

Just before this second eavesdropping scene is “In the Watches of the Night” (Chapter 3), the scene of Mad Mr. Morrison, which perhaps more than any other episode in the trilogy raises two related ethical questions: the ethics of eavesdropping on intimate scenes and the private terrain of the mind, and the ethics of eavesdropping on real people for artistic content. The artist’s dilemma of how to use their resource material responsibly and ethically is a thread that runs throughout the trilogy. Both these questions are raised when, as a prelude to the drama about to take place involving Mr. Morrison, Emily is in church observing and playing a “game of guessing” about the “inner, secret lives” and “hidden motives and passions” of the “public assemblage.” Our aspiring storyteller relishes the “sense of power” this game gives her.

Although this prelude is more visual than aural, the gothic drama that follows is clearly aural as Emily hears Mr. Morrison with his “dreadful, inhuman laughter” as he seeks his lost Annie. Later, in the coda to this drama, after Teddy has been mysteriously summoned by Emily’s call, “the artist in him” has a visual response to the scene. He thinks that he would like to paint this man and “the ageless quest in his hollow, sunken eyes,” but there is no indication that Teddy ever does so. Instead, he sends the old man on his way with the encouraging words that “I think you will find [Annie] sometime.”

Nor for Emily do the cries of the “heart-broken old man” inspire her to become a conduit of his story for public consumption, although she does think that she might tell Ilse and “bind her to secrecy.” But does Emily ever tell this story to Ilse? She more likely records the evening’s events as a chilling anecdote in her private diary. Unlike the “dramatic possibilities” of the sounds of the storm before she witnesses Mr. Morrison’s “inhuman laughter,” and which she imagines incorporating into a novel someday, Mr. Morrison’s very human story is one that Emily has experienced so intimately through her fear of being touched, caressed, by him that it must be given the sanctity of privacy. Moreover, it is a story that she has experienced in a moment of inadvertent eavesdropping, therefore not one that she can ethically tell, and must remain her own secret knowledge.

But she does take this secret knowledge forward into her life when she is later able to empathize with Mrs. Kent and her story, another story that is too intimate, too personal, too private, and that will not find itself into the public domain via Emily the storyteller. It might be argued that both Mr. Morrison and Mrs. Kent are archetypal characters and their narratives are ageless and so essentialized rather than particularized, but Emily has experienced their particular stories firsthand and is learning about respecting boundaries, however blurred, between private lives and public discourse. Mr. Morrison’s and Mrs. Kent’s are not her stories to tell, nor is she really ready (if she ever will be) to tell the intimate stories—theirs and hers—that transpired “in the watches of the night.”

At the end of Chapter 3, Emily feels that “somehow” she has “grown up all at once tonight.” Although there is still growing to do, Emily’s evolving understanding of the need for respecting her own soul (or humanness) and the souls (or humanness) of others is a powerful statement about privacy, publicity, boundaries, and ethically empathic storytelling. In the prelude to this eavesdropping scene, Emily has found “power” in trespassing on the souls of others; in the coda to this scene, she is learning about respecting humanness and the “power” to resist doing so.

Quotations are from the Tundra edition of Emily of New Moon and Emily Climbs (2014). Thank you to Christina Morrison for permission to include her illustrations from the Emily of New Moon graphic novel.

Lesley D. Clement, past visiting scholar at the L.M. Montgomery Institute (2019–21) and a consulting editor of the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, has held teaching and administrative positions at various Canadian universities, most recently Lakehead-Orillia. She is (co-)editor for the Vision Forum and the Vision, Mental Health, International Notes, Re-vision, and Back-to-the-Future collections of the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies. She has published on visual literacy, visual culture, empathy, and death in picture books and in Montgomery’s writings. Her work on Montgomery appears in Studies in Canadian Literature, L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys (ed. Clement and Bode), L.M. Montgomery and the Matter of Nature(s) (ed. Bode and Mitchell), the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, L.M. Montgomery and Gender (ed. Pike and Robinson), and Children and Childhoods in L.M. Montgomery (ed. Bode, Clement, Pike, Steffler). She is the co-chair of the Scientific (Programming) Committee for the IBBY 2026 Congress to be held in Ottawa.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

L.M. Montgomery and the Lucky Cat, by Susannah Fullerton

Books and Chums, by Trinna S. Frever

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Lesley Clement 2024; illustration copyright Christina Morrison 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 27, 2024

L.M. Montgomery and the Lucky Cat, by Susannah Fullerton

“A house isn’t a home without the ineffable contentment of a cat with its tail folded about its feet. A cat gives mystery, charm, suggestion.”

— L.M. Montgomery, Emily’s Quest (Chapter 9)

In a life that was often troubled and unhappy, L.M. Montgomery always had one unfailing source of comfort and inspiration—her cats. As a lonely orphan living with her grandparents, she befriended barn cats and smuggled them into the house. In the journal she started when fourteen years of age, she pasted tufts of cat fur, mourned the deaths of beloved feline friends and wrote lovingly of her “pussy-folk” (quoted by Weber). Max, Pussywillow, Catkin, Mephistopheles, Bobs, Topsy and Maggie were just some of the cats she cherished, and sharing her home with cats was something she viewed as a necessity throughout her life.

L.M. Montgomery’s cat Lucky, Norval – ca. 1930s | Courtesy of Archival & Special Collections, University of Guelph. L. M. Montgomery Collection, XZ1 MS A097 040 0599s

(From Sarah: This is the twelfth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, this coming Saturday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!

Please join Susannah and me on Saturday for an online event: Susannah is hosting a party for LMM’s 150th on Zoom and she invited me to talk about celebrations that have been happening in Canada. With the help of my friend Joanne, I put together a short video that includes photos of places that were dear to Montgomery’s heart. Find out more about the party here. The recording will be available afterwards.)

There were two cats that were particularly important—Daffy (technically Daffy the Third, as he had been preceded by two other felines of that name) and Lucky. Daffy was a Cavendish cat, grey and sleek, and he arrived at her home in 1906. Maud’s parents had never been fond of cats and her grandparents detested them, but somehow Daffy won over Grandmother McNeil: “Grandmother pets him almost as much as I do. Formerly she did not like my pets and seemed to resent the affection I gave them. But in these lonely later years, neglected by her children, she seems to have changed in this respect and grown fond of the Daffies and almost indulgent to them. Well, there are many worse friends than the soft, silent, furry, cat-folk” (January 7, 1910, Complete Journals 265). Some of her grandmother’s last words were an enquiry for Daffy, and it comforted Maud to know that her pet had brought solace and companionship to the woman who had given a home to her and (reluctantly) to her cats.

After her grandmother died in 1911, Maud took Daffy to Park Corner, home of her cousins, but he was frightened and kept disappearing for days, much to her consternation. When, later that same year, Maud married the Reverend Ewan Macdonald, the couple settled in the manse at Leaskdale, Ontario. There was no doubt in her mind that Daffy was needed to share this new marital home, so Daffy was shipped from Prince Edward Island to the station at Uxbridge, enduring three miserable days in a crate. He arrived dehydrated and scared, but was soon master of the new house, lying on Maud’s writing desk, climbing on to the dining table as she ate, and resting on his own special chair in the parlour. He gave her solace when a beloved cousin died, when she had a still-born baby, and through the early challenges of her marriage (Ewan suffered terribly from depression).

Daffy died in 1920 (he was accidentally shot) and Maud was heartbroken: “We buried him behind the asparagus plot on the lawn—old Daff, with his plumy tail, his distinctive markings, his wild glowing eyes—my old companion of days and nights of long ago, my faithful furry comrade through the many lonely evenings of the past two years. I feel a sense of desolation and loneliness. Ewan says ‘Get another cat.’ I don’t want another cat. No cat can ever again be what Daffy was” (August 22, 1920 journal entry, quoted in McCabe 143). She gave her heroine, Emily, a grey cat named Daffy in the series of books she started soon after.

In spite of her vow not to be owned by another cat, Maud found herself in 1923 sharing her desk and home with Lucky (originally known as Good Luck), another Cavendish cat who was silver-grey with black stripes. He too had to be shipped from PEI and, like Rusty in Anne of the Island, had to learn to live with feline resident Paddy, who had been taken in by the Macdonalds a short time before. Maud rejoiced in her new pet, relishing “his tiny flanks heaving up and down under my fingers and his little body vibrating with his rapturous purrs” (January 9, 1938 journal entry, quoted in Rubio 498). In her busy life as author, minister’s wife, and mother of two sons, she gained vital rest and relaxation from Lucky. When the family moved to a parish in Norval, and from there to retirement in Toronto, Lucky, of course, went with them.

Lucky died from cancer in 1937 and Maud was distraught. She buried her “captain of cats” in the garden and dedicated Jane of Lantern Hill to his memory. Lucky’s obituary in her journal runs for forty pages and is, according to biographer Mary Henley Rubio, “a tour de force in the annals of pet obituaries.” The ache of longing for Lucky never really left Maud: “Cats before him I loved as cats. I loved Luck as a human being. And few human beings have given me the happiness he gave me” (January 9, 1938 journal entry, quoted in Rubio 498-99). She was at the time coping with many personal problems—her husband’s severe depression, the wild behaviour of her son Chester, and she was fighting legal battles with publishers. She wept when, reaching out to caress Lucky’s silken flank in the night, she found only an empty space.

For Maud the affection of a cat was a test of character and readers of her novels know there is always something fundamentally wrong with a character who dislikes cats. Gilbert Blythe even includes the promise of a cat in his second, successful, proposal to Anne. When asked to sign her books for eager fans, Maud often drew a tiny cat silhouette below her signature, sharing her love of cats with those who loved her books.

There were many cat friends in her life, but two stood out as the ones she especially adored—Daffy and Lucky. Ironically, the two animals were misnamed. Daffy should have been the one called “Lucky.” After all, he was the cat who oversaw the creation of Anne of Green Gables, who curled up on its pages of manuscript or perhaps walked over the pages with inky paws, gave warmth and companionship to the young author with dreams of literary fame. It was Daffy who was a constant presence as the tale of a red-headed orphan girl progressed, Daffy who was at Maud’s side when news came her book would be published, and Daffy who witnessed the exciting arrival of her first published novel. Daffy was surely one of the most fortunate of cats to be present at the birth of a great Canadian novel and one of the luckiest of animals to be the “owner” of L.M. Montgomery.

Works Cited

McCabe, Kevin (compiled). The Lucy Maud Montgomery Album. Ed. Alexandra Heilbron, Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1999.

Montgomery, L.M. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901 – 1911, ed. Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston. Don Mills, ON: Oxford UP, 2017.

Rubio, Mary Henley. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. N.p.: Anchor Canada, 2008.

Weber, E. “L.M. Montgomery as a Letter Writer.” Dalhousie Review 22.3 (1942), 309.

Susannah Fullerton, author, lecturer and literary tour leader, has been President of the Jane Austen Society of Australia for thirty years. She has also been a life-long reader of L.M. Montgomery’s novels and gives frequent talks about her life and fiction. She writes a popular blog, Notes from a Book Addict, and has been awarded an Order of Australia Medal for “Services to Literature.” To learn more about her books and literary tours around the world, or to sign up for her free newsletter, visit https://susannahfullerton.com.au/.

Her forthcoming book, Great Authors and the Cats who Owned Them, will be published by Bodleian Library Publishing in late 2025. The book includes a chapter on L.M. Montgomery and the cats who owned her.

If you’re interested in Susannah’s online celebration of L.M. Montgomery’s 150th birthday, which I mentioned above, you can learn more and book tickets here. The event includes guest speakers and activities. (For those of us who live on the east coast of North America, it will take place very early in the morning. Fortunately, the ticket price includes access to the recording, so you could watch it later if you prefer.) Susannah invites kindred spirits to pour a glass of raspberry cordial or wine, cut a slice of ruby jelly layer cake, and join the party.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “Eavesdropping, Power Plays, and Empathic Storytelling in L M. Montgomery’s Emily Trilogy,” is by Lesley D. Clement.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Books and Chums, by Trinna S. Frever

Can’t all Canada agree to like Montgomery (except her poetry)? by Audrey Loiselle

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Susannah Fullerton 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 25, 2024

Books and Chums, by Trinna S. Frever

As I sit down to write this, I’ve just returned from a book group meeting. We weren’t discussing L.M. Montgomery today. We just finished Marie Benedict’s Lady Clementine, though most of us liked her collaboration with Victoria Christopher Murray, The Personal Librarian, better. While we had a great discussion, I missed not hearing the opinions of Harriet, one of our beloved book group members who recently passed away. Had she been there, her opinions would very likely have been lively and delivered with laughter. That was Harriet’s way, at least in as much as I knew her from the group. I recall with great fondness the many times we’ve sat around a table or Zoomed together “poring over a book,” as L.M. Montgomery says in Anne of Green Gables (Chapter 12). Poring over a book with friends.

(From Sarah: This is the eleventh guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

All this gets me to thinking that L.M. Montgomery portrayed groups—specifically friend groups—better than almost any author I can think of. Think for a moment of the Story Club of Avonlea or the scholars of Patty’s Place. What a joy it is to see young women in community actually getting along, supporting one another, having fun! Not primarily by demeaning or “taking down” anyone else, but simply by being their glorious selves, together. Isn’t it grand? And though we do see the Avonlea girls engage in some less-than-kindly gossip at the beginning of the Story Club chapter, they become kindlier midway through, almost as if turning those energies to creativity builds their bonds and brightens their outlooks. And it happens while “poring over” books and writing.

I’ve written about The Story Club and Patty’s Place in more detail here. But one thing that strikes me again and again is that these were girls who shared books. They passed them around and talked them over. Then they branched out and wrote stories and essays of their own, not just alone in the quiet of their rooms, but to be shared, together.

Even though Anne is a wee bit critical of the other girls’ writing styles at first:

“Ruby Gillis is rather sentimental. She puts too much love-making into her stories . . . Jane’s stories are extremely sensible. . . . Then Diana puts too many murders into hers. . . .” (Anne of Green Gables, Chapter 26)

The fact is that each girl tells us something about herself when she writes a story. We see Ruby Gillis’ and Jane Andrews’ personalities shine through, and we see a delightfully darker side to the sweeter-than-sweet Diana. We get to know them, and they get to know one another, through their writing and the books they find “fascinating” (Chapter 30). We see girls and young women who share their books and writing and imagination and creativity, and who enjoy each other’s company, together. What a marvelous gift L.M. Montgomery has given us with that portrayal.

Of course, Louisa May Alcott gave us a similar gift with the March girls, up in the attic writing their newspaper and playing “Pickwick” as they had once played Pilgrim’s Progress. They brought their favorite books to life, together, for one another and for us. But for Montgomery, it’s not just about family groups. It’s groups of neighbors and friends. And not just book groups, either. One of my personal favorites is the Avonlea Village Improvement Society, that little-discussed group of civic minded young folk, Anne and Gilbert included (in their pre-romance days), who pal around together while also trying to do some good in the world. There are many more examples, too: the Avonlea school set, the King orchard crowd of The Story Girl and The Golden Road, and the “chums” who gather in the Patty’s Place parlour. Did you know that in Anne of the Island, Montgomery uses the words “chum” or “chummy” twenty-two times? That’s a lot of good friendship. Friends and stories and fun. Together.

As much as I adore Jane Austen, and I do, I’m often ill at ease among her groups, particularly her female groups, because beyond the protagonist, you can scarcely find a friend. If you’re lucky, you get one good friend, usually a sister—a Jane or a Marianne—but the rest of the women are far from companionable. They range from competitive to silly to downright cruel. I don’t just mean an antagonist, a Josie Pye to vex a newly arrived Anne, but rather that all the women in an Austen group, save the one true friend, seem to function in enmity with our protagonist, and she with them.

But in much of Montgomery—all the Anne books, most of the Emily books, both the Story Girl books—the groups are friendly and “chummy.” Even the odd one out, as Anne herself was in the beginning, is still treated like one of the crowd. I find it comforting.

Perhaps I’m drawn to these depictions because they reflect my own experience of the world. As a bookish child, sometimes my life was more like an Austen novel. Many people seemed not to understand, and I found that I’d rather keep the company with myself, with a book-companion, or with one true friend, than spend my time among them. But as I grew, I found more and more people who liked the same things I liked, and who liked me as myself. You could say I came into my Montgomery era. With its advent, I had the good fortune of belonging to many wonderful groups: reading groups and writing groups, book groups and study groups, craft groups and cooking groups, friend groups and fan groups, and even Pokémon Go raiding groups. While I don’t have the rare skill for maintaining all the friendships from all the groups from one stage of life to the next, in my heart, I treasure all the groups. I remember each and every group member fondly. OK, maybe not quite all of them, but even those who seemed a bit Josie Pye-ish at the time mellow with memory. Truly, my experience with groups is far more Montgomery-ish than anything else. Few and far between are the Lydias or the Lucy Steeles, out for themselves no matter who it hurts, or even glorying in the barbs others may feel from the flick of their blade. The groups I recall are collegial and congenial, full of shared thoughts and laughter and goodness and kindness and a willingness to help each other do their best and be their best, both in quiet, homey places and out in the world. I loved them. I still do.

So, when I come to the The Story Girl, for example, and wander into the King orchard to find that mix of extended cousins and neighbors who drop by, listening to stories and telling stories, playing games and eating apples, talking about the past and thinking about the future, and mulling over the ways of the world with one another, it strikes a chord deep in my heart. For this is one of the truest groups of friends I have ever known:

“We had had brotherhood with wind and star, with books and tales, and hearth fires of autumn. Ours had been the little, loving tasks of every day, blithe companionship, shared thoughts, and adventuring.” (Chapter 32)

There it is: friendship. Not just the one friend, the Kindred Spirit, but also the groups of friends, the camaraderie, all bound together with books and trees and the great wide world. I have an essay coming out soon that talks about Montgomery and communities, but what I’m talking about here feels cozier than that somehow. Pals. Chums. Friends.

It seems to me that Montgomery is a master of book-friends. The characters within her books are great friends, to one another and to us. The friends in her books form groups to talk about books and stories and life. And when we, as readers, gather together to talk about her books, and bond over them, we become book-friends with one another. Montgomery creates book-friends for so many of us in so many ways. Those friendships grow with, because of, and alongside the ones in the novels. That, too, is a glorious gift to celebrate on L.M. Montgomery’s birthday.

And the best gift of all? We get to go back and join the old crowd, over and over again, as many times as we please, whenever we recall or reread. When we read in groups, we get to recreate that camaraderie for ourselves and one another. Each time we are welcomed back, whether to a Zoom group or a library, to the Patty’s Place parlour or to the orchard full of storied trees, it is as if we are being welcomed among friends. Because, of course, we are.

All quotations are from the Tundra editions of L.M. Montgomery’s novels.

Trinna S. Frever is a former English professor, current fiction writer, tenured independent scholar, University of Michigan alum, and avid Montgomery fan. Frever’s work, whether fictional or scholarly, explores intersections between books, oral storytelling, music, dance, painting, film, handicraft, folklore, and our ever-expanding concepts of “text” and “story.” She has presented at eleven L.M. Montgomery conferences on Prince Edward Island (sometimes via Zoom), published several essays on L.M. Montgomery, taught the University of Prince Edward Island’s signature course on L.M. Montgomery, and is the creator of #lmmontgomerymonday on Instagram. Her current book project with Kate Scarth, Your LMM Story: The World of L.M. Montgomery and Her Fans (anticipated 2026/2027), collects stories from Montgomery readers to gain insight into Montgomery’s gifts to the world. Originally from Michigan and currently living in Florida, Frever is often drawn to books that feature forests and shores. Learn more at trinnawrites.com. You can find Trinna on Instagram @trinna_writes.

I took the photos in June, on a hike to Greenwich Beach in Prince Edward Island National Park.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “L.M. Montgomery and the Lucky Cat,” is by Susannah Fullerton.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them.

Can’t all Canada agree to like Montgomery (except her poetry)? by Audrey Loiselle

An Emissary of Laughter: L.M. Montgomery and the Saving Grace of Humor, by Liz Rosenberg

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Trinna S. Frever 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 24, 2024

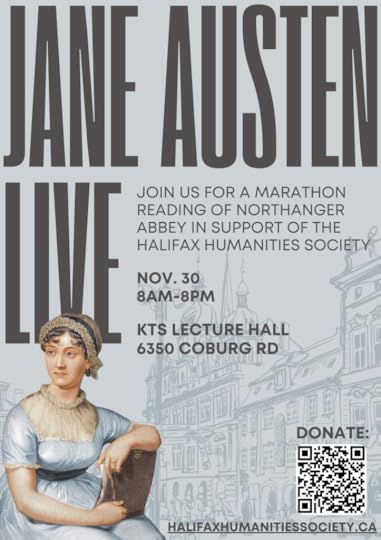

A Northanger Abbey Marathon

Next Saturday, November 30th, teams of readers will participate in a twelve-hour event called “Jane Austen Live! A Marathon Reading of Northanger Abbey,” in support of the Halifax Humanities Society. If you live in or near Halifax, Nova Scotia, you might like to attend in person, at the University of King’s College (KTS Lecture Hall, 2nd floor of the New Academic Building, 6350 Coburg Rd.); if you live further away you could watch the livestream on their YouTube channel. The event is free. Donations to the Halifax Humanities Society are welcome at the door or online.

The Halifax Humanities Society is “a non-profit organization committed to offering free, non-credit, university-level humanities education to adults living on low incomes in the Halifax Regional Municipality. Students from a range of ages and backgrounds come together with volunteer university professors to study the great works of Western philosophy, literature, political theory, theology, and art, at no cost whatsoever to students. These classes can be life-changing, and are only possible with your support.”

You can find out more about their programs here. Please join me in supporting this important work!

The Society invites everyone to “join us in the illustrious halls of the University of King’s College to hear of real scandal, imagined murder, and to learn what exactly is in that mysterious cabinet.”

In 2017-18, I hosted an online celebration for the 200th anniversary of the publication of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. You can find all the contributions listed here.

The first half featured guest posts on Northanger Abbey by Deborah Barnum, Peter Sabor, Lynn Festa, Serena Burdick, Kate Scarth, Lisa Pliscou, Leslie Nyman, Gisèle M. Baxter, Theresa Kenney, Judith Thompson, Margaret C. Sullivan, Sara Malton, Lyn Bennett, Saniyya Gauhar, Mahlia S. Lone, Laaleen Sukhera, Deborah Knuth Klenck, and Ted Scheinman.

One of the contributors to the second half of the series, with a guest post on Persuasion, was Mary Lu Roffey Redden, former director of Halifax Humanities: “Three Generations in Search of Anne Elliot.”

On November 30th—L.M. Montgomery’s 150th birthday—I’ll be in Prince Edward Island, and I regret that I won’t be able to attend the Northanger Abbey marathon in person. But I’ll be there in spirit, and I’ll open up my copy to read a few passages.

“And what are you reading, Miss——?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language. (Chapter 5)

Copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 22, 2024

Can’t all Canada agree to like Montgomery (except her poetry)? by Audrey Loiselle

Last June, I attended the Lucy Maud Montgomery Institute’s biennial conference at the University of Prince Edward Island for the fourth time, having previously participated once as an audience member and thrice as a presenter, so infectious is the atmosphere at this academic yet convivial event. For the first time, though, I drove there, leaving the Eastern Townships of Québec at dawn to cross the Canadian-American border into Maine and then back into New Brunswick before cruising along the Confederation Bridge and heading into Charlottetown. When I emerged from the car after ten hours, I felt both exhilarated and exhausted; I couldn’t believe just how close and how far Maud’s land turned out to be!

Once more, with (even more) feeling : PEI 2024

(From Sarah: This is the tenth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

This contradiction in terms mirrors my long-term relationship with the venerable English-Canadian 20th-century writer as a millennial French-Canadian reader and translator. For my rapport with Montgomery has demanded constant reassessment and reframing throughout the years, as I transitioned from the transfixed teen who repeatedly read her (mostly) cheerful fiction in French translation to the college student who tackled her far more depressing private writings and eventually found my way into the literary and scholarly circles devoted to her. Meeting intellectuals who saw Montgomery and her works as complex entities worthy of study was instrumental to my decision of making her and her semi-autobiographical Emily trilogy the focus of my master’s thesis in literary translation at a francophone institution. However, I found myself there surrounded by people who tend to disparage Montgomery on principle, because they associate her—not unlike Jane Austen—with a genre accused of excessive banality and sentimentality, but also, and more grievously, with an “English” sense of superiority which stoked anti-French prejudices in a (hopefully) bygone era in Canada.

With fellow housemates and scholars. From left to right: Irina Levchenko, Susan Erdmann, Leïla Matte-Kaci, me (Audrey Loiselle), and Laura Leden.

My co-students’ and professors’ reservations are not entirely unfounded. Montgomery was not above resorting to tired plots or abusing purple prose at times, especially in the short stories which she peddled to mass-market magazines and airily dismissed as “potboilers.” And though Kevin McCabe posited that “[w]hen viewed in the context of her times, Maud’s racism and xenophobia are not earth-shattering,” Montgomery undeniably held classist views and did not paint French-Canadian characters in a particularly flattering light in her books. In the Anne and Emily series, Acadians from the “Creek” or the “Pond” briefly feature as ungainly farmhand or household help, spreading gossip and germs throughout respectable Anglo-Canadian homes and communities. Though some shine briefly as bearer of good news (Pacifique Buote in Anne of the Island), sympathetic listener (Judy Pineau in The Story Girl), or gifted fiddler and storyteller (Lazarre in Magic for Marigold), uniformly sunburned and black-eyed Acadians are mostly met with mistrust and contempt in her novels. There is overall little to counter Caroline E. Jones’ criticism that Montgomery’s French-Canadian characters are “flat constructs . . . never written as round, well-developed individuals who contribute to the storyline and . . . entirely lack[ing] cultural and symbolic capital.”

Despite these considerable drawbacks, I persisted in believing and in wanting to demonstrate that modern French-Canadian readers and translators ought to pay Montgomery some attention. I plied my unfortunate director, who probably wished I were working on fresher, less problematic voices, with weighty articles like Mary Henley Rubio’s seminal Subverting the Trite, to wear down her reticence. I stooped to embarrassing emotional pleas to get fellow students to “try anything from Montgomery, really” (save her poetry—that would have been both cruel and counterproductive). One eventually caved in—possibly to stop me from bringing up the topic at every party—but insisted on being given a specific title. I picked A Tangled Web, as it ranks among my personal favourites, but also because “it is a novel about negotiating changes in perspective,” as UPEI’s former president and L.M. Montgomery Institute cofounder Elizabeth Epperly aptly commented at the 2024 conference focusing on L.M. Montgomery and the Politics of Home.

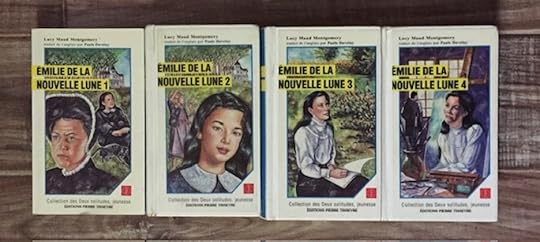

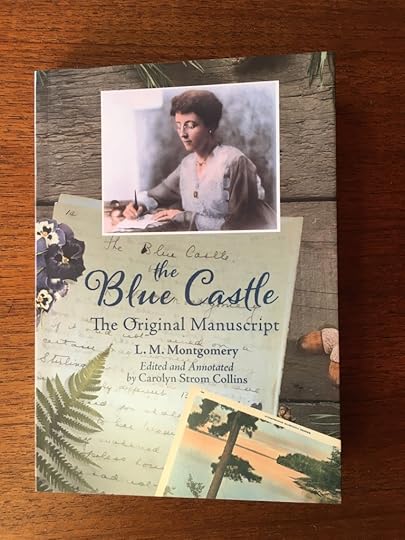

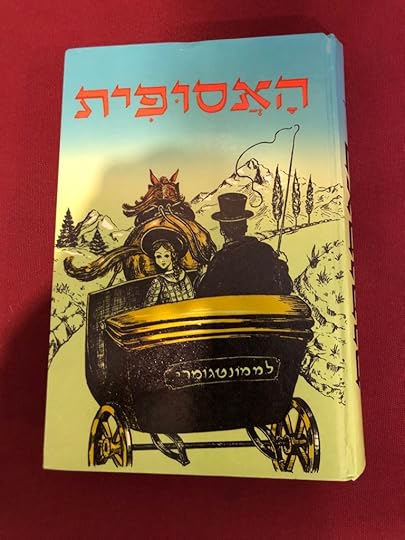

The French-Canadian translation of the Emily trilogy by Paule Daveluy