Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 8

October 4, 2024

Happy October!

Hello and happy October to all of you! Like L.M. Montgomery’s heroine Anne Shirley, I’m “glad I live in a world where there are Octobers.” Like Jane Austen’s Marianne Dashwood, I’ll be admiring dead leaves pretty much every time I go out for a walk.

Last week, I visited Herring Cove Provincial Park, one of my favourite places in Nova Scotia, and I want to share this beautiful view with you.

I hope you enjoyed the “Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” As I mentioned last time, Kate Scarth has written a fun guest post about “Marianne Dashwood and Anne Shirley, #KindredSpirits,” which I’ll share here on October 30th, the anniversary of the date Sense and Sensibility was published. Maybe by then I’ll have some good photos of maple branches (in honour of Anne) and dead leaves (in honour of Marianne).

And then in November, we’ll be celebrating the 150th anniversary of L.M. Montgomery’s birth, with a series of guest posts from Gisèle Baxter, Mary Beth Cavert, Kerry Clare, Lesley Clement, Susannah Fullerton, Trinna Frever, Sue Lange, Audrey Loiselle, Naomi MacKinnon, Hughena Matheson, Nili Olay, Liz Rosenberg, Logan Steiner, and Marianne Ward.

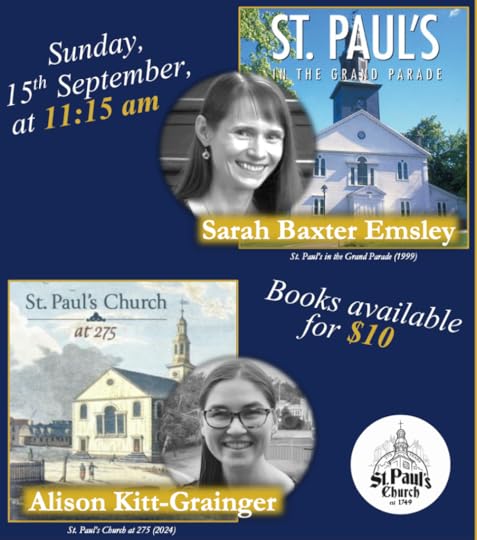

On September 15th, I had the pleasure of signing copies of my book St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade—written for the church’s 250th anniversary in 1999 and published by Formac—at a celebration of the 275th anniversary. My father took this photo of me with the Rev’d Canon Dr. Paul Friesen, Rector of St. Paul’s, and Alison Kitt-Grainger, co-author of St. Paul’s at 275:

My daughter took this photo of me outside St. Paul’s:

I was thrilled to receive an invitation to speak about the history of St. Paul’s in the Evenings @ Government House fall season (November 5th). It’s been fun to sort through images for the slideshow that will accompany my talk.

Later this month, I’ll be speaking at the Jane Austen Society of North America AGM in Cleveland, Ohio. My talk is called “‘She placed her bonnet on his head & ran away’: Stealing Sources and Avoiding Consequences in Jane Austen’s Fiction.” Following the AGM, the essay will be published in Persuasions/Persuasions On-Line. I haven’t been to a JASNA AGM for several years and I’m looking forward to seeing some of you there!

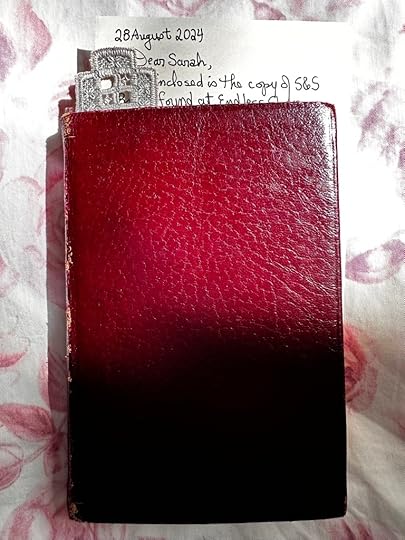

Sandra Barry, who wrote a lovely guest post in August about rereading Sense and Sensibility, sent me the Collins’ Clear-Type Press edition of the novel that she discovered at Endless Shores, a bookstore in Bridgetown, Nova Scotia. I was surprised and delighted to find the book in my mailbox a few days after her post was published. She enclosed with it a beautiful hardanger work bookmark made by her sister Brenda Barry. (I wasn’t familiar with the term hardanger and Sandra explained that it’s a Norwegian open work needle art.)

A few things I’d like to recommend:

I enjoyed reading about the Bookshop Band and their new album, “Emerge, Return” in this article by Elisabeth Egan in the New York Times: “How Far Will a Reader Go to Hear Songs Inspired by Books?” I first heard the Bookshop Band in 2019, when they were invited to perform in Halifax to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Bookmark, one of my favourite bookstores.

The band—Beth Porter and Ben Please—writes and performs songs inspired by books. Sounds wonderful, doesn’t it? Here’s the link to “Red & Black,” a song inspired by Alistair MacLeod’s award-winning and bestselling novel No Great Mischief, recorded at Bookmark’s Charlottetown, PEI shop in 2019.

Shawna Lemay has started a Poetry Club on her fabulous blog, Transactions with Beauty. She recently wrote about my friend Margo Wheaton’s The Unlit Path Behind the House and Rags of Night in Our Mouths and I love what she says about Margo’s poetry: “It’s not flashy but it’s quiet and true and imagine having that to refer to in this world of ours which is often too loud and fake and garish and without integrity or even an understanding of what that looks like” (“Poetry Club: Wheaton, Tait, Parker”).

When I visited Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey several years ago, I remember wondering why the memorial to Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë spelled their last name “Bronte.” I was glad to read that .

In a recent issue of her newsletter, Noted, Jillian Hess wrote a celebration of “notes that are not aesthetically pleasing,” in which she quotes Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s description of one of his notebooks as a “Fly Catcher: or Day-Book for impounding Stray Thoughts” and George Eliot’s description of the notebook she kept while writing Middlemarch as a “Quarry.” Do any of you keep notebooks? I’ve done so for many years—maybe I’ll write about them here sometime.

I’ll leave you with a few recent photos: evening light on the Halifax Commons, a bicycle and marigolds at a café in Herring Cove, and asters in an empty lot in my neighbourhood.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

A Calendar for Sense and Sensibility, by Ellen Moody

From the forthcoming book Living with Jane Austen, by Janet Todd

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend, and if you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future posts.

Copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

September 21, 2024

A Calendar for Sense and Sensibility, by Ellen Moody

More years ago than I care to remember, I set about drawing from the version of Sense and Sensibility that Jane Austen published in 1811 the underlying calendar (as I called it) that I still believe helped Austen to structure her written manuscript letters for an epistolary novel at first called Elinor and Marianne. In his 1924 first scholarly edition of Jane Austen’s novels, R. W. Chapman had worked out “chronologies,” some in the form of downright calendars, for five of the six seemingly finished novels (all but Sense and Sensibility), and placed them in the back of each book as appendices. He was among the first to be aware of or assert in print that she had used almanacs to give an illusion of calendar and psychological time by careful explicit pacing to readers as they read which felt comparable or proportionate to their own experiences of time in their objectified and subjective experiences of life.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-ninth, and last, guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th. And here we are, at the end of summer, at least in this part of the world. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . Many thanks to all who contributed to the series by writing guest posts, reading, and joining the conversations in the comments on the website and on social media! I hope you’ll join me for a celebration of L.M. Montgomery’s 150th birthday in November.)

I conjectured that if I did this in detail, noting carefully the day by day, sometimes hour by hour, and weekly and monthly tracking Austen keeps up (it might seem obsessively), I would find these calendars to be more or less internally consistent and discover truths about the novels no one else had noticed because they had not drilled down (or geologized) the seemingly unimportant minutiae of these books. I did discover new truths and confirmed suppositions about the books that other readers had long asserted as felt truth. I began with Sense and Sensibility because Elinor Dashwood had long been my favorite of Austen’s heroines, and it is her consciousness which is the fundamental basis of the book. In addition, Chapman had neglected to do any chronology. My preconceptions included five years of study for a dissertation on the art of epistolary narrative and allusion as practiced by Samuel Richardson in his transformative influential Clarissa and Sir Charles Grandison, and (much less intensively) as practiced by a few of his French and English followers (Rousseau, LaClos, Diderot; Francis Sheridan, Frances Burney, Charlotte Smith). Among my aims was a publishable paper which I succeeded in achieving in Philological Quarterly 79 ([2000], 233-66).

Readers can read this first calendar here (as it appeared in print, but with some changes, e.g. added explanations).

It’s included in the area of my website that I came to call Time in Jane Austen: A Study of her Uses of the Almanac.

As you will see (if you have clicked on the second link), eventually I studied in the same minute detail the other five seemingly finished novels, and three of the four more mature unfinished novels, The Watsons, Lady Susan, and Sanditon.

Among my discoveries was that both Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice were originally written as epistolary narratives; that Mansfield Park is the product of two related stories about the same characters written at disparate times (it melds, somewhat awkwardly, two almanacs a few years apart in time), one section of which was semi-epistolary; and that Persuasion was intended to have a third volume. For me unexpectedly, and then increasingly astonishingly, I also discovered a phenomenon across all these seven texts (omitting Northanger Abbey and Sanditon) a repeated phenomenon I’ve never had the nerve to try to publish an essay about in an academic journal—because online I quickly encountered dismissive laughter. All seven explicitly make days or evenings where humiliating public events or overt losses happen or were to happen (in the case of Persuasion’s third volume) a Tuesday.

I have room to specify and link to one of my blogs demonstrating this phenomenon just for Sense and Sensibility. Here it is spelt out, and the reader may also observe how carefully Austen kept probable time in her novels: “Tick Tock Tick Tock: important Tuesdays or Austen and epistolary obsessions.”

If you have gone over to look you will have seen that Sense and Sensibility has three such Tuesdays, and in two cases the day of the week is cited specifically. The day Willoughby left his card is referred to by him as “last Tuesday” on the night he snubs Marianne at the assembly ball. The important statement for the chronologist is Willoughby’s “I did myself the honour of calling in Berkeley-street last Tuesday . . . My card was not lost, I hope” (italics added), and my calendar bears out that the morning after of the terrible letter (again specified by Austen) is a Wednesday at dawn (“The next day . . . a cold, gloomy morning in January” (Volume 2, Chapters 6 & 7). So the harrowing scene in front of a large public is a second Tuesday. Then the day Elinor is humiliated and mortified by Mrs. Ferrars in front of the Steeles, Dashwoods, Brandon, Mrs. Jennings and whoever else was at Mrs. Dennison’s dinner party is called “the important Tuesday” (Volume 2, Chapter 14).

The year these dates are all possible in is 1797-98, the year Cassandra cited as the one Austen completed Sense and Sensibility in.

A slight digression may be needed to respond to incredulity: I am now confining myself to just those dramatic and linchpin Tuesdays (sometimes again labelled by the narrator as “the important Tuesday”), which most readers of Austen will remember and I will be briefer (just general references, no longer quotations). The first I’ll call attention to is Tuesday, November 26th (so specified by Austen), the evening of the Netherfield ball where Elizabeth feels humiliated by her family members’ behavior, which behavior Darcy singles out as objectionable to him when he first proposes marriage (Pride and Prejudice). In Mansfield Park: we are told that Fanny and William arrive in Portsmouth on a Tuesday night which I make out to be February 7th (the year is either 1809 or 1797, the latter being Walton Litz’s choice, the former Chapman’s); that night begins the long pivotal and medicinal lesson Sir Thomas meant Fanny to have; she is mortified, snubbed by her family (as after all she is not “theirs” any more). We are told that the night of Mrs. Frazer’s party, which is so fatal to Henry Crawford and Maria Rushworth, is a Tuesday (which I worked out to be March 14th). We do not see the scene; we must piece it out from the letters, but when Maria snubbed Henry and he was humiliated, he determined to make her yield to him once again. This precipitates the final crisis and denouement of the novel.

For Emma I’ll cite only the night of the Coles’ party which is said to be a Tuesday more than once: Emma makes a fool of herself and could have hurt Jane’s reputation profoundly by telling Frank a piano which has arrived without explanation is a gift from Mr. Dixon, Jane’s friend and benefactor’s husband; Emma is herself mortified by a comparison she feels will be made by the assembly of Jane’s superior piano-playing to her own. Jo Modert has explained “a hidden calendar game” in Emma and found the piano arrived on Valentine’s Day (the novel uses the almanac for 1814-15). Last citation: the opening sentence of The Watsons tells the reader the ball at which Emma sees Mr. Howard for the first time and dances with little Charles was a Tuesday, October 13th: the year may be either 1801 or 1803 or 1807; it matters not from the point of view of Tuesday. Emma asks young Charles Black to dance, rescuing him from humiliation in the way Mr. Knightley rescues Harriet Smith on the night of the Crown Inn Ball (Emma).

If you would like to check volume, chapter or page reference, return to my paper or see “A Pattern: A preliminary sketch: notes towards a paper on Tuesdays.”

I have been asked why no one has found this pattern of Tuesdays but me. I have asked people reading my timelines since not to take credit for it, though they may use the calendars and many have and thanked me in print. My response is until the 20th century no one was looking for this, i.e., no one was studying these novels in this kind of granular detail, and that since the mid-20th century various scholars and readers have uncovered more or less consistent timelines, cited the years a novel’s events occur in, and argued for other perhaps more socially acceptable features than a persistent remembered trauma turned into a secret joke in the different books. When I’ve been asked to explain it, people seem to want me to cite a source text; I have come up with a couple; for example, Richardson’s heroine Clarissa was raped between a Monday night and early Tuesday morning (“And now Belford, I can go no farther. The affair is over. Clarissa lives” is dated “Tuesday morn”), but I resist this explanation and other textual instances because in all of them the whole feel and tone of these texts is so different from any of the Austen uses which have an idiosyncratic or characteristic likeness.

To return to Sense and Sensibility I believe that it was Austen herself who in her life had an experience of public social humiliation and private loss like those we see in Sense and Sensibility and her later published fiction. I am convinced that one of many features central to the power of her texts is she uses her creative and artistic gifts to deal with her life’s traumas through laughter (she does this in her letters too). She followed a disciplined routine (often repetitive) of writing and rewriting these exquisitely precise texts, in which (say the proverbial ninth draft) she found curative release. One of my conference papers argues explicitly for this in the case of her wildly antipathetic joking over women’s aging, agons and deaths in childbirth (“The Depiction of Widows and Widowers in the Austen Canon” at the University of Delaware, November 16-18, 2014).

Why did she choose Elinor and Marianne or Sense and Sensibility for the one text she was determined to publish? Why begin there? She had other manuscripts ready for revision. I suggest because the characters of Elinor and Marianne were both close to her heart (as was recognized by family members in verse). Elinor’s many internal soliloquies, especially after Lucy tells her that she, Lucy, and Edward have been engaged for four years and produces concrete evidence of a relationship mirror closely an early traumatic experience of emotional sexual awakening and some public social shock or humiliation. The private trauma is re-enacted outwardly by Marianne at Cleveland Park. The social loss or degradation or deprivation need not have been limited to a single day. When the Dashwood family are threatened by homelessness Austen is reconfiguring her experience of sudden powerless dispossession (recorded in her letters) when she was forced to leave Steventon for Bath. The famous second chapter of the novel in which Fanny Dashwood easily persuades her husband not to keep his promise to his father was written later in time, one of the revisions Henry Austen was referring to when he said his sister’s novels were “all gradual performances.”

That these experiences in her twenties mattered strongly to Austen and affected the way she responded to her life ever after may be seen in the similarities and parallels across the novels (often remarked upon by readers, beginning with the unsympathetic caustic Q.D. Leavis [in Scrutiny]) and in Austen’s persistent return to a primal Tuesday turned into a hidden joke as a way of coping with seared memories.

Ellen Moody has a PhD in English Literature, awarded in 1979. She has been teaching since 1972 in senior colleges (Queens and Brooklyn Colleges in NYC, American and George Mason University in Virginia) and (starting age 66-67) college style programs for retired adults attached to the last two colleges. She’s published two books, numerous papers and reviews, and more informal essays in academic and peer-edited journals, books, and newsletters. Her first specialty was the long 18th century, but over the years, she’s concentrated on some individual authors (i.e., Jane Austen, Anthony Trollope), women’s studies and literature, translated poetry, edited French novels (e.g. Isabelle de Montolieu’s Caroline de Lichtfield) and branched out to the 19th and 20th century and film studies. She’s been very active on the Internet since 1995, and maintains an academic website and two literary blogs, moderates two listservs, and joins in with online readers on a couple of social media sites to read and to write about books together. She enjoys virtual as well as in person conferences and classes very much. She is a widow, with two adult daughters, and loves her pet companions. The photos above are from Ellen’s garden.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future blog posts.

As I mentioned above, we’ll be celebrating L.M. Montgomery’s 150th birthday with another series of guest posts that will run through the month of November: “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.”

The first post in the new series will provide a link between Austen and Montgomery: Kate Scarth, Chair of L.M. Montgomery Studies at the University of Prince Edward Island, has written a fun and fabulous guest post called “Anne Shirley and Marianne Dashwood, #KindredSpirits.” Watch for Kate’s post on October 30th, the anniversary of the date Sense and Sensibility was published. I’ll probably write another blog post of my own before that. See you in October!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

On the Road with Elinor and Marianne, by Cheryl Bell

From the forthcoming book Living with Jane Austen, by Janet Todd

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 20, 2024

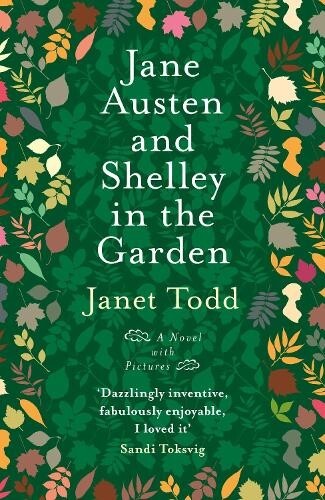

From the forthcoming book Living with Jane Austen, by Janet Todd

To celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth, I wrote Living with Jane Austen for Cambridge University Press. Part Austen commentary and part academic memoir, it aims to show why Austen matters to us now and how our understanding of her work changes at different cultural moments. As I wrote new chapters or revisited old talks, I was repeatedly struck by how much sterner and colder Sense and Sensibility is compared with the other novels.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-eighth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will come to an end tomorrow. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Reading with Mary Wollstonecraft

Throughout my book I shadowed Jane Austen with another of my literary heroines (whose biography I wrote many years ago), Mary Wollstonecraft. Before she composed her great Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she reviewed novels for the new radical journal, the Analytical Review. In these pieces she inveighed against fiction, usually “by a Lady,” aimed at susceptible female readers who were persuaded to believe in the unrealistic fantasy of combined power, riches, large house, and fulfilled desire all delivered to them by a handsome young man. Seeing Austen through Wollstonecraft’s imagined eyes, I reacted more severely than I might otherwise have done to Pride and Prejudice as a kind of “property porn.” Gleefully Elizabeth imagines herself “mistress” of Pemberley. Wollstonecraft exclaimed, “Oh why is virtue always to be rewarded with a coach and six”—or a great estate? She called such a romantic denouement a “whipped syllabub” (a common dismissive term occurring also in Austen’s writing). She might have damned Pride and Prejudice had she not read closely this extraordinary work.

By contrast, in Sense and Sensibility there’s no question of Elinor becoming mistress of a great estate, just an indifferent parsonage, and she eschews the fantasy of property. Hers is a more difficult desire: “I will be mistress of myself” (Volume 3, Chapter 12). In The Rights of Woman Wollstonecraft held firmly to the need for her sex to know themselves, to be rational, to judge with consideration—as Elinor supremely does—and not to believe, with Marianne, that if something feels good, it’s right. But if a great estate is not required for well-being, a modest competence is. Elinor consoles Marianne for the loss of desirable Willoughby by noting: “Had you married, you must have been always poor” (Volume 3, Chapter 11). In Mansfield Park the youngest Ward sister is romantic: she weds Lieutenant Price of the marines with no consideration of income and is reduced to relative poverty.

Sickness

Because of the personal element in my book (and given my age and array of ailments), I spent much time on mental and physical illness—nerves, colds, bile and so on. Austen often comments on the confusion of mental and physical that so worried the period. One example is the comic proposition of salving a lovelorn heart with wine. In Mansfield Park Edmund presses Madeira on headachy Fanny whose problem is thwarted desire for himself. In Sense and Sensibility Mrs. Jennings suggests expensive Constantia wine (once used for her dead husband’s “cholicky gout”) to soothe Marianne’s lovesickness. A little foolish perhaps, but, when Marianne has a respite during her severe self-inflicted illness, Elinor too administers “cordials.” Elinor and Mrs. Jennings have the support of the early medical writer George Cheyne who, in his Essay on Health and Long Life, wrote that for women of “weak nerves . . . the only Remedy for them, is drinking Bristol Water and red Wine, with a low and light Diet.”

Ailments can of course be primarily physical and they’re most salient in Sense and Sensibility, especially in the inset story of the two Elizas related in different tone from the dramatized part of the novel. This describes Colonel Brandon’s beloved suffering a life of misery and degradation from an initial fall into “vice,” then contracting consumption (tuberculosis), then dying. When (in rather unnerving echo) young Marianne falls ill after what starts as a chill from sitting in wet stockings, some of the earlier anxiety touches this later sickness. She ends with a dangerous “putrid fever.” Her illness becomes a rite of passage to reform:

My illness . . . had been entirely brought on by myself. . . . Had I died,—it would have been self-destruction . . . I wonder at my recovery,—wonder that the very eagerness of my desire to live, to have time for atonement to my God, and to you all, did not kill me at once. (Volume 3, Chapter 10)

Marianne changes within a Christian framework. So too does Tom Bertram in Mansfield Park: “He was the better for ever for his illness. . . . He became what he ought to be” (Volume 3, Chapter 17). Although there’s no mention of God in the later passage, the complete reformation occurs in a novel tilting a little towards evangelical Christianity. Sudden conversion is rare in Austen and most peripheral characters are like Lydia in Pride and Prejudice—following her brush with disaster: “Lydia was Lydia still” (Volume 3, Chapter 9). Marianne’s near-death experience invokes God; it teaches her right thinking and directs her to a more sensible, if less dashing, choice of life partner. But, unlike Tom Bertram’s, her good resolutions are treated with some irony: they are characteristically extreme.

After Sense and Sensibility, Austen will not be so melodramatic again and perhaps there’s a mocking self-reference to this earlier novel in Emma. Always on the lookout for threats to the body, finicky Mr. Woodhouse is troubled about wet stockings. He fusses over Jane Fairfax and her rainy walks to the post office: “My dear, did you change your stockings?” he enquires (Volume 2, Chapter 16).

Weather

As I moved through topics and decades of criticism I touched on language, allusions, social embarrassment, unruly bodies—and death. I discussed nature too, not in the wonderfully detailed way Hazel Jones has done in a recent blog post for this series, but mainly as spectacle and prompt for reverie. Above all I treated it through “weather.”

Weather is featured in every Austen novel but my favourite intrusion is Lady Middleton’s comment on rain in Sense and Sensibility. It spares Elinor further teasing about a lover with the initial “F”:

Most grateful did Elinor feel to Lady Middleton for observing at this moment, “that it rained very hard,” though she believed the interruption to proceed less from any attention to her, than from her ladyship’s great dislike of all such inelegant subjects of raillery as delighted her husband and mother. The idea however started by her, was immediately pursued by Colonel Brandon, who was on every occasion mindful of the feelings of others; and much was said on the subject of rain by both of them. (Volume 1, Chapter 12)

Quotations are from the CUP editions of Jane Austen: Sense and Sensibility, edited by Edward Copeland (2006), Mansfield Park, edited by John Wiltshire (2005), Pride and Prejudice, edited by Pat Rogers (2006), and Emma, edited by Richard Cronin and Dorothy McMillan (2005).

Janet Todd is a retired academic; her last position was as President of Lucy Cavendish College, University of Cambridge. The photos above were taken in her garden.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future posts, including the final guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” Tomorrow’s post, “A Calendar for Sense and Sensibility,” is by Ellen Moody.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

On the Road with Elinor and Marianne, by Cheryl Bell

The Challenge of Interpreting Character and Action in Sense and Sensibility , by L. Bao Bui

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 17, 2024

On the Road with Elinor and Marianne, by Cheryl Bell

In her introduction to Virginia Woolf’s How Should One Read a Book?, Sheila Heti says that “A book’s watery shape is formed by its movement—the progress the characters or the narrative took, which was a progress we lived through while reading it, and which then solidifies into a single, continuous episode, no matter over how many sessions we read the book” (Laurence King Publishing, 2020).

The shape of Sense and Sensibility that remains for me after reading it is Elinor and Marianne Dashwood’s progress through the book, from Norland Park to Barton, and from Barton to London and back. In the great tradition of literary journeys, there are difficulties and revelations along the route, but in the end, there is maturity, self-knowledge, and understanding.

A February view of the garden at Chawton Cottage, Jane Austen’s House Museum, from Jane’s bedroom window

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-seventh guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. The last post will be on Saturday. [For me, as for many others, “September is a summer month.”] You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

The journey begins when the Dashwood family moves from their family home in Norland Park in Sussex to Barton in Devonshire. Elinor and Marianne’s father has died, their elder half-brother has inherited the estate, and Mrs. Dashwood and her three daughters soon feel unwelcome there. When their cousin Sir John Middleton offers them a modest but comfortable cottage on his estate in Barton, they accept. For Elinor, we learn that leaving their family home also means leaving behind Edward Ferrars, her sister-in-law’s brother, with whom there appears to be a growing mutual regard.

Their departure is melancholy, but the arrival of the Dashwoods in Barton in early September has the feel of a fresh start. The weather is fine, the cottage has high hills behind it, and there is a wonderful view of the valley from the windows at the front. No sooner are they settled than Sir John begins to introduce them to new people, including his widowed mother-in-law Mrs. Jennings, and his friend Colonel Brandon, who is also clearly taken with Marianne. Elinor deems him to be a sensible man, but Marianne declares him too old—he is thirty-five—and too dull to be of interest.

Jane Austen’s House Museum

Colonel Brandon stands in sharp contrast to the dashing Willoughby, who literally sweeps Marianne off the ground—if not her feet—after she falls while walking. “Exactly formed to engage Marianne’s heart,” Willoughby visits every day and they read and talk and sing together. Although he is popular with all the Dashwoods, Elinor has some concern about Willoughby’s “want of caution” (Volume 1, Chapter 10). After an intense few weeks, during which there is wide speculation about an engagement, Willoughby unexpectedly arrives at the cottage one day to say good-bye and then abruptly leaves for London, leaving Marianne with many unanswered questions.

Elinor also experiences heartache at Barton. Edward is slow to visit the Dashwoods, and when he does, Elinor finds him reserved and in low spirits. Then, through Mrs. Jennings, Elinor and Marianne meet the Miss Steeles, Anne and Lucy, who quickly reveal themselves to be lacking in education, grace, and tact. When Lucy confesses to Elinor that she and Edward have been secretly engaged for some time, Elinor remains outwardly composed yet conceals “an emotion and distress beyond anything she had ever felt before” (Volume 1, Chapter 22).

Mrs. Jennings invites Elinor and Marianne to accompany her to London where she has a winter home. Elinor initially demurs. Mrs. Jennings has not made a favourable impression on either sister with her teasing about romantic “attachments” (Volume 1, Chapter 8) and insensitive questioning of Colonel Brandon regarding the contents of a letter he receives (Volume 1, Chapter 13). However, Marianne’s “eagerness to be with Willoughby again” (Volume 2, Chapter 3) finds them accompanying Mrs. Jennings on the three-day journey by carriage.

In London everything feels concentrated: the geography, the crowded parties, and the talk of marriages and money. For the Dashwood sisters, the revelation of two parallel engagements adds to the intensity of their time in London.

Willoughby assiduously avoids meeting the Dashwoods in London until he and Marianne encounter one another by chance at a party. He treats Marianne in a cold and formal manner and afterwards writes to tell her he is engaged, which leaves her feeling upset and badly used. When the engagement between Edward and Lucy is revealed to Edward’s sister, there is a terrible scene. With the secret out, Elinor finally speaks to Marianne, who is shocked that Elinor has known about the engagement for four months—months in which Elinor has cared for Marianne during her misery. Uncharacteristically, Elinor pours out her unhappiness and her struggle to retain her composure of mind. “If you can think me capable of ever feeling—surely you may suppose that I have suffered now,” she tells Marianne, who finally begins to understand that she is not the only one who suffers (Volume 3, Chapter 1).

After two months in London, Elinor and Marianne are happy to return to Barton. Along the way, they stop at Cleveland in Somerset, the home of Mrs. Jennings’s daughter and son-in-law. The house is on a “sloping lawn,” surrounded by a variety of trees, and has an extensive pleasure-ground. In this bucolic green world, Marianne falls dangerously ill, first with a cold and then a “putrid infection” after walking in the wet grass of the grounds (Volume 3, Chapter 6).

This is the crisis that triggers the process of resolution. As Elinor sits by her sister’s bedside while Colonel Brandon goes to Barton to bring back Mrs. Dashwood, Willoughby unexpectedly arrives. He has heard from an acquaintance in a London theatre that Marianne is seriously ill. His aim is to offer “some kind of explanation, some kind of apology, for the past.” He reveals to Elinor that he now has a “better knowledge of my heart” and was never “inconstant” to Marianne. Like Elinor, he must now live with a love he cannot indulge (Volume 3, Chapter 8).

The remaining step in the journey is the return to Barton where resolution is complete. As Marianne recovers from her illness, she is chastened to recognize the harm she has done to herself and the distress she has caused others. She also begins to feel more than gratitude to Colonel Brandon. It is discovered that Lucy Steele has married Edward’s brother, leaving Edward free to propose to Elinor. As in a Shakespearian comedy, the individuals have travelled far, but now there are weddings and the natural order readers have glimpsed from the beginning of the book is achieved. Even Willoughby, who feels a pang when he hears of Marianne’s wedding, “lives to exert, and frequently to enjoy himself” (Volume 3, Chapter 14).

Sheila Heti uses the word “progess” to describe the movement through a book. It feels particularly apt when applied to Sense and Sensibility, neatly encapsulating as it does both Elinor and Marianne’s physical passage through the novel and their emotional and psychological growth, which take place in tandem. Because they have undergone this process, they—and we as readers—are confident in their decisions and their future happiness. It is a satisfying end to the journey and remains that way as it solidifies in the mind.

Quotations are from the Penguin edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited and with an introduction and notes by Ros Ballaster (2014).

Cheryl Bell lives in Halifax with her husband Duncan and their three grown-up children are regular visitors. She is the communications manager for the Faculty of Dentistry at Dalhousie University and a freelance writer/editor. She also writes book reviews for the Literary Review of Canada Bookworm newsletter.

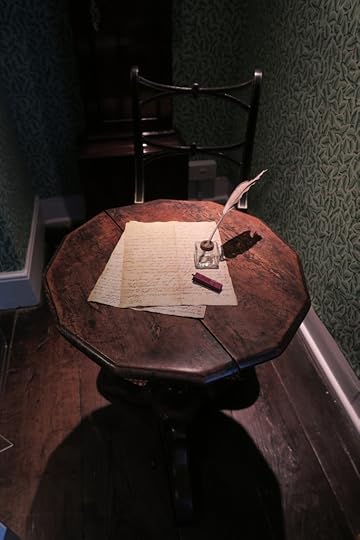

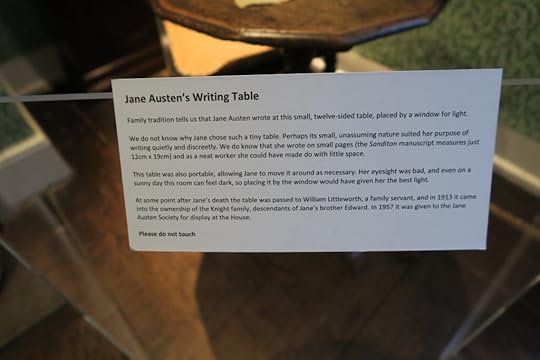

In February 2024, Cheryl and Duncan visited Chawton Cottage for the first time, where they saw Jane Austen’s tiny writing table and realized that Austen, her sister Cassandra, and their mother moved to Chawton under circumstances similar to the Dashwoods’ arrival in Barton. Cheryl says the tea room opposite Chawton Cottage, Cassandra’s Cup, serves excellent scones and tea. Duncan took the photos that appear above, and this one, below, of their daughter Eleanor at Cassandra’s Cup. Eleanor lives in England, and Cheryl writes that “like Austen’s Elinor, she is sensible and doesn’t readily reveal her emotions.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post is an excerpt from Janet Todd’s forthcoming book Living with Jane Austen.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

The Challenge of Interpreting Character and Action in Sense and Sensibility, by L. Bao Bui

What Did Lucy Steele? by Diana Birchall

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 13, 2024

The Challenge of Interpreting Character and Action in Sense and Sensibility, by L. Bao Bui

A recent article appeared on The New York Post with the headline, “Gen Z Woman Floored by 35-Year-Old Man’s Text After First Date.” According to the article, the woman “was baffled by the text he sent her the next day.” She proceeded to screenshot the text and share it online, where it amassed over half-a-million views and ignited a spirited debate. One comment posted in response described the man’s text as “too sterile.”

The text in question read, “Hey, had fun last night. Have a good day.” The woman professed confusion over the intention and character of its author. The Post writes that the man’s “millennial texting style made her unable to tell if he wanted to see her again.” In the Gen Z woman’s own words, “I just can’t read him and I really, really want to go on a second date.” Interestingly, the Post article does not indicate if the woman actually communicated to the man what she had already made known to anyone who had access to an electronic device, or who reads the Post.

This Gen Z dater’s experience and her confusion over how her date really felt about her echoes a similar dilemma that vexes Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility. The themes of self-reflection, the struggles to perceive another person’s character and intentions accurately, and the artful schemes devised to deceive and mislead others permeate the Austen canon.

Jane Austen’s House Museum, Chawton

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-sixth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

In Chapter 4 of Sense and Sensibility, Elinor says of Edward Ferrars, her seemingly reluctant suitor, “his person can hardly be called handsome, till the expression of his eyes, which are uncommonly good, and the general sweetness of his countenance, is perceived.” The first courtship to take center stage in the novel unquestionably has its sweetness, and yet it remains inscrutable to both Elinor and readers. Says Elinor, “I am by no means assured of his regard for me. There are moments when the extent of it seems doubtful” (Volume 1, Chapter 4).

Indeed, throughout the opening chapters the words “seem” and “perceive” crop up multiple times in regards to Edward’s conduct towards Elinor, and to how others around him interpret his actions. Three successive paragraphs at the end of Chapter 4 show how Austen artfully plays with the concept of perception and certainty. In the first paragraph, Elinor “knew” that Edward’s mother would object to him marrying a woman of very modest fortune. Mrs. Dashwood and Marianne are “certain” of Edward’s intention to woo and marry Elinor, but Elinor herself is “doubtful” of “the nature of his regard.”

How ironic, then, that Elinor questions the existence of Edward’s attachment to her, for in the very next paragraph, Austen mentions that that same attachment “was enough, when perceived by” Edward’s sister, Mrs. Ferrars, “to make her uncivil” and determined to forcefully nip the courtship in the bud (Volume 1, Chapter 4). She masks her cruelty behind the veneer of respectability and pragmatism. Likewise, her brother Edward must mask his internal turmoil and his divided loyalties. After all, none must know of his secret engagement to Lucy Steele, an arrangement he now deeply regrets and wishes he could undo. Thus, despite their stark differences in personalities and intentions, both siblings project a public image at odds with their true nature (in the case of the sister) or desires (the brother).

Chawton House

Across two paragraphs, Austen reveals how the four Dashwood women contend with two relatives (by marriage) who are unreliable at a time when the Dashwood women are staring genteel poverty in the face. But then, in the next paragraph, Austen shifts to another familial relation of the Dashwoods, and another challenge to the Dashwoods’ (and our) ability to perceive the true nature and intentions of a person:

. . . a letter was delivered . . . which contained a proposal particularly well timed. It was the offer of a small house, on very easy terms, belonging to a relation of her own, a gentleman of consequence and property. . . . The letter was from this gentleman himself, and written in the true spirit of friendly accommodation. . . . He earnestly pressed her . . . to come with her daughters to Barton Park . . . from whence she might judge, herself, whether Barton Cottage . . . could, by any alteration, be made comfortable to her. He seem really anxious to accommodate them; and the whole of his letter was written in so friendly a style as could not fail of giving pleasure.” (Volume 1, Chapter 4)

Edward and his sister appear and act in the flesh and both prove unreliable. In contrast, Sir John has only his epistolary surrogate, in form of his letter, to make his case before the Dashwood women and the audience. Yet the letter, as perceived by the recipient, is judged to be “true” and “earnest,” an appraisal that proves correct. The word “seem” as used in this paragraph does not set up the Dashwood women for later disappointment. When Sir John does appear in Chapter 6, Austen writes that his “countenance was thoroughly good-humoured; and his manners were as friendly as the style of his letter.”

What’s more, his “kindness was not confined to words; for within an hour after he left them, a large basket full of garden stuff and fruit arrived from the park, which was followed before the end of the day by a present of game” (Volume 1, Chapter 6). For the Dashwood women, as for the readers, these immediate and substantial gifts of Sir John and his earnest attention to the comfort of his new tenants stand in sharp contrast to the cold and unkind treatment the Dashwoods had received from their half-brother and his wife. Indeed, later in Chapters 6 and 7, Austen attributes to him “frankness and warmth” (Volume 1, Chapter 6) and “the real satisfaction of a good heart” (Volume 1, Chapter 7).

The kitchen at Jane Austen’s House Museum

Austen’s heroines have the monumental task of assessing their suitors correctly. Much of the delight of reading Austen derives from how we and the protagonists learn to judge character, including their own, with a sharper eye. And yet, Austen shows how formidable that task stands, and how many roadblocks, false assumptions, and misleading impressions lie in the way of a truthful appraisal. The full powers of flesh-and-blood observation, in real time over the course of weeks, may prove insufficient; a single letter reveals and reflects the true character and intentions of its author. Even when the Ferrars siblings stay at Norland, the Dashwood women do not realize how deceptive both Fanny and Edward can be. Sir John’s mode of epistolary communication achieves its purpose; it persuades the Dashwood women to put their lives under his care, and he delivers, with genuine kindness that goes beyond “friendly accommodation.” The mode of communication, whether it takes the form of a short phone text or Sir John’s written letter or Fanny’s spoken words, may not matter at all. What matters, indeed, is the presence of “a good heart,” and some characters have it, and some, not at all.

Quotations are from the Barnes and Noble Classics edition of Sense and Sensibility (New York, 2004).

L. Bao Bui he received his doctorate in history from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, in 2016. His dissertation examined personal privacy and letter-writing during the American Civil War. He is currently working on a book manuscript titled, Mail Intimacy: Gender Roles and Epistolary Privacy during the Civil War. He holds degrees in political science from the University of California, Berkeley, and in English literature from Pomona College. He has taught courses in food politics, military history, foreign relations history, women and gender history, human rights, Jane Austen, and film and media studies, in addition to survey courses in American and world history. An avid tango dancer, he has visited communities of Argentine tango dancers throughout the world.

Bao at Winchester Cathedral

All the photos are from Bao’s visit to Winchester and to Alton and Chawton in August, which was, he says, “the fulfillment of a long-standing obligation to Austen to visit her resting place.” Bao says that when he teaches Jane Austen at UIC, “In the first week of class, many of my students write that they read Austen because her novels provide them with a novel way to view the modern world that they live in.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “On the Road with Elinor and Marianne,” is by Cheryl Bell.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

What Did Lucy Steele? by Diana Birchall

The Real Romantic? Marianne Dashwood and Fanny Price, by Theresa Kenney

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 10, 2024

What Did Lucy Steele? by Diana Birchall

Who is Lucy Steele, what is she? Does she belong to the cohort of Jane Austen’s villains? Or does she have some excuse for her often distasteful behavior, so brilliantly skewered by Jane Austen? Austen may have meant to slyly suggest evildoing for this character, by her name alone: “Steele” for her steely will, and her grasping, even thieving proclivities; and Lucy for—Lucifer? Yet on close examination she does not quite measure up, or down, to a Jane Austen villain on the grand scale. Major villains, particularly the bully type, such as General Tilney, Lady Catherine, or Mrs. Ferrars, often wield considerable power of a domestic variety, as being at the head of families that have been made dysfunctional largely through their tyranny.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-fifth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Perhaps some villains are born, some achieve villainy, and some have villainy thrust upon them. Lucy Steele, a poor and powerless young woman when we first meet her in Sense and Sensibility, born into poor circumstances, is like others in such circumstances, extremely limited in her choices. Being innately clever, she very early in life comes to the logical conclusion that she must marry for money, and she proceeds to claw her way to success. But all poor young women do not become villains, and the streak of jealous spite and cruelty that Lucy possesses is not entirely explained by her condition.

A heroine like Fanny Price of Mansfield Park, demi-heroine Jane Fairfax of Emma, or Charlotte Lucas of Pride and Prejudice, may be as poor and portionless as Lucy Steele, and still not have bad principles or be breathtakingly self-serving. Jane Fairfax does wrong in consenting to a secret engagement, but Emma reflects, “If a woman can ever be excused for thinking only of herself, it is in a situation like Jane Fairfax’s. Of such, one may almost say, that ‘the world is not their’s, nor the world’s law’” (Volume 3, Chapter 10). Elizabeth, when considering her friend Charlotte’s baldly unromantic marriage, is less forgiving, saying that the woman who marries Mr. Collins can have no real feeling; yet Charlotte has no spite, harms no one else, and is only acting practically, in hope to better her own situation. Ironically, Fanny Price, the poorest of these young women, is the only one who, so far from being determined to marry for money, cannot even be forced into it. Perhaps Lucy’s closest soul sister is Isabella Thorpe of Northanger Abbey, but she is only silly, with none of Lucy’s sharpness.

Among Austen’s penurious young women, Lucy most lacks any kind of fallback protection. The Campbells will never allow Jane Fairfax to starve; Fanny is under the protection of Sir Thomas; Charlotte has a large family, though they would likely use her as a drudge if she doesn’t marry. Lucy is singularly calculating, with her double dealing schemes and complete indifference to the feelings of others. She succeeds in winning her particular pot of gold (if Robert Ferrars with his fancy toothpick cases can be seen as such), though Jane Austen makes it clear that Lucy’s marriage will not achieve the domestic contentment of the others. The selfish behavior Lucy has habitually employed all her life is not improved, but reinforced by the achievement of her object. Nothing is more likely than that someday, Lucy Steele will be the next Mrs. Ferrars, senior, with the de facto headship of a family and its money, and it will then be her turn to wield the malevolent headship of a dysfunctional family with her experienced puppeteer’s hands.

Lucy’s origins, her methods, her ambition, and her success, are all of a piece. Jane Austen sums up her doctrine by saying, “The whole of Lucy’s behaviour in the affair, and the prosperity which crowned it, therefore, may be held forth as a most encouraging instance of what an earnest, an unceasing attention to self-interest . . . will do in securing every advantage of fortune, with no other sacrifice than that of time and conscience” (Volume 3, Chapter 14).

Even as only an embryo villain, Lucy is already one of Austen’s most comically monstrous characters. Lucy is more nuanced than Mrs. Ferrars, the novel’s coldest, one-note monster, though some of her most fawning relations insist that she is the tenderest of mothers. We may detect in Lucy, though never in Mrs. Ferrars, some faint traces of a vestigial and vanishing good nature, perhaps because she has had less time to grow hardened. Her displays of kindness are largely illusory, like her obsequious behavior to her betters (which they never see through—I love Austen’s observation, “Fortunately for those who pay their court through such foibles, a fond mother, though, in pursuit of praise for her children, the most rapacious of human beings, is likewise the most credulous; her demands are exorbitant; but she will swallow anything” [Volume 1, Chapter 21]).

Yet Lucy does have the surprising merit of not being unkind to her inferiors. She tolerates her unbearably silly sister Nancy (though that may only be because she finds her a useful tool). And Mrs. Dashwood’s servant describes her as “a very good natured young lady” (Volume 3, Chapter 11), even using the expressive word “affable.” But Lucy’s affability is part and parcel of her leading skill, her outrageous flattery. Her piled-on solicitousness to the little Middleton children illustrates her in full flight of flattery, unsubtle in her false and saccharine efforts. The reader sees what she is, and so does Elinor, who reflects that her “conduct towards others, made every shew of attention and deference towards herself perfectly valueless” (Volume 1, Chapter 22).

With Robert as her creature, and her steeliness in maintaining an armed stance against imagined threats from Edward and Elinor for the family fortune, by the time Lucy is a senior Ferrars matriarch, any heart she ever had will have hardened completely. Jane Austen shows us characters who do harden (as witness Mr. Elton of Emma, who was not “quite so hardened as his wife, though growing very like her” [Volume 3, Chapter 2]) and knew that a person may grow hardened from bad association, but Lucy is not apparently affected by the influence of anyone else, for good or evil. Elinor shudders to think what Edward’s life would have been, married to Lucy. His morality was such that Lucy would not have corrupted him, in fact he might have made her behavior a shade more respectable. Once married, Lucy might carefully adhere to the rules of conventional middle class moral behavior. But in the end it is Lucy’s own calculating, cold prudence, in changing Edward for Robert, that saves Edward from being her very unhappy husband.

All bona fide Austen heroines have a heart, and desire a marriage of the heart. By that definition alone Lucy is no heroine. Yet rich girls as well as poor in Jane Austen’s England were equally trained to dispense with love in favor of money: in Mansfield Park Lady Bertram’s only advice to Fanny is that it is “every young woman’s duty to accept such a very unexceptionable offer” (Volume 3, Chapter 2). Lucy does not need to be told this piece of wisdom.

If there’s no love in Lucy at all, neither is there much pride, a signal quality of many a villain. Her absence of pride is shown by the fact that there is nothing she will not stoop to, in order to further her ambitions. Where does Lucy’s ambition come from? She herself comes from Exeter, the largest market town in gentle Devonshire. This is a benign location, not a place of unpleasant associations. We know Lucy is “two or three and twenty,” and that she and her nearly thirty-year-old sister divide their time between their father in Exeter, and their uncle Mr. Pratt, who lives near Plymouth. They have no mother, and their father is mentioned only once: Mrs. Jennings speculates on “what little matter Mr. Steele and Mr. Pratt can give” Lucy (Volume 3, Chapter 2). Mrs. Jennings is another connection of Lucy’s, whom she accidentally runs into in Exeter, or possibly pursues there. Through her, Lucy schemes to meet Lady Middleton and the Dashwood sisters, because their connection to Edward’s family might help ingratiate her with Mrs. Ferrars. Lucy is nothing if not far-seeing in her machinations.

Between Plymouth and Exeter Lucy and Nancy seem to have had a lively social life. The two towns are fifty miles apart, so if Lucy spent much time with her uncle the teacher, it must have been worth her while. Perhaps she helped to keep his house, or to care for the young boys who were his pupils; or she might have stayed there in hopes to attract a better class of gentleman husband among her uncle’s pupils than she could find among her old acquaintance at Dawlish and Exeter.

Despite being without fortune, Lucy manages to make a good appearance for herself. When the Miss Dashwoods first meet the Miss Steeles, we are told, “The young ladies arrived, their appearance was by no means ungenteel or unfashionable. Their dress was very smart,” and also, they have “brought the whole coach full of playthings for the [Middleton] children” (Volume 1, Chapter 21). Lucy’s foreplanning is admirable, though how she and Nancy managed to afford all this is a matter of some curiosity, except that we know that one of Lucy’s skills is being able to make a little go a long way. When Elinor pictured Lucy’s marrying Edward, “She saw them in an instant in their parsonage-house; saw in Lucy, the active, contriving manager, uniting at once a desire of smart appearance with the utmost frugality, and ashamed to be suspected of half her economical practices;—pursuing her own interest in every thought, courting the favour of Colonel Brandon, of Mrs. Jennings, and of every wealthy friend” (Volume 3, Chapter 12).

However highly developed the sisters’ talents at wheedling material goods from benefactors, despite all their striving, one thing they never attain is an education. It is a fascinating and hilarious study to examine Nancy’s ungrammatical speech and Lucy’s letters, of which Edward says, “In a sister it is bad enough, but in a wife! How I have blushed over the pages of her writing!” (Volume 3, Chapter 13). Jane Austen illustrates the sisters’ written and spoken style with brilliant observation and wit. Their use “was” for “were” (“I felt almost as if you was an old acquaintance”) and their ungrammatical mistakes like “the person it was drew for,” “Edward have got some business,” and vulgar expressions such as “dreadful low spirited” and “monstrous glad” are priceless.

We may ask how a girl from a family with at least some connections, and contact with educated people (her uncle was considered a suitable enough scholar to teach an upper-class young gentleman like Edward Ferrars) grew up to be “ignorant and illiterate” (Volume 1, Chapter 22), in Elinor’s words, yet spectacularly cunning in achieving her rise. Mr. Pratt may have influenced Edward in his choice of a vocation, but we do not know if Mr. Pratt was a clergyman himself, if he followed the model of Austen’s own father, Mr. Austen, a clergyman who kept scholars. As poor girls, Nancy and Lucy were not given much education (and that Lucy’s is markedly better than Nancy’s may be because she is much cleverer at picking things up, or Mr. Pratt’s circumstances and pupils may have improved from the time when Nancy, now nearly thirty, began to be a young lady). But clearly Mr. Pratt did not stand in the way of his niece’s schemes for attracting Edward. The romance was right under his nose and he may even have promoted it. However, there’s no evidence of his attempting to give his niece any moral sense, nor did her four years’ engagement to Edward improve her.

Lucy knew she had to compete to succeed, and the deviously competitive can scarcely ever have found a more striking embodiment. The subjects of wealth and competence, and self-aggrandizement, are everywhere in this novel, expressed by a girl who said that “how little soever [Edward Ferrars] had, she should be very glad to have it all” (Volume 3, Chapter 2). Yet even though Lucy ultimately becomes the financial victor of Sense and Sensibility, her happiness is not likely, as Austen indicates in this marvelously ironic and witty description: “setting aside the jealousies and ill-will continually subsisting between Fanny and Lucy, in which their husbands of course took a part, as well as the frequent domestic disagreements between Robert and Lucy themselves, nothing could exceed the harmony in which they all lived together” (Volume 3, Chapter 14).

Lucy’s innate spitefulness is an extra fillip on top of her necessitous scheming. Jane Austen tells us how after her marriage, “They passed some months in great happiness at Dawlish; for she had many relations and old acquaintance to cut,” a clear depiction of gratuitous behavior. Spite she has, in plenty: her “flourish of malice” in letting the Dashwoods believe she had married Edward, by her elaborate charade of showing herself and her new husband to their servant, proves this, and Edward himself ended with believing her “capable of the utmost meanness of wanton ill-nature” (Volume 3, Chapter 13).

We cannot know what gave Lucy her spice of spite. Few characters are as purely spiteful as she; a quality that in others generally originates in jealousy, as exampled by Caroline Bingley in Pride and Prejudice (“She a beauty! I should have as soon called her mother a wit”). Yet, Caroline mends her manners after Darcy marries Elizabeth, while Lucy’s spite toward Elinor, even after she has achieved her own goal, is solely and maliciously intended to cause pain.

And here our guessing about Lucy must end, for we know little about her earliest influences. Her uncle may have had a benign influence on Edward, but did he teach his niece spite, or act as advisor—was he her evil genius? There is no such indication. At this point we may observe the deliberate limiting of Austen’s artistic canvas. About her major characters we usually know a good deal—for she has conceived her fictional world in such perfection, so rich in details—but like an artist who does not paint all the details to the borders of his paintings, she leaves minor edges fading into obscurity. She could no doubt tell us every detail of Lucy’s background and upbringing, had she been so minded, and she does give a few hints that readers of her own era might have read more easily than we. But she chooses not to tell more.

It is Lucy’s selfishness that Austen most amply delineates, with comical, human relish. The manipulations with which Lucy minutely carries out her ends are depicted with penetrating, devastating wit. We see precisely what Lucy is up to; it is through her actions that we know her. We also know what it was that Lucy stole: A family fortune and any chance of wider family harmony.

Quotations are from the Oxford University Press editions of The Novels of Jane Austen, edited by R. W. Chapman.

A note from Diana: This essay was first written as notes for the play of the same title that I wrote with Syrie James which we performed at the JASNA AGM in 2022 in Victoria, BC. In this photo we’re performing the hilarious fan fight scene in the Victoria AGM performance of “What Did Lucy Steele?” She is Lucy and I’m Mrs. Ferrars.

Diana Birchall worked for many years as a story analyst for Warner Bros Studios, reading novels to see if they would make movies. Reading popular fiction went side by side with a lifetime of Jane Austen scholarship and writing Austenesque fiction both as homage and as close study of Jane Austen’s style. She is the author of Mrs. Darcy’s Dilemma, The Bride of Northanger, In Defense of Mrs. Elton and Mrs. Elton in America, as well as hundreds of short stories. Her Austenesque comedy plays have been performed in many cities, with “You Are Passionate, Jane,” a dialogue between Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte in Heaven, being presented at Chawton House Library in England. It was also filmed and presented with discussion by the Jane Austen Summer Program, and is now available to watch on YouTube.

Diana has also written a scholarly biography of her grandmother, the first Asian American novelist, Onoto Watanna, and has lectured widely about her books at universities including Yale, Columbia, and NYU. She grew up in New York City, and now lives in Santa Monica, California. Her husband Peter was a poet, and her son Paul is the librarian on Catalina Island. The first flower photo (lupines and leopard lilies) was taken in the Sierras. Diana and Peter did most of their hiking near Mammoth and in Sequoia National Park. The other flower photos are wild nasturtium and iceplant, Southern California wildflowers that grow near Diana’s home.

A chapter from Diana’s story of The Darcys in Venice was published at Austen Variations recently and I enjoyed it so much that I want to share the link. Here’s Mr. Collins, addressing Lord Byron:

“Do you know, this garden almost reminds me of Rosings, though of course Rosings does not have a canal, and is all the better for that. Nothing, after all, can equal Rosings. The water here does not look quite clean. It is indeed an image that speaks eloquently of the moral failings of this city and its people. A very sluggish stream, indeed.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post is by L. Bao Bui, who explores the struggle to perceive character and intentions accurately in S&S.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

A book signing and other celebrations (written by me)

The Real Romantic? Marianne Dashwood and Fanny Price, by Theresa Kenney

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 8, 2024

A book signing and other celebrations

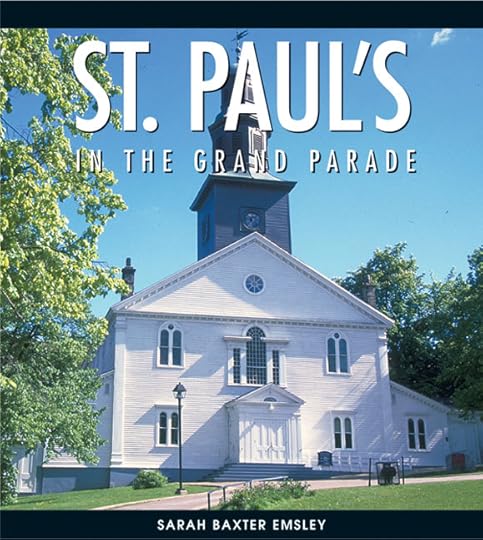

Next Sunday, September 15th, I’ll be signing copies of my book St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, which I wrote for the 250th anniversary of St. Paul’s Church, the oldest building in Halifax, Nova Scotia and the oldest existing Anglican place of worship in Canada.

Jane Austen’s niece Cassy Austen was baptized at St. Paul’s on October 6, 1809, when her father, Captain Charles Austen, was serving on the North American Station of the British Royal Navy. You can find out more about Jane Austen’s connection with Nova Scotia in the “Austens in Halifax” walking tour my friend Sheila Johnson Kindred and I created.

On September 15th at 11:15, after the morning service, the official opening of the church’s 275th year, Alison Kitt-Grainger will be signing copies of St. Paul’s Church at 275 and I’ll be signing St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade. (Where did those 25 years go, I wonder??)

All are welcome! The location is 1749 Argyle St., across from City Hall in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Visit the St. Paul’s website for more details about the event. The guest of honour at the service will be the Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada, Archbishop Linda Nicholls.

Regular readers of my blog know that I like to celebrate significant anniversaries and special occasions. For example, for the 100th anniversary of Edith Wharton’s 1913 novel The Custom of the Country, which I edited for the Broadview Literary Texts series, I wrote a series of posts, including one on “What Edith Wharton Tells Us About the Way We Live Now.”

That same year, 2013, I started hosting blog series celebrations for novels by Jane Austen, for the 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice, but my interest in anniversaries goes back further, to the 250th anniversary of St. Paul’s Church in 1999 and, even before that, the 80th anniversary of the Hotel Macdonald in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1995 (the subject of my first book).

I do realize that my current “Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” blog series doesn’t match up with a milestone anniversary year (unless we redefine “milestone” so that 213 counts?)—I missed the chance to celebrate the 200th anniversary back in 2011 and thought I’d make up for that now. With the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth coming up in 2025, this year seemed like a good time to celebrate her first published novel. It’s been a great pleasure to read and share all the guest posts to date, and I’m excited about the remaining posts in the series. This week, we’ll hear from Diana Birchall and L. Bao Bui; next week, we’ll hear from Cheryl Bell and Janet Todd.

The next blog series celebration will begin on October 30th—the 213th anniversary of the date Sense and Sensibility was published—with a guest post from Kate Scarth, Chair of L.M. Montgomery Studies at the University of Prince Edward Island. Her essay on “Anne Shirley and Marianne Dashwood, #KindredSpirits” will link the summer S&S series with the celebration of L.M. Montgomery’s 150th birthday that will run through the month of November.

That’s a lot of celebrating! I do love bringing people together to celebrate these amazing writers, and while putting these series together takes a lot of time, it feels like time well spent. It always means a great deal to me to hear from readers who are enjoying the guest posts.

In fact, I enjoy organizing blog series celebrations so much that when the Jane Austen Society of North America asked me to co-host a celebration of Austen’s 250th next year on the JASNA website, I said yes. We have some fabulous tributes to Jane Austen lined up already and I’m excited to share them with you. More on that celebration soon….

Many thanks to all who are participating in these celebrations by writing, reading, and joining in the conversations! I’m glad you’re here. And I hope to see some of you in person next Sunday at St. Paul’s.

Thank you to Brenda Barry for the beautiful photos of astilbe and phlox that appear above, taken recently in the Historic Gardens in Annapolis Royal, NS.

For today, I am taking a break from reading, writing, editing, and email to go for a hike and eat cake and ice cream with my family. It’s my birthday—and International Literacy Day! More reasons to celebrate. I’ll leave you with a couple of photos of the cakes my daughter made for my birthday last year, along with a photo of this year’s birthday flowers.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

The Real Romantic? Marianne Dashwood and Fanny Price, by Theresa Kenney

An Ill-disposed Narrator? Backhanded Insults in Sense and Sensibility, by Kathy Cawsey

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 6, 2024

The Real Romantic? Marianne Dashwood and Fanny Price, by Theresa Kenney

Marianne Dashwood has risen in the estimation of audiences and critics to the point where some believe if Austen changes her character, Marianne’s “reduction” is a punishment for what we now consider admirably romantic and passionate behavior. The novel’s own Colonel Brandon models such an interpretation, telling Elinor in Chapter 11, when inquiring about Marianne’s belief that a second attachment in life is impossible,

“ . . . but a change, a total change of sentiments—No, no, do not desire it,—for when the romantic refinements of a young mind are obliged to give way, how frequently are they succeeded by such opinions as are but too common, and too dangerous! I speak from experience. I once knew a lady who in temper and mind greatly resembled your sister, who thought and judged like her, but who from an enforced change—from a series of unfortunate circumstances” —Here he stopt suddenly. . . .

But of course, if he is to marry Marianne by the end of the novel, Marianne’s sentiments on exactly this point must change. Until Alan Rickman played the lovelorn Brandon, marriage to that character seemed a punishment for the ebullient Marianne. Just look at the aggravating advice the BBC 1981 Colonel Brandon gives Marianne to read “the majestic Milton, and the demi-god, Shakespeare,” which Marianne later dutifully parrots to her mother. Marianne loses all her energy and self-confidence and her prize is the dull middle-aged man with lambchop whiskers.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-fourth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Is change necessary in the heroine of a novel? Some have argued that Elinor cannot be the real heroine of the novel because she doesn’t change. Her stoic resignation and self control seem to be something Austen reinforces and rewards, without convincing us that they save her or her family from any pain or that they produce satisfying poetic justice, since they only procure for her the Delaford parsonage and the unexciting Edward Ferrars. Harkening to the norms for heroes and heroines YouTube creative writers purvey, my students tell me characters cannot be protagonists if they do not mature between the beginning and the end. Holding either opinion ill prepares the reader for understanding Sense and Sensibility, or indeed any of Austen’s “quiet” heroines. Austen was not bound by the rules that content creators share so freely with would-be novelists and manga cartoonists of today. Neither were Homer or Shakespeare, for that matter.

However, what is Marianne’s status in the novel that we believe once bore her name as well as her sister’s? Is she the hidden heroine or is she merely the inferior second sister who must become like the eldest to arrive happily at the conclusion of her story?

I have been thinking a great deal about Marianne’s similarity, not to Elinor, but to the heroine of another novel Austen wrote over a decade later, Mansfield Park, and that character is another teen who loves early romantic poetry, Fanny Price. Given the astonishing similarities between them, it is surprising how warm the affection for Marianne is among readers and how heated the disapproval is of Fanny. Comparing and contrasting the Steventon novel romantic, Marianne, with the Chawton novel romantic, Fanny, shows Austen maintaining her interest in certain problems from the 1790s until 1814, and helps us understand the widely disparate reactions to the two young women.

First, readers should see that Austen understands the romantic enthusiasms of both Marianne and Fanny as typical behavior for a teenaged reader. “‘Dear, dear Norland!’ said Marianne as she wandered alone on the last evening of being there. . . . And you, ye well-known trees!—but you will continue the same.—No leaf will decay because we are removed . . . you will continue the same: unconscious of the pleasure or the regret you occasion, and insensible of any change in those who walk under your shade’” (Volume 1, Chapter 5).

Fanny similarly rhapsodizes before the outing to Mr. Rushworth’s estate at Sotherton (her own word for this kind of speech in a later conversation with Mary Crawford): “Cut down an avenue! What a pity! Does not it make you think of Cowper? ‘Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited.’” (Volume 1, Chapter 6; Book I of The Task, “The Sofa,” lines 338-39).

Lamenting over trees is clearly the job of the sensitive soul. But how much of this is internalized aesthetics and norms, how much is performance? Isabella Thorpe’s performance of sentimentality in Northanger Abbey has perhaps already formed a lesson in sincerity for the Austen reader, even if one has not read the juvenilia, which are full of such parodies of performed emotional sensitivity. Marianne’s love for what teenaged girls love is partly performative; I think this is a fault Austen believes teenagers can fall into if they are enthusiastically bookish, as Marianne is, or if they must be so to fit into a social group, as Isabella Thorpe seems to be. Her bookishness itself is also performative, which Marianne’s is not. It has been suggested by some scholars that Isabella has not even read the books on her friend Miss Andrews’s list in Chapter 6; she and Catherine Morland never make it through Udolpho!

Austen does not seem to dislike Marianne’s love of the melancholy in nature, but she does point out that Marianne judges others harshly if they lack it. Edward will teasingly point out, “It is not every one who has your passion for dead leaves” (Volume 1, Chapter 16) and in doing so, he may mark himself as unromantic, but the fact that Austen thought up his line shows she dislikes the performative nature of this “passion.”

At least we can say if it is an element in Marianne’s character that all the older characters but her mother have tempered since that age, if they ever had it, Austen imagines it a passing fad indicative of the character’s youth. Marianne’s reading of her sources is undigested as of yet. And yet she has already known real sorrow. In their focus on Marianne’s heartbreak over Willoughby, readers forget she has just lost her father and the Dashwood family is in mourning for him through most of the timeframe the novel covers.

Fanny Price’s passion for romantic poetry and the sentimental attitudes its heroines exhibit is perhaps an element Austen considers appropriate in depicting her as a rather naïve teenager. Vladimir Nabokov wrote discussing Fanny’s frequent quotations of or allusions to poetry, especially in conversations with Edmund. He says,

. . . we must bear in mind that in Fanny’s time the reading and knowledge of poetry was much more natural . . . and widespread than today. Our cultural, or so-called cultural, outlets are perhaps more various and numerous than in the first decades of the last century, but when I think of the vulgarities of the radio, video, or of the incredible, trite woman’s magazines of today, I wonder if there is not a lot to be said for Fanny’s immersion in poetry. (Lectures on Literature, Mariner Books, 1982)

However, thinking of poetry generally leads Fanny, unlike Marianne, to contemplation of deep issues. She does not stall in rapturous imitation. Though her exclamations may have a tinge of the imitative, her references are quite consciously quotations, and because she is merely sharing her enthusiasm with Edmund, who has read the same works without apparently wishing to be seen as a romantic hero himself, it seems less as if she is acting out a learned part.