Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 11

June 21, 2024

What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes, by Finola Austin

Over the years, whenever I’ve read or re-read Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (published 1811), or watched various stage and movie adaptations, I’ve wondered what my own verdict should be—sense or sensibility? Or, in other words, Elinor or Marianne?

As an older sister myself, I have a natural bias towards Elinor, and Austen certainly wants us to see her as the true heroine of her novel. After all, our first introduction to Marianne, written with typical Austenian litotes, is, “Marianne’s abilities were, in many respects, quite equal to Elinor’s” (Volume 1, Chapter 1), which leverages understatement to draw our attention to the younger sister’s relative failings. However, there is much I found, and still find, appealing about Marianne’s romantic, artistic, and, yes, at times overly dramatic disposition.

(From Sarah: This is the second guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began yesterday and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Elinor and Marianne was Austen’s original title for the novel. So central is this contrasting pair to the book and its themes that many fans forget about the existence of the other Dashwood sister—Margaret. But recently I found myself flicking through the book with a new eye, doing a “Margaret read” to understand if there were any details about the third sister I might have overlooked.

It wasn’t a promising start. There are over 120K words in Sense and Sensibility, yet Margaret’s name is mentioned a mere 36 times.

Austen gives us this pretty damning introduction to her character, which comes just after Marianne’s: “Margaret, the other sister, was a good-humored, well-disposed girl; but as she had already imbibed a good deal of Marianne’s romance, without having much of her sense, she did not, at thirteen, bid fair to equal her sisters at a more advanced period of life” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). In the real world, someone saying you probably won’t live up to your older siblings can probably be shrugged off. But when an omniscient Austenian narrator says this, you’re in for trouble.

Poor Margaret! She’s proven wrong pretty much whenever she expresses an opinion throughout the novel. She dismisses Colonel Brandon for being “on the wrong side of five and thirty” (Volume 1, Chapter 7). She’s convinced Marianne and Willoughby will marry. And she sets off optimistically with Marianne on their ill-fated walk, which leads to Marianne’s fall in the rain.

Margaret may only be thirteen, but that doesn’t mean she’s spared harsh critiques for her silliness. Austen tells us Margaret refers to Willoughby as “Marianne’s preserver . . . with more elegance than precision” (Volume 1, Chapter 10). And—here comes that litotes again!—when Margaret puts her foot in her mouth speaking about Elinor and Edward, we get this particularly withering line: “Margaret’s sagacity was not always displayed in a way so satisfactory to her sister” (Volume 1, Chapter 12).

But, slight as the character work on Margaret is, Austen doesn’t veer into caricature when writing about her. The good humor and disposition Austen mentions upfront comes through at certain moments, like in this interaction, which underlines Margaret’s lack of material worldliness and contrasts her with Marianne to Margaret’s advantage:

“I wish,” said Margaret, striking out a novel thought, “that somebody would give us all a large fortune apiece!”

“Oh that they would!” cried Marianne, her eyes sparkling with animation, and her cheeks glowing with the delight of such imaginary happiness.

“We are all unanimous in that wish, I suppose,” said Elinor, “in spite of the insufficiency of wealth.”

“Oh dear!” cried Margaret, “how happy I should be! I wonder what I should do with it!”

Marianne looked as if she had no doubt on that point.

(Volume 1, Chapter 17)

Near the end of the novel too Margaret demonstrates loyalty and sensitivity toward Elinor, after her previous carelessness about her feelings: “Margaret, understanding some part, but not the whole of the case, thought it incumbent on her to be dignified, and therefore took a seat as far from [Edward] as she could, and maintained a strict silence” (Volume 3, Chapter 12).

The references to Margaret’s limitations are still there (she still doesn’t fully understand what is going on), but this change from her earlier indiscretion when talking about Elinor’s emotions gives us a glimmer of hope that she may yet learn from her older sisters’ (and particularly Elinor’s) example.

The last reference we have to Margaret in the novel teases us further about who she might be when she’s grown: “fortunately for Sir John and Mrs. Jennings, when Marianne was taken from them, Margaret had reached an age highly suitable for dancing, and not very ineligible for being supposed to have a lover” (Volume 3, Chapter 14). For now, Margaret’s prospects are merely a diversion for her neighbors. But in a few short years, could she too be in for her own romantic adventure?

Overall, on this read, I was struck most by the believability of Margaret. She might not be crucial to the premise of Sense and Sensibility, like Elinor or Marianne, and at times she is used as a device to move the story forward (as in the hair cutting scene with Willoughby). Yet, of all three sisters, Margaret seems most like a girl we’ve probably all met—flawed and socially inexperienced, but, above all, relatable.

Quotations are from the Project Gutenberg edition of Sense and Sensibility. The wild rose photos were taken earlier this week in Greenwich, Prince Edward Island (by Sarah).

Finola Austin is an England-born, Northern-Ireland-raised, Brooklyn-based author of historical fiction. Her debut novel, Bronte’s Mistress , was published by Atria Books in 2020. She is the writer behind the Secret Victorianist , a blog on nineteenth-century literature and culture. By day, she works in digital advertising. Find her online at www.finolaaustin.com .

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Sense and Sensibility in my most need,” is by Heidi L.M. Jacobs.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Sisters and Sisterhood, by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney

Your invitation to A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility

June 20, 2024

Sisters and Sisterhood, by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney

The mid-1990s was a good time to discover the works of Jane Austen. Having grown up in different towns in the north of England, we each have strong memories of settling down on the sofa on Sunday evenings to watch the famous BBC TV series of Pride and Prejudice, and of trips to our local cinemas where we experienced Ang Lee’s visually sumptuous Sense and Sensibility. And who can forget Clueless, written and directed by Amy Heckerling, which loosely transposed the plot of Emma to that of a Beverly Hills high school—familiar to us in terms of the nineties era, if not the social milieu? Enjoyable as these adaptations were, their most important effect was that they encouraged us to turn to Austen’s original words.

(From Sarah: This is the first guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

We each recall chatting about our reading with our younger sisters—conversations that seem particularly fitting since Austen was so close to her own sister, Cassandra. Austen enjoyed the benefits of sororal closeness in a more figurative sense, too, through her friendships with Martha Lloyd, for instance, and the amateur playwright and governess, Anne Sharp. We explored the latter’s connection with the celebrated author in our cowritten group biography about female literary friendship, A Secret Sisterhood.

Given Austen’s close bonds with other women, it’s unsurprising that the subjects of sisters and sisterliness frequently recur as themes in her novels. On rereading Sense and Sensibility recently, we were struck anew by the extent to which its plot turns on the inner workings of the relationships of two sets of sisters: the likable Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, and their antitheses Anne and Lucy Steele.

These pairs of siblings are on such opposing sides of the reader’s sympathies that it is easy to miss the similarities in the way each of these relationships functions. The two older Dashwood sisters are famously presented as opposites in temperament. We are told in the first chapter that Elinor “possessed a strength of understanding, and coolness of judgement,” whereas the younger Marianne was “eager in every thing; her sorrows, her joys, could have no moderation” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). When, later, we meet the Miss Steeles we learn that the older Anne was endowed with “a very plain and not a sensible face,” whereas Lucy has “considerable beauty” and a manner of being that is more consciously refined than that of her sister (Volume 1, Chapter 21). Despite their outward differences, however, Lucy and Anne, and also Marianne and Elinor, can be regarded as sisters alike at heart.

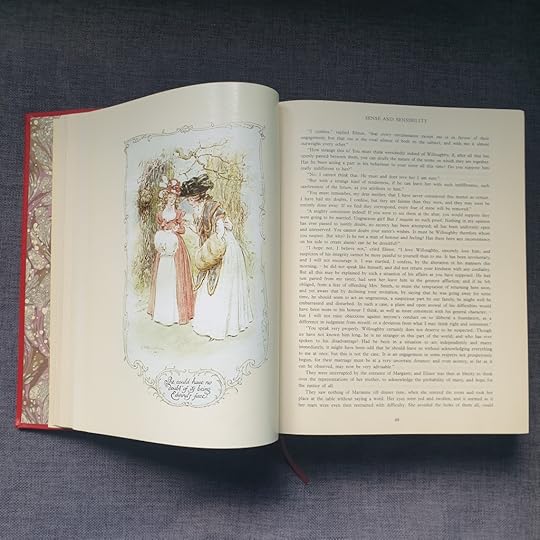

The Complete Works of Jane Austen, The Illustrated Library, published by Midpoint Press, 2006. A gift to Emily from her sister, Erica.

In the Miss Dashwoods’ case, the two young women bridge the gap between them through their shared sense of honour, loyalty and love. As for Anne and Lucy, though the older sister is decidedly dull, whereas Lucy is quick-witted and regarded by many as amusing, their chief aims in life are much the same: the pursuit of “beaux” and their accompanying fortunes, and the gaining of favour with any person of influence. Although it is tempting to see the Dashwood sisters in a positive light while regarding the Miss Steeles as vulgar and mercenary, it is worth remembering that, given the limited opportunities for women of the era, there may have been some wisdom to the latter pair’s behaviour. Thought of that way, it’s possible to regard these sisters, too, with some compassion and understanding.

One admitted contrast between the Dashwoods and the Steeles is the extent to which each young woman within a pair attempts to change the other. Of the two Dashwoods, Elinor represents sense, Marianne sensibility. Through much of the novel each is so assured of the righteousness of her own stance that she is constantly trying to reform her sister. Lucy sometimes seems embarrassed by Anne’s comparatively coarse way of speaking and the carelessness of her manner, but she rarely does more than chiding her behaviour in the moment. Neither sister seems able to look at herself or her sibling with enough reflection to evaluate the aspects of their personalities that might be in need of reform. Indeed, this lack of insight on Anne’s part leads her to reveal the truth about her younger sister’s secret engagement to Edward Ferrars to his furious mother—an unintentionally harmful act that nearly results in the social ruin of both the Miss Steeles.

By the end of Sense and Sensibility, Elinor and Marianne have grown as characters. They have reached a better understanding of each other and have become less judgemental. By staying true to their principles they have been rewarded with matrimony—a state of romantic bliss which, Austen assures us, will do nothing to shake their own sisterly bond since the two still live “without disagreement,” very happily “within sight of each other” (Volume 3, Chapter 14).

Through clever manoeuvring, Lucy has also been rewarded with marriage, but her union with the vain and irresponsible Robert Ferrars cannot ever be the same kind of attachment as the true and genuine affection Elinor shares with his brother, or which Marianne is taken aback to find she can embrace with Colonel Brandon. As for Anne, the suggestion is surely that, at almost thirty when we first meet her, she is destined to remain a spinster. To be unmarried was rarely presented as enviable in literature of the period, interestingly not even by an author like Austen—someone who turned down a marriage proposal, thereby choosing to remain single, a status that allowed her to prioritise her writing. It isn’t clear whether, having so distressed the formidable Mrs. Ferrars, Anne can ever fully be taken into the fold of her sister’s new clan. Lucy has previously seemed loyal to Anne, but both of the Miss Steeles are essentially self-centred, so the extent to which she will try to help her older sibling is also similarly uncertain.

Sense and Sensibility is, of course, just as much a novel about sisters and sisterhood as it is about love and marriage—more so, even. In this, her first published novel, Austen celebrates the steadfast nature of Marianne and Elinor’s bond, which withstands outside crises and misunderstandings from within to become even stronger by the book’s end. Austen’s own sisterly relations with the women closest to her experienced their own occasional ructions, but her surviving letters illustrate that she attached great importance to these attachments. They sustained her through her life’s ups and downs, including the long period during which she laboured at her craft without any commercial success. Sense and Sensibility, for instance, begun in the mid-1790s, was not published until 1811.

Awareness of the various “sisters” who supported the unknown Austen has been of great importance to us through the years. At the time that we began researching A Secret Sisterhood, we had long been struggling as unpublished authors, and so—in this respect at least—we felt we had something in common with our literary heroine. We took heart in the knowledge that, after many years of unrecognised toil, Austen achieved publication, just as we hoped we would too in the end. And we consoled ourselves that, like Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, and Austen and her closest female influences, we would have our sisterly bond to keep us going until then.

Quotations are from the Norton Critical edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited and with an introduction by Claudia L. Johnson (2002). All photos contributed by Emily and Emma.

Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney are the co-authors of A Secret Sisterhood: The Literary Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot and Virginia Woolf, for which Margaret Atwood supplied the foreword. You can explore some of their earlier writing about female literary friendship at http://www.somethingrhymed.com. Emma is a lecturer in creative writing at the Open University and a director of the Ruppin Agency Writers’ Studio, as well as the author of the novel Owl Song at Dawn. Emily is a lecturer on the writing programme at NYU London and the author of Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice. Their websites are emilymidorikawa.com and emmaclairesweeney.com. You can also find Emma on X @emmacsweeney and on Facebook. You can find Emily on Instagram (and Threads) @midorikawaemily and on X as @emilymidorikawa.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes,” is by Finola Austin.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Your invitation to A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility

“More than I can tell” (Quotations from Alice Munro)

June 14, 2024

Your invitation to A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility

Please join me for “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” a new series of guest posts, which will launch next Thursday with an essay on “Sisters and Sisterhood,” by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney.

With the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth coming up in 2025, this is a great time to celebrate her first published novel. We’ll begin on the first day of summer, June 20th, and the series will run through to the end of the season, with a couple of posts each week, usually on Tuesdays and Fridays.

“A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” will feature guest posts by Maggie Arnold, Finola Austin, Elaine Bander, Deb Barnum, Sandra Barry, Cheryl Bell, Matthew Berry, Diana Birchall, L. Bao Bui, Kathy Cawsey, Carol Chernega, Lori Mulligan Davis, Lizzie Dunford, Susan Allen Ford, Paul Gordon, Collins Hemingway, Heidi L.M. Jacobs, Natalie Jenner, Hazel Jones, George Justice, Theresa Kenney, Deborah Knuth Klenck, Shawna Lemay, Emily Midorikawa, Jessica Richard, S.K. Rizzolo, Peter Sabor, Vic Sanborn, Marilyn Smulders, Jacqueline Stevens, Emma Claire Sweeney, Joyce Tarpley, Janet Todd, and Deborah Yaffe, along with two teenagers, Gail and Ria, who are reading S&S for the first time.

I’ve hosted blog series celebrations for Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, and I’m excited to read and celebrate Sense and Sensibility with all of you. Please share this invitation with anyone who might like to join us in discussing Austen’s first novel.

I’ll collect the links to all the posts in the series on this page, “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.”

In the fall, I’ll be hosting a blog series celebrating the 150th anniversary of L.M. Montgomery’s birth. I hope you’ll join us for that one as well!

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to my last two posts, in case you missed them:

“More than I can tell” (Quotations from Alice Munro)

“Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off?” (Photos from my trip to Oxford, Mississippi)

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

June 7, 2024

“More than I can tell”

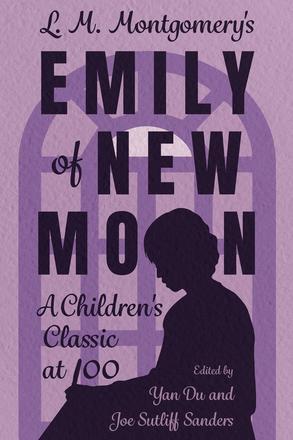

My title comes from Alice Munro’s afterword to L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon, in which she writes of the experience of reading the novel for the first time at age ten:

In this book, as in all the books I’ve loved, there’s so much going on behind, or beyond, the proper story. There’s life spreading out behind the story—the book’s life—and we see it out of the corner of the eye. The milk pails in the dairy-house. Aunt Elizabeth pouring the tallow for the candles. The slightly repulsive splendour of the parlour at Wyther Grange. The corners of the kitchen at New Moon. What mattered to me finally in this book, what was to matter most to me in books from then on, was knowing more about life than I’d been told, and more than I can tell.

(From the New Canadian Library edition of Emily of New Moon)

Munro quotes from another edition of Emily of New Moon, which claims on the cover that in this story the heroine discovers she is not alone, and she says she disagrees with this assessment of the novel. She objects to the “familiar brisk assumption” that books are supposed to “spread messages, and that the messages are cheery and confining.” She says she doesn’t know what book Montgomery intended to write, but the one she did write “is surely one in which Emily finds that she is alone, that she has chosen her life without knowing that she was choosing it, and she’s exultant about the choice.”

Like Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, who famously says “I care for myself” (Jane Eyre, Chapter 27), Emily Starr announces proudly, “I am important to myself,” after she’s been told she is “not of much importance” (Chapter 3). I like Munro’s word “exultant.” I was sad to hear of her death last month, at the age of 92, and I’ve been revisiting some of her writing and favourite quotations from her work.

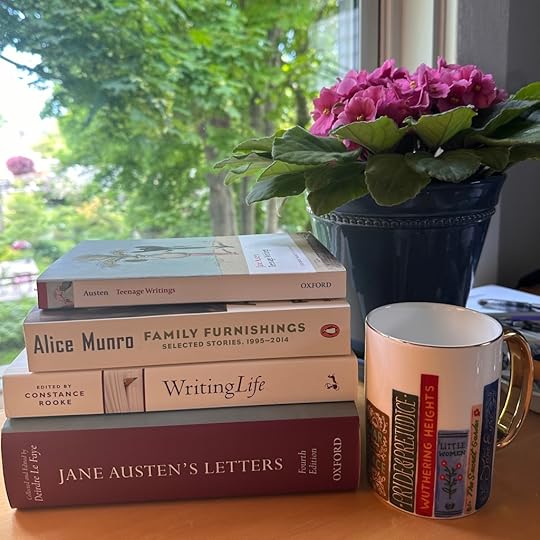

I like what she says about how “Writing fiction is seldom something that has to be done that day.” In a 2005 essay called “Writing. Or, Giving Up Writing,” Munro says, “in order to have time to do my work I must continually refuse to do things that other people think perfectly reasonable and even obligatory for me to do, and sometimes I get mad enough to tear out my hair.” As she reflects on her decision to give up writing, she asks what made writing “irresistible” in the first place.

She says it isn’t the work or sending the work out or seeing it published or reading it to an audience or seeing it on a bestseller list or seeing it win a prize. Instead, she asks, “Isn’t the really good time when you are just getting the idea, or rather when you encounter the idea, bump into it, as if it has always been wandering around in your head?” She says, “It’s not the story—it’s more like the spirit, the centre, of the story, something there’s no word for, that can only come into life, a public sort of life, when words are wrapped around it” (Writing Life, edited by Constance Rooke).

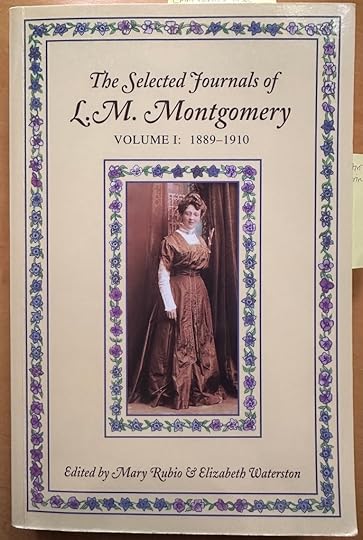

I’ve always liked Mary Henley Rubio’s story about the day she gave Munro a copy of the first volume of The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery in late 1985. Rubio says, “she looked at it for only a second to see what it was, and then, without missing a beat or without making any reference to Emily of New Moon, she responded by quoting the end of the novel: ‘I am going to write a diary that it may be published when I die’” (Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings).

I’m in the middle of writing an essay for this year’s JASNA AGM in Cleveland, Ohio. It’s called “‘She placed her bonnet on his head & ran away’: Stealing Sources and Avoiding Consequences in Jane Austen’s Fiction,” and I’ve been turning to Munro for that as well. I’m intrigued by what the narrator says in her story “Family Furnishings” about how planning to write fiction is “more like grabbing something out of the air than constructing stories.” I’m also rereading essays by Margaret Drabble, Eudora Welty, and other writers, exploring Drabble’s claim that “The ‘writing life’ is a life of crime.” (Like the Munro essay I quoted above, Drabble’s essay also appears in Writing Life, edited by Constance Rooke.) I’m especially interested in Austen’s heroine “The Beautifull Cassandra,” who steals a bonnet from her mother’s shop and runs off to seek her adventures.

If I start writing in detail about either the Beautifull Cassandra or Alice Munro’s stories right now, this will turn into a very long post. I’m tempted! It would be an excellent way to procrastinate. If I spent more time on Munro’s stories, I’d start with “Nettles,” one of my favourites. But I want to go back to working on my JASNA lecture, and so I’ll just add a wonderful quotation about Munro’s work from The Philadelphia Inquirer, and then I’ll end with some photos sent to me by my friend Sandra Barry.

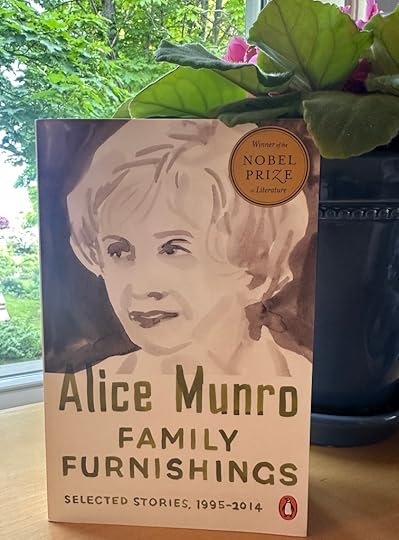

Munro was “A writer who slowly fashioned a house of fiction large enough for both a room of her own and all of her family furnishings—ensuring that she herself had space to maneuver while others still had plenty of space to stretch out and live. Those others include us, her very lucky readers.” (The Philadelphia Inquirer, quoted in Family Furnishings: Selected Stories, 1995-2014).

Photos by Brenda Barry, taken on a recent walk on a wetland trail in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. I’ll be back next Friday with details about my new blog series, “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which launches on June 20th.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to my last two posts, in case you missed them:

“Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off?” (Photos from my trip to Oxford, Mississippi)

“A beautiful voice” (#ReadingKilmeny)

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

May 31, 2024

“Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off?”

In Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass & Purveyor of Fine Footwear, by Heidi L.M. Jacobs, Molly isn’t sure if she’s falling in love with a man she has nicknamed “the Penguin Man.” If she is in love with him, she wonders if she’ll have to read the books he likes:

Am I in love with the Penguin Man? Can you just like being with someone and not be in love with them? Could I have fallen in love with him and not known? What does love feel like? Aren’t there supposed to be sparks? Isn’t your heart supposed to race? Might the shared love of an author mean you’re supposed to be with someone? Would he expect me to read Steinbeck? Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off? Is that what love does to a person?

(I wrote about Molly of the Mall last year: “Oh, novels! What would I do without you?”)

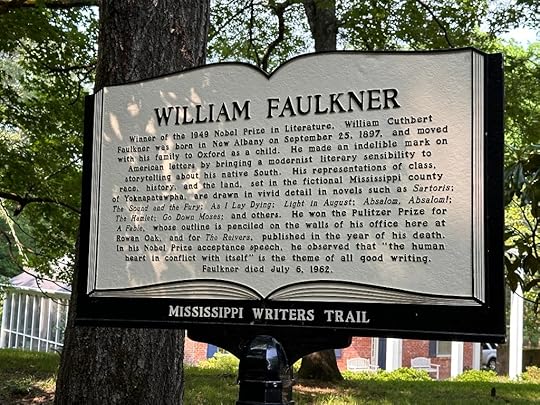

I was thinking of Molly last Saturday when I visited William Faulkner’s house, Rowan Oak, in Oxford, Mississippi.

I was in Oxford for a week, visiting my sister Bethie and her family, who moved there last summer after several years in Bonn, Germany. If you were following my blog last year, you might remember that when I visited Bethie there, she and I used to go for “coffee with Beethoven” in the Münsterplatz in Bonn. There’s a lovely café right next to the Beethoven statue. In Oxford, the café we went to was on the opposite side of the town square from the Faulkner statue, but it’s still pretty close, and on Saturday morning, we had “coffee with Faulkner.”

Bethie took this photo of Faulkner and me

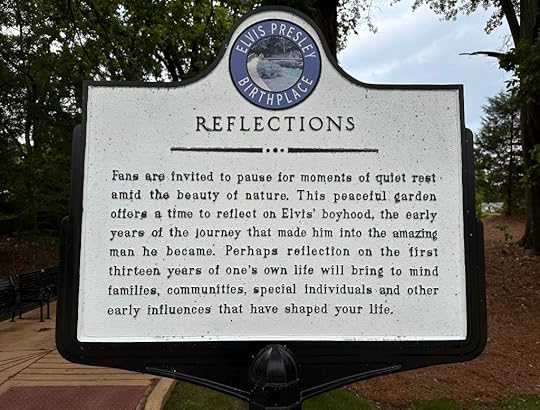

In the afternoon, I took my nieces to visit Rowan Oak, and we enjoyed exploring Faulkner’s house and gardens and the surrounding woods. I’ve read very little of Faulkner’s work and, like Molly, I’m not sure I want to start reading more. Nevertheless, I was interested to learn about the house, his office, and his family. I thought you might like to see some of the photos I took at Rowan Oak and elsewhere in Oxford. We also made a quick trip to Tupelo, where we visited Elvis Presley’s birthplace museum, and I’ll include those photos as well.

“… writing is a solitary job—that is, nobody can help you with it, but there’s nothing lonely about it. I have always been too busy, too immersed in what I was doing, either mad at it or laughing at it to have time to wonder whether I was lonely or not lonely, it’s simply solitary. I think there is a difference between loneliness and solitude.” (Faulkner at the University of Virginia, 1958)

“It was 1923 and I wrote a book and discovered that my doom, fate, was to keep on writing books: not for any exterior or ulterior purpose: just writing the books for the sake of writing the books….” (Foreword to The Faulkner Reader, 1953)

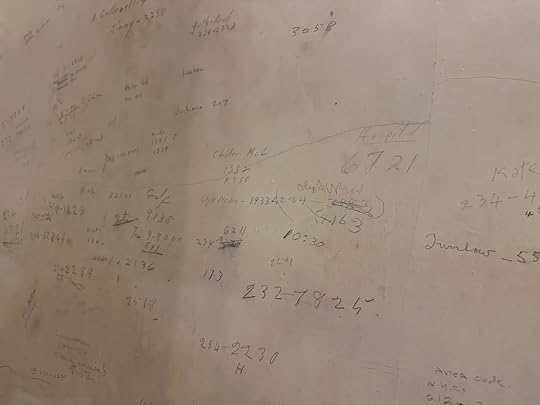

Faulkner liked to write on the walls of his house. Next to the telephone, he recorded phone numbers.

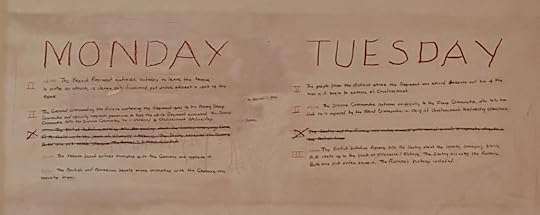

On the walls of his office, he wrote the outline of the plot for his novel A Fable, in graphite and red grease pencils.

“… of course the first thing, the writer’s got to be demon-driven. He’s got to have to write, he don’t know why, and sometimes he will wish that he didn’t have to, but he does.” (Faulkner at the University of Virginia, 1957)

English knot garden at Rowan Oak

I was interested to read that Faulkner hated air conditioning. His wife Estelle had an air conditioning unit installed in the window of her bedroom the day after his funeral. There’s a whole story behind that tiny detail. Makes me think of this famous six-word story: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn” (often attributed, probably incorrectly, to Ernest Hemingway).

In this case, I’d say: “Faulkner is dead. Let’s get A/C.”

A radio sits on the table next to the bed in Faulkner’s daughter Jill’s room. There’s a story here, too: Estelle gave the radio to Jill after Jill had had a “bitter fight with her father about technology,” according to the description posted on the wall outside the room.

Flowers in the Square in Oxford

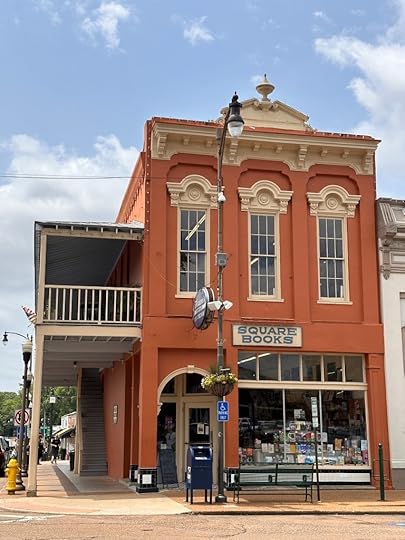

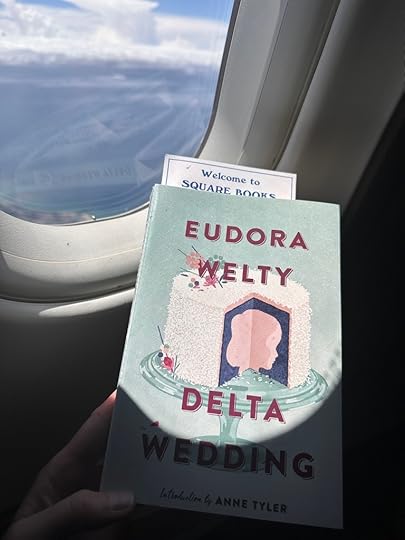

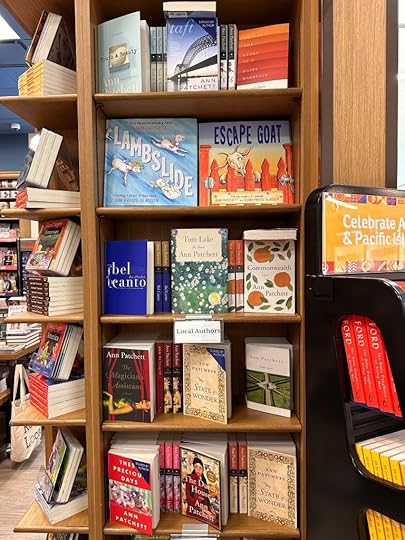

Square Books, Oxford, MS

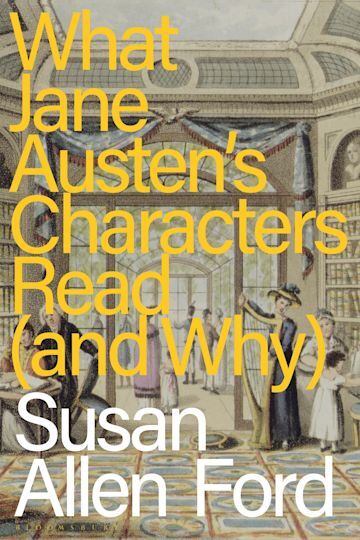

I had coffee at Square Books twice on this trip, once with Bethie and once with my friend Susan Allen Ford. I was delighted that Susan came to Oxford to see me. We’ve met up over the years at JASNA AGMs all over North America, but had never had the chance to meet in Mississippi, where she taught for many years at Delta State University. Susan’s book What Jane Austen’s Characters Read (And Why) will be published in July and I’m excited to read it. She’s writing a guest post for my blog series “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.”

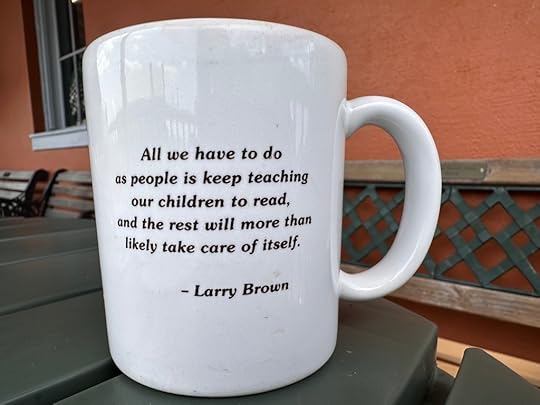

At Square Books, my coffee was served in mugs featuring quotations from Larry Brown and Eudora Welty. I didn’t get the mug with the Faulkner quotation about the tools he relied on to help him write: “paper, tobacco, food, and a little whiskey.”

“… it’s living that makes me want to write, not reading—although it’s reading that makes me love writing.”

– Eudora Welty

I also didn’t buy a Faulkner novel to read on the plane on the way home; instead, on Susan’s recommendation, I bought one of Eudora Welty’s novels. And Bethie bought me the Eudora Welty mug.

It took a long time to get from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Oxford, Mississippi, and back again—I flew to Nashville and then drove for about four and a half hours through Tennessee and Northern Mississippi—but it was worth it and I’m already looking forward to the next trip to see Bethie in her new home.

Flying into Nashville

The bend in the road in Mississippi

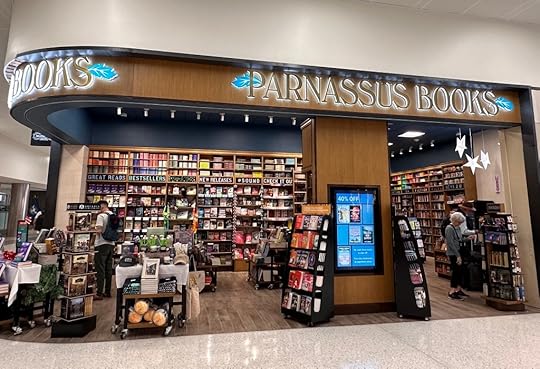

There’s so much more I could say about the trip—I haven’t even mentioned the Old-Time Piano Playing Contest and Festival that my niece and I went to last weekend, for example. I could also say more about Parnassus Books, at the Nashville airport, and about the University of Mississippi campus.

In the Nashville airport

Northern Catalpa Tree on the University of Mississippi campus

But this is already a long post, so I will end here with some photos from Elvis’s birthplace in Tupelo, and a photo of the sunrise from the airport hotel in Halifax, the night before I left for the long journey to Oxford.

The house where Elvis was born

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to my last two posts, in case you missed them:

“A beautiful voice” (#ReadingKilmeny)

“A rather doubtful experiment” (#ReadingKilmeny)

Posts by others who participated in #ReadingKilmeny:

From Hopewell’s Public Library of Life:

Review: Kilmeny of the Orchard, by Lucy Maud Montgomery

From Bookish Beck:

Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

From Naomi at Consumed by Ink:

#ReadingKilmeny: “She was, after all, nothing but a child…”

From Simpler Pastimes:

May 24, 2024

“A beautiful voice” (#ReadingKilmeny)

“I am not afraid of you now.” These are Kilmeny Gordon’s words the first time she responds to Eric Marshall in L.M. Montgomery’s Kilmeny of the Orchard (Chapter 7). She cannot speak, and thus she writes to him on a slate that she carries with her everywhere. The first time she saw Eric in the old orchard, she ran away from him. This time, she stays, and the next time, she brings her violin and plays “an airy delicate little melody that sounded like the laughter of daisies” (Chapter 8). Kilmeny communicates most clearly through her music.

Gardens of Hope, New Glasgow, PEI

Please join my friend Naomi and me this month as we read/reread Kilmeny of the Orchard. You can find the invitation to the readalong here. My first two posts on the novel were “A murmur that rings for ever” (#Reading Kilmeny) and “A rather doubtful experiment” (#Reading Kilmeny).

Elizabeth Rollins Epperly points out that “The narrator tells us that she writes little notes that show wit and humour, but we are never given any of these, and Kilmeny remains a beautiful picture,” even—spoiler alert—at the climactic moment when she warns Eric that his life is in danger (The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass). “In keeping with formula-romance roles,” Epperly writes, “Kilmeny does not have to do anything but look beautiful and act sweet for the world to be hers.”

Eric’s doctor friend, David Baker, turns out to be right that there is nothing wrong with Kilmeny’s vocal chords, and that a desperate need to speak will prompt her to do so. Once she has warned Eric, she finds that speaking is easy for her: “it seems to me as if I could always have done it.” Not surprisingly, she has “a beautiful voice—very clear and soft and musical” (Chapter 18).

I was interested to read Mary Henley Rubio’s suggestion that some of what happens in the novel parallels what was happening in Maud Montgomery’s life when she was writing it: Ewan Macdonald was courting her, and his courtship “allowed her to move beyond formulaic short stories and sentimental poems.” Rubio writes that “By freeing her from the fears of becoming a pitiful and voiceless old maid, Ewan’s love made her imagination soar and her pen sing” (Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings).

Ironically, however, although Montgomery may have felt more free to create Anne Shirley and other free-spirited girls and young women, Kilmeny is not like these heroines. Although Kilmeny of the Orchard is about a woman finding her voice, she is still bound by convention, and sometimes it seems that Kilmeny is barely allowed to be a character in her own story.

In the last chapter, after Kilmeny has discovered her voice and agreed to marry Eric, his father comes to meet her. Although Eric professes to love Kilmeny’s music and her voice, ultimately her beauty is shown to be more important. His father is skeptical about Eric’s choice, and Eric insists that he need only wait until he has seen her, for then he will understand. The two of them go to meet Kilmeny in the orchard, and this woman who has at last found her voice says—nothing at all.

Early in the novel, Kilmeny communicated by playing the violin and writing notes on her slate. In the end, she is shown reading—not writing, speaking, or playing music. Her figure, hair, and face are described in detail: it is her exceptional beauty, not her talent, her character, or her voice, that persuades Eric’s father she is the ideal bride for his son.

One way of ending this romance novel would have been to show Kilmeny speaking with her beloved. The girl who could not speak is transformed by true love: the story moves from her silence and isolation to a time in which she has captured the power of speech and will live happily ever after with the man she loves.

Instead, the ending is chilling. Kilmeny is shown without her violin or her slate. She could speak, but she does not. The ending is even more disturbing if we return to the parallels with Montgomery’s own life. Ewan’s courtship was a new beginning, but the freedom she found was limited.

I’m interested to hear what you think of Kilmeny of the Orchard—in the comments on this post, or on social media (Facebook; Instagram), or on your own blog. Thanks for reading with us!

I’m in Mississippi this week, visiting my sister Bethie and her family (and discussing Kilmeny, and admiring the spectacular magnolias). In my next post, I’ll share some more photos from the trip.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“A rather doubtful experiment” (#ReadingKilmeny)

“The murmur that rings for ever” (#ReadingKilmeny)

Posts by others who are participating in the readalong:

From Hopewell’s Public Library of Life:

Review: Kilmeny of the Orchard, by Lucy Maud Montgomery

From Bookish Beck:

Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

May 10, 2024

“A rather doubtful experiment” (#ReadingKilmeny)

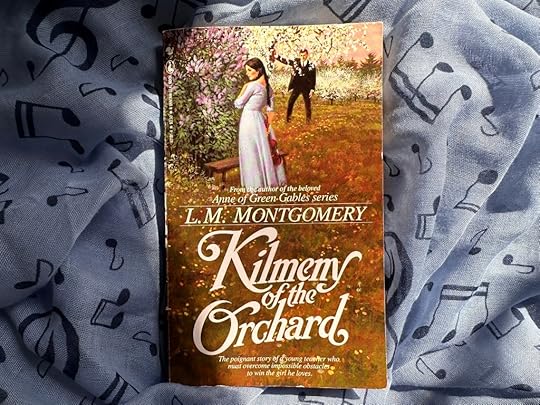

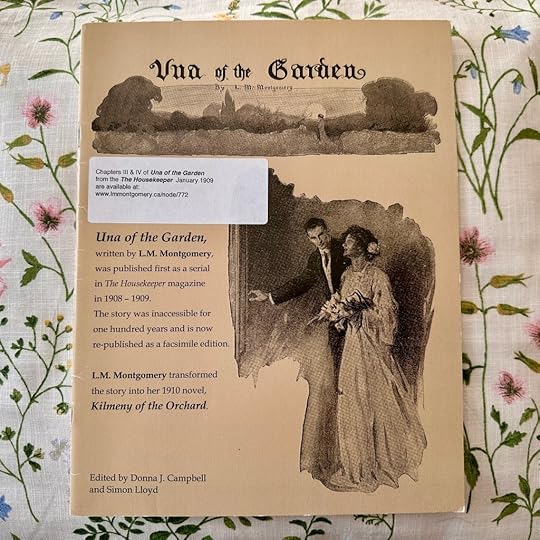

L.M. Montgomery’s third novel, Kilmeny of the Orchard, was published in 1910, following the phenomenal success of Anne of Green Gables in 1908 and Anne of Avonlea in 1909. Her publisher, L.C. Page, expected her “to produce one book after another at breakneck speed,” Mary Henley Rubio writes in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Although she would revisit—not always willingly—the world of Anne Shirley many times in the coming years, for this third book, Montgomery expanded a short story she had published between December 1908 and April 1909 in a magazine called The Housekeeper, a romance called “Una of the Garden.” Her hero, Eric Marshall, falls in love with a beautiful and talented violinist, Kilmeny Gordon, who plays pieces of her own composition in an old orchard not far from the house where Eric is boarding while he teaches at the local school in Lindsay, Prince Edward Island.

Please join my friend Naomi MacKinnon and me this month as we read/reread Kilmeny of the Orchard. You can find the invitation to the readalong here. I’ll be back later this month with another post on the novel.

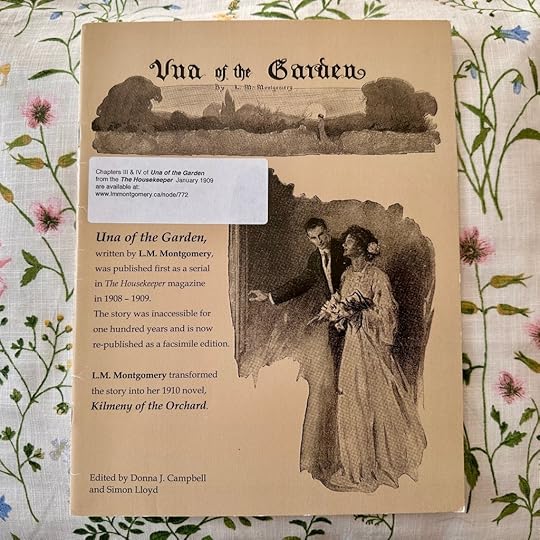

On a trip to PEI several years ago, I bought a facsimile edition of “Una of the Garden,” in which L.M. Montgomery is described more than once as “Author of Ann of Green Gables.” (No “e”! Unforgivable.) Her story appears alongside advertisements for Snider Pork & Beans (“People who can’t eat ordinary, indigestible, home-cooked Pork and Beans enjoy Snider’s”), Heatherbloom Taffeta Petticoats (“made in all the shades and stripes so modish to-day”), and Jell-O (“best for the whole family because it is delicious, pure, wholesome and nutritious”). When she revised and expanded the story, Montgomery changed the names of characters and places, including Una Marshall, now Kilmeny Gordon, and Eric Murray, now Eric Marshall. Neil Marshall, the orphaned son of “a couple of Italian pack-peddlers” who becomes Eric’s rival for the heroine’s affections, is renamed Neil Gordon. The setting is changed from Stillwater to Lindsay, and the garden is replaced by an orchard.

Montgomery was not happy about her publisher’s demands. Her original story was not long enough to please Page, “so I have had to re-write and lengthen it—a business I dislike very much,” she wrote in her diary in December 1909 (The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston). She had been working, she said, “until I would fairly feel faint with fatigue,” and she was afraid of the “terrible attacks of gloom and restlessness” that often tormented her. “If I can only keep physically well and nervously unbroken I shall not mind anything else so much.” Although Montgomery was tired, Rubio says that working on the novel served as a distraction, as she found that “writing could often help her block out worries in her real life. It was a pleasant way to escape.”

Montgomery wrote of Kilmeny that “It is a love story with a psychological interest—very different from my other books and so a rather doubtful experiment with a public who expects a certain style from an author and rather resents having anything else offered it.” Already she was facing the challenges of writing for an audience that was hungry for more Anne stories, and more books with a pastoral island setting.

In her new novel, she made PEI even more idyllic than in her first two “Anne” books. As Eric’s friend Larry West says in a letter when he is trying to persuade Eric to take his place as teacher in Lindsay for the last few weeks of the school year, “Prince Edward Island in the month of June is such a thing as you don’t often see except in happy dreams. There are some trout in the pond and you’ll always find an old salt at the harbour ready and willing to take you out cod-fishing or lobstering” (Chapter 2). The orchard, especially, is perfection:

Most of the orchard was grown over lushly with grass; but at the end where Eric stood there was a square, treeless place which had evidently once served as a homestead garden. Old paths were still visible, bordered by stones and large pebbles. There were two clumps of lilac trees; one blossoming in royal purple, the other in white. Between them was a bed ablow with the starry spikes of June lilies. Their penetrating, haunting fragrance distilled on the dewy air in every soft puff of wind. Along the fence rosebushes grew, but it was as yet too early in the season for roses. (Chapter 5)

As Elizabeth Rollins Epperly writes in The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance, “Montgomery makes the story pleasing to read and lifts it briefly beyond formula with her loving descriptions of sunset and garden.” Many of the passages about the setting are lovely, but sometimes I found them excessive. For example, “most of the idyllic hours of Eric’s wooing were spent in the old orchard; the garden end of it was now a wilderness of roses—roses red as the heart of a sunset, roses pink as the early flush of dawn, roses full blown, and roses in buds that were sweeter than anything on earth except Kilmeny’s face.”

Kilmeny is beautiful—there’s no doubt about that in this novel. She herself doesn’t know it, however, because her mother broke all the mirrors in the house and did not allow Kilmeny to see her own face. Kilmeny has never been able to speak, and the cause of her disability is mysterious. Is she physically incapable of speaking, or has her fate somehow been shaped by her mother’s “sin” (as her Aunt Janet Gordon believes), or is there some other reason she lacks a voice? Elizabeth Waterston says in Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery that “the ‘psychological interest’ comes from the doctor’s theory of psychosomatic impairment caused by ‘trauma’ and his hope that Kilmeny may be shocked into a cure.”

I’ll write more next time about Kilmeny’s inability to speak. For now, I want to ask what you think of Kilmeny, Eric, and Neil, the descriptions of the landscape, and Montgomery’s “experiment” in this novel. Did you find Kilmeny formulaic, as many reviewers and critics have suggested? “For the first time,” Liz Rosenberg writes in House of Dreams: The Life of L.M. Montgomery, “Maud’s work received negative reviews. One reviewer called it ‘a terrible specimen of the American novel of sentiment.’ Another said that the main character was enough to bring on ‘a bilious headache.’” Epperly says that “Everything in the novel belongs to formula,” including the character of Neil Gordon, the “dark, passionate, unscrupulous foreigner (Montgomery’s story makes unblushing use of xenophobia and bigotry).”

As I was reading the novel, for the first time since I was about ten or eleven, it occurred to me that while I found it engaging—and often disturbing—I probably wouldn’t have picked it up at all if it had been written by someone other than Montgomery. I wouldn’t say it gave me a bilious headache, but it isn’t my new favourite Montgomery novel, either. Even so, I’m finding it interesting to learn about how Kilmeny fits (or doesn’t fit) with Montgomery’s other novels, and where the novel falls in the development of her career. I wanted to reread this novel precisely because it doesn’t receive as much attention as the Anne and Emily books. And I was curious about the way Montgomery transformed “Una” into Kilmeny.

I came across this list of LMM books in my childhood library recently. I didn’t own Kilmeny of the Orchard (until I bought a copy a couple of months ago), and when I read it as a child, I must have borrowed it from the library. While I was sorting through notebooks and papers from elementary school, I also found this drawing of a bookshelf.

I’m keen to hear what you think—in the comments on this post, or on social media (Facebook; Instagram), or on your own blog—and I’ll look forward to continuing the conversation next week. Thanks for reading with us!

From Bookish Beck:

Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

“I found this fairly twee, with an unfortunate focus on beauty (‘“Kilmeny’s mouth is like a love-song made incarnate in sweet flesh,” said Eric enthusiastically’), and marriage as the goal of life. But it was still a pleasant read, especially for the descriptions of a Canadian spring.”

More photos of spring in Kent, sent by my friends Sheila and Hugh Kindred:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

May 3, 2024

“The murmur that rings for ever” (#ReadingKilmeny)

I’m looking forward to discussing L.M. Montgomery’s Kilmeny of the Orchard with you this month. My title for today’s post comes from the third chapter of the novel, in which the hero, Eric Marshall, has arrived in Lindsay, Prince Edward Island, to fill in for his friend Larry West as a teacher for the last week of May and all of June. Eric takes note of “distant hills and wooded uplands,” which are “tremulous and aerial in delicate spring-time gauzes of pearl and purple”; of “young, green-leafed maples” and “emerald fields basking in sunshine”; and of the “calm ocean,” which “slept bluely, and sighed in its sleep, with the murmur that rings for ever in the ear of those whose good fortune it is to have been born within the sound of it.”

When I was in PEI two weeks ago, the trees and fields weren’t yet green, but the ocean was calm. I took pictures of the water and dunes at Brackley Beach, along with pictures of trees and spring flowers and the sunset as seen from the window of my hotel room in Charlottetown.

St. Dunstan’s Cathedral, Charlottetown, PEI

Please join my friend Naomi MacKinnon and me this month as we read/reread Kilmeny of the Orchard. You can find the invitation to the readalong here.

I’ll have more to say next week about the publication of Kilmeny. Today, I want to share with you some more photos of spring, sent to me by my friends Sandra Barry and Sheila and Hugh Kindred. Sandra sent photos of Eastern Painted Turtles and wintergreen blooms, taken by her sister Brenda Barry in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. Sheila and Hugh sent photos of apple blossoms, cowslips, and bluebells in Kent, England.

I also want to draw attention to a new book that was published last month: L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon: A Children’s Classic at 100, edited by Yan Du and Joe Sutliff Sanders, and published by the University Press of Mississippi. In the three “Emily” books, Montgomery “turned from Anne and plunged into more intricate aspects of gender, adolescence, nature, and authorship,” and this book is “the first scholarly volume exclusively dedicated to the trilogy.” One of the contributors to the book, Lesley D. Clement, is writing a guest post for my blog series this fall, “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.”

More spring highlights:

My friend Meghan Marentette launched her debut picture book last Sunday at Woozles, one of my favourite bookstores. The book is called Rumie Goes Rafting, and features Rumie and Uncle Hawthorne in a forest setting where “The scent of dew filled the air, and the moss squished underfoot.” To Rumie, “Everything smelled like fresh adventure.” Meghan created the characters and all the props in this beautiful book, and photographed all the scenes in the woods near her home. She’s already working on a sequel, set in winter. If you’re interested, you can follow the complex and fascinating process of creating these books on Meghan’s Instagram.

Rumie in my back yard

Here’s a spring bouquet from my friend Kathy Cawsey, who wrote a guest post on Jane of Lantern Hill last May and is writing a guest post this year for my Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility:

I’ve been listening to The Blue Chapter of Project Earth, music composed by jazz pianist Florian Hoefner, featuring poetry by Don McKay and performed by the Iris Trio. Christine Carter, the Iris Trio clarinetist, was interviewed in this CBC article. The goal of Project Earth is to help “illuminate the impact of human behaviour on the environment … while also giving centre stage to the immense beauty and wonder found in nature.” Christine (whom I met last fall at Woozles) says that the project is “intimately connected” with the province of Newfoundland, where she lives with her family. “The arts can help people get their hearts involved,” she says, “so that we care about the numbers and want to make a difference.” The two other members of the trio are Anna Petrova, who lives in Louisville, Kentucky, and violinist Zoë Martin-Doike, who lives in New York City. I’m already looking forward to the Iris Trio’s Green Chapter of Project Earth: music by Sarah Slean and Andrew Downing, with poetry by Karen Solie.

One last note for today’s “scrapbook” post: have you read about Rabbit Hole, a new museum of children’s literature in North Kansas City, Missouri? I’d love to visit someday, and in the meantime, I enjoyed reading about exhibits that recreate scenes from beloved picture books such as Bread and Jam for Francis and Blueberries for Sal.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“A green solitude of wavering light and shadow” (photos of L.M. Montgomery’s grave in the Cavendish Cemetery, on the 82nd anniversary of her death)

Let’s read Kilmeny of the Orchard in May (#ReadingKilmeny)

More photos from Sheila and Hugh:

April 24, 2024

“A green solitude of wavering light and shadow”

In The Story Girl, L.M. Montgomery writes of the cemetery “where our kindred of four generations slept in a green solitude of wavering light and shadow” (Chapter 5). Here’s the cemetery where Montgomery herself and many of her relatives are buried:

These photos are from a summer trip a couple of years ago, when there was plenty of green in the cemetery. I spent last weekend in Charlottetown, PEI, and I stopped in Cavendish on the way there to take more photos. I was the only visitor at that moment. Plenty of solitude; not as much green, yet.

Montgomery died eighty-two years ago today, on April 24, 1942, and she was buried here five days later. Liz Rosenberg writes in House of Dreams: The Life of L.M. Montgomery that “The local outpouring of grief was immense. The little white church filled to overflowing. Mourners spilled out of the church and onto the grounds. The Cavendish school closed for the afternoon; grieving schoolchildren came running over. One girl remembered telling her mother, ‘I have read all her books and I know her.’”

More photos from last weekend: New London, L.M. Montgomery’s birthplace museum, and the National Park in Cavendish.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Let’s Read Kilmeny of the Orchard in May (#ReadingKilmeny)

Celebrating Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and L.M. Montgomery’s 150th Birthday

March 22, 2024

Let’s read Kilmeny of the Orchard in May (#ReadingKilmeny)

Please join my friend Naomi and me to read L.M. Montgomery’s Kilmeny of the Orchard in May. I thought I’d send out the invitation now to make sure anyone who wants to join us has time to read or reread the novel. Feel free to join the conversations in the comments on Naomi’s blog or mine, and if you write your own post about Kilmeny, please let us know.

I’m also planning to have a look at Montgomery’s story “Una of the Garden,” which she transformed into Kilmeny of the Orchard.

Here’s how Montgomery describes Eric Marshall’s discovery of the orchard (in the novel):

The charm of the place took sudden possession of Eric as nothing had ever done before. He was not given to romantic fancies; but the orchard laid hold of him subtly and drew him to itself, and he was never to be quite his own man again. He went into it over one of the broken panels of fence, and so, unknowing, went forward to meet all that life held for him.

I’m curious to read more, as I don’t remember the book very well at all. I think I was ten or eleven the last time I read it.

It’s spring in Nova Scotia and I was delighted to find crocuses in the back yard of our new house. In a recent essay, Margaret Renkl writes that “It’s been a dark winter of worries, but the wildflowers are blooming and the birds are singing again. It feels like coming home.” She says her “happiness is twofold. Spring is here! But also: Thank God it didn’t come too terribly early this year.”

(The snowdrops are from my mother’s garden. I took the picture of crocuses on a neighbourhood walk. Our crocuses are lovely, and this same shade of pale purple, but they’re more scattered through the muddy back yard and thus a little less photogenic.)

This year, the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies is sharing tributes to Montgomery from people around the world in honour of her 150th birthday (#Maud150). The editors recently posted three tributes on the theme of Spring Awakening, including one from Ukraine. Olga and Kateryna Nikolenko write that “For us here in Ukraine, L.M. Montgomery’s works hold a special significance throughout the times of war. A short while ago, Anne of Green Gables was introduced into the World Literature curriculum to read in the seventh and tenth grades—and now, Anne teaches Ukrainian students resilience, compassion, and optimism.” You can read the rest of the tribute here.

Here are a few other things I’d like to share with you:

Sheila Johnson Kindred has written a wonderful tribute to our dear friend Patrick Stokes, who died on Christmas Day, 2023.

Remembering Patrick Stokes, Admiral Charles Austen’s great great grandson

Sheila writes of the many conferences Patrick organized, including two here in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 2005 and 2017; of his keynote lecture at the JASNA AGM in Montreal in 2014; of his performance as the Prince Regent in Syrie James’s play “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park”; of the term he served as Chair of the Jane Austen Society, and of the assistance he offered when Sheila was writing her biography of Fanny Palmer Austen, Charles’s first wife.

I can still picture Patrick at the various Austen-related sites in the Halifax area that we visited during the 2005 and 2017 conferences, including Admiralty House; Government House, where Charles and Fanny Austen danced at a ball that Fanny described as “splendid”; and St. Paul’s Church, where their daughter Cassy was baptized in October 1809.

I met Patrick on the first day of the 2005 conference. He had invited me to be one of the speakers, and I was delighted to return home to Halifax from Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I was living at the time. Somehow, Patrick had discovered that the first day of the conference was also my birthday, and when I walked into the Admiral’s Room at the Lord Nelson Hotel, he surprised me with a beautiful bouquet of flowers. I soon learned that this generous gesture was characteristic of Patrick, an excellent host and an excellent friend. May he rest in peace.

I took this photo of Patrick at the 2017 conference:

Here’s some wonderful news from JASNA about Student Memberships:

“For the remainder of 2024 through 2025, we are excited to offer free one-year JASNA Student Memberships to the next generation of Austen fans and scholars. Don’t miss this unique opportunity to join our community. Keep up to date with the latest on Jane Austen and her works and connect with others in your area and beyond who share your admiration for this beloved and influential author.”

A few more photos of springtime in Nova Scotia, taken by Brenda Barry and sent to me by her sister Sandra: pussy willows, a Downy Woodpecker, and a ghostly moon:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Celebrating Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and L.M. Montgomery’s 150th Birthday

“Wondering what will happen next” (a “scrapbook” post that begins with Shawna Lemay’s new book Apples on a Windowsill)