Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 14

July 14, 2023

My Anne of Green Gables Pilgrimage—and Ladies of the Lake

“My love affair with books began at age seven,” says Syrie James in the guest post she wrote for my blog, about her love of L.M. Montgomery’s novels and a new Anne of Green Gables-inspired novel by Cathy Gohlke called Ladies of the Lake.

Syrie is the author of thirteen award-winning novels translated into twenty-one languages, including The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen, The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë, The Missing Manuscript of Jane Austen, Jane Austen’s First Love, and Dracula My Love. A member of the WGA, the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA), and the Historical Novel Society, Syrie has sold numerous screenplays to film and television, had stage plays produced from California to New York City and Montreal, addressed dozens of organizations, universities, and literary conferences, and has performed on stage numerous times as Jane Austen, most notably at Chawton House Library in England. She lives in Los Angeles, where she is writing her next book.

Syrie is a dear friend of mine, and my family and I have fond memories of the time we spent with her and her late husband Bill in Halifax and at the JASNA AGM in Montreal in 2014. I hosted a celebration of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park on my blog that year, and Syrie contributed a guest post “On Turning Down Marriage Proposals.” If you haven’t read her novels yet, you should! I’d recommend starting with The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen.

Here’s a photo of the two of us at the Montreal Botanical Garden:

Please join me in welcoming Syrie!

The Chinese Garden in the Montreal Botanical Garden

My love affair with books began at age seven. I was living in Paris with my family at the time, and my father (who worked at the Paris headquarters of IBM and was worried that, attending school in France, I might lose my command of English) brought me a box full of the best of children’s literature in English from a London bookstore.

Those books were more precious than diamonds to me. I devoured them all—The World of Pooh and The World of Christopher Robin by A.A. Milne, Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little by E.B. White, Pippi Longstocking and The Children of Noisy Village by Astrid Lindgren, and more than a dozen other fabulous reads including a nondescript paperback copy of The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. I own them all still. My hands down favorite was The Secret Garden. I re-read it so many times that I lost count. It instilled in me a fascination for the English countryside, English manor homes … and a desire to become a novelist.

Four years later, having moved back to California, I came upon Anne of Green Gables by L. M. Montgomery, in my middle school library. I fell in love with the feisty, whip-smart, romantic-minded Anne Shirley, and all her adventures in the lovingly-described Prince Edward Island setting. I identified in so many ways with Anne; she spoke to my heart. I read and started collecting every book by L.M. Montgomery that I could find.

My best friend Kimberly and I were such Anne of Green Gables fans that after we graduated from high school, we made a pilgrimage to Prince Edward Island, taking a summer road trip all the way across the U.S. from California to Eastern Canada. I have such wonderful memories of our magical week in PEI. We marveled at the red, red earth (that Anne celebrated in the novel), picked wild strawberries, splashed along the beaches, and strolled through endless fields of big white daisies. We stayed at a delightful farmhouse B&B near the coast where the owners, with great pride, shared a framed photograph of Queen Elizabeth’s visit in the late 1950s, when their farm was named the prettiest farm in Canada.

Kimberly, dancing down the “driveway” to the PEI farm

Teenage Syrie in Anne of Green Gables-land

We saw the musical Anne of Green Gables on stage in Charlottetown, and were thrilled to visit Green Gables, a farmhouse that belonged to L.M. Montgomery’s cousins and inspired the house in her books. At the time, the house was quietly situated on a remote crossroads in the countryside. Today, it’s part of Green Gables Heritage Place in Prince Edward Island National Park, and features lovely walking trails, farm outbuildings, and a huge visitor center and gift shop—the price of L.M. Montgomery’s fame! I made another pilgrimage there eight years ago with my husband Bill, and it’s a must-see for Anne enthusiasts.

Green Gables

“Anne’s Room” at Green Gables

Syrie and her husband Bill at Green Gables Heritage Place

French River, PEI

I am still in love with Anne Shirley, and all the other wonderful characters and splendid stories that L.M. Montgomery brought to life. When I need a comfort read, I turn to her novels. They are so real, they feed the soul, filled as they are with joy and heartaches, uplifting moments and deep challenges, and all the complexities of the human heart.

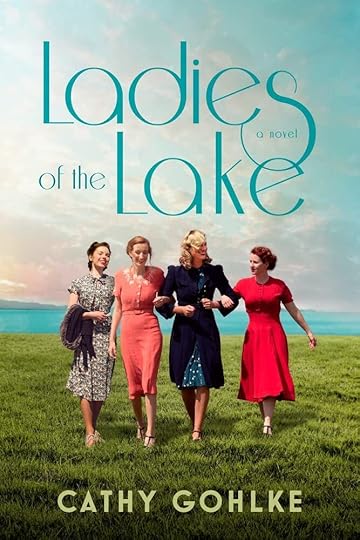

So, you can imagine how delighted I was to receive an advance copy of a new historical fiction novel, Ladies of the Lake by Cathy Gohlke, that is connected in several ways to Anne of Green Gables. It features an orphan girl from Prince Edward Island who loves the recently published novel Anne of Green Gables, dreams of becoming a novelist herself, and begins a correspondence with the real-life L.M. Montgomery! But that’s only a tiny fraction of what the story’s about.

Ladies of the Lake was published by Tyndale House Publishing earlier this week, on July 11, 2023. Here’s the book description:

When she is forced to leave her beloved Prince Edward Island to attend Lakeside Ladies Academy after the death of her parents, the last thing Adelaide Rose MacNeill expects to find is three kindred spirits. The “Ladies of the Lake,” as the four girls call themselves, quickly bond like sisters, vowing that wherever life takes them, they will always be there for each other.

But that is before: Before love and jealousy come between Adelaide and Dorothy, the closest of the friends. Before the dawn of World War I upends their world and casts baseless suspicion onto the German American man they both love. Before a terrible explosion in Halifax Harbor rips the sisterhood irrevocably apart.

Seventeen years later, Rosaline Murray receives an unsuspecting telephone call from Dorothy, now headmistress of Lakeside, inviting her to attend the graduation of a new generation of girls, including Rosaline’s beloved daughter. With that call, Rosaline is drawn into a past she’d determined to put behind her. To memories of a man she once loved . . . of a sisterhood she abandoned . . . and of the day she stopped being Adelaide MacNeill.

I adored this novel. I was hooked from the first chapter. There are so many suspenseful threads and need-to-know questions between the story in the 1930s and the earlier years (1910s – 1917) that I couldn’t put it down.

I loved the ways that L.M. Montgomery and Anne of Green Gables were included in the story. The school years when the four girls become close friends were exceptionally well done. The Prince Edward Island and Halifax locations were beautifully described. I’ve been to Halifax twice—once as a teenager, and again many years later with my husband, when I was lucky enough to visit my friend Sarah Emsley in her hometown. This novel evoked such wonderful memories of that trip! It was the first time I had heard of the Halifax explosion, a tragic historical event that is brought to vivid life and is a crucial turning point in the plot of Ladies of the Lake.

Visiting the Halifax Citadel

Canadian flag at the Halifax Citadel

What a page-turning tale! I was gripped by the emotional turmoil of the four women as adults, and holding my breath to see how it would all turn out. Author Cathy Gohlke spun it so well and so craftily that the final twist took me by complete surprise. I wondered how she was going to pull off a happy ending, but she did!

In her afterword, Gohlke writes that she was inspired by “the women characters we’ve loved through literature, women who stood in the gap for one another or helped each other grow—[like] Diana Barry and Anne Shirley in Anne of Green Gables … such bonds are precious and can prove life-sustaining through hard times.”

This is a brilliant story by an author at the top of her game, full of heartache, joy, pain, laughter, lessons learned, personal growth, and a lovely connection to God—and to Anne of Green Gables. I enjoyed it so much I’m going to read it again. 5 stars!

Syrie’s Website: https://syriejames.com/

Follow Syrie’s blog: https://syriejames.com/blog/

Sign up for Syrie’s newsletter: https://syriejames.com/newsletter/

Find Syrie on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/syriejames

Syrie’s Facebook Author Page: https://www.facebook.com/AuthorSyrieJames

Follow Syrie on Twitter: https://twitter.com/syriejames

July 7, 2023

“Heavens, I recognize the place”

I enjoyed revisiting the photos I took at the Elizabeth Bishop House in Great Village, Nova Scotia the last time I was there, and I hope you’ll enjoy them, too.

I spent a lovely afternoon at the house with my friend Sandra Barry in November of 2015, and I included some of the photos in a blog post a few days later. If you missed Sandra’s poem “Old Rusty Metal Things,” which appeared on my blog back in April, you can find it here.

Sandra will be reading from her work at the Elizabeth Bishop House tomorrow, Saturday, July 8th, along with Margo Wheaton, Rosaria Campbell, and Kayla Geitzler. The address is 8740 Highway #2, Great Village, Nova Scotia. (Event page on Facebook.)

The kitchen at the Elizabeth Bishop House:

Time to plant tears, says the almanac.

The grandmother sings to the marvellous stove

and the child draws another inscrutable house.

(from Elizabeth Bishop’s “Sestina”)

Why didn’t I know enough of something?

Greek drama or astronomy? The books

I’d read were full of blanks…

(from Bishop’s “Crusoe in England”)

“I stared and stared,” Bishop writes in “The Fish,” “until everything / was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! / And I let the fish go.”

“A scream, the echo of a scream, hangs over that Nova Scotian village. No one hears it; it hangs there forever, a slight stain in those pure blue skies…. Its pitch would be the pitch of my village. Flick the lightning rod on top of the church steeple with your fingernail and you will hear it.”

(from “In the Village”)

Think of the long trip home.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?

(from “Questions of Travel”)

Heavens, I recognize the place, I know it!

It’s behind—I can almost remember the farmer’s name.

(from “Poem”)

A few months ago I looked up Bishop’s poem “In the Waiting Room” on my phone, when I was in a hospital waiting room. The person I was waiting for was having emergency surgery—and is now, thankfully, recovering well. But I didn’t know that would be the result during those hours I spent in that room.

It was Good Friday, a sunny spring afternoon, and the waiting room and hallways were empty. No one sat at the reception desk; no nurse came out to say anything to me. No copies of the National Geographic were waiting for me in that room. A small poster announced a campaign for “Doctors Helping Ukraine.” I studied the reflections of fluorescent lights on the plexiglass walls that divided the chairs from each other. I took photos of reflections and empty chairs. I had brought a book, but I realized what I wanted was Bishop’s poem.

I said to myself: three days

and you’ll be seven years old.

I was saying it to stop

the sensation of falling off

the round, turning world

into cold, blue-black space.

But I felt: you are an I,

you are an Elizabeth,

you are one of them.

Why should you be one, too?

I scarcely dared to look

to see what it was I was.

I read the poem twice, and wondered with Bishop, “Why should I be my aunt, / or me, or anyone?” And then I fell asleep, my head resting against one of the plexiglass walls.

June 30, 2023

“Reading shaped my dreams”

“Reading shaped my dreams, and more reading helped me make my dreams come true….”

– Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Last week I spent a few days in New York City with my parents and my daughter, celebrating my daughter’s 16th birthday. We had a fabulous time! Some of the highlights: Like Water for Chocolate at the American Ballet Theatre’s Summer Gala at the Metropolitan Opera House, the Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition “To See Takes Time” at the Museum of Modern Art, and an exhibition of treasures from the collections of the New York Public Library. I was happy to see the portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft and six copies of Shakespeare’s First Folio—and especially happy to see the latter with my father, who’s a Shakespeare scholar.

We also enjoyed visiting the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, St. Thomas Church Fifth Avenue, St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral, the High Line, and the Columbia University campus, where the above quotation from Ruth Bader Ginsburg is featured at the entrance to the university bookstore.

Three Lives & Co., in Greenwich Village:

The Metropolitan Opera House:

Flamingos at Lincoln Center:

“To see takes time—like to have a friend takes time.” – Georgia O’Keeffe

The New York Public Library:

The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine:

St. Thomas Church, Fifth Avenue:

Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral:

The High Line at sunset:

My daughter and me at Nami Nori in Greenwich Village:

And here’s a photo she found from the year she turned seven:

(As my friend Lyn said on Facebook, “she sure showed that salad who’s boss!”)

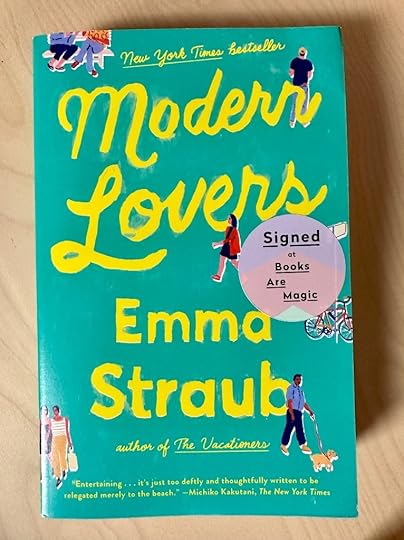

We loved exploring bookstores, including The Strand, Three Lives & Co., and the second location for Books are Magic in Brooklyn (my daughter and I had visited the original location last summer).

Do any of you have recommendations for bookstores—or other favourite places—to explore on a future trip to NYC? As I wrote here last fall, reading is my anchor, and I love what RBG says about how reading has the power to shape our dreams and make them come true.

My parents browsing at Three Lives & Co.:

A bookseller at Three Lives & Co. recommended Taco Mahal, in the West Village, and we went there for lunch on my daughter’s birthday:

Stonewall National Monument garden:

While we walked across the Brooklyn Bridge to visit Books Are Magic, we watched these people climbing the bridge:

The second location of Books Are Magic, on Montague St.:

I bought a copy of Emma Straub’s novel Modern Lovers at Books Are Magic (she and her husband, Michael Fusco-Straub, are co-owners of the store). I had read a library copy a few years ago, and I wrote about the novel here. Straub’s heroine Elizabeth writes a song called “Mistress of Myself,” inspired by a line from Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility: “I will be calm; I will be mistress of myself,” thinks Elinor Dashwood.

June 23, 2023

Excellent Women (Writers): The Significance of Smallness

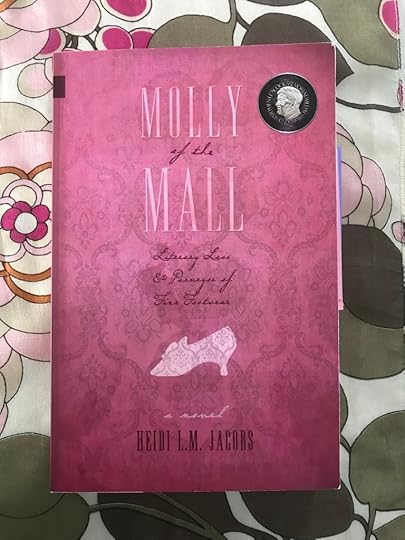

I adored Molly of the Mall, Heidi L.M. Jacobs’s debut novel, which longtime readers of my blog will know because I’ve written about it at length (in a post that borrows a quotation from the novel’s heroine, Molly, for its title: “Oh, novels! What would I do without you?”). Molly’s experience as the child of graduate students in Edmonton, Alberta, and then as a student in the English Department at the University of Alberta was so close to mine that sometimes I felt as if I were reading about my own life.

My sister Bethie, who’s a decade younger than I am, said that after she read Molly of the Mall she felt as if she knew what my undergraduate experience had been like in the early 1990s (living—I’m quoting from the novel here—“in one of those walk-up apartments off Whyte Avenue with misleadingly elegant names like The Alhambra or The Loch Lomond,” creating mix tapes with literary references, working in an Edmonton mall, going to movies at the Princess Theatre, watching A Room With a View, and so on).

Although Heidi and I were students at the University of Alberta around the same time, somehow we didn’t meet. I was delighted to meet her online after she commented on my blog post about her novel, and of course I couldn’t resist asking if she’d like to write a guest post someday. It’s a great pleasure to introduce her guest post on “Excellent Women (Writers).”

Heidi L.M. Jacobs is a librarian at the University of Windsor, and she has a PhD in 19th Century American Women’s Literature. In addition to her novel, Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass & Purveyor of Fine Footwear, which won the 2020 Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour, she’s the author of 100 Miles of Baseball (with Dale Jacobs). Her newest book, 1934: The Chatham Coloured All-Stars’ Barrier-Breaking Year, was published earlier this month—congratulations, Heidi!

Heidi says, “I’m never sure when a photo of me wearing a seafoam green ball gown at a Scottish dance formal is professionally appropriate but this seems like the perfect (only?) opportunity!”

Over the past three very strange years, I’ve become irretrievably hooked on a particular kind of book by mid-20th-century women who I’ve come to call Excellent Women (Writers). It’s not only that writers such as Barbara Pym, Elizabeth Taylor, Maeve Brennan, Mary Lavin (1912-1996) are excellent—it’s that Pym’s 1952 novel, Excellent Women, made me notice something about the books that resonated with me. What Pym’s novel made me notice was smallness. While smallness is often conflated with insignificance, in the writings of these Excellent Women, smallness is actually what is significant.

In July of 2022, I re-read Excellent Women for the first time in over thirty years. At the time, I was also trying to process the impact of the previous two years’ social distancing, isolation, working from home, and existing for the most part within 50 kilometers of my house. I had come to see the merits of making one’s world smaller and finding meaning in smallness.

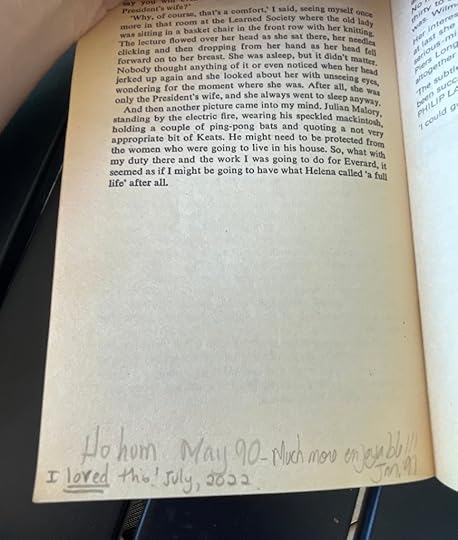

The copy of Excellent Women I re-read was the one I purchased in the spring of 1990 for a course I had signed up for in the 1990-91 academic year with Dr. Nora Stovel at the University of Alberta. My copy of Excellent Women—pictured here with its ghastly 1980s cover—has a notation on the final page that says when I read it first in May 1990, I found it “ho hum.” When I re-read it in January 1991, I found it so “much more enjoyable” that it merited three exclamation points. As you can see, when I re-read this book in July of 2022, I “loved it” enough to underscore “loved” twice and use an exclamation point.

As I look at my copy today, I notice that in 1991 and in 2022, I made note of these lines of Pym’s: “I wondered that she should waste so much energy fighting over a little matter like wearing hats in chapel, but then I told myself that, after all, life was like that for most of us—the small unpleasantnesses rather than the great tragedies, the little useless longings rather than the great renunciations and dramatic love affairs of history or fiction.” I think what I loved so much about Excellent Women this time around—thirty-two years after I’d thought it was “ho hum”—was that I was old enough to see the “smallness” of life, the “useless longings” in new ways as well as the importance of the non-dramatic.

Pym’s novel deals with these smallnesses thematically but her prose is brilliant because she makes the small do a lot of work. For example, after Mildred Lathbury indulgently purchases a “Hawaiian Fire”-coloured lipstick at a department store and ventures to the ladies room, she describes the scene as

“a sobering sight indeed and one to put us all in mind of the futility of material things and of our own mortality. All flesh is grass… I thought, watching the women working at their faces with savage concentration, opening their mouths wide, biting and licking their lips, stabbing at their noses and chins with powder puffs. . . Later I went into the restaurant to have tea, where the women, with an occasional man looking strangely out of place, seemed braced up, their faces newly done, their spirits revived by tea. Many had the satisfaction of having done a good day’s shopping when they got home. I had only my Hawaiian Fire and something not very interesting for supper.”

These small details, small actions bring the power of Pym’s prose to the surface.

Once I started thinking about these poignant and moving smallnesses in Pym, I saw them again in many of the books I was reading and loving by mid-century writers. The writings by Irish short story writer and essayist Maeve Brennan (1917-1993) have a sort of explosive economy of word, phrase, and emotion. Take for example, this single sentence from Brennan’s essay called “I wish for a little street music”: “The father stared admiringly up at his son, hearing every word, and you could see that what he longed for was to have the chance, just once again, to pitch his child up and walk a few steps with him in his arms” (The Long-winded Lady). Again, a tiny moment but it captures something immensely powerful.

I also came to see what was funny in many of these books was the smallness of the jokes. You could almost miss them but when you see them, they’re like a shared joke with a good friend. Like Rachel Ferguson’s (1892–1957) quirky The Brontës Went to Woolworths (1940): “I thought perhaps she might be one of those sort of writers—like Thomas Hardy— who sounded as if they ought to be dead before they really were” (125). Or this passage from Nancy Mitford’s (1904-1973) The Pursuit of Love (1945): “The Ratletts considered that Tony was a first-class bore. He had a habit of choosing a subject, and then droning around and round it like an inaccurate bomb aimer round his target, ever unable to hit.” I think we’ve all read writers like Ferguson and met a more than a few Tonys.

But there are writers like Elizabeth Taylor (1912-1975) whose poignancy comes from the depth she forges within a deceptively small scope. This first paragraph of the quiet yet gutting Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont (1971) captures what is so evocative about Taylor’s prose: “Mrs Palfrey first came to the Claremont Hotel on a Sunday afternoon in January. Rain had closed in over London, and her taxi sloshed along the almost deserted Cromwell Road, past one cavernous porch after another, the driver going slowly and poking his head out into the wet, for the hotel was not known to him. This discovery, that he did not know, had a little disconcerted Mrs Palfrey, for she did not know it either, and began to wonder what she was coming to. She tried to banish terror from her heart. She was alarmed at the threat of her own depression.” Nothing huge happens in this novel but yet, when you’re done, it feels like you’ve experienced something enormous. It is huge in its smallness.

To return to Barbara Pym: life is “like that for most of us.” It’s the small things that matter not the huge things—“the small unpleasantnesses rather than the great tragedies.” When I think about that passage from Excellent Women that I underlined twice—thirty some years apart— I wonder if, perhaps in 1991 my young self saw the lines about “the little useless longings rather than the great renunciations and dramatic love affairs of history or fiction” as foreshadowing or words of caution. I do know that in 2022, Pym gave me a quiet articulation of something deeply and wordlessly resonant.

Note on the photos: As a kitten my cat Gracie loved to nibble the corners off paperbacks—mostly fiction. She doesn’t eat many books but still loves to read. Check out #graciereads (# not @) on Instagram.

June 16, 2023

“A grey cloak and an umbrella”

Today’s guest post is on Bleak House, by Charles Dickens. My high school friend Maggie Arnold has contributed several wonderful guest posts for my blog over the years, most recently on Jane Austen’s Persuasion, and I was very happy that she agreed to write a guest post for this new series in which I ask friends to recommend some of their all-time favourite books, and/or books they’ve read recently.

The Rev. Dr. Maggie Arnold is the Rector of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Cohasset, Massachusetts. She lives with her husband Christopher, and her children Rose and Clara, as well as their dog and cat. Maggie studied printmaking and bookbinding before going on to seminary and doctoral work in the religion of the Early Modern Period. Her book, The Magdalene in the Reformation, was published by Harvard University Press in 2018. She is currently working on a history of the Boston Episcopal Charitable Society, the second oldest charity in the United States.

I took this photo of Maggie’s book next to a gorgeous print she created when she was in art school and gave to my husband and me as a wedding present.

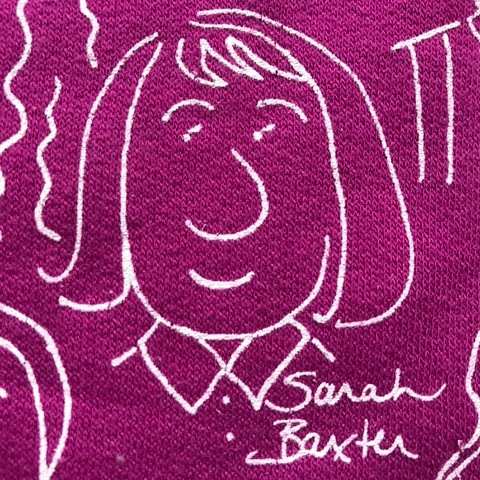

Maggie and I met on the first day of grade eleven in Halifax, and have been friends ever since. For six years, when we were both living in the Boston area, we were able to see each other relatively often, and in the years since my family and I moved back to Canada, we’ve been grateful for many visits in both Nova Scotia and Massachusetts. Back in 1991, Maggie designed a sweatshirt featuring images of the members of our (very small—there were fourteen of us!) graduating class. Now that I’ve shared a recent photo of her with you, I thought I’d also add the sketches she drew of the two of us when we were seventeen. My daughter is currently a student at the same school, and I keep threatening to embarrass her by wearing this old and beloved sweatshirt to an event—maybe next year’s gala fundraiser??

Please join me in welcoming Maggie!

I was so excited when Sarah asked me if I would consider writing a post for this series! I have used books therapeutically for years. A favorite author’s voice can be a way to turn my mind along better channels, if I have gotten into a muddy rut of self-pity or confusion. Jane Austen, for example, always gives me a sense of perspective: humour and also the goal of a life well spent, measuring one’s words and offering the best of one’s self to the relationships that mean most: our family and dear friends, the community around us. C.S. Lewis helps guide me back to the basics of Christianity, a no-nonsense approach to being on a journey with and toward God, staying humble and avoiding the pitfalls of trendy ideas.

One of my most beloved authors is Charles Dickens, whose compassionate vision seems to comprehend every story, every kind of life—urban and rural, male and female, rich and poor, generously busy and sadly constricted. His wide-ranging narratives encourage a curiosity about the human experience which I find deeply faithful. The worst sin, for Dickens, is indifference, and he does the work of combating that temptation for us; who could be indifferent to portraits drawn with such a knowing eye?

Sometimes I go to a cherished book seeking renewal for mind and spirit, but often what I need is more mundane, inspiration for the repetitive tasks of daily life as they add up over time. Dickens’ Bleak House contains multitudes, but at its edges is one small family and their home. We see them only briefly, introduced in the chapter “More Old Soldiers Than One,” but their effect on me is always so invigorating, like a breath of sea air. Mr. and Mrs. Bagnet were soldiers of empire, and are only recently settled in England after a career abroad. The names of their daughters, Quebec and Malta, testify to their birthplaces in far-flung outposts during the course of Matthew Bagnet’s military career (their son, “young Woolwich” indicates their retirement to London).

Despite Matthew’s service, it is Mrs. Bagnet who takes the commanding role in the family, and we see her strong but gentle husband deferring to her opinion on every question, as he admits, “It’s my old girl that advises. She has the head.” She herself is a marvel in nineteenth-century literature (or any literature, really), a middle-aged woman who is admirably resourceful, crisply efficient, cheerful and loving, devoted to the care of her family and yet neither officious nor resentful. Her presence in the book provides an antidote to the character of Mrs. Jellyby, also a fixture of British imperial culture. Where Mrs. Jellyby’s charitable projects for African orphans cause her to neglect her own children and household to the point of endangering her family and guests, Mrs. Bagnet capably sets her sights on what is near and dear. As a result, her home is a place of welcome refuge for the troubled Mr. George, her husband’s friend and fellow officer.

Her appearance speaks of the outdoors, “freckled by the sun and wind,” and her only ornament is her wedding ring, betokening her commitment to her marriage and its offspring. She looks after their finances and feeds her family a nutritious, frugal diet, as Mr. George recalls, “I never saw her, except upon a baggage-wagon, when she wasn’t washing greens!” Their home is simply furnished “and contains nothing superfluous, and has not a visible speck of dust or dirt in it.” The cleanliness and order, according to her “exact system,” are the manifestations of her good sense and thoughtful provision for her family. Her daughters are learning to read and to sew, accruing wisdom both intellectual and practical, Woolwich plays a patriotic fife, and they all help their mother with the domestic chores. Elsewhere we learn more of her history, and how she has been able to make a home anywhere she has traveled, which she has done independently, “with nothing but a grey cloak and an umbrella.”

Possessed of a sterling integrity that has stood the test of time, Mrs. Bagnet is untarnished by the world’s corruption, growing older with her husband as they raise their children, yet remaining along with him, in Dicken’s judgment, “simple and unaccustomed children themselves” in the ways of greed and deceit. To gain experience while staying young at heart—that continues to be my hope for each day, as I try to care for my own family, making a home and facing life’s challenges.

Mr. George and Matthew Bagnet together offer her the ultimate praise: George remarks that she looks as fresh as a rose, and as sound as an apple. “The old girl,” says Mr. Bagnet in reply, “is a thoroughly fine woman. Consequently, she is like a thoroughly fine day. Gets finer as she gets on. I never saw her equal.”

Here are the other guest posts Maggie has written for my blog over the years:

“What Women Most Desire: Anne Elliot’s Self-discovery” (for my blog series “Youth and Experience: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion”)

“Emma Woodhouse as a Spiritual Director” (for my blog series “Emma in the Snow”)

“‘Born again’: Valancy’s Journey from False Religion to True Faith” (in L.M. Montgomery’s novel The Blue Castle)

“Discerning a Vocation in Mansfield Park—But Whose?” (for my blog series “An Invitation to Mansfield Park”)

Previous posts in this series featuring book recommendations:

“Reading Close to Home,” by Naomi MacKinnon

“What is Said and What is Not Said,” by Jill MacLean

“Words that Heal,” by Renée Hartleib

June 9, 2023

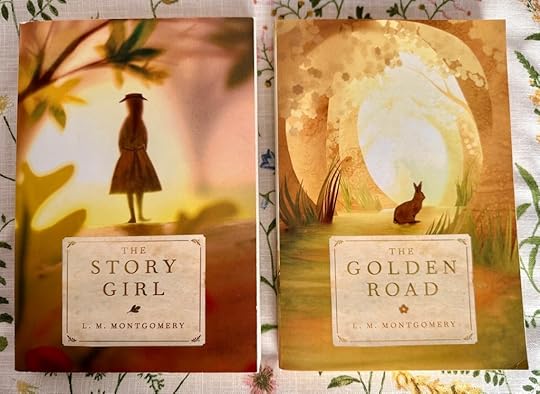

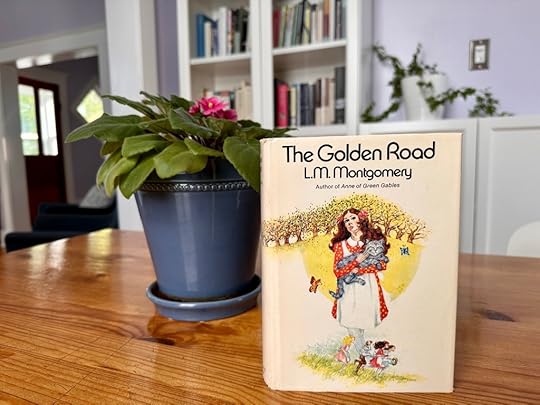

An Invitation to Read The Story Girl and The Golden Road

Let’s read L.M. Montgomery’s novel The Story Girl and its sequel, The Golden Road, together this fall. My friend Naomi and I enjoyed discussing Jane of Lantern Hill with you last month, and we’ve decided to read The Story Girl next, in November. I hope you’ll join us!

I haven’t read these books since I was about ten or eleven, and for the most part I’m excited to revisit them, though I admit to a small amount of apprehension. As I mentioned when I wrote about rereading Jane of Lantern Hill, I found some aspects of the book disappointing. Even so, I’m glad I read it again.

I’m going to borrow my daughter’s copies of the beautiful Tundra editions of these novels, featuring cover art by Elly MacKay.

I also have the copy of The Golden Road that I read in the early 1980s, but for some reason I don’t have a copy of The Story Girl, which surprised me because in those years I was building an L.M. Montgomery collection.

Probably I’ve written here before about how on Saturday mornings after he picked my sister Edie and me up from our ballet classes, my father used to take us to a bookstore on the Halifax waterfront called A Pair of Trindles, which carried books by Canadian authors only. I saved my allowance to buy one Montgomery novel at a time, often the McClelland & Stewart “Canadian Favourites” editions.

I’m announcing the readalong now so that everyone who’s interested will have lots of time to get ahold of copies of these books and start reading. The hashtag (for both novels) will be #ReadingStoryGirl. Please join the conversations on Naomi’s blog, Consumed by Ink, and mine, and/or on social media and your own blog, if you like.

I love the first sentence of The Story Girl:

“I do like a road, because you can be always wondering what is at the end of it.”

Already the Story Girl sounds like Anne Shirley, who tells Marilla near the end of Anne of Green Gables that she’s optimistic about her future, which used to “stretch out before me like a straight road”:

Now there is a bend in it. I don’t know what lies around the bend, but I’m going to believe that the best does. It has a fascination of its own, that bend, Marilla. I wonder how the road beyond it goes—what there is of green glory and soft, checkered light and shadows—what new landscapes—what new beauties—what curves and hills and valleys further on.

The bend in the road in Fredericton, PEI

On a completely different topic, I also want to tell you about a literary event that’s coming up in early July. My friends Sandra Barry and Margo Wheaton will be reading from their poetry at the Elizabeth Bishop House in Great Village, Nova Scotia on Saturday, July 8th, in the afternoon. Regular readers of my blog will probably remember Sandra’s poem “Old Rusty Metal Things,” which I shared here in April. If you’re in the area, I hope you’ll consider making the trip to the EB House for what I’m sure will be a wonderful event. (I’m not sure of the precise time yet, but if you’re interested, please comment on this post and I’ll get back to you with more details.)

The Elizabeth Bishop House, Great Village, NS

Here are some photos Sandra sent me recently, taken by her sister Brenda Barry. The first, in Sandra’s words, is “a sweet song sparrow singing to the sun. I love hearing them sing—this one was singing and singing and singing—clearly out of pure, sheer joy.”

Tree Swallow

Redstart

Hummingbird

And some iris photos, also by Brenda:

If you missed any of the Jane of Lantern Hill posts and would like to catch up, you can read more here:

From me:

“Back in Bonn with Bethie, #ReadingLanternHill”

“The Idyllic Island (#ReadingLanternHill)”

From Kathy Cawsey:

“She is my daughter … no outsider shall ever come between us again” #ReadingLanternHill

From Naomi MacKinnon:

“Announcing a Readalong of Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery: #ReadingLanternHill”

#ReadingLanternHill: My Thoughts on Jane of Lantern Hill, Anthropomorphism, and Squishmallows

From Rebecca Foster:

“Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery (1937) #ReadingLanternHill”

From Bill at The Australian Legend:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. Please help spread the word about our readalong for The Story Girl and The Golden Road!

I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. If you’d like to subscribe and receive future posts by email, you can sign up on my website, www.sarahemsley.com. Thanks very much for reading.

June 2, 2023

Words that Heal

My friend and neighbour Renée Hartleib is the author of today’s guest post, and it’s a great pleasure to introduce her. Renée is an author, writer, and writing mentor, and she says her “greatest passion is to help others connect with themselves and bring their creative dreams to life.” She lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with her family, one dog, many felines, and a “book nook” in front of the house.

Her book Writing Your Way: a 40-Day Path of Self-Discovery was published last fall. I attended the launch at the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia and there was a tremendous amount of positive energy in the room as so many people gathered to celebrate Renée and her fabulous new book.

The book arose from the “40-Day Writing Project” she designed and has shared many times with different groups over the last few years. (You can find more details about her online writing community and sign up for her monthly emails on her website. If you’re looking for a writing mentor or editor to help you finish a book or assess a first draft, get in touch with Renée directly. She’s a fantastic editor and coach and I recommend her highly!) Each chapter begins with an inspirational quotation—such as Rainer Maria Rilke’s famous advice about learning to “live the questions”—followed by compelling stories from Renée’s own creative journey, along with writing prompts designed to help readers explore their own lives, past and present, and their dreams of renewal and transformation for the future. As I mentioned when I wrote about the book here last fall, when I read it I was reminded of what Jane Austen’s Fanny Price says in Mansfield Park about how “We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be.” Renée suggests that writing can help us find that “better guide”—she says, “Some might call it your soul, your spirit, or your essence.”

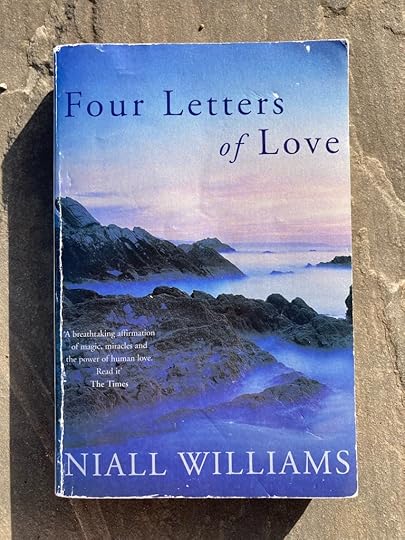

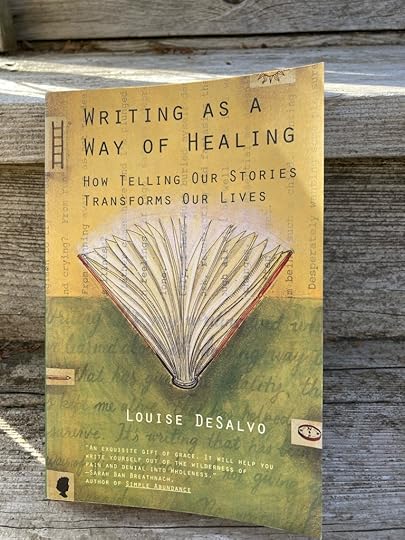

I’m delighted to share with you Renée’s guest post about three of her favourite books, Four Letters of Love, by Niall Williams, The Camino Letters: 26 Tasks on the Way to Finisterre, by Julie Kirkpatrick, and Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives, by the late Louise DeSalvo.

Thank you to Sarah for inviting me to write a guest post on her wonderful blog! I’m excited to tell you about three of my favourite books. While they are all different genres they share a common thread. There’s a book of fiction I have long loved, a memoir I just finished, and a non-fiction book I return to again and again in my life and my work.

Four Letters of Love by Niall Williams is a novel I first read over twenty years ago and have re-read many times since. Whenever anyone asks me about “favourite books of all time,” it’s there. First because the writing is exquisite, but also because of the book’s powerful and overarching message of love and goodness, even in the face of obstacles, other people’s bad behaviour, and unfair twists of fate.

The book is set in Ireland and when it begins, our narrator, Nicholas Coughlan, is twelve years old. His world has just been turned upside down by his father, the family’s primary breadwinner, who has left his job and decided to paint for a living because God asked him to. Woven throughout this first person account are other chapters, written in the third person, that tell the story of another character, Isabel Gore. She lives on an island off the Galway Coast and feels haunted by, and responsible for, her younger brother’s physical paralysis.

There is an old-fashioned love story at work here, but simultaneously author Niall Williams writes about divine love and self-love and how healing is possible. It’s about the love that shines—like a shot of sunlight on the sea—through our moments of nearly unbearable sadness and grief. He reminds us what it means to trust in life and to trust in something larger than ourselves.

“There was in the air at that moment that rare feeling of healing, of things lifting and coming together, of the story being carried suddenly forward, the great whoosh on which everything suddenly rises and flows, and you know a great spirit is somewhere watching down.”

Every time I read this novel, I remember that life is a beautiful mystery and the best thing we can do is to embrace and explore that mystery and simply trust. In love, in life, and in ourselves.

The Camino Letters: 26 Tasks on the Way to Finisterre is a memoir I read when it first came out in 2010 and then again more recently because of my plan to walk the Camino de Santiago next year. As I prepare, I find myself drawn not only to guidebooks but also to first person accounts of walking this ancient pilgrimage trail in Spain.

I hadn’t recalled much about the content of this book; only that I absolutely loved it and it moved me. Second time around, it did not disappoint. Right from the preface, author Julie Kirkpatrick, who is a Canadian lawyer as well as a writer, makes it plain that she didn’t really understand what she was getting herself into when she decided to walk the Camino. The only nod to preparation was spontaneously asking 26 friends to assign her a daily task for each day of her long walk.

The book is made up of the daily letters she wrote her friends about the outcome of each of the tasks they assigned her. Some of the tasks sounded simple (listen to the wind, be mellow, give something away) but there was nothing simple about what she experienced on the Camino path. As Kirkpatrick says: “The act of putting one foot in front of the other, day after day, with only my tasks to answer to, led me on an interior journey that I was not prepared for and was not expecting.”

The letters are a deep dive into the backstory of the author’s life, written with incredible generosity and heart. Her writing is raw and vulnerable and and she is honest about her own shortcomings and missteps. She peels back protective layers to write with great candor about some of the most painful events of her life: losing her mother at a young age, living with an autoimmune condition that can result in sudden blindness, and the stillbirth of a child.

As the reader, it’s beautiful to witness the revelations and insights that happen over the course of Kirkpatrick’s journey, as both the Camino and the writing work in concert to bring about healing. The result is a profound reading experience for which I’m very grateful.

This is a perfect segue to the last book on my list. Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives by the late Louise DeSalvo was gifted to me by my writing mentor, Pam Donoghue, during our work together in the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia’s Alistair MacLeod Mentorship Program.

Over the last twenty years, DeSalvo’s book has had a huge impact on me personally, as well as guiding me on my path to become a writing mentor. I have suggested this book to more clients than I can count. In a nutshell, this book is about how writing, as a complement to therapy, can heal the most thorny and persistent and messy wounds of our lives.

“Why, then, should we write? Because writing permits the construction of a cohesive, elaborate, thoughtful personal narrative in the way that simply speaking about our experiences doesn’t. Through writing, suffering can be transmuted into art. And writing permits us to use our writing as a form of public testimony in a way that the private act of therapy doesn’t.”

As someone who has always written to make sense of my life, I found that DeSalvo’s book deepened my understanding of what writing can do for us. I have taken her words to heart over the years, first in blog posts and most recently in my book Writing Your Way, where I share personal stories about the things that have held me back from both creating and living fully.

What I discovered as I wrote my book is exactly what DeSalvo stated. Through the act of writing about some of my most vulnerable experiences I began to feel my way toward a new understanding and a healing of old wounds. Once I published my book and it was being read by both strangers and friends, that sense of healing only deepened as my words began to help readers discover their own hidden truths.

I hope you can see the thread that ties these wonderful books together. All three have inspired me with their magical combination of heart and soul and with the light they have shone on growth and healing. I hope you seek them out and that they spark something within you.

Happy reading and happy writing!

May 26, 2023

“She is my daughter … no outsider shall ever come between us again” #ReadingLanternHill

My friend Kathy Cawsey has written a guest post for the Jane of Lantern Hill readalong that I’m co-hosting this month with Naomi of Consumed By Ink, and I’m very happy to share it with you on this last Friday in May.

When I asked Kathy for a short bio, she said that she “gets paid to read and talk about reading at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.” She’s the author of a book on Images of Language in Middle English Vernacular Writings, and her research includes Later Middle English Writing, such as Chaucer, Malory, Margery Kempe, the cycle dramas, and medieval romances, and modern medievalist fantasy, such as J.R.R. Tolkien and Guy Gavriel Kay. Her current project focuses on the complexities of sexualized violence in medieval texts. She says most of her essays are academic, though she’s switching into a more personal style for some, including a very moving essay about reading Old English laments during the COVID-19 pandemic. (You can read it here.)

In this guest post about L.M. Montgomery’s Jane of Lantern Hill, Kathy writes about Jane’s grandmother in relation to her own grandmother. Like Jane, Kathy grew up in Ontario. She was very close to her grandmother, until her grandmother’s death at the age of 97. Here’s a photo from the celebration of her grandmother’s 95th birthday:

Rereading as an adult a book you loved as a child can be eye-opening. As a kid I loved the Narnia series, and read and re-read them; different Narnia books became my favourite book at different ages. But as an adult I found them oddly empty. C.S. Lewis’s worldbuilding power is such that the books opened up landscapes and storyscapes in my imagination that were never actually on the page.

Like the Wardrobe, sometimes when you go back into a childhood favourite, you meet only coats and a plain brown wooden wall. The magic is there, but inaccessible.

Reading the Little House on the Prairie books to my daughter was an eye-opening experience in a different way. I could still enjoy them as an adult in a way I couldn’t enjoy the Narnia books, but I noticed completely different things. As a child, I of course loved Laura, but Pa—because he so clearly was Laura’s idol—was also one of the major figures of the book. I never paid much attention to Ma beyond wanting to taste her vanity cakes and laughing at the stick-figure story-duck she drew to keep the girls occupied while Pa was missing in the blizzard.

As an adult, I no longer laughed. Pa was missing in the blizzard. As an adult, I realized that Ma was desperately trying to keep the children from thinking about that fact. Even the vanity cakes took on a layer of meaning I hadn’t seen before: they were a cheap treat to make for a party with “town girls” who could afford more expensive things. Rereading, I envisioned Ma wracking her brains for nights before the party trying to think of affordable ways to make it special—to show those “town girls” that you didn’t need money to have a good life.

Now a mother myself, I noticed Ma, while Laura and Pa faded into the background. Ma being uprooted from the abundance of the farm in the Little House in the Big Woods to go scratch out a living on the prairie; Ma badly hurting her leg miles and weeks from a doctor (what if it hadn’t healed right? what if it had gone gangrenous?!); Ma holding the family together while Pa was constantly off somewhere. Laura—even as an adult—barely notices Ma. I found myself wondering what Ma thought, what she felt. Resentment? Resignation? Bitterness? Constant anxiety?

But Ma remained impenetrable. Apparently—as far as Laura and the reader were concerned—imperturbable.

(Kathy says, “I hadn’t noticed until just now how the image captures exactly what I’m talking about—Laura running around in the main part of the picture with Ma literally underneath her working away!”)

I don’t know if I read Jane of Lantern Hill as a child. I probably did, but I don’t remember it. I certainly didn’t reread it the way I read and reread the Anne books, or The Story Girl, or even Emily. So reading it for this readalong was a strangely doubled experience: I was reading it for the first time (as far as I could remember) as an adult, while simultaneously being aware of how I would have read it as a child.

And, as with the Little House books, I found myself noticing the adults far more than the central child. (Sarah lent me Alexander MacLeod’s essay “‘They were ours, ours! and now they are gone’: Re-reading J.M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy,” about a similar experience reading a beloved childhood book to his children, and being more interested in the adults in the story.)

For me, the grandmother is the one who is truly at the centre of Lantern Hill, even though the narrator and the plot follow Jane. She is a “still, cold, terrible” centre. Several readers in this readalong have mentioned the unreality of the PEI scenes, their almost-daydream quality, and I do think there could be a convincing reading of Lantern Hill that sees all the Island chapters as the imaginings of a girl stuck in an unloving, cold house in Toronto. No character in PEI—even the father, even Jane herself—is as vivid as the grandmother in Toronto.

Though maybe the grandmother was only vivid to me, because in my mind my own grandmother slips easily into that character. Jane’s grandmother is what my Grandma could have become, had she made different choices, had life treated her differently.

Grandma was a wonderful person—loving, fun, with a great sense of humour. I never doubted her love for me. So in many ways she was nothing like Jane’s grandmother. She liked children; I have great memories of numerous tea parties with her child-sized dish set.

But there was another side to Grandma. The tea parties were great fun, yes, but they were also where I learned manners and polite, adult conversation. No plastic for Grandma: the dishes were creamy porcelain, elegant and breakable. Most of the fun of tea parties was pretending to be elegant, “proper” ladies. As we aged, we were allowed to graduate from invisible tea to tiny cups of coke, from which we would delicately sip. No spilling, though!—Grandma was fussy. There was a wet washcloth hung off of the bottom rung of our chairs, to wipe all the stick off our hands afterwards. (I hated the way she would wipe down right between my fingers, where stick couldn’t possibly have been.)

Grandma valued manners. And grammar. She was “proper” in the way only someone from a poor background could be. She had “married up,” into the lawyer’s family of Fergus, Ontario—but she was proud, and fiercely independent. Like Jane’s grandmother, her husband died young, and she was left with two children to support. Rather than living off of the charity of her husband’s family, she went back to work at a time when most women stopped teaching after they had kids.

I sometimes wonder what Grandma would have been like if my grandfather had lived, and she had become a regular fifties housewife, using her piercing intelligence to choose clothes or plan dinner parties rather than teaching blind children mathematics. Or if he had been richer, and had left her a large house in Toronto, say. She might have become small, and bitter, and petty, like Jane’s grandmother. Grandma cared desperately about what people thought, and that caring was reflected in how she dressed, how she carried herself; she was far more elegant at age 97 than I have ever been. I remember her telling me that if I spent ten minutes each day pinching down in long strokes on my nose, it would become longer and not be so squished.

In her older years—and she lived a very long life—she went through bouts of depression. Jane’s grandmother reminded me most strongly of my Grandma of those years. Grandma had depended on my mother, the oldest child, since her husband died, and they had a very close relationship. Had my mother been different, she could well have turned out like Jane’s Mother—flighty and thoughtless. Mom’s quiet rebellion was refusing to care about clothes and parties.

During those years of depression, Grandma was like Jane’s grandmother, wanting to keep my Mom to herself. I vividly remember Grandma once describing my Dad—whom she loved very much—as the “man who stole my daughter from me.”

Dad was mad, of course, but he explained to me that it was the depression speaking. But I know a small part of Grandma truly believed that fantasy of her and my mother living together forever, even though it could never have happened: my parents met long after Mom had moved out and was living on her own.

So Jane’s grandmother, for me, was a vision of what my Grandma could have been, had she lived and chosen differently. Someone who cared about money and property, and proper-ty, propriety. Someone who resented anyone their beloved daughter loved. Someone who valued appearances and being “proper” more than the happiness of her family. Someone who disdained people who prioritized mere happiness over dignity, respectability, decorum.

Jane of Lantern Hill ends before Jane goes back to Toronto, so we never see the grandmother’s reaction to her daughter’s moving out and buying the “little stone house in Lakeside Gardens.” Almost certainly things would not have gone as smoothly as Jane envisions. Probably they would have moved back into 60 Gay as a family while they waited for the Lakeside Gardens house to be ready; probably the grandmother would have thought she was acting exquisitely politely to Jane’s father, while bitter, snide remarks slipped out against her will. Probably Jane’s father would have steadfastly ignored those remarks. Probably Jane’s mother would have quietly kept the peace and prevented anyone from saying anything truly unforgiveable. Probably after they moved, the family would have gone to 60 Gay every week for Sunday dinner, putting the golf game on the television so there would always be something to talk about or to fill awkward silences. Maybe the grandmother would have moved into Lakeside Gardens when she had glaucoma, and would have learned to twirl spaghetti with her arthritic fingers, never saying a word about her hatred of the dish—because that would be impolite.

Maybe Jane would realize, as an adult, that her grandmother really did love her in her own, rather warped, way, which is why she cared so deeply about what Jane wore, how she behaved, and what school she attended. Maybe Jane would bring her newborn child to visit his great-grandmother in hospice, and even though by that point most of the grandmother’s personality had been nibbled away by multiple strokes, she still would have jumped and fussed when the baby spit-up.

That is my daydream for Jane. An adult daydream of complex, hard joy, rather than simple easy happiness.

Better than childhood fancies of going through the wardrobe to PEI, because I know it can actually happen.

Thank you, Kathy!

If you missed my earlier posts about the novel, you can catch up here:

“Back in Bonn with Bethie, #ReadingLanternHill”

“The Idyllic Island (#ReadingLanternHill)”

From Naomi MacKinnon: “Announcing a Readalong of Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery: #ReadingLanternHill”

From Rebecca Foster: “Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery (1937) #ReadingLanternHill”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. If you’d like to subscribe and receive future posts by email, you can sign up on my website, www.sarahemsley.com. Thanks for reading!

May 19, 2023

One Beethoven

During this trip to Bonn, I’ve visited the house where Beethoven was born (Beethoven-Haus Bonn), his baptismal font (at St. Remigius Church), and the 1845 statue by Ernst Julius Hähnel in the Münsterplatz; I’ve read Lisa Tunbridge’s Beethoven: A Life in Nine Pieces and watched a fascinating documentary called “Beethoven’s Ninth: Symphony for the World” (filmed in Shanghai, Sao Paulo, Osaka, Kinshasa, Barcelona, and Bonn, and available on Netflix in Germany, but not, alas, in Canada); and I’ve enjoyed taking pictures of the many Beethovens who appear in shop windows, outside restaurants, and sometimes in the windows of private homes. Some of these are reproductions of the 700 statues created by Ottmar Hörl for his installation “Ludwig van Beethoven – Ode an die Freude [Ode to Joy],” in the Münsterplatz in 2019.

“Freedom, going further—this is the only goal in the world of art, as in all of grand creation.”

– Beethoven

St. Remigius Church

Beethoven-Haus Bonn (and the courtyard behind the house)

My favourite room in the museum gathers together several portraits of Beethoven, including the famous one by Joseph Stieler of Beethoven with the manuscript of the Missa solemnis, and screens that display quotations from Beethoven’s contemporaries about his appearance and personality: “very proud, non-descript, magnificent mind, rushing, ugly and red-faced with pock marks, grumpy.”

On May 6th, Coronation Day in the UK, I attended a wonderful concert by Pèter Köcsky at Beethoven’s house, and my brother-in-law reminded me of Beethoven’s famous words to Prince Karl Lichnowsky:

“Prince, what you are, you are by circumstance and birth; what I am, I am through myself. There are, and there always will be, thousands of princes; but there is only one Beethoven.”

(“Fürst, was Sie sind, sind Sie durch Zufall und Geburt, was ich bin, bin ich durch mich; Fürsten hat es und wird es noch Tausend geben; Beethoven gibt’s nur einen.” From a letter Beethoven wrote to the Prince in October 1806; translated in David Wyn Jones’s The Life of Beethoven, quoted by Tunbridge.)

When I attended a performance of Tom Allen’s splendid chamber musical “The Missing Pages” in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia at the end of April—the story of the only Canadian who met Beethoven—I borrowed my daughter’s “Ludwig Lives” t-shirt for the occasion. On this trip to Bonn, I decided to buy a t-shirt of my own.

Bonn University Botanic Gardens

I spent a few glorious days in Amsterdam earlier this week, and—as you might imagine—I took lots of photos. I’ll put some of those together for a future blog post. I’m very happy to be back in Bonn now with my sister and her family. My brother, Tom, and his daughter have just arrived from Nova Scotia, and yesterday we visited Burg Drachenfels, a ruined castle that was built in the 12th century, and Schloss Drachenburg, a neogothic castle built in 1882. In the castle, we found one of the Beethoven statues by Ottmar Hörl, along with a stained glass window featuring Beethoven.

Tom and Beethoven

The view from Drachenfels

“True art remains imperishable, and the true artist takes inward delight at great products of the mind.”

– Beethoven

While I was writing this blog post, my ten-year-old niece was playing with her sister, and also making up a song as she watched me write, singing about how I was typing—“typey, typey, typey, that’s what you do”—and reading, turning the pages, taking a sip of coffee. “I can see you over there, typing again … my job’s to sing about what you do.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. If you’d like to subscribe and receive future posts by email, you can sign up on my website, www.sarahemsley.com. Thanks for reading!

May 12, 2023

The Idyllic Island (#ReadingLanternHill)

At first, Jane doesn’t want to leave her mother to travel to Prince Edward Island—even though she dislikes living in Toronto—and she wishes the days wouldn’t fly by so quickly.

(If you missed the first post about L.M. Montgomery’s Jane of Lantern Hill, you can catch up here: “Back in Bonn with Bethie, #ReadingLanternHill.”)

As a very young child, Jane had once asked her mother if there was any way they could stop time, and her mother sighed, saying, “We can never stop time, darling.” Montgomery seems very aware of the passage of time in Jane of Lantern Hill, more than I’ve noticed in her other books. Once Jane gets to PEI, she loves it, and the idyllic life she finds there that first summer seems to go on forever. Then she has to endure nine months before she can return, and she ticks off the months one by one, and feasts on news from the Island.

Blackbush Island, PEI

Ferry to PEI

I love PEI with all my heart, but I have to say that I found some of the descriptions of the Island’s perfections a bit much. In Jane of Lantern Hill, it’s presented as a perfect world. It’s a place of delights, from the delectable food—“a box of doughnuts, three loaves of bread, a round pat of butter with a pattern of clover leaves on it, a jar of cream, a raisin pie and three dried codfish”—to the glorious landscape—“free hills and wide, open fields where you could run wherever you liked, none daring to make you afraid, spruce barrens and shadowy sand-dunes, instead of an iron fence and locked gates”—to the friendly and welcoming people. It’s a place where Jane “could do just as she wanted to without making excuses for anything.” Things happen so easily for her here! Unlike Anne Shirley, who after her arrival in PEI is always getting into “scrapes,” “Jane was very capable and could do almost anything she tried to do. … There was joy in her heart the clock round. Life here was one endless adventure.” Except it doesn’t sound like an adventure, not really, because it’s all so perfect.

My daughter took this photo at Dalvay Lake, PEI a couple of years ago

And it all happens quickly, too. Montgomery sounds to me impatient to make everything work out well for Jane. No one can stop time, but it’s as if she can’t slow down at all to dramatize any complications. Jane and her father set up house at Lantern Hill, and “By the end of a week Jane knew the geography and people of Lantern Hill and Lantern Corners perfectly.” Not only that, but she has a new “bosom friend,” Min. But since Min is only mentioned in passing, in the middle of a long paragraph about how well Jane settles in, we don’t get to see how the girls discover they’re kindred spirits.

While the secondary characters in Montgomery’s Anne or Emily novels are interesting as individuals, I found it hard to keep track of the assortment of characters who surround Jane and her father in their Island home, and I confess I sometimes ended up skimming passages. Jane may be able to “pick out Big Donald Martin’s farm and little Donald Martin’s farm,” but I can’t tell the difference. “Elmer and Min and Polly Garland and Shingle and Jane were all children of the same year and they all liked each other and snubbed each other and offended each other and stood up for each other against the older and younger fry. Jane gave up trying to believe she hadn’t always been friends with them.” I was left wondering why they liked each other, and how they snubbed or offended each other. There’s so much potential here—and I found I wanted more. She’s made friends fast, but they don’t seem like distinct characters to me, just names that appear in lists. “All Jane’s particular friends, old and young, came, even Mary Millicent…. Step-a-yard came and Timothy Salt and Min and Min’s ma and Ding-dong Bell and the Big Donalds and the Little Donalds and people from the Corners that Jane didn’t know knew her.”

I was relieved to learn that when Jane finds her father’s Distinguished Service Medal from the Great War, “breathless with pride over her discovery,” her father is dismissive and tells her to “throw it out.” Conflict at last!

When Jane is back in Toronto, desperate to return home to PEI again, we’re told “The Lantern Hill news was still absorbing,” but as a reader I didn’t feel absorbed in it, I guess because I didn’t feel invested in the characters there. More lists follow, full of news, none of it especially memorable. (I was reminded of the letters Anne Shirley writes in Anne of Windy Poplars, a novel I have always found excruciatingly dull.)

Even though I didn’t feel the same fascination with the news from home, I did feel a deep sympathy for Jane on her return to Lantern Hill, when she realizes “she had never been away at all. She had really been living here all along. It was her spirit’s home.” My heart breaks for her here, and for her creator, and for anyone who feels trapped in a place that isn’t their true home.

As I mentioned in my first post on this novel, Jane’s grandmother reminds me of Lady Catherine de Bourgh. I was glad to find that near the end of the novel, Jane confronts Mrs. Kennedy and demands, “What happened to the letter father wrote to mother long ago, asking her go to back to him, grandmother?” Like Elizabeth Bennet, who refuses to obey Lady Catherine, Jane speaks up for herself and for the truth. She extracts from her grandmother an admission that she burned the letter, and she states clearly that she knows her mother and father love each other still. I was cheering for her and at the same time appreciating the dramatic impact of her grandmother’s decisive reply—“They do not”—but then when the chapter ended abruptly, I was left wondering why Jane’s mother, who was present during this conversation, said nothing at all. Even if Robin isn’t as outspoken as her daughter, it still seems strange to me that she’d be completely silent during this fight between her daughter and her mother.

Maybe Montgomery was dealing with so much conflict in her own life that she didn’t feel able to include more of it in this novel.

I knew, obviously, that in choosing to reread Jane of Lantern Hill as an adult, I might find that I didn’t love it as much as I had when I was young. I wanted to love it, and I did, sometimes, but not all the way through. The story seemed to me sometimes like a draft that would benefit from further revisions. More details about the characters and conflicts between them, more dialogue in key scenes of confrontation, and a little less perfection in the descriptions of PEI.

In the end, Toronto is shown as a place of possibility, not just misery, as Jane envisions a happy life with her reunited parents in the “little stone house in Lakeside Gardens,” during the winter, and then summers at Lantern Hill in PEI. Toronto is a more complex place than it seemed in the first pages of the novel; I guess I wish PEI could be shown as a similarly complex place, rather than just as a perfect heaven.

(And yes, I recognize that I’m showing only idyllic aspects of the Island in these photos…. They’re all holiday photos, taken over the last few years, all of them before the Island was damaged by Hurricane Fiona last fall.)

My sister Bethie and I watched the 1989 Lantern Hill movie earlier this week, and we agreed that in this adaptation there’s a little too much of Wuthering Heights and Northanger Abbey, and not nearly enough PEI. There isn’t even a speck of red dirt on those country roads, or on the north shore cliffs, either.

I’d love to hear what you think of the Island and its inhabitants, and the happy ending Montgomery bestows on Jane and her parents, and on Jody, too. And/or any other aspect of the novel (or the movie) that you’d like to discuss.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. If you’d like to subscribe and receive future posts by email, you can sign up on my website, www.sarahemsley.com. Thanks for reading!