Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 17

December 2, 2022

Preparing to Celebrate Jane Austen’s 250th Birthday in 2025

Jane Austen’s 250th birthday is December 16, 2025, and I’m thinking about throwing a party sometime that year. Would you like to celebrate with me?

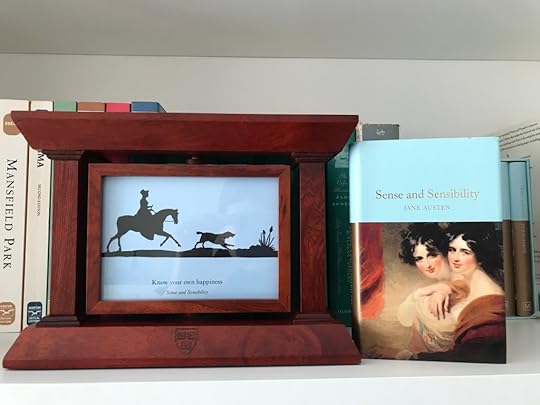

It’ll probably be similar to the online celebrations I hosted here in honour of the 200th anniversaries of Jane Austen’s novels Persuasion and Northanger Abbey, Emma, Mansfield Park, and Pride and Prejudice. I started these online celebrations in 2013 and thus had already missed out on the chance to celebrate Sense and Sensibility in 2011.

Many people are making plans to celebrate Jane Austen’s life and works in 2025—a couple of weeks ago, for example, I mentioned the upcoming exhibition at the Morgan Library, guest curated by Austen scholar Juliette Wells—and I’m looking forward to hearing more about the various events, exhibitions, and parties.

Maybe 2025 would be a good time to pay tribute to Sense and Sensibility, Austen’s first published novel. What do you think?

November 25, 2022

What to Read Next

Thanks so much for all the wonderful book recommendations you sent in response to last week’s post! Creating lists like this and sharing them with other readers is in itself a comfort in an uncertain world. Even though I can’t read them all right away, the books are there, waiting, and that can be a source of joy. And when I do read them, they’ll remind me of the people who recommended them, which enriches the whole experience.

Happy belated Thanksgiving to those of you who were celebrating yesterday. I enjoyed reading this Thanksgiving-themed column by Charles M. Blow, “Thankful for Libraries.” He writes about the first library he ever visited, in elementary school: “I remember thinking as a small child that I was in a cavern of tomes written by people across time and around the globe, that each volume probably contained thousands of ideas, and I wondered how could I get all of those ideas into my mind.” Years later, when he was writing his first book, he worked “in the main branch of New York City’s public library not because I needed to do research—the book was a memoir—but because the space itself seemed most aligned with the task of writing. It was like going to church to pray.”

I too am thankful for libraries. Here’s the Music Library at the Schumann House in Bonn, Germany, which I visited last month. Robert Schumann lived in this house between 1854 and 1856, the last two years of his life.

If you’re wondering what to read next, here are a few ideas:

Naomi recommends Birth Road, by Michelle Wamboldt; We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies, by Tsering Langzom Lama; and Decoding Dot Grey, by Nicola Davison.

Peter recommends The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, by Eve Jurczyk, and is looking forward to reading the newly published letters of John Le Carré.

Sandra recommends Stalin’s Daughter, by Rosemary Sullivan, and The Genius of Birds, by Jennifer Ackerman.

Somewhere Towards the End, by Diana Athill: Cheryl says, “It’s a wonderful meditation on aging, books, gardening, death, and many other important topics.”

Still Life, by Sarah Winman: Marianne says it’s “a wonderful work of historical fiction, especially for those who love art and Italy, particularly Florence. It’s an uplifting exploration of love, family, and friendship in all their many guises. And it references E.M. Forster and Room with a View—a happy coincidence!”

I saw Marianne earlier this week and she lent me her copy of Still Life.

The Classic Slave Narratives, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: Collins says, “All the personal stories were hard; Harriet Jacobs’ story, perhaps the hardest.”

The Splendid and the Vile, by Erik Larson: Gerri says it’s “a non-fiction account of Winston Churchill, his family and various secretaries as well as Lord Beaverbrook for one year during WWI. It is so well written that I had difficulty putting it down. As the title indicates, nothing every minute is gloom and doom even during a war.”

The Shell Seekers and Coming Home, by Rosamunde Pilcher: Cheryl Ann says Coming Home is “a richly detailed historical novel set between 1935 and 1945 in Cornwall, London, and Ceylon” and she highly recommends both novels.

Victoria recommends To Kill a Mockingbird and Go Set a Watchman, by Harper Lee; Moby Dick, by Herman Melville; The Lost Daughter, by Elena Ferrante; The Garden of Monsters, by Lorenza Pieri; The Clash of Civilizations Over an Elevator in Piazza Vittorio, by Amara Lakhous; The Uncommon Reader, by Alan Bennett; Wonderworks, by Angus Fletcher; and Margaret Renkl’s opinion piece in The New York Times called “The Joy of Finding People Who Love the Same Books You Do.”

Thank you again!

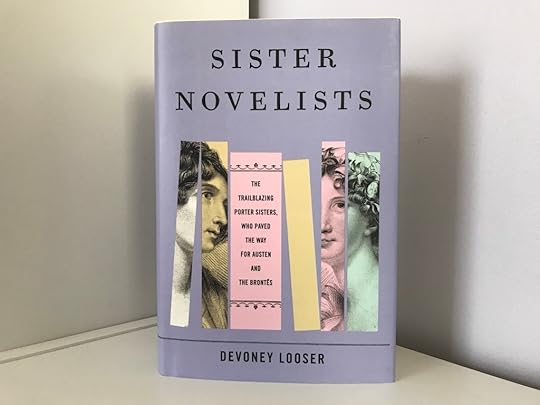

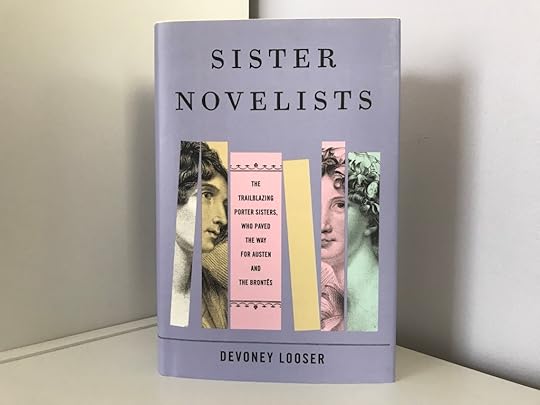

I’m now about halfway through Devoney Looser’s stunning new book, Sister Novelists, which I mentioned in last week’s post, and I’m finding the lives of the Porter sisters and their groundbreaking work in historical fiction fascinating. At one point, when Jane Porter’s work was finding success and Maria’s was not, Maria wrote to her sister that she was considering giving up writing: “I will therefore magnanimously relinquish the Quill and taking up a good darning needle, strive to mend my errors…. If some honest man will marry me, then will I give up the muses; but if not, authorship and old maidism shall go together. Happiness or Fame, that is the alternative.” As Devoney says, “The world wasn’t set up to allow women conventional domestic happiness and unconventional public fame. The sisters knew few women writers who’d succeeded without having been born into money or a title.”

Over the past week, I’ve also been thinking more about books I read earlier this year. I don’t do “best books of the year” lists, but if I did, here’s what I’d put at the top: Animal Person, by Alexander MacLeod, a powerful collection of short stories published in April 2022. Line by line, the whole book is brilliant.

These stories are about family, intimacy, rivalries, secrets, death—about everything, really, and in fact the word everything echoes throughout the book: “The way I see it: everything linked and all of it tied directly into the movement of the planets and our little blue-green orbit around the sun” (from “What exactly do you think you’re looking at?”); “I guess it’s like a movie—maybe everything is like a movie—but this isn’t us just watching a movie” (from “Everything Underneath”); “Where I lived, in a single-story bungalow one over and one down from the Klassens, life was not like this, and everything we did felt like a compromise” (from “The Ninth Concession”); “Can’t you just picture her? Everything’s already set up, and now she’s sitting there watching the clock, waiting for us to arrive.” That last quotation is from “Once Removed,” which was published in The New Yorker in February.

I went looking for a photo of a chandelier and I don’t have anything that resembles the “ugly medium-sized chandelier with brass accents” that features so prominently in “Once Removed,” so instead here’s something entirely different, a spectacular light fixture that I saw in the summer, at the Museum of the City of New York.

I discovered I’ve actually taken quite a few photos of light fixtures recently. Was I inspired to do so after reading “Once Removed”? Maybe. Probably. And/or it could be because I’ve been travelling quite a bit in the last few months, for the first time in years, and I’ve been noticing new and interesting things everywhere I go. It could also be because since the early days of the pandemic, my sister Bethie and I have been talking about looking for light, both real and metaphorical. She’s reminded me that on my next trip to Germany, we’ll need to be prepared to turn down the heat and turn off lights, because of the energy crisis.

Light fixtures in New York City and Cochem, Germany:

Maybe on some future trip, I’ll find an ugly chandelier with brass accents.

The story at the centre of Animal Person, “The Entertainer,” looks at a piano recital from the perspective of a young piano student named Darcy who is absolutely certain his performance will be a disaster, his teacher, Roxy, and the husband of a woman, Gladys Ferguson, whose ability to communicate through words has slipped away, though her memory for music has remained. From Darcy’s feeling that “sometimes it feels like the music itself, the actual sheets, are making fun of me,” to Roxy’s sympathetic understanding of Darcy’s lonely predicament—“It’s just better, so much better, when you are not up there, up here, alone”— to the last words spoken by Gladys Ferguson’s husband, this story broke my heart.

The first story in the collection, “Lagomorph,” is about ordinary chaos in the life of one family and their extraordinarily long-lived pet rabbit, Gunther, and it’s been a favourite of mine since it was first published in Granta in 2017. I like the way the kids in the family work out “a pretty funny matador routine” with Gunther, shaking a dish towel and shouting “Toro! Toro! Toro!” I like the way “the minivan was always running in the driveway, its rolling side door gaping for the quickest possible turnaround, like an army helicopter.” I like the eldest daughter’s response to the news that her parents are separating: “We just want you to be happy,” she tells them, and the narrator (her father) says “the line stuck in my ear because I’d always thought it was the kind of thing parents were supposed to tell their kids, not the other way around.” At the end, the narrator sees himself reflected “at the red centre” of Gunther’s eye, and he can almost see his family’s shared history “held inside the mind of the oldest rabbit that has ever lived.”

“Lagomorph” won an O. Henry Prize in 2019. In 2020, it was published as a hand-crafted letterpress book by Gaspereau Press, and this edition was named the winner of the 2021 Nova Scotia Masterworks Arts Award. You can read the story on the Granta website, but of course I encourage you to get a copy of Animal Person so you can read all the stories in this splendid collection.

Do you make “top books of the year” lists? Do you have a favourite book published in 2022?

I’ll close with a photo I took last Saturday, in an attempt to capture the late afternoon light. This is the view from Point Pleasant Park in Halifax, looking out toward McNabs Island (on the left) and York Redoubt (on the right).

November 18, 2022

Reading is My Anchor

Hello, long-lost friends! I’ve missed the conversations we’ve had over the years, here in this corner of the internet. It’s been a while since I last wrote a blog post, and my goodness, the world has changed a lot since then. My love of reading has stayed steadfast, and I’d be very interested to hear your recommendations. What have you been reading in recent weeks—or years? What books do you turn to in times of uncertainty?

Here are a few highlights from among the books I’ve read recently.

Central Park

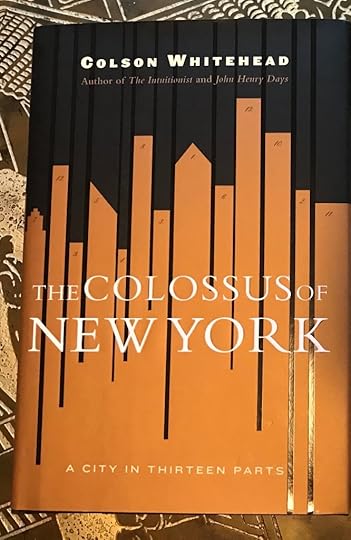

One of the books I enjoyed most in the summer, during a weekend trip to New York City with my daughter, was Colson Whitehead’s The Colossus of New York: A City in Thirteen Parts. I had read the brilliant first essay, “The Way We Live Now: 11-11-01; Lost and Found,” several times, and the ending always moves me to tears: “The twin towers still stand because we saw them, moved in and out of their long shadows, were lucky enough to know them for a time. They are a part of the city we carry around….”

But I hadn’t yet read the whole book, and now, long after I finished reading it, lines from the last essay are still echoing in my mind: “When you talk about this trip, and you will, because it was quite a journey and you witnessed many things, there were ups and downs, sudden reversals of fortune and last-minute escapes, it was really something, you will see your friends nod in recognition. They will say, That reminds me of, and they will say, I know exactly what you mean.”

At the very end, Whitehead talks about flying out of New York and the way “the city explodes into view with all its miles and spires and inscrutable hustle,” and the feeling that even as “you try to comprehend this sight you realize that you were never really there at all.”

My daughter and I visited several bookstores (no surprise there), including Books Are Magic in Brooklyn, which we both loved. We’re already planning our next trip.

In mid-October, Juliette Wells, Professor of Literary Studies in the Department of Visual, Literary, and Material Culture at Goucher College in Baltimore, Maryland, came to visit Nova Scotia as one of the Jane Austen Society of North America’s Traveling Lecturers. She spoke in the English Department at Dalhousie University and at the Halifax Central Library. In preparation for her visit, I re-read her book Reading Austen in America, a persuasive account of the way readers on this side of the Atlantic contributed to the international fame of a novelist who is often thought of as quintessentially English.

My favourite chapter is the one on Christian, Countess of Dalhousie, one of Austen’s early readers, whose husband founded Dalhousie University. To give just one example of Lady Dalhousie’s engagement with Austen’s novels: in a diary entry in 1818, she recorded that she read Persuasion while on board ship, sailing from Halifax to Mahone Bay.

Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia, at twilight. In the bottom photo, you can just make out the spires of the famous three churches.

Juliette writes that though the hero of the novel, Captain Frederick Wentworth, “was a naval officer, not an army man like Lord Dalhousie, Austen’s positive portrayal of the British military post-Waterloo would certainly have resonated with the countess.” Lady Dalhousie might also have appreciated Austen’s portrait of the intrepid Mrs. Croft, who has joined her husband the Admiral on his naval journeys back and forth across the Atlantic and to the East Indies, and who claims that “Women may be as comfortable on board, as in the best house in England.” Mrs. Croft also protests, famously, that “We none of us expect to be in smooth water all our days” (Persuasion, Volume 1, Chapter 8). Lady Dalhousie had a similar spirit of adventure: “In the most daring act recorded of her,” Juliette says, “she was the first person, male or female, to walk the length of a just-finished suspension bridge between Ottawa and Hull, over the Rideau Canal,” in 1827.

Juliette’s new book, A New Jane Austen: How Americans Brought Us the World’s Greatest Novelist, will be published next year by Bloomsbury, and I’m keen to read it. In the lecture she gave at Dalhousie, she spoke about early Austen scholars, including Oscar Fay Adams, Austen’s first critical biographer and critical editor. She shared this lovely image of him alongside a photo of Cecil Vyse, as played by Daniel Day-Lewis in the 1985 adaptation of E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View. A perfect match, right?

As 2025 approaches, Juliette is serving as guest curator for a special exhibition at The Morgan Library that will mark the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. (Another great reason to plan a trip to New York….)

I love the film adaptation of A Room with a View and had just watched it earlier in October with my sister and brother-in-law when I was visiting them in Bonn, Germany. My sister does a particularly good imitation of Mr. Beebe’s response to the “Miss Honeychurch. Piano. Beethoven.” scene: “If Miss Honeychurch ever takes to live as she plays it will be very exciting, both for us and for her.”

I borrowed my sister’s copy of Beethoven: His Life and Music, by Jeremy Siepmann, after she and I had visited the house in Bonn where Beethoven was born, and I liked it so much that I ordered my own copy after I got home. Maybe I’ll write more about Beethoven and Bonn in a future blog post; for now I’ll just quote Siepmann: “Among the many things which make Beethoven’s music unique is its extraordinary capacity to inspire courage. … In some ultimately mysterious way, he makes us feel, through his example, that we can confront reality without fear.”

(I accidentally left my glasses case on the plane when I flew from Halifax to Frankfurt, and was happy to find a case featuring Joseph Karl Stieler’s portrait of Beethoven in the gift shop at Beethoven’s House.)

Not long after Juliette’s visit, I attended two other fabulous and memorable literary events in Halifax. The first was the launch of Renée Hartleib’s book Writing Your Way: A 40-Day Path of Self-Discovery.

Renée invites readers to make time for quiet reflection and writing, promising that even just a few minutes a day of listening to “the inner, truest version of you” can be enough to change our lives. While reading Writing Your Way, I was often reminded of one of my favourite quotations from Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, in which the heroine, Fanny Price, says “We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be.” Renée suggests that writing can help us find our way to a “better guide” within—she says “Some might call it your soul, your spirit, or your essence”—whether we’re seeking answers about creating art, making changes in our lives, working to make the world a better place, or all of the above.

The second event, Booktoberfest, was organized by the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia and held in our beloved Halifax Central Library. Forty-four authors participated in a celebration of books they had released during the first two years of the pandemic, when in-person events were, for the most part, cancelled. Several authors read from their work, and all were available to sign copies of their books.

I came home from Booktoberfest with two new treasures (I could easily have bought many more), including Lauren Soloy’s picture book Etty Darwin and the Four Pebble Problem. I love the imagined conversation between Etty and her famous scientist father about science and the imagination, during their walks on The Sandwalk, the “thinking path” he created near their house.

I also bought Stephens Gerard Malone’s new novel The History of Rain, about a veteran of the Great War who finds consolation in work as a landscape gardener, and I had a chance to chat with Stephens about our shared love of historical fiction.

“I say give the earth your rage, young man, and she’ll give you flowers.”

At the moment, I’m switching back and forth between reading The History of Rain and a new biography by Devoney Looser called Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës.

Thanks for reading to the end of this long post, and please do send book recommendations!

I’ll end with a photo of the anchor at the entrance to HMCS Stadacona in Halifax, along with a photo of nearby Admiralty House (now the Naval Museum of Halifax). Jane Austen’s brother Francis lived in Admiralty House when he was in Halifax in the summers of 1845, 1846, and 1847 as Commander-in-Chief of the North American and West Indies Station.

July 19, 2019

Down to the Sea

“… the next thing to be done was unquestionably to walk directly down to the sea.”

– Jane Austen’s Persuasion (1818), Volume 1, Chapter 11

I’m rereading Persuasion and I thought I’d share a few photos I took when I walked down to the sea the other day. This is not Lyme Regis (obviously), but Herring Cove Provincial Park, in Nova Scotia.

I’ve missed taking pictures and writing for this blog. At the moment, I don’t have any plans to host big celebrations like the blog series I hosted last year in honour of the 200th anniversary of Persuasion and Northanger Abbey, but it’s nice to be back.

What are you all reading these days? I’m always looking for new recommendations, even though I always have a long list of books I want to read. After Persuasion, I’m planning to start Amy Jones’s new novel, Every Little Piece of Me. My friend Naomi wrote about the novel on her blog last week: “I loved this book,” she says. “With humour and insight, Amy Jones goes deeper and darker with Every Little Piece of Me, exploring the dark side of media and social media, women’s issues, loss and grief, and the power of human connection.”

I like that the novel opens with a family on the verge of moving from New York to Nova Scotia to open a bed and breakfast. Here’s the response of one of the daughters to the announcement about the move:

“Dad. Papa. We know where Nova Scotia is.” She did, vaguely, insofar as she knew that it wasn’t New York, or L.A., or even New Hampshire—was it actually, possibly, could it be, in Canada?

Other recent additions to my list include Washington Black, by Esi Edugyan (which my friend Marianne just started reading), and The Ghost Road, by Charis Cotter (recommended by my daughter). Further suggestions welcome!

October 30, 2018

Elinor and Marianne

I loved finding Jane Austen’s Elinor Dashwood in Emma Straub’s novel Modern Lovers, just as I loved finding Marianne Dashwood in Jeanne Birdsall’s The Penderwicks on Gardam Street (in which Jane Penderwick says “the mystifying Marianne who hated flannel will long linger in my memory”).

Straub’s heroine Elizabeth writes a song called “Mistress of Myself”:

Everyone else at Oberlin was all hot and bothered about Foucault and Barthes, but she was far more interested in Jane Austen. She was reading Sense and Sensibility for pleasure, and that’s where she saw it—on one of the very last pages, when Elinor Dashwood was trying to prepare herself for a visit from Edward Ferrars, with whom she was deeply in love but who she believed had forsaken her. “I will be calm; I will be mistress of myself,” Elinor thought.

Elizabeth understood it completely: the desire to be in control, the need to speak the words aloud. No one in Saint Paul, Minnesota had ever been truly her own mistress. … Elizabeth swiveled the chair around so that it was facing the window, and opened up her notebook. The song was finished fifteen minutes later….

Sense and Sensibility also makes an appearance in Gail Honeyman’s novel Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine:

It’s another one of my favorites: top five, certainly. I love the story of Elinor and Marianne. It all ends happily, which is highly unrealistic, but, I must admit, narratively satisfying, and I understand why Ms. Austen adhered to the convention. Interestingly, despite my wide-ranging literary tastes, I haven’t come across many heroines called Eleanor, in any of the variant spellings. Perhaps that’s why the name was chosen for me.

In The Penderwicks on Gardam Street, Jane Penderwick seems to have an even stronger passion for dead leaves than Marianne Dashwood does, as she not only admires them, but buries herself beneath them:

Abandoning herself to the relief of tears, she pushed the leaves this way, then that way, then another, trying to build a big enough pile to crawl under. She was crying too hard to manage even that, though, so finally she simply lay down and pulled a few leaves over her face, and cried and cried until there were no more tears, but still she lay there, thinking that maybe she would stay forever, moldering along with the worms and the leaves, and at least she would help the lawn grow.

From Sense and Sensibility:

“Dear, dear Norland,” said Elinor, “probably looks much as it always does at this time of the year. The woods and walks thickly covered with dead leaves.”

“Oh,” cried Marianne, “with what transporting sensation have I formerly seen them fall! How have I delighted, as I walked, to see them driven in showers about me by the wind! What feelings have they, the season, the air altogether inspired! Now there is no one to regard them. They are seen only as a nuisance, swept hastily off, and driven as much as possible from the sight.”

“It is not every one,” said Elinor, “who has your passion for dead leaves.”

“No; my feelings are not often shared, not often understood. But sometimes they are.”

[image error] [image error] [image error]

I decided to share these quotations today because it’s the 207th anniversary of the publication of Sense and Sensibility. I’ll leave you with a few more photos of dead leaves, and then I’m going to take a break from blogging and social media for a while to focus on other writing projects—see you sometime in 2019!

These photos below are from a walk I took with a dear friend—whose name, coincidentally, is Marianne—in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, last week.[image error]

September 28, 2018

“Quiet Observation” in Persuasion

“We have much to learn from the patient practice of quiet observation in Jane Austen’s Persuasion,” writes Natasha Duquette. I’m sharing her guest post on the novel today in honour of the first day of the Jane Austen Society of North America AGM, which is entitled “Persuasion: 200 Years of Constancy and Hope.”

Natasha Duquette is Professor and Chair of English at Tyndale University College. She’s the author of Veiled Intent: Dissenting Women’s Aesthetic Approach to Biblical Interpretation (2016) and the co-editor, with Elisabeth Lenckos, of Jane Austen and the Arts: Elegance, Propriety, Harmony (2013). Her current project is a 30-Day Journey with Jane Austen, which she describes as “a small volume consisting of curated passages from Austen’s work accompanied by brief reflections” (forthcoming from Fortress Press in 2019). She serves on the Board of Directors for JASNA and she’s a member of the churches subcommittee, which oversees JASNA support of parishes in the UK, such as St. Nicholas in Chawton and Winchester Cathedral. She lives in Toronto, Canada, with a pug, a papillon, and her husband Fred.

Four years ago, when I hosted a blog series in honour of Mansfield Park, Natasha wrote about “Fanny Price’s Prayers,” and it’s a pleasure to welcome her back with this guest post on Anne Elliot and “quiet observation.”

Slowing down, quieting one’s mind, and becoming more conscious of one’s physical senses and surroundings can yield unexpected dividends, spiritually and creatively. As a novelist, Jane Austen was a careful observer of both human character and natural landscapes. She must have been a masterful practitioner of silent attentiveness. In her novel Persuasion Austen deploys the phrase “quiet observation” (Volume 1, Chapter 5) to define this posture. The heroine of Persuasion, Anne Elliot, exemplifies this intellectual faculty, in contrast to her sister Mary’s in-laws, Mr. and Mrs. Musgrove, who are “unobservant and incurious” (Volume 1, Chapter 6). Anne, on the other hand, has the wonder, curiosity, and receptivity of a writer or a scientist. The narrator explicitly emphasizes her “attention for the scientific” while she is listening to music at a concert, for example (Volume 2, Chapter 8). Anne is at times painfully aware of “her silent, pensive self” (Volume 2, Chapter 1). This self-awareness is a gift, however. In our modern world of virtual realities, alluring distractions, and at times frantic busyness, we have much to learn from the patient practice of quiet observation in Jane Austen’s Persuasion.

When I began thinking about this piece, I took my Penguin edition of Persuasion with me on a trip to Ward’s Island, off the Northern shoreline of Lake Ontario, just a short ferry ride away from downtown Toronto. I was trying to detach from the incessant press of urban competitiveness in order to create space to receive Austen’s words. As I was reading her most naval narrative alongside open water, I glanced up from the page and beheld a nineteenth-century schooner (or close replica of one) sailing along.

[image error]

Both photos © Natasha Duquette

At first, I could not believe my eyes, but there it was, the perfect visual accompaniment to the text of Austen’s novel. After a few moments, the sound of cannon fire boomed in the distance from the schooner. With the scents and tastes of a swim in Lake Ontario fresh in my memory, feet cradled in the warm sand, eyes delighted by the sailing ship, and ears awakened via the sound of cannon, I was grateful I had taken some time for quiet observation.

In Austen’s novel Persuasion, Anne Elliot carefully contemplates both natural landscapes and human beings. At the turning point of the novel, she is in Lyme, with “its sweet retired bay, backed by dark cliffs, where fragments of low rock among the sands make it the happiest spot for watching the flow of the tide, for sitting in unwearied contemplation” (Volume 1, Chapter 11). When Anne visits the seaside with Henrietta Musgrove, the two young women “gloried in the sea; sympathized in the delight of the fresh-feeling breeze—and were silent” (Volume 1, Chapter 12). Paradoxically, this contemplative locale is where Anne Elliot breaks from her silent stasis by springing into action, when Henrietta’s sister Louisa Musgrove takes a near fatal fall. In this emergency, it is the men who are frozen and fainting in fear while Anne shouts out decisive and quickly obeyed commands. Austen shows us how Anne’s quiet observation leads to clear judgment, and her steady contemplation undergirds confident action.

This is the case in Anne’s contemplation of human nature as well. Early on in the narrative, we find Anne “contemplated” the Musgrove sisters “as some of the happiest creatures of her acquaintance” (Volume 1, Chapter 5). In her initial period of quietly observing Captain Wentworth, after their eight-year separation, she contemplates evidence of his still “warm and amiable heart” with a mix of pleasure and pain (Volume 1, Chapter 10). She later attentively observes the grieving Captain Benwick’s psychological state and prescribes textual remedies for his healing. Anne’s impoverished friend Mrs. Smith likewise receives her undivided attention. Interestingly, women of keen perception surround the vulnerable Mrs. Smith, as her nurse Rooke is also “a shrewd, intelligent, sensible woman” with “a fund of good sense and observation” (Volume 2, Chapter 5). The collectively quiet yet shrewd study of Mr. Elliot’s character by a small team of women—Anne, Mrs. Smith, and nurse Rooke—leads to the exposure of his true character. Detectives are also people of quiet observation.

The novel’s moments of astute perception build one upon another until they reach a crescendo with Anne’s sighting of Captain Wentworth in Bath. The narrator powerfully but simply states: “the very first time Anne walked out, she saw him” (Volume 2, Chapter 7). Then, four paragraphs later, an amplified statement of the same fact occurs: “Anne, as she sat near the window, descried, most decidedly and distinctly, Captain Wentworth” (Volume 2, Chapter 7). The alliterative “d”s of this sentence create a staccato effect conveying Anne’s intense emotion. She is a woman whose “feelings for the tender” accompany her powers of empirical observation (Volume 2, Chapter 8). She sees the reality of Captain Wentworth’s being clearly as she looks through the transparent glass of a shop window. In her chapter written for the essay collection Jane Austen and the Arts (2013), Melora Vandersluis notes how Austen contrasts the vanity of those fixated on reflective glass mirrors, like Sir Walter Elliot, with the truth perceived by those who look through the glass of a window. Anne’s descrying of Wentworth’s distinct form is a perfect example of the latter.

There are dangers in underestimating and underusing the powers of quiet observation. By neglecting to regularly exercise this mental and spiritual capacity, we may miss the daily wonders of our external environments, the subtle signs of unethical characters impinging on us, or the lived realities of someone we love. Though you are most likely reading this blog post on an electronic device, consider turning it off for even just a few minutes. Following Anne Elliot’s example, take some time to contemplate the actual creatures or places close to you at this moment.

Quotations are from the Penguin edition of Persuasion, edited and with an introduction by Gillian Beer (1998).

August 31, 2018

Summer

Here are some of the pictures I took this summer in Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.

On the ferry to PEI at the end of June, on my way to the L.M. Montgomery Institute conference in Charlottetown and the unveiling of the Project Bookmark Canada plaque honouring Montgomery’s poem “The Gable Window” in Cavendish:

[image error]

Wood Islands Lighthouse, PEI

[image error]

Charlottetown sky

[image error]

“The Gable Window” Bookmark, Cavendish, PEI

[image error]

PEI lupines (which always make me think of Barbara Cooney’s book Miss Rumphius: “You must do something to make the world more beautiful.”)

Back in Nova Scotia:

[image error]

In the garden at the Cole Harbour Heritage Farm, Nova Scotia

[image error]

Hiking at Graves Island Provincial Park, Nova Scotia

[image error]

The view from Graves Island

[image error]

The Halifax Public Gardens

[image error]

Government House, Halifax, Nova Scotia

A few photos from a run at Point Pleasant Park in Halifax:

After I read Charis Cotter’s novel The Painting (Tundra, 2017), part of which takes place at a lighthouse in Newfoundland, I wanted to visit a lighthouse, so I chose one that’s close to home—Peggy’s Cove. From the novel:

I sat on my bed and looked at the painting of Newfoundland on my wall.

It was just as beautiful as ever. The road was so inviting—as if Maisie was saying come in, come here, come into this world and walk along the road to the lighthouse, and you will find something you have always wanted. I realized that that was what it always said to me. It was the promise of a different world, a world of heartbreaking beauty where everything was right and seabirds flew against the sky and the wind blew patterns in the tall grass.

But it wasn’t really that wonderful world. Now I knew how unhappy Claire had been there.

This section is from the perspective of Annie, one of the two heroines. I loved the epigraphs from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, and Claire’s passion for the Bookmobile that visits the remote community where she lives: “I don’t know what I would have done without that Bookmobile…. I never felt better than when I walked home from school with my eight new books weighing down my knapsack, with all that new reading ahead of me.” Claire’s favourite books include Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden and novels by L.M. Montgomery (“I wiped away my tears and reached for Emily of New Moon and Anne of Green Gables. I was just about an orphan now, so I might as well read books about orphans.”)

[image error]

Peggy’s Cove

Walking along the St. John River, on a short trip to Fredericton, New Brunswick:

The last few photos are from a day trip with my daughter to River John, Nova Scotia, to visit one of our favourite bookstores, Mabel Murple’s Book Shoppe & Dreamery:

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

July 29, 2018

Eight Years!

Here are eight of my favourite blog posts, to mark the eighth anniversary of my blog:

Jane Austen’s “Darling Child” Meets the World: on the publication of Pride and Prejudice in 1813.

Why is Mr. Darcy So Attractive? (in the novel, not the movies).

Mansfield Park is a Tragedy, Not a Comedy: on the tragic action of Austen’s Mansfield Park.

Austens in Bermuda and Nova Scotia: photos of places Jane Austen’s brothers Charles and Francis Austen and their families visited during their time on the North American Station of the British Royal Navy.

[image error]

Admiralty House, where Francis Austen and his family stayed when they were in Halifax, Nova Scotia in the 1840s

What Edith Wharton Tells Us About the Way We Live Now: on The Custom of the Country.

Spring in Rainbow Valley: on L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valley, with photos from a trip to Prince Edward Island.

[image error]

“The Lake of Shining Waters.”

[image error]

Malpeque, PEI

“She knew that a hard struggle was before her”: Emily’s Quest: “After this I’m just going to write what I want to,” says L.M. Montgomery’s heroine Emily Starr.

[image error]

PEI National Park, Cavendish

The Republic of Love Bookmark and the Carol Shields Memorial Labyrinth: “Think instead of the stories you like to read, or better yet, the story you would like to read but can’t find.” – Carol Shields

[image error]

The Carol Shields Memorial Labyrinth, Winnipeg, Manitoba

I can’t begin to choose favourites from among the many posts other writers have contributed to the three blog series I’ve hosted, so I’ll include all of them:

An Invitation to Mansfield Park: Guest posts in honour of the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (2014).

Emma in the Snow: Guest posts in honour of the 200th anniversary of Austen’s Emma (2015-16).

Youth and Experience: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion: the blog series that began last fall and ended a few weeks ago. Guest posts on the two novels that were published together after Austen’s death in 1817.

Many thanks to everyone who’s read and commented and contributed guest posts over the past eight years!

June 29, 2018

Such a Letter

Deborah Yaffe read Pride and Prejudice when she was ten and she’s been a passionate Jane Austen fan ever since. She joined the Jane Austen Society of North America when she was sixteen and she reports that she has an impressive collection of Austen-themed coffee mugs, bookmarks, tote bags, and DVDs. She spent thirteen years as a newspaper reporter in New Jersey and California, and her award-winning first book, Other People’s Children: The Battle for Equality in New Jersey’s Schools, tells the story of the state’s efforts to provide equal educational opportunities to rich and poor schoolchildren.

Deborah holds degrees from Yale University and Oxford University, and she lives in Central New Jersey with her husband, her two children, and her Jane Austen Action Figure. You can find her online at her blog, www.deborahyaffe.com, on Twitter (@DeborahYaffe), and on the Facebook page for her book Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom.

When I hosted a celebration of Mansfield Park in 2014, Deborah wrote a guest post called “The Fatal Mistake,” and for my blog series “Emma in the Snow,” she wrote about “Emma the Imaginist.” I’m very happy that she’s written a guest post on Captain Wentworth’s famous letter for “Youth and Experience: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion .” Welcome back, Deborah!

“I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone for ever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own, than when you almost broke it eight years and a half ago. Dare not say that man forgets sooner than woman, that his love has an earlier death. I have loved none but you. Unjust I may have been, weak and resentful I have been, but never inconstant. You alone have brought me to Bath. For you alone I think and plan.—Have you not seen this? Can you fail to have understood my wishes?—I had not waited even these ten days, could I have read your feelings, as I think you must have penetrated mine. I can hardly write. I am every instant hearing something which overpowers me. You sink your voice, but I can distinguish the tones of that voice, when they would be lost on others.—Too good, too excellent creature! You do us justice indeed. You do believe that there is true attachment and constancy among men. Believe it to be most fervent, most undeviating in

F.W.

“I must go, uncertain of my fate; but I shall return hither, or follow your party, as soon as possible. A word, a look will be enough to decide whether I enter your father’s house this evening, or never.”

(Persuasion, Volume 2, Chapter 11)

“How was the truth to reach him?” Anne Elliot wonders towards the end of Persuasion, as she realizes that her true love, Captain Wentworth, is jealous of her relationship with her cousin, Mr. Elliot. “How, in all the peculiar disadvantages of their respective situations, would he ever learn her real sentiments?” (Volume 2, Chapter 8)

Anne’s romantic dilemma—how to bridge the distance between herself and the man she loves—mirrors Jane Austen’s artistic problem in the closing chapters of her last completed novel. Her hero and heroine are not family, like Emma Woodhouse and Mr. Knightley; they are not even friends, like Catherine Morland and Henry Tilney. Eight years after their broken engagement, they are at best acquaintances, part of the same neighborhood social circle. In the course of the novel, they have barely spoken to each other, and never in private. How will these two ever communicate freely enough to clear up the misunderstandings that divide them?

We know Austen struggled with this plot problem, since her first attempt at solving it has survived, in the so-called “cancelled chapters” of Persuasion, the only extant rough draft of any part of her finished books. The cancelled chapters—which cast Admiral and Mrs. Croft as heavy-handed matchmakers, the dei ex machina who maneuver Anne and Wentworth into a decisive conversation—provide a clumsy and implausible resolution; no wonder Austen herself found the work “tame and flat,” as her nephew tells us in his Memoir, and went to bed nursing that depressed feeling of failure so familiar to all writers (J.E. Austen-Leigh, A Memoir of Jane Austen, ed. Kathryn Sutherland. Oxford: Oxford University Press [2002]).

But the alternative that came to her upon waking was nothing short of brilliant, and the scene she eventually wrote, which culminates in Anne’s reading of Captain Wentworth’s letter, is one of her greatest. It’s a clever and elegant solution to her plot problem and a tour de force of technique: In one of the greatest love scenes in all of English literature, the two protagonists never exchange a word, communicating entirely through stolen glances, overheard conversations, and, finally, an impassioned written declaration.

Wentworth’s letter—so beloved among Janeites that it is known simply as The Letter—is unusual in Austen’s work: deeply, satisfyingly romantic in a way that her happy endings seldom are. (Compare Edward Ferrars’ proposal to Elinor Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility: “In what manner he expressed himself, and how he was received, need not be particularly told” [Volume 3, Chapter 13]). While swooning, however, we should not overlook the consummate artistry with which Austen creates her effects, at the levels of plot, character, language, and theme.

First, note how perfectly Austen’s solution to her plot problem fits the relationship she has established between her two protagonists. Although they seldom speak—their first conversation of any substance occurs in the Octagon Room at Bath, three-quarters of the way through the novel—Anne and Wentworth are exquisitely tuned in to each other’s frequencies, picking up what less perceptive observers miss: He notices her exhaustion on the walk back from Winthrop, she correctly reads his lack of real romantic interest in the Musgrove sisters. From the beginning, their communication is non-verbal, or pre-verbal; how appropriate that it should remain so almost until the end—until one of them “can listen no longer in silence.”

Once that silence is broken, notice how true the letter’s style is to the personality of the man who writes it. Like so many of Austen’s most sympathetic male characters, Wentworth is decisive and direct; he does not ramble or dither. With its choppy rhythms (of the 23 sentences in the letter, 12 are less than 10 words long, and only three run to more than 20) and its simple, declarative vocabulary (only 14 of its 260 words contain more than two syllables), the letter is eminently believable as the work of just such a person operating under the influence of intense emotion. As he pours out the feelings he has bottled up for years, Wentworth doesn’t have the time or inclination for carefully balanced clauses and flowery turns of phrase.

And yet this passage, supposedly written on the fly by a man with no time for reflection, is structured with great care. Austen pulls off the near-miraculous trick of building a convincing illusion of spontaneous emotional expression on a foundation of conscious, deliberate artistic choices that recapitulate and deepen the novel’s themes.

Because we know we’re reading a declaration of love, it’s easy on a first reading, or even a fourth or fifth, to miss how dark the first part of the letter is. Wentworth begins with a painful, even violent metaphor (“You pierce my soul”). In the lines that follow, he speaks of agony and heartbreak. He condemns himself as weak, resentful, and possibly unjust. Repeatedly, he evokes the alternative way this story might end: the chance that he is too late, that Anne’s feelings may have changed, that love can die. As he writes, he in effect re-experiences the anguish of their parting and of the self-doubt and estrangement that followed.

If the first part of the letter is all about their past, the next section will leave that sad history behind. And what are the words that, on the page, provide the bridge from the remembrance of past pain to the possibility of new happiness? They are “never inconstant”—words that also name the fact about the Anne-Wentworth relationship that makes such bridging possible.

In the second part of the letter, we are no longer trapped in the painful past; we have moved into the present—their recent meetings in Bath—and almost immediately into real time, as Wentworth reports his sensations and reactions (“I am every instant hearing something which overpowers me”) as he listens to Anne’s conversation with Captain Harville. Indeed, Wentworth is listening so carefully that he even echoes one of Anne’s phrases from that conversation—“true attachment and constancy.” He comes into perfect unison with her on the very words that explain why such unison between them remains possible.

Just as the body of the letter moves from past to present, so in his postscript, Wentworth projects his relationship with Anne into the (near) future: “this evening,” when he will—or won’t—cross the threshold of “[her] father’s house,” literally and symbolically bridging the distance between Anne’s past life as a daughter and her future life as a wife. In essence, then, Wentworth’s letter retells in miniature the history of his relationship with Anne, moving from past grief to present understanding to future union, across the bridge of constant attachment.

Impassioned and moving, the letter deserves its reputation for romantic sublimity, but it is not a simple outpouring of endearments. It is something more mature and nuanced. It bears witness to life’s contingency, acknowledges past failure, and embodies a commitment to trying again anyway. In the letter, and in the conversations that follow, Anne and Wentworth do not deny the pain they have caused each other; they accept it, move through it, and integrate it into the happier future they plan together. Through Wentworth’s letter—an elegant plot device and an effective tool of character development, couched in carefully chosen language and perfectly calculated to put a lump in the reader’s throat—Austen returns us to Persuasion’s central themes: that love is fragile, but also enduring; that grief and pain are real, but so is hope.

Quotations are from the Penguin Classics editions of Persuasion and Sense and Sensibility, included in Jane Austen: The Complete Novels, with an introduction by Karen Joy Fowler (2006).

[image error]

“Placed it before Anne.” Illustration by C.E. Brock (from Mollands.net)

This is the thirty-third and last post in the series—thank you very much to all the contributors, and to everyone who read and shared and commented on their work. If you missed any of these guest posts and you’d like to catch up, you can find all the contributions listed here. Happy 200th anniversary to Northanger Abbey and Persuasion!

June 27, 2018

Thinking About Austen’s Writing of Persuasion

Many years ago, when I taught my very first English literature class and I put Pride and Prejudice on the syllabus, I was absolutely delighted to discover a collection of essays called Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. This wonderful book was exactly what I needed—I had just completed an MA thesis on medieval poetry and I didn’t know Austen’s novels very well. I learned a great deal from the book about how to introduce my students to Jane Austen’s world and to the pleasures of looking at the novel from a variety of different perspectives. (That year I also learned, partly through the experience of teaching Pride and Prejudice, that I wanted to apply to PhD programs so I could study Austen’s work in more detail.)

One of the essays in the collection was particularly helpful in showing how the way Elizabeth Bennet interprets the view from Pemberley can help us to understand the novel itself: as she moves from room to room and looks out the windows, it seems as if the objects she sees are “taking different positions”—but of course it’s Elizabeth who is “taking different positions,” which demonstrates “one of the novel’s central insights: that perceptions from fixed vantage points must be corrected by movement through space, as first impressions must be corrected by movement through time.” You can imagine what a pleasure it was when I met the editor of the book, and the author of that essay, Marcia McClintock Folsom, a couple of years later at my first JASNA AGM, in Colorado Springs, and how happy I have been to continue to learn from Marcia’s essays and AGM presentations, and from conversations with her about Austen’s novels.

Marcia McClintock Folsom is Professor Emeritus of Literature at Wheelock College. She’s the editor of Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma as well as Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and with co-editor John Wiltshire, Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park, and Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Persuasion (forthcoming). Her essay “Emma: Knowing Her Mind” was published in Persuasions 38 (2017), and her analysis of “Power in Mansfield Park: Austen’s Study of Domination and Resistance” appeared in Persuasions 34 (2013). I’m very happy to introduce her contribution to “Youth and Experience: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion.”

Readers have a lot of specific history about Jane Austen’s writing of Persuasion. Thanks to the note written by her sister Cassandra on the dates of composition of the novels, we know that Jane Austen began Persuasion on August 8th, 1815 and completed it on August 6th, 1816 (Minor Works, ed. Chapman, Volume 6). Readers also have the surprising added luck of the existence of a 32-page manuscript of two last chapters that Austen decided not to use as the novel’s conclusion. This manuscript, written on both sides of 16 small pieces of paper, is the only manuscript known to exist of any part of any of her published novels. That extraordinary discovery deepens our knowledge of Austen’s process and of the difficulties she experienced in writing the end of Persuasion.

August 8th, 1815, was just seven weeks after the battle of Waterloo, which ended the more than two decades of war between Britain and France. Napoleon, the French commander-in-chief, had actually resigned more than a year earlier than that battle, on April 5th, 1814, and had been sent to exile on the Isle of Elba near Italy. In March of 1815, he had escaped, and gathering an army of supporters, he had resumed the war. What followed was later called the “One Hundred Days” of new fighting, until Napoleon was decisively defeated at Waterloo, by combined British and Prussian troops. As Brian Southam points out in Jane Austen and the Navy, the day that Austen began writing Persuasion, August 8th, 1815, was the day the British newspapers announced that “Bonaparte has sailed,” exiled again, this time to St. Helena, a much more distant island in the South Atlantic, 1,200 miles off the coast of southern Africa. The time span of the novel, from “the summer of 1814” to the middle of February 1815, corresponds to the last half of Napoleon’s first exile, and the novel’s happy ending occurs before what all of Austen’s first readers would have known, that this lull in the war ended in March, fighting resumed on land, and required an immense military effort finally to defeat the French army, on June 18th, 1815, at Waterloo. Southam argues that one of Austen’s purposes in this novel was to celebrate the navy, since it had declined in prestige after the truce with the American navy in December of 1815, and since the Waterloo victory had been achieved by the army, not the navy.

The novel Austen began on the date of the beginning of Napoleon’s second exile, August 8th, 1815, is the most precisely dated of any of her novels, beginning, as she wrote, “at this present time” in “the summer of 1814” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). That summer during Napoleon’s first exile was when naval officers (still on half-pay) came home, rejoining British society, and looking for houses to rent and wives to marry. Modern editions of Persuasion often contain chronologies of the novel, usually beginning, as the novel does, with Sir Walter Elliot’s birthdate, mentioning marriages, other birthdates, and events that occur before the novel’s present, and then slowing down to trace the action month by month, week by week, and even day by day, as Austen places the novel’s present events in clear sequence through the late summer, fall and early winter of 1814 in Volume I, and December, January, and early February of 1815 in Volume II.

Austen’s own locations in the year that she was writing Persuasion are traced by John Halperin (The Life of Jane Austen). She was at Chawton in August when she began writing it, and then in early October, she moved with her brother Henry to London in order to negotiate with John Murray about the publication of Emma. She stayed longer than she had expected because Henry became seriously ill, and Jane stayed on to take care of him. At the end of October, she wrote to Cassandra that she alternated between nursing Henry and “working and writing” in a back room. By this time her family was growing worried about her health, too. Henry gradually improved, and he was well enough for Jane to return to Chawton near the end of December. There she stayed, hosting frequent family visitors in April, May, and June, still working on the novel, but taking a trip with Cassandra in May to the spa at Cheltenham to try the supposedly medicinal waters in hopes of curing whatever was the matter with her. Among the visitors to Chawton that summer was Jane’s eighteen-year-old nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, who later wrote the “Memoir” of his aunt, which tells a story of her writing the first and second versions of novel’s ending during July and August of 1816.

The manuscript of the so-called cancelled chapters of Persuasion offers more details about the dates of Austen’s writing. The first manuscript page, marked “Chap. 10,” has the date “July 8.” The manuscript of “Chapter 11,” ends with the word “FINIS” and the date of “July 18. – 1816.” This date is exactly one year before Jane Austen died. The many cross-outs and emendations, especially in the second chapter, suggest Austen’s struggle in the ten days she spent writing these chapters, as does an earlier “FINIS” she apparently wrote on July 16th. Her revision completed, Austen-Leigh recorded that “her performance did not satisfy her. She thought it tame and flat, and was desirous of producing something better. This weighed upon her mind, the more so probably on account of the weak state of her health; so that one night she retired to rest in very low spirits . . . The next morning she awoke to more cheerful views and brighter inspirations; the sense of power revived; and imagination resumed its course” (A Memoir of Jane Austen). These dates mean that Austen wrote a new Chapter X, and a new Chapter XI with the brilliant scene at the White Hart Inn, and revised and recopied her old Chapter 11, which became the new Chapter XII, in just nineteen days.

Modern editions of the novel frequently include a transcript of the so-called cancelled chapters, sometimes with a photograph of page 1 as a sample to demonstrate the problems of deciphering Austen’s handwriting and her corrections. The two chapters contain a somewhat confusing narrative, presenting a meeting of Anne and Wentworth in the Bath apartment of Crofts, where Wentworth has been set up by Admiral Croft to ask Anne if it’s true that she will marry Mr. Elliot, and if so, the Crofts will leave Kellynch so Anne and Elliot can live there. The scene is painfully awkward for both Anne and Wentworth, and Anne, who is seated, can only reply hesitatingly, and the lovers’ understanding is achieved “in a silent, but very powerful Dialogue.”

The manuscript pages of these two chapters reveal a writer resolutely striving to figure out how to end the novel, and clearly frustrated with her efforts. Scholars, starting with R. W. Chapman, and including Arthur M. Axelrad, have studied the agonizingly corrected handwritten pages found in Cassandra’s desk. Most brilliantly, Jocelyn Harris, in her meticulous reconstruction of Austen’s struggles in writing Chapter 10 and Chapter 11 of the manuscript, sorts out hundreds of choices of diction, sequencing in sentences, as well as the implied writing process and probable intention about motives in Austen’s revision of those two chapters, and the creation of the new Chapters X, XI, and XII of the novel as it was published on December 20, 1817 (A Revolution Almost Beyond Expression, 2007). Harris devotes all of her Chapter 2, “The Reviser at Work,” to an analysis of “MS Chapter 10 to Chapters X-XI (1818),” and all of her Chapter 3 to “At the White Hart: MS Chapter 11 to Chapter XII (1818).” (As Austen did, Harris uses Arabic numbers for the manuscript chapters, and Roman numerals for the published 1818 chapters.)

Setting Virginia Woolf’s comments on Austen’s writing at the beginning of her study of these remarkable pages, Harris notes that Woolf looked with a “writer’s eye” on Austen’s early fragment, “The Watsons,” and found what Austen’s finished writing rarely betrays: “pages of preliminary drudgery” that Jane Austen must have “forced her pen to go through” to change a first draft into a polished work. In studying these astonishingly hard-to-read manuscript pages, Harris actually figures out what Woolf predicted, the “suppressions and insertions and artful devices” by which Austen tried to revise her own writing. As Harris vividly documents in her book: “Jane Austen is her own best and most ruthless critic when she reworks Chapter 10 of her manuscript into Chapters X-XI of the version published in 1818.” Noting Henry James’ grudging praise of Austen’s “light felicity,” and her (to him) apparently effortless and unconscious way of writing, Harris responds vigorously: “if James could have known how hard Jane Austen worked over her manuscript, he might have acknowledged a fellow professional. The revised manuscript of Persuasion reveals no warbling thrush, no wool-gatherer, but an extraordinarily self-critical, self-conscious, and meticulous writer and rewriter.”

Harris’s book magnificently uncovers the hidden meanings of Austen’s subtle, painstaking, multiple revisions of words, sentences, and sequences in the manuscript chapters, and then her drastic rejection and cutting of all that work. Bringing a much enlarged cast to Chapter X, Austen then creates in Chapter XI the infinitely more successful scene of the lovers coming together at the White Hart Inn. Reversing their positions in the cancelled chapter, Anne is standing with Captain Harville and Wentworth is seated. Anne here speaks at length, with tact and kindness to Harville, as she ardently describes the power of a woman’s passion, even “when existence or when hope is gone.” Wentworth’s letter in response to what he partially overhears is the most passionate declaration of love in any Austen novel.

As James Edward Austen-Leigh wrote about those chapters, “Perhaps it may be thought that she has seldom written anything more brilliant.” More extravagantly, Austen’s early 20th century critic Reginald Farrer wrote in 1917, the bicentennial of Austen’s death: “that culminating little heartbreaking scene between Harville and Anne (quite apart from the amazing technical skill of its contrivance) towers to such poignancy of beauty that it takes rank . . . as one of the very sacred things of literature the one dares not trust oneself to read aloud” (Littlewood, Volume 2). Without indulging in such rapture, many readers would say—and I would agree with them—that the last three chapters of Persuasion really are among the most brilliant pages Austen ever wrote. Studying Austen’s writing process, as Harris unfolds it in her book, enables readers to fathom even more completely the “amazing technical skill” of the final chapters of Jane Austen’s last completed novel.

Quotations are from the Cambridge edition of Persuasion, edited by Janet Todd and Antje Blank (2006).

Thirty-second in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit “Youth and Experience.” Coming soon: Deborah Yaffe’s guest post on Captain Wentworth’s letter. I can’t quite believe the series is almost over…. Thank you to everyone who’s been following along!