Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 16

February 24, 2023

Reading L.M. Montgomery Together

Would you like to read one (or two) of L.M. Montgomery’s novels with my friend Naomi and me? As I mentioned last Friday in the introduction to the guest post Naomi wrote for my blog, she and I met several years ago through an Anne of Green Gables readalong. A couple of years later, she hosted a readalong for Montgomery’s three “Emily” novels, and not long after that, we co-hosted a readalong for The Blue Castle.

We’ve been talking about reading another Montgomery novel together in the spring. Maybe Jane of Lantern Hill or Kilmeny of the Orchard. Or Pat of Silver Bush and Mistress Pat. If you’d like to join us, please let us know. Which novel(s) would you vote for?

I was sure I had a copy of Kilmeny of the Orchard, but I can’t find it. I know I read it when I was ten or eleven, back when I was completely obsessed with the world of Montgomery’s novels. I do, however, have this copy of “Una of the Garden,” a story Montgomery published in 1908-1909 and later transformed into Kilmeny of the Orchard.

Sometimes I think of this blog as a kind of scrapbook, inspired by the many scrapbooks Montgomery kept, in which she collected poems, stories, and book reviews, along with mementos such as ribbons, concert programs, pressed flowers, and so on.

In that spirit, then, I’ll add to my “scrapbook” some photos of spring flowers, given to me by my sister, who has been taking pictures of crocuses in Bonn, Germany, and my daughter, who was in Washington, DC last weekend.

If you’d like to read more about Montgomery’s scrapbooks, I recommend Carolyn Strom Collins’s article “Cutting and Pasting: What L.M. Montgomery’s Island Scrapbooks Reveal About Her Reading,” in the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies. I heard Carolyn present this paper at the L.M. Montgomery International Conference “L.M. Montgomery and Reading” in June of 2018 at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Elizabeth Rollins Epperly, founder of the L.M. Montgomery Institute at UPEI, curated a virtual exhibition that includes scrapbook pages: “Picturing a Canadian Life: L.M. Montgomery’s Personal Scrapbooks and Book Covers.”

February 17, 2023

Reading Close to Home

It’s a pleasure to introduce this guest post by my friend Naomi MacKinnon, whom I met online several years ago through an Anne of Green Gables readalong hosted by Lindsey Reeder. Naomi lives in Truro, Nova Scotia, about an hour’s drive from where I live, in Halifax. Since that first meeting online, we’ve seen each other in person many times, often at meetings of our local Project Bookmark Reading Circle, where we discuss fiction and poetry with the goal of identifying and recommending short passages set in specific places that could be marked with a Bookmark plaque. (If you’re interested, you can read more about our Reading Circle on the Project Bookmark website.)

Given our shared interests, Naomi and I weren’t surprised when we happened to run into each other at Anne of Green Gables – The Ballet, performed by Canada’s Ballet Jörgen in Halifax in 2019. Naomi attended with her daughters and her mother-in-law, and I was there with my daughter and my mother—and it was a delightful surprise to discover that Naomi’s mother-in-law and my mother have known each other for years. (Yes, it often seems that all of Nova Scotia is one small town….)

In the fall, when I was writing about the way my love of reading has served as an anchor during these last few years of challenges and uncertainty, I decided to ask some of my friends to write guest posts in which they talk about books they’ve read recently and want to recommend to others. Naomi’s is the first in this new series. When I asked her for a bio, she wrote that she’s “the mom of three human kids and five furry ones.” She added, “I have always lived in Nova Scotia, with the exception of the four years I spent in Sackville, NB, studying Biology at Mount Allison University. I love to read, walk, and eat cookies.”

I’m always keen to find out what Naomi’s discussing on her fabulous blog, Consumed By Ink, where she writes about Canadian books, especially those set in Atlantic Canada. Recent posts have featured Ducks, by Kate Beaton (which Barack Obama named as one his favourite books of 2022, and which Mattea Roach of Jeopardy! fame will be defending on Canada Reads this year); Emily Urquhart’s collection of essays on fairy tales and folklore, Ordinary Wonder Tales; and Steven Laffoley’s “irreverent histories” of food and drink in Nova Scotia.

Please help me give a warm welcome to Naomi! Here’s her guest post on “Reading Close to Home.”

When Sarah invited me to write a guest post for her blog I was delighted. I always love the opportunity to talk about good books.

As followers of my blog know, I love reading literature close to home—and, for me, that means Atlantic Canada. I enjoy reading about familiar settings. It makes me feel as though I know the characters intimately, that I might bump into them on the street someday. Or on a ferry, or at the beach, or in a bookstore. I could ask Mrs. Ward how her son is making out. Or I could ask Dot if they’ve gotten any new cats in at the animal shelter. I could go to the piano recital at the seniors’ home up the street and whisper into my friend’s ear about how unprepared Darcy was for his recital this year and be relieved it wasn’t my own child. I could say hello to Herring and Gerry while I’m down at the wharf buying fresh lobster.

Let’s start with one of Nova Scotia’s best short story writers, Alexander MacLeod, and his newest collection Animal Person. This is a book that Sarah has written about, too, saying, “Line by line, the whole book is brilliant.” Every sentence has been considered carefully to create well-crafted stories. When I think of this collection, I think of two sisters spread-eagled, face-down in the water, all you can hear is the breath through their snorkels. I think of a man using a stranger’s toothbrush then placing it back into the suitcase. I think of young Darcy at his piano recital, worrying about his performance as he sits listening to the others. And I think of a man and his rabbit and their unlikely companionship.

The other short story collection I want to recommend is The Love Olympics by Claire Wilkshire of St. John’s, Newfoundland. This collection is so relatable—it made me laugh and nod my head with recognition. With a strong focus on women, the book is full of memorable characters who weave their way in and out of these stories. I especially liked “The Dinner” in which four women gather together in the evening: women who are tired and looking forward to a much-needed break away from their families; women who are coping with the unpredictable nature of middle-aged hormones; women who have remained friends and supported each other through all their years of motherhood and marriage.

It’s more unusual to come across a good book about a friendship among a group of men. Jim McEwen’s Fearnoch might be stretching the boundaries of what some might consider Atlantic Canadian, but I am claiming it as ours. (McEwen is from a small town outside of Ottawa, which is also where his novel is set, but he graduated from St. John’s Memorial University Master of Creative Writing program and his book is published by St. John’s Breakwater Books.) Fearnoch focuses on three men who grew up together as friends, but many years later wonder if they’re still able to call themselves that. They’re grown now with partners, children, jobs, health issues. This book explores the nature of friendship and how it grows and changes and supports and disappoints and falls short and overcomes. I thought it was beautiful.

Set in Prince Edward Island where the author is from, Some Hellish, by Nicholas Herring, is another novel I read this year about male friendship—in this case between two men who may not even think of themselves as friends. They spend a lot of time together as lobstermen, but I don’t think they realize how important this time together has become for them. A hard book to read in many ways—as the title indicates—but there’s some humour to lighten things up, and I dare you not to get attached to the characters despite their tendency to make all the wrong choices.

There’s a younger male friendship in The Wards, by Terry Doyle. Although not at the heart of the novel, the friendship helps us to see the family members from an outsider’s perspective. The Wards—who live in St. John’s, NL—are an ordinary family with ordinary challenges, but the characters’ voices bring this book to life—characters you get to know so well that “you’re never surprised by their actions, even when their actions surprise you.” The kind of characters you’ll miss when the story is over.

In a similar vein, The Remembering, by Susan Sinnott, is a story about a mother and her three grown daughters (who also live in St. John’s, and who have possibly passed The Wards on the street or in the frozen foods section of the grocery store). It’s told from the perspective of the family members, with some humour and a lot of compassion. When one of the sisters is assaulted, we see how the situation is handled by the others, and how the incident influences their lives over the course of many years, into the next generation.

Set in the Halifax area, Decoding Dot Grey, by Nicola Davison, is a story about a family that has dwindled from three down to two, and Dot is a girl who is learning to cope with the loss of a parent. I adored this book. I loved Dot and her dad. I loved the animals with their unique personalities. The animals provide some humour and light moments in a book about grief. A tender story with a lot of heart, gentle humour, and some fun word-play. The world needs more books like this.

I love a good setting. A setting you can picture, even if you have never been there. But even better—for me—is one that I already know and love. Bird Shadows, by Jennie Morrow, takes place close to my hometown of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. Mavillette—where most of the book is set—is my favourite beach. It felt like we could run for miles on that beach. But the most delightful thing is that I was just as taken with the story as I was with the setting. The book explores themes of faith, family, and feminism, and does it well.

Mavillette Beach

Cape Forchu, the Yarmouth light

Bird Shadows takes place where I grew up, but Birth Road, by Michelle Wamboldt, takes place where I live now, in Truro. Although the story happens in the 1930s and 40s, the town is still recognizable and it’s fun to compare the accompanying map with what the town looks like now. I liked the familiar setting, and I also liked the fact that the story is a page-turner. At the beginning you learn that Helen is about to give birth, then the story takes you back to her childhood when her father was drunk all the time, her mother was stern, and her only friend was hiding something. Birth Road was inspired by the author’s grandmother.

The library in Truro, which in the 1930s and 40s was the Normal College.

Lastly, the book that made me laugh the most, Fishnets & Fantasies, by Jane Doucet (a Halifax-based author), is a delight from beginning to end. What would people think if someone opened a sex shop in a small, UNESCO World Heritage Site like Lunenburg, NS? Do yourself a favour and find out. It might even make you want to open one yourself!

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

The best thing about all of these books is the love the authors clearly have for their stories and characters. It fills my heart and sends me straight to my next reading journey in the hopes that it will be just as rewarding.

Happy Reading!

February 10, 2023

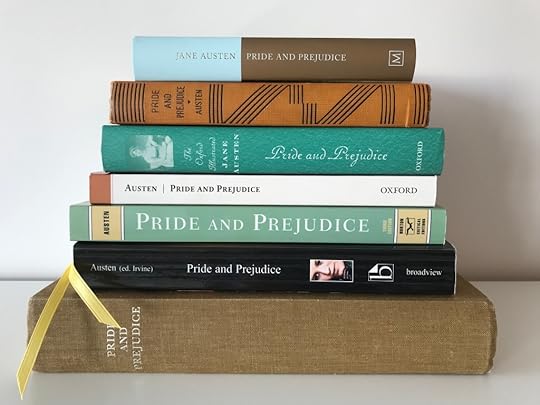

Inspired by Pride and Prejudice

What are your favourite Pride and Prejudice-inspired books? With Valentine’s Day coming up, since this novel is one of the great love stories, I thought I’d share a short list of some of my favourite P&P-inspired books. And of course I’d be glad to hear your recommendations.

The first one that comes to mind for me is Bridget Jones’s Diary, which I read, and loved, on a trip to London in the summer of 1997. I also loved Death Comes to Pemberley (2011), by P.D. James, though I remember thinking it seemed, at least in places, more Dickensian than Austenian. I’m a fan of the Cozy Classics board book version of Pride and Prejudice (2012), created by Jack and Holman Wang, and I’ve given it as a present to friends and relatives with newborns more times than I can count. I love the illustrations in Lizzy Bennet’s Diary (2013), written and illustrated by Marcia Williams, and in Goodnight Mr. Darcy (2014), by Kate Coombs, illustrated by Alli Arnold.

I enjoyed recognizing some elements of character and plot from Pride and Prejudice in Uzma Jalaluddin’s Ayesha at Last (2018), and I admire the way she created new twists and turns in her novel in a way that kept me guessing right up until the last chapters. I won’t give away the plot twists here, but I can say it’s easy to spot Lady Catherine as an inspiration for Farzana, the mother of the Darcy-inspired character: Farzana tells the heroine, Ayesha, that when her son Khalid “spoke about the teacher who was helping him plan the conference, I knew it was time for him to get married. Before he was duped by a pathetic spinster pretending to be more than she was.” Mr. Collins makes an appearance as “a life coach for wrestlers” who thinks of himself as “a doctor of the heart” and offers “motivational mantras” in times of tension. And there are echoes of Mrs. Bennet’s obsession with “the clothes, the wedding clothes!” in the words of Samira Aunty: “We had so much fun picking out her wedding lengha. It cost five thousand dollars and is being shipped from Pakistan direct!” I’m really looking forward to reading Jalaluddin’s new novel, Much Ado About Nada, which will be published in June.

Some of the other Pride and Prejudice-inspired novels I’ve enjoyed include Definitely Not Mr. Darcy (2011) and Undressing Mr. Darcy (2013), both by Karen Doornebos; Longbourn (2013), by Jo Baker; Pride (2018), by Ibi Zoboi; The Clergyman’s Wife (2019), by Molly Greeley; and Unmarriageable (2020), by Soniah Kamal.

I know there are many more—a quick search on Goodreads tells me there are at least 520 books inspired by Pride and Prejudice. What titles would you recommend?

P.S. I thought I’d share some early spring flowers with you. My sister Bethie took the pictures of snowdrops and flowering quince in Bonn earlier this week. The witch hazel was a present from my friends Hugh and Sheila Kindred, who came to my house for tea yesterday. This little bouquet is a nice spot of colour on a gloomy, snowy, slushy day in Halifax.

January 28, 2023

Living in Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice was published 210 years ago today, by Thomas Egerton, and Jane Austen earned £110 by selling the copyright. She had written to her friend Martha Lloyd in November of 1812 that “P. & P. is sold.—Egerton gives £110 for it.—I would rather have had £150, but we could not both be pleased, & I am not at all surprised that he should not chuse to hazard, so much.”

The day after the novel was published, Jane wrote, famously, to her sister Cassandra to say she had received her copy: “I want to tell you that I have got my own darling Child from London.” While preparing her first novel, Sense and Sensibility, for publication in 1811, she had used a similar metaphor: “No indeed, I am never too busy to think of S&S,” she wrote to Cassandra. “I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her sucking child.”

I’m sure I’ve said more than once on this blog that Pride and Prejudice is not only my favourite Austen novel, but my favourite novel of all time. Even though my affection for Persuasion increases every time I reread it, Pride and Prejudice is still my favourite, with Persuasion a close second. My sister Bethie and I have been talking about why we love Pride and Prejudice so much. Among the many reasons is the fact that the language of Jane Austen’s characters has become part of our everyday life. It’s as if we’re living in the novel. I don’t mean we’re imagining that the pattern of our lives follows the same plot. It’s that we often think in and with Austen’s sentences and we quote her words, sometimes seriously, sometimes as a joke.

We do this with Persuasion and other Austen novels, and with fiction and poetry by other writers (and with film adaptations). I sometimes insist, with Mary Musgrove, that “my sore throats, you know, are always worse than anybody’s,” or, with Fanny Price, that “We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be,” and I wrote recently about Bethie’s excellent imitation of Mr. Beebe from A Room with a View : “If Miss Honeychurch ever takes to live as she plays it will be very exciting, both for us and for her.”

But the words of Pride and Prejudice come up in conversation more often. I expect that’s partly because so many members of our extended family have seen the 1995 A&E mini-series several times, but I think it’s also because of “the playfulness & Epigrammatism of the general stile”—to borrow the words Jane used in a letter to Cassandra, a few days after Pride and Prejudice was published.

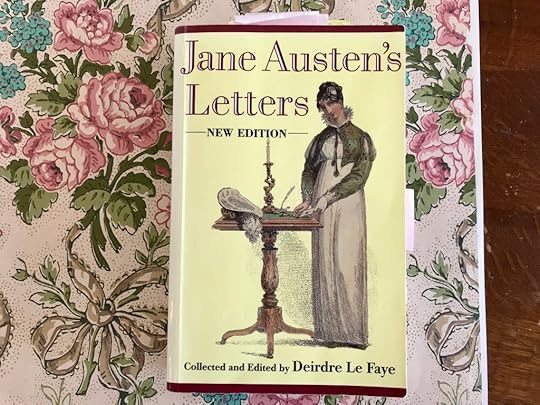

This edition of Jane Austen’s letters was a present from my late friend Janet. She and I visited the Jane Austen Centre in Bath more than twenty years ago, and since we both wanted to own the Letters, we bought copies for each other from the gift shop.

If you’re a fan of Pride and Prejudice, as Bethie and I are, do you find yourself thinking and speaking in Jane Austen’s sentences? If you do, I’d love to hear about the lines that resonate for you.

Here are some of the sentences on my list:

“You have no compassion on my poor nerves.”

“We dine with four and twenty families.”

“Do you prefer reading to cards?”

“I am not a great reader, and I have pleasure in many things.”

“I cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these.”

“Let the other young ladies have time to exhibit.”

“Happiness in marriage is entirely a matter of chance.”

“If you mention my name at the Bell, you will be attended to.”

“I am excessively attentive to all those things.”

“If I had ever learnt, I should have been a great proficient.”

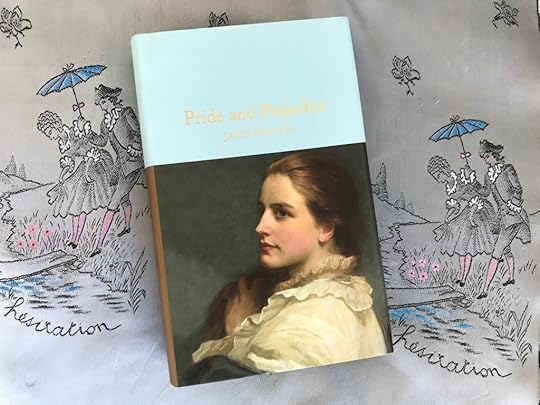

This lovely edition of Pride and Prejudice, curated by Barbara Heller, was a present from my friend Lisa in the first year of the pandemic. She and I have continued the tradition Janet and I started long ago, of giving each other identical copies of books we’d both like to add to our collections.

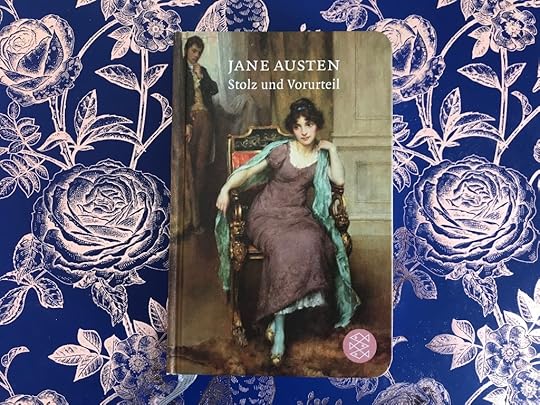

Bethie gave me this translation of Pride and Prejudice. I wish I could remember more of what I learned in my high school and university courses in German, so I could read it properly. But alas, though I did study German, I am not a great proficient.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also be interested in what I wrote for the 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice in 2013. “Jane Austen’s ‘Darling Child’ Meets the World” continues to be one of the most popular posts on my blog.

In 2013, I also wrote a series of blog posts on Pride and Prejudice at 200.

P.S. Bethie suggested the title “Living in Pride and Prejudice.” Thanks, B!

P.P.S. A note on the fabric and paper backgrounds I chose for these photos, for my friend Marianne—hi Marianne!—and anyone else who’s curious: the “hesitation” scarf was a gift from my husband and daughter, who found it last summer in a vintage clothing shop in London; the scrap of floral wallpaper is from my childhood bedroom; and the blue background in the photo of Stolz und Vorurteil is from a set of Jane Austen-themed folders my friend Lisa gave me for Christmas.

P.P.P.S. John Mullan wrote a wonderful short essay in honour of the 210th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice, for Jane Austen’s House Museum. He talks about the brilliance of Jane Austen’s dialogue, right from the first chapter in which we hear Mr. and Mrs. Bennet speaking. I like the way he points out that the “opening chapter of Pride and Prejudice is even daring in its omission. Elizabeth’s entrance is held back. Austen created the most irreverent and intellectually lively heroine the English novel had known, but kept her away from her opening scene.”

January 20, 2023

Rereading Persuasion, Part 2

I don’t think I’ll ever tire of reading about second chances. I finished rereading Persuasion, and I’ve been thinking about the fact that in addition to giving her heroine a second chance at happiness, Jane Austen gave herself a second chance at writing the ending of the novel. Apparently dissatisfied with her draft of the final chapters (which you can read here, if you haven’t come across them before), she wrote a new version, which includes the famous debate between Anne Elliot and Captain Harville over whether men or women are more constant in their devotion to the one they love.

Near the end of their conversation, Harville says, “I do not think I ever opened a book in my life which had not something to say upon woman’s inconstancy. Songs and proverbs, all talk of women’s fickleness. But perhaps you will say, these were all written by men.”

And Anne replies, “Perhaps I shall. Yes, yes, if you please, no references to examples in books. Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything.”

The revised chapters also include The Letter, which has made many a reader swoon. “You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone forever….”

Anne gets a second season of youth and beauty, as well as a second chance at happiness. I love reading about the way her “bloom” returns, during her visit to the seaside at Lyme:

“She was looking remarkably well; her very regular, very pretty features, having the bloom and freshness of youth restored by the fine wind which had been blowing on her complexion, and by the animation of eye which it had also produced.”

I always enjoy finding references to Jane Austen’s novels in contemporary fiction. I’d love to hear about examples you’ve found in your own reading, if you’d like to share. A few years ago, I wrote about finding Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in Emma Straub’s Modern Lovers, Jeanne Birdsall’s The Penderwicks on Gardam Street, and Gail Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine (in a blog post entitled “Elinor and Marianne”).

My guess would be that Pride and Prejudice and its characters turn up in contemporary novels more often than the other Austen novels do. A character inspired by Lady Catherine de Bourgh, for example, appears in Jennifer Robson’s 2015 novel After the War is Over, which is set in England in 1919. The heroine, Charlotte Brown, a former governess and nurse, receives an unexpected call from the imperious Lady Cumberland, who says her son has broken his engagement because of “some strange sort of attachment” to Charlotte. “He’s always had an affinity for those who are beneath him,” she claims.

When Charlotte asks if Lady Cumberland intends to “warn [her] off, à la Lady Catherine de Bourgh,” Lady Cumberland says she doesn’t know anyone by that name. Charlotte considers explaining the reference to Pride and Prejudice, but decides not to, because “Lady Cumberland had never approved of novels, and particularly not ones written by women.” Robson’s heroine responds to Lady Cumberland’s accusations with the same lively spirit as Elizabeth Bennet.

It’s a wonderful scene, with echoes of Jane Austen—Lady Cumberland calls Charlotte an “Insolent girl,” just as Lady Catherine calls Elizabeth an “Obstinate, headstrong girl”—and yet by the end, the relationship between the two women in Robson’s novel has changed significantly, as Lady Cumberland finds herself asking Charlotte for help. Her son has returned from the Great War a broken man, both physically and psychologically, and she realizes that Charlotte’s training and experience at the Special Neurological Hospital for Officers in Kensington might help him recover. Robson draws on Pride and Prejudice for inspiration, and creates something entirely new.

Charlotte Brown, like so many of us, turns to Jane Austen to help her understand her own life, whether she’s interpreting character or reading fiction in a time of crisis. When she and the other women at her boarding house gather in the sitting room for safety during a riot, Charlotte tries to persuade herself that she can learn to be happy and strong on her own, that she will survive the challenges that lie ahead of her. The novel she picks up to read to her friends is “a much-loved copy of Persuasion.” “Shall I read to you all?” she asks. “I think I have just the book for the occasion.”

After I finished rereading Persuasion, I went back to reread the guest post my friend Maggie Arnold wrote for the blog series I hosted in 2018, in honour of the 200th anniversary of the publication of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion.

Maggie writes that when Anne and Captain Wentworth first fell in love, “he was a young naval officer who had not yet proved himself—his early promise and energetic temperament were as yet untried.” And “Anne herself was inexperienced, a weakness which only time could correct, as she comes to know more people and to witness their failures and successes.” Eventually, she “can clearly see the path of her desire as the life to which she can commit herself, now with the maturity of ‘a collected mind.’ She knows her own worth, and others acknowledge it, too.”

I think Maggie’s right that this process is central to the novel. The romance is important, but so is the education of the heroine, through which she “comes to know her place in the world.” If you’d like to read more, you can find Maggie’s guest post here: “What Women Most Desire: Anne Elliot’s Self-discovery.”

And here’s the link to Rereading Persuasion, Part 1, if you missed it.

Next week, let’s talk more about Pride and Prejudice, shall we? Saturday, January 28, 2023 marks 210 years since the day it was first published.

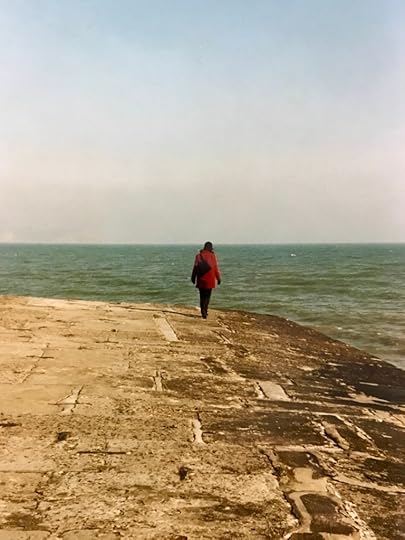

I found some photos from my visit to Lyme with my cousin Honor, about twenty years ago. During the two years that I was a postdoctoral fellow in England, she very kindly took me to many literary sites, including Milton’s Cottage, William Morris’s Kelmscott Manor, Samuel Johnson’s Birthplace Museum in Lichfield, and many more. We had such a wonderful time that day in Lyme—and I’d love to visit again. (Also—I loved that red coat. Wish I still had it.)

A postscript: Have you heard about Uzma Jalaluddin’s new novel, Much Ado About Nada, which is inspired by Persuasion? I just read a CBC article about it this morning—“Uzma Jalaluddin takes on Jane Austen’s Persuasion in her latest modern Muslim retelling of a rom-com classic”—and I enjoyed the excerpt that was included, so I’ve pre-ordered a copy. The publication date is June 13th.

January 6, 2023

Rereading Persuasion

After my sister and I watched the 1995 adaptation of Persuasion in December, I decided to reread the novel again. I’ve been thinking it works well to read it in January because it’s about second chances and new beginnings.

I love the passage in which Jane Austen tells us Anne Elliot “had been forced into prudence in her youth” and “learned romance as she grew older—the natural sequel of an unnatural beginning” (Volume 1, Chapter 4). And I love the marginal note next to it in a first edition, which may have been written by Jane’s sister Cassandra: “Dear, Dear Jane! This deserves to be written in letters of gold.”

I like the speed with which Anne’s sister Mary recovers her spirits when Anne comes to visit her at Uppercross Cottage: “She could soon sit upright on the sofa, and began to hope she might be able to leave it by dinner-time. Then, forgetting to think of it, she was at the other end of the room, beautifying a nose-gay; then, she ate her cold meat; and then she was well enough to propose a little walk” (Volume 1, Chapter 5).

And I like the description of the Musgroves, who, “like their houses, were in a state of alteration, perhaps of improvement” (Volume 1, Chapter 5). This comparison also seems appropriate for January, a time when so many of us attempt to make alterations, perhaps improvements, in our lives.

I’m fascinated by the scene in which Anne encounters her former fiancé, Captain Wentworth, for the first time in eight years, and tries to reason with herself that since so much time has passed, she ought not to feel so much:

How absurd to be resuming the agitation which such an interval had banished into distance and indistinctness! What might not eight years do? Events of every description, changes, alienations, removals,—all, all must be comprised in it; and oblivion of the past—how natural, how certain too! It included nearly a third part of her own life.

Alas! with all her reasonings, she found, that to retentive feelings eight years may be little more than nothing.

(Volume 1, Chapter 7)

I’ve underlined and memorized many passages from this novel over the years, and I think my all-time favourite is probably Mrs. Croft’s response to Captain Wentworth when he says he “hate[s] to hear of women on board” a naval vessel:

“But I hate to hear you talking so, like a fine gentleman, and as if women were all fine ladies, instead of rational creatures. We none of us expect to be in smooth water all our days.” (Volume 1, Chapter 8)

I took this photo of Halifax Harbour and McNabs Island on a walk at Point Pleasant Park earlier this week.

When I visit Point Pleasant I always think of Jane’s brother Captain Charles Austen and his wife Fanny, who sailed past McNabs Island into Halifax Harbour in 1809 and again in 1810 and 1811, when he was serving on the North American Station. And of her brother Admiral Sir Francis Austen, who lived at Admiralty House in Halifax between 1845 and 1848, when he was Commander-in-Chief of the North American and West Indies Station.

Fanny Austen often sailed with Charles and endured the hazards of several voyages, including a snowstorm in late November 1809, when they were sailing out of Halifax on board HMS Indian on their way back to Bermuda. My friend Sheila Johnson Kindred has written about the storm in her splendid book Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister: The Life and Letters of Fanny Palmer Austen: “Just out of Halifax the Indian met ‘strong gales with sleet and snow.’ By the evening the ‘gale increased’ and ‘the ship was labouring and shipping heavy seas.’” Fanny was caring for her first child, Cassy, who was eleven months old, and she was almost seven months pregnant with her second child. The journey must have been extremely difficult. “Imagine Fanny’s relief,” Sheila says, “when land was sighted and they ‘made all sail’ for St David’s Head, Bermuda, arriving in St George’s on 12 December after a harrowing voyage of fifteen days, almost twice as long as the journey usually took.”

If you’d like to know more about Charles and Fanny Austen, Francis Austen, and their families, and the places they visited when they were in Halifax, you’ll find more details in the walking tour Sheila and I created a few years ago when the Jane Austen Society (UK) held a conference here.

December 30, 2022

Places I Want to Remember

As the year ends, I can’t help but look back, and I’ve gathered a few of my favourite photos from 2022 to share with you. I’m feeling lucky and grateful that my family and I had the chance to travel again, to New York City and Germany as well as our beloved Prince Edward Island, and some of our favourite places in our home province, Nova Scotia.

Snowdrops and crocuses in my mother’s garden

A spectacular July day at Queensland Beach on the south shore of Nova Scotia

Sunflowers on the north shore of Prince Edward Island

The Shakespeare Garden in Central Park, New York City

The view from the parking lot of a grocery store in Halifax, NS

Commemorative markers on the sidewalk in Endenich, Germany

The house in Bonn, Germany, where Beethoven was born

Cochem, Germany

Reichsburg Cochem

The Mosel River

Cologne Cathedral

Bonn Minster

Beethoven, in the Münsterplatz in Bonn

May the new year bring peace and joy to you and your loved ones.

December 23, 2022

“The Christmas tree on display in the drawing room window”

I bought a copy of Clare Keegan’s novella Small Things Like These when I was in Bonn earlier this month, without realizing that it was set in the days leading up to Christmas. A good friend had recommended the book when it was first published, and I’m so glad I finally got a copy and read it. Each word is carefully chosen, each scene carefully crafted.

It’s the story of a particular time—Ireland in the 1980s—and a particular person—Bill Furlong, a coal and timber merchant—but the choices he faces about how to treat other people—family or friends or strangers, nearby or far away—are choices we all face, all the time.

December was a good time to read this beautiful, powerful book. I know it’s one I’ll return to again and again. I also love the cover, and I enjoyed reading this analysis of the detail from Bruegel’s “Winter (Hunters in the Snow, 1565).”

Coffee with my sister at Thalia, a bookstore near the Altes Rathaus in Bonn, where we found Small Things Like These and some other good books:

The scene in which Furlong returns to the house where he grew up is especially memorable. Here’s the first part:

Now, driving up the avenue, the old oaks and lime trees looked stark and tall. Something in Furlong’s heart caught and turned over when the headlights crossed the rooks and the nests they’d built and he saw the house freshly painted, with electric lights burning in all the front rooms, and the Christmas tree on display in the drawing room window, where it never used to be.

A snow-covered field in Bonn, from one of my late afternoon walks last week.

Thank you to everyone who’s responded to the blog posts I’ve written over these past few weeks. And whether you send comments and messages or not, thank you for reading! I’m grateful for the warm welcome and it’s wonderful to be back in touch with all of you again. I’ve missed our conversations.

I’m sending best wishes to you and your families and friends for a peaceful and happy holiday season. I hope you have lots of good books to keep you company, now and in the months ahead. Merry Christmas!

December 16, 2022

Happy 247th birthday to Jane Austen!

This year, I’m celebrating Jane Austen’s birthday in Bonn, Germany. My sister and I raised a glass in Jane’s honour at the Christmas Market in the Münsterplatz, where we like to go for coffee or a glass of Glühwein “with” Beethoven.

For Beethoven’s 250th birthday in 2020, seven hundred gold and green statues by Ottmar Hörl, all about one metre high, were placed in the Münsterplatz, near the famous 1845 statue (above) by Ernst Julius Hähnel and just a short walk from the house where Beethoven was born. Many of the small statues are now on display in nearby shops.

I can’t help picturing hundreds of small statues of Jane Austen, lined up outside Chawton Cottage or Winchester Cathedral, or perhaps on the site of Steventon Parsonage, where she was born. Maybe in gold and turquoise, in honour of the beautiful ring she owned?

We’ve also celebrated by watching the 1995 adaptation of Persuasion. (It’s so good! We’ve both seen it many times, but had never watched it together.) And, in honour of Marianne Dashwood, I’ve been admiring dead leaves at the Bonn University Botanic Gardens and at Beethoven’s House.

The courtyard at Beethoven’s House:

As I mentioned in last week’s post, I’m looking for a title for the new blog series I’m planning, in honour of Sense and Sensibility. Please send ideas! If I end up choosing the title you suggest, I’ll send you a packet of cards I bought this week at Beethoven’s House.

Here’s a photo of my sister Bethie, the Poppelsdorfer Schloss, and a ginkgo tree that was planted in the Botanic Gardens around 1870:

Swamp cypress in the Botanic Gardens:

Since I know not everyone shares my passion for dead leaves, I’ll add a few photos of berries, mistletoe, and flowers.

Happy 247th, dear Jane!

December 9, 2022

Celebrating Sense and Sensibility

I’d love to hear your suggestions about a title for a new blog series celebrating Sense and Sensibility, please. Laurel Ann Nattress proposed “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” for my 2014 series, Nora Bartlett gave me the title “Emma in the Snow” in 2015-16, and in 2018, Adam Q named “Youth and Experience: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion.” Please help save me from titles that are “very dull indeed,” such as the one I chose for “Pride and Prejudice at 200”!

It will be wonderful to celebrate Sense and Sensibility and Jane Austen’s 250th birthday with all of you in 2025, and in the meantime, I’m looking forward to Jane’s 247th birthday next Friday, December 16th. I’m in Germany with my sister Bethie right now, and we’re thinking about celebrating the 247th at the Christmas Market in Bonn.

Earlier this week, there was snow in Bonn, which is rare in early December. It was lovely to see flowers for sale outside even on a snowy day.

Bonn in the snow:

We’ve been to the Christmas Market a couple of times already and we’re planning to go again. Do you have plans for celebrations on (or near) Jane’s 247th birthday?