Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 12

February 14, 2024

Celebrating Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and L.M. Montgomery’s 150th Birthday

I’m delighted to announce “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” and “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” two exciting projects I’m planning for later this year.

Contributors to the Sense and Sensibility blog series include:

Finola Austin, Elaine Bander, Deb Barnum, Sandra Barry, Cheryl Bell, Matthew Berry, Diana Birchall, L. Bao Bui, Kathy Cawsey, Carol Chernega, Lori Mulligan Davis, Lizzie Dunford, Susan Allen Ford, Paul Gordon, Heidi L.M. Jacobs, Natalie Jenner, Hazel Jones, George Justice, Theresa Kenney, Deborah Knuth Klenck, Emily Midorikawa, Laurel Ann Nattress, S.K. Rizzolo, Peter Sabor, Vic Sanford, Marilyn Smulders, Emma Claire Sweeney, Joyce Tarpley, Janet Todd, and Deborah Yaffe, along with two teenagers, Gail and Ria, who are reading S&S for the first time.

And for the L.M. Montgomery series (so far):

Lesley Clement, Brenton Dickieson, Trinna Frever, Sue Lange, Naomi MacKinnon, Nili Olay, Liz Rosenberg, Kate Scarth, and Marianne Ward.

I’m excited about both parties and I hope you, dear readers, will join the conversations! Feel free to invite friends as well—if they’re interested, they can subscribe on my website.

You can also find me on Instagram and Facebook.

On this February day (yet another snow day in my part of the world), let’s imagine we’re in a garden in Hampshire or Prince Edward Island, drinking raspberry cordial, currant wine, or Constantia wine—raising a glass in honour of the brilliance of Jane Austen and L.M. Montgomery.

“I should think Marilla’s raspberry cordial would prob’ly be much nicer than Mrs. Lynde’s.”

– L.M. Montgomery, Anne of Green Gables, Chapter 16

I took this photo of a glass of homemade raspberry cordial at the Blue Winds Tea Room in PEI a few years ago.

“I have just recollected that I have some of the finest old Constantia wine in the house that ever was tasted, so I have brought a glass of it for your sister.”

– Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility, Volume 2, Chapter 8

Many thanks to my friend Nili Olay for sending me these photos of Constantia wine.

The “Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” will begin on June 20, 2024 and run through to the end of the summer.

Long-time blog readers will know that I like to celebrate significant anniversaries for Austen novels: I had fun celebrating the 200th anniversaries of Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion and Northanger Abbey here. But since I started in 2013 with P&P, I missed the chance to celebrate the 2011 anniversary of S&S with a blog series.

Thus, with the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth coming up in 2025, I’ve decided this is a good time to celebrate her first published novel.

“‘A world of wonder’: L.M. Montgomery at 150” will begin in October—because “I’m so glad I live in a world where there are Octobers,” as Anne says in Anne of Green Gables—and run to the end of November. Montgomery was born on November 30, 1874.

A couple of other things that are coming up this year:

In May, my friend Naomi MacKinnon and I are hosting a readalong for Montgomery’s 1910 novel Kilmeny of the Orchard.

And I have some plans in the works for December, as we prepare to celebrate Jane Austen’s 250th birthday in 2025. Stay tuned!

In the meantime, if you’re interested, you can read about previous blog celebrations for novels by both Austen and Montgomery here.

I’m looking forward to celebrating with you! Here are a couple of old photos of my daughter, about to enjoy cake with her raspberry cordial at the Blue Winds Tea Room:

And I’ll add a photo of some forsythia branches given to me by my friends Sheila and Hugh Kindred the other day.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“Wondering what will happen next” (a “scrapbook” post that begins with Shawna Lemay’s new book Apples on a Windowsill)

“While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence” (a poem by Sandra Barry)

January 26, 2024

“Wondering what will happen next”

I’m reading Shawna Lemay’s beautiful and thought-provoking new book Apples on a Windowsill, a collection of essays on still life, memory, art, and marriage, and I’m fascinated by what she says about how a still life can both stop time and serve as a moment of suspense: “The question hovers: what happens next? And it gives us an interval to dream new possibilities.”

Shawna talks about wanting to “escape into a favourite movie where I know that the ending is a happy one,” such as “Bridget Jones’s Diary or an adaptation of Pride and Prejudice or Persuasion.” In life, she says, “we have no idea if the ending is a happy one. The thing most of us have in common is wondering what will happen next.”

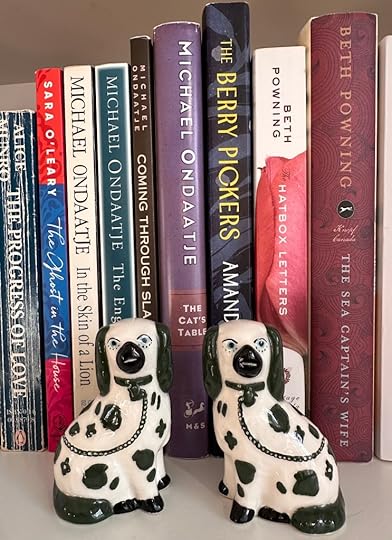

Reading her words in an essay entitled “The Loophole” about how she’s “interested in the history and secrets and stories of things themselves,” I thought of what Anne of Green Gables says about how it’s easier to dream in a room where there are pretty things. Shawna writes, “I like rocks and odd china ornaments and chipped cups and smooth bowls. I like pearl earrings and old weathered chairs and water pitchers. I like fading flowers and green bottles and books. I like things. I like listening to the music and silence in things. What do they say about us, and what are they whispering to us about our lives and this world, this planet?”

(Gog and Magog, replicas of the much larger ceramic dogs L.M. Montgomery owned, which make an appearance in Anne of the Island. “I think a great deal of those dogs,” says Miss Patty. “They are over a hundred years old, and they have sat on either side of this fireplace ever since my brother Aaron brought them from London fifty years ago. … Gog looks to the right and Magog to the left.”)

(Coffee mugs with broken handles, repaired and repurposed to hold pens and pencils and other supplies and treasures, including two “quill pens” made by my daughter when she was younger.)

(I think I’ll call this one, “Pearls and Dust.”)

(Fading flowers. I took these pictures last week, in between reading Shawna’s essays.)

“The still life can be a small world that speaks about the larger one,” Shawna writes. “It can be witness, consolation, a secret message, the arrow you launch through a narrow opening, a dream we once had or will have. A still life is in time but it also stops time, is out of time.”

Later in the same essay, she repeats these words: “A still life stops time, is out of time, occasionally offering the viewer that rupture/rapture.” Still life can bring a “moment of transcendence” that allows us to see “through to the other side,” an “opening or loophole where we drop into the sheer mystery of being.” To me, the experience sounds very much like what L.M. Montgomery describes as “the flash,” in Emily of New Moon. I quoted the passage here last month:

“It had always seemed to Emily, ever since she could remember, that she was very, very near to a world of wonderful beauty. Between it and herself hung only a thin curtain; she could never draw the curtain aside—but sometimes, just for a moment, a wind fluttered it and then it was as if she caught a glimpse of the enchanting realm beyond—only a glimpse—and heard a note of unearthly music.”

Like Montgomery, Shawna uses the word “realm” to describe this world of mystery and beauty, but she maintains that it is here, rather than “beyond”: “The other realm,” Shawna writes, “is not beside this one, it is this one, and we only need a little light, a sense of composition, a love of the inadvertent, an appreciation for the humble, and there it is.”

“Everyone’s home is full of still lifes,” she says. “We make still lifes inadvertently all day long”: “the cereal box on the table by the jug of milk”; “the lunch bag on the counter beside briefcase or satchel and car keys”; the book “on a side table, along with a glass of water, our spectacles.” She suggests that “the most profound function of a still life” may be “to remind us that however messed up our lives are and have been, we can find order and harmony and calm out of the at times ridiculous horridness and tawdriness of daily existence. … We can bring forward the weight and heaviness that we have carried throughout our lives and bring it into the light.”

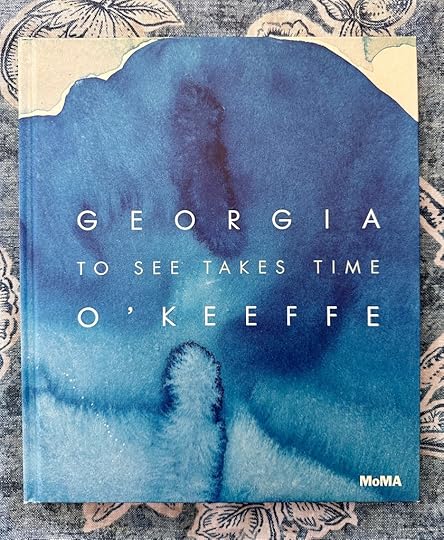

In an essay on “Women’s Lives, Women’s Still Lifes,” Shawna raises questions about finding the confidence to create art. She quotes a couple of powerful lines from Georgia O’Keeffe:

“I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing that I wanted to do.”

“It’s not enough to be nice in life. You’ve got to have nerve.”

Shawna writes that “one of the responses to a lot of work by women is to ignore it. Historically, creative women have been trivialised, especially those who had more than one talent.” Citing an article by Jonathan Jones, she gives Charlotte Brontë as an example. Jones writes of a self-portrait by the young Charlotte that he finds “unsettling” because of “the talent it shows. Could she have been an artist as well as a great writer—and how many other talented women have found their ability to draw trivialised or suppressed through the centuries?”

Shawna says that for her, part of the appeal of literature is that “it could be hidden,” and thus “more possible” than art: “you could do this alone, with a pen and paper.” “Which is why,” she says, “reading about Jane Austen hiding her work under her blotter, the supposed creak that alerted her to another’s presence, always spoke to my heart. I wasn’t bold. Not in the least.”

She quotes from Eavan Boland’s poem “The Rooms of Other Women Poets,” in which the poet wonders about other poets at their desks, reaching for the lamp as dusk falls. “We just want to work,” Shawna says. “I in my room, you in yours. I don’t want to be in competition with you, but to send my good wishes to you so that you can send yours to me.”

There’s a kind of magic in this wondering, this sending of good wishes to other poets and writers and artists at work in other rooms, other spaces. This connection with others who are drawn to create. This curiosity about what they, and we, will create next. This belief in possibility, and in the value of dreaming “new possibilities,” even though we have “no idea if the ending is a happy one.”

Those of you who live in Alberta (hello, dear friends and relatives!) might like to go to the book launch for Apples on a Windowsill, which is at Audreys Books Ltd. in Edmonton on February 1st at 7pm.

I wrote about Shawna’s novel Everything Affects Everyone here last year: “Secrets that everyone knows.”

You might also be interested in an interview Shawna did for Open Book, in which she answers questions and also asks many of her own. “What can the process of assembling a still life tell us about how we can make our lives? … Can looking closely at art and things improve our everyday lives? If we change one thing in a composition, how does that change another? And if we can recompose a still life, can we recompose our lives, our thinking?”

This last question makes me think of something my grandfather said years ago: my father asked, “how are you?,” and Grandpa answered, “Better, since I changed my attitude.” I and several members of our extended family think of this exchange often, especially in challenging times.

Kerry Clare wrote about Apples on a Windowsill on her blog recently: “while it’s called Apples on the Windowsill, it’s as much about lemons, not only about how the light falls on their unwinding rinds, but also what we do when life gives them to us. Which is to say, put them in a bowl and take their picture, and notice them, how they absorb the light, and how they change….”

(A couple of photos I took for an online photography class a few years ago.)

I have a few other things to share with you today. First, I was charmed by Margaret Renkl’s description of a New Year’s resolution she made in 2021: “Resolving to write a letter every day would help me use up the stamps and notecards accumulated over many years, repudiate the entire virtual world, and honor my grandmother at the same time. It’s one of the nicest resolutions I’ve ever made.”

Next, Diana Birchall’s impressions of the Jane Austen Society of North America AGM in Denver, Colorado, last November: “Jane in Denver.” I attended the conference online, which was lovely, but also made me miss the joys of attending in person. I was especially sad to miss seeing Syrie James’s play “Pride and Prejudice: Six Rocky Romances.” I have fond memories of watching Syrie and Diana and other friends performing at the 2014 AGM in Montreal, in a play the two of them co-wrote called “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park.” (The blog post I wrote after the 2014 AGM includes a photo of the cast.)

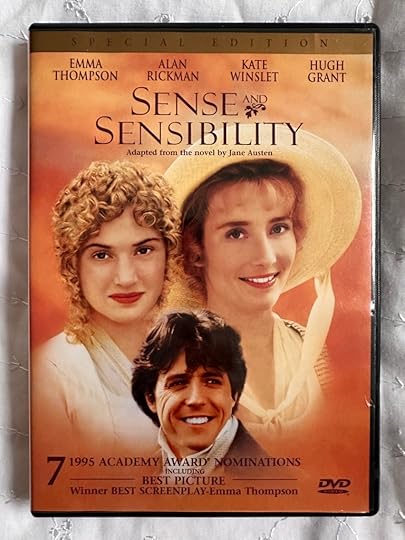

Laurel Ann Nattress wrote a lovely blog post last Sunday about the 1995 Sense and Sensibility movie, praising (among other things) the cast, Emma Thompson’s use of humour and irony in the Oscar-winning screenplay, and the symbolism of the coins thrown into the air in last scene: “This story is all about cash and those who have it, and those who do not.”

Some of you might be interested in the call for papers from the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies for a special collection entitled “#Maud150: Back to the Future.” November 30, 2024 marks the 150th anniversary of Montgomery’s birth, and “#Maud150 is a time to reflect, reappraise, and envision: we particularly invite submissions–scholarly articles and creative work (written, visual, or audio-visual)–about celebration and commemoration and those that consider the past, present, or future in relation to Montgomery’s art, life, context(s), or legacies.”

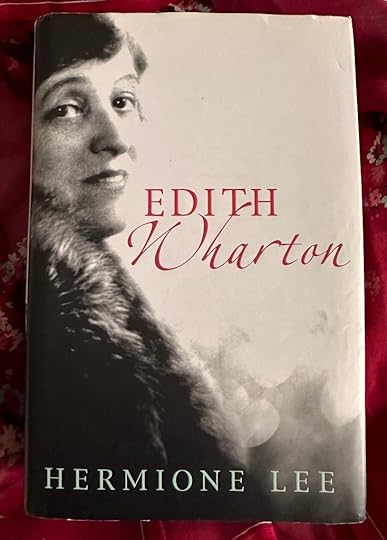

This past Wednesday, January 24th, was the birthday of Edith Wharton, who was born in New York City in 1862. I enjoyed listening to this podcast from the American Writers Museum, in which Wharton scholars Emily J. Orlando and Anne Schuyler talk about Wharton’s life and work.

Here are some photos I took on a recent trip to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and the lighthouse at Cape Forchu:

As always, the “bend in the road” makes me think of the last chapter of Anne of Green Gables.

And I’ll end with a photo from Point Pleasant Park in Halifax:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence” (a poem by Sandra Barry)

“Happy 100th Birthday to Emily of New Moon!”

I’ll be back in February—see you then.

January 12, 2024

“While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence”

For today’s blog post, I have the great pleasure of introducing a poem by Sandra Barry. You might remember her beautiful poem “Old Rusty Metal Things,” which I shared here last April, and the wonderful photos taken by her sister Brenda Barry, which I’ve included in several blog posts over the past year or so. I asked Sandra recently if she’d like to share another poem with all of you, and I was delighted when she said yes and sent me “While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence.”

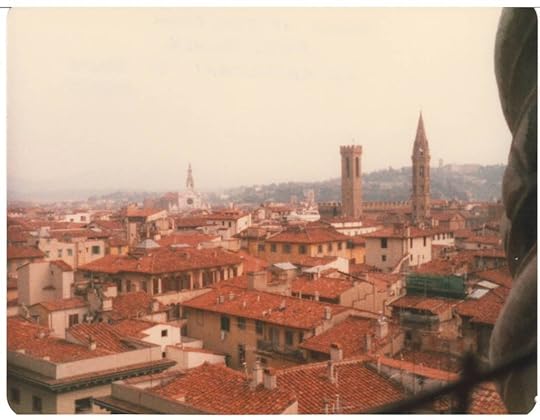

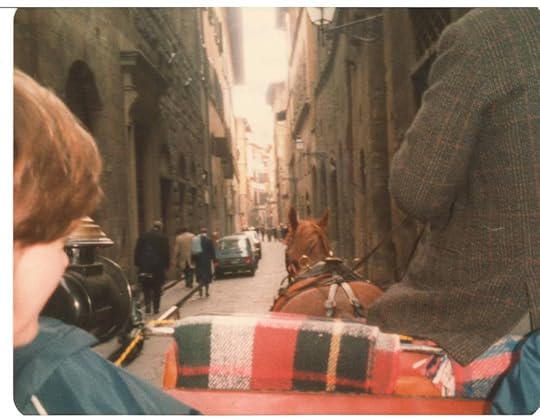

This poem was inspired by Sandra’s trip to France and Italy in April of 1984, almost forty years ago, with her sisters Donna and Brenda and friend Pam. She writes, “That brief visit to Florence was memorable, but it had left my active thoughts for years until I found a used copy of Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence in some used bookstore—I am not much of a fan of her fiction (she wrote an infamous novel, The Group, about Vassar, with one character supposedly based on Elizabeth Bishop—I couldn’t get past page 5 of it). But I like her non-fiction, which I find much more lively. Anyway, I read the Florence book quickly and it triggered a flood of long forgotten memory—quite the experience—and I immediately went looking for the photos from that trip and found that they reflected most of the vivid memories I had retained. Travel was so important to Bishop—and she did visit Italy at least once during her life—though it was Rome that impressed her most.”

Sandra says, “The photos were taken by Donna with a tiny film camera she had—might have even been one of those disposable jobs. They are quite poor quality, but there is something about their vagueness and distance that actually works with the poem, which is a memory poem.”

Sandra is a freelance editor and an Elizabeth Bishop scholar, and her book Elizabeth Bishop: Nova Scotia’s “Home-Made” Poet, was published by Nimbus in 2011. You can read more about both Sandra and Bishop in the introduction to “Old Rusty Metal Things.”

(I wish I could show the poem single-spaced, but for some reason, WordPress won’t let me change the format.)

While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence

Casting my mind back to my own brief encounter

—an afternoon overwhelmed by noise and stone;

the milky sunshine, the vague sky contrasting

the perpendicular,

the narrow straight up streets and a short expensive

carriage ride. Two photographs. One: a vanishing point

from the seat of the carriage, the claustrophobic height

of heavy stone receding to where my memory resides.

I do not remember the soft brown horse, the pale green

tweed of the driver. I do remember a glimpse

of stunning black eyes among thousands.

Two: the soft brown horse freed of his tourist haul

feeding from a bag of oats hung on his harness,

his flanks and back covered by a blanket

to keep the April chill away.

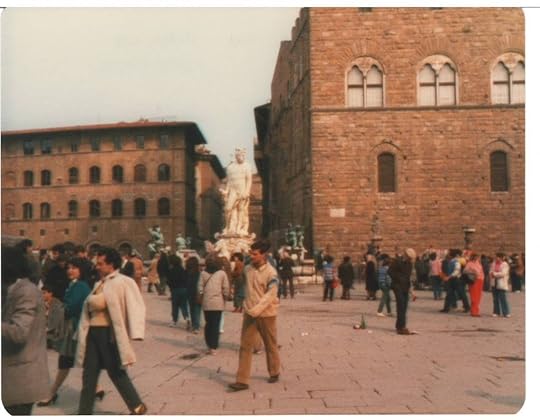

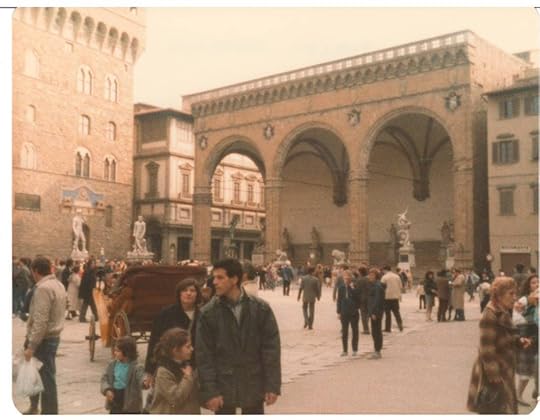

The narrow streets have opened into a square

walled by severe history. In spite of the evidence

there is no “local colour” in Firenze.

Everywhere mythical statues compete with humanity,

so many pasts in one place is disorienting.

I remember seeing only surfaces, hardly sensing

the centuries. Yet here, in another photograph,

is Neptune in his fountain, the Arno god who wanders

the Piazza della Signoria under the full moon.

And there I am with a friend (and countless strangers)

dwarfed by the elegant arches of Loggia dei Lanzi,

which harbours so much violence frozen in marble,

sealed in bronze. The matrons and lions

bear witness to rape and decapitation;

the crowds barely seem to notice.

Did we know something beyond Michelin?

Or did we herd into the Piazza like so many generations

of Florentines anticipating a harangue

—the harangue of guidebooks and postcards.

The Florentines ignored us grandly.

I stand there, caught in one moment;

but I do not remember what I felt.

I remember the rigorous ascent of Giotto’s bell tower

(the Duomo, the Dome, was closed for repair).

There is no nearby place to see all of Santa Maria

del Fiore. It rises like a mountain from a sea

of red tile, crowded by buildings, traffic, people.

I remember only din suddenly falling

away, immensity, silence spiralling into darkness.

From the top of the tower, one photograph

dominated by the white-washed sky

and the “cruel tower of Pallazo Vecchio

piercing the sky like a stone hypodermic needle.”*

In relative terms, a quick jab from Florence,

and how unaware am I still of Dante’s exile,

Michelangelo’s vanity, Leonardo’s obsessions,

Cellini, Donatello, Uccello, Galileo.

And the buried life and death of Etruscan augury.

The Uffizi was closed, so the portraits

had no chance to stare at us, four bewildered

maidens wandering among the columns, blinking.

* McCarthy, p. 36.

Sandra writes that she and her friend Pam are in the photo above, of the Piazza del Signoria, “standing looking stunned among the throng.”

She adds that Mary McCarthy “is one of the talking heads in the wonderful 1989 documentary about Elizabeth Bishop in the Voices & Visions series that can be found and watched on the Annenberg Foundation site.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages, and I’m sure Sandra will be, too. Thanks for reading!

If you missed my recent post on L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon, you can find it here. I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with a scrapbook blog post—see you then.

December 29, 2023

Happy 100th Birthday to Emily of New Moon!

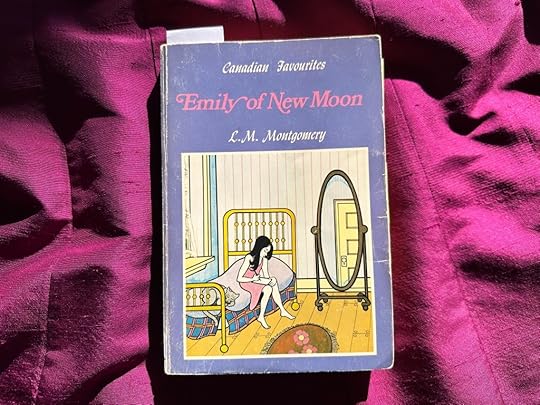

The first novel in L.M. Montgomery’s trilogy about a young writer, Emily Byrd Starr, was published in 1923. One hundred years later, although Emily of New Moon has many fans, she isn’t nearly as well-known as Montgomery’s most famous heroine, Anne of Green Gables. Elizabeth Egan asked recently why Emily is “forever in Anne’s shadow,” and wondered if it’s “possible that her story holds up even better than Anne’s after all these years.”

Emily of New Moon is one of my favourite novels, and after I had finished The Story Girl and The Golden Road last month, I decided to reread the first Emily novel again during this anniversary year. The opening chapter is deeply moving, with its account of Emily’s father’s death and her feeling of being alone in the world. This is also where we learn about “the flash”: “It had always seemed to Emily, ever since she could remember, that she was very, very near to a world of wonderful beauty. Between it and herself hung only a thin curtain; she could never draw the curtain aside—but sometimes, just for a moment, a wind fluttered it and then it was as if she caught a glimpse of the enchanting realm beyond—only a glimpse—and heard a note of unearthly music.”

On this particular evening, “the dark boughs against that far-off sky” are the source of “the flash” and that note of music. Like Sara Stanley in The Story Girl, who thinks in colours, Emily has a form of synesthesia, as images give her access to “unearthly music.”

Emily’s unshakeable conviction that she is a writer is the main highlight for me, every time I reread this novel. She will write even if she doesn’t have paper, even if she is forbidden to write because her aunt believes novels are wicked, even if teachers or classmates or relatives—or friends and mentors—mock her.

She finds inspiration in nature, where she feels alive to the possibilities of the future: in the spruce barrens, she feels that “Anything might happen there—everything might come true” (Chapter 1). She reminds me of Sara Stanley here: “‘I always feel so satisfied in the woods,’ said the Story Girl dreamily, as we turned in under the low-swinging fir boughs. ‘Trees seem such friendly things’” (The Story Girl, Chapter 28). When she is told she is “not of much importance,” Emily declares, like Jane Eyre before her, that “I am important to myself” (Chapter 3; Jane says, “I care for myself. The more solitary, the more friendless, the more unsustained I am, the more I will respect myself.”)

I read recently that if you “think of everything as potential material,” then “you can bear almost anything,” and I wonder if it’s true. Abigail DeWitt says she teaches her writing students this trick.

When Emily’s relatives are busy passing judgement on her, she feels “She would have given anything to be out of the room.” At the same time, however, “in the back of her mind a design was forming of writing all about it in her old account book. It would be interesting. … she felt that she would rather like to write it all out” (Chapter 3).

I thought of this passage again earlier this week when I reread Madeleine L’Engle’s memoir A Circle of Quiet (recommended by my sister Bethie). L’Engle writes that after she had received yet another rejection letter on her fortieth birthday, after a decade of seeing A Wrinkle in Time and other novels rejected, she felt she needed to stop writing. She believed she was being told to “Stop this foolishness and learn to make cherry pie.” She “covered the typewriter in a great gesture of renunciation” and walked around the room, sobbing. However, she stopped suddenly when she realized that while she was crying, her “subconscious mind was busy working out a novel about failure.” She uncovered the typewriter. “I had to write,” she says.

At school, when Emily is taunted by classmates who quiz her about whether she can sing, dance, sew, cook, knit lace, or crochet—the answer is always “no”—she says that one thing she can do is write poetry, and “at that instant she knew she could” (Chapter 8). Like Fanny Price in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, her education is seen as defective because she doesn’t possess the usual “accomplishments” of a young lady-in-training. Fanny’s cousins find her “prodigiously stupid” because she hasn’t memorized lists of rivers and kings and because she calls the Isle of Wight “the Island, as if there were no other island in the world” (Volume 1, Chapter 2). I expect Anne Shirley and Emily Starr would see Fanny as a kindred spirit, though for them “the Island” is Prince Edward Island.

Writing, for Emily, proves to be a way of healing grief and sorrow. Through writing long letters to her late father, she finds that “The bitterness died out of her grief” because “Writing to him seemed to bring him so near” (Chapter 9).

When her teacher calls her poems “trash” and tries to burn them, Emily vows to protect her writing with her life: “they should not get her poems—not one of them, no matter what they did to her ” (Chapter 16). Yet the experience is so traumatic that she is unable to write about it: “The shame of it all was too deep and intimate to be written out, and so she could find no relief for her pain.”

I like the passage in which Emily does battle with Aunt Elizabeth over the book she’s reading about the human body, which “tells about everything that’s inside of you.” She’s currently reading about the liver. Aunt Elizabeth is “horrified”: “This was worse than novels. … Things that were inside of you were not to be read about” (Chapter 21).

Like Montgomery herself, Emily finds inspiration in a poem about “The Alpine Path” (the title of Montgomery’s autobiography):

Then whisper, blossom, in thy sleep

How I may upward climb

The Alpine Path, so hard, so steep,

That leads to heights sublime.

How I may reach that far-off goal

Of true and honored fame

And write upon its shining scroll

A woman’s humble name.

At age twelve, Emily writes, “I, Emily Byrd Starr, do solemnly vow this day that I will climb the Alpine Path and write my name on the scroll of fame” (Chapter 27).

Montgomery says in her autobiography, “It is indeed a ‘hard and steep’ path; and if any word I can write will assist or encourage another pilgrim along the way, that word I gladly and willingly write.”

Emily believes in the power of books to create community: “Books were Emily’s friends wherever she found them,” and she insists to Aunt Elizabeth that “I thought books belonged to everybody” (Chapter 6).

Over the past century, Emily of New Moon has inspired countless writers, with Emily’s firm commitment to her vocation. Writing is as essential to her as breathing: “She must write stories—and Aunt Elizabeth must know it—that was the way it had to be. She could not be false to herself in this—she could not pretend to be false” (Chapter 29). Like Madeleine L’Engle, who says in A Circle of Quiet that “It was not up to me to say I would stop, because I could not,” Emily feels she doesn’t have a choice: “Why, I have to write—I can’t help it by times—I’ve just got to” (Chapter 31).

Her belief in herself and her work sustains her through repeated conflicts with Aunt Elizabeth and through conversations with people who appear to be on her side, including Father Cassidy and Dean Priest. Elizabeth Rollins Epperly writes in The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance that “On the surface of it, the males, as Judith Miller says, ‘seem to encourage writing,’ but the underlying and encoded messages about woman’s place in the male literary establishment eventually make their quality of support suspect (not Cousin Jimmy’s or her father’s, but then Cousin Jimmy is ‘simple’ and her father is dead).” Father Cassidy “does not take her writing seriously, whatever he may say to her. To many readers this will be a chilling chapter—though Montgomery may not have meant it to be.” Epperly suggests that “his patronizing is but a gentle prelude to the caressing contempt Dean himself will later show for Emily’s ‘pretty cobwebs.’”

When Emily reaches out to grasp a “magnificent spray of farewell summer” (asters) at the edge of a cliff and slides down the slope toward the rocky shore, she is rescued by Dean, who at first seems like a kindred spirit (Chapter 26). He understands that she must write: “you have the itch for writing born in you,” he says. “It’s quite incurable.” He asks what she’s going to do with it, and she replies, “I think I shall either be a great poetess or a distinguished novelist.”

Like Father Cassidy, who has mocked Emily’s epic poem—“One av the seven original plots in the world”—Dean finds her ambition amusing: “Having only to choose,” he says. “Better be a novelist—I hear it pays better.” Even the people who seem to understand her vocation are as tyrannical and threatening as Aunt Elizabeth—or perhaps even moreso, since at least Emily knows where she stands with her aunt. Dean announces that her life is no longer her own: “your life belongs to me henceforth. Since I saved it it’s mine. Never forget that.” Although she responds at that moment with “an odd sensation of rebellion”—she “flung the big aster on the ground and set her foot on it”—she is later drawn to Dean.

As Epperly writes, “This is the most important gesture in all three of the Emily books—instinctively Emily fights against the power that wants to dominate her. And yet she leans towards Dean Priest, bends to him in the subsequent episodes, and does not understand that she, here, has rejected only part of his domination in refusing to acknowledge his right to own her. He will have to learn that, whenever she has accepted his judgment in place of hers, she has added to the cobweb fetters he flings round her.”

I’m interested in Alice Munro’s assessment (in her introduction to the New Canadian Library edition of the novel) of Dean Priest as an “invader,” who “disturbs the book so that the author, after a while, hardly knows what to do with him.” Mary Henley Rubio says in her biography of Montgomery that Dean may be a ‘Priest,’ but to adult readers he begins to feel unwholesome, more like a sexual predator than an older friend.” In the later books he’s also even more dismissive of Emily’s writing. “I’d hate to have you dream of being a Brontë or an Austen—and wake to find you’d wasted your youth on a dream,” he says to her in Emily’s Quest (Chapter 4). As Epperly writes, “it is Emily’s writing self, her very essence, that he eventually tries to destroy.”

Poetry, Munro says, is Emily’s response to “the flash,” a moment of joy, while prose “is her way of dealing with people, and often with situations in which she is powerless. We’re there as Emily gets on with this business, as she pounces on words in uncertainty and delight, takes charge and works them over and fits them dazzlingly in place, only to be bewildered and ashamed, in half a year’s time, when she reads over her splendid creation. This is wonderfully done. L.M. Montgomery makes us believe in ‘the flash,’ the moment of vision, the writing energy, the desperate commitment, of a female child living on a farm in Prince Edward Island….”

I like Munro’s conclusion about what mattered to her most when she first read Emily of New Moon, which was also “what was to matter most to me in books from then on,” and that was “knowing more about life than I’d been told, and more than I can tell.”

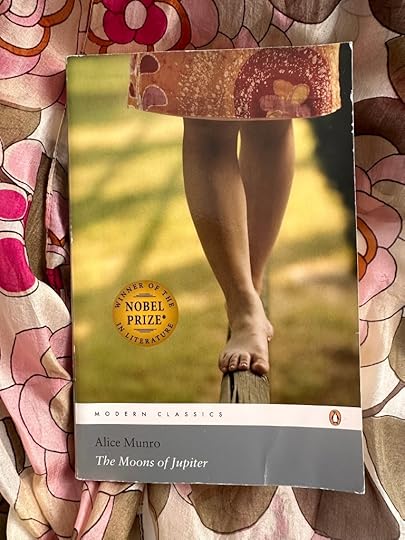

After I had finished rereading Emily of New Moon, I happened to read Munro’s story “Labour Day Dinner” (from The Moons of Jupiter), in which seventeen-year-old Angela, who has spent the summer reading “Anna Karenina, The Second Sex, The Norton Anthology of Poetry, The Autobiography of W.B. Yeats, The Happy Hooker, The Act of Creation, [and] Seven Gothic Tales,” sounds like Emily as she writes in her diary: “I want to have a truthful record of my whole life. How to keep oneself from lying I see as the main problem everywhere.”

Just as I enjoy returning to Anne Shirley’s “bend in the road” or Sara Stanley’s fascination with roads “because you can always be wondering what is at the end of it,” I loved revisiting Emily’s description of “the To-day Road, the Yesterday Road and the To-morrow Road” (Chapter 12). The To-day Road is “lovely now,” the Yesterday Road “used to be lovely,” before “Lofty John cut some trees down,” and the To-morrow Road is “just a tiny path in the maple clearing and we call it that because it is going to be lovely some day, when the maples grow bigger.” This passage made me think of three specific trees I have loved over the years—maple, spruce, and elm—all of which I mourned when they were cut down. And it made me appreciate the trees around our new house—maple, birch, elm—even more than I already did, and I feel inspired to plant another tree, maybe in the spring.

The three roads also brought back the memory of a long run on a prairie highway in the summer of 2015, when I was training for a half marathon. I set off that morning without thinking carefully about how far I would go (I never have been very precise about training for races), and I headed out of town on the highway that led to the cabin at the lake in southern Alberta that had been in my family for decades. I could have run all the way there, but then I might have had to call someone to pick me up. I stopped about halfway and took this photo.

I realized that I was, in a way, trying to run to the past, to the cabin as it was when I was a child, and no matter how carefully I trained for any distance, I would of course never be able to get there. I suppose I was running on the “Yesterday Road,” trying to reach what Montgomery calls the “golden road of youth,” which we can visit only in memory.

I turned around and ran back to town, back into the present, in which my grandparents’ health was failing, and I needed to learn how to say goodbye. They both died within the following year. In the summer of 2016, I visited Alberta again, and thought about them as my family and I drove around the province visiting relatives and friends. That summer, when I was out running, I often listened to Kev Corbett’s song “On the River Off the Lake”: “I kiss the air when I’m here / I kiss the water / I kiss the memory of my grandmothers and fathers.”

I also wrote about Emily of New Moon back in 2017, when my friend Naomi hosted a readalong for the three Emily novels:

“‘I am important to myself’: Emily of New Moon”

Many thanks to all of you for reading these blog posts over the past year. I’ll look forward to seeing you here in January. Happy New Year!

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

December 22, 2023

Season’s Blessings

Season’s Blessings and best wishes at Christmas to you!

I found this postcard at Effex Vintage last month, and I thought I’d send it to all of you with a wish for peace and happiness for you and your loved ones, and for people around the world.

I’m rereading L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon because this year is the 100th anniversary of the novel’s publication. I was touched by what Emily writes about the “Disappointed House” in one of her letters to her father:

I am finishing the Disappointed House in my mind. I’m furnishing the rooms like flowers. I’ll have a rose room all pink and a lily room all white and silver and a pansy room, blue and gold. I wish the Disappointed house could have a Christmas. It never has any Christmases.

Oh, Father, I’ve just thought of something nice. When I grow up and write a great novel and make lots of money, I will buy the Disappointed House and finish it. Then it won’t be Disappointed any more.

(Chapter 20)

In last Friday’s post, “Where to look for the threads,” I mentioned Jesmyn Ward. This morning I followed a thread from the Poets & Writers email newsletter to their 2013 profile of her. A few days ago I read a profile of her in the current issue of Vanity Fair, and I like what she says about how Mississippi has given her “one of a writer’s most cherished gifts. ‘This place taught me to sit very still, and to observe and to listen, and then to take what I observed and to translate that into language,’ she says. ‘This place taught me poetry.’”

In the new year, I won’t have time to write blog posts every Friday, but I’ll aim to write at least once a month, as I love writing these posts and I enjoy the conversations we have here and on social media, and in letters and emails. Many thanks to all of you for being here. I’m grateful for your company! Before the year ends, I’ll write one more post about Emily—see you next Friday.

Photos from the Annapolis Valley, by Brenda Barry

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

December 16, 2023

Sense and Enthusiasm

Happy 248th birthday to Jane Austen!

Last summer’s roses in the Historic Gardens at Annapolis Royal, photographed by Brenda Barry

To celebrate, I thought I’d write about an Austen-inspired novel I read recently. Polly Shulman’s novel Enthusiasm is a delightful YA romance inspired by Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, but also by less well-known elements of Jane Austen’s life and work, including a novel written by her niece Anna that was originally entitled “Enthusiasm” and later renamed “Which is the Heroine?” In a letter to Anna, Jane said, “I like the name ‘Which is the Heroine’ very well, and I daresay shall grow to like it very much in time; but ‘Enthusiasm’ was something so very superior that my common title must appear to disadvantage” (August 10, 1814). I missed Shulman’s novel when it was published back in 2006, and I’m grateful to my friend Lisa for giving me a copy.

“There is little more likely to exasperate a person of sense than finding herself tied by affection and habit to an Enthusiast,” says the narrator, Julia Lefkowitz, lamenting the extremes of her best friend and next door neighbour Ashleigh Rossi’s various enthusiasms, the latest of which is “the joys of Miss Austen’s work.” Usually, Julia follows where Ashleigh leads, but in this case, she has introduced Ashleigh to Jane Austen, and soon the Enthusiast is attempting to dress like an Austen heroine, addressing Julia as “my dear Miss Lefkowitz,” and plotting to find heroes for both of them by crashing the fall formal at a nearby prep school for boys, or, rather, “young gentlemen.” And Julia is worried that Ashleigh’s passion for Austen will overshadow her own. Nevertheless, she agrees to her friend’s plan, and with the convenient assistance of two young men who agree to act as their escorts, they attend the formal and begin to fall in love.

The problem, however, is that they can’t agree which of the young men is Mr. Bingley, and which is Mr. Darcy, or which of them is Jane Bennet or Elizabeth Bennet. Despite the contrast Julia draws between herself as the sensible one and Ashleigh as the Enthusiast, it doesn’t seem to have occurred to her that they might be Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, rather than Jane and Elizabeth.

I loved the names and nicknames in this novel. One of the young men, for example, is named Charles Grandison Parr, presumably after the hero of one of Austen’s favourite novels, The History of Sir Charles Grandison, by Samuel Richardson. Another student at the prep school is named Alcott Fish. The public school Julia and Ashleigh attend is called Byzantium High, and the school’s literary magazine is Sailing to Byzantium. And Julia thinks of her stepmother, Amy, as the “Irresistible Accountant,” or “I.A.” for short.

I also appreciated the way poetry is part of the way these teenagers communicate with each other, whether they’re analyzing speeches from Romeo and Juliet, accidentally speaking in iambic pentameter, pinning poems to the oak tree between Julia’s house and Ashleigh’s, or discussing assonance, alliteration, or acrostics. I don’t know how many teenagers actually talk this way, but it’s certainly fun to read about.

There are a few more Austen-related things I’d like to share with you today. First, a lovely paragraph from a blog post that Ellen Moody wrote a few years ago, in which she draws a comparison between the way she reads Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry and the way she reads Jane Austen’s novels. She writes that in Bishop’s “Sonnet” (1928) she finds “Bishop keeping herself calm by making order and harmony through making a poem which can harness the very rhythms of her heartbeat and body as she writes and we read it. This is the way I read Jane Austen’s novels, say Emma: the orderly rhythm of her sentences, their elegance and deeply felt content within patterns soothes and keeps me calm, strengthens me. This is what Bishop is doing through her very finger-tips, her lips, her whole body healing.” The poem opens with a “need of music that would flow / Over my fretful, feeling finger-tips, / Over my bitter-tainted, trembling lips, / With melody deep, clear, and liquid-slow.”

Ellen wrote a beautiful guest post for the blog series I hosted for the 200th anniversary of Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Persuasion: “‘For there is nothing lost, that may be found’: Charlotte Smith in Jane Austen’s Persuasion.”

Earlier this week on Vic Sanborn’s wonderful blog Jane Austen’s World, Rachel Dodge made a list of ways to celebrate Jane Austen’s birthday, in addition to reading/rereading the novels. She suggests making a donation to the Courtyard Restoration Appeal at Jane Austen’s House Museum, Chawton Cottage. Her list also includes Jane Austen’s Virtual Birthday Party, which is happening later today (8pm GMT; tickets are available from Jane Austen’s House Museum here). I won’t be able to attend, but if any of you attend the celebration, I would love to hear about it! Please comment on this post or send me an email.

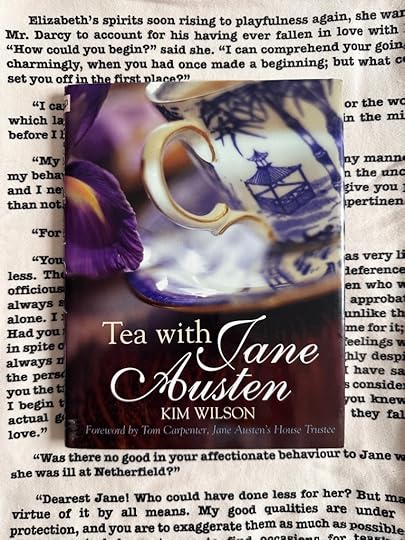

Rachel suggests making a sponge-cake, and provides a link to a recipe. “You know how interesting the purchase of a sponge-cake is to me,” Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra in 1808. In previous years, I’ve sometimes made syllabub for Jane’s birthday, using Kim Wilson’s recipe in Tea with Jane Austen.

The Pride and Prejudice scarf in the background of this photo of Kim’s book was a present from my friend Sandra Barry, an Elizabeth Bishop scholar (and sister of Brenda Barry, whose photos I often include in blog posts).

Do any of you have a favourite recipe for sponge-cake or syllabub, or another Austen-inspired dessert? Like Shawna Lemay, who likes to hear from friends about “a scone with plum jam,” or “sour cherry pie,” or “a new scarf,” I like to hear about such details. As I wrote in a blog post earlier this year, I’m a fan of Shawna’s theory of “The Sponge-Cake Model of Friendship.”

In her blog post for Jane Austen’s birthday, Deborah Barnum of Jane Austen in Vermont quotes George Austen’s letter to his sister about Jane’s birth: “We have now another girl, a present plaything for her sister Cassy and a future companion.”

Deb suggests joining/renewing membership in the Jane Austen Society of North America and/or donating to Chawton House, through the North American Friends of Chawton House.

From Deb’s post I learned of plans for a new statue of Jane Austen at Winchester Cathedral, to be unveiled in 2025, the 250th anniversary of her birth. The sculptor, Martin Jennings, says, “I have represented her rising from her table at Chawton as someone arrives at the door, moving in front of her work as if to disguise it. It is important for me that she should be accompanied by the tools of her trade, so that she is indissolubly associated with her working life.” You can see images of the memorial statue, and share feedback if you wish, on the Cathedral website.

Gillian Dow, former Executive Director of Chawton House, says, “I admire the quietly confident Jane Austen depicted by Martin Jennings here. She gazes into the distance, as if she were wishing the manuscripts composed at her writing table good fortune as they travel into the world to make their own way in it.”

Gillian wrote a guest post on “Emma Abroad” for my Emma in the Snow blog series in 2016, complete with photos of a 1951 Finnish book cover featuring “Emma in the Snow” and of George Justice’s edition of Emma, which Gillian read in the French Alps. She argues that even though many readers participate in and find value in literary tourism, “an immersive fictive experience … cannot, must not, depend on where one is when one reads a book. Whether sitting under an English Oak, next to a cactus, or up a brutalist skyscraper in the centre of a metropolis, one creates the world of a novel oneself.”

I agree with what Gillian says about the experience of reading. Books can take us anywhere, to real places and places that exist only in the imagination. As Emily Dickinson says, “There is no Frigate like a Book / To take us Lands away,” and “This Traverse may the poorest take / Without oppress of Toll.”

Someday, I’d love to go to Winchester for coffee (or tea) with my sister Bethie and the new Jane Austen statue. In the meantime, I can open a copy of Pride and Prejudice and read, for example, about a very impatient Elizabeth Bennet serving coffee:

Darcy had walked away to another part of the room. She followed him with her eyes, envied every one to whom he spoke, had scarcely patience enough to help anybody to coffee; and then was enraged against herself for being so silly!

“A man who has once been refused! How could I ever be foolish enough to expect a renewal of his love? Is there one among the sex, who would not protest against such a weakness as a second proposal to the same woman? There is no indignity so abhorrent to their feelings!”

She was a little revived, however, by his bringing back his coffee cup himself; and she seized the opportunity of saying,

“Is your sister at Pemberley still?”

“Yes, she will remain there till Christmas.”

“And quite alone? Have all her friends left her?”

“Mrs. Annesley is with her. The others have been gone on to Scarborough, these three weeks.” She could think of nothing more to say; but if he wished to converse with her, he might have better success. He stood by her, however, for some minutes, in silence; and, at last, on the young lady’s whispering to Elizabeth again, he walked away.

(Volume 3, Chapter 12)

(My coffee cup in this photo is actually a Glühwein mug from the Bonner Weihnachtsmarkt, which is where Bethie and I celebrated Jane Austen’s birthday last year, near the statue of Beethoven in the Münsterplatz.)

Speaking of frigates and books and memorials, I also want to share with you a splendid memorial tribute to Lieutenant Commander Francis Austen RN (1924 – 2023): Remembering Jane Austen’s Great Great Nephew, written by my friend Sheila Johnson Kindred. I have fond memories of meeting Francis Austen at the Jane Austen Society of the UK conference here in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 2005. Sheila outlines his naval career, which included serving as a midshipman and later as a sub-lieutenant in the frigate HMS Kent in 1943-44.

Francis’s grandfather, Lieutenant Herbert Grey Austen RN, made several sketches of Halifax Harbour when he was stationed here in the 1840s, one of which appears on the cover of Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, a collection of essays from the 2005 conference.

Sheila writes that Francis Austen was “genial, empathetic and had the gift of making people feel welcome.” He “talked engagingly about Jane Austen and her family. Particularly memorable were his stories about the French Revolutionary War and the Napoleonic Wars as they affected the careers of his ancestor, Admiral Francis, and the Admiral’s younger naval brother, Charles (1779 – 1852), who had also served on the North American Station from 1805 – 1811.”

If you’re interested, you can find out more about Jane’s brothers Francis and Charles and their families and their time on the North American Station in the walking tour Sheila and I created for the 2017 Jane Austen Society of the UK conference, which was also held here in Halifax: Austens in Halifax.

(I seem to have an endless collection of scarves; this stunning yellow scarf was a gift from another member of the Austen family at the 2017 conference.)

More of Brenda Barry’s photos from the Historic Gardens:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

December 15, 2023

“Where to look for the threads”

I’ve been reading Eudora Welty recently. I started with One Writer’s Beginnings, which was a present from my sister Bethie, and I loved it so much that I immediately ordered her collected stories and essays. Reading Welty’s memoir and L.M. Montgomery’s The Golden Road around the same time made it possible to see links between the two writers that I might otherwise have missed.

Welty says, “Writing fiction has developed in me an abiding respect for the unknown in a human lifetime and a sense of where to look for the threads, how to follow, how to connect, find in the thick of the tangle what clear line persists. The strands are all there: to the memory nothing is ever really lost.”

These lines prompted me to return to the last pages of The Golden Road, in which the Story Girl’s father speaks of his love for her late mother: “How I loved her! How happy we were! But he who accepts human love must bind it to his soul with pain, and she is not lost to me. Nothing is ever really lost to us as long as we remember it.”

I chose this turquoise scarf for the background not just because it matches the cover of the book, but because I bought it in Boston the summer I was fourteen, when I was on my way to Welty’s hometown of Jackson, Mississippi, to spend a week volunteering for a charity similar to Habitat for Humanity.

I thought of the Story Girl’s love of roads when I read Welty’s account of travelling with her parents, with her mother giving directions while her father drove: “‘This doesn’t surprise me at all,’ she’d say as Daddy backed up a mile or so into our own dust on a road that had petered out. ‘I could’ve told you a road that looked like that had little intention of going anywhere.’”

Do you remember the discussion of fairyland in The Story Girl? Bev, the narrator, says the Story Girl is right that fairyland exists, but only children know how to get there, and when they get older they forget—except for “singers and poets and artists and story-tellers.”

Welty writes that “Children, like animals, use all their sense to discover the world. Then artists come along and discover it the same way, all over again. Here and there, it’s the same world. Or now and then we’ll hear from an artist who’s never lost it.”

I hadn’t known before that Welty worked as a photographer in the 1930s, taking pictures of daily life in Mississippi. I enjoyed reading her description of what she learned from photography:

I learned in the doing how ready I had to be. Life doesn’t hold still. A good snapshot stopped a moment from running away. Photography taught me that to be able to capture transience, by being ready to click the shutter at the crucial moment, was the greatest need I had. Making pictures of people in all sorts of situations, I learned that every feeling waits upon its gesture; and I had to be prepared to recognize this moment when I saw it. These were things a story writer needed to know. And I felt the need to hold transient life in words—there’s so much more of life that only words can convey—strongly enough to last me as long as I lived. The direction my mind took was a writer’s direction from the start, not a photographer’s, or a recorder’s.

I recently read an article about Alice Munro in The Guardian in which Chris Power suggests that Welty is “a particularly discernible influence” on Munro: “both writers are fascinated by the doubling of the world as it’s generally seen, and the stranger one it cloaks.”

In both writing and photography, Welty spoke of “trying to portray what you saw, and truthfully. Portray life, living people, as you saw them. And a camera could catch that fleeting moment, which is what a short story, in all its depth, tries to do.” This New York Times article includes some of the photographs she took during the Depression, of tomato packers, farmers, a nurse, a Sunday School class, and a blind weaver. My sister Bethie is especially interested in that last one, “The weaving woman and the blind bard in one image. She has fused together Penelope and Homer, but in a local, contemporary, humble context.”

Natasha Trethewey’s beautiful introduction to One Writer’s Beginnings inspired me to look up some of her work as well. I like what she says in the introduction about how “Whether or not we are writers, we tell a story to ourselves about our lives, the art of them—what gives meaning and purpose, and connects us to others.”

I’ve said One Writer’s Beginnings was a present from Bethie. Let me go back and tell the story of how she came to give me this wonderful book. If you’ve been reading my blog over the past year, you’ll probably remember that Bethie was living in Bonn, Germany, and I travelled there to visit her and her family (and the Beethoven statue, and the house where he was born, and Cologne Cathedral, and the ruined castle at Drachenfels, among other places). Last December, in a lovely bookstore in Bonn called Thalia, I bought a copy of Ann Patchett’s recent collection of essays, These Precious Days, to read on the flight home to Nova Scotia.

The bookstore, Thalia, is in the Marktplatz, inside a former theatre (Metropol)

This past summer, Bethie and her family moved from Germany to Mississippi, and when they stopped in Nova Scotia for a couple of weeks on their way to their new home, I gave her my copy of These Precious Days, thinking it would provide good company because many of the essays are about life in the South. (Someday, Bethie and I would love to visit Ann Patchett’s bookstore, Parnassus Books, in Nashville.) In the fall, when Bethie was looking for a book to send me, she settled on something by Welty, because she had read Patchett’s introduction to Welty’s Collected Stories, which is included in These Precious Days. She bought One Writer’s Beginnings for me and the Collected Stories for herself.

The blue scarf is from Beethoven’s House in Bonn

Patchett quotes Welty’s description of what it was like to discover Virginia Woolf, in 1930, “when I was young,” Welty says, “reading at my own will and as pleasure led me.” She read To the Lighthouse: “I fell upon the novel that once and forever opened the door of imaginative fiction for me, and read it cold, in all its wonder and magnitude.” Patchett encourages readers to reread Welty’s stories even if they’ve read them before, “because even as the text stays completely true to the writer’s intention, we readers never cease to change.” She praises Welty’s ability to “tell the truth of the landscape.” She says she could take the volume of stories apart “and type it up again, sentence by perfect sentence, to say, This is exactly what Mississippi is like.”

When Bethie first arrived in Mississippi, she was missing Beethoven, and the tradition of going for “coffee with Beethoven” in the Münsterplatz in Bonn. Maybe Welty is the new Beethoven? Or Elvis is the new Beethoven?? I’d like to see his birthplace in Tupelo. I haven’t been to Mississippi since I was fourteen, and I’m looking forward to making the trip, perhaps sometime in the coming year.

Bethie took this picture of me in May, the last time the two of us had coffee with Beethoven

I’d like to visit Eudora Welty’s house, at 1119 Pinehurst Street in Jackson, where she lived for almost eighty years. I was delighted to discover a reference to the house in the recent New Yorker profile of Kate DiCamillo, by Casey Cep. I had read this fascinating article when it was published in September—a rare example of me reading the New Yorker right away, rather than letting issues pile up for months before I start trying to catch up—but I hadn’t paid much attention to the part about Welty’s house because I hadn’t yet read One Writer’s Beginnings. Happily, my friend Lisa mentioned the article in November, and I read it again.

Here’s what Cep says about DiCamillo: “The closest thing to luxury in her house is two pairs of slippers: one under her desk, the other under her claw-foot tub. During a tour of Eudora Welty’s home, in Jackson, Mississippi, she was struck by the humanity of the novelist’s slippers, which were still waiting faithfully under her bathrobe long after her death. DiCamillo talked about them so much that her best childhood friend, Tracey Bailey, got her one pair, and her best writing friend, the author Ann Patchett, got her another.”

I’m still meditating on what Welty says about looking for the threads, “how to follow, how to connect.”

Some years ago, my daughter and I read Finding Serendipity, by Angelica Banks, in which the heroine, Tuesday McGillycuddy, follows a silver thread that leads her to the place stories come from. I like the idea of holding onto a thread that can help us return to the world of the imagination, if we’ve lost our way, or if the road we’re on turns out to be one that has “little intention of going anywhere.”

After we had read the book, I bought spools of silver thread for Bethie and my daughter and me. I keep mine on my desk, in a little dish filled with shells, stones, and sea glass, a letterpress S that a friend gave me years ago, and a ring I lost while swimming in the Atlantic Ocean when I was a child, which my Granny later found for me in a clump of seaweed after the tide had gone out.

I’m mixing metaphors by talking about threads and roads at the same time. But if these metaphors help us find our way to the next story, whether it’s the next book we read or the next book we write or the next story we tell each other or ourselves, then I’m in favour of keeping them both, along with the ring and the letter and the treasures from the sea.

After I had read One Writer’s Beginnings, I followed the thread, or the road, to Natasha Trethewey’s Native Guard: Poems, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2006. In “The Southern Crescent,” I read about her mother “leaving behind / the dirt roads of Mississippi” in 1959, “the film / of red dust around her ankles, the thin / whistle of wind through the floorboards / of the shotgun house, the very idea of home.” I read about her parents’ marriage in 1965 in “Miscegenation”:

A year later they moved to Canada, followed a route the same

as slaves, the train slicing the white glaze of winter, leaving Mississippi.

I read about her grief for her mother, who was murdered by her second husband. In “Myth,” Trethewey talks about “still trying / not to let go.” I thought of the Story Girl’s lament in The Golden Road for Paddy, the missing cat: “every night I dream that he has come home,” she says, “and when I wake up and find it’s only a dream it just breaks my heart.” Trethewey addresses her mother: “You’ll be dead again tomorrow, / but in dreams you live. So I try taking / you back into morning.”

When Trethewey was appointed poet laureate in 2012, she that when she learned of her mother’s death, “Strangely enough, that was the moment when I both felt that I would become a poet and then immediately afterward felt that I would not. I turned to poetry to make sense of what had happened. … It took me nearly 20 years to find the right language, to write poems that were successful enough to explain my own feelings to me and that might also be meaningful to others.”

Like Trethewey, DiCamillo has a deep knowledge of suffering and grief. Cep writes that “One gets the sense from the books that DiCamillo knows that ‘deeper dark’ better than most of us, but she has, in the past, avoided letting on just how well.” Only recently has she spoken of terrifying scenes from her childhood, images of her father that are “darkened by fear,” and of how she made peace “with the torment she hadn’t wanted but without which she worries she would not have become a writer.”

I’ve read some of DiCamillo’s books, including The Tale of Despereaux and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane, but I hadn’t read her first novel, Because of Winn-Dixie, and I started it a few days ago after my friend Susan recommended it. I’d also like to read Great Joy, a Christmas picture book that comes highly recommended by my friend Lisa. Ann Patchett writes about DiCamillo as well as Welty in These Precious Days; her favourite of all DiCamillo’s books is The Magician’s Elephant. She writes that the books “had given me the means to look backwards. … The work of Kate DiCamillo had opened something in me, an ability to see and feel things that were very far from me now.”

Let’s go back to Welty and Montgomery for a moment, who both say that “nothing is ever really lost.” Patchett says that what DiCamillo’s books gave her was “the ability to walk through the door where everything I thought had been lost was in fact waiting for me. All of it. The trick was being brave enough to look.”

When I read about DiCamillo’s writing habits in the early years when she was also working for a wholesale book distributor, I thought again of Montgomery. DiCamillo used to “get up every day to write before her shift—first an hour early, then two hours early, at 4:30am, setting herself the task of producing two pages a day. She chose the predawn hours because neither the rest of the world nor her inner critic was awake yet. Sitting at a desk that her brother helped fashion out of a wooden fence from their back yard in Clermont, she wrote by candlelight and lamplight. She submitted short stories to every magazine for which she could find an address, including this one, and she kept submitting them long after others would have called it quits.”

In her autobiography, The Alpine Path, Montgomery describes one winter when she was teaching and felt too tired to write in the evenings. “So I religiously arose an hour earlier in the mornings for that purpose. For five months I got up at six o’clock and dressed by lamplight. The fires would not yet be on, of course, and the house would be very cold. But I would put on a heavy coat, sit on my feet to keep them from freezing and with fingers so cramped that I could scarcely hold the pen, I would write my ‘stunt’ for the day. Sometimes it would be a poem in which I would carol blithely of blue skies and rippling brooks and flowery meads! Then I would thaw out my hands, eat breakfast and go to school.”

I suspect there’s a connection between this habit Montgomery developed, of being able to write about warmth and sunshine while working in a cold house, and her ability to write cheerful stories while enduring periods of disappointment and unhappiness. She dealt with many losses in her life, beginning with the death of her mother in 1876, when Maud was just twenty-one months old. As Mary Henley Rubio says in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, Montgomery later wrote in her journal that “three simple words had fortified and sustained her throughout a troubled life.” One night when she was sleeping at her cousin Pensie Macneill’s house, Pensie’s mother came into the room to check on the girls, bent over them, and said the words “Dear little children.” Maud was pretending to be asleep, but she never forgot these kind words that were so unlike the things her “stern Grandfather” and “reserved Grandmother” said to her.

Trethewey, DiCamillo, and Montgomery have all spoken about the way difficult or traumatic experiences shaped their writing. By contrast, Welty says in One Writer’s Beginnings that she was “a writer who came of a sheltered life.” However, she says that “A sheltered life can be a daring life as well. For all serious daring starts from within.”

A couple of photos my husband took on his trip to Mississippi in November:

William Faulkner’s house, Rowan Oak

Well. I’ve written at length and I’m not at all sure I’ve found the “clear line” Welty talks about, but it feels important to follow the threads and make connections. To keep reading and talking about books, no matter how thick the “tangle” of the world we live in.

If you haven’t yet read One Writer’s Beginnings, I encourage you to seek it out. Read it for the description of Welty’s parents “whistling back and forth to each other up and down the stairwell,” when her father was upstairs “shaving in the bathroom and Mother downstairs was frying the bacon.” “Long before I wrote stories,” she says, “I listened for stories. Listening for them is something more acute than listening to them.” Read for the moment at which she was startled and disappointed “to find out that story books had been written by people, that books were not natural wonders, coming up of themselves like grass.” Read for the story of how as a child she made her way through the State Capitol to the library where the librarian allowed patrons to take out only two books at a time, and young Eudora knew the “bliss” of “the devouring wish to read,” and “The only fear was that of books coming to an end.”

I’ve dipped into Suzanne Marrs’s biography of Welty, and I’m intrigued by the range of responses to One Writer’s Beginnings: while many reviewers wrote of Welty as “shy and retiring,” saying (in the words of one critic) that she led “a relatively uneventful life,” later critics have drawn attention to the complexities of her life, beyond the image of her as the “happy child” of this memoir or as the “witty, elderly lady.” Perhaps her life was not as “sheltered” as she said it was. I’d like to read more.

I’m immersed in Welty’s essays now, and I was delighted to find that the first essay in The Eye of the Story is called “The Radiance of Jane Austen”: “The sheer velocity of the novels, scene to scene, conversation to conversation, tears to laughter, concert to picnic to dance, is something equivalent to a pulsebeat. The clamorous griefs and joys are all giving voice to the tireless relish of life. The novels’ vitality is irresistible for us. … Everybody doing everything together—what mastery she has over the scene, the family scene!”

I’m interested in reading more books by Mississippi writers, starting with Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing. I’d also like to read more by Kiese Laymon, whom I quoted in last week’s post—“READ when you’re angry”—and whose essay on gas station restaurants I enjoyed reading earlier this week. He says, “I’d never really thought about the fact that my favorite restaurants, as a child, as a teenager, as an adult returning to Mississippi, nearly all served gas. And I never, ever thought of them as gas stations that served food.” I’d be glad to hear other recommendations.

Many thanks to my dear sister Bethie for the gift of One Writer’s Beginnings. She told me recently that she had just finished reading Elizabeth Hay’s Late Nights on Air, “which I loved,” she said. Hay’s novel won the Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2007. “I guess it took me a while to get to it,” Bethie says, “but it somehow came into my hands at just the right moment. Having just moved to the deep South, I found Hay’s writing about the far North extraordinarily refreshing. Here’s to all the books waiting on shelves, in piles (or boxes), and on lists!”

I too loved Late Nights on Air, and Hay’s memoir All Things Consoled. I haven’t yet read her novel Garbo Laughs, which was honoured with a Project Bookmark Canada Bookmark in Ottawa, Ontario (you can see photos of the Bookmark plaque here) and since I’m a long-time supporter of Project Bookmark, I’ll follow the thread and add the novel to my list.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

December 8, 2023

Prudence and Romance in the “Golden Crescent”: Uzma Jalaluddin’s Much Ado About Nada (plus some scrapbook notes and photos)

Uzma Jalaluddin’s novel Much Ado About Nada was inspired by Jane Austen’s Persuasion as well as (more obviously) by Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing. I enjoyed reading scenes set on the University of Toronto campus and in the fictional Golden Crescent neighbourhood of Scarborough, Ontario, and watching the complicated relationship between Nada Syed and Baz Haq unfold. In chapters set in the present, they meet at Deen&Dunya, “a massive Muslim convention held in downtown Toronto” that’s “like Comic-Con, except with hijabs, jilbabs, beards, and kufi skullcaps rather than intricate fan-created costumes.” Nada has managed to avoid attending the convention—and seeing Baz—for six years, but when she reluctantly agrees to accompany her best friend, Haleema, she’s forced to confront Baz and thus also the secrets she’s kept for so long. In chapters set in the past, we learn about their history as adversaries and then friends, and about the romance that developed and the reasons they, like Austen’s Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth, said goodbye despite the strong bond between them.

I took this photo of the University of Toronto campus and downtown Toronto last summer,

when my daughter and I visited the CN Tower.

Both Persuasion and Much Ado About Nothing are central to the novel. “Nada means nothing,” a childhood classmate and bully tells Nada. “You’re nothing,” he says (Chapter 3). Anne Elliot, despite her “elegance of mind and sweetness of character,” is “nobody with either father or sister; her word had no weight, her convenience was always to give way—she was only Anne” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). The spirited arguments between Nada and Baz echo those of Shakespeare’s Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado or Austen’s Elizabeth and Darcy. Unlike Anne Elliot, however, who consistently responds to dismissive remarks from her family with patience and generosity, after Nada is bullied as a child, she acts as a bully toward Baz, and later gives in to the temptation to snoop in his notebook, where she finds poetry and a sketch of herself and begins to suspect his interest in her goes beyond friendship. It isn’t just the interference of a Lady Russell-like family friend that keeps the heroine and her hero apart, it’s also their own mistakes that prevent them from fully understanding each other. Although Nada apologizes, Baz refuses to forgive her and he disappears from her life yet again.

Like Wentworth, Baz criticizes those who are indecisive. “Let those who would be happy be firm,” Baz says (Chapter 14), echoing Wentworth’s precise words to Louisa Musgrove. But Jalaluddin isn’t just copying plot or dialogue from Persuasion. Here, as elsewhere in the novel, she offers a fresh perspective on the tensions between hero and heroine. In Persuasion, Anne overhears Wentworth’s conversation with Louisa; in Much Ado About Nada, Nada is present when Baz delivers this line, and thus she has the opportunity to respond to him and Firdous, the woman who, like Louisa, has boasted that when she’s made up her mind about something, she doesn’t change. Nada argues that “Seeking naseeha, sincere advice, and listening to people you trust when you’re unsure is natural.” Anne, by contrast, remains silent, and even immobile: “Her own emotions still kept her fixed. She had much to recover from, before she could move” (Volume 1, Chapter 10).

This isn’t the only situation in which Jalaluddin transforms a private moment from Persuasion into a more public one in her novel—but I won’t spoil the ending by describing the clever way she incorporates Wentworth’s famous “half agony, half hope” letter in her own work. Instead, I’ll end with her version of the line in Persuasion that Jane’s sister Cassandra said “deserves to be written in letters of gold.” Austen says of her heroine that “She had been forced into prudence in her youth, she learned romance as she grew older—the natural sequel of an unnatural beginning” (Volume 1, Chapter 4). Jalaluddin says of Nada that “Perhaps the prudence she had been forced into as a twenty-two-year-old could be shed, if only for one night, in favor of a more romantic memory” (Chapter 30). Readers may hope, with Nada, that the romance will last as she grows older, too.

More photos from the University of Toronto campus:

I was delighted to learn that Jalaluddin’s most memorable childhood reading experience was of reading Anne of the Island when she was “maybe 10 years old and home sick with the flu. I lay on the couch and devoured that book,” she says, “only realizing when I was done that it was the third in a series! L.M. Montgomery is now one of my all-time favourite authors.” Most readers encounter Anne of Green Gables first, and then go on to explore the later books in the series; I don’t know if I’ve come across other examples of readers who’ve discovered Anne as an older character first. I’m now trying to imagine what it would be like to meet Anne for the first time as a student at Redmond College, instead of as an eleven-year-old “girl—a strange girl—an orphan girl” at the Bright River train station.

I loved Much Ado About Nada as much as (or possibly even more than) Jalaluddin’s Ayesha at Last (which I wrote about in a blog post earlier this year), and I’m now keen to read Hana Khan Carries On. I found myself completely caught up in the richly detailed fictional world she created, eager to find out what would happen next for Nada and the other characters. Jalaluddin’s newest book, co-authored with Marissa Stapley, is Three Holidays and a Wedding.

Since I’ve been talking about the University of Toronto in this post, I also want to share a link to this essay on “The Novel and the Museum,” by Kerry Clare, whose most recent novel is Asking for a Friend. She describes the view of the Royal Ontario Museum from the residence she lived in when she was a student at the University of Toronto in the late 1990s. “Every night,” she says, the sun went down behind the museum, “a little earlier than it might have if we’d had a less magnificent neighbour.”

My daughter and I visited the Royal Ontario Museum in August:

Kerry writes that “It’s a weird thing to raise your children around the same neighbourhoods where you spent your formative—and perhaps most nonsensical years, to push a stroller along that very same block where I once worked at Pizza Hut, all brand new condos now.” Although she didn’t visit the museum when she was a student, she has a membership now and she takes her children there to explore “hands-on galleries and dinosaur bones.” Walking or driving on the same streets twenty-five years later, she wonders, “am I haunting the places I used to know or are the places haunting me?”

I sometimes wonder the same thing, as I now live in the neighbourhood where I grew up, near my old school, and the church where I was baptized, and a different church where I went to Brownies and Girl Guides. If I were living further away, would I think of scenes from my childhood as often as I do? Every time I pass my old school, for example, I can see myself in the schoolyard when I was seven years old, and at the same time, I can also see the students from my grade nine class, lined up on the steps at the front entrance for our graduation portrait. I can feel the satin and lace of the dress I wore that day, which had belonged to my grandmother in the 1940s, and which my mother had altered so it would fit me. We dyed it, aiming for a deep navy, but it ended up being more like periwinkle blue. (It has since faded, and is now a shade of lavender.) How often would I think of that portrait and those friends and classmates and that dress, I wonder, or the graduation dance in the church basement across the street from the school, if we hadn’t left Boston to move back home to Halifax?

Kerry quotes Virginia Woolf on “the masculine values that prevail”: “This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing-room. A scene in a battle-field is more important than a scene in a shop—everywhere and much more subtly the difference of value persists” (A Room of One’s Own). In Asking for a Friend, Kerry writes about women’s friendships, and the questions of “What lasts? What survives?” “Women’s stories matter,” she says, “but for too long such stories have been lost to history, absent from the archives, missing from the museum.” “The feelings of women in a drawing room,” Kerry says again—“that’s a book I want to read, and this is the book I wanted to write.”

There are a few more things I want to share with you this week. First, some of you might be interested in a special online panel discussion about Emily Carr, Jane Austen, and L.M. Montgomery, on December 13th. It’s called “House to House,” and you can register on the Emily Carr House website.

Last week, when I wrote about birthday “coincidences,” I hadn’t realized that Carr’s birthday (Dec. 13th) is so close to Montgomery’s (Nov. 30th) and Austen’s (Dec. 16th).

My friend Kate Scarth, Chair of L.M. Montgomery Studies at the University of Prince Edward Island, told me a few days ago about the new Anne of Green Gables audiobook directed by Megan Follows, who played Anne in the 1995 miniseries adaptation of the novel. Follows says she spoke with the cast about how Anne was revolutionary—“to have an imagination, to have feeling, to express feelings, and for girls to express anger.”

Next, some photos I took recently near Windsor, Nova Scotia: