Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 13

November 24, 2023

“I always supposed everyone thought in colours” #ReadingStoryGirl

Cecily is “a sweet pink,” like a mayflower, Sara Ray is “very pale blue,” Dan is red, Peter and Felix are yellow, and “Bev is striped”—and “you needn’t laugh,” says the Story Girl in L.M. Montgomery’s novel The Golden Road, because “It isn’t he that is striped. It’s just the thought of him.” Felicity has never heard of synesthesia—(not that the Story Girl uses that term when she describes the link between thoughts and colours) and she doesn’t believe it exists: “I believe you are just making that up,” she says (Chapter 12).

“Indeed I’m not,” replies the Story Girl. “Why, I always supposed everyone thought in colours. It must be very tiresome if you don’t.” She says, “There are times when I can’t think anything but grey thoughts. Then, other days, I think pink and blue and gold and purple and rainbow thoughts all the time.”

(This is part four in a series of posts about The Story Girl and The Golden Road. Naomi MacKinnon and I are hosting a readalong this month and we’re delighted to have your company! We hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments on her blog and mine, and if you write your own posts about the novel online, please share the links with us. Here are the links to my first, second, and third posts in the series, and to Naomi’s post on The Story Girl.)

I thought of the Story Girl’s words about colours again a little later in the novel, when Montgomery describes the beauties of the landscape in Prince Edward Island in June. In this passage, she doesn’t mention colours aside from that of the metaphorical golden road, and yet even so, I find her writing brings the scene to life in full colour.

“Cecily declared she hated to go to sleep for fear she might miss something. There were so many dear delights along the golden road to give us pleasure—the earth dappled with new blossom, the dance of shadows in the fields, the rustling, rain-wet ways of the woods, the faint fragrance in the meadow lanes, liltings of birds and croon of bees in the old orchard, wind pipings on the hills, sunset behind the pines, limpid dews filling primrose cups, crescent moons through darkling boughs, soft nights alight with blinking stars” (Chapter 15).

I can see the rich red soil of PEI, the green fields and forests, pale blue forget-me-nots in Lovers’ Lane, and bees and sunsets and primroses (and wild roses, too) and bright stars against the dark sky.

My daughter and me at Stanhope Beach, PEI, on an evening in June several years ago

Like Anne Shirley, and like L.M. Montgomery herself, the Story Girl loves springtime. “I wonder what it would be like to live in a world where it was always June,” Anne muses in Anne of the Island.

“What would it be like to live in a world where it is always June?” Montgomery had written in a journal entry at the end of June in 1902, thirteen years before Anne of the Island was published. She had been for a walk in Lovers’ Lane, where she felt grateful for the healing effects of nature. “Somewhere in me the soul of me rose up and said, ‘No matter for those troubles and problems that looked so big and black in the night. They are mortal and will pass. I am immortal and will remain.’”

“It’s so nice to be alive in the spring,” the Story Girl says one evening at twilight as the children “swung on the boughs of Uncle Stephen’s walk” (Chapter 10). Felicity responds, “complacently,” that “It’s nice to be alive any time,” and the Story Girl insists, “But it’s nicer in the spring.” She speaks of the soul that Montgomery sees as immortal: “When I’m dead,” says the Story Girl, “I think I’ll feel dead all the rest of the year, but when spring comes I’m sure I’ll feel like getting up and being alive again.”

In The Golden Road, the children must face the death of the beloved cat Paddy, and they plan a proper funeral “since Paddy was no common cat,” and “Many human beings have gone to their graves unattended by as much real regret as followed that one grey pussy cat to his” (Chapter 29). We don’t see the deaths of any of the children themselves, but we do learn from Bev that although most of them will go on to lead long lives, “there was no earthly future for our sweet Cecily” (Chapter 30). The Story Girl tells fortunes for all the others, giving details about careers and marriages and even about changes in political allegiances—“Catch me ever voting Grit!” objects Dan when he hears his fortune—but she at first refuses to tell Cecily’s. Eventually, she offers that “Everybody you meet will love you as long as you live,” and Bev wonders if the Story Girl had “some strange gleam of foreknowledge” that Cecily would never “leave the golden road” of youth.

I enjoyed reading the Story Girl’s remarks about storytelling. “I am not telling you what Ursula Townley ought to have done,” she says to her audience at one point. “I am only telling you what she did do. If you don’t want to hear it you needn’t listen, of course. There wouldn’t be many stories to tell if nobody ever did anything she shouldn’t do” (Chapter 2).

Another example: “‘I shall try not to be vexed when people interrupt me when I’m telling stories,’ wrote the Story Girl, ‘but it will be hard,’ she added with a sigh” (Chapter 4). As I mentioned in last week’s post, during the writing of The Golden Road Montgomery was “all the time nervously expecting some interruption—which all too surely came nine times out of ten. Under such circumstances there is very little pleasure in writing.” She wrote in her journal that she often thought of the time she had spent writing in her old room at her grandparents’ house in PEI, “But those days are gone and cannot return as long as wee Chester [her son] is a small make-trouble. I do not wish them back—but I would like some undisturbed hours for writing” (May 21, 1913).

When Paddy is missing, the Story Girl says she can’t bear the uncertainty of not knowing: “If I just knew what had happened to him it wouldn’t be quite so hard” (Chapter 10). Later in the novel, however, when Sara Ray says she “hates things with mysteries” because “They always make me nervous,” the Story Girl says, “I love them. They’re so exciting” (Chapter 24). In this case, they’re discussing the mysterious locked room in the Awkward Man’s house. Years later, Sara Stanley sends Bev the story of the romance between Jasper Dale and Alice Reade.

I don’t remember if I found this story romantic when I read it as a child. This time around, I found it unnerving. Jasper Dale “shadowed forth to himself the vision of a woman, loving and beloved; he cherished it until it became almost as real to him as his own personality and he gave this dream woman the name he liked best—Alice” (Chapter 25). He doesn’t just dream of her, he buys a portrait that resembles her, sets up a secret room in his house for her, buys books he thinks she’d like, along with a sewing basket and “a pale blue tea-gown” and satin slippers, and keeps the room “sweet with fresh flowers.” In the “purple summer evenings” he sits in the room and talks to her or reads from his favourite books. (Isn’t it interesting that although he’s chosen books with this imaginary woman’s taste in mind, when he reads aloud to her, he chooses his own favourites?) I thought of Barney Snaith in Montgomery’s novel The Blue Castle, who also keeps a secret (fiction) in a locked room.

It seems as if Jasper Dale is dreaming of the woman he hopes to meet someday. But the Story Girl says clearly that in imagining her, “he turned to this ideal kingdom for all he believed the real world could never give him.” One friend who’s reading The Golden Road with us this month told me she wondered if he was furnishing the room and buying the dress and slippers not for “Alice” but for himself—for a version of himself that he couldn’t share with others in that particular time and place. What do you think?

When Alice Reade comes to teach music in Carlisle and Jasper Dale catches sight of her, he believes “his dream love had taken visible form before him.” Instead of taking bouquets into the secret room, he begins to leave flowers under the pine tree, where the real Alice will find them, and one day, Miss Reade overhears him confessing his love for her and his wish that she will someday be his wife. She responds instantly with a confession of her own love for him, and the story ends with him kissing her.

The Story Girl says “Miss Reade is perfectly happy” at the prospect of getting married (Chapter 24). But I share Felicity’s skepticism: “All I can make out is that Miss Reade is going to marry Jasper Dale, and I don’t like the idea one bit.” We know very little about her, or her dreams and ambitions: she seems to have appeared simply as the embodiment of Jasper Dale’s vision. Like the “one face” that “looks out from all his canvases” in Christina Rossetti’s poem “In an Artist’s Studio,” Alice Reade is “A saint, an angel—every canvas means / The same one meaning, neither more nor less.” Jasper Dale, like the artist, “feeds upon her face by day and night, / And she with true kind eyes looks back on him.”

“I loved you long before I saw you,” Jasper says to his Alice after she has confessed her love. I can’t help but think, however, that like the artist in Rossetti’s poem, he loves her “Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.”

There’s so much more I could say about this novel, but I’ve already written at length, so I think I’ll stop here. Please feel free to chime in about other topics in the comments—Peg Bowen, for example, or the three absent fathers who all return near the end of the novel. It’s been a real pleasure to reread and write about The Story Girl and The Golden Road this month, and I’m grateful to everyone who’s joined us.

L.M. Montgomery’s birthday is coming up on Thursday, November 30th, and I’ll be back with an extra post that day. In early December, I think I’ll write about some Jane Austen-inspired novels, and then I’ll turn to LMM again, with a post on Emily of New Moon, in honour of the novel’s 100th birthday.

On a different topic, I want to add a note here about a book launch this evening, for The Broadview Anthology of Medieval Arthurian Literature, edited by my friends Kathy Cawsey (who wrote a guest post on L.M. Montgomery’s Jane of Lantern Hill for my blog in the spring) and Elizabeth Edwards. Here’s what Michael W. Twomey of Ithaca College says about the book: “Going beyond the canonical Latin, French, and English texts that established the characters and narratives collected in Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur, BAMAL adds texts from Welsh, Hebrew, Norse, Dutch, German, and Greek, plus a collection of visual images, all of which make it a unique collection. More than any previous anthology, BAMAL shows the diversity and vitality of medieval Arthurian literature.”

The launch is at the King’s College Library in Halifax, Nova Scotia, tonight at 7pm. Congrats, Kathy and Elizabeth!

Previous posts about The Story Girl and/or The Golden Road

On my blog:

An Invitation to Read The Story Girl and The Golden Road

An Necklace of Expressive Words

“The best piece of work I have yet done” #ReadingStoryGirl

“This old blue chest holds a tragedy” #ReadingStoryGirl

“The Golden Road of Youth” #ReadingStoryGirl

On Naomi’s blog, Consumed By Ink:

The Story Girl Readalong #ReadingStoryGirl

#ReadingStoryGirl: “There is such a place as fairyland—but only children can find the way to it…”

On Buried in Print:

November 2023, In My Bookbag (also, L.M. Montgomery)

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Arriving in PEI on the ferry on a warm June day:

PEI lupines, on the day of the unveiling of the L.M. Montgomery Project Bookmark Canada plaque in Cavendish (June 24, 2018):

November 17, 2023

“The Golden Road of Youth” #ReadingStoryGirl

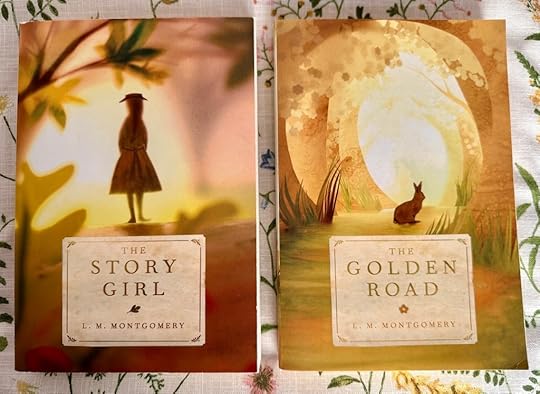

Like Anne of Green Gables, Sara Stanley—the Story Girl—is drawn to roads, with their twists and turns and the mysteries of where they will lead us. Anne Shirley famously speaks of “the bend in the road” in the last chapter of Anne of Green Gables, and of her fascination with how “the road beyond it goes—what there is of green glory and soft, checkered light and shadows—what new landscapes—what new beauties—what curves and hills and valleys further on” (Chapter 38). The Story Girl begins with Sara Stanley’s announcement that “I do like a road, because you can be always wondering what is at the end of it.”

In The Golden Road, L.M. Montgomery continues the story of the Story Girl and her band of friends, and makes clear in the foreword to the novel that in this case, the road is not one that leads into the future. Instead it is “the golden road of youth” that we all walked on, “once upon a time.” It’s a road we leave behind, yet Montgomery suggests that we can still find our way to that world through memory, and through stories.

(This is part three in a series of posts about The Story Girl and The Golden Road. Naomi MacKinnon and I are hosting a readalong this month and we’re delighted to have your company! We hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments on her blog and mine, and if you write your own posts about the novel online, please share the links with us. Here are the links to my first and second posts in the series.)

I experienced some trepidation when I started rereading The Golden Road, because I remembered the scene in The Story Girl in which Sara Stanley chastises Sara Ray for wanting to know what happens after the ending of a story. “You’re never satisfied to leave a story where it should stop, Sara Ray,” she says (Chapter 21). Should the story of The Story Girl and her companions have stopped at the end of that novel? Or was there enough material to warrant a sequel? These questions made me wonder the same thing about the “Anne” books. I wonder what Montgomery might have written if she hadn’t felt such tremendous pressure to keep writing sequels, and to write them quickly.

I liked the elegiac tone of the ending of The Story Girl, with its lament for the beautiful summer that has ended, and its celebration of “the pleasure of bird song, of silver rain on greening fields, of storm among the trees, of blossoming meadows.” But when I opened The Golden Road and read the Foreword (by Montgomery herself? or is this in Bev’s voice?), I found the tone almost unbearably sentimental. “Life was a rose-lipped comrade with purple flowers dripping from her fingers” is just one example of the excesses here.

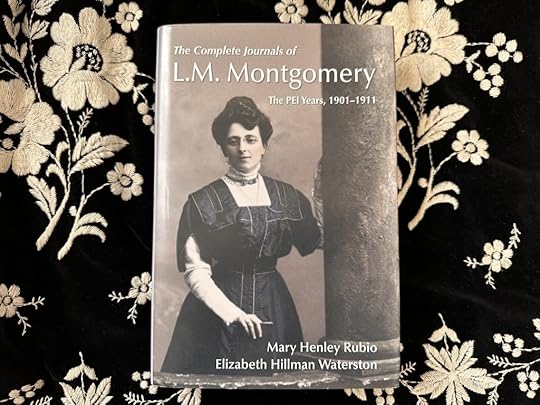

I enjoyed reading about what was happening in Montgomery’s life while she was composing The Golden Road. In fact, I discovered that I enjoyed reading about the context more than I enjoyed reading these two novels. Just as I did earlier this month when I was reading The Story Girl, I turned to Elizabeth Waterston’s Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery, Mary Henley Rubio’s biography, Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, and Montgomery’s journals, edited by Waterston and Rubio.

There’s a huge contrast between what was happening in Montgomery’s life during the composition of The Story Girl and during the composition of The Golden Road. When she wrote the former, she was preparing to leave PEI. By the time she began the latter on April 30, 1912 she had, in Waterston’s words, “entered her own ‘sequel’”: she had “left the idyllic isle and moved to the Upper Canada village life of Leaskdale.” She had married Reverend Ewan Macdonald in July of 1911, they had moved to Ontario, and soon she was expecting her first child. The book she published in between The Story Girl and The Golden Road, a collection of stories called Chronicles of Avonlea, appeared in print in June, 1912.

Although Montgomery felt she had made a mistake in marrying Ewan—she described her wedding day as a time when “I was as unhappy as I had ever been in my life” (January 28, 1912)—she delighted in the birth of her son Chester. He was born in July of 1912, and at the end of the year she wrote in her journal that this had been “the greatest year of my life—the year that brought me motherhood. I faced death in it, and came off conqueror.” She said it had been her “annus mirabilis—the wonderful year” (December 31, 1912)—a stark change from the misery she had felt when she was writing The Story Girl.

The Story Girl had been a source of joy during a difficult time. Now, during a time when she was experiencing a fair amount of happiness, on the day she finished writing The Golden Road, she wrote that “I have not enjoyed writing it. I have been too hurried and stinted for time. I have had to write it at high pressure, all the time nervously expecting some interruption—which all too surely came nine times out of ten. Under such circumstances there is very little pleasure in writing” (May 21, 1913).

The novel was published on September 1st of that year, and on that same day she started to work on a third book about Anne. “I did not want to do it,” she recorded later in September. “But Page [her publisher] gave me no peace and every week brought a letter from some reader pleading for ‘another Anne book.’ So I have yielded for peace sake. It’s like marrying a man to get rid of him!” (September 27, 1913).

The new book was, of course, Anne of the Island.

What did you think of Bev’s idea in The Golden Road to launch a newspaper? As a fan of Montgomery’s scrapbooks (and a creator of scrapbook-inspired blog posts), I like his suggestion that “We can put anything we like in the scrapbook department.”

What did you think of the New Year’s resolutions the children make? I’m fond of the Story Girl’s resolution: “I will have all the good times I can.”

I’ve collected some “golden” photos for you. First, since I said about a month ago that I’d take some pictures when the birches turn “golden as sunshine” (borrowing Montgomery’s phrase from Anne of Green Gables), here’s the birch tree in our backyard:

I found a field of golden sunflowers when my family and I visited PEI last year:

And here’s a golden field of mustard, photographed by Brenda Barry in the Annapolis Valley in Nova Scotia:

I’ll write more about The Golden Road next week. Naomi and I are talking about another LMM readalong in the spring, for Kilmeny of the Orchard. In the meantime, I’m thinking of rereading Emily of New Moon before the end of the year, because 2023 is the novel’s 100th anniversary. Do any of you want to join me? I’ll plan to write at least one post about it sometime in December.

Elizabeth Egan wrote recently in the New York Times that Montgomery’s Emily “was forged in a time of uncertainty, one similar to our own” and proposed that “At 100 years old, she deserves a spotlight of her own.” I agree, and I’m looking forward to revisiting this novel, one of my old favourites.

Previous posts about The Story Girl and/or The Golden Road

On my blog:

An Invitation to Read The Story Girl and The Golden Road

An Necklace of Expressive Words

“The best piece of work I have yet done” #ReadingStoryGirl

“This old blue chest holds a tragedy” #ReadingStoryGirl

On Naomi’s blog, Consumed By Ink:

The Story Girl Readalong #ReadingStoryGirl

On Buried in Print:

November 2023, In My Bookbag (also, L.M. Montgomery)

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

November 10, 2023

“This old blue chest holds a tragedy” #ReadingStoryGirl

Of all the stories told by Sara Stanley in The Story Girl, the one I remembered most vividly from my first reading of the novel is “The Blue Chest of Rachel Ward” (Chapter 12), the sad story of Sara’s grandmother’s cousin Rachel and the day that was supposed to be her wedding day. Sara tells Bev and the other children about how Rachel, an orphan from Montreal, came to spend a winter with relatives in Prince Edward Island, fell in love with handsome Will Montague—“an awful flirt,” according to Felicity—and got engaged. Over the winter she “made all her wedding things with her own hands,” but when the day of the wedding arrived, “Will Montague never came!”

(This is part two in a series of posts about The Story Girl and The Golden Road, by L.M. Montgomery. Naomi MacKinnon and I are hosting a readalong this month and we’re delighted to have your company! We hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments on her blog and mine, and if you write your own posts about the novel online, please share the links with us.)

Instead of wearing her wedding dress forever, as Charles Dickens’s Miss Havisham does in Great Expectations after she is jilted at the altar, Rachel Ward packed away the dress and all her linens and presents in an old blue chest and left for Montreal, taking the key with her. The Story Girl says, “This old blue chest holds a tragedy,” and for Bev and his brother Felix it takes on “a new significance,” as it seems “like a tomb wherein lay buried some dead romance of the vanished years.”

I took this photo of the blue chest, Montgomery’s source of inspiration for this story, at the Anne of Green Gables Museum in Park Corner, PEI last year:

Elizabeth Waterston writes in Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery that by writing “this complex, ambiguous novel, Montgomery had opened her own version of the blue chest” by celebrating “her memories, passions, and experiences, but also her own ambition and her own accomplishments, her books and life documents.” I found it curious, though, that Waterston doesn’t comment here on the significance of the story of the blue chest in relation to the fact that while she was writing The Story Girl,Montgomery was preparing for her own wedding day.

Near the end of the novel, the family receives news from Montreal that Rachel Ward has died, leaving instructions for the opening of the chest. Although the children get to see its contents at last, the private story of the dead romance will be lost forever, because Aunt Olivia declares that Will Montague’s letters must be “burned unread,” along with the wedding dress. Instead of a more detailed story, the children are each given an item from Rachel’s chest “to remember her by”: a blue candlestick for the Story Girl, two pink and gold vases for Felicity and Cecily, handkerchiefs for the boys, and a china plate for Sara Ray, which she plans to display on the parlour mantlepiece.

I enjoyed both Felicity’s objection that she doesn’t see “much use in having a plate just for ornament” and Sara’s insistence that “it’s nice to have something interesting to look at.” Felicity herself also likes pretty china—her rosebud plate is mentioned more than once—but she likes for it to be useful. The rosebud plate is used as a collection plate when Bev gives his first sermon, and then when Peter is recovering from the measles, she offers to lend him the rosebud plate “to eat off of. I’m only lending it, you know, not giving it. I let very few people use it because it is my greatest treasure” (Chapter 30).

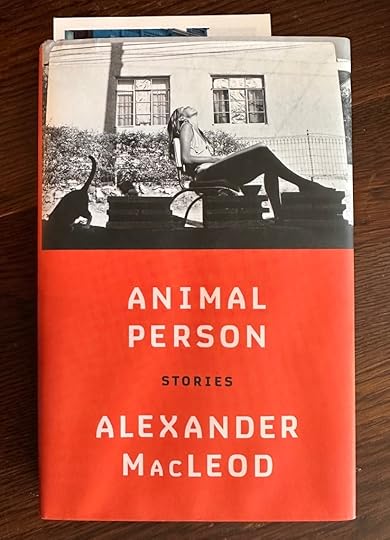

The instructions from Rachel Ward, from beyond the grave, about what she wants done with her belongings made me think of “Once Removed,” a short story by Alexander MacLeod that was published in the New Yorker a couple of years ago and is included in his collection Animal Person: “Amy thought about the afterlife of objects. All the things that were still here and the people who were not.” And about “All the things other people had loved, and all the things they did not want other people to have.”

Montgomery admired short stories. “I should like to write some good short stories,” she wrote in her journal not long after she had finished writing The Story Girl. “I consider it a very high form of art. It is easier to write a good novel than a good short story” (January 11, 1911).

(I wrote about Animal Person in a blog post last year. I don’t usually compile “top ten” lists of the best books I’ve read in a given year, but if I did, this book would have been at the top of my list for 2022. If you’re interested but don’t have time to read the whole book, you can read or listen to “Once Removed” on the New Yorker website.)

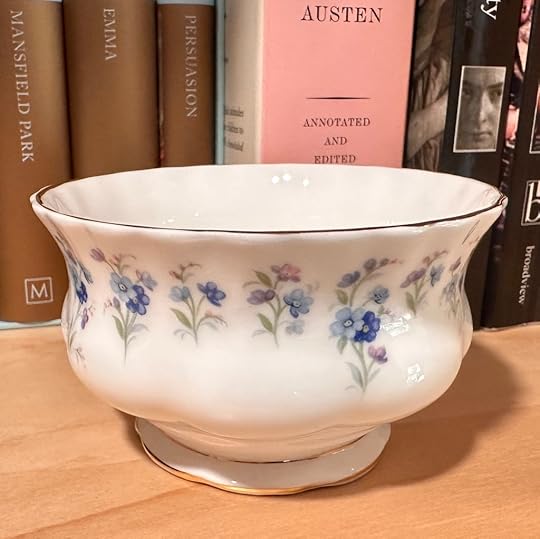

Over the course of the novel, Sara Ray starts to assemble a collection of decorative china to look at and perhaps use. I like the moment at which Cecily generously gives Sara her forget-me-not jug—“a dainty bit of china, wreathed with dark blue forget-me-nots, which Cecily prized highly, and in which she always kept her toothbrush”—after Sara has been crying about the prospect that Judgment Day will happen the next day at two o’clock in the afternoon. And I was amused to hear Felicity asking if Cecily might also be inclined to give away her cherry vase, something Felicity has long coveted (Chapter 19).

I’m fond of forget-me-not china, and I own a few pieces with Royal Albert’s Memory Lane pattern. I remember talking with my grandmother about china patterns the summer I was ten, when my family spent several weeks in Alberta: we settled on Memory Lane as our favourite. As I mentioned in last week’s post, I was around ten or eleven when I first read The Story Girl, but I have no particular memory of a connection between this scene in the novel and my conversations with my grandmother about forget-me-nots and china.

I do like to think about memories of the past, and I suppose I always have. I hadn’t read Pride and Prejudice back then either, but of course now I always think of Elizabeth telling Darcy to “Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure” (and of his insistence that sometimes it is appropriate to focus on “painful recollections”).

I don’t have a forget-me-not jug; instead, here’s a photo of a Memory Lane sugar bowl. My grandmother used to keep peppermints in it. I keep it on one of my bookshelves, as “something interesting to look at.”

When I read Chapter 16, “The Ghostly Bell,” I thought again of the Story Girl’s words about a hidden tragedy. The sad story of the cancelled wedding prefigures the loss Montgomery talks about in this chapter, the loss of imagination. When Cecily say she wishes they could find a way to get to fairyland, the Story Girl says she believes “there is such a place,” and “there is a way of getting there too, if we could only find it.” Bev as the narrator, looking back on this perfect summer, says she was right that such a place exists, but “only children can find the way to it.” When they are older, “they forget the way”: “they realize what they have lost; and that is the tragedy of life.” It seems to me this loss is the theme of the novel—the tragedy of losing the ability to imagine a world beyond “the common light of common day.”

Only a few people, Bev says, who “remain children at heart,” can still travel to that place: “The world calls them its singers and poets and artists and story-tellers; but they are just people who have never forgotten the way to fairyland.”

Bev’s vision sounds quite wonderful, doesn’t it? But when I look back at the story Sara Stanley has just told about a lady who whisks mortals away to fairyland, bids them drink from a “golden cup with jewels bright,” and makes them forget everything about their ordinary lives on earth, I can’t help but see Keats’s knight-at-arms in “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” In the poem the knight says he “met a lady in the meads, / Full beautiful—a faery’s child,” who fed him “honey wild, and manna-dew” and took him to her world—which is not an idyllic fairyland, but a place where “pale kings and princes” warned him that “La Belle Dame sans Merci / Thee hath in thrall!” He says,

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gaped wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

In this passage in The Story Girl, Montgomery seems to suggest that artists and story-tellers are fortunate because they can still find access to a magical world. But the Story Girl’s story also hints at the risks taken by those who travel to “fairyland” and bring back “tidings from that dear country.” From all I’ve read about Montgomery’s struggles as a writer, I think that even as she was celebrating the people who find their way to the world of imagination and bring back news to the rest of us, she was well aware of those risks.

In a later chapter, when the Story Girl tells the tale of the “Serpent Woman,” we get another glimpse of the risks storytellers take. She tells it so well that Bev feels a kind of “repulsion.” Like the knight in Keats’s poem, each member of her audience is enraptured, and yet they all “looked as if they were held prisoners in the bonds of a fearsome spell which they would gladly break but could not” (Chapter 23).

When her tale is told, Uncle Roger and Aunt Olivia predict future fame for the Story Girl. “You and I, Olivia, never had our chance,” Uncle Roger says, and he hopes the Story Girl will have hers. Bev comes to see that “Uncle Roger and Aunt Olivia had both cherished certain dreams and ambitions in youth, but circumstances had denied them their ‘chance’ and those dreams had never been fulfilled.” As I wrote in last week’s post, during the period in which she was writing The Story Girl, Montgomery went through phases of feeling that she had fulfilled her literary dreams, but also at times felt convinced that she would never have a chance at happiness again. Perhaps she is Uncle Roger and Aunt Olivia as well as the Story Girl here. She knows both the sweetness of success and the bitterness of unfulfilled dreams.

There are so many other things I could say about this book! For one thing, I am intrigued by Sara Ray’s response to the Story Girl’s tale of the woman who stopped speaking to her husband because they had quarreled about an apple tree they planted in their orchard. After five years, when the tree bore fruit at last and she knew she had been right to say it was a Yellow Transparent tree, she said, “I told you so!” (Chapter 21).

And then Sara Ray wants to know what happens next, and whether the woman continues to speak to her husband—a perfectly reasonable question from a reader, I think. But the Story Girl responds “wearily.” She says yes, but insists “that doesn’t belong to the story. It stops when she spoke at last. You’re never satisfied to leave a story where it should stop, Sara Ray.”

Perhaps I’m just imagining the biographical link, but to me this sounds like Montgomery speaking to her readers, who were already starting to demand sequels to her novels. I’m sympathetic to Sara Ray rather than Sara Stanley here. Like Sara Ray, I find that “I always like to know what happens afterwards.”

But on the very next page, my sympathies are with Sara Stanley, the Story Girl. Cecily gives a brief summary of a dream she had, and the Story Girl looks at her “half reproachfully.” “Why couldn’t you tell it better than that? If I had such a dream I could tell it so that everybody would feel as if they had dreamed it, too.” We do want our storytellers to tell stories in a way that makes us feel as if we were there, so that we too experience what John Gardner in The Art of Fiction calls the “vivid and continuous dream.”

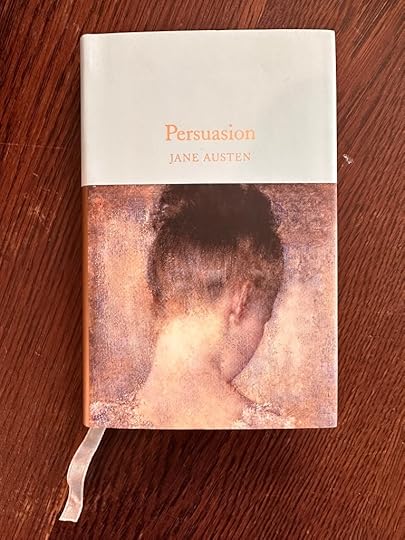

And then in the very next chapter, my sympathies are back to Sara Ray again. Bev says unkindly that “There is seldom anything to be said of Sara except to tell where she is. Like Tennyson’s Maud, in one respect at least, Sara is splendidly null.” She is often referred to as “poor Sara Ray.” Bev reminds me here of the narrator of Jane Austen’s Persuasion, talking of Dick Musgrove: “He had, in fact, though his sisters were now doing all they could for him, by calling him ‘poor Richard,’ been nothing better than a thick-headed, unfeeling, unprofitable Dick Musgrove, who had never done anything to entitle himself to more than the abbreviation of his name, living or dead” (Volume 1, Chapter 6). Sara Ray doesn’t receive quite the same harsh treatment, but she is routinely dismissed as unimportant. “Sara Ray’s own dreams never amounted to much,” says Bev (Chapter 22). Maybe she’s more like Anne Elliot in Persuasion, who is seen by her family as “only Anne” (Volume 1, Chapter 1).

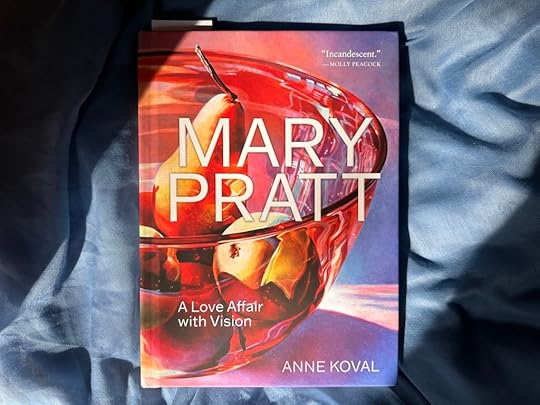

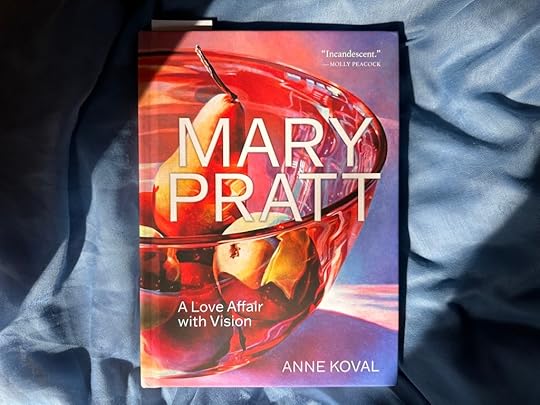

The Story Girl is repeatedly associated with the colour red, and one passage in particular made me think of another book I’m reading this month, Mary Pratt: A Love Affair with Vision, by Anne Koval. In the letter Felicity writes to Peter when he’s recovering from a near-death experience with measles, she describes the “new red dress, and a red velvet cap from Paris” that the Story Girl’s father is going to send her. Felicity herself doesn’t like the colour red because “it looks so common,” which seems to me an unusual perspective.

Koval quotes Mary Pratt’s response to a red velvet dress worn by Susan Hayward in a movie she saw in the 1950s: “I thought this was just beautiful, so I decided to stay for the second showing of the movie.” She became obsessed with the movie, and wanted to own it, but then found that even watching Hayward singing and dancing in that dress wouldn’t be sufficient. “No, that’s not enough,” Pratt said. “I have to be Susan Hayward.” Her ambition went far beyond admiration. “First,” she said, “I want to see that image again; no, I have to own that image; no, I have to be that image.” Koval’s book includes images of Hayward in a red dress, in a publicity photo for With a Song in My Heart, and of Pratt in a strapless red velvet gown.

I found it interesting that just before Koval tells this story, she writes of Pratt’s love of Anne of Green Gables. She quotes Pratt’s memory of “driving up the St. John River Valley in the springtime, thinking it was so beautiful, and wishing I could do for New Brunswick what L.M. Montgomery had done for Prince Edward Island.”

In The Golden Road, which I’ve just started reading, the Story Girl says “I’d never get tired of red. … I just love it—it’s so rich and glowing. When I’m dressed in red I always feel ever so much cleverer than in any other colour. Thoughts just crowd into my brain one after the other” (Chapter 3). I don’t know what colour Mary Pratt was wearing when she wrote of her ambition to be like L.M. Montgomery, but I’m going to hazard a guess that she was wearing red.

Here are some photos of the red leaves of autumn in Nova Scotia, taken by Brenda Barry in the Historic Gardens in Annapolis Royal:

Montgomery’s descriptions of autumn in PEI are beautiful. “November dreamed that it was May. The air was soft and mellow, with pale, aerial mists in the valleys and over the leafless beeches on the western hill. The sere stubble fields brooded in glamour, and the sky was pearly blue.”

This is my photo of an August sky, but since it’s “pearly blue,” perhaps we can imagine that it’s either November or May:

Let’s go with May, shall we? Even though it’s November right now. Bev concludes the book by looking back at the beautiful months this band of friends has had together, in which they have known “the sweetness of common joys” and had “brotherhood with wind and star, with books and tales, and hearth fires of autumn.”

Here’s a photo of autumn leaves that I took a couple of weeks ago, on a warm October day:

I’m keen to read more of The Golden Road and I’m looking forward to discussing it with you next week.

I’d like to give Sara Ray the last word. Near the end of The Story Girl, in her letter to Peter, she writes that “We are having beautiful weather and the seenary is fine since the leaves turned. I think there is nothing so pretty as Nature after all” (Chapter 30).

Previous posts about The Story Girl and/or The Golden Road

On my blog:

An Invitation to Read The Story Girl and The Golden Road

An Necklace of Expressive Words

“The best piece of work I have yet done” #ReadingStoryGirl

On Naomi’s blog, Consumed By Ink:

The Story Girl Readalong #ReadingStoryGirl

On Buried in Print:

November 3, 2023

“The best piece of work I have yet done” #ReadingStoryGirl

L.M. Montgomery wrote The Story Girl at a time when she had achieved literary success with her first two novels about Anne Shirley, and was anticipating the day when she would marry her fiancé and move away from her beloved Prince Edward Island. Elizabeth Waterston writes in Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery that Sara Stanley, the heroine of The Story Girl, is “an idealized self-portrait of the author as a young girl.” Waterston writes of Montgomery’s cleverness in “showing off through Sara’s stories the breadth of the range of her interests, while keeping her unsophisticated readers happy with what looks like another visit to the magic island of the Anne books.” As the narrator of the book, Beverley King, looks back on the idyllic childhood summer he spent with his brother and relatives and friends in PEI, Montgomery looks back at the island that has been her home for many years, and prepares to take leave of the people and the place.

My friend Marianne’s copy of the first edition of The Story Girl

(This is part one in a series of posts about The Story Girl and The Golden Road. Naomi MacKinnon and I are hosting a readalong this month and we’re delighted to have your company! We hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments on her blog and mine, and if you write your own posts about the novel online, please share the links with us. #ReadingStoryGirl)

I hadn’t read The Story Girl since I was about ten or eleven, and I had forgotten where it falls in the chronology of Montgomery’s literary career. I was interested to learn that it was her fourth published novel, after Anne of Green Gables in 1908, Anne of Avonlea in 1909, and Kilmeny of the Orchard in 1910. I didn’t realize that it predates the Emily trilogy, her now more famous portrait of an artist as a young girl.

In writing The Story Girl, Montgomery experienced extremes of joy and despair. She began on June 1, 1909, writing in her journal that “The germinal idea has been budding in my brain all winter and this evening I sat me down in my dear white room and began it. I think it is a good idea and I think I shall be able to make a good piece of work out of it. But I feel sad, too, for I cannot be sure that I shall be long enough in this old house to finish it and it seems to me that I could never write it as it should be written anywhere else—that some indefinable, elusive ‘bouquet’ will be missing if it is written elsewhere.”

Waterston writes of the joy Montgomery found in writing the opening chapters in the summer and fall of that year, and then of what happened when she stopped working on The Story Girl to produce a quick draft of Kilmeny of the Orchard, to meet her publisher’s demands. On December 23rd, Montgomery wrote that “A fortnight ago I saw that I would not be able to finish it [Kilmeny] at my regular rate of progress, so I have been writing at it every minute since, until I would fairly feel faint with fatigue. But I shall have it done on time.” Her publisher wanted the manuscript by New Year’s.

She met the deadline, but the intensity of the work meant that she had no energy left to return to The Story Girl. In February of 1910, she received a royalty cheque for more than seven thousand dollars, but said “It seems like mockery that this money should come to me now when I am perhaps too broken ever to enjoy it…. There are as yet very few days when I can work. My new book is at a standstill…” (February 19, 1910). She had had what she called “an utter breakdown of body, soul, and spirit” and she believed she was experiencing a form of hell. She felt that “We can endure almost any pain if we can hope that it will pass. But when we are convinced that it will never pass it is unbearable” (February 7, 1910).

Mary Rubio writes that Montgomery told her fiancé, Ewan Macdonald, “of her despondent spirits, and he suggested that she give up her writing. He was unable to see that her writing was an integral part of her spirit and sense of self, and that it was, in fact, what sustained her” (Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings). She found tremendous comfort through the process of writing in her journal and said she couldn’t live without it: “Temperaments like mine must have some outlet, else they become morbid and poisoned by ‘consuming their own smoke.’” (She’s quoting from Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus.) She resolved “to write out my happiness as well as my pain” (February 11, 1910).

By spring she was able to work on The Story Girl again, and the novel was complete by October of 1910. In September, she was invited to meet the Governor General of Canada, Lord Grey, and in October, she travelled to Boston to meet her publisher. (I’m tempted to write more about that Boston trip sometime.) “I consider ‘The Story Girl’ the best piece of work I have yet done,” she wrote when she reached the end of the novel. “I have written it from sheer love of it and revised it painstakingly—up there by the window of my dear white room. It may be the last book I shall ever write there” (November 29, 1910). I’m glad she got her wish and was able to finish writing the novel in that room. Waterston writes that “Part of its excellence lay in the way it reflected the swings of mood that had beset her.”

The last time I visited the Macneill Homestead, in Cavendish, PEI, where Montgomery wrote The Story Girl, I saw part of the damage that had been done by Hurricane Dorian, including this fallen tree across the old foundation of the house.

This Project Bookmark Canada plaque is located at the Macneill Homestead, and features the text of Montgomery’s poem “The Gable Window,” which describes the view from her room. The poem was published in 1897, when she was twenty-three, and it focuses on “a world of wonder, / When summer days were sweet and long.” (Sounds a lot like The Story Girl, doesn’t it?)

I loved reading the descriptions of the island’s natural beauty in The Story Girl, including Bev’s description in Chapter 2 of what it felt like to explore the old King homestead on the first morning:

I wakened shortly after sunrise. The pale May sunshine was showering through the spruces, and a chill, inspiring wind was tossing the boughs about. …

… we opened the front door and stepped out, rapture swelling in our bosoms. There was a rare breeze from the south blowing to meet us; the shadows of the spruces were long and clear-cut; the exquisite skies of early morning, blue and wind-winnowed, were over us; away to the west, beyond the brook field, was a long valley and a hill purple with firs and laced with still leafless beeches and maples.

This photo doesn’t capture the right time of year or the landscape Montgomery describes, but it is a PEI sunrise, so I thought I’d include it anyway…

August sunrise over Dalvay Lake

I have a few questions for you about The Story Girl. What did you think of L.M. Montgomery’s choice of a male narrator? I think it’s interesting that after the first two novels about Anne Shirley, she wrote two novels from the point of view of a male character—even though Kilmeny and the Story Girl are still at the centre of both books (Kilmeny of the Orchard is narrated by Eric Marshall, a schoolteacher). As a storyteller, how does Bev King compare with Sara Stanley, the Story Girl?

(Also—would you like to read Kilmeny of the Orchard with me sometime? Maybe this could be our focus for a future readalong.)

I have to say I have some reservations about Bev as a narrator. I’m not sure I believe him when, for example, after describing the Story Girl with her arms full of roses and a “chaplet” of them in her curls, he claims that “We always remembered the picture she made there; and, in later days, when we read Tennyson’s poems at a college desk, we knew exactly how an oread, peering through the green leaves on some haunted knoll of many fountained Ida, must look” (Chapter 18). Who is the ”we” here? Can it really include Felix, Felicity, Peter, and the others, or is he speaking only of himself? (Or is this even Bev speaking—it sounds to me more like Montgomery herself.)

Waterston suggests Montgomery might have chosen a male narrator in an effort to reach a wider audience than the one she had found with her Anne novels, or that she might have “intended to mollify literary critics, who generally assumed that a male point of view was more significant than a female one.”

What do you make of Bev’s comments on how “we liked the prospect of our summer very much. Felicity to look at—the Story Girl to tell us tales of wonder—Cecily to admire us—Dan and Peter to play with—what more could reasonable fellows want?” My friend Marianne says this passage is “sort of awful,” and I agree.

Later in the novel, however, Marianne says she feels that Bev has “partly redeemed his early comment about the girls”: she writes that “in chapter 14, Forbidden Fruit, Cecily proves to be the hero when Dan eats a handful of ‘bad berries.’ Our narrator says, ‘Cecily took charge of things. Felicity might charm the palate, and the Story Girl bind the captive soul; but when pain and sickness wrung the brow, it was Cecily who was the ministering angel.” Then, she says, “in chapter 19, when the children fear the next day will be Judgment Day and Sara Ray can’t stop weeping, our narrator says, ‘Cecily and Felicity and the Story Girl did not cry. They were made of finer, firmer stuff. Dry-eyed, with such courage as they might muster, they faced whatever might be in store for them.” So, Marianne concludes, “I feel a little better about Bev’s stance on ‘the fairer sex’ (not his words). He seems to learn that girls have value beyond being nice to look at.”

Dalvay Lake, later in the day

What did you think of the stories themselves? Did you find the Story Girl as “fascinating” as Bev and the others say she is? “Yes, the Story Girl was fascinating and that was the final word to be said on the subject” (Chapter 3).

Why are there two girls named Sara in this book? Sara Stanley is the Story Girl, while Sara Ray is a “nice girl” with a “dreadfully strict” mother who “never allows Sara to read a book.” The contrast between the two is clear, but I think it would have been pretty clear even if they didn’t share the same name.

(I’ve always wondered why neither of them has an “h” at the end of her name, I suppose because I feel as attached to the “h” in my own name as Anne Shirley is to her “e.”)

Next Friday, I’ll write more about The Story Girl, and after that let’s turn to the sequel, The Golden Road.

Previous posts about The Story Girl and/or The Golden Road

On my blog:

An Invitation to Read The Story Girl and The Golden Road

An Necklace of Expressive Words

On Naomi’s blog, Consumed By Ink:

October 27, 2023

A Necklace of Expressive Words

“… feeling all the happy privilege of country liberty, of wandering from place to place in free and luxurious solitude, she resolved to spend almost every hour of every day while she remained with the Palmers, in the indulgence of such solitary rambles.”

I went in search of a Jane Austen quotation to accompany this stereoscopic card captioned “Solitude, Fairmount Park, Philadelphia,” which I found in an antiques shop in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia last Sunday, and I settled on this passage from Sense and Sensibility (Volume 3, Chapter 7). (I don’t own a stereoscope, but I liked the image and bought the card anyway.) Within five minutes of her arrival, Marianne Dashwood has slipped away to walk “through the winding shrubberies, now just beginning to be in beauty, to gain a distant eminence; where, from its Grecian temple, her eye, wandering over a wide tract of country to the south-east, could fondly rest on the farthest ridge of hills in the horizon, and fancy that from their summits Combe Magna might be seen.”

Jane Austen captures the torments of Marianne’s mind and heart beautifully here, showing how closely pleasure and pain are linked: “In such moments of precious, invaluable misery, she rejoiced in tears of agony to be at Cleveland,” staying with the Palmers in a house so near to Willoughby’s, indulging in and even enjoying her sorrows and longings.

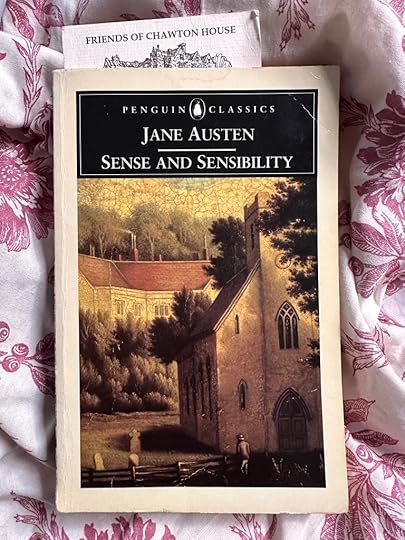

I found an old Friends of Chawton House membership card tucked into one of my copies of Sense and Sensibility:

After that road trip to Mahone Bay on Sunday, I saw this gorgeous sunset over the Macdonald Bridge, which links Halifax and Dartmouth, so I stopped to take a picture.

Looking across to Halifax, Georges Island, and McNabs Island from the Dartmouth waterfront:

I’m reading L.M. Montgomery’s novel The Story Girl, preparing for next month’s readalong. I’m only a few chapters in and will be keen to read more this weekend. My friend Naomi, who’s co-hosting the readalong with me, wrote about the book in a recent blog post that includes a variety of cover images for The Story Girl and The Golden Road.

As I’m sure I’ve mentioned here before, I’m partial to the covers created by Elly MacKay for the Tundra editions.

I also loved seeing this beautiful first edition of The Story Girl, which belongs to my friend Marianne:

It occurred to me that the word “solitude” is very likely important to Sara Stanley, the Story Girl, as well as to Marianne Dashwood, so I searched and found a passage in which Sara defends the word “deviltry,” which her friend Felicity believes to be a swear word. Sara explains that the word “only means extra bad mischief” and Felicity insists “it’s not a very nice word, anyhow.” Sara regrets that “It’s very expressive, but it isn’t nice. That is the way with so many words. They’re expressive, but they’re not nice, and so a girl can’t use them.”

She sighs, and Montgomery tells us, “She loved expressive words, and treasured them as some girls might have treasured jewels. To her, they were as lustrous pearls, threaded on the crimson cord of a vivid fancy. When she met with a new one she uttered it over and over to herself in solitude, weighing it, caressing it, infusing it with the radiance of her voice, making it her own in all its possibilities forever” (Chapter 21).

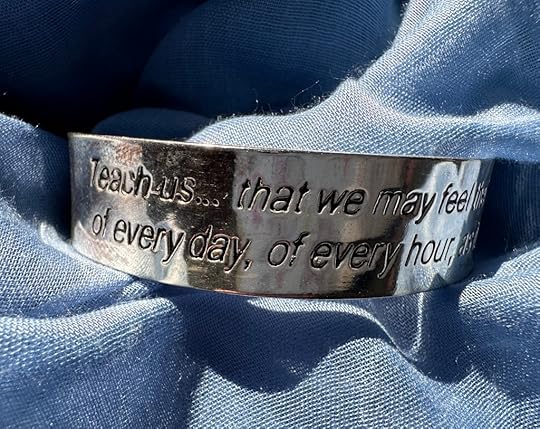

Isn’t that a lovely image, of a necklace or bracelet made of expressive words? I’m often drawn to jewellery that features words or quotations, including a silver bracelet I bought from JASNA’s New York Region several years ago—“Teach us … that we may feel the importance of every day, of every hour, as it passes” (from one of Jane Austen’s prayers)—and a leather bracelet my friend Lisa gave me as a birthday present—“I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of anything than of a book!—When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library” (from Pride and Prejudice).

I also have a name bracelet made my teenage friend Sofia, creator of Fia Bijoux, a jewellery business she founded when she was twelve. (Her jewellery is beautiful and she donates 20% of all profits to the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto.)

I asked Sofia for green and blue beads, two of my favourite colours, and I love the turquoise letter beads because they remind me of Jane Austen’s turquoise ring and turquoise beaded bracelet.

Do any of you have favourite jewellery that features words, names, or quotations?

Now I’m picturing a necklace with words from L.M. Montgomery’s novels, including “deviltry,” “scrumptious”—“Oh, Marilla, I’ve had a perfectly scrumptious time. Scrumptious is a new word I learned today…. Isn’t it very expressive?” (Anne of Green Gables, Chapter 14)—and “fascinating”—“Yes, The Story Girl WAS fascinating and that was the final word to be said on the subject” (The Story Girl, Chapter 4).

October 20, 2023

“There are two ways of spreading light”

Edith Wharton wrote that “There are two ways of spreading light: to be / The candle or the mirror that reflects it.” I’m going to revise the ending of the quotation slightly so I can use it as a caption for this photo, and say “or the piano that reflects it.” These lines are from her poem “Vesalius in Zante,” published in the North American Review in 1902.

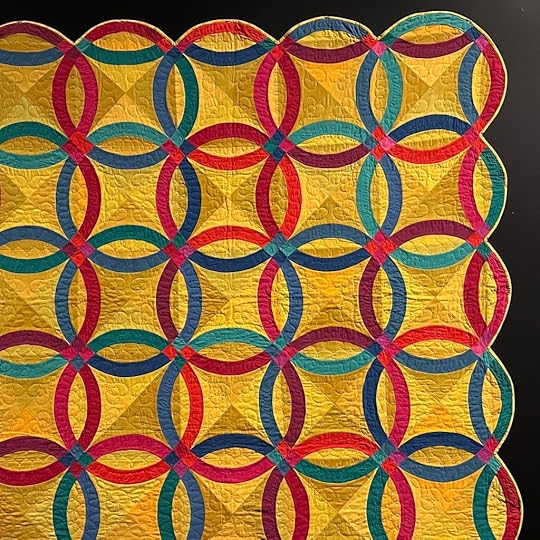

For today’s scrapbook blog post, I want to share some of the things I’ve enjoyed seeing or reading about over the past week: an exhibition of quilts, a short video featuring Ursula K. Le Guin, a mother-daughter road trip to PEI, and a new novel for fans of Jane Austen.

Last week, I went to the opening of “By Her Hand: Contemporary Quilts Inspired by the Nova Scotia Museum,” an exhibition of stunning quilts created by Andrea Tsang Jackson and Marilyn Smulders. Marilyn is a friend of mine, and I’m the proud owner of a gorgeous quilt she made a few years ago, entitled “Homage to the Homage to the Square.” I was delighted to see that quilt in the background of Marilyn’s photo. If you’re in Halifax in the coming months, you should go see the exhibition, which is on at the Museum of Natural History until January 7th.

“He’s my first reader,” Ursula K. Le Guin says of her husband, Charles, in a delightful interview with the two of them, sitting by the fire in the house they shared for decades. I’ve read very little of her work and would like to explore further. Do any of you have suggestions?

I enjoyed this essay about a road trip to Prince Edward Island: “Road to Avonlea: Amanda Parrish Morgan on the Transportive Intimacy of Reading and Long Drives.” Morgan writes that “Reading a book aloud, especially to a child, means getting on that frigate together, being passengers in the same car, not just with a character with whom we might feel like kindred spirits, but with each other. The car, the book, the trip—all means of getting somewhere unknown together.”

Here’s my photo of the view from the Confederation Bridge, from a road trip to PEI several years ago. Stopping on this narrow bridge isn’t allowed, but on this occasion, we had to stop because of construction, so I was able to take a photo. Morgan says that although she isn’t a nervous driver, she found it challenging to drive over this eight mile bridge: “it required mantras and affirmations like those I’d used during childbirth or in the final miles of a marathon.”

Happily for Morgan, she found that “The bridge and the terror it induced seemed, somehow, to make the rolling hills of PEI and the sweet reconstructions of Anne’s world all the more bucolic.”

One of my photos from a family holiday in PEI a couple of years ago:

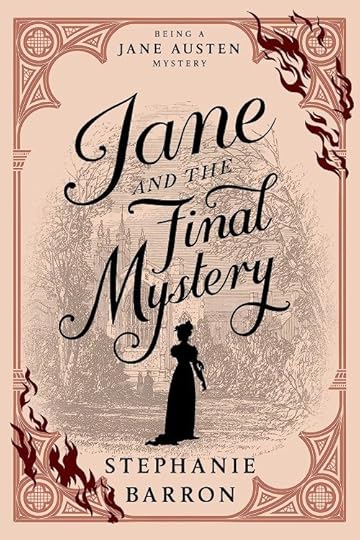

Jane Austen fans might be interested in Stephanie Barron’s new novel, Jane and the Final Mystery, the last in a series of fifteen mysteries that started with Jane and the Unpleasantness at Scargrave Manor. My friend Laurel Ann Nattress of Austenprose.com writes that this last novel is “a poignant, compelling, and uplifting story.” She says “the immaculately researched mysteries are standalone stories, so please do not hesitate to jump right in with book fifteen, and then circle back to any of the previous novels.” I’ve read a few of the books in the series, and I have a particular fondness for Jane and the Ghosts of Netley. Do any of you have a favourite Stephanie Barron novel you’d like to recommend?

I’ll leave you with one last photo, of our dog, June, keeping me company in my office.

October 13, 2023

“Beyond lay the sea, shimmering and blue”

I’m quoting Anne of Green Gables again, remembering what my sister Bethie said earlier this year about how she and I quote from Pride and Prejudice so often that it’s almost as if we’re living in the novel. I suppose the same is true of the “Anne” books. “‘Isn’t the sea wonderful?’” Anne asks Marilla. “Down at the base of the cliffs were heaps of surf-worn rocks or little sandy coves inlaid with pebbles as with ocean jewels; beyond lay the sea, shimmering and blue, and over it soared the gulls, their pinions flashing silvery in the sunlight.”

I took these photos on Monday on a walk with my husband and our dog at Second Peninsula Park, near Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia. I thought of Anne as we drove out of the park, too, and I stopped to take a picture of “the bend in the road.”

(I took this photo in Fredericton, PEI, several years ago.)

My family and I moved to a new house at the end of the summer—we’re still in the same beloved neighbourhood in Halifax—and as we unpack boxes and settle in, I’ve continued to think about the line from Anne of Green Gables I quoted last week, about how “One can dream so much better in a room where there are pretty things.” I’m grateful for the treasures we’ve acquired over the years, many of them presents from friends and family. Amidst all the chaos of moving, I’ve enjoyed unpacking and reorganizing our books.

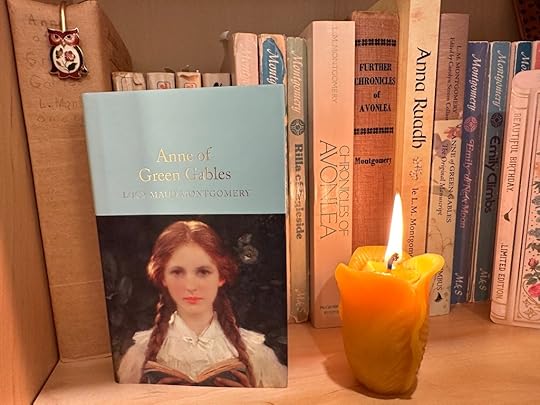

My friend Marianne Ward gave me a beautiful beeswax candle the other day as a housewarming present and I took a picture of it next to some of my favourite books, including an edition of Anne of Green Gables that I recovered in brown paper when I was about ten. (I’m not sure why I left out the “M” in L.M. Montgomery’s name when I wrote it on the spine—that might be as bad as leaving out the “e” at the end of Anne’s name! Maybe even worse, since Montgomery hated being called “Lucy.”)

Anna Ruadh is the first Gaelic translation of Anne of Green Gables, published in 2020 by Bradan Press, and next to that is a copy of Anne of Green Gables: The Original Manuscript, edited by Carolyn Strom Collins—and copy-edited by Marianne. Carolyn and Marianne are currently working on an edition of the manuscript of Montgomery’s The Blue Castle, which, like the “Anne” manuscript, will also be published by Nimbus.

In the spirit of L.M. Montgomery’s scrapbooks, and continuing the “blog post as scrapbook” format that I used here earlier this year, here are a few more things I’d like to share with you this week.

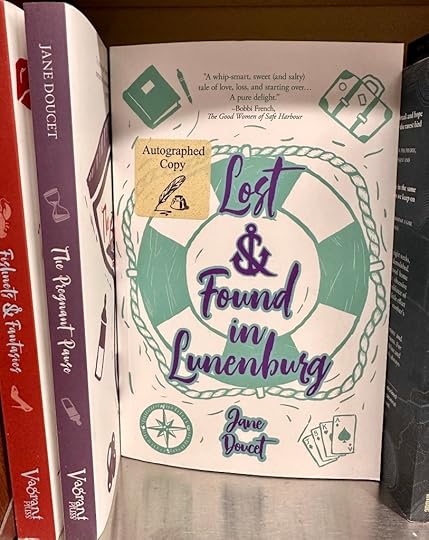

If you’re in or near Halifax, you might be interested in tomorrow’s book launch for my friend Jane Doucet’s novel Lost & Found in Lunenburg, in which recently-widowed Rose Ainsworth takes a chance on a new life in the picturesque town of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. I read it earlier this month and loved it. If you like novels about changing careers, rescuing animals, or finding romance after heartbreak, and if you like a healthy dose of laughter right alongside that heartbreak, you’ll enjoy this book, and you’ll probably want to go back and read The Pregnant Pause, Jane’s first novel about Rose. Jane writes “happy endings because there are so many sad endings in real life.” She says, “I write books that I’d like to read myself. I put in heavy themes—motherhood indecision, aging and sex, grief and loss—but I wrap them in a warm ‘humour hug.’”

The launch for Lost & Found in Lunenburg is Saturday, October 14th, at 10:30am, at Open Book Coffee, 3660 Strawberry Hill Street, Halifax.

This week I started reading a new biography, Mary Pratt: A Love Affair with Vision, by Anne Koval, and I was delighted to find a reference to L.M. Montgomery in the opening pages. Koval quotes Pratt: “I always keep Agatha Christie and L.M. Montgomery and a few cookbooks within reach. … The straightforward, blunt, and simple observations and instructions found within these unpretentious books smooth the way for me and allow me to go alone into personal observations.” I’m intrigued by the idea that something about the simplicity and clarity of these books inspired Mary Pratt’s own creative work.

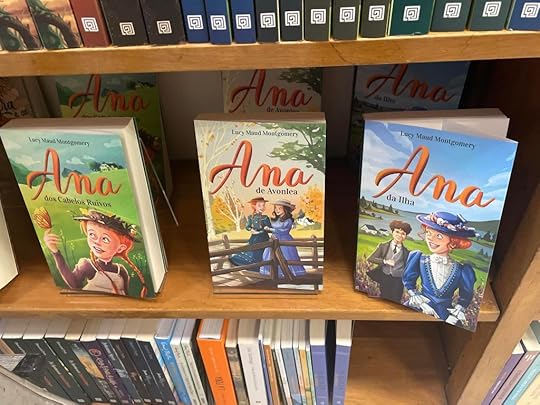

Heidi L.M. Jacobs, author of Molly of the Mall, sent me this lovely photo of the first three “Anne” books, spotted on her travels in Portugal:

Last but not least: Sandra Barry sent me some beautiful photos taken by her sister Brenda in the Historic Gardens in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia:

Sandra says this is “a little tomato we had never seen before, called, of all things: Amethyst Cream—they were shimmery, no less—hard to capture it, but I think you can sort of see it.”

October 6, 2023

“One can dream so much better in a room where there are pretty things”

In a conversation with Marilla in Anne of Green Gables, Anne Shirley famously says, “I’m so glad I live in a world where there are Octobers.” I like going back to look at the rest of that passage, including Anne’s insistence that the “gorgeous boughs” she’s brought into the house ought to give even Marilla “a thrill—several thrills” and that she’s going to decorate her room with them because “One can dream so much better in a room where there are pretty things. I’m going to put these boughs in the old blue jug and set them on my table.”

This beautiful bouquet was a birthday present from my family. When the birches turn “golden as sunshine” and the maples are “royal crimson,” I’ll bring in some leaves or branches (or perhaps I’ll just take photos.)

Happy October to all of you! I’m looking forward to discussing L.M. Montgomery’s novels The Story Girl and The Golden Road with you in November. In the meantime, if you’re looking for more opportunities to talk about Montgomery, you might be interested in the Anne of Green Gables readalong that Jana of Review from the Stacks is hosting this month.

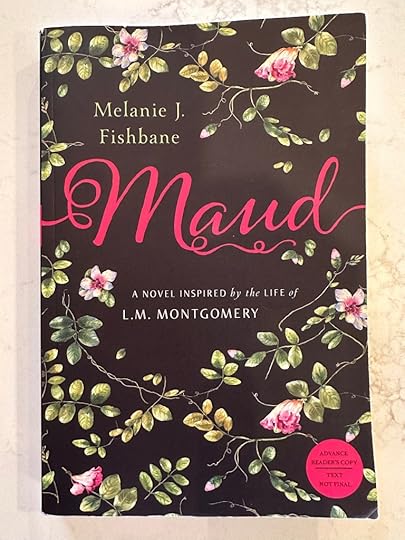

In today’s post, Jana features a link to her review of my friend Melanie J. Fishbane’s wonderful novel Maud: A Novel Inspired by the Life of L.M. Montgomery. Jana writes,

“Fishbane’s writing in Maud is beautiful. I have heard it compared to Montgomery’s own (no surprise there), Laura Ingalls Wilder, and other 19th century writers. Fishbane’s thorough research has not only given her the knowledge and ability to write a plausible fictional account of a portion of Montgomery’s life, it also allowed her to tap the styles and particularities of writing descriptive of the era she is writing about. The prose flows easily, reads quickly, and sinks pleasantly into the reader’s mind.”

(“Friday Linkups 23.9 Featuring Maud by Melanie J. Fishbane”)

When Melanie visited Halifax in the summer of 2017, she and I, along with my friend Marianne Ward, visited several L.M. Montgomery-related sites here, including the Old Burying Ground (“Old St. John’s Cemetery” in Anne of the Island) and the Forrest Building at Dalhousie University (“Redmond College”). If you’re interested, you can find the photos from that tour in the introduction to a guest post Melanie wrote for my blog, “Searching for Maud in the ‘Emily’ Series.”

I found it fascinating to reread what Melanie says in her guest post about fourteen-year-old Montgomery burning her diary, then starting a new one and announcing that this time, “I am going to keep this book locked up!!” We’ll never know what was in that first diary, but as Melanie says, writing an historical novel gave her the chance to imagine.

The post also includes photos of Melanie reading at one of my favourite bookstores, Mabel Murple’s; Melanie with the owner of Mable Murple’s, Sheree Fitch; and a photo of Melanie and me with Naomi MacKinnon. Lots of good memories!

Naomi is my co-host for The Story Girl/The Golden Road readalong—and we first met online when we were participating in a different Anne of Green Gables readalong, years ago. We discovered that we both live in Nova Scotia, soon made plans to meet in person, and have been good friends ever since. I hope you’ll join us next month for more conversations about LMM.

July 28, 2023

“The castled crag of Drachenfels”

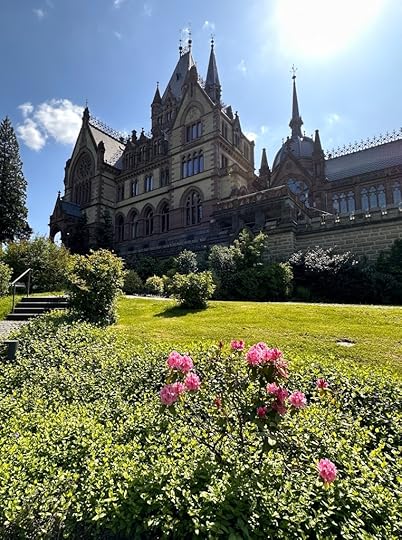

We had spectacular weather for our day trip up the Rhine from Bonn to Königswinter and Drachenfels.

(These photos are from my trip to Germany in May, when I spent a couple of days travelling with my sister Bethie and her family, and my brother Tom and his daughter. I shared some photos from my solo trip to Amsterdam last Friday.)

On the hill at the right, you can see the ruined castle Burg Drachenfels; a little further down and to the left of the ruin is a 19th Century neogothic castle, Schloss Drachenburg.

As Byron wrote in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,

The castled crag of Drachenfels

Frowns o’er the wide and winding Rhine.

Whose breast of waters broadly swells

Between the banks which bear the vine,

And hills all rich with blossomed trees,

And fields which promise corn and wine,

And scattered cities crowning these,

Whose far white walls along them shine,

Have strewed a scene, which I should see

With double joy wert thou with me!

When I first wrote about reading L.M. Montgomery’s novel Jane of Lantern Hill in early May, I quoted Jane’s father’s plan to take her to visit “castles on the banks of the Rhine,” but at that point on this particular trip to Germany, I hadn’t yet seen any castles. Here are a few photos of Schloss Drachenburg and its gardens:

And a photo of my sister Bethie, my brother Tom, and me:

From the castle, we could see Cologne in the distance. Cologne Cathedral is visible off to the right:

I had taken this photo of the Cathedral a few days earlier, when I was waiting for my train to Amsterdam:

Here are a couple of views of the Rhine and the Siebengebirge from the ruined castle at Drachenfels:

We travelled back to Bonn on the Poseidon. Here’s the view of the 19th and 12th Century castles from the boat as we were leaving:

The following day, we visited Cologne Cathedral (and had lunch—and chocolate—at the Schokoladenmuseum).

The chocolate fountain at the museum:

The Cologne Cathedral window designed by Gerhard Richter:

Here are a few photos from the Bonn Botanic Gardens:

I’ll end with a couple of photos from the beginning of my trip: a sunset in Toronto, just as my flight was taking off, and the view from the plane just before it landed in Frankfurt the next morning. And then one last photo of the view from Drachenfels.

I’m going to take a break from writing blog posts for the next several weeks, to spend more time enjoying summer here in Nova Scotia with my family.

Happy August and September to all of you, and I’ll see you in the fall! I’m looking forward to discussing L.M. Montgomery’s novels The Story Girl and The Golden Road with you in November.

If you liked this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

July 21, 2023

“In mijn boek” (Photos from a trip to Amsterdam)

I enjoyed three wonderful weeks in Bonn back in May, with a few days in Amsterdam and a couple of day trips to Cologne, and I’ve put together some of my favourite photos to share with you. I’ll start with the Amsterdam trip today, and I’ll save the photos from Germany for next Friday.

First, the spectacular library in the Rijksmuseum. I missed the chance to see the “once-in-a-lifetime” Vermeer exhibition—tickets had been sold out for months, and I didn’t plan my trip until April—but I enjoyed visiting the library and touring the other galleries. Besides, aren’t we always missing “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunities? Every single day is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and I made the most of the days I was fortunate to spend in Amsterdam.

I’m quite fond of the art in the Rijksmuseum garden: grass sculptures by Richard Long, entitled “Life Line” and “From Sky to Earth.”

And I liked the flower market very much.

I took the bicycle and canal photos everyone takes, along with photos of tulips at the Tulip Museum.

I visited Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic), a 17th Century canal house with a Catholic Church hidden on the top floors.

At the Royal Palace, I was drawn to the huge map on the floor of the Citizens’ Hall, especially the part featuring Atlantic Canada (Acadia and Terra Nova).

After a while, the palace rooms sort of blurred together in my mind, and I could hear the voice of Mrs. Gardiner from Pride and Prejudice: “‘If it were merely a fine house richly furnished,’ said she, ‘I should not care about it myself; but the grounds are delightful.’”

I did like the chandeliers in the Citizens’ Hall:

And this stunning chandelier at the Concertgebouw:

My friend Sheila had recommended the Concertgebouw, and I was able to get tickets to hear a splendid concert by Lenny Kuhr, whose song “De troubadour” was one of the winners of the Eurovision Song Contest in 1969, and whose most recent album was released in 2022. I was thrilled to discover her music, and to meet her afterwards. (It was, I must say, a once-in-a-lifetime experience.)

I especially like her song “In mijn boek” (In my book), which is about love and heartbreak. (“Ooit komt er een dag dan schrijf ik het op”: Someday there will be a day when I’ll write it down.)

By the time I returned to my sister’s house in Bonn, my brother and my niece had arrived from Nova Scotia and our visits overlapped for a couple of days. We visited Königswinter and Drachenfels the first day, and then Cologne on the second, and I’ll share those photos with you next week.

If you liked this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!