Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 15

May 5, 2023

Back in Bonn with Bethie, #ReadingLanternHill

My sister Bethie and I are reading L.M. Montgomery’s Jane of Lantern Hill and I hope you’ll join us! As I mentioned here a couple of months ago, my friend Naomi and I are hosting a readalong for Jane of Lantern Hill, and we plan to post about it at least a couple of times this month—maybe more. Please join the conversation in the comments here on my blog, on Naomi’s blog, Consumed By Ink, on social media (#ReadingLanternHill), and/or on your own blog.

Bethie and I are also planning to watch the 1989 Jane of Lantern Hill movie while I’m in Germany. Have any of you seen it?

L.M. Montgomery started writing Jane of Lantern Hill in May of 1936 and completed it in February of 1937. As Caroline E. Jones outlines in an essay on “The New Mother at Home: Montgomery’s Explorations of Motherhood” (in L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys), these months were difficult for her, as she worried about her sons Chester and Stuart, mourned the loss of her cat Lucky, and endured an event on January 29, 1937 that she never explained, aside from recording in her diary that “On that day all happiness departed from my life forever.” It seems this event may have had something to do with her son Chester, though no one knows for sure. Jane of Lantern Hill was published later that year, twenty-nine years after Montgomery’s first and most famous novel, Anne of Green Gables, appeared in print. The novel is dedicated to the memory of Lucky, “The charming affectionate comrade of fourteen years.”

In her magnificent biography of Montgomery, Mary Henley Rubio describes the pace at which this novel was written. In September of 1936, Montgomery wrote in her diary that she was writing up to five hours a day, working quickly to try to finish the book. The following winter, because of the challenging circumstances of her personal life, she found it extremely difficult to write the ending. Eventually, Rubio says, “she steeled herself to finish Jane of Lantern Hill … , managing to do so through sheer grit.”

Jones writes that in these later years, Montgomery “wrote her final books and reflected on a life that she believed had failed.” In her novels, however, “she offers her protagonists a wide sense of family and empowers them with the ability to find both their own mother figures and shape themselves as mothers.” Jane, for example, is always looking for ways to take care of others. When she first meets her neighbour Jody, who’s “sobbing bitterly” beneath a cherry tree, Jane’s first instinct is to ask “Can I help you?” and we learn that “those words were the keynote of her character.”

(I missed the cherry blossom festival in Bonn; only a few spots of pink remain on the trees.)

Jane’s mother, Robin, made me think of Maria Bertram in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. As Jones says, “Jane’s mother is depicted as a bird in a cage from which she envisions no escape, caught in a round of dances, parties, and afternoon teas.” During the visit to her fiancé’s estate, Sotherton, Maria Bertram—who is in love with another man—says that while “the sun shines, and the park looks very cheerful,” the iron gate and the ha-ha give her “a feeling of restraint and hardship. ‘I cannot get out,’ as the starling said.”

I know I read Jane of Lantern Hill when I was young, but I didn’t really remember much beyond a vague sense that I loved it, and the fact that at the beginning, Jane lives in Toronto with her mother and grandmother, but then travels to Prince Edward Island and starts to get to know her father. When I read it back then, I knew Montgomery had moved to Ontario after she married Ewan Macdonald, but I didn’t have any idea of just how difficult her life became, as both she and her husband struggled with mental illness and she worried about her sons and her career. I also didn’t know that she had considered writing a sequel to the novel, which was to have been called Jane and Jody.

I’m interested in what Rubio says about how the parallels between the novel and Montgomery’s own life are obvious. “Maud herself believed in the Island’s remarkable restorative powers, particularly with respect to her own complicated life in Toronto. She also knew that she was herself partly trapped in Toronto by her own ambitions. Furthermore, Jane’s grandmother bears uncanny similarities to the woman Maud could sometimes be: a mother who meddled in her children’s romantic affairs, who tried to break up relationships she considered unsuitable, and who had fierce ambitions for her offspring.” As Rubio says, in this novel, Toronto is a “miserable” place, contrasted with “magical” Prince Edward Island.

I’m curious to hear from those of you who are reading the novel with us. What do you think of the contrasts between Toronto and PEI? I was struck by the way Jane’s grandmother’s attachment to the Toronto house, 60 Gay Street, is described. She arrived there as a bride when the house was new and grand, and although it’s “hopelessly out of date,” she is going to “live there the rest of her life.” But then we’re told “Those who did not like it need not stay there”—even though neither Jane nor her mother Robin seems to have much choice in the matter.

What do you make of Jane? Lesley McDowell remarks that “Some may find this heroine, conjured up in 1937 by the author of the relentlessly cheerful Anne of Green Gables, a little too keen on being good, too.” Is Jane too virtuous? (Fanny Price, the heroine of Mansfield Park, is often accused of the same thing.)

I thought more than once of the imperious Lady Catherine de Bourgh, from Pride and Prejudice, while reading about Jane’s grandmother, Mrs. Kennedy. In the early pages of the novel, when her grandmother speaks, Jane obeys. Jane says she was “running just for the fun of it,” her grandmother says, “I wouldn’t do it again if I were you, Victoria,” and “Jane never did it again.” (How frustrating it must be to be called Victoria or Victoria Jane when you know in your heart that your real name is Jane!)

It doesn’t take long, however, for Jane to stand up to her grandmother. Unable to do so for herself right away, she can nevertheless speak up for her friend Jody when her grandmother forbids her to play with Jody, calling her “riff-raff.” “You are not fair,” Jane says, looking directly at her grandmother. I was pleased to see Jane standing up for her friend—and then a little disappointed that we don’t get to hear her grandmother’s response to this speech. The two girls just walk away.

I’ll stop there for now, and write more next week about the idyllic world Jane discovers when her father sends for her and she goes to spend the summer with him in Prince Edward Island.

I’ve posted many photos of PEI on my blog over the years, and I suppose I could search through old photos that would illustrate some of the Island’s many beauties. Maybe I’ll do that for next week’s post. Since I’m in Germany at the moment, I’ll include some photos from here instead. I like to think Jane and her father would approve, given their shared fascination with history and geography, and his promise to take her to see the world someday, including “castles on the banks of the Rhine.” I haven’t seen any castles on this trip (yet), but Bethie and I walked to the Rhine yesterday, and then we talked about Jane of Lantern Hill on the walk back to her house.

In the distance, in the photo above, “The castled crag of Drachenfels / Frowns o’er the wide and winding Rhine” (Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage).

Here’s the castle in Cochem, on the Mosel River, that we visited when I was here last fall:

I can’t resist adding some photos I took this week, of flowers and trees in springtime, plus photos of Bethie and me having “coffee with Beethoven” in the Münsterplatz:

For further reading:

“Announcing a Readalong of Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery” (on Naomi’s blog, Consumed by Ink)

“The New Mother at Home: Montgomery’s Explorations of Motherhood,” by Caroline E. Jones, in L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911 – 1942, edited by Rita Bode and Lesley D. Clement (McGill-Queen’s UP, 2015).

Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, by Mary Henley Rubio (Anchor Canada, 2008).

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. If you’d like to subscribe and receive future posts by email, you can sign up on my website, www.sarahemsley.com. Thanks for reading!

April 28, 2023

“Holding true to herself”

I’ve just finished reading Maira Kalman’s beautiful book Women Holding Things. (My friend Lisa recommended it to me, and we decided to give each other copies of the book, just as we did with Heidi L.M. Jacobs’s novel Molly of the Mall and Juliette Wells’s edition of Jane Austen’s Emma, to mention a couple of examples.) Kalman considers “all that can be held. And not held.” She says, “Holding a specific thing is a very nice thing to do. … The simple act of doing one thing.” She writes of (and illustrates) a woman “holding opinions about modern art”; of “Gertrude Stein holding true to herself writing things very few people liked or even read”; of “Hortense Cézanne holding her own”; of a woman “holding consoling and comforting her daughter”; of a girl holding a violin, a tutu, a doll and book; a woman “holding her red cap after swimming across the Hudson River”; of “women holding malicious opinions while I play piano”; of “Virginia Woolf barely holding it together”; of “Sally Hemings holding history accountable.”

She draws a portrait of her mother’s family in 1931: “They also loved holding things before half of them perished in Auschwitz.” On a page devoid of illustration or colour, Kalman writes,

The terrors of the world exist.

And we are wounded.

“It is hard work,” she says, “to hold everything.”

Another of Lisa’s recommendations is The Remarkable Journey of Coyote Sunrise, by Dan Gemeinhart, in which Coyote and her dad, Rodeo, who’ve been driving from one state to another in an old school bus named Yager, begin a journey back to Washington State for the first time in five years. Coyote is determined to dig up a memory box she and her mother and sisters buried in a park near their old house, and her dad is equally determined not to return to the place where the five of them were a family, before the two sisters and their mother were killed in a car accident. I loved reading about the bond between Coyote and Rodeo, and the tensions between the two of them, and the friendships they make with the people and animals who join them on the bus on the long drive across the country: Lester; Salvador and his mother, Esperanza; Val; a kitten named Ivan; and a goat named Gladys.

Coyote’s courage is remarkable. She’s dealing with a tremendous amount of sorrow, and she has tremendous compassion for the sufferings of others. “I guess sometimes life does seem like too much, especially during the big moments,” she says. “But usually you can dig inside yourself and find what you need. You can find what you need to grow into those big moments and make ’em yours.”

I’ve been rereading some of the short stories and plays Jane Austen wrote when she was a teenager, including “Jack & Alice,” in which we meet the Johnsons, who, “though a little addicted to the Bottle & the Dice, had many good Qualities.” I also love “The beautifull Cassandra,” in which the heroine “proceeded to a Pastry-cooks where she devoured six ices, refused to pay for them, knocked down the Pastry Cook & walked away.” I think her play “The Mystery” is hilarious—full of secrets, not one of which is ever revealed. “Shall I tell him the secret? … No, he’ll certainly blab it … But he is asleep and wont hear me … So I’ll e’en venture.” Such fun to hear the voice of young Jane!

If you’d like to hear more about Jane Austen’s early work, you might be interested in this conversation with Emma Clery on the TLS podcast (from last year): “Crossing the threshold into Jane Austen’s unpublished writings.”

I chose “Holding true to herself” as the title for this post because I liked Kalman’s description of Gertrude Stein, and because it reminded me of a favourite line from one of Jane Austen’s letters: “I must keep to my own style & go on in my own Way; And though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other” (April 1, 1816).

(The painting and the message in a bottle were created by my daughter when she was younger)

I want to recommend a couple of novels by Nova Scotia writers. First, Hold My Girl, by Charlene Carr, a gripping page-turner that explores what happens to Katherine and Tess, whose heartbreaking stories of infertility, IVF treatments, pregnancy loss, and motherhood intersect in ways neither of them could ever have imagined. After Tess endures the pain of losing her daughter Hanna, who is stillborn, and Katherine gives birth to a healthy daughter, Rose, the two women learn from the IVF clinic that their eggs were switched. As Tess begins her fight to be involved in Rose’s life and Katherine tries desperately to keep Tess away from Rose, both women struggle with profound feelings of failure.

“On the surface,” Katherine had “kept up the charade. She built her business. She kept fit, kept house, playing the role of perfect daughter, perfect daughter-in-law, and as best as she could perfect wife. Not letting anyone, even her mother, know her pain.” When Katherine’s efforts to protect her role as Rose’s mother make Tess feel like she is “nothing,” Tess longs to numb the pain. “Instead, she had to rein it all in, walk down Spring Garden Road with her head held high, gait measured, looking perfectly normal as every cell within her felt it was exploding.” This is a novel about the complexities of defining motherhood and family, but it is also about the challenges of pretending everything is fine, and the cost of keeping a secret.

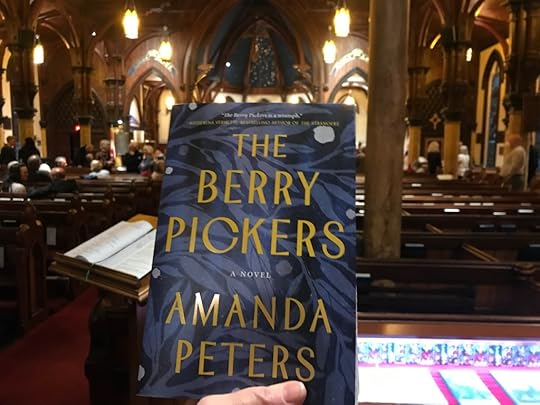

Next, The Berry Pickers, by Amanda Peters, a powerful, deeply affecting novel about family, grief, and injustice. When a Mi’kmaw couple and their children travel from Nova Scotia to Maine in the summer of 1962 to pick blueberries, their four-year-old daughter Ruthie disappears. Unable to find her, they appeal to the police for help, only to hear that there’s “nothing much we can do. She’s not been gone long enough, and you not being proper Maine citizens, and known transients.”

Ruthie’s six-year-old brother Joe was the last to see her, and he feels responsible, having wandered away from her to skip stones on the lake after the two of them had eaten their sandwiches together. When he hears other women at the camp talking about how losing a child is “the worst thing that could happen to a woman,” he begins to think he ought to have been the child who disappeared, not Ruthie. His mother has three boys and two girls. “I was the youngest boy and one that could be spared. At least that’s what I told myself that night, the firelight throwing sad shadows on the ground. It was a simple matter of math.”

The Berry Pickers asks why “no word exists for a parent who loses a child,” no word comparable to “orphan” or “widow/widower.” Perhaps “the event is just too big, too monstrous, too overwhelming for words. No word could ever describe the feeling, so we leave it unsaid.” This beautiful novel shows how the traumatic disappearance of Ruthie reverberates through the lives of every member of the family over the decades as they search for the truth.

Here are a couple of other books I heard about recently and would like to read:

The Lioness of Boston, by Emily Franklin, dramatizes the life of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Franklin says in her introduction to a reading list she put together in honour of Gardner’s Boston that “after early rejection and tragedy, Isabella might have cloistered herself away in her lovely Boston home. Instead she explored the greater world—infiltrating the male-dominated Harvard intellectual world, collecting art, and finding friends in other misfits, and her place in the larger world.”

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum:

I’m also keen to read Twice Upon a Time: Selected Stories, by L.M. Montgomery, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre. Thank you to my friend Deborah Knuth Klenck for sending me a copy of Catherine Taylor’s review of this book in the TLS, along with a beautiful card. (Having written about Shawna Lemay’s theory of the “sponge-cake model of friendship,” I now think of cards and emails from friends and family as sponge-cakes.) Lefebvre writes that the book includes “stories that, with a few exceptions, were first published in periodicals between 1898 and 1939, and that consist of early versions of well-known characters, plot points, conversations and settings in her books …. [it] seeks not only to add to the canon of known Montgomery texts but also to trouble the notion of a canon, showing the complex relationship Montgomery saw between periodical work and book publication.”

A couple of days ago, my mother and I watched an online celebration called “Poetry & the Creative Mind,” hosted by the Academy of American Poets, and we enjoyed hearing poems read by Kimiko Hahn, Malala Yousafzai, Ada Limón, and others. I especially liked hearing Ethan Hawke read W.H. Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening,” part of which he had performed in the 1995 movie Before Sunrise.

And I was glad to hear poems that were new to me, including “Why We Oppose Pockets for Women,” by Alice Duer Miller (“4. Because women are required to carry enough things as it is, without the additional burden of pockets”), and “Note to Self Work,” by Beau Sia (“beat the drum when hands / want to become fists … be a metaphor / when literal is too much … be too vibrant for lingering / on those who neglect”).

I’ll end today’s post with some photos I’ve been collecting to share with you. From my sister Bethie, a photo of “coffee with Beethoven” in Bonn:

From me, a few photos from a trip my friend Marianne and I made yesterday to St. John’s Anglican Church in Lunenburg, NS, for a wonderful chamber musical called “The Missing Pages,” by Tom Allen. It tells the story of Theodore Molt, the only Canadian who ever met Beethoven. Molt signed one of Beethoven’s conversation books—but then the next four pages were torn out. Allen imagines what might have happened between Molt and Beethoven during that visit in December of 1825. There’s another performance tonight in Halifax, at the Music Room, and I think there are still tickets available. (We also went book shopping in Lunenburg—Marianne bought a copy of The Berry Pickers, and I bought Claire Keegan’s Walk the Blue Fields.)

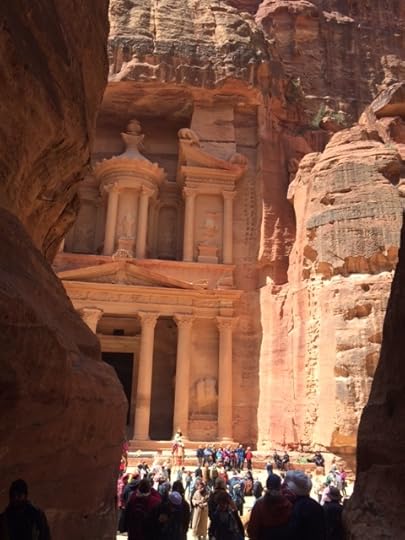

From my parents—who are always up for an adventure!—photos from their trip to Jordan earlier this month: the Temple of Artemis, the Dead Sea, Petra, and Wadi Rum.

From my friends Sheila and Hugh, photos of spring flowers in Kent, England:

And (from me) a couple of pictures of Admiralty House in Halifax, where Jane Austen’s brother Francis lived when he was Commander-in-Chief of the North American and West Indies Station of the British Royal Navy, between 1845 and 1848:

Sheila and I created a walking tour, “Austens in Halifax,” which provides more information about the years Francis and Charles Austen spent in Halifax with their families.

April 21, 2023

I Feel Sorry For My Books

My friend Susan Kerslake told me recently that she feels sorry for the books she’s bought. I asked if she’d write a guest post for my blog explaining why, and I was delighted that she said yes.

When I asked Susan for a short bio, she replied to say she’s been an author and is now a reader and pet caregiver. And she’s a vegetarian. And she turned 80 yesterday—happy birthday, Susan!!

Susan is a long-time member of the Friends of the Public Gardens in Halifax, so I thought I’d include a few photos of the Gardens at the end of this post. I took these last Saturday.

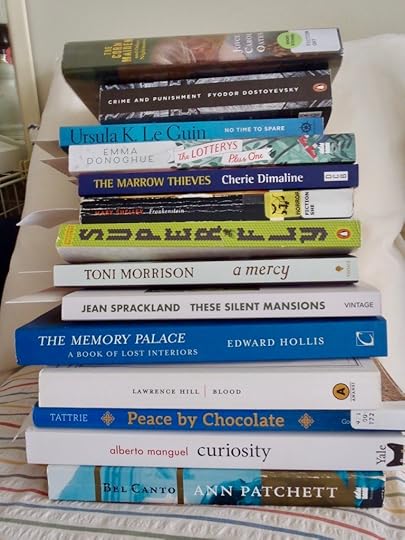

Oh woe! I lament the fate of my latest book purchase (Ursula K. Le Guin’s No Time to Spare) as I stack it on the tower of books beside the bed.

Along with:

The Lotterys Plus One (A recommendation from Lisa at Woozles after I inquired about something along the Penderwicks line.)

The Marrow Thieves (I’ve been going to lectures at the library on Environment and Literature, and this was suggested by the professor, Renee Hulan).

Frankenstein (Renee read us a paragraph or two in class, and I found a copy on the free shelf at the library!)

Superfly (Which is indeed about flies.)

A Mercy (On sale at Bookmark, on the charity bookcase.)

These Silent Mansions (A woman’s meandering and pondering on cemeteries in England.)

The Memory Palace: A Book of Lost Interiors (This guy is fantastic: Edward Hollis. A follow up to The Secret Lives of Buildings.)

Blood

Peace by Chocolate: The Hadhad Family’s Remarkable Journey from Syria to Canada

Curiosity

Bel Canto

And Crime and Punishment. (And what, you ask, would Crime and Punishment be doing there, but I was supposed to be reading it with a friend in BC. That petered out.)

Though sprouting bookmarks all, they are in medias res.

And what of The Corn Maiden by Joyce Carol Oates, whose sheer bolt of energy in her writing is a spur. That book, almost finished, because, you guessed it, it is a library book and due next week.

April 14, 2023

“Old Rusty Metal Things”

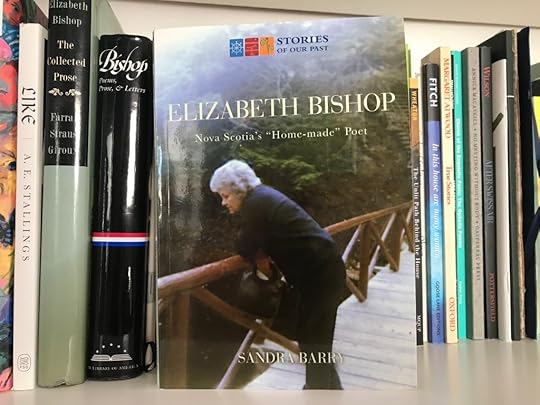

Today I’m delighted to share a poem by my friend Sandra Barry, entitled “Old Rusty Metal Things.” Sandra is a poet and freelance editor and an Elizabeth Bishop scholar. She’s the author of a wonderful book called Elizabeth Bishop: Nova Scotia’s “Home-Made” Poet, which was published by Nimbus in 2011, the centenary of Bishop’s birth.

Elizabeth Bishop went to stay in Great Village, Nova Scotia in 1915, and she continued to live there with her grandparents after her mother, Gertrude, was hospitalized for depression at the Nova Scotia Hospital in 1916. In the fall of 1917, when Elizabeth was six years old, her grandparents took her back to live in Worcester, Massachusetts, where she had been born. She never saw her mother again, even though Gertrude lived at the hospital until her death in 1934.

Over the years, Bishop made many trips to Nova Scotia and wrote about the place and her experiences here in both poetry and prose. As Sandra says in her book, she “referred to herself as 3/4ths Canadian, as American, as a New Englander, as a ‘herring-choker-bluenoser.’” Robert Lowell described her as “Half New Englander, half fugitive, / Nova Scotian, wholly Atlantic sea-board.”

“Home-made, home-made! But aren’t we all?” Bishop wrote in “Crusoe in England.” “As important as her formal education, world travel, and poet friends were to her artistic development, Elizabeth’s childhood in Great Village and her mother’s family were her earliest and life-long influences,” Sandra says in her book. “Her grandparents’ house in the village was a home-made world,” she adds, saying that Bishop “maintained a deep respect and admiration for this time and place and these people her whole life.”

If you’re interested, you can listen to Elizabeth Bishop reading her poem “Crusoe in England,” recorded on April 14, 1974 at the Coolidge Auditorium at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

Sandra’s dedication to Bishop’s life and work is truly extraordinary. She co-founded the Elizabeth Bishop Society of Nova Scotia, spent a decade as the administrator of the Elizabeth Bishop House in Great Village, and posts regularly on the Elizabeth Bishop Centenary blog.

I first met Sandra at the Women’s Council House in Halifax in 2011, after she had given a reading from her book about Bishop, and a few years later, I spent a lovely afternoon with her in Great Village at the Elizabeth Bishop House. I took many photos on that trip, and I’ve been thinking of putting together a collection of them for a future blog post.

It’s a great pleasure to introduce “Old Rusty Metal Things,” which Sandra wrote some years ago after she had visited an old barn in Great Village with her friend Roxanne. Many thanks to Sandra for the poem and to Roxanne for the photo of the barn, which belonged to Logan Spencer.

Sandra writes that “One day years ago, the photographer Roxanne Smith asked me if I knew of any place in Great Village where she could photograph ‘old rusty metal things’—those were her exact words. I instantly thought of Logan’s barn—so we met at the EB House one day and went across the road and asked Logan if we could have a look. What a place it was—it has long since been dismantled—but the barn was ancient—well over 100 years old. I was so taken with the experience of just walking through this space and looking at everything, this funny little poem came out. Alas, the barn is itself a ghost now.” She says Logan is now “heading toward 90 and still out in his field. He was out there nearly every day during our visit to the EB House last August—we would sit on the verandah and watch him work clearing away alders and other brush from along a fence line at one side of his pasture by the river. We were simply in awe of him. He never hurried—just worked slowly and methodically—and he accomplished so much.”

Here’s a photo of Sandra by her sister, Brenda Barry, taken on the veranda of the Elizabeth Bishop House last summer. The house, she says, is “just a stone’s throw from where Logan’s barn used to be.” The photos that follow the poem are also by Brenda.

Old Rusty Metal Things

for Logan Spencer

The barn was built. Moved. Rebuilt.

Weather aged its wood grey as stone.

It has stood for a century.

Filled with old rusty metal things.

Tractors. Tools. Sleds. Pumps.

Anchors. Chains. Scythes. Shoes.

The stalls and chutes are shadows.

The loft a cavernous home

for countless pigeons.

The ghost of hay haunts the rafters.

Ladders climb nowhere; lie buried

beneath thick earthy odors.

Doors and windows crusted;

corners veiled with cobwebs.

In its heyday the barn was a hive.

It was alive with life and death,

a hinge of hard work and injury,

an axle of ancestral habit.

Now it is an ark afloat

on its own stories and waist-high

meadow grasses.

The barn is a mind

holding its own collapse

in a strange suspension.

It has forgotten nothing.

It knows it will disappear.

The empty space left to the air

a silent echo in the sun and rain.

Returned to the elements

the barn is homage to the world,

the word, to the whole of what

can be and not be known.

Red-winged Blackbird

Evening Grosbeak

Snowdrops

April 7, 2023

“A glint of silver-blue”

I’ve admired the poetry of A.E. Stallings ever since my parents gave me a copy of her book Like, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2019. I love the opening lines of “After a Greek Proverb,” which also appears in her new collection, This Afterlife:

We’re here for the time being, I answer to the query—

Just for a couple of years, we said, a dozen years back.

Nothing is more permanent than the temporary.

The preoccupation with what is temporary and what lasts continues in “Glitter”:

You have a daughter now. It’s everywhere.

And often in the company of glue.

You can’t get rid of it. It’s in her hair:

A wink of pink, a glint of silver-blue.

It’s catching, like chicken pox, or lice.

(The epigraph to this poem is a quotation from British Vogue: “All that will remain after an apocalypse is glitter.”)

The ordinary challenges of modern life—trying to clean up glitter; hunting for a lost piece of Lego—appear in these poems alongside big questions about time, memory, life, and death. “You can’t go back,” we read in “Burned.” “Although you scrape the ruined toast, / You can’t go back.” Just as “The butter cannot be unchurned,” “You cannot unburn what is burned.” Even the parent reading “Another Bedtime Story” has to face the fact that

The tales that start with once and end with ever after,

All, all of the stories are about going to bed,

About coming to terms with the night, alleviating the dread

Of laying the body down, of lying under a cover.

My sister Bethie sent me a photo of her copy of This Afterlife.

Stallings’s “First Miracle,” with its focus on what the body can bear, made me think of the ending of my friend Margo Wheaton’s poem “Seeing Me Home,” in The Unlit Path Behind the House:

This is just the pain

in living, impossible to bear

and bodies, bearing it.

Stallings writes, “Her body like a pomegranate torn / Wide open, somehow bears what must be born.”

I couldn’t find my copy of The Unlit Path Behind the House (I realized later I had lent it to friends), and when I asked Bethie if she’d take a photo of her copy, she sent me this picture of the book on the path behind her house in Bonn.

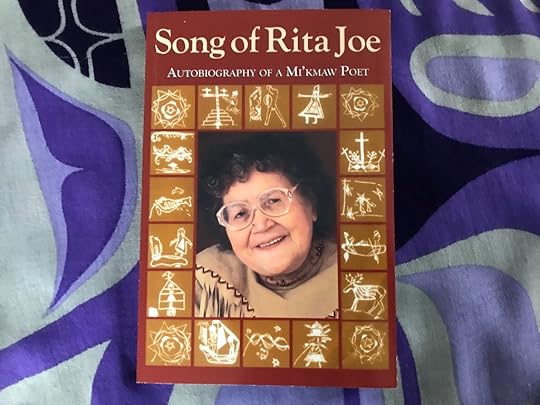

For Poetry Month, I’ve also been reading poems by Rita Joe, whose book Song of Rita Joe: Autobiography of a Mi’kmaw Poet I mentioned here a couple of weeks ago. In Song of Eskasoni, she speaks of

Listening to old folks telling stories

Of long ago, when the earth was young.

Their deeds woven into history

in Eskasoni, near mountains, waters and trees.

In an untitled poem, #14, from We Are the Dreamers, she says

Our home is this country

Across the windswept hills

With snow on fields.

The cold air.

Before the pandemic, I went to a launch for two picture books, one featuring Rita Joe’s poem I Lost My Talk, and the other featuring a response by Rebecca Thomas, former Poet Laureate of Halifax, entitled I’m Finding My Talk. In Joe’s poem, she speaks of how her “talk” was taken away from her “When I was a little girl / At Shubenacadie school.” Her daughter Ann Joe says Joe “used to say writing was her therapy. She had a lot of painful memories and she had to get them out. She became a writer because she wasn’t allowed to write. The more they tried to break her will, the more she went her own way.” The poem acknowledges the enormity of what was taken from her and from other students at residential schools, and ends with hope:

So gently I offer my hand and ask,

Let me find my talk

So I can teach you about me.

Thomas’s poem is similarly hopeful:

I’m finding my talk

One word at a time.

Kwe

Wela’lin

Nmultes

Another Nova Scotia poet I admire is Budge Wilson, author of the beloved and bestselling prequel to Anne of Green Gables entitled Before Green Gables. In that book, she accomplished something truly extraordinary: even though pretty much every reader knows it will end with young Anne Shirley arriving at Green Gables for the first time, Budge created a story full of suspense, right up until the moment when Anne leaves Nova Scotia for Prince Edward Island on the ferry. “Bewitched by the limitless expanse of sea, the galloping whitecaps, the wheeling gulls, the smell of salt and seaweed,” Anne thinks, “This is what I’ve been waiting for my whole life.”

Over the course of her career, Budge published many stories and novels for readers young and old. Her first book, The Best/Worst Christmas Present Ever, was published when she was 56, and her first book of poetry, After Swissair, was published when she was 88.

The rocks at Peggy’s Cove are often chilly

even in the midsummer sun

In the black of that September night

and in the awful dawn

they were as cold as death

and unforgiving.

The cover of the book features a quilt by Barb Robson entitled “Sea Change,” which was inspired by Budge’s observation that a sea change had taken place in the community in the area near the spot where Swissair Flight 111 went down on September 2, 1998.

Last weekend, on a rainy Saturday afternoon, I turned to poems by Mikko Harvey, an old family friend—well, he isn’t old, but our family connections go back a long time—who lives in Western Massachusetts and has published two books: Unstable Neighbourhood Rabbit and Let the World Have You. Jim Nason writes in a review of the former that “Harvey’s ability to make normal situations new and strange is one of his greatest talents. Combining metaphor in equal amounts with a distraught psyche that’s allowed to freefall, he heightens and liberates language.”

Two of my favourite poems from Unstable Neighbourhood Rabbit are “Swivel”—“Sometimes, I spend the whole morning searching / for the morning”—and “Intimacy”—“So introduce me / to your friends: I promise to wear my best face.”

Here’s a link to a photo essay by Mikko, of things and places that inspired him when he was writing Unstable Neighbourhood Rabbit, including The Moomins, a basketball court in Columbus, Ohio, and a giant sandpit in Johannislund, Finland—“an archetypal place of play and wonder.”

In Let the World Have You, I especially like “Personhood”: “I regret / 96% of my backward glances, / but to regret is to glance backward, / and thus we proceed toward 97.” And “Secret Channel,” which begins:

When you realize you are only a subplot

in the story the day is telling, you are

devastated; it would have been better

to be everything or else nothing.

“For M,” which is included in Let the World Have You, went viral last year. Part of the poem appears on the back cover:

My husband and daughter were in Boston recently, and I’m going to include a few photos from their trip in this post, because over the years we’ve spent a lot of time with Mikko and his family in Boston and Cambridge.

I enjoyed reading this list of “30 Ways to Celebrate National Poetry Month,” from the Academy of American Poets. I’ve signed up for “Poem-a-Day,” which is curated in April by U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón. I liked the suggestion about reading and sharing poems about the environment in honor of Earth Day, and it was a lovely surprise to find that one of the poems on their list of Poems About Climate Change is by Mikko. “The Poem Grace Interrupted” begins, “There once was a planet who was both / sick and beautiful.”

I read several of the poems on the list, and one of my favourites was Catherine Pierce’s poem “High Dangerous”:

is what my sons call the flowers—

purple, white, electric blue—

pom-pomming bushes all along

the beach town streets.

I can’t correct them into

hydrangeas, or I won’t. …

The League of Canadian Poets also has a list of ideas for celebrating Poetry Month, including sharing a poem on social media using the hashtag #todayspoem. I like their promise at the end of the list that “there’s a poem just for you, and we know someone wants to help you find it.”

One of my recent discoveries was a splendid new poem by my friend and neighbour Brian Bartlett. (Thank you to Sandra for telling me about it and Brian for sharing a copy.) “Bishop’s Hues” was published in the Winter 2023 edition of Riddle Fence. The poem looks at two photos of a collage by Elizabeth Bishop, along with vivid phrases from her poems, including “white-gold skies,” “silver and silver-gilt,” “bright violet-blue.” Like the Stallings poems I quoted earlier, “Bishop’s Hues” focuses on change and loss:

The blue of the Blue Morpho

fades, sky-tinge left only

in one wing’s half, earth-brown

replacing the namesake hue.

Though the blue of the butterfly is “diminished,” Bishop’s words are alive and in constant motion: “Rereading after rereading, / her lines rise, veer, skim and tilt.”

I love seeing crocuses and snowdrops at this time of year in Nova Scotia. As a kind of tribute to the vibrant purple crocuses in my neighbourhood, here’s a quotation from a picture book I’ve loved for years. This is from Mabel Murple, by Sheree Fitch, another Nova Scotia writer, whose work for both adults and children captures the sorrows and joys of life with wisdom, humour, and a profound understanding of the power of the imagination.

what if …

EVERYTHING was purple

I mean a WHOLE PURPLE WORLD

And there was someone just like me

I mean a purple sort of girl

And if …

There was a purple girl

How purple could she be?

Would she get in purple trouble?

(She would if she were me!)

I’ve long thought that Mabel Murple and Jane Austen’s “Beautifull Cassandra” are kindred spirits, but that’s a story for another day….

These crocuses are so tiny that I almost stepped on them when I got out of the car. Thank goodness I spotted them in time.

I return often to Sheree’s collection of poetry for adults In This House Are Many Women, especially the words of “When Atmospheric Conditions Permit,” which opens with “Siren sounds” that “swirl” and “scream,” making it difficult to sing a lullaby. “There’s so much love but the world’s gone wild.” Even so:

I pray

by the light of the moon

you find a way to make

a kaleidoscope

that from bits of shattered glass you’ll keep creating some

things beautiful.

I’ll close with a link to a tour of the beautiful garden at Lake House in Norfolk, England, full of bluebells, light blue periwinkle, and other April flowers. This is from a blog I’ve followed for several years, called “The Garden Gate Is Open.”

Happy Spring, and happy Poetry Month!

March 31, 2023

What is Said and What is Not Said

Jill MacLean is the author of today’s guest blog post, and I’m delighted to introduce her. She’s chosen to write about three books she admires and would like to recommend: Small Things Like These, by Claire Keegan, and Summerwater and Names for the Sea: Strangers in Iceland, both by Sarah Moss. This short essay is part of an informal series in which I ask friends to write about what they’ve read recently, and/or books they return to again and again. The first post in the series was by Naomi MacKinnon, who wrote about “Reading Close to Home.”

Jill is an award-winning author who has published five contemporary novels for middle-graders and young adults. Nix Minus One, a YA novel that won the Ann Connor Brimer Award for Children’s Literature, is a particular favourite of mine—a brilliant and heartbreaking book. Written in free verse, the novel explores the complex relationship between quiet fifteen-year-old Nix and his older sister Roxy as her life spirals out of control.

Jill is an avid gardener and canoeist and she lives in Nova Scotia near her family. After a period of writing for younger readers, she says that “to avoid the risk of falling into a literary rut,” she had adult readers in mind when she started to explore her “longtime fascination with the medieval period.” She was born in Berkshire, England, the setting for her new novel, The Arrows of Mercy , which has just been published, and is available from Bookmark Halifax (and from other online sources, including Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org). She writes that revisiting Berkshire—“in reality in the 21st Century and in imagination in the 14th”—has given her “much pleasure.”

I’m excited about the opportunity to return to the medieval period by reading The Arrows of Mercy. (Some of you may know that before I started writing about Jane Austen, I wrote an MA thesis on Middle English marriage poetry.)

Anne Simpson, winner of the 2021 Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award for her novel Speechless, calls The Arrows of Mercy “richly imagined and compellingly realized,” and says that the novel “draws the reader into a story of the past that is imbued with the urgency and immediacy of our own time.”

If you’d like to hear more about The Arrows of Mercy, you can sign up for Jill’s mailing list. The Halifax launch is on Sunday, April 16th, from 4-5:30pm at the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia (1113 Marginal Road, Halifax, NS).

Please join me in welcoming Jill!

One of my criteria when I read is whether the book inspires me to become a better writer by sharpening my technical abilities and my imagination. There is a cost to this mindset. Because my inner editor is so active, I’m halted by the perfection of a sentence, by a surprise in the narrative, by a conclusion open enough to match our own open lives but satisfying in terms of all that has gone before. I am, to use John Gardner’s phrase, pulled out of the fictional dream.

I therefore crave stories that immerse me and sweep me along, silencing that nagging editorial voice. Claire Keegan’s novel, Small Things Like These, which was shortlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize, is one of those stories. The novel itself is short, 114 pages. I’ve read it twice. I wish I could write with such economy and truth, that I could mingle so wisely what is said and what is not said. It is a quiet book, without a hint of melodrama, yet it takes on the enormous subject of the Magdalene laundries in Ireland, the last of which did not close until 1996. These institutions were responsible for countless deaths and for the ruination of thousands of “fallen” women’s lives—all at the linked hands of Catholic Church and Irish State. I cannot help thinking of our residential schools.

The protagonist, Bill Furlong, is himself illegitimate, he and his mother saved from the local convent’s laundry by a kindly, non-judgmental Protestant woman. He is now a man nearing forty, a coal and timber merchant in this small Irish town on the banks of a river “the colour of stout”: a town that has fallen on hard times, for these are the Thatcher years. He, his wife and five daughters attend the Catholic Church and his girls are all doing well at the Catholic school. On the other side of that school’s wall is the convent, its walls topped with broken glass, its doors padlocked, its windows metal-barred and blackened.

From the first paragraph I am in the hands of a wordsmith with an acute eye for detail. I am snagged by rosary, Angelus bell, Moses basket: religion still has power in this town, as do drunkenness, bullying, gossip, unemployment and poverty. A schoolboy drinks milk from a cat’s dish behind the priest’s house, another boy scavenges for sticks for the fire, and Furlong knows how easy it would be to lose everything, all too aware that he and his wife, although working from dawn to bedtime, are not getting ahead, and perhaps never will. A masterly paragraph about his earliest memories culminates in the two-toned, tiled floor like “a draughts board whose pieces either jumped over others or were taken.” What better metaphor for a society subjected to unleashed capitalism?

And what, he wonders, is it all for?

Tension gathers as December darkness drapes the town, a darkness unleavened by the lighting of the manger scene with its Virgin Mother. Virgin. The word resonates. Scenes are vividly evoked, like the making and baking of the Furlong family’s Christmas cake, poked with a knitting needle to see if it is done; the loan of a kettle to melt the frozen padlock on Furlong’s yard on a bitter morning when he feels “the strain of being alive”; the ever-watchful, often spiteful congregation shuffling on their benches as the purple-robed priest swings up the aisle; ill-nourished convent girls on their knees on the chapel floor polishing “their hearts out,” looking “scalded” when they catch sight of the coal merchant watching them from the shadows.

Furlong is a reflective man who has little time to reflect, yet whose insights constantly nudge him. “Was it possible to carry on through all the years, the decades, through an entire life, without once being brave enough to go against what was there?” And therein lies the crux of this novel, the conflict between “the ordinary part of him” that needs to stay on the good side of people and look after his beloved daughters, and his deeply held, contrary and powerful need to do right. Inadvertently at first, then purposely, he breaches the convent’s walls and is brought face to face with himself—as man, as husband and father, as Christian.

Do we have a duty towards those of our neighbours who have drawn the short straw? Do we inure ourselves to their fate or do we act? Do we, like Furlong, ponder small things like these?

Sarah Moss is a British writer I came across when her novel Summerwater was chosen by my book club. At the end of a ten-mile single-track road in Scotland is a group of rented cabins, where twelve families on summer holidays are trapped by horrendous rains. The twelve main sections in the novel, each told from a different point of view, are subtly interconnected. The atmosphere is one of foreboding—and having read Ghost Wall and The Fell, I can attest that Moss does foreboding in spades. Characters spring from the pages, revealing themselves from the inside out; the stress points of relationships emerge; surveillance through the cabins’ windows progresses from curious to judgmental, from hostile to enraged. How does Moss resolve the tension she has created? To some extent—discussion was lively at book club!—you will have to decide that for yourself.

I’ve also read Moss’s memoir, Names for the Sea: Strangers in Iceland, about the year she and her family spent in Reykjavik while she was teaching 19th century British literature at the National University. They arrive in 2009, just after the financial collapse. She feels like a foreigner. She is terrified of the way Icelanders drive their massive SUVs. She is slow to make friends. But gradually she delves below the surface of a country encrusted in lava, its inhabitants supposedly non-hierarchical, poverty-free and crime-free, a country of elves and knitting, of eruptions and boiling mud and fierce storms at sea. A country with a revisionist history, a country that, despite its swaths of emptiness, has its share of corruption, complications and contradictions. Sarah Moss has her own contradictions: a critically acclaimed author who believes herself inadequate to join a local writing group; a protective mother who has to adjust to Icelandic parents’ more casual—frighteningly casual—attitudes; a highly intelligent woman who feels stupid faced with (possibly) xenophobic bureaucrats. Yet she does delve, and effectively so. I admire her curiosity and, yes, her intelligence, her balanced judgements (the exception: Icelandic drivers), her courage in seeking out difficult conversations, and her lively sense of humour.

Her novel Night Waking, according to a friend of mine who has read both books, has some interesting parallels to that year in Iceland. I can’t wait to read it.

March 24, 2023

“The writing of sponge-cakes”

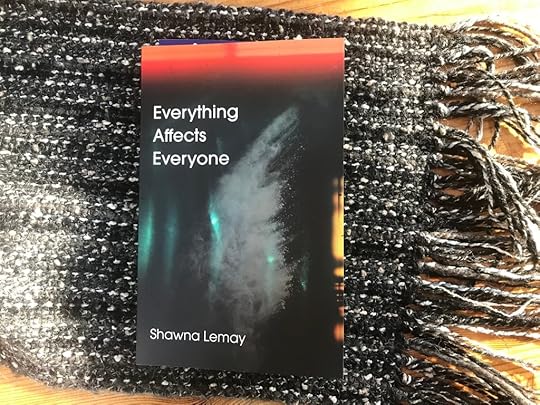

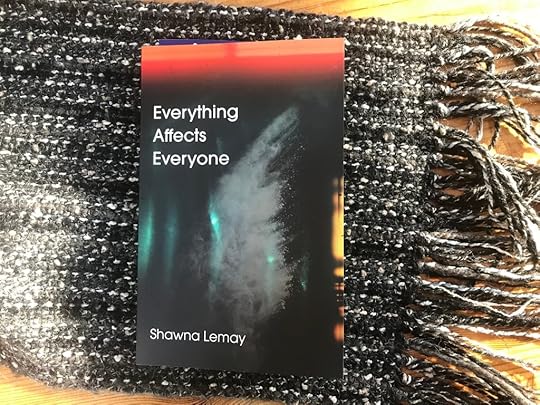

“I’m that person who finds the purchase of a sponge-cake to be delightful.” I’m quoting Shawna Lemay, whose novel Everything Affects Everyone I wrote about last Friday. I enjoyed the novel so much that I’ve been reading more of her work, including some of her poems, and a splendid essay I remembered from a few years ago, called “The Sponge-Cake Model of Friendship.”

“You know how interesting the purchase of a sponge-cake is to me,” Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra on June 17, 1808.

Shawna says, “I find it diverting to know what my friends had for breakfast, where they hope to holiday, that they enjoyed a scone with plum jam, a piece of chocolate cake, or sour cherry pie, or that they purchased a new scarf. Friendship is in the details, I’ve discovered.” She writes of Jane and Cassandra that “The two sisters were often enough separated, and it’s the writing of sponge-cakes to each other that comforts, that makes each feel less alone.”

She considers other types of friendship before returning to “the Jane and Cassandra model,” which is “one of mutual interestedness,” and concluding that this is her “only requirement in friendship.”

You can find details about Shawna’s other books on her website. I remember that I loved her novel Rumi and the Red Handbag (and not just because Jane Austen’s line about sponge-cakes makes an appearance in the book, or because it includes a character who follows the careers of stars who’ve appeared in movie adaptations of Austen’s novels: “I want to see if they go on being anything like the characters they portrayed. … I keep lists on them, she said,—see, Ciaran Hinds, Colin Firth, Jeremy Northam, Hugh Grant, Jonny Lee Miller, especially him. Really, I’d like to make a movie with just them and scratch the heroines, you know? A movie about their lives after Austen, a documentary.”)

I also recommend Shawna’s collection of short essays entitled The Flower Can Always Be Changing—the title is a quotation from Virginia Woolf—and I’m a long-time fan of her blog, Transactions with Beauty.

Letters and FaceTime calls have been a comfort to my sister Bethie and me during the years that she and her family have lived on the other side of the Atlantic. I’m pretty sure she’d agree with me that, to borrow Shawna’s words, “the simple daily pleasure of just delighting in each other’s ordinary lives is and has been magnificently sustaining.” We often send photos of our children, or trees and flowers, or the books we’re reading.

Or cake! My daughter likes to make and decorate cakes: one of last year’s creations was a Ron Weasley cake for one of her younger cousins; this year she’s been hired to design an Anne of Green Gables cake for one of our friends. Bethie has (in my opinion) perfected the art of making gluten-free birthday cakes, including carrot cake with cream cheese icing and ginger cake with a chocolate glaze and sprinkles. She and I also exchange books. Or other small presents—this week, for example, I sent her a Squishmallow avocado. Not nearly as elegant as an Austenian sponge-cake, but still a source of amusement and comfort for both of us. (As it happens, the label says the avocado’s name is “Austin,” though that isn’t why I bought it.)

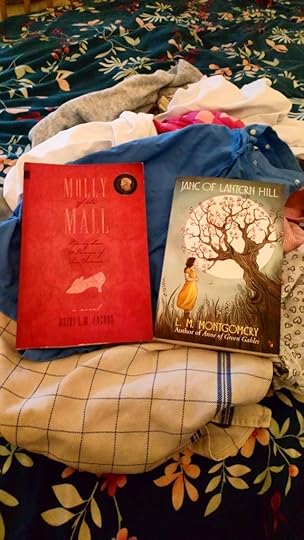

After I wrote earlier this month about how much I loved Heidi L.M. Jacobs’s novel Molly of the Mall, and about my plan to read L.M. Montgomery’s Jane of Lantern Hill in May, Bethie decided to order copies of both novels, and when they arrived, she sent me a photo with this note: “Inspired by the way you photograph books on top of lovely scarves, I have artfully arranged these on top of this pile of unfolded laundry : )”

Bethie and I have also corresponded recently about the news that Ann Napolitano’s new novel, Hello Beautiful, has been chosen for Oprah’s book club, and about an essay Napolitano wrote for the New York Times a few years ago, in which she talks about letters she’s written to her future self. “I wrote the first letter when I was 14,” she says, “and I stole the idea from a novel.” I bet many of you will know which novel she’s talking about.

In L.M. Montgomery’s Emily Climbs, Emily Starr writes a letter on May 19th, 19 – :

This is my birthday. I am fourteen years old today. I wrote a letter “From myself at fourteen to myself at twenty-four,” and sealed it up and put it away in my cupboard, to be opened on my twenty-fourth birthday. I made some predictions in it. I wonder if they will come to pass when I open it.

Napolitano says, “the idea of the letter delighted me. It was a grand gesture, yet of the kind an introverted kid could make alone, with no one noticing. I described the current state of my life and listed my hopes and dreams for myself 10 years later.”

Were any of you inspired to do something similar after reading Emily Climbs? I was. I wrote, “To 19 from 9. Have you written your great book yet?” My goal at the time was to write and publish my first book within the next few years, following in the footsteps of Gordon Korman, who wrote This Can’t Be Happening at Macdonald Hall when he was 12, and signed a contract to publish it with Scholastic when he was 13.

That was a lot of pressure for a nine-year-old to put on her future self! Fortunately, that letter also said, “Please be kind 19. Love 9.” I hope my nine-year-old self would be pleased to know that I’ve published five books in the three decades since I turned 19. (I don’t know whether she’d think they’re “great” or not.)

Bethie also wrote a letter to her future self—and I don’t think either of us knew the other had done this until we started talking about Ann Napolitano’s essay.

When I was searching for the photos I took at the Carol Shields Memorial Labyrinth, to include in last week’s blog post, I also came across a couple of photos of the Bookmark plaque for Shields’s novel The Republic of Love, which my family and I visited on that same trip to Winnipeg in 2016. (Actually, it was a drive from Halifax to Vancouver and home again, with a stop in Winnipeg on the way out west. The post featuring photos from that road trip across Canada and back through the United States continues to be one of the most popular on my blog.)

For the past eight or nine years, I’ve been volunteering with Project Bookmark Canada, to help choose passages from fiction and poetry set in specific places, which can be marked with a Bookmark plaque. Most of the time, other kinds of plaques commemorate sites where real events happened. What I love about Bookmark plaques is that they mark sites where the things that “happened” are in the imagination of the writer, and then of the reader.

Our local Nova Scotia Reading Circle for Project Bookmark has organized events in Halifax to celebrate the unveiling of a Bookmark in Port Hastings, NS, for Alistair MacLeod’s extraordinary novel No Great Mischief (which won the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2001), and for the unveiling of a Bookmark plaque in Cavendish, PEI, for L.M. Montgomery’s poem “The Gable Window.”

I stopped to take pictures of lupines when I was on my way to the unveiling of the Bookmark for “The Gable Window” in June of 2018.

I took another picture of the Montgomery Bookmark in October of 2019, when I was in PEI for a wedding.

I was delighted to visit the Bookmark for The Republic of Love, which is at “the bus shelter at River and Osborne” where Shields’s heroine Fay sometimes “wait[s] anonymously” and sometimes “run[s] into any number of acquaintances.” In Winnipeg, “You were always running into someone you’ve gone to school with or someone whose uncle worked with someone else’s father. The tentacles of connection were long, complex, and full of the bitter or amusing ironies that characterize blood families.” While some find the connections oppressive, “Fay again and again is reassured and comforted to be part of a knowable network.”

(I have to confess here that I haven’t yet visited the No Great Mischief Bookmark, even though I love that novel and the Bookmark is in my own province. Someday!)

I want to add a few more things to this week’s scrapbook. First, a link to a CBC Radio documentary about the recent celebration of Mi’kmaq Poet Laureate Rita Joe at the Halifax Central Library and the Millbrook Cultural Centre, organized by the Afterwords Literary Festival and hosted by Mercedes Peters. I attended the event at the Central Library last month, and I enjoyed the readings and music, which were by Tiffany Morris, Danica Roache, and Raymond Sewell.

Rita Joe writes in her autobiography, Song of Rita Joe, that “I have said again and again that our history would be different if it had been expressed by us.” She tells her readers that “Being strangers in our own land is a sad story, but, if we can speak, we may turn this story around.”

I loved hearing Raymond Sewell speak in the documentary about how his father, “a respected elder in the area, was always telling us ‘Rita Joe said we’re from the land of the dreamers, we’re a dreaming people, be creative.’ We were all dreaming at home, there was an endless supply of art supplies at home, so some people were drawing, some people were making music in the basement. My father always had instruments around, my mother always had instruments around that we could play. We’ve always had a need to carry on stories.”

Rita Joe was the 2023 honouree for Nova Scotia Heritage Day, and if you’d like to read more about her life and her poetry, you can find out more in this blog post from Halifax Public Libraries.

Next, I want to tell you about this lovely survey of marginalia over the years, by Jillian Hess: “Marginalia: 5 Ways to Write in Your Books.” She gives examples from 1300 to 2022, including the symbols used by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, comments both positive and negative recorded by medieval readers (“Thys ys a Good Boke Amen”; “Whoever translated these Gospels, did a very poor job”), and photos of conversations among different readers.

Do you write in your books? I do. I could write more on this topic, but maybe I’ll save it for another day.

I also want to include a few of Brenda Barry’s photos, this time from Margaretsville, Nova Scotia—the wharf and lighthouse, a chickadee, and Isle Haute—sent to me by her sister Sandra, who writes that the lighthouse reminds her of the one in Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “Seascape.” Sandra says the lighthouse in the poem is “severe,” while “the one in Margaretsville seems more cheerful,” but Bishop’s “description echoes this one.”

… a skeletal lighthouse standing there

in black and white clerical dress,

who lives on his nerves, thinks he knows better.

He thinks that hell rages below his iron feet,

that that is why the shallow water is so warm,

and he knows that heaven is not like this.

I’m grateful to Sandra and Brenda for the wonderful letters and photos (sponge-cakes!!) they send, and for giving me permission to share these images with you here.

An exhibition entitled “My dear Cassandra…” opened earlier this week at Jane Austen’s House Museum, and it includes a recently acquired letter from Jane to Cassandra, dated October 27-28, 1798. Jane begins by saying, “Your letter was a most agreable surprize to me to day, & I have taken a long sheet of paper to shew my Gratitude.” She speaks of her mother’s illness and her new role in managing the household:

I am very grand indeed; I had the dignity of dropping out my mother’s Laudanum last night, I carry about the keys of the Wine & Closet; & twice since I began this letter, have had orders to give in the Kitchen: Our dinner was very good yesterday, & the Chicken boiled perfectly tender; therefore I shall not be obliged to dismiss Nanny on that account.

This is also the letter in which she tells Cassandra the news that “Mrs Hall of Sherbourn was brought to bed yesterday of a dead child, some weeks before she expected, oweing to a fright,” and makes the uncharitable and now infamous remark that “I suppose she happened unawares to look at her husband.”

“Newly Acquired Austen Letter on Display”

“Rare early letter from Jane Austen to her sister will go on public display”

I’ll end with a recent photo of the view from the café on the top floor of our beloved Halifax Central Library, and a photo of snowdrops in yesterday afternoon’s snow.

Thank you, as always, for reading.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider forwarding it to a friend and/or joining the conversation in the comments.

You can also find me on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads. I’ve had an Instagram account for years, though I haven’t yet posted anything—not sure why, since I love sharing photos and seeing what friends have posted. Come and find me there, too, if you’re so inclined.

March 17, 2023

“Secrets that everyone knows”

“Reality is full of secrets that everyone knows and refuses to acknowledge,” says Xaviere in Shawna Lemay’s novel Everything Affects Everyone. I had been reading the book earlier this month (as I mentioned here a couple of weeks ago), and I was reading slowly, savouring lines like this one and copying out quotations I wanted to remember.

In an interview with Xaviere’s friend Daphne, the photographer Irene Guernsey speaks about creating art: “There is above all a sacredness in creating something from nothing.” She says, “Art, itself, can bear quite a lot, and it can be enough, or close to enough.” It can be made in “isolated spots.” It doesn’t necessarily have to be noticed. The artist has to “be able to feel, to let things in.” And yet “The world is always at odds with the artist,” and “Maybe it has to be that way.” I liked finding Rilke in this novel: “You must change your life,” he says, and the women of Everything Affects Everyone recognize that they are all engaged in a process of transformation, as they work to understand the mysteries of art.

As I say, I had been reading the novel slowly, and then, last Friday, after I received news of the death of a family friend, someone I had known and loved all my life, I struggled to make sense of the shock and one of the first things I did was to curl up with Shawna’s novel and read the rest of it all at once. I suppose in a way I was trying to find out how this thing that had happened would affect all of us, everyone. Each loss is unique, of course, and yet all of us experience loss again and again, as we lose people we love, dreams we once cherished, visions of what might have been.

The Carol Shields Memorial Labyrinth in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which my family and I visited on a warm, sunny morning in late June of 2016 with our dear friend, who had lived in Winnipeg for many years.

Reading didn’t take away the pain, though I don’t think that’s the effect I was searching for. Like Xaviere, I felt I was learning that “I’m meant to breathe and live, and beyond that, I’m meant to appreciate the beauty of things in a heightened way.” I went looking for photos of the friend we had lost, and I found one—the last photo of her that I took during what turned out to be her last visit to Halifax—in which she is laughing, during a conversation with one of my aunts, and I could almost hear that familiar laugh. For a moment, she was with us again.

Quotations from Carol Shields

I won’t try to summarize the plot of Shawna’s beautiful novel. Indeed, as Xaviere says, her life “is to be without plot.” Things do happen in this book: transformation—even transfiguration—and theft, and reconciliation. But the plot isn’t the main point. A photograph stolen from an exhibition in Edmonton, Alberta called Snow Angels, Forgotten Angels, and Winged Beings is linked with the artworks stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston on March 18, 1990. Something about the empty frames that mark the locations of the crimes prompts people to talk about other things that have been stolen or lost.

The courtyard at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, which I visited often during the years I lived in Boston and Cambridge. These photos are from a family holiday in 2017, several years after we had moved back to Canada. We spent a week with my sister Bethie and her family, just before they moved from Boston to Bonn.

Everything Affects Everyone draws attention to “the sense that there are no endings.” Beyond the “traditional narrative arc,” says a character named Michelangelo Dupree near the end of the novel, “There is an ongoingness that I wish to capture.” And maybe that’s the word I was looking for when I read Shawna’s book last Friday afternoon: ongoingness.

I often find myself quoting Aristotle, who says in the Nicomachean Ethics that “The things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them.” I heard an echo of this idea in Xaviere’s claim that “I need to know things that I will only learn by knowing them.” Practice. Education. Creativity. All of us know secrets about loss. Sometimes we can look at them and sometimes we can’t. Even when the frame is empty, maybe we can create something from nothing. Learn something by doing it. Know something by knowing it. Learn to grieve by grieving.

Snowshoeing in Kingston, Nova Scotia (sent by my friend Sandra, and taken by her sister Brenda)

Photos from Banff, Alberta, sent by my brother, Tom

Photos from Hawaii, sent by my sister Edie

My mother’s orchids

Photos from my recent walk with friends, and our dogs, at Fort Needham, in Halifax

March 10, 2023

The Last Phone Booth

When I read about the “world’s smallest Austen museum” in a red telephone box in Steventon, Hampshire, in a recent Atlas Obscura piece, I could almost hear Joel Plaskett singing “I am standing in The Last Phone Booth on The Planet Earth / Just trying to get an operator / Please connect me now to anyone.”

This red telephone box is obviously not the one in Hampshire. It’s in Nova Scotia’s Gaspereau Valley, at Luckett Vineyards. I added a digital frame as part of an assignment for an online photography class I took several years ago (taught by the always-inspiring Joy Sussman of Joyfully Green).

I took another photo from the same spot during the Jane Austen Society (UK) conference that was held in Halifax in June of 2017. Following lunch at the vineyard, our group visited the memorial church and the statue of Evangeline at Grand Pré National Historic Site.

The telephone box Jane Austen museum also functions as a book exchange, like a Little Free Library, or the book stalls in Bonn that my sister Bethie checks regularly to look for English books.

She recently found two different editions of Tom Jones, which she took as a sign that she should read it right away, and she loved it. She sent me a photo of a few of her treasures. The most unusual book she’s discovered there is a German cookbook featuring recipes from ancient Rome, which appealed to her because she’s a Classics scholar.

A few more things for this week’s “scrapbook”:

First, a blog post by Donna M. Campbell: “First Edition of The House of Mirth: A Literary/Bibliographical Mystery.”

Did you know that Edith Wharton hated the illustrations for this novel so much that she tore them out and crossed out the illustrator’s name?? I didn’t (or if I did, I had forgotten).

The mystery has to do with whether the first edition, first printing of The House of Mirth is the one without ads or the one with ads included on pages 535-38.

I own two early editions of the novel, both published by Scribner’s, one in 1905 and the other in 1931. The 1905 edition includes the ads, which—I think, based on what Donna says in her blog post—means it may be the first edition, first printing. The 1931 edition used to belong to the library of Leverett House, Harvard University. The cloth on the spine is torn and the book has been mended in a few places. Fortunately, the 1905 edition is much better condition.

If this were a real scrapbook, I might be tempted to affix this adorable origami frog—made by the sister of one of my friends, who enclosed it with a card she sent me a few days ago (hello and thank you, Sandra and Brenda!)—to one of the pages. But then my family and I wouldn’t be able to press on its back to make it leap across our dining room table. So I’ll just include a photo here, and leave it free to keep moving.

Here are some photos from a hike with friends last Sunday, on the snowy trails at Long Lake. Whenever I see that bright blue sky, I’m tempted to take lots of pictures. On this occasion I managed to snap only a few, however, because I spent much of the time trying to prevent our dog from running out onto the ice, just in case it isn’t frozen solid anymore.

Halifax, as seen from the Dartmouth waterfront on Sunday evening:

On Monday, the clouds had returned. When I went downtown for an appointment that afternoon, I took a couple of pictures of the Old Burying Ground, which served as the inspiration for “Old St. John’s Graveyard” in L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of the Island.

“I don’t know that a graveyard is a very good place to go to get cheered up, but it seems the only get-at-able place where there are trees, and trees I must have. I’ll sit on one of those old slabs and shut my eyes and imagine I’m in the Avonlea woods.”

– Anne Shirley

On Tuesday evening, I visited the Truro Library, to hear Alexander MacLeod read from his brilliant short story collection Animal Person. If you’re interested, you can listen to him read his story “Once Removed,” which was published in the New Yorker last year.

I tried to capture the lights on the trees next to the library, and this is what I ended up with:

It isn’t what I expected, but I like it even more this way, so I’ll keep it.

Here are a couple of things linked to last week’s post, “Oh, novels! What would I do without you?”

I found photos of the second Regency gown I made for my daughter. Here she is at age nine, when we attended the JASNA AGM in Washington, DC:

And here’s a link to The Next Chapter on CBC Radio, where you can listen to Heidi L.M. Jacobs talking about her novel Molly of the Mall: “Heidi L.M. Jacobs’s novel Molly of the Mall is a charming look at life in Edmonton.”

“It’s a book about finding out who you are by navigating where you’re from and also about finding the beautiful and the poetic in wherever you live. But I think at its core it’s really about how books help us learn who we are and about how books help us find a space and a place and a voice in the world.”

I’ll say goodbye for now and leave you with this photo of two parrots, a fox, and a dragon, created and photographed by Brenda Barry of Triad Photography. Thanks for reading, and I hope you have a pleasant weekend.

March 3, 2023

“Oh, novels! What would I do without you?”

Let’s read Jane of Lantern Hill! Thanks to everyone who commented—here, on social media, in letters and emails, and in person—in response to last week’s post about Reading L.M. Montgomery Together. Based on the responses we received, Naomi and I have decided to read Jane of Lantern Hill this spring, and we hope you’ll join the conversation. We’re planning to write about the novel in May. (And maybe we’ll turn to Kilmeny and/or Pat later on. We also took note of the votes for Rilla and Emily. Thank you for your enthusiastic response to all these books!)

If you’re interested, you might like to subscribe to Naomi’s blog, Consumed By Ink, as well as mine. We’ll link to each other’s posts about the novel, and to posts by others, too, so please do send us details and links if you decide to write about your experience of reading/rereading the novel. Let’s use #ReadingLanternHill as our hashtag.

My title for today’s post comes from Molly of the Mall, by Heidi L.M. Jacobs, rather than from Jane of Lantern Hill. More on Molly below—for now I’ll just say that I think she and L.M. Montgomery’s heroines would be kindred spirits.

So far, I’ve read the first chapter of Jane of Lantern Hill, and I’m keen to read more, about the huge brick house on Gay Street with its “towers and turrets wherever a tower or turret could be wedged in,” and gates “that were always closed and locked” at night, “giving Jane a very nasty feeling that she was a prisoner being locked in.” I want to learn more about Jane, who knows very clearly that her name is Jane even though everybody calls her Victoria. Even her mother calls her Jane Victoria. I know I read the novel when I was ten or eleven, but I don’t think I’ve read it since then, and I’ve forgotten almost everything, aside from a vague sense of having loved it a great deal, in the same way that I loved nearly all of Montgomery’s books (aside from Anne of Windy Poplars, which I didn’t like back then, and didn’t like when I reread it a few years ago).

Have any of you seen the 1990 film adaptation of Jane of Lantern Hill, starring Mairon Bennett, Sam Waterston, and Sarah Polley? I haven’t (yet). Maybe we could discuss it as well, in May.

Inspired by L.M. Montgomery, I’m still working (as I mentioned last week) with the idea that my blog is a kind of scrapbook. Here are a few things I’d like to “paste” in to share with you.

First, a blog post by Shawna Lemay on how to “re-frame, retrain our brains, how to shift or jostle or shine up our thinking.” Her blog, “Transactions with Beauty,” is always inspiring, and I’ve long admired her work as a photographer, poet, and novelist. We knew each other many years ago when we were both undergraduates in the Honors English program at the University of Alberta, and it’s been wonderful to reconnect with her online over the past several years. I’m reading her novel Everything Affects Everyone right now and I love it. I’ll probably write about it in more detail here once I’ve finished it. I agree whole-heartedly with what Shawna says in this post from last week about a key source of creative inspiration:

“I myself think a relatively easy shortcut to changing or enlivening our thinking is pretty much always going to be: read more poetry.”

I chose this scarf for the background because it was a gift from a friend who lives in Edmonton, and because in the opening paragraph of the novel, the narrator, Xaviere, speaks of choosing to wear a scarf she could imagine her friend Daphne “reaching over and touching—she’d have admired the texture and colours and would have leaned over and delicately fingered the knotted fringe.”

Sticking with an Alberta theme, and the topic of handmade scarves, I want to share this lovely piece by Angela of Neatnik Yarns, in Edmonton, Alberta, called “Making Things to Feel Better.” It’s from the winter of 2021, written in an earlier stage of the pandemic, but I discovered her website only a few days ago, and I think what she says about the healing power of making things with our hands is just as true now as it was then. She writes that for many, “the attention required while we make these things results in a sort of meditative state,” and that “the fibre arts provide both tactile and mental comfort.”

One of my accomplishments over the first couple of years of the pandemic was that I finally completed a cross-stitch kit I had purchased in the gift shop of the Bodleian Library in 2002, with the goal of giving the finished product to my mother for Mother’s Day that year. It was a glasses case, with a pattern based on a design of strawberries and flowers embroidered for Queen Victoria by her mother. This was only the second cross-stitch project I had ever attempted in my life, and I worked on it a little at a time year after year. Last winter, I finally finished it, and I presented it to my mother as a very belated Mother’s Day 2002 present. I guess I could have said it was a few months early for Mother’s Day 2022, but I stuck to the truth.

After I had completed that project, my daughter and I spent several pleasant hours last winter working on rug hooking kits we had purchased in the summer of 2021 from Deanne Fitzpatrick’s studio in Amherst, Nova Scotia. My daughter worked quickly, and completed her Wild Rose Field within a couple of days. It took me longer to complete my Lost Sheep kit—about a week—but I must say, it was tremendously satisfying to complete a kit in under twenty years. My daughter gave the wild roses to me, and I gave the sheep to her. We haven’t framed them yet, and for now, they’re on display in our kitchen, hanging from a curtain rod we’ve used for years as a place to display drawings and paintings, or Christmas ornaments. I like them this way, with the titles visible.

It was fun to try something new. I’ve worked on many sewing projects over the years, including two Regency gowns for my daughter, who wore them at JASNA (Jane Austen Society of North America) conferences we attended together. I enjoyed my experiments with both cross-stitch and rug hooking, and I agree with what Angela says about how the act of working with our hands on projects like these can provide comfort during challenging times. Deanne Fitzpatrick says something similar about rug hooking, which can be “joyful, powerful and transformative.” I felt grateful to be able to create something small, something beautiful, to give as a gift to someone I love, regardless of how long it took to make it.

Here’s a photo of my daughter in the gown she wore for the Regency Ball at the JASNA AGM in Montreal, in 2014 (shared here with her permission):

Another addition to my scrapbook, again with a connection to my Alberta theme: I want to recommend Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass and Purveyor of Fine Footwear, by Heidi L.M. Jacobs, which I finished reading yesterday. I’m not sure how I missed this book when it came out in 2019, but I’m delighted to have found it at last, thanks to Naomi. (If you’ve read the last few posts on my blog, you’ll know already that Naomi is an excellent source for book recommendations.) I’m rarely up to the minute on book news—usually I’m somewhere in the 19th Century, instead of the 21st—and I like tracing the often-circuitous routes through which I make new discoveries.

I absolutely loved Molly of the Mall, and not just because it took me right back to the early nineties, when I, like the fictional Molly (and my friend Shawna, as mentioned above), was an English major at the University of Alberta. I also, again like Molly, worked in a mall in Edmonton, although in my case it was a fabric store in Kingsway Mall, rather than a shoe store in West Edmonton Mall. And I visited the same cafés and bars on Whyte Avenue and the U of A campus, including Java Jive and Dewey’s.

The silk scarf in the background was a gift from our family’s dear friend Janet. My parents met her in Edmonton when they were graduate students.

The view from my dorm room in my first year at the U of A:

Kerry Clare says in her review that she is “besotted” by Molly of the Mall, and while she acknowledges that it might not be for everyone, “if you came of age in the 1990s, worked in a shopping mall, longed for a literary life, ever felt a bit weird about your dad’s devotion to Robbie Burns, dreamed of a romance that was swoon-worthy, felt confused in university English classes, and let 19th century novels play perhaps too great a role in informing your perspective on … everything—then you will not be sorry.”

Edmonton in the summer of 1991:

Sometimes I actually felt as if I were reading about my own life as the child of graduate students in the English Department at the University of Alberta. I thought of my own first name when Molly, who is named for Moll Flanders (and whose siblings are named Tess and Heathcliff), says that “The next generation of departmental children had solid Old Testament names.” When I read about Molly’s mother defending her master’s thesis on Botticelli just two days before Molly was born, I thought of my mother defending her master’s thesis on Malcolm Lowry’s novel Under the Volcano less than a month before I was born.