Secrets and Silence in Sense and Sensibility, by Deb Barnum

“Come, come, let’s have no secrets among friends.”

(Volume 2, Chapter 4)

Mrs. Jennings may request “no secrets among friends,” and Marianne may “abhor all concealment” (Volume 1, Chapter 11), but Sense and Sensibility is chock full of both—many secrets, much concealed—within each character, between characters, and between the author and the reader.

(From Sarah: This is the sixth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

P.D. James, in her essay “Emma Considered as a Detective Story,” defines the detective story as one “requiring a mystery, facts which are hidden from the reader but which he or she should be able to discover by logical deduction from clues inserted in the novel with deceptive cunning but essential fairness. It is about evaluating evidence . . . it is concerned with bringing order out of disorder and restoring peace and tranquility to a world temporarily disrupted by the intrusions of alien influences.”

Such is Emma, truly a mystery, where Jane Austen gives us clues and puzzles and hints along the way, whereby we the reader can solve the underlying mystery right along with Mr. Knightley, who gets awfully close, but not quite close enough, to the solution.

But Sense and Sensibility offers no such clues to assist either the novel’s characters or the reader to any understanding of what is happening. Patricia Meyer Spacks writes: “Gradually the novel reveals that almost everyone has a secret, everyone—even characters dedicated to morality—conceals something” (“Afterword,” Sense and Sensibility [1982]). Thorell Tsomondo says: “. . . these secrets contribute to the query and puzzlement that characterizes the work” (“Imperfect Articulation: A Saving Instability in Sense and Sensibility” [Persuasions 12 (1990)]). Emma may be a mystery, but in S&S, it is all confusion, the reader not in on it. We are led to believe that Elinor is all-seeing, but indeed she often misunderstands, is wrong in her assumptions. We are presented with a Willoughby described, his true self a secret to all, as a good person, the perfect Romantic Hero (though we should have heeded the warning: “his person and air were equal to what her fancy had ever drawn for the hero of a favourite story” [Volume 1, Chapter 9])—and here Austen conceals perhaps the biggest secret of all, that it is her Colonel Brandon who is the true Romantic Hero of S&S, flannel waistcoat and all.

“Carried her down the hill,” C. E. Brock, S&S (courtesy of Molland’s)

Tuning into the myriad of secrets in S&S is certainly not new ground: a number of scholars have written about the issue of pervading secrecy in this novel (see references below). So these thoughts are nothing new, but I found it helpful to look at the extent of the secrecy. Indeed, the words “secret,” “secrecy,” “conceal,” “deceive,” “betray,” all appear numerous times in S&S. And more telling perhaps is the occurrence of “silent” or “silence,” certainly another aspect of secrecy—the decision not to tell, not to speak, to remain silent rather than reveal. Another word count to note is “eyes”—Austen often referring to what the eyes see when words are deceptive or untruthful, or when silence is chosen and characters rely on “the eyes” to perceive the truth: recall Elinor’s frequent reference to Lucy’s “little sharp eyes,” and Mrs. Dashwood, upon learning that her favorite Willoughby is really such a cad, remarks that “there was always a something in [his] eyes at times, which I did not like” (Volume 3, Chapter 9).

There is in S&S also an element of surprise—surprise being a secret of sorts—in the unexpected arrivals of the various heroes: Marianne declares almost verbatim on two occasions “It is he . . . I know it is!” expecting Willoughby and facing the disappointing “surprise” of Colonel Brandon and later Edward. Elinor is awaiting her mother and the Colonel and is surprised (as we all are—this feels like a Brontë novel!) when “she rushed forwards and . . . saw only Willoughby” (Volume 3, Chapter 7). (This gives short shift to a topic that needs an essay all its own!)

Secrets, of course, are a form of manipulation—and there is much of this going on as well. The story begins with a secret—on his deathbed, Henry Dashwood requests his son to help his second wife and three daughters. (Indeed the whole change in the inheritance from his Uncle to the young Dashwood boy was a secret revealed at the will-reading.) Mr. John Dashwood thought to offer a present of £1000 a-piece to each of his sisters and Mrs. Dashwood is led to believe he will take care of them in some way, “[relying] on the liberality of his intentions” (Volume 1, Chapter 3)—alas! to no avail, as Fanny Dashwood assiduously talks him out of doing anything in one of the most cringe-inducing chapters in all of literature. So the novel begins—with concealment and deception.

All three of the male characters in S&S harbor the secret of a previous romantic entanglement, what Paula Byrne calls “a parody of secret engagements” (Jane Austen and the Theatre [2002]). Edward’s secret engagement to Lucy; and Willoughby’s seduction and abandonment of Colonel Brandon’s ward Eliza. The reader is misled about these characters—we believe as Mrs. Dashwood and Elinor and Marianne do, that the unexpected departures (that element of surprise again) of both Edward and Willoughby are due to the expressed displeasure of their respective parent-figure, Mrs. Ferrars for Edward, Mrs. Smith for Willoughby.

“Col. Brandon was invited to visit her” – C. E. Brock, S&S, Dent, 1898 (my collection)

Colonel Brandon is, of course, a walking secret—with his past of “injuries and disappointments” (Volume 1, Chapter 10), the story of his first love hinted at throughout—“I once knew a lady” (Volume 1, Chapter 11) is only (and secretly) revealed to Elinor and the reader in Chapter 9 of Volume 2 as he explains his secret past, his secret-laden departure to London, his secretive dual with Willoughby, “the meeting never [getting] abroad.”

Even the ridiculous Robert Ferrars has a secret—his deceptive growing relationship with Lucy, his remaining hidden in the rear of the carriage when he and Lucy meet up with Thomas. Why, Robert Ferrars’ entire character IS a secret—we are introduced to him as the fop in the jewelry store long before we find out who he is. What a surprise Austen has in store for us when she makes him the plot-solver! And dare we forget Mr. Palmer?, a Scrooge-like character, who surprises us all when his secret is revealed that he is actually not such a bad fellow after all.

“Introduced him to her as Mr Robert Ferrars” – C. E. Brock, S&S, Dent, 1908 (courtesy of GoogleBooks)

But it is not just the men who have secrets, the women do as well—all of them. Lucy’s engagement, her “great secret” and her use of this to manipulate Elinor is what drives the plot. But Elinor is the keeper of secrets—she tells no one about Lucy’s engagement, keeping to her promise; she keeps Brandon’s secrets; but she also conceals her own feelings about Edward, she “mourns in secret” when she believes she has lost him forever, and she keeps secrets from herself—she remains “assured within herself of being really beloved by Edward” (Volume 2, Chapter 1), when we from the text have no such certainty. And for two sisters so close, she and Marianne keep their most important thoughts and feelings from each other. Elinor speaks of “this strange kind of secrecy maintained by them relative to their engagement” (Volume 1, Chapter 14); she cannot, nor will Mrs. Dashwood, break into their “extraordinary silence” (Volume 1, Chapter 14) to discover the truth. Months go by in this state of non-communication. Marianne’s oft-quoted “we have neither of us any thing to tell; you, because you communicate, and I, because I conceal nothing” (Volume 2, Chapter 5) is sure proof that nothing is as it seems inside the strange world of Sense and Sensibility. Marianne’s claim is the ultimate irony, when, indeed, Elinor has been completely silent on her own inner turmoil, and Marianne, though unable to control her emotions, has been concealing everything. “Ask nothing,” she says to Elinor, “you shall soon know all” (Volume 2, Chapter 7).

La Belle Assemblee, 1807

Society at the time required circumspect behaviors, especially of its female members—one acted demurely, maintained secrets, told polite lies. As Tony Tanner says, “. . . it was a society that forced people to be at once very sociable and very private” (Jane Austen [1986]). Byrne talks of the “the level of deceit in the marriage market” (Jane Austen and the Theatre [2002]), and Spacks goes so far as to say that the entire “plot of S&S suggests that women must and men should conceal their feelings” (“Afterword,” Sense and Sensibility [1982]). When Elinor admonishes Marianne “Pray, pray be composed and do not betray what you feel to every body present” (Volume 2, Chapter 6) as Marianne screams for Willoughby to attend her, we are seeing this conflict of honest expression versus proper behavior. In the beginning of the novel, there are several references to Elinor needing to tell little lies, “the whole task of telling lies when politeness requires it” (Volume 1, Chapter 21), unlike Marianne, who wears everything on her sleeve. Elinor later in the novel becomes less able to perform these social niceties—she more and more responds with silence, this repeated numerous times, with the final wordless bolting from the room upon hearing that Edward is free of Lucy.

“His errand . . . was a simple one. It was only to ask Elinor to marry him” C.E. Brock, S&S (my collection)

One forgets in tearing S&S down to its bare bones, what with all these secrets; all the duplicitous characters lurking about; the lies (can we ever really forgive Edward for his secrecy and the outright lie about the ring?); all the behind the scenes seriousness of Colonel Brandon’s history of lost love, his secret duel (we must add here Brandon’s very quick reference to his ward Eliza’s friend, “who with a most obstinate and ill-judged secrecy [my italics] would tell nothing, would give no clue, though she certainly knew it all” [Volume 2, Chapter 9] regarding Eliza’s whereabouts); and Willoughby’s betrayal of both Eliza and Marianne—with all this, how easy it is to forget that S&S is a comedy after all! Is there anything more laugh-inducing that the scene when Edward arrives to find both his Lucy and his Elinor together?—I know that you know but pretending I don’t know, etc.—a perfectly drawn piece of theater (for an insightful look at Austen’s love of and use of such dramatic elements, see Byrne).

And who better to return us to good humor that Mrs. Jennings, certainly the most loveable and endearing of Austen’s cast of annoying characters. If in Elinor we have the keeper of secrets, in Mrs. Jennings we have the lover and teller of secrets, the good-natured gossip, though she most often gets it all wrong. She (along with Sir John Middleton) makes much of the secret letter “F”; she is sure that Colonel Brandon has a “natural daughter”; tells all that Marianne and Willoughby are secretly engaged; gossips that Willoughby and Miss Gray are to be married; and ends with “the important secret in her possession” (Volume 3, Chapter 4) that Elinor and the Colonel are to be engaged! Mrs. Jennings certainly personifies Austen’s belief in gossip as a living social entity that undermines the keeping of secrets: in her letter to Cassandra of 5 September 1796:

Mr. Richard Harvey is going to be married; but as it is a great secret, & only known to half the Neighborhood, you must not mention it. The Lady’s name is Musgrove.

‘With a letter in her outstretched hand” – C. E. Brock, S&S, Dent, 1898 (Internet Archive)

But let’s return to the concept of Jane Austen as the writer of detective stories. Margaret Ann Doody in her introduction to the Oxford edition of S&S quotes Joseph Wiesenfarth: “the very structure of the novel attempts to engage and develop the total personalities of Elinor and Marianne by presenting them with a series of mysteries that must be solved.” Doody says that “the characters are all detectives trying to put together this piece and that piece of information.” She cites Mrs. Jennings’ declaration to Marianne: “I have found you out in spite of all your tricks” about the latter’s secret visit to Allenham with Willoughby, showing that all the characters are in a sense spying on each other to get at the truth (“Introduction,” Sense and Sensibility [2008]).

An abundance of secrets will certainly set any detective worth her/his salt to action—and Sense and Sensibility does not disappoint, despite an inherent sense of confusion. And so all ends as all good English novels do—with the requisite comedic ending, where the truth will out, all is revealed, each character is given their just due, and whether you like that Marianne ends up with Colonel Brandon or not (another essay!), and we are told that Willoughby will forever regard Marianne as “his secret standard of perfection in woman” (Volume 3, Chapter 14), order is restored, and all is quite right with the world.

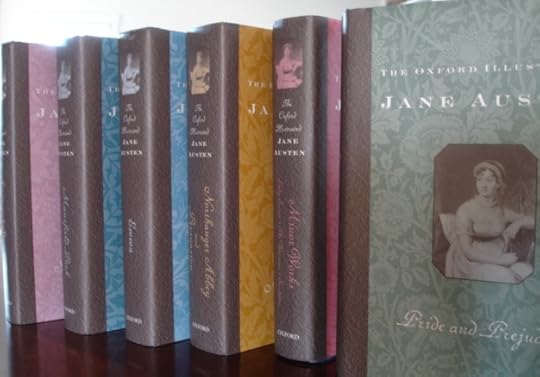

The Novels of Jane Austen. Ed. by R. W. Chapman. 3rd. ed. Oxford, 1933, 1988 printing (my collection)

Quotations are from the 3rd Oxford edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited by R. W. Chapman, 1988 printing; and the 4th Oxford edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (2011, 2014 pb ed.). This essay is a slightly edited version of a post for Maria Grazia’s blog tour of Sense and Sensibility on June 19, 2011 at “My Jane Austen Book Club,” and reposted with her permission.

I welcome your comments! Can you remember the first time you read Sense and Sensibility? What secret in the novel most surprised you?

“Elinor agreed to it all, for she did not think he deserved the compliment of rational opposition.”

Further Reading:

Byrne, Paula. Jane Austen and the Theatre. London: Hambledon, 2002.

Doody, Margaret Ann. “Introduction.” Sense and Sensibility. By Jane Austen. New ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2008.

Drabble, Margaret, “Introduction.” 1989. Sense and Sensibility. By Jane Austen. New York: Signet, 1997.

James, P. D. “Emma Considered as a Detective Story.” Time to Be in Earnest: A Fragment of Autobiography. New York: Knopf, 2000.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer. “Afterword.” Sense and Sensibility. By Jane Austen. New York: Bantam, 1982.

Tanner, Tony. Jane Austen. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1986.

Tsomondo, Thorell. “Imperfect Articulation: A Saving Instability in Sense and Sensibility.” Persuasions 12 (1990): 90-110.

Wiesenfarth, Joseph. “The Mysteries of Sense and Sensibility.” The Errand of Form: An Assay of Jane Austen’s Art. New York: Fordham UP, 1967.

Deb Barnum, author of the Jane Austen in Vermont website, had a former career as a law librarian and later owner of a used bookshop. She is a lifetime member of JASNA, co-founded the JASNA-Vermont Region, now helps the JASNA-South Carolina Region; gives various talks on Jane Austen and other writers at the OLLI program at USCB; is a board member of the North American Friends of Chawton House; and assists with locating the Lost Sheep of Godmersham Park for Peter Sabor’s “Reading with Austen” project and writes its corresponding blog at https://readingwithaustenblog.com/ . She took the photo of irises in Spain at the Alhambra.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “At Home with Sense and Sensibility,” is by Lizzie Dunford, and I’ve scheduled it for Sunday, July 7th, because that’s the anniversary of the date Jane moved to Chawton Cottage in 1809, along with her sister Cassandra, their mother, and their friend Martha Lloyd.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Mysteries of the Human Heart in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, by S.K. Rizzolo

The Darkness of Sense and Sensibility, by Deborah Yaffe

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.