The Darkness of Sense and Sensibility, by Deborah Yaffe

For a romantic comedy, Sense and Sensibility is a startlingly dark book. And that darkness inheres not solely in the novel’s disturbing plot elements—economic dispossession, familial cruelty, romantic betrayal—but perhaps especially in its brutally negative portrayal of social life: the social life available to its heroines and, by extension, to all of us.

Park Güell in Barcelona

(From Sarah: This is the fourth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Outside their family circle, and sometimes even within it, the Dashwood sisters’ social world is a place of disconnection and dissimulation. It’s a place where bonds are frequently superficial: The novel’s most compulsively sociable character, Sir John Middleton, can’t even tell the difference between physical proximity and emotional closeness—“to be together was, in his opinion, to be intimate” (Volume 1, Chapter 21). It’s a place where etiquette requires spending time with people you don’t like, and who don’t like you: In London, Elinor and Marianne reluctantly pass their days with Lady Middleton and the Steele sisters, “by whom their company, in fact was as little valued, as it was professedly sought” (Volume 2, Chapter 14). It’s a place where pain is inflicted routinely—either inadvertently, as with the relentless “letter F” (Volume 1, Chapter 21) jokes that torture Elinor; or deliberately, as with Lucy Steele’s passive-aggressive jabs. Above all, the social world of Sense and Sensibility is a place where concealment and artifice are mandatory, where participation requires that you master the “task of telling lies when politeness required it” (Volume 1, Chapter 21)—of thinking things you can’t say, and saying things you don’t believe.

All these characteristics of social life are on vivid display during John and Fanny Dashwood’s dinner party (Volume 2, Chapter 12), the most excruciating of the book’s long procession of dull, awkward, or hurtful social occasions.

The gathering is a study in disconnection: Almost no one fully understands the agendas and motivations of their fellow guests. Ignorant of the secret engagement, Mrs. Ferrars and Fanny patronize Lucy and slight Elinor; talking to Colonel Brandon, John Dashwood disparages the beauty of the sister Brandon loves while praising the artistry of the one he doesn’t. No one has anything substantive to say (“no poverty of any kind, except of conversation, appeared—but there, the deficiency was considerable”), and the verbal interactions pulse with a symbolic competitiveness. When the men are present, the topics of discussion are “politics, inclosing land, and breaking horses”—a nutshell summation of the ways in which Regency men exercise power (social, economic, physical) over others. When the women are alone, this male struggle for primacy in the public world is transmuted into a proxy war waged in the domestic sphere, as the mothers and grandmothers debate the relative height—literally, the status—of their male offspring. Sometimes, words are used with an intent to wound, as when Fanny Dashwood and her mother flatter the absent Miss Morton in order to disparage Elinor. But just as often, pain is inflicted involuntarily: Although meant to console her sister, Marianne’s conspicuously emotive response hurts more than the insults that provoked it.

Throughout the dinner party sequence, Austen deploys her characteristic free indirect discourse to heighten the atmosphere of emptiness and alienation. First, acerbic reflections in Austen’s narratorial voice—Mrs. Ferrars “was not a woman of many words; for, unlike people in general, she proportioned them to the number of her ideas”—turn her critique of particular characters into a broader indictment of “people in general.” And then Austen seamlessly slides into Elinor’s mind, allowing us to eavesdrop on the internal monologue that this expert painter of pretty screens is screening from public view. We listen in as Elinor considers, and then rejects, the temptation to meet Lucy’s baiting with a cutting reference to her romantic rival Miss Morton, instead assuring Lucy “with great sincerity, that she did pity her.” We hear Elinor register Mrs. Ferrars’ rudeness and then tell herself, perhaps self-deceivingly, that she is impervious to it (“a few months ago it would have hurt her exceedingly; but it was not in Mrs. Ferrars’ power to distress her by it now”). And we share in Elinor’s bitter amusement at the spectacle of Fanny and her mother patronizing the Steeles (“while she smiled at a graciousness so misapplied, she could not reflect on the mean-spirited folly from which it sprung, nor observe the studied attentions with which the Miss Steeles courted its continuance, without thoroughly despising them all four”). Outwardly, Elinor is calm, polite—even, apparently, sincere—as she enacts necessary social lies. Inwardly, she observes, and despises.

El Retiro Park in Madrid

What makes the dinner party sequence hilarious is the dual consciousness that Austen’s free indirect discourse grants us. Whether rendered as omniscient narrative or as internal monologue, this voice tells the truth about the shallowness, artificiality, and unkindness of the dinner guests, freeing us from the socially mandated lying that burdens the Dashwood sisters. We are granted a privilege that the characters don’t have—the license to laugh at this world without being trapped inside it. But precisely because this episode is so funny, it’s easy to overlook its brutality, and what that brutality implies about the stifling nature of the demands social life makes on the Dashwood sisters. Austen hints at that brutality when she characterizes Elinor’s response with a startlingly bleak word: “despising.” Elizabeth Bennet is amused by her social world, but Elinor Dashwood hates hers. What, we may wonder, is the cost of the concealment that social life requires of Elinor and Marianne—and perhaps of the rest of us, as well?

Austen grants us a brief, oblique insight into that cost a few chapters later, after the secret engagement has come to light. For once, Elinor has succeeded in forcing Marianne to adopt the socially mandated repression that she herself has practiced throughout the novel: Marianne has promised to speak politely of the Edward-Lucy match. Marianne “performed her promise of being discreet, to admiration,” we learn. “She listened to [Mrs. Jennings’] praise of Lucy with only moving from one chair to another, and when Mrs. Jennings talked of Edward’s affection, it cost her only a spasm in her throat” (Volume 3, Chapter 1).

“Only a spasm in her throat”: It’s hard to imagine a more viscerally powerful evocation of the painful—almost physically painful—price of keeping silent, of literally swallowing an authentic response. It’s a tiny moment that, by illuminating everything that’s come before it, brings the darkness of Sense and Sensibility into the light.

Quotations are from the e-text of Sense and Sensibility at Mollands.net, retrieved on 3 May 2024. Photos contributed by Deborah.

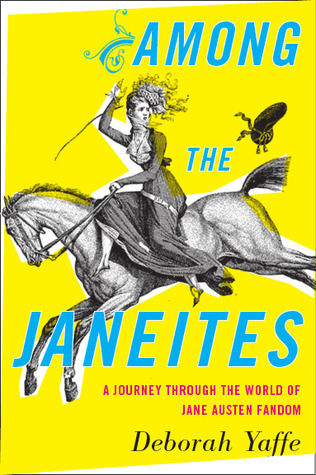

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance journalist and the author of Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom (Mariner Books, 2013). She blogs about Austen-related matters at https://www.deborahyaffe.com/.

Part of Deborah’s collection of Austen-related souvenirs

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Mysteries of the Human Heart in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility,” is by S.K. Rizzolo.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Sense and Sensibility in my most need, by Heidi LM Jacobs

What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes, by Finola Austin

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.