Tim Patrick's Blog, page 32

July 27, 2011

Review #5: Meditations on First Philosophy

The seventeenth century was a difficult time, what with the Enlightenment and all. People were looking for new solutions to age-old problems, and they had no qualms about throwing old beliefs into doubt. René Descartes thought that if you are going to start doubting, you might as well do something useful with it.

Warning

This review contains spoilers. But if nothing that is real exists, do these spoilers exist?

In Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes discards all of his preconceived beliefs, and starts to build a new foundation of only those truths he can discern through pure reason. It's a big job, and Descartes does it with the gentle manner of a aged, retired philosopher. The book is divided into six separate "meditations," each building upon the previous entry.

I start with the notion that nothing I perceive with my senses, or believe with my mind, is real.

I think, therefore, I am. I wouldn't be thinking these thoughts if I didn't exist. Even if a malevolent being is deceiving me by creating an artificial reality for me, I still exist as one who can be deceived.

Every effect must have a cause that is at least as real as the effect. Because I exist, something at least as real as me must have brought me about. Also, I can imagine things that are beyond what I am capable of producing on my own, things that would be considered "perfection." These must also have a real, perfect cause. For these reasons, a perfect being beyond me—God—must exist. Also, I am not God, since I would not have these doubts or limits if I were God. This God is, by nature, not a deceiver, since perfection does not deceive.

Perfection excludes errors. Therefore, any errors I experience must be due to a lack of judgment on my part, where the limits of my will exceed the limits of my understanding.

Because I cannot, by reason, conceive of a reality without God, God must therefore exist. As an extension, reality must also exist.

Mathematical truths, such as quantities or the idea of a triangle, exist apart from my ability to imagine them. I cannot picture a 1,000-sided object in my mind alone, but the idea of it exists despite my limitations. Physical objects may or may not exist, but because God is not a deceiver, and because he created my senses to give the experience of position and motion in myself and in objects, such things must exist.

That's as real as it gets for Descartes. Even as a Christian, I struggled with his second meditation, the one that says God must exist because our ideas about perfection demand it. His explanation, however, is more rigorous and detailed than my summary, proof that the cause is at least as great as the effect.

If you find yourself in a moment of existential angst, I highly recommend a read through Meditations on First Philosophy. Read, and exist!

July 25, 2011

The Founding Tweeters

I received an email from Microsoft this weekend with links to its "History Reimagined" video series that promotes the Office 2010 product line. In each video, one Office product plays a pivotal role in some famous event from American history. The entry for Microsoft Word shows the Founding Fathers crafting the Declaration of Independence using Word's document development features.

It's a cute video, but it begs the question: Could the founders really have written the same document using modern technology? I'm not asking if it could be done physically. Of course you can replicate the look and feel of the original document through a modern word processor. But in our 140-character headline-only society, and in an age when political leaders can't even agree on how to balance a checkbook, could you gather enough well-read representatives together long enough to craft a document as weighty as the Declaration?

The leaders of the American revolution were steeped in the classics. They regularly read Cicero, Locke, Plutarch, Voltaire, Homer, and scores more noteworthy authors. And they didn't just read; they re-read. Books were produced in limited runs, and were expensive by today's standards. Second readings were always free. Readers of that era also committed the core ideas and quotations of each book to memory. And it shows in the writings that they themselves produced. While we have more access to such content today, I bet you could count on two hands the number of congresspersons who have read even ten percent of the classic works that John Adams consumed.

Education in the eighteenth century wasn't perfect, and many average citizens didn't have the same access to content that these colonial aristocrats did. Today we have no such excuses. And while I could lay a guilt trip on the general public, instead I'll direct you to these other Microsoft-produced videos from great events in history.

Apollo 11 moon landing using Microsoft Excel

The Wright Brothers using Microsoft PowerPoint

Thomas Edison's electric lamp using Microsoft OneNote

July 21, 2011

Reading on the Go

A lot of states have enacted laws that prevent you from making calls on your cell phone while driving, or from texting your friends from behind the wheel. But lawmakers have overlooked the reading of electronic books while operating heavy machinery. At least, that seems to be a big selling point behind MegaReader, an eBook app for iOS devices. Here's the promotional video / user's guide.

Remember kids, reading is dangerous.

July 20, 2011

How to Toss a Book

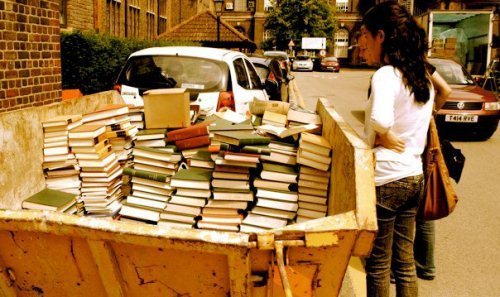

A friend of mine is touring England this summer, and posted the following picture on her Facebook account.

It's a quick peek at how books are treated in Cambridge. That's right, nicely bound classic books tossed willy-nilly in the garbage. It's a sad sight, but one that may be more common in the years ahead. Two recent trends are driving this transformation. The first is, naturally, the rise of eBooks. Who needs paper when you can make the same content available in a variety of electronic formats? It's cheaper to store and inventory, it's quicker to get the books out to more people, and you don't need those pesky library volunteers dusting shelves.

The second trend is in how libraries are transforming themselves in the twenty-first century. Libraries have always been more than just repositories for books. They store all types of content for patrons: newspapers and periodicals, audio and video recordings, and government publications, just to name a few. They have also act as research centers for the serious student, and a brick-and-mortar New York Times Bestseller lists for those looking for a great read.

But this traditional view of libraries is changing. Instead of focusing on making content available to the public, modern libraries are becoming places where the public is made available to the content. It's now all about the patron, not the books. The The Case for Books, laments the replacement of physical newspaper archives in libraries with microfilm images of those same publications, a practice that began decades ago. In Chapter 8 of the book, he quotes another expert who "rightly warns that the enthusiasm for digitizing could produce another purge of papers [from libraries]." Sounds like a prophecy to me.

So if you are looking for some books to read, to even up your kitchen table legs, or as decor for your walls, stop by the back door of your local library. Just be sure to bring a really big box.

July 19, 2011

So Long Borders!

This week, the Borders chain of bookshops announced they would close their existing 399 locations. The liquidation will run through September. The Borders stores I visited over the years always felt like the hip, younger brother to the more staid and button-down Barnes and Noble locations. And by "hip" I mean the type of person your parents told you not to associate with, and hence the closure.

The standard line is that, although traditional bookstores are failing left and right, book sales are just fine. Customers are simply choosing to purchase their reading choices from places that offer better pricing (Amazon.com), more convenience (Amazon.com), or content in electronic formats (Amazon.com). Those are all valid points, but it isn't the only reason that stores like Borders go under.

Decades ago, bookstores used to be a place where you bought books. It wasn't that different from the clothing shop, the fishmonger, or the Rolex truck; when you needed a book, you went to the bookstore. When mega-bookstores came on the scene, book buying became more than just an item on a shopping list; it became a lifestyle choice. Instead of going to the movies, your family could enter the climate-controlled world of reading, complete with comfy chairs, coffee made-to-order, and no questions asked. Much of it had to do with the economics of the day: a rising middle class with more disposable income and a desire to look the part that their intellectual upwardly mobile lifestyle demanded.

But people are easily bored by upwardly mobile intelligence. It turns out that there are other things to do with money, including more recent concerns such as buying food and paying the mortgage. And while book reading is still happening everywhere, book lounging at places like Borders is one the decline. Part of it is the fickle consumer, but the bookstores are also to blame. If they add only limited value beyond being a storage shed for books, customers will opt for any shed.

Barnes and Noble seems to be doing much better, but I worry about it as well. It is bringing value to its stores with its new emphasis on the Nook devices. And it tends to play up the community aspects of its stores by offering extra-large coffee shops and dozens of benches near the magazine racks. But brick and mortar bookstores are still a lot more expensive than online sellers. For many years, I worked for a "VAR," a "value-added reseller." We sold computers, and while you could buy computers from Best Buy, our company offered services that enhanced the computer-buying experience. We were a lot more expensive than Best Buy, but we provided products and services that were worth the added cost. If Barnes and Noble plans to be around twenty years from now, they will have to ensure a value-added experience.

July 18, 2011

Review #4: The Republic

I like Plato. I had to read his dialogues about the death of Socrates as part of my college course work. In his Socratic passion story, I found logic, reason, and even rising emotions over the injustice of it all. Too bad he couldn't keep those same standards when addressing true justice.

Warning

This review contains spoilers. Here's a quick summary: Socrates defines justice. Nobody drinks hemlock. The end.

In The Republic, Plato once again picks up his Socrates sock puppet to address a topic of import to all mankind: What is justice, both for the state and for the individual? In the opening chapters, Socrates lets some of his contemporaries make feeble attempts at defining justice, including an assertion that justice occurs when the weak obey the strong. His friends also insist that those who practice injustice are happier.

In response, Socrates sets up the scene that will consume the rest of the book's several hundred pages. He defines a state, an imaginary country, in which justice will have its best chance. Here are some features of his just state.

It will take a village to raise the kids. Each child, especially those of the leaders, are raised in a communal setting, ignorant of which adults are their true parents.

Education is the key, with all children placed in state-run schools by age ten. Once there, all students will learn "gymnasium" (physical training) and "music" (soul training). Advanced students bound for societal leadership will also study the sciences.

Among the leader-class, all wives are shared in common. No more scandals!

Censorship of the arts is essential. Actors, writers, and poets may prepare no fictional content, especially defamatory stories about the gods. Thespians may narrate only; no imitation of humans or animals will be tolerated.

Each citizen will have his or her occupation selected by the state. Don't expect to change careers as part of a mid-life crisis.

Forget about fancy foods. And doctors may only render the minimal amount of care, with no life-prolonging measures.

The number of marriages allowed by the society is controlled, and those who are permitted to marry are selected by lot.

Despite being made of lesser stuff (Socrates' belief), women will be given equal rights in the society, including the right to exercise nude with the male soldiers.

Sounds like an ideal society, right? One of Socrates' associates points out that some may be miserable in such a society. Socrates insists that they will be the happiest of all. But in any case, the goal is not individual happiness, but national happiness. He also believes this structure will permit the rise of the philosopher-kings, the "savior" class that will act as guardians for the state and its people.

With the state now defined, Socrates explains how justice is the natural outcome, and how it has numerous advantages over injustice. That's fine and all, but I kind of stopped listening halfway through the communistic utopian dream sequence. When he first started discussing his imaginary state, I thought Plato was setting up a joke for a philosophical punch line. But he was dead serious. From my twenty-first century vantage point, it is so easy to see the failings of human nature and of centrally controlled societies. But for Plato, "the rule of a king is the happiest [for the people]." Plato sure knew his philosophy, but he really needed to get out and meet more kings.

Despite his governmental myopia, I did enjoy reading The Republic. Plato's Socrates can be arrogant at times, but mostly he is a gentleman with a good sense of self-deprecating humor. He wins converts not only through reason and logic, but through his good nature, something he mistakenly believes is a dominant trait in every human heart.

July 15, 2011

A Novel Challenge

Periodically, I will discuss other web sites that help bring the experience of reading alive. Today is the first such site: A Novel Challenge. Located on the Web at novelchallenges.blogspot.com, this site is a sort of meta-site for other reading blogs and other Internet destinations.

A Novel Challenge aggregates reading challenges from across the blogosphere. Sometimes called "TBR" (to be read) challenges, reading challenges are exactly what you think they are: an encouragement and commitment to read a set number or selection of books in a specific time frame. Sound familiar?

The great thing about the reading challenge on A Novel Challenge is that they are interactive, because they are blogs. And there are so many to choose from. In addition to the boring "read what you want, just read a lot" entries, the site is heavy with themed reads: fairy tales, Christian literature, Japanese books, books with a femme fatale; there are hundreds of categories to choose from. Many of the challenges are finished, but since the blogs are still available, you can use them as a jumping off point for your own reading. There are also many active challenges, with new ones posted all the time. Yours truly even got a mention. Yeah!

If you find that reading along with The Well-Read Man doesn't fill your daily requirement of book content, head on over to A Novel Challenge and start a fresh set of books today!

July 14, 2011

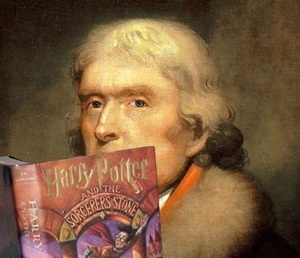

Keeping Up With the Jeffersons

I listen regularly to a podcast called The Thomas Jefferson Hour, a little bit of exciting history in my otherwise non-historical life. In this week's episode, the hosts discussed reading in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. President Jefferson was one of the most well-read men in all of the colonies, and he went into repeated bankruptcy in part due to his collection of thousands of books.

On June 11, 1790, Jefferson wrote a letter to a distant relative, John Garland Jefferson, who had inquired of the future president what he should do to prepare for a career in law, there being no law schools to speak of in America. Thomas Jefferson proposed a two-to-three-year reading course during which the younger Jefferson would spend close to eight hours a day rubbing his nose against paper and ink.

All that is necessary for a student is access to a library, and directions in what order the books are to be read. This I will take the liberty of suggesting to you, observing that as other branches of science, and especially history, are necessary to form a lawyer, these must be carried on together. I will arrange the books to be read into three columns, and propose that you should read in the first column till 12. oclock every day; those in the 2d. Form 12. to 2. those in the 3d. after candlelight….

The letter continues with a listing of around four dozen volumes of necessary reading. Most of them are law books, but the list also includes history, poetry, and treatises on government and morality. I had only heard of a handful of the authors (Bacon, Smith, Voltaire, Blackstone, Locke, Montesquieu), and only one of the books is even close to being on the Well-Read Man Project list, in the form of Locke's Leviathan. (For a full listing of the books, visit the podcast's episode guide and scroll down to show number 927.)

The show also mentioned Jefferson's voracity in reading. Some web sites indicate that he typically read two hours per day–about what I'm doing for the project. But Clay Jenkinson, the host of the podcast and an expert on Jefferson, said that the president spent many years reading 10 or 12 hours per day, and there were some days where as many as 15 hours were spent enjoying pages from his library. And he still had time to be a founding father. It's sort of depressing, and makes me wonder how Dancing with the Stars is going.

Jefferson wasn't all about books. He also spent close to two hours per day in exercise, including horseback riding. But it was reading that held a special place in his heart, and he saw the pursuit of books as the key to enhancing one's life. That's why he summed up his recommend reading course with an encouragement to gain knowledge and insight from the written word. "It is superiority of knowledge which can alone lift you above the heads of your competitors, and ensure you success."

July 13, 2011

The Problem with eBooks

Later this summer I will join with some friends for a weekend of camping in the mountains. It will be lovely: fresh air by day, star-filled skies by night; no phones, no lights, no motorcars. And no electricity. How will I charge my eBook reader?

I've always been a big fan of reading in nature. Many years ago, when I was visiting my wife's family in Japan, my father-in-law suggested that we take a day trip to a lake located in a national park about an hour's drive away. I started to pack for the mini vacation-within-a-vacation: swimsuit, towel, sunscreen, and two books. My father-in-law asked, "きみ、何やってるの。" After getting a blank stare from The American, my wife translated: "What are you doing packing all that stuff?" It seems that in Japan (or at least in my family), "going to the lake" is a shortcut for "going to the lake, driving around the entire circumference of said lake, stopping to take pictures at three or four famous picture-taking spots, and then returning home."

This time, I'm going to read, and since the Well-Read Man Project requires me to consume 42 pages per day of classic content, I can't avoid it. But I'm reading on an iPad, a device that uses batteries like my father-in-law uses lakes. If I run low on battery life at the campsite, there's no place to recharge. I blame Congress.

Running short of juice isn't the only problem with eBook readers. In the two weeks since I started reading on a tablet device, I've discovered some other inconveniences with the platform.

The various reading apps have limited note-taking and markup capabilities. Drawing a smiley face in the margin of a book is not an option.

The iPad is filled with non-reading distractions: YouTube, Angry Birds, the Brightness and Wallpaper panel in the Settings app.

Glare from nearby lights and anti-glare from on-screen fingerprints battle for my attention.

The constantly shifting page size prevents me from locating a memorable passage "by feel."

If you fall asleep reading, the iPad hurts your face a lot more than a typical paperback.

Despite these problems, I'm glad I opted for an eBook reader. It's such a convenient way of transporting and reading a sizable collection of great books. While reading at the campfire will be a race against time with the on-board battery, I'm confident I will get in my Recommended Daily Allowance of pages. If not, I'll just take a few quick pictures and go home.

July 12, 2011

Review #3: The Analects of Confucius

China has been a source of human ingenuity and development for all of recorded history. The Middle Kingdom developed fireworks, writing paper, playing cards, and Chinese food, all of them vastly successful. So what went wrong with Confucius?

Warning

This review contains no spoilers, not because I didn't want to give away the plot of the book, but because I think I lost the plot somewhere between the first few paragraphs and the end of the book. There, I said it.

The Analects of Confucius, the third book in the Well-Read Man Project, is a relatively short philosophical work that for the most part uses a Socratic-style question-and-answer format. But whereas Plato's version of Socrates engages in dialogues that slowly build to a philosophical zenith, Confucius' interactions with his students are all over the place. One minute he is telling you how to be a superior man, and the next minute he is refusing to eat his meat if it isn't cut up properly.

One thing that is clear from the text is that Confucius is wise. In addition to his disciples, members of the royal court come to question him on the meaning and duties of life. "The Master" answers them with common-sense responses about "filial piety" and the "rules of propriety," two of his favorite topics. The Golden Rule appears twice, including this version from Book V: "What I do not wish men to do to me, I also wish not to do to men." He also spends a lot of time speaking of "perfect virtue," especially for the "superior man."

What he doesn't do is say wise things in any coherent order. Confucius did not write down his own words. Instead, his students organized and edited his words after his death. It's too bad that he didn't offer Library Science or Journalism classes to them, because the text really needs some structure. The Master moves from one high idea to another in rapid succession, with some content repeated in different books (chapters) of the writings. In addition to statements on virtue and piety, Confucius spends a lot of time talking about other people, some that appear to be historically famous, and others that are known only within the circle of his students. There is no background given on any of these names. For instance, in Book XI, there is a quick review of four such personages: "Ch'ai is simple. Shan is dull. Shih is specious. Yu is coarse." Personally, I always thought Shan was kind of bright.

Other statements by the Master are completely out of context. In Book XVII, Confucius comes to Wu-ch'ang and hears some music. After comparing the music to a fowl being killed with an ox-knife, Tsze-yu chides his master by saying that "a man of high station…loves men." Confucius responds: "My disciples, Yen's words are right. What I said was only in sport." Who is Yen? His name doesn't show up at all in Book XVII before this point. Is it Tsze-yu? Is it a famous sage from history? This type of name banter appears constantly.

There is some political intrigue that invades the sayings of Confucius: a leader is killed here, someone replaces all members of the court there. The Master seems to have been someone of import in the royal court, but falls in and out of favor from book to book. He doesn't appear in Book XIX at all.

I didn't get much out of The Analects. There are many pious proverbs that are good for anyone to follow, but much of the text is random, confusing, and tedious. James Legge's 1910 translation may be part of the problem. He is a well-established Chinese language scholar, even having one of the main systems of writing Chinese script in the Roman alphabet named after him. But he probably got a C- or D+ in his English Composition classes, because the text is riddled with grammar errors and double negatives.

Yet beyond the issue of translation, The Analects is a difficult text. It's not that it is unworthy of being read; you should read it. But more than being read, it is the kind of text that can only be understood through years of study and immersion in its content. Perhaps this was the intent of Confucius' disciples all along.