Tim Patrick's Blog, page 30

September 23, 2011

Review #11: The Prince

In developing The Prince, Niccolo Machiavelli wrote either a small booklet of kindly advice on leadership for princes and other regional leaders, or he mocked those same leaders through the most deceptive satire ever written. Hundreds of years later, experts still can't decide which it is.

Warning

This review contains spoilers. But Machiavelli would tell me, the ruler of this web site, not to worry about it, since it is more important to be feared by readers than loved.

Machiavelli wrote his book in the early sixteenth century, a time of complex politics in Italy. Some of the most infamous leaders in history ruled in this era, including the Medici and Borgia families. The Protestant Reformation was still a few years away, and the church was actively mixing its ecclesiastical and temporal authority, much to the frustration of civil servant Niccolo Machiavelli. He worked in government, including advising the King of France for a time, and had plenty of opportunities to see the highs and lows of political life.

The Prince is written to princes, those who rule principalities, either by birthright, by appointment, or through usurpation and force. For Machiavelli, it doesn't matter how you, as a prince, obtained your power. All that matters is that you keep that power. The book's 26 chapters give blunt directions on how to accomplish that: "Men ought either to be well treated or crushed, because they can avenge themselves of lighter injuries; of more serious injuries they cannot."

And so it goes, all throughout the text. The author's recommendations are, at times, gentle, advising princes to keep the populace happy. But underneath is a sinister foundation, with all instructions aimed at keeping the prince in power, no matter the cost. He also says that a prince can engage in any type of moral evil he wants, as long as the citizens are satisfied that he is holy enough. Need to kill someone? Make sure you provide culturally-sensitive justifications. Want to live the rich life? That's fine, as long as the population still feels it is getting its tax-money's worth of life and happiness. But don't take their property, for "men more quickly forget the death of their father than the loss of their patrimony."

One reason that the book is deemed satire stems from the constant references to the then-current pontiff, Pope Alexander VI, and his son Duke Valentino, both of whom sought the power of the state. Machiavelli brings them up over and over again, both in terms of their successes and their failures. It all reads like an MBA-program case study series, with additional examples from the lives of Hannibal, Alexander the Great, and even Moses. But it all comes with a hint of mocking that just barely keeps you wondering if the author is serious or not.

The book also provides details on how to maintain an army, when to build alliances with foreign states, and how intelligent your advisers should be. Most of the advice would still work today, and in fact, does. One statement from Chapter 9 especially moved me: "A wise prince ought to adopt such a course that his citizens will always in every sort and kind of circumstance have the need of the state and of him, and then he will always find them faithful." In today's divisive arguments over government largess and entitlements, such advice seems fresh and relevant.

If you are looking for insight into sixteenth century European politics, or you need to know how to control your own little fiefdom at work, spend a few hours with The Prince.

September 20, 2011

Reason #3 to Read the Classics

I once read that the average American only uses about 3,000 different words in typical English conversation. But with over half-a-million words available in our language, it seems like a shame to waste such a great opportunity. Those 3,000 words include some of the most mundane and uninspiring terms ever used in speech, words like "those," "words," "include," and "mundane." No wonder we don't like to hear other people babble on.

Classic books provide an opportunity to discover new—old, actually—words, expressions that you can integrate into your daily conversations. What fun! I have made note of some new words encountered during the Well-Read Man Project.

Anent – about or concerning

Aqua fortis – nitric acid

Autodidact – one who engages in self-learning

Contumacy – stubborn resistance to authority

Dolorous – marked by misery or grief

Nugatory – of little consequence

Peculate – embezzle

Peradventure – perhaps, possibly

Perspicuous – easy to understand

Primogeniture – rights of inheritance for the firstborn child

Quiddity – true essence

Ratiocination – reasoned thought

Ruth – pity

Peradventure you found this quiddity of ratiocination perspicuous though nugatory? That's a ruth, because reading the classics doesn't just enhance our vocabulary, it shows us how we are failing to use those words we already know. At least that's what happened to me.

Having grown up in the church, I must have heard the parable of the Prodigal Son hundreds of time. It's the story of a wayward child whose father who doesn't give up on him. Some newer Bible translations give this story the title "The Lost Son," which makes sense, what with "prodigal" meaning "lost" and all. But in my recent read through Dante's Divine Comedy, I discovered that the fourth circle of Hell was dedicated to the Greedy and their polar opposites, the Prodigals. What? How can "greedy" be the opposite of "lost?"

And so I humbled myself and cracked open the dictionary. Prodigal. Noun. Characterized by profuse or wasteful expenditure. In other words—or in the correct words—someone who wastes money, whether he is lost or not. Color me dolorous.

I kept a list of new words to help me through this reading project. But I think it is a practice I will maintain well into the future. Many of the words I discovered are somewhat archaic, and it's unlikely that I will pepper my conversation with them. But even if I only keep them to myself, they still seem to have an impact on how I use the English language. And that's nothing to be ashamed anent.

September 16, 2011

Review #10: Revelations of Divine Love

On May 13, 1373, a thirty-year-old nun, near death from a painful, unspecified disease, had a series of visions. Twenty years later, feeling much better, she wrote down the visions so that God's faithful people would be able to love and worship him more. And so appeared one of the classics in the genre of Christian Mystic writings, Revelations of Divine Love.

Warning

This review does contain spoilers; it's not just a hallucination. Also, some of the images described below are somewhat graphic.

It may be Julian's own fault that she had these visions. When she was very young, she asked God for three things: (1) an understanding of Christ's Passion, (2) bodily sickness by age 30 to understand true suffering, and (3) three (figurative) wounds of contrition, compassion, and a steadfast longing toward God. And she received them all.

There were sixteen visions in all, fifteen occurring between 4:00am and 9:00pm on May 13, and one additional "be strong, God is with you" vision the next day. Most of the visions present some physical image of Christ's suffering on the cross, but others are more cerebral. The visions included:

Christ's head bleeding from the crown of thorns he wore. Meaning: Everything is held together by God's love, and so we should simply cleave to him.

Christ on the cross. Meaning: Recognizing our foul sins, we are to seek God and behold him.

God as a single, indivisible point. Meaning: God is in all things.

Christ's "plenteous" bleeding from the whippings he received. Meaning: Christ's blood reaches to all, whether on earth or in Hell.

The words, "Herewith is the Fiend overcome."

A stately feast at the Lord's house in Heaven, with all his "dearworthy friends." Meaning: There is a true bliss in being thankful to God.

God moving her about twenty times, quickly, between states of comfort and pain. Meaning: God keeps us secure in times of "woe and weal."

Christ crucified, covered in dried blood, and enduring internal pain from having all his blood drained or dried. Meaning: Christ understands our pain, because he went through so much more.

A little taste of Heaven, and of God the Father's presence, who has no bodily form. Meaning: The joy and bliss of heaven will be worth all the earthly pain.

The blood and water that flowed from Christ's pierced side on the cross. Meaning: God's endless love flows for us.

Mary, and Christ's love for her. Meaning: Christ's love of Mary is proof of his love for us.

Christ "more glorified." Meaning: Our souls will never rest until we experience him at this level.

A deep longing for God that is blocked by sin. During this vision, God told her to commit one sin so that he could show her his forgiving love.

Prayer requires "rightfulness" and "sure trust."

A young child springs from a dead body and flies to Heaven. Meaning: "It is more blissful that man be taken from pain, than that pain be taken from man."

A worshipful city where Jesus was sitting as king. Meaning: Jesus rests in our souls forever.

It was easy to see how such visions could bring her both fear and encouragement. It probably brought those same things to the larger church as well, since some of the conclusions she draws from the visions are at odds with church orthodoxy, while others are exciting messages of God's care for his people.

The book ends with a postscript by an unnamed scribe. He prays "Almyty God that this booke com not but to the hands of them that will be his faithfull lovers." Somewhat restrictive, what? For my part, I encourage you all, "faithfull lovers" or not, to pick up this Christian Mystic text and enjoy its moments of bliss and comfort.

September 14, 2011

Reason #2 to Read the Classics

On Monday, September 12, 2011, eight presidential candidates met in Tampa, Florida for the fifth Republican debate of the 2012 election season. The entire debate was about as long as a movie-of-the-week, and each candidate was given one minute to answer questions from the host, with a chance for a 30-second follow-up response. Barely enough time to come up with a good soundbite.

Long ago, we didn't select our national leaders based on a half-dozen one-minute quips. In the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, each of the two candidates spoke for ninety minutes: 60 minutes for the first candidate, 90 minutes for the second (!), and a 30-minute response for the first speaker. And no Wolf Blitzer. Amazing!

This inclination toward packaging important information in ever-smaller packages is a natural side effect of our fast-paced, microwavable, happy-ending society, a change that parallels the public's move from long-form books filled with complex ideas to half-hour sitcoms with limited intellectual content.

Grappling with complex ideas takes time. Trying to understand the philosophical foundations of our system of government by taking a pre-debate stroll through Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan, or attempting to make sense of terrorism by actually reading The Qur'an, should be a common activity for those who care about the future. Instead, we anticipate the upcoming season of Dancing with the Stars. The Twitterfication of human dialog is entertaining, but it has a devastating impact on society.

The selection of a presidential candidate is one such example. Most people never read the party platforms of the Democratic or Republican organizations, and therefore have little understanding of the long-range goals of each group. But since they haven't taken the time to understand the short- and long-term impacts of their own political positions, looking through those platforms wouldn't have any meaning for them anyway. And so polls repeatedly announce wide swings in undecided voters in the weeks running up to an election, and for so many, the time spent in the voting booth is an exercise in trying to recall which candidate had the most forceful TV commercial. To leave our biannual selection of leaders in the hands of a few talented ad executives is dangerous and idiotic.

The rise of the soundbite class has had many detrimental effects on American culture. But there is something you can do about it. Pick up a classic book, something that has changed the course of history, and read through its pages. The temptation will be to skim through the content, especially the more difficult passages. Instead, force yourself to deal with each complex passage as it arrives. Highlight. Take notes. Summarize. Outline. And then vote.

September 12, 2011

Review #9 Part 3: Paradiso

This is the conclusion of my review for Dante's Divine Comedy. To read the first part, Inferno, click here. To read the second part, Purgatorio, click here.

When we last left Dante, he was making a quick departure from Purgatory, a land on the outskirts of Heaven, but with the temperament of Hell. Now it's time for Heaven in the real world. Virgil, his guide thus far, won't be making the trip due to his literal lack of faith. Instead, Dante's childhood sweetheart, Beatrice, takes up tour guide duty.

Hell was arranged as a series of concentric circles; Purgatory had every-rising terraces. In Heaven, it's spheres, each one represented by (or actually) one of the spheres of the solar system. In each sphere, Dante meets increasingly holy residents of Heaven.

Moon – Those who broke their vows to God, such as nuns who left their convents. They made it to Heaven, but just barely.

Mercury – Those who trusted God, but still managed to achieve earthly acclaim through their ambition, and thus didn't rise too high on the Heaven scale.

Venus – The lovers, who may not have been as temperate in their emotions as God would have preferred.

Sun – The abode of the wise theologians and fathers of the church. At this level, we start to see the souls as beings of light, arranged into various shapes. In the Sun sphere, the souls have arranged themselves into three concentric circles.

Mars – Here be martyrs and crusaders. Get it? Mars is the god of war, and those at this level died as warriors in the faith. This tie between each planet's traditional mythos and Dante's identification of those who lives there appears in each sphere of Heaven. The light-soul shape is the cross.

Jupiter – At this level are those who were righteous kings and rulers on earth. King David is here. The souls in this sphere form themselves into the shapes of letters, although some of them also form the shape of an eagle.

Saturn – Those who spent their time in contemplation.

Fixed Stars – Representing faith, hope, and love. Mary, the Apostles, and Adam meet Dante here, although they (and everyone else) are also located in the highest Heaven farther on.

The Primum Mobile – The source of all movement in the universe. Dante introduces us to the different levels of angels, but then insists that we not get too interested in them.

The Empyrean – God's throne is here. All believers sit in chairs, each chair placed on the petal of a flower. Mary is at the center of the most significant of the flowers, surrounded by a thousand angels (lucky Mary).

Dante finally gets to see God in His Trinitarian form, a set of three colored circles, one of which has a human face. And then the book ends; no summary, no Aesop-style lesson, no closure.

As in the two other sections of the book, Dante spends a lot of time condemning Italy and Florence for their wayward actions. He also take time, through the fictional voice of his great-great-grandfather, to shout from the rooftops the great history of his own family.

When taken together, the three sections of The Divine Comedy provide a fanciful glimpse of the afterlife, and also provide a statement on the phases through which an earthly soul passes as a person lives out sinful, mediocre, and saintly faith experiences. Along the way, Dante adds discusses official church teachings on various topics, although I was surprised to see so much emphasis on earthly accomplishments tied to one's pole position in Purgatory and Heaven. Works-salvation is not one of the core tenants of the church. There are also hints of fatalism, especially in Chapter 8 of Paradiso, another idea that falls outside of Christian orthodoxy.

I found the three sections of the book to be commentaries on life phases of a kindly yet curmudgeonly believer, such as Dante appears to be. Inferno represents childhood, a time of discovery, but with parents and other authority figures constantly punishing you. In Purgatorio, Dante portrays youth and young adulthood, teaching that the world is filled with unfair and judgmental experiences. Finally, Paradiso brings him to adulthood and old age, where his curmudgeonly griping about the world brings him both joy and pain, but he must still pass through the experience as is. Overall, the book had a tinge of Oscar the Grouch in it.

Perhaps I should have left the book with a more uplifted feeling, getting to see God and all. But Dante kept bringing the reader back down to the baser instincts of mankind, harping on this political event or that wicked leader. His descriptions of the various punishments for those in Hell and Purgatory go way beyond any pain and suffering mentioned in the Bible. He also has little good to say about the church or the monasteries of his day, although it was a complex time in church history.

I much preferred C. S. Lewis' book The Great Divorce, which provided a different perspective on Heaven and Hell as seen by a living human just making a short visit. Lewis has much more "comedy" in his work, but he also keeps the focus where you expect it to be: on God and his Heaven. Dante keeps flipping around between Heaven, Italy, Hell, Florence, Purgatory, Pisa, and the personal lives of his contemporaries. Perhaps Dante wanted to show what choices were available for eternal life. For me, he accomplished the opposite, showing that a little bit of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven resides in each person.

September 7, 2011

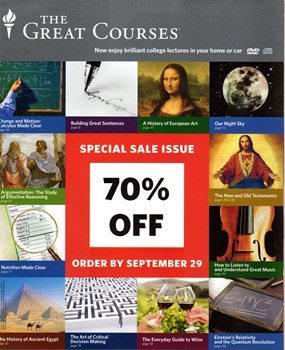

Great Courses!

So you want to spend some time immersed in the classics, but you also need advice on finding the right wine for your upcoming dinner party. No problem! Look no further the the latest offerings from the Great Courses, a catalog of college-style lectures. Don't have time to crack open a book? That's also not a problem, because the courses, according to the web site, are available in "DVD, audio CD, and other formats."

I received this organization's catalog in the mail yesterday, and it is chock full of lecture courses by actual university professors. From the History of European Art to The American Civil War, the courses cover all of the major disciplines. And yes, there is a course on selecting a wine for dinner.

Many years ago, I bought such a course from a series offered by Barnes & Noble. "What Would Socrates Do? History of Moral Thoughts and Ethics" was the title, recorded by Professor Peter Kreeft. I had read some of Kreeft's books years ago, and one of my favorite writings from his pen is Between Heaven and Hell, a mock philosophical discussion between President John F. Kennedy, Brave New World author Aldus Huxley, and noted Lion, Witch, and Wardrobe expert C. S. Lewis, all of whom died on the same day.

I enjoy Kreeft's fresh writing, and the lectures were just as upbeat. But I just couldn't get into the content. It was a college-level course, but I was listening to each lecture as I took my morning walk around the Well-Read Neighborhood. I discovered that walks are not conducive to advanced learning. To grow through such a lecture, you need to take notes, ponder the ideas, wrestle with the material. In short, you need to go through a lot more pain than you get from a set of Nikes with poor arch support.

If you are looking to advance in your studies, and you have a few dozen hours to make available for lectures, take a browse through the Great Courses catalog at thegreatcourses.com.

September 5, 2011

Review #9 Part 2: Purgatorio

This is a continuation of my review for Dante's Divine Comedy. To read the first part, Inferno, click here.

As Dante and Virgil escape from Hell, they enter a world that is better only by degrees. In Hell, the God-forsaken inhabitants suffer punishments in keeping with their earthly sins, with no hope of escape (unless you are Dante). In Purgatory, escape to Heaven is assured, but the sin-tinged punishments are still there.

Dante and Virgil first arrive in "ante-Purgatory," a place for those who waited until their deathbeds to convert to Christianity. These souls will spend hundreds of years here, and then they will still need to sit a spell in Purgatory, possibly for hundreds of years more. Off in the distance, Heaven is visible as a mountain that reaches beyond sight. Those stuck in ante-Purgatory don't even bother heading toward the mountain because, what's the point?

As in Hell, Purgatory is arranged in sections, variously called "circles" or "terraces." As the two poets ascend each level, they encounter souls who must perform penance based on their earthly sins. I don't really understand this system, not being Catholic. Perhaps it's that thing about payback and female dogs, but I digress.

The seven terraces in Purgatory exist to expunge the Heaven-bound from seven specific sins.

Pride

Envy

Anger

Sloth

Greed

Gluttony

Lust

These might look familiar if you do them, or if you are familiar with "The Seven Deadly Sins," a list of vices compiled by Pope Gregory I seven centuries before Dante wrote his masterpiece. Bad news for those believers who engage in multiple Deadly Sins: You must perform penance for each of those that apply.

Eventually, Dante makes it to a pre-Heaven boarding area after passing through a cleansing yet hot and painful fire. ("Into molten glass I would have cast me to refresh myself" is one of my favorite lines from the book.) At this point, Virgil departs, not being allowed in Heaven due to his pagan state. Instead, Beatrice, the love interest from Dante's younger days, takes up Sherpa duty.

I found Purgatorio to be a little less compelling than Inferno. All the fascinating punishments of poetic justice are still there; those at the Gluttony level have to spend centuries without food or drink. The condemnations of Italian life, especially of those living in Florence, are there as well. Dante, the continual life of the party, meets even more people he knew and admired back on earth.

A lot of time is spent delving into various theological issues and popular discussions of the day: Are humans innately good? Do the prayers of those still alive reduce time spent in Purgatory? What is the nature of free will? Is nobility inborn or applied during one's lifetime? These are all important discussions for Dante's readers. But I just couldn't get away from one nagging idea: That believers aren't faring much better in Purgatory then those in Hell. At the very least, it seems like a poor bit of marketing for the Gospel, and from my Protestant point of view, possibly heretical.

The story and this review continue next time with a discussion of Paradise. If at all possible, find a way to reduce your stay in Purgatory so you can keep up with the commentary.

August 31, 2011

Review #9 Part 1: Inferno

Dante's Divine Comedy is an important book in world literature. Not only did it touch on human struggles both contemporary and eternal, it ushered in the use of common languages in literature. Before its publication, most major works in the West were penned in Latin. Dante broke the mold by issuing his verse in Italian, establishing a precedent that would eventually send Latin to a death all its own. For my reading, I used the English translation made by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Warning

You are entering a dark place of spoilers.

The Divine Comedy documents a similitude of Dante, where he travels through the afterlife regions of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Each region appears as a distinct section in the full book. I will divide this review into the same three parts. Welcome to Inferno, the first 34 chapters of the book describing Dante's descent into Hell.

Dante, it seems, had led a life of cowardice, and Beatrice, his former love interest who has since died, sends the poet Virgil to shake some sense into his heart. And what better way to do that then to send someone to Hell. "All hope abandon, ye who enter in!" says the sign as Virgil and Dante begin their descent

In the Inferno, Hell is a series of concentric circles, with those whose sins were mild consigned to the outer, higher circles, and those with grievous transgressions placed in the innermost, tortuous pits. In case you were wondering about potential destinations, here are the sins assigned to each circle.

Limbo, containing generally good people who were never baptized, or who never sought after God. When he's not playing tour guide, Virgil lives here with other famous poets.

The lustful. As is true throughout all the circles, Dante runs in to some people he knew back on earth. Dante seems to know pretty much everyone in Hell.

The gluttonous. While here, Dante points out that Hell is a place of poetic justice, where "all these suffer like penalties for the like sin." The punishments experienced in Hell are descriptive, imitative, or inverse of the earthly sin.

The greedy and the prodigals, those who hoarded riches and those who spent without limit. I discovered that I really never knew what "prodigal" meant before.

The angry. The remaining four circles are contained within the "City of Dis."

The heresiarchs, those who invented or promoted heretical beliefs.

The violent offenders. This section is divided into three parts, for those who were violent towards (1) others, (2) themselves (suicides), and (3) God (blasphemers).

The frauds. This circle has ten "bolgias," or ditches, each containing ever worsening perpetrators of fraud, including mediums, flatterers, and liars.

The betrayers. Lucifer himself resides here, as does Judas Iscariot, the betrayer of Jesus Christ.

As the two poets descend into the underworld, the punishments they witness become progressively worse. While those in the first circle suffer only mild discomfort, those in the inner reaches of Hell are bitten by serpents, have limbs torn off, have their heads twisted on backwards, or in the case of Judas, must spend eternity with his head in a frozen lake while his body flails about on top. I found myself feeling sorry for this wretched lot, as the punishments inflicted on them by Dante were much worse than anything hinted at in the Bible.

Another source of suffering was Dante's constant discussions of Italian politics. He was particularly fond of chastising the entire city of Florence for its pride and extravagance. He also found plenty of opportunities to criticize various popes, some of whom didn't have much nice to say about Dante back on earth.

The story and this review continue next time with a discussion of Purgatory. Hope to see you there, instead of in Hell.

August 29, 2011

Reason #1 to Read the Classics

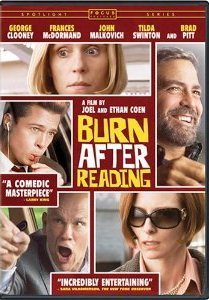

A few days ago I watched the 2008 movie Burn After Reading, staring George Clooney, Brad Pitt, John Malkovich, and Tilda Swinton. I enjoy stories with a little political intrigue, and this movie's core plot of some local opportunists getting their hands on the secret documents of a former CIA operative sounded like a match for my interests. Plus, it has the word "reading" in the title.

You really can't trust the descriptions you read on Netflix.

The movie was bad. Not just because of the shallow characters or the empty plot. Not just because the ending felt like someone lost the last few pages of the script and couldn't get the actors to return once they were found. The movie was bad because of the dialog. Here's a sample of some of the witty banter between two characters during an especially significant scene.

Now give me the f___ing floppy or the CD or whatever the f___ it is…

As soon as you give us the money, d___wad!

You f___! Give it to me, f___!

You f___er.

I know who you are, f___er!

You're the f___er!

That's some impressive writing. A note in the Internet Movie Database documents some of the efforts the writers took to bring out nuance and style: "Excluding the end credits' song, the F-word (and its derivatives) is used 62 times, mostly by Osborne Cox (John Malkovich) and Harry Pfarrer (George Clooney), including 6 times in the first 2 minutes." The problem wasn't the excessive R-rated language; even in real life some people do have potty mouths. The problem was that when you took away the four-letter words and the characters stumbling for something to say and the truly unimportant dialog between a woman and her plastic surgeon, there wasn't much left. When the movie ended abruptly, I popped a multivitamin into my mouth to stem the degenerative effects the film had on my personal health.

And then I reached for a classic. Some classic books, like some older films, lack modern sensibilities about plotting and character development. But they make up for it in language. Books that become classics tend to have a healthy dose of great language, even nonfiction treatises on some political or scientific research. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times," Charles Dickens' great opener from A Tale of Two Cities, is a classic all unto itself, even though nobody knows what the rest of the book is about.

As I pass through the books of the Well-Read Man Project, I've been encouraged by both the content of each book, and by the way the content passed from printed text to my swooning mind. One of my favorite passages so far comes from The Qur'an, a book with many ideas that exist outside of my personal worldview, but that nonetheless communicates those ideas with classic sensibilities.

If all the trees on earth were pens and the ocean were ink with seven oceans behind it to add to its supply, yet would not the words of Allah be exhausted. (31.27)

It's not as action packed as the fight over a floppy or a CD or whatever it is; it's better.

So many classic writers took the time and effort to build language that would speak to readers on its own, independent of the message being conveyed. Here is the opening text of Dante's Inferno, a few lines of verse that draw you in to the story, despite having little to say about the larger work.

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straight-forward pathway had been lost.

Ah me! How hard a thing it is to say

What was this forest savage, rough, and stern,

Which in the very thought renews the fear.

So bitter is it, death is little more;

But of the good to treat, which there I found,

Speak will I of the other things I saw there.

It's not just works of poetry and verse that show beauty in language. Here's a random passage I flipped to in the philosophical nonfiction work The Republic, by Plato.

These two harmonies I ask you to leave: the strain of necessity and the strain of freedom, the strain of the unfortunate and the strain of the fortunate, the strain of courage and the strain of temperance.

I don't remember what this section was even talking about, but I can still enjoy Plato's use of point and counterpoint to convey so much thought in so few words. The dialog above from the Clooney-Pitt blockbuster could have employed some of these same language skills to bring out the richness of the English language.

Pray, pass freely across the chasm between our persons the item that beholds your hands, be it floppy, be it CD, be it whatever medium…

Nay, it must needs remain with my person until the treasure of your deep financial storehouses be released in due exchange.

You cad, sad must be the mother that bore you. I demand receipt of that device, lest I unleash a torrent of curses upon you and upon the ticket-paying audience that does now attend!

Bite me, d___wad!

The next time you need to get away from the cares of the world for a few hours, go see a movie. Just be sure you have a classic book nearby to mend the damage.

August 23, 2011

Review #8: The Qur'an

The Qur'an, the book dictated by Mohammed to his scribes and followers in the early seventh century, is not at all what I thought it would be like. I expected a fount of anger, with calls to "kill the infidels" every other page. And while there was a fair amount of military language and statements blasting those who oppose Allah, it wasn't the terrorism-laden free-for-all that you think about when watching the evening news.

The book includes 114 chapters, or suras, each representing a divine revelation given to Mohammed, and repeated verbatim for the benefit of his followers. They are arranged in order somewhat by size, with the longest suras appearing first; Sura #2 contains 286 verses; the last sura has just six. Each sura includes a mix of exhortations, doxologies, historical accounts, glimpses of heaven, and lists of expected behaviors, all with the goal of differentiating between those who submit to Allah's will, and those who, in their arrogance, reject Allah. This differentiation is clear in every chapter, and helps explain the "us against them" tone that affects those outside of Islam.

The content in The Qur'an is somewhat repetitive, with the same stories appearing over and over again for emphasis. It's possible that even if half the text was removed, not a single idea or phrase would be lost from the overall book. Some of the major themes and elements include the following.

As mentioned earlier, the bulk of the text focuses on differences between those who submit to Allah, and those who oppose his will. Nearly every chapter identifies the traits of the believers, and the current and future sufferings of those who turn their backs on Allah and his messenger, Mohammed.

To exemplify correct and incorrect behavior, the text draws on historical accounts, many from the Old and New Testaments. Moses, Abraham, Lot, Noah, Jonah, David, Solomon, Jesus, Mary; all of these biblical VIPs and more fill the pages of The Qur'an. Some of the accounts parallel those in the Bible, while others seem to be new stories.

God did select the Jews as his Chosen People, and even now, the text insists that some Jews are faithful to Allah. But because of their collective sins (either those recorded in the Bible or based on conflicts during Mohammed's day), Allah rejected them. Christians are likewise recipients of a true Gospel from heaven. But the text confirms Allah's rejection of them as well, due to their blasphemous belief in a "trinity."

The text is directed clearly at a male population. Women are mentioned, but only in the context of how they are to be treated by men. Verse 33.59 is the one that instructs women to be veiled when in public.

While there are no lists of laws like those found in the Hebrew Torah, there are rules and regulations sprinkled throughout the book. Alcohol and gambling are not allowed (2.219), but divorce is acceptable (2.230 and elsewhere). Also, information on how to conduct daily prayers (4.43ff) and the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, appears in a few chapters (such as 2.196). The Old Testament lists specific and detailed laws, but those found in The Qur'an are more general "just be righteous" pronouncements.

In addition to angels and humans, Allah created jinns from the "fire of a scorching wind" (15.27).

As a Christian, I was surprised at the amount of content discussing Jesus, Mary, and John the Baptist. Some of it was not biblical at all, including the account in Sura 3 of Jesus creating living birds from clay, a story that comes from the second- or third-century Infancy Gospel of Thomas. And while The Qur'an rejects the idea that Jesus is God, it affirm Jesus' virgin birth, the miracles he performed, and his resurrection from the dead.

Although there are no blatant calls in the text to wipe out unbelievers (Sura 9 comes the closest, although with Allah-imposed restraints; Sura 47 says to "smite the necks of the unbelievers who come to fight you"), the text is decidedly militant. But it is mostly from Allah's actions. For those who reject Allah's will, they can expect misery in this life, and an eternity of fire, iron maces, and no help from anyone else. For those who fight alongside Allah and are loved by him, Heaven is described repeatedly as a garden, one flowing with rich rivers, fruit in abundance, and "voluptuous women of equal age" (78.33).

The Qur'an is the most important book in Islam, but it's not the only one. Other texts record the words and acts of Mohammed, and are used to define Muslim laws and cultural norms. A fuller understanding of Muslims requires involvement with these other books. But for the Western reader interested in going beyond the nightly news soundbites, a read through The Qur'an is an essential step in understanding the history and people of Islam.