Tim Patrick's Blog, page 29

October 25, 2011

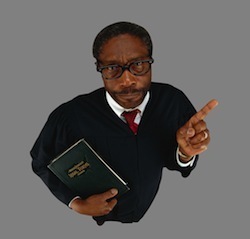

Review #15: The Road to Serfdom

The road to socialism is paved with good intentions, but it always leads to totalitarianism, or even fascism. So says Friedrich A. Hayek, author of The Road to Serfdom. Hayek wrote this study of collectivism in 1944, in the midst of a battle against German fascist tendencies and the rise of a collectivist mentality in Russia. While these two nations serve as examples for Hayek's ideas, he writes England and America, warning them of what is to come if they seek similar paths.

Hayek understands the desire for economic security and equality. He even favors some limited welfare for those unfortunates who cannot care for themselves. But he warns against taking such feelings too far. The problem is not the intentions or goals, but the implementation and the inevitable results.

In order to bring equality of outcomes to all members of a society, it is necessary to define the moral state of every aspect of that society. How much should nurses be paid? How much free time should a person have each day? What is the right amount of milk for a family of four? What is fair compensation for those who find themselves out of work? The problem isn't in asking these questions; the problems are (1) in expecting a one-size-fits-all answer to such questions, and (2) thinking you can enforce the answers without devolving into dictatorial rule.

Hayek leads the reader through various aspects of socialist thought, driving home two main conclusions: (1) collectivism never works because it is impossible for a central body to adequately manage the millions of decisions required for a society to function; and (2) attempts at collectivism always lead to totalitarianism, because deviations from the core plan represent unknowns that increase complexity for central planners. It's not just economic and political elements that must be controlled. Collectivists and socialists must manage even ordinary parts of life, including travel, entertainment, and communication.

Unlike books such as Orwell's 1984 that attempt to evoke a visceral response to totalitarian systems, Hayek's content is very sedate and ordered. There's no fear-mongering here, just professorial outlines of the actual results of a system that seeks to wrest control away from the natural work of markets and prices. But he does include strong warnings to his British (and later, American) audience. Although a strong middle class acts as a brake against socialist ideals, he cautions that some in England had (during his time) already accepted the false truths of a collectivist utopia. And such utopias are always lead to serfdom.

October 21, 2011

The Grandson of a President

[image error]

I have been doing some research on American presidents for another project, and I was shocked to learn something about . At first, I was shocked that there was even a president named John Tyler. Who knew? He was number 10, also known as "His Accidency" due to his being the first unelected president. He inherited the office from , who died just one month after inauguration.

Tyler was president from 1841 to 1845, two decades before Abraham Lincoln. When Tyler was a youth, George Washington was still running the country. But would you believe that John Tyler has a grandson that is still living? He's not a zombie, or a Dorian Gray wannabe. His name is Harrison Ruffin Tyler, currently about age 82, and he still lives at Sherwood Forest, President Tyler's retirement home in Charles City County, Virginia.

President Tyler lived from 1790 to 1862. His first wife, Letitia Christian Tyler, died while he was president, but not before having eight children (of course not all in the White House). Three months later, he started courting Julia Gardiner Tyler, thirty years his junior, and they married about one year before his presidential term ended. She had seven children with John. Her child number 5 (John's child number 13) was Lyon Gardiner Tyler, who lived from 1853 to 1935. John Tyler was 63 at Lyon's birth.

Lyon, a president of the College of William and Mary, had two children of his own that lived into adulthood. The second one, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, was born in 1928 when Lyon was 75. What a spry family!

The Sherwood Forest house is open to the public, and Harrison Tyler himself offers guided tours of the home and the family. To set up a tour, or to learn more about the Tyler family, visit www.sherwoodforest.org.

(The picture above shows John Tyler and his grandson. The portrait of John Tyler was painted by George Peter Alexander Healy in 1859, and hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. The picture of Harrison Tyler appeared in an August 3, 2008 article from the Tyler (Texas) Morning Telegraph.)

October 19, 2011

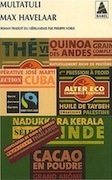

Review #14: Max Havelaar

You've never heard of Max Havelaar. I hadn't either until this project, and there are some good reasons for that. The first is that it was written in Dutch. I don't read Dutch, and neither do you. The second is that the English translation is out of print. The third, and most important, is that it deals with some European drama from over a century ago.

Despite these setbacks, it is still a worthy novel to read. The focus of the book is the Dutch colonization of Java, and how this occupation corrupted the native Javanese leaders and oppressed the people. He explains this through a biography of the fictional Max Havelaar, a Dutch official in charge of a small region of Java. Havelaar sees the corruption going on around him and, due to his honest and generous nature, has no choice but to intervene. Unfortunately, this decision leads to his eventual ridicule and poverty, as you might expect. The book does implicate Dutch officials in corrupt colonization practices, the but main accusation of the book is that Western colonizers act as enablers for native chiefs, giving them an official sanction to oppress and exploit their own people.

Max Havelaar is the Uncle Tom's Cabin of nineteenth century Netherlands. It has a hero who ends up worse by the end of the story; it has human enslavement; it has characters that turn a blind eye to problems that don't touch them directly. The similarities are there. Multatuli—the pen name for author Edward Douwes Dekker—even mentions Uncle Tom's Cabin in his book. He does an admirable job at putting a human face on the colonization problem, but Max Havelaar is no Uncle Tom's Cabin. Multatuli seems to realize this since, in the last four pages of the book, he usurps the narration and makes a direct Occupy-Wall-Street-style plea to the reader.

Some of his characters, especially the entertaining and some-time narrator Batavus, are blatant caricatures that surpass plausibility. Also, the author tends to gloss over the complexities of Javanese society before the events recorded in the book, including before colonization. Because of these and other issues, I didn't find the book as compelling as it could have been. But the Dutch people did. The publication of Max Havelaar coincided with nationwide concerns about the role of the Dutch in third-world affairs. While changes were already being considered in Dutch international policies, Multatuli's book was the straw that broke the serf's back.

While Multatuli does tend to simplify the entire argument, Max Havelaar is nonetheless an influential and important book that had a significant impact on world affairs.

October 14, 2011

Dennis Ritchie, Programmer, Author

This past weekend, Dennis Ritchie, software developer and technical author, passed away at age 70. Arguably even more important to our computer age than Steve Jobs, Mr. Ritchie was unknown to most of the hundred of millions of people who benefit from his work every day.

In 1969, along with a handful of other Bell Labs employees, Ritchie developed the multitasking operating system UNIX. It has since become the basis for every implementation of Linux, Google's Android OS, Apple's mobile iOS, and the Macintosh platform. While Microsoft Windows does not inherit directly from UNIX, some of its internal concepts do, and another now-obsolete operating system from Microsoft, Xenix, was a UNIX clone.

After the success of UNIX, Ritchie and fellow UNIX developer Brian Kernighan developed the C programming language. Even more pervasive than UNIX, C development has impacted almost every computer on earth in one way or another. Back in 1983, my first job at Motorola–a company which had its own bit of sad news this week with the passing of Bob Galvin, son of the company's founder and the man that oversaw the development of the world's first cellular phone–involved writing programs for UNIX using the C language. It was a time of complex systems and thick documentation; the Macintosh wouldn't come out for six more months.

Kernighan and Ritchie literally wrote the book on C, calling it The C Programming Language. It introduced essential concepts such as language syntax and how to write a "Hello, World" program. Although C as a language is generally straightforward, there are some aspects of its use that are no fun to memorize. One such feature is Order of Evaluation, the rules that determine whether, in a complex mathematical expression, you should perform addition or multiplication first. I never bothered to memorize the long table of rules; instead, I memorized the page number (although I can offer no proof of that 28 years later). So in those pre-PDF days, I had my fingerprints all over Ritchie's book.

Many of today's most popular computer languages, including C#, Perl, and Java, are all descended in some way from C and the UNIX system that was C's playground. And we have Mr. Ritchie to thank for them. As an unknown computer geek, Dennis Ritchie was no Steve Jobs. He was better.

October 12, 2011

Review #13: Communist Manifesto

Karl Marx struggled. In the nineteenth century, he looked at the world around him and saw disarray. "The history of all hitherto existing society," he believed, "is the history of class struggles." And there were many who agreed with him, including Friedrich Engels and laborers from across the globe. Yet they were not united. So in 1848, Marx, Engels, and some of their associates came together in London to pen a Manifesto that would join the workers of the world in revolution.

You might be familiar with Communism, the one-party system exemplified by the Cold War-era Soviet Union. As an economic system, it turned out to be less than desirable for those workers it sought to raise up. With the advantage of hindsight, it's easy to see the defects in the central control of a national economy and its dependence on a small group of bureaucrats making millions of pricing and labor decisions every single day. But in the mid 1800s, this was unknown to Marx and Engels.

In the first of the Communist Manifesto's four chapters, the authors lay out the core problem: the world was unfair, with so many industrialists taking advantage of so many workers. It wasn't just that the powerful bourgeoisie controlled the money and factories. In Marx's and Engels' view, the ruling and business classes conspired to destroy all core societal institutions. For example, marriage and family life existed, but it had been transformed into an economic equation, a reserve from which factories could draw out male and female workers, both young and old. Private property existed, but not for proletariat, the class level of the common man.

The solution? Violent revolution. As stated in the second chapter, "The immediate aim of the Communists is the…formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, [and] conquest of political power by the proletariat." In this transformation, the Communists would not restore the broken societal institutions. Instead, they would demolish them completely through "the abolition of bourgeois individuality, bourgeois independence, and bourgeois freedom." Here are just some of the changes admitted to by the Manifesto.

The abolition of private property, or at least of property that can be used to "subjugate the labor of others."

The elimination of the "bourgeois" nuclear family; "we replace home education by social."

No more marriage or monogamy. Instead, there would be a "community of women" not tied to any man, a sort of "mob with benefits."

The erasure of countries and nationalities so that one nation can no longer exploit another.

The removal of religious, philosophical, and ideological ideas that conflict with Communism.

The centralization of the means of production, transport, communication, and finance into the hands of the state.

This simple lists makes the changes look almost harmless. But what the group called for was the complete and utter upheaval of every aspect of society and individual life.

The final two chapters identify other groups and movements in history that sought the same ends as the Communists. The difference between those groups and the Communists are twofold: (1) the Communists focus on how local struggles of such groups can be merged at the international level, and (2) other groups were wimps because they didn't attempt violent revolution.

I found it hard to read the Communist Manifesto without bringing my American worldview into the mix. I witnessed the collapse of the Supreme Soviet, and I still see how those living in the modern "utopias" of Communist Cuba and North Korea experience a level of oppression and subjugation many times baser than anything Marx and Engels mentioned. Industrialization did include abuses of the working class, and the authors were right to link those abuses to the unjust feudal systems of the past. But I wish that Engels and especially Marx (who was married with children) could have looked past the struggles and complexities of European socioeconomic history, with all of its wars and church-state imbroglios, and seen what a truly free republic could accomplish for the workers of the world. If they had foreseen such a system, perhaps those who were dragged through the various implementations of the Communist Manifesto would not only "have a world to win"; they would have won it.

October 10, 2011

Review #12: Leviathan

[image error]

From 1642 to 1651, England was engaged in a great civil war that temporarily nullified the British monarchy. In the midst of this chaos, Thomas Hobbes crafted Leviathan. In this seminal work, Hobbes defines a commonwealth, a government founded on the mutual agreement of its citizens, and defined by a social contract.

Hobbes called this government framework "Leviathan," likening it to the biblical sea monster from the book of Job. In Hobbes view, a commonwealth is a living creature, an all-powerful union of its members. The head of this creature is the sovereign, the representative leader of the entire community. Hobbes allowed for this leader to be a single monarch or a set of men meeting in congress. But in either case, the sovereign's power over it citizens was absolute, a necessary requirement to enforce the social contract.

Leviathan appears in three major sections. The first part discusses Man and his nature. Although Hobbes is dead serious in all of his descriptions, I couldn't help laughing at the crazy biological and medical concepts that he puts forth as facts. From Hobbes' seventeenth century standpoint, the human body is a machine that reacts to stimuli coming into it through the five senses. External elements such as light and words push on the body's senses, and continue to move through an elaborate system of tubes and vessels, until they reach the brain and other target organs. But they don't stop there. When you dream at night, you are experiencing the continued movement of previously perceived events that impacted your senses. It's all very mechanistic.

Hobbes' purpose in explaining these systems is to show the essence of mankind: his desires and appetites, his reflections of good and evil, and most importantly, his rights as an individual. Some of these rights are inalienable—they cannot be given up—but others can be deferred to a commonwealth, an idea that leads to the second section of the book.

Since the commonwealth—Leviathan—is a creature, it has rights just like man does, although these rights are passed on from those in the commonwealth. These rights culminate in a strong sovereign who acts on behalf of the citizens to define laws, enforce contracts, mediate justice, issue rewards and punishments, and carry out peace and war. Because of the need to enforce the rules of society, the power of the sovereign is absolute; he can do no wrong and he cannot be corrected or arrested. He as the power of life and death over his citizens, although he cannot take away an inalienable right from any citizen.

In the third major section, Hobbes defines a Christian commonwealth, one where all of the citizens accept the Christian doctrines, and its leaders perform both governmental and ecclesiastical duties. In Leviathan, there is no separation of church and state, although there may have been a separation of church and Hobbes, since many of his beliefs were clearly heretical.

Some of the book's key themes were incorporated into America's founding documents. The idea natural rights—including rights that cannot be taken away—appear in The Declaration of Independence. Other ideas were not so lucky. As in Plato's Republic, the society defined in Leviathan is somewhat utopian. Although Hobbes allows for representative leadership in the form of a congress, his descriptions most closely match those of a single king, and a slightly tyrannical one at that. One of the key rights that Leviathan has is that its form of government, once established, cannot be changed by the will of the people, an idea rejected in both the Declaration and in the American Constitution that followed it.

For those interested in the ideas that shaped the modern West, Leviathan is an essential read. If you can get past the medical malpractice and the pre-Webster spelling rules, you will find a treasure of important ideas about your rights, and the rights of all societies.

October 6, 2011

Why Steve Jobs Missed His True Calling

I just installed a new kitchen this week. The 1970s-era oak was great, but there comes a time when you have to say goodbye. The new cabinets are modern, clean, good looking, and have that new-granite-counter-top smell. And although they lack the sticky oil texture of what I discarded, they also aren't as spacious or as functional as my old cabinets. I wish Steve Jobs had made my furniture.

Steve would have been a great cabinet maker. An artisan of technology, I can see him directing a team of craftsmen to design the iCabinet, the next innovation in kitchen storage systems. Just imagine these features adorning your cook space.

Thin cabinet walls. Just look at how thin they are.

Strong, unibody construction for a snug fit with your refrigerator.

Storage for thousands of third-party dishes (upon approval).

Now available in white.

Of course, upgrading to new cabinets every year would become tiresome after a while. And don't get me started on the two-year contract with AT&T. But they would be great to look at, would store all my dishes in style, and would begin an entire iCabinet industry. Bluetooth silverware trays. Door covers that attach to magnetic strips along the top. Perhaps some cabinet maker in the Pacific Northwest might even produce a new "Cabinet 7 Mango" series that would compete with Steve's product.

Sadly, Steve Jobs has passed on. And although he transformed consumer electronics, animated movies, and store signage, he wasn't able to fulfill his true calling in home-life furniture. And for all that, I will truly miss Mr. Jobs.

October 5, 2011

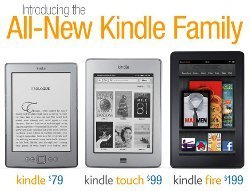

Get eBooks From Your Library

The Well-Read Man is the Well-Remodeled Man this week as we revamp our kitchen and bathrooms. So I only have time for a quick update today on a new feature available from your local library: Kindle eBooks. A few weeks ago, Amazon.com released a portion of its Kindle eBook collection to more than 11,000 public libraries for limited loans. Many of these libraries already had books available in the more generic ePub format, but this is the first time that bestsellers and other recent books will be available in Amazon's proprietary format for free reading.

I checked through the selection available at my local library. Unfortunately, none of the fifty books in the Well-Read Man Project are included. The closest thing was a book by project-list author Salman Rushdie. Also, there was a tourist guide for Las Vegas, perhaps not that different from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, another book on my reading list.

To download Kindle library books, visit the web site for your local library. You can find out more about the program here on Amazon.com's web site.

September 29, 2011

Kindle on Fire

Amazon is flexing its well-read muscles again, this time with the release of three new fourth-generation devices: the cheaper Kindle, the touchable Kindle, and the beautiful Kindle. Prices start at an amazing $79 (with ads), and top out at $199 for the advanced model–less than I paid for my first generation Kindle device.

The entry-level Kindle device is a basic reader, with an eInk screen, and–this is new–no keyboard. It has a few basic buttons for controlling the features, but I can't imagine trying to enter notes about a book by cursoring to each letter. But it's affordable. The Kindle Touch is just $20 more, and definitely worth it if you have any use for its on-screen keyboard.

Topping out the collection is the Kindle Fire. It's pricier, but you get cool for those two Benjamins. iPad-like touch interface, access to books, movies, TV shows, email, probably even blenders and skinny jeans from Amazon's non-book shops. Color. Did I mention that it's cool? Only the basic Kindle is available now; the Touch and Fire won't be out until November.

To read more about the new devices, visit the Kindle Store.

September 27, 2011

Banned Books Week

This week marks the thirtieth anniversary of Banned Books Week, an annual remembrance of attempts to censor published books, both great and not so great. For those Americans who still read books, it's a time to dust off those old copies of The Great Gatsby and Harry Potter and give them the once-over once again.

I found a list of the most commonly banned books on Wikipedia. Three of the books in The Well-Read Man Project are identified as targets of frequent censorship. I thought that many more of my selections would make the bonfire pile, but it turns out that many banned books aren't great, so they never found a place on my list of reading options. Being offensive doesn't always equate to being great literature.

Here are the three books from the project that I will read with one eye looking out for rabid mobs.

All the King's Men , by Robert Penn Warren

The Catcher in the Rye , by J. D. Salinger

The Jungle , by Upton Sinclair

To find out more about Banned Books Week, visit the American Library Association's information page.