Tim Patrick's Blog, page 25

June 15, 2012

Review #43: One Hundred Years of Solitude

You think your family has problems? To get some perspective, try a visit with the descendants of José Arcadio Buendía. The focus of Nobel prize-winning Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez’s book One Hundred Years of Solitude, the Buendía family line defines the word “accursed,” destroying pretty much every virtue in the process of its short 100-year existence.

The story takes place Macondo, Columbia, founded by the family’s patriarch. José is a sometimes eccentric but relatively stable, hard-working man until he comes in contact with a band of traveling gypsies. Filled with a lust for gold, José delves into alchemy, eventually losing his mind in a mixture of toxic fumes and his craze for riches. But before he goes insane, he manages to father three children, each with their own forms of insanity.

From then on, it’s the normal story of a small family-oriented town, if you consider murder, incest, military rebellion on a national scale, drunkenness, selling lottery tickets based on the color of farm animals, evil banana plantations, navigating boats without a viable water source, fathering seventeen kids all with the same name, and hundred-year-old prophecies normal. If the Seven Deadly Sins had a poster family, this would be it.

The family, to put it mildly, is complex. It’s so complex, in fact, that the book begins with a chart of the family tree, without which the book would be indecipherable. Not willing to limit this complexity to the overall story, the author is sure to inject every paragraph and nearly every sentence with a meandering resolve, moving from character to character, from scene to scene, and from thought to thought, all within the span of a dozen or so words.

As with Salman Rushdie’s book Midnight’s Children, One Hundred Years of Solitude tells the story of a nation by linking it to specific individuals. And as with Rushdie’s book, the story is nearly impossible to relate to unless you are already familiar with the minutiae of the nation exemplified by the book. At least in Midnight’s Children, Rushdie peppered every chapter with references to news headlines paralleling the protagonist’s life. Except for some minor links to political turmoil, Márquez assumes you can figure out the relationship between the family and Columbia’s history on your own. You can’t. Unfortunately, this means that the rich undercurrent of meaning in the novel is lost on the typical reader. And that’s really too bad, because if Columbia has a history that is as complex and intricate and prophetical as the story itself, it must be a tremendous place.

June 12, 2012

Review #42: The Bridge on the Drina

The protagonist of Ivo Andrić’s book The Bridge on the Drina never speaks. That’s because it’s a 180-meter-long bridge. In this interesting take on four hundred years of Bosnian history, the Nobel-prize-winning author discusses cultural, historical, regional, and religions events within the context of a large stone bridge built across the Drina River in present day Bosnia and Herzegovina. The actual bridge spanned the river in 1577, and the story takes the reader from a point six decades before its construction up until the start of World War I.

In the early sixteenth century, Ottoman forces round up Serbian children as part of a regular “blood tribute.” One of those young slaves grows up to become a Grand Vizier and a great Ottoman military leader, but suffers from chest pains that started when he was kidnapped and ferried across the Drina River near the town of Višegrad decades earlier. To remove the pain, he builds a majestic bridge at the site of his river crossing (it works). As the gift of a Grand Vizier, the bridge comes to play an immediate and important role in the nearby town, a role it maintains for the next 350 years and beyond.

Over the centuries, the townspeople experience war, love, religious conflicts, political strife, sudden changes in national leadership, and the impact of events occurring hundreds of miles away. As a major link between the East and West, the bridge remains a focal point of all of those events, until its role (and the town’s related role) is diminished with the rise of late-nineteenth-century technology and socialist changes. The bridge and the people who live near it endure plagues, wars, floods, and tyrants. When an explosion rips away a section of the bridge in 1914, it is an apt parallel of the explosion ripping through the Serbs and Turks living in that area of Bosnia.

The Bridge on the Drina is an excellent work, transforming a lesson in European history into a living, breathing narrative of the people who experienced that history firsthand. The book is a work of fiction, but it communicates in summary form the true core issues that permeated Bosnian society from the sixteenth century up to the first War to End All Wars. Like the book’s river-spanning edifice, the story is one that is meant to endure for centuries.

June 8, 2012

Ray Bradbury, RIP

Popular fantasy and science fiction author Ray Bradbury passed away earlier this week after a long illness. He was 91. A diverse writer, Bradbury penned beloved books such as Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, TV and movie scripts (including some Twilight Zone episodes), and he even had his own television show in the 1980s. Along with Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, he was part of a small group of writers commonly known as “Science fiction authors that average people have actually heard of.”

While none of Bradbury’s works appeared in the Well-Read Man project’s final list of fifty books, Fahrenheit 451 did appear in the full list of book candidates. Also, one of his short stories, I Sing the Body Electric, takes its title from a poem by Walt Whitman, from his Leaves of Grass collection, which is part of this reading project.

For Ray Bradbury’s official web site, click here.

June 6, 2012

Review #41: Kokoro

Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro is a sad book. Written in 1914, two years after the death of Japan’s Emperor Meiji, the story follows the lives of a handful of people living near the end of that imperial era. The Meiji Restoration—a set of society-transforming reforms initiated by the emperor—brought Japan from its traditional pre-industrial hierarchical system into a new form that sought to emulate Western norms. Kokoro expresses some of the isolation and loneliness that stems from being caught in the middle of this transformation.

Warning: This review contains spoilers.

This isolation is immediately clear in the naming of the book’s major characters: they have none. The narrator befriends an older man whom he calls Sensei. Sensei is married to Ojosan (a description instead of a name), who had lived with her mother (Okasan, or “Mother”), and so on. The only character with a name is K, the narrator’s friend, and it is only a pseudonym so Sensei can talk about him, and perhaps keep him at an emotional distance. While titles are a common form of appellation in Japan, the complete lack of names is indicative of the human distance the characters have inside them and in the larger culture.

The story is in three parts. In the first, the narrator builds a friendship with Sensei while the former is a university student in Tokyo. In Part 2, the narrator returns home his family in the countryside to spend time with his dying father. The third part consists of a long letter written by Sensei to the narrator. Although the first two parts consume more than half the book, the core story really exists in Part 3. In it, Sensei tells his own life’s story just before he commits suicide.

Read from a Western perspective, Kokoro is difficult to process. Sensei’s suicide stems from the shame he feels over an incident from his own university years. What is most striking about his shame, though, is his inability to deal with it in a way that could help him or others. In fact, many of the characters have a similar inability to cope with anything that has even the slightest tinge of shame tied to it.

Having spent some time in Japan myself, I have been taught about the differences between “shame cultures” (like Japan and other Asian societies) and “guilt cultures” (America and much of the West). In America, sin is bad, but it can be forgiven, as exemplified through the dominant religion, Christianity. But in a shame culture, sin (or actions that have significant negative impacts for individuals or groups) carries a lasting stigma. In the story, Sensei believes the only way to expiate for his shame is through suicide—the shedding of his own blood—an action that is paralleled in the book and in history by the ritual suicide of General Maresuke Nogi during the funeral of Emperor Meiji.

The story is a hopeless one. The book ends abruptly at the end of the letter in Part 3. This sudden stop lefts many other aspects of the story incomplete, paralleling the incomplete feeling of someone separated from humanity. The narrator’s father is left dying, but to what conclusion? Even the narrator’s response to Sensei’s letter and suicide are missing, although one can ponder the narrator’s own eventual suicide at the shame he feels in not being available to Sensei at his demise. “Kokoro” means “heart” in English—the emotion term, not the medical one. In Kokoro, the reader will only find one that is isolated and broken.

June 1, 2012

Review #40: Possession

A. S. Byatt’s Possession is by far the most structurally diverse book within the Well-Read Man reading project. Written just over two decades ago, in 1990, the novel covers several genres, and includes content that ranges from unedited, personal diary entries to scholarly journal articles.

The story revolves around a hundred-year-old mystery: Did famous nineteenth century author Randolph Ash have an intimate relationship with his contemporary Christabel LaMotte? That’s what literary scholars Roland Michell and Maud Bailey want to find out. As they unearth previously unknown letters and documents, and travel between England and the Continent, a half-dozen other researchers, some of whom want the glory and fame of discovery for themselves, force Roland and Maud into an ever-closer relationship.

As a novel, the book tells an enjoyable story of two people growing to care for each other in the midst of their normal vocations. But what makes this book classics material is the extent to which the author draws on multiple forms of content to tell the story. Beyond the core narrative, the two-dozen or so chapters include newspaper articles, poems, diary entries, peer-reviewed journal articles (complete with footnotes), fairy tales, love letters, and scribbled notes. The materials purport to come from multiple authors, mostly from characters in the book. But in truth, Byatt writes everything. She even invented epigraphs for the start of every chapter, transferring authorship to those in the book’s dramatis personae. Her command of each included fiction and nonfiction genre is impressive. In short, the book is a research nerd’s dream.

The invented research materials do consume a large part of the text. But for those not so inclined to spend time studying like a university professor, the book also includes the basic forms needed for mystery, romance, and historical fiction genres. All in all, it’s a good book, one that will quickly take “possession” of any interested reader.

May 25, 2012

Review #39: Middlemarch

Middlemarch, written in 1871 by author Mary Anne Evans under the male nom de plume George Eliot, concerns the people and events in a British provincial town at the birth of the Victorian era. Although written in the form of a typical nineteenth century novel, the book is really a collection of social criticisms, bound up in story form.

The tale itself is very complicated, à la Desperate Housewives, with an ensemble cast of characters that are regularly intruding into each other’s lives. Unlike works by other popular British authors such as Jane Austen, class distinctions do not play a significant role in Eliot’s book. Instead, local rumormongering and the impact of national politics in a local town, medical advances, and the role of money in families set the stage for several of the book’s conflicts.

The problem with the book is that Ms. Eliot regularly interrupts the story with scholarly articles on the ills of British culture. As a woman forced to publish under a male pseudonym, it makes sense that she would include in the book her own views on the role of women. While she does insert some of those ideas into the narrative, she finds this unsatisfying, and repeatedly makes room for three-page essays on whatever happened to be bothering her about society on any given day. Even in the main storyline, the text is thick and plodding, due to her constant harkening back to how every character is impacted by the world around them. She explains everything in intricate detail instead of letting the lives of the characters tell their own stories.

Her statements and opinions on current events are interesting and satisfying. She isn’t simply a crank; she has valid and well-reasoned things to say about the injustices she sees around her. So why doesn’t she just say them instead of cutting and pasting them into some story she decided to write? Instead of pondering the merits of her arguments, I found myself dismissing those blocks of thick commentary, wondering when she was going to get back to the story.

Despite these stylistic flaws, Middlemarch is a great book, mostly because it says great things. The core story could have been massaged into a shorter Harlequin Romance. But with the political observations embedded into the text, the book becomes a useful treatise on society and its norms during the Victorian era, some of which are still hotly debated today.

May 21, 2012

Incorporating the Classics

This week I started biking to my office a few times per week. I’ve done the round trip journey twice now, and I already have a new perspective that comes from moving at a slower pace, being out in the fresh air, and nearly getting mowed down by a rude driver.

It happened as I was trying to cross one the major roads in my city. I patiently waited at the light and, when it turned green, I moved across in a safe, careful manner. That is, until I had to veer out the way of a driver who decided red lights didn’t apply to him. I shouted out a surprised “Be careful,” which prompted the driver to stop and call out things I can’t print here since my mom reads these articles.

Later, when the desire to commit various vengeful felonies had passed, I found myself wondering how the Vicar of Wakefield would have handled this setback. I was starting to worry that spending a year with these great works was having no impact on me when suddenly one jumps into one of my life-and-death activities.

In Oliver Goldsmith’s book, the vicar is a lighthearted, water-off-a-duck’s-back fellow. He loses his riches, his possessions, his children one by one, his house, and even his freedom, but he never strays far from his Job-like patience. Certainly, something as minor as getting run over by a 2,000-pound motorized vehicle would have left him calm and placid. And now that I’ve read the book, I have to ask how I can incorporate the vicar’s outlook on life into my own.

But then there are other, competing examples from the project’s books. Oedipus would have murdered the man on the spot. Karl Marx would have blamed the man’s obvious bourgeois upbringing. Captain Ahab would have chased the man to the ends of the earth. And Gregor Samsa would have turned into a bug and died. Which of these should I use as my example?

This is something that keeps bothering me about the classics. Certainly they are meant to impact me. But in several cases, the stories and details are so specific that they could never apply to my own life. I was not raised as a discarded orphan, nor did such an orphan ruin my life. So what am I to do with the example of Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights? I’m not an international spy, so how can I apply the events of Alec Leamas’s life into my own? I understand that these books are examinations of the general human condition, and that specifics don’t always apply. But sometimes the overall themes don’t seem to apply, either.

There are no easy answers when it comes to dealing with the books in the Well-Read Man project. It will take a lot of thought and consideration, to the point of distraction. Perhaps that’s what bozo was thinking about when he careened past me. One can only hope.

(Image Credits: bicyclethailand.com)

May 17, 2012

Review #38: Vanity Fair

Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1848 novel, follows the lives of two young women, one troubled, and the other really troubled. Beyond the interesting history of these woman and their relations, the book claims to get at the heart of what is really wrong with the world.

Amelia Sedley and Rebecca “Becky” Sharp attend school together. Amelia comes from a well-to-do family; Becky, not so much. Financial tragedy soon strikes Amelia’s household, bringing her down to Becky’s level. But Becky has a plan to succeed, and if she needs to take advantage of Amelia’s family, her own upper-class employer, or even peers and royals to do it, so be it.

This is a romance, and in the end, good triumphs over evil. But the book is much more than that simple outcome. As we see Becky lie, cheat, and steal to move up in society, the author repeatedly asks the question: Is it worth it? Are the vanities of life worth anything at all? Do they satisfy? Do they last? For all its questioning of the high life, you might as well be reading the Bible. But here is a moral questions for the ages, packaged in a well-written nineteenth century British entertainment.

This isn’t the only book to ask such questions. Of the half-dozen eighteenth and nineteenth century books in which I placed Vanity Fair for this reading project, all of them mention, at least in passing, the trouble of vanity and its dangerous allures. And it’s not just the individual temptations like those that John Bunyan showed in the original Vanity Fair from his book The Pilgrim’s Progress. These collected authors indicate that vanity lies at the heart of all major problems in European society, from the wants and desires of the lower classes all the way up to the construction of the royal systems that dominated British and Continental leadership of that era.

Could this warning against visiting Vanity Fair be just as relevant today? Of course; people never change. In an election year, media will be filled with just such desires. One side looks to the wealth to be had by business advancement and self-sufficiency; the other side lifts up the power and promise of a bureaucracy that can provide goodies to those who want them. Vanities still abound. But are they worth it?

May 10, 2012

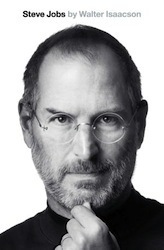

Review: Steve Jobs

I am not a Mac Fanboy. Sure, I have an iPhone, and an iPad, and I’m writing this review on a MacBook Pro. I bought them because the hardware is fast, good looking, and will last for many years. The software, while adequate, isn’t as user friendly as it appears on the surface. Come to think of it, this all describes Steve Jobs himself as presented in Walter Isaacson’s biography of the late Apple founder and CEO.

In Steve Jobs, Isaacson provides a chronological look at the life of one of the key technologists of our era. Born into a humble middle class family, Jobs quickly demonstrated his clear yet confrontational genius. A man of vision, he also drove others to near-nervous breakdowns with his in-your-face “you suck” mannerisms. In nearly every chapter, Jobs comes across as a sanctimonious, vicious, hard-hearted jerk.

And yet, he’s not. Like Apple’s software, there is a veneer of beauty and elegance that comes from the core, despite the usability issues for those needing to deal in a more direct manner with the product or the man. Like Apple’s devices, Jobs’ appearance is a marvel in design. It’s not necessarily from a natural appeal; cell phones were originally bricks of plastic with bulky components; Steve Jobs was originally a barefoot vegan with a wild mop of hair that shocked common sensibilities. But through careful design and continual improvements, Jobs and his products evolved into something that we all wanted.

Steve Jobs is a little different from other biographies I’ve read. Other than Edmund Morris in Dutch—the pseudo-first-person account of a life with Ronald Reagan—biographers whose books I’ve consumed tend to be omniscient yet distant commentators. But Isaacson is all over this work; he interjects himself into the story regularly. At first it disturbed me. But then I realized that Jobs did the same thing to me. I was content with my Windows desktop and my Motorola flip phone. But Steve wouldn’t have it. “Tim Patrick uses an iPhone,” he said, and somehow earned the right to enter my storyline.

A tremendous personality like Steve Jobs deserves a tremendous biography. Isaacson’s work on Jobs is very good. Not tremendous, perhaps, but very good in its detailed coverage of a man who preferred not to be covered in detail. The book dares to remove the custom screws holding down the cover on the Steve Jobs image. Periodically, some aspect of that inner spark in Jobs’ life twinkles through the pages, especially in the closing two or three chapters. By the end, you get a clear vision of a man with clear vision.

May 8, 2012

Review #37: Wuthering Heights

Wuthering Heights, the mid-nineteenth century romantic work by Emily Brontë, is pretty depressing. Even the name invokes a bad day. “Wuthering” refers to strong, gusty winds. Who would name their house after a tornado? But this is what you find in the house that bears the book’s name. The story does have a bit of a happy ending, but just enough so that you don’t pound the book to a pulp with your fist while screaming, “Why, Heathcliff, why?”

The narrator is Mr. Lockwood, staying at Thurshcross Grange, a house on the same property as Wuthering Heights. He isn’t a party to any of the events in the book, but his gossipy housekeeper, Mrs. Dean, has been there since it all began, and boy can she talk. Many years ago, when her mother worked for the Earnshaw family as a nurse, Mr. Earnshaw brought home an orphan boy during a business trip to Liverpool. Unfortunately, the family doesn’t really do the whole “care for the orphan” thing well, and the child, Heathcliff, grew into a bitter, vengeful man.

Years later, Heathcliff took his revenge, slowly working to destroy the various relationships in the family. But then there’s Catherine, Mr. Earnshaw’s daughter, raised alongside Heathcliff. Can his passionate love for her keep him from ruining everyone at Wuthering Heights? Or will he put his desire for retribution above his own heart? Or will he go crazy before he can accomplish his goal?

It’s all of these. The ending is as complex as the character of Heathcliff. It’s a satisfying read, but in its role as a classic, I wonder how it is supposed to transform me. Do I relate to the rejected orphan consumed with hate? Or to young Linton, whose maltreatment leads to a life of apathy? Or to the many characters who claim to love those near to them, but only do so until minor troubles disturb daily life?

I think I most relate to Mr. Lockwood, the narrator, whose interest in the characters remains only as long as the story seems interesting. When everything is resolved, he departs Wuthering Heights as if it never impacted him. Even Heathcliff grows tired by the end, telling Mrs. Dean, concerning his plans for revenge, that he has “lost the faculty of enjoying their destruction.” While the storytelling was dramatic, and the depictions of revenge were heartless and cruel, by the end I felt little remaining of the story, as if a wuthering wind had passed through my thoughts.