Rick Just's Blog, page 81

October 8, 2022

The Town of Falk's Store (Tap to read)

Falk’s Store was a place. That’s not an astonishing pronouncement but hold on. I don’t mean that it was a store, so thus a place. I mean that it was a store that became a town’s name: Falk’s Store.

Vardis Fisher’s 1938 Idaho Encyclopedia lists it as a ghost town in Payette County. I’ve seen it listed as “Falk Store,” and also under the town name “Falks.”

Nathan Falk, one of the brothers who owned what became known as Falk’s Idaho Department Store, or Falk’s ID, in Boise, had a store in Payette County that snagged the local post office for the community in 1872. Falk’s Store, which would lose its possessive apostrophe under naming conventions today, was located on the Payette River between Emmett and Fruitland.

Falk’s Store was also a station for the Utah, Idaho, and Oregon Stage Line, giving it a revolving customer base. In addition to its namesake store the town had a ferry, a hotel, a saloon, a blacksmith shop, and a boot and saddle shop.

Nathan Falk’s store is said to have prospered in Falk’s Store, Idaho for several years. A 1922 fire marked the end of town. Nothing remains of it today, although there is a nearby bridge that carries the name Falk's Bridge.

The Falk’s Store in Falk’s Store, circa 1892. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection

The Falk’s Store in Falk’s Store, circa 1892. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection  An ad for the stores in Boise and along the Payette, 1874.

An ad for the stores in Boise and along the Payette, 1874.

Vardis Fisher’s 1938 Idaho Encyclopedia lists it as a ghost town in Payette County. I’ve seen it listed as “Falk Store,” and also under the town name “Falks.”

Nathan Falk, one of the brothers who owned what became known as Falk’s Idaho Department Store, or Falk’s ID, in Boise, had a store in Payette County that snagged the local post office for the community in 1872. Falk’s Store, which would lose its possessive apostrophe under naming conventions today, was located on the Payette River between Emmett and Fruitland.

Falk’s Store was also a station for the Utah, Idaho, and Oregon Stage Line, giving it a revolving customer base. In addition to its namesake store the town had a ferry, a hotel, a saloon, a blacksmith shop, and a boot and saddle shop.

Nathan Falk’s store is said to have prospered in Falk’s Store, Idaho for several years. A 1922 fire marked the end of town. Nothing remains of it today, although there is a nearby bridge that carries the name Falk's Bridge.

The Falk’s Store in Falk’s Store, circa 1892. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection

The Falk’s Store in Falk’s Store, circa 1892. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection  An ad for the stores in Boise and along the Payette, 1874.

An ad for the stores in Boise and along the Payette, 1874.

Published on October 08, 2022 04:00

October 7, 2022

Governor Signatures (Tap to read)

It’s Ephemera Month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

A governor’s signature on a bill can be one of the most important things they do. That same signature on a proclamation can have some level of importance, or it might be largely ceremonial. Today’s post is about the signatures that you may not have known that governors do.

There are collectors of gubernatorial signatures lurking around out there. I was one of them for a while. I collected a few from sitting governors when I came across them while working for the State of Idaho. Those were mostly proclamations and minor correspondence. Since I had a few of those, I decided to see if I could collect gubernatorial signatures from past governors.

It’s easy to start a hobby like that these days thanks to eBay. You can create a search bot that alerts you whenever the words governor, Idaho, and signature or autograph pop up. I collected a few signatures that were created during the course of business, such as a canceled check from George Shoup, Idaho’s last territorial governor and first state governor. Mostly, though, the signatures existed because someone wrote to the sitting governor and requested one.

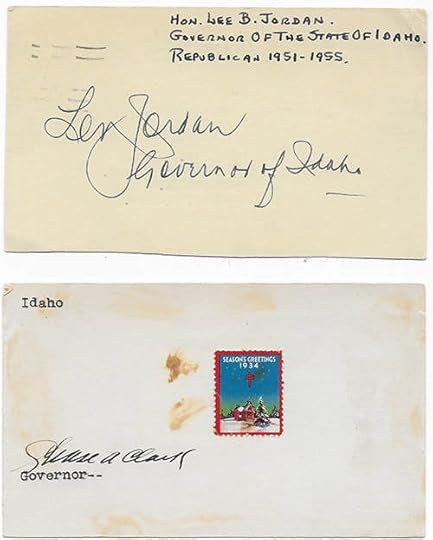

Most governors answered requests like that by signing a blank card or even the outside of an envelope that was returned to the requestor. Here are a few samples.

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.

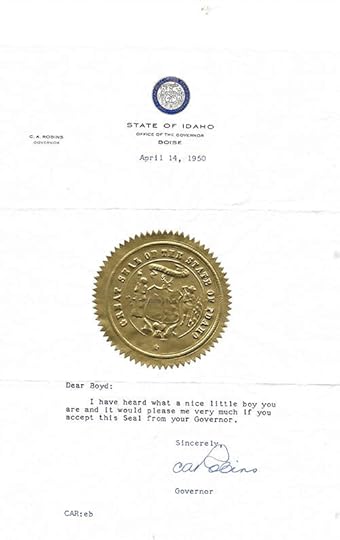

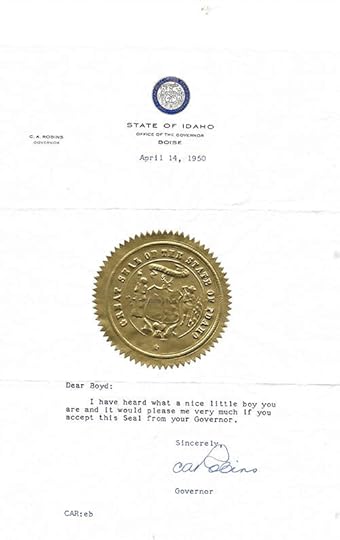

Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.

Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

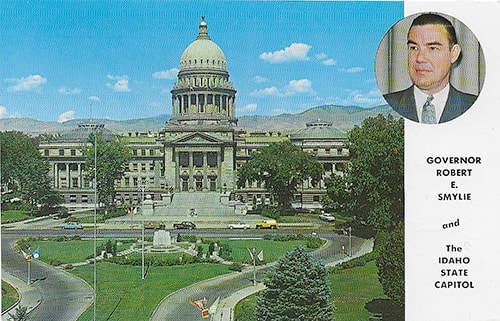

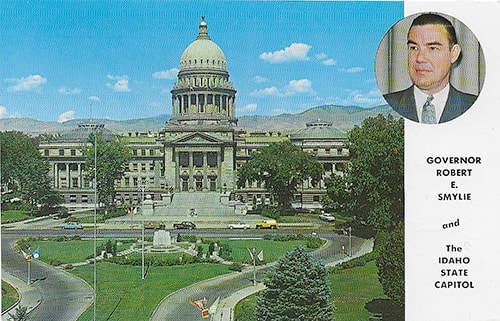

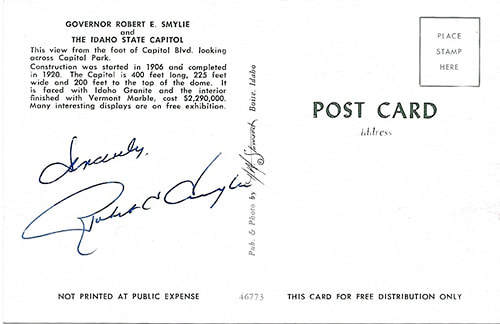

Governor Robert E. Smylie sent a postcard with his photo and a picture of the statehouse.

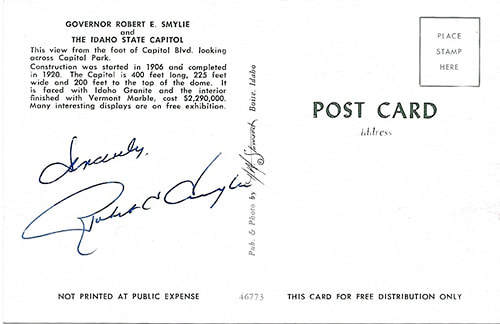

The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

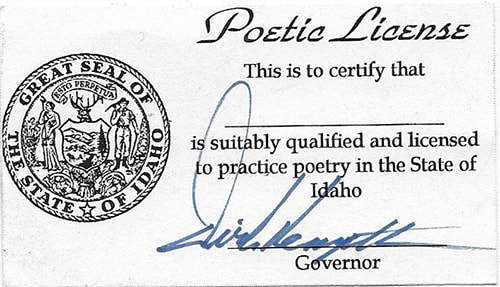

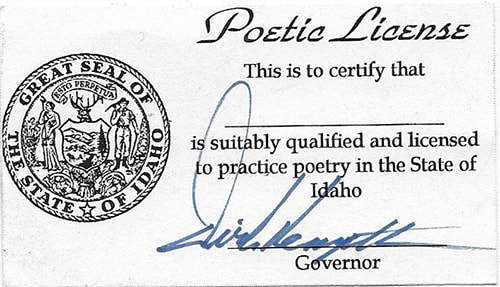

This final example is the size of a business card. It’s my favorite. I was going to spend the day at the Elk City elementary school teaching the students about poetry. It was something Tom Trusky had cooked up for a National Endowment for the Arts grant. I thought it would be fun to give the kids each a “poetic license” signed by the governor. Much of a governor’s correspondence is actually signed by a machine that does a beautiful job of replicating a signature. I had arranged ahead of time to have his staff run the 50 cards through the machine. When I got to the office, we found that the machine was out of order. I was headed for Elk City the next day. Since the machine was down, I’d have to just forget the idea.

One of the governor’s aides excused himself for a moment. When he came back, he led me into the governor’s office. Dirk Kempthorne had agreed to sign each one individually while I waited. I was surprised that he took the time to do that for me and for the kids in Elk City.

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.

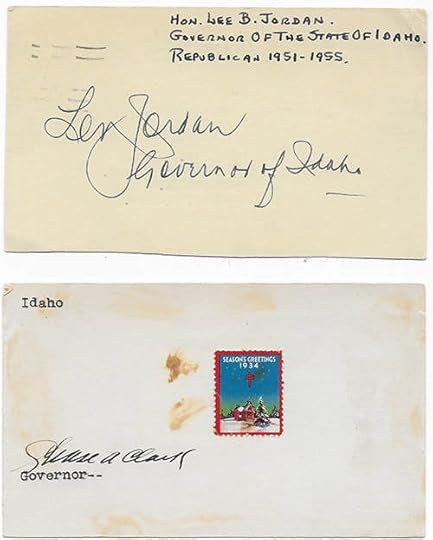

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.  Governors Len B. Jordan and Chase Clark went for simplicity.

Governors Len B. Jordan and Chase Clark went for simplicity.  Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.

Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.  Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

This final example is the size of a business card. It’s my favorite. I was going to spend the day at the Elk City elementary school teaching the students about poetry. It was something Tom Trusky had cooked up for a National Endowment for the Arts grant. I thought it would be fun to give the kids each a “poetic license” signed by the governor. Much of a governor’s correspondence is actually signed by a machine that does a beautiful job of replicating a signature. I had arranged ahead of time to have his staff run the 50 cards through the machine. When I got to the office, we found that the machine was out of order. I was headed for Elk City the next day. Since the machine was down, I’d have to just forget the idea.

One of the governor’s aides excused himself for a moment. When he came back, he led me into the governor’s office. Dirk Kempthorne had agreed to sign each one individually while I waited. I was surprised that he took the time to do that for me and for the kids in Elk City.

A governor’s signature on a bill can be one of the most important things they do. That same signature on a proclamation can have some level of importance, or it might be largely ceremonial. Today’s post is about the signatures that you may not have known that governors do.

There are collectors of gubernatorial signatures lurking around out there. I was one of them for a while. I collected a few from sitting governors when I came across them while working for the State of Idaho. Those were mostly proclamations and minor correspondence. Since I had a few of those, I decided to see if I could collect gubernatorial signatures from past governors.

It’s easy to start a hobby like that these days thanks to eBay. You can create a search bot that alerts you whenever the words governor, Idaho, and signature or autograph pop up. I collected a few signatures that were created during the course of business, such as a canceled check from George Shoup, Idaho’s last territorial governor and first state governor. Mostly, though, the signatures existed because someone wrote to the sitting governor and requested one.

Most governors answered requests like that by signing a blank card or even the outside of an envelope that was returned to the requestor. Here are a few samples.

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.

Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.

Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

Governor Robert E. Smylie sent a postcard with his photo and a picture of the statehouse.

The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

This final example is the size of a business card. It’s my favorite. I was going to spend the day at the Elk City elementary school teaching the students about poetry. It was something Tom Trusky had cooked up for a National Endowment for the Arts grant. I thought it would be fun to give the kids each a “poetic license” signed by the governor. Much of a governor’s correspondence is actually signed by a machine that does a beautiful job of replicating a signature. I had arranged ahead of time to have his staff run the 50 cards through the machine. When I got to the office, we found that the machine was out of order. I was headed for Elk City the next day. Since the machine was down, I’d have to just forget the idea.

One of the governor’s aides excused himself for a moment. When he came back, he led me into the governor’s office. Dirk Kempthorne had agreed to sign each one individually while I waited. I was surprised that he took the time to do that for me and for the kids in Elk City.

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.  Governors Len B. Jordan and Chase Clark went for simplicity.

Governors Len B. Jordan and Chase Clark went for simplicity.  Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.

Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.  Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

This final example is the size of a business card. It’s my favorite. I was going to spend the day at the Elk City elementary school teaching the students about poetry. It was something Tom Trusky had cooked up for a National Endowment for the Arts grant. I thought it would be fun to give the kids each a “poetic license” signed by the governor. Much of a governor’s correspondence is actually signed by a machine that does a beautiful job of replicating a signature. I had arranged ahead of time to have his staff run the 50 cards through the machine. When I got to the office, we found that the machine was out of order. I was headed for Elk City the next day. Since the machine was down, I’d have to just forget the idea.

One of the governor’s aides excused himself for a moment. When he came back, he led me into the governor’s office. Dirk Kempthorne had agreed to sign each one individually while I waited. I was surprised that he took the time to do that for me and for the kids in Elk City.

Published on October 07, 2022 04:00

October 6, 2022

All Faces West (Tap to read)

Thanks to Tom Trusky, who was the top sleuth of Idaho movies, I’ve had an interest in them for several years. I recently ran across an oblique mention of one I’d never heard of called All Faces West.

The mention of the movie included a note of regret that it was never shown because it had been filmed as a silent movie just when talkies were coming out. I decided to see what I could find out about it.

First, it was a movie with at least four titles. That’s not especially unusual because a movie often goes into production with a working title that changes before release. This one had two working titles,

The Exodus and The Exodus of the New World. It was meant to tell the struggle of the Mormons as they moved West to Utah. It premiered in Salt Lake City in 1929 under the title All Faces West to good local reviews.

When it was put out for general release as Call of the Rockies in 1931, there had been some changes. The movie had lost the original tie to the story of the Mormons, and sound had been added. Sort of. There was some narrative at the beginning of the film and at the end, otherwise the familiar dialogue cards were inserted to move the story along. Oh, and they dubbed in some additional sounds such as barking dogs and whinnying horses to thrill movie goers.

Those changes were probably the result of someone trying to cobble together a flick that would make some money. The production company had gone bankrupt after spending about $250,000 on the project. Someone bought the rights to the film for $10,000.

Most of the movie was shot in Utah, but several scenes were filmed near Heise Hot Springs and along the Snake River near Twin Falls.

So, not purely an Idaho movie but certainly one that should be included in the history of Idaho filmmaking.

Marie Prevost, one of the starts of All Faces West, later released as Call of the Rockies. She appeared in 121 silent and sound films during her 20-year career. Sadly, Alcoholism took her life at the age of 40 in 1937. Her death was one of the catalysts for the creation of the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.

Marie Prevost, one of the starts of All Faces West, later released as Call of the Rockies. She appeared in 121 silent and sound films during her 20-year career. Sadly, Alcoholism took her life at the age of 40 in 1937. Her death was one of the catalysts for the creation of the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.

The mention of the movie included a note of regret that it was never shown because it had been filmed as a silent movie just when talkies were coming out. I decided to see what I could find out about it.

First, it was a movie with at least four titles. That’s not especially unusual because a movie often goes into production with a working title that changes before release. This one had two working titles,

The Exodus and The Exodus of the New World. It was meant to tell the struggle of the Mormons as they moved West to Utah. It premiered in Salt Lake City in 1929 under the title All Faces West to good local reviews.

When it was put out for general release as Call of the Rockies in 1931, there had been some changes. The movie had lost the original tie to the story of the Mormons, and sound had been added. Sort of. There was some narrative at the beginning of the film and at the end, otherwise the familiar dialogue cards were inserted to move the story along. Oh, and they dubbed in some additional sounds such as barking dogs and whinnying horses to thrill movie goers.

Those changes were probably the result of someone trying to cobble together a flick that would make some money. The production company had gone bankrupt after spending about $250,000 on the project. Someone bought the rights to the film for $10,000.

Most of the movie was shot in Utah, but several scenes were filmed near Heise Hot Springs and along the Snake River near Twin Falls.

So, not purely an Idaho movie but certainly one that should be included in the history of Idaho filmmaking.

Marie Prevost, one of the starts of All Faces West, later released as Call of the Rockies. She appeared in 121 silent and sound films during her 20-year career. Sadly, Alcoholism took her life at the age of 40 in 1937. Her death was one of the catalysts for the creation of the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.

Marie Prevost, one of the starts of All Faces West, later released as Call of the Rockies. She appeared in 121 silent and sound films during her 20-year career. Sadly, Alcoholism took her life at the age of 40 in 1937. Her death was one of the catalysts for the creation of the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.

Published on October 06, 2022 04:00

October 5, 2022

A Year of Crashes (Tap to read)

1966 was going to be a pivotal election year no matter what. The Idaho Legislature had passed the 3-cent sales tax and Governor Robert E. Smylie had signed the bill. State Senator Don Samuelson, Sandpoint, was challenging the governor in the Republican primary based at least in part on Smylie’s support of the sales tax. The Democratic primary pitted a former Idaho state senator, Charles Herndon from Salmon, against Idaho State Senator Cecil Andrus, from Orofino.

Sales tax was a divisive issue, almost as divisive as the Viet Nam War was becoming. But airplanes would change the course of that year’s election as much as issues.

First, a leading contender for the Republican nomination for Congress from Idaho’s First Congressional District crashed his airplane near Osborne. John N. Mattmiller, who had run unsuccessfully for the seat in 1964, was piloting his four-place Piper Comanche over North Idaho’s Silver Valley when the crash happened. An experienced pilot, Mattmiller had survived a crash five years earlier that had broken both legs.

According to witnesses, the Comanche dropped out of the overcast into the narrow valley, apparently looking for a place to land. Mattmiller narrowly missed the KWAL radio tower in Osborne. The plane seemed to be headed for a landing on U.S. 10, about five miles from his destination at the Smelterville airport. Mattmiller pulled up when he saw a tanker truck on the highway, and banked the plane around, perhaps for another landing attempt. That’s when he struck a powerline, bringing the plane down hard. Mattmiller, and a passenger both died instantly.

Mattmiller’s untimely death opened up the primary for a young state senator named Jim McClure. McClure was elected to Congress and served in the House of Representatives until 1973 when he was elected to the U.S. Senate. He served there until his retirement in 1991.

In the primary for governor, Samuelson surprised Smylie, defeating the long-serving governor soundly. Herndon sneaked by Cecil Andrus by about 1,300 votes setting up a general election bout with Samuelson.

Then came the second crash. On September 14, 1966, Herndon was in Pocatello looking for a flight to Coeur d’Alene where he had an afternoon speaking engagement. Nothing commercial was flying because the Pocatello and Idaho Falls airports were socked in with fog.

Herndon made a highway dash for Twin Falls where he chartered an airplane. Two men from Oklahoma City who had business in North Idaho shared the charter with Herndon.

Herndon and the pilot, Bill Bir of Twin Falls, were in the front seats of the Piper Apache. Oddly, when the plane came out of the clouds and plowed into a forested hillside ten miles west of Stanley, the Oklahoma passengers in back were killed instantly. Herndon and the pilot were badly injured. The pilot was airlifted from the crash site to a Sun Valley hospital. He survived. Charles Herndon died before he could be taken from the crash site.

The runner-up in the Democratic primary was named to replace Herndon on the ticket. That was the first time Cecil D. Andrus faced Don Samuelson. Samuelson won the first match, becoming Idaho’s 25th governor. Four years later, Andrus would become the 26th governor of Idaho, defeating Samuelson. He would eventually win four elections to that post and become Secretary of the Interior in President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet.

A 1966 ad for Charles Herndon for governor.

A 1966 ad for Charles Herndon for governor.

Sales tax was a divisive issue, almost as divisive as the Viet Nam War was becoming. But airplanes would change the course of that year’s election as much as issues.

First, a leading contender for the Republican nomination for Congress from Idaho’s First Congressional District crashed his airplane near Osborne. John N. Mattmiller, who had run unsuccessfully for the seat in 1964, was piloting his four-place Piper Comanche over North Idaho’s Silver Valley when the crash happened. An experienced pilot, Mattmiller had survived a crash five years earlier that had broken both legs.

According to witnesses, the Comanche dropped out of the overcast into the narrow valley, apparently looking for a place to land. Mattmiller narrowly missed the KWAL radio tower in Osborne. The plane seemed to be headed for a landing on U.S. 10, about five miles from his destination at the Smelterville airport. Mattmiller pulled up when he saw a tanker truck on the highway, and banked the plane around, perhaps for another landing attempt. That’s when he struck a powerline, bringing the plane down hard. Mattmiller, and a passenger both died instantly.

Mattmiller’s untimely death opened up the primary for a young state senator named Jim McClure. McClure was elected to Congress and served in the House of Representatives until 1973 when he was elected to the U.S. Senate. He served there until his retirement in 1991.

In the primary for governor, Samuelson surprised Smylie, defeating the long-serving governor soundly. Herndon sneaked by Cecil Andrus by about 1,300 votes setting up a general election bout with Samuelson.

Then came the second crash. On September 14, 1966, Herndon was in Pocatello looking for a flight to Coeur d’Alene where he had an afternoon speaking engagement. Nothing commercial was flying because the Pocatello and Idaho Falls airports were socked in with fog.

Herndon made a highway dash for Twin Falls where he chartered an airplane. Two men from Oklahoma City who had business in North Idaho shared the charter with Herndon.

Herndon and the pilot, Bill Bir of Twin Falls, were in the front seats of the Piper Apache. Oddly, when the plane came out of the clouds and plowed into a forested hillside ten miles west of Stanley, the Oklahoma passengers in back were killed instantly. Herndon and the pilot were badly injured. The pilot was airlifted from the crash site to a Sun Valley hospital. He survived. Charles Herndon died before he could be taken from the crash site.

The runner-up in the Democratic primary was named to replace Herndon on the ticket. That was the first time Cecil D. Andrus faced Don Samuelson. Samuelson won the first match, becoming Idaho’s 25th governor. Four years later, Andrus would become the 26th governor of Idaho, defeating Samuelson. He would eventually win four elections to that post and become Secretary of the Interior in President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet.

A 1966 ad for Charles Herndon for governor.

A 1966 ad for Charles Herndon for governor.

Published on October 05, 2022 04:00

October 4, 2022

Coffee Cards (Tap to read)

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

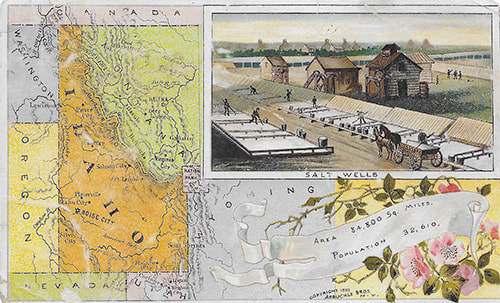

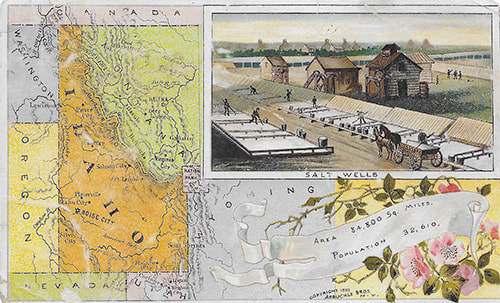

This little card, and others like it, came with one-pound sacks of Arbuckle’s Ariosa Coffee. The company is still in existence. Here’s a history blurb from their website:

“Arbuckles’ Coffee began in the post Civil War Era of the 19th Century. Two brothers, John and Charles Arbuckle, initiated a new concept in the coffee industry; selling roasted coffee in one pound packages. Until that time, coffee was sold green and had to be roasted in a skillet over a fire or in a wood stove. You can imagine the inconsistency of the coffee. One burned bean ruined the whole batch. The Arbuckle Brothers were able to roast a coffee that was of consistently fine quality and the first to be packaged in one pound bags.

“Arbuckles’ Ariosa Blend became so popular in the Old West that most cowboys didn't even know that there was any other. Arbuckles’ Coffee was prominent in such infamous cow towns as Dodge City and Tombstone. To many of the older cowboys, Arbuckles’ Ariosa Blend is still known as the Original Cowboy Coffee.”

The trading cards (collect them all!) featured 50 states and territories. Today, an Idaho card would likely feature potatoes. In the 1860s, the cards featured that amazing Idaho product, salt. If you didn’t know about Idaho’s salt production, check this blog post I wrote about it.

This little card, and others like it, came with one-pound sacks of Arbuckle’s Ariosa Coffee. The company is still in existence. Here’s a history blurb from their website:

“Arbuckles’ Coffee began in the post Civil War Era of the 19th Century. Two brothers, John and Charles Arbuckle, initiated a new concept in the coffee industry; selling roasted coffee in one pound packages. Until that time, coffee was sold green and had to be roasted in a skillet over a fire or in a wood stove. You can imagine the inconsistency of the coffee. One burned bean ruined the whole batch. The Arbuckle Brothers were able to roast a coffee that was of consistently fine quality and the first to be packaged in one pound bags.

“Arbuckles’ Ariosa Blend became so popular in the Old West that most cowboys didn't even know that there was any other. Arbuckles’ Coffee was prominent in such infamous cow towns as Dodge City and Tombstone. To many of the older cowboys, Arbuckles’ Ariosa Blend is still known as the Original Cowboy Coffee.”

The trading cards (collect them all!) featured 50 states and territories. Today, an Idaho card would likely feature potatoes. In the 1860s, the cards featured that amazing Idaho product, salt. If you didn’t know about Idaho’s salt production, check this blog post I wrote about it.

Published on October 04, 2022 04:00

October 3, 2022

First Day of Issue (Tap to read)

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

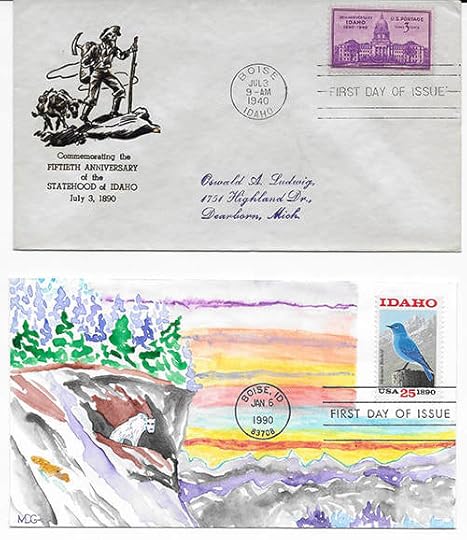

Today we have a couple of samples of First Day of Issue stamps and envelopes. The first one is from 1940, the 50th anniversary of Idaho statehood. The stamp depicts Idaho’s statehouse.

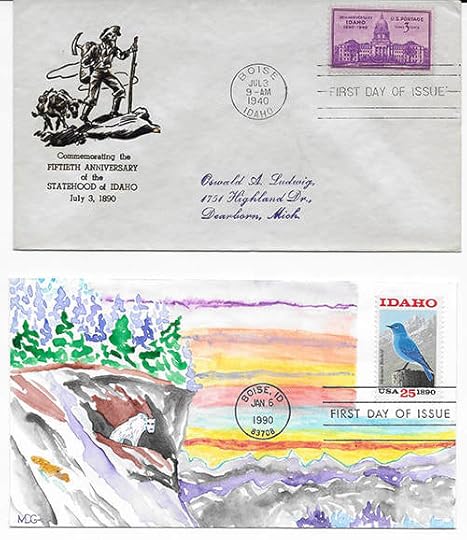

The second, from 50 years later, celebrates the state’s Centennial. Idaho’s state bird, the Mountain Bluebird is featured on the stamp.

This Bluebird cover was made unique by Mark D. Grabowski, an artist who specialized in painting little scenes on First Day of Issue envelopes. FYI, his envelopes sell for anywhere from $15 to $150 today, depending on rarity. I’m not sure what they sold for at the time of their creation.

According to our brainy friends at Wikipedia, “A first day of issue cover or first day cover (FDC) is a postage stamp on a cover, postal card or stamped envelope franked on the first day the issue is authorized for use[1] within the country or territory of the stamp-issuing authority. Sometimes the issue is made from a temporary or permanent foreign or overseas office. Covers that are postmarked at sea or their next port of call will carry a Paquebot postmark.[2] There will usually be a first day of issue postmark, frequently a pictorial cancellation, indicating the city and date where the item was first issued, and "first day of issue" is often used to refer to this postmark. Depending on the policy of the nation issuing the stamp, official first day postmarks may sometimes be applied to covers weeks or months after the date indicated.

Postal authorities may hold a first day ceremony to generate publicity for the new issue, with postal officials revealing the stamp, and with connected persons in attendance, such as descendants of the person being honored by the stamp. The ceremony may also be held in a location that has a special connection with the stamp's subject, such as the birthplace of a social movement, or at a stamp show.”

Today we have a couple of samples of First Day of Issue stamps and envelopes. The first one is from 1940, the 50th anniversary of Idaho statehood. The stamp depicts Idaho’s statehouse.

The second, from 50 years later, celebrates the state’s Centennial. Idaho’s state bird, the Mountain Bluebird is featured on the stamp.

This Bluebird cover was made unique by Mark D. Grabowski, an artist who specialized in painting little scenes on First Day of Issue envelopes. FYI, his envelopes sell for anywhere from $15 to $150 today, depending on rarity. I’m not sure what they sold for at the time of their creation.

According to our brainy friends at Wikipedia, “A first day of issue cover or first day cover (FDC) is a postage stamp on a cover, postal card or stamped envelope franked on the first day the issue is authorized for use[1] within the country or territory of the stamp-issuing authority. Sometimes the issue is made from a temporary or permanent foreign or overseas office. Covers that are postmarked at sea or their next port of call will carry a Paquebot postmark.[2] There will usually be a first day of issue postmark, frequently a pictorial cancellation, indicating the city and date where the item was first issued, and "first day of issue" is often used to refer to this postmark. Depending on the policy of the nation issuing the stamp, official first day postmarks may sometimes be applied to covers weeks or months after the date indicated.

Postal authorities may hold a first day ceremony to generate publicity for the new issue, with postal officials revealing the stamp, and with connected persons in attendance, such as descendants of the person being honored by the stamp. The ceremony may also be held in a location that has a special connection with the stamp's subject, such as the birthplace of a social movement, or at a stamp show.”

Published on October 03, 2022 05:00

October 2, 2022

Bills Island (Tap to read)

Yesterday, I wrote about the name Island Park and how its origins are unclear. Today, we look at an island within Island Park. One thing we know for sure about I.P. Bills Island is that it had nothing to do with the naming of Island Park. Bills Island (for short) only became an island in 1939.

That was the year the Bureau of Reclamation completed the Island Park Dam on the North Fork of the Snake River, more commonly known today as the Henrys Fork.

Much of the land behind the dam was owned by Judge Daniel P. Trude. Trude noticed that what had been a hill on his property would become an island once the reservoir filled. Prior to that inundation, he had a causeway built to the hill.

Judge Trude’s family enjoyed the island as a picnic spot and a place for family outings. When he passed away, his widow and two daughters decided to give the land to the Boy Scouts of America. The Scouts snubbed their generosity on the grounds that administering the island would be too difficult. Disappointed, the family decided to sell the property.

Ivan P. Bills retired in 1945 after 30 years in the automobile business. He started a guide service in Island Park the next year. He was able to scrape together $15,000 to buy 285 acres on the island. The Forest Service managed an additional 100 acres.

Bills and his wife, Yetta, moved into a lodge on the property. They rented rooms and boats and continued with the guiding business. Before long it became apparent that selling lots on the island was a better business than catering to anglers. In 1948 they divided the property into 112 lots, all on the waterfront and began selling them for $1,000 each. The Bills platted another 96 lots on the interior of the island in 1964.

In 1971 I.P. Bills, who was 73, decided it was time to back away from his duties as administrator of the island. Property owners there formed the Bills Island Association, a 501 (c) 4, elected a board of directors, and began making decisions about issues that came up.

Bills passed away in 1984. The island named after him is still managed today by the association. It is a gated property.

Thanks to the association for much of the information used in this post.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

That was the year the Bureau of Reclamation completed the Island Park Dam on the North Fork of the Snake River, more commonly known today as the Henrys Fork.

Much of the land behind the dam was owned by Judge Daniel P. Trude. Trude noticed that what had been a hill on his property would become an island once the reservoir filled. Prior to that inundation, he had a causeway built to the hill.

Judge Trude’s family enjoyed the island as a picnic spot and a place for family outings. When he passed away, his widow and two daughters decided to give the land to the Boy Scouts of America. The Scouts snubbed their generosity on the grounds that administering the island would be too difficult. Disappointed, the family decided to sell the property.

Ivan P. Bills retired in 1945 after 30 years in the automobile business. He started a guide service in Island Park the next year. He was able to scrape together $15,000 to buy 285 acres on the island. The Forest Service managed an additional 100 acres.

Bills and his wife, Yetta, moved into a lodge on the property. They rented rooms and boats and continued with the guiding business. Before long it became apparent that selling lots on the island was a better business than catering to anglers. In 1948 they divided the property into 112 lots, all on the waterfront and began selling them for $1,000 each. The Bills platted another 96 lots on the interior of the island in 1964.

In 1971 I.P. Bills, who was 73, decided it was time to back away from his duties as administrator of the island. Property owners there formed the Bills Island Association, a 501 (c) 4, elected a board of directors, and began making decisions about issues that came up.

Bills passed away in 1984. The island named after him is still managed today by the association. It is a gated property.

Thanks to the association for much of the information used in this post.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

Published on October 02, 2022 04:00

October 1, 2022

A Place Called Island Park (Tap to read)

I’ve been reading

Beyond the One Hundredth Meridian

by Wallace Stenger. It’s about the explorations of John Wesley Powell. At one point in the narrative, Stenger mentioned that Powell named a spot along the Green River, Island Park.

That caught my ear because of the fuzzy origins of the name Island Park in Eastern Idaho. There are a few theories on where the name came from. In the earliest days of Idaho history there were apparently large mats of reeds and foliage floating on Henrys Lake. The name might have come from those floating islands. Another theory is that the “islands” referred to the open meadows in the otherwise heavily forested area. Yet a third theory is just the opposite. That one holds that the “islands” were islands of timber on the sagebrush plain. This is the one that Lalia Boone, author of Idaho Place Names, seems to prefer, since it came from Charlie Pond, one of the early lodge owners in the area.

As I often do, I searched through newspaper archives for early mentions of the name Island Park. There were many, most referring to other places across the country called Island Park. There was an Island Park racecourse in Albany, New York around 1890. There is a Round Island Park also in New York State. There’s a Woodsdale Island Park in Cincinnati. An Island Park Farm in Kentucky was exporting horses to Europe in the late 1800s. And, of course, there is Island Park in St. Anthony, Idaho.

I confess that last one was new to me, and it made me wonder if the name of the region north of St. Anthony had come somehow from that little island off Bridge Street.

After reading the etymology of the word “park” in the Oxford English Dictionary, it occurs to me that some of today’s confusion is about that part of the name. We often think of a park as something developed and managed by a governmental entity. Within the Island Park region, there are two state parks, Henrys Lake and Harriman. So, parks within a park.

The older meaning of the word, and one still used casually today, is something like an outdoor place where the public can recreate. But one of the many definitions and usages caught my eye: “Applied in some parts of the United States, especially Colorado and Wyoming, to a high plateau-like valley among the mountains.”

That definition fits Island Park, which is a plateau flattened by a collapsed caldera. It also sounds a lot like Charlie Pond’s origin story for the name as reported by Lalia Boone.

None of this speculation proves anything, but it helps me better understand a confusing name. It also reminds me of a favorite saying of my late friend and mentor John Freemuth: “God can’t make Wilderness. Only Congress can do that.” Lest you think that blasphemous, John’s point was that from a public lands standpoint “Wilderness” is a designation given by Congress. Similarly, “park” in its official sense is a designation of a governmental entity. That doesn’t stop anyone from referring to a place they love as wilderness or a park.

Tomorrow I’ll tell you about an island in Island Park that came about long after the area got its name.

Harriman State Park, which is a park, is located inside Island Park, which isn't a park.

Harriman State Park, which is a park, is located inside Island Park, which isn't a park.

That caught my ear because of the fuzzy origins of the name Island Park in Eastern Idaho. There are a few theories on where the name came from. In the earliest days of Idaho history there were apparently large mats of reeds and foliage floating on Henrys Lake. The name might have come from those floating islands. Another theory is that the “islands” referred to the open meadows in the otherwise heavily forested area. Yet a third theory is just the opposite. That one holds that the “islands” were islands of timber on the sagebrush plain. This is the one that Lalia Boone, author of Idaho Place Names, seems to prefer, since it came from Charlie Pond, one of the early lodge owners in the area.

As I often do, I searched through newspaper archives for early mentions of the name Island Park. There were many, most referring to other places across the country called Island Park. There was an Island Park racecourse in Albany, New York around 1890. There is a Round Island Park also in New York State. There’s a Woodsdale Island Park in Cincinnati. An Island Park Farm in Kentucky was exporting horses to Europe in the late 1800s. And, of course, there is Island Park in St. Anthony, Idaho.

I confess that last one was new to me, and it made me wonder if the name of the region north of St. Anthony had come somehow from that little island off Bridge Street.

After reading the etymology of the word “park” in the Oxford English Dictionary, it occurs to me that some of today’s confusion is about that part of the name. We often think of a park as something developed and managed by a governmental entity. Within the Island Park region, there are two state parks, Henrys Lake and Harriman. So, parks within a park.

The older meaning of the word, and one still used casually today, is something like an outdoor place where the public can recreate. But one of the many definitions and usages caught my eye: “Applied in some parts of the United States, especially Colorado and Wyoming, to a high plateau-like valley among the mountains.”

That definition fits Island Park, which is a plateau flattened by a collapsed caldera. It also sounds a lot like Charlie Pond’s origin story for the name as reported by Lalia Boone.

None of this speculation proves anything, but it helps me better understand a confusing name. It also reminds me of a favorite saying of my late friend and mentor John Freemuth: “God can’t make Wilderness. Only Congress can do that.” Lest you think that blasphemous, John’s point was that from a public lands standpoint “Wilderness” is a designation given by Congress. Similarly, “park” in its official sense is a designation of a governmental entity. That doesn’t stop anyone from referring to a place they love as wilderness or a park.

Tomorrow I’ll tell you about an island in Island Park that came about long after the area got its name.

Harriman State Park, which is a park, is located inside Island Park, which isn't a park.

Harriman State Park, which is a park, is located inside Island Park, which isn't a park.

Published on October 01, 2022 04:00

September 29, 2022

O No! (Tap to read)

I’ve often written about Idaho’s license plates: here, here, here, here, here, and probably a few posts I didn’t find in a quick search.

So, maybe you think I know everything there is to know about the subject. Bad assumption about me no matter what the subject. But I do know a little. That’s why I was surprised to learn recently about an Idaho license plate fact that was staring me right in the face.

I have an electric car. The City of Boise offers electric vehicles a special parking option. You pay a fee once a year, then forget about feeding meters. I’ve been using it for a couple of years. So, I was surprised to get a parking ticket over near the statehouse.

I checked my parking permit receipt to make sure I hadn’t missed a deadline. Nope, I was good until mid-December. So, I took the ticket to city hall, which was just a couple of blocks away. The helpful clerk was puzzled by the way her system was acting. Yes, I had a permit and, yes, I’d received a ticket. Why hadn’t the meter patrol person noticed that when they typed in my license plate number? I have a personalized—some say “vanity”—plate with the letter and number combination 4IDAHO. At least, I thought I did. It turns out my plate is actually 4IDAH0.

Did you catch the difference there? It’s in that last digit. It is not an O but a zero. It’s not a mistake I made when ordering the plate. It’s not a mistake at all. Idaho uses only zeros when representing an O in a personalized plate. In fact, the only place you’ll actually find an O is in the county designators 1O and 2O. Why? Probably because someone decided it would be less confusing.

It confused the meter reader, though. When they typed in 4IDAHO no EV parking permit came up, so I got a ticket. I would have typed it in the same way. Helpfully, the City of Boise has merged 4IDAHO with 4IDAH0 in their system so that the issue won’t come up again.

I could probably zero in on some lame aphorism to close this post out, but I’ll resist. This isn’t a zero-sum game.

So, maybe you think I know everything there is to know about the subject. Bad assumption about me no matter what the subject. But I do know a little. That’s why I was surprised to learn recently about an Idaho license plate fact that was staring me right in the face.

I have an electric car. The City of Boise offers electric vehicles a special parking option. You pay a fee once a year, then forget about feeding meters. I’ve been using it for a couple of years. So, I was surprised to get a parking ticket over near the statehouse.

I checked my parking permit receipt to make sure I hadn’t missed a deadline. Nope, I was good until mid-December. So, I took the ticket to city hall, which was just a couple of blocks away. The helpful clerk was puzzled by the way her system was acting. Yes, I had a permit and, yes, I’d received a ticket. Why hadn’t the meter patrol person noticed that when they typed in my license plate number? I have a personalized—some say “vanity”—plate with the letter and number combination 4IDAHO. At least, I thought I did. It turns out my plate is actually 4IDAH0.

Did you catch the difference there? It’s in that last digit. It is not an O but a zero. It’s not a mistake I made when ordering the plate. It’s not a mistake at all. Idaho uses only zeros when representing an O in a personalized plate. In fact, the only place you’ll actually find an O is in the county designators 1O and 2O. Why? Probably because someone decided it would be less confusing.

It confused the meter reader, though. When they typed in 4IDAHO no EV parking permit came up, so I got a ticket. I would have typed it in the same way. Helpfully, the City of Boise has merged 4IDAHO with 4IDAH0 in their system so that the issue won’t come up again.

I could probably zero in on some lame aphorism to close this post out, but I’ll resist. This isn’t a zero-sum game.

Published on September 29, 2022 04:00

September 28, 2022

Dead Horse Cave (Tap to read)

Idaho has its fair share of caves. I’ve written about 40 Horse Cave, Aviator Cave, Wilson Butte Cave, and others. Today’s story spotlights an annual gathering in a place called Dead Horse Cave, sometimes Jericho Dead Horse Cave.

A 1966 headline in the Twin Falls Times news called Dead Horse Cave, “Probably (the) World’s Biggest Hall.” If that seems an odd way to describe a cave, blame the Odd Fellows. The Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF) held meetings there annually beginning at least as far back as the 1930s. They “improved” the cave with entrance stairs and concrete benches along the sides of the main room, which is 40 feet below the surface. It’s big enough to hold 300 Odd Fellows, according to various clips about their meetings. They don’t seem to be meeting there anymore, but did so into the late 60s.

The cave is named for its propensity to swallow up wild horses. The opening is more or less in the roof of the lava tube, meaning it was an unexpected hole in the ground when horses galloped across the desert. The bones of equines piled up on the floor of the cave leading to an obvious name.

Dead Horse cave is about 11 miles northwest of Gooding. Ask around or check with the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce. It is well known locally. A visit in the heat of summer is recommended, since the air in the cave hovers around 56 degrees year-round.

The steps leading down to the entrance to Dead Horse Cave.

The steps leading down to the entrance to Dead Horse Cave.

A 1966 headline in the Twin Falls Times news called Dead Horse Cave, “Probably (the) World’s Biggest Hall.” If that seems an odd way to describe a cave, blame the Odd Fellows. The Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF) held meetings there annually beginning at least as far back as the 1930s. They “improved” the cave with entrance stairs and concrete benches along the sides of the main room, which is 40 feet below the surface. It’s big enough to hold 300 Odd Fellows, according to various clips about their meetings. They don’t seem to be meeting there anymore, but did so into the late 60s.

The cave is named for its propensity to swallow up wild horses. The opening is more or less in the roof of the lava tube, meaning it was an unexpected hole in the ground when horses galloped across the desert. The bones of equines piled up on the floor of the cave leading to an obvious name.

Dead Horse cave is about 11 miles northwest of Gooding. Ask around or check with the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce. It is well known locally. A visit in the heat of summer is recommended, since the air in the cave hovers around 56 degrees year-round.

The steps leading down to the entrance to Dead Horse Cave.

The steps leading down to the entrance to Dead Horse Cave.

Published on September 28, 2022 04:00