Rick Just's Blog, page 79

October 28, 2022

The Kelton Road (Tap to read)

Idaho history doesn’t always neatly fit within the state’s borders. Such is the case with Kelton, Utah.

Kelton, named after a local stockman, became a section station on the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. It was located north of the Great Salt Lake and southwest of present-day Snowville, Utah.

In 1863 John Hailey established a stage route between Salt Lake City and Boise. Kelton was one of the stations along the way. Six years later, when Kelton became the best point to connect to the railroad from Boise, the route became known as the Kelton Road.

You can get to the ghost town of Kelton today in less than four hours. In the 1860s it took a little longer. A stage could make between the two towns in 42 hours. If you were hauling freight, it could take 18 days. Here’s a list of the stage stops along the Kelton Road, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s Reference Series.

Black's Creek (15 miles from Boise)

Baylock (13 miles)

Canyon Creek (12 miles)

Rattlesnake (8 miles)

Cold Springs (12 miles)

King Hill (10 miles)

Clover Creek (11 miles)

Malad (11 miles)

Sand Springs (11 miles)

Snake River at Clark's Ferry (10 miles)

Desert (12 miles)

Rock Creek (13 miles)

Mountain Meadows (14 miles)

Oakley Meadows (12 miles)

Goose Creek Summit (11 miles)

City of Rocks (11 miles)

Raft River (12 miles)

Clear Creek (12 miles)

Crystal Springs (10 miles)

Kelton (12 miles)

Kelton, Utah’s unique position as Idaho’s railway station ended in 1883 when the Oregon Shortline came through Southern Idaho. The end was sudden. By 1884 a traveler on the old route noticed that “grass now grows over the defunct overland Kelton stage road where the weary traveler once traveled in clouds of dust. . ."

Kelton survived until 1942 when the Southern Pacific pulled out the rails that had made the town boom.

You can see ruts through the lava and an old bridge abutment on the Kelton Road at Malad Gorge State Park. Go to the park unit north of the freeway.

You can also soak up some Kelton Road history at Stricker Ranch, operated by the Idaho State Historical Society. Rock Creek Station was there.

I know it's difficult to see with all that black rock, but the Kelton Road crossed the Malad River at this point.

I know it's difficult to see with all that black rock, but the Kelton Road crossed the Malad River at this point.

Kelton, named after a local stockman, became a section station on the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. It was located north of the Great Salt Lake and southwest of present-day Snowville, Utah.

In 1863 John Hailey established a stage route between Salt Lake City and Boise. Kelton was one of the stations along the way. Six years later, when Kelton became the best point to connect to the railroad from Boise, the route became known as the Kelton Road.

You can get to the ghost town of Kelton today in less than four hours. In the 1860s it took a little longer. A stage could make between the two towns in 42 hours. If you were hauling freight, it could take 18 days. Here’s a list of the stage stops along the Kelton Road, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s Reference Series.

Black's Creek (15 miles from Boise)

Baylock (13 miles)

Canyon Creek (12 miles)

Rattlesnake (8 miles)

Cold Springs (12 miles)

King Hill (10 miles)

Clover Creek (11 miles)

Malad (11 miles)

Sand Springs (11 miles)

Snake River at Clark's Ferry (10 miles)

Desert (12 miles)

Rock Creek (13 miles)

Mountain Meadows (14 miles)

Oakley Meadows (12 miles)

Goose Creek Summit (11 miles)

City of Rocks (11 miles)

Raft River (12 miles)

Clear Creek (12 miles)

Crystal Springs (10 miles)

Kelton (12 miles)

Kelton, Utah’s unique position as Idaho’s railway station ended in 1883 when the Oregon Shortline came through Southern Idaho. The end was sudden. By 1884 a traveler on the old route noticed that “grass now grows over the defunct overland Kelton stage road where the weary traveler once traveled in clouds of dust. . ."

Kelton survived until 1942 when the Southern Pacific pulled out the rails that had made the town boom.

You can see ruts through the lava and an old bridge abutment on the Kelton Road at Malad Gorge State Park. Go to the park unit north of the freeway.

You can also soak up some Kelton Road history at Stricker Ranch, operated by the Idaho State Historical Society. Rock Creek Station was there.

I know it's difficult to see with all that black rock, but the Kelton Road crossed the Malad River at this point.

I know it's difficult to see with all that black rock, but the Kelton Road crossed the Malad River at this point.

Published on October 28, 2022 04:00

October 27, 2022

The Tallest Mountain (Tap to read)

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

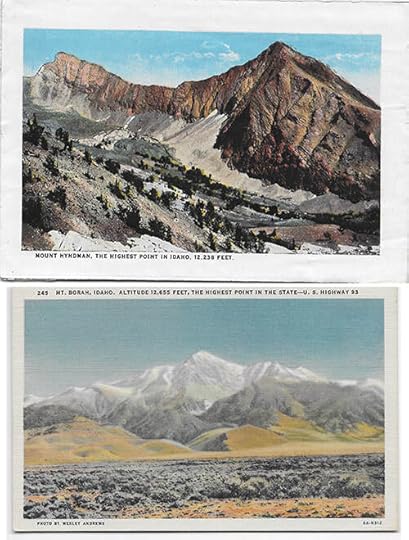

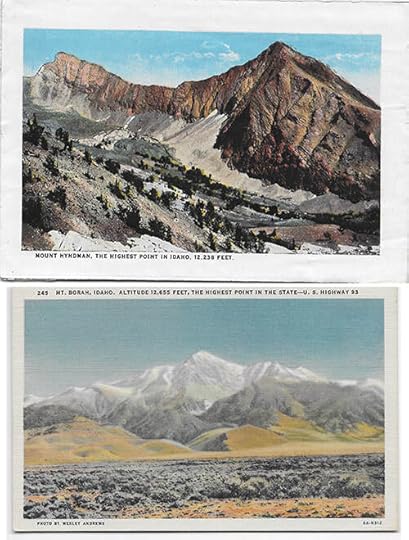

This is a postcard depiction of Idaho’s highest point. I’m not sure when the postcard was produced, but I know it was before 1934. That’s because the card shows Hyndman Peak. That peak, named after the superintendent of the Silver King Mine in Sawtooth City, Major William Hyndman, was thought to be Idaho’s highest mountain at 12,009 feet, until the U.S. Geological Survey found that an unnamed mountain in the Lost River Range was higher. USGS named it Mt. Borah in honor of then US Senator William E. Borah. Naming a mountain for a living person isn’t something that would be done today, even though Borah had already served as a senator from Idaho for 27 years. Mount Borah tops Hyndman Peak by more than 600 feet at 12, 662 feet.

Borah lived long enough after the mountain was named for him to run for a presidential nomination a couple of times before he died in office in 1940.

This is a postcard depiction of Idaho’s highest point. I’m not sure when the postcard was produced, but I know it was before 1934. That’s because the card shows Hyndman Peak. That peak, named after the superintendent of the Silver King Mine in Sawtooth City, Major William Hyndman, was thought to be Idaho’s highest mountain at 12,009 feet, until the U.S. Geological Survey found that an unnamed mountain in the Lost River Range was higher. USGS named it Mt. Borah in honor of then US Senator William E. Borah. Naming a mountain for a living person isn’t something that would be done today, even though Borah had already served as a senator from Idaho for 27 years. Mount Borah tops Hyndman Peak by more than 600 feet at 12, 662 feet.

Borah lived long enough after the mountain was named for him to run for a presidential nomination a couple of times before he died in office in 1940.

Published on October 27, 2022 04:00

October 26, 2022

Greene Wouldn't Leave (Tap to read)

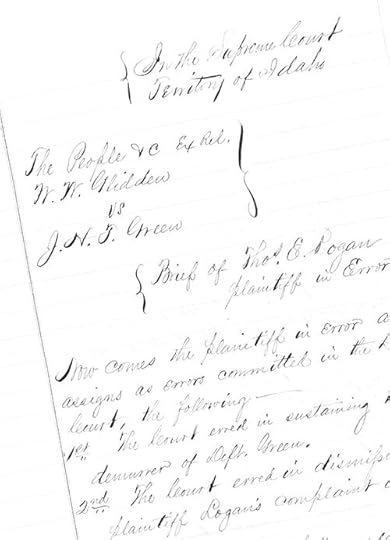

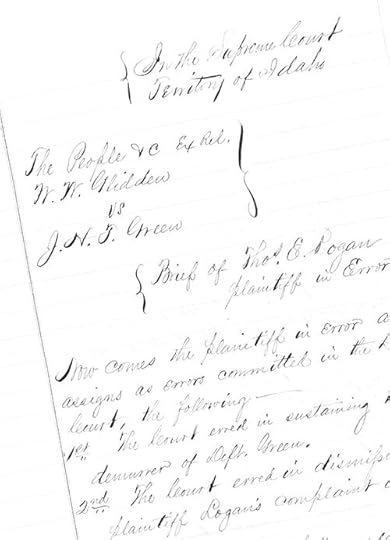

John H.T. Greene purchased the Stage House in Boise in October 1865. He was the fourth owner of the business that year. Perhaps there was a cashflow problem. When he took over the establishment, from which stages departed, patrons could get room and board for $18 a week. A few months later that rose to $21 a week.

The Stage House was under Greene’s management for ten years. His name appeared in the papers often in connection that venture.

But it was Greene’s term as Ada County Treasurer that caused readers to sit up and take notice. He was elected in 1865. In 1867, residents elected another man whose name doesn’t merit a mention in this story.

J.H.T. Greene refused to leave office upon his defeat. He declined to turn over the books and other paraphernalia associated with his position, even when ordered to do so by a judge. His residence became the Ada County Jail. He was jailed for refusing to put up a $2,000 bond set to assure that he would pay whatever fees and emoluments might come into his hands pending the determination of the suit to oust him. Though “jailed,” he still had the run of the city.

Greene began a hobby of filing writs of Habeas Corpus with judges, one after another, until he found one—the fourth one—who would set him free.

The Idaho Statesman commented about Greene’s refusal to leave office, saying, “the old man thinks he was elected for life.”

What was Greene thinking? He argued the election of 1867 was not legal because it was not a “general election” as provided by the legislature, and that no provision for a special election had been made. The court bought that argument, and he remained the treasurer.

But was the reason Greene fought so hard for his job because he believed so much in the rule of law? Maybe. It seems that Greene might also have been reluctant to turn over the books because he considered it risky to do so. Shortly after his success in retaining his office, Greene was indicted for embezzling $32,000 in county funds. His defense was that just because the county was broke didn’t mean he’d embezzled money.

The Idaho Statesman recounted one incident where “someone” had changed a $15 warrant to a $250 warrant, stating, “We find unmistakable signs of tampering with the figures and body of the warrant by some person who has a very limited education in the art of forgery.”

Greene was charged with forgery and embezzlement. Taxpayers in the county began to get grumpy. One letter writer said, “I am at a loss whether to pay my taxes or not. If there is no show of it benefitting the county, I am disposed to resist the collector.”

A district court judge found that “It (was) difficult to get facts, figures and dates positive enough to make them stick.” He dismissed the charges. The Idaho Supreme Court had a go at the embezzlement case and came back with a Nolle Prosequi ruling, meaning they would no longer prosecute it. As the Statesman explained, “the books (have been) kept in so loose a manner that the required facts cannot be elicited from them.”

Books so poorly kept that no one could understand them would seem to be enough to cast a cloud over Treasurer Greene’s service. Yet, his death notice, printed November 13, 1875, called him “one of the old and respected citizens of this place.” The notice made no mention of his service as Ada County Treasurer, and respected as he might have been, the mortuary spelled his name wrong, omitting the final E.

The Stage House was under Greene’s management for ten years. His name appeared in the papers often in connection that venture.

But it was Greene’s term as Ada County Treasurer that caused readers to sit up and take notice. He was elected in 1865. In 1867, residents elected another man whose name doesn’t merit a mention in this story.

J.H.T. Greene refused to leave office upon his defeat. He declined to turn over the books and other paraphernalia associated with his position, even when ordered to do so by a judge. His residence became the Ada County Jail. He was jailed for refusing to put up a $2,000 bond set to assure that he would pay whatever fees and emoluments might come into his hands pending the determination of the suit to oust him. Though “jailed,” he still had the run of the city.

Greene began a hobby of filing writs of Habeas Corpus with judges, one after another, until he found one—the fourth one—who would set him free.

The Idaho Statesman commented about Greene’s refusal to leave office, saying, “the old man thinks he was elected for life.”

What was Greene thinking? He argued the election of 1867 was not legal because it was not a “general election” as provided by the legislature, and that no provision for a special election had been made. The court bought that argument, and he remained the treasurer.

But was the reason Greene fought so hard for his job because he believed so much in the rule of law? Maybe. It seems that Greene might also have been reluctant to turn over the books because he considered it risky to do so. Shortly after his success in retaining his office, Greene was indicted for embezzling $32,000 in county funds. His defense was that just because the county was broke didn’t mean he’d embezzled money.

The Idaho Statesman recounted one incident where “someone” had changed a $15 warrant to a $250 warrant, stating, “We find unmistakable signs of tampering with the figures and body of the warrant by some person who has a very limited education in the art of forgery.”

Greene was charged with forgery and embezzlement. Taxpayers in the county began to get grumpy. One letter writer said, “I am at a loss whether to pay my taxes or not. If there is no show of it benefitting the county, I am disposed to resist the collector.”

A district court judge found that “It (was) difficult to get facts, figures and dates positive enough to make them stick.” He dismissed the charges. The Idaho Supreme Court had a go at the embezzlement case and came back with a Nolle Prosequi ruling, meaning they would no longer prosecute it. As the Statesman explained, “the books (have been) kept in so loose a manner that the required facts cannot be elicited from them.”

Books so poorly kept that no one could understand them would seem to be enough to cast a cloud over Treasurer Greene’s service. Yet, his death notice, printed November 13, 1875, called him “one of the old and respected citizens of this place.” The notice made no mention of his service as Ada County Treasurer, and respected as he might have been, the mortuary spelled his name wrong, omitting the final E.

Published on October 26, 2022 04:00

October 25, 2022

Get Yourself a College Girl (Tap to read)

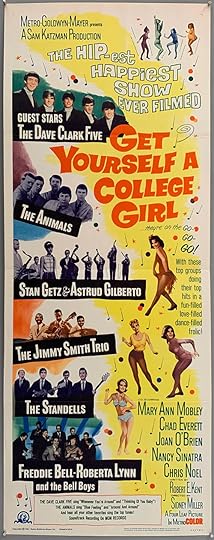

Would it surprise you to learn that “the hip-est, happiest show ever filmed” was shot in Idaho? Yes? Then prepare to be flabbergasted. Get Yourself a College Girl was the movie thus billed. It was so hip that it starred former Miss America Mary Ann Mobley, Chad Everett, and Nancy Sinatra, the latter a couple of years before her hit song about boots.

Not to worry, though. Nancy didn’t sing in the movie, but sooo many others did, including the Standells, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, The Dave Clark Five, and The Animals. How hip is that? The movie was largely an excuse to have those groups and others perform in front of a camera.

The film was one of many shot in Sun Valley, this one in 1963. It was received. The LA Times called it “inoffensively silly.” Still, it’s with enduring a 30 second commercial to watch the trailer on YouTube.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

Not to worry, though. Nancy didn’t sing in the movie, but sooo many others did, including the Standells, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, The Dave Clark Five, and The Animals. How hip is that? The movie was largely an excuse to have those groups and others perform in front of a camera.

The film was one of many shot in Sun Valley, this one in 1963. It was received. The LA Times called it “inoffensively silly.” Still, it’s with enduring a 30 second commercial to watch the trailer on YouTube.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

Published on October 25, 2022 04:00

October 24, 2022

Idaho's Gas Tax (Tap to read)

Idaho’s state gasoline tax hasn’t really raised in a hundred years. I have your attention with that statement, don’t I? It’s obviously wrong. Idaho’s only had a gasoline tax for 98 years. Nevertheless, bear with me.

In 1923, Idaho instituted its first tax on gasoline. The Legislature that year tacked two cents onto each gallon of gas for road building and repair. Gas cost about 22 cents a gallon. Automobile owners were generally supportive of the effort.

Today, Idaho’s state gasoline tax is 33 cents per gallon, so it has obviously gone up. But factor in inflation. That two cents from 1923 would have 31 cents of buying power today. So, it’s about the same.

The two-cent tax became a three-cent tax in 1925, a four-cent tax in 1927, and a nickel in 1929. The state was a in a road-building frenzy. The tax remained the same until 1945 when it went to 6 cents. It hung around in that neighborhood for 23 years, going to seven cents in 1968. Four years later the tax went to 8.5 cents a gallon. In 1976 it hit 9.5 cents. In 1981, the Legislature moved it to 11.5 cents. That was so much fun that they raised it an additional penny the next year. Giddy with that accomplishment, lawmakers moved it two cents in 1983 to 14.5 cents per gallon. It stayed there until 1988 when it jumped to 18 cents. In 1991 the tax moved 21 cents.

Are you seeing a pattern here?

The first time Idahoans started paying a quarter in tax for every gallon of gas was in 1996. That was more than a gallon of gas cost back in 1923 when the whole thing started. In 2015 the state gasoline tax went to 33 cents per gallon (effective in 2017), which is where it is today.

It was also in 2015 that the Legislature took notice of scoundrels like me who don’t pay any gasoline tax because we don’t buy any gasoline. They added $140 to annual registration fees for electric vehicles.

Are roads better today than they were in 1923 when all this began? Considerably. They’re also a lot more expensive to build and maintain, so look for future gas tax increases or some other method to help pay for them from some future Legislature.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

In 1923, Idaho instituted its first tax on gasoline. The Legislature that year tacked two cents onto each gallon of gas for road building and repair. Gas cost about 22 cents a gallon. Automobile owners were generally supportive of the effort.

Today, Idaho’s state gasoline tax is 33 cents per gallon, so it has obviously gone up. But factor in inflation. That two cents from 1923 would have 31 cents of buying power today. So, it’s about the same.

The two-cent tax became a three-cent tax in 1925, a four-cent tax in 1927, and a nickel in 1929. The state was a in a road-building frenzy. The tax remained the same until 1945 when it went to 6 cents. It hung around in that neighborhood for 23 years, going to seven cents in 1968. Four years later the tax went to 8.5 cents a gallon. In 1976 it hit 9.5 cents. In 1981, the Legislature moved it to 11.5 cents. That was so much fun that they raised it an additional penny the next year. Giddy with that accomplishment, lawmakers moved it two cents in 1983 to 14.5 cents per gallon. It stayed there until 1988 when it jumped to 18 cents. In 1991 the tax moved 21 cents.

Are you seeing a pattern here?

The first time Idahoans started paying a quarter in tax for every gallon of gas was in 1996. That was more than a gallon of gas cost back in 1923 when the whole thing started. In 2015 the state gasoline tax went to 33 cents per gallon (effective in 2017), which is where it is today.

It was also in 2015 that the Legislature took notice of scoundrels like me who don’t pay any gasoline tax because we don’t buy any gasoline. They added $140 to annual registration fees for electric vehicles.

Are roads better today than they were in 1923 when all this began? Considerably. They’re also a lot more expensive to build and maintain, so look for future gas tax increases or some other method to help pay for them from some future Legislature.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Published on October 24, 2022 04:00

October 23, 2022

The Old Blackfoot Sugar Factory (Tap to read)

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

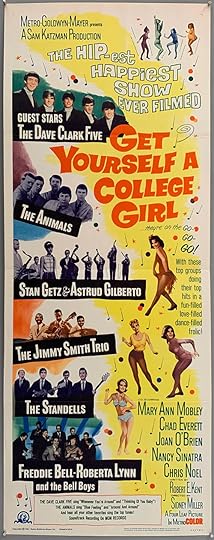

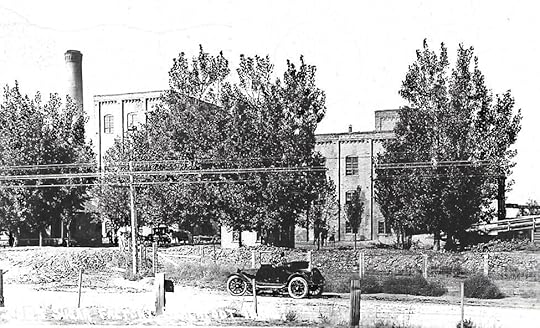

I’ve written about the Blackfoot Sugar Factory before, but didn’t remember that I had this old postcard. This picture was taken sometime before 1937, going by the postmark. You’re looking more or less west from what is now US 91. At this time the road was dirt. The highway was a major route running from Long Beach to Alberta between 1947 and 1965. Today, although several segments of it still exist, including the one through Blackfoot, it has largely been replaced by I-15.

With the powerlines and trees in the way this doesn’t show much detail of the building, but there is a lot going on. The roadster parked in front looks like a Model T, perhaps dating the photo to sometime in the 20s. There’s a coupe of some kind parked under the trees with a couple of horses tied up nearby. To the left of the photo “under” the smokestack, is one of the staff houses. A string of five of those houses are still there being used as residences. The sugar factory itself is long gone.

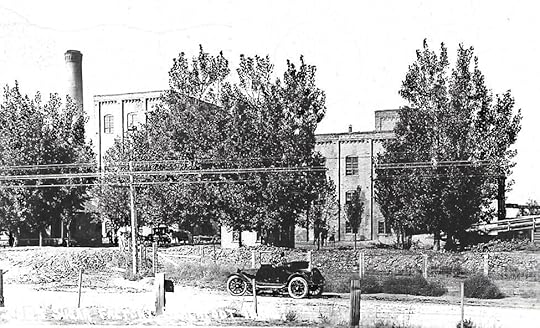

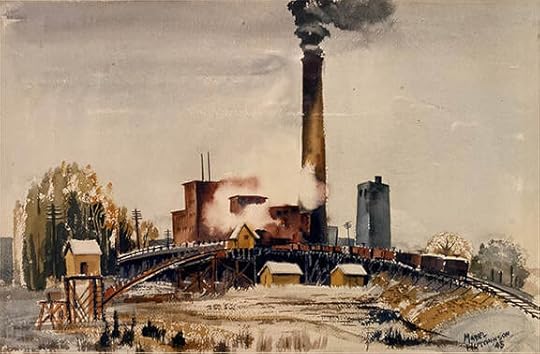

One of the more interesting items in the picture is the ramp you can see leading up to the right and around the back of the building. The 1943 watercolor below this picture shows the ramp from a different angle, looking more toward the south. Wagons and train cars moved up those ramps to a beet dumping site behind the factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.  This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

I’ve written about the Blackfoot Sugar Factory before, but didn’t remember that I had this old postcard. This picture was taken sometime before 1937, going by the postmark. You’re looking more or less west from what is now US 91. At this time the road was dirt. The highway was a major route running from Long Beach to Alberta between 1947 and 1965. Today, although several segments of it still exist, including the one through Blackfoot, it has largely been replaced by I-15.

With the powerlines and trees in the way this doesn’t show much detail of the building, but there is a lot going on. The roadster parked in front looks like a Model T, perhaps dating the photo to sometime in the 20s. There’s a coupe of some kind parked under the trees with a couple of horses tied up nearby. To the left of the photo “under” the smokestack, is one of the staff houses. A string of five of those houses are still there being used as residences. The sugar factory itself is long gone.

One of the more interesting items in the picture is the ramp you can see leading up to the right and around the back of the building. The 1943 watercolor below this picture shows the ramp from a different angle, looking more toward the south. Wagons and train cars moved up those ramps to a beet dumping site behind the factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.  This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

Published on October 23, 2022 04:00

October 22, 2022

Idaho Jazz (Tap to read)

When you hear the word Idaho, the first thing you think of is jazz, right? Right?

Okay, maybe not. But there is a pretty great song called “Idaho” that is a fairly well-known jazz piece. It was written by Jesse Stone who, as far as I know, had no connection to Idaho.

“Idaho” was originally recorded by Alvino Rey and his orchestra in 1941. The next year, Benny Goodman had a version that hit number 4 on the pop charts. Here’s a link to that one. You’ll probably have to endure a few seconds of commercial before you get to it. Oh, and don’t expect the singing to start right away. Guy Lombardo sold 4 million copies of his version.

The song is a snappy little number. Even so, I was surprised to learn that Stone was also the writer behind the decidedly rock, “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.”

Okay, maybe not. But there is a pretty great song called “Idaho” that is a fairly well-known jazz piece. It was written by Jesse Stone who, as far as I know, had no connection to Idaho.

“Idaho” was originally recorded by Alvino Rey and his orchestra in 1941. The next year, Benny Goodman had a version that hit number 4 on the pop charts. Here’s a link to that one. You’ll probably have to endure a few seconds of commercial before you get to it. Oh, and don’t expect the singing to start right away. Guy Lombardo sold 4 million copies of his version.

The song is a snappy little number. Even so, I was surprised to learn that Stone was also the writer behind the decidedly rock, “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.”

Published on October 22, 2022 04:00

October 21, 2022

Dad Clay Foils a Kidnapping (Tap to read)

What are the odds of being a participant in two kidnappings? J.C. “Dad” Clay of Idaho Falls could claim that. He had different roles in each adventure, first as the driver of a carload of law enforcement officers that captured a kidnapper, and second as the kidnappee and captor of the kidnappers.

I wrote about Dad Clay yesterday, so I won’t attempt to describe him in detail. Suffice to say, for this story, that he owned the first automobile garage in the state. He started his Idaho Falls garage in 1909. By 1914, he was selling cars there and had published Idaho’s first road log to help travelers get around the state. His first brush with kidnapping came in 1915.

That’s when the kidnapper of E.A. Empey was apprehended. The Idaho Statesman, on July 28, 1915 described it like this: “A party was at once organized at the Sheriff’s office, consisting of deputies and reporters, who in a big car driven by J.C. Clay, an old resident of the community, thoroughly familiar with every road and trail in the entire country and a fast driver, were soon on the way to meet the bandit and his captors.” Clay played a small role in that incident, which you can read all about through the link above. His role was decidedly larger during the next kidnapping the following year.

According to an oral history told to his family, the kidnapping came about because he ran a taxi service next to his garage. A couple of tough looking young men came by looking for a ride into the country. An employee was set to take them, but Clay didn’t think it was safe for the boy to head out with those customers, so he decided to take them himself.

One of the men hopped into the seat beside the driver and the other got in back. They had driven about 20 miles when the man in the back seat slipped a piece of pipe out from under his coat where he had been hiding it and wacked Dad Clay over the head, knocking him out. The pair frisked Clay, finding a derringer in his side pocket and his wallet. They tied his hands and feet together and threw the unconscious man in the back.

After a few minutes and miles of travel, Clay came to. He could hear the toughs in front of the car laughing about hijacking his taxi. He came to understand that it was their plan to dump him in a ditch somewhere after killing him. Since this didn’t mesh well with his own plans for the future, Dad Clay worked his hands and feet free from the ropes while his kidnappers weren’t paying any attention. In the process, he discovered that the pipe he’d been beaned with was down there on the floor with him.

Clay rose up and returned the favor, clubbing each man hard on the head with the pipe. He tied both of them up, doing a better job of it than they had, and piled them in the back seat. He had found his derringer and couple of pistols the men had been carrying. His passengers secured, he turned around and headed back to town.

Dad Clay delivered the carjackers to the sheriff’s office, where he found out they’d escaped from a nearby correctional facility.

There is a newspaper account of the story which differs a bit. In that version one of the kidnappers escaped for a short time before being apprehended by authorities, but the essential account of Clay’s bonk on the head and turning the tables on the men to bring them to justice seems essentially true.

A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

I wrote about Dad Clay yesterday, so I won’t attempt to describe him in detail. Suffice to say, for this story, that he owned the first automobile garage in the state. He started his Idaho Falls garage in 1909. By 1914, he was selling cars there and had published Idaho’s first road log to help travelers get around the state. His first brush with kidnapping came in 1915.

That’s when the kidnapper of E.A. Empey was apprehended. The Idaho Statesman, on July 28, 1915 described it like this: “A party was at once organized at the Sheriff’s office, consisting of deputies and reporters, who in a big car driven by J.C. Clay, an old resident of the community, thoroughly familiar with every road and trail in the entire country and a fast driver, were soon on the way to meet the bandit and his captors.” Clay played a small role in that incident, which you can read all about through the link above. His role was decidedly larger during the next kidnapping the following year.

According to an oral history told to his family, the kidnapping came about because he ran a taxi service next to his garage. A couple of tough looking young men came by looking for a ride into the country. An employee was set to take them, but Clay didn’t think it was safe for the boy to head out with those customers, so he decided to take them himself.

One of the men hopped into the seat beside the driver and the other got in back. They had driven about 20 miles when the man in the back seat slipped a piece of pipe out from under his coat where he had been hiding it and wacked Dad Clay over the head, knocking him out. The pair frisked Clay, finding a derringer in his side pocket and his wallet. They tied his hands and feet together and threw the unconscious man in the back.

After a few minutes and miles of travel, Clay came to. He could hear the toughs in front of the car laughing about hijacking his taxi. He came to understand that it was their plan to dump him in a ditch somewhere after killing him. Since this didn’t mesh well with his own plans for the future, Dad Clay worked his hands and feet free from the ropes while his kidnappers weren’t paying any attention. In the process, he discovered that the pipe he’d been beaned with was down there on the floor with him.

Clay rose up and returned the favor, clubbing each man hard on the head with the pipe. He tied both of them up, doing a better job of it than they had, and piled them in the back seat. He had found his derringer and couple of pistols the men had been carrying. His passengers secured, he turned around and headed back to town.

Dad Clay delivered the carjackers to the sheriff’s office, where he found out they’d escaped from a nearby correctional facility.

There is a newspaper account of the story which differs a bit. In that version one of the kidnappers escaped for a short time before being apprehended by authorities, but the essential account of Clay’s bonk on the head and turning the tables on the men to bring them to justice seems essentially true.

A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

Published on October 21, 2022 04:00

October 20, 2022

Dad Clay (Tap to read)

John Colby Clay was born in Minnesota in 1854. He came West when he was 15. He kicked around the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Oregon for a number of years punching cattle, ranching, and driving a freight wagon. He ended up settling in Idaho in 1892.

In 1908 (or 1909, or 1910… accounts differ) J.C. Clay had an epiphany. He was fascinated with automobiles and decided to bet his future on them. Already in his 50s, it wouldn’t seem like a time to start a new venture, but he did. No one knows exactly when people started calling him “Dad” Clay, but he solidified that moniker by building Dad Clay’s Garage. It was the first automobile service center in the state. It grew to include car dealerships for a time and a taxi company. Proving that he was a man way ahead of his time, he built an underground parking area beneath the garage.

Dad Clay was elected the “good roads” chairman of the Idaho State Automobile Association. He took that job seriously. He began marking roads, much as Charlie Sampson did in the Boise area. Sampson started out painting advertising signs about his music business. Clay erected hundreds of black and orange signs all over Southeastern Idaho giving the mileage to his Idaho Falls garage. In 1914, Dad Clay published the first guide to Idaho’s 5,500 miles of roads. It was a big hit with auto enthusiasts, though at least one resident of Pocatello accused him of discriminating against the Gate City by routing travelers around it.

Running Idaho’s first garage wasn’t enough to keep Dad Clay busy, though. He was involved in real estate development, a coal mine, Teton Light and Power, a security firm, and managed the Idaho Falls baseball team, the Sunnylanders. Clay was also a well-known golfer locally. He once famously bet his false teeth on the outcome of a match.

Dad Clay’s love for automobiles got him in trouble at least a couple of times. He was carjacked once, turning the tables on the bad guys. Here’s a link to that story. He was well known for driving full speed wherever he went. That was to his detriment in April of 1914 when he caused a three-car collision on the outskirts of Firth. A Studebaker was dawdling along in front of Dad Clay, who was driving his Hupmobile. A Ford was coming the other direction, but Clay was sure he could make it, so he swung around the Studebaker. What caused the wreck wasn’t exactly clear, but Clay hit the Studebaker, then the Ford, throwing the eight passengers in the three cars all over the road. Clay received a broken arm and everyone else had cuts and bruises. A judge determined that the accident was Dad Clay’s fault. The occupants of the other cars vowed to sue him. The results of that lawsuit, if one did come about, are unknown.

At age 87, Clay sold his garage to a nephew. He passed away the next year on a trip to California at age 88.

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

In 1908 (or 1909, or 1910… accounts differ) J.C. Clay had an epiphany. He was fascinated with automobiles and decided to bet his future on them. Already in his 50s, it wouldn’t seem like a time to start a new venture, but he did. No one knows exactly when people started calling him “Dad” Clay, but he solidified that moniker by building Dad Clay’s Garage. It was the first automobile service center in the state. It grew to include car dealerships for a time and a taxi company. Proving that he was a man way ahead of his time, he built an underground parking area beneath the garage.

Dad Clay was elected the “good roads” chairman of the Idaho State Automobile Association. He took that job seriously. He began marking roads, much as Charlie Sampson did in the Boise area. Sampson started out painting advertising signs about his music business. Clay erected hundreds of black and orange signs all over Southeastern Idaho giving the mileage to his Idaho Falls garage. In 1914, Dad Clay published the first guide to Idaho’s 5,500 miles of roads. It was a big hit with auto enthusiasts, though at least one resident of Pocatello accused him of discriminating against the Gate City by routing travelers around it.

Running Idaho’s first garage wasn’t enough to keep Dad Clay busy, though. He was involved in real estate development, a coal mine, Teton Light and Power, a security firm, and managed the Idaho Falls baseball team, the Sunnylanders. Clay was also a well-known golfer locally. He once famously bet his false teeth on the outcome of a match.

Dad Clay’s love for automobiles got him in trouble at least a couple of times. He was carjacked once, turning the tables on the bad guys. Here’s a link to that story. He was well known for driving full speed wherever he went. That was to his detriment in April of 1914 when he caused a three-car collision on the outskirts of Firth. A Studebaker was dawdling along in front of Dad Clay, who was driving his Hupmobile. A Ford was coming the other direction, but Clay was sure he could make it, so he swung around the Studebaker. What caused the wreck wasn’t exactly clear, but Clay hit the Studebaker, then the Ford, throwing the eight passengers in the three cars all over the road. Clay received a broken arm and everyone else had cuts and bruises. A judge determined that the accident was Dad Clay’s fault. The occupants of the other cars vowed to sue him. The results of that lawsuit, if one did come about, are unknown.

At age 87, Clay sold his garage to a nephew. He passed away the next year on a trip to California at age 88.

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

Published on October 20, 2022 04:00

October 19, 2022

Apostrophes on the Map (Tap to read)

Idaho became a state in 1890. Idahoans disagree on countless things, but there is probably near universal agreement about the name of the state. It’s important that we agree on the names of things. Imagine how confusing it would be if half the citizens of Arco called it by its original name, Root Hog. With apologies to The Lovin’ Spoonful, someone has to finally decide.

The standardization of names was why the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) was created, coincidentally the same year as the state of Idaho. Its charge is to “maintain uniform geographic names usage throughout the Federal Government.” The Board makes sure things are spelled consistently on maps and that two mountains in the same range don’t have the same name.

Driving English majors crazy is also, seemingly, part of the charge of the USBGN. This comes about because of the institution’s phobia about apostrophes. Since its inception, the USBGN has abhorred apostrophes, particularly discouraging the use of possessive apostrophes. That’s why Glenns Ferry is not Glenn’s Ferry and the Henrys Fork is not the Henry’s Fork.

There is nothing in the Board’s archives indicating why they discouraged the use of apostrophes. They do try to justify it in… words. Here you go: “The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists.”

You’re allowed to read that again, if you like.

The takeaway is that the USBGN is adamant that possessive apostrophes are not used in the many thousands of names scattered on United States maps. But, as with the old rule of grammar, “I after E, except after C,” there are a few exceptions. Five, to be exact.

Martha’s Vineyard and its otherwise offensive apostrophe was approved in 1933 after an extensive local campaign. Ike’s Point in New Jersey was approved in 1944 because “it would be unrecognizable otherwise.” In 1963, John E’s Pond got the nod of approval because it would be confused with John S Pond. Note the lack of a period in John S Pond. The USBGN doesn’t like periods, either. Carlos Elmer’s Joshua View was approved in 1995 at the request of the Arizona State Board on Geographic and Historic Names, because “otherwise three apparently given names in succession would dilute the meaning.” In this case Joshua refers to a stand of trees. Finally, Clark’s Mountain in Oregon got to keep its apostrophe in 2002 to “correspond with the personal references of Lewis and Clark.”

Alert readers will have already noted that there is an apostrophe used often in Idaho places names. That one is in the middle of Coeur d’Alene when it refers to the city, the lake, the valley, the tribal reservation, the mountain, the mountain range, and the river. It’s not a possessive apostrophe, so USBGN lets it live.

Postal officials also put the kibosh on certain names. For instance, there is only one city named Eagle in Idaho, though not for a lack of trying. The citizens of a little town south of Sandpoint wanted to call their home Eagle in 1900. To avoid confusion, the postal bureaucracy said no. The citizens in a spate of creativity just changed the E to an S on the post office application form and Sagle was born.

Rick Just was an English major and recently served as the chair of the Idaho Geographic Names Advisory Council.

The standardization of names was why the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) was created, coincidentally the same year as the state of Idaho. Its charge is to “maintain uniform geographic names usage throughout the Federal Government.” The Board makes sure things are spelled consistently on maps and that two mountains in the same range don’t have the same name.

Driving English majors crazy is also, seemingly, part of the charge of the USBGN. This comes about because of the institution’s phobia about apostrophes. Since its inception, the USBGN has abhorred apostrophes, particularly discouraging the use of possessive apostrophes. That’s why Glenns Ferry is not Glenn’s Ferry and the Henrys Fork is not the Henry’s Fork.

There is nothing in the Board’s archives indicating why they discouraged the use of apostrophes. They do try to justify it in… words. Here you go: “The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists.”

You’re allowed to read that again, if you like.

The takeaway is that the USBGN is adamant that possessive apostrophes are not used in the many thousands of names scattered on United States maps. But, as with the old rule of grammar, “I after E, except after C,” there are a few exceptions. Five, to be exact.

Martha’s Vineyard and its otherwise offensive apostrophe was approved in 1933 after an extensive local campaign. Ike’s Point in New Jersey was approved in 1944 because “it would be unrecognizable otherwise.” In 1963, John E’s Pond got the nod of approval because it would be confused with John S Pond. Note the lack of a period in John S Pond. The USBGN doesn’t like periods, either. Carlos Elmer’s Joshua View was approved in 1995 at the request of the Arizona State Board on Geographic and Historic Names, because “otherwise three apparently given names in succession would dilute the meaning.” In this case Joshua refers to a stand of trees. Finally, Clark’s Mountain in Oregon got to keep its apostrophe in 2002 to “correspond with the personal references of Lewis and Clark.”

Alert readers will have already noted that there is an apostrophe used often in Idaho places names. That one is in the middle of Coeur d’Alene when it refers to the city, the lake, the valley, the tribal reservation, the mountain, the mountain range, and the river. It’s not a possessive apostrophe, so USBGN lets it live.

Postal officials also put the kibosh on certain names. For instance, there is only one city named Eagle in Idaho, though not for a lack of trying. The citizens of a little town south of Sandpoint wanted to call their home Eagle in 1900. To avoid confusion, the postal bureaucracy said no. The citizens in a spate of creativity just changed the E to an S on the post office application form and Sagle was born.

Rick Just was an English major and recently served as the chair of the Idaho Geographic Names Advisory Council.

Published on October 19, 2022 04:00