Rick Just's Blog, page 83

September 17, 2022

THE Basque Sheepherder (Tap to read)

Jose “Joe” Bengoechea was a Basque sheepherder. Maybe it should be said that he was the Basque sheepherder. He came to the US in 1881 at age 20. He started herding sheep in Nevada, saving his money, and began buying sheep. His herds grew and he helped others from the Basque Country to immigrate.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.  The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.  The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

Published on September 17, 2022 04:00

September 16, 2022

Idaho's First Flight (Tap to read)

Idaho has a rich aviation history with solid connections to “Pappy” Boyington, Edward Pangborn, and Hawthorne Gray, to name a few daring pilots. The first contract air mail service in the United States was based in Boise with Varney Airlines. United Airlines claims Boise as its historical home, tracing its roots back to Varney.

But when was that first Idaho flight, the inception as it were of Idaho aviation history?

The Idaho Statesman declared, in an article on April 20, 1911, that Walter Brookins had launched into the air on “the first aeroplane flight ever made in the Gem state” the day before. This, in spite of the fact that the same paper had reported on October 16, 1910, that several flights had taken place above the fairgrounds in Lewiston, the last one ending in disaster.

Lewiston, still smarting today more than 150 years after losing the territorial capital, could be forgiven for being a little perturbed at this oversight.

James J. Ward of Chicago made the first Idaho flight on October 13, 1910. In Lewiston. His engine sputtered, causing him to land a little rougher than he’d hoped and destroying the front wheel of the Curtiss biplane. There were plenty of bicycle wheels in Lewiston, so that was easily replaced. He made several successful flights for the cheering crowd in the grandstand at the Lewiston-Clarkston fairgrounds.

His luck ran out, some would say, on October 14. His engine conked out when he was some 200 feet in the air. That was unlucky. But, luckily, Ward was able to jump free of the plane just as it crashed sustaining only minor injuries. The Idaho Statesman printed a dispatch from Lewiston that read, “The Curtiss biplane with which J.J. Ward of Chicago has been making daily flights at the fair, tonight lies a heap of junk on the banks of the Snake River, and that Ward himself is not in the morgue or at the hospital, is almost a miracle.”

Lewiston can also claim the first attempted flight in Idaho, though it was going to be just a glide. That came about on July 30, 1904, less than a year after the first successful flight of the Wright brothers. Captain Stewart V. Winslow, who during his working hours operated a dredge in the Snake River, tried to get into the air by pedaling a bicycle with wings over a cliff. He planned to glide across the river to the Washington side in triumph. He may have considered it bad luck when his front bicycle wheel collapsed before he could ride the contraption off the cliff. Luckily, he never did make a second try.

But what about that 1911 flight in Boise? It didn’t qualify as the first in the state, but it was the first in Boise, and it was accomplished by an aviation pioneer.

Walter Brookins, the first pilot trained by the Wright brothers, took to the air a few minutes after 5 pm on April 19, 1911 from the center field of the racetrack at the fairgrounds in Boise. Note that the fairgrounds were not located where they are today. They were roughly on the corner of Orchard and Fairview, thus the name of the latter street.

Promoters of the spectacle had cancelled the flight, allegedly because the weather had turned too cold for spectators. The many spectators who had shown up began to grumble and speculate that brisk winds were the real reason for the cancellation and casting aspersions on the pilot. When Brookins heard this he immediately rolled out his biplane and made preparations to meet the winds, which were described as gale force, head on.

One spectator was particularly interested in how Brookins would take to the Boise air. W.O. Kay, of Ogden, Utah, had followed the aviator to Boise, disappointed because he had not been able to take a ride in the Wright Biplane when Brookins had flown in Utah. Kay, who weighed 164 pounds, would have been too great a load for the plane to get into the air over Utah’s capital city. The air was too thin to keep both men aloft at Salt Lake’s elevation of 4,220 feet. Kay and Brookins both thought Boise’s 2,730-foot elevation would allow a passenger.

Without a hint of drama Brookins rolled along in the rough pasture for about 200 feet and rose steadily into the air. He would fly around the racetrack five times, a distance of about three miles, before an easy landing. He could not resist putting on a show for the crowd.

The Idaho Statesman described what happened after the pilot seemed to take an unplanned dip, then recover. “Shortly after thrilling the crowd with this feat he increased his speed as though to descend right into the mob. He shot down at a terrific rate, the terror-stricken people scattering right and left.”

He rose at the last moment and made another circuit of the track before landing. The flight had lasted about 12 minutes, securing Brookins place at the head of the line in Boise’s aviation history.

Brookins performed further feats in the days to come, took Kay on his promised airplane ride, and raced an automobile around the track. He was a sensation. His flights moved Idaho Lieutenant Governor Sweetser to present Walter Brookins with a commission as a colonel in the Idaho National Guard, making Idaho the first state to so honor Brookins for his contribution to aeronautics.

Brookins went on to establish numerous aviation records. Chancy as flying was in those early days, he was never seriously injured (a few broken ribs) while flying. He died in 1953 and is buried at the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation in Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles.

Walter Brookins, the pilot of Boise’s first flight. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Walter Brookins, the pilot of Boise’s first flight. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

But when was that first Idaho flight, the inception as it were of Idaho aviation history?

The Idaho Statesman declared, in an article on April 20, 1911, that Walter Brookins had launched into the air on “the first aeroplane flight ever made in the Gem state” the day before. This, in spite of the fact that the same paper had reported on October 16, 1910, that several flights had taken place above the fairgrounds in Lewiston, the last one ending in disaster.

Lewiston, still smarting today more than 150 years after losing the territorial capital, could be forgiven for being a little perturbed at this oversight.

James J. Ward of Chicago made the first Idaho flight on October 13, 1910. In Lewiston. His engine sputtered, causing him to land a little rougher than he’d hoped and destroying the front wheel of the Curtiss biplane. There were plenty of bicycle wheels in Lewiston, so that was easily replaced. He made several successful flights for the cheering crowd in the grandstand at the Lewiston-Clarkston fairgrounds.

His luck ran out, some would say, on October 14. His engine conked out when he was some 200 feet in the air. That was unlucky. But, luckily, Ward was able to jump free of the plane just as it crashed sustaining only minor injuries. The Idaho Statesman printed a dispatch from Lewiston that read, “The Curtiss biplane with which J.J. Ward of Chicago has been making daily flights at the fair, tonight lies a heap of junk on the banks of the Snake River, and that Ward himself is not in the morgue or at the hospital, is almost a miracle.”

Lewiston can also claim the first attempted flight in Idaho, though it was going to be just a glide. That came about on July 30, 1904, less than a year after the first successful flight of the Wright brothers. Captain Stewart V. Winslow, who during his working hours operated a dredge in the Snake River, tried to get into the air by pedaling a bicycle with wings over a cliff. He planned to glide across the river to the Washington side in triumph. He may have considered it bad luck when his front bicycle wheel collapsed before he could ride the contraption off the cliff. Luckily, he never did make a second try.

But what about that 1911 flight in Boise? It didn’t qualify as the first in the state, but it was the first in Boise, and it was accomplished by an aviation pioneer.

Walter Brookins, the first pilot trained by the Wright brothers, took to the air a few minutes after 5 pm on April 19, 1911 from the center field of the racetrack at the fairgrounds in Boise. Note that the fairgrounds were not located where they are today. They were roughly on the corner of Orchard and Fairview, thus the name of the latter street.

Promoters of the spectacle had cancelled the flight, allegedly because the weather had turned too cold for spectators. The many spectators who had shown up began to grumble and speculate that brisk winds were the real reason for the cancellation and casting aspersions on the pilot. When Brookins heard this he immediately rolled out his biplane and made preparations to meet the winds, which were described as gale force, head on.

One spectator was particularly interested in how Brookins would take to the Boise air. W.O. Kay, of Ogden, Utah, had followed the aviator to Boise, disappointed because he had not been able to take a ride in the Wright Biplane when Brookins had flown in Utah. Kay, who weighed 164 pounds, would have been too great a load for the plane to get into the air over Utah’s capital city. The air was too thin to keep both men aloft at Salt Lake’s elevation of 4,220 feet. Kay and Brookins both thought Boise’s 2,730-foot elevation would allow a passenger.

Without a hint of drama Brookins rolled along in the rough pasture for about 200 feet and rose steadily into the air. He would fly around the racetrack five times, a distance of about three miles, before an easy landing. He could not resist putting on a show for the crowd.

The Idaho Statesman described what happened after the pilot seemed to take an unplanned dip, then recover. “Shortly after thrilling the crowd with this feat he increased his speed as though to descend right into the mob. He shot down at a terrific rate, the terror-stricken people scattering right and left.”

He rose at the last moment and made another circuit of the track before landing. The flight had lasted about 12 minutes, securing Brookins place at the head of the line in Boise’s aviation history.

Brookins performed further feats in the days to come, took Kay on his promised airplane ride, and raced an automobile around the track. He was a sensation. His flights moved Idaho Lieutenant Governor Sweetser to present Walter Brookins with a commission as a colonel in the Idaho National Guard, making Idaho the first state to so honor Brookins for his contribution to aeronautics.

Brookins went on to establish numerous aviation records. Chancy as flying was in those early days, he was never seriously injured (a few broken ribs) while flying. He died in 1953 and is buried at the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation in Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles.

Walter Brookins, the pilot of Boise’s first flight. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Walter Brookins, the pilot of Boise’s first flight. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Published on September 16, 2022 04:00

September 15, 2022

Mrs. Spalding's Letter (Tap to read)

My research methods, though sometimes systematic, are just as of ten serendipitous. I stumble onto something while looking for something else.

This chance method rewarded me recently when I found a transcript of Eliza Spalding’s first letter written to her family at home from her new residence on Lapwai Creek. It was reprinted in the 1922 Biennial Report of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The letter was dated February 16, 1837 and addressed to “Ever Dear Parents, Brothers and Sisters.”

The letter told of the profound eagerness of the Nez Perce for religious instruction: “Mr. S. resolved if possible not to disappoint the unspeakable desire the Nezperces had ever manifested to have us live with them that they might learn about God, and the habits of civilized life.”

Tribal members cut and carried pine logs on their shoulders for half a mile for the Spalding residence. Eliza wrote, “A number of them, one chief in particular, has been sawing at the pit saw for several weeks.”

It was surprising to me that the Nez Perce already had a rudimentary understanding of Christianity when the Spaldings arrived. They had learned of it from an Iroquois Indian who was in the employ of the American Fur Company.

The Spaldings saw in the Nez Perce a readiness to abandon their tribal beliefs and embrace the story of Jesus. Eliza wrote of the “conjurers or medicine men who pretend to heal the sick by their incantations.” She thought tribal members held them in low regard. Her evidence was that several Nez Perce came to her husband, the Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding, seeking a cure for various ailments. “They are very fond of being bled if they are sick, and Mr. S. has really succeeded in doing some of them the favor,” Mrs. Spalding wrote.

The efficacy of bloodletting was likely inferior to some of the native cures that had been passed down through the centuries.

Eliza went on to describe a Nez Perce vision quest in the most skeptical terms: “A youth who wishes this profession goes to the Mts., where he remains alone for 2 days, after which he returns to his friends pretending to be inspired with qualification requisite for healing diseases, that birds and wild beasts came to him while in the mountains and told him that those who employed him must reward him with blankets, horses and various good things. I hope and trust that the gospel will soon cause them to abandon these notions.”

Judge the Spaldings however you will, but I came away after reading the letter with a better appreciation for the sacrifice they had made by coming west. In many ways, they may as well have established their mission on Mars. Here’s what Eliza said about that to her family.

“We probably shall not meet again in this world, but if we fulfill the great end for which we were created, we shall be prepared to meet in one never to be separated. If you have received all the communications, we have directed to you, you have heard from us every few months since we left you. We probably shall write you once in six months. At all events we intend to write every opportunity, for this is the only favor we can show you in our remote situation.”

Mrs. Spalding was 30 years old when she wrote the letter. The births of her four children and the deaths of her friends and fellow missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in the Whitman Massacre were still ahead of her.

Eliza Hart Spalding died in Brownsville, Oregon in 1851 at age 43. She was originally buried there but was later disinterred and buried with her husband at the Lapwai Mission Cemetery in Idaho.

The Spalding Memorial at the Lapwai Mission Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The Spalding Memorial at the Lapwai Mission Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This chance method rewarded me recently when I found a transcript of Eliza Spalding’s first letter written to her family at home from her new residence on Lapwai Creek. It was reprinted in the 1922 Biennial Report of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The letter was dated February 16, 1837 and addressed to “Ever Dear Parents, Brothers and Sisters.”

The letter told of the profound eagerness of the Nez Perce for religious instruction: “Mr. S. resolved if possible not to disappoint the unspeakable desire the Nezperces had ever manifested to have us live with them that they might learn about God, and the habits of civilized life.”

Tribal members cut and carried pine logs on their shoulders for half a mile for the Spalding residence. Eliza wrote, “A number of them, one chief in particular, has been sawing at the pit saw for several weeks.”

It was surprising to me that the Nez Perce already had a rudimentary understanding of Christianity when the Spaldings arrived. They had learned of it from an Iroquois Indian who was in the employ of the American Fur Company.

The Spaldings saw in the Nez Perce a readiness to abandon their tribal beliefs and embrace the story of Jesus. Eliza wrote of the “conjurers or medicine men who pretend to heal the sick by their incantations.” She thought tribal members held them in low regard. Her evidence was that several Nez Perce came to her husband, the Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding, seeking a cure for various ailments. “They are very fond of being bled if they are sick, and Mr. S. has really succeeded in doing some of them the favor,” Mrs. Spalding wrote.

The efficacy of bloodletting was likely inferior to some of the native cures that had been passed down through the centuries.

Eliza went on to describe a Nez Perce vision quest in the most skeptical terms: “A youth who wishes this profession goes to the Mts., where he remains alone for 2 days, after which he returns to his friends pretending to be inspired with qualification requisite for healing diseases, that birds and wild beasts came to him while in the mountains and told him that those who employed him must reward him with blankets, horses and various good things. I hope and trust that the gospel will soon cause them to abandon these notions.”

Judge the Spaldings however you will, but I came away after reading the letter with a better appreciation for the sacrifice they had made by coming west. In many ways, they may as well have established their mission on Mars. Here’s what Eliza said about that to her family.

“We probably shall not meet again in this world, but if we fulfill the great end for which we were created, we shall be prepared to meet in one never to be separated. If you have received all the communications, we have directed to you, you have heard from us every few months since we left you. We probably shall write you once in six months. At all events we intend to write every opportunity, for this is the only favor we can show you in our remote situation.”

Mrs. Spalding was 30 years old when she wrote the letter. The births of her four children and the deaths of her friends and fellow missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in the Whitman Massacre were still ahead of her.

Eliza Hart Spalding died in Brownsville, Oregon in 1851 at age 43. She was originally buried there but was later disinterred and buried with her husband at the Lapwai Mission Cemetery in Idaho.

The Spalding Memorial at the Lapwai Mission Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The Spalding Memorial at the Lapwai Mission Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on September 15, 2022 04:00

September 14, 2022

Ballooning Persistence (Tap to read)

I found this one surprisingly hard to write. More about that in a moment.

Hawthorne C. Gray was a driven man. The Coeur d’Alene High School and University of Idaho graduate was the son of Captain W.P. Gray who piloted the steamer Georgie Oaks on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Hawthorne Gray joined the Idaho National Guard after graduating from U of I, and later the U.S. Army. Early on in his army career, in 1916, he fought in the Pancho Villa Expedition, serving as an infantry private. In 1917 he was commissioned a second lieutenant and in 1920 transferred to the U.S. Army Air Service as a captain. Shortly after that Gray caught the balloon bug.

He participated in some major balloon races, finishing second in the 1926 Gordon Bennett, the premiere race for gas balloonists. Then he set his sights on the altitude record for gas balloons. In 1927 he set an unofficial altitude record at 28,510 feet. He passed out during the attempt and awoke as the balloon was descending on its own just in time to throw off ballast and land safely.

In May that same year he went up again, smashing the altitude record for a human being by taking his balloon to 42,470 feet. But that record would remain unofficial. The balloon was dropping like a rock and he bailed out at 8,000 feet, parachuting to safety. Since he did not ride the bag down the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the organization that sanctioned such records, refused to recognize it.

So, back into the air. He made his third attempt in November 1927, rising ultimately to somewhere between 43,000 and 44,000 feet. Alas, once again he passed out. This time that proved fatal. Hawthorne Gray died in his final record attempt. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, posthumously.

That’s a sad story, but why would it be difficult for me to write? Because I had a friend and kayak partner who spent some years in the army, as did Gray. Carol was a flight surgeon. She was passionate about balloons, too, and once broke the altitude record for a woman in a gas balloon. She also won, along with ballooning partner Richard Abruzzo, the 2004 Gordon Bennett balloon race. They competed in that race twice more. In 2010 Carol Rymer Davis, driven in much the same way Hawthorne Gray was, went down with Richard Abruzzo over the Adriatic in a thunderstorm during the Gordon Bennett. They both died.

Hawthorne C. Gray was a driven man. The Coeur d’Alene High School and University of Idaho graduate was the son of Captain W.P. Gray who piloted the steamer Georgie Oaks on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Hawthorne Gray joined the Idaho National Guard after graduating from U of I, and later the U.S. Army. Early on in his army career, in 1916, he fought in the Pancho Villa Expedition, serving as an infantry private. In 1917 he was commissioned a second lieutenant and in 1920 transferred to the U.S. Army Air Service as a captain. Shortly after that Gray caught the balloon bug.

He participated in some major balloon races, finishing second in the 1926 Gordon Bennett, the premiere race for gas balloonists. Then he set his sights on the altitude record for gas balloons. In 1927 he set an unofficial altitude record at 28,510 feet. He passed out during the attempt and awoke as the balloon was descending on its own just in time to throw off ballast and land safely.

In May that same year he went up again, smashing the altitude record for a human being by taking his balloon to 42,470 feet. But that record would remain unofficial. The balloon was dropping like a rock and he bailed out at 8,000 feet, parachuting to safety. Since he did not ride the bag down the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the organization that sanctioned such records, refused to recognize it.

So, back into the air. He made his third attempt in November 1927, rising ultimately to somewhere between 43,000 and 44,000 feet. Alas, once again he passed out. This time that proved fatal. Hawthorne Gray died in his final record attempt. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, posthumously.

That’s a sad story, but why would it be difficult for me to write? Because I had a friend and kayak partner who spent some years in the army, as did Gray. Carol was a flight surgeon. She was passionate about balloons, too, and once broke the altitude record for a woman in a gas balloon. She also won, along with ballooning partner Richard Abruzzo, the 2004 Gordon Bennett balloon race. They competed in that race twice more. In 2010 Carol Rymer Davis, driven in much the same way Hawthorne Gray was, went down with Richard Abruzzo over the Adriatic in a thunderstorm during the Gordon Bennett. They both died.

Published on September 14, 2022 04:00

September 13, 2022

A Wayward Sheriff (Tap to read)

George H. Pease seemed like a solid guy. He was the six-foot-six sheriff of Kootenai County in 1898 and he had put together a group of 112 men who were ready to volunteer to fight in the Spanish-American War. Governor Steunenberg took Captain Pease up on his offer, but needed just 50 men, and no officers. So, the Sheriff stayed home. He wouldn’t stay for long.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

Published on September 13, 2022 04:00

September 12, 2022

Idaho Freedom Riders (Tap to read)

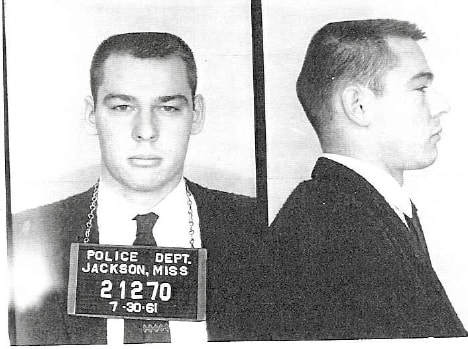

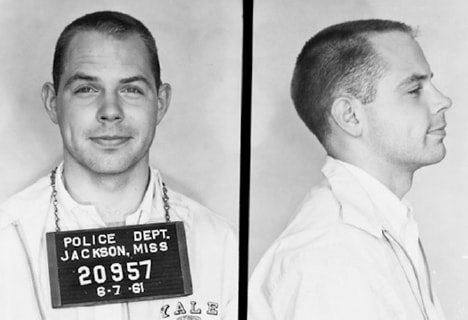

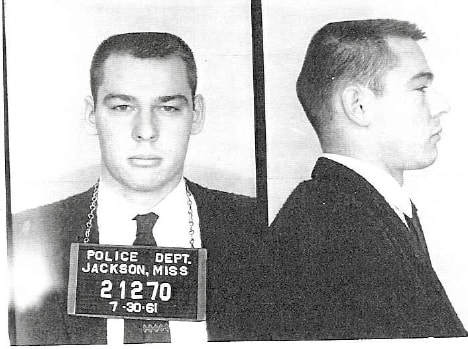

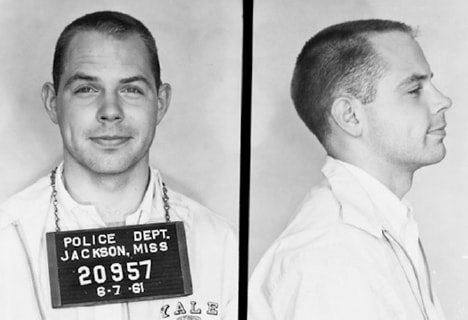

Some mugshots mean more than they would seem. Today we’re going to feature two men with strong Idaho ties who should be proud of their mugshots.

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement.

Max Pavesic

Max Pavesic  Edward Kale

Edward Kale

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement.

Max Pavesic

Max Pavesic  Edward Kale

Edward Kale

Published on September 12, 2022 04:00

September 11, 2022

First Boise Buzz Wagon Wreck (Tap to read)

The 1907 headline read “Buzz Wagon Parties Now a Fad.” The Idaho Statesman hadn’t yet settled on what to call automobiles. “Buzz wagon” didn’t catch on, fading as fast as the fad.

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Published on September 11, 2022 04:00

September 10, 2022

An Idaho Delegation (Tap to read)

There are no Republicans in this picture showing the Idaho Congressional delegation meeting with President John F. Kennedy in 1961. I’m posting this because it’s a great picture and to show that Idaho’s delegation once consisted of nearly all Democrats. Yes, shocking, but true. Missing from the photo, but a member of the delegation at the time was Republican Senator Len B. Jordon. His photo is below.

There are no Republicans in this picture showing the Idaho Congressional delegation meeting with President John F. Kennedy in 1961. I’m posting this because it’s a great picture and to show that Idaho’s delegation once consisted of nearly all Democrats. Yes, shocking, but true. Missing from the photo, but a member of the delegation at the time was Republican Senator Len B. Jordon. His photo is below.

Published on September 10, 2022 04:00

September 9, 2022

Poor Coyote's Cabin (Tap to read)

Sometimes the story is that there’s not much of a story there. I ran across this photo of “Poor Coyote’s Cabin” while looking for whoknowswhat in the Library of Congress digital collection. That humble little cabin huddled there beneath a highway overpass intrigued me.

Beth Erdey, PhD, archivist for the Nez Perce National Historic Park at Spalding quickly calmed my curiosity. She sent me some documents about the cabin, including a query from 1986 asking if it might be eligible for a National Register of Historic Places listing. The answer: Not really.

There simply wasn’t enough information about the old cabin to justify its inclusion. It was moved in 1936 from what may have been its original location in Coyote’s Gulch to a site near Spalding, then moved at least once more to the site beneath the abandoned highway overpass near the NPS visitor center. At least one of the moves was not done correctly and some logs were reassembled out of order. Because of those moves the cabin was no longer in its historical setting and it didn’t retain the integrity of workmanship one would like to see on the National Register.

Even so, the cabin might have made the cut if we knew something more about it. It was probably built sometime after 1880. We don’t know who built it or even where it was originally located, but a Nez Perce Indian named Poor Coyote lived in it from 1895 until his death in 1915. Next to nothing is known about Poor Coyote, save for his evocative name.

The 1936 move was done by Joe Evans. He and his wife, Pauline, operated a museum at Spalding and they used the cabin as part of their exhibit. It was called the “Jackson Sundown” cabin by Joe and Pauline, and artifacts purportedly belonging to the famous rodeo rider were displayed there. There’s no evidence Sundown had anything to do with the cabin, and the veracity of the “curators” is questionable. They often didn’t let provenance get in the way of a good story.

In 1965 or 1970 (records are unclear) the cabin was again moved and placed beneath the old Highway 95 overpass, perhaps to protect it from the elements. NPS deconstructed the cabin in 1990, saving some elements of it for the museum collection.

So, little but that curious name, Poor Coyote, remains. We are left to wonder who he was and what his name might have meant to those who gave it to him. Was he not a very good coyote? Was he underprivileged? Are we to simply feel sorry for him? If someone out there in internet lands knows more, please share what you know with us.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Beth Erdey, PhD, archivist for the Nez Perce National Historic Park at Spalding quickly calmed my curiosity. She sent me some documents about the cabin, including a query from 1986 asking if it might be eligible for a National Register of Historic Places listing. The answer: Not really.

There simply wasn’t enough information about the old cabin to justify its inclusion. It was moved in 1936 from what may have been its original location in Coyote’s Gulch to a site near Spalding, then moved at least once more to the site beneath the abandoned highway overpass near the NPS visitor center. At least one of the moves was not done correctly and some logs were reassembled out of order. Because of those moves the cabin was no longer in its historical setting and it didn’t retain the integrity of workmanship one would like to see on the National Register.

Even so, the cabin might have made the cut if we knew something more about it. It was probably built sometime after 1880. We don’t know who built it or even where it was originally located, but a Nez Perce Indian named Poor Coyote lived in it from 1895 until his death in 1915. Next to nothing is known about Poor Coyote, save for his evocative name.

The 1936 move was done by Joe Evans. He and his wife, Pauline, operated a museum at Spalding and they used the cabin as part of their exhibit. It was called the “Jackson Sundown” cabin by Joe and Pauline, and artifacts purportedly belonging to the famous rodeo rider were displayed there. There’s no evidence Sundown had anything to do with the cabin, and the veracity of the “curators” is questionable. They often didn’t let provenance get in the way of a good story.

In 1965 or 1970 (records are unclear) the cabin was again moved and placed beneath the old Highway 95 overpass, perhaps to protect it from the elements. NPS deconstructed the cabin in 1990, saving some elements of it for the museum collection.

So, little but that curious name, Poor Coyote, remains. We are left to wonder who he was and what his name might have meant to those who gave it to him. Was he not a very good coyote? Was he underprivileged? Are we to simply feel sorry for him? If someone out there in internet lands knows more, please share what you know with us.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Published on September 09, 2022 04:00

September 8, 2022

"Little Borah" (Tap to read)

Our appetite for scandal seems not to diminish with history’s passing years. If you are above it, give yourself a gold star and quit reading now.

Okay, anyone still with me?

William Borah was a Boise attorney who went up against Clarence Darrow as one of the prosecutors of “Big” Bill Haywood. Haywood was acquitted but the trial brought national fame to Borah.

At the time of the trial in 1907, Borah had already been selected as a U.S. Senator from Idaho. That was when legislatures named senators. He had time for the trial because Congress didn’t start their sessions until December in those days. Borah replaced the vehemently anti-Mormon Fred T. Dubois. No scandal there, though no doubt there was some backroom intrigue, par for the course in elections on the floor.

No scandal, either, when Borah was reelected by the Legislature in 1912, or when he was elected and re-elected by the citizens in Idaho in 1918, 1924, 1930, and 1936.

Borah started showing up on presidential nomination ballots at Republican National Conventions beginning in 1916. He got the most votes in the Presidential Primaries in 1936, but Alf Landon won the nomination that year at the convention. Again, no scandal.

The scandal wasn’t on the political side for Borah, but on the personal side.

In 1895, Borah married the daughter of Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell. Mary McConnell was a lovely, tiny woman who during their years in Washington was often referred to as “Little Borah.” They had no children. And there’s the scandal. The senator apparently did.

Rumors of philandering dogged Senator Borah for years. Of particular interest for this particular scandal, was an affair he had with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt that was later confirmed by her diary entries.

Alice was married to Representative Nicholas Longworth III, who served as Speaker of the House. The daughter in question was ultimately named Paulina, but Alice, who had a wicked sense of humor, reportedly toyed with the idea of naming her Deborah. Deborah could have been read as De Borah, you see. According to H.W. Brands’ book A Traitor to His Class ,* which is largely about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Paulina was often referred to by D.C. wags as “Aurora Borah Alice.”

And, there you have it. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Okay, anyone still with me?

William Borah was a Boise attorney who went up against Clarence Darrow as one of the prosecutors of “Big” Bill Haywood. Haywood was acquitted but the trial brought national fame to Borah.

At the time of the trial in 1907, Borah had already been selected as a U.S. Senator from Idaho. That was when legislatures named senators. He had time for the trial because Congress didn’t start their sessions until December in those days. Borah replaced the vehemently anti-Mormon Fred T. Dubois. No scandal there, though no doubt there was some backroom intrigue, par for the course in elections on the floor.

No scandal, either, when Borah was reelected by the Legislature in 1912, or when he was elected and re-elected by the citizens in Idaho in 1918, 1924, 1930, and 1936.

Borah started showing up on presidential nomination ballots at Republican National Conventions beginning in 1916. He got the most votes in the Presidential Primaries in 1936, but Alf Landon won the nomination that year at the convention. Again, no scandal.

The scandal wasn’t on the political side for Borah, but on the personal side.

In 1895, Borah married the daughter of Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell. Mary McConnell was a lovely, tiny woman who during their years in Washington was often referred to as “Little Borah.” They had no children. And there’s the scandal. The senator apparently did.

Rumors of philandering dogged Senator Borah for years. Of particular interest for this particular scandal, was an affair he had with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt that was later confirmed by her diary entries.

Alice was married to Representative Nicholas Longworth III, who served as Speaker of the House. The daughter in question was ultimately named Paulina, but Alice, who had a wicked sense of humor, reportedly toyed with the idea of naming her Deborah. Deborah could have been read as De Borah, you see. According to H.W. Brands’ book A Traitor to His Class ,* which is largely about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Paulina was often referred to by D.C. wags as “Aurora Borah Alice.”

And, there you have it. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Published on September 08, 2022 04:00