Rick Just's Blog, page 87

August 8, 2022

The Fortune Teller (Tap to read)

Countless people have tried to find the loot from what is sometimes called the “Robbers’ Roost Holdup,” somewhere between $40,000 and $86,000 worth. Note those were 1865 dollars, which would be worth north of $2 million today. Calculating just where that gold from a stagecoach robbery might be buried has kept many a treasure hunter up at night.

In 1929 there was only one man alive who knew where the gold was. At least, that’s what A.B. Meyer told Agnes Schwabe of McCammon. The original robbery took place not far from McCammon. The 1929 theft took place in Mrs. Schwabe’s house.

Meyer received his unique knowledge by way of clairvoyancy. During a séance he told Mrs. Schwabe all about the hidden loot. She was excited enough to give Meyer the $500 he needed for “excavations.” Once he had the money he took a hurried departure.

The fortune teller, who worked out of Pocatello, was also exceedingly helpful to Mrs. H.C. Lyon Harris of that city. It was fame, not fortune, that lured Mrs. Harris. Meyer promised that he could use his clairvoyancy, somehow, to secure a motion picture contract for her daughter. When the seer skipped with Mrs. Harris’ $250, she joined the complaint of Mrs. Schwabe and an arrest warrant was issued. Meanwhile, Meyer had convinced an American Falls man to give him $200 on the promise of a job at Henry Ford’s marvelous, and fictional, mine in Idaho.

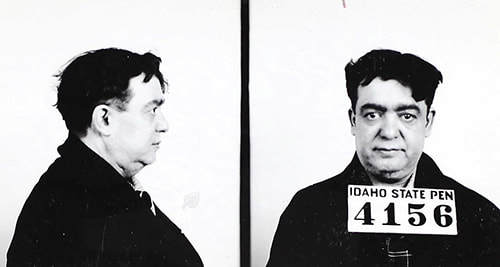

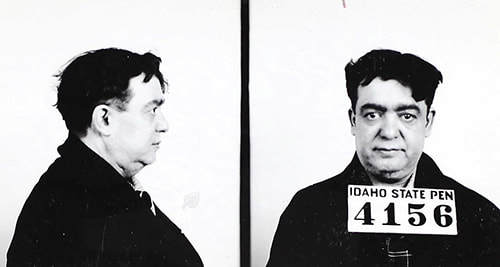

A.B. Meyer, which was actually the alias of Sam Stevens, was caught in Salem, Oregon and brought back to Idaho for trial. Stevens was convicted of fraud and appealed his conviction to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court looked into their crystal ball and envisioned him spending the next 5 to 14 years in prison.

Which he didn’t.

Eighteen months after he entered the Idaho State Penitentiary, Sam Stevens, aka A.B. Meyer, was pardoned by the board of pardons and paroles and told to leave the state and join his wife and child in Colorado.

But he wasn’t quite done with fortune telling.

“Pardoned Prison Clairvoyant Reveals Future for Warden,” read the headline on the front page of the July 9, 1931 Idaho Statesman. Stevens left a note for Warden R.E. Thomas that predicted that Governor C. Ben Ross would be re-elected and that the warden would be reappointed. Ross was re-elected. Thomas was not reappointed. So, batting .500. The note also had something of an apology because Stevens had “a presentiment about Lyda Southard leaving but (was) afraid to reveal it for fear you would think me silly.” Southard had escaped, but that’s another story.

Stevens’ prison records describe him as just short of 5’ 4” and 159 pounds. He was short, “very stout,” with bad teeth and a double chin. His listed occupation was Fortune Teller.

In 1929 there was only one man alive who knew where the gold was. At least, that’s what A.B. Meyer told Agnes Schwabe of McCammon. The original robbery took place not far from McCammon. The 1929 theft took place in Mrs. Schwabe’s house.

Meyer received his unique knowledge by way of clairvoyancy. During a séance he told Mrs. Schwabe all about the hidden loot. She was excited enough to give Meyer the $500 he needed for “excavations.” Once he had the money he took a hurried departure.

The fortune teller, who worked out of Pocatello, was also exceedingly helpful to Mrs. H.C. Lyon Harris of that city. It was fame, not fortune, that lured Mrs. Harris. Meyer promised that he could use his clairvoyancy, somehow, to secure a motion picture contract for her daughter. When the seer skipped with Mrs. Harris’ $250, she joined the complaint of Mrs. Schwabe and an arrest warrant was issued. Meanwhile, Meyer had convinced an American Falls man to give him $200 on the promise of a job at Henry Ford’s marvelous, and fictional, mine in Idaho.

A.B. Meyer, which was actually the alias of Sam Stevens, was caught in Salem, Oregon and brought back to Idaho for trial. Stevens was convicted of fraud and appealed his conviction to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court looked into their crystal ball and envisioned him spending the next 5 to 14 years in prison.

Which he didn’t.

Eighteen months after he entered the Idaho State Penitentiary, Sam Stevens, aka A.B. Meyer, was pardoned by the board of pardons and paroles and told to leave the state and join his wife and child in Colorado.

But he wasn’t quite done with fortune telling.

“Pardoned Prison Clairvoyant Reveals Future for Warden,” read the headline on the front page of the July 9, 1931 Idaho Statesman. Stevens left a note for Warden R.E. Thomas that predicted that Governor C. Ben Ross would be re-elected and that the warden would be reappointed. Ross was re-elected. Thomas was not reappointed. So, batting .500. The note also had something of an apology because Stevens had “a presentiment about Lyda Southard leaving but (was) afraid to reveal it for fear you would think me silly.” Southard had escaped, but that’s another story.

Stevens’ prison records describe him as just short of 5’ 4” and 159 pounds. He was short, “very stout,” with bad teeth and a double chin. His listed occupation was Fortune Teller.

Published on August 08, 2022 04:00

August 7, 2022

Harriman Series Part Seven (Tap to read)

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman (www.writersatharriman.org). So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

I started out this short series by saying that the Railroad Ranch, which became Harriman State Park of Idaho, was crucial in the formation of Idaho’s state park system.

Gov. Robert E. Smylie (right in the picture) started trying to consolidate Idaho’s parks into a professional agency dedicated to their preservation and management in 1959. The Idaho Legislature was cool to the idea and turned the governor down on several occasions.

Then an opportunity came along that Smylie was quick to recognize. The governor had known E. Roland Harriman (left in the picture) for some time when the co-owner of the Railroad Ranch called.

Harriman and his brother Averell wanted to see the Railroad Ranch protected from development by donating it to the State of Idaho. Governor Smylie saw this as his chance to create a park system. Working mostly with Roland Harriman, the majority owner, Smylie inserted language in the gift deed that Idaho would be required to have a professionally trained park service in place before the transfer of the property was made.

Even with the donation of the Railroad Ranch as a tempting carrot, the 1963 legislature refused Smylie his state parks department, one more time. But they DID gladly accept the donation of the Railroad Ranch, which set things in motion so that the 1965 legislature finally gave Smylie his Idaho Department of Parks.

The donation was worth millions. The Idaho Department of Parks used that donation to match federal money in the Land and Water Conservation Fund to make other significant park improvements across the state.

So, in a way, Harriman State Park of Idaho, which didn’t open to the public until 1982, was the real beginning of the state park system in 1965.

By the way, the official name of the park is Harriman State Park of Idaho. That’s to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York. Same family. Same generosity.

I started out this short series by saying that the Railroad Ranch, which became Harriman State Park of Idaho, was crucial in the formation of Idaho’s state park system.

Gov. Robert E. Smylie (right in the picture) started trying to consolidate Idaho’s parks into a professional agency dedicated to their preservation and management in 1959. The Idaho Legislature was cool to the idea and turned the governor down on several occasions.

Then an opportunity came along that Smylie was quick to recognize. The governor had known E. Roland Harriman (left in the picture) for some time when the co-owner of the Railroad Ranch called.

Harriman and his brother Averell wanted to see the Railroad Ranch protected from development by donating it to the State of Idaho. Governor Smylie saw this as his chance to create a park system. Working mostly with Roland Harriman, the majority owner, Smylie inserted language in the gift deed that Idaho would be required to have a professionally trained park service in place before the transfer of the property was made.

Even with the donation of the Railroad Ranch as a tempting carrot, the 1963 legislature refused Smylie his state parks department, one more time. But they DID gladly accept the donation of the Railroad Ranch, which set things in motion so that the 1965 legislature finally gave Smylie his Idaho Department of Parks.

The donation was worth millions. The Idaho Department of Parks used that donation to match federal money in the Land and Water Conservation Fund to make other significant park improvements across the state.

So, in a way, Harriman State Park of Idaho, which didn’t open to the public until 1982, was the real beginning of the state park system in 1965.

By the way, the official name of the park is Harriman State Park of Idaho. That’s to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York. Same family. Same generosity.

Published on August 07, 2022 04:00

August 6, 2022

Harriman Series Part Six (Tap to read)

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman (www.writersatharriman.org). So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Today we’re remembering some of the better-known people who spent time at the Railroad Ranch in Island Park.

On the left is Baroness Hilla von Rebay posing with a ranch horse. She was a noted abstract artist in the early 20th century and cofounder and first director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. Next is Guggenheim himself in a formal pose. He and his brothers Daniel and Morris purchased three cabin lots at the Railroad Ranch in 1906. The brothers sold out to the Harrimans, but Solomon retained his ranch share and properties until his death in 1949. The Guggenheims’ wealth came from copper mining.

On horseback are Charles Jones and his wife, Jenny. They built a guesthouse on the property formerly owned by Solomon Guggenheim in 1955. Jones ran Richfield Oil Corporation. The Harrimans purchased Jones’s share in 1961. After Charles Jones died in 1970, Jenny Jones donated the furnishings of the house to the State of Idaho. It is used today to orient visitors for tours and as a seasonal employee residence.

Today we’re remembering some of the better-known people who spent time at the Railroad Ranch in Island Park.

On the left is Baroness Hilla von Rebay posing with a ranch horse. She was a noted abstract artist in the early 20th century and cofounder and first director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. Next is Guggenheim himself in a formal pose. He and his brothers Daniel and Morris purchased three cabin lots at the Railroad Ranch in 1906. The brothers sold out to the Harrimans, but Solomon retained his ranch share and properties until his death in 1949. The Guggenheims’ wealth came from copper mining.

On horseback are Charles Jones and his wife, Jenny. They built a guesthouse on the property formerly owned by Solomon Guggenheim in 1955. Jones ran Richfield Oil Corporation. The Harrimans purchased Jones’s share in 1961. After Charles Jones died in 1970, Jenny Jones donated the furnishings of the house to the State of Idaho. It is used today to orient visitors for tours and as a seasonal employee residence.

Published on August 06, 2022 04:00

August 5, 2022

Harriman Series Part Five (Tap to read)

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman (www.writersatharriman.org). So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

The Railroad Ranch, when it was owned by the Harrimans had many famous visitors. Probably none were better known than the Harrimans themselves.

Averell Harriman on the left is shown at the ranch in 1937. He served as US secretary of commerce under President Truman and later as governor of New York. He twice ran for president as a Democrat, in 1952 and 1956, defeated by Adlai Stevenson both times. He served as ambassador to the United Kingdom and to the Soviet Union. And, of course, he is remembered in Idaho as the developer of Sun Valley Ski Resort when he headed Union Pacific.

In the picture on the right is then Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Director Yvonne Ferrell with Pamela Harriman during a 1990s visit to the park. Pamela, in the hat, was the third wife of Averell. She was acquainted with many of the most famous figures of the 20th century, from Adolph Hitler, whom she met as a teenager, to Winston Churchill, who was her father-in-law during her first marriage. Pres. Bill Clinton appointed her ambassador to France in 1993.

The picture of Yvonne and Pamela happens to be one I took. Pamela brought Richard Helms with her on this visit. I don’t know why I don’t have a picture of him. Maybe as the former director of the CIA he just didn’t show up in photos.

The Railroad Ranch, when it was owned by the Harrimans had many famous visitors. Probably none were better known than the Harrimans themselves.

Averell Harriman on the left is shown at the ranch in 1937. He served as US secretary of commerce under President Truman and later as governor of New York. He twice ran for president as a Democrat, in 1952 and 1956, defeated by Adlai Stevenson both times. He served as ambassador to the United Kingdom and to the Soviet Union. And, of course, he is remembered in Idaho as the developer of Sun Valley Ski Resort when he headed Union Pacific.

In the picture on the right is then Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Director Yvonne Ferrell with Pamela Harriman during a 1990s visit to the park. Pamela, in the hat, was the third wife of Averell. She was acquainted with many of the most famous figures of the 20th century, from Adolph Hitler, whom she met as a teenager, to Winston Churchill, who was her father-in-law during her first marriage. Pres. Bill Clinton appointed her ambassador to France in 1993.

The picture of Yvonne and Pamela happens to be one I took. Pamela brought Richard Helms with her on this visit. I don’t know why I don’t have a picture of him. Maybe as the former director of the CIA he just didn’t show up in photos.

Published on August 05, 2022 04:00

August 4, 2022

Harriman Series Part Four (Tap to read)

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman (www.writersatharriman.org). So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Many famous folks visited the Railroad Ranch over the years. We have some pictures of some of them, starting with John Muir. The picture on the left wasn’t taken at the ranch, though it looks like it could be. Muir was friends with E.H. Harriman, who was a big supporter of Muir in the Hetch Hetchy debate, which involved plans to build a dam in the area of Yosemite National Park. Muir was along on the famous 1899 Alaska Expedition, sponsored by E.H. Harriman. He visited the ranch in 1913. Some of his diary entries and sketches are featured on interpretive signs in the park today.

You probably haven’t heard of some of the famous visitors to the ranch, because fame is fleeting. On the right is Marriner S. Eccles. He was a well-known economist who served as chairman of the Federal Reserve under Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and was a proponent of New Deal programs. The Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC, is named after Eccles. He wasn’t just a visitor. He was one of the original investors in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company.

Tomorrow, two more contemporary ranch visitors you may have heard about in the news.

Published on August 04, 2022 05:44

August 3, 2022

Harriman Series Part Three (Tap to read)

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman (www.writersatharriman.org). So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Raising cattle year-round at 6,200 feet above sea level calls for harvesting a lot of grass hay. In the picture on the left, five sickle bar horse-drawn mowers knock down the grass. The Harrimans bought an early steam tractor for use in the hay harvest but found that it did not work well because of the configuration of the fields and irrigation ditches, so they largely stuck with horse-drawn equipment.

There were several variations of the beaver slide, like the one on the right used at the Railroad Ranch. The purpose of each was to use horsepower—later tractor power—to slide a load of hay up into the air and push it off onto a stack. The Railroad Ranch supplied beef to the Army during World War II. After the war, they stopped keeping cattle year-round, so they also stopped harvesting and stacking hay.

Cattle were not the only livestock raised on the Railroad Ranch. For a time, elk were commercially raised and shipped to markets in the east and sometimes for the Harriman’s table in New York. The ranch also tried raising bison commercially but found that they were very difficult to keep contained.

Bison were once native to what is called the Island Park area of eastern Idaho, north of Idaho Falls, so it made some sense to try raising them commercially, too. Masters at jumping over or smashing down fences, bison proved more trouble than they were worth.

Raising livestock was always just an excuse to keep a ranch for the Harrimans. They loved to just be at the place. Often they invited their famous friends to join them. We’ll meet a few of those folks tomorrow.

Raising cattle year-round at 6,200 feet above sea level calls for harvesting a lot of grass hay. In the picture on the left, five sickle bar horse-drawn mowers knock down the grass. The Harrimans bought an early steam tractor for use in the hay harvest but found that it did not work well because of the configuration of the fields and irrigation ditches, so they largely stuck with horse-drawn equipment.

There were several variations of the beaver slide, like the one on the right used at the Railroad Ranch. The purpose of each was to use horsepower—later tractor power—to slide a load of hay up into the air and push it off onto a stack. The Railroad Ranch supplied beef to the Army during World War II. After the war, they stopped keeping cattle year-round, so they also stopped harvesting and stacking hay.

Cattle were not the only livestock raised on the Railroad Ranch. For a time, elk were commercially raised and shipped to markets in the east and sometimes for the Harriman’s table in New York. The ranch also tried raising bison commercially but found that they were very difficult to keep contained.

Bison were once native to what is called the Island Park area of eastern Idaho, north of Idaho Falls, so it made some sense to try raising them commercially, too. Masters at jumping over or smashing down fences, bison proved more trouble than they were worth.

Raising livestock was always just an excuse to keep a ranch for the Harrimans. They loved to just be at the place. Often they invited their famous friends to join them. We’ll meet a few of those folks tomorrow.

Published on August 03, 2022 04:00

August 2, 2022

Harriman Series Part Two (Tap to read)

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman (www.writersatharriman.org). So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Yesterday, I mentioned that the Railroad Ranch was named that because several of the shareholders were railroad men, but that there never was a railroad at the ranch. There was one not far away, though.

Although Averell Harriman, well known in Idaho for creating the Sun Valley Resort when he ran Union Pacific Railroad, spent some time at the ranch, it was his brother Roland and wife Gladys who spent the most time there.

The picture on the left shows some of the Hereford cattle that were raised on the Railroad Ranch. In this shot from around 1960, Gladys Harriman is on her white horse, Geronimo, and E. Roland is on his horse, Buck. They were taking the herd a short distance to the Island Park siding to be shipped to market. In the picture on the right from about 1938, Elizabeth “Betty” Harriman is on her horse, Challis, helping move cattle at the nearby Island Park siding. Her sister Phyllis is on the fence. They were the daughters of Roland and Gladys Harriman.

Tomorrow, a little about what it took to raise cattle at 6,200 feet above sea level.

Yesterday, I mentioned that the Railroad Ranch was named that because several of the shareholders were railroad men, but that there never was a railroad at the ranch. There was one not far away, though.

Although Averell Harriman, well known in Idaho for creating the Sun Valley Resort when he ran Union Pacific Railroad, spent some time at the ranch, it was his brother Roland and wife Gladys who spent the most time there.

The picture on the left shows some of the Hereford cattle that were raised on the Railroad Ranch. In this shot from around 1960, Gladys Harriman is on her white horse, Geronimo, and E. Roland is on his horse, Buck. They were taking the herd a short distance to the Island Park siding to be shipped to market. In the picture on the right from about 1938, Elizabeth “Betty” Harriman is on her horse, Challis, helping move cattle at the nearby Island Park siding. Her sister Phyllis is on the fence. They were the daughters of Roland and Gladys Harriman.

Tomorrow, a little about what it took to raise cattle at 6,200 feet above sea level.

Published on August 02, 2022 04:00

August 1, 2022

Harriman Series Part One (Tap to read)

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman (www.writersatharriman.org). So, I’ll also be spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Idaho’s first state park, Heyburn, came into being in 1908. But something else happened that same year that would be even more important in creating a state park system in Idaho. E. H. Harriman, the man in the middle of this photo, bought into a ranch in eastern Idaho.

Harriman was a railroad baron who ran Union Pacific Railroad. E.H. would never see the Railroad Ranch. He died in 1909. His sons, Averell on the left, and Roland, on the right, would be the Harrimans who most enjoyed the ranch. They made many trips there with their mother as boys and young men.

Although it was officially the Island Park Land and Cattle Company, locals called the operation the Railroad Ranch because some other railroad men associated with the Oregon Shortline owned shares in it. The Oregon Shortline, so named because it was the shortest way to get freight from Wyoming to Oregon, was a subsidiary of Union Pacific.

One thing you need to understand about the Railroad Ranch is that there was never a railroad there. More about that tomorrow.

Idaho’s first state park, Heyburn, came into being in 1908. But something else happened that same year that would be even more important in creating a state park system in Idaho. E. H. Harriman, the man in the middle of this photo, bought into a ranch in eastern Idaho.

Harriman was a railroad baron who ran Union Pacific Railroad. E.H. would never see the Railroad Ranch. He died in 1909. His sons, Averell on the left, and Roland, on the right, would be the Harrimans who most enjoyed the ranch. They made many trips there with their mother as boys and young men.

Although it was officially the Island Park Land and Cattle Company, locals called the operation the Railroad Ranch because some other railroad men associated with the Oregon Shortline owned shares in it. The Oregon Shortline, so named because it was the shortest way to get freight from Wyoming to Oregon, was a subsidiary of Union Pacific.

One thing you need to understand about the Railroad Ranch is that there was never a railroad there. More about that tomorrow.

Published on August 01, 2022 04:00

July 31, 2022

July 30, 2022

Some Place Names (Tap to read)

If I want to dash off a blog post in just a few minutes, I can always count on place names as a subject. To wit:

Sometimes—often—we just don’t know where a name came from. Arimo is one Idaho example. Idaho, a Guide in Word and Picture , the travel guide/history edited by Vardis Fisher in 1937 for the Federal Writers Project, says that Arimo is an Indian word meaning “an uncle who bawls like a cow.” That seems like something you wouldn’t really need a unique word for, given the number of times its likely to come up in conversation. Meanwhile, Lalia Boone’s book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary lists it as the name of a red-haired Indian chief, though it adds the adverb “supposedly” to the description to tip the reader to the uncertainty of the definition.

Montpelier’s name has a solid provenance. It was named for Montpelier, Vermont by a man who was born there, Brigham Young. The city in Vermont was, in turn, named after a city in the south of France.

Picabo, Idaho gained some fame thanks to its namesake Picabo Street, the Olympian. It is (here comes that adverb) supposedly an Indian word meaning either “come in” or “silver water,” two meanings that could so easily be confused. Obviously. Oh, and the Indian inviting you into, perhaps, that silver water, would probably have pronounced it Pee-Kah’-bow.

One of the prettiest place names in Idaho is a combination of the names Julia and Etta, daughters of postmaster Charles Snyder. Juliaetta had previously been named Schupferville. Good call, dad.

Sinker Butte and Sinker Creek in Southwest Idaho are named either because the creek sinks out of site intermittently in the desert, or because early settlers used gold nuggets as sinkers on their fishing lines. I’m leaning toward the former, but the latter certainly has its charm.

Brigham Young named Montpelier.

Brigham Young named Montpelier.

Sometimes—often—we just don’t know where a name came from. Arimo is one Idaho example. Idaho, a Guide in Word and Picture , the travel guide/history edited by Vardis Fisher in 1937 for the Federal Writers Project, says that Arimo is an Indian word meaning “an uncle who bawls like a cow.” That seems like something you wouldn’t really need a unique word for, given the number of times its likely to come up in conversation. Meanwhile, Lalia Boone’s book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary lists it as the name of a red-haired Indian chief, though it adds the adverb “supposedly” to the description to tip the reader to the uncertainty of the definition.

Montpelier’s name has a solid provenance. It was named for Montpelier, Vermont by a man who was born there, Brigham Young. The city in Vermont was, in turn, named after a city in the south of France.

Picabo, Idaho gained some fame thanks to its namesake Picabo Street, the Olympian. It is (here comes that adverb) supposedly an Indian word meaning either “come in” or “silver water,” two meanings that could so easily be confused. Obviously. Oh, and the Indian inviting you into, perhaps, that silver water, would probably have pronounced it Pee-Kah’-bow.

One of the prettiest place names in Idaho is a combination of the names Julia and Etta, daughters of postmaster Charles Snyder. Juliaetta had previously been named Schupferville. Good call, dad.

Sinker Butte and Sinker Creek in Southwest Idaho are named either because the creek sinks out of site intermittently in the desert, or because early settlers used gold nuggets as sinkers on their fishing lines. I’m leaning toward the former, but the latter certainly has its charm.

Brigham Young named Montpelier.

Brigham Young named Montpelier.

Published on July 30, 2022 04:00