Rick Just's Blog, page 2

January 18, 2025

The Shortest Prison Term

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page about once a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.

On a cold February day in 1916, subscribers to the Idaho Statesman woke up to a chilling image. The headline read, “MOTHER PARTS FROM BABE AT PRISON GATE.”

The stacked headlines, common in the day, told the worst of the story:

“Leaves Infant at Children’s Home While She Serves in Penitentiary”

“NO PRISON ACCOMMODATION”

Then, the zinger:

“Governor Vetoed Appropriation to Provide

Addition Women’s Ward.”

If you didn’t have the gist after four headlines, the article started with, “A pathetic scene was enacted at the Childrens’ Home Funding Society Friday afternoon when a sobbing little woman parted with her two-months-old babe, leaving the infant in the dainty basinet (sic) in the nursery of the Childrens’ home, while the mother was taken to the penitentiary where the prison gates closed behind her for a period of not less than six months and not more than five years.”

Prison Warden Snook added a little color to the story. “Had we had any kind of quarters for women at the penitentiary I should have permitted the mother to have her babe, but we have just one room and in this room are five women. Two of them are diseased…”

The headcount was important. Governor Moses Alexander—better known as the nation’s first practicing Jewish governor than for any ill will toward women—had made the small number of women in prison the point of his vetoing a bill that would have added more room to the penitentiary’s tiny women’s ward. When he used his rubber veto stamp, only three women were in prison. He could not foresee there being any more, so he deemed the facility adequate.

The original story appeared on the 19th, a Saturday. Cue the outrage. The next story came out in the Statesman the following Wednesday, informing readers that Mamie Ross, of Albion had picked up her child—now just one month old, according to the paper—and taken a train back home. The governor had received a little pressure and had the woman released.

It all happened so fast that readers were barely catching up. You may feel a bit behind, too. Why was she arrested in the first place? What kind of cruel judge would sentence a darling young woman to prison when she had a (now) two-week old baby to care for?

Mrs. Ross, in her story, was the innocent victim of a couple of her sons who had just lately strayed from the straight and narrow. Those loving sons brought their Mormon mother some presents. She had no idea from whence they came. Albion likely didn’t have bus service then, but Mamie quickly tossed her progeny under a metaphorical one.

Mamie Ross said, “We had never been in any trouble before, and when the officers asked me if I received the articles, I said I had, for my son and stepson brought them to the house and gave them to me. My husband was not even at home at the time it happened, yet we have both had to pay the penalty for what the boys did. It has been a terrible lesson to them, not only to suffer for what they did, but to see us suffer also, when they knew we were innocent.”

As public support swayed in the direction of Mamie Ross, ripped from her loving home by thugs in uniform, the local sheriff made public the circumstances of her arrest. Her home was a rented shack, 8x14 feet, in which 10 Ross family members lived. Many of them were suffering from a “loathsome” disease.

Law enforcement considered the family a gang of thieves. The sheriff said, “Mrs. Ross knew what was going on. She did her utmost to throw us off the scent when we were hunting for stolen goods. Even the bed on which her two youngest children lay contained a quantity of stolen goods. There were bolts of stolen cloth between the mattress and the springs, and other stolen goods concealed about the bed.”

Mamie, her husband Daniel, and their son, J.D., were each sentenced to six months to five years when they pleaded guilty to receiving a wagonload of goods stolen from a store by Lee Ross, another son, and Orville Duncan, Mamie’s son, from a prior marriage. Duncan and Lee Ross got sentences of from one to 15 years.

The judge in the case, William A. Babcock, of Twin Falls, had asked during her trial if Mamie should be put on parole, given her status as the mother of young children. Cassia County officials insisted that “she was the brains of the crowd and the instigator of the whole affair.”

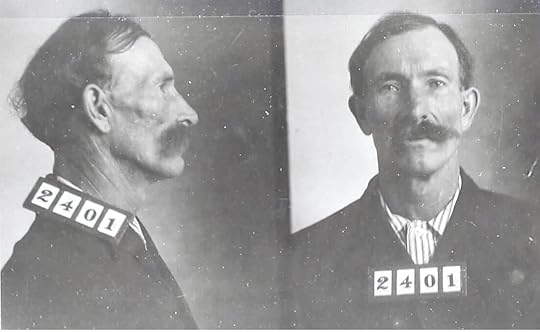

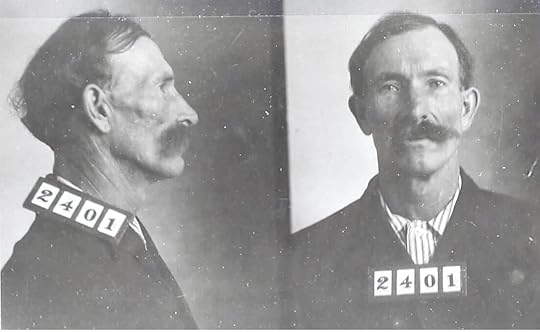

Mamie probably holds Idaho’s record for the shortest prison term. The rest of her family/gang didn’t stay in much longer. Their booking photos, sentences, and release dates are listed below. All were booked on 2-17-1916. Mamie Ross, sentenced to 6 months to five years, was released after 4 days in prison on 2-23-1916 and pardoned on 12-21-1916.

Mamie Ross, sentenced to 6 months to five years, was released after 4 days in prison on 2-23-1916 and pardoned on 12-21-1916.

Daniel Ross, Mamie’s husband, was sentenced to 6 months to five years, paroled on 9-6-1916.

Daniel Ross, Mamie’s husband, was sentenced to 6 months to five years, paroled on 9-6-1916.

Duncan Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and pardoned on 8-1-1917.

Duncan Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and pardoned on 8-1-1917.

Lee Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and paroled on 88-8-1916.

Lee Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and paroled on 88-8-1916.

J.D. Ross, son of Daniel and stepson of Mamie, was sentenced to 6 months to 5 years and paroled on 9-6-1916.

J.D. Ross, son of Daniel and stepson of Mamie, was sentenced to 6 months to 5 years and paroled on 9-6-1916.

On a cold February day in 1916, subscribers to the Idaho Statesman woke up to a chilling image. The headline read, “MOTHER PARTS FROM BABE AT PRISON GATE.”

The stacked headlines, common in the day, told the worst of the story:

“Leaves Infant at Children’s Home While She Serves in Penitentiary”

“NO PRISON ACCOMMODATION”

Then, the zinger:

“Governor Vetoed Appropriation to Provide

Addition Women’s Ward.”

If you didn’t have the gist after four headlines, the article started with, “A pathetic scene was enacted at the Childrens’ Home Funding Society Friday afternoon when a sobbing little woman parted with her two-months-old babe, leaving the infant in the dainty basinet (sic) in the nursery of the Childrens’ home, while the mother was taken to the penitentiary where the prison gates closed behind her for a period of not less than six months and not more than five years.”

Prison Warden Snook added a little color to the story. “Had we had any kind of quarters for women at the penitentiary I should have permitted the mother to have her babe, but we have just one room and in this room are five women. Two of them are diseased…”

The headcount was important. Governor Moses Alexander—better known as the nation’s first practicing Jewish governor than for any ill will toward women—had made the small number of women in prison the point of his vetoing a bill that would have added more room to the penitentiary’s tiny women’s ward. When he used his rubber veto stamp, only three women were in prison. He could not foresee there being any more, so he deemed the facility adequate.

The original story appeared on the 19th, a Saturday. Cue the outrage. The next story came out in the Statesman the following Wednesday, informing readers that Mamie Ross, of Albion had picked up her child—now just one month old, according to the paper—and taken a train back home. The governor had received a little pressure and had the woman released.

It all happened so fast that readers were barely catching up. You may feel a bit behind, too. Why was she arrested in the first place? What kind of cruel judge would sentence a darling young woman to prison when she had a (now) two-week old baby to care for?

Mrs. Ross, in her story, was the innocent victim of a couple of her sons who had just lately strayed from the straight and narrow. Those loving sons brought their Mormon mother some presents. She had no idea from whence they came. Albion likely didn’t have bus service then, but Mamie quickly tossed her progeny under a metaphorical one.

Mamie Ross said, “We had never been in any trouble before, and when the officers asked me if I received the articles, I said I had, for my son and stepson brought them to the house and gave them to me. My husband was not even at home at the time it happened, yet we have both had to pay the penalty for what the boys did. It has been a terrible lesson to them, not only to suffer for what they did, but to see us suffer also, when they knew we were innocent.”

As public support swayed in the direction of Mamie Ross, ripped from her loving home by thugs in uniform, the local sheriff made public the circumstances of her arrest. Her home was a rented shack, 8x14 feet, in which 10 Ross family members lived. Many of them were suffering from a “loathsome” disease.

Law enforcement considered the family a gang of thieves. The sheriff said, “Mrs. Ross knew what was going on. She did her utmost to throw us off the scent when we were hunting for stolen goods. Even the bed on which her two youngest children lay contained a quantity of stolen goods. There were bolts of stolen cloth between the mattress and the springs, and other stolen goods concealed about the bed.”

Mamie, her husband Daniel, and their son, J.D., were each sentenced to six months to five years when they pleaded guilty to receiving a wagonload of goods stolen from a store by Lee Ross, another son, and Orville Duncan, Mamie’s son, from a prior marriage. Duncan and Lee Ross got sentences of from one to 15 years.

The judge in the case, William A. Babcock, of Twin Falls, had asked during her trial if Mamie should be put on parole, given her status as the mother of young children. Cassia County officials insisted that “she was the brains of the crowd and the instigator of the whole affair.”

Mamie probably holds Idaho’s record for the shortest prison term. The rest of her family/gang didn’t stay in much longer. Their booking photos, sentences, and release dates are listed below. All were booked on 2-17-1916.

Mamie Ross, sentenced to 6 months to five years, was released after 4 days in prison on 2-23-1916 and pardoned on 12-21-1916.

Mamie Ross, sentenced to 6 months to five years, was released after 4 days in prison on 2-23-1916 and pardoned on 12-21-1916. Daniel Ross, Mamie’s husband, was sentenced to 6 months to five years, paroled on 9-6-1916.

Daniel Ross, Mamie’s husband, was sentenced to 6 months to five years, paroled on 9-6-1916. Duncan Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and pardoned on 8-1-1917.

Duncan Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and pardoned on 8-1-1917. Lee Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and paroled on 88-8-1916.

Lee Ross, son of Daniel and Mamie, was sentenced to 1 to 15 years and paroled on 88-8-1916. J.D. Ross, son of Daniel and stepson of Mamie, was sentenced to 6 months to 5 years and paroled on 9-6-1916.

J.D. Ross, son of Daniel and stepson of Mamie, was sentenced to 6 months to 5 years and paroled on 9-6-1916.

Published on January 18, 2025 04:00

December 31, 2024

Which Register Rock?

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

How much should we trust early paintings of the West? Artists take their license. Even photographers frame their images to show what they want to show.

The question comes up because I recently ran across Fredric Remington’s painting titled Register Rock, a photo of which is shown below. Remington painted many iconic scenes of the West. They captured a sense of place like few other works of art. Yet, this depiction of Register Rock, described as a “twenty-foot-high boulder” in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950 , resembles the actual rock very little.

There are two Register Rocks in Idaho. The one on the Oregon Trail is located near the Snake River and is a part of Massacre Rocks State Park. It has its own interstate exit. The rock is closer to 10 feet high than 20, and it doesn’t look as if it’s aspiring to be a spire, as the one in the painting does. The real rock is a more or less round, featureless boulder, much like a dozen others of its size in the park. It’s also black. The only thing that sets it apart is that someone travelling the Oregon Trail decided to carve their name and a date on its surface, starting a tradition that other travelers followed.

Remington likely sketched the rock and the surrounding scenery and took the sketch back to a studio to paint. It was painted in 1891. The painter was known for his realism, so why doesn’t the rock look like the rock?

Remington may have given it a more dramatic shape for the… drama. Or, maybe this is a painting of the other Register Rock, the one near the Utah border in City of Rocks National Reserve. There pioneers on the California Trail left their names on the rock in axle grease. It looks much more like the rock depicted in the painting, though not decisively so. The coloration is closer.

The names on both rocks have been documented, so it would seem a simple thing to just read a few from the painting and determine which rock Remington was depicting. Au contraire. The writing on the Remington piece is just representative, squiggles that look like names from a distance. Close up, they are still just squiggles.

So which register rock is it, and where do we register a complaint?

How much should we trust early paintings of the West? Artists take their license. Even photographers frame their images to show what they want to show.

The question comes up because I recently ran across Fredric Remington’s painting titled Register Rock, a photo of which is shown below. Remington painted many iconic scenes of the West. They captured a sense of place like few other works of art. Yet, this depiction of Register Rock, described as a “twenty-foot-high boulder” in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950 , resembles the actual rock very little.

There are two Register Rocks in Idaho. The one on the Oregon Trail is located near the Snake River and is a part of Massacre Rocks State Park. It has its own interstate exit. The rock is closer to 10 feet high than 20, and it doesn’t look as if it’s aspiring to be a spire, as the one in the painting does. The real rock is a more or less round, featureless boulder, much like a dozen others of its size in the park. It’s also black. The only thing that sets it apart is that someone travelling the Oregon Trail decided to carve their name and a date on its surface, starting a tradition that other travelers followed.

Remington likely sketched the rock and the surrounding scenery and took the sketch back to a studio to paint. It was painted in 1891. The painter was known for his realism, so why doesn’t the rock look like the rock?

Remington may have given it a more dramatic shape for the… drama. Or, maybe this is a painting of the other Register Rock, the one near the Utah border in City of Rocks National Reserve. There pioneers on the California Trail left their names on the rock in axle grease. It looks much more like the rock depicted in the painting, though not decisively so. The coloration is closer.

The names on both rocks have been documented, so it would seem a simple thing to just read a few from the painting and determine which rock Remington was depicting. Au contraire. The writing on the Remington piece is just representative, squiggles that look like names from a distance. Close up, they are still just squiggles.

So which register rock is it, and where do we register a complaint?

Published on December 31, 2024 04:00

December 30, 2024

Newport and Oldtown

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

You probably know about the Idaho and Washington “sister” cities of Lewiston and Clarkston, separated by the Snake River. But do you know about the Idaho and Washington towns separated by… nothing?

Only the invisible state border separates Newport, Washington and Oldtown, Idaho. Both hug the Pend Oreille River about seven miles west of Priest River, Idaho. Newport got its name because it was selected as a landing site for the first steamboat on the Pend Oreille River. That was in 1890, when the landing and Newport were both in Idaho. A depot agent bought 40 acres in Washington and moved the Newport landing there. Since that became the Newport Landing, the residents of the old Newport in Idaho, began calling their little town Oldtown.

Newport, Washington was incorporated in 1903. Oldtown, Idaho became an officially incorporated town in 1947.

Oldtown, back when it was called (sigh) Newport, had a notorious resident who seemed to value money over morals. His name was William Vane. No one knew where he came from but he arrived in the 1890s. He acquired nearly the entire town of (then) Newport, Idaho in a business transaction that has been termed “questionable.” His life would be marked by a series of back and forth court filings on his way to becoming wealthy.

Vane had a relationship with the Great Northern Railroad that could be called contentious. He often profited from the railroad as a landowner, but also got into a fight with them over the location of a railroad track. He claimed the land on which it lay and underlined that claim by blowing up a railcar on the track with dynamite.

The Great Northern saw its profits leaking away on the line to Spokane because of a series of robberies. The Seattle Daily Times reported that a man arrested for selling stolen goods from one of those robberies had confessed he had purchased them from one William Vane. The prosecutor charged Vane with possession of stolen property. Despite that public charge, Vane decided to sue the Seattle paper for $250,000, charging that they had defamed his character.

Vane posted a $12,000 security bond in the possession of stolen property case, then disappeared. A man came forward to say that Vane had drowned in a boating accident. The Feds didn’t buy that. They did a little looking around and found William Vane posing as an Indian on the Kalispell Reservation. They arrested Vane and brought him back to the Pend Oreille County jail. He didn’t last long there. Jailers found him the next morning on death’s door, thanks to strychnine poisoning. Whether he died from his own hand or was murdered is still a subject of some debate.

William Vane is remembered as a scoundrel, but also a man who was once appointed as Justice of the Peace and the man who established the first hospital in town. The old one.

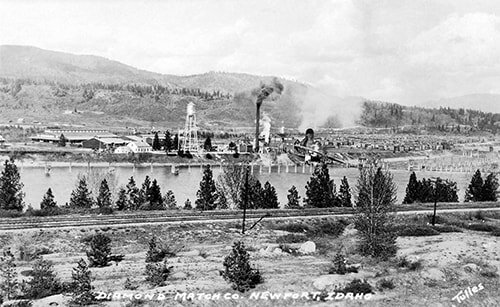

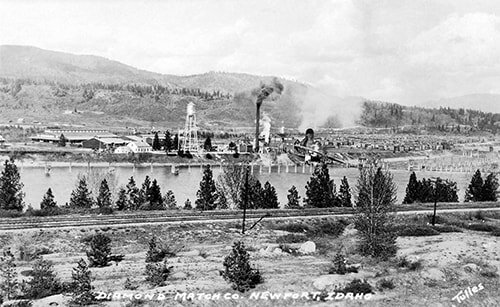

Newport, Idaho was the site of a big Diamond Match Company Mill, which was the reason both water and railroad transportation was needed.

Newport, Idaho was the site of a big Diamond Match Company Mill, which was the reason both water and railroad transportation was needed.

You probably know about the Idaho and Washington “sister” cities of Lewiston and Clarkston, separated by the Snake River. But do you know about the Idaho and Washington towns separated by… nothing?

Only the invisible state border separates Newport, Washington and Oldtown, Idaho. Both hug the Pend Oreille River about seven miles west of Priest River, Idaho. Newport got its name because it was selected as a landing site for the first steamboat on the Pend Oreille River. That was in 1890, when the landing and Newport were both in Idaho. A depot agent bought 40 acres in Washington and moved the Newport landing there. Since that became the Newport Landing, the residents of the old Newport in Idaho, began calling their little town Oldtown.

Newport, Washington was incorporated in 1903. Oldtown, Idaho became an officially incorporated town in 1947.

Oldtown, back when it was called (sigh) Newport, had a notorious resident who seemed to value money over morals. His name was William Vane. No one knew where he came from but he arrived in the 1890s. He acquired nearly the entire town of (then) Newport, Idaho in a business transaction that has been termed “questionable.” His life would be marked by a series of back and forth court filings on his way to becoming wealthy.

Vane had a relationship with the Great Northern Railroad that could be called contentious. He often profited from the railroad as a landowner, but also got into a fight with them over the location of a railroad track. He claimed the land on which it lay and underlined that claim by blowing up a railcar on the track with dynamite.

The Great Northern saw its profits leaking away on the line to Spokane because of a series of robberies. The Seattle Daily Times reported that a man arrested for selling stolen goods from one of those robberies had confessed he had purchased them from one William Vane. The prosecutor charged Vane with possession of stolen property. Despite that public charge, Vane decided to sue the Seattle paper for $250,000, charging that they had defamed his character.

Vane posted a $12,000 security bond in the possession of stolen property case, then disappeared. A man came forward to say that Vane had drowned in a boating accident. The Feds didn’t buy that. They did a little looking around and found William Vane posing as an Indian on the Kalispell Reservation. They arrested Vane and brought him back to the Pend Oreille County jail. He didn’t last long there. Jailers found him the next morning on death’s door, thanks to strychnine poisoning. Whether he died from his own hand or was murdered is still a subject of some debate.

William Vane is remembered as a scoundrel, but also a man who was once appointed as Justice of the Peace and the man who established the first hospital in town. The old one.

Newport, Idaho was the site of a big Diamond Match Company Mill, which was the reason both water and railroad transportation was needed.

Newport, Idaho was the site of a big Diamond Match Company Mill, which was the reason both water and railroad transportation was needed.

Published on December 30, 2024 04:00

December 29, 2024

How Low Can You Go!

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Humans, silly things, love owning something rare. When it comes to license plates, low numbers are in high demand by collectors. The number 1 is particularly sought after. In Massachusetts, low-number plates are in such demand that they hold a lottery for them. The governor of Illinois got in hot water in 2003 for passing out low-numbered plates to political cronies. That who-you-know aspect of low-numbered plates has been common in many jurisdictions, leading to the belief by some that police would tend to let drivers with low-numbered plates slide on minor traffic infractions. Who would want to ruffle the feathers of some VIP?

There could be a little truth to that. Certain VIPs get special plates. Governors in Idaho started getting their own number 1 plates back in 1957.

In 1977, Idaho State Trooper Rich Wills pulled over a car going 61 in a 35-mph construction zone. When he hit the lights, he didn’t notice that the license plate had only the numeral 1 on it. Yes, it was the governor. Governor John Evans wasn’t driving. His press secretary, Steve Leroy, was. Leroy was pushing the speed limit a tad in order to get the governor to a speech on time. Trooper Wills gave Leroy a quick lecture about slowing down and sent the men on their way.

Wills got a little grief in the press over the incident. It hardly ruined his life, though. He spent years with the state police before becoming a state representative.

But, what’s so special about low-numbered plates? The number 1 is no rarer than the number 3315, when it comes to plates. Humans. Silly things.

Humans, silly things, love owning something rare. When it comes to license plates, low numbers are in high demand by collectors. The number 1 is particularly sought after. In Massachusetts, low-number plates are in such demand that they hold a lottery for them. The governor of Illinois got in hot water in 2003 for passing out low-numbered plates to political cronies. That who-you-know aspect of low-numbered plates has been common in many jurisdictions, leading to the belief by some that police would tend to let drivers with low-numbered plates slide on minor traffic infractions. Who would want to ruffle the feathers of some VIP?

There could be a little truth to that. Certain VIPs get special plates. Governors in Idaho started getting their own number 1 plates back in 1957.

In 1977, Idaho State Trooper Rich Wills pulled over a car going 61 in a 35-mph construction zone. When he hit the lights, he didn’t notice that the license plate had only the numeral 1 on it. Yes, it was the governor. Governor John Evans wasn’t driving. His press secretary, Steve Leroy, was. Leroy was pushing the speed limit a tad in order to get the governor to a speech on time. Trooper Wills gave Leroy a quick lecture about slowing down and sent the men on their way.

Wills got a little grief in the press over the incident. It hardly ruined his life, though. He spent years with the state police before becoming a state representative.

But, what’s so special about low-numbered plates? The number 1 is no rarer than the number 3315, when it comes to plates. Humans. Silly things.

Published on December 29, 2024 04:00

December 28, 2024

Quenching your Thirst with Idanha

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

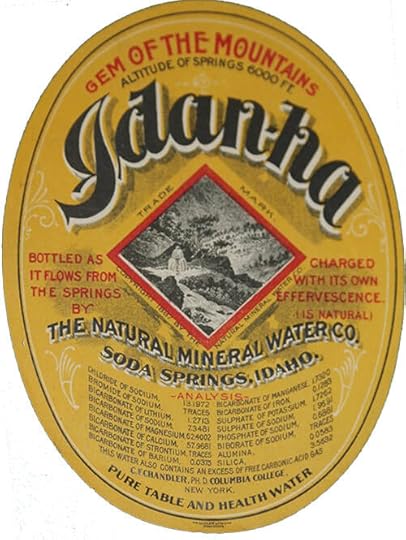

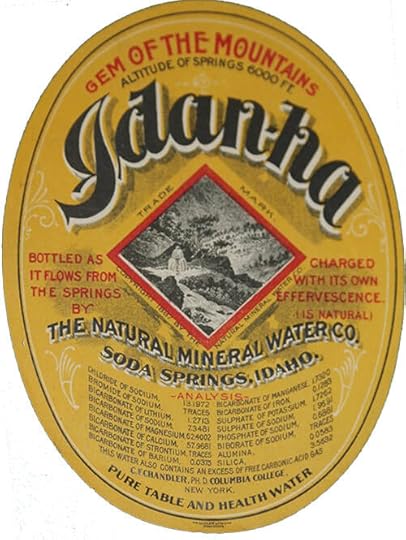

Bottled water is ubiquitous. It’s shipped all over the world and consumed by the billions of gallons by people who usually have a faucet nearby. But before I get off on a rant, I want to say that bottling water and shipping it all over the globe isn’t a new thing. They were doing it in Idaho in 1887.

The Natural Mineral Water Co. incorporated May 17, 1887 was located in Soda Springs, Idaho. They bottled water from Ninety Percent Springs and called it Idanha. Some claim the name is an Indian word meaning something like “spirit of healing waters.” The company would sometimes spell it Idan-Ha. The Idanha Hotel, built by the Union Pacific, came along that same year. That’s the one in Soda Springs. Boise’s Idanha, named after the earlier hotel, came along later.

Idanha water was shipped to eastern markets and foreign countries. It won first prize at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The water is said to have won first place at a World’s Fair in Paris, though the date isn’t certain.

The bottling works burned down in 1895. One might wonder what would burn in a water bottling plant. Nevertheless, it did burn and was rebuilt, getting back to business a couple of years later. The plant filled a million bottles a year in the early days.

Idanha was a great name for a couple of hotels and premium bottled water. It still serves as the name of a town in Oregon. Historians agree that the town name was linked to Idanha water in some way, but no one seems to know how.

But what I want to know about Idanha water is, why ain’t I rich? The National Park Service in interpretive materials about the springs quotes from a diary of one Emma Thompson about the day she and a few friends discovered Ninety Percent Springs. Emma was my great grandmother.

Bottled water is ubiquitous. It’s shipped all over the world and consumed by the billions of gallons by people who usually have a faucet nearby. But before I get off on a rant, I want to say that bottling water and shipping it all over the globe isn’t a new thing. They were doing it in Idaho in 1887.

The Natural Mineral Water Co. incorporated May 17, 1887 was located in Soda Springs, Idaho. They bottled water from Ninety Percent Springs and called it Idanha. Some claim the name is an Indian word meaning something like “spirit of healing waters.” The company would sometimes spell it Idan-Ha. The Idanha Hotel, built by the Union Pacific, came along that same year. That’s the one in Soda Springs. Boise’s Idanha, named after the earlier hotel, came along later.

Idanha water was shipped to eastern markets and foreign countries. It won first prize at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The water is said to have won first place at a World’s Fair in Paris, though the date isn’t certain.

The bottling works burned down in 1895. One might wonder what would burn in a water bottling plant. Nevertheless, it did burn and was rebuilt, getting back to business a couple of years later. The plant filled a million bottles a year in the early days.

Idanha was a great name for a couple of hotels and premium bottled water. It still serves as the name of a town in Oregon. Historians agree that the town name was linked to Idanha water in some way, but no one seems to know how.

But what I want to know about Idanha water is, why ain’t I rich? The National Park Service in interpretive materials about the springs quotes from a diary of one Emma Thompson about the day she and a few friends discovered Ninety Percent Springs. Emma was my great grandmother.

Published on December 28, 2024 04:00

December 27, 2024

The Story of Fort Hall began in Ice

In the early 1800s, a man named Fredric Tudor got the bright idea that one could cut ice from a lake in the winter and store it in an insulated shelter to make it available for sale in the summer. The Boston man eventually made his fortune with that idea, even sending ice by ship to the West Indies.

Another man from the Boston area started a business sawing and selling ice about the same time. He was an iceman in Cambridge in the early 1830s, and he was an iceman in Cambridge in 1836. In the intervening years he was decidedly not an iceman and decidedly not in Cambridge. He ran a store in Idaho, before Idaho was even a territory.

Nathaniel Wyeth had getting rich off the fur trade in mind. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company had started holding rendezvous, mostly in what would become Wyoming. A rendezvous was where trappers brought their season’s worth of furs to trade for supplies and sell for cash.

Wyeth got on the supply side of the equation. On April 28, 1834, he left Independence, Missouri with a loaded pack train of 250 horses, and 75 men headed for Ham’s Fork in the Green River country. A couple of naturalists and Methodist minister Jason Lee went along for the ride.

Wyeth must have felt pretty good about his chances of making a little coin, since he had a contract with the American Fur Company. What he didn’t count on was that the man who had been supplying the rendezvous since the beginning, William Sublette, had no intention of quitting the business. When Sublette found that Wyeth—and Sublette’s brother, Milton—were headed west with supplies, Bill Sublette threw together his own supply train and set out to beat the Wyeth train to the rendezvous.

If Wyeth had known he was in a race, he might have won it. As it was, Bill Sublette beat the Wyeth pack train to the rendezvous of 1834 and convinced Rocky Mountain representatives to let him supply the rendezvous, again, in spite of Wyeth’s contract.

Wyeth was livid. He wasn’t about to turn tail and head back east and sell everything for a loss, so he pushed on west and built a fort near where the Portneuf River dumps into the Snake. He named it Fort Hall after Henry Hall, one of his investors.

The Hudson Bay Company, a rival of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, saw the construction of Fort Hall as a threat and immediately put up their own supply post, Fort Boise, where the Boise River enters the Snake.

There was suddenly a glut of supplies for trappers. Seeing that fortune was not in his future at the fort, Wyeth sold out to the Hudson Bay Company in 1836 and went back to cutting ice in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Another man from the Boston area started a business sawing and selling ice about the same time. He was an iceman in Cambridge in the early 1830s, and he was an iceman in Cambridge in 1836. In the intervening years he was decidedly not an iceman and decidedly not in Cambridge. He ran a store in Idaho, before Idaho was even a territory.

Nathaniel Wyeth had getting rich off the fur trade in mind. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company had started holding rendezvous, mostly in what would become Wyoming. A rendezvous was where trappers brought their season’s worth of furs to trade for supplies and sell for cash.

Wyeth got on the supply side of the equation. On April 28, 1834, he left Independence, Missouri with a loaded pack train of 250 horses, and 75 men headed for Ham’s Fork in the Green River country. A couple of naturalists and Methodist minister Jason Lee went along for the ride.

Wyeth must have felt pretty good about his chances of making a little coin, since he had a contract with the American Fur Company. What he didn’t count on was that the man who had been supplying the rendezvous since the beginning, William Sublette, had no intention of quitting the business. When Sublette found that Wyeth—and Sublette’s brother, Milton—were headed west with supplies, Bill Sublette threw together his own supply train and set out to beat the Wyeth train to the rendezvous.

If Wyeth had known he was in a race, he might have won it. As it was, Bill Sublette beat the Wyeth pack train to the rendezvous of 1834 and convinced Rocky Mountain representatives to let him supply the rendezvous, again, in spite of Wyeth’s contract.

Wyeth was livid. He wasn’t about to turn tail and head back east and sell everything for a loss, so he pushed on west and built a fort near where the Portneuf River dumps into the Snake. He named it Fort Hall after Henry Hall, one of his investors.

The Hudson Bay Company, a rival of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, saw the construction of Fort Hall as a threat and immediately put up their own supply post, Fort Boise, where the Boise River enters the Snake.

There was suddenly a glut of supplies for trappers. Seeing that fortune was not in his future at the fort, Wyeth sold out to the Hudson Bay Company in 1836 and went back to cutting ice in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Published on December 27, 2024 04:00

December 26, 2024

A Circus Story with a Warning

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

I often stagger down the halls of history, careening off the walls and sometimes stumbling into a cobweb-filled room that has been long forgotten. Such was the case recently when I tried to match up a cool photo of a circus parade in Blackfoot with a story from contemporaneous newspapers. It turned out there wasn’t much more to say about the Blackfoot photo, but searching for the circus name turned up a story from Twin Falls that is graphic enough for me to warn those who might have delicate constitutions to turn back. Now.

On May 26, 1907 the Sells-Floto Circus set up tents in Twin Falls. They advertised “100 startling, superb, sensational and stupendous surprises.” The number of surprises might have been off a bit, but surprises there were.

The circus had some headliners named Markel and Agnes, a pair of tigers. Handlers were in the process of feeding the big cats when Markel began to beat furiously against the cage door with his front paws. The door gave way and the tiger leapt on the nearest thing that looked like food, a Shetland pony, and began tearing at its neck. The tiger keeper whacked Markel between the eyes with an iron bar. The cat jumped off the little horse and onto the back of a second Shetland. The keeper tried the trick with the bar again, causing the tiger to repeat his retreat, only to leap onto the back of a third pony. A third whack to the face with an iron bar drove the tiger off the Shetland and into the crowd, perhaps not the result the keeper was hoping for.

As the news service story stated, “A panic followed. Women grasped their children and dragged them from the path of the maddened animal.

“The screams of the frightened spectators mingled with the trumpeting of the elephants and the cries of excited animals in the cages.”

Mrs. S. E. Rosell tried to pull her four-year-old daughter Ruth out of the way, to no avail. The cat knocked them down. “Holding the mother with his paws the tiger sank his teeth in the neck of the child.”

Local blacksmith J.W. Bell pushed his own family aside then aimed his .32 caliber revolver at the tiger from three feet away. The big cat took six bullets before finally collapsing.

Sadly, Ruth Rosell died from her wounds a couple of hours later.

Devastating as the experience must have been, the circus—the same circus—was back in Twin Falls for another show the following year. You’ve heard the saying, “The show must go on,” right?

I often stagger down the halls of history, careening off the walls and sometimes stumbling into a cobweb-filled room that has been long forgotten. Such was the case recently when I tried to match up a cool photo of a circus parade in Blackfoot with a story from contemporaneous newspapers. It turned out there wasn’t much more to say about the Blackfoot photo, but searching for the circus name turned up a story from Twin Falls that is graphic enough for me to warn those who might have delicate constitutions to turn back. Now.

On May 26, 1907 the Sells-Floto Circus set up tents in Twin Falls. They advertised “100 startling, superb, sensational and stupendous surprises.” The number of surprises might have been off a bit, but surprises there were.

The circus had some headliners named Markel and Agnes, a pair of tigers. Handlers were in the process of feeding the big cats when Markel began to beat furiously against the cage door with his front paws. The door gave way and the tiger leapt on the nearest thing that looked like food, a Shetland pony, and began tearing at its neck. The tiger keeper whacked Markel between the eyes with an iron bar. The cat jumped off the little horse and onto the back of a second Shetland. The keeper tried the trick with the bar again, causing the tiger to repeat his retreat, only to leap onto the back of a third pony. A third whack to the face with an iron bar drove the tiger off the Shetland and into the crowd, perhaps not the result the keeper was hoping for.

As the news service story stated, “A panic followed. Women grasped their children and dragged them from the path of the maddened animal.

“The screams of the frightened spectators mingled with the trumpeting of the elephants and the cries of excited animals in the cages.”

Mrs. S. E. Rosell tried to pull her four-year-old daughter Ruth out of the way, to no avail. The cat knocked them down. “Holding the mother with his paws the tiger sank his teeth in the neck of the child.”

Local blacksmith J.W. Bell pushed his own family aside then aimed his .32 caliber revolver at the tiger from three feet away. The big cat took six bullets before finally collapsing.

Sadly, Ruth Rosell died from her wounds a couple of hours later.

Devastating as the experience must have been, the circus—the same circus—was back in Twin Falls for another show the following year. You’ve heard the saying, “The show must go on,” right?

Published on December 26, 2024 04:00

December 25, 2024

Merry Christmas!

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Here's a little cartoon snapshot from the Idaho Statesman in 1904 for your 2024 Christmas Day.

Here's a little cartoon snapshot from the Idaho Statesman in 1904 for your 2024 Christmas Day.

Published on December 25, 2024 04:00

December 24, 2024

Fifty Years Hence

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

In 1921, the folks at the Idaho Statesman were feeling optimistic. They devoted a page and half to how grand Boise would be “Fifty Years Hence.” The article was full of “Predictions, based on scientific calculations and (the) law of averages.”

We’re more than a hundred years “hence,” so let’s see how well the prognosticators—various leading citizens--did.

Architect J.A. Fennel predicted hourly air service by 1971. That was probably correct. Some of his vision sounds familiar today. “The visitor will observe from his cab window a beautiful residential section festooning the hills, with wonderful winding driveways.” We can only wish his next prediction had come true. “The absence of parked automobiles from the streets will be accounted for by the fact that under-the-street garages or storage spaces have been provided.”

W.H.P. Hill, secretary of the Boise Chamber of Commerce expected 300,000 people to be living in Boise by 1971. It was closer to 75,000. Stay tuned, though. We aren’t far from Hill’s mark today. The chamber exec pointed out that Boise had the first tourist park for automobiles, and that he expected the future to bring an “Aero Tourist park with its perfect landing fields and accommodations for hundreds of flying machines and thousands of passengers.”

J.P. Congdon envisioned flying into Boise and seeing that “Both banks of the river have been very prettily parked and there are miles and miles of good driveways in them. Checks have been placed in the river to provide boating and bathing facilities.” He came the closest to guessing the 1971 population of Boise: 100,000.

Dora Thompson, the supervisor of schools in Boise, expected “well-proportioned business edifices, free from all advertising matter, and elegant in their simplicity of line and decoration.” She also predicted “Noiseless electric trains running without track or third rail.” She envisioned a magical device that would free the air from “noisome odors and flecks of begriming soot, for all the smoke of the city will be consumed in a municipally owned plant operated for that purpose.”

One prediction Ms. Thompson made had a sting it: “Boise will not be true to her name ‘wooded’ 50 years hence, however, if a city forester is not appointed in the near future, since trees are being cut ruthlessly and new ones are not being planted systematically.”

Perhaps the elected officials of the city heeded her call. Today we have a city forester and the nickname City of Trees.

What would you predict “50 years hence?”

In 1921, the folks at the Idaho Statesman were feeling optimistic. They devoted a page and half to how grand Boise would be “Fifty Years Hence.” The article was full of “Predictions, based on scientific calculations and (the) law of averages.”

We’re more than a hundred years “hence,” so let’s see how well the prognosticators—various leading citizens--did.

Architect J.A. Fennel predicted hourly air service by 1971. That was probably correct. Some of his vision sounds familiar today. “The visitor will observe from his cab window a beautiful residential section festooning the hills, with wonderful winding driveways.” We can only wish his next prediction had come true. “The absence of parked automobiles from the streets will be accounted for by the fact that under-the-street garages or storage spaces have been provided.”

W.H.P. Hill, secretary of the Boise Chamber of Commerce expected 300,000 people to be living in Boise by 1971. It was closer to 75,000. Stay tuned, though. We aren’t far from Hill’s mark today. The chamber exec pointed out that Boise had the first tourist park for automobiles, and that he expected the future to bring an “Aero Tourist park with its perfect landing fields and accommodations for hundreds of flying machines and thousands of passengers.”

J.P. Congdon envisioned flying into Boise and seeing that “Both banks of the river have been very prettily parked and there are miles and miles of good driveways in them. Checks have been placed in the river to provide boating and bathing facilities.” He came the closest to guessing the 1971 population of Boise: 100,000.

Dora Thompson, the supervisor of schools in Boise, expected “well-proportioned business edifices, free from all advertising matter, and elegant in their simplicity of line and decoration.” She also predicted “Noiseless electric trains running without track or third rail.” She envisioned a magical device that would free the air from “noisome odors and flecks of begriming soot, for all the smoke of the city will be consumed in a municipally owned plant operated for that purpose.”

One prediction Ms. Thompson made had a sting it: “Boise will not be true to her name ‘wooded’ 50 years hence, however, if a city forester is not appointed in the near future, since trees are being cut ruthlessly and new ones are not being planted systematically.”

Perhaps the elected officials of the city heeded her call. Today we have a city forester and the nickname City of Trees.

What would you predict “50 years hence?”

Published on December 24, 2024 04:00

December 23, 2024

A Distaff Dentist

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

The August 27, 1892 edition of the Idaho Statesman had a note about the first female dentist in the world. Henrietta Hirschfeldt was said to have graduated in 1869 from Pennsylvania College. This was apparently as common as roller skates on a goose, thus worthy of the mention.

When, in 1906, Boise was under threat of having its own distaff dentist, the Statesman felt it necessary to assure readers that Carrie Berthaumm, DDS, was probably physically capable of extracting a tooth. “She is a well built woman of—well, probably 20 or over, and appears eminently capable of handling any refractory molars that she might encounter without calling in the assistance of the janitor of her building, or using a block and tackle.”

That snide remark aside, Berthaumm did practice dentistry in Boise for many years with little further notice from the local paper, save for the weekly ads she purchased announcing her practice.

As if the sarcastic reporter who announced the beginning of her practice were prescient, Dr. Berthaumm did employ a janitor. He made the news because of dentistry, though not for helping her pull teeth. In June 1917, the janitor discovered that Berthaumm’s office had been broken into. Nothing seemed to be missing, but the culprit had left something behind. The janitor found a good-sized piece of gold on the floor. Knowing that Berthaumm did not handle gold filings, he took the little treasure to her colleague, Dr. Cohn, who discovered his desk drawer had been jimmied and the gold within stolen. All the dental offices in town had been hit over the weekend by the sloppy burglar, who took what gold he or she could find but left the costlier platinum behind.

The August 27, 1892 edition of the Idaho Statesman had a note about the first female dentist in the world. Henrietta Hirschfeldt was said to have graduated in 1869 from Pennsylvania College. This was apparently as common as roller skates on a goose, thus worthy of the mention.

When, in 1906, Boise was under threat of having its own distaff dentist, the Statesman felt it necessary to assure readers that Carrie Berthaumm, DDS, was probably physically capable of extracting a tooth. “She is a well built woman of—well, probably 20 or over, and appears eminently capable of handling any refractory molars that she might encounter without calling in the assistance of the janitor of her building, or using a block and tackle.”

That snide remark aside, Berthaumm did practice dentistry in Boise for many years with little further notice from the local paper, save for the weekly ads she purchased announcing her practice.

As if the sarcastic reporter who announced the beginning of her practice were prescient, Dr. Berthaumm did employ a janitor. He made the news because of dentistry, though not for helping her pull teeth. In June 1917, the janitor discovered that Berthaumm’s office had been broken into. Nothing seemed to be missing, but the culprit had left something behind. The janitor found a good-sized piece of gold on the floor. Knowing that Berthaumm did not handle gold filings, he took the little treasure to her colleague, Dr. Cohn, who discovered his desk drawer had been jimmied and the gold within stolen. All the dental offices in town had been hit over the weekend by the sloppy burglar, who took what gold he or she could find but left the costlier platinum behind.

Published on December 23, 2024 04:00