Rick Just's Blog

August 23, 2025

SMOKE GETS IN YOUR EYES: Fire Lookouts in Idaho

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page once or twice a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.

Bertha Hill, 30 miles northeast of Orofino, was named by some college boys working for the Clearwater Timber Protective Association. The rounded mountain reminded them of a girl they knew in Moscow in the way the Tetons reminded French trappers of women they knew.

The hill might better be named Mable Mountain and not for a sophomoric anatomical joke. Mable Gray spent many hours on that mountain in 1902, sitting on a tree limb looking for smoke. For her vigilance, Gray is remembered as the first fire lookout working strictly to protect a forest in the Western states.

Mable Gray's days started early, with her making breakfast for the timber camp and cleaning up the dishes. If thunderstorms had rolled in overnight, Mable cleaned up quickly, hopped on a pony, and rode to the top of Bertha Mountain. It wasn't enough for her just to stand there gazing out over the million-acre Clearwater-Potlatch private forest looking for smoke. She'd tie up her horse and climb a crude ladder—two rough-cut poles with severed limbs nailed on them—to the beckoning branch of a hemlock snag 12 or 15 feet up. She sat in a makeshift seat on that limb for hours, protecting the company's investment. If she spotted smoke, Mable scrambled down the ladder and back onto the horse to alert the crew to the fire.

Mable Gray got a little help the first time she climbed the snag where she perched on top of Bertha Hill. Courtesy of the University of Idaho Potlatch Lumber Company Digital Collection.

Mable Gray got a little help the first time she climbed the snag where she perched on top of Bertha Hill. Courtesy of the University of Idaho Potlatch Lumber Company Digital Collection. Mable's perch in that tree is long gone today, but there's a fire lookout on Bertha Mountain, one of about 177 still operated in Idaho today. Close to a thousand lookouts have dotted the state since that first crude perch. Most were eventually abandoned, aerial and satellite imagery largely taking the place of on-the-ground spotters.

The Forest Service, founded in 1905, saw the wisdom of fire spotters early on. If a crew could reach a fire while it was still small, they stood a better chance of putting it out. The Forest Service unofficial firefighting motto became "Spot Em Quick, and hit Em Fast."

Just spotting a fire wasn't enough. A spotter needed to provide an accurate location to send crews. So William Osborne, a Forest Service employee, invented the Osborne Firefinder in 1915. It's a circular table overlaid with a topographic map of the area fitted with moveable sights an operator looks through to pinpoint smoke. A spotter lines up the sights to get a horizontal reading in degrees and minutes and uses an attached tape to estimate the miles between the smoke and the lookout. You couldn't use a sophisticated instrument like that while sitting in the crook of a tree as Mable Gray did. Lookout towers grew more complex and substantial as years went by.

The view from inside the Deadwood Lookout near Garden Valley.

The view from inside the Deadwood Lookout near Garden Valley.  There’s no need for a tower at the Deadwood Lookout near Garden Valley.

There’s no need for a tower at the Deadwood Lookout near Garden Valley.

In 1929 the Forest Service began using a design called the L-2, first implemented on Lookout Mountain above Priest Lake's Cavanaugh Bay. The standardized model was a 12-by-14-foot building complete with framed glass. There was a sleeping and living area on the first floor. The spotter who worked in a lookout did their fire spotting from a cupola above. These structures cost only $500 to build. The L-2s started popping up on mountains and on metal towers all over the West. Some 5,000 lookouts of various designs were active in their day.

Spending days alone in a tall, windowed contraption with a 360-degree view of nature seems like a dream job for writers. So thought Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Norman Maclean, and Edward Abbey, all of whom served as fire spotters.

If a bit of solitude appeals to the writer in you, check with the Forest Service to find out what spotter jobs are available. Or try it for a weekend. You can rent some old lookouts in Idaho. Stay in the tower at the self-referential Lookout Butte Lookout near Riggins for $40 a night. If mountaintops appeal to you, but you'd rather not perch on those spindly legs, try the Deadwood Lookout recreational cabin near Garden Valley, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1934. That will run you about $55 a night. Release your inner Mable Gray and find a rental at recreation.gov.

The Blue Point Lookout Station on Rice Peak in the Payette National Forest, near Cascade. The photo was taken in 1920. Courtesy of the University of Idaho Potlatch Lumber Company Digital Collection.

The Blue Point Lookout Station on Rice Peak in the Payette National Forest, near Cascade. The photo was taken in 1920. Courtesy of the University of Idaho Potlatch Lumber Company Digital Collection.

Published on August 23, 2025 13:26

August 4, 2025

Blackfoot River Petroglyphs

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page once or twice a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.

Grab a cup of something. This is a long one.

I grew up along the Blackfoot River in Eastern Idaho, not far from the town of Blackfoot. Given the name of the river and town, one might think Blackfeet Indians played a key role in the history of the area. They did not.

Shoshone or Bannock Indians left behind the “Indian writing” a couple of miles from our house, which I grew up hearing about. The river leaves the deep canyon it cut and meanders along for a few miles between the mountains on the south and Presto Bench on the north. That secluded valley was a wintering spot for the tribes and, in 1870, a homesteading spot for the Just family.

I explored the lava rocks on which someone had drawn strange symbols centuries before, many times in the summers of my youth. Along the upper edge of the cliffs, you could see redoubts, rocks piled to hide behind and imagine what native men were hiding from.

I heard only vague stories about the possible meaning of the rock writing. One was that scientists from the Smithsonian had come to document the petroglyphs in the 1920s.

That story, as it turns out, was a bit inflated. John E. Rees studied the petroglyphs along the river in 1926. He sent that study to the Smithsonian.

Rees was an attorney, a high school teacher, a state senator, a “professor,” and a fanatic about history, especially as it pertained to Indians. He wrote several papers digging deeply into indigenous languages, pulling definitions together in defensible, if tortured, ways to explain the etymology of place names in the West. Perhaps his most famous explanation was how Idaho got its name, attributing it to the Shoshone words “eh” (coming down), “dah” (sun, root, or mountain), and “how” (the equivalent of an exclamation mark).

The Rees interpretation was widely accepted for years, but research by Idaho’s most esteemed historian, Dr. Merle Wells, proved it wrong in about 1958 (see story below).

It was that same John Rees who visited “my” rocks along the Blackfoot River in 1926 and attempted an interpretation of the petroglyphs based on his conversations with a Shoshone tribal member who was an artist.

There are many rocks with rock art on them on my cousin’s property in the valley where I grew up. They may have once been close to the river. If so, the river has meandered about a half mile to the south since then. But it was one rock in particular that made the news in 1926.

The Idaho Statesman, displaying little sensitivity to ethnic slurs at the time, led off with this boxed headline: “John E. Rees, Authority on Folk Lore of the Redskins, Explains Picture Writing Found on Rock on Bank of Blackfoot River.”

Susie Trego, the wife of Blackfoot’s Idaho Republican newspaper publisher, was credited with “finding” the rock. Doubtful. It’s more likely my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, showed it to her. Reid was a long-time columnist for Blackfoot papers and a friend of the Tregos. She lived near the rock for all of her 90 years.

Trego claimed the 875-pound rock and moved it to her mansion in Blackfoot, Sagehurst. Thanks to the efforts of my cousin, Marlene Stibal Reid, it would be returned to the Blackfoot River Valley 69 years later. Someone blew the math in the photo caption below. But I digress. You need to know what was scratched onto the rock. It was, after all, “the story of one of the first great peace conferences ever held on the American continent,” according to the Idaho Statesman. According to “Professor” John Rees.

But I digress. You need to know what was scratched onto the rock. It was, after all, “the story of one of the first great peace conferences ever held on the American continent,” according to the Idaho Statesman. According to “Professor” John Rees.

The title Rees often used is in quotes because he was never a college professor and did not have a degree in history, as one might assume. “Professor” was a fairly common colloquial title of respect in the early part of the Twentieth Century. He taught history and science in Salmon and was well-respected by historians at the time.

Rees also ran the Indian trading post at the Lemhi Agency near Salmon for 17 years. There he vigorously studied native languages and the symbols of petroglyphs—images carved into the surface of a rock—and pictographs—images painted on a rock with natural pigments.

The remarkable rock “borrowed” by Susie Trego told a story. John Rees retold it in excruciating detail using the photo below and describing each symbol by its corresponding number.

In the Rees interpretation, the rock was an invitation to a meeting to divide hunting rights between tribes in what is now Idaho and Wyoming. Those stumbling upon the rock were to pass along the complicated message so the chiefs could meet, according to Rees.

In the Rees interpretation, the rock was an invitation to a meeting to divide hunting rights between tribes in what is now Idaho and Wyoming. Those stumbling upon the rock were to pass along the complicated message so the chiefs could meet, according to Rees.

There are some holes in the interpretation. First, why bother spending hours scratching this on a rock in the first place when you could simply assign a runner to get the word from one tribe to another? Second, although there was some commonality in the symbols, their interpretation probably wouldn’t survive precisely for a thousand years in a game of “telephone” passed through the centuries. Third, what good was an invitation without some way of knowing what date, or year, or even season, the invitation was for?

To give you a taste of a Rees explanation of rock writing without making you slog through pages, I include a few lines from a description of the following plate depicting symbols at the Blackfoot River site. It appeared initially in the 1923-24 Biennial Report of the Idaho State Historical Society.

“Fig. 1, represents the 'rising sun,' so denoted by the rays shooting from it. To an Indian every object in nature is endowed with a spirit, the source of which is the sun. His own spirit coming from a spirit eventually will return to it. This orb, then, is the sun, father of the Indians. The sun-father made two brothers, the wolf and the coyote, who lived in a cave near a spring that came from solid rock. The coyote went to live with a fair young girl and from their union came the Shoshonis and Bannacks. This is the 'coyote cult, and is represented in Fig. 2.”

“Fig. 1, represents the 'rising sun,' so denoted by the rays shooting from it. To an Indian every object in nature is endowed with a spirit, the source of which is the sun. His own spirit coming from a spirit eventually will return to it. This orb, then, is the sun, father of the Indians. The sun-father made two brothers, the wolf and the coyote, who lived in a cave near a spring that came from solid rock. The coyote went to live with a fair young girl and from their union came the Shoshonis and Bannacks. This is the 'coyote cult, and is represented in Fig. 2.”

The air of authority in the writing of John Rees and the certainty he exhibits is what originally cast doubt on his work for me. Archaeologists today are hesitant to assign meaning to such symbols.

I wouldn’t argue that the first figure might be the sun and the second a coyote. As the figures become more abstract and less representational, my confidence in the Rees interpretations wanes.

Even so, I have a favorite. I’ve always been drawn to the coyote because of its simple, nearly Picasso-esque lines. One line, the tiny one emanating from the creature’s mouth, has always fascinated me. It’s clearly (yes, I’m making the same leap as Rees often does) barking or howling.

A “sound line” such as that is common in cartoons today. The technical term for it is emanata. I was surprised and delighted to see it in ancient artwork.

I’m grateful to John Rees for recording the rock art from my home valley for posterity, even though he was complicit in moving the “gathering stone” from its original site. But, I do have one more complaint that I must pass on. Rees went over the rock art with some kind of whitewash for the purpose of making the art stand out in photographs. Another method often used is to go over the lines with chalk. This was a common practice in his day, so I can’t much fault Rees for it, but I must point out that archeologists today vehemently discourage that. It can degrade the petroglyphs and pictographs. It also captures only what the photographer saw, and not what might actually be there on closer examination.

And with that, I’ll quit picking on Mr. Rees, who, despite his over-eager interpretation, is guilty mostly of trying to understand the world around him. We’re all guilty of that.

One of the photos John Rees took of the Blackfoot River rock art. Not that the art has been “chalked.” What story do you think it tells?

One of the photos John Rees took of the Blackfoot River rock art. Not that the art has been “chalked.” What story do you think it tells?

Grab a cup of something. This is a long one.

I grew up along the Blackfoot River in Eastern Idaho, not far from the town of Blackfoot. Given the name of the river and town, one might think Blackfeet Indians played a key role in the history of the area. They did not.

Shoshone or Bannock Indians left behind the “Indian writing” a couple of miles from our house, which I grew up hearing about. The river leaves the deep canyon it cut and meanders along for a few miles between the mountains on the south and Presto Bench on the north. That secluded valley was a wintering spot for the tribes and, in 1870, a homesteading spot for the Just family.

I explored the lava rocks on which someone had drawn strange symbols centuries before, many times in the summers of my youth. Along the upper edge of the cliffs, you could see redoubts, rocks piled to hide behind and imagine what native men were hiding from.

I heard only vague stories about the possible meaning of the rock writing. One was that scientists from the Smithsonian had come to document the petroglyphs in the 1920s.

That story, as it turns out, was a bit inflated. John E. Rees studied the petroglyphs along the river in 1926. He sent that study to the Smithsonian.

Rees was an attorney, a high school teacher, a state senator, a “professor,” and a fanatic about history, especially as it pertained to Indians. He wrote several papers digging deeply into indigenous languages, pulling definitions together in defensible, if tortured, ways to explain the etymology of place names in the West. Perhaps his most famous explanation was how Idaho got its name, attributing it to the Shoshone words “eh” (coming down), “dah” (sun, root, or mountain), and “how” (the equivalent of an exclamation mark).

The Rees interpretation was widely accepted for years, but research by Idaho’s most esteemed historian, Dr. Merle Wells, proved it wrong in about 1958 (see story below).

It was that same John Rees who visited “my” rocks along the Blackfoot River in 1926 and attempted an interpretation of the petroglyphs based on his conversations with a Shoshone tribal member who was an artist.

There are many rocks with rock art on them on my cousin’s property in the valley where I grew up. They may have once been close to the river. If so, the river has meandered about a half mile to the south since then. But it was one rock in particular that made the news in 1926.

The Idaho Statesman, displaying little sensitivity to ethnic slurs at the time, led off with this boxed headline: “John E. Rees, Authority on Folk Lore of the Redskins, Explains Picture Writing Found on Rock on Bank of Blackfoot River.”

Susie Trego, the wife of Blackfoot’s Idaho Republican newspaper publisher, was credited with “finding” the rock. Doubtful. It’s more likely my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, showed it to her. Reid was a long-time columnist for Blackfoot papers and a friend of the Tregos. She lived near the rock for all of her 90 years.

Trego claimed the 875-pound rock and moved it to her mansion in Blackfoot, Sagehurst. Thanks to the efforts of my cousin, Marlene Stibal Reid, it would be returned to the Blackfoot River Valley 69 years later. Someone blew the math in the photo caption below.

But I digress. You need to know what was scratched onto the rock. It was, after all, “the story of one of the first great peace conferences ever held on the American continent,” according to the Idaho Statesman. According to “Professor” John Rees.

But I digress. You need to know what was scratched onto the rock. It was, after all, “the story of one of the first great peace conferences ever held on the American continent,” according to the Idaho Statesman. According to “Professor” John Rees.The title Rees often used is in quotes because he was never a college professor and did not have a degree in history, as one might assume. “Professor” was a fairly common colloquial title of respect in the early part of the Twentieth Century. He taught history and science in Salmon and was well-respected by historians at the time.

Rees also ran the Indian trading post at the Lemhi Agency near Salmon for 17 years. There he vigorously studied native languages and the symbols of petroglyphs—images carved into the surface of a rock—and pictographs—images painted on a rock with natural pigments.

The remarkable rock “borrowed” by Susie Trego told a story. John Rees retold it in excruciating detail using the photo below and describing each symbol by its corresponding number.

In the Rees interpretation, the rock was an invitation to a meeting to divide hunting rights between tribes in what is now Idaho and Wyoming. Those stumbling upon the rock were to pass along the complicated message so the chiefs could meet, according to Rees.

In the Rees interpretation, the rock was an invitation to a meeting to divide hunting rights between tribes in what is now Idaho and Wyoming. Those stumbling upon the rock were to pass along the complicated message so the chiefs could meet, according to Rees.There are some holes in the interpretation. First, why bother spending hours scratching this on a rock in the first place when you could simply assign a runner to get the word from one tribe to another? Second, although there was some commonality in the symbols, their interpretation probably wouldn’t survive precisely for a thousand years in a game of “telephone” passed through the centuries. Third, what good was an invitation without some way of knowing what date, or year, or even season, the invitation was for?

To give you a taste of a Rees explanation of rock writing without making you slog through pages, I include a few lines from a description of the following plate depicting symbols at the Blackfoot River site. It appeared initially in the 1923-24 Biennial Report of the Idaho State Historical Society.

“Fig. 1, represents the 'rising sun,' so denoted by the rays shooting from it. To an Indian every object in nature is endowed with a spirit, the source of which is the sun. His own spirit coming from a spirit eventually will return to it. This orb, then, is the sun, father of the Indians. The sun-father made two brothers, the wolf and the coyote, who lived in a cave near a spring that came from solid rock. The coyote went to live with a fair young girl and from their union came the Shoshonis and Bannacks. This is the 'coyote cult, and is represented in Fig. 2.”

“Fig. 1, represents the 'rising sun,' so denoted by the rays shooting from it. To an Indian every object in nature is endowed with a spirit, the source of which is the sun. His own spirit coming from a spirit eventually will return to it. This orb, then, is the sun, father of the Indians. The sun-father made two brothers, the wolf and the coyote, who lived in a cave near a spring that came from solid rock. The coyote went to live with a fair young girl and from their union came the Shoshonis and Bannacks. This is the 'coyote cult, and is represented in Fig. 2.”The air of authority in the writing of John Rees and the certainty he exhibits is what originally cast doubt on his work for me. Archaeologists today are hesitant to assign meaning to such symbols.

I wouldn’t argue that the first figure might be the sun and the second a coyote. As the figures become more abstract and less representational, my confidence in the Rees interpretations wanes.

Even so, I have a favorite. I’ve always been drawn to the coyote because of its simple, nearly Picasso-esque lines. One line, the tiny one emanating from the creature’s mouth, has always fascinated me. It’s clearly (yes, I’m making the same leap as Rees often does) barking or howling.

A “sound line” such as that is common in cartoons today. The technical term for it is emanata. I was surprised and delighted to see it in ancient artwork.

I’m grateful to John Rees for recording the rock art from my home valley for posterity, even though he was complicit in moving the “gathering stone” from its original site. But, I do have one more complaint that I must pass on. Rees went over the rock art with some kind of whitewash for the purpose of making the art stand out in photographs. Another method often used is to go over the lines with chalk. This was a common practice in his day, so I can’t much fault Rees for it, but I must point out that archeologists today vehemently discourage that. It can degrade the petroglyphs and pictographs. It also captures only what the photographer saw, and not what might actually be there on closer examination.

And with that, I’ll quit picking on Mr. Rees, who, despite his over-eager interpretation, is guilty mostly of trying to understand the world around him. We’re all guilty of that.

One of the photos John Rees took of the Blackfoot River rock art. Not that the art has been “chalked.” What story do you think it tells?

One of the photos John Rees took of the Blackfoot River rock art. Not that the art has been “chalked.” What story do you think it tells?

Published on August 04, 2025 07:14

July 12, 2025

Why Boise Once Had Five Airports

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page once or twice a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.

World War II created somewhere near 500,000 pilots. After the war, many of them wanted to continue flying. The war created pilots in another way, too. GIs returning from combat found that they could use money from the GI Bill to train for future careers. With all that training money, hundreds of flight schools popped up around the country.

Prognosticators following the war predicted that airplanes would be as cheap as automobiles and nearly as common. They envisioned airplane communities where you would roll your plane out of its garage in the morning and take off for work from an adjacent community airstrip.

Commercial aviation boomed, too. The war had turned aviation into the largest manufacturing industry in the world.

In a sense, private aviation and commercial aviation were in a race for the hearts of the American people. Commercial aviation won. Airplane ownership proved too costly for the average household. Meanwhile, commercial travel got cheaper and more accessible.

That’s a little background on why Boise had five airports at one time, but today, gets along with only three in the entire Treasure Valley: the Boise Airport (BOI), the Nampa Municipal Airport, and the Caldwell Industrial Airport. If you count Emmett as part of the Treasure Valley, they have a small municipal airport there, too.

The Boise Airport

The history of the Boise Airport is fairly well known, so I won’t spend a lot of time on that. Suffice to say that the original airport, named Booth Field but rarely called that, was built next to the Boise River, where Boise State University is today. The property was purchased from William T. Booth in 1926 and quickly readied for service.

Passenger service was far in the future, and nearly no one knew how to fly. So, why did Boise need a municipal airport? Air mail. Boise was part of the first commercial air mail route, which included stops in Elko, Nevada, and Pasco, Washington.

The contract for air mail service had already been awarded to Varney Airlines to begin service on April 6, 1926. They needed a place to land in Boise.

The community came together to build an airport.

On April 6, the runway was ready. The citizens turned out to celebrate. Then word came out about the missing pilot.

Telescoping a lot of history into a sentence, Varney Airlines had some success, eventually carrying passengers as well as mail, until they joined forces with other companies to create United Airlines in 1931. That’s why you’ll see a plaque at BOI declaring it the home of United Airlines. The need for better facilities and longer runways led to the development of that airport on the site we know today in 1936.

But what about Boise’s other airports? A reader who had found a map that mentioned two or three others asked me what I knew about them. Not a lot, until now.

Multiple Airports

At one point in 1946, there were five Boise airports, counting Floating Feather Airport, which was near Eagle. The Boise Airport had been operating for nine years, but Jr. College Field or College Field, where the original airport was, still operated. Boise Air Park came online, as did Bradley Field. These airports, or ‘Ports, as the Statesman sometimes called them, all competed for pilots and to make new pilots.

Here’s a brief description of each.

Floating Feather Airport

Located northeast of the intersection of Highway 55 and East Floating Feather Road, this landing strip opened in 1940 and was developed by Bill Woods. It was Boise’s first privately owned airport. Woods put up a wooden 12-plane hanger that first year.

Woods named the airport, and the name soon attached to the road. He thought it was a good name because he remembered so often bringing his aircraft “down the runway like a feather.” His planes were branded with a five-foot pair of wings in flashing bronze and black on each side, with “Boise Valley Flying Service” centered above the wings.

Student pilots at Floating Feather included the Northwest Nazarene College Flyers.

Many of the “Flying Heels,” a group of female stenographers determined to fly, did their training there, too. A flying club called the “Flying Feathers” began meeting and training at the airport in 1941.

Business was good at the Floating Feather Airport. They built a second hanger in 1942. Governor Chase Clark popped by in June to give awards to Civil Air Patrol members.

In April of 1943, student pilots at Floating Feather announced that they believed their instructor, Bill Woods, had set a record by soloing 467 students over a three-year period.

In addition to instruction, most of the airport operators flew hunters and anglers into what was then known as the “primitive area” of Central Idaho. None were more famous for it than Bill Woods. In a 1969 interview with the Idaho Statesman, he estimated that he had 29,000 hours of backcountry flying under his belt. In addition to sportsmen, Woods flew supplies to remote ranches. During the terrible winter of 1949, he was the lifeline for many living in the backcountry, even flying in milk for a baby.

Woods flew missions for Idaho Fish and Game, dropping feed for deer and elk, and famously conducting the first aerial roundup of antelope for the agency

This 1948 ad was one of many that christened Bill Woods “The Old Man of the Mountains.”

This 1948 ad was one of many that christened Bill Woods “The Old Man of the Mountains.”

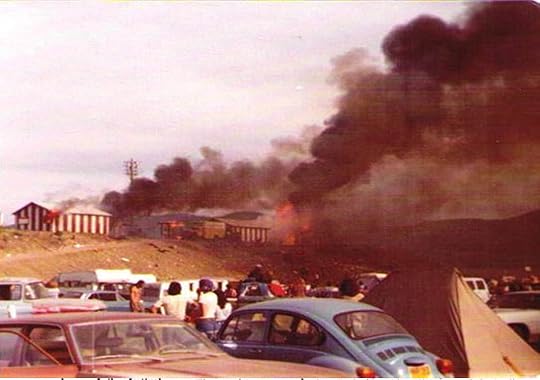

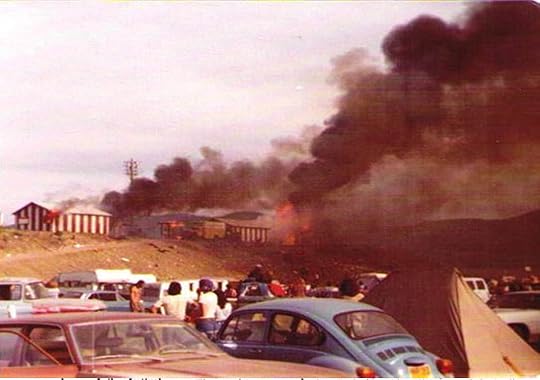

When reminiscing about his time running Floating Feather Airport, Woods said everything was divided into eras: Before the crash and after.

The crash happened about 9:30 pm on June 28, 1944. The Floating Feather Airport wasn’t the home base for the airplane when tragedy struck the airport, quite literally. An Army B-24 Liberator based at Gowen Field caught fire over West Boise. The pilot, probably attempting to land at the nearest airport, flew toward Floating Feather. Witnesses said the flames were intermittent at first. The plane exploded over the airport and went down about 200 feet from the wooden hanger, setting it on fire. Debris from the explosion scattered over a three-mile area, setting multiple fires. Three small planes, a car, a road grader, and the hanger all burned.

Eight men perished in the explosion of the plane. Two parachuted to safety, and the tail gunner was able to crawl out of the wreckage on the ground.

The crash and resultant fires attracted onlookers driving 2,000 cars to the highway adjacent to the airport. An Army B-24 Liberator based at Gowen Field, like the one above, exploded and set fire to the Floating Feather Airport in 1944.

An Army B-24 Liberator based at Gowen Field, like the one above, exploded and set fire to the Floating Feather Airport in 1944.

The Floating Feather Airport began operating again two weeks after the crash, but things were never quite the same.

As might be expected at a busy airport that catered to student pilots, there were several minor crashes there over the years. One fatality took place in 1943 when 23-year-old Frank Tweedy, an experienced smoke jumper, attempted a recreational parachute jump. He bailed out at 3,000 feet. Whether the jumper misjudged the distance to the ground, or the parachute was defective, it did not open.

Hundreds more successful jumps followed as the Boise Skydivers Club and the Alate Parachute Club called the airport home in later years. The skydivers began to outnumber the student pilots in the 1950s and 60s. They gave regular demonstrations and hosted multi-state skydiving meets. The Statesman often covered their exploits, ignoring the new pilots that soloed during that period. The “Centennial” skydiving show was in celebration of the Territorial Centennial in 1963.

The “Centennial” skydiving show was in celebration of the Territorial Centennial in 1963.

Coverage of skydiving and everything else at Floating Feather Airport petered out in the early 1970s. Bill Woods sold the airport in 1972 to developers. He passed away in 1974.

Boise Air Park

You could still land at Boise Air Park today if you had a pontoon plane. It would scare the heck out of swimmers and stand-up paddle boarders, though. Quinns Pond is where the planes took off and landed, beginning in 1945.

Operators Haven Schoonover, Lloyd Eason, and Paul Parks promoted Boise Air Park as the city’s “downtown airport.” All of the area airports in the 40s, 50s, and 60s offered flight training. Boise Air Park created a lot of pilots, each of whom was listed in the local paper when they got their licenses. Ken Arnold,

of UFO fame

, flew out of there.

All of the area airports in the 40s, 50s, and 60s offered flight training. Boise Air Park created a lot of pilots, each of whom was listed in the local paper when they got their licenses. Ken Arnold,

of UFO fame

, flew out of there.

Boise Air Park closed sometime in the early 1950s.

Bradley Field

Bradley Field, or Bradley Airport, which you can think of in today’s terms as Garden City’s airport, started in 1946, shortly after operations began at Boise Air Park. Though Garden City didn’t exist during most of the airport’s life, it was squarely in the middle of what is now the city.

There is some irony in using local landmarks to describe where the airport was. If you search for “Bradley Airport” in the Statesman archives, you could get the impression that being a landmark was the main purpose of the place. Houses for rent or for sale, accidents on the highway, business addresses—all were described by their relationship to Bradley Airport.

Here's a Google Maps view of Chinden Boulevard from the Fred Meyer Store on the left to 49th Street on the right, with an old aerial of Bradley Airport overlaid to pinpoint its location. Bradley Airport covered 270 acres with a single 3,000-foot gravel northwest/southeast runway built by Morrison Knudsen Company. Some of the original buildings canted at 45 degrees to the runway, serve as storage units today.

Bradley Airport covered 270 acres with a single 3,000-foot gravel northwest/southeast runway built by Morrison Knudsen Company. Some of the original buildings canted at 45 degrees to the runway, serve as storage units today.

Bradley Airport was built to serve as a “replacement airport” for Boise. That doesn’t mean that it replaced the main airport, only that private aircraft were encouraged to use it instead of the commercial airport.

On opening day in December 1946, the “resort” airport had a lounge with showers, a Skytel for overnight accommodations under construction, a Sky Store, aircraft shops, and a café. The airport offered private pilots some hangers and a lot of tie-down spots where they could keep their light planes. If you weren’t a pilot yet, there was training available.

The Bradley Airport received one of the nation’s major aviation awards in 1948. The National Aeronautics Association named it the Best Close-to-City Resort Type Airpark. It operated profitably for years but was starting to be a financial strain on the owners by 1971. They asked the county to take over the operation of Bradley Field.

The Bradley Airport received one of the nation’s major aviation awards in 1948. The National Aeronautics Association named it the Best Close-to-City Resort Type Airpark. It operated profitably for years but was starting to be a financial strain on the owners by 1971. They asked the county to take over the operation of Bradley Field.

Commissioners considered it. Taxpayers revolted, and the owners sold the property to a developer. Bradley Airport closed on February 22, 1973.

Strawberry Glenn

This airfield, where the Riverside residential area is now north of the Boise River and west of Glenwood, has been called many things. The original name, when farmer Bill Thomas first developed it in 1946, was the Green Meadow Airport. It was a cow pasture airport serving the needs of pilots with surplus planes and Piper Cubs.

Thomas sold the field to Harold Major, who called it Major’s Field until he sold it to Laddie Campbell, making it Campbell Airpark. George Dovel came along and purchased the strip but didn’t name it after himself, calling it Gem Heliport, with an emphasis on helicopters.

You could get flight instruction at the Gem Heliport, both fixed wing and rotary. You could also charter back-country flights.

In 1962, Harry Stone took over the operation and it became Stone Airport. Through all the owners, facilities at the little airport improved and expanded.

In 1968 or 69, Jack Hoke took over and officially named the field Strawberry Glenn Airport, something locals had been calling it for some time. A fire at the field’s only hanger destroyed the building and soon effectively closed the airport to the public.

In 1973, as Bradley Airport was flying the coop, Strawberry Glenn was reopening with expansion plans. The airport hosted fly-ins, small airshows, and the Strawberry Glenn Pilots Association through the 70s.

In 1979, Garden City began floating the idea of making Strawberry Glenn a municipal airport for general aviation. It would function as a “replacement” or “reliever” for Boise Airport. Owner Jack Hoke already had a housing developer lined up with a purchase option.

Garden City Mayor Ray Eld, a pilot himself, pushed the idea. It became a campaign issue, and probably one of the reasons the long-time mayor was defeated. The idea of purchasing Strawberry Glenn evaporated with the election. Strawberry Glenn was sold, and the site became the Riverside subdivision.

Harry Stone, who owned the airport in the early 60s explained why private airports were going broke in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview. “The only money you can make is through sale of parts, storage, and aircraft maintenance. Yet, you are required to have a large number of profitless acres for landing—all on which you have to pay taxes.”

That, and the fading interest in becoming a pilot, spelled the end of Boise’s private airports after more than 30 years in operation.

World War II created somewhere near 500,000 pilots. After the war, many of them wanted to continue flying. The war created pilots in another way, too. GIs returning from combat found that they could use money from the GI Bill to train for future careers. With all that training money, hundreds of flight schools popped up around the country.

Prognosticators following the war predicted that airplanes would be as cheap as automobiles and nearly as common. They envisioned airplane communities where you would roll your plane out of its garage in the morning and take off for work from an adjacent community airstrip.

Commercial aviation boomed, too. The war had turned aviation into the largest manufacturing industry in the world.

In a sense, private aviation and commercial aviation were in a race for the hearts of the American people. Commercial aviation won. Airplane ownership proved too costly for the average household. Meanwhile, commercial travel got cheaper and more accessible.

That’s a little background on why Boise had five airports at one time, but today, gets along with only three in the entire Treasure Valley: the Boise Airport (BOI), the Nampa Municipal Airport, and the Caldwell Industrial Airport. If you count Emmett as part of the Treasure Valley, they have a small municipal airport there, too.

The Boise Airport

The history of the Boise Airport is fairly well known, so I won’t spend a lot of time on that. Suffice to say that the original airport, named Booth Field but rarely called that, was built next to the Boise River, where Boise State University is today. The property was purchased from William T. Booth in 1926 and quickly readied for service.

Passenger service was far in the future, and nearly no one knew how to fly. So, why did Boise need a municipal airport? Air mail. Boise was part of the first commercial air mail route, which included stops in Elko, Nevada, and Pasco, Washington.

The contract for air mail service had already been awarded to Varney Airlines to begin service on April 6, 1926. They needed a place to land in Boise.

The community came together to build an airport.

On April 6, the runway was ready. The citizens turned out to celebrate. Then word came out about the missing pilot.

Telescoping a lot of history into a sentence, Varney Airlines had some success, eventually carrying passengers as well as mail, until they joined forces with other companies to create United Airlines in 1931. That’s why you’ll see a plaque at BOI declaring it the home of United Airlines. The need for better facilities and longer runways led to the development of that airport on the site we know today in 1936.

But what about Boise’s other airports? A reader who had found a map that mentioned two or three others asked me what I knew about them. Not a lot, until now.

Multiple Airports

At one point in 1946, there were five Boise airports, counting Floating Feather Airport, which was near Eagle. The Boise Airport had been operating for nine years, but Jr. College Field or College Field, where the original airport was, still operated. Boise Air Park came online, as did Bradley Field. These airports, or ‘Ports, as the Statesman sometimes called them, all competed for pilots and to make new pilots.

Here’s a brief description of each.

Floating Feather Airport

Located northeast of the intersection of Highway 55 and East Floating Feather Road, this landing strip opened in 1940 and was developed by Bill Woods. It was Boise’s first privately owned airport. Woods put up a wooden 12-plane hanger that first year.

Woods named the airport, and the name soon attached to the road. He thought it was a good name because he remembered so often bringing his aircraft “down the runway like a feather.” His planes were branded with a five-foot pair of wings in flashing bronze and black on each side, with “Boise Valley Flying Service” centered above the wings.

Student pilots at Floating Feather included the Northwest Nazarene College Flyers.

Many of the “Flying Heels,” a group of female stenographers determined to fly, did their training there, too. A flying club called the “Flying Feathers” began meeting and training at the airport in 1941.

Business was good at the Floating Feather Airport. They built a second hanger in 1942. Governor Chase Clark popped by in June to give awards to Civil Air Patrol members.

In April of 1943, student pilots at Floating Feather announced that they believed their instructor, Bill Woods, had set a record by soloing 467 students over a three-year period.

In addition to instruction, most of the airport operators flew hunters and anglers into what was then known as the “primitive area” of Central Idaho. None were more famous for it than Bill Woods. In a 1969 interview with the Idaho Statesman, he estimated that he had 29,000 hours of backcountry flying under his belt. In addition to sportsmen, Woods flew supplies to remote ranches. During the terrible winter of 1949, he was the lifeline for many living in the backcountry, even flying in milk for a baby.

Woods flew missions for Idaho Fish and Game, dropping feed for deer and elk, and famously conducting the first aerial roundup of antelope for the agency

This 1948 ad was one of many that christened Bill Woods “The Old Man of the Mountains.”

This 1948 ad was one of many that christened Bill Woods “The Old Man of the Mountains.” When reminiscing about his time running Floating Feather Airport, Woods said everything was divided into eras: Before the crash and after.

The crash happened about 9:30 pm on June 28, 1944. The Floating Feather Airport wasn’t the home base for the airplane when tragedy struck the airport, quite literally. An Army B-24 Liberator based at Gowen Field caught fire over West Boise. The pilot, probably attempting to land at the nearest airport, flew toward Floating Feather. Witnesses said the flames were intermittent at first. The plane exploded over the airport and went down about 200 feet from the wooden hanger, setting it on fire. Debris from the explosion scattered over a three-mile area, setting multiple fires. Three small planes, a car, a road grader, and the hanger all burned.

Eight men perished in the explosion of the plane. Two parachuted to safety, and the tail gunner was able to crawl out of the wreckage on the ground.

The crash and resultant fires attracted onlookers driving 2,000 cars to the highway adjacent to the airport.

An Army B-24 Liberator based at Gowen Field, like the one above, exploded and set fire to the Floating Feather Airport in 1944.

An Army B-24 Liberator based at Gowen Field, like the one above, exploded and set fire to the Floating Feather Airport in 1944. The Floating Feather Airport began operating again two weeks after the crash, but things were never quite the same.

As might be expected at a busy airport that catered to student pilots, there were several minor crashes there over the years. One fatality took place in 1943 when 23-year-old Frank Tweedy, an experienced smoke jumper, attempted a recreational parachute jump. He bailed out at 3,000 feet. Whether the jumper misjudged the distance to the ground, or the parachute was defective, it did not open.

Hundreds more successful jumps followed as the Boise Skydivers Club and the Alate Parachute Club called the airport home in later years. The skydivers began to outnumber the student pilots in the 1950s and 60s. They gave regular demonstrations and hosted multi-state skydiving meets. The Statesman often covered their exploits, ignoring the new pilots that soloed during that period.

The “Centennial” skydiving show was in celebration of the Territorial Centennial in 1963.

The “Centennial” skydiving show was in celebration of the Territorial Centennial in 1963. Coverage of skydiving and everything else at Floating Feather Airport petered out in the early 1970s. Bill Woods sold the airport in 1972 to developers. He passed away in 1974.

Boise Air Park

You could still land at Boise Air Park today if you had a pontoon plane. It would scare the heck out of swimmers and stand-up paddle boarders, though. Quinns Pond is where the planes took off and landed, beginning in 1945.

Operators Haven Schoonover, Lloyd Eason, and Paul Parks promoted Boise Air Park as the city’s “downtown airport.”

All of the area airports in the 40s, 50s, and 60s offered flight training. Boise Air Park created a lot of pilots, each of whom was listed in the local paper when they got their licenses. Ken Arnold,

of UFO fame

, flew out of there.

All of the area airports in the 40s, 50s, and 60s offered flight training. Boise Air Park created a lot of pilots, each of whom was listed in the local paper when they got their licenses. Ken Arnold,

of UFO fame

, flew out of there.Boise Air Park closed sometime in the early 1950s.

Bradley Field

Bradley Field, or Bradley Airport, which you can think of in today’s terms as Garden City’s airport, started in 1946, shortly after operations began at Boise Air Park. Though Garden City didn’t exist during most of the airport’s life, it was squarely in the middle of what is now the city.

There is some irony in using local landmarks to describe where the airport was. If you search for “Bradley Airport” in the Statesman archives, you could get the impression that being a landmark was the main purpose of the place. Houses for rent or for sale, accidents on the highway, business addresses—all were described by their relationship to Bradley Airport.

Here's a Google Maps view of Chinden Boulevard from the Fred Meyer Store on the left to 49th Street on the right, with an old aerial of Bradley Airport overlaid to pinpoint its location.

Bradley Airport covered 270 acres with a single 3,000-foot gravel northwest/southeast runway built by Morrison Knudsen Company. Some of the original buildings canted at 45 degrees to the runway, serve as storage units today.

Bradley Airport covered 270 acres with a single 3,000-foot gravel northwest/southeast runway built by Morrison Knudsen Company. Some of the original buildings canted at 45 degrees to the runway, serve as storage units today. Bradley Airport was built to serve as a “replacement airport” for Boise. That doesn’t mean that it replaced the main airport, only that private aircraft were encouraged to use it instead of the commercial airport.

On opening day in December 1946, the “resort” airport had a lounge with showers, a Skytel for overnight accommodations under construction, a Sky Store, aircraft shops, and a café. The airport offered private pilots some hangers and a lot of tie-down spots where they could keep their light planes. If you weren’t a pilot yet, there was training available.

The Bradley Airport received one of the nation’s major aviation awards in 1948. The National Aeronautics Association named it the Best Close-to-City Resort Type Airpark. It operated profitably for years but was starting to be a financial strain on the owners by 1971. They asked the county to take over the operation of Bradley Field.

The Bradley Airport received one of the nation’s major aviation awards in 1948. The National Aeronautics Association named it the Best Close-to-City Resort Type Airpark. It operated profitably for years but was starting to be a financial strain on the owners by 1971. They asked the county to take over the operation of Bradley Field.Commissioners considered it. Taxpayers revolted, and the owners sold the property to a developer. Bradley Airport closed on February 22, 1973.

Strawberry Glenn

This airfield, where the Riverside residential area is now north of the Boise River and west of Glenwood, has been called many things. The original name, when farmer Bill Thomas first developed it in 1946, was the Green Meadow Airport. It was a cow pasture airport serving the needs of pilots with surplus planes and Piper Cubs.

Thomas sold the field to Harold Major, who called it Major’s Field until he sold it to Laddie Campbell, making it Campbell Airpark. George Dovel came along and purchased the strip but didn’t name it after himself, calling it Gem Heliport, with an emphasis on helicopters.

You could get flight instruction at the Gem Heliport, both fixed wing and rotary. You could also charter back-country flights.

In 1962, Harry Stone took over the operation and it became Stone Airport. Through all the owners, facilities at the little airport improved and expanded.

In 1968 or 69, Jack Hoke took over and officially named the field Strawberry Glenn Airport, something locals had been calling it for some time. A fire at the field’s only hanger destroyed the building and soon effectively closed the airport to the public.

In 1973, as Bradley Airport was flying the coop, Strawberry Glenn was reopening with expansion plans. The airport hosted fly-ins, small airshows, and the Strawberry Glenn Pilots Association through the 70s.

In 1979, Garden City began floating the idea of making Strawberry Glenn a municipal airport for general aviation. It would function as a “replacement” or “reliever” for Boise Airport. Owner Jack Hoke already had a housing developer lined up with a purchase option.

Garden City Mayor Ray Eld, a pilot himself, pushed the idea. It became a campaign issue, and probably one of the reasons the long-time mayor was defeated. The idea of purchasing Strawberry Glenn evaporated with the election. Strawberry Glenn was sold, and the site became the Riverside subdivision.

Harry Stone, who owned the airport in the early 60s explained why private airports were going broke in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview. “The only money you can make is through sale of parts, storage, and aircraft maintenance. Yet, you are required to have a large number of profitless acres for landing—all on which you have to pay taxes.”

That, and the fading interest in becoming a pilot, spelled the end of Boise’s private airports after more than 30 years in operation.

Published on July 12, 2025 14:44

June 16, 2025

A Little Hydroplane History

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page once or twice a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.

We’re flying into a bit of Idaho hydroplane history today. If you think of a thundering race boat when you hear the term hydroplane, take heart. That’s where we’re headed. But first, we need to look at the evolution of the term.

The first reference to a hydroplane that I found in an Idaho newspaper included this drawing.

This boat used airplane propellers much like snow planes did in Idaho many years later. One could also postulate that this was the grandfather of the airboat that became popular for swamp travel.

In any case, this 1907 Italian invention was decidedly a boat that was called a hydroplane. The same paper in the same year reported a hydroplane being demonstrated on the Great Salt Lake by aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss. The pilot landed and took off from the water in his airplane equipped with pontoons. They called it a hydroplane.

Meanwhile, boaters in the Eastern states were competing for loving cups in their monstrous boats called hydroplanes. Some of them reached speeds of 40 miles per hour in 1911. At the same time, the secretary of the Navy was ordering what he called hydroplanes for use in war.

In 1912, the Idaho Statesman ran a feature article about “The Healthiest Sport in the World,” which any fool would know was motorboat racing, referred to often in the article as hydroplaning.

So, let’s pause here for a moment to explore the term. Hydro—water—combined with the word plane, logically would lead one to believe this was an airplane that could land on and take off from water. Point for the pilots.

But hydroplaning is a water-based activity. Let’s have our friends at Wikipedia explain.

“A key aspect of hydroplanes is that they use the water they are on for lift rather than buoyancy, as well as for propulsion and steering: when travelling at high speed water is forced downwards by the bottom of the boat's hull. The water therefore exerts an equal and opposite force upwards, lifting the vast majority of the hull out of the water. This process, happening at the surface of the water, is known as 'foiling.'”

Confusion about the term was rampant in the first half of the 20th Century. Newspaper reports used it to refer to airplanes just as often as for racing boats. But gradually, airplanes with pontoons became seaplanes, float planes, flying boats, and pontoon planes. By the 1950s, if it was a hydroplane, it was a roaring racing boat that you meant.

Roaring? Absolutely. Often called thunderboats, these hydroplaning monsters typically had 12-cylinder Rolls Royce or Allison airplane engines that had never seen a muffler.

Also, by the 1950s, unimaginable 40-mph boats were breaking records at 140-mph+.

Hydroplane aficionados in Idaho had to read about the Slo-Mo-Shun IV and Miss Bardhal in the papers and listen to the races on the radio from Seattle and San Francisco until 1958. That was the year hydros first came to Lake Coeur d’Alene.

The tables turned for Idaho boating fans when KING TV from Seattle broadcast the first Diamond Cup races from Coeur d’Alene. Maverick out of Las Vegas one the first and second cups in ’58 and ’59. Seattle Too took the trophy in 1960. Another Seattle boat, Miss Thriftway won in ’61, ’62, and ’63. Miss Exide took the trophy home for Seattle in ’64 and ’65. In 1966, Tahoe Miss out of Reno brought home the prize. There was no race in ’67. In 1968, Miss Bardahl won the Diamond Cup.

And that was it, for 45 years. There was talk many times of bringing the race back to Coeur d’Alene, but no one mustered up the money or the army of volunteers it takes to put on a race that drew up to 50,000 spectators. The citizens of city also soured on the event when crowds were sometimes rowdy. The bleachers for the race were long ago removed from their vantage point on Tubbs Hill.

Then, in 2013, promoters brought the races back for a long Labor Day Weekend of unlimited hydroplane racing. The event was expected to bring 30,000 spectators and about $12 million to Coeur d’Alene. It fell far short of that on both counts, and the Diamond Cup event was dropped, never to return since.

Hydroplane racing has taken place in other Idaho locations, notably near Payette and in Burley on the Snake River. While the racers are running powerful boats, they aren’t the “unlimited” hydroplanes that ran on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

By the way, the world speed record for hydroplanes was 317.596 mph the last time I looked. That was set in 1978 by Ken Warby in the Spirit of Australia at Blowering Dam in New South Wales, Australia. Miss Bardahl at one of the Diamond Cup races in Coeur d’Alene.

Miss Bardahl at one of the Diamond Cup races in Coeur d’Alene.

This is the memorial to a hydroplane racer near the Coeur d’Alene Resort. It honors Warner Gardner, who raced many times on the lake and was a crowd favorite. When hydroplane race driver Mira Slovak crashed on the lake in 1963, his boat turning into toothpicks, Gardner jumped from his own boat to save him. The memorial depicts an F-86 fighter jet suspended above a bronze hydroplane in honor of the former Air Force pilot who died in a 1968 hydroplane crash in Detroit.

This is the memorial to a hydroplane racer near the Coeur d’Alene Resort. It honors Warner Gardner, who raced many times on the lake and was a crowd favorite. When hydroplane race driver Mira Slovak crashed on the lake in 1963, his boat turning into toothpicks, Gardner jumped from his own boat to save him. The memorial depicts an F-86 fighter jet suspended above a bronze hydroplane in honor of the former Air Force pilot who died in a 1968 hydroplane crash in Detroit.

We’re flying into a bit of Idaho hydroplane history today. If you think of a thundering race boat when you hear the term hydroplane, take heart. That’s where we’re headed. But first, we need to look at the evolution of the term.

The first reference to a hydroplane that I found in an Idaho newspaper included this drawing.

This boat used airplane propellers much like snow planes did in Idaho many years later. One could also postulate that this was the grandfather of the airboat that became popular for swamp travel.

In any case, this 1907 Italian invention was decidedly a boat that was called a hydroplane. The same paper in the same year reported a hydroplane being demonstrated on the Great Salt Lake by aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss. The pilot landed and took off from the water in his airplane equipped with pontoons. They called it a hydroplane.

Meanwhile, boaters in the Eastern states were competing for loving cups in their monstrous boats called hydroplanes. Some of them reached speeds of 40 miles per hour in 1911. At the same time, the secretary of the Navy was ordering what he called hydroplanes for use in war.

In 1912, the Idaho Statesman ran a feature article about “The Healthiest Sport in the World,” which any fool would know was motorboat racing, referred to often in the article as hydroplaning.

So, let’s pause here for a moment to explore the term. Hydro—water—combined with the word plane, logically would lead one to believe this was an airplane that could land on and take off from water. Point for the pilots.

But hydroplaning is a water-based activity. Let’s have our friends at Wikipedia explain.

“A key aspect of hydroplanes is that they use the water they are on for lift rather than buoyancy, as well as for propulsion and steering: when travelling at high speed water is forced downwards by the bottom of the boat's hull. The water therefore exerts an equal and opposite force upwards, lifting the vast majority of the hull out of the water. This process, happening at the surface of the water, is known as 'foiling.'”

Confusion about the term was rampant in the first half of the 20th Century. Newspaper reports used it to refer to airplanes just as often as for racing boats. But gradually, airplanes with pontoons became seaplanes, float planes, flying boats, and pontoon planes. By the 1950s, if it was a hydroplane, it was a roaring racing boat that you meant.

Roaring? Absolutely. Often called thunderboats, these hydroplaning monsters typically had 12-cylinder Rolls Royce or Allison airplane engines that had never seen a muffler.

Also, by the 1950s, unimaginable 40-mph boats were breaking records at 140-mph+.

Hydroplane aficionados in Idaho had to read about the Slo-Mo-Shun IV and Miss Bardhal in the papers and listen to the races on the radio from Seattle and San Francisco until 1958. That was the year hydros first came to Lake Coeur d’Alene.

The tables turned for Idaho boating fans when KING TV from Seattle broadcast the first Diamond Cup races from Coeur d’Alene. Maverick out of Las Vegas one the first and second cups in ’58 and ’59. Seattle Too took the trophy in 1960. Another Seattle boat, Miss Thriftway won in ’61, ’62, and ’63. Miss Exide took the trophy home for Seattle in ’64 and ’65. In 1966, Tahoe Miss out of Reno brought home the prize. There was no race in ’67. In 1968, Miss Bardahl won the Diamond Cup.

And that was it, for 45 years. There was talk many times of bringing the race back to Coeur d’Alene, but no one mustered up the money or the army of volunteers it takes to put on a race that drew up to 50,000 spectators. The citizens of city also soured on the event when crowds were sometimes rowdy. The bleachers for the race were long ago removed from their vantage point on Tubbs Hill.

Then, in 2013, promoters brought the races back for a long Labor Day Weekend of unlimited hydroplane racing. The event was expected to bring 30,000 spectators and about $12 million to Coeur d’Alene. It fell far short of that on both counts, and the Diamond Cup event was dropped, never to return since.

Hydroplane racing has taken place in other Idaho locations, notably near Payette and in Burley on the Snake River. While the racers are running powerful boats, they aren’t the “unlimited” hydroplanes that ran on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

By the way, the world speed record for hydroplanes was 317.596 mph the last time I looked. That was set in 1978 by Ken Warby in the Spirit of Australia at Blowering Dam in New South Wales, Australia.

Miss Bardahl at one of the Diamond Cup races in Coeur d’Alene.

Miss Bardahl at one of the Diamond Cup races in Coeur d’Alene.

This is the memorial to a hydroplane racer near the Coeur d’Alene Resort. It honors Warner Gardner, who raced many times on the lake and was a crowd favorite. When hydroplane race driver Mira Slovak crashed on the lake in 1963, his boat turning into toothpicks, Gardner jumped from his own boat to save him. The memorial depicts an F-86 fighter jet suspended above a bronze hydroplane in honor of the former Air Force pilot who died in a 1968 hydroplane crash in Detroit.

This is the memorial to a hydroplane racer near the Coeur d’Alene Resort. It honors Warner Gardner, who raced many times on the lake and was a crowd favorite. When hydroplane race driver Mira Slovak crashed on the lake in 1963, his boat turning into toothpicks, Gardner jumped from his own boat to save him. The memorial depicts an F-86 fighter jet suspended above a bronze hydroplane in honor of the former Air Force pilot who died in a 1968 hydroplane crash in Detroit.

Published on June 16, 2025 14:48

May 27, 2025

The First Mid-Air Collision in Idaho History

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page about once a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.

In July 1969, the Boise Chamber of Commerce hosted a fly-in breakfast that took businesspeople from the area by plane to Smiley Creek, the highest tributary to the Salmon River. By all reports, the breakfast was a success, with more than 30 planes landing on the dirt strip to deposit guests for a morning repast.

In addition to the businesspeople in attendance, Idaho Director of Aeronautics Chet Moulton, Idaho Wheat Commissioner Harold West, and Secretary of State Pete Cenarussa were there. Cenarussa, a sheep rancher who flew himself in, got a little flack from the hosts about whether or not he’d been looking for sheep on the way to Smiley Creek.

Bob Lorimer, the Statesman staff writer who attended, wrote, “Everything clicked. The crisp, cool air was invigorating. The smell of bacon, eggs, and hash brown potatoes had that special 7,100-ft altitude aroma.”

Lorimer joked that he’d saved himself six-bits when he opted for a $15,000 insurance policy for the day, rather than the one that cost two dollars for $25,000. He was on his way home from the airport when he noticed a spiral of white smoke on the foothills. He didn’t think much of it, assuming it was just another grass fire.

Dozens of people in Boise had seen what Lorimer missed. Two small planes returning from the breakfast met wing-to-wing in mid-air over Boise’s North End.

The two planes glance off in different directions into the residential area, one narrowly missing a kindergarten. Miraculously, though debris fell out of the sky for blocks, there was little damage and no injuries on the ground.

One of the planes, a Model V35 Beechcraft Bonanza, clipped a power pole and nosed into a field behind a home at 61 E Horizon Drive, bursting into flames. Aboard were the pilot, Kenneth F. Flannery of LaGrande Oregon, Donald J. Ruzicka, of Milwaukie, Oregon, Dr. R.M. Kingland of 1821 Edgecliff Terrace, Boise, and Vincent Aguirre, 3509 Windsor Drive, Boise, co-owner of the Royal Restaurant.

The second plane, a Cessna 210E piloted by Basil P. W. Clapin, 3321 North Cole Road, Boise, plunged to earth on Fifth Street near the intersection with Union. Boise Attorney Eugene C. Smith, 7105 Brookover Drive, was also on board.

All six men in Idaho’s first mid-air collision were killed.

Many Boise residents witnessed the crash and marveled that no one on the ground was hurt by the debris that rained down.

John Larsen saw the aftermath of the crash and wrote a first person story about it for Idaho Magazine. You can read that here.

The first mid-air collision in Idaho wouldn’t be the last. Three mid-air collisions occurred over central Idaho, one in 2008 that killed three people, and collisions in 2013 and 2014 that killed one person each. In 2020, the state’s worst mid-air collision happened over Lake Coeur d’Alene, killing 8.

Cessna 210E plunged to earth on Fifth Street near the intersection with Union. ITD archival photo.

Cessna 210E plunged to earth on Fifth Street near the intersection with Union. ITD archival photo.

A Model V35 Beechcraft Bonanza clipped a power pole and nosed into a field behind a home on Horizon Drive, bursting into flames. ITD archival photo.

A Model V35 Beechcraft Bonanza clipped a power pole and nosed into a field behind a home on Horizon Drive, bursting into flames. ITD archival photo.

In July 1969, the Boise Chamber of Commerce hosted a fly-in breakfast that took businesspeople from the area by plane to Smiley Creek, the highest tributary to the Salmon River. By all reports, the breakfast was a success, with more than 30 planes landing on the dirt strip to deposit guests for a morning repast.

In addition to the businesspeople in attendance, Idaho Director of Aeronautics Chet Moulton, Idaho Wheat Commissioner Harold West, and Secretary of State Pete Cenarussa were there. Cenarussa, a sheep rancher who flew himself in, got a little flack from the hosts about whether or not he’d been looking for sheep on the way to Smiley Creek.

Bob Lorimer, the Statesman staff writer who attended, wrote, “Everything clicked. The crisp, cool air was invigorating. The smell of bacon, eggs, and hash brown potatoes had that special 7,100-ft altitude aroma.”

Lorimer joked that he’d saved himself six-bits when he opted for a $15,000 insurance policy for the day, rather than the one that cost two dollars for $25,000. He was on his way home from the airport when he noticed a spiral of white smoke on the foothills. He didn’t think much of it, assuming it was just another grass fire.

Dozens of people in Boise had seen what Lorimer missed. Two small planes returning from the breakfast met wing-to-wing in mid-air over Boise’s North End.

The two planes glance off in different directions into the residential area, one narrowly missing a kindergarten. Miraculously, though debris fell out of the sky for blocks, there was little damage and no injuries on the ground.

One of the planes, a Model V35 Beechcraft Bonanza, clipped a power pole and nosed into a field behind a home at 61 E Horizon Drive, bursting into flames. Aboard were the pilot, Kenneth F. Flannery of LaGrande Oregon, Donald J. Ruzicka, of Milwaukie, Oregon, Dr. R.M. Kingland of 1821 Edgecliff Terrace, Boise, and Vincent Aguirre, 3509 Windsor Drive, Boise, co-owner of the Royal Restaurant.

The second plane, a Cessna 210E piloted by Basil P. W. Clapin, 3321 North Cole Road, Boise, plunged to earth on Fifth Street near the intersection with Union. Boise Attorney Eugene C. Smith, 7105 Brookover Drive, was also on board.

All six men in Idaho’s first mid-air collision were killed.

Many Boise residents witnessed the crash and marveled that no one on the ground was hurt by the debris that rained down.

John Larsen saw the aftermath of the crash and wrote a first person story about it for Idaho Magazine. You can read that here.

The first mid-air collision in Idaho wouldn’t be the last. Three mid-air collisions occurred over central Idaho, one in 2008 that killed three people, and collisions in 2013 and 2014 that killed one person each. In 2020, the state’s worst mid-air collision happened over Lake Coeur d’Alene, killing 8.

Cessna 210E plunged to earth on Fifth Street near the intersection with Union. ITD archival photo.

Cessna 210E plunged to earth on Fifth Street near the intersection with Union. ITD archival photo. A Model V35 Beechcraft Bonanza clipped a power pole and nosed into a field behind a home on Horizon Drive, bursting into flames. ITD archival photo.

A Model V35 Beechcraft Bonanza clipped a power pole and nosed into a field behind a home on Horizon Drive, bursting into flames. ITD archival photo.

Published on May 27, 2025 08:33

April 29, 2025

Dreams of Rippling Wheat Fields Shattered

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page about once a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.

Years of drought in the Midwest, combined with unsustainable farming practices, brought on the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. Did you think Idaho was spared? Not entirely.

The drought in the 30s spread into Idaho, but since most farms in the arid southern part of the state were gravity irrigated, the impact was not as severe. There were exceptions, though, particularly in Oneida and Cassia counties west of Malad, where hardscrabble farmers were trying to eke out a living from dryland agriculture.

Land that naturally grew grass and sagebrush could not sustain crops when rainfall was scarce. In Idaho, the 1930s witnessed the most severe drought periods on record, with extreme drought conditions occurring in 7 out of 12 years from 1929-1940. Some Idaho farmers found themselves surrounded by drifting sand instead of healthy row crops.

Children playing in the drifted sand in Oneida County, 1935. Library of Congress.

Children playing in the drifted sand in Oneida County, 1935. Library of Congress.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Resettlement Administration as part of his New Deal program to help citizens get back on their feet. In Idaho, that meant buying out about 100 failing farms in Oneida and Cassia counties and assisting the families with relocation, mainly in Oregon’s Willamette Valley and in Northern Idaho. The government provided low-interest loans and grants to get the farmers producing again.

Most struggling farm families had quit paying taxes, so county and school coffers were empty. More than 100 submarginal farms had already been abandoned and were owned by the counties when the federal government stepped in.

A photo caption on the Library of Congress website sums up the problem: “The tract on which these buildings stand should never have been farmed, but it took protracted drought to drive that lesson home.”

A photo caption on the Library of Congress website sums up the problem: “The tract on which these buildings stand should never have been farmed, but it took protracted drought to drive that lesson home.”

R.R. Best, the project manager, as quoted in the Idaho Statesman, said, “The expenditure of approximately $409,000 for private and county lands will make possible payment of thousands of dollars in delinquent taxes to the county, consolidation or retirement of several school districts, and give many of the settlers sufficient cash to aid relocation.”

Relocating or tearing down farm buildings and removing fencing put about 100 men to work. They removed 187 miles of old fence and made 10,000 juniper posts to build 1,000 miles of new fence to protect the grassland.

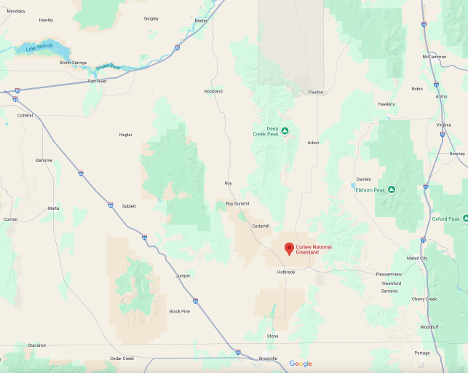

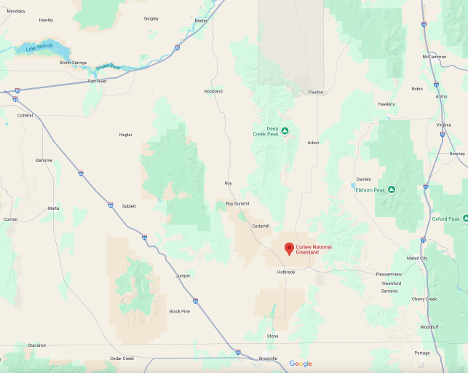

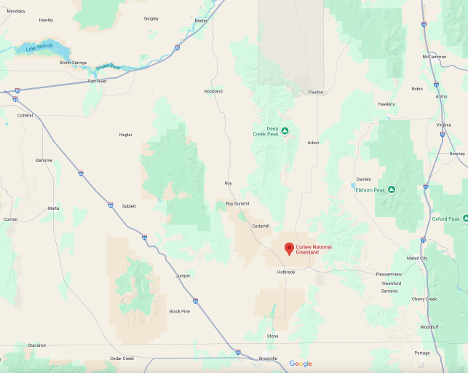

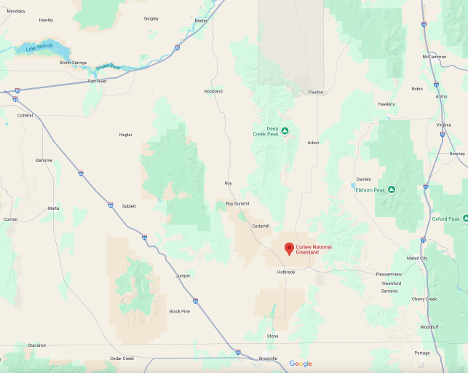

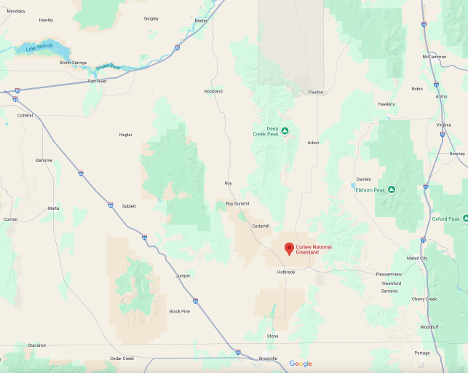

The Forest Service became the new land manager of what is now about 47,000 acres of public and formerly private land, turning it back to cover that would be sustainable. That area is now known as the Curlew National Grasslands.

To get to the Curlew National Grasslands, first go to Utah. Take I-84 south to Snowville, then head north back across the Idaho line to Holbrook.

To get to the Curlew National Grasslands, first go to Utah. Take I-84 south to Snowville, then head north back across the Idaho line to Holbrook.

In a 1937 report from the Resettlement Administration, D.L. Bush, the Idaho director, noted that 6,000 farm families had received help at some level, including loans averaging about $1,400 and assistance grants to 3,333 destitute families.

The administration took pains to point out that no one was forced off their land. Relocation and buyouts were voluntary.

Today, if you drive between Holbrook and Malad City on the nearly deserted road between them—as I often have—you’ll see little sign that the land there was once dotted with the farms of people whose hopes withered in the summer sun.

Years of drought in the Midwest, combined with unsustainable farming practices, brought on the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. Did you think Idaho was spared? Not entirely.

The drought in the 30s spread into Idaho, but since most farms in the arid southern part of the state were gravity irrigated, the impact was not as severe. There were exceptions, though, particularly in Oneida and Cassia counties west of Malad, where hardscrabble farmers were trying to eke out a living from dryland agriculture.

Land that naturally grew grass and sagebrush could not sustain crops when rainfall was scarce. In Idaho, the 1930s witnessed the most severe drought periods on record, with extreme drought conditions occurring in 7 out of 12 years from 1929-1940. Some Idaho farmers found themselves surrounded by drifting sand instead of healthy row crops.

Children playing in the drifted sand in Oneida County, 1935. Library of Congress.

Children playing in the drifted sand in Oneida County, 1935. Library of Congress. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Resettlement Administration as part of his New Deal program to help citizens get back on their feet. In Idaho, that meant buying out about 100 failing farms in Oneida and Cassia counties and assisting the families with relocation, mainly in Oregon’s Willamette Valley and in Northern Idaho. The government provided low-interest loans and grants to get the farmers producing again.

Most struggling farm families had quit paying taxes, so county and school coffers were empty. More than 100 submarginal farms had already been abandoned and were owned by the counties when the federal government stepped in.

A photo caption on the Library of Congress website sums up the problem: “The tract on which these buildings stand should never have been farmed, but it took protracted drought to drive that lesson home.”

A photo caption on the Library of Congress website sums up the problem: “The tract on which these buildings stand should never have been farmed, but it took protracted drought to drive that lesson home.” R.R. Best, the project manager, as quoted in the Idaho Statesman, said, “The expenditure of approximately $409,000 for private and county lands will make possible payment of thousands of dollars in delinquent taxes to the county, consolidation or retirement of several school districts, and give many of the settlers sufficient cash to aid relocation.”

Relocating or tearing down farm buildings and removing fencing put about 100 men to work. They removed 187 miles of old fence and made 10,000 juniper posts to build 1,000 miles of new fence to protect the grassland.

The Forest Service became the new land manager of what is now about 47,000 acres of public and formerly private land, turning it back to cover that would be sustainable. That area is now known as the Curlew National Grasslands.

To get to the Curlew National Grasslands, first go to Utah. Take I-84 south to Snowville, then head north back across the Idaho line to Holbrook.

To get to the Curlew National Grasslands, first go to Utah. Take I-84 south to Snowville, then head north back across the Idaho line to Holbrook. In a 1937 report from the Resettlement Administration, D.L. Bush, the Idaho director, noted that 6,000 farm families had received help at some level, including loans averaging about $1,400 and assistance grants to 3,333 destitute families.

The administration took pains to point out that no one was forced off their land. Relocation and buyouts were voluntary.

Today, if you drive between Holbrook and Malad City on the nearly deserted road between them—as I often have—you’ll see little sign that the land there was once dotted with the farms of people whose hopes withered in the summer sun.

Published on April 29, 2025 08:09

March 26, 2025

The Bravery of Bernie Fisher

Editor's note: I'll post new stories on my Facebook page about once a month. If you'd like to get a new story every week, along with a lot of other content, click Subscribe at the top right of this page.