Rick Just's Blog, page 4

December 12, 2024

Canvas Dams

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

When you think of a dam, Hoover probably comes to mind, or maybe Lucky Peak. Both have Idaho stories behind them. Today, though, I’d like to recognize the lowliest of irrigation control devices, the canvas dam.

If you didn’t grow up on a farm you may never have even heard of a canvas dam. They are a marvel. They are simple, portable, durable, functional, and cheap. I’m going to let someone eminently more qualified than myself describe canvas dams and their use.

How much more qualified? Well, in the publication Irrigation in the United States which was published in 1902, its author, Frederick Haynes Newell, was described as “Hydraulic Engineer and Chief of the Division of Hydrography of the United States Geological Survey; Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers; Expert on Irrigation for the Eleventh and Twelfth United States Censuses; Secretary of the American Forestry Association, etc.”

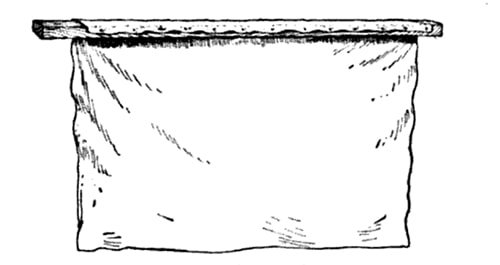

Mr. Newell said that a canvas dam “consists of a piece of stout cloth, one edge of which is tacked to a stick long enough to extend across the lateral ditch or furrow. The canvas, falling into the furrow, fits the sides and bottoms, and is held in place by a clod of dirt thrown upon it. Water meeting the obstruction still further forces the canvas down, making a fairly tight dam, against which it accumulates and overflows into the field.”

I remember often seeing my father don his rubber waders and head out to a field with a small dam, canvas loosely wrapped around the pole, propped on one shoulder, a shovel across the other. If the ditch was big, so was the dam, so he’d usually be dragging those.

Gravity irrigation is not easy work, but I think it was his favorite work that did not involve straddling a horse. Encouraging water to flow down furrows or across pasture land gave him time to think and enjoy the weather.

My great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, knew about such men and honored them in poetry more than once.

The Man With the Shovel

After the work of construction

After the dam is made,

After the dream is realized

That has been long delayed:

Then comes the man with the shovel,

The man who is king in the west,

He takes up the ceaseless burden

And lets the dam builder rest.

He may not have vision of learning,

He may not have time to dream,

But he knows a field of sagebrush

And an irrigation stream.

Take away men of theories

With their plans so futile and dim,

But leave us the man with the shovel,

We cannot live without him!

She did not mention canvas dams, as if shovels would do the trick alone. She also did not mention the obligatory swearing when no matter how much sod a man would put on the canvas to hold it in place the dam would wash out, canvas flapping downstream like a wagging tongue.

Canvas dams were ubiquitous for about a hundred years on Idaho farms. No doubt there are a few of them in use today. Yet, do a Google images search for Canvas Dam and only one decent picture comes up, that one from Nevada in the 1980s and in the Smithsonian collection.

That doesn’t make the canvas dam picture in your old family album valuable, but it does make it rare. Share it if you have one.

When you think of a dam, Hoover probably comes to mind, or maybe Lucky Peak. Both have Idaho stories behind them. Today, though, I’d like to recognize the lowliest of irrigation control devices, the canvas dam.

If you didn’t grow up on a farm you may never have even heard of a canvas dam. They are a marvel. They are simple, portable, durable, functional, and cheap. I’m going to let someone eminently more qualified than myself describe canvas dams and their use.

How much more qualified? Well, in the publication Irrigation in the United States which was published in 1902, its author, Frederick Haynes Newell, was described as “Hydraulic Engineer and Chief of the Division of Hydrography of the United States Geological Survey; Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers; Expert on Irrigation for the Eleventh and Twelfth United States Censuses; Secretary of the American Forestry Association, etc.”

Mr. Newell said that a canvas dam “consists of a piece of stout cloth, one edge of which is tacked to a stick long enough to extend across the lateral ditch or furrow. The canvas, falling into the furrow, fits the sides and bottoms, and is held in place by a clod of dirt thrown upon it. Water meeting the obstruction still further forces the canvas down, making a fairly tight dam, against which it accumulates and overflows into the field.”

I remember often seeing my father don his rubber waders and head out to a field with a small dam, canvas loosely wrapped around the pole, propped on one shoulder, a shovel across the other. If the ditch was big, so was the dam, so he’d usually be dragging those.

Gravity irrigation is not easy work, but I think it was his favorite work that did not involve straddling a horse. Encouraging water to flow down furrows or across pasture land gave him time to think and enjoy the weather.

My great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, knew about such men and honored them in poetry more than once.

The Man With the Shovel

After the work of construction

After the dam is made,

After the dream is realized

That has been long delayed:

Then comes the man with the shovel,

The man who is king in the west,

He takes up the ceaseless burden

And lets the dam builder rest.

He may not have vision of learning,

He may not have time to dream,

But he knows a field of sagebrush

And an irrigation stream.

Take away men of theories

With their plans so futile and dim,

But leave us the man with the shovel,

We cannot live without him!

She did not mention canvas dams, as if shovels would do the trick alone. She also did not mention the obligatory swearing when no matter how much sod a man would put on the canvas to hold it in place the dam would wash out, canvas flapping downstream like a wagging tongue.

Canvas dams were ubiquitous for about a hundred years on Idaho farms. No doubt there are a few of them in use today. Yet, do a Google images search for Canvas Dam and only one decent picture comes up, that one from Nevada in the 1980s and in the Smithsonian collection.

That doesn’t make the canvas dam picture in your old family album valuable, but it does make it rare. Share it if you have one.

Published on December 12, 2024 04:00

December 11, 2024

Camas: A Tribal Staple

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Camas bulbs were important enough to the Bannock Indians that they went to war over them in 1878. Have you ever wondered how they were used?

Well, they ate them, of course. But the indigenous people who depended on the root did not simply dig them up and start chewing. Camas bulbs are reportedly nasty if eaten raw. They have a soapy taste and get gummy when you chew them, making the whole mess stick to your teeth.

So, cooking, then. The women of the tribe would dig them up in the spring and, after removing the papery sheath from the bulbs, cook them in earthen ovens. These ovens were pits lined with rocks. The women put alternating layers of grass and camas bulbs into the pits and covered them with soil. Once the layering was completed, they would build a fire on top of the pit. The rocks would retain the heat and cook the one- to two-inch bulbs. It took several days.

Once cooked camas bulbs are sweet. Some have described their taste as something like a baked pear or a water chestnut.

Since we’re talking about eating camas bulbs, we should note that you don’t want to sample Death Camas. You’re not likely to confuse the plants in the field, at least when they are in bloom. Death Camas, which blooms later in June, has white flowers that are more tightly arranged the brilliant blue flowers of the edible variety. No part of the Death Camas is edible.

Maybe you should just enjoy the blossoms.

Camas bulbs were important enough to the Bannock Indians that they went to war over them in 1878. Have you ever wondered how they were used?

Well, they ate them, of course. But the indigenous people who depended on the root did not simply dig them up and start chewing. Camas bulbs are reportedly nasty if eaten raw. They have a soapy taste and get gummy when you chew them, making the whole mess stick to your teeth.

So, cooking, then. The women of the tribe would dig them up in the spring and, after removing the papery sheath from the bulbs, cook them in earthen ovens. These ovens were pits lined with rocks. The women put alternating layers of grass and camas bulbs into the pits and covered them with soil. Once the layering was completed, they would build a fire on top of the pit. The rocks would retain the heat and cook the one- to two-inch bulbs. It took several days.

Once cooked camas bulbs are sweet. Some have described their taste as something like a baked pear or a water chestnut.

Since we’re talking about eating camas bulbs, we should note that you don’t want to sample Death Camas. You’re not likely to confuse the plants in the field, at least when they are in bloom. Death Camas, which blooms later in June, has white flowers that are more tightly arranged the brilliant blue flowers of the edible variety. No part of the Death Camas is edible.

Maybe you should just enjoy the blossoms.

Published on December 11, 2024 04:00

December 10, 2024

Why did the Stinker Signs go Away?

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Have you ever asked yourself whatever happened to all those Stinker Station signs?

Farris Lind had built his business on humor. Suddenly, in 1965 someone wanted to throw a bucket of cold water all over the most visible part of his funny business. That someone was Claudia Alta Johnson, better known as First Lady “Ladybird” Johnson.

The Highway Beautification Act (HBA) of 1965 was Ladybird Johnson’s signature issue. She and her supporters were getting tired of the proliferation of billboards alongside federal highways in the United States. The act prohibited most outdoor advertising along Interstate and federal highways and required removal or screening of junkyards in highway viewsheds.

The law threatened a key component of Farris Lind's success. In 1969, he sued the State of Idaho because the Legislature had passed laws to bring the state into compliance with the HBA. Signs were not allowed within 660 feet of a federal highway right-of-way. Lind said, "The federal and state government have no right to deprive a farmer or other landowner of any rental income he can get from signs on his property. I owe it to myself to take a swing at bureaucracy" (Capital Journal, December 12, 1969).

For signs on private property, Lind was paying $10-$15 a month rental. Some signs were on property he'd purchased.

The lawsuit asked that the highway beautification law be declared unconstitutional. Lind contended that it was unconstitutional because it prohibited the right to conduct a lawful business and impaired contractual arrangements Lind had with landowners.

The suit didn't gain any traction, and most of the signs came down, ending a run of about 25 years of memorable advertising.

Note that you can learn much more about Fearless Farris, an Idaho Original, by reading my book about him, which is available on your lower right.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

Have you ever asked yourself whatever happened to all those Stinker Station signs?

Farris Lind had built his business on humor. Suddenly, in 1965 someone wanted to throw a bucket of cold water all over the most visible part of his funny business. That someone was Claudia Alta Johnson, better known as First Lady “Ladybird” Johnson.

The Highway Beautification Act (HBA) of 1965 was Ladybird Johnson’s signature issue. She and her supporters were getting tired of the proliferation of billboards alongside federal highways in the United States. The act prohibited most outdoor advertising along Interstate and federal highways and required removal or screening of junkyards in highway viewsheds.

The law threatened a key component of Farris Lind's success. In 1969, he sued the State of Idaho because the Legislature had passed laws to bring the state into compliance with the HBA. Signs were not allowed within 660 feet of a federal highway right-of-way. Lind said, "The federal and state government have no right to deprive a farmer or other landowner of any rental income he can get from signs on his property. I owe it to myself to take a swing at bureaucracy" (Capital Journal, December 12, 1969).

For signs on private property, Lind was paying $10-$15 a month rental. Some signs were on property he'd purchased.

The lawsuit asked that the highway beautification law be declared unconstitutional. Lind contended that it was unconstitutional because it prohibited the right to conduct a lawful business and impaired contractual arrangements Lind had with landowners.

The suit didn't gain any traction, and most of the signs came down, ending a run of about 25 years of memorable advertising.

Note that you can learn much more about Fearless Farris, an Idaho Original, by reading my book about him, which is available on your lower right.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

Published on December 10, 2024 04:00

December 9, 2024

The Ross Hall Girls

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

During World War II, more than 292,000 “boots” trained at Farragut Naval Training Station, north of Coeur d’Alene. Sandpoint, Idaho, photographer Ross Hall provided class photographs the boots could buy. The photographs included a list of those pictured. It was quite a production.

The shot below shows three “Ross Hall Girls,” who kept track of names of those in the pictures and took orders. They’re shown in their booths with a class lined up for a photograph in the background. Ross Hall himself probably took this picture. To give you an idea of the scale of this operation, In March 1944, a record 20,891 boots had their pictures taken.

Hundreds of company photos are on file today at Farragut State Park to help those wanting to know more about family members who went through training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

During World War II, more than 292,000 “boots” trained at Farragut Naval Training Station, north of Coeur d’Alene. Sandpoint, Idaho, photographer Ross Hall provided class photographs the boots could buy. The photographs included a list of those pictured. It was quite a production.

The shot below shows three “Ross Hall Girls,” who kept track of names of those in the pictures and took orders. They’re shown in their booths with a class lined up for a photograph in the background. Ross Hall himself probably took this picture. To give you an idea of the scale of this operation, In March 1944, a record 20,891 boots had their pictures taken.

Hundreds of company photos are on file today at Farragut State Park to help those wanting to know more about family members who went through training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

Published on December 09, 2024 04:00

December 8, 2024

The Conversion of Harry Orchard

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

There are enough stories about Harry Orchard to fill a hundred blog posts. Today’s is about how he found religion.

Harry Orchard is well-known in Idaho as the man who rigged the bomb on that Caldwell gate that killed Frank Steunenberg, former governor of Idaho. Less well-known is that Harry’s real name was Albert Edward Horsley, a one-time cheesemaker from Wooler, Ontario, Canada.

Orchard pleaded guilty to the murder and turned state’s evidence in the famous trial of “Big Bill” Haywood and Charles Moyer, both leaders in the Western Federation of Miners, and labor activist George Pettibone. Clarence Darrow got those men off, but Orchard went to prison, admitting to 26 murders.

Orchard’s conversion started before his sentencing in 1908. He had been moved to plead guilty by his reading of the Bible and was convinced it was the only way to save his soul. At first sentenced to hang, that sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

In the early days of his sentence, Orchard received a visit from the 21-year-old son of Governor Steunenberg, Julian. The young man brought a packet of pamphlets and books associated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church on the behest of his mother, Eveline Belle Steunenberg. She and her children were church members, and she urged Orchard to “give his life fully to Christ.”

He did so, joining the Adventist faith. He was baptized January 1, 1909 at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Mrs. Steunenberg saw God’s hand in the assassination of her husband in a way that comforted her. It came out that Orchard had made three previous attempts to kill the man, all of which failed. On the day of the assassination, the former governor had told his family he was moved to worship with them. Though his death came just hours later, Mrs. Steunenberg came to believe God had stayed the hand of the assassin long enough to bring the governor into the fold. She would petition for Harry Orchard’s pardon and release in 1922.

Harry Orchard spent 46 years in Idaho’s prison system—though mostly not within the walls of the prison. That’s a story for another day. Orchard died April 13, 1954, at the age of 88. He was the longest serving prisoner in the system. His funeral service was conducted by the Boise Seventh-day Adventist Church.

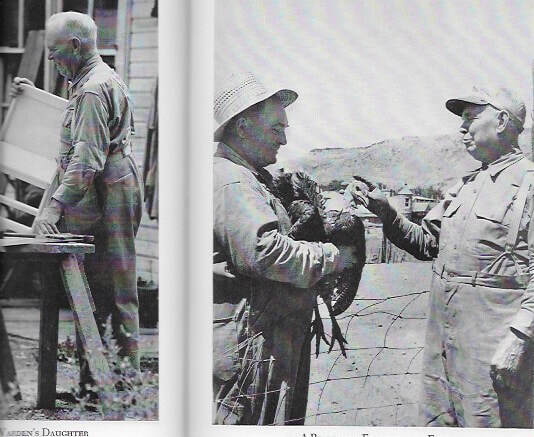

Left, Harry Orchard working at his home near the prison. Right Harry talking with an unidentified man holding a turkey.

Left, Harry Orchard working at his home near the prison. Right Harry talking with an unidentified man holding a turkey.

There are enough stories about Harry Orchard to fill a hundred blog posts. Today’s is about how he found religion.

Harry Orchard is well-known in Idaho as the man who rigged the bomb on that Caldwell gate that killed Frank Steunenberg, former governor of Idaho. Less well-known is that Harry’s real name was Albert Edward Horsley, a one-time cheesemaker from Wooler, Ontario, Canada.

Orchard pleaded guilty to the murder and turned state’s evidence in the famous trial of “Big Bill” Haywood and Charles Moyer, both leaders in the Western Federation of Miners, and labor activist George Pettibone. Clarence Darrow got those men off, but Orchard went to prison, admitting to 26 murders.

Orchard’s conversion started before his sentencing in 1908. He had been moved to plead guilty by his reading of the Bible and was convinced it was the only way to save his soul. At first sentenced to hang, that sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

In the early days of his sentence, Orchard received a visit from the 21-year-old son of Governor Steunenberg, Julian. The young man brought a packet of pamphlets and books associated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church on the behest of his mother, Eveline Belle Steunenberg. She and her children were church members, and she urged Orchard to “give his life fully to Christ.”

He did so, joining the Adventist faith. He was baptized January 1, 1909 at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Mrs. Steunenberg saw God’s hand in the assassination of her husband in a way that comforted her. It came out that Orchard had made three previous attempts to kill the man, all of which failed. On the day of the assassination, the former governor had told his family he was moved to worship with them. Though his death came just hours later, Mrs. Steunenberg came to believe God had stayed the hand of the assassin long enough to bring the governor into the fold. She would petition for Harry Orchard’s pardon and release in 1922.

Harry Orchard spent 46 years in Idaho’s prison system—though mostly not within the walls of the prison. That’s a story for another day. Orchard died April 13, 1954, at the age of 88. He was the longest serving prisoner in the system. His funeral service was conducted by the Boise Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Left, Harry Orchard working at his home near the prison. Right Harry talking with an unidentified man holding a turkey.

Left, Harry Orchard working at his home near the prison. Right Harry talking with an unidentified man holding a turkey.

Published on December 08, 2024 04:00

December 7, 2024

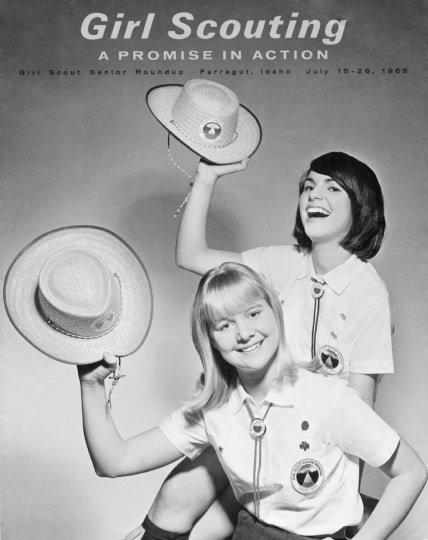

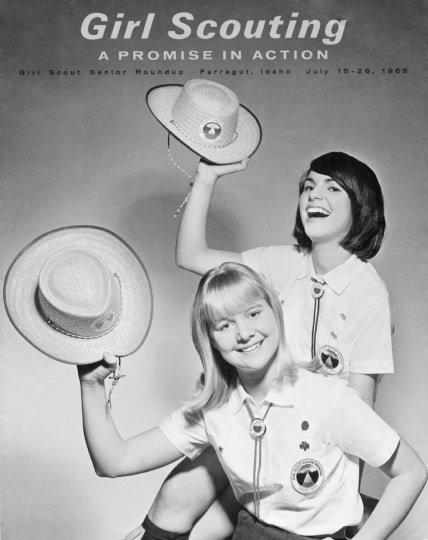

The Girl Scouts were Park Creators

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

The Girl Scouts played a huge role in the creation of Idaho’s state parks system. Governor Robert E. Smylie had been trying to convince the Legislature for years to create a system of state parks managed by professionals. In 1965 a lot of things came together to make Smylie’s idea palatable to Legislators. He’d lined up the gift of the Railroad Ranch, which would later become Harriman State Park. The Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund program was created, offering funding for park development. The state had recently traded land that was about to end up under Dworshak Reservoir for that old Navy base on the shores of Lake Pend Orielle.

The Girl Scouts sealed the deal, though. Smylie convinced them that Farragut would be the perfect place to hold the 1965 national Girl Scout Senior Roundup. It would bring a lot of money into north Idaho. So, with that commitment from the girl scouts in hand, the Legislature finally gave Smylie the parks department he was looking for.

Now, if you’re thinking it was the Boy Scouts that had the big gatherings, you’re not wrong. Just two days after the Girl Scout Roundup concluded, Governor Smylie sent out a press release announcing that Farragut had been selected as the site for the World Boy Scout Jamboree. Smylie, said, “Idaho is bigger today. The biggest planned event in Idaho’s history is no longer a hope; it’s an assured occurrence.”

That was a great event, and so were national Boy Scout events that came along in following years. But it was the Girl Scouts who led the way.

During the opening ceremonies for the 1965 Senior Girl Scout Roundup Governor Smylie shouted over the noise, “If you want a comparison in numbers, there are as many people here on this Idaho spot right now as live in Caldwell.” The program opened with 11,000 voices singing Girl Scout songs, recordings of which still sell occasionally on eBay today.

The Girl Scouts played a huge role in the creation of Idaho’s state parks system. Governor Robert E. Smylie had been trying to convince the Legislature for years to create a system of state parks managed by professionals. In 1965 a lot of things came together to make Smylie’s idea palatable to Legislators. He’d lined up the gift of the Railroad Ranch, which would later become Harriman State Park. The Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund program was created, offering funding for park development. The state had recently traded land that was about to end up under Dworshak Reservoir for that old Navy base on the shores of Lake Pend Orielle.

The Girl Scouts sealed the deal, though. Smylie convinced them that Farragut would be the perfect place to hold the 1965 national Girl Scout Senior Roundup. It would bring a lot of money into north Idaho. So, with that commitment from the girl scouts in hand, the Legislature finally gave Smylie the parks department he was looking for.

Now, if you’re thinking it was the Boy Scouts that had the big gatherings, you’re not wrong. Just two days after the Girl Scout Roundup concluded, Governor Smylie sent out a press release announcing that Farragut had been selected as the site for the World Boy Scout Jamboree. Smylie, said, “Idaho is bigger today. The biggest planned event in Idaho’s history is no longer a hope; it’s an assured occurrence.”

That was a great event, and so were national Boy Scout events that came along in following years. But it was the Girl Scouts who led the way.

During the opening ceremonies for the 1965 Senior Girl Scout Roundup Governor Smylie shouted over the noise, “If you want a comparison in numbers, there are as many people here on this Idaho spot right now as live in Caldwell.” The program opened with 11,000 voices singing Girl Scout songs, recordings of which still sell occasionally on eBay today.

Published on December 07, 2024 04:00

December 6, 2024

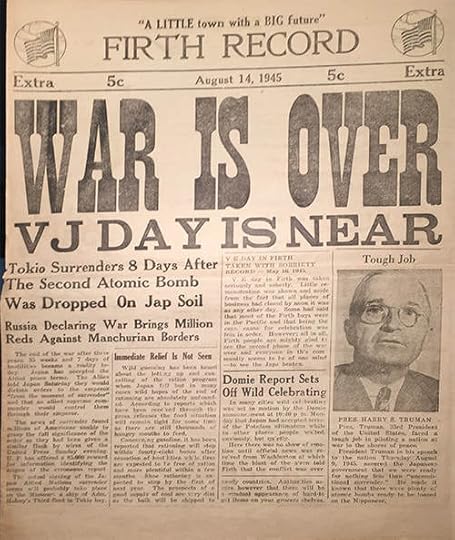

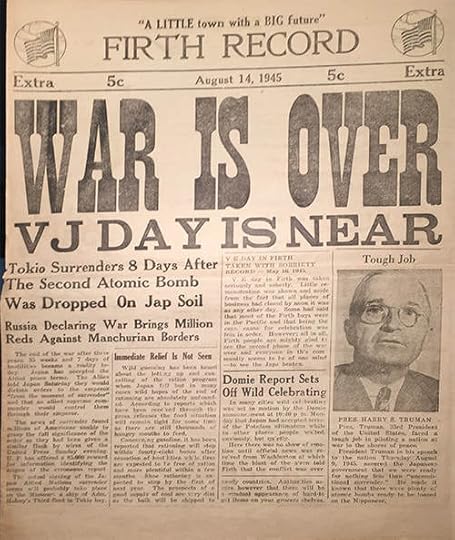

The Firth Record

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Chances are you’ve never heard of The Firth Record. It was the town paper of Firth, publishing from 1945 into the early 1950s. Copies of the old paper are so rare that the Idaho State Historical Society doesn’t have any in their microfilm collection at the state archives. I’ve recently come into possession of 26 editions of the paper, thanks to preservation-minded members of my family, particularly Kathy Christiansen. I’ve asked the Historical Society to scan them for the archives. Once that’s done, they will be donated to the Bingham County Historical Society.

Meanwhile, I ran across a surprising claim to fame for The Firth Record. In a retrospective published in the January 28, 1949 edition, the editor noted that one of the “extras” the paper had published drew “acclaim all over the nation, as the first to hit the streets, after the memorable Japanese surrender, marking the end of hostilities in a war torn world.”

Why? The editor explained. “Four months after the war’s end, The Firth Record was given national and international notoriety, with the announcement that it was the ‘firstest’ among the firsts. This was disclosed by the Publishers Auxiliary, a weekly newspaper published in Chicago.”

So, a Firth first. Further, the first Firthian to read the paper was Harold Brighton, who had it in his hands two minutes after it came off the press.

That moment of fame is gratifying to those of us from Firth who have endured jokes over the years such as, “Firth? Is that near Thecond?”

Chances are you’ve never heard of The Firth Record. It was the town paper of Firth, publishing from 1945 into the early 1950s. Copies of the old paper are so rare that the Idaho State Historical Society doesn’t have any in their microfilm collection at the state archives. I’ve recently come into possession of 26 editions of the paper, thanks to preservation-minded members of my family, particularly Kathy Christiansen. I’ve asked the Historical Society to scan them for the archives. Once that’s done, they will be donated to the Bingham County Historical Society.

Meanwhile, I ran across a surprising claim to fame for The Firth Record. In a retrospective published in the January 28, 1949 edition, the editor noted that one of the “extras” the paper had published drew “acclaim all over the nation, as the first to hit the streets, after the memorable Japanese surrender, marking the end of hostilities in a war torn world.”

Why? The editor explained. “Four months after the war’s end, The Firth Record was given national and international notoriety, with the announcement that it was the ‘firstest’ among the firsts. This was disclosed by the Publishers Auxiliary, a weekly newspaper published in Chicago.”

So, a Firth first. Further, the first Firthian to read the paper was Harold Brighton, who had it in his hands two minutes after it came off the press.

That moment of fame is gratifying to those of us from Firth who have endured jokes over the years such as, “Firth? Is that near Thecond?”

Published on December 06, 2024 04:00

December 5, 2024

An FBI Hero

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

All these years after their deaths, the names John Dillinger and “Baby Face” Nelson are familiar because of their infamy as crime figures. But an Idaho man you’ve probably never heard of was at least partly responsible for the demise of each.

Samuel P. Cowley was born in Franklin, Idaho in July 1899. He went to the Oneida Stake Academy, the Utah Agricultural College in Logan, Utah, and George Washington University in Washington, DC. He graduated from the latter with a law degree.

Cowley entered the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1929 as an agent and was promoted to inspector in 1934.

It was in July 1934 that a headline reading “Former Preston Man Helps Get Dillinger” ran on the front page of the Preston Citizen. Early reports said that it was Cowley’s bullet that ended the gangster’s life, but that wasn’t certain. Dillinger was gunned down after attending a picture show at the Biograph Theater in Chicago. The film he had been watching was Manhattan Melodrama starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, and William Powell.

Things went mostly right when Cowley participated in taking Dillinger down. Not so with “Baby Face” Nelson, whose real name was Lester Gillis.

Just months after the gunfight in Chicago, on November 27, 1934, Cowley and Special Agent Herman E. Hollis stopped Nelson’s car with gunfire. Nelson, and companion John Paul Chase came out of the crippled car shooting. Cowley and Hollis returned fire, hitting and severely wounding Nelson, who would die that evening. Unfortunately, both Cowley and Hollis were also shot. Hollis died that day. Cowley passed away the next morning. John Paul Chase was later captured, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison.

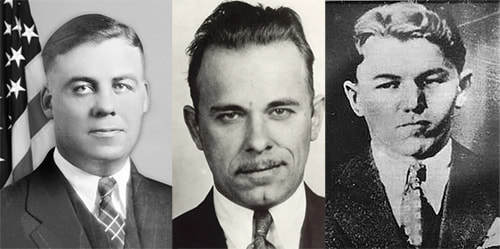

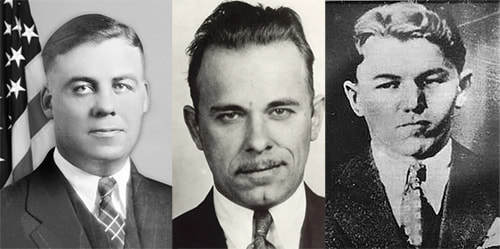

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

All these years after their deaths, the names John Dillinger and “Baby Face” Nelson are familiar because of their infamy as crime figures. But an Idaho man you’ve probably never heard of was at least partly responsible for the demise of each.

Samuel P. Cowley was born in Franklin, Idaho in July 1899. He went to the Oneida Stake Academy, the Utah Agricultural College in Logan, Utah, and George Washington University in Washington, DC. He graduated from the latter with a law degree.

Cowley entered the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1929 as an agent and was promoted to inspector in 1934.

It was in July 1934 that a headline reading “Former Preston Man Helps Get Dillinger” ran on the front page of the Preston Citizen. Early reports said that it was Cowley’s bullet that ended the gangster’s life, but that wasn’t certain. Dillinger was gunned down after attending a picture show at the Biograph Theater in Chicago. The film he had been watching was Manhattan Melodrama starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, and William Powell.

Things went mostly right when Cowley participated in taking Dillinger down. Not so with “Baby Face” Nelson, whose real name was Lester Gillis.

Just months after the gunfight in Chicago, on November 27, 1934, Cowley and Special Agent Herman E. Hollis stopped Nelson’s car with gunfire. Nelson, and companion John Paul Chase came out of the crippled car shooting. Cowley and Hollis returned fire, hitting and severely wounding Nelson, who would die that evening. Unfortunately, both Cowley and Hollis were also shot. Hollis died that day. Cowley passed away the next morning. John Paul Chase was later captured, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

Published on December 05, 2024 04:00

December 4, 2024

The Man Who Invented Idaho

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

I love odd little connections. Idaho has a ton of them with Abraham Lincoln. So many that they have become an obsession with Lincoln scholar and former Idaho Attorney General David Leroy.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

I love odd little connections. Idaho has a ton of them with Abraham Lincoln. So many that they have become an obsession with Lincoln scholar and former Idaho Attorney General David Leroy.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

Published on December 04, 2024 04:00

December 3, 2024

Sending Prisoners Out of State

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Prison overcrowding is often in the news as Idaho continues to send inmates out of state to serve their time. One might assume the practice is a fairly recent one. It is so only if you consider 1887 fairly recent.

That was the year Idaho sent its first convicts out of state. Well, out of territory. Idaho wouldn’t become a state for another three years. One can speculate on why they chose to do so, and, having just given myself permission, I’ll speculate that it was to provide an extra level of punishment for a crime that at that time was considered extra reprehensible. The five prisoners who were sent to the United States Penitentiary at Sioux Falls, Dakota Territory, on 4 December 1887, had been convicted of polygamy.

Austin Greeley Green, John Henry Byington, Sidney Weekes, William Sevins, and Josiah Richardson had the dubious honor of being the first men from Idaho to be sentenced to a prison in another territory. In a previous post I noted how aggressively Fred T. Dubois, then the U.S. Marshal of Idaho Territory, went after polygamists. It had proved difficult to convict on a charge of polygamy, even though congress made it a federal crime in 1862. Those practicing polygamy were not marrying multiple wives by going down to the local courthouse to get multiple marriage licenses. The marriages were recorded only in LDS church records, which were not open to the public.

In 1882, Congress passed the Edmunds Act. It enabled law enforcement to arrest men on charges of adultery and cohabitation. It was much easier to prove cohabitation than to prove that a man had multiple wives.

There were many disaffected former Mormons who were willing to serve on juries looking into polygamy, cohabitation, or whatever a prosecutor wanted to call it. For a while being charged was the same as being found guilty, such was the anti-Mormon fever running high in places such as Blackfoot, where the trial for the five was held. On November 14, 1887, a reporter for the Deseret Evening News wrote that “A ‘Mormon’ arrested and taken to Blackfoot stands convicted, and all he has to do is wait for the sentence.”

One result of this prosecutorial zeal was that the Idaho Territorial Penitentiary was filling up. Finding empty cells out of the territory where prisoners could be housed made some sense. Bonus: They could send convicted “cohabiters” far away from their families, inflicting a special punishment on them that was off the books.

The first five men sent to the penitentiary in Dakota Territory were reportedly docile prisoners who caused no trouble. Meanwhile, back in Idaho Territory, there was growing sentiment for their release. James Hawley, then the US Attorney for Idaho Territory looked into their case and recommended a pardon. On January 7, 1889, President Grover Cleveland pardoned the men. This did little to quell the anti-Mormon and anti-polygamy sentiment in Idaho. It would take a manifesto from the LDS church in 1890 stopping the practice of polygamy to cool things down.

The main building of Idaho’s old penitentiary in an undated photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

The main building of Idaho’s old penitentiary in an undated photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Prison overcrowding is often in the news as Idaho continues to send inmates out of state to serve their time. One might assume the practice is a fairly recent one. It is so only if you consider 1887 fairly recent.

That was the year Idaho sent its first convicts out of state. Well, out of territory. Idaho wouldn’t become a state for another three years. One can speculate on why they chose to do so, and, having just given myself permission, I’ll speculate that it was to provide an extra level of punishment for a crime that at that time was considered extra reprehensible. The five prisoners who were sent to the United States Penitentiary at Sioux Falls, Dakota Territory, on 4 December 1887, had been convicted of polygamy.

Austin Greeley Green, John Henry Byington, Sidney Weekes, William Sevins, and Josiah Richardson had the dubious honor of being the first men from Idaho to be sentenced to a prison in another territory. In a previous post I noted how aggressively Fred T. Dubois, then the U.S. Marshal of Idaho Territory, went after polygamists. It had proved difficult to convict on a charge of polygamy, even though congress made it a federal crime in 1862. Those practicing polygamy were not marrying multiple wives by going down to the local courthouse to get multiple marriage licenses. The marriages were recorded only in LDS church records, which were not open to the public.

In 1882, Congress passed the Edmunds Act. It enabled law enforcement to arrest men on charges of adultery and cohabitation. It was much easier to prove cohabitation than to prove that a man had multiple wives.

There were many disaffected former Mormons who were willing to serve on juries looking into polygamy, cohabitation, or whatever a prosecutor wanted to call it. For a while being charged was the same as being found guilty, such was the anti-Mormon fever running high in places such as Blackfoot, where the trial for the five was held. On November 14, 1887, a reporter for the Deseret Evening News wrote that “A ‘Mormon’ arrested and taken to Blackfoot stands convicted, and all he has to do is wait for the sentence.”

One result of this prosecutorial zeal was that the Idaho Territorial Penitentiary was filling up. Finding empty cells out of the territory where prisoners could be housed made some sense. Bonus: They could send convicted “cohabiters” far away from their families, inflicting a special punishment on them that was off the books.

The first five men sent to the penitentiary in Dakota Territory were reportedly docile prisoners who caused no trouble. Meanwhile, back in Idaho Territory, there was growing sentiment for their release. James Hawley, then the US Attorney for Idaho Territory looked into their case and recommended a pardon. On January 7, 1889, President Grover Cleveland pardoned the men. This did little to quell the anti-Mormon and anti-polygamy sentiment in Idaho. It would take a manifesto from the LDS church in 1890 stopping the practice of polygamy to cool things down.

The main building of Idaho’s old penitentiary in an undated photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

The main building of Idaho’s old penitentiary in an undated photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Published on December 03, 2024 04:00