Rick Just's Blog, page 5

December 2, 2024

A Park, Finally

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Thomas Jefferson Davis was a persistent man. One of the founders of Boise, he gave up his dreams of striking it rich in mining and put his money into agriculture. A growing population needed fruit more than it needed gold. He planted 7,000 apple trees along the Boise River.

One of his visions for the city he helped create was for a stately park near the center of town. He first broached the subject by offering 40 acres of his land for that purpose in 1899. The city council referred the matter to the “committee on flumes and gulches,” where it died.

Tom Davis and his wife Julia, brought the subject up again in 1907 without generating much interest. Sadly, Mrs. Davis died later that year. That was apparently enough for the city council to focus on the offer. They accepted the park that year and agreed to name it after Davis’s late wife, Julia.

Julia Davis Park has been the flagship of the park system in the city ever since, serving as the first pearl in the “string of pearls” parks along the Boise River in the heart of the city. The statue of Julia Davis in her namesake park.

The statue of Julia Davis in her namesake park.

Thomas Jefferson Davis was a persistent man. One of the founders of Boise, he gave up his dreams of striking it rich in mining and put his money into agriculture. A growing population needed fruit more than it needed gold. He planted 7,000 apple trees along the Boise River.

One of his visions for the city he helped create was for a stately park near the center of town. He first broached the subject by offering 40 acres of his land for that purpose in 1899. The city council referred the matter to the “committee on flumes and gulches,” where it died.

Tom Davis and his wife Julia, brought the subject up again in 1907 without generating much interest. Sadly, Mrs. Davis died later that year. That was apparently enough for the city council to focus on the offer. They accepted the park that year and agreed to name it after Davis’s late wife, Julia.

Julia Davis Park has been the flagship of the park system in the city ever since, serving as the first pearl in the “string of pearls” parks along the Boise River in the heart of the city.

The statue of Julia Davis in her namesake park.

The statue of Julia Davis in her namesake park.

Published on December 02, 2024 04:00

December 1, 2024

A Famous Sea Dog in Idaho

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

The most famous dog in Idaho history was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Meriwether Lewis paid $20 for him in August 1803. The Newfoundland was an uncommon breed at the time, but some of its characteristics were well known. A male typically weighs around 150 pounds. They are known as great swimmers, and built for it with a double coat to keep them warm and webbed feet. The dogs were favorites of sailors, which is probably why Lewis named his Seaman.

For decades people thought the dog’s name was Scannon because making out Lewis’ handwriting was always a challenge. However, in 1984 a researcher discovered a clear reference to Seaman Creek, named after the dog.

Seaman proved his value to the Corps of Discovery early on. The men encountered what seemed to be a mass migration of squirrels on the Ohio River, September 11, 1803. Lewis commanded the dog to get a squirrel. He jumped right in, grabbed one, and brought it back. He kept jumping in and retrieving squirrels until they had enough for a meal. “They wer fat and I thought them when fryed a pleasant food,” Lewis wrote.

Later, while on the Mississippi, Lewis refused an offer for Seaman. He wrote, “One of the Shawnees a respectable looking Indian offered me three beverskins for my dog with which he appeared much pleased, the dog was of the newfoundland breed one that I prised much for his docility and qualifications generally for my journey and of course there was no bargan.”

The members of the Corps of Discovery soon learned to trust Seaman’s superior senses. He could tell when hunting parties were returning to camp or when a stranger was approaching. He got excited when he smelled bison. Seaman often accompanied Lewis on hunts, sometimes retrieving game he had shot.

Though Seaman was a skilled squirrel chaser he had no luck with prairie dogs. He loved to chase them but they always darted into burrow before his jaws could snap shut around them.

When the Corps of Discovery finally entered present day Idaho on August 12, 1805, Seaman was there. He was there, too, laing beside little “Pomp” on August 17 when Sacajawea was reunited with her brother. He was probably the only member of the party that was happy to see the snow fall in early September when they were short of food. The dog romped and played in it, insulated from any thought of cold by his thick coat.

As the men came closer to starvation, some may have eyed the dog as a possible source of food. No one would dare bring it up with Lewis, though the expedition did dine on some 200 dogs during their trek.

Meeting up with the Nez Perce later in the month solved the hunger problem. The canoes the expedition built on the Clearwater gave the dog a chance to skim across the water in the bow of one, or splash and play when they stopped to camp.

The dog was briefly stolen by Clatsop Indians when the expedition was working its way up the Columbia on the way back to home. They released Seaman when they saw they were being pursued.

Oddly, what ultimately happened to Seaman is a mystery. Newfoundlands live only eight or 10 years, but we have no record of when he died. The last mention of him in Lewis’ journal was on July 14, 1806 when he noted that mosquitos were terrible and that “My dog even howl’s with the torture he experiences from them.”

One clue seems to bolster the notion that he made it all the way back with the Corps of Discovery. A large dog collar on display in a Virginia museum has a plate on it with the inscription "The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacific ocean through the interior of the continent of North America."

There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

The most famous dog in Idaho history was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Meriwether Lewis paid $20 for him in August 1803. The Newfoundland was an uncommon breed at the time, but some of its characteristics were well known. A male typically weighs around 150 pounds. They are known as great swimmers, and built for it with a double coat to keep them warm and webbed feet. The dogs were favorites of sailors, which is probably why Lewis named his Seaman.

For decades people thought the dog’s name was Scannon because making out Lewis’ handwriting was always a challenge. However, in 1984 a researcher discovered a clear reference to Seaman Creek, named after the dog.

Seaman proved his value to the Corps of Discovery early on. The men encountered what seemed to be a mass migration of squirrels on the Ohio River, September 11, 1803. Lewis commanded the dog to get a squirrel. He jumped right in, grabbed one, and brought it back. He kept jumping in and retrieving squirrels until they had enough for a meal. “They wer fat and I thought them when fryed a pleasant food,” Lewis wrote.

Later, while on the Mississippi, Lewis refused an offer for Seaman. He wrote, “One of the Shawnees a respectable looking Indian offered me three beverskins for my dog with which he appeared much pleased, the dog was of the newfoundland breed one that I prised much for his docility and qualifications generally for my journey and of course there was no bargan.”

The members of the Corps of Discovery soon learned to trust Seaman’s superior senses. He could tell when hunting parties were returning to camp or when a stranger was approaching. He got excited when he smelled bison. Seaman often accompanied Lewis on hunts, sometimes retrieving game he had shot.

Though Seaman was a skilled squirrel chaser he had no luck with prairie dogs. He loved to chase them but they always darted into burrow before his jaws could snap shut around them.

When the Corps of Discovery finally entered present day Idaho on August 12, 1805, Seaman was there. He was there, too, laing beside little “Pomp” on August 17 when Sacajawea was reunited with her brother. He was probably the only member of the party that was happy to see the snow fall in early September when they were short of food. The dog romped and played in it, insulated from any thought of cold by his thick coat.

As the men came closer to starvation, some may have eyed the dog as a possible source of food. No one would dare bring it up with Lewis, though the expedition did dine on some 200 dogs during their trek.

Meeting up with the Nez Perce later in the month solved the hunger problem. The canoes the expedition built on the Clearwater gave the dog a chance to skim across the water in the bow of one, or splash and play when they stopped to camp.

The dog was briefly stolen by Clatsop Indians when the expedition was working its way up the Columbia on the way back to home. They released Seaman when they saw they were being pursued.

Oddly, what ultimately happened to Seaman is a mystery. Newfoundlands live only eight or 10 years, but we have no record of when he died. The last mention of him in Lewis’ journal was on July 14, 1806 when he noted that mosquitos were terrible and that “My dog even howl’s with the torture he experiences from them.”

One clue seems to bolster the notion that he made it all the way back with the Corps of Discovery. A large dog collar on display in a Virginia museum has a plate on it with the inscription "The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacific ocean through the interior of the continent of North America."

There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

Published on December 01, 2024 04:00

November 30, 2024

Manley's

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Idaho Statesman writer Anna Webb said this about Manley’s Café in a 2006 article: “Manley´s was famous for the size of its servings: ham slices bigger than the plate they were on and pieces of pie with enough a la mode to fill three ice cream cones.”

Manley’s was not famous for its lavish menu, or its white tablecloths, or its wine list. It didn’t have any of those things. It did have a rickety screen door, plastic burger baskets, a Wrigley’s gum rack, leatherette stools, and a linoleum pattern worn away to nothing by thousands of feet. Manley’s had good food and plenty of it.

The original name of the café was Manley’s Garden Café, then Manley’s Rose Garden Café. Outdoor seating was available for a time if one wanted to enjoy the roses. The garden eventually became not so garden-ish, and the outdoor seating went away.

The owners were Manley Morrow and his wife Marjorie. They opened the place in 1954. Marjorie passed away in January of 1960, leaving Manley to run it himself.

Manley was philosophically against having anyone that came through the door leaving hungry. Order a piece of pie and you got a quarter of a pie. Do you want that ala mode? Manley or one of his crew would plop a pint of ice cream on top of it.

Some famous folk stopped by Manley’s. Many Idaho governors ate there, as did a future president. John F. Kennedy was said to have stopped by when he was running for president. Tim Woodward, long-time reporter and columnist, remembered the time when he took New Yorker writer and food critic Calvin Trillin to Manley’s. In an April 18, 2013 piece in the Idaho Statesman, Woodward quoted Trillin as saying, "Every town I go to, they take me to the restaurant in the glass ball on the top floor of the tallest building in town," he said. "The prices are outrageous, and the food is awful. This place is great!"

Manley Morrow passed away in 1976. His son, David, took over and ran the place for a while, then sold it to a couple of the Manley’s waitresses. They ran it until 1997 when it closed for good. The site of the café is now Terry Day Park at 1225 Federal Way.

Idaho Statesman writer Anna Webb said this about Manley’s Café in a 2006 article: “Manley´s was famous for the size of its servings: ham slices bigger than the plate they were on and pieces of pie with enough a la mode to fill three ice cream cones.”

Manley’s was not famous for its lavish menu, or its white tablecloths, or its wine list. It didn’t have any of those things. It did have a rickety screen door, plastic burger baskets, a Wrigley’s gum rack, leatherette stools, and a linoleum pattern worn away to nothing by thousands of feet. Manley’s had good food and plenty of it.

The original name of the café was Manley’s Garden Café, then Manley’s Rose Garden Café. Outdoor seating was available for a time if one wanted to enjoy the roses. The garden eventually became not so garden-ish, and the outdoor seating went away.

The owners were Manley Morrow and his wife Marjorie. They opened the place in 1954. Marjorie passed away in January of 1960, leaving Manley to run it himself.

Manley was philosophically against having anyone that came through the door leaving hungry. Order a piece of pie and you got a quarter of a pie. Do you want that ala mode? Manley or one of his crew would plop a pint of ice cream on top of it.

Some famous folk stopped by Manley’s. Many Idaho governors ate there, as did a future president. John F. Kennedy was said to have stopped by when he was running for president. Tim Woodward, long-time reporter and columnist, remembered the time when he took New Yorker writer and food critic Calvin Trillin to Manley’s. In an April 18, 2013 piece in the Idaho Statesman, Woodward quoted Trillin as saying, "Every town I go to, they take me to the restaurant in the glass ball on the top floor of the tallest building in town," he said. "The prices are outrageous, and the food is awful. This place is great!"

Manley Morrow passed away in 1976. His son, David, took over and ran the place for a while, then sold it to a couple of the Manley’s waitresses. They ran it until 1997 when it closed for good. The site of the café is now Terry Day Park at 1225 Federal Way.

Published on November 30, 2024 04:00

November 29, 2024

The Last Indian War

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Indians fought losing wars with the United States Government for years during the settlement of the West. They fought for their way of life, their traditions, and mostly for their land.

What might have been the last Indian war was about land, too. No bullets were fired, nor arrows unleashed. The war was declared by a woman, Amy Trice, the chair of the Kootenai Tribe, on September 20, 1974.

The Kootenai had been unrepresented at the signing of the Treaty of Hellgate of 1855. Never-the-less that treaty took away any claim they had to their aboriginal lands and without compensation. They had no reservation.

That lack of representation was something of a Catch 22. Most tribes in the United States are prohibited from declaring war on the country, a clause laid out in multiple treaties. But the Kootenai had never signed a treaty. They weren’t even recognized as a tribe by the U.S.

So, after living in grinding poverty with no land base for 120 years, war it was. To underscore their claim of aboriginal lands, the Kootenai began waving cars over and collecting a voluntary fee of 10 cents to cross their lands on the highway north and south of Bonners Ferry. There was much local resentment of the action and rumors of weaponry being smuggled to the Indians. Members from several tribes began gathering near Bonners Ferry in support of the Kootenai.

The 67-member tribe suggested they would soon begin charging a 50 cent per day business tax and 10 cents per day for dwellings situated on their aboriginal lands.

The Kootenai’s call it a “War of the pen.” The publicity gained by declaring war and charging tolls got the attention of the press, the public, and politicians more than anything the Tribe had tried. In the end, President Gerald Ford signed legislation granting the Tribe 12.5 acres of land surrounding a mission. In the Hellgate Treaty, an estimated 1.6 million acres of land had been taken from the Kootenai.

The 12.5 acres doesn’t seem like much, but it gave the Kootenai a reservation and the legislation recognized the Tribe, clearing the way for eligibility for some government funding. Today, the Kootenai Tribe holds about 2,500 acres of land. They are dedicated to habitat restoration, particularly for sturgeon and burbot.

Amy Trice, the woman who declared war against the U.S., passed away in 2011 at age 75, a heroine to her people.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

Indians fought losing wars with the United States Government for years during the settlement of the West. They fought for their way of life, their traditions, and mostly for their land.

What might have been the last Indian war was about land, too. No bullets were fired, nor arrows unleashed. The war was declared by a woman, Amy Trice, the chair of the Kootenai Tribe, on September 20, 1974.

The Kootenai had been unrepresented at the signing of the Treaty of Hellgate of 1855. Never-the-less that treaty took away any claim they had to their aboriginal lands and without compensation. They had no reservation.

That lack of representation was something of a Catch 22. Most tribes in the United States are prohibited from declaring war on the country, a clause laid out in multiple treaties. But the Kootenai had never signed a treaty. They weren’t even recognized as a tribe by the U.S.

So, after living in grinding poverty with no land base for 120 years, war it was. To underscore their claim of aboriginal lands, the Kootenai began waving cars over and collecting a voluntary fee of 10 cents to cross their lands on the highway north and south of Bonners Ferry. There was much local resentment of the action and rumors of weaponry being smuggled to the Indians. Members from several tribes began gathering near Bonners Ferry in support of the Kootenai.

The 67-member tribe suggested they would soon begin charging a 50 cent per day business tax and 10 cents per day for dwellings situated on their aboriginal lands.

The Kootenai’s call it a “War of the pen.” The publicity gained by declaring war and charging tolls got the attention of the press, the public, and politicians more than anything the Tribe had tried. In the end, President Gerald Ford signed legislation granting the Tribe 12.5 acres of land surrounding a mission. In the Hellgate Treaty, an estimated 1.6 million acres of land had been taken from the Kootenai.

The 12.5 acres doesn’t seem like much, but it gave the Kootenai a reservation and the legislation recognized the Tribe, clearing the way for eligibility for some government funding. Today, the Kootenai Tribe holds about 2,500 acres of land. They are dedicated to habitat restoration, particularly for sturgeon and burbot.

Amy Trice, the woman who declared war against the U.S., passed away in 2011 at age 75, a heroine to her people.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

Published on November 29, 2024 04:00

November 28, 2024

We Want Alta, We Want Alta!

Idaho’s boundaries have been a little fluid during its short history. I’ve written about it here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and now here. One could argue that today’s border story is about one stubbornly solid border.

Alta, Wyoming is home to one of Idaho’s 18 ski areas. Look it up. Grand Targhee is on the Wyoming side of the border, but it’s accessible only from Idaho. According to current census estimates, some 600 residents live in Alta, though the official population lists only 294 counted in 2020.

The area was a part of Idaho at one time, but when they carved up the too-big territory of Idaho in 1868 to make the still very large territory of Wyoming, Idaho lost a few things. It lost what would become Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park, and much uninhabited land that would one day include Alta.

Some nameless Congressman at the time said, “there is not a single inhabitant in that portion of Idaho transferred by this bill.” That was probably close to true if you weren’t counting Indians as inhabitants.

The people who settled Alta weren’t wild about being in Wyoming. A memorial from the Idaho Legislature in 1897 made an argument for annexing the area:

“That that portion of the drainage of Teton River which is situated in the State of Wyoming contains an area of approximately 300 square miles, of which about 10 square miles is agricultural land and the balance is mountainous; that there are twenty-five families residing on said area; that the county seat of Uintah County, in which said areas is situate [sic], is Evanston, more than 300 miles distant by the usual route of travel; that said usual route of travel extends through Fremont, Bingham, Bannock, and Oneida counties in Idaho, and Cache, Boxelder, Weber, Morgan, and Summit counties in Utah; that the Teton range of mountains, forming the eastern boundary of said area, is an impassable barrier; that the interests and business of the people residing in said area are entirely with Fremont County in Idaho; that the present situation imposes many annoyances and unnecessary hardships upon said residents without in any manner benefiting the State of Wyoming; that no injury can result to the State of Wyoming from the annexation of said area to the State of Idaho; that the said residents are all in favor of such annexation, that the following is a description of said area:”

And the resolution went on to describe the area. The reply from Washington, DC upon receipt of the memorial, was, “talk to us when you learn how to use periods.”

No, I’m joking; the reply was the sound of crickets.

A few years later, in 1903, Alta-ites learned that a very early mistake in locating the American Meridian was keeping them in Wyoming. Changing that meridian would move the Idaho border about 2.29 miles to the east. Voila! Problem solved!

But Congress, content in its own infallibility, was not moved to move the border. It took them nearly 30 years to appoint a commission on the subject, which concluded that it wasn’t worth the trouble it would cause to rejigger the Idaho/Wyoming border.

By that time, residents of Alta, Wyoming—you know how those Wyomingites are—decided they were happy enough staying in Wyoming, anyway. By that time, their county seat was in Jackson, Wyoming, only 34 miles away.

Alta, Wyoming is home to one of Idaho’s 18 ski areas. Look it up. Grand Targhee is on the Wyoming side of the border, but it’s accessible only from Idaho. According to current census estimates, some 600 residents live in Alta, though the official population lists only 294 counted in 2020.

The area was a part of Idaho at one time, but when they carved up the too-big territory of Idaho in 1868 to make the still very large territory of Wyoming, Idaho lost a few things. It lost what would become Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park, and much uninhabited land that would one day include Alta.

Some nameless Congressman at the time said, “there is not a single inhabitant in that portion of Idaho transferred by this bill.” That was probably close to true if you weren’t counting Indians as inhabitants.

The people who settled Alta weren’t wild about being in Wyoming. A memorial from the Idaho Legislature in 1897 made an argument for annexing the area:

“That that portion of the drainage of Teton River which is situated in the State of Wyoming contains an area of approximately 300 square miles, of which about 10 square miles is agricultural land and the balance is mountainous; that there are twenty-five families residing on said area; that the county seat of Uintah County, in which said areas is situate [sic], is Evanston, more than 300 miles distant by the usual route of travel; that said usual route of travel extends through Fremont, Bingham, Bannock, and Oneida counties in Idaho, and Cache, Boxelder, Weber, Morgan, and Summit counties in Utah; that the Teton range of mountains, forming the eastern boundary of said area, is an impassable barrier; that the interests and business of the people residing in said area are entirely with Fremont County in Idaho; that the present situation imposes many annoyances and unnecessary hardships upon said residents without in any manner benefiting the State of Wyoming; that no injury can result to the State of Wyoming from the annexation of said area to the State of Idaho; that the said residents are all in favor of such annexation, that the following is a description of said area:”

And the resolution went on to describe the area. The reply from Washington, DC upon receipt of the memorial, was, “talk to us when you learn how to use periods.”

No, I’m joking; the reply was the sound of crickets.

A few years later, in 1903, Alta-ites learned that a very early mistake in locating the American Meridian was keeping them in Wyoming. Changing that meridian would move the Idaho border about 2.29 miles to the east. Voila! Problem solved!

But Congress, content in its own infallibility, was not moved to move the border. It took them nearly 30 years to appoint a commission on the subject, which concluded that it wasn’t worth the trouble it would cause to rejigger the Idaho/Wyoming border.

By that time, residents of Alta, Wyoming—you know how those Wyomingites are—decided they were happy enough staying in Wyoming, anyway. By that time, their county seat was in Jackson, Wyoming, only 34 miles away.

Published on November 28, 2024 04:00

November 27, 2024

The Kooskia Internment Camp

Beginning January 1, Speaking of Idaho will become a subscription service. Watch for details over the next few weeks.

You probably know something about the Minidoka Internment Camp, sometimes called the Hunt Camp that was located near Jerome, Idaho, now the Minidoka National Historic Site.

Did you know there was a second Japanese internment camp in Idaho?

The Kooskia Internment Camp was located about 30 miles east of Kooskia on Canyon Creek. The men housed there—and they were all men—worked on the construction of U.S. Highway 12.

The Kooskia camp was unique among camps in the U.S. in that those housed there volunteered for the assignment. They were men of Japanese ancestry who had been placed in other internment camps, but who had volunteered to go to Kooskia because they received wages of between $55 and $65 a month. The camp’s remote location meant there was not even the need for a fence around the Canyon Creek site.

A total of 256 men spent time working at the camp between May 1943 and May 1945. After the war and with the completion of Highway 12, there was no need for the site. The buildings “walked” away or were torn down. Today, only a concrete slab marks the site of the camp, which is on the Clearwater National Forest.

Some archaeological research has been done at the Kooskia Internment Camp, and Priscilla Wegars, PhD, has written extensively about the site. Her book As Rugged As The Terrain: CCC "Boys," Federal Convicts, And Alien Internees Wrestle With A Mountain Wilderness contains a detailed story of the camp as well as camps of different types in Idaho.

You probably know something about the Minidoka Internment Camp, sometimes called the Hunt Camp that was located near Jerome, Idaho, now the Minidoka National Historic Site.

Did you know there was a second Japanese internment camp in Idaho?

The Kooskia Internment Camp was located about 30 miles east of Kooskia on Canyon Creek. The men housed there—and they were all men—worked on the construction of U.S. Highway 12.

The Kooskia camp was unique among camps in the U.S. in that those housed there volunteered for the assignment. They were men of Japanese ancestry who had been placed in other internment camps, but who had volunteered to go to Kooskia because they received wages of between $55 and $65 a month. The camp’s remote location meant there was not even the need for a fence around the Canyon Creek site.

A total of 256 men spent time working at the camp between May 1943 and May 1945. After the war and with the completion of Highway 12, there was no need for the site. The buildings “walked” away or were torn down. Today, only a concrete slab marks the site of the camp, which is on the Clearwater National Forest.

Some archaeological research has been done at the Kooskia Internment Camp, and Priscilla Wegars, PhD, has written extensively about the site. Her book As Rugged As The Terrain: CCC "Boys," Federal Convicts, And Alien Internees Wrestle With A Mountain Wilderness contains a detailed story of the camp as well as camps of different types in Idaho.

Published on November 27, 2024 04:00

November 26, 2024

How Much Coal?

Seeing this 1939 photo of a steam locomotive pulling into Glenns Ferry caused me to wonder about how much coal was used by your average train. As it turns out, it’s a bit like asking how much wood could a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood.

The answer is it depends. It depends on the engine's size, the coal's grade, the terrain's steepness, and how much tonnage the locomotive pulls. Temperature was also a factor. If it was winter, passenger trains were heated by steam the locomotive generated, making them less efficient at pulling.

I found some comments on the trusty internet from a former locomotive engineer for Union Pacific who said coal-powered trains typically made stops every hundred miles or so to load up with more coal. Of course, that depends, too. It depends on the size of the tender and all the other “depends” listed above. The same engineer noted that trains had to stop twice as often to take on water, which was just as important as coal.

And what about the guy shoveling the coal? Did he ever get a break? Not really. You didn’t want to put too much coal on at once or it wouldn’t burn efficiently. Experienced firemen would lift six to nine shovels full and dump them into the burner.

Now that I’ve given you almost no information you can really count on, I’m going to trust that some of the train fanatics who read these posts will set me straight. I’m looking at you, John Wood!

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

The answer is it depends. It depends on the engine's size, the coal's grade, the terrain's steepness, and how much tonnage the locomotive pulls. Temperature was also a factor. If it was winter, passenger trains were heated by steam the locomotive generated, making them less efficient at pulling.

I found some comments on the trusty internet from a former locomotive engineer for Union Pacific who said coal-powered trains typically made stops every hundred miles or so to load up with more coal. Of course, that depends, too. It depends on the size of the tender and all the other “depends” listed above. The same engineer noted that trains had to stop twice as often to take on water, which was just as important as coal.

And what about the guy shoveling the coal? Did he ever get a break? Not really. You didn’t want to put too much coal on at once or it wouldn’t burn efficiently. Experienced firemen would lift six to nine shovels full and dump them into the burner.

Now that I’ve given you almost no information you can really count on, I’m going to trust that some of the train fanatics who read these posts will set me straight. I’m looking at you, John Wood!

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on November 26, 2024 04:00

November 25, 2024

Did You Ever Hear of a Baldheaded Indian?

It’s doubtful Idaho has more than an average number of bald men and women. But the state has produced more than its share of solutions for that balding.

U.S. Senator Glenn Taylor invented the Taylor Topper, a high-quality hairpiece after he left the Senate. His company is still in the family. The Topper came out in the 1950s, long after Idaho’s first attempt at presenting full heads of hair to everyone.

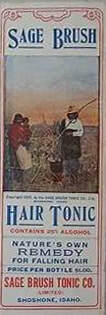

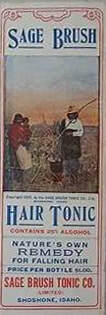

With the slogan, “Did you ever hear of a baldheaded Indian,” the Sage Brush Tonic Company LTD began in Shoshone in 1907. The original directors were F.W. Whittington, Frank Milsap, Thomas Starrh, Fred W. Gooding, and E. Walters, all of Shoshone, and Fred R. Reed of American Falls.

Although baldheaded Indians do exist (male pattern baldness is rare in Native Americans), the tonic was proclaimed “The Indians’ Gift to the White Man.” The brochure that came with every bottle shows an Indian man and woman brewing a pot of sagebrush tonic in a pot over a small fire.

In 1909, the Richfield Recorder reported that the “process (was) to gather the tender tips of the sage plant, at the time of blooming in early summer and cure them until the atmosphere dries out most of the water, then steam and boil them to extract the essential oils of the sage.” The paper reported that it was an old remedy used for ages by Idaho Indians.

The company went big from the beginning, constructing a factory on Rail Street and ordering 75,000 bottles in various sizes before the locals (“a good-sized force”) were hired at $2 a day to gather the sage leaves.

Manufacturing the tonic didn’t cost much. The finished liquid ran $1.71 a gallon, or 26 cents for a small bottle. Transportation was the killer, though. Even with the railroad running right by the factory, getting the bottles out to balding people all over the country proved too expensive. The company shuttered in 1910.

Sage Brush Hair Tonic came in graceful bottles that, if left in the sun, turned a lovely amethyst.

Sage Brush Hair Tonic came in graceful bottles that, if left in the sun, turned a lovely amethyst.  This brochure came packed with every bottle.

This brochure came packed with every bottle.

U.S. Senator Glenn Taylor invented the Taylor Topper, a high-quality hairpiece after he left the Senate. His company is still in the family. The Topper came out in the 1950s, long after Idaho’s first attempt at presenting full heads of hair to everyone.

With the slogan, “Did you ever hear of a baldheaded Indian,” the Sage Brush Tonic Company LTD began in Shoshone in 1907. The original directors were F.W. Whittington, Frank Milsap, Thomas Starrh, Fred W. Gooding, and E. Walters, all of Shoshone, and Fred R. Reed of American Falls.

Although baldheaded Indians do exist (male pattern baldness is rare in Native Americans), the tonic was proclaimed “The Indians’ Gift to the White Man.” The brochure that came with every bottle shows an Indian man and woman brewing a pot of sagebrush tonic in a pot over a small fire.

In 1909, the Richfield Recorder reported that the “process (was) to gather the tender tips of the sage plant, at the time of blooming in early summer and cure them until the atmosphere dries out most of the water, then steam and boil them to extract the essential oils of the sage.” The paper reported that it was an old remedy used for ages by Idaho Indians.

The company went big from the beginning, constructing a factory on Rail Street and ordering 75,000 bottles in various sizes before the locals (“a good-sized force”) were hired at $2 a day to gather the sage leaves.

Manufacturing the tonic didn’t cost much. The finished liquid ran $1.71 a gallon, or 26 cents for a small bottle. Transportation was the killer, though. Even with the railroad running right by the factory, getting the bottles out to balding people all over the country proved too expensive. The company shuttered in 1910.

Sage Brush Hair Tonic came in graceful bottles that, if left in the sun, turned a lovely amethyst.

Sage Brush Hair Tonic came in graceful bottles that, if left in the sun, turned a lovely amethyst.  This brochure came packed with every bottle.

This brochure came packed with every bottle.

Published on November 25, 2024 04:00

November 24, 2024

"Fearless" Fosdick and Farris

This is a little-known tidbit that I discovered while working on my book about “Fearless” Farris Lind, his Stinker Stations, and the quirky signs that were their signature advertising scheme during the 40s, 50s, and into the 60s.

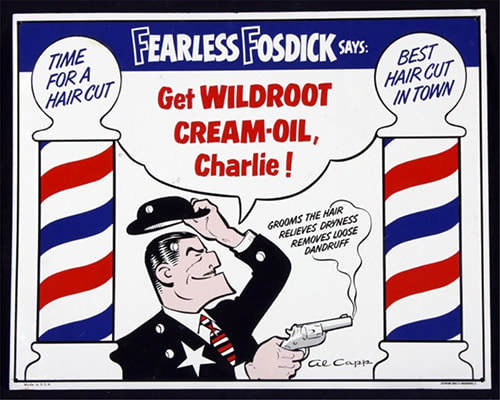

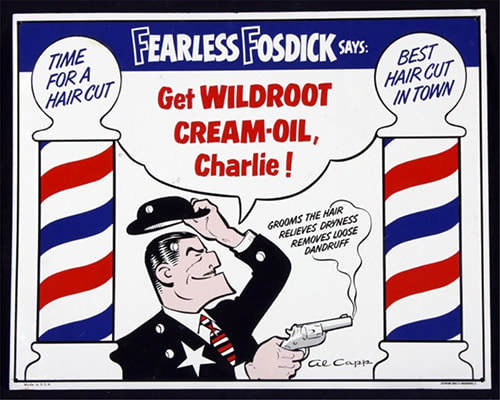

Given that Farris Lind was a Navy fighter pilot instructor during World War II, and later a crop duster, one might assume that’s where he got the nickname Fearless Farris. Not so. Lind got the idea for the name from Fearless Fosdick, the cartoon character Al Capp drew as a parody of Dick Tracy. Lind knew the alliteration would make it easy to remember. He invented the story that he was Fearless Farris because the “big guy” oil companies didn’t scare him. The first neon sign for his Boise service station featured a boxer under the words “Fearless Farris.”

The iconic skunk, also a boxer, would come along later when a competitor called Lind a “stinker” for his cut-rate prices for gasoline. Was Lind insulted? Oh, gosh, no. He latched onto that name like a leg trap. His growing chain of outlets became Stinker Stations with a boxing skunk logo.

Given that Farris Lind was a Navy fighter pilot instructor during World War II, and later a crop duster, one might assume that’s where he got the nickname Fearless Farris. Not so. Lind got the idea for the name from Fearless Fosdick, the cartoon character Al Capp drew as a parody of Dick Tracy. Lind knew the alliteration would make it easy to remember. He invented the story that he was Fearless Farris because the “big guy” oil companies didn’t scare him. The first neon sign for his Boise service station featured a boxer under the words “Fearless Farris.”

The iconic skunk, also a boxer, would come along later when a competitor called Lind a “stinker” for his cut-rate prices for gasoline. Was Lind insulted? Oh, gosh, no. He latched onto that name like a leg trap. His growing chain of outlets became Stinker Stations with a boxing skunk logo.

Published on November 24, 2024 04:00

November 23, 2024

Andrew Henry

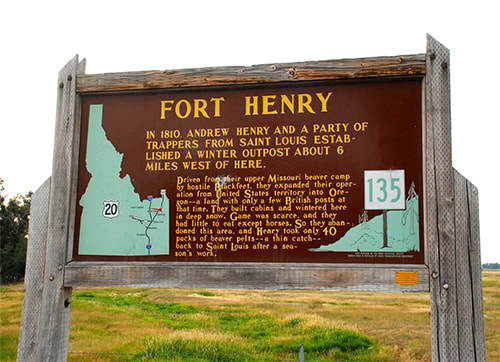

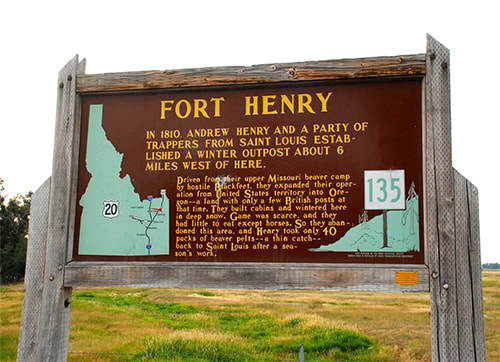

Andrew Henry’s name is all over Southeastern Idaho, all because he spent a hard winter near present-day St. Anthony. Henry and his men were on a trapping expedition, hoping to find a good supply of rodent fur they could liberate from beavers on account of the beavers being dead and all. Felt hats were all the rage.

The Henry party had been in present-day Montana on the upper Missouri on a quest for the slap-tails, but Blackfeet Indians had driven the trappers across the divide at Targhee Pass. They found a location near what would later be called the Henrys Fork of the Snake River, not far from what would later be called Henrys Flat at the foot of the Henrys Lake Mountains, near Henrys Lake, on the shores of which Henrys Lake State Park would one day be. They went about constructing a few cabins for the coming winter.

That winter of 1810 was a rough one for the trappers. The cold had driven buffalo south, so they found little game. The Henry party was reduced to eating some of their horses.

The next spring, they headed back to St. Louis with only 40 packs of pelts which, as everyone knows, was meager for a whole season of trapping.

The buildings they left behind would be much appreciated by the Wilson Price Hunt party the very next winter. They stayed there on their ill-fated trip to Fort Astoria in 1811.

Today, there’s an Idaho State Historical Marker a few miles from the site, and the City of St, Anthony has a monument downtown commemorating what the members of the Henry Party probably thought of it as something like, “the winter we ate Sea Biscuit.”

The Henry party had been in present-day Montana on the upper Missouri on a quest for the slap-tails, but Blackfeet Indians had driven the trappers across the divide at Targhee Pass. They found a location near what would later be called the Henrys Fork of the Snake River, not far from what would later be called Henrys Flat at the foot of the Henrys Lake Mountains, near Henrys Lake, on the shores of which Henrys Lake State Park would one day be. They went about constructing a few cabins for the coming winter.

That winter of 1810 was a rough one for the trappers. The cold had driven buffalo south, so they found little game. The Henry party was reduced to eating some of their horses.

The next spring, they headed back to St. Louis with only 40 packs of pelts which, as everyone knows, was meager for a whole season of trapping.

The buildings they left behind would be much appreciated by the Wilson Price Hunt party the very next winter. They stayed there on their ill-fated trip to Fort Astoria in 1811.

Today, there’s an Idaho State Historical Marker a few miles from the site, and the City of St, Anthony has a monument downtown commemorating what the members of the Henry Party probably thought of it as something like, “the winter we ate Sea Biscuit.”

Published on November 23, 2024 04:00