Rick Just's Blog, page 3

December 22, 2024

You Do that Hoodoo that You Do so Well

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

One day I was browsing through the Twenty-Third Biennial Report of the State Historical Society of Idaho published in 1922, as one does. It caught my attention that the report listed all the monuments in Idaho and associated with Idaho at the time. I skimmed through the list and descriptions to see if there might be blog fodder. Indeed. I will victimize you further with future posts but will restrain myself to a single monument for this one.

In fact, I’ll give only cursory attention to the monument mentioned because searching for more information on it led me down a path that with liberal use of unnecessary words will in itself be a blog.

See. I’ve already written 115 words without getting to the point. But I digress. But you knew that.

The monument that I wanted to research was the Sheepeater Monument. That monument, which I’ll tell you about in another post, was located near where Big Creek runs into the Salmon River. It’s a story worthy of a blog post, which I have already promised.

But today’s post, the one you’re reading, which has now run to 191 words without even approaching its subject, is about a “monument” I found while trying to do a little research on the aforementioned Sheepeater Monument.

Breaking out my copy of the trusty internet I did a Google image search for Sheepeater Monument, Idaho. What came up was an oddly shaped rock. It was actually more of a hoodoo which, now that the little ones have nodded off, I can proceed to describe.

The hoodoo in question, which was sometimes called Sheepeater’s Monument, is, as technical jargon would have it, really, really tall. I found a reference that said 70 feet. I don’t know. Photos show it towering over nearby trees. It is undeniably… let’s say tree-like, in that it is tall and narrow, but without the limbs one would usually find on a tall pine. A pole then. It’s like a pole. Eons ago some force, probably water followed later by wind, wore away layers of rock around it leaving a shaft of rock. And, to top it off, there is a large boulder resting impossibly on the summit of the hoodoo.

The formation has had some colorful names that I will leave up to you to imagine. It has a smaller pair of hoodoo companions nearby. This grouping of rude rocks at the head of Monumental Creek in Valley County is apparently why the creek is called that. We can be thankful for this unusual display of modesty on the part of the person who named it.

Photos of the formation are rare for a couple of reasons. The site is a bit challenging to find and hike to and getting the entire formation in a shot requires some clever positioning by the photographer. Alas, I did find one photo that may show the formation without its signature boulder on top. Say it isn’t so. Really. Let me know if you have recent, first-hand knowledge of the hoodoo. Rock or no rock, we await the revelation.

One day I was browsing through the Twenty-Third Biennial Report of the State Historical Society of Idaho published in 1922, as one does. It caught my attention that the report listed all the monuments in Idaho and associated with Idaho at the time. I skimmed through the list and descriptions to see if there might be blog fodder. Indeed. I will victimize you further with future posts but will restrain myself to a single monument for this one.

In fact, I’ll give only cursory attention to the monument mentioned because searching for more information on it led me down a path that with liberal use of unnecessary words will in itself be a blog.

See. I’ve already written 115 words without getting to the point. But I digress. But you knew that.

The monument that I wanted to research was the Sheepeater Monument. That monument, which I’ll tell you about in another post, was located near where Big Creek runs into the Salmon River. It’s a story worthy of a blog post, which I have already promised.

But today’s post, the one you’re reading, which has now run to 191 words without even approaching its subject, is about a “monument” I found while trying to do a little research on the aforementioned Sheepeater Monument.

Breaking out my copy of the trusty internet I did a Google image search for Sheepeater Monument, Idaho. What came up was an oddly shaped rock. It was actually more of a hoodoo which, now that the little ones have nodded off, I can proceed to describe.

The hoodoo in question, which was sometimes called Sheepeater’s Monument, is, as technical jargon would have it, really, really tall. I found a reference that said 70 feet. I don’t know. Photos show it towering over nearby trees. It is undeniably… let’s say tree-like, in that it is tall and narrow, but without the limbs one would usually find on a tall pine. A pole then. It’s like a pole. Eons ago some force, probably water followed later by wind, wore away layers of rock around it leaving a shaft of rock. And, to top it off, there is a large boulder resting impossibly on the summit of the hoodoo.

The formation has had some colorful names that I will leave up to you to imagine. It has a smaller pair of hoodoo companions nearby. This grouping of rude rocks at the head of Monumental Creek in Valley County is apparently why the creek is called that. We can be thankful for this unusual display of modesty on the part of the person who named it.

Photos of the formation are rare for a couple of reasons. The site is a bit challenging to find and hike to and getting the entire formation in a shot requires some clever positioning by the photographer. Alas, I did find one photo that may show the formation without its signature boulder on top. Say it isn’t so. Really. Let me know if you have recent, first-hand knowledge of the hoodoo. Rock or no rock, we await the revelation.

Published on December 22, 2024 04:00

December 21, 2024

The Union Block

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

If you’re familiar with a near-block-long group of stone buildings between Capitol Boulevard and 8th Street in downtown Boise, you probably know those structures as the Union Block. You’re right, but also a little wrong.

The building in the center of these structures is actually the Union Block all by itself, as it says on the sandstone facade. Architect John E. TourellotteIt designed the building in 1899. It was completed in 1902. This was during a little building boom in Boise. As plans were announced for the Union Block, adjacent property owners jumped on the bandwagon, matching facades on their buildings to that of the Union Block. The Idaho Statesman of July 27, 1901, noted that “The adjoining owners agreeing to immediately build, and in conformity with the plans of the new structure, means practically an entire stone block for Idaho Street.”

According to the Idaho Architecture Project Website, the Union Block Building is a Richardsonian Romanesque-styled building. The sandstone came from Table Rock and the whole thing cost $35,000 to build.

Why was the building called the Union Block? The original owners were Union supporters who wanted to show that and thumb their collective noses to southern sympathizers who were still prevalent decades after the Civil War.

This was apparently a common tactic. Boise’s Union Block was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Joining it in that honor are at least eleven other Union Blocks around the country, including one in Iowa, two in Kansas, one in Maine, two in Michigan, one in North Dakota, one in New York, one in Ohio, one in Oregon, and one in Utah.

Today the Union Block is a shell, awaiting the outcome of court cases and plans coming to fruition. With luck, it will be a central feature of Boise's downtown again someday.

If you’re familiar with a near-block-long group of stone buildings between Capitol Boulevard and 8th Street in downtown Boise, you probably know those structures as the Union Block. You’re right, but also a little wrong.

The building in the center of these structures is actually the Union Block all by itself, as it says on the sandstone facade. Architect John E. TourellotteIt designed the building in 1899. It was completed in 1902. This was during a little building boom in Boise. As plans were announced for the Union Block, adjacent property owners jumped on the bandwagon, matching facades on their buildings to that of the Union Block. The Idaho Statesman of July 27, 1901, noted that “The adjoining owners agreeing to immediately build, and in conformity with the plans of the new structure, means practically an entire stone block for Idaho Street.”

According to the Idaho Architecture Project Website, the Union Block Building is a Richardsonian Romanesque-styled building. The sandstone came from Table Rock and the whole thing cost $35,000 to build.

Why was the building called the Union Block? The original owners were Union supporters who wanted to show that and thumb their collective noses to southern sympathizers who were still prevalent decades after the Civil War.

This was apparently a common tactic. Boise’s Union Block was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Joining it in that honor are at least eleven other Union Blocks around the country, including one in Iowa, two in Kansas, one in Maine, two in Michigan, one in North Dakota, one in New York, one in Ohio, one in Oregon, and one in Utah.

Today the Union Block is a shell, awaiting the outcome of court cases and plans coming to fruition. With luck, it will be a central feature of Boise's downtown again someday.

Published on December 21, 2024 04:00

December 20, 2024

The Lugenbeel Monument

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Thanks to the Idaho Department of Transportation, the Idaho State Historical Society, and not least, Merle Wells, Idaho has a robust set of roadside historical markers. The inclination to mark historical points in the state was the genesis of the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers.

The group formed in 1925 to commemorate Idaho history. Their first act was to install a monument to honor George Grimes, one of the men who first discovered gold in the Boise Basin on August 2, 1862. He was killed a few days later and his partner, Moses Splawn, buried him in a nearby prospect hole. Splawn’s story was that hostile Indians killed Grimes. Some suspect the story might have been, let’s say, convenient.

The Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers placed 47 monuments in southwestern Idaho alone. Often, they were carved into the shape of Idaho using sandstone from Table Rock.

One problem with carving your stories about history in stone is that history doesn’t always stay the same. A prime example is the marker that was placed on Government Island in the Boise River in 1933. It was meant to commemorate the arrival of Colonel Pinkney Lugenbeel who scouted for a location of what would be Fort Boise. He settled on a site on July 4, 1863.

Certainly, this was an important link in the chain of events leading to the establishment of Boise. Lugenbeel helped plat the city a few days later.

Whoever wrote the inscription for the monument placed by the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers participated in a bit of hyperbole, not to mention misspelling. Okay, we’ll mention the misspelling, too. The inscription read:

GOVERNMENT ISLAND

THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION

IN BOISE VALLEY MAJOR LUGENBILE

SENT BY THE U.S. GOV’T TO

ESTABLISH BOISE BARRACKS.

CAMPED HERE JUNE 1863

The spelling mistake was in Lugenbeel’s name. The hyperbole was to call his efforts “the beginning of civilization in Boise Valley.” Had the writer added “European style” before the word civilization, it would have been more accurate. Indians had a civilization in the valley for millennia prior to the major’s arrival.

Government Island is no longer an island, and the Lugenbeel monument is no longer in place. Boise City parks personnel removed the monument in 2017 for restoration, then had second thoughts about putting it back up with the original condescending language.

Thanks to Boise City Department of Arts and History. Much of the information in this post, including the photo below, can be found in their publication Government Island Monument—A Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers Artifact.

Thanks to the Idaho Department of Transportation, the Idaho State Historical Society, and not least, Merle Wells, Idaho has a robust set of roadside historical markers. The inclination to mark historical points in the state was the genesis of the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers.

The group formed in 1925 to commemorate Idaho history. Their first act was to install a monument to honor George Grimes, one of the men who first discovered gold in the Boise Basin on August 2, 1862. He was killed a few days later and his partner, Moses Splawn, buried him in a nearby prospect hole. Splawn’s story was that hostile Indians killed Grimes. Some suspect the story might have been, let’s say, convenient.

The Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers placed 47 monuments in southwestern Idaho alone. Often, they were carved into the shape of Idaho using sandstone from Table Rock.

One problem with carving your stories about history in stone is that history doesn’t always stay the same. A prime example is the marker that was placed on Government Island in the Boise River in 1933. It was meant to commemorate the arrival of Colonel Pinkney Lugenbeel who scouted for a location of what would be Fort Boise. He settled on a site on July 4, 1863.

Certainly, this was an important link in the chain of events leading to the establishment of Boise. Lugenbeel helped plat the city a few days later.

Whoever wrote the inscription for the monument placed by the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers participated in a bit of hyperbole, not to mention misspelling. Okay, we’ll mention the misspelling, too. The inscription read:

GOVERNMENT ISLAND

THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION

IN BOISE VALLEY MAJOR LUGENBILE

SENT BY THE U.S. GOV’T TO

ESTABLISH BOISE BARRACKS.

CAMPED HERE JUNE 1863

The spelling mistake was in Lugenbeel’s name. The hyperbole was to call his efforts “the beginning of civilization in Boise Valley.” Had the writer added “European style” before the word civilization, it would have been more accurate. Indians had a civilization in the valley for millennia prior to the major’s arrival.

Government Island is no longer an island, and the Lugenbeel monument is no longer in place. Boise City parks personnel removed the monument in 2017 for restoration, then had second thoughts about putting it back up with the original condescending language.

Thanks to Boise City Department of Arts and History. Much of the information in this post, including the photo below, can be found in their publication Government Island Monument—A Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers Artifact.

Published on December 20, 2024 04:00

December 19, 2024

Possum Sweetheart

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

It will come as no shock to you that Idaho is an agricultural state. Knowing this, you would likely display little surprise to learn that there is a statue that honors a famous Idaho cow. What you might not expect is that the statue is in Washington state.

Segis Pietertje Prospect was born on a farm near Meridian in 1913 and was owned by George Layton. He sold the Holstein to E. A. Stuart, the CEO of Carnation. She became Stuart’s favorite cow. He nicknamed her Possum Sweetheart.

The company’s tagline for many years was “Carnation Condensed Milk, the milk from contented cows.” E.A. believed deeply in the philosophy that happy cows produced more milk. On the wall in the cow barn on the Carnation Farms spread, were painted these words:

“The RULE to be observed in this stable at all times, toward the cattle, young and old, is that of patience and kindness….

Remember that this is the home of mothers. Treat each cow as a mother should be treated. The giving of milk is a function of motherhood; rough treatment lessens the flow. That injures me as well as the cow. Always keep these ideas in mind in dealing with my cattle.”

No cow was more contented than Possum Sweetheart. At least none showed their contentment more in the production of milk. Sweetheart put out 37,380.1 pounds of milk in 365 days. The average production for a milk cow at the time was about 1,500 to 1,900 pounds of milk in that period of time.

The Idaho born and bred Holstein lived to be 12 years old, which is a long life for a cow. In 1928 E.A. Stuart commissioned a sculpture of his favorite cow. Well-known sculptor Frederick Willard Potter carved Possum Sweetheart’s life-size likeness into marble.

The sculpture to a cow who produced her own weight in milk every three weeks can still be seen today at Carnation Farms, Carnation, Washington.

It will come as no shock to you that Idaho is an agricultural state. Knowing this, you would likely display little surprise to learn that there is a statue that honors a famous Idaho cow. What you might not expect is that the statue is in Washington state.

Segis Pietertje Prospect was born on a farm near Meridian in 1913 and was owned by George Layton. He sold the Holstein to E. A. Stuart, the CEO of Carnation. She became Stuart’s favorite cow. He nicknamed her Possum Sweetheart.

The company’s tagline for many years was “Carnation Condensed Milk, the milk from contented cows.” E.A. believed deeply in the philosophy that happy cows produced more milk. On the wall in the cow barn on the Carnation Farms spread, were painted these words:

“The RULE to be observed in this stable at all times, toward the cattle, young and old, is that of patience and kindness….

Remember that this is the home of mothers. Treat each cow as a mother should be treated. The giving of milk is a function of motherhood; rough treatment lessens the flow. That injures me as well as the cow. Always keep these ideas in mind in dealing with my cattle.”

No cow was more contented than Possum Sweetheart. At least none showed their contentment more in the production of milk. Sweetheart put out 37,380.1 pounds of milk in 365 days. The average production for a milk cow at the time was about 1,500 to 1,900 pounds of milk in that period of time.

The Idaho born and bred Holstein lived to be 12 years old, which is a long life for a cow. In 1928 E.A. Stuart commissioned a sculpture of his favorite cow. Well-known sculptor Frederick Willard Potter carved Possum Sweetheart’s life-size likeness into marble.

The sculpture to a cow who produced her own weight in milk every three weeks can still be seen today at Carnation Farms, Carnation, Washington.

Published on December 19, 2024 04:00

December 18, 2024

Misspellings in Idaho History

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Things get misspelled all the time. If you don’t believe that, you’re clearly not on Facebook. I’ve begun collecting a few misspellings that have had an impact on Idaho history. My hope is that readers will share some things they’ve noticed, such as:

Hagerman

Shoshoni Indians traditionally wintered here and speared salmon at Lower Salmon Falls. It became a stage station on the Oregon Trail, and eventually had enough residents that a couple of men applied for a post office. The men were Stanley Hegeman (or Hageman—I’ve seen it both ways) and Jack Hess. They wanted to call the place Hess, but postal officials nixed it because there was already a Hess, Idaho. There isn’t one now, and I’ve found no information about where Hess was. Someone will probably come to my rescue.

Naturally, since Hess was taken, they tried for Hageman (or Hegeman). Postal officials blessed that one, but misspelled the name as Hagerman, perhaps because of poor penmanship on the part of the applicants.

Potatoe

You remember Dan Quayle, right? He was the vice president who infamously corrected the spelling of Idaho’s famous tuber as “potatoe” in front of a group of kids on June 15, 1992. That moment is preserved for… as long as potatoes can be preserved, at the Idaho Potato Museum in Blackfoot. A California DJ asked Quayle to autograph a potato for him, all in good fun. Somehow the museum ended up with it.

Cariboo

Caribou County is named for Jesse “Cariboo Jack” Fairchild who was, in turn, nicknamed such because he had taken part in the gold rush in the Cariboo region of British Columbia in 1860. There are a lot of things around Soda Springs named after Cariboo Jack, including the ghost town of Caribou City, and the Caribou Mountains. Fairchild was born in Canada. What isn’t exactly clear is why the Cariboo region of British Columbia is spelled that way. Canadians don’t generally spell caribou differently. In any case Jack’s nickname became Caribou when it was attached to various sites in Caribou County, the last county created in Idaho.

Kansas

This one is outrageous. The Treaty of Fort Bridger was, among other things, meant to preserve the right of the Bannock Tribe to harvest camas bulbs on Camas Prairie near present-day Fairfield. Unfortunately, Camas Prairie was written as Kansas Prairie in the treaty. Using that flimsy excuse white settlers let their cattle and hogs trample and root around the traditional Bannock gathering site, devastating the camas fields, and leading to the Bannock War of 1878.

Spelling matters, kids.

Things get misspelled all the time. If you don’t believe that, you’re clearly not on Facebook. I’ve begun collecting a few misspellings that have had an impact on Idaho history. My hope is that readers will share some things they’ve noticed, such as:

Hagerman

Shoshoni Indians traditionally wintered here and speared salmon at Lower Salmon Falls. It became a stage station on the Oregon Trail, and eventually had enough residents that a couple of men applied for a post office. The men were Stanley Hegeman (or Hageman—I’ve seen it both ways) and Jack Hess. They wanted to call the place Hess, but postal officials nixed it because there was already a Hess, Idaho. There isn’t one now, and I’ve found no information about where Hess was. Someone will probably come to my rescue.

Naturally, since Hess was taken, they tried for Hageman (or Hegeman). Postal officials blessed that one, but misspelled the name as Hagerman, perhaps because of poor penmanship on the part of the applicants.

Potatoe

You remember Dan Quayle, right? He was the vice president who infamously corrected the spelling of Idaho’s famous tuber as “potatoe” in front of a group of kids on June 15, 1992. That moment is preserved for… as long as potatoes can be preserved, at the Idaho Potato Museum in Blackfoot. A California DJ asked Quayle to autograph a potato for him, all in good fun. Somehow the museum ended up with it.

Cariboo

Caribou County is named for Jesse “Cariboo Jack” Fairchild who was, in turn, nicknamed such because he had taken part in the gold rush in the Cariboo region of British Columbia in 1860. There are a lot of things around Soda Springs named after Cariboo Jack, including the ghost town of Caribou City, and the Caribou Mountains. Fairchild was born in Canada. What isn’t exactly clear is why the Cariboo region of British Columbia is spelled that way. Canadians don’t generally spell caribou differently. In any case Jack’s nickname became Caribou when it was attached to various sites in Caribou County, the last county created in Idaho.

Kansas

This one is outrageous. The Treaty of Fort Bridger was, among other things, meant to preserve the right of the Bannock Tribe to harvest camas bulbs on Camas Prairie near present-day Fairfield. Unfortunately, Camas Prairie was written as Kansas Prairie in the treaty. Using that flimsy excuse white settlers let their cattle and hogs trample and root around the traditional Bannock gathering site, devastating the camas fields, and leading to the Bannock War of 1878.

Spelling matters, kids.

Published on December 18, 2024 04:00

December 17, 2024

Hoofprints Above You

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Rangers at Malad Gorge State Park found a couple of sets of horse hoof prints in the park in 1990. That made a little news. Why? The hoof prints are estimated to be about a million years old.

In fact, the prints were rediscovered. A ranger was giving an interpretive program about the park when sisters Peggy Bennett Smith and Grace Bennett Goodlin interrupted to tell about a cave near the bottom of the gorge that they knew about. Smith, who lived in Hawaii, and Goodlin, visiting from Texas, had grown up nearby on their grandfather S.W. Ritchie’s ranch. As girls they had spent time fishing in the gorge and had found the cave, which they called “the pony track site.” (Deseret News, December 23, 1990)

Park Manager Kevin Lynott asked the sisters to show him the site, which they did.

Fossilized tracks of ancient animals are fairly common around the world. The ones at Malad Gorge may be unique. Rather than a depression in what was once mud, these prints were hoof-shaped mounds on the roof of the cave, almost as if you were looking at the bottom of the hoof plunging through the rock.

William (Bill) Akersten, PhD, then the curator of the Idaho Museum of Natural History studied the tracks and told how they were likely formed. There was wet sand or mud on top of an old lava flow when several horses came galloping along leaving hoof prints behind them. Speculating what they might have been running from a million years hence is just guesswork, but their existence proves that an active lava flow soon poured across the sand and the depressions left by the horses. At some point erosion from the nearby Malad River probably washed out the softer remnants of the ancient sand leaving behind a three-foot cave with hoof prints protruding from its ceiling.

The prints are about the size a modern horse might make. Though the animals that made them may have been distantly related, the prints were not made by the famous Hagerman Horse, fossils of which were found just a few miles away. The Hagerman Horse was smaller and lived about 2.5 million years earlier.

The ancient tracks may have had an impact a million years after the lava cooled. There was a proposal about that time to build a “high drop” power site that would have run a large pipe over the edge of the canyon and into the river. It would have threatened the unique hoof prints and the proposal was scrapped.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Rangers at Malad Gorge State Park found a couple of sets of horse hoof prints in the park in 1990. That made a little news. Why? The hoof prints are estimated to be about a million years old.

In fact, the prints were rediscovered. A ranger was giving an interpretive program about the park when sisters Peggy Bennett Smith and Grace Bennett Goodlin interrupted to tell about a cave near the bottom of the gorge that they knew about. Smith, who lived in Hawaii, and Goodlin, visiting from Texas, had grown up nearby on their grandfather S.W. Ritchie’s ranch. As girls they had spent time fishing in the gorge and had found the cave, which they called “the pony track site.” (Deseret News, December 23, 1990)

Park Manager Kevin Lynott asked the sisters to show him the site, which they did.

Fossilized tracks of ancient animals are fairly common around the world. The ones at Malad Gorge may be unique. Rather than a depression in what was once mud, these prints were hoof-shaped mounds on the roof of the cave, almost as if you were looking at the bottom of the hoof plunging through the rock.

William (Bill) Akersten, PhD, then the curator of the Idaho Museum of Natural History studied the tracks and told how they were likely formed. There was wet sand or mud on top of an old lava flow when several horses came galloping along leaving hoof prints behind them. Speculating what they might have been running from a million years hence is just guesswork, but their existence proves that an active lava flow soon poured across the sand and the depressions left by the horses. At some point erosion from the nearby Malad River probably washed out the softer remnants of the ancient sand leaving behind a three-foot cave with hoof prints protruding from its ceiling.

The prints are about the size a modern horse might make. Though the animals that made them may have been distantly related, the prints were not made by the famous Hagerman Horse, fossils of which were found just a few miles away. The Hagerman Horse was smaller and lived about 2.5 million years earlier.

The ancient tracks may have had an impact a million years after the lava cooled. There was a proposal about that time to build a “high drop” power site that would have run a large pipe over the edge of the canyon and into the river. It would have threatened the unique hoof prints and the proposal was scrapped.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Published on December 17, 2024 04:00

December 16, 2024

Help Wanted, 1864

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

In 1864, Idaho was barely a territory. One writer for the Idaho Statesman noticed that many people were coming through Boise on their way to Oregon Territory, often without stopping.

In the August 20, 1864 editorial the writer lamented that people seemed to give up on Boise too soon. “A man can seldom see a chance to make money or start in business the first or second day he stops in a new place.”

The writer noted that “Most of the available land along the river is claimed, but there are many thousands of acres lying back that are not claimed which need only a moderate outlay of labor and capital to make as productive as could be desired.”

It would be a couple more decades before canal projects made many of those thousand acres bloom. Still, there was plenty of opportunity in the valley.

The editorial expressed an almost unlimited need for laborers. “You cannot stay in this town three days without finding something to do, and our word for it, you will ever after that have more on your hands than you can do.” Not every profession was needed, though. The editorial concluded with this: “If you want to practice law or physic, don’t stop, for we have more than enough of both. If you want to get into office and dabble in politics, for Heaven’s sake move on to some other country. We have a large population of that sort that we would be glad to export.”

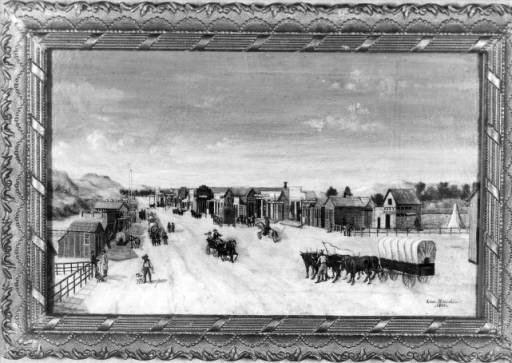

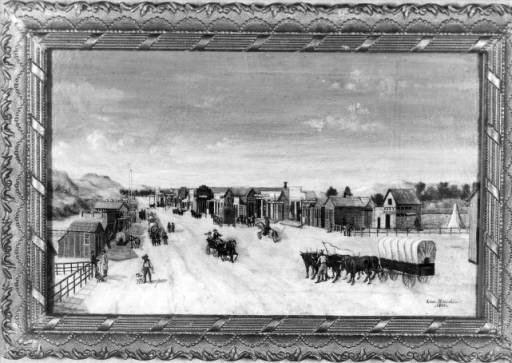

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

In 1864, Idaho was barely a territory. One writer for the Idaho Statesman noticed that many people were coming through Boise on their way to Oregon Territory, often without stopping.

In the August 20, 1864 editorial the writer lamented that people seemed to give up on Boise too soon. “A man can seldom see a chance to make money or start in business the first or second day he stops in a new place.”

The writer noted that “Most of the available land along the river is claimed, but there are many thousands of acres lying back that are not claimed which need only a moderate outlay of labor and capital to make as productive as could be desired.”

It would be a couple more decades before canal projects made many of those thousand acres bloom. Still, there was plenty of opportunity in the valley.

The editorial expressed an almost unlimited need for laborers. “You cannot stay in this town three days without finding something to do, and our word for it, you will ever after that have more on your hands than you can do.” Not every profession was needed, though. The editorial concluded with this: “If you want to practice law or physic, don’t stop, for we have more than enough of both. If you want to get into office and dabble in politics, for Heaven’s sake move on to some other country. We have a large population of that sort that we would be glad to export.”

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on December 16, 2024 04:00

December 15, 2024

The Early Idaho Statesman

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

In the 1870s it was often a challenge for the staff of the Idaho Statesman and the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman to get the paper out. First, someone had to be found to turn the press. The single cylinder Acme press was hand operated, often by a Chinese laborer. If someone could not be found to crank the machine, it fell to the staff. Everyone from the editor on down took their turn at the wheel to keep the press running.

It was not always labor that was in short supply. The paper to feed through the press was brought in by freight teams from Kelton, Utah. Except when it wasn’t. If the newsprint failed to show, there was a scramble to find anything that would take ink. Butcher paper and grocery store paper sometimes filled in for the real thing.

The tri-weekly version of the paper had a circulation of about 1200 copies, and the weekly ran about 800 copies. That was a lot of folding. In those early days the newspapers had to be folded by hand by everyone in the office.

Charles Payton, who worked for the Statesman in the 1870s, reminisced about the early days in the December 15, 1918 edition of the paper. He remembered an irate subscriber that burst into the office one day. Payton had gotten a little ahead of the game by writing the man’s obituary. The man was on death’s door, so the paper printed it. Apparently the reportedly dead subscriber had decided not to knock on the door of death. Instead he stopped by to complain vehemently that his demise had been prematurely printed in the paper. Mark Twain, it is said, had a similar experience.

In the 1870s it was often a challenge for the staff of the Idaho Statesman and the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman to get the paper out. First, someone had to be found to turn the press. The single cylinder Acme press was hand operated, often by a Chinese laborer. If someone could not be found to crank the machine, it fell to the staff. Everyone from the editor on down took their turn at the wheel to keep the press running.

It was not always labor that was in short supply. The paper to feed through the press was brought in by freight teams from Kelton, Utah. Except when it wasn’t. If the newsprint failed to show, there was a scramble to find anything that would take ink. Butcher paper and grocery store paper sometimes filled in for the real thing.

The tri-weekly version of the paper had a circulation of about 1200 copies, and the weekly ran about 800 copies. That was a lot of folding. In those early days the newspapers had to be folded by hand by everyone in the office.

Charles Payton, who worked for the Statesman in the 1870s, reminisced about the early days in the December 15, 1918 edition of the paper. He remembered an irate subscriber that burst into the office one day. Payton had gotten a little ahead of the game by writing the man’s obituary. The man was on death’s door, so the paper printed it. Apparently the reportedly dead subscriber had decided not to knock on the door of death. Instead he stopped by to complain vehemently that his demise had been prematurely printed in the paper. Mark Twain, it is said, had a similar experience.

Published on December 15, 2024 04:00

December 14, 2024

Please Don't Eat the Beaver

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Trappers were most interested in beavers for their pelts. Once a beaver is liberated of its fur, though, another opportunity presents itself to man not too squeamish to eat a rodent. Beaver tail is considered a delicacy by some, and we’re not referring to the Canadian pastry of the same name which is shaped like a beaver tail.

All this is by way of giving you a little history on Malad. The river. Okay, both rivers. Idaho is blessed with two Malad rivers, one in Oneida County, the county seat of which—and only town of any size—is Malad City. The other is the Malad River in Gooding County. That one runs through Malad Gorge, the spectacular canyon where the river tumbles into Devil’s Washbowl right below the I-84 bridge near Tuttle. You can see the gorge while traveling on the interstate for 1.35 seconds if you happen to look south while going 80 miles per hour. Next time you drive by, don’t. Stop for a few minutes at Malad Gorge State Park. Walk across the gorge on the scary but safe footbridge and gaze down at the Malad River 250 feet below. Just don’t eat the beavers.

Ah yes, the beavers. Early trappers working for the Pacific Fur Company, called Astorians after company owner John Jacob Astor, encountered the river and its tasty beaver in 1811. That’s when Donald Mackenzie led them on an exploratory jaunt after the Wilson Price Hunt expedition met disaster in the rapids of the Snake River at Caldron Linn.

Long story short: They ate beaver and got sick. Mackenzie named the river Malad or Malade, which means “sick” in French.

Much speculation has ensued in the centuries following the illness the men experienced as to its cause. Had the beaver eaten some poisonous root? Had selenium concentrated in the fat of the beaver tails? No one knows.

By the way, the naming of Idaho’s other Malad River has a similar story with different players. The lesson here might be to stick to the Canadian pastry if you insist on adding beaver tails to your diet.

Malad Gorge circa 1970. Ranger Rick Cummins gazes into the gorge. At the top of the picture is the I-84 bridge across the head of the gorge. Installation of the footbridge in Malad Gorge State Park would come later.

Malad Gorge circa 1970. Ranger Rick Cummins gazes into the gorge. At the top of the picture is the I-84 bridge across the head of the gorge. Installation of the footbridge in Malad Gorge State Park would come later.

Trappers were most interested in beavers for their pelts. Once a beaver is liberated of its fur, though, another opportunity presents itself to man not too squeamish to eat a rodent. Beaver tail is considered a delicacy by some, and we’re not referring to the Canadian pastry of the same name which is shaped like a beaver tail.

All this is by way of giving you a little history on Malad. The river. Okay, both rivers. Idaho is blessed with two Malad rivers, one in Oneida County, the county seat of which—and only town of any size—is Malad City. The other is the Malad River in Gooding County. That one runs through Malad Gorge, the spectacular canyon where the river tumbles into Devil’s Washbowl right below the I-84 bridge near Tuttle. You can see the gorge while traveling on the interstate for 1.35 seconds if you happen to look south while going 80 miles per hour. Next time you drive by, don’t. Stop for a few minutes at Malad Gorge State Park. Walk across the gorge on the scary but safe footbridge and gaze down at the Malad River 250 feet below. Just don’t eat the beavers.

Ah yes, the beavers. Early trappers working for the Pacific Fur Company, called Astorians after company owner John Jacob Astor, encountered the river and its tasty beaver in 1811. That’s when Donald Mackenzie led them on an exploratory jaunt after the Wilson Price Hunt expedition met disaster in the rapids of the Snake River at Caldron Linn.

Long story short: They ate beaver and got sick. Mackenzie named the river Malad or Malade, which means “sick” in French.

Much speculation has ensued in the centuries following the illness the men experienced as to its cause. Had the beaver eaten some poisonous root? Had selenium concentrated in the fat of the beaver tails? No one knows.

By the way, the naming of Idaho’s other Malad River has a similar story with different players. The lesson here might be to stick to the Canadian pastry if you insist on adding beaver tails to your diet.

Malad Gorge circa 1970. Ranger Rick Cummins gazes into the gorge. At the top of the picture is the I-84 bridge across the head of the gorge. Installation of the footbridge in Malad Gorge State Park would come later.

Malad Gorge circa 1970. Ranger Rick Cummins gazes into the gorge. At the top of the picture is the I-84 bridge across the head of the gorge. Installation of the footbridge in Malad Gorge State Park would come later.

Published on December 14, 2024 04:00

December 13, 2024

D Boon in Idaho

Speaking of Idaho will change to a subscription service beginning January 1. If you're interested in getting a fresh Idaho history newsletter every week in your email box, click here for more details.

Daniel Boone was a celebrated frontiersman, back when the frontier included parts of Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Kentucky. He first gained fame during the American Revolution when he and a group of men recaptured three girls, one Boone’s daughter, from an Indian war party recruited by the British. James Fenimore Cooper wrote a fictionalized version of the event in Last of the Mohicans.

That was in 1776. Why do we in Idaho care? Because his well-documented exploits at that time seem to have placed him some 1,800 miles away from Idaho, not somewhere on the Continental Divide carving his misspelled name into an aspen tree.

In 1976 an Idaho Falls woman named Louise Rutledge became intrigued by an inscription on an aspen tree that said, “D. Boon 1776.” The carving was old. Well, maybe not 1776 old, but certainly not as new as 1976. Rutledge wrote a little book called D. Boon 1776 A Western Bicentennial Mystery. According to the Sunday, August 10, 1976 edition of the Idaho Statesman she “began extensive research to prove—or disprove—that frontiersman Daniel Boone was, in fact, in Idaho 30 years ahead of Lewis and Clark.”

Rutledge became convinced that Boone had carved his initials into the tree, not in spite of, but because of the absence of the “e” at the end of his name. She had grown up in the Cumberland Gap area of Tennessee which was awash in tales about “Boon trees.” She was certain that because of the misspelling, this carving was genuine. There were many “Boon trees” scattered around the south, often with the added information that D. Boon had cilled or kilt or killed a bar, bar being the way a genuine frontiersman would spell bear. We can’t know how many or if any of those carvings are genuine, but we do know that when signing or printing his name, Danielle Boone always knew how to spell it.

Not ready to leave a good story untold, Rutledge and her husband, Gene, and Bonita Pendleton, all of Idaho Falls, wrote a play speculating on Boone’s journey to Idaho, called D. Boone 1776, War Has Two Sides.

Tree experts later determined the carving on the Idaho Aspen had been done in about 1895. Undeterred, Rutledge postulated that someone had seen the original, genuine D. Boon tree, and noticed that it was dead. To preserve the history for posterity, they made a copy.

Well, it’s a theory.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

Daniel Boone was a celebrated frontiersman, back when the frontier included parts of Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Kentucky. He first gained fame during the American Revolution when he and a group of men recaptured three girls, one Boone’s daughter, from an Indian war party recruited by the British. James Fenimore Cooper wrote a fictionalized version of the event in Last of the Mohicans.

That was in 1776. Why do we in Idaho care? Because his well-documented exploits at that time seem to have placed him some 1,800 miles away from Idaho, not somewhere on the Continental Divide carving his misspelled name into an aspen tree.

In 1976 an Idaho Falls woman named Louise Rutledge became intrigued by an inscription on an aspen tree that said, “D. Boon 1776.” The carving was old. Well, maybe not 1776 old, but certainly not as new as 1976. Rutledge wrote a little book called D. Boon 1776 A Western Bicentennial Mystery. According to the Sunday, August 10, 1976 edition of the Idaho Statesman she “began extensive research to prove—or disprove—that frontiersman Daniel Boone was, in fact, in Idaho 30 years ahead of Lewis and Clark.”

Rutledge became convinced that Boone had carved his initials into the tree, not in spite of, but because of the absence of the “e” at the end of his name. She had grown up in the Cumberland Gap area of Tennessee which was awash in tales about “Boon trees.” She was certain that because of the misspelling, this carving was genuine. There were many “Boon trees” scattered around the south, often with the added information that D. Boon had cilled or kilt or killed a bar, bar being the way a genuine frontiersman would spell bear. We can’t know how many or if any of those carvings are genuine, but we do know that when signing or printing his name, Danielle Boone always knew how to spell it.

Not ready to leave a good story untold, Rutledge and her husband, Gene, and Bonita Pendleton, all of Idaho Falls, wrote a play speculating on Boone’s journey to Idaho, called D. Boone 1776, War Has Two Sides.

Tree experts later determined the carving on the Idaho Aspen had been done in about 1895. Undeterred, Rutledge postulated that someone had seen the original, genuine D. Boon tree, and noticed that it was dead. To preserve the history for posterity, they made a copy.

Well, it’s a theory.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

Published on December 13, 2024 04:00