Rick Just's Blog, page 8

October 23, 2024

Idaho's First West Point Graduate became "The Old Soldier"

Virgil Jefferson Brumback, the son of Jeremiah and Harriet Brumback, early Boise residents, made the Statesman in 1877: “Master Virgil Brumback and Nellie Brayman, daughter of Governor Brayman, left this morning for the east. A farewell surprise party was given them at the residence of J. Brumback last evening.” What their relationship was is open for speculation. Perhaps he was escorting her for a visit home (the Braymens were from Indianapolis). Her name never appeared in an Idaho newspaper again. He never married.

But Virgil Brumback did attract the attention of women, if an 1881 gossipy piece in the Idaho Statesman is any indication. An observer noted some girls on the street. “Yonder goes Virgil Brumback,” whispered one. “He always did have a fine figure, but somehow the training of the army has given him a certain distinguished air, that few boys attain.” The writer continued, “They passed out of hearing, but as I watched the free stride of the young man across from me, I thought the girls had summed up impressions exactly.”

That Brumback was in the Army was the talk of the town, though Army enlistments were common enough. The girls had been observing Idaho Territory’s first West Point cadet.

The papers in Idaho, if not the girls, followed his postings and adventures for the next few years. At first, Brumback was stationed at Collville, Washington, until the Army abandoned that post. In 1883, he moved to Fort Spokane. Established in 1882, it was the last Army fort built in the American West.

In 1884, First Lieutenant Virgil Brumback found himself in the Yukon Exploring Party sent out by General Nelson Miles. They went to Alaska on the steamship Idaho. To get the party to Copper River, the Idaho sailed nearly 500 miles northwest of its usual Sitka port. The explorers intended to follow the Copper River inland to the Yukon, traveling first in canoes and then trading those for dog sleds. They depended on indigenous locals coming down from the Yukon to trade.

When the group arrived at the mouth of Copper River, they found the native traders had come and gone. Nevertheless, the explorers sent the Idaho on its way and began their trek. They made it only as far as Child’s Glacier, about 33 miles inland, before giving up.

The newspapers were quiet about Brumback until 1887 when he inexplicably resigned his commission. His resignation was, at first, accepted by President Grover Cleveland, then later rejected.

In 1888, Brumback was court-martialed at Fort Omaha for throwing a glass of whisky into a first lieutenant's face. Brumback was said to have been moody, shunning society. If the charges were sustained, Omaha newspapers said, he would be dismissed from the service.

Apparently, the outcome of the court martial was in his favor because, in July 1891, he reported for recruiting duty at the Columbus Barracks in Ohio. Only eight months later, in 1892, the first lieutenant was relieved of his recruiting duty and given six months leave.

In November of that year, he resigned again. Again, his resignation was accepted by the president, effective February 12, 1893. But when that February rolled around, the president suspended the acceptance of his resignation.

The picture of a troubled young man began to take shape when in April 1893, “brother officers” escorted First Lieutenant Virgil Brumback to Washington, DC, from Fort Sherman in Coeur d’Alene. Those officers intended to deliver him to the surgeon in charge of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Insane. Told of the plan the morning after their arrival in DC, Brumback seemed to take it calmly. Shortly after breakfast, however, he couldn’t be found. He had picked up his valise, paid his bill at the hotel, and disappeared.

In reporting on the event for its Boise readers, the Idaho Statesman reviewed Brumback’s history, revealing that he had left his command suddenly in Omaha following the whiskey-throwing incident to return to Idaho. Rather than return to Boise, where he grew up, Brumback found a secluded spot in Kootenai County, where he had lived as a hermit. The report ended with, “The unfortunate young officer is well known in this city, and his many friends here hope to learn soon that his reason has been fully restored.”

Brumback’s subsequent movements are unclear, but the Army gave up on him, “retiring” the man.

Fast forward to August 3, 1937. Why such a long skip? Virgil Brumback didn’t make the news for 40 years. He had taken up residence, again, in a ramshackle cabin he had built himself in Kootenai County. He had homesteaded the property where he lived in seclusion.

Brumback never talked about his past, rarely talking at all with neighbors. Though most believed he was poverty-stricken, he had been drawing a $60 monthly soldier’s pension for decades. Known only as the “old soldier” to those who were aware of him, Virgil Brumback, 80, died that August with $3181 sewn into his vest, ending the tale of Idaho’s first West Point graduate. He is buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery, St. Maries.

But Virgil Brumback did attract the attention of women, if an 1881 gossipy piece in the Idaho Statesman is any indication. An observer noted some girls on the street. “Yonder goes Virgil Brumback,” whispered one. “He always did have a fine figure, but somehow the training of the army has given him a certain distinguished air, that few boys attain.” The writer continued, “They passed out of hearing, but as I watched the free stride of the young man across from me, I thought the girls had summed up impressions exactly.”

That Brumback was in the Army was the talk of the town, though Army enlistments were common enough. The girls had been observing Idaho Territory’s first West Point cadet.

The papers in Idaho, if not the girls, followed his postings and adventures for the next few years. At first, Brumback was stationed at Collville, Washington, until the Army abandoned that post. In 1883, he moved to Fort Spokane. Established in 1882, it was the last Army fort built in the American West.

In 1884, First Lieutenant Virgil Brumback found himself in the Yukon Exploring Party sent out by General Nelson Miles. They went to Alaska on the steamship Idaho. To get the party to Copper River, the Idaho sailed nearly 500 miles northwest of its usual Sitka port. The explorers intended to follow the Copper River inland to the Yukon, traveling first in canoes and then trading those for dog sleds. They depended on indigenous locals coming down from the Yukon to trade.

When the group arrived at the mouth of Copper River, they found the native traders had come and gone. Nevertheless, the explorers sent the Idaho on its way and began their trek. They made it only as far as Child’s Glacier, about 33 miles inland, before giving up.

The newspapers were quiet about Brumback until 1887 when he inexplicably resigned his commission. His resignation was, at first, accepted by President Grover Cleveland, then later rejected.

In 1888, Brumback was court-martialed at Fort Omaha for throwing a glass of whisky into a first lieutenant's face. Brumback was said to have been moody, shunning society. If the charges were sustained, Omaha newspapers said, he would be dismissed from the service.

Apparently, the outcome of the court martial was in his favor because, in July 1891, he reported for recruiting duty at the Columbus Barracks in Ohio. Only eight months later, in 1892, the first lieutenant was relieved of his recruiting duty and given six months leave.

In November of that year, he resigned again. Again, his resignation was accepted by the president, effective February 12, 1893. But when that February rolled around, the president suspended the acceptance of his resignation.

The picture of a troubled young man began to take shape when in April 1893, “brother officers” escorted First Lieutenant Virgil Brumback to Washington, DC, from Fort Sherman in Coeur d’Alene. Those officers intended to deliver him to the surgeon in charge of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Insane. Told of the plan the morning after their arrival in DC, Brumback seemed to take it calmly. Shortly after breakfast, however, he couldn’t be found. He had picked up his valise, paid his bill at the hotel, and disappeared.

In reporting on the event for its Boise readers, the Idaho Statesman reviewed Brumback’s history, revealing that he had left his command suddenly in Omaha following the whiskey-throwing incident to return to Idaho. Rather than return to Boise, where he grew up, Brumback found a secluded spot in Kootenai County, where he had lived as a hermit. The report ended with, “The unfortunate young officer is well known in this city, and his many friends here hope to learn soon that his reason has been fully restored.”

Brumback’s subsequent movements are unclear, but the Army gave up on him, “retiring” the man.

Fast forward to August 3, 1937. Why such a long skip? Virgil Brumback didn’t make the news for 40 years. He had taken up residence, again, in a ramshackle cabin he had built himself in Kootenai County. He had homesteaded the property where he lived in seclusion.

Brumback never talked about his past, rarely talking at all with neighbors. Though most believed he was poverty-stricken, he had been drawing a $60 monthly soldier’s pension for decades. Known only as the “old soldier” to those who were aware of him, Virgil Brumback, 80, died that August with $3181 sewn into his vest, ending the tale of Idaho’s first West Point graduate. He is buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery, St. Maries.

Published on October 23, 2024 04:00

October 21, 2024

Jackrabbits

In 1875 the territorial legislature established a bounty on jackrabbits. Rather than require that bunny hunters bring in the whole rabbit, a pair of ears was enough to claim the bounty. The county paid from about a penny a pair to as much as 5 cents for a pair of ears, depending on how big the rabbit population was.

Jack Rabbit populations fluctuate naturally on a 7-11-year cycle. On their own their numbers can be large one year and drop by 90 percent the next. They can recover quite rapidly because of their well-known ability to, let’s say, court. Weather can impact the cycle, with hard winters and dry summers making life tough for rabbits.

Why the fluctuation? There are many reasons, which lead to many questions, just as if you have a 3-year-old at hand to ask, why, why, why, why? Predator populations fluctuate, so you’ll see a lot more coyotes when there are a lot more rabbits. And, when there are a lot of rabbits, a lot of rabbit disease spreads among the population. The availability of feed plays a part, so the weather is in the mix.

Farmers inserted themselves into this crazy cycle as soon as they began farming in Idaho. They probably didn’t mind a few rabbits, but when that cycle came around every few years and there were more rabbits than stocks of corn or wheat, the tolerance of farmers ran short. Thus the bounty on rabbit ears.

In deference to those who may have just eaten, I won’t go into great detail about how those bounties were collected. It wasn’t unusual to have a large circle of men and boys close in on a thousand or more rabbits and dispatch them in ways that would make Walt Disney squeamish.

They didn’t do it for sport. Jack Rabbits have caused millions of dollars in damages for farmers over the years, sometimes destroying a thousand acres at a time.

In a uniquely Idaho sidelight, I must point out that the first Stinker Station advertising/humorous sign was about rabbit drives. Farris Lind installed it on the old highway between Boise and Mountain Home when rabbit drives were common in that area. The humorous side of the sign said, "Notice: Running Rabbits Have Right of Way!"

Black-tailed jackrabbit. (2024, June 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-t...

Black-tailed jackrabbit. (2024, June 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-t...

Jack Rabbit populations fluctuate naturally on a 7-11-year cycle. On their own their numbers can be large one year and drop by 90 percent the next. They can recover quite rapidly because of their well-known ability to, let’s say, court. Weather can impact the cycle, with hard winters and dry summers making life tough for rabbits.

Why the fluctuation? There are many reasons, which lead to many questions, just as if you have a 3-year-old at hand to ask, why, why, why, why? Predator populations fluctuate, so you’ll see a lot more coyotes when there are a lot more rabbits. And, when there are a lot of rabbits, a lot of rabbit disease spreads among the population. The availability of feed plays a part, so the weather is in the mix.

Farmers inserted themselves into this crazy cycle as soon as they began farming in Idaho. They probably didn’t mind a few rabbits, but when that cycle came around every few years and there were more rabbits than stocks of corn or wheat, the tolerance of farmers ran short. Thus the bounty on rabbit ears.

In deference to those who may have just eaten, I won’t go into great detail about how those bounties were collected. It wasn’t unusual to have a large circle of men and boys close in on a thousand or more rabbits and dispatch them in ways that would make Walt Disney squeamish.

They didn’t do it for sport. Jack Rabbits have caused millions of dollars in damages for farmers over the years, sometimes destroying a thousand acres at a time.

In a uniquely Idaho sidelight, I must point out that the first Stinker Station advertising/humorous sign was about rabbit drives. Farris Lind installed it on the old highway between Boise and Mountain Home when rabbit drives were common in that area. The humorous side of the sign said, "Notice: Running Rabbits Have Right of Way!"

Black-tailed jackrabbit. (2024, June 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-t...

Black-tailed jackrabbit. (2024, June 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-t...

Published on October 21, 2024 04:00

October 20, 2024

Paving the Streets and Sidewalks

Pavement is a big part of life in Boise. There are more than 5,000 lane miles in Ada County, so you can’t go far without stepping on asphalt. It wasn’t always so.

Boise, founded in 1863, was content—maybe resigned—in the early days to dusty roads on dry days and mud bogs when it rained. In 1867 the Idaho Statesman expressed pleasure to see a “nice piece of pavement” in from of Mr. Blossom and Bloch, Miller & Co. The paper asked, “When shall we see a mile of it in Boise City?” I can provide the answer from my time machine: about 30 years.

“Pavement” could mean a lot of things, depending on the situation. We think of asphalt today, or maybe concrete. In 1874, there was some paving of gutters in front of C.W. Moore’s First National Bank. The Statesman welcomed that but cautioned that no one should get the idea of hauling gravel in to make a roadbed. “There is no road so heavy and unpleasant in dry weather as deep gravel and sand. Our season is dry for two-thirds to three-fourths of the year. Suppose we have mud one-third or a fourth of the year, it is better go bear a bad road one-fourth of the time than three-fourths.”

In 1880, the Statesman was lauding “handsome wood pavement” in front of the Valley Store. This brings up another point of confusion. “Pavement” could also refer to sidewalks, not just streets. Three years later, the paper was chiding a local restaurant for the badly dilapidated condition of the wooden pavement in front of its location.

One consequence of having dirt cum mud streets got notice in the Statesman in 1895. The paper cautioned gentlemen to watch were they stepped because of the high number of toads in the road, especially at night. In the same edition, the columnist was relieved to see smoother pavement in front of Dangel’s because the walkway had become a bad place for sober gentlemen.

Throughout the early years of Boise, it was up to merchants to provide improved footing for customers. The Falk Brothers put in stone pavement in front of their store in 1888.

A big improvement in paving technology came along in 1889. As the Statesman said, “It seems somewhat surprising that an artificial compound should prove more durable than, and every way preferable to natural stone for pavement; but it is nevertheless a fact that the pavements made from Portland Cement excel the natural stone pavement in every respect.”

That was the same year W.A. Culver began advertising his services in artificial stone paving and cement pavements.

In 1890, the Statesman—which was dead set against gravel a few years earlier—called for the use of pulverized stone for the streets around town. And who would do the pulverizing? “the ‘vags’ and other petty criminals (could) be put to work breaking stone for such purpose.”

Finally, on April 18, 1897, the headline read, “Street Paving District Definitely Settled.” Sections of Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, Twelfth, Idaho, Main, Grove, Bannock, Jefferson and some related alleys were to be paved. The city council would require the contractor to employ Boise laborers exclusively, excepting the foreman. No wages would be less than $2 a day. Councilors wrote up the specifications and determined it would cost $4.50 a front foot.

The Statesman editorialized in its April 21 edition that the council was making a mistake in planning to do so much street paving. They wanted an emphasis on sidewalks, not street paving.

Alas, by May 4, the Council had a change of heart. Only five blocks of Main Street, from Fifth to Tenth, would get pavement.

But by June, paving that single street was going so well that local property owners began clambering more extensions to the paving district.

In July, the paper ran one of its “As Others See Us” columns, a reprint of an article from the Caldwell Record. “Main Street is being paved and it is certainly to the credit of its citizens that they are determined to retrieve the city from the mud and dust to which it has been subject and to make the capital of Idaho worthy of the name Boise the beautiful. It is to be remarked that trees and lawns are now bright and green and free from dust, something never before known at mid-summer in Boise.”

Now, more than 130 years later, as residents know, all the streets of Boise are paved and one never encounters a rough spot or controversy about the streets.

Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Boise, founded in 1863, was content—maybe resigned—in the early days to dusty roads on dry days and mud bogs when it rained. In 1867 the Idaho Statesman expressed pleasure to see a “nice piece of pavement” in from of Mr. Blossom and Bloch, Miller & Co. The paper asked, “When shall we see a mile of it in Boise City?” I can provide the answer from my time machine: about 30 years.

“Pavement” could mean a lot of things, depending on the situation. We think of asphalt today, or maybe concrete. In 1874, there was some paving of gutters in front of C.W. Moore’s First National Bank. The Statesman welcomed that but cautioned that no one should get the idea of hauling gravel in to make a roadbed. “There is no road so heavy and unpleasant in dry weather as deep gravel and sand. Our season is dry for two-thirds to three-fourths of the year. Suppose we have mud one-third or a fourth of the year, it is better go bear a bad road one-fourth of the time than three-fourths.”

In 1880, the Statesman was lauding “handsome wood pavement” in front of the Valley Store. This brings up another point of confusion. “Pavement” could also refer to sidewalks, not just streets. Three years later, the paper was chiding a local restaurant for the badly dilapidated condition of the wooden pavement in front of its location.

One consequence of having dirt cum mud streets got notice in the Statesman in 1895. The paper cautioned gentlemen to watch were they stepped because of the high number of toads in the road, especially at night. In the same edition, the columnist was relieved to see smoother pavement in front of Dangel’s because the walkway had become a bad place for sober gentlemen.

Throughout the early years of Boise, it was up to merchants to provide improved footing for customers. The Falk Brothers put in stone pavement in front of their store in 1888.

A big improvement in paving technology came along in 1889. As the Statesman said, “It seems somewhat surprising that an artificial compound should prove more durable than, and every way preferable to natural stone for pavement; but it is nevertheless a fact that the pavements made from Portland Cement excel the natural stone pavement in every respect.”

That was the same year W.A. Culver began advertising his services in artificial stone paving and cement pavements.

In 1890, the Statesman—which was dead set against gravel a few years earlier—called for the use of pulverized stone for the streets around town. And who would do the pulverizing? “the ‘vags’ and other petty criminals (could) be put to work breaking stone for such purpose.”

Finally, on April 18, 1897, the headline read, “Street Paving District Definitely Settled.” Sections of Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, Twelfth, Idaho, Main, Grove, Bannock, Jefferson and some related alleys were to be paved. The city council would require the contractor to employ Boise laborers exclusively, excepting the foreman. No wages would be less than $2 a day. Councilors wrote up the specifications and determined it would cost $4.50 a front foot.

The Statesman editorialized in its April 21 edition that the council was making a mistake in planning to do so much street paving. They wanted an emphasis on sidewalks, not street paving.

Alas, by May 4, the Council had a change of heart. Only five blocks of Main Street, from Fifth to Tenth, would get pavement.

But by June, paving that single street was going so well that local property owners began clambering more extensions to the paving district.

In July, the paper ran one of its “As Others See Us” columns, a reprint of an article from the Caldwell Record. “Main Street is being paved and it is certainly to the credit of its citizens that they are determined to retrieve the city from the mud and dust to which it has been subject and to make the capital of Idaho worthy of the name Boise the beautiful. It is to be remarked that trees and lawns are now bright and green and free from dust, something never before known at mid-summer in Boise.”

Now, more than 130 years later, as residents know, all the streets of Boise are paved and one never encounters a rough spot or controversy about the streets.

Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Published on October 20, 2024 04:00

October 19, 2024

The SS William E. Borah

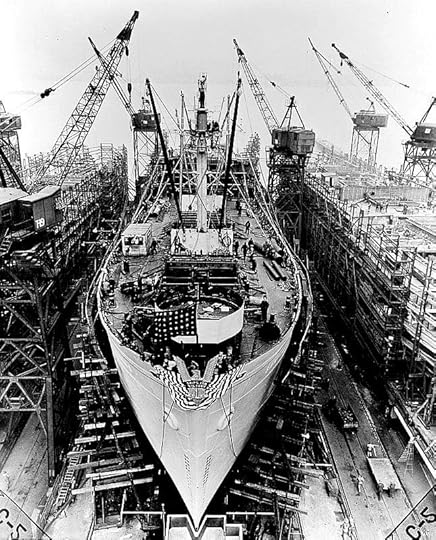

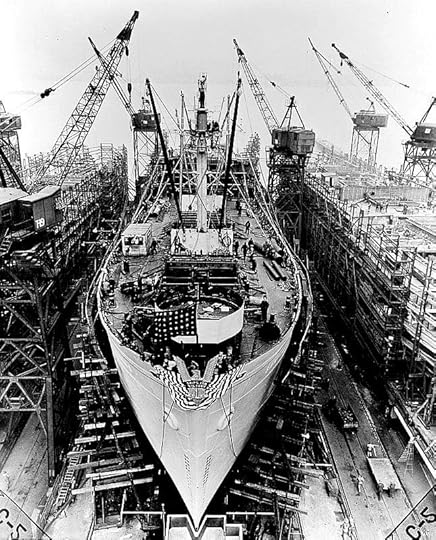

Following World War I, it became clear that America’s merchant marine fleet was becoming obsolete. In what would be a fortunate move prior to World War II, Congress passed the Merchant Marine Act of 1936. More than 2,700 mass-produced ships using pre-fabricated sections in their design, joined the fleet. They were officially called Liberty Ships. Famously, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, an aficionado of naval vessels, dubbed the ships “ugly ducklings.”

The Liberty Ships served their purpose going into the war, but it soon became apparent that they were too slow and too small to carry all the supplies needed for the war effort. The United States began a new program of shipbuilding in 1942. The faster, larger ships in this second wave were called Victory Ships.

On December 20, 1942, the Idaho Stateman announced that “Idaho’s victory ship, the William E. Borah, will slide down the ways at Portland, Ore., on Dec. 27.” Mary M. Borah, the widow of the late senator and Idaho’s Governor Chase Clark would be on hand to witness the launch.

Also invited to the ceremony were several Idaho school children who had won scrap-collecting contests. Though they probably didn’t collect enough scrap metal to build a ship, children from North Idaho and South Idaho met up in Portland for the event the day after Christmas.

The SS William E. Borah served the merchant fleet for 19 years before being scrapped in 1961, perhaps to serve again in some new form.

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship

The Liberty Ships served their purpose going into the war, but it soon became apparent that they were too slow and too small to carry all the supplies needed for the war effort. The United States began a new program of shipbuilding in 1942. The faster, larger ships in this second wave were called Victory Ships.

On December 20, 1942, the Idaho Stateman announced that “Idaho’s victory ship, the William E. Borah, will slide down the ways at Portland, Ore., on Dec. 27.” Mary M. Borah, the widow of the late senator and Idaho’s Governor Chase Clark would be on hand to witness the launch.

Also invited to the ceremony were several Idaho school children who had won scrap-collecting contests. Though they probably didn’t collect enough scrap metal to build a ship, children from North Idaho and South Idaho met up in Portland for the event the day after Christmas.

The SS William E. Borah served the merchant fleet for 19 years before being scrapped in 1961, perhaps to serve again in some new form.

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship

Published on October 19, 2024 04:00

October 17, 2024

Oryctodromeus

Idaho’s newest state symbol is also its oldest. Designated Idaho’s State Dinosaur in 2023, Oryctodromeus (or-ik-tow-drohm-ee-us) lived about 98 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period. That makes Idaho’s State Fossil, the Hagerman Horse, a relative newcomer, having lived here about 3.5 million years ago.

Paleontologist Dr. L. J. Krumenacker, an instructor at the College of Eastern Idaho, found the first fossilized remains of Oryctodromeus in the Caribou-Targhee National Forest in 2006. It was a lucky find since dinosaur fossils are rare in Idaho. Even so, Oryctodromeus is the most common dinosaur in the state.

Oryctodromeus was a burrowing dinosaur, so far the first to be discovered in the world. Oryctodromeus means “digging runner.” They would have been good at both. The herbivore’s burrows were large since the dinosaurs stood about 3 feet tall, weighed between 50 and 70 pounds, and were nearly 11 feet long. Most of that length—about 2/3 of it—was made up of tail.

White Pine Charter School students in Ammon convinced lawmakers to add Oryctodromeus to the state’s list of symbols. So far, fossils of this dinosaur have been found only in eastern Idaho and the southwest corner of Montana.

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Paleontologist Dr. L. J. Krumenacker, an instructor at the College of Eastern Idaho, found the first fossilized remains of Oryctodromeus in the Caribou-Targhee National Forest in 2006. It was a lucky find since dinosaur fossils are rare in Idaho. Even so, Oryctodromeus is the most common dinosaur in the state.

Oryctodromeus was a burrowing dinosaur, so far the first to be discovered in the world. Oryctodromeus means “digging runner.” They would have been good at both. The herbivore’s burrows were large since the dinosaurs stood about 3 feet tall, weighed between 50 and 70 pounds, and were nearly 11 feet long. Most of that length—about 2/3 of it—was made up of tail.

White Pine Charter School students in Ammon convinced lawmakers to add Oryctodromeus to the state’s list of symbols. So far, fossils of this dinosaur have been found only in eastern Idaho and the southwest corner of Montana.

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Published on October 17, 2024 04:00

October 16, 2024

Lady Bluebeard

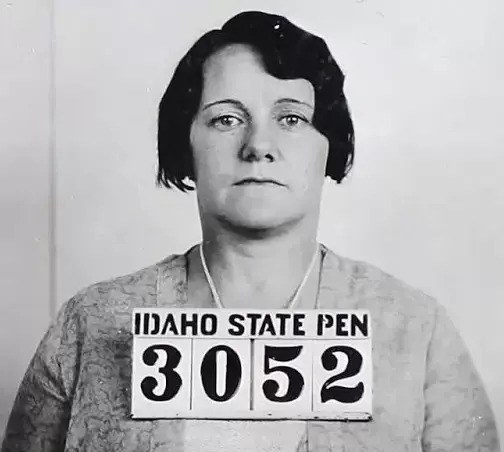

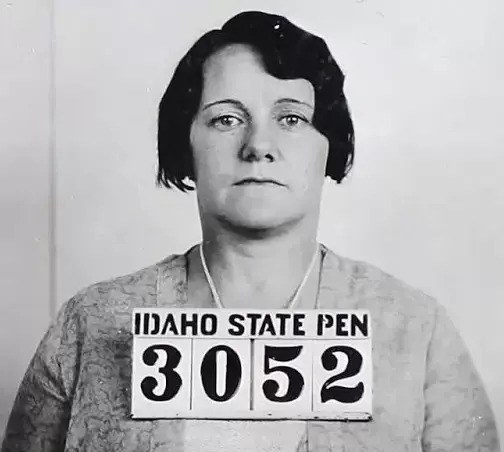

Most of the stories in this section are Idaho-related facts about famous people. Infamy was more Lyda Southard’s cup of tea. Don’t drink that tea! Southard, who had more names than a centipede has feet, caught one she didn’t seek: Lady Bluebeard.

The country’s first widely known female serial killer, Lyda, wasn’t born in Idaho. Her birthplace—in 1892—was a little town in Missouri. Her family moved to the Twin Falls area when she was a teenager.

Though she came from a poor family, Lyda found a way to make a good living. She worked in insurance.

Lyda collected husbands. She married Robert Dooley in 1912. They lived with Robert’s bachelor brother, Ed, on a farm near Twin Falls. The Dooleys had a daughter, Loraine (some accounts say Laura), in 1914.

In 1915, Lyda collected insurance money after the tragic deaths of her first husband, Robert, their daughter, and Robert’s brother, Ed. The deaths were chalked up to dirty well water, typhoid fever, and ptomaine poisoning, respectively.

Lyda was a looker, by some accounts. Her prison photo may not reflect that, but who looks good in their mugshot? She used her charms to marry another man in 1917, William G. McHaffle. McHaffle had a three-year-old daughter, but not for long. The daughter died shortly after they married. The newlyweds moved to Montana, where, in 1918, Mr. McHaffle, doubly unlucky, died of influenza and diphtheria. Lyda, always practical, collected the insurance money.

Then she got married again. She waited a respectful nearly five months before hitching to Harlan C. Lewis, an automobile salesman from Billings. Lewis lasted four months. He died from complications related to gastroenteritis.

It was just over a year before Lyda found her fourth husband, Edward F. Meyer, a ranch foreman from Twin Falls. Tragedy struck again, this time just a few weeks after the marriage when Meyer died from Typhoid. He did not go easily. A nurse noted how concerned Lyda was about his health and that she always seemed to be giving him sips of water. Alas, the water didn’t save him. The insurance payout this time was $12,000.

The coincidences surrounding this woman so unlucky in love began to raise the suspicions of Twin Falls Chemist Earl Dooley. The Dooley name was not a coincidence. The chemist was a relative of Lyda’s first husband. He pressed for an investigation. Said investigation found evidence of arsenic poisoning in the bodies of Lyda’s hapless husbands and in the cookware she had regularly used. They also found a large supply of flypaper in the basement of a house where she had lived. Flypaper at that time was coated with arsenic.

Meanwhile, Lyda wasn’t sitting still. A few weeks after Meyer’s death, she snagged Paul Southard. The Navy man resisted her insistence on buying life insurance, telling her the Navy would provide for her in the event of his death.

The happy couple was living in Honolulu when police came knocking. Paul Southard insisted that Lyda, his love, was innocent. After all, he’d known her well for several weeks.

When newspapers got wind of the charges against Lyda, they generated headlines about the “temptress,” the “Black Widow,” and the “Lady Bluebeard.” They followed every word in her seven-week trial.

The evidence against Lyda was circumstantial, but there was a ton of it. The jury was reluctant to sentence a pretty 29-year-old woman to death. They convicted her of second-degree murder. She got 10 years.

Ten years in prison kept Lyda off the husband track. Mostly. In 1931 she escaped with a prison trusty, David Minton, who had been released two weeks earlier. Lyda climbed out of her cell courtesy of a handmade rope and a rose trellis.

Authorities found Minton a few months later in Denver. He denied any connection to Lyda, but they soon picked up the trail. She was also in Denver, working as a housekeeper. She already had her clutches on a new man, Harry Whitlock. He was a bit more cautious than Lyda’s previous husbands. Whitlock flatly refused to let her take out a $20,000 insurance policy on him. He wasn’t surprised when the police showed up. Lyda, meanwhile, had skipped town.

Police caught up with Lyda in Kansas 15 months after her escape. She went back to prison in Idaho for another 10 years. Lyda was released in 1941 and pardoned in 1943.

Lyda’s movements after her release are a little sketchy. Eventually, she moved to Provo, Utah, and started a second-hand store. She also started her seventh marriage to a man named Hal Shaw. Shaw’s adult children found out who Lyda was. A divorce soon followed.

Lyda Shaw was the name chiseled onto her headstone in the Twin Falls cemetery. She had the last names of Trueblood, Dooley, McHaffie, Lewis, Meyer, Southard, and Whitlock. She’s most often remembered as Lyda Southard, since that’s the name she was using when she first entered prison. Lyda was sometimes Lydia on official records. Whatever you call her, she earned the title of murderess.

The country’s first widely known female serial killer, Lyda, wasn’t born in Idaho. Her birthplace—in 1892—was a little town in Missouri. Her family moved to the Twin Falls area when she was a teenager.

Though she came from a poor family, Lyda found a way to make a good living. She worked in insurance.

Lyda collected husbands. She married Robert Dooley in 1912. They lived with Robert’s bachelor brother, Ed, on a farm near Twin Falls. The Dooleys had a daughter, Loraine (some accounts say Laura), in 1914.

In 1915, Lyda collected insurance money after the tragic deaths of her first husband, Robert, their daughter, and Robert’s brother, Ed. The deaths were chalked up to dirty well water, typhoid fever, and ptomaine poisoning, respectively.

Lyda was a looker, by some accounts. Her prison photo may not reflect that, but who looks good in their mugshot? She used her charms to marry another man in 1917, William G. McHaffle. McHaffle had a three-year-old daughter, but not for long. The daughter died shortly after they married. The newlyweds moved to Montana, where, in 1918, Mr. McHaffle, doubly unlucky, died of influenza and diphtheria. Lyda, always practical, collected the insurance money.

Then she got married again. She waited a respectful nearly five months before hitching to Harlan C. Lewis, an automobile salesman from Billings. Lewis lasted four months. He died from complications related to gastroenteritis.

It was just over a year before Lyda found her fourth husband, Edward F. Meyer, a ranch foreman from Twin Falls. Tragedy struck again, this time just a few weeks after the marriage when Meyer died from Typhoid. He did not go easily. A nurse noted how concerned Lyda was about his health and that she always seemed to be giving him sips of water. Alas, the water didn’t save him. The insurance payout this time was $12,000.

The coincidences surrounding this woman so unlucky in love began to raise the suspicions of Twin Falls Chemist Earl Dooley. The Dooley name was not a coincidence. The chemist was a relative of Lyda’s first husband. He pressed for an investigation. Said investigation found evidence of arsenic poisoning in the bodies of Lyda’s hapless husbands and in the cookware she had regularly used. They also found a large supply of flypaper in the basement of a house where she had lived. Flypaper at that time was coated with arsenic.

Meanwhile, Lyda wasn’t sitting still. A few weeks after Meyer’s death, she snagged Paul Southard. The Navy man resisted her insistence on buying life insurance, telling her the Navy would provide for her in the event of his death.

The happy couple was living in Honolulu when police came knocking. Paul Southard insisted that Lyda, his love, was innocent. After all, he’d known her well for several weeks.

When newspapers got wind of the charges against Lyda, they generated headlines about the “temptress,” the “Black Widow,” and the “Lady Bluebeard.” They followed every word in her seven-week trial.

The evidence against Lyda was circumstantial, but there was a ton of it. The jury was reluctant to sentence a pretty 29-year-old woman to death. They convicted her of second-degree murder. She got 10 years.

Ten years in prison kept Lyda off the husband track. Mostly. In 1931 she escaped with a prison trusty, David Minton, who had been released two weeks earlier. Lyda climbed out of her cell courtesy of a handmade rope and a rose trellis.

Authorities found Minton a few months later in Denver. He denied any connection to Lyda, but they soon picked up the trail. She was also in Denver, working as a housekeeper. She already had her clutches on a new man, Harry Whitlock. He was a bit more cautious than Lyda’s previous husbands. Whitlock flatly refused to let her take out a $20,000 insurance policy on him. He wasn’t surprised when the police showed up. Lyda, meanwhile, had skipped town.

Police caught up with Lyda in Kansas 15 months after her escape. She went back to prison in Idaho for another 10 years. Lyda was released in 1941 and pardoned in 1943.

Lyda’s movements after her release are a little sketchy. Eventually, she moved to Provo, Utah, and started a second-hand store. She also started her seventh marriage to a man named Hal Shaw. Shaw’s adult children found out who Lyda was. A divorce soon followed.

Lyda Shaw was the name chiseled onto her headstone in the Twin Falls cemetery. She had the last names of Trueblood, Dooley, McHaffie, Lewis, Meyer, Southard, and Whitlock. She’s most often remembered as Lyda Southard, since that’s the name she was using when she first entered prison. Lyda was sometimes Lydia on official records. Whatever you call her, she earned the title of murderess.

Published on October 16, 2024 04:00

October 15, 2024

Buckskin Bill

Idaho has long sent a siren song to people who want to escape the world. “Buckskin Bill,” sometimes called the Last of the Mountain Men, may be the best known.

We associate mountain men with the fur-trapping era of the 1800s. Sylvan Hart, who became known as “Buckskin Bill,” turned into a man of the mountains nearly a century later in 1932. He started his adventure as a way to ride out the depression. He stayed for the rest of his life.

Hart believed in education. He attended four colleges, getting a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Oklahoma. It was for his continuing education that he became a hermit living on the banks of the Salmon River. In Cort Conley’s excellent book, Idaho Loners, he quotes Hart as saying, “I wasn’t trying to run away from anything. I was Just a natural born student, and I could study there, investigate for myself, and I could experiment with different things. I’m not going to give up on education. I doesn’t pay to stop. Once you get really dumb, there’s no redemption for you.”

Hart, along with his father, Artie, picked a spot on Five Mile Bar to live off the land. Artie eventually had enough of the Salmon River Country and moved into town. Sylvan stayed on, winter after long winter, spending six months at a time without seeing a soul.

“Buckskin Bill” tended a large garden, hunted, and panned a little gold for his living. He got his name from Don Oberbillig, who lived at Mackay Bar three miles down the river. Buckskin was what Hart wore. Where “Bill” came from is not exactly clear. Alliteration probably played a part.

Hermits are famously drop-outs from society. Hart ran against type in that respect. When he heard about Pearl Harbor, a few months after the event, he hiked out to Grangeville to join the Army. They wouldn’t have him because of an enlarged heart and because at 35, he was a little old for the front lines.

Hart still wanted to help in the war effort. He got himself to Wichita, Kansas where he took a job as a toolmaker with Boeing.

In 1942, with the war roaring, the Army lowered its standards for inductees. They inducted Sylvan Hart and posted him to Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands. The Japanese had taken over the remote territory. Hart’s group was meant to oust them, but they left before he saw any action. Oddly, the FBI had been looking for him, thinking he was a draft dodger.

The Army sent Hart to Colorado, where he helped develop a top-secret bombsight.

Shortly after the war ended, he drifted back to his home in Idaho. Back to gardening, hunting, fishing, and making. He made everything he used, from kitchen utensils to guns. His flintlock rifles, which took a year to make, were hand-rifled and hand-bored, with elaborately carved wooden stocks.

Buckskin Bill’s brush with the FBI was a mistake. His brush with the IRS was purposeful bureaucracy. He didn’t care much for money. Many of his checks from his Army days went uncashed so long that they expired. He didn’t feel an obligation to pay taxes since, by his estimation, he didn’t make $500 a year. The IRS had a different math. They sent him threatening letters because of his lack of filings. So, Sylvan Hart turned himself in, arriving in Boise in full “Buckskin Bill” regalia.

Hart set up camp in the IRS office. He rolled out his sleeping bag on the floor and brewed a pot of tea. A supervisor was summoned. Bill offered him a cup of tea. He explained to the IRS that he was ready to go to prison, if need be. He had brought along a supply of pemmican for his stay. Recognizing that this wasn’t your average tax scofflaw, IRS officials sent him back to Five Mile Bar and never bothered him again.

But the world wouldn’t leave Buckskin Bill alone. In 1966, a writer for Sports Illustrated showed up on his doorstep. The resulting article, titled, “The Last of the Mountain Men,” assured that Buckskin Bill would never be anonymous again. An expanded version of the story came out in book form a few years later.

This new-found fame didn’t bother Sylvan Hart, the sometimes hermit. He loved to regale rafters and hikers with stories about his life in the Salmon River Country. Buckskin Bill became a celebrity of the backcountry, enjoying his solitude and fame in equal measures.

In 1980, Buckskin Bill passed away, making it just shy of 74 years. Friends conducted his funeral in Grangeville, then flew his body to Mackay Bar to be hauled upriver by boat. He was interred on his Five Mile Bar property, which remains a popular spot for rafters to visit today.

We associate mountain men with the fur-trapping era of the 1800s. Sylvan Hart, who became known as “Buckskin Bill,” turned into a man of the mountains nearly a century later in 1932. He started his adventure as a way to ride out the depression. He stayed for the rest of his life.

Hart believed in education. He attended four colleges, getting a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Oklahoma. It was for his continuing education that he became a hermit living on the banks of the Salmon River. In Cort Conley’s excellent book, Idaho Loners, he quotes Hart as saying, “I wasn’t trying to run away from anything. I was Just a natural born student, and I could study there, investigate for myself, and I could experiment with different things. I’m not going to give up on education. I doesn’t pay to stop. Once you get really dumb, there’s no redemption for you.”

Hart, along with his father, Artie, picked a spot on Five Mile Bar to live off the land. Artie eventually had enough of the Salmon River Country and moved into town. Sylvan stayed on, winter after long winter, spending six months at a time without seeing a soul.

“Buckskin Bill” tended a large garden, hunted, and panned a little gold for his living. He got his name from Don Oberbillig, who lived at Mackay Bar three miles down the river. Buckskin was what Hart wore. Where “Bill” came from is not exactly clear. Alliteration probably played a part.

Hermits are famously drop-outs from society. Hart ran against type in that respect. When he heard about Pearl Harbor, a few months after the event, he hiked out to Grangeville to join the Army. They wouldn’t have him because of an enlarged heart and because at 35, he was a little old for the front lines.

Hart still wanted to help in the war effort. He got himself to Wichita, Kansas where he took a job as a toolmaker with Boeing.

In 1942, with the war roaring, the Army lowered its standards for inductees. They inducted Sylvan Hart and posted him to Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands. The Japanese had taken over the remote territory. Hart’s group was meant to oust them, but they left before he saw any action. Oddly, the FBI had been looking for him, thinking he was a draft dodger.

The Army sent Hart to Colorado, where he helped develop a top-secret bombsight.

Shortly after the war ended, he drifted back to his home in Idaho. Back to gardening, hunting, fishing, and making. He made everything he used, from kitchen utensils to guns. His flintlock rifles, which took a year to make, were hand-rifled and hand-bored, with elaborately carved wooden stocks.

Buckskin Bill’s brush with the FBI was a mistake. His brush with the IRS was purposeful bureaucracy. He didn’t care much for money. Many of his checks from his Army days went uncashed so long that they expired. He didn’t feel an obligation to pay taxes since, by his estimation, he didn’t make $500 a year. The IRS had a different math. They sent him threatening letters because of his lack of filings. So, Sylvan Hart turned himself in, arriving in Boise in full “Buckskin Bill” regalia.

Hart set up camp in the IRS office. He rolled out his sleeping bag on the floor and brewed a pot of tea. A supervisor was summoned. Bill offered him a cup of tea. He explained to the IRS that he was ready to go to prison, if need be. He had brought along a supply of pemmican for his stay. Recognizing that this wasn’t your average tax scofflaw, IRS officials sent him back to Five Mile Bar and never bothered him again.

But the world wouldn’t leave Buckskin Bill alone. In 1966, a writer for Sports Illustrated showed up on his doorstep. The resulting article, titled, “The Last of the Mountain Men,” assured that Buckskin Bill would never be anonymous again. An expanded version of the story came out in book form a few years later.

This new-found fame didn’t bother Sylvan Hart, the sometimes hermit. He loved to regale rafters and hikers with stories about his life in the Salmon River Country. Buckskin Bill became a celebrity of the backcountry, enjoying his solitude and fame in equal measures.

In 1980, Buckskin Bill passed away, making it just shy of 74 years. Friends conducted his funeral in Grangeville, then flew his body to Mackay Bar to be hauled upriver by boat. He was interred on his Five Mile Bar property, which remains a popular spot for rafters to visit today.

Published on October 15, 2024 04:00

October 14, 2024

Idaho's First Railroad

The first train rolled into Idaho in 1874. The railroad, built by Mormon investors to serve LDS communities in Northern Utah and Southern Idaho, brought its first steam engine into Franklin that year. Before 1874, Corrine, Utah, was the nearest railroad station to Idaho. Upon successful completion of the Utah Northern Line to Franklin, many suppliers from Corrine set up satellite operations in Idaho’s first town.

The Utah Northern was intended to go at least to Soda Springs, but financial problems put the kibosh to that. The railroad, promoted by John H. Young—the son of Brigham—went bankrupt by 1878.

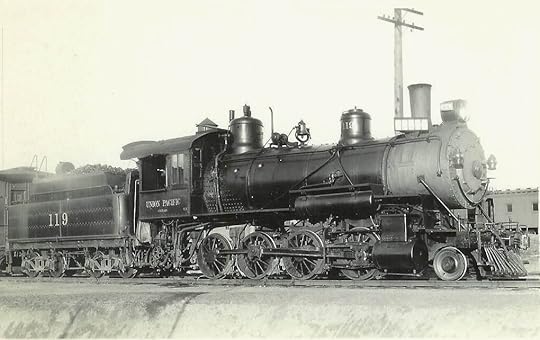

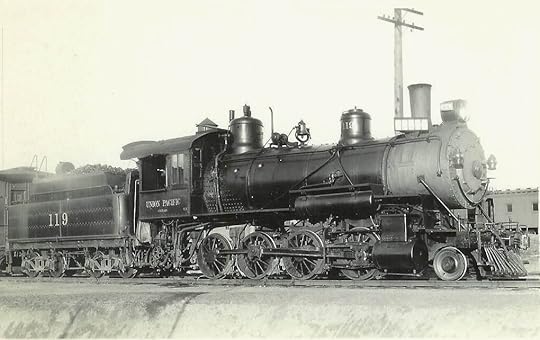

But Idaho’s railroad history was far from over. That first line to Franklin was quickly taken over by Union Pacific. At the peak, there were 2,877 miles of track crisscrossing Idaho. That peak was in 1920. Today, about 1,630 miles of track are in regular use in the state. By trains, that is. You can still hike and bike some of those abandoned rail lines, notably the Trail of the Hiawatha, Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, the Ashton-Tetonia Trail, and the Weiser River Trail. This Union Pacific engine traveled the tracks between Ashton and West Yellowstone in 1930. You can take most of that route today on your bicycle on the Ashton-Tetonia Trail.

This Union Pacific engine traveled the tracks between Ashton and West Yellowstone in 1930. You can take most of that route today on your bicycle on the Ashton-Tetonia Trail.

The Utah Northern was intended to go at least to Soda Springs, but financial problems put the kibosh to that. The railroad, promoted by John H. Young—the son of Brigham—went bankrupt by 1878.

But Idaho’s railroad history was far from over. That first line to Franklin was quickly taken over by Union Pacific. At the peak, there were 2,877 miles of track crisscrossing Idaho. That peak was in 1920. Today, about 1,630 miles of track are in regular use in the state. By trains, that is. You can still hike and bike some of those abandoned rail lines, notably the Trail of the Hiawatha, Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, the Ashton-Tetonia Trail, and the Weiser River Trail.

This Union Pacific engine traveled the tracks between Ashton and West Yellowstone in 1930. You can take most of that route today on your bicycle on the Ashton-Tetonia Trail.

This Union Pacific engine traveled the tracks between Ashton and West Yellowstone in 1930. You can take most of that route today on your bicycle on the Ashton-Tetonia Trail.

Published on October 14, 2024 04:00

October 13, 2024

The Whole Place Slippin' Away

I’ve written about Idaho songs and songs that mention Idaho several times. A reader recently pointed out that I hadn’t written about one of my favorites.

In March of 1969, I found myself spending a few weeks in Los Angeles. My brother Kent, and I, along with a friend, went down there for radio school. When I say radio school, you probably envision some kind of repair course or maybe something to do with ham radio. Or you might assume we were going there to learn how to be radio announcers. There were several schools in L.A. at that time devoted to the profession. But, no, we were already radio announcers.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) at that time required announcers to have either a third-class FCC license or a first-class license. Both licenses required taking a test. We already had our third-class licenses. That test was easy. You had to study for about eleven minutes to pass it. A third-class permit allowed you to work on low-powered stations. If you wanted to work at higher power stations and those with antenna arrays, you had to pass the test to become a first-class radio engineer. This was a hold-over from the early days of radio when you actually had to know something to operate a transmitter. By 1969, radio transmitters largely ran themselves. I knew how to turn one on and off and how to read the meters. If the meters were straying out of a certain tolerance range, you called the station engineer. He knew electronic stuff.

To move up in radio, you had to pass a very difficult test in engineering. Your average DJ knows squat about engineering, but they had to have that first-class license to work on, for instance, KBOI. This idiotic requirement meant that ambitious DJs, such as us, went to six-week schools to learn enough about electronics to pass the test.

So, there we were in Los Angeles, learning about capacitors and stuff. On the way to the day-long classes, we learned how to be a big-time DJ from the likes of Robert W. Morgan and Charlie Tuna on the monster L.A. rocker of the day, KHJ. This was a particularly cool thing for us because we knew those guys (long distance) from their stints on KOMA, Oklahoma City, which blasted into Southern Idaho during our high school days.

One of the songs we heard a lot when we were down there (this is about a song, remember?) was called Day after Day (It’s Slippin’ Away). This catchy little Caribbean-inspired tune was performed by the rock group Shango. As newbie sorta Angelenos from Idaho, who got to experience an earthquake while we were there, this song hit home. Here are some of the lyrics, courtesy of genius.com.

Day after day

More people come to L.A

Shhh! Don't you tell anybody

The whole place slippin' away

Where can we go

When there's no San Francisco?

Shhh! Better get ready

To tie up the boat in Idaho

And, there you have it. One of my favorite songs to include Idaho in the lyrics. Listen to it here.

This was Shango’s only hit. Well, maybe not a hit, but it did make number 57 on the pop charts. With no more hits coming, Shango broke up.

Two members went on to play in groups you may have heard of. Tommy Reynolds became the third name in Hamilton, Joe Frank & Reynolds. Drummer Joe Barile went on to play with the Ventures. To my knowledge, they never sang about Idaho again.

In March of 1969, I found myself spending a few weeks in Los Angeles. My brother Kent, and I, along with a friend, went down there for radio school. When I say radio school, you probably envision some kind of repair course or maybe something to do with ham radio. Or you might assume we were going there to learn how to be radio announcers. There were several schools in L.A. at that time devoted to the profession. But, no, we were already radio announcers.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) at that time required announcers to have either a third-class FCC license or a first-class license. Both licenses required taking a test. We already had our third-class licenses. That test was easy. You had to study for about eleven minutes to pass it. A third-class permit allowed you to work on low-powered stations. If you wanted to work at higher power stations and those with antenna arrays, you had to pass the test to become a first-class radio engineer. This was a hold-over from the early days of radio when you actually had to know something to operate a transmitter. By 1969, radio transmitters largely ran themselves. I knew how to turn one on and off and how to read the meters. If the meters were straying out of a certain tolerance range, you called the station engineer. He knew electronic stuff.

To move up in radio, you had to pass a very difficult test in engineering. Your average DJ knows squat about engineering, but they had to have that first-class license to work on, for instance, KBOI. This idiotic requirement meant that ambitious DJs, such as us, went to six-week schools to learn enough about electronics to pass the test.

So, there we were in Los Angeles, learning about capacitors and stuff. On the way to the day-long classes, we learned how to be a big-time DJ from the likes of Robert W. Morgan and Charlie Tuna on the monster L.A. rocker of the day, KHJ. This was a particularly cool thing for us because we knew those guys (long distance) from their stints on KOMA, Oklahoma City, which blasted into Southern Idaho during our high school days.

One of the songs we heard a lot when we were down there (this is about a song, remember?) was called Day after Day (It’s Slippin’ Away). This catchy little Caribbean-inspired tune was performed by the rock group Shango. As newbie sorta Angelenos from Idaho, who got to experience an earthquake while we were there, this song hit home. Here are some of the lyrics, courtesy of genius.com.

Day after day

More people come to L.A

Shhh! Don't you tell anybody

The whole place slippin' away

Where can we go

When there's no San Francisco?

Shhh! Better get ready

To tie up the boat in Idaho

And, there you have it. One of my favorite songs to include Idaho in the lyrics. Listen to it here.

This was Shango’s only hit. Well, maybe not a hit, but it did make number 57 on the pop charts. With no more hits coming, Shango broke up.

Two members went on to play in groups you may have heard of. Tommy Reynolds became the third name in Hamilton, Joe Frank & Reynolds. Drummer Joe Barile went on to play with the Ventures. To my knowledge, they never sang about Idaho again.

Published on October 13, 2024 04:00

October 12, 2024

Dr. Hope

Hope, perhaps the most optimistically named town in Idaho, was not named because of any great opportunity that seemed just over the horizon. It was named after Dr. Hope, a railroad veterinarian, so little remembered that we don’t even know his given name.

And that’s about the end of the story of how Hope got its name. But to me, that’s not the real story in the last sentence of the paragraph above. The story is in the title “railroad veterinarian.” Why would a railroad at the turn of the century—Hope was incorporated in 1903—need a veterinarian?

Railroads, tramways, and trollies existed long before steam engines. The first passenger railway was the Swansea and Mumbles Railway, which operated in Wales from 1804 to 1877. It was a horse-drawn railway at first, though it was later electrified. Horses also pulled loads out of mines on rails for decades and trudged along ahead of countless trollies.

It seemed to me that once steam engines came along, railroad veterinarians would have outlived their usefulness. But, as it turns out, horses were used to move railcars in and out of yards, to pull cars up steep inclines, and to transport goods to and from the rail yard. Horses were also used to transport railroad workers and to pull maintenance equipment along the tracks. The horses used by railroads were often large, strong draft horses such as Percherons, Belgians, and Clydesdales. So, there was a need for a Dr. Hope.

And that’s about the end of the story of how Hope got its name. But to me, that’s not the real story in the last sentence of the paragraph above. The story is in the title “railroad veterinarian.” Why would a railroad at the turn of the century—Hope was incorporated in 1903—need a veterinarian?

Railroads, tramways, and trollies existed long before steam engines. The first passenger railway was the Swansea and Mumbles Railway, which operated in Wales from 1804 to 1877. It was a horse-drawn railway at first, though it was later electrified. Horses also pulled loads out of mines on rails for decades and trudged along ahead of countless trollies.

It seemed to me that once steam engines came along, railroad veterinarians would have outlived their usefulness. But, as it turns out, horses were used to move railcars in and out of yards, to pull cars up steep inclines, and to transport goods to and from the rail yard. Horses were also used to transport railroad workers and to pull maintenance equipment along the tracks. The horses used by railroads were often large, strong draft horses such as Percherons, Belgians, and Clydesdales. So, there was a need for a Dr. Hope.

Published on October 12, 2024 04:00