Rick Just's Blog, page 11

September 21, 2024

A Pilot Making History

Idaho has a long aviation history, from the first commercial airmail service to wartime heroes like Pappy Boyington. Anneliese Satz, who grew up in Boise, added to that history in 2019.

Captain Satz became the first female Marine to pilot an F35B fighter jet. The F35B Lightning is a short takeoff/vertical landing aircraft that can reach speeds of 1,200 mph.

Satz is probably also the only member of the Shoshone Bannock Tribes to pilot such an aircraft. She still has family living on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Southeast Idaho. She is a descendent of Chief Tahgee (Targhee). And, it’s likely she and her husband, Captain Anthony Pompei, are the only married couple flying the jets.

Satz was based in Japan with the Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 when this was written. She has been in the Marine Corps since 2014. Prior to joining the service, Satz was a commercial helicopter pilot. She’s a graduate of Boise High School and Boise State University. Capt. Anneliese Satz puts on her flight helmet prior to a training flight aboard Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort. Satz graduated the F-35B Lighting II Pilot Training Program June, 2019 and is assigned to Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 in Iwakuni, Japan. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Ashley Phillips)

Capt. Anneliese Satz puts on her flight helmet prior to a training flight aboard Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort. Satz graduated the F-35B Lighting II Pilot Training Program June, 2019 and is assigned to Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 in Iwakuni, Japan. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Ashley Phillips)  Senator Mike Crapo honoring Capt. Anneliese Satz and her husband, Capt. Anthony Pompei.

Senator Mike Crapo honoring Capt. Anneliese Satz and her husband, Capt. Anthony Pompei.

Captain Satz became the first female Marine to pilot an F35B fighter jet. The F35B Lightning is a short takeoff/vertical landing aircraft that can reach speeds of 1,200 mph.

Satz is probably also the only member of the Shoshone Bannock Tribes to pilot such an aircraft. She still has family living on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Southeast Idaho. She is a descendent of Chief Tahgee (Targhee). And, it’s likely she and her husband, Captain Anthony Pompei, are the only married couple flying the jets.

Satz was based in Japan with the Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 when this was written. She has been in the Marine Corps since 2014. Prior to joining the service, Satz was a commercial helicopter pilot. She’s a graduate of Boise High School and Boise State University.

Capt. Anneliese Satz puts on her flight helmet prior to a training flight aboard Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort. Satz graduated the F-35B Lighting II Pilot Training Program June, 2019 and is assigned to Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 in Iwakuni, Japan. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Ashley Phillips)

Capt. Anneliese Satz puts on her flight helmet prior to a training flight aboard Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort. Satz graduated the F-35B Lighting II Pilot Training Program June, 2019 and is assigned to Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 in Iwakuni, Japan. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Ashley Phillips)  Senator Mike Crapo honoring Capt. Anneliese Satz and her husband, Capt. Anthony Pompei.

Senator Mike Crapo honoring Capt. Anneliese Satz and her husband, Capt. Anthony Pompei.

Published on September 21, 2024 04:00

September 20, 2024

Boise City's City Halls

Boise’s council and mayor didn’t have a home in the city's earliest years. It wouldn’t have mattered much if they did because they kept resigning and refusing to serve. Although the city was created in 1863, not everyone was thrilled with the idea of it being a city. It wasn’t until 1867 that a bona fide city council and mayor started meeting. They met wherever they could until the late 1870s when they settled on sharing a site with the volunteer fire department at 619 Main in a former blacksmith shop.

The fire station (irony alert) burned in 1883, so the city built a new, two-story structure called City Hall Station. The second story became the home of the city council and mayor. Idaho Blueprint was located there for 113 years before closing in 2022.

By 1891, the capital city of a newly minted state needed a new city hall. Voters approved the expenditure of $40,000 to build one. I’ll pause here to let you ruminate over the fact that you’d be hard-pressed to add a garage to a modest house today for that price. Done? Moving on.

City fathers selected Richard Johnson, the architect of the fabled Boise Natatorium, to design the structure. The Romanesque Revival structure was completed in 1893 on the southeast corner of Idaho and 8th streets. The Council chamber on the third floor of the building was decked out in curved oak rafters with a soaring ceiling. It was a building to be proud of.

All things age. By 1947 the functions of the city were crammed into spaces too small to… function. The cellar housed the police department. It was described by The Idaho Statesman as “foul-smelling” and “medieval.”

In 1948, the City of Boise purchased a former Ada County building at 6th and Bannock and converted it into the new City Hall. Meanwhile, after failed attempts to sell the beloved/loathed old City Hall, the red brick building at 8th and Idaho was torn down.

As the Steve Miller Band noted, time keeps slipping into the future. By the late 60s, it was time to start looking for a new city hall site. This time, city leaders picked the entire block between Capitol, 6th, Main, and Idaho streets for a new building. Built in 1975, City Hall has undergone some renovations and narrowly escaped an earthquake disaster. The most recent upgrade was the removal of the flag plaza in front of the building, replacing it with a more accessible, cleaner-looking plaza featuring metal sculptures that the public seems to find more interesting than the controversial metal “window frames” that once lived there.

Boise's first city hall/fire station is hiding here behind the power pole in the center.

Boise's first city hall/fire station is hiding here behind the power pole in the center.

The fire station (irony alert) burned in 1883, so the city built a new, two-story structure called City Hall Station. The second story became the home of the city council and mayor. Idaho Blueprint was located there for 113 years before closing in 2022.

By 1891, the capital city of a newly minted state needed a new city hall. Voters approved the expenditure of $40,000 to build one. I’ll pause here to let you ruminate over the fact that you’d be hard-pressed to add a garage to a modest house today for that price. Done? Moving on.

City fathers selected Richard Johnson, the architect of the fabled Boise Natatorium, to design the structure. The Romanesque Revival structure was completed in 1893 on the southeast corner of Idaho and 8th streets. The Council chamber on the third floor of the building was decked out in curved oak rafters with a soaring ceiling. It was a building to be proud of.

All things age. By 1947 the functions of the city were crammed into spaces too small to… function. The cellar housed the police department. It was described by The Idaho Statesman as “foul-smelling” and “medieval.”

In 1948, the City of Boise purchased a former Ada County building at 6th and Bannock and converted it into the new City Hall. Meanwhile, after failed attempts to sell the beloved/loathed old City Hall, the red brick building at 8th and Idaho was torn down.

As the Steve Miller Band noted, time keeps slipping into the future. By the late 60s, it was time to start looking for a new city hall site. This time, city leaders picked the entire block between Capitol, 6th, Main, and Idaho streets for a new building. Built in 1975, City Hall has undergone some renovations and narrowly escaped an earthquake disaster. The most recent upgrade was the removal of the flag plaza in front of the building, replacing it with a more accessible, cleaner-looking plaza featuring metal sculptures that the public seems to find more interesting than the controversial metal “window frames” that once lived there.

Boise's first city hall/fire station is hiding here behind the power pole in the center.

Boise's first city hall/fire station is hiding here behind the power pole in the center.

Published on September 20, 2024 04:00

September 19, 2024

Mining Camp Cats

Cats are popular pets today, prized for their personalities and purring. In the 1860s, in Placerville and other mining camps in Idaho, cats were prized for their ability to keep rodents at bay. According to memories of one resident recounted in a 1934 edition of the Idaho Statesman, miners’ cabins were often overrun with field mice and chipmunks.

An enterprising man named Mooney from somewhere in Oregon sold pest control cats in the mining camps. They were common gray tabbies with no claim to pedigree, but they brought $10 each. That would be more than $300 in today’s money.

Mr. Mooney stayed overnight with the Moores of Placerville and gave a pair of kittens to little Lizzie. In later years, Lizzie (then Mrs. Sisk) told of litter after litter of kittens that came along, fetching $2.50 for each tiny cat. For many years thereafter, Placerville was known as the home to large gray cats, kept fed by an endless supply of mice.

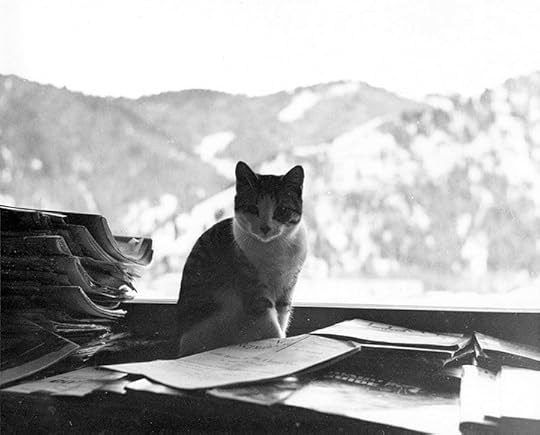

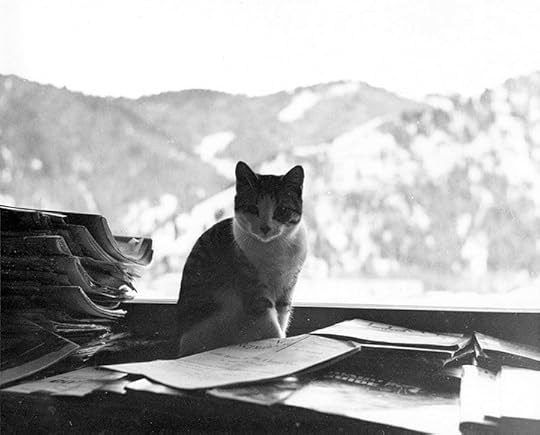

This cat didn't have to earn his keep in a mining camp. Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

This cat didn't have to earn his keep in a mining camp. Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

An enterprising man named Mooney from somewhere in Oregon sold pest control cats in the mining camps. They were common gray tabbies with no claim to pedigree, but they brought $10 each. That would be more than $300 in today’s money.

Mr. Mooney stayed overnight with the Moores of Placerville and gave a pair of kittens to little Lizzie. In later years, Lizzie (then Mrs. Sisk) told of litter after litter of kittens that came along, fetching $2.50 for each tiny cat. For many years thereafter, Placerville was known as the home to large gray cats, kept fed by an endless supply of mice.

This cat didn't have to earn his keep in a mining camp. Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

This cat didn't have to earn his keep in a mining camp. Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Published on September 19, 2024 04:00

September 18, 2024

The Photos of Benedicte Wrensted

Benedicte Wrensted was a photographer when females photographers were rare. She had a shop in Pocatello from 1895 to 1912. Her interest in taking pictures of the residents of the nearby Fort Hall Indian Reservation went largely unremarked in her time. Those she took pictures of treasured them and took them home to display.

It wasn’t until 1984 that her work began to come to light when anthropologist Joanna Coan Scherer discovered a collection of negatives at the National Archives labled,

“Portraits of Indians from Sotheastern Idaho Resevations, 1897.” In Scherer’s opinion the portraits were remarkable for their compelling depiction of the humanity of the photographer’s subjects. Later, Scherer connected the negatives to Wrensted through a collection of photographs housed at the Bannock County Historical Society.

You can learn more about Wrensted through the website Benedicte Wrenstead: An Idaho Photographer in Focus . She was also feature, along with photographer Jane Gay, in the Idaho Public Television program Out of the Shadows .

A Wrensted photo of a Shoshone girl circa 1897.

A Wrensted photo of a Shoshone girl circa 1897.  Left to right: Sonnip or Pohaipe family member, James Edmo, and Jack Edmo. Taken about 1901 by Benedicte Wrensted

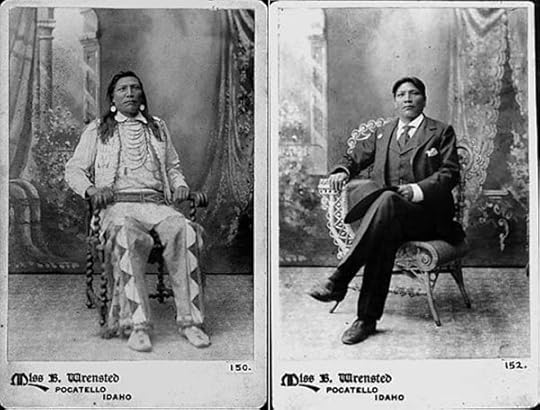

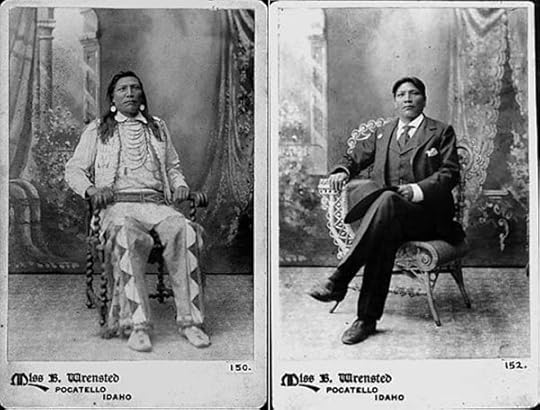

Left to right: Sonnip or Pohaipe family member, James Edmo, and Jack Edmo. Taken about 1901 by Benedicte Wrensted  These are before and after photos of Pat Tyhee taken by Wrensted. The before shot shows him in native clothing. The after shows Tyhee with a new suit of clothes and a haircut.

These are before and after photos of Pat Tyhee taken by Wrensted. The before shot shows him in native clothing. The after shows Tyhee with a new suit of clothes and a haircut.  Portrait by Benedicte Wrensted of Pohene and Frank George, Lemhi Shoshone and Northern Shoshone (ca. 1897)

Portrait by Benedicte Wrensted of Pohene and Frank George, Lemhi Shoshone and Northern Shoshone (ca. 1897)  Benedicte Wrensted (1859-1949), a native of Denmark, arrived in the United States in 1894. She was a professional photographer in Pocatello, Idaho from 1895 to 1912.

Benedicte Wrensted (1859-1949), a native of Denmark, arrived in the United States in 1894. She was a professional photographer in Pocatello, Idaho from 1895 to 1912.

It wasn’t until 1984 that her work began to come to light when anthropologist Joanna Coan Scherer discovered a collection of negatives at the National Archives labled,

“Portraits of Indians from Sotheastern Idaho Resevations, 1897.” In Scherer’s opinion the portraits were remarkable for their compelling depiction of the humanity of the photographer’s subjects. Later, Scherer connected the negatives to Wrensted through a collection of photographs housed at the Bannock County Historical Society.

You can learn more about Wrensted through the website Benedicte Wrenstead: An Idaho Photographer in Focus . She was also feature, along with photographer Jane Gay, in the Idaho Public Television program Out of the Shadows .

A Wrensted photo of a Shoshone girl circa 1897.

A Wrensted photo of a Shoshone girl circa 1897.  Left to right: Sonnip or Pohaipe family member, James Edmo, and Jack Edmo. Taken about 1901 by Benedicte Wrensted

Left to right: Sonnip or Pohaipe family member, James Edmo, and Jack Edmo. Taken about 1901 by Benedicte Wrensted  These are before and after photos of Pat Tyhee taken by Wrensted. The before shot shows him in native clothing. The after shows Tyhee with a new suit of clothes and a haircut.

These are before and after photos of Pat Tyhee taken by Wrensted. The before shot shows him in native clothing. The after shows Tyhee with a new suit of clothes and a haircut.  Portrait by Benedicte Wrensted of Pohene and Frank George, Lemhi Shoshone and Northern Shoshone (ca. 1897)

Portrait by Benedicte Wrensted of Pohene and Frank George, Lemhi Shoshone and Northern Shoshone (ca. 1897)  Benedicte Wrensted (1859-1949), a native of Denmark, arrived in the United States in 1894. She was a professional photographer in Pocatello, Idaho from 1895 to 1912.

Benedicte Wrensted (1859-1949), a native of Denmark, arrived in the United States in 1894. She was a professional photographer in Pocatello, Idaho from 1895 to 1912.

Published on September 18, 2024 04:00

September 17, 2024

A Disaster in Turner, Idaho

Before rural electrification, many small communities relied on acetylene lighting systems, sometimes with disastrous results.

On the evening of January 27, 1927, there was a basketball game in Turner, Idaho, near present-day Grace. The boys were playing rivals from nearby Central, Idaho. About 200 people turned out for the match, which was held at the Mormon Chapel and Recreation Hall.

The game had just begun in the one-story frame building when the lights went out. Janitor James McCann went down into the basement to check on the acetylene tanks and lighting notoriously cranky system. Meanwhile, the crowd had started to make its way out of the only exit in the dark. Someone lit a match.

The explosion blew out the rear wall of the building. A portion of the ceiling fell, dropping timbers and plaster into the crowd. Soon, the front wall collapsed as well. When everyone was accounted for, dozens were injured, and six lay dead.

Janitor McCann was among the dead, as were his two sons and his brother, Brigham.

On the evening of January 27, 1927, there was a basketball game in Turner, Idaho, near present-day Grace. The boys were playing rivals from nearby Central, Idaho. About 200 people turned out for the match, which was held at the Mormon Chapel and Recreation Hall.

The game had just begun in the one-story frame building when the lights went out. Janitor James McCann went down into the basement to check on the acetylene tanks and lighting notoriously cranky system. Meanwhile, the crowd had started to make its way out of the only exit in the dark. Someone lit a match.

The explosion blew out the rear wall of the building. A portion of the ceiling fell, dropping timbers and plaster into the crowd. Soon, the front wall collapsed as well. When everyone was accounted for, dozens were injured, and six lay dead.

Janitor McCann was among the dead, as were his two sons and his brother, Brigham.

Published on September 17, 2024 04:00

September 16, 2024

This Post is Bull

In the August 23, 1937 edition of the Idaho Statesman, Walt Beesley wrote, “Goin to heaven on a mule,” that’s a song. “Goin’ to New York on a bull,” that’s an idea.

Some accounts say this loony idea started as a bet. Beesley wrote that it was all a promotional stunt to advertise Ketchum.

The stunters, or betters, whichever you prefer, were Ted Terry, of Klamath Falls, Oregon; H.G. Wood, of Boise, and Vic Lusk of Butte, Montana. They aimed to ride a bull to Madison Square Garden for the 1939 World’s Fair. They would give theatrical and radio performances as the Sawtooth Range Riders along the way to pay expenses.

The expedition included Josephine, the pack mule, a horse named Silver Sally, and a dog named Skipper. The cowboys—bullboys?—would take turns riding the Durham-Herford bull they paid $50 for. They figured it would take 18 to 25 months to complete the trip.

The bull started with the name Ohadi, which clever readers will notice is Idaho spelled backward. Somewhere along the line, Ohadi became known as Hitler, after the German dictator who was about to plunge the world into war.

Ernie Pyle, who would soon become a famous correspondent in that war, wrote a column about the adventure. He wrote that the Sawtooth Range Riders wore “three ten-gallon hats, checkered shirts, flowing bow ties, overalls, bright gloves, and high-heeled cowboy boots. They look just the way New Yorkers think cowboys look.”

Pyle noted that Ohadi had to be broken to ride all over again every morning.

Three years and 3,000 miles later, Ted Terry and his menagerie (the others gave up on the stunt) rode into the World’s Fair in 1940. Sally, Skipper, and Ohadi/Hitler were all in good shape. No word about what happened to Josephine the Pack Mule. No word, either, about any huge increase in visitation to Ketchum, Idaho, due to the bull-riding stunt. Quite a few began visiting the newly built Sun Valley Resort, though. And that’s no bull.

Some accounts say this loony idea started as a bet. Beesley wrote that it was all a promotional stunt to advertise Ketchum.

The stunters, or betters, whichever you prefer, were Ted Terry, of Klamath Falls, Oregon; H.G. Wood, of Boise, and Vic Lusk of Butte, Montana. They aimed to ride a bull to Madison Square Garden for the 1939 World’s Fair. They would give theatrical and radio performances as the Sawtooth Range Riders along the way to pay expenses.

The expedition included Josephine, the pack mule, a horse named Silver Sally, and a dog named Skipper. The cowboys—bullboys?—would take turns riding the Durham-Herford bull they paid $50 for. They figured it would take 18 to 25 months to complete the trip.

The bull started with the name Ohadi, which clever readers will notice is Idaho spelled backward. Somewhere along the line, Ohadi became known as Hitler, after the German dictator who was about to plunge the world into war.

Ernie Pyle, who would soon become a famous correspondent in that war, wrote a column about the adventure. He wrote that the Sawtooth Range Riders wore “three ten-gallon hats, checkered shirts, flowing bow ties, overalls, bright gloves, and high-heeled cowboy boots. They look just the way New Yorkers think cowboys look.”

Pyle noted that Ohadi had to be broken to ride all over again every morning.

Three years and 3,000 miles later, Ted Terry and his menagerie (the others gave up on the stunt) rode into the World’s Fair in 1940. Sally, Skipper, and Ohadi/Hitler were all in good shape. No word about what happened to Josephine the Pack Mule. No word, either, about any huge increase in visitation to Ketchum, Idaho, due to the bull-riding stunt. Quite a few began visiting the newly built Sun Valley Resort, though. And that’s no bull.

Published on September 16, 2024 04:00

September 15, 2024

O No!

I’ve often written about Idaho’s license plates: here, here, here, here, here, and probably a few posts I didn’t find in a quick search.

So, maybe you think I know everything there is to know about the subject. Bad assumption about me no matter what the subject. But I do know a little. That’s why I was surprised to learn recently about an Idaho license plate fact that was staring me right in the face.

I have an electric car. The City of Boise offers electric vehicles a special parking option. You pay a fee once a year, then forget about feeding meters. I’ve been using it for a couple of years. So, I was surprised to get a parking ticket over near the statehouse.

I checked my parking permit receipt to make sure I hadn’t missed a deadline. Nope, I was good until mid-December. So, I took the ticket to city hall, which was just a couple of blocks away. The helpful clerk was puzzled by the way her system was acting. Yes, I had a permit and, yes, I’d received a ticket. Why hadn’t the meter patrol person noticed that when they typed in my license plate number? I have a personalized—some say “vanity”—plate with the letter and number combination 4IDAHO. At least, I thought I did. It turns out my plate is actually 4IDAH0.

Did you catch the difference there? It’s in that last digit. It is not an O but a zero. It’s not a mistake I made when ordering the plate. It’s not a mistake at all. Idaho uses only zeros when representing an O in a personalized plate. In fact, the only place you’ll actually find an O is in the county designators 1O and 2O. Why? Probably because someone decided it would be less confusing.

It confused the meter reader, though. When they typed in 4IDAHO no EV parking permit came up, so I got a ticket. I would have typed it in the same way. Helpfully, the City of Boise has merged 4IDAHO with 4IDAH0 in their system so that the issue won’t come up again.

I could probably zero in on some lame aphorism to close this post out, but I’ll resist. This isn’t a zero-sum game.

So, maybe you think I know everything there is to know about the subject. Bad assumption about me no matter what the subject. But I do know a little. That’s why I was surprised to learn recently about an Idaho license plate fact that was staring me right in the face.

I have an electric car. The City of Boise offers electric vehicles a special parking option. You pay a fee once a year, then forget about feeding meters. I’ve been using it for a couple of years. So, I was surprised to get a parking ticket over near the statehouse.

I checked my parking permit receipt to make sure I hadn’t missed a deadline. Nope, I was good until mid-December. So, I took the ticket to city hall, which was just a couple of blocks away. The helpful clerk was puzzled by the way her system was acting. Yes, I had a permit and, yes, I’d received a ticket. Why hadn’t the meter patrol person noticed that when they typed in my license plate number? I have a personalized—some say “vanity”—plate with the letter and number combination 4IDAHO. At least, I thought I did. It turns out my plate is actually 4IDAH0.

Did you catch the difference there? It’s in that last digit. It is not an O but a zero. It’s not a mistake I made when ordering the plate. It’s not a mistake at all. Idaho uses only zeros when representing an O in a personalized plate. In fact, the only place you’ll actually find an O is in the county designators 1O and 2O. Why? Probably because someone decided it would be less confusing.

It confused the meter reader, though. When they typed in 4IDAHO no EV parking permit came up, so I got a ticket. I would have typed it in the same way. Helpfully, the City of Boise has merged 4IDAHO with 4IDAH0 in their system so that the issue won’t come up again.

I could probably zero in on some lame aphorism to close this post out, but I’ll resist. This isn’t a zero-sum game.

Published on September 15, 2024 04:30

September 14, 2024

Look at those Idaho Democrats!

There are no Republicans in this picture showing the Idaho Congressional delegation meeting with President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Here's the caption from this Library of Congress photo: President John F. Kennedy meets with Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall and members of the Idaho Congressional delegation in the Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C. (L-R) President Kennedy; Representative Ralph R. Harding (standing); Secretary Udall; Representative Gracie Bowers Pfost; Senator Frank Church.

There are no Republicans in this picture showing the Idaho Congressional delegation meeting with President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Here's the caption from this Library of Congress photo: President John F. Kennedy meets with Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall and members of the Idaho Congressional delegation in the Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C. (L-R) President Kennedy; Representative Ralph R. Harding (standing); Secretary Udall; Representative Gracie Bowers Pfost; Senator Frank Church.I’m posting this because it’s a great picture and to show that Idaho’s delegation once consisted of nearly all Democrats. Yes, shocking, but true. Missing from the photo, but a member of the delegation at the time was Republican Senator Len B. Jordon. His photo is below.

Published on September 14, 2024 04:00

September 13, 2024

Idaho's Starting Point

Everything has to start somewhere. In surveying terms, Idaho starts 16 miles south of the city of Meridian at a place called Initial Point.

Lafayette Cartee was the first Surveyor General of Idaho Territory, and it was he who established that first point for his survey. The north/south survey line that runs through Initial Point is called the Boise Meridian. One might think that it was a trick of fate that the Boise Meridian is so close to the town of Meridian. If one were a fool. The term Boise Meridian was first, with the town named after it coming along in 1893.

So, if you find an old deed that includes a description with the words Boise Meridian, it doesn’t mean the property is in either Boise or Meridian, only that the description is in relation to that feature of the survey.

Lafayette Cartee was the first Surveyor General of Idaho Territory, and it was he who established that first point for his survey. The north/south survey line that runs through Initial Point is called the Boise Meridian. One might think that it was a trick of fate that the Boise Meridian is so close to the town of Meridian. If one were a fool. The term Boise Meridian was first, with the town named after it coming along in 1893.

So, if you find an old deed that includes a description with the words Boise Meridian, it doesn’t mean the property is in either Boise or Meridian, only that the description is in relation to that feature of the survey.

Published on September 13, 2024 04:00

September 12, 2024

Broadcasting Icon Georgia Davidson

As I wrote yesterday, KIDO radio celebrated its 100th year of broadcasting in July, 2022. Curtis Phillips, who was one of the original owners, became so associated with Idaho’s first radio station that everyone called him “Kiddo.” Important as he was to broadcasting history in Idaho, I’m going to focus on his partner and wife today. She became a broadcasting legend in her own right.

Georgia Marie Newport was born in Notus, Idaho in 1907. She met Curtis Phillips in Eugene when she was attending the University of Oregon. Phillips was running KORE in Eugene when she stepped in for a piano player performing on the radio with a quartet.

Shortly after they were married, Georgia and Curtis were visiting her parent’s home in Parma. They read that Boise High School student station KFAU was up for auction. They entered a bid and won.

Mr. and Mrs. Phillips made a go of it, moving the new station to ever-better headquarters, first to the top floor of the Boise Elks Lodge, then to the basement of the new Hotel Boise. Later KIDO moved to the mezzanine of the same hotel. The station was such a part of the community that hardly a day went by that it wasn’t mentioned in the newspaper.

C.G. “Kiddo” Phillips died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1942. He was 44. That left his wife, Georgia, to run the radio station and raise two kids. If there was ever any doubt that she was up to the task, she swept that away quickly.

Georgia Phillips became Georgia Davidson in 1946, when she married R. Mowbray Davidson, the owner of Peasley Transfer and Storage. In 1947, she out KIDO FM on the air, one of the state’s earliest FM radio stations. Then, in 1953 the radio pioneer brought television to Idaho. KIDO TV went on the air on July 12, 1953. Its call letters changed to KTVB in 1959 when Davidson sold KIDO radio.

For years Georgia Davidson was the only woman running one of the 120 NBC affiliates across the country. She served as president of the company until 1972 when she became chairman of the board.

Davidson cared about her viewers, not just the business side of television. In 1969, when Sesame Street came on the air, she was determined to include the program on KTVB’s schedule. Running a non-profit program on a commercial TV station didn’t set well with NBC or PBS, but Davidson made it happen. Later, she was instrumental in creating Idaho’s first public television station.

Georgia Davidson passed away in 1997 at age 89.

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation

Georgia Marie Newport was born in Notus, Idaho in 1907. She met Curtis Phillips in Eugene when she was attending the University of Oregon. Phillips was running KORE in Eugene when she stepped in for a piano player performing on the radio with a quartet.

Shortly after they were married, Georgia and Curtis were visiting her parent’s home in Parma. They read that Boise High School student station KFAU was up for auction. They entered a bid and won.

Mr. and Mrs. Phillips made a go of it, moving the new station to ever-better headquarters, first to the top floor of the Boise Elks Lodge, then to the basement of the new Hotel Boise. Later KIDO moved to the mezzanine of the same hotel. The station was such a part of the community that hardly a day went by that it wasn’t mentioned in the newspaper.

C.G. “Kiddo” Phillips died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1942. He was 44. That left his wife, Georgia, to run the radio station and raise two kids. If there was ever any doubt that she was up to the task, she swept that away quickly.

Georgia Phillips became Georgia Davidson in 1946, when she married R. Mowbray Davidson, the owner of Peasley Transfer and Storage. In 1947, she out KIDO FM on the air, one of the state’s earliest FM radio stations. Then, in 1953 the radio pioneer brought television to Idaho. KIDO TV went on the air on July 12, 1953. Its call letters changed to KTVB in 1959 when Davidson sold KIDO radio.

For years Georgia Davidson was the only woman running one of the 120 NBC affiliates across the country. She served as president of the company until 1972 when she became chairman of the board.

Davidson cared about her viewers, not just the business side of television. In 1969, when Sesame Street came on the air, she was determined to include the program on KTVB’s schedule. Running a non-profit program on a commercial TV station didn’t set well with NBC or PBS, but Davidson made it happen. Later, she was instrumental in creating Idaho’s first public television station.

Georgia Davidson passed away in 1997 at age 89.

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation

Published on September 12, 2024 04:00