Rick Just's Blog, page 12

September 11, 2024

More than a Century of Broadcasting

Idaho marked the 100th anniversary of broadcasting in July 2022, though there is some debate about whether the date to celebrate was July 18 or July 20. Stay tuned for the explanation.

The story of radio in Idaho began in September 1917 when Harry Redeker was hired as a chemistry and physics teacher at Boise High School. In the evenings, he taught Morse Code to young men who were about to head into the maw of World War I.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

Student radio station KFAU received its license on July 18, 1922—the date the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation marks as the official start of broadcasting inn the state—though the first official broadcast didn’t begin until July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support, the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU to become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station at that time, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the station’s fate, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September 1928, the school district sold KFAU to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kiddo.”

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School is long gone. Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc. for their help on this story.

Next time, how the untimely death of “Kiddo” Phillips turned his wife, Georgia, into a broadcasting legend.

KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.

KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.

Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc.

The story of radio in Idaho began in September 1917 when Harry Redeker was hired as a chemistry and physics teacher at Boise High School. In the evenings, he taught Morse Code to young men who were about to head into the maw of World War I.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

Student radio station KFAU received its license on July 18, 1922—the date the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation marks as the official start of broadcasting inn the state—though the first official broadcast didn’t begin until July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support, the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU to become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station at that time, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the station’s fate, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September 1928, the school district sold KFAU to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kiddo.”

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School is long gone. Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc. for their help on this story.

Next time, how the untimely death of “Kiddo” Phillips turned his wife, Georgia, into a broadcasting legend.

KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.

KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc.

Published on September 11, 2024 04:00

September 10, 2024

The Atlas of Drowned Towns

I’ve written about how the citizens of American Falls moved their town to keep it out of the rising waters of the American Falls Reservoir. That took place between 1925 and 1927. I didn’t know that there were two smaller towns inundated by the reservoir, Fort Hall Bottoms and Yuma.

I only know it now thanks to “The Atlas of Drowned Towns,” a project spearheaded by BSU professor of history Bob Reinhardt.

Hundreds of communities in the West were inundated when reservoirs backed up the waters of the rivers alongside which they were built. In Idaho, that included Center, and Van Wyck, both of which went under in 1957 with the construction of the Cascade Dam. Van Wyck had all but merged with the city of Cascade by that time, but much of it went underwater. The name is retained locally in the Van Wyck campground, a part of Lake Cascade State Park.

The C.J. Strike Reservoir, named for Clifford J. Strike, general manager of Idaho Power in the 30s and 40s, drowned the little town of Comet and a place sometimes called Garnet and sometimes called Halls Ferry. That was in 1952.

The town of pine went under in 1950 when Anderson Ranch Reservoir filled.

The most recent submerging of towns was in 1966. The Dworshak Dam took Dent and Big Island off the maps. Dent is now the name of a campground on the lake in Dworshak State Park.

All these drowned towns made way for hydroelectric and irrigation progress. They bring to mind at least two other towns that disappeared. Roosevelt was inundated because of an accidental dam. Most of the site of Morristown lies beneath Alexander Reservoir near Soda Springs, but the town ceased to exist years earlier.

Do you know of other drowned towns? Professor Reinhardt would like to know about them for the Atlas of Drowned Towns.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

I only know it now thanks to “The Atlas of Drowned Towns,” a project spearheaded by BSU professor of history Bob Reinhardt.

Hundreds of communities in the West were inundated when reservoirs backed up the waters of the rivers alongside which they were built. In Idaho, that included Center, and Van Wyck, both of which went under in 1957 with the construction of the Cascade Dam. Van Wyck had all but merged with the city of Cascade by that time, but much of it went underwater. The name is retained locally in the Van Wyck campground, a part of Lake Cascade State Park.

The C.J. Strike Reservoir, named for Clifford J. Strike, general manager of Idaho Power in the 30s and 40s, drowned the little town of Comet and a place sometimes called Garnet and sometimes called Halls Ferry. That was in 1952.

The town of pine went under in 1950 when Anderson Ranch Reservoir filled.

The most recent submerging of towns was in 1966. The Dworshak Dam took Dent and Big Island off the maps. Dent is now the name of a campground on the lake in Dworshak State Park.

All these drowned towns made way for hydroelectric and irrigation progress. They bring to mind at least two other towns that disappeared. Roosevelt was inundated because of an accidental dam. Most of the site of Morristown lies beneath Alexander Reservoir near Soda Springs, but the town ceased to exist years earlier.

Do you know of other drowned towns? Professor Reinhardt would like to know about them for the Atlas of Drowned Towns.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

Published on September 10, 2024 04:00

September 9, 2024

The Advenger

The War Department cooked up many creative ways to sell war bonds during WWII. In 1942 citizens of Ada County were given the chance to name a B-17 Flying Fortress, which would be the designated Ada County bomber.

The contest to name the bomber got good play in the Idaho Statesman. The rules were simple: The name had to be 24 characters or fewer and it had to be associated with Ada County.

More than 1,000 people entered the contest for a chance to win a $25 war bond. The proposed names ranged from the obvious to the ridiculous. Esto Perpetua was what Mrs. Merle Green of Caldwell proposed. Cruis-Ada (as in, crusader) was a cute play on words. Someone suggested Syringa, the state flower. Arrowrock Whizz Bang was one entry. Playing up the war bond theme Mrs. Lulu Johnson of Meridian entered the name Ada’s Victory Bondadier.

Several entries honored William E. Borah and C.G. “Kiddo” Phillips, the owner of KIDO radio who had recently passed away.

The winning name was Adavenger. Six people came up with that one, so someone drew the name out of a fishbowl at a war bond event at the Boise Victory Center. Maurine Busath was the first one picked, so she got the war bond.

A few weeks later the paper ran a picture of the B-17 with Adavenger painted just behind the machine gun turret in the nose. The Adavenger was one of 12,731 B-17 aircraft produced by Boeing in Seattle for the effort.

The War Department promised to send news to Ada County about the bomber’s activities “unless military censorship prevents.”

In September, the Statesman reported that the Flying Fortress was “off to bomb Berlin.” The airplane was never mentioned again in the pages of the newspaper.

A B-17 Flying Fortress like this one carried the name Adavenger when it was deployed to England for the war effort. A reporter in Seattle commenting on its defensive firepower when the model was introduced said, “It’s a flying fortress.” The name stuck. Photo by Airwolfhound - commons file, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

A B-17 Flying Fortress like this one carried the name Adavenger when it was deployed to England for the war effort. A reporter in Seattle commenting on its defensive firepower when the model was introduced said, “It’s a flying fortress.” The name stuck. Photo by Airwolfhound - commons file, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The contest to name the bomber got good play in the Idaho Statesman. The rules were simple: The name had to be 24 characters or fewer and it had to be associated with Ada County.

More than 1,000 people entered the contest for a chance to win a $25 war bond. The proposed names ranged from the obvious to the ridiculous. Esto Perpetua was what Mrs. Merle Green of Caldwell proposed. Cruis-Ada (as in, crusader) was a cute play on words. Someone suggested Syringa, the state flower. Arrowrock Whizz Bang was one entry. Playing up the war bond theme Mrs. Lulu Johnson of Meridian entered the name Ada’s Victory Bondadier.

Several entries honored William E. Borah and C.G. “Kiddo” Phillips, the owner of KIDO radio who had recently passed away.

The winning name was Adavenger. Six people came up with that one, so someone drew the name out of a fishbowl at a war bond event at the Boise Victory Center. Maurine Busath was the first one picked, so she got the war bond.

A few weeks later the paper ran a picture of the B-17 with Adavenger painted just behind the machine gun turret in the nose. The Adavenger was one of 12,731 B-17 aircraft produced by Boeing in Seattle for the effort.

The War Department promised to send news to Ada County about the bomber’s activities “unless military censorship prevents.”

In September, the Statesman reported that the Flying Fortress was “off to bomb Berlin.” The airplane was never mentioned again in the pages of the newspaper.

A B-17 Flying Fortress like this one carried the name Adavenger when it was deployed to England for the war effort. A reporter in Seattle commenting on its defensive firepower when the model was introduced said, “It’s a flying fortress.” The name stuck. Photo by Airwolfhound - commons file, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

A B-17 Flying Fortress like this one carried the name Adavenger when it was deployed to England for the war effort. A reporter in Seattle commenting on its defensive firepower when the model was introduced said, “It’s a flying fortress.” The name stuck. Photo by Airwolfhound - commons file, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Published on September 09, 2024 04:00

September 8, 2024

Idaho's Steamboat Springs

Reservoirs drown things. They put highways under hundreds of feet of water, as happened when Dworshak Dam was built. They drown falls as Cascade Dam did or change them so they are no longer recognizable, as happened with the American Falls Dam. And they sometimes eradicate natural features. This is why you may never have heard of Steamboat Springs.

The area around Soda Springs is well-known for its bubbling water. Ninety Percent Springs produced Idanha Water for many years and the mechanically timed geyser in the middle of town still brings in tourists. But we lost one once-famous feature, Steamboat Spring.

Oregon Trail travelers and early explorers frequently mentioned Steamboat Spring.

In 1839. Thomas Jefferson Farnham described it thus: “On approaching the spring, a deep gurgling, hissing sound is heard under-ground. It appears to be produced by the generating gas in a cavernous receiver. This, when the chamber is filled, bursts through another cavern filled with water, which it thrusts frothing and foaming into the spring. In passing the smaller orifice, the pent gas escapes with very much the same sound as steam makes in the escape-pipe of a steamboat. Hence the name.”

James John, wrote in his diary on August 10, 1841, that he had noticed 100 or so springs, "which are constantly bubbling and throwing off gas. Some sprout water to a considerable distance and roar like a steamboat."

John C. Fremont, writing in 1843 noticed an opening on the rock where “a white column of scattered water is thrown up, in form like a jet-d'eau, to a variable height of about three feet, and, though it is maintained in a constant supply, its greatest height is attained only at regular intervals, according to the action of the force below. It is accompanied by a subterranean noise, which, together with the motion of the water, makes very much the impression of a steamboat in motion; and, without knowing that it had been already previously so called, we gave to it the name of the Steamboat spring.”

Today, Steamboat Spring lies beneath about 40 feet of water in the Alexander Reservoir. On calm days you can see the surface bubbling a bit, marking the spot. In low-water years those who don’t mind tromping in the mud can still find the springs exposed.

This image of Steamboat Spring is from the book Caribou County Chronology, by Verna Irene Shupe, published in 1930.

This image of Steamboat Spring is from the book Caribou County Chronology, by Verna Irene Shupe, published in 1930.

The area around Soda Springs is well-known for its bubbling water. Ninety Percent Springs produced Idanha Water for many years and the mechanically timed geyser in the middle of town still brings in tourists. But we lost one once-famous feature, Steamboat Spring.

Oregon Trail travelers and early explorers frequently mentioned Steamboat Spring.

In 1839. Thomas Jefferson Farnham described it thus: “On approaching the spring, a deep gurgling, hissing sound is heard under-ground. It appears to be produced by the generating gas in a cavernous receiver. This, when the chamber is filled, bursts through another cavern filled with water, which it thrusts frothing and foaming into the spring. In passing the smaller orifice, the pent gas escapes with very much the same sound as steam makes in the escape-pipe of a steamboat. Hence the name.”

James John, wrote in his diary on August 10, 1841, that he had noticed 100 or so springs, "which are constantly bubbling and throwing off gas. Some sprout water to a considerable distance and roar like a steamboat."

John C. Fremont, writing in 1843 noticed an opening on the rock where “a white column of scattered water is thrown up, in form like a jet-d'eau, to a variable height of about three feet, and, though it is maintained in a constant supply, its greatest height is attained only at regular intervals, according to the action of the force below. It is accompanied by a subterranean noise, which, together with the motion of the water, makes very much the impression of a steamboat in motion; and, without knowing that it had been already previously so called, we gave to it the name of the Steamboat spring.”

Today, Steamboat Spring lies beneath about 40 feet of water in the Alexander Reservoir. On calm days you can see the surface bubbling a bit, marking the spot. In low-water years those who don’t mind tromping in the mud can still find the springs exposed.

This image of Steamboat Spring is from the book Caribou County Chronology, by Verna Irene Shupe, published in 1930.

This image of Steamboat Spring is from the book Caribou County Chronology, by Verna Irene Shupe, published in 1930.

Published on September 08, 2024 04:00

September 7, 2024

Ralph Dixey, a Remarkable Man

Little was expected of the Shoshone and Bannock people in the late 1800s. Their way of life, following fish, game, and plants with the seasons, ended when they were pushed onto the Fort Hall Reservation and told they were now farmers. Some were unable to cope with a life they didn't understand. They received little help from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The narrative of failure and talk of lazy, alcoholic Indians became the broad-stroke story for many settlers in the area. But what is often untold is the Shoshone-Bannock people's success despite the odds against them.

Some Tribal members embraced opportunity when they saw it. Ralph Dixey has fascinated me since I first learned about him.

Ralph Willet Dixey was born in Boise on July 4, 1874. Orphaned at age four, he went to Ross Fork to live with an uncle. In 1879, Ralph's uncle began farming on 160 acres near the Blackfoot River, where he put in a small dam to irrigate crops.

Ralph grew up learning about irrigation, farming, and ranching. In 1921, he and others on the reservation formed the Fort Hall Indian Stockman's Association. Some 150 Indian cattle and horse owners became members. Dixey served as its president for the first ten years of the organization.

The Association grew and cut most of its own hay, fenced grazing areas, developed watering systems, and purchased prime breeding stock. In short order, the stock they raised became well known for their quality. The Association commonly had about 6500 head of cattle and horses running on a range of nearly 70,000 acres.

Although the cattle buyers came from as far away as southern California, the Stockman's Association sold most of the beef locally, believing it would build goodwill with the white community.

Ralph Dixey was well known in Blackfoot for managing the Southeastern Idaho Round-Up and Livestock Show, which became a major part of the Eastern Idaho State Fair.

Dixey's leadership role on the reservation took him to Washington, DC more than once to testify before Congress on behalf of his people. The press sometimes mistakenly called him Chief Dixey.

This stockman of some note was known for his horses and his horsepower. Dixey was a car guy. In 1917, he became one of the first owners of a Willys-Knight Eight in Idaho. Then, in 1919, he surprised everyone, including his wife, when he bought her a Stutz Bearcat Roadster so she could drive into town whenever she pleased.

Ralph Dixey was a man who straddled two worlds. Proud of his native heritage, he made warbonnets for Hollywood movies and recorded war dance songs so they could be preserved. At the same time, he was a successful businessman. Dixey died at age 96 in 1959

Ralph Willet Dixey (1895-1959) wears traditional dress, in this "before civilization" image. An "after" image was also taken by Wrensted with him in Anglo dress and short hair. Orphaned at four, Dixey was raised at Fort Hall. A member of the Tribal Council, he traveled to Washington, DC, on several occasions to discuss Indian water rights. In 1911, he recorded war dance songs for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Ralph Willet Dixey (1895-1959) wears traditional dress, in this "before civilization" image. An "after" image was also taken by Wrensted with him in Anglo dress and short hair. Orphaned at four, Dixey was raised at Fort Hall. A member of the Tribal Council, he traveled to Washington, DC, on several occasions to discuss Indian water rights. In 1911, he recorded war dance songs for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.

A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.  Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

The narrative of failure and talk of lazy, alcoholic Indians became the broad-stroke story for many settlers in the area. But what is often untold is the Shoshone-Bannock people's success despite the odds against them.

Some Tribal members embraced opportunity when they saw it. Ralph Dixey has fascinated me since I first learned about him.

Ralph Willet Dixey was born in Boise on July 4, 1874. Orphaned at age four, he went to Ross Fork to live with an uncle. In 1879, Ralph's uncle began farming on 160 acres near the Blackfoot River, where he put in a small dam to irrigate crops.

Ralph grew up learning about irrigation, farming, and ranching. In 1921, he and others on the reservation formed the Fort Hall Indian Stockman's Association. Some 150 Indian cattle and horse owners became members. Dixey served as its president for the first ten years of the organization.

The Association grew and cut most of its own hay, fenced grazing areas, developed watering systems, and purchased prime breeding stock. In short order, the stock they raised became well known for their quality. The Association commonly had about 6500 head of cattle and horses running on a range of nearly 70,000 acres.

Although the cattle buyers came from as far away as southern California, the Stockman's Association sold most of the beef locally, believing it would build goodwill with the white community.

Ralph Dixey was well known in Blackfoot for managing the Southeastern Idaho Round-Up and Livestock Show, which became a major part of the Eastern Idaho State Fair.

Dixey's leadership role on the reservation took him to Washington, DC more than once to testify before Congress on behalf of his people. The press sometimes mistakenly called him Chief Dixey.

This stockman of some note was known for his horses and his horsepower. Dixey was a car guy. In 1917, he became one of the first owners of a Willys-Knight Eight in Idaho. Then, in 1919, he surprised everyone, including his wife, when he bought her a Stutz Bearcat Roadster so she could drive into town whenever she pleased.

Ralph Dixey was a man who straddled two worlds. Proud of his native heritage, he made warbonnets for Hollywood movies and recorded war dance songs so they could be preserved. At the same time, he was a successful businessman. Dixey died at age 96 in 1959

Ralph Willet Dixey (1895-1959) wears traditional dress, in this "before civilization" image. An "after" image was also taken by Wrensted with him in Anglo dress and short hair. Orphaned at four, Dixey was raised at Fort Hall. A member of the Tribal Council, he traveled to Washington, DC, on several occasions to discuss Indian water rights. In 1911, he recorded war dance songs for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Ralph Willet Dixey (1895-1959) wears traditional dress, in this "before civilization" image. An "after" image was also taken by Wrensted with him in Anglo dress and short hair. Orphaned at four, Dixey was raised at Fort Hall. A member of the Tribal Council, he traveled to Washington, DC, on several occasions to discuss Indian water rights. In 1911, he recorded war dance songs for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.

A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.  Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

Published on September 07, 2024 04:00

September 6, 2024

The Columbia Liberty Bell

Miss Hattie Felix Harris of Boise oversaw Idaho’s participation in a nationwide project that garnered the support of tens of thousands of people. The Columbia Liberty Bell was one of countless efforts to get on the bandwagon for the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago.

I’ve written previously about all the effort that went into constructing and furnishing the Idaho Building for the Exposition and Boise’s venerable Columbian Club, which is the last such club still active in the United States.

The Columbia Liberty Bell was the brainchild of William Dowell of New Jersey. He sought thousands of contributions to the project. Money was necessary, of course, but he envisioned a bell that included relics from history melted down to help form the bell. According to the website Chicagology, the bell included “ The keys of Jefferson Davis’ house, pike heads used by John Brown at Harper’s Ferry, John C, Calhoun’s silver spoon and Lucretia Mott’s silver fruit knife, Simon Bolivar’s watch chain, hinges from the door of Abraham Lincoln’s house at Springfield, George Washington’s surveying chain, Thomas Jefferson’s copper kettle, Mrs. Parnell’s earrings, and Whittier’s pen.”

Hattie Felix Harris stirred up interest in Idaho donations, which included “Bullion, gold and silver, besides some very rare relics.” In the May 13, 1893 article summing up the Idaho drive, the only item specifically noted was “a beautiful specimen of silver bullion taken from the DeLamar Mine” in Owyhee County.

Harris supplied the newspaper with a list of the monetary donations for counties around the state, totaling $110.

The Columbian Liberty Bell was cast on the evening of June 22, 1893, with at least 1,000 people looking on at the Meneely Bell Foundry in Troy, New York. That conglomeration of items and materials included in the pour did not affect it, according to Mr. Maneely, in a New York Times article the following day. “Mr. Maneely says… the great bulk of the material is copper and tin, and the gold and silver form only a small portion of the whole mass.”

And, what a mass it was. The bell weighed 13,000 pounds and stood seven feet high.

The Columbian Liberty Bell arrived late for its date in Chicago. It rang several times during the Exposition for various events. Crowd interest was not what promoters had hoped. There was so much else to see.

After the Exposition closed, the bell went on a world tour. And that was the end of it. How one loses track of a 13,000-pound bell is puzzling. The best guess anyone has is that it was melted down during the Bolshevik revolution.

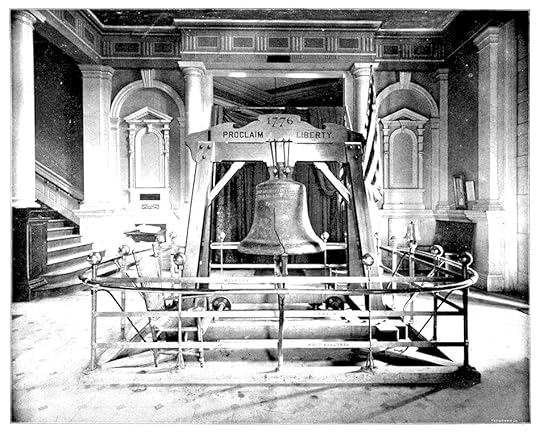

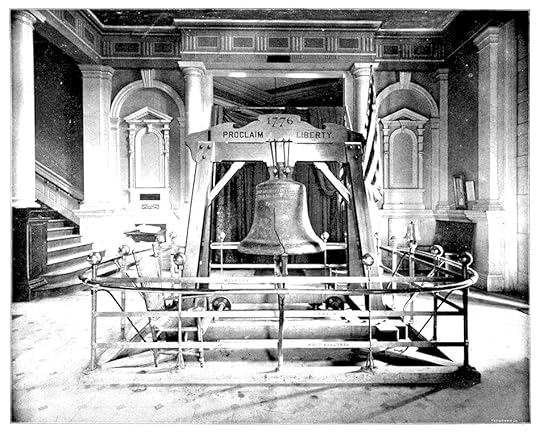

The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

I’ve written previously about all the effort that went into constructing and furnishing the Idaho Building for the Exposition and Boise’s venerable Columbian Club, which is the last such club still active in the United States.

The Columbia Liberty Bell was the brainchild of William Dowell of New Jersey. He sought thousands of contributions to the project. Money was necessary, of course, but he envisioned a bell that included relics from history melted down to help form the bell. According to the website Chicagology, the bell included “ The keys of Jefferson Davis’ house, pike heads used by John Brown at Harper’s Ferry, John C, Calhoun’s silver spoon and Lucretia Mott’s silver fruit knife, Simon Bolivar’s watch chain, hinges from the door of Abraham Lincoln’s house at Springfield, George Washington’s surveying chain, Thomas Jefferson’s copper kettle, Mrs. Parnell’s earrings, and Whittier’s pen.”

Hattie Felix Harris stirred up interest in Idaho donations, which included “Bullion, gold and silver, besides some very rare relics.” In the May 13, 1893 article summing up the Idaho drive, the only item specifically noted was “a beautiful specimen of silver bullion taken from the DeLamar Mine” in Owyhee County.

Harris supplied the newspaper with a list of the monetary donations for counties around the state, totaling $110.

The Columbian Liberty Bell was cast on the evening of June 22, 1893, with at least 1,000 people looking on at the Meneely Bell Foundry in Troy, New York. That conglomeration of items and materials included in the pour did not affect it, according to Mr. Maneely, in a New York Times article the following day. “Mr. Maneely says… the great bulk of the material is copper and tin, and the gold and silver form only a small portion of the whole mass.”

And, what a mass it was. The bell weighed 13,000 pounds and stood seven feet high.

The Columbian Liberty Bell arrived late for its date in Chicago. It rang several times during the Exposition for various events. Crowd interest was not what promoters had hoped. There was so much else to see.

After the Exposition closed, the bell went on a world tour. And that was the end of it. How one loses track of a 13,000-pound bell is puzzling. The best guess anyone has is that it was melted down during the Bolshevik revolution.

The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

Published on September 06, 2024 04:00

September 5, 2024

131 Years of the Columbian Club

Boise’s Columbian Club started just as the hundreds of other Columbian clubs across the country did. The women’s clubs were formed to help ensure that every state was well represented at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, the World’s Fair in Chicago. Every county in Idaho formed a Columbian Club. The Boise Columbian Club would have a distinction that no other Columbian club in the country would have. It is the last Columbian Club, and remains active today.

The Columbian Exposition, often referred to as the “White City” because of its prevalent use of white plaster inspired by classical building designs, commemorated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World, albeit a year after the actual anniversary.

Idaho was a newly minted state eager to show off its resources. Neoclassical architecture would not do. The concept for the Idaho Building was envisioned by Spokane architect Kirtland Cutter, who was chosen by a committee that included famed author and Boise resident Mary Hallock Foote. Foote had attended the Women’s School of Design at the Cooper Union in New York. Best known for her illustrations in popular magazines and books, Foote was also trained to draft. Foote led a committee in the Columbian Club that directed the design of the building and its furnishings. The Women’s Reception Room in the Idaho Pavilion with its early arts and crafts furniture was of special importance.

Befitting this frontier state, the Idaho Building was a rustic log chalet on a foundation of lava rock. The cedar logs and cedar shake roof were stained to give the impression that the three-story building was years older than it was. It was a showcase of Idaho resources. The four ground floor rooms were the Fir, Cedar, Tamarack and Pine rooms, each trimmed in the namesake wood. Gemstones from the Gem State encrusted the white Idaho marble fireplace, which featured andirons made from miner’s picks, shovels and hammers. The second floor, where the Women’s and Men’s reception rooms were located, was divided by a mica hall, featuring Idaho mica glazing. That floor extended into a balcony garden planted with Idaho wildflowers. A taxidermy and agricultural product display took up the third floor.

The state’s building was a popular attraction, with an estimated 18 million people taking it in. One postcard remarked it was the “gem of the show.”

The furniture from the women’s reception room would return to Boise after the conclusion of the exposition. The women of the Columbian Club, who gathered the first collection of books to benefit women traveling on the Oregon Trail, were working on Boise’s first public library. In 1895, they furnished that room in the basement of city hall with custom furniture from the Idaho Building. But that wasn’t the end of the club. They had a library to build, then ordinances to pass (no spitting on the sidewalks), the courthouse grounds to landscape, suffrage to right, a traveling library to establish, a curfew law to pass, money for a girls’ dormitory at the University of Idaho to raise, improvements to the Morris Hill Cemetery to make, more furniture for yet another Idaho Building for the Lewis and Clark Exposition to procure, a library bond election to pass, sewing classes to be introduced into public schools, and on, and on, into the next century, and then the next.

In recent years, the Columbian Club led the restoration effort for the O’Farrell Cabin, and funded 20 log benches along the Greenbelt. The club’s endowment provides annual scholarships to outstanding young students.

The club’s origin story is tied to that 1893 Chicago exposition, where the first moving sidewalk, first Ferris Wheel, first automatic dishwasher, first phosphorescent lights, first zipper, first spray painting, and first U.S. commemorative stamps and coins were featured. It was at the Columbian Exposition that products common today were first introduced, including Aunt Jemima pancake mix, Cracker Jack, Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit Gum, Quaker Oats, Cream of Wheat, Shredded Wheat, Hershey’s Chocolate, Pabst Blue Ribbon (which didn’t actually win one at the fair but was chosen there as “America’s Best”).

All those firsts and one important last: The last, and ever vibrant, Columbian Club.

In June 1899, the Educational Committee of the Boise Columbian Club attended a reception at the capitol celebrating the opening of their traveling library, one of many projects the club sponsored over the years. The image is from the Columbian Club Collection, MS356, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society. A member of the Boise Columbian Club provided the names of the women in the photo from left: Margaret Roberts, Stella Balderson, Gertrude Hays, Mary Beatty, Eva Dockery, and Harriet French Steen.

In June 1899, the Educational Committee of the Boise Columbian Club attended a reception at the capitol celebrating the opening of their traveling library, one of many projects the club sponsored over the years. The image is from the Columbian Club Collection, MS356, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society. A member of the Boise Columbian Club provided the names of the women in the photo from left: Margaret Roberts, Stella Balderson, Gertrude Hays, Mary Beatty, Eva Dockery, and Harriet French Steen.

The Columbian Exposition, often referred to as the “White City” because of its prevalent use of white plaster inspired by classical building designs, commemorated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World, albeit a year after the actual anniversary.

Idaho was a newly minted state eager to show off its resources. Neoclassical architecture would not do. The concept for the Idaho Building was envisioned by Spokane architect Kirtland Cutter, who was chosen by a committee that included famed author and Boise resident Mary Hallock Foote. Foote had attended the Women’s School of Design at the Cooper Union in New York. Best known for her illustrations in popular magazines and books, Foote was also trained to draft. Foote led a committee in the Columbian Club that directed the design of the building and its furnishings. The Women’s Reception Room in the Idaho Pavilion with its early arts and crafts furniture was of special importance.

Befitting this frontier state, the Idaho Building was a rustic log chalet on a foundation of lava rock. The cedar logs and cedar shake roof were stained to give the impression that the three-story building was years older than it was. It was a showcase of Idaho resources. The four ground floor rooms were the Fir, Cedar, Tamarack and Pine rooms, each trimmed in the namesake wood. Gemstones from the Gem State encrusted the white Idaho marble fireplace, which featured andirons made from miner’s picks, shovels and hammers. The second floor, where the Women’s and Men’s reception rooms were located, was divided by a mica hall, featuring Idaho mica glazing. That floor extended into a balcony garden planted with Idaho wildflowers. A taxidermy and agricultural product display took up the third floor.

The state’s building was a popular attraction, with an estimated 18 million people taking it in. One postcard remarked it was the “gem of the show.”

The furniture from the women’s reception room would return to Boise after the conclusion of the exposition. The women of the Columbian Club, who gathered the first collection of books to benefit women traveling on the Oregon Trail, were working on Boise’s first public library. In 1895, they furnished that room in the basement of city hall with custom furniture from the Idaho Building. But that wasn’t the end of the club. They had a library to build, then ordinances to pass (no spitting on the sidewalks), the courthouse grounds to landscape, suffrage to right, a traveling library to establish, a curfew law to pass, money for a girls’ dormitory at the University of Idaho to raise, improvements to the Morris Hill Cemetery to make, more furniture for yet another Idaho Building for the Lewis and Clark Exposition to procure, a library bond election to pass, sewing classes to be introduced into public schools, and on, and on, into the next century, and then the next.

In recent years, the Columbian Club led the restoration effort for the O’Farrell Cabin, and funded 20 log benches along the Greenbelt. The club’s endowment provides annual scholarships to outstanding young students.

The club’s origin story is tied to that 1893 Chicago exposition, where the first moving sidewalk, first Ferris Wheel, first automatic dishwasher, first phosphorescent lights, first zipper, first spray painting, and first U.S. commemorative stamps and coins were featured. It was at the Columbian Exposition that products common today were first introduced, including Aunt Jemima pancake mix, Cracker Jack, Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit Gum, Quaker Oats, Cream of Wheat, Shredded Wheat, Hershey’s Chocolate, Pabst Blue Ribbon (which didn’t actually win one at the fair but was chosen there as “America’s Best”).

All those firsts and one important last: The last, and ever vibrant, Columbian Club.

In June 1899, the Educational Committee of the Boise Columbian Club attended a reception at the capitol celebrating the opening of their traveling library, one of many projects the club sponsored over the years. The image is from the Columbian Club Collection, MS356, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society. A member of the Boise Columbian Club provided the names of the women in the photo from left: Margaret Roberts, Stella Balderson, Gertrude Hays, Mary Beatty, Eva Dockery, and Harriet French Steen.

In June 1899, the Educational Committee of the Boise Columbian Club attended a reception at the capitol celebrating the opening of their traveling library, one of many projects the club sponsored over the years. The image is from the Columbian Club Collection, MS356, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society. A member of the Boise Columbian Club provided the names of the women in the photo from left: Margaret Roberts, Stella Balderson, Gertrude Hays, Mary Beatty, Eva Dockery, and Harriet French Steen.

Published on September 05, 2024 04:00

September 4, 2024

Frozen Dog Road

Frozen Dog Road in Gem County does not lead directly to Lake Wobegon, Minnesota. Or does it? Lake Wobegon is the fictional town where Garrison Keillor told us all the children are above average. His weekly News from Lake Wobegon segment on the program Prairie Home Companion introduced us to the antics of many imaginary Minnesotans. Frozen Dog, Idaho had him beat by about 80 years.

A reader asked me where the name Frozen Dog Road came from. I’m not sure which came first, the road or Frozen Dog Ranch, but the ranch was the source of a lot of interesting stories. Frozen Dog Ranch was named after Frozen Dog, Idaho, which doesn't exist.

Colonel William C. Hunter invented Frozen Dog, Idaho, as the setting for a series of stories he told about its residents, Grizzly Pete, Jim the Stage-Driver, Mormon Ed, Half-Hung Simon, and others.

Commissioned a colonel and given a job by Governor Frank W. Hunt, Hunter also served Idaho governors, John A. Morrison and Frank R. Gooding. How he served them and why he deserved the appellation "colonel" is a little unclear. He seemed to be an Idaho booster, even though he lived mainly in Chicago, serving on the Idaho delegation to this and that conference.

His real job was that of a writer and publisher. He wrote about how to succeed in business and self-help books. His columns appeared in a scattering of papers across the country. PEP, billed as "A book of how's not why's for physical and mental efficiency," was published in 1914 and went through several editions. PEP was an acronym for Poise, Efficiency, Peace.

In 1905 Hunter gathered some of his humorous columns and many pages of doggerel into a book called Frozen Dog Tales and Other Things. The tales took place in Frozen Dog, Idaho, which, he claimed, had taken a different name when the town got a post office. However, he would not tell readers the "real" name. Frozen Dog, despite the ranch and road's location in Gem County, was said to be in Idaho County along the Clearwater River. He wrote:

"The town is full of life. There are few laws to govern. Horse thieves are promptly lynched, and the Golden Rule is the unwritten law of the country. No stranger is asked where he came from; no one is asked his back history. Everyone tends to his own business. Men are judged by their individual worth, and a man's word is as good as his bond, and the man who doesn't 'make good' is run out of the country."

Several stories involved quirks in what little law there was. For instance, a local man drowned while crossing a swollen stream. He was swept off his mule, which survived. When authorities found the body, they also found a six-shooter in one of his pockets. Concealing a weapon was a violation of the law. Hence, the sheriff, who was also the coroner, fined the corpse $50 and confiscated the mule and gun in payment.

The newspaper in Frozen Dog was called the "Howling Wolf." It ran frequent aphorisms such as "There are two times in a man's life when he discovers he cannot understand a woman: the first is before he is married, and the second is after he is married." That passed for humor in 1905.

One more example from the book will give you the gist: "The Horse Show at Frozen Dog, Idaho, was a great success. Grizzly Pete's mustang got first prize in the cayuse class, and Joe Kip got first prize in the driving class. He owned the only horse in Idaho County that could be hitched to a rig. The gate receipts of $12 for the week were divided equally between the two prominent citizens above referred to. Grizzly Pete was judge for the cayuse class and Joe Kip for the driving class."

Most of Col. William Crosbie Hunter's books are still available in online archives and as cheap reprints. Frozen Dog and Other Things was lavishly illustrated for its time, featuring woodcut graphics on every page.

On March 18, 1917, Hunter died in Emmett at age 50, leaving behind a legacy of books and a road called Frozen Dog.

The first page of Frozen Dog and Other Things, with a photo of Col. William C. Hunter inset. Every page of the book features a woodcut illustration along with the stories, poems, and songs.

The first page of Frozen Dog and Other Things, with a photo of Col. William C. Hunter inset. Every page of the book features a woodcut illustration along with the stories, poems, and songs.

A reader asked me where the name Frozen Dog Road came from. I’m not sure which came first, the road or Frozen Dog Ranch, but the ranch was the source of a lot of interesting stories. Frozen Dog Ranch was named after Frozen Dog, Idaho, which doesn't exist.

Colonel William C. Hunter invented Frozen Dog, Idaho, as the setting for a series of stories he told about its residents, Grizzly Pete, Jim the Stage-Driver, Mormon Ed, Half-Hung Simon, and others.

Commissioned a colonel and given a job by Governor Frank W. Hunt, Hunter also served Idaho governors, John A. Morrison and Frank R. Gooding. How he served them and why he deserved the appellation "colonel" is a little unclear. He seemed to be an Idaho booster, even though he lived mainly in Chicago, serving on the Idaho delegation to this and that conference.

His real job was that of a writer and publisher. He wrote about how to succeed in business and self-help books. His columns appeared in a scattering of papers across the country. PEP, billed as "A book of how's not why's for physical and mental efficiency," was published in 1914 and went through several editions. PEP was an acronym for Poise, Efficiency, Peace.

In 1905 Hunter gathered some of his humorous columns and many pages of doggerel into a book called Frozen Dog Tales and Other Things. The tales took place in Frozen Dog, Idaho, which, he claimed, had taken a different name when the town got a post office. However, he would not tell readers the "real" name. Frozen Dog, despite the ranch and road's location in Gem County, was said to be in Idaho County along the Clearwater River. He wrote:

"The town is full of life. There are few laws to govern. Horse thieves are promptly lynched, and the Golden Rule is the unwritten law of the country. No stranger is asked where he came from; no one is asked his back history. Everyone tends to his own business. Men are judged by their individual worth, and a man's word is as good as his bond, and the man who doesn't 'make good' is run out of the country."

Several stories involved quirks in what little law there was. For instance, a local man drowned while crossing a swollen stream. He was swept off his mule, which survived. When authorities found the body, they also found a six-shooter in one of his pockets. Concealing a weapon was a violation of the law. Hence, the sheriff, who was also the coroner, fined the corpse $50 and confiscated the mule and gun in payment.

The newspaper in Frozen Dog was called the "Howling Wolf." It ran frequent aphorisms such as "There are two times in a man's life when he discovers he cannot understand a woman: the first is before he is married, and the second is after he is married." That passed for humor in 1905.

One more example from the book will give you the gist: "The Horse Show at Frozen Dog, Idaho, was a great success. Grizzly Pete's mustang got first prize in the cayuse class, and Joe Kip got first prize in the driving class. He owned the only horse in Idaho County that could be hitched to a rig. The gate receipts of $12 for the week were divided equally between the two prominent citizens above referred to. Grizzly Pete was judge for the cayuse class and Joe Kip for the driving class."

Most of Col. William Crosbie Hunter's books are still available in online archives and as cheap reprints. Frozen Dog and Other Things was lavishly illustrated for its time, featuring woodcut graphics on every page.

On March 18, 1917, Hunter died in Emmett at age 50, leaving behind a legacy of books and a road called Frozen Dog.

The first page of Frozen Dog and Other Things, with a photo of Col. William C. Hunter inset. Every page of the book features a woodcut illustration along with the stories, poems, and songs.

The first page of Frozen Dog and Other Things, with a photo of Col. William C. Hunter inset. Every page of the book features a woodcut illustration along with the stories, poems, and songs.

Published on September 04, 2024 04:00

September 3, 2024

Chatting with Nixon

Here’s a little trivia question for you: Who was the first person to interview Richard Nixon live following his resignation?

Walter Cronkite would be a good guess. Paul J. Schneider would be a better one.

Schneider was a Boise Broadcasting icon for some 50 years. He was on TV now and then but is best remembered as the voice of BSU Bronco football for 35 years. He and Lon Dunn also did a legendary two-man morning show on KBOI. He was such a part of that station that they named the building after him when he retired.

But Richard Nixon?

Speaking at an Idaho Broadcast History group gathering Schneider told how that came about. He said that he had been interviewing his friend, baseball Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew. Killebrew asked Schneider afterward if he wanted to go somewhere else in his career. Paul J. said that he was quite happy right where he was. Killebrew pressed him, asking if there was one thing he’d like to do in radio. Schneider answered that he’d like to interview former President Richard Nixon. Killebrew said, “I can make that happen.”

Schneider was skeptical, but a few days later, Killebrew called and said he’d set it up. Schneider was to call Nixon on his birthday for the live interview. One condition: No questions about politics.

“So, we had him predict the Super Bowl,” Schneider said.

Newspeople worldwide were eager to get a Nixon interview. Apparently, none of them knew Harmon Killebrew.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Walter Cronkite would be a good guess. Paul J. Schneider would be a better one.

Schneider was a Boise Broadcasting icon for some 50 years. He was on TV now and then but is best remembered as the voice of BSU Bronco football for 35 years. He and Lon Dunn also did a legendary two-man morning show on KBOI. He was such a part of that station that they named the building after him when he retired.

But Richard Nixon?

Speaking at an Idaho Broadcast History group gathering Schneider told how that came about. He said that he had been interviewing his friend, baseball Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew. Killebrew asked Schneider afterward if he wanted to go somewhere else in his career. Paul J. said that he was quite happy right where he was. Killebrew pressed him, asking if there was one thing he’d like to do in radio. Schneider answered that he’d like to interview former President Richard Nixon. Killebrew said, “I can make that happen.”

Schneider was skeptical, but a few days later, Killebrew called and said he’d set it up. Schneider was to call Nixon on his birthday for the live interview. One condition: No questions about politics.

“So, we had him predict the Super Bowl,” Schneider said.

Newspeople worldwide were eager to get a Nixon interview. Apparently, none of them knew Harmon Killebrew.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Published on September 03, 2024 04:00

September 2, 2024

Corporal Punishment, 1890

Corporal punishment is defined as “physical punishment, such as caning or flogging.” Often the discussion about corporal punishment centers on whether it should be allowed in schools. Paddles and strops commonly hung on nails in schoolrooms across Idaho.

In 1890, the Idaho Statesman editorialized on the subject, saying “…we are prepared now and always shall be to oppose corporal punishment in the public schools. Boys’ bodies were not fashioned in their God-like form to be whipped. There are other ways to reach the hearts and minds of American boys to compel obedience.”

A stacked headline in the same paper six years later read:

REBELLION IN SCHOOL

Professor Wood Has Trouble

With High School Boys

SCENE OF GREAT EXCITEMENT

The Pedagogue Downs Rus Bryon and

Precipitates a Riot—Girls

Stampeded

It seems that the professor Wood, who was known to inflict frequent physical punishments in his classes at Central School, demanded to see a note one of his students tried to pass in class. The student, Rus Bryon, refused to give it to him. Wood made a grab for the note and Bryon bolted down the aisle. They struggled over the note, with Wood finally throwing the youngster to the floor, putting his knee in the lad’s stomach, and reportedly choking him. When the student got up, he again refused to relinquish the note, instead tearing it up.

Meanwhile, fellow students surrounded the teacher and encouraged him to cease manhandling Bryon. At that he released the boy.

The kerfuffle resulted in several upset girls leaving school early that day.

Trustees investigated the incident. They found Bryon insubordinate, but also judged the professor’s “method of disciplining unruly scholars was harsh, undignified and unnecessary.” They passed a resolution prohibiting such punishment.

One objection to paddling was that its severity was dependent on the strength of the paddler and, perhaps, their anger. In 1899, there was news of an invention that would solve those problems, though it was probably meant for lawbreakers, not students. One Newton Harrison had created a mechanical appliance that could administer corporal punishment at the touch of a button. His “electric whipping post” was presented as a vast improvement. You be the judge from the description of the device.

“The victim is first lashed securely to the post with his arms above his head. The whipper is a large wheel which turns freely on an upright. The whip or thong is attached to the rim of the wheel and as the wheel revolves it is swung violently around. The wheel is lowered or raised to bring it on a level with the victim’s back. The wheel is revolved by a small motor at the base of the upright, connected with the axle by a rear wheel.”

Bonus: The administrator of punishment need not even be in the same room as the person being punished. He could press a button somewhere out of sight and sound while he administered “mathematically correct justice.” That the person receiving the punishment was referred to even in the glowing article as “the victim” seems telling.

By 1900, Dr. Black, president of the Albion State Normal School, where many of the Idaho’s teachers learned their profession, was speaking out against corporal punishment in schools as a crime.

Over the next several decades debate about the subject of corporal punishment in public schools flared up from time-to-time in Idaho and the United States. In 1977, the matter came before the U.S. Supreme Court in Ingraham v. Wright. The argument against the practice was that it was against the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause of the Eighth Amendment.

The Supreme Court ruled that corporal punishment is constitutional, leaving it to states to decide whether to allow it. Idaho is one of 19 states that still allows corporal punishment. Four of those states (not Idaho) ban it for students with disabilities.

In 1890, the Idaho Statesman editorialized on the subject, saying “…we are prepared now and always shall be to oppose corporal punishment in the public schools. Boys’ bodies were not fashioned in their God-like form to be whipped. There are other ways to reach the hearts and minds of American boys to compel obedience.”

A stacked headline in the same paper six years later read:

REBELLION IN SCHOOL

Professor Wood Has Trouble

With High School Boys

SCENE OF GREAT EXCITEMENT

The Pedagogue Downs Rus Bryon and

Precipitates a Riot—Girls

Stampeded

It seems that the professor Wood, who was known to inflict frequent physical punishments in his classes at Central School, demanded to see a note one of his students tried to pass in class. The student, Rus Bryon, refused to give it to him. Wood made a grab for the note and Bryon bolted down the aisle. They struggled over the note, with Wood finally throwing the youngster to the floor, putting his knee in the lad’s stomach, and reportedly choking him. When the student got up, he again refused to relinquish the note, instead tearing it up.

Meanwhile, fellow students surrounded the teacher and encouraged him to cease manhandling Bryon. At that he released the boy.

The kerfuffle resulted in several upset girls leaving school early that day.

Trustees investigated the incident. They found Bryon insubordinate, but also judged the professor’s “method of disciplining unruly scholars was harsh, undignified and unnecessary.” They passed a resolution prohibiting such punishment.

One objection to paddling was that its severity was dependent on the strength of the paddler and, perhaps, their anger. In 1899, there was news of an invention that would solve those problems, though it was probably meant for lawbreakers, not students. One Newton Harrison had created a mechanical appliance that could administer corporal punishment at the touch of a button. His “electric whipping post” was presented as a vast improvement. You be the judge from the description of the device.

“The victim is first lashed securely to the post with his arms above his head. The whipper is a large wheel which turns freely on an upright. The whip or thong is attached to the rim of the wheel and as the wheel revolves it is swung violently around. The wheel is lowered or raised to bring it on a level with the victim’s back. The wheel is revolved by a small motor at the base of the upright, connected with the axle by a rear wheel.”

Bonus: The administrator of punishment need not even be in the same room as the person being punished. He could press a button somewhere out of sight and sound while he administered “mathematically correct justice.” That the person receiving the punishment was referred to even in the glowing article as “the victim” seems telling.

By 1900, Dr. Black, president of the Albion State Normal School, where many of the Idaho’s teachers learned their profession, was speaking out against corporal punishment in schools as a crime.

Over the next several decades debate about the subject of corporal punishment in public schools flared up from time-to-time in Idaho and the United States. In 1977, the matter came before the U.S. Supreme Court in Ingraham v. Wright. The argument against the practice was that it was against the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause of the Eighth Amendment.

The Supreme Court ruled that corporal punishment is constitutional, leaving it to states to decide whether to allow it. Idaho is one of 19 states that still allows corporal punishment. Four of those states (not Idaho) ban it for students with disabilities.

Published on September 02, 2024 04:00