Rick Just's Blog, page 16

August 1, 2024

Jesse Owens in Boise

Jesse Owens was one the biggest Olympic heroes of all time. When he took four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics in Germany, it put the lie to Hitler’s claims of Aryan superiority.

After his Olympic success, Owens often struggled to make a living. For a time, he put on exhibitions, traveling around the country to race local runners in the 100-yard dash, giving them a 20-yard head start. He also raced against horses, preferring thoroughbreds that tended to startle when the starting gun was fired, which gave him an edge.

Owens took a little swing through Idaho in 1945, appearing in Idaho Falls, Payette, and Boise. In Payette, he beat Payette Lady, a thoroughbred owned by Ike Whiteley. No time for his run was recorded.

In Boise, the holder of seven world records ran for a crowd of 3500 at Airway Park. His appearance in the Capitol City wasn’t against horses, but select members of the Globetrotters and Bearded Davidites, exhibition baseball teams. The Statesman reported that “Owens won as he pleased, crossing the line first in the century after giving his opponents a 10-yard lead; then running the low hurdles while two players ran on the flat and finally circling the bases against four opponents, each running only one base.”

The crowd applauded, glad to welcome Owens to Boise. But the welcome was not universal. No Boise hotel would rent a room to the Black man. He stayed with Warner and Clara Terrell in their house on 15th Street instead.

After his Olympic success, Owens often struggled to make a living. For a time, he put on exhibitions, traveling around the country to race local runners in the 100-yard dash, giving them a 20-yard head start. He also raced against horses, preferring thoroughbreds that tended to startle when the starting gun was fired, which gave him an edge.

Owens took a little swing through Idaho in 1945, appearing in Idaho Falls, Payette, and Boise. In Payette, he beat Payette Lady, a thoroughbred owned by Ike Whiteley. No time for his run was recorded.

In Boise, the holder of seven world records ran for a crowd of 3500 at Airway Park. His appearance in the Capitol City wasn’t against horses, but select members of the Globetrotters and Bearded Davidites, exhibition baseball teams. The Statesman reported that “Owens won as he pleased, crossing the line first in the century after giving his opponents a 10-yard lead; then running the low hurdles while two players ran on the flat and finally circling the bases against four opponents, each running only one base.”

The crowd applauded, glad to welcome Owens to Boise. But the welcome was not universal. No Boise hotel would rent a room to the Black man. He stayed with Warner and Clara Terrell in their house on 15th Street instead.

Published on August 01, 2024 04:00

July 31, 2024

Exploding Billiard Balls

I traveled down a path of good intentions today, trimmed in ivory. It led past the carcasses of elephants to gigatons of trash.

My exploration started with an article from a story in the August 4, 1864 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Headlined, “Where Our Ivory Comes From,” the piece caught my attention because I thought the answer was all too obvious. Ivory has been treasured by artisans for centuries because it is easy to carve yet durable. Elephants have been the largest source of ivory, though walrus, hippopotamus, narwhal, sperm whales, and elk all provide ivory. Providing it usually costs the animal its life.

But the 1864 article was not about elephants.

“You carry a beautiful cane—it cost $3.50—$1.50 extra, on account of its beautiful pure ivory head. Your wife has a costly fan, with a pure ivory handle. In your pocket is your pure ivory-handled pocketknife, very pretty and fine. On your table is a set of knives and forks with pure ivory handles, and little they have cost for being pure ivory. The ring in which are the reins of your costly double harness is pure ivory. The handles of parasols are pure ivory—and so on, with many articles useful and ornamental. But it happens that this “pure ivory” is manufactured from the shin bones of the dead horses of the U.S. Army.”

Well, that took a turn. I found the article by accident, which is often the case when I’m looking for interesting Idaho tidbits. I was searching for something about harness when this little piece popped up because it included that word in the text.

Encouraged by the quirkiness the article offered, I did a quick search on ivory. And that’s where the trouble began.

Early billiard balls were made of ivory. It gave the perfect heft, click, and bounce players enjoyed. But in the 1860s there was something of a billiard ball panic because ivory was allegedly in short supply. It wasn’t. Nevertheless, the belief that it was set billiard ball manufacturers on a quest for a material to replace ivory balls.

British inventor Alan Parkes came up with something he called Parkesine in 1862. It was the first plastic. It didn’t work well for billiard balls, so the quest was still on for the perfect synthetic material. John Wesley Hyatt, hoping to win a $10,000 prize from Big Billiard (a name I made up to represent the industry, so don’t call me on that) came up with celluloid. Celluloid is better known for its use in early motion picture film stock. That early film was highly flammable, and billiard balls made from celluloid had a similar, annoying feature. They exploded.

Exploding billiard balls would have been a health hazard for those who hung out in establishments where the game was played, but the explosions weren’t like grenades going off. They occasionally made a sharp pop, causing little damage even to the felt on billiard tables. The percussion sounded much like a gunshot, which reportedly caused quite a few “sports” to drop the hand of cards they’d been dealt to frantically look around the room.

Today, billiard balls are made from resin, another type of plastic. And, today, we are buried by plastic of all kinds because it shares something with the ivory it replaced. It is durable. Too durable, as it turns out.

One last note: Inventor John Wesley Hyatt never received the $10,000 prize, but he did start the Albany Billiard Ball Company. It stayed in business for 118 years.

My exploration started with an article from a story in the August 4, 1864 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Headlined, “Where Our Ivory Comes From,” the piece caught my attention because I thought the answer was all too obvious. Ivory has been treasured by artisans for centuries because it is easy to carve yet durable. Elephants have been the largest source of ivory, though walrus, hippopotamus, narwhal, sperm whales, and elk all provide ivory. Providing it usually costs the animal its life.

But the 1864 article was not about elephants.

“You carry a beautiful cane—it cost $3.50—$1.50 extra, on account of its beautiful pure ivory head. Your wife has a costly fan, with a pure ivory handle. In your pocket is your pure ivory-handled pocketknife, very pretty and fine. On your table is a set of knives and forks with pure ivory handles, and little they have cost for being pure ivory. The ring in which are the reins of your costly double harness is pure ivory. The handles of parasols are pure ivory—and so on, with many articles useful and ornamental. But it happens that this “pure ivory” is manufactured from the shin bones of the dead horses of the U.S. Army.”

Well, that took a turn. I found the article by accident, which is often the case when I’m looking for interesting Idaho tidbits. I was searching for something about harness when this little piece popped up because it included that word in the text.

Encouraged by the quirkiness the article offered, I did a quick search on ivory. And that’s where the trouble began.

Early billiard balls were made of ivory. It gave the perfect heft, click, and bounce players enjoyed. But in the 1860s there was something of a billiard ball panic because ivory was allegedly in short supply. It wasn’t. Nevertheless, the belief that it was set billiard ball manufacturers on a quest for a material to replace ivory balls.

British inventor Alan Parkes came up with something he called Parkesine in 1862. It was the first plastic. It didn’t work well for billiard balls, so the quest was still on for the perfect synthetic material. John Wesley Hyatt, hoping to win a $10,000 prize from Big Billiard (a name I made up to represent the industry, so don’t call me on that) came up with celluloid. Celluloid is better known for its use in early motion picture film stock. That early film was highly flammable, and billiard balls made from celluloid had a similar, annoying feature. They exploded.

Exploding billiard balls would have been a health hazard for those who hung out in establishments where the game was played, but the explosions weren’t like grenades going off. They occasionally made a sharp pop, causing little damage even to the felt on billiard tables. The percussion sounded much like a gunshot, which reportedly caused quite a few “sports” to drop the hand of cards they’d been dealt to frantically look around the room.

Today, billiard balls are made from resin, another type of plastic. And, today, we are buried by plastic of all kinds because it shares something with the ivory it replaced. It is durable. Too durable, as it turns out.

One last note: Inventor John Wesley Hyatt never received the $10,000 prize, but he did start the Albany Billiard Ball Company. It stayed in business for 118 years.

Published on July 31, 2024 04:00

July 30, 2024

Ellen Trueblood Loved Mushrooms

To many Idahoans, Ted Trueblood, born in Boise, was the Ernest Hemmingway of nonfiction. Through his articles in Field and Stream magazine and books about outdoor life, Trueblood taught generations how to hunt, fish, and enjoy the outdoors. He was a founding member of the Idaho Wildlife Federation and an award-winning writer.

But this column isn’t about Ted Trueblood. His fame overshadowed the remarkable accomplishments of Ellen Trueblood, Ted’s wife.

Ellen, also born in Boise, was a writer in her own right. She reported for the Boise Capital News and the Nampa Free Press. Ellen was an accomplished hunter, angler, and photographer when she met Ted Trueblood, so the match seemed a natural. Following their 1939 marriage, the Truebloods honeymooned all summer long in the Idaho wilderness. That summer cemented her already strong love for the study of nature.

In the 1950s, Ellen was an amateur collector of plants. She began to focus on something that is often overshadowed by Idaho’s beautiful wildflowers. Ellen grew passionate about fungi. Although she took a few classes, she was mostly self-taught in mycology, the scientific study of fungi. As she became more proficient, she found mentors in the field to take her to the next level. After a few years of collecting, identifying, and sharing her knowledge she became the leading expert on fungi in southwestern Idaho, eastern Oregon, and northern Nevada, concentrating mostly in the Owyhees.

Fungi in the Owyhees are mostly found beneath sagebrush, though Ellen also discovered them in desert ponds and creeks. Some are larger than a softball; some smaller than the head of a pin. If you think of mushrooms as brown, you’ve missed the colors that range from robin-egg blue through purple to vivid yellows and reds. Ellen Trueblood is credited with discovering more than 20 species of fungi.

Ellen was often seen with a slide carousel under her arm, off again to speak to a garden club about mushrooms. She had more than 2,700 slides. In 1975, when Boise State University added mycology to its curriculum, Ellen was the obvious choice to teach it.

In a 1962 article in the Idaho Free Press, Ellen Trueblood confessed a fear that many mushroom hunters have. “I spent a restless night the first time I served oyster mushrooms to my family—even though I was sure of my identification and was reassured by the book I had with me. There was that fear of toadstools that I couldn’t forget. I had to check in the night to see if my family was alive.”

After that sleepless night, she educated herself and her family on how to identify poisonous mushrooms. Her two sons, 5 and 7 at the time, could quickly spot the tell-tale signs.

Some 6,500 of Ellen’s collections are housed at the University of Michigan Herbarium in Ann Arbor, College of Idaho in Caldwell, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg. Ellen Trueblood passed away in 1994.

Note: I received a letter about Ellen from the Southern Idaho Mycological Association after this post ran the first in December of 2021. I’ve included much of it here because it adds much to Ellen’s story.

Ellen Trueblood was instrumental in forming the Southern Idaho Mycological Association, January, 1976.

Under Ellen's guidance, SIMA (Southern Idaho Mycological Association) was established as an organization of amateur mycologists dedicated to studying the ecology of fungi and its interaction with plants and animals. Mycology, like Ornithology, is one of the few sciences left with an active role for amateurs.

The North American Mycological Association contacted Ellen Trueblood and Dr. Orson K Miller Jr about establishing a mycological society affiliated with NAMA to host a national foray in the McCall area for the fall of 1976. The McCall area is a transition zone between the Blue Mountain and Rocky Mountain Biomes and is rich in diversity of fungal species. With Ellen's guidance, SIMA was formed and hosted a national mycological foray in 1976. SIMA also hosted a second national foray in September 2008.

Ellen freely shared her extensive knowledge of the fungi of Owyhee County with SIMA members, leading many short weekend forays into the Owyhee mountains.

SIMA's database of over 2000 individual species reflects Ellen's collections and other fungi collected by SIMA in Owyhee, Ada, Boise, Elmore, Canyon, Gem, Payette, Washington, Adams, Valley, Idaho Counties of Idaho plus Malheur and Baker Counties of Oregon.

SIMA still exists today, hosting spring and fall forays in the McCall area yearly, adding to the work Ellen started years ago. SIMA has a membership of 50-plus dedicated amateur scientists studying mycology.

Genille Steiner, Robert Chehey, past presidents of SIMA provided information on the organization.

Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

But this column isn’t about Ted Trueblood. His fame overshadowed the remarkable accomplishments of Ellen Trueblood, Ted’s wife.

Ellen, also born in Boise, was a writer in her own right. She reported for the Boise Capital News and the Nampa Free Press. Ellen was an accomplished hunter, angler, and photographer when she met Ted Trueblood, so the match seemed a natural. Following their 1939 marriage, the Truebloods honeymooned all summer long in the Idaho wilderness. That summer cemented her already strong love for the study of nature.

In the 1950s, Ellen was an amateur collector of plants. She began to focus on something that is often overshadowed by Idaho’s beautiful wildflowers. Ellen grew passionate about fungi. Although she took a few classes, she was mostly self-taught in mycology, the scientific study of fungi. As she became more proficient, she found mentors in the field to take her to the next level. After a few years of collecting, identifying, and sharing her knowledge she became the leading expert on fungi in southwestern Idaho, eastern Oregon, and northern Nevada, concentrating mostly in the Owyhees.

Fungi in the Owyhees are mostly found beneath sagebrush, though Ellen also discovered them in desert ponds and creeks. Some are larger than a softball; some smaller than the head of a pin. If you think of mushrooms as brown, you’ve missed the colors that range from robin-egg blue through purple to vivid yellows and reds. Ellen Trueblood is credited with discovering more than 20 species of fungi.

Ellen was often seen with a slide carousel under her arm, off again to speak to a garden club about mushrooms. She had more than 2,700 slides. In 1975, when Boise State University added mycology to its curriculum, Ellen was the obvious choice to teach it.

In a 1962 article in the Idaho Free Press, Ellen Trueblood confessed a fear that many mushroom hunters have. “I spent a restless night the first time I served oyster mushrooms to my family—even though I was sure of my identification and was reassured by the book I had with me. There was that fear of toadstools that I couldn’t forget. I had to check in the night to see if my family was alive.”

After that sleepless night, she educated herself and her family on how to identify poisonous mushrooms. Her two sons, 5 and 7 at the time, could quickly spot the tell-tale signs.

Some 6,500 of Ellen’s collections are housed at the University of Michigan Herbarium in Ann Arbor, College of Idaho in Caldwell, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg. Ellen Trueblood passed away in 1994.

Note: I received a letter about Ellen from the Southern Idaho Mycological Association after this post ran the first in December of 2021. I’ve included much of it here because it adds much to Ellen’s story.

Ellen Trueblood was instrumental in forming the Southern Idaho Mycological Association, January, 1976.

Under Ellen's guidance, SIMA (Southern Idaho Mycological Association) was established as an organization of amateur mycologists dedicated to studying the ecology of fungi and its interaction with plants and animals. Mycology, like Ornithology, is one of the few sciences left with an active role for amateurs.

The North American Mycological Association contacted Ellen Trueblood and Dr. Orson K Miller Jr about establishing a mycological society affiliated with NAMA to host a national foray in the McCall area for the fall of 1976. The McCall area is a transition zone between the Blue Mountain and Rocky Mountain Biomes and is rich in diversity of fungal species. With Ellen's guidance, SIMA was formed and hosted a national mycological foray in 1976. SIMA also hosted a second national foray in September 2008.

Ellen freely shared her extensive knowledge of the fungi of Owyhee County with SIMA members, leading many short weekend forays into the Owyhee mountains.

SIMA's database of over 2000 individual species reflects Ellen's collections and other fungi collected by SIMA in Owyhee, Ada, Boise, Elmore, Canyon, Gem, Payette, Washington, Adams, Valley, Idaho Counties of Idaho plus Malheur and Baker Counties of Oregon.

SIMA still exists today, hosting spring and fall forays in the McCall area yearly, adding to the work Ellen started years ago. SIMA has a membership of 50-plus dedicated amateur scientists studying mycology.

Genille Steiner, Robert Chehey, past presidents of SIMA provided information on the organization.

Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

Published on July 30, 2024 04:00

July 29, 2024

A Press on Fire

In 1937, Caxton Printers was ready to celebrate its 30th anniversary. Starting as a printing and office services company, the printer had also begun publishing books in 1925 as Caxton Press. In January of 1937, Caxton released Idaho: A Guide in Word and Pictures by Vardis Fisher, the first book from the Works Project Administration. It looked like a banner year for the company.

Then, on the morning of St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1937, someone in the building noticed smoke. Just after 9 a.m., word ran through the offices that there was a fire in the west stockroom, where countless books and printing supplies were stored. Employees scrambled to put the fire out with fire extinguishers, but the blaze had a good hold. Flames roared in a flash up the wall and into the second-floor offices.

There wasn’t even time to close the office safes before employees were forced to escape through fire and smoke down the back stairs.

The head of the offset printing department on the east side of the building, G.H. Spurgeon, grabbed three expensive camera lenses before jumping through a window. Other employees scrambled to get equipment out, including two small lithographic presses.

A stroke of luck protected many of the company’s records. One of the office safes, door open, crashed through the weakened floor of the building. The door slammed shut when it landed, saving the contents.

The fire did not reach the basement, but the water firefighters used to quench the blaze cascaded into the $50,000 worth of school supplies stored there, ruining them.

The second edition of Fisher’s Idaho Guide was under production at the time of the fire. About 15 minutes before the alarm sounded, a truckload of pictures left the lithographic department and went to the bindery room, where they were destroyed.

Annuals for Northwest Nazarene College, Gooding College, the University of Idaho Southern branch (now ISU), the College of Idaho, and Albion State Normal School, along with those of seven area high schools, were under production at the time. The fire got them all.

Many books under production were also destroyed, but the publishing company's owners and staff showed remarkable resilience. As the sun was setting on the day of the fire—the largest in Caldwell history at that time—crews were working on various projects at other nearby printing companies. A board of directors meeting took place that same night to select equipment to be shipped in for a new plant. Orders for the equipment went out the next day.

Caxton Printers and Publishing erected a much larger building and kept one of the most famous publishing houses in the West alive. It still thrives in Caldwell today.

Why did J.H. Gipson choose to call his printing company Caxton? A man named William Caxton produced the first book printed in English in 1473 in Bruges, Belgium. In 1476, he was the first to bring a press to England, his home country. The first book he printed was a version of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. A.E. Gipson borrowed not only the name but also William Caxton’s printer's mark (below), which is used to this day on Caxton’s books to honor that early printer.

For more on the history of Caxton Press, watch Idaho Experience on Idaho Public Television. The Caxton Press story previewed December 5, 2021. Here’s a link to the story.

Then, on the morning of St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1937, someone in the building noticed smoke. Just after 9 a.m., word ran through the offices that there was a fire in the west stockroom, where countless books and printing supplies were stored. Employees scrambled to put the fire out with fire extinguishers, but the blaze had a good hold. Flames roared in a flash up the wall and into the second-floor offices.

There wasn’t even time to close the office safes before employees were forced to escape through fire and smoke down the back stairs.

The head of the offset printing department on the east side of the building, G.H. Spurgeon, grabbed three expensive camera lenses before jumping through a window. Other employees scrambled to get equipment out, including two small lithographic presses.

A stroke of luck protected many of the company’s records. One of the office safes, door open, crashed through the weakened floor of the building. The door slammed shut when it landed, saving the contents.

The fire did not reach the basement, but the water firefighters used to quench the blaze cascaded into the $50,000 worth of school supplies stored there, ruining them.

The second edition of Fisher’s Idaho Guide was under production at the time of the fire. About 15 minutes before the alarm sounded, a truckload of pictures left the lithographic department and went to the bindery room, where they were destroyed.

Annuals for Northwest Nazarene College, Gooding College, the University of Idaho Southern branch (now ISU), the College of Idaho, and Albion State Normal School, along with those of seven area high schools, were under production at the time. The fire got them all.

Many books under production were also destroyed, but the publishing company's owners and staff showed remarkable resilience. As the sun was setting on the day of the fire—the largest in Caldwell history at that time—crews were working on various projects at other nearby printing companies. A board of directors meeting took place that same night to select equipment to be shipped in for a new plant. Orders for the equipment went out the next day.

Caxton Printers and Publishing erected a much larger building and kept one of the most famous publishing houses in the West alive. It still thrives in Caldwell today.

Why did J.H. Gipson choose to call his printing company Caxton? A man named William Caxton produced the first book printed in English in 1473 in Bruges, Belgium. In 1476, he was the first to bring a press to England, his home country. The first book he printed was a version of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. A.E. Gipson borrowed not only the name but also William Caxton’s printer's mark (below), which is used to this day on Caxton’s books to honor that early printer.

For more on the history of Caxton Press, watch Idaho Experience on Idaho Public Television. The Caxton Press story previewed December 5, 2021. Here’s a link to the story.

Published on July 29, 2024 04:00

July 28, 2024

The Ferry Idaho Burns

Idaho's Lake Coeur d'Alene was known especially for its steamships that slid back and forth across the waters from the 1880s to the 1930s. One of the better-known boats was the sidewheeler, Idaho.

Would it surprise you to learn that a steamboat named Idaho burned to the waterline and sank on November 26, 1866? This Idaho never knew Lake Coeur d'Alene. Instead, it worked the waters of the East River, New York City.

The Idaho was one of the newer boats of the Brooklyn Ferry Company. Shortly after leaving the dock at about 7:10 in the evening, what may have been a smoldering fire broke through the ferry's deck and started to consume the Idaho rapidly. Fortunately, a sister ferry, the Canada, was nearby. The captain of the Canada pulled alongside the burning boat long enough for most of the passengers to jump aboard. Heavy flames forced the Canada to pull away before everyone could get aboard. A woman and her child jumped into the water and were saved from drowning by two men. One of the men suffered serious burns in the rescue, but there were no fatalities.

The Idaho, which was not insured, was a total loss. Authorities estimated it was worth $64,000.

The fire aboard a boat named after the state didn't cause a ripple in Idaho newspapers at the time, so it falls to me to break the news to you 157 years later. You're welcome.

[image error] Newspaper depiction of the Idaho on fire.

Would it surprise you to learn that a steamboat named Idaho burned to the waterline and sank on November 26, 1866? This Idaho never knew Lake Coeur d'Alene. Instead, it worked the waters of the East River, New York City.

The Idaho was one of the newer boats of the Brooklyn Ferry Company. Shortly after leaving the dock at about 7:10 in the evening, what may have been a smoldering fire broke through the ferry's deck and started to consume the Idaho rapidly. Fortunately, a sister ferry, the Canada, was nearby. The captain of the Canada pulled alongside the burning boat long enough for most of the passengers to jump aboard. Heavy flames forced the Canada to pull away before everyone could get aboard. A woman and her child jumped into the water and were saved from drowning by two men. One of the men suffered serious burns in the rescue, but there were no fatalities.

The Idaho, which was not insured, was a total loss. Authorities estimated it was worth $64,000.

The fire aboard a boat named after the state didn't cause a ripple in Idaho newspapers at the time, so it falls to me to break the news to you 157 years later. You're welcome.

[image error] Newspaper depiction of the Idaho on fire.

Published on July 28, 2024 04:00

July 27, 2024

UXB Boise

The purpose of a fuse in the placement of dynamite is to give the person lighting the charge time to get away. Typically, that time is measured in seconds, not years.

While building a road along the bank of the New York Canal in 1900, the crew doing the dirt work found a fuse. Digging a little more carefully, they found the fuse was attached to a charge of dynamite. Rather than move what might be an unstable explosive, they chose to light the fuse and light out of there. The dynamite went off, just as whoever had set the charge ten years earlier had intended.

Speculation was that the lost explosive had been put in place while another crew was digging the New York Canal in 1890. Maybe they stopped for lunch, or they went home at the end of the day forgetting about that particular charge, which was planted near the Foote House just below where Lucky Peak Dam is today. Whoever placed the dynamite and inserted the fuse probably never thought it would have a ten-year delay.

While building a road along the bank of the New York Canal in 1900, the crew doing the dirt work found a fuse. Digging a little more carefully, they found the fuse was attached to a charge of dynamite. Rather than move what might be an unstable explosive, they chose to light the fuse and light out of there. The dynamite went off, just as whoever had set the charge ten years earlier had intended.

Speculation was that the lost explosive had been put in place while another crew was digging the New York Canal in 1890. Maybe they stopped for lunch, or they went home at the end of the day forgetting about that particular charge, which was planted near the Foote House just below where Lucky Peak Dam is today. Whoever placed the dynamite and inserted the fuse probably never thought it would have a ten-year delay.

Published on July 27, 2024 04:00

July 26, 2024

The Sun Dance

When you think of dancing today, images of people having fun probably pop into your head. Yet, dancing has been prohibited in many places throughout history. Some adherents to religions, from Islam to Baptists, forbid dancing.

Dance is a vital part of other religions. That brings us to a moment in Idaho history where a particular dance was outlawed.

A headline in the Blackfoot Optimist in 1912 read, “Last Indian Sun Dance.” The tribes of the Fort Hall reservation were about to hold what would “be the last dance ever held on the reservation.”

The Indian Department in Washington, DC had issued an edict that the tribal custom of holding a sun dance would be prohibited in future years. Why? “It is claimed by those in authority that those dances interfere with and retard the process of teaching the Indians the necessity of following the white man’s example of engaging in agricultural pursuits, rather than those of their more savage ancestry,” the article explained.

Sun dances seem to have originated with the plains Indians. However, by the late 1900s, they had spread to the Shoshone of Wyoming and Idaho. The days-long ceremonies varied by tribe and varied from year to year depending on the vision a medicine man had received.

You may think of sun dances as the ritual where a warrior’s pectoral muscles are pierced and rawhide thongs run through the piercings. In that version, a rope is tied to a center pole and the embedded thongs while the warrior leans back to endure the pain. While some sun dances feature that display of personal sacrifice, they more commonly involve tribal members dancing from the center pole and back to the edge for hours on end, often fainting from exhaustion.

In the Shoshone Sun Dance, tribal members erected a circular enclosure of poles and brush, about 60-75 feet in diameter. The center pole was cut from a birch tree ceremonially chosen for that purpose.

A 1918 story in the Idaho Republican described the dance this way: “Around the edge of the dancing space were a number of peeled poles to which the dancers could hold or rest against when not in action. Each dancer had his own particular station, and the method of dancing was to dance straight up to the center pole and then backwards to the station to the outer ring.” The dance described in that article lasted “from sunset Tuesday to sunrise Saturday.”

That 1918 story, as clever readers will note, came after the “last dance” story in the Blackfoot paper in 1912. That’s because tribal members had held the dance despite the prohibition. They did so regularly and continue the tradition today. In 1978, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which codified the right of Native Americans to freely practice their religious rights, including the Sun Dance.

In that same 1912 paper that mentioned their “savage ancestry,” the writer was troubled by the discontinuation of the ritual. “In compelling them to discontinue one of the most sacred forms of religion, there is a question as to whether any man has a right to forcibly interfere with anyone’s religious belief.”

Indeed.

Shoshone Sun Dance. (2023, December 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_Dance

Shoshone Sun Dance. (2023, December 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_Dance

Dance is a vital part of other religions. That brings us to a moment in Idaho history where a particular dance was outlawed.

A headline in the Blackfoot Optimist in 1912 read, “Last Indian Sun Dance.” The tribes of the Fort Hall reservation were about to hold what would “be the last dance ever held on the reservation.”

The Indian Department in Washington, DC had issued an edict that the tribal custom of holding a sun dance would be prohibited in future years. Why? “It is claimed by those in authority that those dances interfere with and retard the process of teaching the Indians the necessity of following the white man’s example of engaging in agricultural pursuits, rather than those of their more savage ancestry,” the article explained.

Sun dances seem to have originated with the plains Indians. However, by the late 1900s, they had spread to the Shoshone of Wyoming and Idaho. The days-long ceremonies varied by tribe and varied from year to year depending on the vision a medicine man had received.

You may think of sun dances as the ritual where a warrior’s pectoral muscles are pierced and rawhide thongs run through the piercings. In that version, a rope is tied to a center pole and the embedded thongs while the warrior leans back to endure the pain. While some sun dances feature that display of personal sacrifice, they more commonly involve tribal members dancing from the center pole and back to the edge for hours on end, often fainting from exhaustion.

In the Shoshone Sun Dance, tribal members erected a circular enclosure of poles and brush, about 60-75 feet in diameter. The center pole was cut from a birch tree ceremonially chosen for that purpose.

A 1918 story in the Idaho Republican described the dance this way: “Around the edge of the dancing space were a number of peeled poles to which the dancers could hold or rest against when not in action. Each dancer had his own particular station, and the method of dancing was to dance straight up to the center pole and then backwards to the station to the outer ring.” The dance described in that article lasted “from sunset Tuesday to sunrise Saturday.”

That 1918 story, as clever readers will note, came after the “last dance” story in the Blackfoot paper in 1912. That’s because tribal members had held the dance despite the prohibition. They did so regularly and continue the tradition today. In 1978, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which codified the right of Native Americans to freely practice their religious rights, including the Sun Dance.

In that same 1912 paper that mentioned their “savage ancestry,” the writer was troubled by the discontinuation of the ritual. “In compelling them to discontinue one of the most sacred forms of religion, there is a question as to whether any man has a right to forcibly interfere with anyone’s religious belief.”

Indeed.

Shoshone Sun Dance. (2023, December 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_Dance

Shoshone Sun Dance. (2023, December 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_Dance

Published on July 26, 2024 04:00

July 25, 2024

I Get Grief

I sometimes get comments on my posts that the picture I am using for a story is deceptive.

All of my posts include a photo. Posts without a photo get about as much attention as a blank sheet of paper. Since I write about history, there isn’t always a photo that goes along with the historical event. This is particularly true for events that took place before the invention of photography. Technically, all of Idaho history has taken place since photography was invented (1863), but unlike today, people didn’t have smartphones to capture it from 40 different angles.

So, I illustrate many of my posts with a photo that is somehow related to the story but not of the story. If the story is about a stagecoach robbery, I might illustrate it with a stagecoach, pointing out in the caption that this is not the stagecoach.

People let those posts slide by without telling me how awful I am, but some are immediately incensed if I attempt a little humor to get their attention. Here are some examples.

I used the above illustration for a story about the ice fire of 1929. I didn't label it as an illustration rather than a photo of the fire.

I used the above illustration for a story about the ice fire of 1929. I didn't label it as an illustration rather than a photo of the fire.  This photo illustration accompanied a story about Boxcar Willie burning records by the Beatles. No one was offended by this or, at least, they didn't say they were.

This photo illustration accompanied a story about Boxcar Willie burning records by the Beatles. No one was offended by this or, at least, they didn't say they were.  No one was offended, or fooled, by the photo illustration above that went with a story about an ore spill on Lake Coeur d'Alene.

No one was offended, or fooled, by the photo illustration above that went with a story about an ore spill on Lake Coeur d'Alene.  But, this one drove people crazy. It went with a story about a long-ago failed scheme to put a hotel on top of Table Rock. Silly me, I thought since this is obviously an over-sized photo of the Idanha plopped on top of the butte, that people would not be confused. People who actually read the story seemed okay with it, but several people who commented after seeing only the picture thought I was trying to fool them.

But, this one drove people crazy. It went with a story about a long-ago failed scheme to put a hotel on top of Table Rock. Silly me, I thought since this is obviously an over-sized photo of the Idanha plopped on top of the butte, that people would not be confused. People who actually read the story seemed okay with it, but several people who commented after seeing only the picture thought I was trying to fool them.  This photo, captioned: "Artist's depiction of what this sign in Arco might look like if they'd kept that colorful name" is my all-time top offender. The story was about the first name of the town. I hope Arco residents aren't so thin-skinned that this gives them hives. I put this in the same category as the joke I've heard about my own hometown of Firth a few times. When I tell people that's where I'm from, they sometimes say, "Is that anywhere near Thecond?"

This photo, captioned: "Artist's depiction of what this sign in Arco might look like if they'd kept that colorful name" is my all-time top offender. The story was about the first name of the town. I hope Arco residents aren't so thin-skinned that this gives them hives. I put this in the same category as the joke I've heard about my own hometown of Firth a few times. When I tell people that's where I'm from, they sometimes say, "Is that anywhere near Thecond?"

I'll continue to use photo illustrations to go along with my stories from time to time. If you are offended, please let me know. I'll refund what you paid.

All of my posts include a photo. Posts without a photo get about as much attention as a blank sheet of paper. Since I write about history, there isn’t always a photo that goes along with the historical event. This is particularly true for events that took place before the invention of photography. Technically, all of Idaho history has taken place since photography was invented (1863), but unlike today, people didn’t have smartphones to capture it from 40 different angles.

So, I illustrate many of my posts with a photo that is somehow related to the story but not of the story. If the story is about a stagecoach robbery, I might illustrate it with a stagecoach, pointing out in the caption that this is not the stagecoach.

People let those posts slide by without telling me how awful I am, but some are immediately incensed if I attempt a little humor to get their attention. Here are some examples.

I used the above illustration for a story about the ice fire of 1929. I didn't label it as an illustration rather than a photo of the fire.

I used the above illustration for a story about the ice fire of 1929. I didn't label it as an illustration rather than a photo of the fire.  This photo illustration accompanied a story about Boxcar Willie burning records by the Beatles. No one was offended by this or, at least, they didn't say they were.

This photo illustration accompanied a story about Boxcar Willie burning records by the Beatles. No one was offended by this or, at least, they didn't say they were.  No one was offended, or fooled, by the photo illustration above that went with a story about an ore spill on Lake Coeur d'Alene.

No one was offended, or fooled, by the photo illustration above that went with a story about an ore spill on Lake Coeur d'Alene.  But, this one drove people crazy. It went with a story about a long-ago failed scheme to put a hotel on top of Table Rock. Silly me, I thought since this is obviously an over-sized photo of the Idanha plopped on top of the butte, that people would not be confused. People who actually read the story seemed okay with it, but several people who commented after seeing only the picture thought I was trying to fool them.

But, this one drove people crazy. It went with a story about a long-ago failed scheme to put a hotel on top of Table Rock. Silly me, I thought since this is obviously an over-sized photo of the Idanha plopped on top of the butte, that people would not be confused. People who actually read the story seemed okay with it, but several people who commented after seeing only the picture thought I was trying to fool them.  This photo, captioned: "Artist's depiction of what this sign in Arco might look like if they'd kept that colorful name" is my all-time top offender. The story was about the first name of the town. I hope Arco residents aren't so thin-skinned that this gives them hives. I put this in the same category as the joke I've heard about my own hometown of Firth a few times. When I tell people that's where I'm from, they sometimes say, "Is that anywhere near Thecond?"

This photo, captioned: "Artist's depiction of what this sign in Arco might look like if they'd kept that colorful name" is my all-time top offender. The story was about the first name of the town. I hope Arco residents aren't so thin-skinned that this gives them hives. I put this in the same category as the joke I've heard about my own hometown of Firth a few times. When I tell people that's where I'm from, they sometimes say, "Is that anywhere near Thecond?" I'll continue to use photo illustrations to go along with my stories from time to time. If you are offended, please let me know. I'll refund what you paid.

Published on July 25, 2024 04:00

July 24, 2024

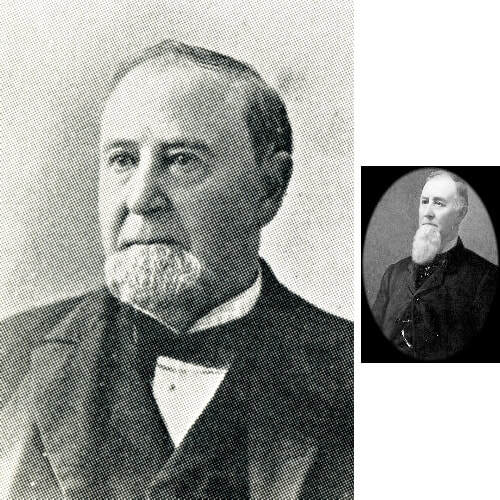

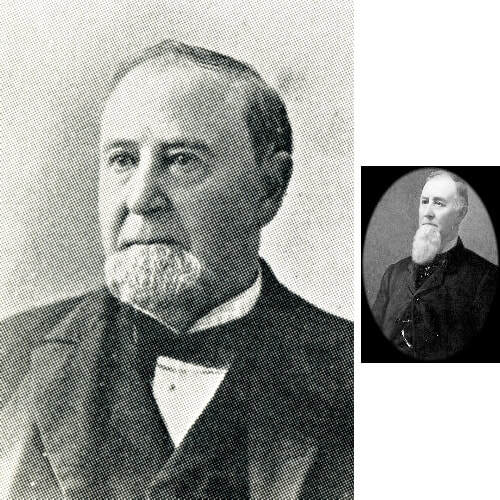

The Governors Stevenson

Edward A. Stevenson was the governor of Idaho Territory from October 10, 1885, to April 30, 1889. Governors during territorial days were all appointed by the president. The qualifications for the post were scant, beyond knowing the president or knowing someone who knew the president.

Stevenson, though, had some qualifications. One of the forty-niners drawn to the West by gold, he had been a Justice of the Peace and a state legislator while living in California. He rose to be the Speaker pro-Tempore in the legislature. He also served at one time or another as a deputy sheriff and the mayor of Coloma, California.

In 1863, Stevenson followed rumors of gold to Idaho, settling in the Boise Basin. The following year he was elected as a Justice of the Peace. He ran for the Idaho Territorial Legislature half a dozen times, winning half those races, and ultimately became Speaker of the House.

Having some solid political credentials wasn’t Stevenson’s only claim to fame. He was the first Idaho Territorial Governor who resided in the state at the time of his appointment. He was also the only Democrat to serve as governor of the territory.

Edward A. Stevenson probably gave some pointers about being a governor to his older brother, Charles C. Stevenson, who was governor of the State of Nevada from January 3, 1887, to September 21, 1890. The terms of the brother governors overlapped for a couple of years.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Stevenson, though, had some qualifications. One of the forty-niners drawn to the West by gold, he had been a Justice of the Peace and a state legislator while living in California. He rose to be the Speaker pro-Tempore in the legislature. He also served at one time or another as a deputy sheriff and the mayor of Coloma, California.

In 1863, Stevenson followed rumors of gold to Idaho, settling in the Boise Basin. The following year he was elected as a Justice of the Peace. He ran for the Idaho Territorial Legislature half a dozen times, winning half those races, and ultimately became Speaker of the House.

Having some solid political credentials wasn’t Stevenson’s only claim to fame. He was the first Idaho Territorial Governor who resided in the state at the time of his appointment. He was also the only Democrat to serve as governor of the territory.

Edward A. Stevenson probably gave some pointers about being a governor to his older brother, Charles C. Stevenson, who was governor of the State of Nevada from January 3, 1887, to September 21, 1890. The terms of the brother governors overlapped for a couple of years.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Published on July 24, 2024 04:00

July 23, 2024

Please Don't Drink the Snakes

Newspapers in 19th-century Idaho contained stories from all over the state long before wire services. This was possible because of some progressive thinking in Congress. Yes, you read that right.

In the early 1800s, Congress allowed publishers to send their newspapers to other publishers for free through the US Postal Service. This newspaper exchange was an important program to encourage freedom of the press. Unfortunately, it did have at least a couple of unintended consequences.

Land promoters sometimes threw together a tiny newspaper in their otherwise barren community to extoll the virtues of their particular tract of sagebrush. Knowing no better, editors of newspapers in other parts of the country would pick up the story and run it just as if it were true. “I read it in the newspaper” was likely proof for many that something was so. If this reminds you of people “doing my own research” online today, you are not alone.

Land scams probably caught more people a thousand miles away than Idahoans in neighboring communities. That doesn’t mean the practice of sharing stories from other newspapers was always a positive thing. For instance, readers in Sandpoint probably didn’t care much about what an average citizen in Blackfoot was doing, even though it might be exciting news locally. But newspapers would pick up quirky or scandalous stories because they knew that would interest their readers. This tended to skew the news toward sensationalism.

I recently ran across a story with an Idaho connection that had made the rounds. It was quirky, sensational, and certainly a complete figment of someone’s imagination. I saw it in an 1866 issue of the Vincennes Times, a newspaper in Vincennes, Indiana. They had picked up the story from the Newville, Pennsylvania Star of the Valley. It seems that a young man visiting Idaho about four months previous had been drinking from a small pond. While quenching his thirst, a snake found its way into his mouth and slipped all the way down into his stomach.

The young man did not feel good about it. He was sure he was about to die, so he went home to Pennsylvania to do so.

The victim consulted several medical men about his snake-in-the-stomach problem, complaining especially that he couldn’t shake a feeling of cold in that region of his body. Several things—unlisted—were tried without success. Finally, a doctor prescribed an emetic. The young man vomited up an 18-inch-long snake, which tried to take its revenge by trying to strangle him when it came out.

And that’s the news for today.

In the early 1800s, Congress allowed publishers to send their newspapers to other publishers for free through the US Postal Service. This newspaper exchange was an important program to encourage freedom of the press. Unfortunately, it did have at least a couple of unintended consequences.

Land promoters sometimes threw together a tiny newspaper in their otherwise barren community to extoll the virtues of their particular tract of sagebrush. Knowing no better, editors of newspapers in other parts of the country would pick up the story and run it just as if it were true. “I read it in the newspaper” was likely proof for many that something was so. If this reminds you of people “doing my own research” online today, you are not alone.

Land scams probably caught more people a thousand miles away than Idahoans in neighboring communities. That doesn’t mean the practice of sharing stories from other newspapers was always a positive thing. For instance, readers in Sandpoint probably didn’t care much about what an average citizen in Blackfoot was doing, even though it might be exciting news locally. But newspapers would pick up quirky or scandalous stories because they knew that would interest their readers. This tended to skew the news toward sensationalism.

I recently ran across a story with an Idaho connection that had made the rounds. It was quirky, sensational, and certainly a complete figment of someone’s imagination. I saw it in an 1866 issue of the Vincennes Times, a newspaper in Vincennes, Indiana. They had picked up the story from the Newville, Pennsylvania Star of the Valley. It seems that a young man visiting Idaho about four months previous had been drinking from a small pond. While quenching his thirst, a snake found its way into his mouth and slipped all the way down into his stomach.

The young man did not feel good about it. He was sure he was about to die, so he went home to Pennsylvania to do so.

The victim consulted several medical men about his snake-in-the-stomach problem, complaining especially that he couldn’t shake a feeling of cold in that region of his body. Several things—unlisted—were tried without success. Finally, a doctor prescribed an emetic. The young man vomited up an 18-inch-long snake, which tried to take its revenge by trying to strangle him when it came out.

And that’s the news for today.

Published on July 23, 2024 04:00