Rick Just's Blog, page 14

August 21, 2024

A Terrible Tiger Tale

I often stagger down the halls of history, careening off the walls and sometimes stumbling into a cobweb-filled room that has been long forgotten. Such was the case recently when I tried to match up a cool photo of a circus parade in Blackfoot with a story from contemporaneous newspapers. It turned out there wasn’t much more to say about the Blackfoot photo but searching for the circus name turned up a story from Twin Falls that is graphic enough for me to warn those who might have delicate constitutions to turn back. Now.

On May 26, 1907 the Sells-Floto Circus set up tents in Twin Falls. They advertised “100 startling, superb, sensational and stupendous surprises.” The number of surprises might have been off a bit, but surprises there were.

The circus had some headliners named Markel and Agnes, a pair of tigers. Handlers were in the process of feeding the big cats when Markel began to beat furiously against the cage door with his front paws. The door gave way and the tiger leapt on the nearest thing that looked like food, a Shetland pony, and began tearing at its neck. The tiger keeper whacked Markel between the eyes with an iron bar. The cat jumped off the little horse and onto the back of a second Shetland. The keeper tried the trick with the bar again, causing the tiger to repeat his retreat, only to leap onto the back of a third pony. A third whack to the face with an iron bar drove the tiger off the Shetland and into the crowd, perhaps not the result the keeper was hoping for.

As the news service story stated, “A panic followed. Women grasped their children and dragged them from the path of the maddened animal.

“The screams of the frightened spectators mingled with the trumpeting of the elephants and the cries of excited animals in the cages.”

Mrs. S. E. Rosell tried to pull her four-year-old daughter, Ruth, out of the way, to no avail. The cat knocked them down. “Holding the mother with his paws the tiger sank his teeth in the neck of the child.”

Local blacksmith J.W. Bell pushed his own family aside then aimed his .32 caliber revolver at the tiger from three feet away. The big cat took six bullets before finally collapsing.

Sadly, Ruth Rosell died from her wounds a couple of hours later.

Devastating as the experience must have been, the circus—the same circus—was back in Twin Falls for another show the following year. You’ve heard the saying, “The show must go on,” right?

UPDATE: Since I first posted this story in 2019, Carol Barret, great-granddaughter of J.W. Bell contacted me with a little more detail about the story.

It seems that the custom of the time regarding firearms was changing. Many venues, including the circus, discouraged sidearms at public gatherings. John Bell “felt naked” without his gun, so he put it on underneath his trousers.

There’s little humor in this story, but one moment of it might have been when Bell ducked behind a tent pole to drop his pants so he could get the pistol out.

The tiger got close enough to Bell that some of the entry wounds showed powder burns.

The owner of the tiger made some noise about suing John Bell for destroying his valuable animal. That was ridiculous on its face, so never happened. I couldn’t track it, but I would be surprised if the family of the girl who died didn’t sue the circus.

Carol Barret said that her great-grandfather had a tiger claw on his watch chain for some years. She heard that a newspaper in Colorado displayed the pelt from the tiger on an office wall. I couldn’t find confirmation of that.

John Bell

John Bell

On May 26, 1907 the Sells-Floto Circus set up tents in Twin Falls. They advertised “100 startling, superb, sensational and stupendous surprises.” The number of surprises might have been off a bit, but surprises there were.

The circus had some headliners named Markel and Agnes, a pair of tigers. Handlers were in the process of feeding the big cats when Markel began to beat furiously against the cage door with his front paws. The door gave way and the tiger leapt on the nearest thing that looked like food, a Shetland pony, and began tearing at its neck. The tiger keeper whacked Markel between the eyes with an iron bar. The cat jumped off the little horse and onto the back of a second Shetland. The keeper tried the trick with the bar again, causing the tiger to repeat his retreat, only to leap onto the back of a third pony. A third whack to the face with an iron bar drove the tiger off the Shetland and into the crowd, perhaps not the result the keeper was hoping for.

As the news service story stated, “A panic followed. Women grasped their children and dragged them from the path of the maddened animal.

“The screams of the frightened spectators mingled with the trumpeting of the elephants and the cries of excited animals in the cages.”

Mrs. S. E. Rosell tried to pull her four-year-old daughter, Ruth, out of the way, to no avail. The cat knocked them down. “Holding the mother with his paws the tiger sank his teeth in the neck of the child.”

Local blacksmith J.W. Bell pushed his own family aside then aimed his .32 caliber revolver at the tiger from three feet away. The big cat took six bullets before finally collapsing.

Sadly, Ruth Rosell died from her wounds a couple of hours later.

Devastating as the experience must have been, the circus—the same circus—was back in Twin Falls for another show the following year. You’ve heard the saying, “The show must go on,” right?

UPDATE: Since I first posted this story in 2019, Carol Barret, great-granddaughter of J.W. Bell contacted me with a little more detail about the story.

It seems that the custom of the time regarding firearms was changing. Many venues, including the circus, discouraged sidearms at public gatherings. John Bell “felt naked” without his gun, so he put it on underneath his trousers.

There’s little humor in this story, but one moment of it might have been when Bell ducked behind a tent pole to drop his pants so he could get the pistol out.

The tiger got close enough to Bell that some of the entry wounds showed powder burns.

The owner of the tiger made some noise about suing John Bell for destroying his valuable animal. That was ridiculous on its face, so never happened. I couldn’t track it, but I would be surprised if the family of the girl who died didn’t sue the circus.

Carol Barret said that her great-grandfather had a tiger claw on his watch chain for some years. She heard that a newspaper in Colorado displayed the pelt from the tiger on an office wall. I couldn’t find confirmation of that.

John Bell

John Bell

Published on August 21, 2024 04:00

August 20, 2024

That Bat Wing Gas Station

A building doesn’t have to be large to be architecturally significant. A gas station built in 1964 on State Street in Boise has made a big splash recently among people who appreciate mid-century modern architecture.

According to Dan Everheart of the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office, In 1956, Clarence Reinhardt, the corporate architect for Phillips Petroleum, began to experiment with dramatic V-shaped canopies at the company’s branded filling stations. By 1960, a harlequin paint scheme and Reinhardt’s “bat wing” canopy were launched as the “New Look” of the Phillips architectural brand. Phillips 66 station in Boise was one example.

State Street is also SH 44, so the station was called the Forty-Four and Sixty-Six Service Station. It only lasted as a gas station for about ten years. Milan and Blazena Kral purchased the building in 1977 and operated a German car repair shop there for 20 years. The Krals were defectors from Soviet Czechoslovakia who made a new life in Boise. Their son and daughter-in-law rehabilitated the building in 2020.

The building now houses Design Vim, a sustainable design company.

Preservation Idaho gave an Orchid award to the redevelopment project in 2020. It's also on the cover of a recent report from the National Park Service about the success of the Federal Historic Tax Credit program. The owners of the building received the tax credit for restoration. You can read more about it by downloading the federal report here.

According to Dan Everheart of the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office, In 1956, Clarence Reinhardt, the corporate architect for Phillips Petroleum, began to experiment with dramatic V-shaped canopies at the company’s branded filling stations. By 1960, a harlequin paint scheme and Reinhardt’s “bat wing” canopy were launched as the “New Look” of the Phillips architectural brand. Phillips 66 station in Boise was one example.

State Street is also SH 44, so the station was called the Forty-Four and Sixty-Six Service Station. It only lasted as a gas station for about ten years. Milan and Blazena Kral purchased the building in 1977 and operated a German car repair shop there for 20 years. The Krals were defectors from Soviet Czechoslovakia who made a new life in Boise. Their son and daughter-in-law rehabilitated the building in 2020.

The building now houses Design Vim, a sustainable design company.

Preservation Idaho gave an Orchid award to the redevelopment project in 2020. It's also on the cover of a recent report from the National Park Service about the success of the Federal Historic Tax Credit program. The owners of the building received the tax credit for restoration. You can read more about it by downloading the federal report here.

Published on August 20, 2024 04:00

August 19, 2024

An Idaho-Promoting Governor

John T. Morrison was an unremarkable governor, Idaho’s sixth, serving just two years 1903-1905. He was an attorney from Pennsylvania who graduated from the Cornell School of Law and moved to the new state of Idaho in 1890. Morrison was instrumental in establishing the College of Idaho where he served as one of the first faculty members.

His political resume was short. He failed in a run for a legislative seat in 1896. Following that, he served as chair of the Republican Party for three years. The Republicans nominated him for governor, and he won a two-year term in 1903. The party was not moved to nominate him for another term, choosing Frank R. Gooding to run instead.

Under Morrison’s governorship, the state established an organization to monitor weights and measures, enacted a pure food law, and built the reform school at St. Anthony.

I was moved to write a sparse little piece about him because I ran across a blurb he had written for the October 15, 1903, edition of Leslie’s Weekly. The newspaper was quite popular for several decades, its claim to fame being the elaborate illustrations of current events included in every issue. This edition featured an Idaho mining scene on the cover. Inside was Governor Morrison’s chamber-of-commerce-esque piece, to wit:

“IDAHO INVITES attention. There is much of interest to the world within her borders. Her people are active, intelligent Americans for whom no excuse is needed and with whom one finds pleasure and profit in living. Her rich and diversified resources challenge comparison. They are quickly developed and yield ready profits. It may well be doubted if there is a State in the Union which to-day offers as inviting a field for the profitable investment of energy and industry. This fact is having wide announcement. The world is learning of the beauties and bounties of “the Gem of the Mountains.” The home-seeker and investor are attracted hither. Twenty-five thousand settlers have come to the State since January 1st, 1903, and capital knocks for admission to our mines, forests, and fields. The next ten years will witness marvelous development in Idaho.”

Who could resist?

Governor Morris and family.

Governor Morris and family.

His political resume was short. He failed in a run for a legislative seat in 1896. Following that, he served as chair of the Republican Party for three years. The Republicans nominated him for governor, and he won a two-year term in 1903. The party was not moved to nominate him for another term, choosing Frank R. Gooding to run instead.

Under Morrison’s governorship, the state established an organization to monitor weights and measures, enacted a pure food law, and built the reform school at St. Anthony.

I was moved to write a sparse little piece about him because I ran across a blurb he had written for the October 15, 1903, edition of Leslie’s Weekly. The newspaper was quite popular for several decades, its claim to fame being the elaborate illustrations of current events included in every issue. This edition featured an Idaho mining scene on the cover. Inside was Governor Morrison’s chamber-of-commerce-esque piece, to wit:

“IDAHO INVITES attention. There is much of interest to the world within her borders. Her people are active, intelligent Americans for whom no excuse is needed and with whom one finds pleasure and profit in living. Her rich and diversified resources challenge comparison. They are quickly developed and yield ready profits. It may well be doubted if there is a State in the Union which to-day offers as inviting a field for the profitable investment of energy and industry. This fact is having wide announcement. The world is learning of the beauties and bounties of “the Gem of the Mountains.” The home-seeker and investor are attracted hither. Twenty-five thousand settlers have come to the State since January 1st, 1903, and capital knocks for admission to our mines, forests, and fields. The next ten years will witness marvelous development in Idaho.”

Who could resist?

Governor Morris and family.

Governor Morris and family.

Published on August 19, 2024 04:00

August 18, 2024

The Chilly Blue Lady

You’d be a blue lady, too, if you were a) a lady and b) hanging around a Boise street corner at midnight in January with nothing to keep you warm but a dress and a flimsy scarf.

But it wasn’t the temperature that made the blue lady blue. Ghosts are little affected by the cold, or so I’ve heard. She was blue because she was dressed in blue. Her blue dress, long hair, and flimsy white scarf were the only descriptors that come down through the pages of the Idaho Statesman from 1916.

Four Chinese men walked from Idaho to Main along Seventh Street shortly after midnight on January 2. They saw a woman in blue emerge from the alley and walk to the corner in front of a saloon. When the men reached the corner, she vanished.

And here’s where the dog enters the story. Joe Peterson’s dog lived in the neighborhood. Peterson was the Idaho attorney general at the time. The dog, a St. Bernard named Rover (can I get a rimshot?), howled whenever the blue lady appeared.

Whether his howling brought the blue lady or simply announced her presence was of some conjecture. In either case, the howling was mournful, disturbing, and a little frightening. As one does with dogs who won’t shut up, someone fed him something. This was Chinatown, so a steaming bowl of pork fried rice was handy. Rover wolfed it down.

Over the next few nights, the howling of the dog, the appearance of the blue lady, the feeding of the dog, and the disappearance of the blue lady all got rolled into a cause and effect tale that was very much to Rover’s advantage.

If the pork fried rice failed to satiate the dog, someone would add a side of noodles.

Office Day, who walked the beat in that area, investigated. He quickly found the dog and heard it howl but never saw the lady.

The Statesman sent an intrepid report to investigate the ghost sighting. Some of the men who lived in the neighborhood claimed they’d followed her nearly around the block before she vanished just as they caught up with her. Someone had apparently fed the dog.

As reported in the Statesman, the writer did not have long to wait when the midnight hour struck.

“Suddenly, old Rover, from the middle of the street, commenced a most uncanny howling.

“The reporter’s blood commenced to congeal. The wind whistled round the corner and, catching up a bit of the snow, whirled it into a ghostly figure. The reporter strained his eye for the blue skirt; he could see, he imagined, the flowing hair, the white about the neck, and—yes, the blue skirt was beginning to materialize, when—the entire ghostly form vanished as old Rover gave his lingering wail, and the Chinaman rushed from the restaurant door and hastily threw onto the sidewalk a full sized meal, even for Rover, and rushed back to the restaurant, glancing furtively over his shoulder.”

There was speculation, of course, about who the blue lady was. Some thought she might have been an apparition of one of two Chinese women who had attempted suicide in the local jail. The operative word there was “attempted.” The general consensus was that ghosts came from the dead, not those who wished to be.

The blue lady quit appearing when Peterson moved Rover to a farm out in the country where he probably never ate pork fried rice again. Was the dog in cahoots with the specter? Humm. Maybe the blue lady could have made a nice… living(?) as a dog trainer.

But it wasn’t the temperature that made the blue lady blue. Ghosts are little affected by the cold, or so I’ve heard. She was blue because she was dressed in blue. Her blue dress, long hair, and flimsy white scarf were the only descriptors that come down through the pages of the Idaho Statesman from 1916.

Four Chinese men walked from Idaho to Main along Seventh Street shortly after midnight on January 2. They saw a woman in blue emerge from the alley and walk to the corner in front of a saloon. When the men reached the corner, she vanished.

And here’s where the dog enters the story. Joe Peterson’s dog lived in the neighborhood. Peterson was the Idaho attorney general at the time. The dog, a St. Bernard named Rover (can I get a rimshot?), howled whenever the blue lady appeared.

Whether his howling brought the blue lady or simply announced her presence was of some conjecture. In either case, the howling was mournful, disturbing, and a little frightening. As one does with dogs who won’t shut up, someone fed him something. This was Chinatown, so a steaming bowl of pork fried rice was handy. Rover wolfed it down.

Over the next few nights, the howling of the dog, the appearance of the blue lady, the feeding of the dog, and the disappearance of the blue lady all got rolled into a cause and effect tale that was very much to Rover’s advantage.

If the pork fried rice failed to satiate the dog, someone would add a side of noodles.

Office Day, who walked the beat in that area, investigated. He quickly found the dog and heard it howl but never saw the lady.

The Statesman sent an intrepid report to investigate the ghost sighting. Some of the men who lived in the neighborhood claimed they’d followed her nearly around the block before she vanished just as they caught up with her. Someone had apparently fed the dog.

As reported in the Statesman, the writer did not have long to wait when the midnight hour struck.

“Suddenly, old Rover, from the middle of the street, commenced a most uncanny howling.

“The reporter’s blood commenced to congeal. The wind whistled round the corner and, catching up a bit of the snow, whirled it into a ghostly figure. The reporter strained his eye for the blue skirt; he could see, he imagined, the flowing hair, the white about the neck, and—yes, the blue skirt was beginning to materialize, when—the entire ghostly form vanished as old Rover gave his lingering wail, and the Chinaman rushed from the restaurant door and hastily threw onto the sidewalk a full sized meal, even for Rover, and rushed back to the restaurant, glancing furtively over his shoulder.”

There was speculation, of course, about who the blue lady was. Some thought she might have been an apparition of one of two Chinese women who had attempted suicide in the local jail. The operative word there was “attempted.” The general consensus was that ghosts came from the dead, not those who wished to be.

The blue lady quit appearing when Peterson moved Rover to a farm out in the country where he probably never ate pork fried rice again. Was the dog in cahoots with the specter? Humm. Maybe the blue lady could have made a nice… living(?) as a dog trainer.

Published on August 18, 2024 04:00

August 17, 2024

A Land Rush Train Crash

When I ran across this story on GenDisasters.com, it drew my attention because it was labeled as an electric train collision in Caldwell, Idaho. But, as I read the story, I found that someone was a little confused. The crash occurred at a little spot on the railroad called Gibson, just west of Coeur d’Alene. Many of the train passengers were going back and forth between Coeur d’Alene and Spokane to take part in the “Indian land opening” in 1909. That was when much of what was previously allocated to the Coeur d’Alene Tribe for their reservation was opened for homesteading. As with most land rushes, chaos commenced.

Those running the lottery for the land rush estimated that between 10 and 20 thousand people might take part. Officials in Coeur d’Alene were ecstatic, until the people started showing up like herds of bison. More than 7,000 came. There wasn’t a hotel room or even a room in a private house left to rent. Meanwhile, hoteliers in Spokane warned that Coeur d’Alene prices would be too high and encouraged rushers to stay in their city.

Fortune seekers on their way between Coeur d’Alene and Spokane to participate in the land rush packed two Spokane & Inland Railway trains on Saturday afternoon, July 31, 1909, the No. 5 eastbound and the No. 20 westbound. Why they were on the same track was for investigators to later determine, but on that afternoon the only thing that mattered was that they met head-on, each train going about 45 miles per hour.

The Twin Falls Times News covered the story in depth a few days later because a local man was one of many injured.

“It was the smoking car of the westbound train that all of the deaths occurred and most of the injured were hurt. This car was crowded to the limit, the aisle being packed with standing passengers.

“When the crash came the partition separating the motorman from the passengers was swept backward and with it the front seats. Passengers in the front of the car were thrown on top of those in the rear, while the front car of the eastbound train telescoped the smoker and smashed the seats, framework and window glass into an inextrable (sic) mass, from which the victims were extricated with difficulty.”

Sixteen died in the crash. Reports of the number injured varied from 75 to 116.

Though on the day of the crash most of the injured and dead were headed to Spokane, it was the Idaho land rush that had brought many of them to the area in the first place.

Those running the lottery for the land rush estimated that between 10 and 20 thousand people might take part. Officials in Coeur d’Alene were ecstatic, until the people started showing up like herds of bison. More than 7,000 came. There wasn’t a hotel room or even a room in a private house left to rent. Meanwhile, hoteliers in Spokane warned that Coeur d’Alene prices would be too high and encouraged rushers to stay in their city.

Fortune seekers on their way between Coeur d’Alene and Spokane to participate in the land rush packed two Spokane & Inland Railway trains on Saturday afternoon, July 31, 1909, the No. 5 eastbound and the No. 20 westbound. Why they were on the same track was for investigators to later determine, but on that afternoon the only thing that mattered was that they met head-on, each train going about 45 miles per hour.

The Twin Falls Times News covered the story in depth a few days later because a local man was one of many injured.

“It was the smoking car of the westbound train that all of the deaths occurred and most of the injured were hurt. This car was crowded to the limit, the aisle being packed with standing passengers.

“When the crash came the partition separating the motorman from the passengers was swept backward and with it the front seats. Passengers in the front of the car were thrown on top of those in the rear, while the front car of the eastbound train telescoped the smoker and smashed the seats, framework and window glass into an inextrable (sic) mass, from which the victims were extricated with difficulty.”

Sixteen died in the crash. Reports of the number injured varied from 75 to 116.

Though on the day of the crash most of the injured and dead were headed to Spokane, it was the Idaho land rush that had brought many of them to the area in the first place.

Published on August 17, 2024 04:00

August 16, 2024

Idaho Bill

Idaho Bill was a well-known character in the 1920s. While doing research on him I found a hundred or so mentions of his exploits in newspapers nationwide. One of the few states where newspapers seemed to ignore him was Idaho.

When Idaho searches turned up scant evidence of Idaho Bill, I began to wonder if his nickname had anything to do with Idaho at all.

I first ran across Col. R.B. Pearson—popularly known as Idaho Bill—in a Leslie’s Weekly from September, 1921. The gist of the article was that the Colonel was providing a service to rodeos that had recently become a necessity. Rodeos had previously found unbroken horses at about any cattle ranch nearby. But in the 1920s, ranches could no longer afford to keep horses that weren’t ready to work. So, Idaho Bill and some other entrepreneurs began gathering up broncos with bad reputations to supply to rodeos. For $600 to $1000 he would supply rodeos with 25 or 30 horses for three or four days, guaranteeing that they would buck.

The Leslie’s article, and many others I found said that Col. R.B. Pearson was born—probably without the rank—at or near Hastings, Nebraska while his folks were coming west on the Oregon Trail. That story morphed around a bit, but the upshot was that he was not born in Idaho. I found a reliable source that said he was also not born on the Oregon Trail, but in Sweden. His parents came to Nebraska when he was four.

R.B. Pearson went by Barney in his early days. His Swedish name, Bonde (pronounced boon-duh) was just not American enough. His father bought a ranch in the Weiser area and asked his son to run it.

According to many newspaper articles, Idaho Bill was a favorite Indian scout for Buffalo Bill, George Armstrong Custer, and others. How a transplanted Idahoan even met those people is open to speculation. Especially when Buffalo Bill died when Idaho Bill was eight.

Idaho Bill had a habit of roping anything that moved. Cows were no challenge for him, so he began roping wolves and coyotes. In 1921 newspapers all around the country ran a story datelined El Paso that began “A wild cinnamon bear went joy riding out San Antonio street in a claw-torn open car. Col. R.B. Pearson, bearded invader of the wilds for the last 45 years, was chauffeur for the bear.”

The story went on to say that Idaho Bill had roped the bear as a seven-month-old cub weighing 180 pounds. Speculation was that the bear would weigh 1,100 pounds when full grown.

“This is the ninth bear Colonel Pearson has roped.” The article stated. “He handled lions in Africa by the same method.”

The instinct of a carnivore to being roped and dragged is probably to try to get away by pulling, so this is… plausible?

This wasn’t the first time Idaho Bill had used his rope to impress the masses, and it wouldn’t be the last. In 1908 he roped wolves and delivered them to an exhibition in Chicago. In 1927 he delivered a 375 pound cinnamon bear to President Calvin Coolidge in Washington, DC. He was said to have capture many cougars and not a few snow leopards with his lariat.

Coolidge was not the only president to be charmed by Idaho Bill. Teddy Roosevelt is said to have befriended the Colonel. Some accounts say he visited Idaho Bill on a presidential tour of the state in 1903. Idaho papers covered that trip hour by hour without any mention of a side trip to Weiser.

Pearson acquired some wealth from his exploits, mostly from the wild west shows he produced. In 1923, while on his way to deliver broncos to a rodeo in East Las Vegas, New Mexico, Idaho bill lost his wallet in Santa Fe. He was loading the recalcitrant horses when the wallet fell out. Idaho Bill stated that there was about $40,000 in the wallet, three $10,000 bills (yes, they were in circulation at the time) and bills of lower denomination. He was offering a reward of $20,000 for the return of his wallet. No word on whether he ever got it back.

One more story about his money might have been because of that lost wallet. In 1930 the Falls City Nebraska Journal reported that Idaho Bill kept his money in his boots. He walked around with a couple of $10,000 bills and several $1,000 bills rolled up in his boots.

Idaho Bill demonstrated his “bank” for a local congressman. He pulled out a six gun along with the money as a deterrent to anyone who might be tempted to palm one of the bills he passed around for inspection.

For an in-depth article on Idaho Bill, read a story by Monty McCord in the January 2022 issue of True West Magazine.

Idaho Bill died in Los Angeles in 1942.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

When Idaho searches turned up scant evidence of Idaho Bill, I began to wonder if his nickname had anything to do with Idaho at all.

I first ran across Col. R.B. Pearson—popularly known as Idaho Bill—in a Leslie’s Weekly from September, 1921. The gist of the article was that the Colonel was providing a service to rodeos that had recently become a necessity. Rodeos had previously found unbroken horses at about any cattle ranch nearby. But in the 1920s, ranches could no longer afford to keep horses that weren’t ready to work. So, Idaho Bill and some other entrepreneurs began gathering up broncos with bad reputations to supply to rodeos. For $600 to $1000 he would supply rodeos with 25 or 30 horses for three or four days, guaranteeing that they would buck.

The Leslie’s article, and many others I found said that Col. R.B. Pearson was born—probably without the rank—at or near Hastings, Nebraska while his folks were coming west on the Oregon Trail. That story morphed around a bit, but the upshot was that he was not born in Idaho. I found a reliable source that said he was also not born on the Oregon Trail, but in Sweden. His parents came to Nebraska when he was four.

R.B. Pearson went by Barney in his early days. His Swedish name, Bonde (pronounced boon-duh) was just not American enough. His father bought a ranch in the Weiser area and asked his son to run it.

According to many newspaper articles, Idaho Bill was a favorite Indian scout for Buffalo Bill, George Armstrong Custer, and others. How a transplanted Idahoan even met those people is open to speculation. Especially when Buffalo Bill died when Idaho Bill was eight.

Idaho Bill had a habit of roping anything that moved. Cows were no challenge for him, so he began roping wolves and coyotes. In 1921 newspapers all around the country ran a story datelined El Paso that began “A wild cinnamon bear went joy riding out San Antonio street in a claw-torn open car. Col. R.B. Pearson, bearded invader of the wilds for the last 45 years, was chauffeur for the bear.”

The story went on to say that Idaho Bill had roped the bear as a seven-month-old cub weighing 180 pounds. Speculation was that the bear would weigh 1,100 pounds when full grown.

“This is the ninth bear Colonel Pearson has roped.” The article stated. “He handled lions in Africa by the same method.”

The instinct of a carnivore to being roped and dragged is probably to try to get away by pulling, so this is… plausible?

This wasn’t the first time Idaho Bill had used his rope to impress the masses, and it wouldn’t be the last. In 1908 he roped wolves and delivered them to an exhibition in Chicago. In 1927 he delivered a 375 pound cinnamon bear to President Calvin Coolidge in Washington, DC. He was said to have capture many cougars and not a few snow leopards with his lariat.

Coolidge was not the only president to be charmed by Idaho Bill. Teddy Roosevelt is said to have befriended the Colonel. Some accounts say he visited Idaho Bill on a presidential tour of the state in 1903. Idaho papers covered that trip hour by hour without any mention of a side trip to Weiser.

Pearson acquired some wealth from his exploits, mostly from the wild west shows he produced. In 1923, while on his way to deliver broncos to a rodeo in East Las Vegas, New Mexico, Idaho bill lost his wallet in Santa Fe. He was loading the recalcitrant horses when the wallet fell out. Idaho Bill stated that there was about $40,000 in the wallet, three $10,000 bills (yes, they were in circulation at the time) and bills of lower denomination. He was offering a reward of $20,000 for the return of his wallet. No word on whether he ever got it back.

One more story about his money might have been because of that lost wallet. In 1930 the Falls City Nebraska Journal reported that Idaho Bill kept his money in his boots. He walked around with a couple of $10,000 bills and several $1,000 bills rolled up in his boots.

Idaho Bill demonstrated his “bank” for a local congressman. He pulled out a six gun along with the money as a deterrent to anyone who might be tempted to palm one of the bills he passed around for inspection.

For an in-depth article on Idaho Bill, read a story by Monty McCord in the January 2022 issue of True West Magazine.

Idaho Bill died in Los Angeles in 1942.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

Published on August 16, 2024 04:00

August 15, 2024

D I V O R C E

Just can’t wait to get a divorce? Well, Idaho is one of the states where the residency requirement is short. Back in 1937, the Legislature reduced the residency requirement for obtaining a divorce in Idaho from 90 days to six weeks. Governor Chase Clark quickly signed it.

It was a blatant attempt to cash in on the quicky divorce trade Nevada was famous for. The legislation matched Nevada’s residency requirement. Representative Dan Cavanagh from Twin Falls said about his bill, “We have a chance to assist our hotels and our resorts. We should make an effort to develop these resources.”

It wasn’t so much that lawmakers thought people would flock to Burley or Weippe to establish residency for a speedy divorce. They had Sun Valley in mind. Such divorces were typically sought by the wealthy who could afford to “reside” in a state for a few weeks to take care of that messy domestic problem.

Some rich ex-lovers probably did come to Idaho, but Nevada kept the reputation for hasty divorces and weddings that could take place even faster.

Nowadays, Idaho requires a nine-week residency, or 62 days. That’s the fourth shortest time in the nation. South Dakota requires just 60 days. Nevada is still at six weeks, or 42 days. Alaska, with no residency requirement at all, tops the list.

It was a blatant attempt to cash in on the quicky divorce trade Nevada was famous for. The legislation matched Nevada’s residency requirement. Representative Dan Cavanagh from Twin Falls said about his bill, “We have a chance to assist our hotels and our resorts. We should make an effort to develop these resources.”

It wasn’t so much that lawmakers thought people would flock to Burley or Weippe to establish residency for a speedy divorce. They had Sun Valley in mind. Such divorces were typically sought by the wealthy who could afford to “reside” in a state for a few weeks to take care of that messy domestic problem.

Some rich ex-lovers probably did come to Idaho, but Nevada kept the reputation for hasty divorces and weddings that could take place even faster.

Nowadays, Idaho requires a nine-week residency, or 62 days. That’s the fourth shortest time in the nation. South Dakota requires just 60 days. Nevada is still at six weeks, or 42 days. Alaska, with no residency requirement at all, tops the list.

Published on August 15, 2024 04:00

August 14, 2024

Blame Shakespeare

Blame Shakespeare. More accurately, you should blame Shakespeare enthusiasts, particularly one Eugene Schieffelin.

Starlings. You should blame him for starlings. Folklore has it that Schieffelin introduced the birds, along with dozens of other non-native species, to bring to the United States all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare plays. The motivation may be apocryphal, but Schieffelin and others did import about a hundred pare in 1890 and 1891 to New York City’s Central Park.

It wasn’t uncommon at that time for well-meaning ornithologists to release birds they enjoyed into this new land. They had no concept of invasive species.

The first mention of starlings in the Idaho Statesman was on August 2, 1893: “Many persons have wondered why the starling got its name, which comes from an old word, meaning to look fixedly or to stare, and certainly its eyes are sharp and quick to see danger, so that it is not easily shot in the fields.”

This was clearly written during a tragic shortage of periods at the typesetting table.

The next mention of the bird in the Statesman was in 1909. The story, headlined An Unwelcome Guest, reported that “Uncle Sam” had imported a few pair of starlings to Central Park to keep insects away from fruit crops. Ironically, starlings liked the fruit as well as the insects did. The birds were becoming more common in the East than native birds. The story included another stab at the etymology of the name, attributing it to the starlike yellow spots on the bird’s dark plumage.

Beginning in 1911, the word starling in the Statesman referred most often to the Starling Hotel at 716 ½ Main Street in Boise. It was a magnet for police calls.

In 1947, the Statesman reported on the starling problem in Washington, DC. “… any pedestrian who happens to stroll beneath these trees emerges as spotted as a leopard.” Citizens debated the best way to take care of the birds. One suggested bringing in owls to eat or scare the starlings. “But what if the owl becomes an equally big menace?” the reporter asked. All right, replied the citizen. Bring in eagles to eat the owls. The article ended with the line, “Nobody has figured out yet what to do about the eagles.”

Then, in 1948, the inevitable happened. The Statesman headline read, Caldwell Reports English Starling Moving on Idaho. “Dal Whiffin of Caldwell reported Wednesday he observed a flock of English Starlings in Caldwell. This is believed to be the first report of the birds in Idaho.

“Prof. Harold Tucker of the College of Idaho confirmed Whiffin’s identification of the birds.

“Ornithologists report the starling is anti-social towards other birds and drives them from their nesting areas. The starlings particularly like to drive bluebirds away. The bluebird is the Idaho state bird.”

This propensity of starlings is one of the reasons Al Larson started the bluebird box program in Idaho.

Starlings are one of the most successful birds on the planet. They compete with native birds for nest sites and food. Their murmuration, while beautiful, confuses predators that might otherwise keep their numbers in control. That same murmuration can be a hazard to airplanes.

One other issue with this invasive species is their penchant for spreading weed seeds, particularly those of another invasive species, the Russian Olive.

Agriculturalists hate them. Studies have shown the birds can eat up to 630 pounds of cattle feed every hour.

Starlings are one of only four birds in Idaho that are not protected. The other three are English sparrows, Eurasian-collared doves, and feral pigeons.

We would have all been better off if those 19th century ornithologists had spent their time in Central Park reading sonnets.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Starlings. You should blame him for starlings. Folklore has it that Schieffelin introduced the birds, along with dozens of other non-native species, to bring to the United States all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare plays. The motivation may be apocryphal, but Schieffelin and others did import about a hundred pare in 1890 and 1891 to New York City’s Central Park.

It wasn’t uncommon at that time for well-meaning ornithologists to release birds they enjoyed into this new land. They had no concept of invasive species.

The first mention of starlings in the Idaho Statesman was on August 2, 1893: “Many persons have wondered why the starling got its name, which comes from an old word, meaning to look fixedly or to stare, and certainly its eyes are sharp and quick to see danger, so that it is not easily shot in the fields.”

This was clearly written during a tragic shortage of periods at the typesetting table.

The next mention of the bird in the Statesman was in 1909. The story, headlined An Unwelcome Guest, reported that “Uncle Sam” had imported a few pair of starlings to Central Park to keep insects away from fruit crops. Ironically, starlings liked the fruit as well as the insects did. The birds were becoming more common in the East than native birds. The story included another stab at the etymology of the name, attributing it to the starlike yellow spots on the bird’s dark plumage.

Beginning in 1911, the word starling in the Statesman referred most often to the Starling Hotel at 716 ½ Main Street in Boise. It was a magnet for police calls.

In 1947, the Statesman reported on the starling problem in Washington, DC. “… any pedestrian who happens to stroll beneath these trees emerges as spotted as a leopard.” Citizens debated the best way to take care of the birds. One suggested bringing in owls to eat or scare the starlings. “But what if the owl becomes an equally big menace?” the reporter asked. All right, replied the citizen. Bring in eagles to eat the owls. The article ended with the line, “Nobody has figured out yet what to do about the eagles.”

Then, in 1948, the inevitable happened. The Statesman headline read, Caldwell Reports English Starling Moving on Idaho. “Dal Whiffin of Caldwell reported Wednesday he observed a flock of English Starlings in Caldwell. This is believed to be the first report of the birds in Idaho.

“Prof. Harold Tucker of the College of Idaho confirmed Whiffin’s identification of the birds.

“Ornithologists report the starling is anti-social towards other birds and drives them from their nesting areas. The starlings particularly like to drive bluebirds away. The bluebird is the Idaho state bird.”

This propensity of starlings is one of the reasons Al Larson started the bluebird box program in Idaho.

Starlings are one of the most successful birds on the planet. They compete with native birds for nest sites and food. Their murmuration, while beautiful, confuses predators that might otherwise keep their numbers in control. That same murmuration can be a hazard to airplanes.

One other issue with this invasive species is their penchant for spreading weed seeds, particularly those of another invasive species, the Russian Olive.

Agriculturalists hate them. Studies have shown the birds can eat up to 630 pounds of cattle feed every hour.

Starlings are one of only four birds in Idaho that are not protected. The other three are English sparrows, Eurasian-collared doves, and feral pigeons.

We would have all been better off if those 19th century ornithologists had spent their time in Central Park reading sonnets.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Published on August 14, 2024 04:00

August 13, 2024

A Cougar Tale

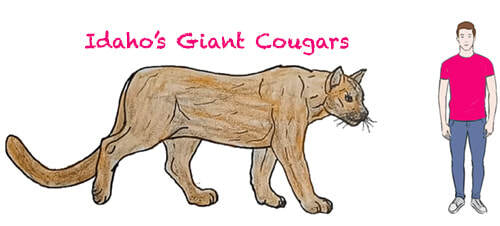

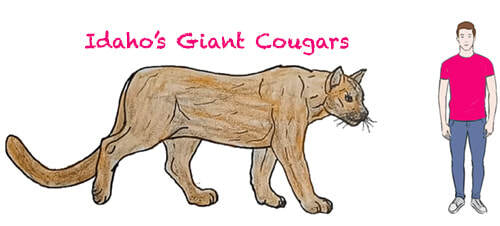

In 1943, Seaman Second Class A.P. McKinley and Specialist First Class John D. Lyons wrote to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game to settle a bet. Both sailors were stationed somewhere in the South Pacific. Lyons, who was from Idaho had bet McKinley, who was from California, that Idaho cougars could grow to 16 feet in length.

Why Governor C.F. Bottolfsen decided to jump into the argument is lost to history. He had been a newspaperman before becoming governor, so he probably relished the idea of exercising his word skills, thus:

“When you claim that only 16-foot cougars are found in Idaho you may be referring to the kittens which frolic in their dens until they attain 17 or 18 feet. I have heard of cougars that measured 20 feet from tip-of-the-nose to tip-of-the-tail, and that’s no tall tale, either.”

Uh, yeah, it was. The governor went on.

“Any smaller cougars would have a hard time for survival in our forests. A nine-foot cougar would have only an outside fighting chance against a couple of our giant jackrabbits. Mr. McKinley would not be safe if he went out with anything short of a buffalo gun, because anti-tank gun tests have shown the hide of these sturdy beasts to be as tough as an eight-inch plank.”

Not one to let a good joke lie, C.J. Westcott, president of the Idaho Wildlife Federation, also wrote to Lyons, adding, “It is evident from Mr. McKinley’s letter that he is from California, where the wildlife outside of Hollywood is not much to brag about. George Metz, who lives up Burgdorf way, shot a male cougar which measured 19 feet with its tail curled up.”

Dick d’Easum, who as a Statesman columnist had written plenty of whoppers himself, was at that time working as the Fish and Game information director. He wrote to the sailors to clear up any confusion—he was representing Fish and Game after all—telling them the biggest specimen known to have been killed in Idaho measured “about 10 feet.” And thus ended the tall… tail.

Why Governor C.F. Bottolfsen decided to jump into the argument is lost to history. He had been a newspaperman before becoming governor, so he probably relished the idea of exercising his word skills, thus:

“When you claim that only 16-foot cougars are found in Idaho you may be referring to the kittens which frolic in their dens until they attain 17 or 18 feet. I have heard of cougars that measured 20 feet from tip-of-the-nose to tip-of-the-tail, and that’s no tall tale, either.”

Uh, yeah, it was. The governor went on.

“Any smaller cougars would have a hard time for survival in our forests. A nine-foot cougar would have only an outside fighting chance against a couple of our giant jackrabbits. Mr. McKinley would not be safe if he went out with anything short of a buffalo gun, because anti-tank gun tests have shown the hide of these sturdy beasts to be as tough as an eight-inch plank.”

Not one to let a good joke lie, C.J. Westcott, president of the Idaho Wildlife Federation, also wrote to Lyons, adding, “It is evident from Mr. McKinley’s letter that he is from California, where the wildlife outside of Hollywood is not much to brag about. George Metz, who lives up Burgdorf way, shot a male cougar which measured 19 feet with its tail curled up.”

Dick d’Easum, who as a Statesman columnist had written plenty of whoppers himself, was at that time working as the Fish and Game information director. He wrote to the sailors to clear up any confusion—he was representing Fish and Game after all—telling them the biggest specimen known to have been killed in Idaho measured “about 10 feet.” And thus ended the tall… tail.

Published on August 13, 2024 04:00

August 12, 2024

Pronouncing Idaho Place Names

Publisher's note: This long post is one of the chapters from my latest book, The Idaho Conversion Kit. It is offered here free of charge in the hope that some new broadcaster will get a whiff of it and spend a few minutes learning how to pronounce Idaho's place names. You can order a copy of the book from this page, from Amazon, or you can find it in local book stores.

You’ll never be a real Idahoan until you learn how to pronounce the state’s trickiest place names. I’m listing the most challenging and most interesting names, working a pronunciation guide into the sentence in place of the name itself, occasionally, to keep repetition at a minimum.

There are hundreds of other Idaho names you might want to learn. The book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, by Lalia Boone, is probably the best single source for such research. Unfortunately, it’s no longer in print. I used Lalia’s book a lot when compiling the following list. I also used the Pronunciation Guide for the State of Idaho by William J. Ryan. Sadly, it is so rare as to be practically non-existent. It was published by the Journalism Department of Idaho State University in 1975 to help keep broadcasters from making fools of themselves.

A

Acequia The Idaho pronunciation is uh-SEEK-we-uh. Spanish language speakers would probably say a-SAKE-e-ya. It means canal or irrigation ditch in Spanish.

Ahsahka Pronounce it uh-SOCK-uh. It’s Nez Perce for “fork in the river.”

Athol. Be especially careful with this one. Named for an Indian chief, it is pronounced ATH-ul.

B

Basalt If you’re a geologist, you call that rock bu-SALT. If you live in this tiny Bingham County community, it’s pronounced BAY-salt.

Benewah Named after another Indian Chief, say BEN-u-wah.

Boise No Z. Really. One can debate why residents prefer the soft S in BOY-see, but you may as well stamp NOT FROM AROUND HERE on your forehead if you say BOY-zee.

Bruneau BROO-no is the way to say it. Why are the town, the river, the canyon, and the state park called that? Maybe it’s French for “dark water.” Maybe it was named for a trapper by that name.

C

Cassia Call it CASH-uh unless you’re French. If you’re from Paris (not the one in Idaho), you’re welcome to say ka-shee-uh. It is peasant French for “raft,” but there are other theories about where the name came from. Since the community of Raft River is in Cassia County, I’m going with that.

Cataldo Named after missionary Father Joseph Cataldo, pronounce this one kuh-TAUL-doe.

Chatcolet Often shortened to just “Chat” by the locals, say CHAT-koe-let. Some say it is Coeur d’Alene for “place where animals are trapped.” It’s in Benawah County, near Heyburn State Park.

Cocolalla Try koe-koe-LAW-luh. It means very cold in Coeur d’Alene. The name is attached to several features in Bonner County.

Coeur d’Alene Pronounce it kore-duh-LANE. Ironically, this isn’t a Coeur d’Alene word. It was given to the Tribe by French trappers. “Heart of the Awl” is the literal meaning. It is said this somehow conveyed that Tribal members were shrewd traders.

D

Desmet Named after Father Pierre Jean De Smet, you should say dee-SMET. The missionary was so popular that another Idaho town tried to appropriate the name. Postal officials didn’t want two Desmets in Idaho, arguing that could be confusing. So, the residents of that town decided to spell it backwards, Temsed. For whatever reason, when the paperwork came back, officials had changed the spelling to Tensed. That stuck.

Detrich Judge Frank S. Detrich said it was pronounced DEE-trick.

Dubois The county seat of Idaho’s least populated county, is pronounced DOO-boyss. That’s the way Senator Dubois pronounced it. Away with your doo-BWAH, I say!

Dworshak Named in honor of Senator Henry Dworshak, the dam is pronounced D-WORE-shack.

E

Egin Allegedly, the Shoshone name for “cold” is pronounced EE-jin. It’s a town in Fremont County.

Enaville EE-nuh-vill is a good way to say it. The tiny town was named after Princess Ena, the daughter of Queen Victoria and later Queen of Spain. It was a supply station in Shoshone County in the 1880s.

F

Farragut Admiral Farragut, who famously said, “Damn the torpedoes. Full speed ahead!” pronounced his name FAIR-uh-gut. This state park was a naval training station during WWII.

Fernan It’s a lake, it’s creek, it’s a ridge! And, it’s pronounced fur-NAN.

G

Gannett Unlike the newspaper company, this Blaine County community is GAN-net.

Geneva Summits of high-ranking international officials are sometimes held in the Swiss town of the same name. In Idaho, you can go to Geneva Summit by driving up a hill. Juh-NEE-vuh.

H

Hamer No, you can’t drive nails with Hamer. Not enough Ms. HAY-mur.

Hammett It has the Ms, so it’s pronounced HAM-mut.

Heise Famous for hot springs and pools, say HIGH-see.

Huetter Near Post Falls, this town name sounds like HUT-ur.

I

Idavada This might vary, depending on how you pronounce Nevada. It’s a portmanteau, or the combining of two words, in this case, the state names of Idaho and Nevada. My source says eye-duh-VAY-da.

Indianola You’ll run across this name more often in Iowa than Idaho. There, it’s a town of about 15,000. Here, it’s a Forest Service field station. You’ll find the name in other states, too. Pronounce it Indian-NO-la.

J

Jacques Don’t get all French about the name of this spot in the road. Say JACKS.

Juliaetta When Postmaster Charles Snyder decided to combine the names of his two daughters, he came up with the prettiest town name in Idaho. Say joo-lee-ETT-uh.

K

Kalispell The Montana town is better known, but Idaho has Kalispell Bay. KAL-iss-pell.

Kamiah If you’re looking for The Heart of the Monster, it’s near Kamiah, pronounced KAM-ee-eye. That monster tale is the creation story of the Nez Perce.

Kaniksu This means “black robe” in the language of the Coeur d’alenes. It refers to the missionaries who came West to tell their story. It is pronounced kun-NICK-sue.

Ketchum David Ketchum built a cabin here in 1879. When the population justified a post office someone thought Leadville would be a good name. Too many Leadvilles, postal officials said. Ketchum, KETCH-um, was the second and better choice.

Keuterville Henry Kuther wanted this little town named Kutherville. The bleary-eyed officials at the Post Office Department misread it. What they say goes. So, now we pronounce it KYOO-tur-vill.

Kimama What is it with names in Idaho that start with a K? Wrap your tongue around kuh-MY-muh. Railroad officials who named the siding thought it meant “butterfly” in some Indian language.

Kooskia This is easy to pronounce. Just leave off the last letter. KOOSS-kee. It means “where the waters join,” in the Nez Perce language. Sort of. The original word is Kooskooskia.

Kootenai KOO-tun-ay comes from the Kootenai Tribal word meaning “water people.” The Kootenai Tribe started what was probably the last war with Indians in the U.S. They declared war on the government in 1974. Not a single shot was fired, but the action got them official recognition as a Tribe, something they knew they were since forever.

Kuna This bustling community southwest of Boise is called KYOO-nuh. It was named by someone who thought it was an Indian word for “smoke. Or “snow.” Or “the end.” Or “Greenleaf.” Or something.

L

Laclede You’ll find a lot of French place names in Idaho. Luh-KLEED was named after a French engineer.

Lago LAY-go could be the Italian word for “lake” or an Indian word, the meaning of which has gone the way of so many Indian words.

Lanark Near Bear Lake, LAN-ark is named for a town in Scotland.

Lapwai Call it LAP-way. It’s from a couple of Nez Perce words, lap-lap, meaning “butterfly,” and wai meaning “stream.”

Latah LAY-taw, is the way to pronounce it. It’s allegedly a Nez Perce word meaning “the place of pine trees and pestle.” If a major part of your diet was camas roots, you might have a name like that for the place you ground those roots into flour.

Leadore Some Idaho place names are so simple that you wonder how you could mispronounce them. LED-ore is how you pronounce this one unless you pronounce it LEED-ore, which would be wrong.

Leonia A railroad worker is said to have named it for his home in Italy. Lee-OWN-ee-uh.

Lochsa This is said to be a Flathead Indian word meaning “rough water.” Indeed, the river has some. Say LOCK-saw.

M

Mackay This name famously gives newcomers fits. Pronounce it MACK-ee.

Malad Two rivers and a town have this name. It is muh-LAD after the French “malady.” A good demonstrative sentence of its meaning might be: “The trappers ate too much beaver tail, and it gave them a malady.”

McCammon Another name that came to Idaho via railroad. It, muh-KAM-un, was named after a railroad promoter.

Medimont Remember that portmanteau in the listing for Idavada? Here’s another. Medimont, MED-ih-mont is a combination of “medicine” and “mountain.” Why they didn’t just call it Medicine Mountain, as the nearby mountain is called, is a puzzle.

Menan The Menan Buttes, muh-NAN, in Southeastern Idaho are two of the largest tuff cones in the world. Tuff is a rock made up of more than 75 percent volcanic ash.

Michaud Michaud Flats, mish-ODD, is between American Falls and Pocatello. The irrigation project there goes by that name, as does a small phosphate-related Super Fund site.

Minidoka We have lost the meaning of so many Indian names. This one, min-ih-DOKE-uh, is probably Indian, but there’s a dispute over which language it came from before you even get to the dispute about what the word means. Maybe “well spring.” Maybe “broad expanse.”

Minnetonka The definition of min-ee-TONKA-uh seems more certain than many. It seems to be from the Sioux language, with minne meaning “water” and tonka meaning “big.” Minnetonka Cave is big—the biggest formation cave in Idaho. The water associated with this Bear Lake County wonder is just slow drips.

Mohler Say MOE-lur. Named for a railroad guy, this was once a small town that is now more of an area in Lewis County.

Montour The name, MAWN-toor, has hazy French roots. It once meant something like “a setting.” It’s in Gem County.

Montpelier The better-known Montpelier, mawnt-PELL-yur, is in Vermont. That’s where Brigham Young was from. He named the town in Bear Lake County.

Moscow The easy way to remember how to pronounce Moscow is to remember that there are no cows there. Wait. That doesn’t work. Still, it’s pronounced MOSS-koe. It is one of about 20 towns that carry that name in the U.S. None of them claim a relationship to the one in Russia.

Moyie You’ll find the Moyie River, Moyie Springs, and Moyie Falls near Bonners Ferry. The name, MOY-ee, came from an area in British Columbia. It may mean “wet,” or it could be a type of quartz.

N

Nampa Say NAM-puh. It probably means something like “footprint” or “big foot.” The Shoshoni word seems not to have anything to do with a sasquatch.

Nezperce Pronounce it nezz-PURSE, just like the two-word version. It means “pierced nose” in French. Trappers applied it to natives who already had a perfectly good name, Nimiipuu. The Tribe did not practice nose piercing, but the name stuck. Nezperce is the county seat of Lewis County.

Notus I’ll put you on notice that Notus is pronounced NO-tuss. What the name means is in dispute. Various stories have it as a Greek name, an Indian name, and a conjunction of Not Us. You pick.

O

Ola Names sometimes just pop up. Take Ola, OH-luh, for example. It was allegedly named for an old Swede who just happened along when they were picking a new name for the post office.

Onaway This Latah County community doesn’t have much of a backstory for its name, ON-uh-way. It was named after a town in New York.

Oneida Speaking of New York, Oneida County, oh-NYE-duh, was named for that state’s Lake Oneida. That, in turn, was named for the Oneida Indians.

Oreana With “ore” in the name, it’s a good bet mining was involved in the naming oh-ree-ANNA. But don’t take that bet. It’s a Spanish word for an “unbranded but earmarked calf.”

Orofino On the other hand, or-uh-FEEN-oh, is all about the gold. It means “fine gold” in Spanish.

Orogrande Pronounced or-uh-GRAND, this name has the same roots as Orofino. It was a popular one, being attached to a town in Custer County, another town in Idaho County, and a creek in Clearwater County.

Owyhee Aloha. Pronounce this oh-WYE-hee and notice the similarity to the way you say Hawaii. No accident. The county was named for three island natives who went looking for beaver in the mountains and never came back. Americans were calling the people of what were then known as the Sandwich Islands, Owyhees.

P

Pahsimeroi Pronouncing puh-SIMMER-eye is easier than spelling it. The river and the valley get their name from a Shoshoni word or words for “water,” “grove,” and “one.” Think “one grove of trees on the water.”

Paris You already know how to pronounce this. What you may not know is that the name of the Idaho town has nothing to do with the home of the Eifel Tower. The town was named after Fredrick Perris, the man who platted it. Why they spelled it differently is open to question. Probably those scoundrel postal officials and their persnickety pens. They were always “helping” towns get their names right.

Palouse Pronounce it puh-LOOSE, then argue about where the name came from. Pelouse, meaning “grassy” in French, seems like a good source. French trappers were terrorizing beavers and naming places for many years in what is now Idaho. A better explanation for the name is that it comes from the Sachaptin Indian name of a nearby village called, Palus. Either way, the Palouse is a rolling prairie now turned pioneer quilt with the squares of colored crops alternating, mostly in yellows and greens.

Pegram PEA-gram, located in Bear Lake County, was named for a railroad engineer.

Pend Orielle Say pond-uh-RAY, and you’ll be right. Named for an Indian Tribe that French trappers said wore earrings. That tribal description is now disputed by anthropologists. Some creative minds have pointed out that the lake—Idaho’s deepest—looks something like an ear itself. However, naming it after its shape would have required at least a helicopter, if not an orbiting satellite.

Picabo Named after Olympian Picabo Street… Sorry, no, she was named after the Blaine County town of PEEK-uh-boo. It may be an Indian word whose definition has faded away.

Pingree PING-gree was named after a developer. It's in Bingham County, about 20 minutes southwest of Blackfoot.

Plummer Say it like you were calling someone to fix your leaky sink. It’s probably named after Henry Plummer, a notorious outlaw who had a hideout nearby. The Nez Perce Tribal Headquarters is here.

Pocatello This probably tops the list of Idaho odd names, though we’re pretty used to it by now. The city, poe-kuh-TELL-oh, was named for a great Shoshoni leader. He never called himself that, but white settlers gave him the moniker for unknown reasons. One popular, though highly suspect, story is that he often came to town to pick up pork and tallow. It seems an obvious backformation meant to belittle a man who in no way deserved it.

Portneuf The river by this name, PORT-nuff, flows through Pocatello. The river and various features in the area are named after a fur trapper.

Potlatch It was a tradition among the Chinook tribes to exchange gifts at annual gatherings. POT-latch is the pronunciation of the word associated with those gatherings. It became attached to a town, a river, a creek, and a timber company.

R

Rathdrum. RATH-drum was not the first choice for the name of the town in Kootenai County that bears the name. Citizens wanted to call it Westwood. Postal officials—always trying to avoid confusion—decided there were already too many towns of that name. Residents opted for the Irish birthplace of one of their own as a second choice.

Reubens I include ROO-buns only because we’re a little short of towns in Idaho whose name begins with R. The name has an unexpected backstory. James Reubens, for whom the town is named, was a Nez Perce Indian who sided with US troops during the Nez Perce War of 1877.

S

Sagle It’s easy enough to say SAY-gull. What’s interesting about the name of this town, near Sandpoint, is how it got its name. Those pesky post office officials balked at naming the town Eagle, because there was already another town named Eagle in Idaho. It wasn’t the current town of Eagle, but it did have the first Eagle Post Office. Someone simply substituted an “S” for the first “E” in eagle. That got the needed approval from the Post Office Department.

St. Maries The name of the county seat of Benewah County, is called saint MARYS. Father Pierre-Jean De Smet named the town in honor of the Virgin Mary.

Samaria The town of suh-MARY-uh is more of an area these days. It lost its post office in 1983. Near Malad City, Samaria was named thus because residents were known as Good Samaritans.

Secesh Many minors who worked in the area in Idaho County were from the Confederate States. Because they were secessionists, they were called “Secesh Doctrinaires.” The name for the basin and the river is pronounced SEE-sesh.

Shoshone There’s a town and a waterfall by this name in Southern Idaho and a county in Northern Idaho that goes by the same name. All are named for the Shoshoni Indians. Pronounce it show-SHOWN.

Skitwish This peak in Kootenai County is pronounced just as it reads, SKIT-wish. I included it because it’s fun to say and because the name is derived from the Coeur d’Alene word Skitswish. That’s what they called their nation before French trappers started calling the Indians Coeur d’Alenes.

Tamarack The western larch is also commonly called the TAM-uh-rack. There’s a creek by that name in Clearwater County and there was an early settlement called that in Adams County. Today, it’s most prominently attached to a ski resort on Lake Cascade.

Targhee Early Idahoans loved Indian names, even though they tended to misinterpret them when they attached one to a town or feature. This is understandable since the indigenous people of the Northwest didn’t have a written language. TAR-gee is a good example. In honoring a Bannock chief, the spelling of the name morphed from Ty-gee, to Ti-ge, and finally to Targhee. The name is on a Forest, a creek, and a ski resort. The latter is in Wyoming, but Idaho often lays claim to it since you can’t get there from Wyoming.

Teton If you’re eleven, you probably snicker when you hear this word, knowing that it is French for “breast.” The Tetons, firmly in Wyoming, are clearly visible from Idaho. They have lent their name, TEE-tawn, to a county, river, and town in Idaho. The latter is called Tetonia. Pronounce that tee-TOE-nee-uh.

Tyhee This Bannock County town is on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. TIE-hee is named for a Bannock leader. His name meant “swift.”

U

Ucon This is another Idaho town that owes its name to the postal people in Washington, DC. Citizens wanted to call it Elba, but bureaucrats pointed out there was already an Elba in the Big Book of Post Offices. Don’t spend a lot of time looking for a copy. I just made that name up. As did postal officials when it came to choosing a name for YOU-con. Apparently, feeling generous, they gave residents of the little town a list of choices. Residents picked Ucon, which was something like an acronym for Union Pacific Mining Company.

V

Viola They called her VI-oh-luh. She was the first child born in the community, then became the first schoolteacher there. When her father became the first postmaster, naming the Latah County community Viola just seemed right.

W

Waha This is an Indian word that means, maybe, “beautiful” or “subterranean water.” WAAH-haw is in Nez Perce County. It was a town and is a valley and a lake.

Wapello What were they thinking when they named this little community in Bingham County? Chief wah-PELL-oh was a Fox Indian. The Tribe lived in the Midwest.

Wasatch The WAH-satch Mountain Range is mostly in Utah but stretches into the Bear Lake country. It is a Ute word for “mountain pass.”

Weippe This word, one of Idaho’s most-often mispronounced, is an Indian term for “gathering place.” Pronounce it WEE-ipe.

Weiser We’ll end with another oft-bungle name. WEE-zur is the county seat of Washington County.

You’ll never be a real Idahoan until you learn how to pronounce the state’s trickiest place names. I’m listing the most challenging and most interesting names, working a pronunciation guide into the sentence in place of the name itself, occasionally, to keep repetition at a minimum.

There are hundreds of other Idaho names you might want to learn. The book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, by Lalia Boone, is probably the best single source for such research. Unfortunately, it’s no longer in print. I used Lalia’s book a lot when compiling the following list. I also used the Pronunciation Guide for the State of Idaho by William J. Ryan. Sadly, it is so rare as to be practically non-existent. It was published by the Journalism Department of Idaho State University in 1975 to help keep broadcasters from making fools of themselves.

A

Acequia The Idaho pronunciation is uh-SEEK-we-uh. Spanish language speakers would probably say a-SAKE-e-ya. It means canal or irrigation ditch in Spanish.

Ahsahka Pronounce it uh-SOCK-uh. It’s Nez Perce for “fork in the river.”

Athol. Be especially careful with this one. Named for an Indian chief, it is pronounced ATH-ul.

B

Basalt If you’re a geologist, you call that rock bu-SALT. If you live in this tiny Bingham County community, it’s pronounced BAY-salt.

Benewah Named after another Indian Chief, say BEN-u-wah.

Boise No Z. Really. One can debate why residents prefer the soft S in BOY-see, but you may as well stamp NOT FROM AROUND HERE on your forehead if you say BOY-zee.

Bruneau BROO-no is the way to say it. Why are the town, the river, the canyon, and the state park called that? Maybe it’s French for “dark water.” Maybe it was named for a trapper by that name.

C

Cassia Call it CASH-uh unless you’re French. If you’re from Paris (not the one in Idaho), you’re welcome to say ka-shee-uh. It is peasant French for “raft,” but there are other theories about where the name came from. Since the community of Raft River is in Cassia County, I’m going with that.

Cataldo Named after missionary Father Joseph Cataldo, pronounce this one kuh-TAUL-doe.

Chatcolet Often shortened to just “Chat” by the locals, say CHAT-koe-let. Some say it is Coeur d’Alene for “place where animals are trapped.” It’s in Benawah County, near Heyburn State Park.

Cocolalla Try koe-koe-LAW-luh. It means very cold in Coeur d’Alene. The name is attached to several features in Bonner County.

Coeur d’Alene Pronounce it kore-duh-LANE. Ironically, this isn’t a Coeur d’Alene word. It was given to the Tribe by French trappers. “Heart of the Awl” is the literal meaning. It is said this somehow conveyed that Tribal members were shrewd traders.

D

Desmet Named after Father Pierre Jean De Smet, you should say dee-SMET. The missionary was so popular that another Idaho town tried to appropriate the name. Postal officials didn’t want two Desmets in Idaho, arguing that could be confusing. So, the residents of that town decided to spell it backwards, Temsed. For whatever reason, when the paperwork came back, officials had changed the spelling to Tensed. That stuck.

Detrich Judge Frank S. Detrich said it was pronounced DEE-trick.

Dubois The county seat of Idaho’s least populated county, is pronounced DOO-boyss. That’s the way Senator Dubois pronounced it. Away with your doo-BWAH, I say!

Dworshak Named in honor of Senator Henry Dworshak, the dam is pronounced D-WORE-shack.

E

Egin Allegedly, the Shoshone name for “cold” is pronounced EE-jin. It’s a town in Fremont County.

Enaville EE-nuh-vill is a good way to say it. The tiny town was named after Princess Ena, the daughter of Queen Victoria and later Queen of Spain. It was a supply station in Shoshone County in the 1880s.

F

Farragut Admiral Farragut, who famously said, “Damn the torpedoes. Full speed ahead!” pronounced his name FAIR-uh-gut. This state park was a naval training station during WWII.

Fernan It’s a lake, it’s creek, it’s a ridge! And, it’s pronounced fur-NAN.

G

Gannett Unlike the newspaper company, this Blaine County community is GAN-net.

Geneva Summits of high-ranking international officials are sometimes held in the Swiss town of the same name. In Idaho, you can go to Geneva Summit by driving up a hill. Juh-NEE-vuh.

H

Hamer No, you can’t drive nails with Hamer. Not enough Ms. HAY-mur.

Hammett It has the Ms, so it’s pronounced HAM-mut.

Heise Famous for hot springs and pools, say HIGH-see.

Huetter Near Post Falls, this town name sounds like HUT-ur.

I

Idavada This might vary, depending on how you pronounce Nevada. It’s a portmanteau, or the combining of two words, in this case, the state names of Idaho and Nevada. My source says eye-duh-VAY-da.

Indianola You’ll run across this name more often in Iowa than Idaho. There, it’s a town of about 15,000. Here, it’s a Forest Service field station. You’ll find the name in other states, too. Pronounce it Indian-NO-la.

J

Jacques Don’t get all French about the name of this spot in the road. Say JACKS.

Juliaetta When Postmaster Charles Snyder decided to combine the names of his two daughters, he came up with the prettiest town name in Idaho. Say joo-lee-ETT-uh.

K

Kalispell The Montana town is better known, but Idaho has Kalispell Bay. KAL-iss-pell.

Kamiah If you’re looking for The Heart of the Monster, it’s near Kamiah, pronounced KAM-ee-eye. That monster tale is the creation story of the Nez Perce.

Kaniksu This means “black robe” in the language of the Coeur d’alenes. It refers to the missionaries who came West to tell their story. It is pronounced kun-NICK-sue.

Ketchum David Ketchum built a cabin here in 1879. When the population justified a post office someone thought Leadville would be a good name. Too many Leadvilles, postal officials said. Ketchum, KETCH-um, was the second and better choice.

Keuterville Henry Kuther wanted this little town named Kutherville. The bleary-eyed officials at the Post Office Department misread it. What they say goes. So, now we pronounce it KYOO-tur-vill.

Kimama What is it with names in Idaho that start with a K? Wrap your tongue around kuh-MY-muh. Railroad officials who named the siding thought it meant “butterfly” in some Indian language.

Kooskia This is easy to pronounce. Just leave off the last letter. KOOSS-kee. It means “where the waters join,” in the Nez Perce language. Sort of. The original word is Kooskooskia.

Kootenai KOO-tun-ay comes from the Kootenai Tribal word meaning “water people.” The Kootenai Tribe started what was probably the last war with Indians in the U.S. They declared war on the government in 1974. Not a single shot was fired, but the action got them official recognition as a Tribe, something they knew they were since forever.

Kuna This bustling community southwest of Boise is called KYOO-nuh. It was named by someone who thought it was an Indian word for “smoke. Or “snow.” Or “the end.” Or “Greenleaf.” Or something.

L

Laclede You’ll find a lot of French place names in Idaho. Luh-KLEED was named after a French engineer.

Lago LAY-go could be the Italian word for “lake” or an Indian word, the meaning of which has gone the way of so many Indian words.

Lanark Near Bear Lake, LAN-ark is named for a town in Scotland.

Lapwai Call it LAP-way. It’s from a couple of Nez Perce words, lap-lap, meaning “butterfly,” and wai meaning “stream.”

Latah LAY-taw, is the way to pronounce it. It’s allegedly a Nez Perce word meaning “the place of pine trees and pestle.” If a major part of your diet was camas roots, you might have a name like that for the place you ground those roots into flour.

Leadore Some Idaho place names are so simple that you wonder how you could mispronounce them. LED-ore is how you pronounce this one unless you pronounce it LEED-ore, which would be wrong.

Leonia A railroad worker is said to have named it for his home in Italy. Lee-OWN-ee-uh.

Lochsa This is said to be a Flathead Indian word meaning “rough water.” Indeed, the river has some. Say LOCK-saw.

M

Mackay This name famously gives newcomers fits. Pronounce it MACK-ee.

Malad Two rivers and a town have this name. It is muh-LAD after the French “malady.” A good demonstrative sentence of its meaning might be: “The trappers ate too much beaver tail, and it gave them a malady.”

McCammon Another name that came to Idaho via railroad. It, muh-KAM-un, was named after a railroad promoter.

Medimont Remember that portmanteau in the listing for Idavada? Here’s another. Medimont, MED-ih-mont is a combination of “medicine” and “mountain.” Why they didn’t just call it Medicine Mountain, as the nearby mountain is called, is a puzzle.

Menan The Menan Buttes, muh-NAN, in Southeastern Idaho are two of the largest tuff cones in the world. Tuff is a rock made up of more than 75 percent volcanic ash.

Michaud Michaud Flats, mish-ODD, is between American Falls and Pocatello. The irrigation project there goes by that name, as does a small phosphate-related Super Fund site.

Minidoka We have lost the meaning of so many Indian names. This one, min-ih-DOKE-uh, is probably Indian, but there’s a dispute over which language it came from before you even get to the dispute about what the word means. Maybe “well spring.” Maybe “broad expanse.”

Minnetonka The definition of min-ee-TONKA-uh seems more certain than many. It seems to be from the Sioux language, with minne meaning “water” and tonka meaning “big.” Minnetonka Cave is big—the biggest formation cave in Idaho. The water associated with this Bear Lake County wonder is just slow drips.

Mohler Say MOE-lur. Named for a railroad guy, this was once a small town that is now more of an area in Lewis County.

Montour The name, MAWN-toor, has hazy French roots. It once meant something like “a setting.” It’s in Gem County.

Montpelier The better-known Montpelier, mawnt-PELL-yur, is in Vermont. That’s where Brigham Young was from. He named the town in Bear Lake County.