Rick Just's Blog, page 10

October 1, 2024

Comet, Idaho

Halley’s Comet was visible in the sky for just a few weeks in 1910. Its namesake (probably), Comet, Idaho, didn’t last much longer.

Not every place that had a post office was an actual town. My own family ran the Presto, Idaho, post office for 14 years from their isolated home along the Blackfoot River. It seems that the Comet Post Office had a similar, shorter history.

A reader asked if I knew anything about the town of Comet. I didn’t, partly because it wasn’t really a town. Partly because I’d never heard of the place. I found that there was a post office at Comet so that made researching it much easier. I just asked Bob.

Bob Omberg is the acknowledged expert on Idaho post offices. An attorney by trade, Bob no longer lives in Idaho, but he retains a fascination with post offices, postal marks, route maps, and such. He supplied me with some information about Comet, including a copied page from "Sagebrush Post Offices: A History of the Owyhee Country" by Mildretta Adams (copyright 1986; third printing 2003 by the Owyhee Publishing CO., Homedale Idaho).

From that book, I learned that John McVann, a local rancher, established the Comet Post Office on February 7, 1910, in Owyhee County. It was near present-day Bruneau, on the south side of the Snake River across from where Canyon Creek enters. The post office operated until January 31, 1913.

Comet is listed as one of the “drowned towns” in The Atlas of Drowned Towns, BSU Professor Bob Reinhart’s project that helps identify the many places that once existed on dry land but are now under reservoir waters.

So, was Comet a town? Probably not, but the post office site is now under the C.J. Strike Reservoir, so it does qualify as drowned.

A letter postmarked from Comet, Idaho, courtesy of the the Bob Omberg collection.

A letter postmarked from Comet, Idaho, courtesy of the the Bob Omberg collection.

Not every place that had a post office was an actual town. My own family ran the Presto, Idaho, post office for 14 years from their isolated home along the Blackfoot River. It seems that the Comet Post Office had a similar, shorter history.

A reader asked if I knew anything about the town of Comet. I didn’t, partly because it wasn’t really a town. Partly because I’d never heard of the place. I found that there was a post office at Comet so that made researching it much easier. I just asked Bob.

Bob Omberg is the acknowledged expert on Idaho post offices. An attorney by trade, Bob no longer lives in Idaho, but he retains a fascination with post offices, postal marks, route maps, and such. He supplied me with some information about Comet, including a copied page from "Sagebrush Post Offices: A History of the Owyhee Country" by Mildretta Adams (copyright 1986; third printing 2003 by the Owyhee Publishing CO., Homedale Idaho).

From that book, I learned that John McVann, a local rancher, established the Comet Post Office on February 7, 1910, in Owyhee County. It was near present-day Bruneau, on the south side of the Snake River across from where Canyon Creek enters. The post office operated until January 31, 1913.

Comet is listed as one of the “drowned towns” in The Atlas of Drowned Towns, BSU Professor Bob Reinhart’s project that helps identify the many places that once existed on dry land but are now under reservoir waters.

So, was Comet a town? Probably not, but the post office site is now under the C.J. Strike Reservoir, so it does qualify as drowned.

A letter postmarked from Comet, Idaho, courtesy of the the Bob Omberg collection.

A letter postmarked from Comet, Idaho, courtesy of the the Bob Omberg collection.

Published on October 01, 2024 04:00

September 30, 2024

The Adams Family in Idaho

Charles Francis Adams Jr. was the grandson of President John Q. Adams and the Great Grandson of our second president, John Adams. In 1887, Charles Adams Jr. was the president of Union Pacific Railroad. He got to know Idaho well in that role and once said, “I regard Idaho as the most promising field of development.”

He put his money behind that statement in 1896, when he and other investors started the Lewiston Water & Power Company. Those same entrepreneurs developed property just across the Snake River in Washington State into something called Vineland. Vines soon grew there as vineyard began to produce grapes. Family farms and orchards soon came along. The company platted a town close by, calling it Concord after the city in Massachusetts where Adams had property.

But it was Adams himself that proposed changing the community’s name to Clarkston, seeing the symmetry in honoring the leaders from the Corps of Discovery with towns named for them on each side of the river. Adams joined the communities by building the first bridge between them across the Snake.

Adams was a towering figure in the two towns. His sons, Henry and John, moved to Lewiston in 1899. On 450 acres their father had purchased, they built a large home with a private polo field and views of the Snake River. John didn’t stay long in Lewiston, but Henry lived there for years overlooking his family’s business interests, which included the Adams building on Main Street.

My source for this story is a book I highly recommend, Inventing Idaho, by Keith C. Peterson. It was published by Washington State University Press in 2022.

Captain Charles Francis Adams Jr (in the rocking chair) with officers of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, August 1864. He would later become the head of Union Pacific Railroad and spark developments in Lewiston, Idaho and Clarkston, Washington.

Captain Charles Francis Adams Jr (in the rocking chair) with officers of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, August 1864. He would later become the head of Union Pacific Railroad and spark developments in Lewiston, Idaho and Clarkston, Washington.

He put his money behind that statement in 1896, when he and other investors started the Lewiston Water & Power Company. Those same entrepreneurs developed property just across the Snake River in Washington State into something called Vineland. Vines soon grew there as vineyard began to produce grapes. Family farms and orchards soon came along. The company platted a town close by, calling it Concord after the city in Massachusetts where Adams had property.

But it was Adams himself that proposed changing the community’s name to Clarkston, seeing the symmetry in honoring the leaders from the Corps of Discovery with towns named for them on each side of the river. Adams joined the communities by building the first bridge between them across the Snake.

Adams was a towering figure in the two towns. His sons, Henry and John, moved to Lewiston in 1899. On 450 acres their father had purchased, they built a large home with a private polo field and views of the Snake River. John didn’t stay long in Lewiston, but Henry lived there for years overlooking his family’s business interests, which included the Adams building on Main Street.

My source for this story is a book I highly recommend, Inventing Idaho, by Keith C. Peterson. It was published by Washington State University Press in 2022.

Captain Charles Francis Adams Jr (in the rocking chair) with officers of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, August 1864. He would later become the head of Union Pacific Railroad and spark developments in Lewiston, Idaho and Clarkston, Washington.

Captain Charles Francis Adams Jr (in the rocking chair) with officers of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, August 1864. He would later become the head of Union Pacific Railroad and spark developments in Lewiston, Idaho and Clarkston, Washington.

Published on September 30, 2024 04:00

September 29, 2024

A Dubious Clip

For your entertainment, today, a dubious clip from the Elk City News, 1908.

Few people in town on the prairie had seen an automobile until this summer, so when one of the “red devils” stopped for a few minutes in Elk City, the curious inhabitants gazed at the snorting demon with a mixture of fear and awe, and the owner who had entered the one general store to make a purchase, heard one rustic remark; “I’ll bet it’s a mankiller.” “O’course it is,” assured the other. “Look at that number on the back of the car. That shows how many people its run over. That’s accordin’ to law. Now if that feller was to run over anybody here it would be our duty to telephone that number—1284—to the next town ahead.” “And what would they do?” demanded the interested auditors. “Why the police would stop him and change his number to 1285.”

Few people in town on the prairie had seen an automobile until this summer, so when one of the “red devils” stopped for a few minutes in Elk City, the curious inhabitants gazed at the snorting demon with a mixture of fear and awe, and the owner who had entered the one general store to make a purchase, heard one rustic remark; “I’ll bet it’s a mankiller.” “O’course it is,” assured the other. “Look at that number on the back of the car. That shows how many people its run over. That’s accordin’ to law. Now if that feller was to run over anybody here it would be our duty to telephone that number—1284—to the next town ahead.” “And what would they do?” demanded the interested auditors. “Why the police would stop him and change his number to 1285.”

Published on September 29, 2024 04:00

September 28, 2024

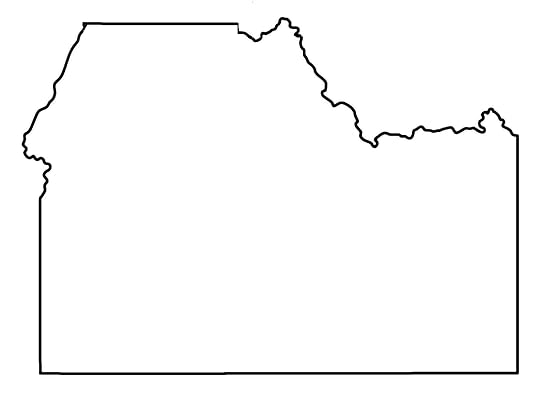

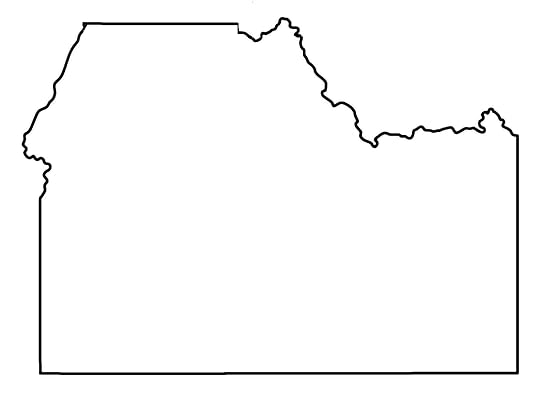

Idaho Foreshortened

Idaho’s boundaries changed over the years before statehood with little say from Idaho residents. In 1881, some residents tried to have their say.

The Territorial House of Representatives sent a memorial to Congress asking that they lop off the northern part of the territory and give it to Washington Territory. Why?

In the words of the memorial, “That all that portion of said territory embraced and included within the boundaries hereinafter set forth and constituting what is known as north Idaho, is so situated in relation to the south and southeast portion of the territory, as to render their political union impracticable for the reason that nature has divided them by a high and rugged range of mountains over which there is no road except as what will admit of passage of riding or pack animal, and this only for about six months of the year. The remaining six months the snow is so deep as to cut off all communication except by telegraph or circuitous route through Washington territory, a distance of about 500 miles.”

That sentiment echoed down through the years, when In 1970, during his first successful run for governor, Cecil D. Andrus famously called Highway 95 a “goat trail.”

The 1881 memorial went on: “Politically, the two sections are united; socially, commercially and geographically, they never can be. We therefore respectfully but urgently pray that when the territory of Washington is admitted into the union that all that portion of Idaho hereinafter described be attached and made a part of the state of Washington.”

The vote was 15 to 8 in favor of the memorial. As is often the case with such missives sent by territories or states, Congress ignored it.

The Territorial House of Representatives sent a memorial to Congress asking that they lop off the northern part of the territory and give it to Washington Territory. Why?

In the words of the memorial, “That all that portion of said territory embraced and included within the boundaries hereinafter set forth and constituting what is known as north Idaho, is so situated in relation to the south and southeast portion of the territory, as to render their political union impracticable for the reason that nature has divided them by a high and rugged range of mountains over which there is no road except as what will admit of passage of riding or pack animal, and this only for about six months of the year. The remaining six months the snow is so deep as to cut off all communication except by telegraph or circuitous route through Washington territory, a distance of about 500 miles.”

That sentiment echoed down through the years, when In 1970, during his first successful run for governor, Cecil D. Andrus famously called Highway 95 a “goat trail.”

The 1881 memorial went on: “Politically, the two sections are united; socially, commercially and geographically, they never can be. We therefore respectfully but urgently pray that when the territory of Washington is admitted into the union that all that portion of Idaho hereinafter described be attached and made a part of the state of Washington.”

The vote was 15 to 8 in favor of the memorial. As is often the case with such missives sent by territories or states, Congress ignored it.

Published on September 28, 2024 04:00

September 27, 2024

An Idaho City Shoot-out

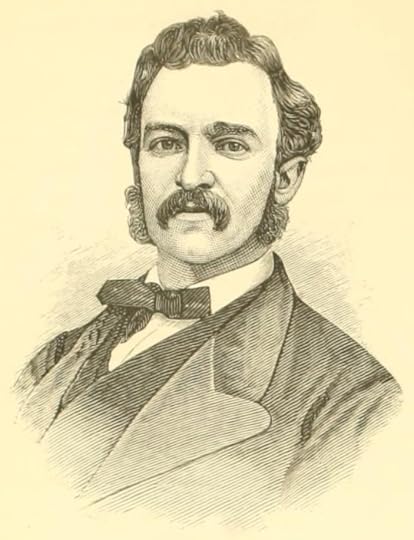

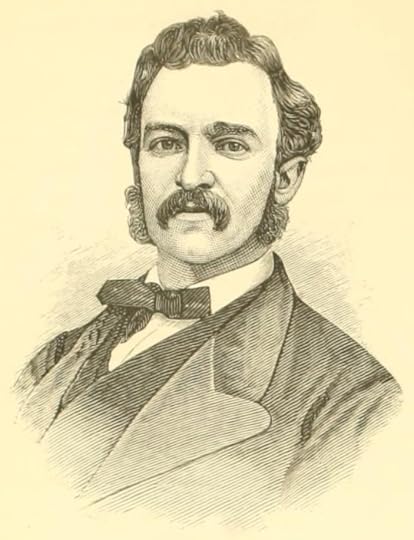

In territorial days, one could make a mark swiftly. E.D. Holbrook was a shooting star in the sense that he gained fame and power in short order before his light blinked out.

Holbrook was born in Ohio. He went to school at Oberlin, earning a Bachelor of Law degree. He was admitted to the bar there in Ohio 1859, at age 23. He came to Idaho Territory shortly thereafter to practice law in Idaho City. In 1864, the Democrat was elected by his fellows to serve as a Territorial Delegate to Congress.

Territorial delegates didn’t wield a lot of power, but Holbrook kept his eyes on the needs of Idaho Territory. He was reelected in 1866.

It will not surprise readers that a politician wasn’t universally loved. In his case, E.D. Holbrook went from great admiration from one man to pure loathing.

Charles H. Douglas, Esq. had been a friend of Holbrook’s for years, but in 1870, during the Democratic Convention in Boise, the two parted ways. Holbrook was well-impressed with himself and often spouted his opinions loudly. Douglas advised the delegate to “pull in his horns” during an argument about how delegates should be selected, and the feud was on.

Douglas had some handbills printed that called Holbrook a thief and a rascal who was unfit to represent the territory. Delegate Holbrook had handbills printed that called Douglas a liar, a coward, and an assassin.

Why Holbrook used the word “assassin” to describe his former friend is unclear. What is clear is that there was an element of prescience in its use.

On June 18, 1870, at about 8 in the evening, the two men confronted each other on the corner of Main and Wall streets in Idaho City. They first exchanged words, then gunfire. Eleven shots flew between the men. Only one hit a mark. Holbrook suffered an abdominal wound.

Deputy Sheriff T.M. Britten promptly arrested both men. Seeing that Holbrook was wounded, the deputy assisted him to his law office, just 15 feet away, and sat him down in a chair.

Britten called for Doctor Healey, who arrived promptly. The doctor examined Holbrook and found that the bullet had entered the delegate's abdomen low and to the right. With internal bleeding evident, it was a hopeless case. Holbrook died at 7 o’clock the next morning.

Monday morning, the coroner called an inquest. The jurors’ verdict was that Holbrook had died at the hands of Douglas.

Meanwhile, Holbrook’s coffin lay in state at the Masonic Temple, but not for long. About 200 citizens participated in a funeral march led by a brass band to the cemetery that afternoon. The coroner, who happened to be the grand master of the Masonic fraternity in Idaho, took charge of the burial ritual.

Douglas pleaded self-defense. He was acquitted on the grounds that both parties entered into the altercation willingly.

Whether it was justice or not, it was swift, as was just about everything related to the shooting star life of E.D. Holbrook.

Edward Dexter Holbrook was one of Idaho Territory's first delegates to Congress.

Edward Dexter Holbrook was one of Idaho Territory's first delegates to Congress.

Holbrook was born in Ohio. He went to school at Oberlin, earning a Bachelor of Law degree. He was admitted to the bar there in Ohio 1859, at age 23. He came to Idaho Territory shortly thereafter to practice law in Idaho City. In 1864, the Democrat was elected by his fellows to serve as a Territorial Delegate to Congress.

Territorial delegates didn’t wield a lot of power, but Holbrook kept his eyes on the needs of Idaho Territory. He was reelected in 1866.

It will not surprise readers that a politician wasn’t universally loved. In his case, E.D. Holbrook went from great admiration from one man to pure loathing.

Charles H. Douglas, Esq. had been a friend of Holbrook’s for years, but in 1870, during the Democratic Convention in Boise, the two parted ways. Holbrook was well-impressed with himself and often spouted his opinions loudly. Douglas advised the delegate to “pull in his horns” during an argument about how delegates should be selected, and the feud was on.

Douglas had some handbills printed that called Holbrook a thief and a rascal who was unfit to represent the territory. Delegate Holbrook had handbills printed that called Douglas a liar, a coward, and an assassin.

Why Holbrook used the word “assassin” to describe his former friend is unclear. What is clear is that there was an element of prescience in its use.

On June 18, 1870, at about 8 in the evening, the two men confronted each other on the corner of Main and Wall streets in Idaho City. They first exchanged words, then gunfire. Eleven shots flew between the men. Only one hit a mark. Holbrook suffered an abdominal wound.

Deputy Sheriff T.M. Britten promptly arrested both men. Seeing that Holbrook was wounded, the deputy assisted him to his law office, just 15 feet away, and sat him down in a chair.

Britten called for Doctor Healey, who arrived promptly. The doctor examined Holbrook and found that the bullet had entered the delegate's abdomen low and to the right. With internal bleeding evident, it was a hopeless case. Holbrook died at 7 o’clock the next morning.

Monday morning, the coroner called an inquest. The jurors’ verdict was that Holbrook had died at the hands of Douglas.

Meanwhile, Holbrook’s coffin lay in state at the Masonic Temple, but not for long. About 200 citizens participated in a funeral march led by a brass band to the cemetery that afternoon. The coroner, who happened to be the grand master of the Masonic fraternity in Idaho, took charge of the burial ritual.

Douglas pleaded self-defense. He was acquitted on the grounds that both parties entered into the altercation willingly.

Whether it was justice or not, it was swift, as was just about everything related to the shooting star life of E.D. Holbrook.

Edward Dexter Holbrook was one of Idaho Territory's first delegates to Congress.

Edward Dexter Holbrook was one of Idaho Territory's first delegates to Congress.

Published on September 27, 2024 04:00

September 26, 2024

WASP Pilot Instructors in Pocatello

I’ve written before about the Aztec Eagles, the Mexican Air Force unit that trained during World War II in Pocatello. I didn’t mention how surprised the men who were learning how to fly were when they met their instructors. Some of the instructors were women.

It was a woman, Jacqueline Cochran, who formed the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Cochran was a business executive and a pilot. In 1953 she became the first woman to break the sound barrier.

But it was in 1939 that Cochran broke a more persistent barrier when she wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt suggesting that women pilots could fill in for male pilots who went to combat. Her vision was to have the WASP pilots shuttle planes from place to place in the US as needed. It took her until 1943 to sell all the right people on the idea.

Cochran headed the new WASP. She sent out a call for women pilots that resulted in more than 25,000 applications. Initially, only those women between the ages of 21 and 35 and who had 200 flying hours under their belts could apply.

Jacqueline Cochran interviewed every applicant, picking 1,830 of them for training at the Avenger Field Flight School in Sweetwater, Texas. Not everyone who trained made the cut. Over the life of the program, 1,074 women became WASP pilots, serving at 126 bases across the country, including the base in Pocatello, Idaho, where they helped beef up the Mexican Air Force.

If you’d like to learn more about the Mexican Expeditionary Air Force (though little about their training in Pocatello), check out this video.

Another short clip that includes some comments about the WASPs in Pocatello can be found here. Four members of the United States Women's Airforce Service Pilots. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Four members of the United States Women's Airforce Service Pilots. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.  Jacqueline Cochran in the cockpit of a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk.

Jacqueline Cochran in the cockpit of a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk.

It was a woman, Jacqueline Cochran, who formed the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Cochran was a business executive and a pilot. In 1953 she became the first woman to break the sound barrier.

But it was in 1939 that Cochran broke a more persistent barrier when she wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt suggesting that women pilots could fill in for male pilots who went to combat. Her vision was to have the WASP pilots shuttle planes from place to place in the US as needed. It took her until 1943 to sell all the right people on the idea.

Cochran headed the new WASP. She sent out a call for women pilots that resulted in more than 25,000 applications. Initially, only those women between the ages of 21 and 35 and who had 200 flying hours under their belts could apply.

Jacqueline Cochran interviewed every applicant, picking 1,830 of them for training at the Avenger Field Flight School in Sweetwater, Texas. Not everyone who trained made the cut. Over the life of the program, 1,074 women became WASP pilots, serving at 126 bases across the country, including the base in Pocatello, Idaho, where they helped beef up the Mexican Air Force.

If you’d like to learn more about the Mexican Expeditionary Air Force (though little about their training in Pocatello), check out this video.

Another short clip that includes some comments about the WASPs in Pocatello can be found here.

Four members of the United States Women's Airforce Service Pilots. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Four members of the United States Women's Airforce Service Pilots. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.  Jacqueline Cochran in the cockpit of a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk.

Jacqueline Cochran in the cockpit of a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk.

Published on September 26, 2024 04:00

September 25, 2024

The Fort Hall CCCs

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a storied program of FDR’s New Deal. Idaho embraced the program perhaps more than any other state, getting the largest number of CCC camps per population in the country. The total number of camps in Idaho, 270, was second only to California.

Less well-known was the impact of a parallel program called CCC-ID. In this case, the ID didn’t stand for Idaho but for Indian.

Records show that 80,000 to 85,000 men served in the CCC-ID. One remarkable feature of the program was that it was run mainly by the Tribes. They selected the men from their reservations who would participate. Those men learned animal husbandry, gardening, road building, conservation work, and academic subjects. Most of the work they did was on their home reservations.

Nationwide the CCC-ID men laid out almost 9,800 miles of truck trails, controlled pests on 1,351,870 acres, eradicated weeds on 263,129 acres, and built 1,792 dams and reservoirs. Those efforts were similar to the CCCs, but the Indian branch also focused on teaching native skills and arts.

The men receive $30 a month for working 20 days. Some were paid from $1 to $2 a day for the use of their teams of horses. If they took advantage of all the pay opportunities of the program, they could make up to $42 a month. The regular CCC men made at most $30.

One of the most important outcomes of the CCC-ID was that the program showed that Native Americans could succeed under their own tribal management.

Both the CCC and CCC-ID were disbanded in the early 1940s as the nation turned its attention to WWII. A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.

A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.  Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.

Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.  Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Less well-known was the impact of a parallel program called CCC-ID. In this case, the ID didn’t stand for Idaho but for Indian.

Records show that 80,000 to 85,000 men served in the CCC-ID. One remarkable feature of the program was that it was run mainly by the Tribes. They selected the men from their reservations who would participate. Those men learned animal husbandry, gardening, road building, conservation work, and academic subjects. Most of the work they did was on their home reservations.

Nationwide the CCC-ID men laid out almost 9,800 miles of truck trails, controlled pests on 1,351,870 acres, eradicated weeds on 263,129 acres, and built 1,792 dams and reservoirs. Those efforts were similar to the CCCs, but the Indian branch also focused on teaching native skills and arts.

The men receive $30 a month for working 20 days. Some were paid from $1 to $2 a day for the use of their teams of horses. If they took advantage of all the pay opportunities of the program, they could make up to $42 a month. The regular CCC men made at most $30.

One of the most important outcomes of the CCC-ID was that the program showed that Native Americans could succeed under their own tribal management.

Both the CCC and CCC-ID were disbanded in the early 1940s as the nation turned its attention to WWII.

A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.

A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.  Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.

Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.  Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Published on September 25, 2024 04:00

September 24, 2024

The UP Student Special

I was reading Keith Peterson's book, Inventing Idah when I wrote this post. It tells the story of how Idaho got its eccentric shape. It’s not just about decisions—made mostly by people who had never been here—but about the impact of the decisions on our history, which resonates even today when there is another move afoot to tweak the borders.

One result of Idaho’s shape is that we ended up with our first university in North Idaho, while most of the state’s population lived in Southern Idaho. For decades getting to Moscow from Boise, Pocatello, or Bear Lake meant taking the easier route, traveling outside the state.

Southern Idaho students wanted to take advantage of their own state school, so before World War I, University of Idaho Officials teamed up with officials from Union Pacific Railroad to create a Student Special. The train’s starting point was Pocatello. From there, the well-outfitted train—passenger coaches, baggage cars, sleeper cars, and a dining car—made stops at American Falls, Shoshone, Gooding, Bliss, Glenns Ferry, Mountain Home, Nampa, Caldwell, and Parma. Boise, Idaho Falls, and Twin Falls students took spur lines to catch the train.

The Student Special took students to Moscow in the fall and back home again in the spring. There was also a Student Special that made visiting home at Christmas possible.

The in-state students got rolling views of Oregon and Washington on their trip, some of them traveling nearly 700 miles to get to Moscow. Many states employed special trains to carry students to university. Idaho had the distinction of having the longest route.

The Student Special operated until after World War II.

I highly recommend Peterson’s book. It’s available at local bookstores or from WSU Press. Arrival of Student Special train from southern Idaho, in 1922. University of Idaho Student Organizations Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library.

Arrival of Student Special train from southern Idaho, in 1922. University of Idaho Student Organizations Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library.

One result of Idaho’s shape is that we ended up with our first university in North Idaho, while most of the state’s population lived in Southern Idaho. For decades getting to Moscow from Boise, Pocatello, or Bear Lake meant taking the easier route, traveling outside the state.

Southern Idaho students wanted to take advantage of their own state school, so before World War I, University of Idaho Officials teamed up with officials from Union Pacific Railroad to create a Student Special. The train’s starting point was Pocatello. From there, the well-outfitted train—passenger coaches, baggage cars, sleeper cars, and a dining car—made stops at American Falls, Shoshone, Gooding, Bliss, Glenns Ferry, Mountain Home, Nampa, Caldwell, and Parma. Boise, Idaho Falls, and Twin Falls students took spur lines to catch the train.

The Student Special took students to Moscow in the fall and back home again in the spring. There was also a Student Special that made visiting home at Christmas possible.

The in-state students got rolling views of Oregon and Washington on their trip, some of them traveling nearly 700 miles to get to Moscow. Many states employed special trains to carry students to university. Idaho had the distinction of having the longest route.

The Student Special operated until after World War II.

I highly recommend Peterson’s book. It’s available at local bookstores or from WSU Press.

Arrival of Student Special train from southern Idaho, in 1922. University of Idaho Student Organizations Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library.

Arrival of Student Special train from southern Idaho, in 1922. University of Idaho Student Organizations Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library.

Published on September 24, 2024 04:00

September 23, 2024

The Potato Peeler

Ross C. Bales, a B17 pilot who had two planes -- one called the Idaho Potato Peeler and the second called FDR's Potato Peeler Kids. Here are some links if you want to read about them...

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56296493/ross-cartee-bales?fbclid=IwAR3FIYk8X1sEnWHdPRUSAi4x0MNIh8_Ek70FV4xM5EaqwoozulXovMVBNVY

http://www.303rdbg.com/c-359-bales.html?fbclid=IwAR2oA7SXoWGR9LViLDvbmN46V3XhDf8OR2ZfriLmoxHO4zsuzuuArof9NmU

During World War II, local papers were hard-pressed to list the names of the local combatants who were promoted, received medals, were missing, or were killed in action. I found only two tiny mentions of Captain Ross C. Bales in the Idaho Statesman before they began reporting him missing, then KIA.

Ross Bales, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Bales of Caldwell, trained for three months at Gowen Field in Boise before heading overseas. Bales never forgot his home state, naming the first bomber he piloted the “Idaho Potato Peeler.”

The B17F with the Idaho name completed 21 combat missions with Bales at the helm. Returning from a bombing run on January 23, 1943, Bales had to make an emergency, wheels-up, landing, sliding the plane onto the runway at Chipping Warden, England. None of the crew were hurt, but the plane was too badly damaged to get back into service right away.

Captain Bales took the stick of another B17F. He carried his naming tradition forward with one important twist. The new plane became “FDR’s Potato Peeler Kids.”

The Caldwell native flew the second Potato Peeler on 13 more combat missions before crashing into the North Sea. The plan was last seen going down in a spin. Several parachutes popped, but no survivors were recovered.

Captain Ross C. Bales is memorialized on the Wall of the Missing in the Netherlands.

The original Potato Peeler and crew. After Captain Bales performed and emergency, wheels-up, landing, it was badly damaged. The crew moved to the new plane, but the Potato Peeler was repaired. It went on to complete an additional 22 combat missions before being shot down on November 5, 1943. One crew member died; nine were POWs.

The original Potato Peeler and crew. After Captain Bales performed and emergency, wheels-up, landing, it was badly damaged. The crew moved to the new plane, but the Potato Peeler was repaired. It went on to complete an additional 22 combat missions before being shot down on November 5, 1943. One crew member died; nine were POWs.  BALE'S CREW, FDR Potato Peeler Kids. Captain Ross C. Bales is standing in the back on the left. This was the plane that went down in the North Sea.

BALE'S CREW, FDR Potato Peeler Kids. Captain Ross C. Bales is standing in the back on the left. This was the plane that went down in the North Sea.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56296493/ross-cartee-bales?fbclid=IwAR3FIYk8X1sEnWHdPRUSAi4x0MNIh8_Ek70FV4xM5EaqwoozulXovMVBNVY

http://www.303rdbg.com/c-359-bales.html?fbclid=IwAR2oA7SXoWGR9LViLDvbmN46V3XhDf8OR2ZfriLmoxHO4zsuzuuArof9NmU

During World War II, local papers were hard-pressed to list the names of the local combatants who were promoted, received medals, were missing, or were killed in action. I found only two tiny mentions of Captain Ross C. Bales in the Idaho Statesman before they began reporting him missing, then KIA.

Ross Bales, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Bales of Caldwell, trained for three months at Gowen Field in Boise before heading overseas. Bales never forgot his home state, naming the first bomber he piloted the “Idaho Potato Peeler.”

The B17F with the Idaho name completed 21 combat missions with Bales at the helm. Returning from a bombing run on January 23, 1943, Bales had to make an emergency, wheels-up, landing, sliding the plane onto the runway at Chipping Warden, England. None of the crew were hurt, but the plane was too badly damaged to get back into service right away.

Captain Bales took the stick of another B17F. He carried his naming tradition forward with one important twist. The new plane became “FDR’s Potato Peeler Kids.”

The Caldwell native flew the second Potato Peeler on 13 more combat missions before crashing into the North Sea. The plan was last seen going down in a spin. Several parachutes popped, but no survivors were recovered.

Captain Ross C. Bales is memorialized on the Wall of the Missing in the Netherlands.

The original Potato Peeler and crew. After Captain Bales performed and emergency, wheels-up, landing, it was badly damaged. The crew moved to the new plane, but the Potato Peeler was repaired. It went on to complete an additional 22 combat missions before being shot down on November 5, 1943. One crew member died; nine were POWs.

The original Potato Peeler and crew. After Captain Bales performed and emergency, wheels-up, landing, it was badly damaged. The crew moved to the new plane, but the Potato Peeler was repaired. It went on to complete an additional 22 combat missions before being shot down on November 5, 1943. One crew member died; nine were POWs.  BALE'S CREW, FDR Potato Peeler Kids. Captain Ross C. Bales is standing in the back on the left. This was the plane that went down in the North Sea.

BALE'S CREW, FDR Potato Peeler Kids. Captain Ross C. Bales is standing in the back on the left. This was the plane that went down in the North Sea.

Published on September 23, 2024 04:00

September 22, 2024

A Placerville Murder

From time to time, I get questions from readers about an incident in Idaho history. I rarely get a question from out of the country, but I did receive one from the UK a few months back. Linda Bowditch was seeking information about an ancestor, Frederick Charles Cursons. About all she knew was that he was murdered in Placerville in 1865.

I was busy running for office at the time but circled around to the request again recently.

June 7, 1865, was a memorable day in Placerville. That was the day of four deaths, one accident, and three murders. It’s the murders that are remembered, including that of Fredrick Charles Cursons.

Cursons, an Englishman, was employed as a fiddler at Magnolia Hall in Idaho City. He had left his wife in Victoria, BC, to find his fortune in Idaho. It is unclear whether he hoped to find gold or make it with his music.

His musical endeavors ended when the Magnolia burned that June, taking much of Idaho City with it. Like many who found their beds turned to ashes, Cursons trekked to Placerville, looking for a place to live. He found a man named Larry Moulton there who had some skill with a banjo.

On Saturday evening, June 3, the pair set out for Centerville on foot, hoping to make a little coin there with their instruments. On their way, Cursons and Moulton stopped to chat and enjoy a drink of water with the gatekeeper at the toll gate.

Not long after they left, the two apparently encountered a robbery either in progress or just completed. George Wilson, a young miner, had been shot in the head at close range. The fiddler and the banjo player turned to run, only to feel bullets in their back.

So, three murders with robbery apparently the original motive—Wilson’s pockets were turned inside out, and his watch had been cut from its fob.

Deputy Sheriff Maloney gathered men by the dozens for a manhunt. Anger turned to rage, and there was talk of a lynching. Nearly a week later, three men, Charles Kimball, Ned Elwood, and one called Wiliams, who had an alias of Welch and another of Buck, were arrested. The guy with aliases was the prime suspect in the murder. He was wanted in California for a stage robbery and escape.

The men of the manhunt turned into a mob ready to string up Williams/Welch/Buck, but deputies escorted the prisoners out of town to the territorial jail in Idaho City.

The mob cooled down as the weeks passed while those in jail waited for the next sitting of the grand jury. When the jury finally convened, they found scant evidence against the three incarcerated men and set them free.

Musicians Cursons and Moulton were buried in the Placerville Cemetery without markers. Their killers, and the killers of George Wilson, were never brought to justice.

I was busy running for office at the time but circled around to the request again recently.

June 7, 1865, was a memorable day in Placerville. That was the day of four deaths, one accident, and three murders. It’s the murders that are remembered, including that of Fredrick Charles Cursons.

Cursons, an Englishman, was employed as a fiddler at Magnolia Hall in Idaho City. He had left his wife in Victoria, BC, to find his fortune in Idaho. It is unclear whether he hoped to find gold or make it with his music.

His musical endeavors ended when the Magnolia burned that June, taking much of Idaho City with it. Like many who found their beds turned to ashes, Cursons trekked to Placerville, looking for a place to live. He found a man named Larry Moulton there who had some skill with a banjo.

On Saturday evening, June 3, the pair set out for Centerville on foot, hoping to make a little coin there with their instruments. On their way, Cursons and Moulton stopped to chat and enjoy a drink of water with the gatekeeper at the toll gate.

Not long after they left, the two apparently encountered a robbery either in progress or just completed. George Wilson, a young miner, had been shot in the head at close range. The fiddler and the banjo player turned to run, only to feel bullets in their back.

So, three murders with robbery apparently the original motive—Wilson’s pockets were turned inside out, and his watch had been cut from its fob.

Deputy Sheriff Maloney gathered men by the dozens for a manhunt. Anger turned to rage, and there was talk of a lynching. Nearly a week later, three men, Charles Kimball, Ned Elwood, and one called Wiliams, who had an alias of Welch and another of Buck, were arrested. The guy with aliases was the prime suspect in the murder. He was wanted in California for a stage robbery and escape.

The men of the manhunt turned into a mob ready to string up Williams/Welch/Buck, but deputies escorted the prisoners out of town to the territorial jail in Idaho City.

The mob cooled down as the weeks passed while those in jail waited for the next sitting of the grand jury. When the jury finally convened, they found scant evidence against the three incarcerated men and set them free.

Musicians Cursons and Moulton were buried in the Placerville Cemetery without markers. Their killers, and the killers of George Wilson, were never brought to justice.

Published on September 22, 2024 04:00