Rick Just's Blog, page 6

November 22, 2024

Voices on the Wire

Editor’s note: we’re looking this week at the many changes brought on by the invention of widespread distribution of barbed wire. This is the fifth in a five-part series.

Telephones were a marvel when they first came to Idaho. Insulated copper wires strung from pole to pole soon became ubiquitous in cities and towns. But Ma Bell was reluctant to string that expensive wire to rural residences. Their cost per customer was just more than could be justified in the early days, so the phone companies (there were many telephone companies until consolidation came around the turn of the century).

But farmers and ranchers needed to communicate, too, even more so than city residents who could walk a couple of blocks and knock on a neighbor’s door.

Ranchers and farmers often skipped the phone companies and set up systems of their own when they realized they already had lines strung from house to house along the pastures and row crops: barbed wire.

Turning that prickly fencing into a phone line was no great trick. You just ran a wire from each house to the fence, then made sure there was a continuous connection all the way along. That meant tall poles on either side of the gates, with slender wire crawling up them and across pole to pole.

Sometimes as many as 20 telephones were wired together in a farming community. That worked pretty well, but it was a bit tiresome listening to the phones wing when you had a one-in-20 chance the call was for you. Users came up with ring codes to distinguish who they were trying to reach. Your ring might be two longs and short. It was a little like Morse Code. If you had too many people in your system you’d spend all day counting longs and shorts.

Crude as the system was and poor as the sound quality was, it was still a better way of communicating than sending some kid ten miles on a horse to fetch a doctor.

An 1887 illustration of Bell’s Magneto telephone system. Library of Congress.

An 1887 illustration of Bell’s Magneto telephone system. Library of Congress.

Telephones were a marvel when they first came to Idaho. Insulated copper wires strung from pole to pole soon became ubiquitous in cities and towns. But Ma Bell was reluctant to string that expensive wire to rural residences. Their cost per customer was just more than could be justified in the early days, so the phone companies (there were many telephone companies until consolidation came around the turn of the century).

But farmers and ranchers needed to communicate, too, even more so than city residents who could walk a couple of blocks and knock on a neighbor’s door.

Ranchers and farmers often skipped the phone companies and set up systems of their own when they realized they already had lines strung from house to house along the pastures and row crops: barbed wire.

Turning that prickly fencing into a phone line was no great trick. You just ran a wire from each house to the fence, then made sure there was a continuous connection all the way along. That meant tall poles on either side of the gates, with slender wire crawling up them and across pole to pole.

Sometimes as many as 20 telephones were wired together in a farming community. That worked pretty well, but it was a bit tiresome listening to the phones wing when you had a one-in-20 chance the call was for you. Users came up with ring codes to distinguish who they were trying to reach. Your ring might be two longs and short. It was a little like Morse Code. If you had too many people in your system you’d spend all day counting longs and shorts.

Crude as the system was and poor as the sound quality was, it was still a better way of communicating than sending some kid ten miles on a horse to fetch a doctor.

An 1887 illustration of Bell’s Magneto telephone system. Library of Congress.

An 1887 illustration of Bell’s Magneto telephone system. Library of Congress.

Published on November 22, 2024 04:00

November 21, 2024

Wired for War

Editor’s note: we’re looking this week at the many changes brought on by the invention of widespread distribution of barbed wire. This is the fourth in a five-part series.

Barbed wire had barely been introduced to Idaho when it became a defensive weapon of war. By 1888, British Army manuals included instructions for deploying the prickly stuff on perimeters to help keep the enemy out of military installations. It was commonly used in the Boer War and the Spanish-American War, but it really came into its own during World War I.

The miles of trenches dug by competing armies were not complete until a zig-zag barbed wire pattern was laid out between them. This was often wire with sharpened barbs or razor wire. Rolls of wire spread out concertina style became the norm, admired because of its lethality.

During World War II, barbed wire was the rule, spiraling along the tops of concentration camp fences in Europe, and controlling prisoners of war in the United States. It also marked the boundaries of interment camps for citizens of Japanese descent in internment camps, such as the Hunt Camp at Minidoka.

Tomorrow: Voices on the Wire

Barbed wire had barely been introduced to Idaho when it became a defensive weapon of war. By 1888, British Army manuals included instructions for deploying the prickly stuff on perimeters to help keep the enemy out of military installations. It was commonly used in the Boer War and the Spanish-American War, but it really came into its own during World War I.

The miles of trenches dug by competing armies were not complete until a zig-zag barbed wire pattern was laid out between them. This was often wire with sharpened barbs or razor wire. Rolls of wire spread out concertina style became the norm, admired because of its lethality.

During World War II, barbed wire was the rule, spiraling along the tops of concentration camp fences in Europe, and controlling prisoners of war in the United States. It also marked the boundaries of interment camps for citizens of Japanese descent in internment camps, such as the Hunt Camp at Minidoka.

Tomorrow: Voices on the Wire

Published on November 21, 2024 04:00

November 20, 2024

Legislators and Barbed Wire

Editor’s note: we’re looking this week at the many changes brought on by the invention of widespread distribution of barbed wire. This is the third in a five-part series.

By 1879, barbed wire was available at P. Sonna’s store at Main and Ninth. The Statesman brought up a drawback that caused some consternation in the early years. “The only objection to this kind of fence is that stock may be injured by running against it.” The story went on to say, “This can be avoided by placing a board or pole at the top.” The recommendation was a fence made of seven strands of wire. Why so many? To keep rabbits out and hogs in. Denying rabbits entry with a barbed wire fence was likely aspirational.

The 1879 article noted that the cost of barbed wire fencing was about equal to a board fence, but would be much more durable. That cost quickly came down as production ramped up.

Animal injury became a big concern in the early years of fencing. Idaho joined other territories in passing laws to require a wooden top rail on all barbed wire fences. Improvements in the design made the barbs less lethal, and that law was eventually dropped.

But barbed wire found itself tangled up with other laws. Ranchers sometimes illegally fenced off public land. Farmers who used the fence to keep cattle out sometimes found themselves embroiled in fence-cutting wars.

Barbed wire today is as synonymous with the Old West as tumbleweeds, though we tend to forget neither existed in the early days of cowboying. Wire fences quickly marked the end of the cattle-driving men on horseback. Barbed wire did away with the need for many cowboys. A fence simply better-controlled cows on the range.

Cheap fencing made property ownership in the West more obvious. Our culture loves to establish boundaries.

At the same time, the miles of what Indians sometimes called “devil’s rope” further restricted Idaho’s Tribes from following traditional hunting and harvesting patterns. If barbed wire did not tame the West, it certainly cinched it down.

Tomorrow: Wired for War

By 1879, barbed wire was available at P. Sonna’s store at Main and Ninth. The Statesman brought up a drawback that caused some consternation in the early years. “The only objection to this kind of fence is that stock may be injured by running against it.” The story went on to say, “This can be avoided by placing a board or pole at the top.” The recommendation was a fence made of seven strands of wire. Why so many? To keep rabbits out and hogs in. Denying rabbits entry with a barbed wire fence was likely aspirational.

The 1879 article noted that the cost of barbed wire fencing was about equal to a board fence, but would be much more durable. That cost quickly came down as production ramped up.

Animal injury became a big concern in the early years of fencing. Idaho joined other territories in passing laws to require a wooden top rail on all barbed wire fences. Improvements in the design made the barbs less lethal, and that law was eventually dropped.

But barbed wire found itself tangled up with other laws. Ranchers sometimes illegally fenced off public land. Farmers who used the fence to keep cattle out sometimes found themselves embroiled in fence-cutting wars.

Barbed wire today is as synonymous with the Old West as tumbleweeds, though we tend to forget neither existed in the early days of cowboying. Wire fences quickly marked the end of the cattle-driving men on horseback. Barbed wire did away with the need for many cowboys. A fence simply better-controlled cows on the range.

Cheap fencing made property ownership in the West more obvious. Our culture loves to establish boundaries.

At the same time, the miles of what Indians sometimes called “devil’s rope” further restricted Idaho’s Tribes from following traditional hunting and harvesting patterns. If barbed wire did not tame the West, it certainly cinched it down.

Tomorrow: Wired for War

Published on November 20, 2024 04:00

November 19, 2024

Do Fence Me In

Editor’s note: we’re looking this week at the many changes brought on by the invention of widespread distribution of barbed wire. This is the second in a five-part series.

Consider the problem early settlers had in keeping things in and out of their property. Domestic animals would stray if they could, and native animals knew no boundaries.

People have been using hedges since the Neolithic Age, planting shrubs and trees to serve as fences. In Idaho, lines of windbreak trees are common enough, but they rarely do more than slow the breeze, having little impact on animals. No shrub was available that would thrive and twine in this arid land.

In some areas, there were plentiful lava rocks to make short fences. Moving the rocks out of the fields made farming easier, so there are a few surrounds of lava rock. Building miles of lava rock fence was too labor-intensive.

Wood was a common fencing material, especially for corrals. But it was expensive and required a lot of maintenance on a larger scale.

Barbed wire appeared on the scene in the West in the 1870s. Many sources pick 1867 as the year of its invention, though there were earlier efforts. I found a patent dispute that awarded ownership rights to the inventor because of an 1850 display of the wire he could point to.

The first mention of barbed wire in the Idaho Statesman was in 1878. The short piece reported Oregon and Washington farmers experimenting with the material, describing it like this: “Posts are set in the ground and this wire which has sharp barbs twisted into it, is stretched from one to the other.” The article noted that 50 coils of the wire were headed to Walla Walla, the third shipment to date.

Tomorrow: Legislators and Barbed Wire J.F. Gidden’s 1874 patent for barbed wire was an improvement on earlier designs and became the standard.

J.F. Gidden’s 1874 patent for barbed wire was an improvement on earlier designs and became the standard.

Consider the problem early settlers had in keeping things in and out of their property. Domestic animals would stray if they could, and native animals knew no boundaries.

People have been using hedges since the Neolithic Age, planting shrubs and trees to serve as fences. In Idaho, lines of windbreak trees are common enough, but they rarely do more than slow the breeze, having little impact on animals. No shrub was available that would thrive and twine in this arid land.

In some areas, there were plentiful lava rocks to make short fences. Moving the rocks out of the fields made farming easier, so there are a few surrounds of lava rock. Building miles of lava rock fence was too labor-intensive.

Wood was a common fencing material, especially for corrals. But it was expensive and required a lot of maintenance on a larger scale.

Barbed wire appeared on the scene in the West in the 1870s. Many sources pick 1867 as the year of its invention, though there were earlier efforts. I found a patent dispute that awarded ownership rights to the inventor because of an 1850 display of the wire he could point to.

The first mention of barbed wire in the Idaho Statesman was in 1878. The short piece reported Oregon and Washington farmers experimenting with the material, describing it like this: “Posts are set in the ground and this wire which has sharp barbs twisted into it, is stretched from one to the other.” The article noted that 50 coils of the wire were headed to Walla Walla, the third shipment to date.

Tomorrow: Legislators and Barbed Wire

J.F. Gidden’s 1874 patent for barbed wire was an improvement on earlier designs and became the standard.

J.F. Gidden’s 1874 patent for barbed wire was an improvement on earlier designs and became the standard.

Published on November 19, 2024 04:00

November 18, 2024

The Steel Threads of the West

Invisible ubiquity has lately been fascinating me. What are the threads of society’s fabric that are essential but largely unseen? Underground utilities fall into this category: the pipes and conduits carrying water, electricity, and fiber optic lines. Don’t forget sewers and storm drains.

In the West, especially in southern Idaho, the arteries of the land are the canals. Many are still open and obvious if you turn your head for a glance as you roll over them at 45 mph, though miles and miles now dive under the crust of our civilization, still doing their duty beneath our feet.

Another Western ubiquity brought order and war in equal quantity when it first appeared. Invisibility was one of its selling points, though a deadly feature for some. The demarcation of ownership is now so commonly stretched across the land that our eyes edit it out: Barbed wire.

Over the next. Five days I’ll take a look at the history of barbed wire, especially as it relates to Idaho. You’ll learn about the love/hate relationship early settlers had with it, why Indians called it The Devil’s Rope, how this livestock control device became a tool of suppression and war, and why it was so important for communication.

Tomorrow: Do Fence Me In By Prosthetic Head - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

By Prosthetic Head - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

In the West, especially in southern Idaho, the arteries of the land are the canals. Many are still open and obvious if you turn your head for a glance as you roll over them at 45 mph, though miles and miles now dive under the crust of our civilization, still doing their duty beneath our feet.

Another Western ubiquity brought order and war in equal quantity when it first appeared. Invisibility was one of its selling points, though a deadly feature for some. The demarcation of ownership is now so commonly stretched across the land that our eyes edit it out: Barbed wire.

Over the next. Five days I’ll take a look at the history of barbed wire, especially as it relates to Idaho. You’ll learn about the love/hate relationship early settlers had with it, why Indians called it The Devil’s Rope, how this livestock control device became a tool of suppression and war, and why it was so important for communication.

Tomorrow: Do Fence Me In

By Prosthetic Head - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

By Prosthetic Head - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Published on November 18, 2024 04:00

November 7, 2024

Size Matters

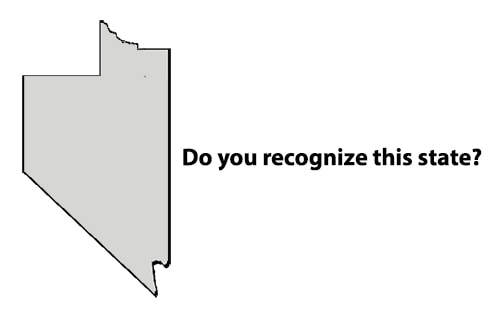

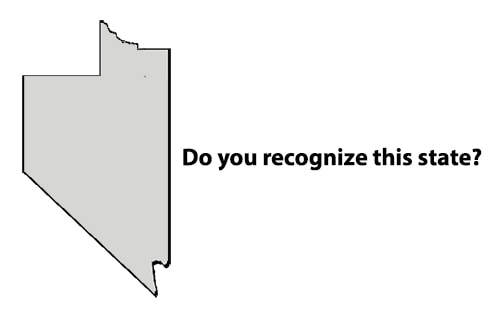

You’ve heard that Idaho’s largest county, Idaho County, is larger than three states, Rhode Island, Delaware, and Connecticut. In fact, you’ll sometimes hear that you could put all three of those states inside Idaho County.

Take this with a grain of salt. The area of a state seems to be determined by… what? Humidity? You’ll find numerous conflicting numbers if you Google the area of our smallest states. Rhode Island’s area is 1,045 square miles. Unless it’s 1,545 square miles. Or 1,037 square miles. Delaware comes in at 2,489 square miles or 1,982 square miles and 1,954 square miles. Comparatively gigantic, Connecticut is 5,567 square miles, or possibly 5,028 square miles, or 5,018 square miles.

Not surprisingly, when asking about the area of Idaho County in square miles, you get a couple of answers, 8,503 or 8,477 square miles.

If you took the lowest numbers for the area of the three smallest states, yes, they could be shoehorned into Idaho County. But use the highest numbers, and only any two of the three would fit, with nearly enough left over to cram in the third one.

I thought it might be fun to see how Idaho’s smallest county, Clark, measures up to small states. Clark County is 1,765 square miles. Now, don’t make me fit a jigsaw piece into a differently shaped hole, but if the square miles in Clark County were SQUARE, Rhode Island, the smallest state in the US, would fit easily inside of Idaho’s smallest county.

How about the number of counties in Idaho compared with other states? Idaho has 44 counties. The state with the fewest is Delaware, with three. Unless you count Rhode Island and Connecticut, which don’t bother having any counties at all. And, of course, Louisiana doesn’t call its political subdivisions counties. They are parishes, and there are 64 of them.

Do we really need a drum roll to announce the state with the most counties? Texas, at 254.

None of this useless information is likely to show up on a test, fourth graders, so relax.

Take this with a grain of salt. The area of a state seems to be determined by… what? Humidity? You’ll find numerous conflicting numbers if you Google the area of our smallest states. Rhode Island’s area is 1,045 square miles. Unless it’s 1,545 square miles. Or 1,037 square miles. Delaware comes in at 2,489 square miles or 1,982 square miles and 1,954 square miles. Comparatively gigantic, Connecticut is 5,567 square miles, or possibly 5,028 square miles, or 5,018 square miles.

Not surprisingly, when asking about the area of Idaho County in square miles, you get a couple of answers, 8,503 or 8,477 square miles.

If you took the lowest numbers for the area of the three smallest states, yes, they could be shoehorned into Idaho County. But use the highest numbers, and only any two of the three would fit, with nearly enough left over to cram in the third one.

I thought it might be fun to see how Idaho’s smallest county, Clark, measures up to small states. Clark County is 1,765 square miles. Now, don’t make me fit a jigsaw piece into a differently shaped hole, but if the square miles in Clark County were SQUARE, Rhode Island, the smallest state in the US, would fit easily inside of Idaho’s smallest county.

How about the number of counties in Idaho compared with other states? Idaho has 44 counties. The state with the fewest is Delaware, with three. Unless you count Rhode Island and Connecticut, which don’t bother having any counties at all. And, of course, Louisiana doesn’t call its political subdivisions counties. They are parishes, and there are 64 of them.

Do we really need a drum roll to announce the state with the most counties? Texas, at 254.

None of this useless information is likely to show up on a test, fourth graders, so relax.

Published on November 07, 2024 04:00

November 6, 2024

A 1905 Photo Bomb

Is that Waldo?

Many readers will remember the story about “Jimmy the Stiff” I posted a few years ago. That story resulted in a successful GoFundMe campaign to get James Hogan a cemetery marker.

Idaho Statesman reporter Katherine Jones covered that effort. She later sent me this photo, sent to her by Roxann Howell Dehlin of Nampa. Ms. Dehlin saw a photo of Hogan that ran with the article, looking a bit out of place in his scruffy clothes, posing with elected officials. It reminded her of this picture her family has.

The souvenir photo, apparently made for Sen. Anthony Russell, is well done and goes to great lengths to identify him. Left nameless is the gentleman at the upper left of the picture, peeking slyly around the wall in what we might today call a photo bomb.

Practically everyone in the picture wears a hat—even the photo bomber—with the exception of two gentlemen relegated to the back row, perhaps for their error in haberdashery.

Mysteries—even the most insignificant ones—are fun. We know next to nothing about who this man was, though it is probably safe to say he was not an Idaho state senator in 1905. What’s your wild guess?

Many readers will remember the story about “Jimmy the Stiff” I posted a few years ago. That story resulted in a successful GoFundMe campaign to get James Hogan a cemetery marker.

Idaho Statesman reporter Katherine Jones covered that effort. She later sent me this photo, sent to her by Roxann Howell Dehlin of Nampa. Ms. Dehlin saw a photo of Hogan that ran with the article, looking a bit out of place in his scruffy clothes, posing with elected officials. It reminded her of this picture her family has.

The souvenir photo, apparently made for Sen. Anthony Russell, is well done and goes to great lengths to identify him. Left nameless is the gentleman at the upper left of the picture, peeking slyly around the wall in what we might today call a photo bomb.

Practically everyone in the picture wears a hat—even the photo bomber—with the exception of two gentlemen relegated to the back row, perhaps for their error in haberdashery.

Mysteries—even the most insignificant ones—are fun. We know next to nothing about who this man was, though it is probably safe to say he was not an Idaho state senator in 1905. What’s your wild guess?

Published on November 06, 2024 04:00

November 5, 2024

A Nevada Land Grab

In the early days of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho territories boundaries bounced around a bit until they settled on the shapes you know today. I was surprised to see an article in the January 25, 1870 Idaho Statesman about an attempt to bite off a good chunk of Idaho by our neighbors to the south.

The article began, “We publish today a copy of a bill introduced into the United States senate by Senator Stewart of Nevada to annex the county of Owyhee and a large part of Oneida to that state.”

If the bill had passed, it likely would have led to a land grab by Oregon and Washington to annex other parts of the seven-year-old Idaho Territory. It perturbed the Statesman that the bill did not even mention the word Idaho. As the article stated, “The bill so reads that the people of Nevada are the only parties to be consulted. To the people of Idaho there is not so much as a ‘by your leave’ not even to the people of Owyhee county who are to be thus raffled off for the benefit of bankrupt Nevada.”

The Statesman didn’t take the effort very seriously, and neither did Congress. The next time the bill was mentioned in the paper was 50 years later as a footnote in the 50 Years Ago column.

The article began, “We publish today a copy of a bill introduced into the United States senate by Senator Stewart of Nevada to annex the county of Owyhee and a large part of Oneida to that state.”

If the bill had passed, it likely would have led to a land grab by Oregon and Washington to annex other parts of the seven-year-old Idaho Territory. It perturbed the Statesman that the bill did not even mention the word Idaho. As the article stated, “The bill so reads that the people of Nevada are the only parties to be consulted. To the people of Idaho there is not so much as a ‘by your leave’ not even to the people of Owyhee county who are to be thus raffled off for the benefit of bankrupt Nevada.”

The Statesman didn’t take the effort very seriously, and neither did Congress. The next time the bill was mentioned in the paper was 50 years later as a footnote in the 50 Years Ago column.

Published on November 05, 2024 04:00

November 4, 2024

Jimmy Stewart in Boise

The burning question in Boise on Valentine’s Day, 1943, was “is Jimmy Stewart really here?” The Idaho Statesman that day reported in its About Town column that it is was a rumor. “But that didn’t prevent Boise’s female population from dreaming, wondering, anticipating—and taking a good second look at every lieutenant they passed on the street.”

On page one of the same edition, the story read, “He’s Jimmy Stewart to millions of movie fans, but at Gowen Field Saturday he registered as First Lt. James M. Stewart, and on the routine registration forms, in the listing his occupation in civilian life he placed a question mark after the word ‘actor.’”

Stewart had been determined to serve his country. When he tried to enlist in the army, they turned him down because he was too skinny. At 6-foot-3, he tipped the scale at only 138 pounds. So, putting on weight became his goal. He started on a diet heavy with steaks, pasta, and milkshakes. When he stepped on the scales at his second physical in March of 1941, he was still a little shy of the minimum weight, but someone fudged the figures by a few ounces, and Jimmy Stewart was on his way to boot camp.

Eager as he was to serve, it was a bit of an adjustment. He’d been averaging $12,000 a week as an actor, according to the article “Mr. Stewart Goes to War,” by Richard L. Hayes on the HistoryNet website. An army private’s pay was $21 a month. It is reported that he sent $2.10 a month to his agent.

Stewart had a college degree from Princeton, and he was already licensed to fly multi-engine planes, so it was no surprise when he got his commission in January 1942. That meant he could wear his uniform when he presented Gary Cooper the Academy Award for best actor for Cooper’s performance in Sergeant York. Stewart had won the Oscar the year before for his role in Philadelphia Story.

The actor became a flight instructor, serving first at Mather Field, California, then transferred to Kirkland, New Mexico for bombardier school. He was at another base in New Mexico and HQ for the Second Air Force in Salt Lake City before coming to Boise, where he was a flight instructor for B-17s. He was also a sensation.

The About Town column on February 21, 1943, read, “Being constantly on the lookout for Jimmy Stewart has made Boiseans celebrity-conscious. We could have sworn we’ve been seeing Lucille Ball and John Garfield night-spotting about town…but it turned out to be Eileen Cummock, beauteous Gowen Field civilian employee, and Capt. Cox.”

About Town was breathless with chatter about Stewart. It wasn’t until June 21 that the paper published an actual photograph of the “ordinary American serving his country.” He was shown visiting back stage at a Gowen Field minstrel show at the Pinney Theater. They published another six days later of Stewart shaking hands with someone at a “recent Gowen Field Frolic.”

In July that year, Stewart got his captain’s bars and was called back to Hollywood to attend a wedding. In August, his stint in Boise was over. His stint in the military had just begun.

Jimmy Stewart would fly 20 bombing missions over Europe in World War II. Those were the missions he was credited with. He often flew self-assigned as a combat crewman when he was a commander. Oddly, he flew on one bombing mission in Vietnam as a non-duty observer in a B-52 when he was Air Force Reserve Brigadier General Stewart in 1966. He retired from the Air Force in 1968. In 1985, President Reagan promoted him to Major General on the retired list and presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Stewart didn’t spend a lot of time talking about the war or his military service. In fact, his movie contracts always included a clause that his military service would not be used as part of the publicity for the movie. Stewart passed away in 1997.

On page one of the same edition, the story read, “He’s Jimmy Stewart to millions of movie fans, but at Gowen Field Saturday he registered as First Lt. James M. Stewart, and on the routine registration forms, in the listing his occupation in civilian life he placed a question mark after the word ‘actor.’”

Stewart had been determined to serve his country. When he tried to enlist in the army, they turned him down because he was too skinny. At 6-foot-3, he tipped the scale at only 138 pounds. So, putting on weight became his goal. He started on a diet heavy with steaks, pasta, and milkshakes. When he stepped on the scales at his second physical in March of 1941, he was still a little shy of the minimum weight, but someone fudged the figures by a few ounces, and Jimmy Stewart was on his way to boot camp.

Eager as he was to serve, it was a bit of an adjustment. He’d been averaging $12,000 a week as an actor, according to the article “Mr. Stewart Goes to War,” by Richard L. Hayes on the HistoryNet website. An army private’s pay was $21 a month. It is reported that he sent $2.10 a month to his agent.

Stewart had a college degree from Princeton, and he was already licensed to fly multi-engine planes, so it was no surprise when he got his commission in January 1942. That meant he could wear his uniform when he presented Gary Cooper the Academy Award for best actor for Cooper’s performance in Sergeant York. Stewart had won the Oscar the year before for his role in Philadelphia Story.

The actor became a flight instructor, serving first at Mather Field, California, then transferred to Kirkland, New Mexico for bombardier school. He was at another base in New Mexico and HQ for the Second Air Force in Salt Lake City before coming to Boise, where he was a flight instructor for B-17s. He was also a sensation.

The About Town column on February 21, 1943, read, “Being constantly on the lookout for Jimmy Stewart has made Boiseans celebrity-conscious. We could have sworn we’ve been seeing Lucille Ball and John Garfield night-spotting about town…but it turned out to be Eileen Cummock, beauteous Gowen Field civilian employee, and Capt. Cox.”

About Town was breathless with chatter about Stewart. It wasn’t until June 21 that the paper published an actual photograph of the “ordinary American serving his country.” He was shown visiting back stage at a Gowen Field minstrel show at the Pinney Theater. They published another six days later of Stewart shaking hands with someone at a “recent Gowen Field Frolic.”

In July that year, Stewart got his captain’s bars and was called back to Hollywood to attend a wedding. In August, his stint in Boise was over. His stint in the military had just begun.

Jimmy Stewart would fly 20 bombing missions over Europe in World War II. Those were the missions he was credited with. He often flew self-assigned as a combat crewman when he was a commander. Oddly, he flew on one bombing mission in Vietnam as a non-duty observer in a B-52 when he was Air Force Reserve Brigadier General Stewart in 1966. He retired from the Air Force in 1968. In 1985, President Reagan promoted him to Major General on the retired list and presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Stewart didn’t spend a lot of time talking about the war or his military service. In fact, his movie contracts always included a clause that his military service would not be used as part of the publicity for the movie. Stewart passed away in 1997.

Published on November 04, 2024 04:00

November 3, 2024

Counterfeiters

When perusing photos at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives, a typical little family portrait caught my eye. It wasn’t so much the photo but the neatly written note on the cardstock where it was mounted. It said “Eddy, John, and family. He made counterfeit 25¢ pieces at Little Salmon.”

I wondered why it would be worth risking prison to make counterfeit quarters. Sure, two bits was worth more in 1897, but was it worth enough to risk making little rocks out of big ones in Idaho’s penitentiary?

No, it wasn’t. I did a newspaper search for Mr. Eddy and found that he was arrested for counterfeiting in 1897, but quarters didn’t come into play. Someone had simply written the wrong symbol next to the photo. Oh, and the wrong number. It was $5, $10, and $20 gold pieces Eddy and his accomplices were counterfeiting.

As if counterfeiting weren’t bad enough, the gang gave their whole operation a reprehensible twist. To make the coins they would sometimes use silver and sometimes use cheaper babbitt metal (composed of tin, antimony, lead, and copper), heating it up and pouring the melted metal into molds. Then, they put a thin coat of gold over the coin. Once they had a supply, they would target Nez Perce Indians, trading their phony coins for bills the Indians received in government payments. The Nez Perce preferred the jingle of coins to paper money. The gang got away with it for a while, but Deputy U.S. Marshall Mounce, working out of Grangeville, hired a detective to infiltrate the gang. They were caught getting ready to pull off a scheme where they were to race a horse at an Indian meet and change their winnings from greenbacks to funny money.

John Eddy, his brother Lewis, and five other men were convicted of counterfeiting and each was sentenced for up to 16 years in prison. They were called by one newspaper “the most successful gang of counterfeiters that ever operated in the northwest.” I would probably hesitate to assign the word “successful” to people who went to prison, but that’s just me. Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

I wondered why it would be worth risking prison to make counterfeit quarters. Sure, two bits was worth more in 1897, but was it worth enough to risk making little rocks out of big ones in Idaho’s penitentiary?

No, it wasn’t. I did a newspaper search for Mr. Eddy and found that he was arrested for counterfeiting in 1897, but quarters didn’t come into play. Someone had simply written the wrong symbol next to the photo. Oh, and the wrong number. It was $5, $10, and $20 gold pieces Eddy and his accomplices were counterfeiting.

As if counterfeiting weren’t bad enough, the gang gave their whole operation a reprehensible twist. To make the coins they would sometimes use silver and sometimes use cheaper babbitt metal (composed of tin, antimony, lead, and copper), heating it up and pouring the melted metal into molds. Then, they put a thin coat of gold over the coin. Once they had a supply, they would target Nez Perce Indians, trading their phony coins for bills the Indians received in government payments. The Nez Perce preferred the jingle of coins to paper money. The gang got away with it for a while, but Deputy U.S. Marshall Mounce, working out of Grangeville, hired a detective to infiltrate the gang. They were caught getting ready to pull off a scheme where they were to race a horse at an Indian meet and change their winnings from greenbacks to funny money.

John Eddy, his brother Lewis, and five other men were convicted of counterfeiting and each was sentenced for up to 16 years in prison. They were called by one newspaper “the most successful gang of counterfeiters that ever operated in the northwest.” I would probably hesitate to assign the word “successful” to people who went to prison, but that’s just me.

Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Published on November 03, 2024 04:00