Rick Just's Blog, page 18

July 12, 2024

Boise's Lemp Triangle

Boise has played the waiting game several times in its history. Citizens have waited for a promised project for decades while staring into a hole or across a dusty gravel parking lot.

The Hole at 8th and Main gaped there on the verge of great things for more than 20 years. Zions Bank opened its new tower in 2014, finally fitting into the footprint of the old Eastman Building that burned in 1987. The gravel parking lot that covered the block where the Boise Convention Center and other downtown amenities now sit was a point of conjecture for years. Ideas bounced around until the proposal to put a squat, concrete shopping mall that would be as enticing as a prison on the site invigorated enough opposition to rethink and renew downtown.

But those projects were just blips compared with the field of dreams known as the Lemp Triangle. Dreamers started envisioning its future in 1870 and continued plotting until 1937, when something important finally got built.

The Lemp Triangle is an accident of platting. When city fathers drew up the first maps of Boise, they platted it so that streets would run roughly parallel to the Boise River. That was just a convenient way to layout a town that might not be around very long. As the City survived and grew, developers of new additions mapped streets that ran to the points of a compass. Fitting the new additions to the original town plat created some odd-shaped properties. One became known as the Lemp Triangle in the North End, bounded today by W Resseguie to the north, N 13th to the east, W Fort to the south, and N 15th to the west. Clever readers may now be asking themselves why a triangle has four sides. The answer is that the property is a triangle with the western tip cut off. "Lemp Sort-of-a Triangle" just doesn't have the verve of the shorter name.

John Lemp, brewer, businessman, and local politician, began planning to sell lots in his new Lemp Addition north of the City in 1891. Mayor James Pinney saw the wisdom in snugging up the Lemp Addition to the original plat for Boise, so he deeded what became the Triangle to Lemp for $1.

Then came the tricky part. Did Boise own the land in the first place? In 1867 Boise had petitioned the US Department of the Interior for a townsite patent. The City was expecting a patent for 410 acres, the size of the original plat. Instead, they received a patent for an extra 32 acres, which included the Lemp Triangle. Maybe.

Imagine John Lemp's surprise when in August 1892, J.C. Pence, another local politician and businessman, began constructing a house on the Lemp Triangle. Lemp offered to pay Pence a small sum to remove the house. Pence declined, claiming that he owned the land. So on August 18, Lemp sent a group of armed men to demolish the house. They piled the resulting debris in the street, then tore up the foundation.

This dispute began a series of lawsuits that kept the property tied up for the next 25 years. At various times it became clear that Pence owned the property or that Lemp owned the property, or that the City owned the property. There were wins and losses enough to keep all parties confused. When the last, really, truly, absolutely final decision came down, the Idaho Supreme Court ruled that Lemp owned the property through adverse possession. Unfortunately, Lemp had been dead four years by that time, so he didn't get a chance to celebrate.

With ownership determined, the Lemp estate began advertising lots for sale in the Lemp Triangle. But remember those dreams and visions that had been bouncing around? Citizens had talked up a public park on the site for years. They dreamed about a playground for kids and a baseball field. At one point, when the City was temporarily confident it owned the property, voters narrowly turned down a proposal to make it a park.

In 1922 the Lemp estate came close to making the park dreams come true when it offered the city Camel's Back and the Lemp Triangle for the bargain price of $35,000. One stipulation was that any park built in the Triangle would be called John Lemp Park. The City mulled that over for a while. Maybe too long.

The Boise School Board finally put all disputes and dreams to rest when in 1925, they purchased the Triangle for $22,500. But, true to the site's history, it was another dozen years before anything happened there. North Junior High, designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, was built in 1937.

The school, lauded for its art deco design, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. The Lemp Triangle itself might have qualified without the beautiful public building given the long, sordid history of nothing happening there.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

The Hole at 8th and Main gaped there on the verge of great things for more than 20 years. Zions Bank opened its new tower in 2014, finally fitting into the footprint of the old Eastman Building that burned in 1987. The gravel parking lot that covered the block where the Boise Convention Center and other downtown amenities now sit was a point of conjecture for years. Ideas bounced around until the proposal to put a squat, concrete shopping mall that would be as enticing as a prison on the site invigorated enough opposition to rethink and renew downtown.

But those projects were just blips compared with the field of dreams known as the Lemp Triangle. Dreamers started envisioning its future in 1870 and continued plotting until 1937, when something important finally got built.

The Lemp Triangle is an accident of platting. When city fathers drew up the first maps of Boise, they platted it so that streets would run roughly parallel to the Boise River. That was just a convenient way to layout a town that might not be around very long. As the City survived and grew, developers of new additions mapped streets that ran to the points of a compass. Fitting the new additions to the original town plat created some odd-shaped properties. One became known as the Lemp Triangle in the North End, bounded today by W Resseguie to the north, N 13th to the east, W Fort to the south, and N 15th to the west. Clever readers may now be asking themselves why a triangle has four sides. The answer is that the property is a triangle with the western tip cut off. "Lemp Sort-of-a Triangle" just doesn't have the verve of the shorter name.

John Lemp, brewer, businessman, and local politician, began planning to sell lots in his new Lemp Addition north of the City in 1891. Mayor James Pinney saw the wisdom in snugging up the Lemp Addition to the original plat for Boise, so he deeded what became the Triangle to Lemp for $1.

Then came the tricky part. Did Boise own the land in the first place? In 1867 Boise had petitioned the US Department of the Interior for a townsite patent. The City was expecting a patent for 410 acres, the size of the original plat. Instead, they received a patent for an extra 32 acres, which included the Lemp Triangle. Maybe.

Imagine John Lemp's surprise when in August 1892, J.C. Pence, another local politician and businessman, began constructing a house on the Lemp Triangle. Lemp offered to pay Pence a small sum to remove the house. Pence declined, claiming that he owned the land. So on August 18, Lemp sent a group of armed men to demolish the house. They piled the resulting debris in the street, then tore up the foundation.

This dispute began a series of lawsuits that kept the property tied up for the next 25 years. At various times it became clear that Pence owned the property or that Lemp owned the property, or that the City owned the property. There were wins and losses enough to keep all parties confused. When the last, really, truly, absolutely final decision came down, the Idaho Supreme Court ruled that Lemp owned the property through adverse possession. Unfortunately, Lemp had been dead four years by that time, so he didn't get a chance to celebrate.

With ownership determined, the Lemp estate began advertising lots for sale in the Lemp Triangle. But remember those dreams and visions that had been bouncing around? Citizens had talked up a public park on the site for years. They dreamed about a playground for kids and a baseball field. At one point, when the City was temporarily confident it owned the property, voters narrowly turned down a proposal to make it a park.

In 1922 the Lemp estate came close to making the park dreams come true when it offered the city Camel's Back and the Lemp Triangle for the bargain price of $35,000. One stipulation was that any park built in the Triangle would be called John Lemp Park. The City mulled that over for a while. Maybe too long.

The Boise School Board finally put all disputes and dreams to rest when in 1925, they purchased the Triangle for $22,500. But, true to the site's history, it was another dozen years before anything happened there. North Junior High, designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, was built in 1937.

The school, lauded for its art deco design, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. The Lemp Triangle itself might have qualified without the beautiful public building given the long, sordid history of nothing happening there.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

Published on July 12, 2024 04:00

July 11, 2024

Idaho's Essential Book on Place Names

When it comes to Idaho place names, Lalia Boone was the acknowledged expert. Her book

Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary

is indispensable for Idaho historians.

You might think that Boone came from an old Idaho family and grew up hearing Idaho place names over the dinner table. If you thought that, you’d be way off.

Boone was born in 1907, in Tehuacana, Texas. She graduated from Westminster Junior College there in 1925. Boone taught in county schools in Texas for years, becoming a principal in 1944. A lifelong educator, she never stopped learning, getting a BA in English in 1938 from East Texas State College, and a masters in medieval literature and linguistics from the University of Oklahoma in 1947. Boone was a trailblazer in 1951 when she became the first woman to get a doctorate at the University of Florida.

In 1965 Boone took a job as professor of English at the University of Idaho. She taught there until her retirement in 1973.

Lalia Boone became interested in Idaho place names because many of them seemed strange to her southern ears. Her curiosity led her to found the Idaho Place Names Project in 1966. The project received early funding from the National Science Foundation, and it became one of two pilot projects nationwide in the American Name Society Place Name Survey.

She and her students spent years interviewing locals across the state for the project, the archives of which are housed at the University of Idaho. Cort Conley, who ran the University of Idaho Press at the time, said that Boone “Commandeered derivations from her students the way wool socks snag wood ticks.”

The first book that came from the project was a volume on Latah County names in 1983. The statewide edition was published the following year. Sadly, the book is currently out of print, but good used copies are often available in local bookstores and on Amazon.

Lalia Boone died at 83 in 1990.

You might think that Boone came from an old Idaho family and grew up hearing Idaho place names over the dinner table. If you thought that, you’d be way off.

Boone was born in 1907, in Tehuacana, Texas. She graduated from Westminster Junior College there in 1925. Boone taught in county schools in Texas for years, becoming a principal in 1944. A lifelong educator, she never stopped learning, getting a BA in English in 1938 from East Texas State College, and a masters in medieval literature and linguistics from the University of Oklahoma in 1947. Boone was a trailblazer in 1951 when she became the first woman to get a doctorate at the University of Florida.

In 1965 Boone took a job as professor of English at the University of Idaho. She taught there until her retirement in 1973.

Lalia Boone became interested in Idaho place names because many of them seemed strange to her southern ears. Her curiosity led her to found the Idaho Place Names Project in 1966. The project received early funding from the National Science Foundation, and it became one of two pilot projects nationwide in the American Name Society Place Name Survey.

She and her students spent years interviewing locals across the state for the project, the archives of which are housed at the University of Idaho. Cort Conley, who ran the University of Idaho Press at the time, said that Boone “Commandeered derivations from her students the way wool socks snag wood ticks.”

The first book that came from the project was a volume on Latah County names in 1983. The statewide edition was published the following year. Sadly, the book is currently out of print, but good used copies are often available in local bookstores and on Amazon.

Lalia Boone died at 83 in 1990.

Published on July 11, 2024 04:00

July 10, 2024

Blackfoot's Billionaire

How many billionaires have been born in Blackfoot? I’ll wait while you compile the list. Here’s a hint: I was born there. But I’m not on that list.

I can think of only one but correct me if you came up with others.

Jon Huntsman Sr., born in Blackfoot, was a billionaire chemical industrialist, which is an achievement in its own right. But he was also a notoriously generous philanthropist, giving away more than $1.5 billion during his life and founding the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in 1993, one of America’s major cancer research centers.

Huntsman had a political side. He was the White House Staff Secretary in the Nixon administration. In 1988 he began raising money to run for governor of Utah. He backed out of the race to back Governor Norm Bangerter, saying that party unity was more important to him than a political career.

His son, Jon Huntsman Jr., became governor of Utah in 2005, serving until 2009. Huntsman Jr also served as U.S. Ambassador to China, after an unsuccessful presidential run.

Both Jon Huntsman Sr and Jon Huntsman Jr have extensive Wikipedia pages, should you want to read more.

The billionaire philanthropist was born in Blackfoot, Idaho in 1937. His father, Alonzo Blaine Huntsman was a piano teacher. The family moved to Palo Alto, California in 1950 where Alonzo earned an M.A. and Ed.D, later becoming a superintendent of schools.

Jon Huntsman Sr, courtesy of the Science History Institute.

Jon Huntsman Sr, courtesy of the Science History Institute.

I can think of only one but correct me if you came up with others.

Jon Huntsman Sr., born in Blackfoot, was a billionaire chemical industrialist, which is an achievement in its own right. But he was also a notoriously generous philanthropist, giving away more than $1.5 billion during his life and founding the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in 1993, one of America’s major cancer research centers.

Huntsman had a political side. He was the White House Staff Secretary in the Nixon administration. In 1988 he began raising money to run for governor of Utah. He backed out of the race to back Governor Norm Bangerter, saying that party unity was more important to him than a political career.

His son, Jon Huntsman Jr., became governor of Utah in 2005, serving until 2009. Huntsman Jr also served as U.S. Ambassador to China, after an unsuccessful presidential run.

Both Jon Huntsman Sr and Jon Huntsman Jr have extensive Wikipedia pages, should you want to read more.

The billionaire philanthropist was born in Blackfoot, Idaho in 1937. His father, Alonzo Blaine Huntsman was a piano teacher. The family moved to Palo Alto, California in 1950 where Alonzo earned an M.A. and Ed.D, later becoming a superintendent of schools.

Jon Huntsman Sr, courtesy of the Science History Institute.

Jon Huntsman Sr, courtesy of the Science History Institute.

Published on July 10, 2024 04:00

July 9, 2024

More on More and Moore

Mores Creek is a tributary of the Boise River. Misspellings often find their way into place names, so it’s not surprising that it has also been known as Moore Creek and Moores Creek. J. Marion More, for whom the stream is named, used both last names, so the confusion is unsurprising.

More was born John N. Moore in Tennessee in 1830. He carried his given name as he struck out for California when he was about 20. He settled in Mariposa where he became an undersheriff and was prominent in local Masonic affairs. Sometime in the late 1850s, Moore got into a “fracas” of some sort that was embarrassing enough that he skipped town, headed north to Washington Territory, and changed his name to John Marion More.

His past apparently forgotten, More was elected to the Washington Territorial Legislature in 1861 from Walla Walla. In 1862, stories of gold in eastern Oregon Territory enticed More and his friend, D.H. Fogus to the Boise Hills. More and Fogus were among the first miners to strike gold. More led a mining party that founded Idaho City on October 7, 1862. He staked some paying claims before heading back to Olympia to serve a second term in the Washington Territorial Legislature, where he was unsuccessful in pushing to create a new territory east of the Cascades. Other interests prevailed in forming a territory with different boundaries, called Idaho Territory, on March 4, 1863.

More came back to the Boise Basin where his mines were doing well. He and Fogus bought controlling interest in the Oro Fino and Morning Star mines in Owyhee County. They pulled more than a million dollars from those operations within two years. Nevertheless, the bills caught up with the mine developers and they went bankrupt in 1866.

J. Marion More’s fortunes had again turned around by the spring of 1867. He had acquired a large interest in the Ida-Elmore properties atop War Eagle Mountain. An underground war had erupted between those working the Ida-Elmore and the Golden Chariot mines over the boundaries of those claims. More had been a key negotiator in bringing peace to the miners.

The agreement that brought the peace was not universally embraced by every miner. One Sam Lockhart, who had worked for the Golden Chariot, confronted More after the latter had been celebrating with alcohol and friends on the afternoon of April 1, 1868. Lockhart and More exchanged heated words. More, according to Lockhart, had raised his cane as if to strike the miner. Lockhart pulled his gun and shot More in the chest.

Bullets flew back and forth. Lockhart took one to the shoulder. His friends dragged More away to a local restaurant, where he died three hours later.

Lockhart insisted that a man in More’s party fired the first shot. That became moot when gangrene set in, causing Lockhart to lose first his arm, then his life, a few weeks later.

According to Findagrave.com, two stones mark J. Marion More’s grave, one spelling it More and one Moore. Oh, and the N. in his given name stood for Neptune.

More was born John N. Moore in Tennessee in 1830. He carried his given name as he struck out for California when he was about 20. He settled in Mariposa where he became an undersheriff and was prominent in local Masonic affairs. Sometime in the late 1850s, Moore got into a “fracas” of some sort that was embarrassing enough that he skipped town, headed north to Washington Territory, and changed his name to John Marion More.

His past apparently forgotten, More was elected to the Washington Territorial Legislature in 1861 from Walla Walla. In 1862, stories of gold in eastern Oregon Territory enticed More and his friend, D.H. Fogus to the Boise Hills. More and Fogus were among the first miners to strike gold. More led a mining party that founded Idaho City on October 7, 1862. He staked some paying claims before heading back to Olympia to serve a second term in the Washington Territorial Legislature, where he was unsuccessful in pushing to create a new territory east of the Cascades. Other interests prevailed in forming a territory with different boundaries, called Idaho Territory, on March 4, 1863.

More came back to the Boise Basin where his mines were doing well. He and Fogus bought controlling interest in the Oro Fino and Morning Star mines in Owyhee County. They pulled more than a million dollars from those operations within two years. Nevertheless, the bills caught up with the mine developers and they went bankrupt in 1866.

J. Marion More’s fortunes had again turned around by the spring of 1867. He had acquired a large interest in the Ida-Elmore properties atop War Eagle Mountain. An underground war had erupted between those working the Ida-Elmore and the Golden Chariot mines over the boundaries of those claims. More had been a key negotiator in bringing peace to the miners.

The agreement that brought the peace was not universally embraced by every miner. One Sam Lockhart, who had worked for the Golden Chariot, confronted More after the latter had been celebrating with alcohol and friends on the afternoon of April 1, 1868. Lockhart and More exchanged heated words. More, according to Lockhart, had raised his cane as if to strike the miner. Lockhart pulled his gun and shot More in the chest.

Bullets flew back and forth. Lockhart took one to the shoulder. His friends dragged More away to a local restaurant, where he died three hours later.

Lockhart insisted that a man in More’s party fired the first shot. That became moot when gangrene set in, causing Lockhart to lose first his arm, then his life, a few weeks later.

According to Findagrave.com, two stones mark J. Marion More’s grave, one spelling it More and one Moore. Oh, and the N. in his given name stood for Neptune.

Published on July 09, 2024 04:00

July 8, 2024

Farragut ID Tags

Dan Eggart sent me a photo of his dad's ID tag, Ronald E. Eggart. Ronald Eggart served at Farragut for a time before going to Europe during WWII. Both of his brothers also served there.

Dan wondered what kind of ID tag it was. I’d never seen one before, so I asked Dennis Woolford who is a ranger at Farragut State Park and coauthor of a book on Farragut Naval Training Station. Dennis said it was an ID tag often used by civilians working on the base. He sent a photo (below) that showed several people who worked in Supply and Accounting wearing similar badges. Most wearing them were civilians, but I also spotted a few on Navy personnel. I also spot a dog some men snuck into the picture in the upper left-hand quadrant.

Dan wondered what kind of ID tag it was. I’d never seen one before, so I asked Dennis Woolford who is a ranger at Farragut State Park and coauthor of a book on Farragut Naval Training Station. Dennis said it was an ID tag often used by civilians working on the base. He sent a photo (below) that showed several people who worked in Supply and Accounting wearing similar badges. Most wearing them were civilians, but I also spotted a few on Navy personnel. I also spot a dog some men snuck into the picture in the upper left-hand quadrant.

Published on July 08, 2024 04:00

July 7, 2024

Messing With Mother Nature

Countless species have been introduced into Idaho accidentally and intentionally, often to the detriment of native plants and animals. Exotic species can be an enormous problem because they often nudge out existing flora and fauna, taking over a niche and exploiting some advantage to become a nuisance, if not a threat. At the top of the list in Idaho is probably Cheatgrass. We know this today and go to great lengths to fight invasive species, such as zebra mussels. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game is one of several state agencies engaged in such fights.

It wasn’t always so.

In the early part of the 20th Century, Fish and Game—a much looser, less scientific entity then—went to some trouble to import an exotic species that is so common today that many people likely think it is native: the ring-necked pheasant, a native of Asia.

Pheasants have been in the U.S. since about 1773, though they didn’t really become common until the 1800s in the East. The birds with their extravagant tail feathers came West in 1881, but not under their own power. They were imported first into Oregon.

Idaho’s state game warden hatched a plan to hatch some pheasants in 1907, hoping to provide sport for hunters. There were likely a few pheasants in Idaho before that, perhaps moving in from Washington and Oregon. They may have also escaped or been set free from amateur breeding operations. A Lewiston hunting club imported some for the sport of its members. Farmers could buy pheasant eggs and read about how to raise pheasants in the Gem State Rural.

Other states had set up hatchery programs, so Idaho had some clues as to how to do it. Deputy State Game Warden B.T. Livingston set out on January 21 for Corvallis, Oregon to pick up 225 English and China pheasants. Forty pens had been set up on leased land on the G.A. Stevens farm just west of Boise. Each pen was 16 feet square and 6 ½ feet high. Wire netting kept the birds in while a few boards provided shelter from the sun and rain. To raise more chicks, pheasant eggs were gathered once they appeared and placed under regular chickens to hatch.

To avoid unnecessary ruffling of feathers, the Oregon Shortline train carrying the cargo of exotic birds made a special stop at the Stevens farm to unload its cargo rather than offloading them at the depot and hauling them back by wagon.

Even with careful care, the birds didn’t do very well that first year. The state hired a pheasant specialist to oversee the breeding operation. In subsequent years, additional hatcheries popped up across Southern Idaho to increase the release of the birds into the wild.

By 1910, pheasants were thriving and breeding rapidly. They were touted as a benefit to farmers because of the thousands of insects they eat. In 1911, “bird fancier” Roland Voddard, was travelling the state talking up pheasants to farmers. Several started raising and releasing them into their fields to go after grasshoppers, particularly. Voddard was quoted in the Idaho Statesman as saying, “The pheasants will form a mighty good advance army for the work in this state as they have elsewhere. They are not a crop-destroying bird and will not dig up the grain as will chickens if they are left in the fields.”

Well, that was one opinion. By 1918, the Farm Bureau had declared war on pheasants. Farmers in the Magic Valley had come to believe that the pest-eating function of pheasants was negligible, while their love of grain was a real problem. It was said that mother pheasants had a strategy of flying up through the stands of grain, knocking against the seeds with their wings, and scattering it to be consumed by their chicks.

That same year the Twin Falls Weekly News published a recipe to make a coal tar and linseed oil mix with which farmers could coat corn. This was said to make it unpalatable to pheasants and not affect its ability to germinate.

At the time, there was no hunting season on the birds. They were protected so that their population would increase. The Farm Bureau lobbied to establish a season to help control the pesky birds. Allowing hunters to shoot them had always been the plan, so hunting seasons for pheasants began.

Pheasants remain a popular game bird today. Fish and Game releases thousands of them into the wild every year. In 2023 they released 30,000 birds.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

It wasn’t always so.

In the early part of the 20th Century, Fish and Game—a much looser, less scientific entity then—went to some trouble to import an exotic species that is so common today that many people likely think it is native: the ring-necked pheasant, a native of Asia.

Pheasants have been in the U.S. since about 1773, though they didn’t really become common until the 1800s in the East. The birds with their extravagant tail feathers came West in 1881, but not under their own power. They were imported first into Oregon.

Idaho’s state game warden hatched a plan to hatch some pheasants in 1907, hoping to provide sport for hunters. There were likely a few pheasants in Idaho before that, perhaps moving in from Washington and Oregon. They may have also escaped or been set free from amateur breeding operations. A Lewiston hunting club imported some for the sport of its members. Farmers could buy pheasant eggs and read about how to raise pheasants in the Gem State Rural.

Other states had set up hatchery programs, so Idaho had some clues as to how to do it. Deputy State Game Warden B.T. Livingston set out on January 21 for Corvallis, Oregon to pick up 225 English and China pheasants. Forty pens had been set up on leased land on the G.A. Stevens farm just west of Boise. Each pen was 16 feet square and 6 ½ feet high. Wire netting kept the birds in while a few boards provided shelter from the sun and rain. To raise more chicks, pheasant eggs were gathered once they appeared and placed under regular chickens to hatch.

To avoid unnecessary ruffling of feathers, the Oregon Shortline train carrying the cargo of exotic birds made a special stop at the Stevens farm to unload its cargo rather than offloading them at the depot and hauling them back by wagon.

Even with careful care, the birds didn’t do very well that first year. The state hired a pheasant specialist to oversee the breeding operation. In subsequent years, additional hatcheries popped up across Southern Idaho to increase the release of the birds into the wild.

By 1910, pheasants were thriving and breeding rapidly. They were touted as a benefit to farmers because of the thousands of insects they eat. In 1911, “bird fancier” Roland Voddard, was travelling the state talking up pheasants to farmers. Several started raising and releasing them into their fields to go after grasshoppers, particularly. Voddard was quoted in the Idaho Statesman as saying, “The pheasants will form a mighty good advance army for the work in this state as they have elsewhere. They are not a crop-destroying bird and will not dig up the grain as will chickens if they are left in the fields.”

Well, that was one opinion. By 1918, the Farm Bureau had declared war on pheasants. Farmers in the Magic Valley had come to believe that the pest-eating function of pheasants was negligible, while their love of grain was a real problem. It was said that mother pheasants had a strategy of flying up through the stands of grain, knocking against the seeds with their wings, and scattering it to be consumed by their chicks.

That same year the Twin Falls Weekly News published a recipe to make a coal tar and linseed oil mix with which farmers could coat corn. This was said to make it unpalatable to pheasants and not affect its ability to germinate.

At the time, there was no hunting season on the birds. They were protected so that their population would increase. The Farm Bureau lobbied to establish a season to help control the pesky birds. Allowing hunters to shoot them had always been the plan, so hunting seasons for pheasants began.

Pheasants remain a popular game bird today. Fish and Game releases thousands of them into the wild every year. In 2023 they released 30,000 birds.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

Published on July 07, 2024 04:00

July 6, 2024

Floating the Natatorium

I’ve written several times about Boise’s Natatorium in the past, about its beauty, about its use of Boise’s naturally hot water, about a fight with the county prosecutor, and even about a holdup at the Nat.

Today, I’m writing about nearly nothing at all. I ran across this photo of a 1925 parade float featuring a dozen beauties promoting the Natatorium. I just thought you’d enjoy it. Notice how a couple of the women are “floating” chest-deep in the “water.”

Today, I’m writing about nearly nothing at all. I ran across this photo of a 1925 parade float featuring a dozen beauties promoting the Natatorium. I just thought you’d enjoy it. Notice how a couple of the women are “floating” chest-deep in the “water.”

Published on July 06, 2024 04:00

July 5, 2024

Fearless Crop Dusting

Farris Lind, famous for his humorous signs advertising his Stinker Stations in Idaho, was a man of many interests. He was a flight instructor in World War II. Following the war, he saw an opportunity in the availability of cheap, surplus airplanes. He started Fearless Farris Crop Dusting in Twin Falls. His original planes were surplus Piper Cubs, but he soon graduated to biplanes.

He had a thriving business for a few years, but it began to seem more of a liability than an asset when a series of crashes destroyed several planes and killed a couple of his pilots. Only Lloyds of London would insure the business. Lind eventually decided to focus on his gas stations and sold off his fleet of planes.

For more stories about Farris Lind, pick up a copy of the biography I wrote about him. You can buy a signed copy on this page, or order a copy of Fearless: Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk from Amazon or your local bookseller.

Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.

Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.  The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business.

The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business.

Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.

Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.

He had a thriving business for a few years, but it began to seem more of a liability than an asset when a series of crashes destroyed several planes and killed a couple of his pilots. Only Lloyds of London would insure the business. Lind eventually decided to focus on his gas stations and sold off his fleet of planes.

For more stories about Farris Lind, pick up a copy of the biography I wrote about him. You can buy a signed copy on this page, or order a copy of Fearless: Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk from Amazon or your local bookseller.

Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.

Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.  The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business.

The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business. Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.

Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.

Published on July 05, 2024 04:00

July 4, 2024

A Little Chautauqua History

Chautauquas in the Treasure Valley during the early part of the 20th Century offered so much education and entertainment that, described in today’s terms, they were Ted Talks, the Osher Institute, Toastmasters, Khan Academy, the Shakespeare Festival, Treefort, and the Cabin Readings and Conversations all rolled into one. Author Dick d’Easum wrote, “When Chautauqua was in flower it must be remembered that radio was in its infancy, television was unborn, and the automobile was a box mounted on punctures.”

These traveling congregations of culture were started by a Methodist minister, John Heyl Vincent, and a local businessman, Lewis Miller, at Chautauqua Lake, New York, in 1874. It began as an outdoor summer school for Sunday school teachers. With those religious roots, it’s unsurprising that many Chautauquas had religious elements, and were sometimes sponsored by various denominations. Most had ample entertainment and educational opportunities for those with more secular tastes.

Best known for their temporary manifestations, Chautauquas could be almost anything in a community. Chautauqua Circle women’s clubs popped up around the country to discuss books and better themselves in order to change the world. Inmates started Chautauqua Societies in prison for self-improvement.

Travelling Chautauquas operated much like a circus sideshow, rolling into town with massive tents and the accouterments of speakers, musicians, and entertainers. In smaller towns, they would stay for a day or two. They were usually the center of attention for a week in larger towns.

The first Idaho State Chautauqua took place in Boise in 1910. It lasted nine days. In the buildup to the event promoters extolled the quality of the speakers and the variety of entertainment. Sometimes calling it “the people’s university,” they described three divisions of each day.

The morning section featured classes and schools, mostly designed around domestic sciences and agriculture but also including athletic instruction, discussions about literature and history, and Bible classes. The University of Idaho supplied many of the instructors. In the afternoon, the heavier lectures for book lovers and those seeking knowledge took place. The evening was a time for entertainment from musical acts and theater companies.

As the event—encompassing July 4—grew nearer, local businesses began promoting it to their benefit. Tie-ins sold everything from lace curtains to building lots to flour with specials during Chautauqua.

The main speaker of the Chautauqua was to be Idaho Senator W.E. Borah, but there was speculation about who else might show up at the last minute. William Jennings Bryan was among the most popular speakers at such events across the country. Another was Dr. Russell Conwell, famous for his “Acres of Diamonds” speech, the point of which was that one could seek fortune far and wide yet miss the acres of diamonds in one’s own backyard. He delivered it more than 5,000 times.

The Chautauqua included ball games, cavalry drills, chalk art exhibitions, fireworks, readings, fashion shows, concerts, political speeches, exhibits, and more. The Chinese community in Boise was joyful because they were able to procure a “monster dragon” to wind along the parade route on the Fourth of July.

One feature of the celebration visible at the major entertainment venues was the Chautauqua salute. The waving of white handkerchiefs was a tradition that had grown from an event years earlier at the suggestion that a deaf speaker could not hear the applause of a crowd. The resulting flutter was a glorious sight since almost everyone carried a white handkerchief.

Chautauquas thrived in Idaho and elsewhere for a few more years, waning in the mid-twenties only as other forms of entertainment, especially radio, came to the forefront.

The end of the Chautauquas was perhaps foreshadowed in 1925 in Boise when former baseball player turned evangelist Billy Sunday deplored the rise of jazz music. Later, in that same tent, a Boise audience clapped “until their hands were sore” for a jazz performance.

These traveling congregations of culture were started by a Methodist minister, John Heyl Vincent, and a local businessman, Lewis Miller, at Chautauqua Lake, New York, in 1874. It began as an outdoor summer school for Sunday school teachers. With those religious roots, it’s unsurprising that many Chautauquas had religious elements, and were sometimes sponsored by various denominations. Most had ample entertainment and educational opportunities for those with more secular tastes.

Best known for their temporary manifestations, Chautauquas could be almost anything in a community. Chautauqua Circle women’s clubs popped up around the country to discuss books and better themselves in order to change the world. Inmates started Chautauqua Societies in prison for self-improvement.

Travelling Chautauquas operated much like a circus sideshow, rolling into town with massive tents and the accouterments of speakers, musicians, and entertainers. In smaller towns, they would stay for a day or two. They were usually the center of attention for a week in larger towns.

The first Idaho State Chautauqua took place in Boise in 1910. It lasted nine days. In the buildup to the event promoters extolled the quality of the speakers and the variety of entertainment. Sometimes calling it “the people’s university,” they described three divisions of each day.

The morning section featured classes and schools, mostly designed around domestic sciences and agriculture but also including athletic instruction, discussions about literature and history, and Bible classes. The University of Idaho supplied many of the instructors. In the afternoon, the heavier lectures for book lovers and those seeking knowledge took place. The evening was a time for entertainment from musical acts and theater companies.

As the event—encompassing July 4—grew nearer, local businesses began promoting it to their benefit. Tie-ins sold everything from lace curtains to building lots to flour with specials during Chautauqua.

The main speaker of the Chautauqua was to be Idaho Senator W.E. Borah, but there was speculation about who else might show up at the last minute. William Jennings Bryan was among the most popular speakers at such events across the country. Another was Dr. Russell Conwell, famous for his “Acres of Diamonds” speech, the point of which was that one could seek fortune far and wide yet miss the acres of diamonds in one’s own backyard. He delivered it more than 5,000 times.

The Chautauqua included ball games, cavalry drills, chalk art exhibitions, fireworks, readings, fashion shows, concerts, political speeches, exhibits, and more. The Chinese community in Boise was joyful because they were able to procure a “monster dragon” to wind along the parade route on the Fourth of July.

One feature of the celebration visible at the major entertainment venues was the Chautauqua salute. The waving of white handkerchiefs was a tradition that had grown from an event years earlier at the suggestion that a deaf speaker could not hear the applause of a crowd. The resulting flutter was a glorious sight since almost everyone carried a white handkerchief.

Chautauquas thrived in Idaho and elsewhere for a few more years, waning in the mid-twenties only as other forms of entertainment, especially radio, came to the forefront.

The end of the Chautauquas was perhaps foreshadowed in 1925 in Boise when former baseball player turned evangelist Billy Sunday deplored the rise of jazz music. Later, in that same tent, a Boise audience clapped “until their hands were sore” for a jazz performance.

Published on July 04, 2024 04:00

July 3, 2024

A Prison Yard Train-Jacking

As villains go John Gideon barely qualified. He didn’t kill anyone; he didn’t even hurt anyone. His claim to fame was that he probably participated in one of the heaviest heists of any Idaho bad guy. And that wasn’t even in Idaho.

He really should have been a more upstanding citizen with a biblical surname and an employee of a mine called the Golden Rule. However, as with so many, the golden part of that mine name caused his downfall.

In July 1905, a single bandit held up the Meadows-Warren stage. Hoping not to be recognized, the robber covered his entire face with a kerchief, not even bothering with eyeholes. The weave of the cloth was probably loose enough for him to see out without witness eyes seeing in well enough to identify him. To complete his outfit, the man brandished a mismatched pair of pistols.

The highwayman demanded that the driver of the coach “throw down the sack.” Pretending not to understand precisely what the bandit was after, the driver threw down a sack filled with bottles. This was not the exact sack the outlaw wanted, so he specified that it was the registered mail bag that interested him. The driver reluctantly tossed that to the ground, at which point the bandit told him to jump down and open it.

Once the contents were revealed, the bandit signaled for the stage to move on down the road.

The robber made off with $300 in cash and $1,200 in gold, most of which was the property of the Golden Rule operation. That would be the equivalent of about $40,000 today.

John Gideon did not wait a tick to start spending money fast enough to draw suspicion onto himself. No one could identify the bandit, but they had little trouble identifying a shirt and pistols found in Gideon’s possession.

Many men in Idaho’s criminal history paid for murder with a few years in jail. Gideon paid a little more for the theft of gold and currency. Robbing the mail is and was a federal offense. He was convicted of the crime and given a life sentence.

Following the trial, which took place in federal court in Moscow, Gideon came close to a moment of excitement. He confided in a cellmate that he had committed the crime, but he didn’t intend to pay for it. He planned to stomp the leg of the federal marshal assigned to transport him to prison at McNeill’s Island in the Puget Sound, a federal facility. It was a real threat because Gideon would be wearing an Oregon Boot on his foot. That was an iron device designed to make escape more difficult. It was heavy enough to break the bone of a man who might drop his guard. Fortunately, the cellmate told the story before the train left with Gideon, making the marshal sufficiently leery of that booted foot.

After spending about a year in the lockup at McNeill’s Island, Gideon was transferred to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was there that he found another day or two of fame.

On April 21, 1910, Gideon and five coconspirators overpowered a locomotive crew to make an escape. A switch engine was in the prison yard—probably not an uncommon occurrence, since there tracks to facilitate that. Using pistols carved for the occasion to look real, they pressed the barrels of the faux weapons into the necks of crew members. The engineer, valuing his life appropriately, crashed the steam engine through the closed prison gates.

The prisoners were not well-acquainted with train schedules, so did not know when or if an oncoming train might slam into them. One-by-one they jumped off the roaring train. They hadn’t gone more than a mile. All but one of them, including Gideon, were captured within hours.

The bold escape made headlines across the country, failed though it ultimately was. Perhaps the fame gave Gideon some satisfaction, though it clearly did not make up for a life in prison. He became, as they say, a model prisoner. In 1920, John Gideon walked away from the prison farm where he was working, never to be heard from again.

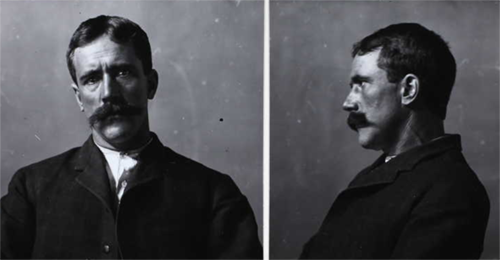

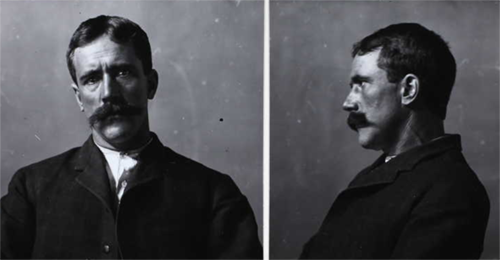

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

He really should have been a more upstanding citizen with a biblical surname and an employee of a mine called the Golden Rule. However, as with so many, the golden part of that mine name caused his downfall.

In July 1905, a single bandit held up the Meadows-Warren stage. Hoping not to be recognized, the robber covered his entire face with a kerchief, not even bothering with eyeholes. The weave of the cloth was probably loose enough for him to see out without witness eyes seeing in well enough to identify him. To complete his outfit, the man brandished a mismatched pair of pistols.

The highwayman demanded that the driver of the coach “throw down the sack.” Pretending not to understand precisely what the bandit was after, the driver threw down a sack filled with bottles. This was not the exact sack the outlaw wanted, so he specified that it was the registered mail bag that interested him. The driver reluctantly tossed that to the ground, at which point the bandit told him to jump down and open it.

Once the contents were revealed, the bandit signaled for the stage to move on down the road.

The robber made off with $300 in cash and $1,200 in gold, most of which was the property of the Golden Rule operation. That would be the equivalent of about $40,000 today.

John Gideon did not wait a tick to start spending money fast enough to draw suspicion onto himself. No one could identify the bandit, but they had little trouble identifying a shirt and pistols found in Gideon’s possession.

Many men in Idaho’s criminal history paid for murder with a few years in jail. Gideon paid a little more for the theft of gold and currency. Robbing the mail is and was a federal offense. He was convicted of the crime and given a life sentence.

Following the trial, which took place in federal court in Moscow, Gideon came close to a moment of excitement. He confided in a cellmate that he had committed the crime, but he didn’t intend to pay for it. He planned to stomp the leg of the federal marshal assigned to transport him to prison at McNeill’s Island in the Puget Sound, a federal facility. It was a real threat because Gideon would be wearing an Oregon Boot on his foot. That was an iron device designed to make escape more difficult. It was heavy enough to break the bone of a man who might drop his guard. Fortunately, the cellmate told the story before the train left with Gideon, making the marshal sufficiently leery of that booted foot.

After spending about a year in the lockup at McNeill’s Island, Gideon was transferred to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was there that he found another day or two of fame.

On April 21, 1910, Gideon and five coconspirators overpowered a locomotive crew to make an escape. A switch engine was in the prison yard—probably not an uncommon occurrence, since there tracks to facilitate that. Using pistols carved for the occasion to look real, they pressed the barrels of the faux weapons into the necks of crew members. The engineer, valuing his life appropriately, crashed the steam engine through the closed prison gates.

The prisoners were not well-acquainted with train schedules, so did not know when or if an oncoming train might slam into them. One-by-one they jumped off the roaring train. They hadn’t gone more than a mile. All but one of them, including Gideon, were captured within hours.

The bold escape made headlines across the country, failed though it ultimately was. Perhaps the fame gave Gideon some satisfaction, though it clearly did not make up for a life in prison. He became, as they say, a model prisoner. In 1920, John Gideon walked away from the prison farm where he was working, never to be heard from again.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

Published on July 03, 2024 04:00