Rick Just's Blog, page 19

July 2, 2024

Two Train Wrecks: One Cause?

In 1949, and again in 1951, head-on train crashes in Southern Idaho made headlines.

The first collision took place at 4:05 a.m. on January 30 in a lava rock cut-through about six miles west of American Falls. A westbound steam locomotive had been trying to climb the grade with little success, losing traction until the train came to a full stop. Crew members had reported their difficulty and noticed that a nearby signal had turned yellow. Engineer William Cramer wondered at first if a second locomotive had been sent from Pocatello to help them get up the grade. His story appeared in the Idaho State Journal on January 31.

“Then I saw the other freight about one half mile ahead of us as it rounded a curve,” Cramer said. “I knew it couldn’t stop in that short distance downhill, so I yelled to the fireman and brakeman, ‘get off, get off’

“They were working about five feet away, but they knew by my voice that we had to get off quick.”

The three jumped from the gangway of the cab and scrambled through about three feet of snow, getting about 30 feet from their abandoned engine.

“It seemed like Providence that we jumped on the south side,” Cramer said, “because most of the box cars piled up on the north side of our locomotive after the diesel telescoped into it.”

And there’s a point to remember. The stalled westbound engine was steam powered, while the speeding eastbound locomotive was powered by diesel.

The three trainmen in the diesel died in the smashup. The three who had jumped from the steam engine lived to tell the story.

Crews worked quickly to clear the tracks of the locomotives and 24 freight cars that had derailed. Railroad authorities set up a shuttle bus service from Pocatello to Shoshone to get some 400 people from scheduled passenger trains around the wreck. The line was cleared the next day.

Early estimates of the damage caused by the head-on collision were in excess of $1 million, making it Idaho’s most expensive train accident to date.

The second, eerily similar head-on collision between trains in Idaho occurred at Orchard, about 30 miles southeast of Boise on November 25, 1951. This time, both engines were diesel, and both were moving. The crew in the westbound freight spotted the oncoming engines and made an emergency stop. As that train was coming to a halt, Brakeman Ted Royter leapt from the four-engine train and ran to pull a switch that would route the eastbound engines onto a spur line. He arrived too late.

The grinding crash killed three crewmen in the lead eastbound engine and two in the westbound diesel cab. Of the 185 cars being pulled by the engines, 43 of them derailed, tearing up tracks as they tumbled and skidded. Three men in the caboose of the eastbound train escaped injury, as did two men in the westbound train’s caboose.

The sensational wreck, which happened on a Sunday, brought out carloads of people from Boise to see the pile-up. Police estimated that 5,000 people came to see the aftermath of the collision. A Boise camera club would later hold a special meeting to show photos club members had taken. (Note: If anyone has one, please post)

In both of the train wrecks all the crewmembers who might have shed some light on what happened perished in the collisions. There was no evidence that either of the engineers of the speeding trains had attempted to slow down.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) investigated both wrecks without coming to a conclusion about the cause of either. But after the second collision the ICC “indulged in speculation,” according to the April 21, 1952 issue of Railway Age, a trade publication for the railroad industry. The investigators thought conditions might have been right for the occupants of both cabs of the diesel-electric locomotives to have been overcome by toxic gases seeping in from the train’s exhaust.

This speculation was bolstered by testimony of the operator at the Orchard station who tried to signal the speeding train to stop. It blew through the station without slowing down. The station operator did not see anyone in the cab and noted that all the windows and doors were closed.

The ICC’s report included weather conditions that indicated that the exhaust from the train could have travelled along with the engines because of the speed and direction of winds, finding its way into air vents. Under those conditions carbon monoxide poisoning could happen quickly and without preliminary symptoms. An autopsy had not been conducted on the engineers in either crash, so determining the exact cause of their incapacity—if they were indeed unable to control the engines—could not be determined.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The first collision took place at 4:05 a.m. on January 30 in a lava rock cut-through about six miles west of American Falls. A westbound steam locomotive had been trying to climb the grade with little success, losing traction until the train came to a full stop. Crew members had reported their difficulty and noticed that a nearby signal had turned yellow. Engineer William Cramer wondered at first if a second locomotive had been sent from Pocatello to help them get up the grade. His story appeared in the Idaho State Journal on January 31.

“Then I saw the other freight about one half mile ahead of us as it rounded a curve,” Cramer said. “I knew it couldn’t stop in that short distance downhill, so I yelled to the fireman and brakeman, ‘get off, get off’

“They were working about five feet away, but they knew by my voice that we had to get off quick.”

The three jumped from the gangway of the cab and scrambled through about three feet of snow, getting about 30 feet from their abandoned engine.

“It seemed like Providence that we jumped on the south side,” Cramer said, “because most of the box cars piled up on the north side of our locomotive after the diesel telescoped into it.”

And there’s a point to remember. The stalled westbound engine was steam powered, while the speeding eastbound locomotive was powered by diesel.

The three trainmen in the diesel died in the smashup. The three who had jumped from the steam engine lived to tell the story.

Crews worked quickly to clear the tracks of the locomotives and 24 freight cars that had derailed. Railroad authorities set up a shuttle bus service from Pocatello to Shoshone to get some 400 people from scheduled passenger trains around the wreck. The line was cleared the next day.

Early estimates of the damage caused by the head-on collision were in excess of $1 million, making it Idaho’s most expensive train accident to date.

The second, eerily similar head-on collision between trains in Idaho occurred at Orchard, about 30 miles southeast of Boise on November 25, 1951. This time, both engines were diesel, and both were moving. The crew in the westbound freight spotted the oncoming engines and made an emergency stop. As that train was coming to a halt, Brakeman Ted Royter leapt from the four-engine train and ran to pull a switch that would route the eastbound engines onto a spur line. He arrived too late.

The grinding crash killed three crewmen in the lead eastbound engine and two in the westbound diesel cab. Of the 185 cars being pulled by the engines, 43 of them derailed, tearing up tracks as they tumbled and skidded. Three men in the caboose of the eastbound train escaped injury, as did two men in the westbound train’s caboose.

The sensational wreck, which happened on a Sunday, brought out carloads of people from Boise to see the pile-up. Police estimated that 5,000 people came to see the aftermath of the collision. A Boise camera club would later hold a special meeting to show photos club members had taken. (Note: If anyone has one, please post)

In both of the train wrecks all the crewmembers who might have shed some light on what happened perished in the collisions. There was no evidence that either of the engineers of the speeding trains had attempted to slow down.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) investigated both wrecks without coming to a conclusion about the cause of either. But after the second collision the ICC “indulged in speculation,” according to the April 21, 1952 issue of Railway Age, a trade publication for the railroad industry. The investigators thought conditions might have been right for the occupants of both cabs of the diesel-electric locomotives to have been overcome by toxic gases seeping in from the train’s exhaust.

This speculation was bolstered by testimony of the operator at the Orchard station who tried to signal the speeding train to stop. It blew through the station without slowing down. The station operator did not see anyone in the cab and noted that all the windows and doors were closed.

The ICC’s report included weather conditions that indicated that the exhaust from the train could have travelled along with the engines because of the speed and direction of winds, finding its way into air vents. Under those conditions carbon monoxide poisoning could happen quickly and without preliminary symptoms. An autopsy had not been conducted on the engineers in either crash, so determining the exact cause of their incapacity—if they were indeed unable to control the engines—could not be determined.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

Published on July 02, 2024 04:00

July 1, 2024

The Foundation of Boise

The Jellison brothers, C.O., C.L., and E.A., homesteaded near Table Rock in the 1890s with a stone and timber claim. What timber there might have been is long gone, but the stone from the quarries they established is part of Boise’s foundation. So to speak.

Table Rock sandstone makes up the greater part of the old Idaho State Penitentiary, and is used to good effect in the Emmanuel Lutheran Church, the Bown House, St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, the Union Block, Boise City National Bank, the United States Assay Office, Temple Beth Israel, the Borah Building, St. John’s Cathedral, and many others.

In 1906, the Capitol Commission, in charge of building Idaho’s statehouse, purchased one of the Jellison Brothers’ quarries on Table Rock in order to facilitate the construction of Idaho’s seat of government. The Idaho State Capitol is probably the most visible and dramatic use of Table Rock sandstone in Boise.

Sandstone from Table Rock found its way to major buildings all over the state, including the First Presbyterian Church in Idaho Falls, the Administration Building and Brink Hall at the University of Idaho, and Strahorn Hall at the College of Idaho in Caldwell.

Out of state the stone went to a building on the campus of Yale University and was a popular construction material for several downtown Portland buildings.

Working in a quarry is dangerous, and it was often left to inmates at the Idaho State Penitentiary in the early days. In 1903, two inmates were “hurled into eternity” while working on a troublesome boulder. The 10-foot-high rock, said to be 25 feet square, had a crack running through the middle of it. Workers set charges in the split, hoping to blow the rock apart. The blasts had little effect. Inmates John Stewart and William Maney scrambled up to the top of the boulder to clear away rubble for another go at it. That was when the rock came apart, splitting in two and throwing the men 40 feet down the side of the ridge. Neither survived.

Manpower and horsepower moved a lot of rock from the quarries. In 1912, a new owner of one of the quarries, put electrical power to work. Harry K. Fritchman, a former mayor of Boise, constructed a tramway on rails from the quarry to the Oregon Shortline Railroad, more than a mile away. You can still see the scar of the tramway line on the southeast side of Table Rock.

Ambitious as the tramway was, it was not nearly as aspirational as an idea born in 1907. That year one of the Jellison brothers announced that he was going to build a luxury hotel on top of Table Rock. He envisioned spectacular views from the resort which would rise up from the center of a 685-acre parcel appropriately landscaped. An extension from the Boise Valley Electric line would run to the top of Table Rock and circle around the perimeter. One can imagine geothermal water from nearby wells heating pools and spas in the development. The quarry would be stubbed into the line for transport of stone.

Alas, 1907 was also the year of the “Banker’s Panic,” which sank big money plans like a rock. So, Table Rock is not known today for its splendid hotel. Its history is written in rock, though, still providing sandstone for Boise and beyond.

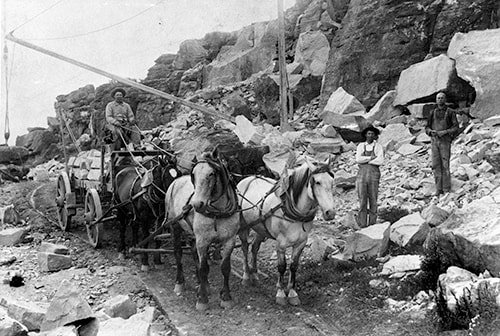

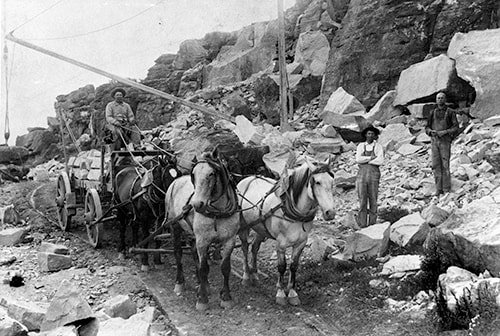

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

Table Rock sandstone makes up the greater part of the old Idaho State Penitentiary, and is used to good effect in the Emmanuel Lutheran Church, the Bown House, St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, the Union Block, Boise City National Bank, the United States Assay Office, Temple Beth Israel, the Borah Building, St. John’s Cathedral, and many others.

In 1906, the Capitol Commission, in charge of building Idaho’s statehouse, purchased one of the Jellison Brothers’ quarries on Table Rock in order to facilitate the construction of Idaho’s seat of government. The Idaho State Capitol is probably the most visible and dramatic use of Table Rock sandstone in Boise.

Sandstone from Table Rock found its way to major buildings all over the state, including the First Presbyterian Church in Idaho Falls, the Administration Building and Brink Hall at the University of Idaho, and Strahorn Hall at the College of Idaho in Caldwell.

Out of state the stone went to a building on the campus of Yale University and was a popular construction material for several downtown Portland buildings.

Working in a quarry is dangerous, and it was often left to inmates at the Idaho State Penitentiary in the early days. In 1903, two inmates were “hurled into eternity” while working on a troublesome boulder. The 10-foot-high rock, said to be 25 feet square, had a crack running through the middle of it. Workers set charges in the split, hoping to blow the rock apart. The blasts had little effect. Inmates John Stewart and William Maney scrambled up to the top of the boulder to clear away rubble for another go at it. That was when the rock came apart, splitting in two and throwing the men 40 feet down the side of the ridge. Neither survived.

Manpower and horsepower moved a lot of rock from the quarries. In 1912, a new owner of one of the quarries, put electrical power to work. Harry K. Fritchman, a former mayor of Boise, constructed a tramway on rails from the quarry to the Oregon Shortline Railroad, more than a mile away. You can still see the scar of the tramway line on the southeast side of Table Rock.

Ambitious as the tramway was, it was not nearly as aspirational as an idea born in 1907. That year one of the Jellison brothers announced that he was going to build a luxury hotel on top of Table Rock. He envisioned spectacular views from the resort which would rise up from the center of a 685-acre parcel appropriately landscaped. An extension from the Boise Valley Electric line would run to the top of Table Rock and circle around the perimeter. One can imagine geothermal water from nearby wells heating pools and spas in the development. The quarry would be stubbed into the line for transport of stone.

Alas, 1907 was also the year of the “Banker’s Panic,” which sank big money plans like a rock. So, Table Rock is not known today for its splendid hotel. Its history is written in rock, though, still providing sandstone for Boise and beyond.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

Published on July 01, 2024 04:00

June 30, 2024

Behive Burners

I have a special memory about beehive burners, sometimes called teepee or wigwam burners. Shaped something like each item they are named after, they were a common sight in 1960. My memory proves it.

My parents brought me along that summer on a trip that took us from our ranch on the Blackfoot River all the way to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and back. We had a near-new 1959 Ford pickup and a new slide-in camper with a sleeping compartment hanging over the cab. They were the latest invention. We saw exactly two of them on our two-week trip.

And that has what to do with beehive burners? I spotted one on our way north out of Idaho Falls. Pop told me that they were used to burn off wood waste from lumber mills. Not many miles down the road, we saw another, then another. My mother had bought 10-year-old me a book, or series of books, called I Spy to keep me entertained on the long road trip. I was already geared up to check off various objects I spied from chickens to radio antennas, so it made sense for me to start counting beehive burners.

I spent much of the road trip sprawled across the bed above the cab staring out of the tiny forward-facing windows, flouting future road rules. If I didn’t see a beehive burner first, my parents would pound on the roof to let me know there was one nearby. By the time we got back home I had tallied 50 of them.

Take that same trip today and you might see a few, mostly relics of bygone days not yet turned into scrap.

Beehive burners were typically fed by a conveyor belt that moved sawdust, woodchips, and snaggled branches into a hole near their top. The wood detritus fell onto the pile of burning debris below. On top of the burners was a smoke vent covered in steel mesh to help keep sparks from flying too far.

Air quality concerns have shut the things down in many places. They belch a lot of smoke. Lumber operations produce much less waste today, too, using what was once burned for particle board and mulch.

My parents brought me along that summer on a trip that took us from our ranch on the Blackfoot River all the way to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and back. We had a near-new 1959 Ford pickup and a new slide-in camper with a sleeping compartment hanging over the cab. They were the latest invention. We saw exactly two of them on our two-week trip.

And that has what to do with beehive burners? I spotted one on our way north out of Idaho Falls. Pop told me that they were used to burn off wood waste from lumber mills. Not many miles down the road, we saw another, then another. My mother had bought 10-year-old me a book, or series of books, called I Spy to keep me entertained on the long road trip. I was already geared up to check off various objects I spied from chickens to radio antennas, so it made sense for me to start counting beehive burners.

I spent much of the road trip sprawled across the bed above the cab staring out of the tiny forward-facing windows, flouting future road rules. If I didn’t see a beehive burner first, my parents would pound on the roof to let me know there was one nearby. By the time we got back home I had tallied 50 of them.

Take that same trip today and you might see a few, mostly relics of bygone days not yet turned into scrap.

Beehive burners were typically fed by a conveyor belt that moved sawdust, woodchips, and snaggled branches into a hole near their top. The wood detritus fell onto the pile of burning debris below. On top of the burners was a smoke vent covered in steel mesh to help keep sparks from flying too far.

Air quality concerns have shut the things down in many places. They belch a lot of smoke. Lumber operations produce much less waste today, too, using what was once burned for particle board and mulch.

Published on June 30, 2024 04:00

June 29, 2024

The Chunnel Builder

The Channel Tunnel between Great Britain and France is an engineering marvel that might have remained on the drawing board if it weren’t for the man who maintained his office in a converted home in Boise’s North End.

Jack Lemley graduated in 1960 from the University of Idaho with a degree in architecture. He worked for a few years as an engineer for a San Francisco company before moving his family to Boise in 1977 to take a job with Morrison Knudsen. He came on at MK as the executive vice president in charge of heavy construction. He managed major projects there until 1988 when he was passed over for the position of the CEO in favor of Bill Agee. One can’t help but wonder if MK would still be around if the decision had gone the other way.

Lemley’s resignation from MK came just in time for him to land the contract to supervise the construction of the Chunnel. It was about as big a job as they get. More than 15,000 people worked on the project. It resulted in two train tunnels and a service tunnel, more than 31 miles long and as deep 380 feet below sea level.

For his work on the project, Lemley was awarded the Order of Merit and Queen Elizabeth named him a Commander of the British Empire.

After the Chunnel was complete, Lemley became the CEO of U.S. Ecology in Houston. He moved the firm’s headquarters to Boise.

Even Boiseans who are well travelled probably see another project of Lemley’s much more often than they see the Chunnel. His firm designed and constructed the Idaho Water Center at the corner of Front and Broadway. It’s the home of the University of Idaho graduate engineering programs in Boise.

Lemley had his hand in dozens of major projects from Seattle’s Interstate-90 and Interstate-5 interchange to the Trans-Panama Pipeline.

A popular figure in Great Britain because of his success with the Chunnel project, Lemley was chosen to build the venues and infrastructure for the 2012 Olympics in London. Frustrated with political wrangling, he resigned the position in 2006.

Jack Lemley was inducted into the Idaho Hall of Fame in 1997 and into the Idaho Technology Council’s Hall of Fame in 2011. He died on November 29, 2021 at the age of 86.

Lemley’s son, Jim, is a manager of a different kind of big projects. He is a film producer best known for the Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Slayer.

Jack Lemley graduated in 1960 from the University of Idaho with a degree in architecture. He worked for a few years as an engineer for a San Francisco company before moving his family to Boise in 1977 to take a job with Morrison Knudsen. He came on at MK as the executive vice president in charge of heavy construction. He managed major projects there until 1988 when he was passed over for the position of the CEO in favor of Bill Agee. One can’t help but wonder if MK would still be around if the decision had gone the other way.

Lemley’s resignation from MK came just in time for him to land the contract to supervise the construction of the Chunnel. It was about as big a job as they get. More than 15,000 people worked on the project. It resulted in two train tunnels and a service tunnel, more than 31 miles long and as deep 380 feet below sea level.

For his work on the project, Lemley was awarded the Order of Merit and Queen Elizabeth named him a Commander of the British Empire.

After the Chunnel was complete, Lemley became the CEO of U.S. Ecology in Houston. He moved the firm’s headquarters to Boise.

Even Boiseans who are well travelled probably see another project of Lemley’s much more often than they see the Chunnel. His firm designed and constructed the Idaho Water Center at the corner of Front and Broadway. It’s the home of the University of Idaho graduate engineering programs in Boise.

Lemley had his hand in dozens of major projects from Seattle’s Interstate-90 and Interstate-5 interchange to the Trans-Panama Pipeline.

A popular figure in Great Britain because of his success with the Chunnel project, Lemley was chosen to build the venues and infrastructure for the 2012 Olympics in London. Frustrated with political wrangling, he resigned the position in 2006.

Jack Lemley was inducted into the Idaho Hall of Fame in 1997 and into the Idaho Technology Council’s Hall of Fame in 2011. He died on November 29, 2021 at the age of 86.

Lemley’s son, Jim, is a manager of a different kind of big projects. He is a film producer best known for the Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Slayer.

Published on June 29, 2024 04:00

June 28, 2024

The Idaho Buildings

If you think of the Idaho Building at 8th and Bannock in Boise as THE Idaho Building, you’re missing a bit of history. The downtown Boise Building’s story goes back to 1910, when it replaced a livery barn. The building, designed by Tortellotte & Co., made the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Today, we’re looking at three other Idaho Buildings that gained a measure of fame, none of them located in Idaho.

Giddy with statehood, Idaho was eager to participate in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was a celebration of the quadricentennial of Columbus’ “discovery” of the new world, albeit celebrated a year late.

The exhibition structure was designed by Spokane architect K.K. Cutter, but the Idaho Building was otherwise all Idaho. It used 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. The stonework came from Nez Perce County and the foundation veneer was lava rock from Southern Idaho, which had an abundance.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

Boise’s Columbian Club, which is active to this day, was named for its original mission, which was to furnish the Idaho Building.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City.” This huge log cabin drew attention to itself simply for not being white.

At the end of the exposition the building was taken down log by log and moved to… No, not some lake in Idaho. It was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

But we have no time to mourn the demise of that Idaho Building. There were other expositions ahead that beckoned to chambers of commerce in Idaho.

The next Idaho building went up in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Unlike the 1893 building, this one was modest in size. At 60 feet square, it was the smallest state exhibit at the celebration. Even so, it took second prize among those exhibits.

The hacienda style architecture of the ranch house was so popular the architect had more than 300 requests for the plans. With a roof of red clay tiles and an adobe exterior, it might as well have represented the Southwest. At the end of the exposition a Texan purchased the building for $6,940. It was moved piece-by-piece to San Antonio by rail. Rather than simply put it back together the buyer decided to make two houses out of it. The pair of homes are still standing side by side today on Beacon Hill.

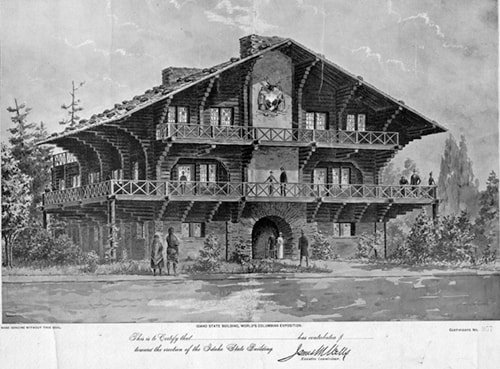

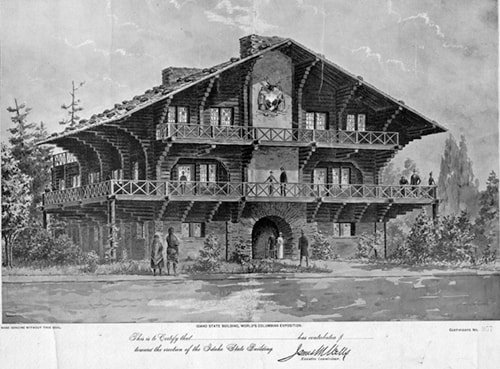

The third Idaho Building to appear in an exposition was closer to home. Idaho was represented at Portland’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition by a 100-foot by 60-foot building that resembled a Swiss chalet. Boise architects Wayland and Fennell designed it. Portland’s Idaho Building was noted for its striking colors, depicted in the hand-painted photo accompanying this article.

Idaho was generous with its $8,900 building, allowing Montana, Wyoming, and Nevada to use it for their state’s days at the fair. Several Idaho cities got use of the building on certain days, showing exhibits from Boise, Weiser, Pocatello, Wallace, Moscow, and Lewiston. The Idaho Statesman called the building “a cold-blooded business getter.” That was supposed to be a compliment.

The building generated a movement in Boise to have it brought to the city as a permanent exhibit. There was much excitement about this until it was pointed out that the Idaho Building was not meant to be a permanent structure. It wouldn’t stand being disassembled, transported, and reassembled, so the idea was abandoned. The structure, like many others at the exposition, was ultimately torn down.

So, this trio of Idaho buildings never made it to the state. We’ll have to be satisfied with the six-story Idaho Building in downtown Boise that was built to last, and hope it survives long into the future. It has already twice dodged a wrecking ball in the name of urban renewal.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Today, we’re looking at three other Idaho Buildings that gained a measure of fame, none of them located in Idaho.

Giddy with statehood, Idaho was eager to participate in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was a celebration of the quadricentennial of Columbus’ “discovery” of the new world, albeit celebrated a year late.

The exhibition structure was designed by Spokane architect K.K. Cutter, but the Idaho Building was otherwise all Idaho. It used 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. The stonework came from Nez Perce County and the foundation veneer was lava rock from Southern Idaho, which had an abundance.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

Boise’s Columbian Club, which is active to this day, was named for its original mission, which was to furnish the Idaho Building.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City.” This huge log cabin drew attention to itself simply for not being white.

At the end of the exposition the building was taken down log by log and moved to… No, not some lake in Idaho. It was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

But we have no time to mourn the demise of that Idaho Building. There were other expositions ahead that beckoned to chambers of commerce in Idaho.

The next Idaho building went up in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Unlike the 1893 building, this one was modest in size. At 60 feet square, it was the smallest state exhibit at the celebration. Even so, it took second prize among those exhibits.

The hacienda style architecture of the ranch house was so popular the architect had more than 300 requests for the plans. With a roof of red clay tiles and an adobe exterior, it might as well have represented the Southwest. At the end of the exposition a Texan purchased the building for $6,940. It was moved piece-by-piece to San Antonio by rail. Rather than simply put it back together the buyer decided to make two houses out of it. The pair of homes are still standing side by side today on Beacon Hill.

The third Idaho Building to appear in an exposition was closer to home. Idaho was represented at Portland’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition by a 100-foot by 60-foot building that resembled a Swiss chalet. Boise architects Wayland and Fennell designed it. Portland’s Idaho Building was noted for its striking colors, depicted in the hand-painted photo accompanying this article.

Idaho was generous with its $8,900 building, allowing Montana, Wyoming, and Nevada to use it for their state’s days at the fair. Several Idaho cities got use of the building on certain days, showing exhibits from Boise, Weiser, Pocatello, Wallace, Moscow, and Lewiston. The Idaho Statesman called the building “a cold-blooded business getter.” That was supposed to be a compliment.

The building generated a movement in Boise to have it brought to the city as a permanent exhibit. There was much excitement about this until it was pointed out that the Idaho Building was not meant to be a permanent structure. It wouldn’t stand being disassembled, transported, and reassembled, so the idea was abandoned. The structure, like many others at the exposition, was ultimately torn down.

So, this trio of Idaho buildings never made it to the state. We’ll have to be satisfied with the six-story Idaho Building in downtown Boise that was built to last, and hope it survives long into the future. It has already twice dodged a wrecking ball in the name of urban renewal.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on June 28, 2024 04:00

June 27, 2024

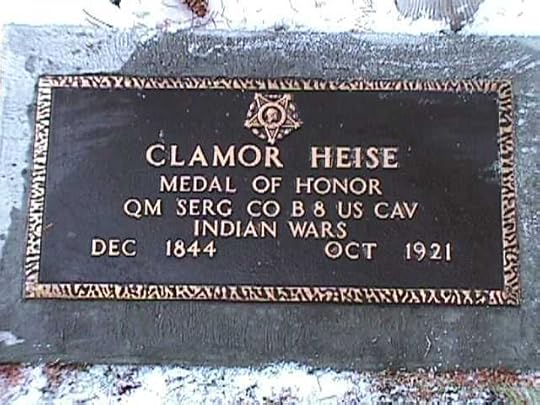

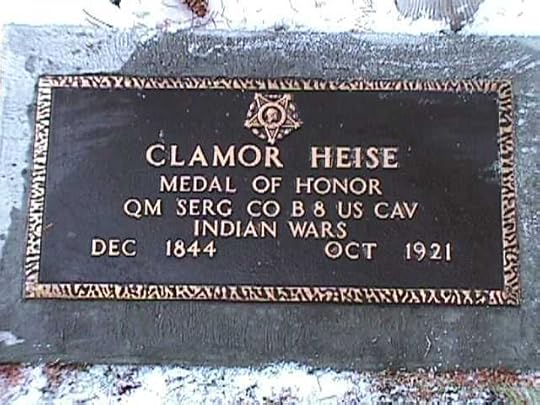

Medal of Honor Winner Heise

As I wrote in a previous post, Richard Clamor Heise was the founder of Heise Hot Springs in Eastern Idaho. He is buried on the grounds of the resort.

One thing about Heise that may come as a surprise to many is that he was a Medal of Honor winner. The details of the action for which he was awarded the medal are sketchy. He was recognized for his service between August 13 and October 31, 1868 during the Indian Wars in the vicinity of the Black Mountains of Arizona. He was cited for “Bravery in scouts and actions against Indians.”

Heise’s actions may have well been heroic, but one must remember that the Medal of Honor requirements were less strict inn the early days of its existence. Heise was one of 40 soldiers of Company B, 8th US Cavalry who were so honored for their actions during that time and at that place.

One thing about Heise that may come as a surprise to many is that he was a Medal of Honor winner. The details of the action for which he was awarded the medal are sketchy. He was recognized for his service between August 13 and October 31, 1868 during the Indian Wars in the vicinity of the Black Mountains of Arizona. He was cited for “Bravery in scouts and actions against Indians.”

Heise’s actions may have well been heroic, but one must remember that the Medal of Honor requirements were less strict inn the early days of its existence. Heise was one of 40 soldiers of Company B, 8th US Cavalry who were so honored for their actions during that time and at that place.

Published on June 27, 2024 04:00

June 26, 2024

Grays Lake

First, Grays Lake isn’t a lake. It’s a “high elevation, 22,000-acre bulrush marsh,” according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services webpage about the site in Southeastern Idaho. It’s located about 40 miles northeast of Soda Springs.

Much of the refuge was set aside in 1908 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes to use for an irrigation project. Water is drawn down annually in the spring for irrigation, taking out all but about six inches of water. In many years the whole marsh can dry up in the summer.

The unnatural hydrology isn’t always ideal for birds, but there have still been 250 species recorded at the refuge. About 100 of those are known to nest there. Notably, Grays Lake is typically home to about 200 nesting pairs of sandhill cranes. That’s the largest nesting population of the species in the world.

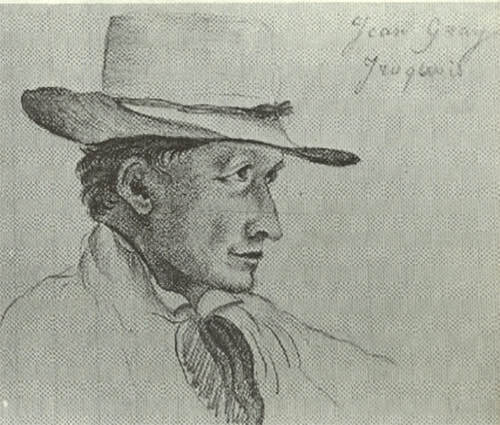

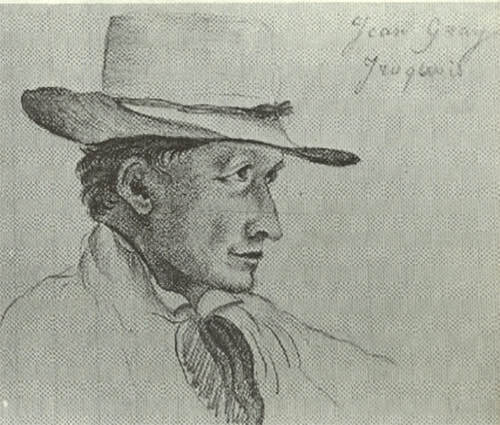

Grays Lake was named for mountain man John Grey. If you’re scratching your head about why he was named Grey and the lake is Grays Lake—with an a—there is much more to trouble your gray or grey hair over than that. The mountain man was also known as Ignace Hatchiorauquasha. That last name throws my spellchecker into a desolate land where it finds no road signs. Further, on many early maps Grays Lake is marked as Days Lake. Some thought it was named for John Day, an early trapper on the Astor Expedition. He has a town in Oregon named for him, so no sobbing.

But about that name, Hatchiorauquasha. It’s Iroquois. Gray/Grey/Hatchiorauquasha was half Scottish and half Iroquois. He chose the name Ignace because he considered St. Ignatius his patron saint.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Much of the refuge was set aside in 1908 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes to use for an irrigation project. Water is drawn down annually in the spring for irrigation, taking out all but about six inches of water. In many years the whole marsh can dry up in the summer.

The unnatural hydrology isn’t always ideal for birds, but there have still been 250 species recorded at the refuge. About 100 of those are known to nest there. Notably, Grays Lake is typically home to about 200 nesting pairs of sandhill cranes. That’s the largest nesting population of the species in the world.

Grays Lake was named for mountain man John Grey. If you’re scratching your head about why he was named Grey and the lake is Grays Lake—with an a—there is much more to trouble your gray or grey hair over than that. The mountain man was also known as Ignace Hatchiorauquasha. That last name throws my spellchecker into a desolate land where it finds no road signs. Further, on many early maps Grays Lake is marked as Days Lake. Some thought it was named for John Day, an early trapper on the Astor Expedition. He has a town in Oregon named for him, so no sobbing.

But about that name, Hatchiorauquasha. It’s Iroquois. Gray/Grey/Hatchiorauquasha was half Scottish and half Iroquois. He chose the name Ignace because he considered St. Ignatius his patron saint.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Published on June 26, 2024 04:00

June 25, 2024

The Highwayman, Part 5

And now, after four days of build-up about Ed Trafton, we come to the heist that made him famous. We’ve followed him in and out of prison, trailed behind his rustled horses, and seen him betray his own mother over and over. Now we learn of the “Lone Highwayman of Yellowstone Park.”

Ed Trafton was nearing 60 in 1915, an age when most men would rather settle down and put rustling behind them. He had purchased a farm in Rupert with some of the money he had stolen from his mother. But he wanted at least one more heist before he gave up his guns.

Yellowstone National Park was country he knew well. One thing he knew about it was that in 1915 wealthy tourists who stayed at various establishments in the park toured in relative luxury, riding in spiffed up stages pulled by teams of horses. The practice was for these stages to leave every few minutes on the tour. Spacing them out assured that the well-dressed travelers did not have to endure dust from the stage ahead.

On Wednesday, July 29, 1914, the first stage left Old Faithful Lodge at about 8 am. They rolled along enjoying the scenery until they were about nine miles from the lodge. That’s when a single gunman, his lower face covered by a neckerchief, stepped out in front of the coach holding a gun.

Guns were illegal in the park, so no one in or on the stage had one.

James C. Pinkston, who was visiting Yellowstone from Alabama with his wife and daughter described the incident to Salt Lake City reporters.

“We were just passing Shoshone point when suddenly the bandit appeared, stopped our driver and issue an order for the tourists to step out of the vehicle preparatory to holding a big ‘convention,’ over which he evidently intended to act as presiding minister.

“Naturally, we got out.

“Once on the ground, we had to deposit our money in a rude sack which he had furnished for the occasion. He told all of us to put in nothing but money, and if he saw any rings or other jewelry going in, he rudely threw it aside.”

The bandit herded all the passengers to a natural amphitheater and ordered them to sit. Soon, a second coach pulled up behind the first. The highwayman ordered everyone out. When they hesitated, according to Pinkston, the man said, “I bet if you heard a dinner bell ringing you wouldn’t hesitate like that. Now get out. We’re going to hold a calm peaceful convention and I want to enlist your aid.”

The dropping of cash into a sack was repeated, then repeated again when another coach pulled up.

When the fifth coach rumbled up, it presented a special opportunity. Two friends, Miss Estelle Hammond of London, and Miss Alice Cay of Sydney, Australia, were aboard. According to the Salt Lake Telegram the women had been visiting in untamed Australia and had arrived in the genteel United States just a few days before.

“We were never held up in wild Australia,” Miss Cay told the paper, which reported that she smiled about the adventure. She was able to take five photographs of the highwayman for her scrapbook.

Talking about her photographic escapade, Miss Cay said, “I was afraid to try at first. [Some men] said, ‘for heaven’s sake, don’t try it. He’ll shoot you.’ I tried, though, and really, I believe he rather like it. I believe he is, oh, what’s your American word for it, oh, yes, a flirt. I really do

“He was chivalrous to the extreme. He ordered us to be perfectly comfortable and commanded us in threatening tones to make ourselves comfortable, saying that if we didn’t enjoy the procedure, he would blow our bodies into atoms. Oh, it was thrilling.”

For a hold-up story that needed no exaggeration, this one received quite a bit. One report stated that the Yellowstone Highwayman had held up as many as 300 tourists in 40 coaches for a haul of as much as $20,000. The real story was incredible enough. He held up 165 passengers on 15 coaches. The driver of coach number 16 saw what was going on ahead, turned around, and warned the oncoming stages.

The bandit ended up with less than $1,000 in cash, and a little over $100 in jewelry. Apparently, he decided to keep a few of the ladies’ trinkets.

It wasn’t excellent detective work that led to Trafton’s capture. It was a woman. Not the woman who took pictures of him, but a woman he knew well.

A few months after the robbery, when Trafton was back in Rupert, Minnie caught him with another woman. For her revenge, she located the Yellowstone loot that he had hidden in a barn and took it to authorities. After Ed was arrested, Minnie filed for divorce and moved her family to Ogden, Utah. She eventually remarried.

After spending nine months in the Cheyenne jail, Trafton sat for days through a trial that included some 50 witnesses, photographs of him during the robbery, and positive identification of the jewelry found in the barn by those who owned it. It took the jury 30 minutes to reach a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to spend five years at the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

After Trafton was convicted, special agent Melrose, who pops up now and again in this story, told the press that the Yellowstone Bandit had been a suspect in the kidnapping of Alonzo Ernest Empy, which I’ve written about before, and was part of a plot to kidnap Joseph F. Smith, the nephew of the Church of Latter Day Saints founder Joseph Smith, then serving as the sixth president of the church. Trafton wasn’t involved in the Empy kidnapping, as far as we know. Melrose believed that three men were plotting to take Smith, hide him away somewhere in the Jackson Hole area, and hold him for $100,000 in ransom.

After just a few months in prison Trafton wrote a letter to Special Agent Melrose, claiming that he was at death’s door and asking to be moved from Kansas to the prison in Colorado where he had recently resided following the theft of his mother’s money.

“It’s a hard job to put a ‘bull elk,’ who has lived in the open most of his life, into a closet and expect him to ‘make it.’” Trafton wrote to Melrose. “You’ve done your part, as any man with red blood in his veins would do, when he swore allegiance to Uncle Sam. But give me a chance for my life. It’s all I’ve got that’s worthwhile.”

The line about Melrose doing his part referenced the fact that the special agent, whom Trafton had befriended, was the man who escorted him to Cheyenne for trial.

Whether Melrose attempted to honor Trafton’s request is unknown. For the first time in his life, Ed Harrington Trafton served out his entire sentence.

Trafton got out of Leavenworth in 1920. There was nothing for him anymore in Driggs. He thought Hollywood might be interested in his story, so he travelled there in 1922 with that glowing letter about his past exploits from Melrose in his pocket.

That his life ended while he was enjoying an ice cream soda seems every bit as absurd as his claim that he was the model for The Virginian. Trafton’s life story is worthy of a book, but probably not one in which he was the hero.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Ed Trafton was nearing 60 in 1915, an age when most men would rather settle down and put rustling behind them. He had purchased a farm in Rupert with some of the money he had stolen from his mother. But he wanted at least one more heist before he gave up his guns.

Yellowstone National Park was country he knew well. One thing he knew about it was that in 1915 wealthy tourists who stayed at various establishments in the park toured in relative luxury, riding in spiffed up stages pulled by teams of horses. The practice was for these stages to leave every few minutes on the tour. Spacing them out assured that the well-dressed travelers did not have to endure dust from the stage ahead.

On Wednesday, July 29, 1914, the first stage left Old Faithful Lodge at about 8 am. They rolled along enjoying the scenery until they were about nine miles from the lodge. That’s when a single gunman, his lower face covered by a neckerchief, stepped out in front of the coach holding a gun.

Guns were illegal in the park, so no one in or on the stage had one.

James C. Pinkston, who was visiting Yellowstone from Alabama with his wife and daughter described the incident to Salt Lake City reporters.

“We were just passing Shoshone point when suddenly the bandit appeared, stopped our driver and issue an order for the tourists to step out of the vehicle preparatory to holding a big ‘convention,’ over which he evidently intended to act as presiding minister.

“Naturally, we got out.

“Once on the ground, we had to deposit our money in a rude sack which he had furnished for the occasion. He told all of us to put in nothing but money, and if he saw any rings or other jewelry going in, he rudely threw it aside.”

The bandit herded all the passengers to a natural amphitheater and ordered them to sit. Soon, a second coach pulled up behind the first. The highwayman ordered everyone out. When they hesitated, according to Pinkston, the man said, “I bet if you heard a dinner bell ringing you wouldn’t hesitate like that. Now get out. We’re going to hold a calm peaceful convention and I want to enlist your aid.”

The dropping of cash into a sack was repeated, then repeated again when another coach pulled up.

When the fifth coach rumbled up, it presented a special opportunity. Two friends, Miss Estelle Hammond of London, and Miss Alice Cay of Sydney, Australia, were aboard. According to the Salt Lake Telegram the women had been visiting in untamed Australia and had arrived in the genteel United States just a few days before.

“We were never held up in wild Australia,” Miss Cay told the paper, which reported that she smiled about the adventure. She was able to take five photographs of the highwayman for her scrapbook.

Talking about her photographic escapade, Miss Cay said, “I was afraid to try at first. [Some men] said, ‘for heaven’s sake, don’t try it. He’ll shoot you.’ I tried, though, and really, I believe he rather like it. I believe he is, oh, what’s your American word for it, oh, yes, a flirt. I really do

“He was chivalrous to the extreme. He ordered us to be perfectly comfortable and commanded us in threatening tones to make ourselves comfortable, saying that if we didn’t enjoy the procedure, he would blow our bodies into atoms. Oh, it was thrilling.”

For a hold-up story that needed no exaggeration, this one received quite a bit. One report stated that the Yellowstone Highwayman had held up as many as 300 tourists in 40 coaches for a haul of as much as $20,000. The real story was incredible enough. He held up 165 passengers on 15 coaches. The driver of coach number 16 saw what was going on ahead, turned around, and warned the oncoming stages.

The bandit ended up with less than $1,000 in cash, and a little over $100 in jewelry. Apparently, he decided to keep a few of the ladies’ trinkets.

It wasn’t excellent detective work that led to Trafton’s capture. It was a woman. Not the woman who took pictures of him, but a woman he knew well.

A few months after the robbery, when Trafton was back in Rupert, Minnie caught him with another woman. For her revenge, she located the Yellowstone loot that he had hidden in a barn and took it to authorities. After Ed was arrested, Minnie filed for divorce and moved her family to Ogden, Utah. She eventually remarried.

After spending nine months in the Cheyenne jail, Trafton sat for days through a trial that included some 50 witnesses, photographs of him during the robbery, and positive identification of the jewelry found in the barn by those who owned it. It took the jury 30 minutes to reach a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to spend five years at the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

After Trafton was convicted, special agent Melrose, who pops up now and again in this story, told the press that the Yellowstone Bandit had been a suspect in the kidnapping of Alonzo Ernest Empy, which I’ve written about before, and was part of a plot to kidnap Joseph F. Smith, the nephew of the Church of Latter Day Saints founder Joseph Smith, then serving as the sixth president of the church. Trafton wasn’t involved in the Empy kidnapping, as far as we know. Melrose believed that three men were plotting to take Smith, hide him away somewhere in the Jackson Hole area, and hold him for $100,000 in ransom.

After just a few months in prison Trafton wrote a letter to Special Agent Melrose, claiming that he was at death’s door and asking to be moved from Kansas to the prison in Colorado where he had recently resided following the theft of his mother’s money.

“It’s a hard job to put a ‘bull elk,’ who has lived in the open most of his life, into a closet and expect him to ‘make it.’” Trafton wrote to Melrose. “You’ve done your part, as any man with red blood in his veins would do, when he swore allegiance to Uncle Sam. But give me a chance for my life. It’s all I’ve got that’s worthwhile.”

The line about Melrose doing his part referenced the fact that the special agent, whom Trafton had befriended, was the man who escorted him to Cheyenne for trial.

Whether Melrose attempted to honor Trafton’s request is unknown. For the first time in his life, Ed Harrington Trafton served out his entire sentence.

Trafton got out of Leavenworth in 1920. There was nothing for him anymore in Driggs. He thought Hollywood might be interested in his story, so he travelled there in 1922 with that glowing letter about his past exploits from Melrose in his pocket.

That his life ended while he was enjoying an ice cream soda seems every bit as absurd as his claim that he was the model for The Virginian. Trafton’s life story is worthy of a book, but probably not one in which he was the hero.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Published on June 25, 2024 04:00

June 24, 2024

The Highwayman, Part 4

Yesterday we left Ed and Minnie Trafton when they were Teton Valley entrepreneurs, shearing and dipping ship, running a boarding house and saloon, and possibly expediting the transfer of livestock from one hapless owner to another without benefit of paperwork.

The sideline rustling business, for which Ed had already served a couple of sentences in the Idaho State Penitentiary, was starting to bring a little heat onto the Traftons. Some ranchers looked upon their herd shrinkage as an annoyance and part of the cost of doing business. But a couple of the cattlemen had begun to plot to catch Ed in the act.

It may have been good luck for Ed that his mother asked for his help in 1909, providing a good excuse to leave Teton Valley and let things cool down.

Annie Knight was the same mother from whom Ed had stolen money, a ham, and a horse for his grubstake in a failed attempt to get rich mining for gold in the Black Hills many years earlier. She was the same mother who allegedly bribed officials to get him out of prison.

Trafton’s forgiving mother asked he and Minnie to move to Denver to help her with her boarding house. Her husband, Ed’s stepfather, James Knight, was in poor health.

It was while running the Denver boarding house that Ed met Special Agent James Melrose, the U.S. Justice Department official who would one day write the glowing letter of reference that was found on Trafton when he died.

Melrose was fascinated by Trafton’s stories of the wild West. He learned that, according Trafton, Ed was the inspiration for Owen Wister’s lead character in The Virginian. He heard tales of gunfights and cattle drives and narrow escapes. Melrose ate it up. To be fair, Trafton probably gave short shrift to his rustling exploits, if he mentioned them at all.

The special agent was so gullible, he probably didn’t even notice that Trafton was having an affair with Melrose’s wife in his spare time.

But all good things must end. In early 1910, James Knight passed away, leaving his wife Annie to collect on a $10,000 insurance policy.

Not trusting banks, Annie buried the money. Her loving son spent some time looking for it, to no avail. Eventually, Annie decided to trust a bank and to trust Ed Trafton to deposit the money.

Stand by for a big shock. Ed did not deposit the money. Writer Wayne Moss interviewed a grandson of Trafton’s to get family details for a story that ran in the Teton Valley Times in 2015. As Moss related it, Ed buried $4,000 in his own hiding spot in the backyard, hid $3,000 in a dresser drawer, intending it as a gift for his wife, and secreted away the remaining $3,000 under some floorboards.

Ed told his mother he had been robbed. No wait, that wasn’t it, he’d forgotten the money in a satchel he left on a trolly.

Annie Knight was not swayed by either story. She called the police, and they quickly found the $3,000 in Minnie’s drawer. Lickety split Ed and Minnie were behind bars.

Ed was convicted and sentenced to from 5 to 8 years in prison. Minnie, who protested her innocence, was convicted and sentenced to from 3 to 5 years. They would both reside in the Colorado State Penitentiary for the next couple of years.

The Trafton’s eldest daughter, Anna—probably lovingly named after the woman Ed stole $10,000 from—removed the $3,000 from beneath the floorboards and took her siblings to Pocatello to live. Minnie would join them upon her release in 1912. They opened a boarding house there.

Ed, who had a way of getting reduced sentences, was released in 1913. He dug up the remaining $4,000, collected his wife in Pocatello, and moved to Rupert where he was purchased a farm. (Note that some accounts say he worked on a Rupert farm, but did not own it)

Nearing 60, his thieving days were over.

Just kidding. Come back tomorrow for the final chapter in the story of Ed Trafton.

[image error] Ed Harington Trafton's Idaho State Penitentiary booking photo.

The sideline rustling business, for which Ed had already served a couple of sentences in the Idaho State Penitentiary, was starting to bring a little heat onto the Traftons. Some ranchers looked upon their herd shrinkage as an annoyance and part of the cost of doing business. But a couple of the cattlemen had begun to plot to catch Ed in the act.

It may have been good luck for Ed that his mother asked for his help in 1909, providing a good excuse to leave Teton Valley and let things cool down.

Annie Knight was the same mother from whom Ed had stolen money, a ham, and a horse for his grubstake in a failed attempt to get rich mining for gold in the Black Hills many years earlier. She was the same mother who allegedly bribed officials to get him out of prison.

Trafton’s forgiving mother asked he and Minnie to move to Denver to help her with her boarding house. Her husband, Ed’s stepfather, James Knight, was in poor health.

It was while running the Denver boarding house that Ed met Special Agent James Melrose, the U.S. Justice Department official who would one day write the glowing letter of reference that was found on Trafton when he died.

Melrose was fascinated by Trafton’s stories of the wild West. He learned that, according Trafton, Ed was the inspiration for Owen Wister’s lead character in The Virginian. He heard tales of gunfights and cattle drives and narrow escapes. Melrose ate it up. To be fair, Trafton probably gave short shrift to his rustling exploits, if he mentioned them at all.

The special agent was so gullible, he probably didn’t even notice that Trafton was having an affair with Melrose’s wife in his spare time.

But all good things must end. In early 1910, James Knight passed away, leaving his wife Annie to collect on a $10,000 insurance policy.

Not trusting banks, Annie buried the money. Her loving son spent some time looking for it, to no avail. Eventually, Annie decided to trust a bank and to trust Ed Trafton to deposit the money.

Stand by for a big shock. Ed did not deposit the money. Writer Wayne Moss interviewed a grandson of Trafton’s to get family details for a story that ran in the Teton Valley Times in 2015. As Moss related it, Ed buried $4,000 in his own hiding spot in the backyard, hid $3,000 in a dresser drawer, intending it as a gift for his wife, and secreted away the remaining $3,000 under some floorboards.

Ed told his mother he had been robbed. No wait, that wasn’t it, he’d forgotten the money in a satchel he left on a trolly.

Annie Knight was not swayed by either story. She called the police, and they quickly found the $3,000 in Minnie’s drawer. Lickety split Ed and Minnie were behind bars.

Ed was convicted and sentenced to from 5 to 8 years in prison. Minnie, who protested her innocence, was convicted and sentenced to from 3 to 5 years. They would both reside in the Colorado State Penitentiary for the next couple of years.

The Trafton’s eldest daughter, Anna—probably lovingly named after the woman Ed stole $10,000 from—removed the $3,000 from beneath the floorboards and took her siblings to Pocatello to live. Minnie would join them upon her release in 1912. They opened a boarding house there.

Ed, who had a way of getting reduced sentences, was released in 1913. He dug up the remaining $4,000, collected his wife in Pocatello, and moved to Rupert where he was purchased a farm. (Note that some accounts say he worked on a Rupert farm, but did not own it)

Nearing 60, his thieving days were over.

Just kidding. Come back tomorrow for the final chapter in the story of Ed Trafton.

[image error] Ed Harington Trafton's Idaho State Penitentiary booking photo.

Published on June 24, 2024 04:00

June 23, 2024

The Highwayman, Part 3

As I wrote in previous posts, Ed Harrington Trafton was an outlaw and entrepreneur.

His escapades as the former were often ignored by locals while his business side was praised.

Trafton received a pardon from his 25-year sentence for horse stealing, serving just two. He got out of prison in 1889 and returned to the Teton Valley.

It wasn’t long until Ed found, inexplicably, that he had a surplus of horses that he needed to get rid of. He herded them to Hyrum, Utah where the locals wouldn’t recognize the altered brands. There he met 18-year-old Minnie Lyman. Ed, now 34, proposed to the daughter of the gentleman who was buying the horses.

The newlyweds moved to Colter Bay on Jackson Lake and set up their new home. Some sources say their main business there was working with rustlers to move stolen horses and cattle. It was at the place on Jackson Lake where Owen Wister, author of The Virginian, may have spent some time with Trafton.

After a few years at Jackson Lake, the Traftons moved back to the Teton Valley where their five children, four girls and a boy, were born.

In 1899, Ed Trafton was arrested for dynamiting the Brandon Building in St Anthony, which was under construction, allegedly acting as a hired bomber. The bomb broke windows nearby and damaged a lawyer’s office but did little damage to the stone structure that was the apparent target. Trafton, if he was the incompetent bomber, was acquitted of those charges.

1901 was a memorable year for the Traftons. In February, the family was startled by a bullet smashing through the window of their home and grazing Minnie. How could anyone have a beef with such a nice family?

Later that year, Trafton was caught rustling beef, again, and was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. He got out in two and returned to the Teton Valley where he seemed to focus more on his business side for a few years, including the boarding house and restaurant.

Trafton’s sheep shearing business was one of large scale. In 1904 he told the Teton Peak newspaper in St. Anthony that he expected to shear 125,000 sheep and noted that dipping vats would also be available.

Exciting as sheep dipping is, we’re going to leave the tale there for a day. Come back tomorrow when we get to the stories that made the sheep dipper famous.

[image error] Trafton was a well-known sheep dipper in the Teton Valley.

His escapades as the former were often ignored by locals while his business side was praised.

Trafton received a pardon from his 25-year sentence for horse stealing, serving just two. He got out of prison in 1889 and returned to the Teton Valley.

It wasn’t long until Ed found, inexplicably, that he had a surplus of horses that he needed to get rid of. He herded them to Hyrum, Utah where the locals wouldn’t recognize the altered brands. There he met 18-year-old Minnie Lyman. Ed, now 34, proposed to the daughter of the gentleman who was buying the horses.

The newlyweds moved to Colter Bay on Jackson Lake and set up their new home. Some sources say their main business there was working with rustlers to move stolen horses and cattle. It was at the place on Jackson Lake where Owen Wister, author of The Virginian, may have spent some time with Trafton.

After a few years at Jackson Lake, the Traftons moved back to the Teton Valley where their five children, four girls and a boy, were born.

In 1899, Ed Trafton was arrested for dynamiting the Brandon Building in St Anthony, which was under construction, allegedly acting as a hired bomber. The bomb broke windows nearby and damaged a lawyer’s office but did little damage to the stone structure that was the apparent target. Trafton, if he was the incompetent bomber, was acquitted of those charges.

1901 was a memorable year for the Traftons. In February, the family was startled by a bullet smashing through the window of their home and grazing Minnie. How could anyone have a beef with such a nice family?

Later that year, Trafton was caught rustling beef, again, and was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. He got out in two and returned to the Teton Valley where he seemed to focus more on his business side for a few years, including the boarding house and restaurant.

Trafton’s sheep shearing business was one of large scale. In 1904 he told the Teton Peak newspaper in St. Anthony that he expected to shear 125,000 sheep and noted that dipping vats would also be available.

Exciting as sheep dipping is, we’re going to leave the tale there for a day. Come back tomorrow when we get to the stories that made the sheep dipper famous.

[image error] Trafton was a well-known sheep dipper in the Teton Valley.

Published on June 23, 2024 04:00