Rick Just's Blog, page 20

June 22, 2024

The Highwayman, Part 2

Yesterday we started the story of Edwin B. Trafton with an account of his death and how his life was the possible inspiration for the novel The Virginian, by Owen Wister. Today we’ll look at the high and low points of that life. Mostly the low.

Born in New Brunswick, Canada in 1857 to immigrants from Liverpool, Edwin Burnham Trafton seemed bent on outlawry from an early age. A few years after his father’s death and his mother Annie’s marriage to a neighbor, James Knight, Ed found himself in Denver, a juvenile delinquent who had a habit of appropriating guns from the residents of his mother’s boarding house.

At around age 20 Ed decided to set out on his own. He left Annie Knight a note, stole $40, a smoked ham, and her best horse, and took off for the Black Hills in search of gold.

His taste for gold never left him, but mining it was not his preferred method of acquisition.

After striking out in the Black Hills gold rush, Trafton settled in the Teton Valley near present day Driggs in 1878. The following year he homesteaded in the valley along Milk Creek and started a variety of endeavors, including sheep shearing, and eventually operating a small store that included a saloon and boarding house.

Ed Trafton lived parallel lives. He ran his legitimate businesses while at the same time robbing other businesses and stealing livestock. This seemed to be widely known and widely tolerated.

Arrested for horse stealing in 1887, Ed was sent to the jail in Blackfoot to await trial along with his alleged partner in the crime, Lem Nickerson. The theft had occurred in the Teton Valley, but Blackfoot was the county seat of a much larger Bingham county at that time. Ed was going by the name Harrington then, but I will continue to call him Trafton to help readers through a confusing story.

Nickerson’s wife was visiting regularly in the weeks before the trial. She got to be such a regular visitor that the guards let down their, well, guard. She slipped a long six-shooter into the pocket of her spouse during visitation.

Soon after noon on June 22, 1887, the leisurely escape began. Guard William High looked down the hall to the jail and saw that he was also looking down the barrel of a 45. Nickerson demanded that the guard “throw up your hands and deliver me the keys to this jail or down and out you go.”

Trafton and Nickerson overpowered another deputy on duty and locked the two officers in a cell. The accused horse thieves poked around the county offices and found three other men to lock away.

Then it was time for Ed Harrington Trafton to pen a little note to Judge Hayes, who he was scheduled to appear before: “We are off for the hills and the mountains which we love so dearly. We are familiar with the mountain trails and the officers cannot catch us, for we are well mounted and well armed. You cannot get a crack at me this time and when I meet you again it will be in hell.”

Perhaps while Trafton was working on that note, Nickerson strolled from the courthouse to where his family was staying in Blackfoot to retrieve some horses stashed there by his brother, bringing them back to the jail.

It was nearing dusk by the time the men were ready to make their escape.

A Pocatello man named Hughes, accused of murder, was also locked up in the jail. Nickerson and Trafton freed him, perhaps to provide an additional diversion to pursuers. Hughes was a black man. He was aware that Indians often sympathized with dark-skinned people who were in trouble with white men, so he made his way to a scattering of tepees south of town. To his delight, the Indians did take him in, putting ocher on his face and giving him native clothes to wear. He hung around Blackfoot in that disguise for a few days before hopping a train to Montana.

While Hughes was making friends with the Indians, the other escapees made their way to Willow Creek in the Blackfoot Mountains where they looked up an old acquaintance, Johnnie Heath. They had a leisurely breakfast with him the next day, then headed out. Trafton and Nickerson made their way for several days through the Wolverine country, and eventually headed north, planning to cross the Snake River near present day Heise Hot Springs. High water made the crossing too dangerous. With a posse now in hot pursuit, Trafton and Nickerson took refuge in the willows on Pool Island.

Law enforcement officials from several towns came together to smoke out the escapees. A several days siege ensued, the result of which was that Trafton was shot in the foot and both men surrendered.

Their fellow escapee, Hughes, was recognized in Butte, Montana and brought back to Blackfoot to face execution days later.

It’s likely that Ed Harrington Trafton regretted his snarky note to Judge Hayes. “Well, Mr. Harrington,” the judge said, “we have met again—but not in hell!” He then sentenced Harrington/Trafton to 25 years at hard labor in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Warden C.E. Arney, who took Trafton in at the penitentiary related a story years later that may shed some light on how the man led his parallel lives of businessman and outlaw. “Harrington was a clever fellow and aside from his outlaw traits was a pleasant companion, interesting and truthful. These traits elicited sympathy for him, and petitions soon circulated for his release. In 1888 I saw [him] in the penitentiary and in 1891 when I was running a newspaper in Rexburg, he was pardoned and I saw him in the wild pose of a cowboy, once more breathing the free mountain air, and astride a well gaited cayuse, ride down the streets of Rexburg wildly waving his broad brimmed hat at the friends who greeted him from the streets and store buildings, stopping only long enough to shake hands with those who had befriended him and then hurrying on to his old haunts in the Teton Basin and Jackson Hole Districts.”

Trafton had gotten out in two years, perhaps with the help of his mother who may have bribed someone. If so, she would come to regret that.

Tomorrow I’ll continue the story of the outlaw/entrepreneur.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

Born in New Brunswick, Canada in 1857 to immigrants from Liverpool, Edwin Burnham Trafton seemed bent on outlawry from an early age. A few years after his father’s death and his mother Annie’s marriage to a neighbor, James Knight, Ed found himself in Denver, a juvenile delinquent who had a habit of appropriating guns from the residents of his mother’s boarding house.

At around age 20 Ed decided to set out on his own. He left Annie Knight a note, stole $40, a smoked ham, and her best horse, and took off for the Black Hills in search of gold.

His taste for gold never left him, but mining it was not his preferred method of acquisition.

After striking out in the Black Hills gold rush, Trafton settled in the Teton Valley near present day Driggs in 1878. The following year he homesteaded in the valley along Milk Creek and started a variety of endeavors, including sheep shearing, and eventually operating a small store that included a saloon and boarding house.

Ed Trafton lived parallel lives. He ran his legitimate businesses while at the same time robbing other businesses and stealing livestock. This seemed to be widely known and widely tolerated.

Arrested for horse stealing in 1887, Ed was sent to the jail in Blackfoot to await trial along with his alleged partner in the crime, Lem Nickerson. The theft had occurred in the Teton Valley, but Blackfoot was the county seat of a much larger Bingham county at that time. Ed was going by the name Harrington then, but I will continue to call him Trafton to help readers through a confusing story.

Nickerson’s wife was visiting regularly in the weeks before the trial. She got to be such a regular visitor that the guards let down their, well, guard. She slipped a long six-shooter into the pocket of her spouse during visitation.

Soon after noon on June 22, 1887, the leisurely escape began. Guard William High looked down the hall to the jail and saw that he was also looking down the barrel of a 45. Nickerson demanded that the guard “throw up your hands and deliver me the keys to this jail or down and out you go.”

Trafton and Nickerson overpowered another deputy on duty and locked the two officers in a cell. The accused horse thieves poked around the county offices and found three other men to lock away.

Then it was time for Ed Harrington Trafton to pen a little note to Judge Hayes, who he was scheduled to appear before: “We are off for the hills and the mountains which we love so dearly. We are familiar with the mountain trails and the officers cannot catch us, for we are well mounted and well armed. You cannot get a crack at me this time and when I meet you again it will be in hell.”

Perhaps while Trafton was working on that note, Nickerson strolled from the courthouse to where his family was staying in Blackfoot to retrieve some horses stashed there by his brother, bringing them back to the jail.

It was nearing dusk by the time the men were ready to make their escape.

A Pocatello man named Hughes, accused of murder, was also locked up in the jail. Nickerson and Trafton freed him, perhaps to provide an additional diversion to pursuers. Hughes was a black man. He was aware that Indians often sympathized with dark-skinned people who were in trouble with white men, so he made his way to a scattering of tepees south of town. To his delight, the Indians did take him in, putting ocher on his face and giving him native clothes to wear. He hung around Blackfoot in that disguise for a few days before hopping a train to Montana.

While Hughes was making friends with the Indians, the other escapees made their way to Willow Creek in the Blackfoot Mountains where they looked up an old acquaintance, Johnnie Heath. They had a leisurely breakfast with him the next day, then headed out. Trafton and Nickerson made their way for several days through the Wolverine country, and eventually headed north, planning to cross the Snake River near present day Heise Hot Springs. High water made the crossing too dangerous. With a posse now in hot pursuit, Trafton and Nickerson took refuge in the willows on Pool Island.

Law enforcement officials from several towns came together to smoke out the escapees. A several days siege ensued, the result of which was that Trafton was shot in the foot and both men surrendered.

Their fellow escapee, Hughes, was recognized in Butte, Montana and brought back to Blackfoot to face execution days later.

It’s likely that Ed Harrington Trafton regretted his snarky note to Judge Hayes. “Well, Mr. Harrington,” the judge said, “we have met again—but not in hell!” He then sentenced Harrington/Trafton to 25 years at hard labor in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Warden C.E. Arney, who took Trafton in at the penitentiary related a story years later that may shed some light on how the man led his parallel lives of businessman and outlaw. “Harrington was a clever fellow and aside from his outlaw traits was a pleasant companion, interesting and truthful. These traits elicited sympathy for him, and petitions soon circulated for his release. In 1888 I saw [him] in the penitentiary and in 1891 when I was running a newspaper in Rexburg, he was pardoned and I saw him in the wild pose of a cowboy, once more breathing the free mountain air, and astride a well gaited cayuse, ride down the streets of Rexburg wildly waving his broad brimmed hat at the friends who greeted him from the streets and store buildings, stopping only long enough to shake hands with those who had befriended him and then hurrying on to his old haunts in the Teton Basin and Jackson Hole Districts.”

Trafton had gotten out in two years, perhaps with the help of his mother who may have bribed someone. If so, she would come to regret that.

Tomorrow I’ll continue the story of the outlaw/entrepreneur.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

Published on June 22, 2024 04:00

June 21, 2024

The Highwayman, Part 1

The first of a five-part story.

Starting at the beginning is so conventional in storytelling. In recognition of the irregular nature of this tale’s subject, I’m going to start at the end. On top of that, I’m going to start with something that doesn’t even seem to relate to the subject.

I always thought it odd that the book many scholars consider the first Western novel was called The Virginian. It is set in Wyoming where the lead character, who was born in Virginia, works as a cowboy. He is never referred to by name, only as The Virginian.

The author, at first glance, seems like an odd one to have invented the genre. Owen Wister was born in Philadelphia, attended schools in Britain and Switzerland, and ultimately graduated from Harvard, where he was a Hasty Pudding member. He studied music for a couple of years in a Paris conservatory before turning to the law, and eventually to writing.

Wister became friends with Teddy Roosevelt and, like Roosevelt, spent many summers in the West, mostly in Wyoming.

The Virginian was a monster hit, reprinted fourteen times in 1902, the year it came out. It remains one of the 50 top-selling works of fiction.

So, the author was from Philadelphia, the book was set in Wyoming, where they named a mountain after Wister, and this is a blog about Idaho history. What’s the connection?

Possibly none. However, one-time Idaho State Penitentiary Warden C.E. Arney insisted that Ed Harrington Trafton, one-time inmate of his prison, was the man Wister used as his model for the hero in Wister’s story. That according to an article in the Idaho Statesman of September 17, 1922.

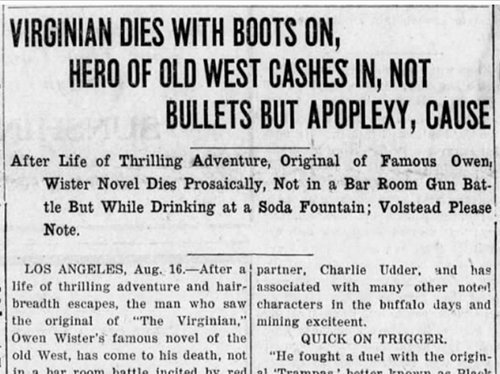

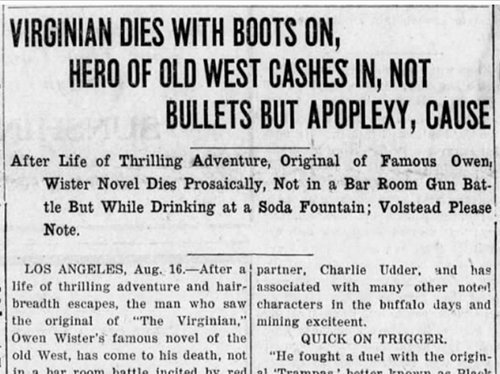

It wasn’t just the Statesman making this claim. On August 16, 1922, the Los Angeles Times ran a story with the stacked headline:

“THE VIRGINIAN”

DIES SUDDENLY

---

Owen Wister Novel Hero

Was Real Pioneer

---

Blazed First Trails Into

Jackson Hole Country

---

Ed Trafton Whacked Bulls

With Buffalo Bill

As proof of the connection, the Times offered a letter of introduction found on Trafton and written by James W. Melrose, who was a special agent in the Department of Justice for 16 years in Denver.

“This will introduce Edwin B. Trafton,” the letter states, “better known as ‘Ed Harrington.’”

“Mr. Trafton is the man from whom Owen Wister modeled the character, The Virginian, in his famous story of that name.”

Melrose went on to laud Trafton/Harrington as a well-known guide for 35 years in the Yellowstone country and a prolific big game hunter. According to the letter he built the first log cabin and blazed the first trails there in 1880. Harrington, Melrose said, was one of the first into the Black Hills for the gold rush there in 1875. He “whacked bulls out of old Cheyenne with the celebrated Buffalo Bill Cody.”

Perhaps the most important detail on his resume, as far as the Virginian connection goes, was that “He fought a duel with the original ‘Trampas,’ better known as Black Tex, who had given Ed until sundown to leave camp.”

Trampas was the name of the villain in The Virginian.

Left out of the Melrose letter were the multiple arrests of Trafton/Harrington, his history as a highwayman, and that time he stole $10,000 from his mother.

Did the author use Trafton/Harrington as the model for one of his characters? Given the man’s shady side, maybe he was the model for Trampas, the bad guy. Trampas and Trafton are a bit similar.

Wister himself never said that the Virginian was modeled after any single person.

The Times noted that, “The man whose adventurous life inspired Owen Wister to write The Virginian, one of the most popular stories of the pioneer West, dropped dead at Second Street and Broadway late yesterday afternoon while drinking an ice cream soda.” The cause of death was listed as apoplexy. He was 64 or 65 and is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

And thus, with Trafton’s end, we begin his story. It will continue with tomorrow’s post.

Starting at the beginning is so conventional in storytelling. In recognition of the irregular nature of this tale’s subject, I’m going to start at the end. On top of that, I’m going to start with something that doesn’t even seem to relate to the subject.

I always thought it odd that the book many scholars consider the first Western novel was called The Virginian. It is set in Wyoming where the lead character, who was born in Virginia, works as a cowboy. He is never referred to by name, only as The Virginian.

The author, at first glance, seems like an odd one to have invented the genre. Owen Wister was born in Philadelphia, attended schools in Britain and Switzerland, and ultimately graduated from Harvard, where he was a Hasty Pudding member. He studied music for a couple of years in a Paris conservatory before turning to the law, and eventually to writing.

Wister became friends with Teddy Roosevelt and, like Roosevelt, spent many summers in the West, mostly in Wyoming.

The Virginian was a monster hit, reprinted fourteen times in 1902, the year it came out. It remains one of the 50 top-selling works of fiction.

So, the author was from Philadelphia, the book was set in Wyoming, where they named a mountain after Wister, and this is a blog about Idaho history. What’s the connection?

Possibly none. However, one-time Idaho State Penitentiary Warden C.E. Arney insisted that Ed Harrington Trafton, one-time inmate of his prison, was the man Wister used as his model for the hero in Wister’s story. That according to an article in the Idaho Statesman of September 17, 1922.

It wasn’t just the Statesman making this claim. On August 16, 1922, the Los Angeles Times ran a story with the stacked headline:

“THE VIRGINIAN”

DIES SUDDENLY

---

Owen Wister Novel Hero

Was Real Pioneer

---

Blazed First Trails Into

Jackson Hole Country

---

Ed Trafton Whacked Bulls

With Buffalo Bill

As proof of the connection, the Times offered a letter of introduction found on Trafton and written by James W. Melrose, who was a special agent in the Department of Justice for 16 years in Denver.

“This will introduce Edwin B. Trafton,” the letter states, “better known as ‘Ed Harrington.’”

“Mr. Trafton is the man from whom Owen Wister modeled the character, The Virginian, in his famous story of that name.”

Melrose went on to laud Trafton/Harrington as a well-known guide for 35 years in the Yellowstone country and a prolific big game hunter. According to the letter he built the first log cabin and blazed the first trails there in 1880. Harrington, Melrose said, was one of the first into the Black Hills for the gold rush there in 1875. He “whacked bulls out of old Cheyenne with the celebrated Buffalo Bill Cody.”

Perhaps the most important detail on his resume, as far as the Virginian connection goes, was that “He fought a duel with the original ‘Trampas,’ better known as Black Tex, who had given Ed until sundown to leave camp.”

Trampas was the name of the villain in The Virginian.

Left out of the Melrose letter were the multiple arrests of Trafton/Harrington, his history as a highwayman, and that time he stole $10,000 from his mother.

Did the author use Trafton/Harrington as the model for one of his characters? Given the man’s shady side, maybe he was the model for Trampas, the bad guy. Trampas and Trafton are a bit similar.

Wister himself never said that the Virginian was modeled after any single person.

The Times noted that, “The man whose adventurous life inspired Owen Wister to write The Virginian, one of the most popular stories of the pioneer West, dropped dead at Second Street and Broadway late yesterday afternoon while drinking an ice cream soda.” The cause of death was listed as apoplexy. He was 64 or 65 and is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

And thus, with Trafton’s end, we begin his story. It will continue with tomorrow’s post.

Published on June 21, 2024 04:00

June 20, 2024

The Cowpuncher--An Idaho First

The first motion picture filmed in Idaho left few tracks. One still from the picture remains along with a copy of the play it was developed from, and a poor-quality publicity shot from a newspaper.

Shot in 1915, The Cowpuncher used sites in and around Idaho Falls, including Wolverine Canyon, Taylor Mountain, and various street scenes. Much of the movie revolved around the War Bonnet Roundup that year.

The filming caused quite a stir in Idaho Falls, with the Idaho Register reporting that “Several thousand people forgot to go to church Sunday morning,” going instead to see the shooting of one of the big scenes of the movie.

There might have been a touch of hype when writers described the film. The Evening Capital News in March 1916 said, “Some of the best known motion picture stars were brought to Idaho to film this feature and that they have turned out a masterpiece is conceded by all who have seen the picture.”

C.M. Griffin, Claudia Louise, and Maria Ascaraga were the “best known” stars in the film, none of who even rate an IMDb mention today.

Motion Picture News in its December 25, 1915 edition stated, “It is not likely that a more massive and pretentious Western Picture will ever be attempted.” Clearly, Heaven’s Gate, also shot in Idaho, was decades beyond the writer’s imagination.

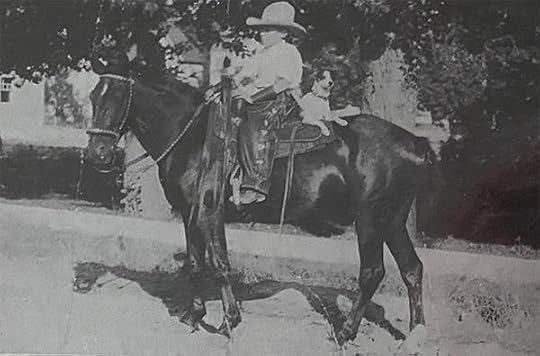

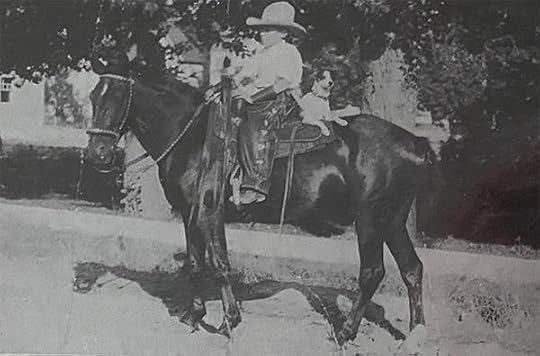

Tom Trusky, who knew how to track down information on lost films, was able to locate an Idaho Falls man, Paul Fisher, in 1990. Fisher had appeared in the film as a boy, and he gave Trusky the still below.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.  This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.

This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.  Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Shot in 1915, The Cowpuncher used sites in and around Idaho Falls, including Wolverine Canyon, Taylor Mountain, and various street scenes. Much of the movie revolved around the War Bonnet Roundup that year.

The filming caused quite a stir in Idaho Falls, with the Idaho Register reporting that “Several thousand people forgot to go to church Sunday morning,” going instead to see the shooting of one of the big scenes of the movie.

There might have been a touch of hype when writers described the film. The Evening Capital News in March 1916 said, “Some of the best known motion picture stars were brought to Idaho to film this feature and that they have turned out a masterpiece is conceded by all who have seen the picture.”

C.M. Griffin, Claudia Louise, and Maria Ascaraga were the “best known” stars in the film, none of who even rate an IMDb mention today.

Motion Picture News in its December 25, 1915 edition stated, “It is not likely that a more massive and pretentious Western Picture will ever be attempted.” Clearly, Heaven’s Gate, also shot in Idaho, was decades beyond the writer’s imagination.

Tom Trusky, who knew how to track down information on lost films, was able to locate an Idaho Falls man, Paul Fisher, in 1990. Fisher had appeared in the film as a boy, and he gave Trusky the still below.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.  This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.

This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.  Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Published on June 20, 2024 04:00

June 19, 2024

A Parade Shooting in Weiser

It’s September 30, 1918. A young man from Kentucky is shot in the abdomen, later dying of his wounds. His draft registration listed John T. Chesnut as a sheepherder working for Hallstrom and Company in Midvale, Idaho.

Just another casualty of World War I?

In a way, perhaps. Chesnut was watching the Wild West parade in Weiser when mounted cavalry members came trotting by, not in formation, but in a skirmish with an invisible enemy. Their ammunition, appropriate for invisible enemies, was blank. Except for that one round.

Harley McCullough fired at Chesnut, striking him in the stomach. The 28-year-old went down. The parade stopped. Chesnut died.

McCullough was described by the Payette Enterprise as “about twenty years of age and well-known in Payette, …a respectable young man (who) is much grieved over the sad accident.”

The shooter was arrested but released on bail. Charges were likely dropped. I found no evidence of his incarceration.

Chesnut’s hometown paper, the London Sentinel, London, Kentucky, made the leap that it was a military demonstration gone wrong during wartime. I think it’s more likely that the “cavalry” were parade participants dressed up as cavalry members from days gone by. Nevertheless, a tragic accident.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Just another casualty of World War I?

In a way, perhaps. Chesnut was watching the Wild West parade in Weiser when mounted cavalry members came trotting by, not in formation, but in a skirmish with an invisible enemy. Their ammunition, appropriate for invisible enemies, was blank. Except for that one round.

Harley McCullough fired at Chesnut, striking him in the stomach. The 28-year-old went down. The parade stopped. Chesnut died.

McCullough was described by the Payette Enterprise as “about twenty years of age and well-known in Payette, …a respectable young man (who) is much grieved over the sad accident.”

The shooter was arrested but released on bail. Charges were likely dropped. I found no evidence of his incarceration.

Chesnut’s hometown paper, the London Sentinel, London, Kentucky, made the leap that it was a military demonstration gone wrong during wartime. I think it’s more likely that the “cavalry” were parade participants dressed up as cavalry members from days gone by. Nevertheless, a tragic accident.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Published on June 19, 2024 04:00

June 18, 2024

Terrifying Three Island Crossing

Three Island Crossing was a terror for Oregon Trail pioneers. The ford at the Snake River near the present-day town of Glenns Ferry was one of the most feared parts of the journey. The river, some 200 yards wide, was deceptively placid looking. The current was relentless. About half those traveling the Oregon Trail risked a crossing there. Half chose to stay on the south side of the river where the trail was worse and longer but the chance of losing everything to the river did not loom.

Narcissa Whitman, one of four missionaries on their way to historic and tragic roles in history, wrote this about the crossing in August of 1836: "We have come fifteen miles and have had the worst route in all the journey for the cart. We might have had a better one but for being misled by some of the company who started out before the leaders.

“It was two o'clock before we came into camp. They were preparing to cross Snake River. The river is divided by two islands into three branches, and is fordable. The packs are placed upon the tops of the highest horses and in this way we crossed without wetting. Two of the tallest horses were selected to carry Mrs. Spalding and myself over. Mr. McLeod gave me his and rode mine. The last branch we rode as much as half a mile in crossing and against the current too, which made it hard for the horses, the water being up to their sides. Husband had considerable difficulty crossing the cart. Both cart and mules were turned upside down in the river and entangled in the harness. The mules would have been drowned but for a desperate struggle to get them ashore. Then after putting two of the strongest horses before the cart, and two men swimming behind to steady it, they succeeded in getting it across.

“I once thought that crossing streams would be the most dreaded part of the journey. I can now cross the most difficult stream without the least fear. There is one manner of crossing which husband has tried but I have not, neither do I wish to. Take an elk skin and stretch it over you, spreading yourself out as much as possible, then let the Indian women carefully put you on the water and with a cord in the mouth they will swim and draw you over. Edward, how do you think you would like to travel in this way?"

John C. Fremont told of another crossing in 1842: “About two o’clock we had arrived at the ford where the road crosses to the right bank of the Snake River. An Indian was hired to conduct us through the ford, which proved impracticable for us, the water sweeping away the howitzer and nearly drowning the mules, which we were able to extricate by cutting them out of the harness. The river is expanded into a little bay, in which there are two islands, across which is the road of the ford; and the emigrants had passed by placing two of their heavy wagons abreast of each other, so as to oppose a considerable mass against the body of water.”

Fremont mentions just two islands, not three. Like other travelers he probably ignored the third island, using just two to make his crossing. The interpretive center at Three Island Crossing State Park tells the story.

One thing not related to the famous crossing at all frustrates rangers there. In recent decades the name Three Island Crossing is often confused with Three Mile Island in the minds of those who remember the nuclear accident that happened a continent away.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

Narcissa Whitman, one of four missionaries on their way to historic and tragic roles in history, wrote this about the crossing in August of 1836: "We have come fifteen miles and have had the worst route in all the journey for the cart. We might have had a better one but for being misled by some of the company who started out before the leaders.

“It was two o'clock before we came into camp. They were preparing to cross Snake River. The river is divided by two islands into three branches, and is fordable. The packs are placed upon the tops of the highest horses and in this way we crossed without wetting. Two of the tallest horses were selected to carry Mrs. Spalding and myself over. Mr. McLeod gave me his and rode mine. The last branch we rode as much as half a mile in crossing and against the current too, which made it hard for the horses, the water being up to their sides. Husband had considerable difficulty crossing the cart. Both cart and mules were turned upside down in the river and entangled in the harness. The mules would have been drowned but for a desperate struggle to get them ashore. Then after putting two of the strongest horses before the cart, and two men swimming behind to steady it, they succeeded in getting it across.

“I once thought that crossing streams would be the most dreaded part of the journey. I can now cross the most difficult stream without the least fear. There is one manner of crossing which husband has tried but I have not, neither do I wish to. Take an elk skin and stretch it over you, spreading yourself out as much as possible, then let the Indian women carefully put you on the water and with a cord in the mouth they will swim and draw you over. Edward, how do you think you would like to travel in this way?"

John C. Fremont told of another crossing in 1842: “About two o’clock we had arrived at the ford where the road crosses to the right bank of the Snake River. An Indian was hired to conduct us through the ford, which proved impracticable for us, the water sweeping away the howitzer and nearly drowning the mules, which we were able to extricate by cutting them out of the harness. The river is expanded into a little bay, in which there are two islands, across which is the road of the ford; and the emigrants had passed by placing two of their heavy wagons abreast of each other, so as to oppose a considerable mass against the body of water.”

Fremont mentions just two islands, not three. Like other travelers he probably ignored the third island, using just two to make his crossing. The interpretive center at Three Island Crossing State Park tells the story.

One thing not related to the famous crossing at all frustrates rangers there. In recent decades the name Three Island Crossing is often confused with Three Mile Island in the minds of those who remember the nuclear accident that happened a continent away.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

Published on June 18, 2024 04:00

June 17, 2024

Carjacking, Part II

Yesterday we started the story of the 1929 kidnapping of Idaho Lieutenant Governor William Barker Kinne, and two other men taken in a later carjacking. When we left off, a Latah County deputy had located two of the outlaws along the railroad tracks near Juliaetta.

At the point of his shotgun, Deputy Miles Pierce ordered the tramps out of the brush. One was a man with striking red hair. His name was Frank “Red” Lane, though he also used the alias Eward Fliss. The 24-year old was in possession of three handguns. The other man found sleeping in the brush was 20-year-old Engolf Snortland, who was described as tall and blond.

Their capture was followed a short time later by the capture of Albert Reynolds, 24, who had been spotted about 100 yards away by two local boys.

Meanwhile, John Kite, a local dairyman, had reported selling a couple of quarts of milk, a loaf of bread, and some jam to a scruffy looking pair of men who claimed they had just arrived on the morning freight and were in the area to pick cherries.

Within an hour Kendrick Town Constable Ernest Davis along with two Latah County deputies located the “cherry pickers” and arrested them without incident. The last fugitives were identified as 19-year-old Robert Livingston and “Seattle George” Norman, a well-known outlaw in the Northwest.

Lt. Gov Kinne would soon identify the four younger men as his kidnappers. Norman, who hadn’t taken part in that fiasco, was the ringleader of the group. He had sent the four to hijack a car so they could all rob a bank they had their eyes on in Pierce. Kidnapping was just a by-product of their need for a getaway car.

Their bumbling, violent actions in the kidnappings had marked the men as inept criminals. To underline that judgment, authorities found they had left the $200 they had stolen from Tribbey behind in his car when they abandoned it.

Local citizens, many of whom had spent hours searching for the abductors, were outraged at their vicious behavior.

When deputies escorted the outlaws to the Nez Perce County Jail in Lewiston, some 1,500 men were gathered in front of the building, many of them armed. While Sherriff Harry Dent created a diversion to distract the crowd, Lewiston Police Chief Eugene Gasser got the prisoners in through the back door.

Having avoided an angry crowd, the outlaws did not avoid the wrath of the law. The four carjackers pleaded guilty to kidnapping and were on their way to the Idaho State Prison in Boise, just eight days after the incident took place. Each got sentences of up to 25 years.

“Seattle George” Norman, the brains behind the plot to rob the bank, pleaded guilty to being an accessory after the fact to the kidnapping and was sentenced to two years in prison.

Although the planned bank robbery went ridiculously wrong it turned out that three of the four men involved in the kidnapping were experienced bank robbers. They were identified through fingerprints as the men who had kidnapped one of the owners of a bank in Gilmore City, Iowa. They had held his family prisoners overnight just weeks before. They forced the banker to open a safe in the morning and got away with $5,000.

Iowa wanted the men back. Governor Baldridge was quoted as saying, “Idaho would be extremely reluctant to let Lieutenant Governor Kinne’s abductors out of prison to go to Iowa or anywhere else for trial on other charges.”

Most of the culprits used aliases, but 19-year-old Engolf Snortland was the champion at names. He also went by Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds. Careful readers will note that the latter three aliases were the names of his partners in crime. That made it confusing for reporters who often used variations of the men’s names and aliases when listing them.

Snortland/Snoysland/Livingston/Lane/Reynolds was the most difficult to pin a name on, but it was Frank Lane who became someone else in criminal history.

Lane, according to Idaho State Prison records used the alias Edward Fliss. He was pardoned in April 1934. It took him about two seconds to land in seriously hot water again. This time Fliss was the name that went down in the records.

Lane/Fliss had met a prisoner by the name of William Dainard in the Idaho State Prison. Dainard was the mastermind behind the kidnapping of George Weyerhaeuser on May 24, 1935, one of the more infamous crimes in the Pacific Northwest. Fliss was convicted in relation to that kidnapping for helping Dainard exchange some of the ransom money. Fliss received another 10 years in prison for that.

This story started with Lieutenant Governer Kinne. Sadly, it ends with his death, not long after the abduction.

Kinne had a case of appendicitis, so diagnosed by a local doctor who thought it not especially serious. He delayed an operation, perhaps too long. Kinne’s appendix had ruptured, causing peritonitis. He died on October 1, 1929 at age 50, having been in office less than a year.

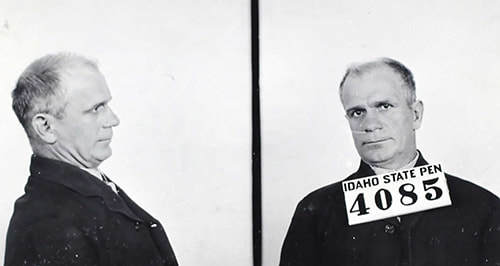

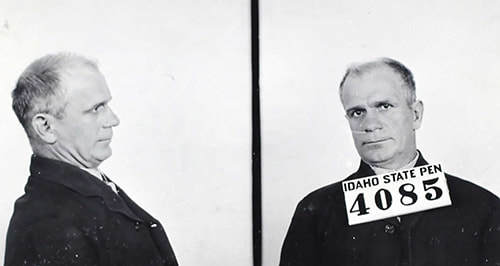

"Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.

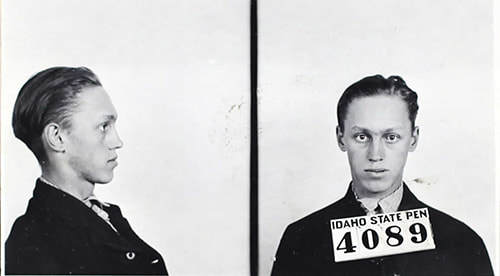

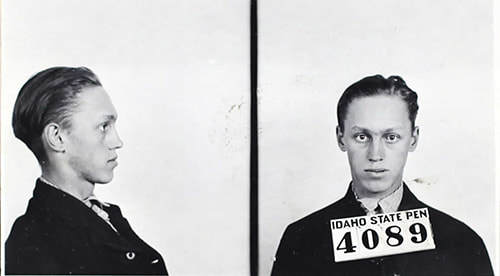

"Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.  Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.

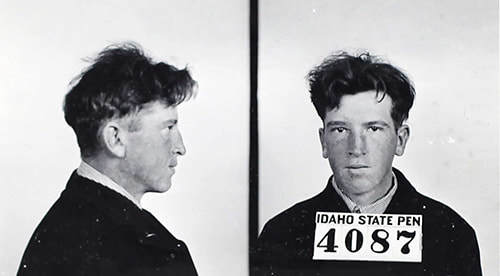

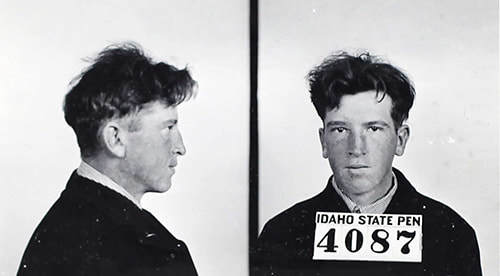

Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.  Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.

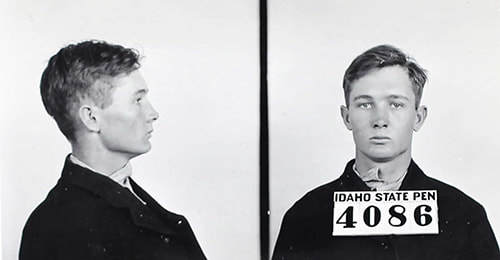

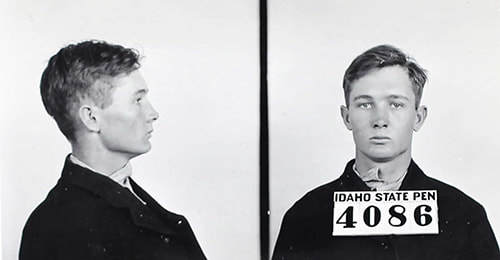

Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.  Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.

Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.  Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

At the point of his shotgun, Deputy Miles Pierce ordered the tramps out of the brush. One was a man with striking red hair. His name was Frank “Red” Lane, though he also used the alias Eward Fliss. The 24-year old was in possession of three handguns. The other man found sleeping in the brush was 20-year-old Engolf Snortland, who was described as tall and blond.

Their capture was followed a short time later by the capture of Albert Reynolds, 24, who had been spotted about 100 yards away by two local boys.

Meanwhile, John Kite, a local dairyman, had reported selling a couple of quarts of milk, a loaf of bread, and some jam to a scruffy looking pair of men who claimed they had just arrived on the morning freight and were in the area to pick cherries.

Within an hour Kendrick Town Constable Ernest Davis along with two Latah County deputies located the “cherry pickers” and arrested them without incident. The last fugitives were identified as 19-year-old Robert Livingston and “Seattle George” Norman, a well-known outlaw in the Northwest.

Lt. Gov Kinne would soon identify the four younger men as his kidnappers. Norman, who hadn’t taken part in that fiasco, was the ringleader of the group. He had sent the four to hijack a car so they could all rob a bank they had their eyes on in Pierce. Kidnapping was just a by-product of their need for a getaway car.

Their bumbling, violent actions in the kidnappings had marked the men as inept criminals. To underline that judgment, authorities found they had left the $200 they had stolen from Tribbey behind in his car when they abandoned it.

Local citizens, many of whom had spent hours searching for the abductors, were outraged at their vicious behavior.

When deputies escorted the outlaws to the Nez Perce County Jail in Lewiston, some 1,500 men were gathered in front of the building, many of them armed. While Sherriff Harry Dent created a diversion to distract the crowd, Lewiston Police Chief Eugene Gasser got the prisoners in through the back door.

Having avoided an angry crowd, the outlaws did not avoid the wrath of the law. The four carjackers pleaded guilty to kidnapping and were on their way to the Idaho State Prison in Boise, just eight days after the incident took place. Each got sentences of up to 25 years.

“Seattle George” Norman, the brains behind the plot to rob the bank, pleaded guilty to being an accessory after the fact to the kidnapping and was sentenced to two years in prison.

Although the planned bank robbery went ridiculously wrong it turned out that three of the four men involved in the kidnapping were experienced bank robbers. They were identified through fingerprints as the men who had kidnapped one of the owners of a bank in Gilmore City, Iowa. They had held his family prisoners overnight just weeks before. They forced the banker to open a safe in the morning and got away with $5,000.

Iowa wanted the men back. Governor Baldridge was quoted as saying, “Idaho would be extremely reluctant to let Lieutenant Governor Kinne’s abductors out of prison to go to Iowa or anywhere else for trial on other charges.”

Most of the culprits used aliases, but 19-year-old Engolf Snortland was the champion at names. He also went by Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds. Careful readers will note that the latter three aliases were the names of his partners in crime. That made it confusing for reporters who often used variations of the men’s names and aliases when listing them.

Snortland/Snoysland/Livingston/Lane/Reynolds was the most difficult to pin a name on, but it was Frank Lane who became someone else in criminal history.

Lane, according to Idaho State Prison records used the alias Edward Fliss. He was pardoned in April 1934. It took him about two seconds to land in seriously hot water again. This time Fliss was the name that went down in the records.

Lane/Fliss had met a prisoner by the name of William Dainard in the Idaho State Prison. Dainard was the mastermind behind the kidnapping of George Weyerhaeuser on May 24, 1935, one of the more infamous crimes in the Pacific Northwest. Fliss was convicted in relation to that kidnapping for helping Dainard exchange some of the ransom money. Fliss received another 10 years in prison for that.

This story started with Lieutenant Governer Kinne. Sadly, it ends with his death, not long after the abduction.

Kinne had a case of appendicitis, so diagnosed by a local doctor who thought it not especially serious. He delayed an operation, perhaps too long. Kinne’s appendix had ruptured, causing peritonitis. He died on October 1, 1929 at age 50, having been in office less than a year.

"Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.

"Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.  Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.

Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.  Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.

Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.  Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.

Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.  Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

Published on June 17, 2024 04:00

June 16, 2024

Carjacking, 1929 Style

“I had driven about a half mile past Arrow when four men, all brandishing pistols, stepped out from the side of the road and halted me.”

That’s how Idaho Lieutenant Governor W.B. Kinne started the story about his abduction when talking to an Associated Press reporter in June 1929. Kinne, who had been elected the year before, was a well-to-do businessman from Orofino, so kidnapping for ransom came to the minds of officials when they discovered he was missing. Governor Baldridge considered calling out the National Guard to search for Kinne, but the incident was over before he could make that move.

It turned out the abductors weren’t carrying out a ransom scheme. They had no idea who Kinne was when they commandeered his car. They just needed a car. They probably took Kinne with them only to keep him from reporting the car theft.

As the lieutenant governor told the story the men forced him into the back of the car and onto the floor, one of them getting behind the wheel and driving on at a high rate of speed. That speed and a blown tire caused the car to hurtle off the road near Orofino and flip over. None of the men were badly hurt, but their newly acquired car was no longer a prize.

“The men forced me to walk out into a field, and as they did so another car pulled up,” Kene told reporters. “Two men, who I learned were W.L. Tribbey of the Idaho Building and Loan Association and Paul Kille, a lumber worker, got out of the car and as they walked toward us, the four men turned their guns on them. Kille was shot in the leg and clubbed over the head with guns until he went down. Tribbey was beaten badly.”

Now with three hostages the bandits piled into Tribbey’s car and raced off into the mountains. They found an isolated spot and tied the hostages to a tree. One of the bandits stood guard, while the remaining three drove off, only to return about four hours later without explanation.

The men took $14 from the wounded Kille, and $200 from Tribbey. They threatened the bound hostages with death and told them not to move for at least four hours. Then, all four of the highwaymen drove off in the stolen car.

Tribbey ignored their threat and freed himself within about 15 minutes. He untied the others and they all set off on foot for the nearby town of Greer.

The harrowing story told by the victims set off a four-state manhunt for the car thieves.

The kidnappers were described as being between 18 and 25 years of age, armed, and “desperate.” Law enforcement was on the lookout for Tribbey’s blue sedan, plate number 249-060.

Citizens were outraged by the kidnappings. Every able-bodied man who could take off work in Nez Perce, Lewis, Latah, and Clearwater counties joined the search. Indian trackers and Boy Scouts joined farmers and loggers. Bloodhounds were flown in from Yakima.

For two days thousands of men searched for the four assailants, checking cars at intersections, and looking into outbuildings. Nothing turned up. Then early in the morning, Friday, June 14, Latah County Deputy Miles Pierce spotted two men asleep in undergrowth along the railroad tracks near Juliaetta. Those men woke to find a shotgun in their faces.

We’ll continue the story in tomorrow’s Speaking of Idaho post.

That’s how Idaho Lieutenant Governor W.B. Kinne started the story about his abduction when talking to an Associated Press reporter in June 1929. Kinne, who had been elected the year before, was a well-to-do businessman from Orofino, so kidnapping for ransom came to the minds of officials when they discovered he was missing. Governor Baldridge considered calling out the National Guard to search for Kinne, but the incident was over before he could make that move.

It turned out the abductors weren’t carrying out a ransom scheme. They had no idea who Kinne was when they commandeered his car. They just needed a car. They probably took Kinne with them only to keep him from reporting the car theft.

As the lieutenant governor told the story the men forced him into the back of the car and onto the floor, one of them getting behind the wheel and driving on at a high rate of speed. That speed and a blown tire caused the car to hurtle off the road near Orofino and flip over. None of the men were badly hurt, but their newly acquired car was no longer a prize.

“The men forced me to walk out into a field, and as they did so another car pulled up,” Kene told reporters. “Two men, who I learned were W.L. Tribbey of the Idaho Building and Loan Association and Paul Kille, a lumber worker, got out of the car and as they walked toward us, the four men turned their guns on them. Kille was shot in the leg and clubbed over the head with guns until he went down. Tribbey was beaten badly.”

Now with three hostages the bandits piled into Tribbey’s car and raced off into the mountains. They found an isolated spot and tied the hostages to a tree. One of the bandits stood guard, while the remaining three drove off, only to return about four hours later without explanation.

The men took $14 from the wounded Kille, and $200 from Tribbey. They threatened the bound hostages with death and told them not to move for at least four hours. Then, all four of the highwaymen drove off in the stolen car.

Tribbey ignored their threat and freed himself within about 15 minutes. He untied the others and they all set off on foot for the nearby town of Greer.

The harrowing story told by the victims set off a four-state manhunt for the car thieves.

The kidnappers were described as being between 18 and 25 years of age, armed, and “desperate.” Law enforcement was on the lookout for Tribbey’s blue sedan, plate number 249-060.

Citizens were outraged by the kidnappings. Every able-bodied man who could take off work in Nez Perce, Lewis, Latah, and Clearwater counties joined the search. Indian trackers and Boy Scouts joined farmers and loggers. Bloodhounds were flown in from Yakima.

For two days thousands of men searched for the four assailants, checking cars at intersections, and looking into outbuildings. Nothing turned up. Then early in the morning, Friday, June 14, Latah County Deputy Miles Pierce spotted two men asleep in undergrowth along the railroad tracks near Juliaetta. Those men woke to find a shotgun in their faces.

We’ll continue the story in tomorrow’s Speaking of Idaho post.

Published on June 16, 2024 04:00

June 15, 2024

The Kelton Road

Idaho history doesn’t always neatly fit within the state’s borders. Such is the case with Kelton, Utah.

Kelton, named after a local stockman, became a section station on the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. It was located north of the Great Salt Lake and southwest of present-day Snowville, Utah.

In 1863 John Hailey established a stage route between Salt Lake City and Boise. Kelton was one of the stations along the way. Six years later, when Kelton became the best point to connect to the railroad from Boise, the route became known as the Kelton Road.

You can get to the ghost town of Kelton today in less than four hours. In the 1860s it took a little longer. A stage could make between the two towns in 42 hours. If you were hauling freight, it could take 18 days. Here’s a list of the stage stops along the Kelton Road, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s Reference Series.

Black's Creek (15 miles from Boise)

Baylock (13 miles)

Canyon Creek (12 miles)

Rattlesnake (8 miles)

Cold Springs (12 miles)

King Hill (10 miles)

Clover Creek (11 miles)

Malad (11 miles)

Sand Springs (11 miles)

Snake River at Clark's Ferry (10 miles)

Desert (12 miles)

Rock Creek (13 miles)

Mountain Meadows (14 miles)

Oakley Meadows (12 miles)

Goose Creek Summit (11 miles)

City of Rocks (11 miles)

Raft River (12 miles)

Clear Creek (12 miles)

Crystal Springs (10 miles)

Kelton (12 miles)

Kelton, Utah’s unique position as Idaho’s railway station ended in 1883 when the Oregon Shortline came through Southern Idaho. The end was sudden. By 1884 a traveler on the old route noticed that “grass now grows over the defunct overland Kelton stage road where the weary traveler once traveled in clouds of dust. . ."

Kelton survived until 1942 when the Southern Pacific pulled out the rails that had made the town boom.

You can see ruts through the lava and an old bridge abutment on the Kelton Road at Malad Gorge State Park. Go to the park unit north of the freeway.

You can also soak up some Kelton Road history at Stricker Ranch, operated by the Idaho State Historical Society. Rock Creek Station was there.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little-known treasure where you can see some amazing water-carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little-known treasure where you can see some amazing water-carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

Kelton, named after a local stockman, became a section station on the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. It was located north of the Great Salt Lake and southwest of present-day Snowville, Utah.

In 1863 John Hailey established a stage route between Salt Lake City and Boise. Kelton was one of the stations along the way. Six years later, when Kelton became the best point to connect to the railroad from Boise, the route became known as the Kelton Road.

You can get to the ghost town of Kelton today in less than four hours. In the 1860s it took a little longer. A stage could make between the two towns in 42 hours. If you were hauling freight, it could take 18 days. Here’s a list of the stage stops along the Kelton Road, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s Reference Series.

Black's Creek (15 miles from Boise)

Baylock (13 miles)

Canyon Creek (12 miles)

Rattlesnake (8 miles)

Cold Springs (12 miles)

King Hill (10 miles)

Clover Creek (11 miles)

Malad (11 miles)

Sand Springs (11 miles)

Snake River at Clark's Ferry (10 miles)

Desert (12 miles)

Rock Creek (13 miles)

Mountain Meadows (14 miles)

Oakley Meadows (12 miles)

Goose Creek Summit (11 miles)

City of Rocks (11 miles)

Raft River (12 miles)

Clear Creek (12 miles)

Crystal Springs (10 miles)

Kelton (12 miles)

Kelton, Utah’s unique position as Idaho’s railway station ended in 1883 when the Oregon Shortline came through Southern Idaho. The end was sudden. By 1884 a traveler on the old route noticed that “grass now grows over the defunct overland Kelton stage road where the weary traveler once traveled in clouds of dust. . ."

Kelton survived until 1942 when the Southern Pacific pulled out the rails that had made the town boom.

You can see ruts through the lava and an old bridge abutment on the Kelton Road at Malad Gorge State Park. Go to the park unit north of the freeway.

You can also soak up some Kelton Road history at Stricker Ranch, operated by the Idaho State Historical Society. Rock Creek Station was there.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little-known treasure where you can see some amazing water-carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little-known treasure where you can see some amazing water-carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

Published on June 15, 2024 04:00

June 14, 2024

He Refused to Leave Office

John H.T. Greene purchased the Stage House in Boise in October 1865. He was the fourth owner of the business that year. Perhaps there was a cashflow problem. When he took over the establishment, from which stages departed, patrons could get room and board for $18 a week. A few months later that rose to $21 a week.

The Stage House was under Greene’s management for ten years. His name appeared in the papers often in connection that venture.

But it was Greene’s term as Ada County Treasurer that caused readers to sit up and take notice. He was elected in 1865. In 1867, residents elected another man whose name doesn’t merit a mention in this story.

J.H.T. Greene refused to leave office upon his defeat. He declined to turn over the books and other paraphernalia associated with his position, even when ordered to do so by a judge. His residence became the Ada County Jail. He was jailed for refusing to put up a $2,000 bond set to assure that he would pay whatever fees and emoluments might come into his hands pending the determination of the suit to oust him. Though “jailed,” he still had the run of the city.

Greene began a hobby of filing writs of Habeas Corpus with judges, one after another, until he found one—the fourth one—who would set him free.

The Idaho Statesman commented about Greene’s refusal to leave office, saying, “the old man thinks he was elected for life.”

What was Greene thinking? He argued the election of 1867 was not legal because it was not a “general election” as provided by the legislature, and that no provision for a special election had been made. The court bought that argument, and he remained the treasurer.

But was the reason Greene fought so hard for his job because he believed so much in the rule of law? Maybe. It seems that Greene might also have been reluctant to turn over the books because he considered it risky to do so. Shortly after his success in retaining his office, Greene was indicted for embezzling $32,000 in county funds. His defense was that just because the county was broke didn’t mean he’d embezzled money.

The Idaho Statesman recounted one incident where “someone” had changed a $15 warrant to a $250 warrant, stating, “We find unmistakable signs of tampering with the figures and body of the warrant by some person who has a very limited education in the art of forgery.”

Greene was charged with forgery and embezzlement. Taxpayers in the county began to get grumpy. One letter writer said, “I am at a loss whether to pay my taxes or not. If there is no show of it benefitting the county, I am disposed to resist the collector.”

A district court judge found that “It (was) difficult to get facts, figures and dates positive enough to make them stick.” He dismissed the charges. The Idaho Supreme Court had a go at the embezzlement case and came back with a Nolle Prosequi ruling, meaning they would no longer prosecute it. As the Statesman explained, “the books (have been) kept in so loose a manner that the required facts cannot be elicited from them.”

Books so poorly kept that no one could understand them would seem to be enough to cast a cloud over Treasurer Greene’s service. Yet, his death notice, printed November 13, 1875, called him “one of the old and respected citizens of this place.” The notice made no mention of his service as Ada County Treasurer, and respected as he might have been, the mortuary spelled his name wrong, omitting the final E.

The Stage House was under Greene’s management for ten years. His name appeared in the papers often in connection that venture.

But it was Greene’s term as Ada County Treasurer that caused readers to sit up and take notice. He was elected in 1865. In 1867, residents elected another man whose name doesn’t merit a mention in this story.

J.H.T. Greene refused to leave office upon his defeat. He declined to turn over the books and other paraphernalia associated with his position, even when ordered to do so by a judge. His residence became the Ada County Jail. He was jailed for refusing to put up a $2,000 bond set to assure that he would pay whatever fees and emoluments might come into his hands pending the determination of the suit to oust him. Though “jailed,” he still had the run of the city.

Greene began a hobby of filing writs of Habeas Corpus with judges, one after another, until he found one—the fourth one—who would set him free.

The Idaho Statesman commented about Greene’s refusal to leave office, saying, “the old man thinks he was elected for life.”

What was Greene thinking? He argued the election of 1867 was not legal because it was not a “general election” as provided by the legislature, and that no provision for a special election had been made. The court bought that argument, and he remained the treasurer.

But was the reason Greene fought so hard for his job because he believed so much in the rule of law? Maybe. It seems that Greene might also have been reluctant to turn over the books because he considered it risky to do so. Shortly after his success in retaining his office, Greene was indicted for embezzling $32,000 in county funds. His defense was that just because the county was broke didn’t mean he’d embezzled money.

The Idaho Statesman recounted one incident where “someone” had changed a $15 warrant to a $250 warrant, stating, “We find unmistakable signs of tampering with the figures and body of the warrant by some person who has a very limited education in the art of forgery.”

Greene was charged with forgery and embezzlement. Taxpayers in the county began to get grumpy. One letter writer said, “I am at a loss whether to pay my taxes or not. If there is no show of it benefitting the county, I am disposed to resist the collector.”

A district court judge found that “It (was) difficult to get facts, figures and dates positive enough to make them stick.” He dismissed the charges. The Idaho Supreme Court had a go at the embezzlement case and came back with a Nolle Prosequi ruling, meaning they would no longer prosecute it. As the Statesman explained, “the books (have been) kept in so loose a manner that the required facts cannot be elicited from them.”

Books so poorly kept that no one could understand them would seem to be enough to cast a cloud over Treasurer Greene’s service. Yet, his death notice, printed November 13, 1875, called him “one of the old and respected citizens of this place.” The notice made no mention of his service as Ada County Treasurer, and respected as he might have been, the mortuary spelled his name wrong, omitting the final E.

Published on June 14, 2024 04:00

June 13, 2024

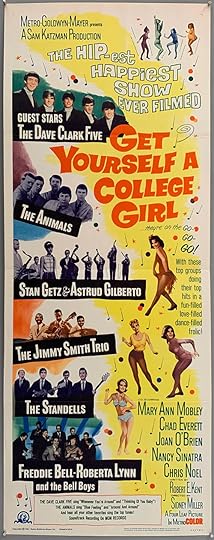

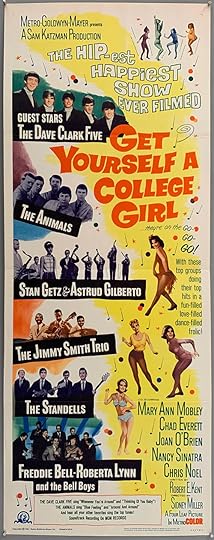

Get Yourself a College Girl

Would it surprise you to learn that “the hip-est, happiest show ever filmed” was shot in Idaho? Yes? Then prepare to be flabbergasted. Get Yourself a College Girl was the movie thus billed. It was so hip that it starred former Miss America Mary Ann Mobley, Chad Everett, and Nancy Sinatra, the latter a couple of years before her hit song about boots.

Not to worry, though. Nancy didn’t sing in the movie, but sooo many others did, including the Standells, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, The Dave Clark Five, and The Animals. How hip is that? The movie was largely an excuse to have those groups and others perform in front of a camera.

The film was one of many shot in Sun Valley, this one in 1963. It was didn’t get rave revidews. The LA Times called it “inoffensively silly.” Still, it’s with enduring a 30 second commercial to watch the trailer on YouTube.

Not to worry, though. Nancy didn’t sing in the movie, but sooo many others did, including the Standells, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, The Dave Clark Five, and The Animals. How hip is that? The movie was largely an excuse to have those groups and others perform in front of a camera.

The film was one of many shot in Sun Valley, this one in 1963. It was didn’t get rave revidews. The LA Times called it “inoffensively silly.” Still, it’s with enduring a 30 second commercial to watch the trailer on YouTube.

Published on June 13, 2024 04:00