Rick Just's Blog, page 24

May 11, 2024

Dead Horse Cave

Idaho has its fair share of caves. I’ve written about 40 Horse Cave, Aviator Cave, Wilson Butte Cave, and others. Today’s story spotlights an annual gathering in a place called Dead Horse Cave, sometimes Jericho Dead Horse Cave.

A 1966 headline in the Twin Falls Times news called Dead Horse Cave, “Probably (the) World’s Biggest Hall.” If that seems an odd way to describe a cave, blame the Odd Fellows. The Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF) held meetings there annually beginning at least as far back as the 1930s. They “improved” the cave with entrance stairs and concrete benches along the sides of the main room, which is 40 feet below the surface. It’s big enough to hold 300 Odd Fellows, according to various clips about their meetings. They don’t seem to be meeting there anymore, but did so into the late 60s.

The cave is named for its propensity to swallow up wild horses. The opening is more or less in the roof of the lava tube, meaning it was an unexpected hole in the ground when horses galloped across the desert. The bones of equines piled up on the floor of the cave leading to an obvious name.

Dead Horse cave is about 11 miles northwest of Gooding. Ask around or check with the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce. It is well known locally. A visit in the heat of summer is recommended, since the air in the cave hovers around 56 degrees year-round. The steps down into Dead Horse Cave.

The steps down into Dead Horse Cave.

A 1966 headline in the Twin Falls Times news called Dead Horse Cave, “Probably (the) World’s Biggest Hall.” If that seems an odd way to describe a cave, blame the Odd Fellows. The Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF) held meetings there annually beginning at least as far back as the 1930s. They “improved” the cave with entrance stairs and concrete benches along the sides of the main room, which is 40 feet below the surface. It’s big enough to hold 300 Odd Fellows, according to various clips about their meetings. They don’t seem to be meeting there anymore, but did so into the late 60s.

The cave is named for its propensity to swallow up wild horses. The opening is more or less in the roof of the lava tube, meaning it was an unexpected hole in the ground when horses galloped across the desert. The bones of equines piled up on the floor of the cave leading to an obvious name.

Dead Horse cave is about 11 miles northwest of Gooding. Ask around or check with the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce. It is well known locally. A visit in the heat of summer is recommended, since the air in the cave hovers around 56 degrees year-round.

The steps down into Dead Horse Cave.

The steps down into Dead Horse Cave.

Published on May 11, 2024 04:00

May 10, 2024

Famous Potholes

Did I tell you how much I love potatoes? Love ‘em. Not so much on my license plates, though. So, in the late 1980s my brother, Kent Just, and I set out to give Idahoans a choice. I located the company that made the reflective material used on the license plates at that time and learned that you could buy it in strips. I ordered a roll of the stuff and had slogans printed on it in the same size, font, and color as the slogan on the license plates. Buyers could peel off the paper on the back and stick the new slogan over “Famous Potatoes.” We sold them for a couple of bucks through Stinker Stations. You could pick from “Famous Potholes,” “The Whitewater State,” “The Gem State,” “Where Utah Skis,” and “Tick Fever State.”

Kent acted as the front man on this project, because I was working for the State of Idaho at the time and was a little unsure about how my employer would take this little prank. We got publicity for the project in papers from Washington State to Washington DC. Some of the articles made it sound like we had a factory cranking these out by the thousands. I had a roll of stickers and a pair of scissors.

Encouraging people to put an unauthorized sticker on a license plate ruffled the feathers of the folks over at Idaho State Police HQ. They made noises about it sufficient enough to convince us stop selling them. We were certain we were on solid legal ground because the US Supreme Court had already ruled that it was legal to cover up a license plate slogan in the name of free speech (New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die”). Still, it didn’t seem worthwhile to hire a lawyer for a $150 joke. We’d had our fun, and we’d already made our money back.

Kent passed away in 2017. I know he wouldn’t mind my adding this little footnote to a footnote in Idaho history. I can hear his way-too-loud laugh right now.

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Kent acted as the front man on this project, because I was working for the State of Idaho at the time and was a little unsure about how my employer would take this little prank. We got publicity for the project in papers from Washington State to Washington DC. Some of the articles made it sound like we had a factory cranking these out by the thousands. I had a roll of stickers and a pair of scissors.

Encouraging people to put an unauthorized sticker on a license plate ruffled the feathers of the folks over at Idaho State Police HQ. They made noises about it sufficient enough to convince us stop selling them. We were certain we were on solid legal ground because the US Supreme Court had already ruled that it was legal to cover up a license plate slogan in the name of free speech (New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die”). Still, it didn’t seem worthwhile to hire a lawyer for a $150 joke. We’d had our fun, and we’d already made our money back.

Kent passed away in 2017. I know he wouldn’t mind my adding this little footnote to a footnote in Idaho history. I can hear his way-too-loud laugh right now.

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Published on May 10, 2024 04:00

May 9, 2024

Addicted to Spuds

I’ve written often about songs related to Idaho. Not surprisingly, I missed one (at least). A reader pointed me toward “Addicted to Spuds” by Weird Al Yankovic. It’s a parody of the 1985 song “Addicted to Love,” written and performed by Robert Palmer.

The song uses the lyric, “Might as well face it I’m addicted to spuds” no less than sixteen times. Here’s a link the Yankovic lyrics. And here’s a link to his performance.

Enjoy.

"Weird Al" Yankovic. (2024, April 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%22Weir...

"Weird Al" Yankovic. (2024, April 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%22Weir...

The song uses the lyric, “Might as well face it I’m addicted to spuds” no less than sixteen times. Here’s a link the Yankovic lyrics. And here’s a link to his performance.

Enjoy.

"Weird Al" Yankovic. (2024, April 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%22Weir...

"Weird Al" Yankovic. (2024, April 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%22Weir...

Published on May 09, 2024 04:00

May 8, 2024

George Shoup and Sandcreek

George L. Shoup, famous in Idaho history as the state's first governor, was a young officer in the United States Army when he participated in the Sand Creek Massacre. At the time, he believed that the Native American tribes in the area posed a threat to the safety and security of white settlers, and he believed that it was his duty to protect those settlers by any means necessary.

On that fateful day in November of 1864, Shoup rode into the Cheyenne and Arapaho village with a detachment of troops, and he witnessed the horrific violence that unfolded. Women and children were shot and bayoneted, teepees were set on fire, and the entire village was destroyed.

In the aftermath of the massacre, Shoup was troubled by what he had witnessed. He couldn't shake the feeling that something had gone terribly wrong, and that innocent people had been needlessly killed. He struggled to reconcile his actions with his conscience, and he began to question the assumptions and beliefs that had led him to participate in the massacre in the first place.

Over time, Shoup began to distance himself from the army and the government's treatment of Native Americans. He became an advocate for their rights, and he spoke out against the atrocities that he had witnessed firsthand. He worked to build bridges between the white settlers and the tribes, and he urged his fellow citizens to see the humanity and dignity of the Native American people.

It wasn't an easy journey for Shoup. He faced criticism and backlash from those who still believed in the doctrine of manifest destiny and the superiority of the white race. But he persevered, driven by a sense of moral obligation and a desire to make amends for the mistakes of his past.

In the end, George L. Shoup became a champion for Native American rights, and a symbol of the power of personal growth and transformation. He recognized the harm that had been done to the indigenous peoples of America, and he worked tirelessly to make things right. Though he could never undo the harm he had caused, he dedicated his life to ensuring that such atrocities would never be repeated again. The statue of George Shoup in Statuary Hall in the US Capitol.

The statue of George Shoup in Statuary Hall in the US Capitol.

On that fateful day in November of 1864, Shoup rode into the Cheyenne and Arapaho village with a detachment of troops, and he witnessed the horrific violence that unfolded. Women and children were shot and bayoneted, teepees were set on fire, and the entire village was destroyed.

In the aftermath of the massacre, Shoup was troubled by what he had witnessed. He couldn't shake the feeling that something had gone terribly wrong, and that innocent people had been needlessly killed. He struggled to reconcile his actions with his conscience, and he began to question the assumptions and beliefs that had led him to participate in the massacre in the first place.

Over time, Shoup began to distance himself from the army and the government's treatment of Native Americans. He became an advocate for their rights, and he spoke out against the atrocities that he had witnessed firsthand. He worked to build bridges between the white settlers and the tribes, and he urged his fellow citizens to see the humanity and dignity of the Native American people.

It wasn't an easy journey for Shoup. He faced criticism and backlash from those who still believed in the doctrine of manifest destiny and the superiority of the white race. But he persevered, driven by a sense of moral obligation and a desire to make amends for the mistakes of his past.

In the end, George L. Shoup became a champion for Native American rights, and a symbol of the power of personal growth and transformation. He recognized the harm that had been done to the indigenous peoples of America, and he worked tirelessly to make things right. Though he could never undo the harm he had caused, he dedicated his life to ensuring that such atrocities would never be repeated again.

The statue of George Shoup in Statuary Hall in the US Capitol.

The statue of George Shoup in Statuary Hall in the US Capitol.

Published on May 08, 2024 04:00

May 6, 2024

The Silver Thieves

In January 1975 thieves broke into the Utah State Historical Society and stole $22,380 worth of silver which had once been part of the officers’ mess on the USS Utah. The thieves entered the building via scaffolding that was in use for repairs. The collection included cups, plates, and trays made of sterling silver from the Utah and a sword from an unrelated collection.

And, it is about now that you’re wondering what this has to do with Idaho. Nothing. Maybe.

Just over a year later, the headline in The Idaho Statesman read, “Burglars Loot Museum, Steal Silver.” This time the burglary was in Idaho and the loot was from the USS Idaho. The value of the purloined silver service in Idaho was set as “several hundred dollars,” but it wasn’t the monetary value the Idaho State Historical Society was worried about. The silver tea service from the Idaho, along with a few silver ingots and medals given to Governor Cecil D. Andrus at the Western Governor’s Conference the year before, were prized for their historical value.

The sterling silver tea service had been used during inaugural balls ever since the Idaho had been decommissioned in 1946. It was irreplaceable.

In the Idaho burglary there was no handy scaffolding for the thieves to climb. They brought a ladder with them. One of the burglars—perhaps it was a single burglar—climbed up to reach a window on an enclosed porch, broke the window, then crawled in. This may have been a clue. The window was one foot by one-and-a-half feet, meaning the culprit must have been small.

Once inside the thief or thieves smashed the display case glass to get to the tea set. Police speculated that they used the punch bowl from the set as a basket, piling the rest of the loot inside. They went out a door and fled northeast across Julia Davis Park, marking their route when they dropped a serving tray from the set, not bothering to retrieve it.

And that, sadly, is the end of the story. None of the silver from either robbery was ever recovered. It was likely melted down and cashed in.

The tea service from the USS Idaho had a history with the WWII ship, but its connection to Idaho went even further back. The service was donated by the people of Idaho for use on the predecessor ship, the USS Idaho in 1912, so it had served on two ships bearing that name.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

And, it is about now that you’re wondering what this has to do with Idaho. Nothing. Maybe.

Just over a year later, the headline in The Idaho Statesman read, “Burglars Loot Museum, Steal Silver.” This time the burglary was in Idaho and the loot was from the USS Idaho. The value of the purloined silver service in Idaho was set as “several hundred dollars,” but it wasn’t the monetary value the Idaho State Historical Society was worried about. The silver tea service from the Idaho, along with a few silver ingots and medals given to Governor Cecil D. Andrus at the Western Governor’s Conference the year before, were prized for their historical value.

The sterling silver tea service had been used during inaugural balls ever since the Idaho had been decommissioned in 1946. It was irreplaceable.

In the Idaho burglary there was no handy scaffolding for the thieves to climb. They brought a ladder with them. One of the burglars—perhaps it was a single burglar—climbed up to reach a window on an enclosed porch, broke the window, then crawled in. This may have been a clue. The window was one foot by one-and-a-half feet, meaning the culprit must have been small.

Once inside the thief or thieves smashed the display case glass to get to the tea set. Police speculated that they used the punch bowl from the set as a basket, piling the rest of the loot inside. They went out a door and fled northeast across Julia Davis Park, marking their route when they dropped a serving tray from the set, not bothering to retrieve it.

And that, sadly, is the end of the story. None of the silver from either robbery was ever recovered. It was likely melted down and cashed in.

The tea service from the USS Idaho had a history with the WWII ship, but its connection to Idaho went even further back. The service was donated by the people of Idaho for use on the predecessor ship, the USS Idaho in 1912, so it had served on two ships bearing that name.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

Published on May 06, 2024 04:00

May 5, 2024

The Blackfoot Sugar Factory

Let’s start today’s post, which first ran as a column in the Blackfoot Morning News, with a pop quiz. What three iconic Blackfoot facilities were built on sand dunes? The answer, according to Idaho Republican editor Byrd Trego, writing in Volume 1, Number 1, of that paper in July 1904, is that the original Bingham County Courthouse, the Idaho Insane Asylum, and the Blackfoot sugar factory were all built on sand dunes.

That came up because construction of the sugar factory was just getting underway that year. By some accounts, which I’ve been unable to confirm, it was supposed to have been built the year before, but the project was hijacked. According to that story several men from Blackfoot had purchased the equipment for a sugar factory, but some scoundrels who wanted it for themselves changed the paperwork on the shipment and had it unloaded near the town of Lincoln where a sugar factory was built.

Putting possible treachery aside, the sugar factory that became a Blackfoot symbol was built in 1904. In August of that year, the local paper was reporting that “The carbonators, evaporators, fourteen diffusion batteries, all juice pumps and the entire boiler plan are now being placed in position.” Most of that equipment, manufactured in France, had been purchased from a bankrupt factory in Binghamton, New York.

Horse drawn Fresno scrapers leveled the sand dune prior to construction and carved out a reservoir for storing 70,000 tons of beet pulp. During construction about 180 men were put to work, 40 of them on the masonry alone. Many of those concentrated on bricking up the 135-foot smokestack that would be a Blackfoot icon for more than a hundred years.

In September the paper reported that there would be ancillary beet dumps placed in Firth, Moreland, and Wapello. Managers at the plant were showing local beet farmers how to construct wagon racks that would work best with the equipment going in. Those wagons along with train cars would be using one of several elevated trestles that facilitated dumping beets into huge piles.

The factory, with mostly French equipment, was an international operation. To get things rolling they had ordered half a carload of muriatic acid, 28,000 pounds of brimstone, 10,000 yards of cotton filtering cloth, 500 beet knives from Germany, and 8,000 sheets of parchment from Belgium.

On September 19, 1904, a strike of workers building the factory threatened to stop progress. Forty-six men said they would walk out if they didn’t get an additional nickel an hour in wages. Management rejected their demands. Thirty-seven of them walked off the job and left town.

The mini strike didn’t impact progress much. The factory was ready for the beets to start rolling in on Wednesday, November 9 at 1 pm, about a week ahead of schedule.

The Blackfoot plant could process 600 tons of beets a day, at first. That increased to an 800-ton daily capacity in 1911. The factory was closed for the season in 1910 because curly top had infected area beets. It closed, again, in 1922, 1926, and 1927 for the same reason. Its peak year of production was 1940, when it processed 104,206 tons of beets and turned out 368,007 bags of sugar.

The factory closed for good in 1948 and the equipment was dismantled in 1952. It served as a sugar storage warehouse for many years, starting in 1954. The iconic smokestack, which stood for 112 years, came down in 2016.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

That came up because construction of the sugar factory was just getting underway that year. By some accounts, which I’ve been unable to confirm, it was supposed to have been built the year before, but the project was hijacked. According to that story several men from Blackfoot had purchased the equipment for a sugar factory, but some scoundrels who wanted it for themselves changed the paperwork on the shipment and had it unloaded near the town of Lincoln where a sugar factory was built.

Putting possible treachery aside, the sugar factory that became a Blackfoot symbol was built in 1904. In August of that year, the local paper was reporting that “The carbonators, evaporators, fourteen diffusion batteries, all juice pumps and the entire boiler plan are now being placed in position.” Most of that equipment, manufactured in France, had been purchased from a bankrupt factory in Binghamton, New York.

Horse drawn Fresno scrapers leveled the sand dune prior to construction and carved out a reservoir for storing 70,000 tons of beet pulp. During construction about 180 men were put to work, 40 of them on the masonry alone. Many of those concentrated on bricking up the 135-foot smokestack that would be a Blackfoot icon for more than a hundred years.

In September the paper reported that there would be ancillary beet dumps placed in Firth, Moreland, and Wapello. Managers at the plant were showing local beet farmers how to construct wagon racks that would work best with the equipment going in. Those wagons along with train cars would be using one of several elevated trestles that facilitated dumping beets into huge piles.

The factory, with mostly French equipment, was an international operation. To get things rolling they had ordered half a carload of muriatic acid, 28,000 pounds of brimstone, 10,000 yards of cotton filtering cloth, 500 beet knives from Germany, and 8,000 sheets of parchment from Belgium.

On September 19, 1904, a strike of workers building the factory threatened to stop progress. Forty-six men said they would walk out if they didn’t get an additional nickel an hour in wages. Management rejected their demands. Thirty-seven of them walked off the job and left town.

The mini strike didn’t impact progress much. The factory was ready for the beets to start rolling in on Wednesday, November 9 at 1 pm, about a week ahead of schedule.

The Blackfoot plant could process 600 tons of beets a day, at first. That increased to an 800-ton daily capacity in 1911. The factory was closed for the season in 1910 because curly top had infected area beets. It closed, again, in 1922, 1926, and 1927 for the same reason. Its peak year of production was 1940, when it processed 104,206 tons of beets and turned out 368,007 bags of sugar.

The factory closed for good in 1948 and the equipment was dismantled in 1952. It served as a sugar storage warehouse for many years, starting in 1954. The iconic smokestack, which stood for 112 years, came down in 2016.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

Published on May 05, 2024 04:00

May 4, 2024

Bancroft's Evening Grocery

Note: My friend, Steve Bancroft, the subject of this post from several months ago, passed away this week. His sister, Carol, passed away a few months ago. I repost it here today in their honor.

Only the old-timers remember Bancroft’s Evening Grocery. It was located at 1523 Main Street in Boise. The building there today houses Baldwin Lock and Key and the old Sav-On Cafe.

The grocery operated from 1928 until 1942. Yet, memories of the store are fresh in the minds of at least two people, Steve Bancroft and his older sister Carol. Their parents owned the Bancroft Evening Store, and the siblings helped run it from the time they were big enough to look over the counter. Steve, a WWII vet, is 98. His sister, Carol is 101.

I see Steve nearly every day when I go to exercise at the West Valley Y. He’s a retired accountant, former Twin Falls City Councilman, and an old-school Republican who has little use for the antics of the extreme right in today’s party.

Steve remembers that, “We lived in the living quarters which were one big room with a large round table in the center, a Majestic Coal range in one corner, and opposite was a bathtub with just a curtain around it, and the sink was in the center of the east wall, and the door to the back yard in the southeast corner. Mom had flower pots in the space between the sink and the door. The flower pots were on what were wood orange crates. The flowers were in old red earthen pots. The main type of flowers were Chrysanthemums. I guess it was the orange crates and the red pots and the knobby plants but I have never really liked house plants since. Between the sink and the bathtub there was a door into two bedrooms, one down stairs and one up.”

Before the bedrooms were added, Steve and his brother Kieth slept in a shed behind the store. Then, in 1936 the family bought a house on Mountain View Drive. Even then Chester and Eva Bancroft, the parents, remained attached to Bancroft’s Evening Store. “As my folks felt they could not be away from the store at night, they remained there, and the three kids drove out to the house to sleep,” Steve said. “Back in the morning for breakfast and the rest of the day until about 10:00 PM back to the house to sleep. This was the plan until 1942 when the store was sold, and we all lived in the house on Mountain View Drive.”

Bancroft’s Evening Store was so named because it was open until 10 at night, something not common at that time. It was also open on Sundays. That practice bumped up against the county’s “blue laws” at the time, so the proprietors had to pay an occasional fine for selling beer on a Sunday.

Steve Bancroft with Rick Just, January 2024.

Steve Bancroft with Rick Just, January 2024.  The Bancrofts inside their store, circa 1931.

The Bancrofts inside their store, circa 1931.

Standing in front of the Bancroft’s Evening Store are, left to right, Chester, Carol, Steve, Eva, and Keith Bancroft. The picture was taken in about 1931.

Standing in front of the Bancroft’s Evening Store are, left to right, Chester, Carol, Steve, Eva, and Keith Bancroft. The picture was taken in about 1931.

Only the old-timers remember Bancroft’s Evening Grocery. It was located at 1523 Main Street in Boise. The building there today houses Baldwin Lock and Key and the old Sav-On Cafe.

The grocery operated from 1928 until 1942. Yet, memories of the store are fresh in the minds of at least two people, Steve Bancroft and his older sister Carol. Their parents owned the Bancroft Evening Store, and the siblings helped run it from the time they were big enough to look over the counter. Steve, a WWII vet, is 98. His sister, Carol is 101.

I see Steve nearly every day when I go to exercise at the West Valley Y. He’s a retired accountant, former Twin Falls City Councilman, and an old-school Republican who has little use for the antics of the extreme right in today’s party.

Steve remembers that, “We lived in the living quarters which were one big room with a large round table in the center, a Majestic Coal range in one corner, and opposite was a bathtub with just a curtain around it, and the sink was in the center of the east wall, and the door to the back yard in the southeast corner. Mom had flower pots in the space between the sink and the door. The flower pots were on what were wood orange crates. The flowers were in old red earthen pots. The main type of flowers were Chrysanthemums. I guess it was the orange crates and the red pots and the knobby plants but I have never really liked house plants since. Between the sink and the bathtub there was a door into two bedrooms, one down stairs and one up.”

Before the bedrooms were added, Steve and his brother Kieth slept in a shed behind the store. Then, in 1936 the family bought a house on Mountain View Drive. Even then Chester and Eva Bancroft, the parents, remained attached to Bancroft’s Evening Store. “As my folks felt they could not be away from the store at night, they remained there, and the three kids drove out to the house to sleep,” Steve said. “Back in the morning for breakfast and the rest of the day until about 10:00 PM back to the house to sleep. This was the plan until 1942 when the store was sold, and we all lived in the house on Mountain View Drive.”

Bancroft’s Evening Store was so named because it was open until 10 at night, something not common at that time. It was also open on Sundays. That practice bumped up against the county’s “blue laws” at the time, so the proprietors had to pay an occasional fine for selling beer on a Sunday.

Steve Bancroft with Rick Just, January 2024.

Steve Bancroft with Rick Just, January 2024.  The Bancrofts inside their store, circa 1931.

The Bancrofts inside their store, circa 1931.

Standing in front of the Bancroft’s Evening Store are, left to right, Chester, Carol, Steve, Eva, and Keith Bancroft. The picture was taken in about 1931.

Standing in front of the Bancroft’s Evening Store are, left to right, Chester, Carol, Steve, Eva, and Keith Bancroft. The picture was taken in about 1931.

Published on May 04, 2024 05:24

May 3, 2024

The Magnificent Nat

Perhaps the first example of magnificent architecture in the Treasure Valley—before the valley had that name—was Boise’s Natatorium. Dedicated in 1892, the “Nat” cost $87,000 to build. Taxpayers in a town of 2500 would have been hard pressed to build a public pool of that grandeur. It was built as a money-making enterprise by the Boise Artesian Hot & Cold Water Company. Soon, houses along Warm Springs Avenue were advertising that they were heated with “Natatorium water.”

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

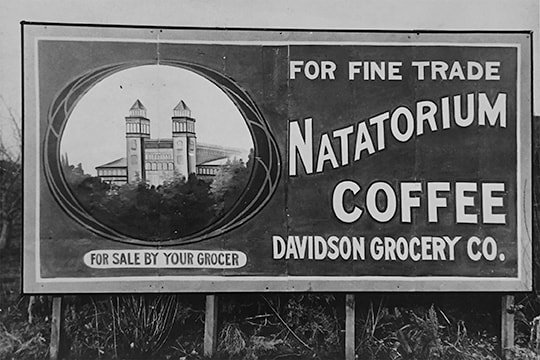

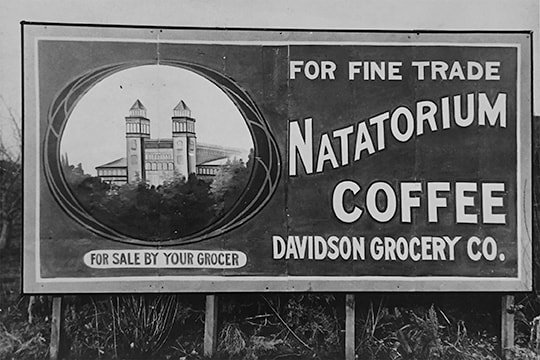

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)  Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)  Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Published on May 03, 2024 04:00

May 2, 2024

Where's Your Key?

Belgian inventor John Joseph Merlin was a couple of centuries ahead of his time when he patented the first roller skate in 1760. His skates were just ice skates with rollers replacing the blade. He had basically invented the Rollerblade, not the roller skate. They weren’t popular because they were hard to steer and even harder to stop.

What we think of today as a roller skate came along in 1863, when James Plimpton of Massachusetts invented the familiar four-wheel design we know today. It was easier to turn because each wheel turned independently, allowing one to turn by putting one’s weight to one side of the skate. To say that they caught on would be an understatement. By 1871, even that outpost of civilization, Boise, had a skating rink.

Ads for the roller-skating rink at Templar Hall proclaimed that one could skate on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays during specified hours, with a “special assembly for the ladies” each of those days from 1 to 3 pm. After paying a quarter for admission you could pay another quarter to rent skates, if you didn’t have a pair of your own.

The rink pointed out that they had “the exclusive right for Plimpton’s Patent Roller Skates for Idaho Territory, same as used at the Pavilion Rink, San Francisco.”

In 1884 another rink opened in the city for “a multitude of excellent manipulators of the rollers” according to The Statesman. The rink was located in the newly converted opera house, and reportedly well managed. “In the evening the crowd was so large that the greatest precaution was necessary in order to preserve due regularity in the movements of skaters and Mr. P. F. Beal performed the duty of floor manager with commendable care and courtesy.”

A few mishaps were bound to occur. “The number of new beginners present was large and some falls were the result of too much haste and confidence.” Some were eager to take advantage of the newbies of a certain gender. “The young gentlemen who were masters of the rollers took the greatest imaginable delight in teaching young lady beginners the art and evidently the rink will be ‘all the rage’ this winter.”

But all was not perfection in the world of skating. A few weeks before statehood in 1890 The Statesman reported that “The walk to the Capitol from the corner of Seventh and Jefferson was taken possession of by boys with roller skates before it had become sufficiently hardened, and as a result it is very much creased and disfigured.” Cracks had also appeared in the concrete, perhaps likewise caused by unrestrained hooligan skaters. “Those cracks and creases will probably be an ‘eye-sore’ for years,” the paper concluded.

Today the wheels of skateboards are more often blamed for damage, real or imagined, but roller skates and enticing stretches of concrete are still with us.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

What we think of today as a roller skate came along in 1863, when James Plimpton of Massachusetts invented the familiar four-wheel design we know today. It was easier to turn because each wheel turned independently, allowing one to turn by putting one’s weight to one side of the skate. To say that they caught on would be an understatement. By 1871, even that outpost of civilization, Boise, had a skating rink.

Ads for the roller-skating rink at Templar Hall proclaimed that one could skate on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays during specified hours, with a “special assembly for the ladies” each of those days from 1 to 3 pm. After paying a quarter for admission you could pay another quarter to rent skates, if you didn’t have a pair of your own.

The rink pointed out that they had “the exclusive right for Plimpton’s Patent Roller Skates for Idaho Territory, same as used at the Pavilion Rink, San Francisco.”

In 1884 another rink opened in the city for “a multitude of excellent manipulators of the rollers” according to The Statesman. The rink was located in the newly converted opera house, and reportedly well managed. “In the evening the crowd was so large that the greatest precaution was necessary in order to preserve due regularity in the movements of skaters and Mr. P. F. Beal performed the duty of floor manager with commendable care and courtesy.”

A few mishaps were bound to occur. “The number of new beginners present was large and some falls were the result of too much haste and confidence.” Some were eager to take advantage of the newbies of a certain gender. “The young gentlemen who were masters of the rollers took the greatest imaginable delight in teaching young lady beginners the art and evidently the rink will be ‘all the rage’ this winter.”

But all was not perfection in the world of skating. A few weeks before statehood in 1890 The Statesman reported that “The walk to the Capitol from the corner of Seventh and Jefferson was taken possession of by boys with roller skates before it had become sufficiently hardened, and as a result it is very much creased and disfigured.” Cracks had also appeared in the concrete, perhaps likewise caused by unrestrained hooligan skaters. “Those cracks and creases will probably be an ‘eye-sore’ for years,” the paper concluded.

Today the wheels of skateboards are more often blamed for damage, real or imagined, but roller skates and enticing stretches of concrete are still with us.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

Published on May 02, 2024 04:00

May 1, 2024

Russell and the Rodeo

So, I was doing a little research on rodeos the other day because someone had a question about the Caldwell Night Rodeo (which I’ll address in a later post). I dug out my copy of Louise Shadduck’s book,

Rodeo Idaho

. As is usually the case when I set out to research something, I’m presented with rabbit trail after rabbit trail that I want to sniff down. For instance, did you know that Jane Russell came to Idaho to relax after making her first movie,

Outlaw

? It was a 1943 Howard Hughes film about Billy the Kid. Russell spent some time in Island Park where one of the locals pulled together a rodeo at her request. Shadduck’s book has a couple of pictures. Oh, and maybe it’s time I wrote about Shadduck herself, journalist and political powerbroker from Coeur d’Alene.

Shadduck’s book mentioned a couple of contenders for the first American rodeo, one in Prescott, Arizona in 1888 and Cheyenne’s Frontier Days, which started in 1897. She claimed that Idaho’s first rodeo began in 1906. That would become famous as Nampa’s Snake River Stampede. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe Shadduck, but I thought I’d do my own quick search through Idaho papers, just to see if I found a mention of an earlier rodeo.

Wow! Right away I came up with one in or around Albion from 1880. Then, I started seeing others in subsequent years from all around the state. In a couple of minutes, I went from elation to minor disappointment. Yes, Idaho had earlier rodeos. Many of them. They weren’t going to count, though, because the early papers were using the word in its original meaning, which is roundup in Spanish. The papers were reporting on the annual roundups of cattle in certain areas, which were annual events. They still are, but newspapers have a lot more to talk about, these days.

So, I hadn’t made a startling discovery about the history of rodeos. Still, it gave me the opportunity to illustrate this post with a publicity photo of Jane Russell from Outlaw, which was probably what drew you to this story in the first place. ‘Fess up!

Shadduck’s book mentioned a couple of contenders for the first American rodeo, one in Prescott, Arizona in 1888 and Cheyenne’s Frontier Days, which started in 1897. She claimed that Idaho’s first rodeo began in 1906. That would become famous as Nampa’s Snake River Stampede. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe Shadduck, but I thought I’d do my own quick search through Idaho papers, just to see if I found a mention of an earlier rodeo.

Wow! Right away I came up with one in or around Albion from 1880. Then, I started seeing others in subsequent years from all around the state. In a couple of minutes, I went from elation to minor disappointment. Yes, Idaho had earlier rodeos. Many of them. They weren’t going to count, though, because the early papers were using the word in its original meaning, which is roundup in Spanish. The papers were reporting on the annual roundups of cattle in certain areas, which were annual events. They still are, but newspapers have a lot more to talk about, these days.

So, I hadn’t made a startling discovery about the history of rodeos. Still, it gave me the opportunity to illustrate this post with a publicity photo of Jane Russell from Outlaw, which was probably what drew you to this story in the first place. ‘Fess up!

Published on May 01, 2024 04:00