Rick Just's Blog, page 26

April 20, 2024

A Little Skiing History

We know Idaho has some terrific skiing history. Sun Valley was the first destination ski resort and boasted the first chairlift. Bogus Basin is the largest nonprofit of its kind in the country. But skiing was everywhere in Idaho in the early days of the sport.

A great source of skiing history is Ski the Great Potato * by Margaret Fuller, Doug Fuller, and Jerry Painter. They cover 21 existing ski areas in the state and give a hat-tip to 72 areas that have since, let’s say, melted away.

Have you seen the big M on the side of the hill overlooking the town of Montpelier? That was a local skiing site in the 60s and 70s. The city ran a rope tow for skiers there. Many sledders used the hill, but they had to trudge up without benefit of a tow.

Getting up a hill was always the challenge. Rope tows were a popular method. They used an old Ford engine on the rope tow at Pine Street Hill outside of Sandpoint in the 1940s. Later they used a Sweden Speed Tow. The portability of those units, which had engines mounted on toboggans, made them popular for little ski hills all over the state. They cost less than $350.

Downhill skiing wasn’t enough of a thrill for some. In 1924 the City of McCall built a ski jump on land owned by Clem Blackwell a couple of miles out of town. Blackwell’s Jump, as it was called, was the main feature of the first Winter Carnival. In the early years McCall didn’t have the lodging options it does today. Carnival participants would come up from Boise on a train, then ride in logging sleds pulled by horses out to where the jump was. After spending the day enjoying the flying skiers, they rode back into town and slept on the train.

Ski jumping wasn’t the only event at the Winter Carnival. They had cross-country skiing and snowshoe races, dogsled racing, and ski-joring. Spectators could become participants in at least one recreational pursuit, if they wished. Snowplanes, basically airplane engines—props spinning—were bolted to skis or toboggans. The brave could catch a thrilling ride. One could theoretically ride to the top of a hill and ski down, but that didn’t catch on.

Skiers on a rope tow at Bogus Basin, circa 1950. Photo from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Skiers on a rope tow at Bogus Basin, circa 1950. Photo from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.  Ad for a Sweden Speed Ski Tow. Note that they were made by the Sweden Freezer Manufacturing Company of Seattle. The units were a bit of a sideline for them.

Ad for a Sweden Speed Ski Tow. Note that they were made by the Sweden Freezer Manufacturing Company of Seattle. The units were a bit of a sideline for them.

A great source of skiing history is Ski the Great Potato * by Margaret Fuller, Doug Fuller, and Jerry Painter. They cover 21 existing ski areas in the state and give a hat-tip to 72 areas that have since, let’s say, melted away.

Have you seen the big M on the side of the hill overlooking the town of Montpelier? That was a local skiing site in the 60s and 70s. The city ran a rope tow for skiers there. Many sledders used the hill, but they had to trudge up without benefit of a tow.

Getting up a hill was always the challenge. Rope tows were a popular method. They used an old Ford engine on the rope tow at Pine Street Hill outside of Sandpoint in the 1940s. Later they used a Sweden Speed Tow. The portability of those units, which had engines mounted on toboggans, made them popular for little ski hills all over the state. They cost less than $350.

Downhill skiing wasn’t enough of a thrill for some. In 1924 the City of McCall built a ski jump on land owned by Clem Blackwell a couple of miles out of town. Blackwell’s Jump, as it was called, was the main feature of the first Winter Carnival. In the early years McCall didn’t have the lodging options it does today. Carnival participants would come up from Boise on a train, then ride in logging sleds pulled by horses out to where the jump was. After spending the day enjoying the flying skiers, they rode back into town and slept on the train.

Ski jumping wasn’t the only event at the Winter Carnival. They had cross-country skiing and snowshoe races, dogsled racing, and ski-joring. Spectators could become participants in at least one recreational pursuit, if they wished. Snowplanes, basically airplane engines—props spinning—were bolted to skis or toboggans. The brave could catch a thrilling ride. One could theoretically ride to the top of a hill and ski down, but that didn’t catch on.

Skiers on a rope tow at Bogus Basin, circa 1950. Photo from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Skiers on a rope tow at Bogus Basin, circa 1950. Photo from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.  Ad for a Sweden Speed Ski Tow. Note that they were made by the Sweden Freezer Manufacturing Company of Seattle. The units were a bit of a sideline for them.

Ad for a Sweden Speed Ski Tow. Note that they were made by the Sweden Freezer Manufacturing Company of Seattle. The units were a bit of a sideline for them.

Published on April 20, 2024 04:00

April 19, 2024

Poor Coyote's Cabin

Sometimes the story is that there’s not much of a story there. I ran across this photo of “Poor Coyote’s Cabin” while looking for whoknowswhat in the Library of Congress digital collection. That humble little cabin huddled there beneath a highway overpass intrigued me.

Beth Erdey, PhD, archivist for the Nez Perce National Historic Park at Spalding quickly calmed my curiosity. She sent me some documents about the cabin, including a query from 1986 asking if it might be eligible for a National Register of Historic Places listing. The answer: Not really.

There simply wasn’t enough information about the old cabin to justify its inclusion. It was moved in 1936 from what may have been its original location in Coyote’s Gulch to a site near Spalding, then moved at least once more to the site beneath the abandoned highway overpass near the NPS visitor center. At least one of the moves was not done correctly and some logs were reassembled out of order. Because of those moves the cabin was no longer in its historical setting and it didn’t retain the integrity of workmanship one would like to see on the National Register.

Even so, the cabin might have made the cut if we knew something more about it. It was probably built sometime after 1880. We don’t know who built it or even where it was originally located, but a Nez Perce Indian named Poor Coyote lived in it from 1895 until his death in 1915. Next to nothing is known about Poor Coyote, save for his evocative name.

The 1936 move was done by Joe Evans. He and his wife, Pauline, operated a museum at Spalding and they used the cabin as part of their exhibit. It was called the “Jackson Sundown” cabin by Joe and Pauline, and artifacts purportedly belonging to the famous rodeo rider were displayed there. There’s no evidence Sundown had anything to do with the cabin, and the veracity of the “curators” is questionable. They often didn’t let provenance get in the way of a good story.

In 1965 or 1970 (records are unclear) the cabin was again moved and placed beneath the old Highway 95 overpass, perhaps to protect it from the elements. NPS deconstructed the cabin in 1990, saving some elements of it for the museum collection.

So, little but that curious name, Poor Coyote, remains. We are left to wonder who he was and what his name might have meant to those who gave it to him. Was he not a very good coyote? Was he underprivileged? Are we to simply feel sorry for him? If someone out there in internet lands knows more, please share what you know with us.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Beth Erdey, PhD, archivist for the Nez Perce National Historic Park at Spalding quickly calmed my curiosity. She sent me some documents about the cabin, including a query from 1986 asking if it might be eligible for a National Register of Historic Places listing. The answer: Not really.

There simply wasn’t enough information about the old cabin to justify its inclusion. It was moved in 1936 from what may have been its original location in Coyote’s Gulch to a site near Spalding, then moved at least once more to the site beneath the abandoned highway overpass near the NPS visitor center. At least one of the moves was not done correctly and some logs were reassembled out of order. Because of those moves the cabin was no longer in its historical setting and it didn’t retain the integrity of workmanship one would like to see on the National Register.

Even so, the cabin might have made the cut if we knew something more about it. It was probably built sometime after 1880. We don’t know who built it or even where it was originally located, but a Nez Perce Indian named Poor Coyote lived in it from 1895 until his death in 1915. Next to nothing is known about Poor Coyote, save for his evocative name.

The 1936 move was done by Joe Evans. He and his wife, Pauline, operated a museum at Spalding and they used the cabin as part of their exhibit. It was called the “Jackson Sundown” cabin by Joe and Pauline, and artifacts purportedly belonging to the famous rodeo rider were displayed there. There’s no evidence Sundown had anything to do with the cabin, and the veracity of the “curators” is questionable. They often didn’t let provenance get in the way of a good story.

In 1965 or 1970 (records are unclear) the cabin was again moved and placed beneath the old Highway 95 overpass, perhaps to protect it from the elements. NPS deconstructed the cabin in 1990, saving some elements of it for the museum collection.

So, little but that curious name, Poor Coyote, remains. We are left to wonder who he was and what his name might have meant to those who gave it to him. Was he not a very good coyote? Was he underprivileged? Are we to simply feel sorry for him? If someone out there in internet lands knows more, please share what you know with us.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Poor Coyote’s cabin in its final resting place beneath an abandoned Highway 95 overpass near Spalding. Library of Congress photo.

Published on April 19, 2024 04:00

April 18, 2024

Mrs. Borah and "Aurora Borah Alice"

Our appetite for scandal seems not to diminish with history’s passing years. If you are above it, give yourself a gold star and quit reading now.

Okay, anyone still with me?

William Borah was a Boise attorney who went up against Clarence Darrow as one of the prosecutors of “Big” Bill Haywood. Haywood was acquitted but the trial brought national fame to Borah.

At the time of the trial in 1907, Borah had already been selected as a U.S. Senator from Idaho. That was when legislatures named senators. He had time for the trial because Congress didn’t start their sessions until December in those days. Borah replaced the vehemently anti-Mormon Fred T. Dubois. No scandal there, though no doubt there was some backroom intrigue, par for the course in elections on the floor.

No scandal, either, when Borah was reelected by the Legislature in 1912, or when he was elected and re-elected by the citizens in Idaho in 1918, 1924, 1930, and 1936.

Borah started showing up on presidential nomination ballots at Republican National Conventions beginning in 1916. He got the most votes in the Presidential Primaries in 1936, but Alf Landon won the nomination that year at the convention. Again, no scandal.

The scandal wasn’t on the political side for Borah, but on the personal side.

In 1895, Borah married the daughter of Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell. Mary McConnell was a lovely, tiny woman who during their years in Washington was often referred to as “Little Borah.” They had no children. And there’s the scandal. The senator apparently did.

Rumors of philandering dogged Senator Borah for years. Of particular interest for this particular scandal, was an affair he had with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt that was later confirmed by her diary entries.

Alice was married to Representative Nicholas Longworth III, who served as Speaker of the House. The daughter in question was ultimately named Paulina, but Alice, who had a wicked sense of humor, reportedly toyed with the idea of naming her Deborah. Deborah could have been read as De Borah, you see. According to H.W. Brands’ book A Traitor to His Class ,* which is largely about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Paulina was often referred to by D.C. wags as “Aurora Borah Alice.”

And, there you have it. Don’t say you weren’t warned. Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Okay, anyone still with me?

William Borah was a Boise attorney who went up against Clarence Darrow as one of the prosecutors of “Big” Bill Haywood. Haywood was acquitted but the trial brought national fame to Borah.

At the time of the trial in 1907, Borah had already been selected as a U.S. Senator from Idaho. That was when legislatures named senators. He had time for the trial because Congress didn’t start their sessions until December in those days. Borah replaced the vehemently anti-Mormon Fred T. Dubois. No scandal there, though no doubt there was some backroom intrigue, par for the course in elections on the floor.

No scandal, either, when Borah was reelected by the Legislature in 1912, or when he was elected and re-elected by the citizens in Idaho in 1918, 1924, 1930, and 1936.

Borah started showing up on presidential nomination ballots at Republican National Conventions beginning in 1916. He got the most votes in the Presidential Primaries in 1936, but Alf Landon won the nomination that year at the convention. Again, no scandal.

The scandal wasn’t on the political side for Borah, but on the personal side.

In 1895, Borah married the daughter of Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell. Mary McConnell was a lovely, tiny woman who during their years in Washington was often referred to as “Little Borah.” They had no children. And there’s the scandal. The senator apparently did.

Rumors of philandering dogged Senator Borah for years. Of particular interest for this particular scandal, was an affair he had with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt that was later confirmed by her diary entries.

Alice was married to Representative Nicholas Longworth III, who served as Speaker of the House. The daughter in question was ultimately named Paulina, but Alice, who had a wicked sense of humor, reportedly toyed with the idea of naming her Deborah. Deborah could have been read as De Borah, you see. According to H.W. Brands’ book A Traitor to His Class ,* which is largely about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Paulina was often referred to by D.C. wags as “Aurora Borah Alice.”

And, there you have it. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Published on April 18, 2024 04:00

April 17, 2024

Radio Earworms

And now, something completely different. Thanks to Art Gregory of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation, this was our first audio-oriented post.

If you were listening to radio in the 1960s in the Treasure Valley, you might remember the commercials from this short sample, featuring: Frosty Dog!Black Forrest Archery CenterYoung’s Dairy All Jersey MilkBank of IdahoIdaho First National BankWestern Idaho State Fair And, here’s the KIDO City of Trees jingle from 1961, featuring Gib Hochstrasser and Jeanie Hackett, cum Hochstrasser.

In 1962, KFXD had a song about the city where the station was located, which might have been called, Nampa-Nampa. Or, once you’ve heard it, you may think of something to call it yourself. Be kind.

And finally, from 1978, KFXD’s I’ve Got a Song to Sing jingle, just a tad reminiscent of Coke jingles of the time.

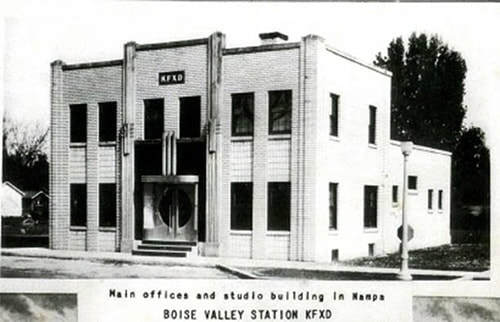

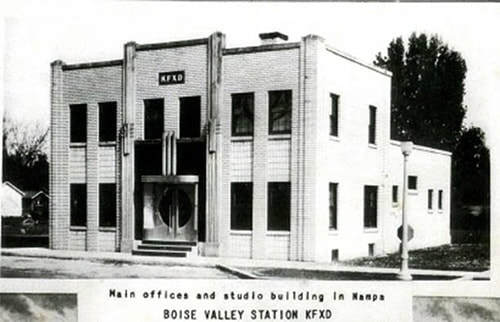

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping to include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. It looks much the same today.

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping to include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. It looks much the same today.

If you were listening to radio in the 1960s in the Treasure Valley, you might remember the commercials from this short sample, featuring: Frosty Dog!Black Forrest Archery CenterYoung’s Dairy All Jersey MilkBank of IdahoIdaho First National BankWestern Idaho State Fair And, here’s the KIDO City of Trees jingle from 1961, featuring Gib Hochstrasser and Jeanie Hackett, cum Hochstrasser.

In 1962, KFXD had a song about the city where the station was located, which might have been called, Nampa-Nampa. Or, once you’ve heard it, you may think of something to call it yourself. Be kind.

And finally, from 1978, KFXD’s I’ve Got a Song to Sing jingle, just a tad reminiscent of Coke jingles of the time.

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping to include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. It looks much the same today.

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping to include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. It looks much the same today.

Published on April 17, 2024 04:00

April 16, 2024

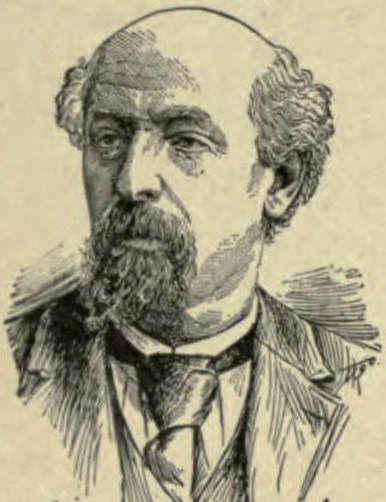

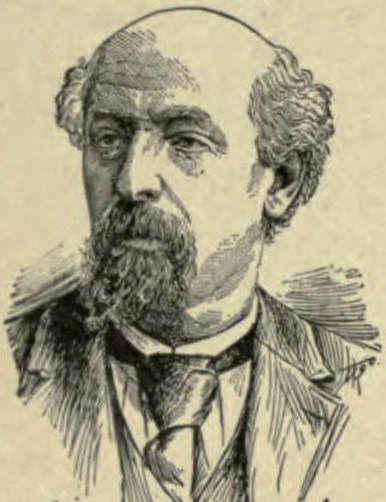

Idaho's Second Governor

George Shoup is celebrated as Idaho’s first governor. He was also the state’s last territorial governor and one of its first senators. Setting aside some disturbing Shoup history, let’s take a minute to examine his term as the state’s first governor. Well, not examine it, exactly, but measure it. George Shoup was the governor of the State of Idaho for 79 days. As the territorial governor he had agreed to stay on as the state’s governor only with the understanding that he would soon be a US senator, selected in those days by state legislatures. Shoup hand-picked his lieutenant governor knowing full well the man would be filling his gubernatorial shoes when he packed up for Washington, DC.

We don’t hear much about Norman B. Willey, Idaho’s second governor. That’s too bad, because it was really on his watch that most of the details of transition from territory to state took place. It was during his term that state agencies were set up and Idaho got its state seal. He served from December 18, 1890 to January 2, 1893. His political career, which included a term on the Idaho County school board, stints as an Idaho County commissioner and county treasurer, and several terms as a territorial legislator, came to an end when he did not win his party’s nomination for a second term as governor.

Willey had come to Idaho as a miner, and he left the state to become a mine superintendent in California. Things went downhill for him from there. He suffered a string of setbacks. Hearing of his financial situation, the Legislature appropriated $1200 to send to him as something of retirement gift. Then he fell from the public conscious until the headlines read “Former Governor Dies as a Pauper.”

Governor Willey had passed away in a Kansas City poor house after dropping out of sight for a number of years. To add a probably unintentional sting to his ignominious end, the Blackfoot Republican misspelled Norman B. Willey’s name in the announcement of his death. He became “Normal” B. Willey.

We don’t hear much about Norman B. Willey, Idaho’s second governor. That’s too bad, because it was really on his watch that most of the details of transition from territory to state took place. It was during his term that state agencies were set up and Idaho got its state seal. He served from December 18, 1890 to January 2, 1893. His political career, which included a term on the Idaho County school board, stints as an Idaho County commissioner and county treasurer, and several terms as a territorial legislator, came to an end when he did not win his party’s nomination for a second term as governor.

Willey had come to Idaho as a miner, and he left the state to become a mine superintendent in California. Things went downhill for him from there. He suffered a string of setbacks. Hearing of his financial situation, the Legislature appropriated $1200 to send to him as something of retirement gift. Then he fell from the public conscious until the headlines read “Former Governor Dies as a Pauper.”

Governor Willey had passed away in a Kansas City poor house after dropping out of sight for a number of years. To add a probably unintentional sting to his ignominious end, the Blackfoot Republican misspelled Norman B. Willey’s name in the announcement of his death. He became “Normal” B. Willey.

Published on April 16, 2024 04:00

April 15, 2024

The Military Fort Hall

If you’ve lived in Idaho for a while, you’ve probably been confused at least a couple of times when someone made a reference to Fort Hall. Did they mean the reservation, the town, or the fort? If they meant the fort, one could certainly ask, which fort?

Fort Hall began as a fur trading post in 1834. It was located on the Snake River in what is now Bannock County, about 11 miles west of the town of Fort Hall. It served trappers, then Oregon Trail emigrants, and finally stagecoaches and freighters until it was largely destroyed by a flood in 1863, the year Idaho became a territory.

In May 1870, the US began to build a military fort not far from Blackfoot where Lincoln Creek—a warm water stream—flows into the Blackfoot River, some 40 miles east of the original fur trading site. Its purpose was to “maintain proper control” of some 1200 Indians who then resided on the reservation.

The post, situated on 640 acres, was surrounded by grassy fields, providing ample grazing. There were few trees in the area and none really suited for construction, so the bulk of the timber was shipped in from Truckee River, California, with the remainder of the sawed lumber coming from Corrine, Utah.

If you picture a fort as, well, fortified, you don’t have Fort Hall in mind. Without walls, perimeter wooden buildings arranged around a parade ground defined the installation. Most of the major buildings were put up in 1871.

The fort included a hospital, a commissary building, officer’s quarters, a company barrack, married soldier’s quarters, a guard house, a kitchen, and a mess hall. Ancillary buildings included a blacksmith shop, a carpenter shop, two stables, two granaries, a wagon shed, a harness shop, a saddler’s shop, an icehouse, and a barber shop. Of particular interest to my family was the post bakery, where Emma Bennett (soon to be Emma Just) baked bread for the soldiers.

The military Fort Hall lasted until 1883 when the army abandoned it. The federal government transferred the land to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for use as a residential Indian school. Such schools, which attempted to immerse the indigenous children in white culture, were notoriously brutal. The school on the grounds of the old military fort was as bad as any. Students were torn from their families and forced to attend. Funding was low, so little actual teaching took place. Packed together in unsafe and unsanitary conditions the students were prone to disease. A scarlet fever epidemic in 1891 killed ten of them. There were at least two suicides at the school.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 brought an end to the boarding schools and their policies of forced assimilation. As a result of that act the Lincoln Creek Day School, just a couple of miles from the Fort Hall site, was opened in 1937. It and a couple of other day schools on the reservation were a huge improvement over the boarding school. Kids returned to their families every afternoon. The day school operated only until 1944 when reservation students began attending local public schools.

Both the military Fort Hall site and the Lincoln Creek Day School are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. No buildings from the fort remain on the site. In recent years much work has been done on the nearby school to turn it into a community center for that part of the reservation.

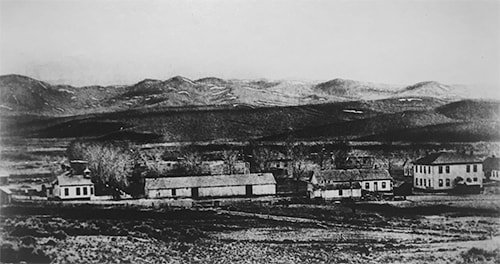

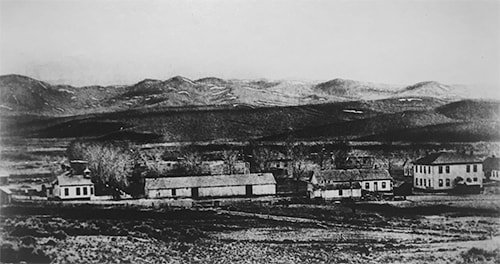

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Fort Hall began as a fur trading post in 1834. It was located on the Snake River in what is now Bannock County, about 11 miles west of the town of Fort Hall. It served trappers, then Oregon Trail emigrants, and finally stagecoaches and freighters until it was largely destroyed by a flood in 1863, the year Idaho became a territory.

In May 1870, the US began to build a military fort not far from Blackfoot where Lincoln Creek—a warm water stream—flows into the Blackfoot River, some 40 miles east of the original fur trading site. Its purpose was to “maintain proper control” of some 1200 Indians who then resided on the reservation.

The post, situated on 640 acres, was surrounded by grassy fields, providing ample grazing. There were few trees in the area and none really suited for construction, so the bulk of the timber was shipped in from Truckee River, California, with the remainder of the sawed lumber coming from Corrine, Utah.

If you picture a fort as, well, fortified, you don’t have Fort Hall in mind. Without walls, perimeter wooden buildings arranged around a parade ground defined the installation. Most of the major buildings were put up in 1871.

The fort included a hospital, a commissary building, officer’s quarters, a company barrack, married soldier’s quarters, a guard house, a kitchen, and a mess hall. Ancillary buildings included a blacksmith shop, a carpenter shop, two stables, two granaries, a wagon shed, a harness shop, a saddler’s shop, an icehouse, and a barber shop. Of particular interest to my family was the post bakery, where Emma Bennett (soon to be Emma Just) baked bread for the soldiers.

The military Fort Hall lasted until 1883 when the army abandoned it. The federal government transferred the land to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for use as a residential Indian school. Such schools, which attempted to immerse the indigenous children in white culture, were notoriously brutal. The school on the grounds of the old military fort was as bad as any. Students were torn from their families and forced to attend. Funding was low, so little actual teaching took place. Packed together in unsafe and unsanitary conditions the students were prone to disease. A scarlet fever epidemic in 1891 killed ten of them. There were at least two suicides at the school.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 brought an end to the boarding schools and their policies of forced assimilation. As a result of that act the Lincoln Creek Day School, just a couple of miles from the Fort Hall site, was opened in 1937. It and a couple of other day schools on the reservation were a huge improvement over the boarding school. Kids returned to their families every afternoon. The day school operated only until 1944 when reservation students began attending local public schools.

Both the military Fort Hall site and the Lincoln Creek Day School are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. No buildings from the fort remain on the site. In recent years much work has been done on the nearby school to turn it into a community center for that part of the reservation.

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on April 15, 2024 04:00

April 14, 2024

Earl Parrot, Idaho Loner

Earl Parrot had a good job as a telegrapher until his eyesight changed. He went color blind in 1898. Those operating a telegraph key had to be able to distinguish the colors on railroad signals and he could no longer do so.

Parrot tried a little prospecting in the Klondike for a bit, but by 1900 he was in Idaho. Exactly when he established his nest on the rim of Impassable Canyon overlooking the Middle Fork of the Salmon River is anyone’s guess, but he was there by 1917 and remained there for most of his remaining 28 years.

The best researched sketch of Earl Parrot’s life can be found in Cort Conley’s entertaining book, Idaho Loners . I got the bulk of this post from that book and encourage you to read it to find out more about Parrot as well as other Idaho loners from Sylvan Hart to Claude Dallas.

Conley quoted Francis Wood who was working on a Forest Service survey crew when he bumped into Parrot. Wood said, “One day we spotted a small cabin and noticed smoke coming from the chimney. We decided to stop and have lunch with the occupant. He was busy at a stove cooking some kind of berries. The mixture had not come to a boil. Above the stove, lying on a shelf, was a big cat. When he saw us he made a pass at the cat, knocking it into the fruit. Reaching into the pot, he pulled the cat out and ran his hand over it, draining the berries back into the pot. He then threw the cat out the door. Needless to say, we did not stay for lunch.”

It seemed that everyone who encountered him came away with a good story about the recluse.

Parrot panned a little gold for his annual trips to civilization (often Shoup) to purchase a few supplies. He raised a garden, had a menagerie of animals worthy of a petting zoo, trapped, and hunted. He lived off the land and wasn’t particularly thrilled when visitors dropped by. Your standard hermit stuff.

Conley’s book has some great photos of Parrot, who is said to have thought getting his picture taken was “a peck of foolishness.” The photo included in this post is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo files. It shows Parrot, on the left, with Frank Swain at Parrot’s cabin.

Earl Parrot passed away in 1945 at age 76 in a Salmon nursing home after a couple of strokes and a lengthy illness.

Parrot tried a little prospecting in the Klondike for a bit, but by 1900 he was in Idaho. Exactly when he established his nest on the rim of Impassable Canyon overlooking the Middle Fork of the Salmon River is anyone’s guess, but he was there by 1917 and remained there for most of his remaining 28 years.

The best researched sketch of Earl Parrot’s life can be found in Cort Conley’s entertaining book, Idaho Loners . I got the bulk of this post from that book and encourage you to read it to find out more about Parrot as well as other Idaho loners from Sylvan Hart to Claude Dallas.

Conley quoted Francis Wood who was working on a Forest Service survey crew when he bumped into Parrot. Wood said, “One day we spotted a small cabin and noticed smoke coming from the chimney. We decided to stop and have lunch with the occupant. He was busy at a stove cooking some kind of berries. The mixture had not come to a boil. Above the stove, lying on a shelf, was a big cat. When he saw us he made a pass at the cat, knocking it into the fruit. Reaching into the pot, he pulled the cat out and ran his hand over it, draining the berries back into the pot. He then threw the cat out the door. Needless to say, we did not stay for lunch.”

It seemed that everyone who encountered him came away with a good story about the recluse.

Parrot panned a little gold for his annual trips to civilization (often Shoup) to purchase a few supplies. He raised a garden, had a menagerie of animals worthy of a petting zoo, trapped, and hunted. He lived off the land and wasn’t particularly thrilled when visitors dropped by. Your standard hermit stuff.

Conley’s book has some great photos of Parrot, who is said to have thought getting his picture taken was “a peck of foolishness.” The photo included in this post is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo files. It shows Parrot, on the left, with Frank Swain at Parrot’s cabin.

Earl Parrot passed away in 1945 at age 76 in a Salmon nursing home after a couple of strokes and a lengthy illness.

Published on April 14, 2024 04:00

April 13, 2024

Smoke in the Craters

Once, while visiting Hawaii, I had the chance to break off a delicate, lacey piece of lava so new it was still warm. Looking out over that fresh flow it struck me how like it was to some of the features in Craters of the Moon National Monument. There are lava flows there so untouched by seed or seedling that they might have happened yesterday.

Little wonder then that people over the years have sometimes been convinced a new eruption was going on. During the dedication of the monument on June 15, 1924 there was one such startling incident. The day was full of speeches from dignitaries such as energetic Idaho promoter Bob Limbert who almost single-handedly created the monument, C.B. Sampson of Sampson Roads fame, Blackfoot Republican publisher Byrd Trego, and Idaho State Automobile Association President T.E. Bliss. Stirring as the oration probably was, it could not match the belching volcano. While the speakers were still speaking spectators spied smoke boiling up from a nearby crater. Some in the gathering began to move briskly away from the smoke, but Commercial Club President Otto Hoebel calmed the crowd by telling them it was just a stunt designed expressly for the occasion by R.M. Kunze, amateur purveyor of pyrotechnics.

It also was smoke, and allegedly the smell of Sulphur that set gandy dancers on edge during the construction of the Oregon Shortline railroad outside of Shoshone in 1882. Reports were that “Smoke and flame of peculiar odor, color, and shape issued from chasms and seams in the lava beds.” The Idaho Statesman also reported that one observer said, “General commotion over the lava fields and unusual agitation of the boiling springs cause many railroad hands to leave, terror stricken. The whole area has the appearance from a distance of being on fire.”

Was the whole area on fire? That is, were workers spotting one or more range fires, never uncommon on the Idaho desert? There were reports of lava glowing at night and even bubbling. Indians from Fort Hall scoffed at the concern of the railroaders, saying that it happened regularly when the devil had a bellyache. There was also a rumor that rival railroaders were starting fires and spreading chemicals around to scare off the Oregon Shortline men. When the rains came, the smoke went away along with the concerns of the workers.

In 1911, reports—if not fresh lava—circulated again. The Blackfoot Republican, published south and a bit east of the lava fields quoted A.E. Byers of Blackfoot as saying smoke and great quantities of gas “rose to great height and spread like an umbrella.” Meanwhile residents who lived near the smoke thought it was just a brush fire.

No doubt many have looked out across that landscape, seeing smoke, perhaps even emanating from one of the three volcanic buttes in the area, and had a moment of pause. At that moment they might not have been comforted by the fact that park rangers speculate the most recent eruption was about 2,000 years ago.

Not an actual working volcano.

Not an actual working volcano.

Little wonder then that people over the years have sometimes been convinced a new eruption was going on. During the dedication of the monument on June 15, 1924 there was one such startling incident. The day was full of speeches from dignitaries such as energetic Idaho promoter Bob Limbert who almost single-handedly created the monument, C.B. Sampson of Sampson Roads fame, Blackfoot Republican publisher Byrd Trego, and Idaho State Automobile Association President T.E. Bliss. Stirring as the oration probably was, it could not match the belching volcano. While the speakers were still speaking spectators spied smoke boiling up from a nearby crater. Some in the gathering began to move briskly away from the smoke, but Commercial Club President Otto Hoebel calmed the crowd by telling them it was just a stunt designed expressly for the occasion by R.M. Kunze, amateur purveyor of pyrotechnics.

It also was smoke, and allegedly the smell of Sulphur that set gandy dancers on edge during the construction of the Oregon Shortline railroad outside of Shoshone in 1882. Reports were that “Smoke and flame of peculiar odor, color, and shape issued from chasms and seams in the lava beds.” The Idaho Statesman also reported that one observer said, “General commotion over the lava fields and unusual agitation of the boiling springs cause many railroad hands to leave, terror stricken. The whole area has the appearance from a distance of being on fire.”

Was the whole area on fire? That is, were workers spotting one or more range fires, never uncommon on the Idaho desert? There were reports of lava glowing at night and even bubbling. Indians from Fort Hall scoffed at the concern of the railroaders, saying that it happened regularly when the devil had a bellyache. There was also a rumor that rival railroaders were starting fires and spreading chemicals around to scare off the Oregon Shortline men. When the rains came, the smoke went away along with the concerns of the workers.

In 1911, reports—if not fresh lava—circulated again. The Blackfoot Republican, published south and a bit east of the lava fields quoted A.E. Byers of Blackfoot as saying smoke and great quantities of gas “rose to great height and spread like an umbrella.” Meanwhile residents who lived near the smoke thought it was just a brush fire.

No doubt many have looked out across that landscape, seeing smoke, perhaps even emanating from one of the three volcanic buttes in the area, and had a moment of pause. At that moment they might not have been comforted by the fact that park rangers speculate the most recent eruption was about 2,000 years ago.

Not an actual working volcano.

Not an actual working volcano.

Published on April 13, 2024 04:00

April 12, 2024

Buildings that Looked Like Food

There is a long, perhaps proud, tradition of building restaurants that look like food in the United States. Food-shaped eating establishments include hot dogs, donuts, ice cream cones, a pig, a tamale, an apple, an orange, a pineapple, a banana, a coffee pot, a milk bottle, a soda bottle, and on and on.

Perhaps all the good café designs that resembled food were all taken when some restaurants started popping up with other odd shapes, an owl, a toad, a shoe, a chili bowl, an airplane, teepees, a flower pot, a sphinx, a piano, a blimp, a cream can, and a derby. That last one gives it away that this was a list just from California.

Idaho was not infested with restaurants that looked like food, nor was it immune. There were at least a couple. Many fondly remember the Chicken Inn, a drive in at 323 11th Avenue North. Offering Nampa’s first curb-side service, the Chicken Inn boasted “clear-finish woodwork and modernistic furnishings” inside with a stucco exterior. That exterior is what people remember. The roof was a chicken hunkered down as if sitting on a nest.

The giant chicken probably distinguished Nampa’s Chicken Inn from the other establishments named the Chicken Inn across the state. There was one in McCall, Jerome, Rupert, and Idaho Falls. Boise had a couple of them, at different times.

The advantage of having a restaurant shaped like a chicken was that you didn’t really have to go into detail about what was on the menu. If you wanted tofu, you went somewhere else.

Coeur d’Alene’s Fish Inn used the same strategy. When you walked into the mouth of that sucker (or trout, or whatever), you knew what you were there for. Built in 1932 it operated until the Fish, clearly out of water, burned in 1996.

Nampa’s Chicken Inn opened in February 1940. Joe and Mary Tycz built the place. Joe was born in Moravia in 1905 and moved to the US with his family when he was seven. He married Mary Salek in 1928. Living in South Dakota at the time, they planned to move to Corvallis, Oregon in 1933, but they stopped in Nampa to visit friends, and never left.

The Chicken Inn operated through the 40s and into the 50s though the date of its demise is uncertain. Joe Tycz, who was a member of the Czech community, was also a farmer who raised peaches and spuds. He is remembered for the Chicken Inn, but also for providing the first permanent community Christmas tree to the City of Nampa. Citizens had been cutting trees and decorating them for the season for years. In 1954, Tycz donated a 20-foot-tall living blue spruce for the annual celebrations. It was planted in City Hall Park and became a focal point of community Christmas celebrations for several years.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.  The Fish Inn was located near Coeur d’Alene. It offered fish and other restaurant fare along with adult beverages and live entertainment. It was once voted one of the best road bars in America by Road and Track magazine. Library of Congress photo by John Margolies.

The Fish Inn was located near Coeur d’Alene. It offered fish and other restaurant fare along with adult beverages and live entertainment. It was once voted one of the best road bars in America by Road and Track magazine. Library of Congress photo by John Margolies.

Perhaps all the good café designs that resembled food were all taken when some restaurants started popping up with other odd shapes, an owl, a toad, a shoe, a chili bowl, an airplane, teepees, a flower pot, a sphinx, a piano, a blimp, a cream can, and a derby. That last one gives it away that this was a list just from California.

Idaho was not infested with restaurants that looked like food, nor was it immune. There were at least a couple. Many fondly remember the Chicken Inn, a drive in at 323 11th Avenue North. Offering Nampa’s first curb-side service, the Chicken Inn boasted “clear-finish woodwork and modernistic furnishings” inside with a stucco exterior. That exterior is what people remember. The roof was a chicken hunkered down as if sitting on a nest.

The giant chicken probably distinguished Nampa’s Chicken Inn from the other establishments named the Chicken Inn across the state. There was one in McCall, Jerome, Rupert, and Idaho Falls. Boise had a couple of them, at different times.

The advantage of having a restaurant shaped like a chicken was that you didn’t really have to go into detail about what was on the menu. If you wanted tofu, you went somewhere else.

Coeur d’Alene’s Fish Inn used the same strategy. When you walked into the mouth of that sucker (or trout, or whatever), you knew what you were there for. Built in 1932 it operated until the Fish, clearly out of water, burned in 1996.

Nampa’s Chicken Inn opened in February 1940. Joe and Mary Tycz built the place. Joe was born in Moravia in 1905 and moved to the US with his family when he was seven. He married Mary Salek in 1928. Living in South Dakota at the time, they planned to move to Corvallis, Oregon in 1933, but they stopped in Nampa to visit friends, and never left.

The Chicken Inn operated through the 40s and into the 50s though the date of its demise is uncertain. Joe Tycz, who was a member of the Czech community, was also a farmer who raised peaches and spuds. He is remembered for the Chicken Inn, but also for providing the first permanent community Christmas tree to the City of Nampa. Citizens had been cutting trees and decorating them for the season for years. In 1954, Tycz donated a 20-foot-tall living blue spruce for the annual celebrations. It was planted in City Hall Park and became a focal point of community Christmas celebrations for several years.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.  The Fish Inn was located near Coeur d’Alene. It offered fish and other restaurant fare along with adult beverages and live entertainment. It was once voted one of the best road bars in America by Road and Track magazine. Library of Congress photo by John Margolies.

The Fish Inn was located near Coeur d’Alene. It offered fish and other restaurant fare along with adult beverages and live entertainment. It was once voted one of the best road bars in America by Road and Track magazine. Library of Congress photo by John Margolies.

Published on April 12, 2024 04:00

April 11, 2024

Author Carol Ryrie Brink

Some writers are born from adversity. One of Idaho’s celebrated authors knew three notes of tragedy early in her life.

Carol Ryrie Brink’s birth was attended by her grandfather, Dr. William Woodbury Watkins. When the baby girl emerged, she did so silently. Her grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins, who was also there, whispered, “Stillborn.” Dr. Watkins had none of that. He picked up the infant and began breathing into its mouth. After a few moments the baby began to squirm and cry. As Brink said in her autobiography, A Chain of Hands, “He gave me my life more surely than my parents did.”

Her first tragedy was when her father, Alex Ryrie, died from tuberculosis when she was five. When Brink was six years old, she would know her second heartbreak. On August 4, 1901, her grandfather turned 55. It would be his last birthday.

On that Sunday, Dr. Watkins was driving a phaeton on his way to his office in Moscow where he was to attend to a sick young girl. As he approached an intersection a man on horseback rode up in front of Watkin’s carriage. Recognizing the man as William Steffans a local farmer and fellow Mason, he stopped and greeted him. Watkins knew Steffans as a violent man, one whom he had previously confronted after Steffans had beaten his own mother.

Steffans was not headed to church that day. He had a to-do list with him of the worst possible kind. The name of Dr. Watkins was on it. Steffans promptly pulled his pistol and shot the doctor. Watkins’ horse startled and ran, stopping only when it arrived at the familiar office of the man now sprawled dead on the seat of his carriage.

Meanwhile, Steffans rode through the streets of Moscow looking for people on his list that he had grudges with. He wasn’t having any luck finding them, so he began shooting randomly at anyone he saw, wounding several. The police were soon in pursuit. Foretelling the plot device of countless future movies, they shot not the tire of a criminal’s car, but the leg of his horse.

Afoot now, Steffans ran across the fields to his house and holed up inside. The townspeople formed a posse, gathered guns, and began a siege of the house. Steffans returned fire and the battle went on for some two hours. The mother he had treated so badly called out from inside the house that her son was dead. Whether from his own hand or a posse bullet is unclear.

In addition to Dr. Watkins a deputy died from wounds inflicted by Steffans.

Dr. Watkins was an engaged man, active not only in Moscow, but statewide. He was the first president of the state’s medical association, a member of the Board of Regents at the University of Idaho, and the chair of the first Idaho State Republican convention, during which he turned down a nomination for governor.

Brink honored her grandfather when she wrote a novel called Buffalo Coat in 1944. Based on his life, the book was on the New York Times bestseller list for weeks.

The final early tragedy in Brink’s life was the suicide of her mother when Carol was nine following a disastrous marriage. After that the young girl went to live with her widowed grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins. It was her grandmother’s story, fictionalized in the book Caddie Woodlawn that won Brink the 1936 Newbery Medal for “distinguished contribution to American Literature for children.”

In all, Carol Ryrie Brink would write more than 30 books, including her acclaimed adult trilogy Buffalo Coat, Strangers in the Forest, and Snow on the River, the last of which won the National League of American Pen Women Fiction Award.

Carol Ryrie Brink passed away at age 85 in 1981.

Carol Ryrie Brink’s birth was attended by her grandfather, Dr. William Woodbury Watkins. When the baby girl emerged, she did so silently. Her grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins, who was also there, whispered, “Stillborn.” Dr. Watkins had none of that. He picked up the infant and began breathing into its mouth. After a few moments the baby began to squirm and cry. As Brink said in her autobiography, A Chain of Hands, “He gave me my life more surely than my parents did.”

Her first tragedy was when her father, Alex Ryrie, died from tuberculosis when she was five. When Brink was six years old, she would know her second heartbreak. On August 4, 1901, her grandfather turned 55. It would be his last birthday.

On that Sunday, Dr. Watkins was driving a phaeton on his way to his office in Moscow where he was to attend to a sick young girl. As he approached an intersection a man on horseback rode up in front of Watkin’s carriage. Recognizing the man as William Steffans a local farmer and fellow Mason, he stopped and greeted him. Watkins knew Steffans as a violent man, one whom he had previously confronted after Steffans had beaten his own mother.

Steffans was not headed to church that day. He had a to-do list with him of the worst possible kind. The name of Dr. Watkins was on it. Steffans promptly pulled his pistol and shot the doctor. Watkins’ horse startled and ran, stopping only when it arrived at the familiar office of the man now sprawled dead on the seat of his carriage.

Meanwhile, Steffans rode through the streets of Moscow looking for people on his list that he had grudges with. He wasn’t having any luck finding them, so he began shooting randomly at anyone he saw, wounding several. The police were soon in pursuit. Foretelling the plot device of countless future movies, they shot not the tire of a criminal’s car, but the leg of his horse.

Afoot now, Steffans ran across the fields to his house and holed up inside. The townspeople formed a posse, gathered guns, and began a siege of the house. Steffans returned fire and the battle went on for some two hours. The mother he had treated so badly called out from inside the house that her son was dead. Whether from his own hand or a posse bullet is unclear.

In addition to Dr. Watkins a deputy died from wounds inflicted by Steffans.

Dr. Watkins was an engaged man, active not only in Moscow, but statewide. He was the first president of the state’s medical association, a member of the Board of Regents at the University of Idaho, and the chair of the first Idaho State Republican convention, during which he turned down a nomination for governor.

Brink honored her grandfather when she wrote a novel called Buffalo Coat in 1944. Based on his life, the book was on the New York Times bestseller list for weeks.

The final early tragedy in Brink’s life was the suicide of her mother when Carol was nine following a disastrous marriage. After that the young girl went to live with her widowed grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins. It was her grandmother’s story, fictionalized in the book Caddie Woodlawn that won Brink the 1936 Newbery Medal for “distinguished contribution to American Literature for children.”

In all, Carol Ryrie Brink would write more than 30 books, including her acclaimed adult trilogy Buffalo Coat, Strangers in the Forest, and Snow on the River, the last of which won the National League of American Pen Women Fiction Award.

Carol Ryrie Brink passed away at age 85 in 1981.

Published on April 11, 2024 04:00