Rick Just's Blog, page 25

April 30, 2024

When the Stars (sort of) Came to Boise

February 20, 1940 was a much-anticipated date in Boise. That evening would be the world premiere of a major motion picture at the Pinney Theater.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whoever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whoever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

Published on April 30, 2024 04:00

April 29, 2024

Murder and the Mayor

You might want to refill your coffee cup before reading today’s story. My posts are usually fairly short. This one just kept growing and growing as I learned more about the mayor and the murder.

Duncan McDougal Johnston was a WWI veteran who served in France with Battery B, 146th field artillery unit. He moved to Twin Falls from Boise in 1928 to open a jewelry store. By 1936 he was the Mayor of Twin Falls. That was the year he was briefly a candidate for congress in Idaho’s second congressional district, running against incumbent Congressman D. Worth Clark in the Democratic primary. In April 1938 he was the toastmaster at the Jefferson Day banquet in Twin Falls, lauding Congressman Clark. By December of 1938, at age 39, he was the former mayor of Twin Falls and he had been convicted of murder.

Johnston was convicted of killing a jewelry salesman by the name of George L. Olson of Salt Lake. Olson was found locked in his car at a Twin Falls hotel some days after being shot in the head. About $18,000 worth of Olson’s jewelry along with a .25-caliber gun believed to have been the murder weapon were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store.

In one of many novel-worthy twists, the judge for Johnston’s trial, James W. Porter, had been the man’s commanding officer during the war.

Early in the investigation there was some question about Salt Lake City police officers getting involved with the case. Salt Lake City Police Bureau Sergeant Albert H. Roberts put that to rest when he said that Twin Falls Police Chief Howard Gillette “(knew) his onions” when it came to interviewing suspects. And, yes, I gratuitously included that otherwise unimportant quote simply because it sounded like something out of a Mickey Spillane novel.

It wasn’t the only pulp fiction moment. One headline in The Times News read, “Slain Man With Beautiful Boise Girl, Proprietors and Chef Assert.” The proprietors were Mr. and Mrs. Howard McKray, owners of the tourist park where Olson had stayed, and the chef worked at a nearby restaurant. They were witnesses who saw the beautiful girl.

“I know it was him because that was the name he used. He was registered with us from Salt Lake City, was a jewelry salesman, and the picture in the papers was an exact likeness of him,” Mrs. McKray told reporters. Breathlessly, perhaps.

“Olson ran up a bill of $16,” the chef said, “and finally he traded me a wedding ring and engagement ring which I am going to give to my girl, Flossie Colson, who is working for me, when I marry her.” No word on how Flossie felt about getting a $16 wedding set swapped for corned beef hash.

During the trial one witness was described—Spillane style—as “a pretty, bespectacled telephone operator.” The newspaper reporter noted that she gave one of her answers “with a toss of her head.”

Meanwhile, the victim’s wife was a “pretty, youthful widow” and another witness was described as “comely.”

Patrolman Craig T. Bracken was a key witness in the case. His role was to hide in the basement of the jewelry store and spy on Johnston. The basement was accessible not only from the jewelry store but from an adjacent dress shop. He watched the man come down the stairs, toss something in the furnace, then turn and stare at a break or crack in the basement wall for a few seconds. Johnston left, but came back down the stairs a few minutes later, again paying some attention to the hole in the wall. That’s when the jeweler noticed the patrolman hiding behind the furnace. Bracken called out to Johnston, saying “Well, Dunc, they put me down here to watch you and see what you were doing.” Bracken arrested Johnston and took him to the station. Chief Gillette and another patrolmen went to the store and into the basement where they found 557 rings tied up in a towel, keys to the murdered man’s car, and a .25-caliber pistol.

Johnston and his assistant in the Jewelry store, William LaVonde, were arrested on suspicion of murder. LaVonde was more than an assistant to Johnston. They had served in the war together and were long time buddies. LaVonde was also a former desk sergeant with the Twin Falls police.

The men, both well-known in the community, were arrested June 2. On June 6, while in jail, Johnston completed the sale of his jewelry store to Don Kugler, of Idaho Falls. Had Johnston’s business been in trouble? Was that a motive for murder and robbery?

There was no provision for posting bail in Idaho at the time when one was accused of first-degree murder. LaVonde, the assistant in the jewelry store, asked for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds there was no compelling evidence against him. On September 16, the Idaho Supreme Court granted his petition and LaVonde went free. But not for long. A revised complaint got him tossed back in jail on the 20th. But not for long. A judge freed him on the 26th citing a lack of evidence against LaVonde in the case, but at the same time binding over Johnston for trial.

Even in an agricultural community it was a little odd that twelve men—11 of them farmers and the 12th a retired farmer—would pass judgement on Johnston. They were particularly qualified to understand when one of the prosecution witnesses explained why pieces of earth found in the victim’s car had not been analyzed. “There’s a lot of dirt in Twin Falls County,” the witness said.

The prosecution was built largely on the fact that the stolen jewels, the victim’s car keys, and an alleged murder weapon—the FBI could not say whether or not it had been the one used—were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store. Meanwhile, the defense pointed out that furnace service men, the dress shop owners, employees of a Chinese restaurant, and a rooming house operator all had keys to the same basement.

The defense opted not to make a final statement in the trial, perhaps assuming that a case built on circumstantial evidence didn’t need a summation to point that out. Or, maybe it did. The jury came back after eight hours of deliberation with a guilty verdict. Johnston was sentenced to life in prison.

On December 15, 1938, Duncan Johnston greeted an old friend by saying, “Hello, Pearl,” and giving Pearl C. Meredith a smile. Meredith was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary.

In 1939, the Idaho Supreme Court ordered a retrial of Johnston, citing questionable testimony by the Twin Falls Chief of Police. Johnston spent much more time on the stand defending himself in this trial. It didn’t help. He was found guilty, again. Johnston appealed, again, to the Idaho Supreme Court.

Then the confession showed up. On March 19, 1941, Governor Chase Clark received a note using letters cut from The Salt Lake Tribune and pasted on the paper in the fashion of a ransom demand. The anonymous message sender claimed that Johnston was the victim of a “vicious frame-up.” Although a cut-up Salt Lake newspaper was used, the letter came from Klamath Falls, Oregon.

Though interesting, the note proved nothing. The supreme court denied Johnston a third trial.

So, in December of 1941, the convicted murderer petitioned the pardon board for clemency.

At his January 1942 hearing, Johnston stood up to give an impassioned speech as the pardon board was rising to leave. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “Three and one-half years ago, or a little more, I sat as you gentlemen here today. My word had never been doubted. My integrity was as high… as anyone.

“From the time I was arrested until the present day, I have been a dastardly liar. I have been a Capone. I have been the coldest blooded murderer in the State of Idaho. Dillinger is a sissy to the side of me…

“You gentlemen have no idea what it means to sit behind bars and listen to the clang of chains and keys, when you did not commit the crime that was framed against you. It is almost unbelievable that in the United States, where we criticize the Nazis and the Gestapo, that you can find it right here in your own community.”

His pardon was denied by a 2-1 vote of the board.

He was back, again, in April asking for a pardon. Again, the vote was 2-1 against.

Then, there was a new twist. On December 21, 1942, the front-page headline spread across eight columns in The Statesman read, “Duncan Johnston Escapes From Prison.”

Under the cover of “pea-soup” fog, Johnston ran through the freshly fallen snow to an awaiting car in the 1400 block of East Washington and made his escape. He had constructed a dummy to occupy his bed during his getaway. His breakout was made easier because he wasn’t living in the prison. Johnston was a trusty residing in a small house adjacent to the hot-water pumps that supplied water to Warm Springs Avenue homes.

At least, that was the sensational story on December 21. By the next day, the front-page story was not nearly so dramatic. The headline read, “Johnston Returns to Cell After Going Bye-Bye Third Time.” Wait. Third time? Yes, it turned out Johnston had walked away a couple of other times, visiting Public School Field and the Ada County Courthouse the previous two times. The warden had neglected to mention those incidents. Johnston wasn’t captured. He simply walked back to the prison after spending seven hours walking around trying to “relieve a feeling of despondency” over his prison term.

So, pardon was probably off the table, right? Stand by.

His appeal for pardon that December, which happened to be decided the day after he walked away—and back—was denied.

His fourth application for pardon came in April 1943. It was denied.

In July 1943, the board denied his fifth application. His six application was denied that October.

On his seventh application, the board vote flipped in Johnston’s favor when Attorney General Bert H. Miller changed his vote. Why? He had determined through exhaustive investigation that several jurors as well as the prosecutors, were not convinced that Johnston had fired the fatal shot. Miller thought there was no proof he had fired the shot, and therefore Johnston had not been proved guilty. Miller was quoted in The Times News as saying, “I am not voting to pardon Johnston, but to release him from punishment for a crime for which he was unjustly convicted.”

Mr. and Mrs. C.D. Merrill, of Ketchum, had taken on Johnston’s case almost as a hobby, continuing to pester the pardon board time after time. They truly believed in his innocence and didn’t have a personal dog in the fight. They didn’t even know Johnston before he was imprisoned.

Johnston was grateful to the Merrills, but remained bitter, saying he wanted a reversal of his murder conviction in court instead of a pardon. “Naturally, I am terribly thankful for my freedom,” he said, “And it is hard to say thanks for something you don’t want—that is, I am glad to be free, but I didn’t want it to come this way.”

Johnston planned to go into defense work for the military, perhaps in California. “I went through five campaigns in the last war and came out a disabled veteran. Nothing would please me more than to do something in this campaign.”

Whether Johnston ever served in any capacity in WWII is unknown. He apparently left Idaho shortly after his pardon. His grandniece contacted me after this story ran the first time to say that he had operated a successful jewelry store in the Mission District of San Francisco for many years. He lived to be 90, passing away in San Mateo California in 1989.

The Olson murder case was never reopened.

But what of Attorney General Bert H. Miller? Many were outraged at his vote that set Johnston free. There were grumblings that his time as attorney general would soon be over. It was, but not in the way those who disagreed with him on the Johnston case might have hoped. He was elected a justice of Idaho’s Supreme Court in 1944, then elected a U.S. senator from Idaho in 1948, defeating Senator Henry Dworshak. Miller served only nine months in that office before dying of a heart attack. In a twist that probably ruffled a few feathers, Governor C.A. Robbins appointed Dworshak, the man Miller narrowly defeated, to fill out his term. Dworshak would remain a senator until 1962, when he, too, died of a heart attack while in office. Duncan McDougal Johnston

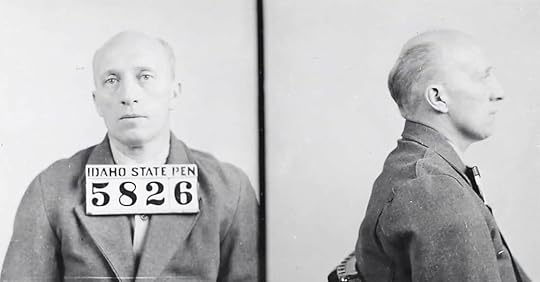

Duncan McDougal Johnston

Duncan McDougal Johnston was a WWI veteran who served in France with Battery B, 146th field artillery unit. He moved to Twin Falls from Boise in 1928 to open a jewelry store. By 1936 he was the Mayor of Twin Falls. That was the year he was briefly a candidate for congress in Idaho’s second congressional district, running against incumbent Congressman D. Worth Clark in the Democratic primary. In April 1938 he was the toastmaster at the Jefferson Day banquet in Twin Falls, lauding Congressman Clark. By December of 1938, at age 39, he was the former mayor of Twin Falls and he had been convicted of murder.

Johnston was convicted of killing a jewelry salesman by the name of George L. Olson of Salt Lake. Olson was found locked in his car at a Twin Falls hotel some days after being shot in the head. About $18,000 worth of Olson’s jewelry along with a .25-caliber gun believed to have been the murder weapon were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store.

In one of many novel-worthy twists, the judge for Johnston’s trial, James W. Porter, had been the man’s commanding officer during the war.

Early in the investigation there was some question about Salt Lake City police officers getting involved with the case. Salt Lake City Police Bureau Sergeant Albert H. Roberts put that to rest when he said that Twin Falls Police Chief Howard Gillette “(knew) his onions” when it came to interviewing suspects. And, yes, I gratuitously included that otherwise unimportant quote simply because it sounded like something out of a Mickey Spillane novel.

It wasn’t the only pulp fiction moment. One headline in The Times News read, “Slain Man With Beautiful Boise Girl, Proprietors and Chef Assert.” The proprietors were Mr. and Mrs. Howard McKray, owners of the tourist park where Olson had stayed, and the chef worked at a nearby restaurant. They were witnesses who saw the beautiful girl.

“I know it was him because that was the name he used. He was registered with us from Salt Lake City, was a jewelry salesman, and the picture in the papers was an exact likeness of him,” Mrs. McKray told reporters. Breathlessly, perhaps.

“Olson ran up a bill of $16,” the chef said, “and finally he traded me a wedding ring and engagement ring which I am going to give to my girl, Flossie Colson, who is working for me, when I marry her.” No word on how Flossie felt about getting a $16 wedding set swapped for corned beef hash.

During the trial one witness was described—Spillane style—as “a pretty, bespectacled telephone operator.” The newspaper reporter noted that she gave one of her answers “with a toss of her head.”

Meanwhile, the victim’s wife was a “pretty, youthful widow” and another witness was described as “comely.”

Patrolman Craig T. Bracken was a key witness in the case. His role was to hide in the basement of the jewelry store and spy on Johnston. The basement was accessible not only from the jewelry store but from an adjacent dress shop. He watched the man come down the stairs, toss something in the furnace, then turn and stare at a break or crack in the basement wall for a few seconds. Johnston left, but came back down the stairs a few minutes later, again paying some attention to the hole in the wall. That’s when the jeweler noticed the patrolman hiding behind the furnace. Bracken called out to Johnston, saying “Well, Dunc, they put me down here to watch you and see what you were doing.” Bracken arrested Johnston and took him to the station. Chief Gillette and another patrolmen went to the store and into the basement where they found 557 rings tied up in a towel, keys to the murdered man’s car, and a .25-caliber pistol.

Johnston and his assistant in the Jewelry store, William LaVonde, were arrested on suspicion of murder. LaVonde was more than an assistant to Johnston. They had served in the war together and were long time buddies. LaVonde was also a former desk sergeant with the Twin Falls police.

The men, both well-known in the community, were arrested June 2. On June 6, while in jail, Johnston completed the sale of his jewelry store to Don Kugler, of Idaho Falls. Had Johnston’s business been in trouble? Was that a motive for murder and robbery?

There was no provision for posting bail in Idaho at the time when one was accused of first-degree murder. LaVonde, the assistant in the jewelry store, asked for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds there was no compelling evidence against him. On September 16, the Idaho Supreme Court granted his petition and LaVonde went free. But not for long. A revised complaint got him tossed back in jail on the 20th. But not for long. A judge freed him on the 26th citing a lack of evidence against LaVonde in the case, but at the same time binding over Johnston for trial.

Even in an agricultural community it was a little odd that twelve men—11 of them farmers and the 12th a retired farmer—would pass judgement on Johnston. They were particularly qualified to understand when one of the prosecution witnesses explained why pieces of earth found in the victim’s car had not been analyzed. “There’s a lot of dirt in Twin Falls County,” the witness said.

The prosecution was built largely on the fact that the stolen jewels, the victim’s car keys, and an alleged murder weapon—the FBI could not say whether or not it had been the one used—were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store. Meanwhile, the defense pointed out that furnace service men, the dress shop owners, employees of a Chinese restaurant, and a rooming house operator all had keys to the same basement.

The defense opted not to make a final statement in the trial, perhaps assuming that a case built on circumstantial evidence didn’t need a summation to point that out. Or, maybe it did. The jury came back after eight hours of deliberation with a guilty verdict. Johnston was sentenced to life in prison.

On December 15, 1938, Duncan Johnston greeted an old friend by saying, “Hello, Pearl,” and giving Pearl C. Meredith a smile. Meredith was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary.

In 1939, the Idaho Supreme Court ordered a retrial of Johnston, citing questionable testimony by the Twin Falls Chief of Police. Johnston spent much more time on the stand defending himself in this trial. It didn’t help. He was found guilty, again. Johnston appealed, again, to the Idaho Supreme Court.

Then the confession showed up. On March 19, 1941, Governor Chase Clark received a note using letters cut from The Salt Lake Tribune and pasted on the paper in the fashion of a ransom demand. The anonymous message sender claimed that Johnston was the victim of a “vicious frame-up.” Although a cut-up Salt Lake newspaper was used, the letter came from Klamath Falls, Oregon.

Though interesting, the note proved nothing. The supreme court denied Johnston a third trial.

So, in December of 1941, the convicted murderer petitioned the pardon board for clemency.

At his January 1942 hearing, Johnston stood up to give an impassioned speech as the pardon board was rising to leave. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “Three and one-half years ago, or a little more, I sat as you gentlemen here today. My word had never been doubted. My integrity was as high… as anyone.

“From the time I was arrested until the present day, I have been a dastardly liar. I have been a Capone. I have been the coldest blooded murderer in the State of Idaho. Dillinger is a sissy to the side of me…

“You gentlemen have no idea what it means to sit behind bars and listen to the clang of chains and keys, when you did not commit the crime that was framed against you. It is almost unbelievable that in the United States, where we criticize the Nazis and the Gestapo, that you can find it right here in your own community.”

His pardon was denied by a 2-1 vote of the board.

He was back, again, in April asking for a pardon. Again, the vote was 2-1 against.

Then, there was a new twist. On December 21, 1942, the front-page headline spread across eight columns in The Statesman read, “Duncan Johnston Escapes From Prison.”

Under the cover of “pea-soup” fog, Johnston ran through the freshly fallen snow to an awaiting car in the 1400 block of East Washington and made his escape. He had constructed a dummy to occupy his bed during his getaway. His breakout was made easier because he wasn’t living in the prison. Johnston was a trusty residing in a small house adjacent to the hot-water pumps that supplied water to Warm Springs Avenue homes.

At least, that was the sensational story on December 21. By the next day, the front-page story was not nearly so dramatic. The headline read, “Johnston Returns to Cell After Going Bye-Bye Third Time.” Wait. Third time? Yes, it turned out Johnston had walked away a couple of other times, visiting Public School Field and the Ada County Courthouse the previous two times. The warden had neglected to mention those incidents. Johnston wasn’t captured. He simply walked back to the prison after spending seven hours walking around trying to “relieve a feeling of despondency” over his prison term.

So, pardon was probably off the table, right? Stand by.

His appeal for pardon that December, which happened to be decided the day after he walked away—and back—was denied.

His fourth application for pardon came in April 1943. It was denied.

In July 1943, the board denied his fifth application. His six application was denied that October.

On his seventh application, the board vote flipped in Johnston’s favor when Attorney General Bert H. Miller changed his vote. Why? He had determined through exhaustive investigation that several jurors as well as the prosecutors, were not convinced that Johnston had fired the fatal shot. Miller thought there was no proof he had fired the shot, and therefore Johnston had not been proved guilty. Miller was quoted in The Times News as saying, “I am not voting to pardon Johnston, but to release him from punishment for a crime for which he was unjustly convicted.”

Mr. and Mrs. C.D. Merrill, of Ketchum, had taken on Johnston’s case almost as a hobby, continuing to pester the pardon board time after time. They truly believed in his innocence and didn’t have a personal dog in the fight. They didn’t even know Johnston before he was imprisoned.

Johnston was grateful to the Merrills, but remained bitter, saying he wanted a reversal of his murder conviction in court instead of a pardon. “Naturally, I am terribly thankful for my freedom,” he said, “And it is hard to say thanks for something you don’t want—that is, I am glad to be free, but I didn’t want it to come this way.”

Johnston planned to go into defense work for the military, perhaps in California. “I went through five campaigns in the last war and came out a disabled veteran. Nothing would please me more than to do something in this campaign.”

Whether Johnston ever served in any capacity in WWII is unknown. He apparently left Idaho shortly after his pardon. His grandniece contacted me after this story ran the first time to say that he had operated a successful jewelry store in the Mission District of San Francisco for many years. He lived to be 90, passing away in San Mateo California in 1989.

The Olson murder case was never reopened.

But what of Attorney General Bert H. Miller? Many were outraged at his vote that set Johnston free. There were grumblings that his time as attorney general would soon be over. It was, but not in the way those who disagreed with him on the Johnston case might have hoped. He was elected a justice of Idaho’s Supreme Court in 1944, then elected a U.S. senator from Idaho in 1948, defeating Senator Henry Dworshak. Miller served only nine months in that office before dying of a heart attack. In a twist that probably ruffled a few feathers, Governor C.A. Robbins appointed Dworshak, the man Miller narrowly defeated, to fill out his term. Dworshak would remain a senator until 1962, when he, too, died of a heart attack while in office.

Duncan McDougal Johnston

Duncan McDougal Johnston

Published on April 29, 2024 04:00

April 28, 2024

Lulu Bell Parr

The myth of the Wild West became so ingrained in the story of our country that it sold well even in the West itself. Dime novels were popular everywhere and while cowboys were still plentiful on the range—they’re still not rare—wild west shows played to packed arenas.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show made at least one stop in Idaho Falls in the early part of the Twentieth Century. A competing spectacle, the “101 Ranch Show” played in Boise on June 17, 1912, a time when wagons were still more common than automobiles on the streets.

The 101 Ranch was a real place, an 87,000-acre spread in northeastern Oklahoma that was the largest diversified farm and ranch at the time, boasting, according to a 1905 Idaho Statesman article, 9,000 acres of wheat, 3,000 acres of corn, and 10,000 head of longhorn cattle. The wild west show was just one of their many enterprises.

During its 1912 visit to Boise the paper carried stories about the “Dare Devil Girls” of the 101 Ranch. The best-known cowgirl appearing was Lulu Bell Parr, who had also appeared in the Buffalo Bill’s shows. Lulu was your typical cowgirl, having grown up in Indiana, moving to Ohio when she got married in 1896. She was divorced in 1902 and by 1903 she was travelling in Europe with Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show.

The Statesman reported that she was one of the most “fearless riders and skillful manipulators of the lariat, [and was] to the manor born, for much of her life has been spent on a ranch, and the ranch life appeals to her as the only one that is really worthwhile.” One could be forgiven for wondering why she was performing in a string of wild west shows if green acres was the only place to be.

Still, she was a superb rider. “Many times,” the article said, “both on the cattle range and in the exhibitions of the 101 Ranch, Miss Parr has courted injury and possible death by her daredevil riding.” The preceding spring, in that well-known Cowtown, Philadelphia, she dared to ride “an outlaw pony that had defied nearly all the cowboys and other rough riders. She made the attempt and would have achieved an immediate victory over the vicious animal if her saddle girth had not slipped and thrown her to the ground. Notwithstanding the fact that she was momentarily stunned and received numerous painful bruises, the plucky little rider attempted the feat again the next day and triumphed over the animal.”

The wild west shows dwindled in popularity. By 1929 they were about dead. Lulu Bell Parr retired, broke and discouraged. She settled in Ohio where she lived with her brother until her death in 1960 at age 84.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show made at least one stop in Idaho Falls in the early part of the Twentieth Century. A competing spectacle, the “101 Ranch Show” played in Boise on June 17, 1912, a time when wagons were still more common than automobiles on the streets.

The 101 Ranch was a real place, an 87,000-acre spread in northeastern Oklahoma that was the largest diversified farm and ranch at the time, boasting, according to a 1905 Idaho Statesman article, 9,000 acres of wheat, 3,000 acres of corn, and 10,000 head of longhorn cattle. The wild west show was just one of their many enterprises.

During its 1912 visit to Boise the paper carried stories about the “Dare Devil Girls” of the 101 Ranch. The best-known cowgirl appearing was Lulu Bell Parr, who had also appeared in the Buffalo Bill’s shows. Lulu was your typical cowgirl, having grown up in Indiana, moving to Ohio when she got married in 1896. She was divorced in 1902 and by 1903 she was travelling in Europe with Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show.

The Statesman reported that she was one of the most “fearless riders and skillful manipulators of the lariat, [and was] to the manor born, for much of her life has been spent on a ranch, and the ranch life appeals to her as the only one that is really worthwhile.” One could be forgiven for wondering why she was performing in a string of wild west shows if green acres was the only place to be.

Still, she was a superb rider. “Many times,” the article said, “both on the cattle range and in the exhibitions of the 101 Ranch, Miss Parr has courted injury and possible death by her daredevil riding.” The preceding spring, in that well-known Cowtown, Philadelphia, she dared to ride “an outlaw pony that had defied nearly all the cowboys and other rough riders. She made the attempt and would have achieved an immediate victory over the vicious animal if her saddle girth had not slipped and thrown her to the ground. Notwithstanding the fact that she was momentarily stunned and received numerous painful bruises, the plucky little rider attempted the feat again the next day and triumphed over the animal.”

The wild west shows dwindled in popularity. By 1929 they were about dead. Lulu Bell Parr retired, broke and discouraged. She settled in Ohio where she lived with her brother until her death in 1960 at age 84.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Published on April 28, 2024 04:00

April 27, 2024

Louise Shadduck

Louise Shadduck wore a lot of hats, figuratively, and not rarely her favorite cowboy hat. She wrote the book

Rodeo Idaho

! She also wrote

Andy Little, Idaho Sheep King

,

Doctors With Buggies, Snowshoes, and Planes

,

The House that Victor Built

and

At the Edge of the Ice

.* Mike Bullard wrote a book about her called

Lioness of Idaho

.*

Shadduck, born in Coeur d’Alene in 1915, started out as a journalist. She wrote first for The Spokesman Review, then her hometown paper, The Coeur d’Alene Press. It was while working for The Press that she got her first taste of politics, covering the Republican National Convention in 1944. Inspired, she founded the Kootenai County Young Republicans. Then, she served a dual role working as a journalist while serving as an intern in Senator Henry Dworshak’s Washington, DC office.

In 1946 Shadduck took a job with Idaho Governor Charles Robbins, serving first as a publicity assistant, then as his administrative assistant. She was the first female to serve as a governor’s administrative assistant in Idaho. It wouldn’t be her last first. During her stint in the governor’s office she wrote a freelance column for The Coeur d’Alene Press called “This and That.”

When Len B. Jordan followed Robbins as governor, he retained Shadduck in her administrative assistant position. Then, in 1952, Senator Dworshak talked her into moving back to DC. There she became friends with Dwight Eisenhower. She spoke at the Republican National Convention in a televised address in 1952 in support of Eisenhower.

Shadduck decided to dive into politics herself, running for Idaho’s First Congressional District seat against Democrat Gracie Pfost. She lost that race, but it was another first for her. The match was the first time two women ran against each other for a congressional seat in US history. She spoke again for Eisenhower at the 1956 Republican National Convention, but her political future was to be on the state level.

Governor Robert E. Smylie appointed Shadduck to head the Idaho Department of Commerce and Development in 1958, making her the first woman in the country to serve in a state cabinet position. She was instrumental in bringing the National Girl Scout Roundup and the World Boy Scout Jamboree to Farragut State Park in 1965 and 1967, respectively.

Following Smylie’s last term in office she went to work as an administrative assistant to Congressman Orval Hansen.

Shadduck was troubled by the rise of white supremacists in her home state. She lobbied for a change in the malicious harassment law. That law was critical in putting the Aryan Nations out of business.

In her spare time, Shadduck served as president of the National Federation of Press Women from 1971 to 1973.

Shadduck never married. Upon her death in 2008, her great niece was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “it was because no man could keep up with her.”

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 World Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 World Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Shadduck, born in Coeur d’Alene in 1915, started out as a journalist. She wrote first for The Spokesman Review, then her hometown paper, The Coeur d’Alene Press. It was while working for The Press that she got her first taste of politics, covering the Republican National Convention in 1944. Inspired, she founded the Kootenai County Young Republicans. Then, she served a dual role working as a journalist while serving as an intern in Senator Henry Dworshak’s Washington, DC office.

In 1946 Shadduck took a job with Idaho Governor Charles Robbins, serving first as a publicity assistant, then as his administrative assistant. She was the first female to serve as a governor’s administrative assistant in Idaho. It wouldn’t be her last first. During her stint in the governor’s office she wrote a freelance column for The Coeur d’Alene Press called “This and That.”

When Len B. Jordan followed Robbins as governor, he retained Shadduck in her administrative assistant position. Then, in 1952, Senator Dworshak talked her into moving back to DC. There she became friends with Dwight Eisenhower. She spoke at the Republican National Convention in a televised address in 1952 in support of Eisenhower.

Shadduck decided to dive into politics herself, running for Idaho’s First Congressional District seat against Democrat Gracie Pfost. She lost that race, but it was another first for her. The match was the first time two women ran against each other for a congressional seat in US history. She spoke again for Eisenhower at the 1956 Republican National Convention, but her political future was to be on the state level.

Governor Robert E. Smylie appointed Shadduck to head the Idaho Department of Commerce and Development in 1958, making her the first woman in the country to serve in a state cabinet position. She was instrumental in bringing the National Girl Scout Roundup and the World Boy Scout Jamboree to Farragut State Park in 1965 and 1967, respectively.

Following Smylie’s last term in office she went to work as an administrative assistant to Congressman Orval Hansen.

Shadduck was troubled by the rise of white supremacists in her home state. She lobbied for a change in the malicious harassment law. That law was critical in putting the Aryan Nations out of business.

In her spare time, Shadduck served as president of the National Federation of Press Women from 1971 to 1973.

Shadduck never married. Upon her death in 2008, her great niece was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “it was because no man could keep up with her.”

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 World Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 World Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Published on April 27, 2024 04:00

April 26, 2024

Joe Bengoechea

Jose “Joe” Bengoechea was a Basque sheepherder. Maybe it should be said that he was the Basque sheepherder. He came to the US in 1881 at age 20. He started herding sheep in Nevada, saving his money, and began buying sheep. His herds grew and he helped others from the Basque Country to immigrate.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915. The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

Published on April 26, 2024 04:00

April 25, 2024

Hawthorne Gray

I found this one surprisingly hard to write. More about that in a moment.

Hawthorne C. Gray was a driven man. The Coeur d’Alene High School and University of Idaho graduate was the son of Captain W.P. Gray who piloted the steamer Georgie Oaks on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Hawthorne Gray joined the Idaho National Guard after graduating from U of I, and later the U.S. Army. Early on in his army career, in 1916, he fought in the Pancho Villa Expedition, serving as an infantry private. In 1917 he was commissioned a second lieutenant and in 1920 transferred to the U.S. Army Air Service as a captain. Shortly after that Gray caught the balloon bug.

He participated in some major balloon races, finishing second in the 1926 Gordon Bennett, the premiere race for gas balloonists. Then he set his sights on the altitude record for gas balloons. In 1927 he set an unofficial altitude record at 28,510 feet. He passed out during the attempt and awoke as the balloon was descending on its own just in time to throw off ballast and land safely.

In May that same year he went up again, smashing the altitude record for a human being by taking his balloon to 42,470 feet. But that record would remain unofficial. The balloon was dropping like a rock and he bailed out at 8,000 feet, parachuting to safety. Since he did not ride the bag down the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the organization that sanctioned such records, refused to recognize it.

So, back into the air. He made his third attempt in November 1927, rising ultimately to somewhere between 43,000 and 44,000 feet. Alas, once again he passed out. This time that proved fatal. Hawthorne Gray died in his final record attempt. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, posthumously.

That’s a sad story, but why would it be difficult for me to write? Because I had a friend and kayak partner who spent some years in the army, as did Gray. Carol was a flight surgeon. She was passionate about balloons, too, and once broke the altitude record for a woman in a gas balloon. She also won, along with ballooning partner Richard Abruzzo, the 2004 Gordon Bennett balloon race. They competed in that race twice more. In 2010 Carol Rymer Davis, driven in much the same way Hawthorne Gray was, went down with Richard Abruzzo over the Adriatic in a thunderstorm during the Gordon Bennett. They both died.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Hawthorne C. Gray was a driven man. The Coeur d’Alene High School and University of Idaho graduate was the son of Captain W.P. Gray who piloted the steamer Georgie Oaks on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Hawthorne Gray joined the Idaho National Guard after graduating from U of I, and later the U.S. Army. Early on in his army career, in 1916, he fought in the Pancho Villa Expedition, serving as an infantry private. In 1917 he was commissioned a second lieutenant and in 1920 transferred to the U.S. Army Air Service as a captain. Shortly after that Gray caught the balloon bug.

He participated in some major balloon races, finishing second in the 1926 Gordon Bennett, the premiere race for gas balloonists. Then he set his sights on the altitude record for gas balloons. In 1927 he set an unofficial altitude record at 28,510 feet. He passed out during the attempt and awoke as the balloon was descending on its own just in time to throw off ballast and land safely.

In May that same year he went up again, smashing the altitude record for a human being by taking his balloon to 42,470 feet. But that record would remain unofficial. The balloon was dropping like a rock and he bailed out at 8,000 feet, parachuting to safety. Since he did not ride the bag down the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the organization that sanctioned such records, refused to recognize it.

So, back into the air. He made his third attempt in November 1927, rising ultimately to somewhere between 43,000 and 44,000 feet. Alas, once again he passed out. This time that proved fatal. Hawthorne Gray died in his final record attempt. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, posthumously.

That’s a sad story, but why would it be difficult for me to write? Because I had a friend and kayak partner who spent some years in the army, as did Gray. Carol was a flight surgeon. She was passionate about balloons, too, and once broke the altitude record for a woman in a gas balloon. She also won, along with ballooning partner Richard Abruzzo, the 2004 Gordon Bennett balloon race. They competed in that race twice more. In 2010 Carol Rymer Davis, driven in much the same way Hawthorne Gray was, went down with Richard Abruzzo over the Adriatic in a thunderstorm during the Gordon Bennett. They both died.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Published on April 25, 2024 04:00

April 24, 2024

A Sheriff on the Lam

George H. Pease seemed like a solid guy. He was the six-foot-six sheriff of Kootenai County in 1898 and he had put together a group of 112 men who were ready to volunteer to fight in the Spanish-American War. Governor Steunenberg took Captain Pease up on his offer, but needed just 50 men, and no officers. So, the Sheriff stayed home. He wouldn’t stay for long.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

Published on April 24, 2024 04:00

April 23, 2024

The Freedom Riders

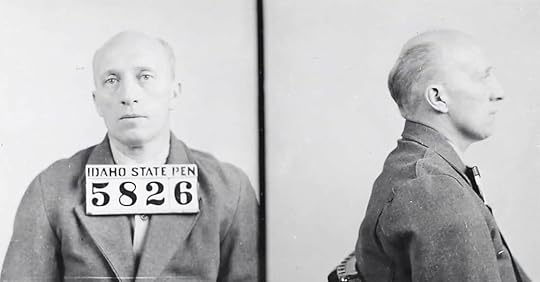

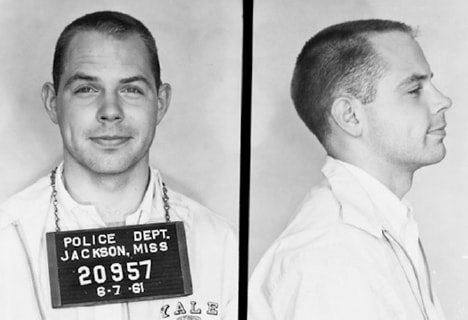

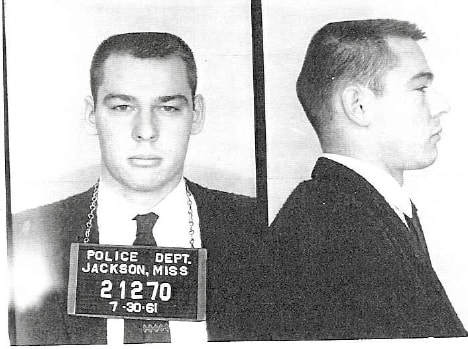

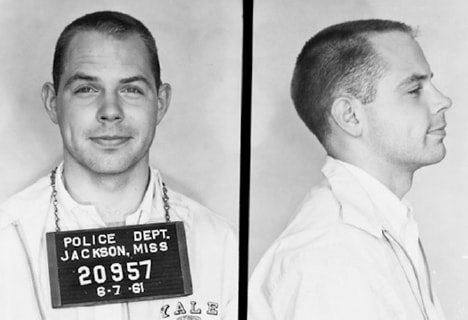

Some mugshots mean more than they would seem. Today we’re going to feature two men with strong Idaho ties who should be proud of their mugshots.

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

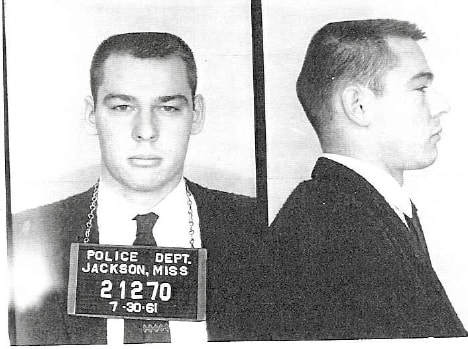

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement.

Edward Kale mugshot.

Edward Kale mugshot.  Max Pavesic mugshot.

Max Pavesic mugshot.

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement.

Edward Kale mugshot.

Edward Kale mugshot.  Max Pavesic mugshot.

Max Pavesic mugshot.

Published on April 23, 2024 04:00

April 22, 2024

Boise's First Buzz Wagon Wreck

The 1907 headline read “Buzz Wagon Parties Now a Fad.” The Idaho Statesman hadn’t yet settled on what to call automobiles. “Buzz wagon” didn’t catch on, fading as fast as the fad.

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Published on April 22, 2024 04:00

April 21, 2024

The Spalding Letter

My research methods, though sometimes systematic, are just as of ten serendipitous. I stumble onto something while looking for something else.

This chance method rewarded me recently when I found a transcript of Eliza Spalding’s first letter written to her family at home from her new residence on Lapwai Creek. It was reprinted in the 1922 Biennial Report of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The letter was dated February 16, 1837 and addressed to “Ever Dear Parents, Brothers and Sisters.”

The letter told of the profound eagerness of the Nez Perce for religious instruction: “Mr. S. resolved if possible not to disappoint the unspeakable desire the Nezperces had ever manifested to have us live with them that they might learn about God, and the habits of civilized life.”

Tribal members cut and carried pine logs on their shoulders for half a mile for the Spalding residence. Eliza wrote, “A number of them, one chief in particular, has been sawing at the pit saw for several weeks.”

It was surprising to me that the Nez Perce already had a rudimentary understanding of Christianity when the Spaldings arrived. They had learned of it from an Iroquois Indian who was in the employ of the American Fur Company.

The Spaldings saw in the Nez Perce a readiness to abandon their tribal beliefs and embrace the story of Jesus. Eliza wrote of the “conjurers or medicine men who pretend to heal the sick by their incantations.” She thought tribal members held them in low regard. Her evidence was that several Nez Perce came to her husband, the Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding, seeking a cure for various ailments. “They are very fond of being bled if they are sick, and Mr. S. has really succeeded in doing some of them the favor,” Mrs. Spalding wrote.

The efficacy of bloodletting was likely inferior to some of the native cures that had been passed down through the centuries.

Eliza went on to describe a Nez Perce vision quest in the most skeptical terms: “A youth who wishes this profession goes to the Mts., where he remains alone for 2 days, after which he returns to his friends pretending to be inspired with qualification requisite for healing diseases, that birds and wild beasts came to him while in the mountains and told him that those who employed him must reward him with blankets, horses and various good things. I hope and trust that the gospel will soon cause them to abandon these notions.”

Judge the Spaldings however you will, but I came away after reading the letter with a better appreciation for the sacrifice they had made by coming west. In many ways, they may as well have established their mission on Mars. Here’s what Eliza said about that to her family.

“We probably shall not meet again in this world, but if we fulfill the great end for which we were created, we shall be prepared to meet in one never to be separated. If you have received all the communications, we have directed to you, you have heard from us every few months since we left you. We probably shall write you once in six months. At all events we intend to write every opportunity, for this is the only favor we can show you in our remote situation.”

Mrs. Spalding was 30 years old when she wrote the letter. The births of her four children and the deaths of her friends and fellow missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in the Whitman Massacre were still ahead of her.

Eliza Hart Spalding died in Brownsville, Oregon in 1851 at age 43. She was originally buried there but was later disinterred and buried with her husband at the Lapwai Mission Cemetery in Idaho.