Rick Just's Blog, page 21

June 12, 2024

Idaho's Gas Tax Over the Years

Idaho’s state gasoline tax hasn’t really raised in a hundred and one years. I have your attention with that statement, don’t I?

In 1923, Idaho instituted its first tax on gasoline. The Legislature that year tacked two cents onto each gallon of gas for road building and repair. Gas cost about 22 cents a gallon. Automobile owners were generally supportive of the effort.

Today, Idaho’s state gasoline tax is 32 cents per gallon, so it has obviously gone up. But factor in inflation. That two cents from 1923 would have 37 cents of buying power today. So, the buying power of today’s gas tax is actually less than that original two-cent-tax.

The two-cent tax became a three-cent tax in 1925, a four-cent tax in 1927, and a nickel in 1929. The state was in a road-building frenzy. The tax remained the same until 1945 when it went to 6 cents. It hung around in that neighborhood for 23 years, going to seven cents in 1968. Four years later, the tax went to 8.5 cents a gallon. In 1976 it hit 9.5 cents. In 1981, the Legislature moved it to 11.5 cents. That was so much fun that they raised it an additional penny the next year. Giddy with that accomplishment, lawmakers moved it two cents in 1983 to 14.5 cents per gallon. It stayed there until 1988 when it jumped to 18 cents. In 1991 the tax moved 21 cents.

Are you seeing a pattern here?

The first time Idahoans started paying a quarter in tax for every gallon of gas was in 1996. That was more than a gallon of gas cost back in 1923 when the whole thing started. In 2015 the state gasoline tax went to 32 cents per gallon (effective in 2017), which is where it is today.

It was also in 2015 that the Legislature took notice of scoundrels like me who don’t pay any gasoline tax because we don’t buy any gasoline. They added $140 to annual registration fees for electric vehicles to help maintain roads.

Are roads better today than they were in 1923 when all this began? Considerably. They’re also a lot more expensive to build and maintain, so look for future gas tax increases or some other method to help pay for them from some future Legislature.

What other method? How about one that more fairly accounts for road use, such as a mileage fee on all cars, gas, electric, or hydrogen? That’s simple, but it doesn’t take into account vehicles' weight, which is an important factor when determining their impact on road wear.

It gets so complicated you may just decide to walk, instead.

Some pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Some pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

In 1923, Idaho instituted its first tax on gasoline. The Legislature that year tacked two cents onto each gallon of gas for road building and repair. Gas cost about 22 cents a gallon. Automobile owners were generally supportive of the effort.

Today, Idaho’s state gasoline tax is 32 cents per gallon, so it has obviously gone up. But factor in inflation. That two cents from 1923 would have 37 cents of buying power today. So, the buying power of today’s gas tax is actually less than that original two-cent-tax.

The two-cent tax became a three-cent tax in 1925, a four-cent tax in 1927, and a nickel in 1929. The state was in a road-building frenzy. The tax remained the same until 1945 when it went to 6 cents. It hung around in that neighborhood for 23 years, going to seven cents in 1968. Four years later, the tax went to 8.5 cents a gallon. In 1976 it hit 9.5 cents. In 1981, the Legislature moved it to 11.5 cents. That was so much fun that they raised it an additional penny the next year. Giddy with that accomplishment, lawmakers moved it two cents in 1983 to 14.5 cents per gallon. It stayed there until 1988 when it jumped to 18 cents. In 1991 the tax moved 21 cents.

Are you seeing a pattern here?

The first time Idahoans started paying a quarter in tax for every gallon of gas was in 1996. That was more than a gallon of gas cost back in 1923 when the whole thing started. In 2015 the state gasoline tax went to 32 cents per gallon (effective in 2017), which is where it is today.

It was also in 2015 that the Legislature took notice of scoundrels like me who don’t pay any gasoline tax because we don’t buy any gasoline. They added $140 to annual registration fees for electric vehicles to help maintain roads.

Are roads better today than they were in 1923 when all this began? Considerably. They’re also a lot more expensive to build and maintain, so look for future gas tax increases or some other method to help pay for them from some future Legislature.

What other method? How about one that more fairly accounts for road use, such as a mileage fee on all cars, gas, electric, or hydrogen? That’s simple, but it doesn’t take into account vehicles' weight, which is an important factor when determining their impact on road wear.

It gets so complicated you may just decide to walk, instead.

Some pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Some pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Published on June 12, 2024 04:00

June 11, 2024

Dad Clay and the Kidnappers

What are the odds of being a participant in two kidnappings? J.C. “Dad” Clay of Idaho Falls could claim that. He had different roles in each adventure, first as the driver of a carload of law enforcement officers that captured a kidnapper, and second as the kidnappee and captor of the kidnappers.

As I wrote yesterday, Clay owned the first automobile garage in the state. He started his Idaho Falls garage in 1909. By 1914, he was selling cars there and had published Idaho’s first road log to help travelers get around the state. His first brush with kidnapping came in 1915.

That’s when the kidnapper of E.A. Empey was apprehended. The Idaho Statesman, on July 28, 1915 described it like this: “A party was at once organized at the Sheriff’s office, consisting of deputies and reporters, who in a big car driven by J.C. Clay, an old resident of the community, thoroughly familiar with every road and trail in the entire country and a fast driver, were soon on the way to meet the bandit and his captors.” Clay played a small role in that incident, which you can read all about through the link above. His role was decidedly larger during the next kidnapping the following year.

According to an oral history told to his family, the kidnapping came about because he ran a taxi service next to his garage. A couple of tough looking young men came by looking for a ride into the country. An employee was set to take them, but Clay didn’t think it was safe for the boy to head out with those customers, so he decided to take them himself.

One of the men hopped into the seat beside the driver and the other got in back. They had driven about 20 miles when the man in the back seat slipped a piece of pipe out from under his coat where he had been hiding it and wacked Dad Clay over the head, knocking him out. The pair frisked Clay, finding a derringer in his side pocket and his wallet. They tied his hands and feet together and threw the unconscious man in the back.

After a few minutes and miles of travel, Clay came to. He could hear the toughs in front of the car laughing about hijacking his taxi. He came to understand that it was their plan to dump him in a ditch somewhere after killing him. Since this didn’t mesh well with his own plans for the future, Dad Clay worked his hands and feet free from the ropes while his kidnappers weren’t paying any attention. In the process, he discovered that the pipe he’d been beaned with was down there on the floor with him.

Clay rose up and returned the favor, clubbing each man hard on the head with the pipe. He tied both of them up, doing a better job of it than they had, and piled them in the back seat. He had found his derringer and couple of pistols the men had been carrying. His passengers secured, he turned around and headed back to town.

Dad Clay delivered the carjackers to the sheriff’s office, where he found out they’d escaped from a nearby correctional facility.

There is a newspaper account of the story which differs a bit. In that version one of the kidnappers escaped for a short time before being apprehended by authorities, but the essential account of Clay’s bonk on the head and turning the tables on the men to bring them to justice seems essentially true.

Portrait of J.C. “Dad” Clay.

Portrait of J.C. “Dad” Clay.

As I wrote yesterday, Clay owned the first automobile garage in the state. He started his Idaho Falls garage in 1909. By 1914, he was selling cars there and had published Idaho’s first road log to help travelers get around the state. His first brush with kidnapping came in 1915.

That’s when the kidnapper of E.A. Empey was apprehended. The Idaho Statesman, on July 28, 1915 described it like this: “A party was at once organized at the Sheriff’s office, consisting of deputies and reporters, who in a big car driven by J.C. Clay, an old resident of the community, thoroughly familiar with every road and trail in the entire country and a fast driver, were soon on the way to meet the bandit and his captors.” Clay played a small role in that incident, which you can read all about through the link above. His role was decidedly larger during the next kidnapping the following year.

According to an oral history told to his family, the kidnapping came about because he ran a taxi service next to his garage. A couple of tough looking young men came by looking for a ride into the country. An employee was set to take them, but Clay didn’t think it was safe for the boy to head out with those customers, so he decided to take them himself.

One of the men hopped into the seat beside the driver and the other got in back. They had driven about 20 miles when the man in the back seat slipped a piece of pipe out from under his coat where he had been hiding it and wacked Dad Clay over the head, knocking him out. The pair frisked Clay, finding a derringer in his side pocket and his wallet. They tied his hands and feet together and threw the unconscious man in the back.

After a few minutes and miles of travel, Clay came to. He could hear the toughs in front of the car laughing about hijacking his taxi. He came to understand that it was their plan to dump him in a ditch somewhere after killing him. Since this didn’t mesh well with his own plans for the future, Dad Clay worked his hands and feet free from the ropes while his kidnappers weren’t paying any attention. In the process, he discovered that the pipe he’d been beaned with was down there on the floor with him.

Clay rose up and returned the favor, clubbing each man hard on the head with the pipe. He tied both of them up, doing a better job of it than they had, and piled them in the back seat. He had found his derringer and couple of pistols the men had been carrying. His passengers secured, he turned around and headed back to town.

Dad Clay delivered the carjackers to the sheriff’s office, where he found out they’d escaped from a nearby correctional facility.

There is a newspaper account of the story which differs a bit. In that version one of the kidnappers escaped for a short time before being apprehended by authorities, but the essential account of Clay’s bonk on the head and turning the tables on the men to bring them to justice seems essentially true.

Portrait of J.C. “Dad” Clay.

Portrait of J.C. “Dad” Clay.

Published on June 11, 2024 04:00

June 10, 2024

"Dad" Clay Made His Mark

John Colby Clay was born in Minnesota in 1854. He came West when he was 15. He kicked around the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Oregon for a number of years punching cattle, ranching, and driving a freight wagon. He ended up settling in Idaho in 1892.

In 1908 (or 1909, or 1910… accounts differ) J.C. Clay had an epiphany. He was fascinated with automobiles and decided to bet his future on them. Already in his 50s, it wouldn’t seem like a time to start a new venture, but he did. No one knows exactly when people started calling him “Dad” Clay, but he solidified that moniker by building Dad Clay’s Garage. It was the first automobile service center in the state. It grew to include car dealerships for a time and a taxi company. Proving that he was a man way ahead of his time, he built an underground parking area beneath the garage.

Dad Clay was elected the “good roads” chairman of the Idaho State Automobile Association. He took that job seriously. He began marking roads, much as Charlie Sampson did in the Boise area. Sampson started out painting advertising signs about his music business. Clay erected hundreds of black and orange signs all over Southeastern Idaho giving the mileage to his Idaho Falls garage. In 1914, Dad Clay published the first guide to Idaho’s 5,500 miles of roads. It was a big hit with auto enthusiasts, though at least one resident of Pocatello accused him of discriminating against the Gate City by routing travelers around it.

Running Idaho’s first garage wasn’t enough to keep Dad Clay busy, though. He was involved in real estate development, a coal mine, Teton Light and Power, a security firm, and managed the Idaho Falls baseball team, the Sunnylanders. Clay was also a well-known golfer locally. He once famously bet his false teeth on the outcome of a match.

Dad Clay’s love for automobiles got him in trouble at least a couple of times. He was carjacked once, turning the tables on the bad guys. We'll tell that story tomorrow.

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”  Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

In 1908 (or 1909, or 1910… accounts differ) J.C. Clay had an epiphany. He was fascinated with automobiles and decided to bet his future on them. Already in his 50s, it wouldn’t seem like a time to start a new venture, but he did. No one knows exactly when people started calling him “Dad” Clay, but he solidified that moniker by building Dad Clay’s Garage. It was the first automobile service center in the state. It grew to include car dealerships for a time and a taxi company. Proving that he was a man way ahead of his time, he built an underground parking area beneath the garage.

Dad Clay was elected the “good roads” chairman of the Idaho State Automobile Association. He took that job seriously. He began marking roads, much as Charlie Sampson did in the Boise area. Sampson started out painting advertising signs about his music business. Clay erected hundreds of black and orange signs all over Southeastern Idaho giving the mileage to his Idaho Falls garage. In 1914, Dad Clay published the first guide to Idaho’s 5,500 miles of roads. It was a big hit with auto enthusiasts, though at least one resident of Pocatello accused him of discriminating against the Gate City by routing travelers around it.

Running Idaho’s first garage wasn’t enough to keep Dad Clay busy, though. He was involved in real estate development, a coal mine, Teton Light and Power, a security firm, and managed the Idaho Falls baseball team, the Sunnylanders. Clay was also a well-known golfer locally. He once famously bet his false teeth on the outcome of a match.

Dad Clay’s love for automobiles got him in trouble at least a couple of times. He was carjacked once, turning the tables on the bad guys. We'll tell that story tomorrow.

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”  Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

Published on June 10, 2024 04:00

June 9, 2024

Wherefore art thou, apostrophe?

Idaho became a state in 1890. Idahoans disagree on countless things, but there is probably near universal agreement about the name of the state. It’s important that we agree on the names of things. Imagine how confusing it would be if half the citizens of Arco called it by its original name, Root Hog. With apologies to The Lovin’ Spoonful, someone has to finally decide.

The standardization of names was why the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) was created, coincidentally the same year as the state of Idaho. Its charge is to “maintain uniform geographic names usage throughout the Federal Government.” The Board makes sure things are spelled consistently on maps and that two mountains in the same range don’t have the same name.

Driving English majors crazy is also, seemingly, part of the charge of the USBGN. This comes about because of the institution’s phobia about apostrophes. Since its inception, the USBGN has abhorred apostrophes, particularly discouraging the use of possessive apostrophes. That’s why Glenns Ferry is not Glenn’s Ferry and the Henrys Fork is not the Henry’s Fork.

There is nothing in the Board’s archives indicating why they discouraged the use of apostrophes. They do try to justify it in… words. Here you go: “The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists.”

You’re allowed to read that again, if you like.

The takeaway is that the USBGN is adamant that possessive apostrophes are not used in the many thousands of names scattered on United States maps. But, as with the old rule of grammar, “I after E, except after C,” there are a few exceptions. Five, to be exact.

Martha’s Vineyard and its otherwise offensive apostrophe was approved in 1933 after an extensive local campaign. Ike’s Point in New Jersey was approved in 1944 because “it would be unrecognizable otherwise.” In 1963, John E’s Pond got the nod of approval because it would be confused with John S Pond. Note the lack of a period in John S Pond. The USBGN doesn’t like periods, either. Carlos Elmer’s Joshua View was approved in 1995 at the request of the Arizona State Board on Geographic and Historic Names, because “otherwise three apparently given names in succession would dilute the meaning.” In this case Joshua refers to a stand of trees. Finally, Clark’s Mountain in Oregon got to keep its apostrophe in 2002 to “correspond with the personal references of Lewis and Clark.”

Alert readers will have already noted that there is an apostrophe used often in Idaho places names. That one is in the middle of Coeur d’Alene when it refers to the city, the lake, the valley, the tribal reservation, the mountain, the mountain range, and the river. It’s not a possessive apostrophe, so USBGN lets it live.

Postal officials also put the kibosh on certain names. For instance, there is only one city named Eagle in Idaho, though not for a lack of trying. The citizens of a little town south of Sandpoint wanted to call their home Eagle in 1900. To avoid confusion, the postal bureaucracy said no. The citizens in a spate of creativity just changed the E to an S on the post office application form and Sagle was born.

The standardization of names was why the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) was created, coincidentally the same year as the state of Idaho. Its charge is to “maintain uniform geographic names usage throughout the Federal Government.” The Board makes sure things are spelled consistently on maps and that two mountains in the same range don’t have the same name.

Driving English majors crazy is also, seemingly, part of the charge of the USBGN. This comes about because of the institution’s phobia about apostrophes. Since its inception, the USBGN has abhorred apostrophes, particularly discouraging the use of possessive apostrophes. That’s why Glenns Ferry is not Glenn’s Ferry and the Henrys Fork is not the Henry’s Fork.

There is nothing in the Board’s archives indicating why they discouraged the use of apostrophes. They do try to justify it in… words. Here you go: “The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists.”

You’re allowed to read that again, if you like.

The takeaway is that the USBGN is adamant that possessive apostrophes are not used in the many thousands of names scattered on United States maps. But, as with the old rule of grammar, “I after E, except after C,” there are a few exceptions. Five, to be exact.

Martha’s Vineyard and its otherwise offensive apostrophe was approved in 1933 after an extensive local campaign. Ike’s Point in New Jersey was approved in 1944 because “it would be unrecognizable otherwise.” In 1963, John E’s Pond got the nod of approval because it would be confused with John S Pond. Note the lack of a period in John S Pond. The USBGN doesn’t like periods, either. Carlos Elmer’s Joshua View was approved in 1995 at the request of the Arizona State Board on Geographic and Historic Names, because “otherwise three apparently given names in succession would dilute the meaning.” In this case Joshua refers to a stand of trees. Finally, Clark’s Mountain in Oregon got to keep its apostrophe in 2002 to “correspond with the personal references of Lewis and Clark.”

Alert readers will have already noted that there is an apostrophe used often in Idaho places names. That one is in the middle of Coeur d’Alene when it refers to the city, the lake, the valley, the tribal reservation, the mountain, the mountain range, and the river. It’s not a possessive apostrophe, so USBGN lets it live.

Postal officials also put the kibosh on certain names. For instance, there is only one city named Eagle in Idaho, though not for a lack of trying. The citizens of a little town south of Sandpoint wanted to call their home Eagle in 1900. To avoid confusion, the postal bureaucracy said no. The citizens in a spate of creativity just changed the E to an S on the post office application form and Sagle was born.

Published on June 09, 2024 04:00

June 7, 2024

The World's Tallest Dam

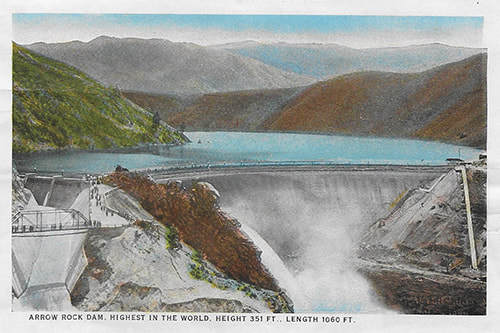

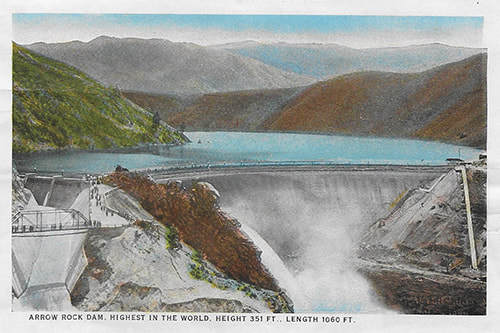

Arrowrock Dam may not seem like an engineering marvel, but it was the tallest dam in the world at one time. It didn’t hold that distinction for long. At 348, 350, or 351 feet—different writers used different rulers, apparently—it held that title from 1915 until 1932 when the Owyhee Dam in Oregon knocked it off its pedestal by about 50 feet.

The postcard below trumpeted the dam’s status by calling it the “highest dam.” I don’t know what dam would be the highest in the world, since “highest” refers to elevation. In Idaho the dam at the highest elevation would probably be Palisades Dam. Anyway, they meant tallest.

Arrowrock doesn’t even make the Wikipedia list of tall dams today. The tallest on that list is the Jinping Dam in China, at 1,001 feet.

The postcard below trumpeted the dam’s status by calling it the “highest dam.” I don’t know what dam would be the highest in the world, since “highest” refers to elevation. In Idaho the dam at the highest elevation would probably be Palisades Dam. Anyway, they meant tallest.

Arrowrock doesn’t even make the Wikipedia list of tall dams today. The tallest on that list is the Jinping Dam in China, at 1,001 feet.

Published on June 07, 2024 04:00

June 6, 2024

A Table Rock Hotel

You know Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary in Boise as the flat-topped mountain where the lighted cross stands overlooking the valley. You might also know it as a place where numerous rowdy parties have been held over the years. Do you remember that it is the home of Boise’s rock quarry? Do you recall that the big Boise “B” is located on the west end of the mesa?

Table Rock is all those things. If a plan put forth in 1907 had come to fruition, it would be something quite different.

In November of 1907, the Idaho Statesman ran the headline, “Hotel To Be Built On Table Rock.” J.S. Jellison had purchased his brother’s interest in the quarry on Table Rock, including 685 acres of property.

The hotel Jellison envisioned would be “a delightful summer resort.” Part of the ambitious plan was to run a set of trolley tracks up to the top of the mesa and in a loop around the rim of Table Rock. There was to be a branch line to the quarry to facilitate bringing rock into the valley.

And readers never heard another peep about it again. A trolley loop around the rim of Table Rock would be one more reason today to lament the loss of the Interurban. Perhaps.

An artistic conception (sort of) depicting a hotel on Table Rock.

An artistic conception (sort of) depicting a hotel on Table Rock.

Table Rock is all those things. If a plan put forth in 1907 had come to fruition, it would be something quite different.

In November of 1907, the Idaho Statesman ran the headline, “Hotel To Be Built On Table Rock.” J.S. Jellison had purchased his brother’s interest in the quarry on Table Rock, including 685 acres of property.

The hotel Jellison envisioned would be “a delightful summer resort.” Part of the ambitious plan was to run a set of trolley tracks up to the top of the mesa and in a loop around the rim of Table Rock. There was to be a branch line to the quarry to facilitate bringing rock into the valley.

And readers never heard another peep about it again. A trolley loop around the rim of Table Rock would be one more reason today to lament the loss of the Interurban. Perhaps.

An artistic conception (sort of) depicting a hotel on Table Rock.

An artistic conception (sort of) depicting a hotel on Table Rock.

Published on June 06, 2024 04:00

June 5, 2024

Blackfoot Streetview

The colorized photo of Main Street, Blackfoot on top below is probably from 1909 when the city was celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of the first Protestant service west of the Rocky Mountains being conducted in a grove near Fort Hall, and the first raising of the United States flag in the Pacific Northwest. I wrote about that in an earlier blog.

I noticed that the postcard photo doesn’t look a lot different from Main Street in Blackfoot today, so I grabbed a Google Streetview capture for comparison. It’s below the postcard.

If you follow with your finger straight down from where Main Street is printed on the postcard, you can just make out where Bridge Street intersects with it. Both buildings on either side of Bridge are still there today though the one on the far left has been much modified. Both have 45-degree corner entrances, though that’s difficult to make out in the contemporary photo.

Working back toward the right you can still make out the next two buildings, which are little changed. Then we see that the next three buildings in the 1909 photo have a metal facade tying them all together in the contemporary photo. Past the 1910 Groceries building we see a single gray building with a distinctive cornice running along the top. In the contemporary photo we see that part of the façade of that building has been modified to make it look like two distinct buildings.

The first photo was probably taken from near the train station, which is today the Idaho Potato Museum.

I noticed that the postcard photo doesn’t look a lot different from Main Street in Blackfoot today, so I grabbed a Google Streetview capture for comparison. It’s below the postcard.

If you follow with your finger straight down from where Main Street is printed on the postcard, you can just make out where Bridge Street intersects with it. Both buildings on either side of Bridge are still there today though the one on the far left has been much modified. Both have 45-degree corner entrances, though that’s difficult to make out in the contemporary photo.

Working back toward the right you can still make out the next two buildings, which are little changed. Then we see that the next three buildings in the 1909 photo have a metal facade tying them all together in the contemporary photo. Past the 1910 Groceries building we see a single gray building with a distinctive cornice running along the top. In the contemporary photo we see that part of the façade of that building has been modified to make it look like two distinct buildings.

The first photo was probably taken from near the train station, which is today the Idaho Potato Museum.

Published on June 05, 2024 04:00

June 4, 2024

Idaho's Prison Riots

In September 1971, the top story was all about a prison riot where 43 staff and inmates died. To this day, the word Attica is synonymous with prison riots. A month before that tragic event, an Idaho prison riot was in the news.

High temperatures in Boise had hovered around 100 degrees for ten days. On August 9 the thermometer hit 102. The cooldown to 98 degrees on August 10 was hardly noticeable, especially in the old cell blocks at the Idaho State Penitentiary on the outskirts of Boise. It could get up to 118 on the upper decks.

Cooler quarters for some of the inmates were closed that day because officials had found two escape tunnels in the “honor dormitory.” That detonated four hours of rioting. The prisoners set fires in the bakery and the social services building. Two inmates were stabbed in the melee.

After guards and Ada County deputies brought the incident under control, more complaints about conditions at the 99-year-old prison surfaced. A lack of sanitation was second only to the heat on the list of concerns for the inmates. Prisoners claimed to have found a dead rat in the dilapidated water tank on the hill above the prison, along with rat droppings. Inmates complained of filthy conditions in the kitchen and a lack of sanitation in the prison clinic.

Authorities brought in a dozen industrial fans and let inmates stay outside for a time after the riot and addressed some other prisoner complaints.

It was not the first riot at the prison, and it would not be the last. In 1952 300 prisoners rioted for five hours, setting fire to one of the dormitories. That dust-up was quelled when 100 heavily armed officers stood on the walls of the prison and fired teargas into the recreation building where inmates were gathered. Complaints about a new convict grievance committee set that disturbance off.

The last riot at the old prison was the one most remembered. It is also commonly misremembered as the reason Idaho built a new prison in the desert south of Boise. The new prison complex had been in the works for at least 13 years when the 1973 riot broke out. In fact, the riot started when an inmate who was already at the new maximum-security site was transported to the clinic at the old prison for treatment of a minor injury. When it was time to go back, inmate Larry Trujillo, 25, refused to go. Other inmates threateningly gathered around the guards attempting to move Trujillo.

While a discussion about moving the prisoner was taking place between the warden and the inmate council, fires broke out in four prison buildings. It was later learned that inmates accused guards of beating Trujillo and another inmate. That’s what sparked the riot of more than 200 prisoners.

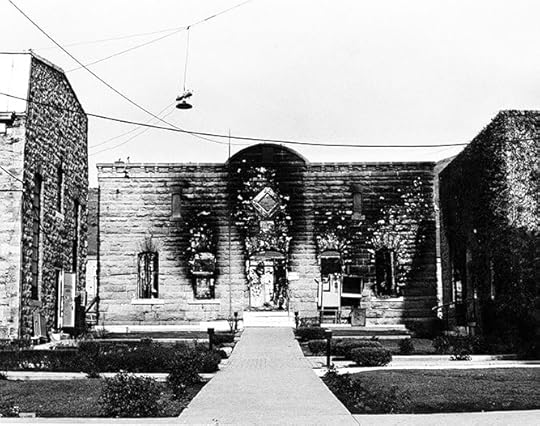

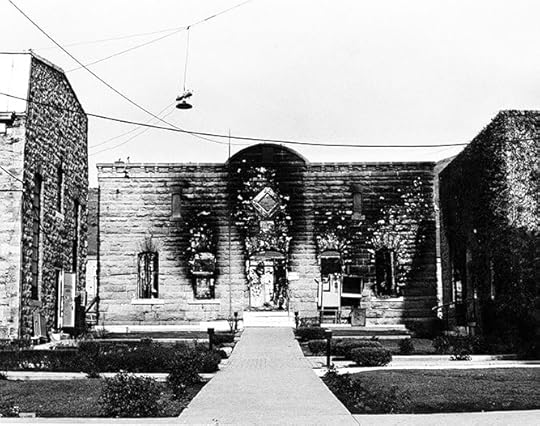

The fires destroyed the prison chapel and the kitchen-dining hall, with heavy damage to the tailor shop, laundry, and an administrative office. The flames left their signature on the Old Idaho Penitentiary as we know it today. Just three weeks after the riot, Idaho State Historical Society Director Arthur A. Hart had the foresight to implore authorities to leave the bones of the burned-out buildings in place to preserve the history of the riot and broached the subject of maintaining the old prison as an Idaho state historical site.

Although the 1973 riot was not the impetus for constructing the new $13 million dollar prison, it did give officials a push to move inmates as quickly as possible. The new prison opened December 3, 1973. The Idaho Statesman in a caption on a photo of shiny new bars, noted that “if anyone can get out of here, he doesn’t have many options on where to hide, because the new prison is in the middle of barren sagebrush land.”

The first escape came ten days later.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

High temperatures in Boise had hovered around 100 degrees for ten days. On August 9 the thermometer hit 102. The cooldown to 98 degrees on August 10 was hardly noticeable, especially in the old cell blocks at the Idaho State Penitentiary on the outskirts of Boise. It could get up to 118 on the upper decks.

Cooler quarters for some of the inmates were closed that day because officials had found two escape tunnels in the “honor dormitory.” That detonated four hours of rioting. The prisoners set fires in the bakery and the social services building. Two inmates were stabbed in the melee.

After guards and Ada County deputies brought the incident under control, more complaints about conditions at the 99-year-old prison surfaced. A lack of sanitation was second only to the heat on the list of concerns for the inmates. Prisoners claimed to have found a dead rat in the dilapidated water tank on the hill above the prison, along with rat droppings. Inmates complained of filthy conditions in the kitchen and a lack of sanitation in the prison clinic.

Authorities brought in a dozen industrial fans and let inmates stay outside for a time after the riot and addressed some other prisoner complaints.

It was not the first riot at the prison, and it would not be the last. In 1952 300 prisoners rioted for five hours, setting fire to one of the dormitories. That dust-up was quelled when 100 heavily armed officers stood on the walls of the prison and fired teargas into the recreation building where inmates were gathered. Complaints about a new convict grievance committee set that disturbance off.

The last riot at the old prison was the one most remembered. It is also commonly misremembered as the reason Idaho built a new prison in the desert south of Boise. The new prison complex had been in the works for at least 13 years when the 1973 riot broke out. In fact, the riot started when an inmate who was already at the new maximum-security site was transported to the clinic at the old prison for treatment of a minor injury. When it was time to go back, inmate Larry Trujillo, 25, refused to go. Other inmates threateningly gathered around the guards attempting to move Trujillo.

While a discussion about moving the prisoner was taking place between the warden and the inmate council, fires broke out in four prison buildings. It was later learned that inmates accused guards of beating Trujillo and another inmate. That’s what sparked the riot of more than 200 prisoners.

The fires destroyed the prison chapel and the kitchen-dining hall, with heavy damage to the tailor shop, laundry, and an administrative office. The flames left their signature on the Old Idaho Penitentiary as we know it today. Just three weeks after the riot, Idaho State Historical Society Director Arthur A. Hart had the foresight to implore authorities to leave the bones of the burned-out buildings in place to preserve the history of the riot and broached the subject of maintaining the old prison as an Idaho state historical site.

Although the 1973 riot was not the impetus for constructing the new $13 million dollar prison, it did give officials a push to move inmates as quickly as possible. The new prison opened December 3, 1973. The Idaho Statesman in a caption on a photo of shiny new bars, noted that “if anyone can get out of here, he doesn’t have many options on where to hide, because the new prison is in the middle of barren sagebrush land.”

The first escape came ten days later.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on June 04, 2024 04:00

June 3, 2024

Joseph Sherwood, Part Two

Yesterday I wrote a post about entrepreneur and Island Park pioneer Joseph Sherwood.

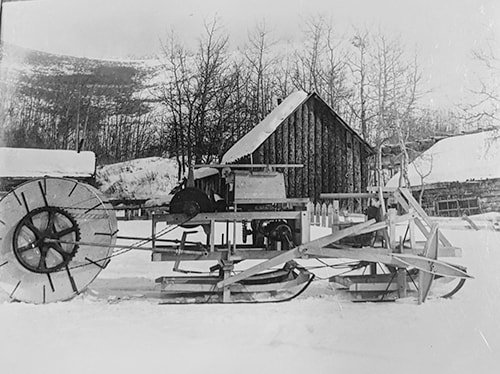

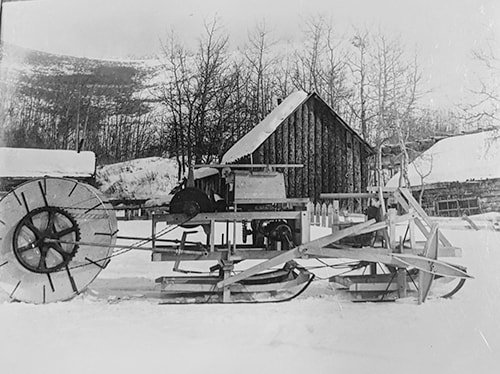

Sherwood built his own sawmill on the north shore of Henrys Lake using a canvas flume carrying water from ponds he had constructed for power. He was a mechanically minded man.

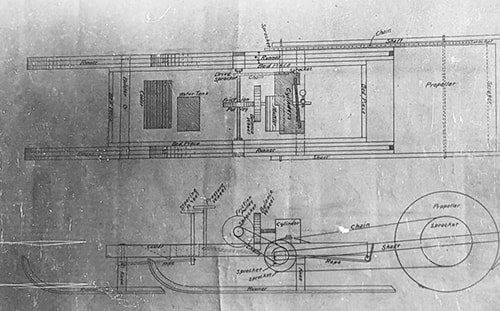

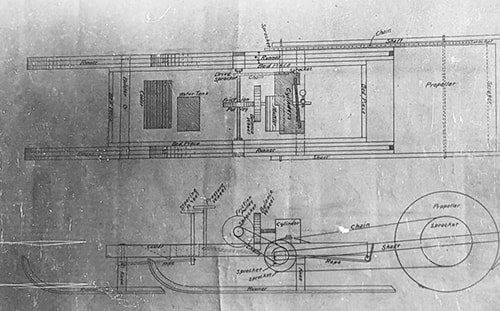

Did Sherwood have the first snowmobile in Idaho? I don’t know, but I’d like to hear if anyone knows of an earlier one. He received a patent, number 844,963 for his “auto snow-car.” He patterned it after a four runner, horse-drawn sled. A 1 ½ horsepower gasoline engine was connected gearbox and flywheel by a chain drive. Another set of chains wrapped around sprockets on a large wooden drum in the rear. That was the equivalent to the track on a modern snowmobile. To steer the contraption you moved the front runners from side to side by means of a lever.

The snow machine weighed something under 1,000 pounds. It wouldn’t win any races with a top speed of 12 miles per hour.

Sherwood didn’t apply for a patent on his car. He just built it. It was called “The Black Car.” He used magazine pictures as his construction guide.

The Sherwood store had been a stage stop for years. As motor vehicles began to appear in the Island Park area—his own was probably the first—Sherwood began selling gasoline and motor oil.

Joseph Sherwood died in 1919 due to complications from diabetes. The store he built continued in operation until the mid-1960s. The building has undergone extensive renovation and restoration. According to an article in the Rexburg Standard Journal, it may soon see another chapter in its history.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine.

The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.

The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.  “The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

“The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

Sherwood built his own sawmill on the north shore of Henrys Lake using a canvas flume carrying water from ponds he had constructed for power. He was a mechanically minded man.

Did Sherwood have the first snowmobile in Idaho? I don’t know, but I’d like to hear if anyone knows of an earlier one. He received a patent, number 844,963 for his “auto snow-car.” He patterned it after a four runner, horse-drawn sled. A 1 ½ horsepower gasoline engine was connected gearbox and flywheel by a chain drive. Another set of chains wrapped around sprockets on a large wooden drum in the rear. That was the equivalent to the track on a modern snowmobile. To steer the contraption you moved the front runners from side to side by means of a lever.

The snow machine weighed something under 1,000 pounds. It wouldn’t win any races with a top speed of 12 miles per hour.

Sherwood didn’t apply for a patent on his car. He just built it. It was called “The Black Car.” He used magazine pictures as his construction guide.

The Sherwood store had been a stage stop for years. As motor vehicles began to appear in the Island Park area—his own was probably the first—Sherwood began selling gasoline and motor oil.

Joseph Sherwood died in 1919 due to complications from diabetes. The store he built continued in operation until the mid-1960s. The building has undergone extensive renovation and restoration. According to an article in the Rexburg Standard Journal, it may soon see another chapter in its history.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine. The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.

The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.  “The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

“The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

Published on June 03, 2024 04:00

June 2, 2024

Joseph Sherwood, Part One

I’m going to write a couple of posts about Joseph Sherwood, an enterprising man who came to what is now known as the Island Park area in about 1889. Today I’ll focus on the entrepreneurial Sherwood. Tomorrow we’ll talk about Sherwood the inventor.

Joseph Sherwood built a store on the north shore of Henrys Lake. We don’t know a lot about the structure, except that it burned and was subsequently replaced in about 1899. As a community focal point, the store became the post office of Lake, Idaho. Sherwood was named the postmaster.

Along with his wife Susan, Sherwood built a going enterprise. They raised cattle and in something of a precursor to Idaho’s famous Magic Valley trout farms, Sherwood packaged fish caught by locals and shipped them off to customers in Montana and California. This was no small operation. Sherwood once wrote in a letter that “The amount of fish usually caught in winter here varies from 50 to 90,000 pounds.”

Sherwood also ran a sawmill that was powered by gravity-fed water running in a canvas flume from a series of ponds he had developed above his place. He sold lumber commercially and used the sawmill to build his store.

And what a building it was—and is. It has since been modified, but the structure built in 1899 was 55 feet wide, 37 feet deep, and 46 feet high. It contained 27 rooms. The general store and post office was on the first floor, along with a family living area. The second floor had four bedrooms for rental to overnight stagecoach guests, a display room for Sherwood’s taxidermy, a photographic darkroom, and a photo gallery. A half-story attic was used for storage.

The store and museum was the home base for Sherwood’s boats. He rented them and often took visitors out on the lake from his launch.

About that taxidermy… Sherwood took a correspondence course to learn how to do it. He shared his knowledge with his second wife, Ann, after Susan’s death. Together they set out to mount at least once specimen of every critter native to Island Park. That room full of taxidermy mounts was why the store was often called the Sherwood Museum.

To say that Joseph Sherwood was self-sufficient would be like saying there were a few fish in Henrys Lake. One story, told in the National Register of Historic Places application for his building, was about his medical skills. He delivered he and Ann’s children himself, including Clarence Sherwood, who told this story. One day his father was thrown from a wagon some distance from their home. Joseph Sherwood fashioned a splint for his leg, got back into his wagon, and drove home. When he got home, with Ann’s help he set his leg. Then he hopped back in the wagon and headed for St. Anthony to attend a board meeting of the local bank, where he served as president.

Tomorrow I’ll conclude the Joseph Sherwood story with a little bit about his inventions.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Joseph Sherwood built a store on the north shore of Henrys Lake. We don’t know a lot about the structure, except that it burned and was subsequently replaced in about 1899. As a community focal point, the store became the post office of Lake, Idaho. Sherwood was named the postmaster.

Along with his wife Susan, Sherwood built a going enterprise. They raised cattle and in something of a precursor to Idaho’s famous Magic Valley trout farms, Sherwood packaged fish caught by locals and shipped them off to customers in Montana and California. This was no small operation. Sherwood once wrote in a letter that “The amount of fish usually caught in winter here varies from 50 to 90,000 pounds.”

Sherwood also ran a sawmill that was powered by gravity-fed water running in a canvas flume from a series of ponds he had developed above his place. He sold lumber commercially and used the sawmill to build his store.

And what a building it was—and is. It has since been modified, but the structure built in 1899 was 55 feet wide, 37 feet deep, and 46 feet high. It contained 27 rooms. The general store and post office was on the first floor, along with a family living area. The second floor had four bedrooms for rental to overnight stagecoach guests, a display room for Sherwood’s taxidermy, a photographic darkroom, and a photo gallery. A half-story attic was used for storage.

The store and museum was the home base for Sherwood’s boats. He rented them and often took visitors out on the lake from his launch.

About that taxidermy… Sherwood took a correspondence course to learn how to do it. He shared his knowledge with his second wife, Ann, after Susan’s death. Together they set out to mount at least once specimen of every critter native to Island Park. That room full of taxidermy mounts was why the store was often called the Sherwood Museum.

To say that Joseph Sherwood was self-sufficient would be like saying there were a few fish in Henrys Lake. One story, told in the National Register of Historic Places application for his building, was about his medical skills. He delivered he and Ann’s children himself, including Clarence Sherwood, who told this story. One day his father was thrown from a wagon some distance from their home. Joseph Sherwood fashioned a splint for his leg, got back into his wagon, and drove home. When he got home, with Ann’s help he set his leg. Then he hopped back in the wagon and headed for St. Anthony to attend a board meeting of the local bank, where he served as president.

Tomorrow I’ll conclude the Joseph Sherwood story with a little bit about his inventions.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Published on June 02, 2024 04:00