Rick Just's Blog, page 85

August 28, 2022

Wilke Dog Food (Tap to read)

So, you were probably wondering what else the Idaho State Checkers Champion of 1938 was good at. Yes? It’s surprising to me this hasn’t already been covered extensively in all the papers, but it has not. It falls to me, then, to supply that missing knowledge.

As everyone knows, the 1938 Idaho State Checkers Champion was Alfred Wilke who lived just outside of Boise about two miles west of the Cole School. That’s right, the Cole School that is no longer there.

It’s hard to pin down what Wilke was best known for, outside of his wicked checkers skill. Many would remember him as the man who bred white leghorn chickens at his home, which he called Wilketon Hatchery. In 1930 you could buy 1,000 “chix” for $95. Some would recall that his wife had a little bird business on the side, selling singing canaries, “the finest in a decade” if you believed her classified ads.

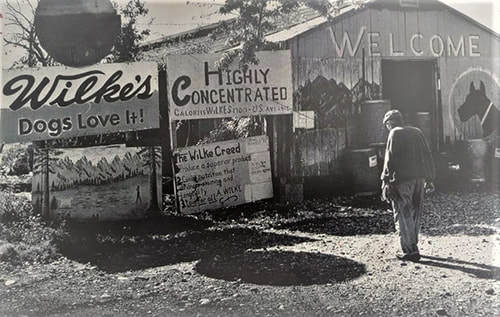

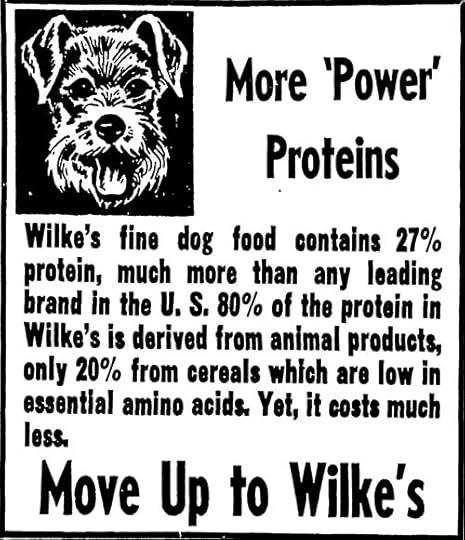

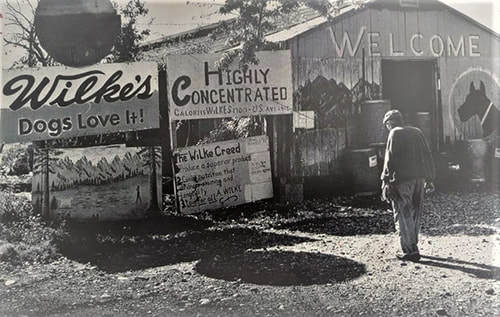

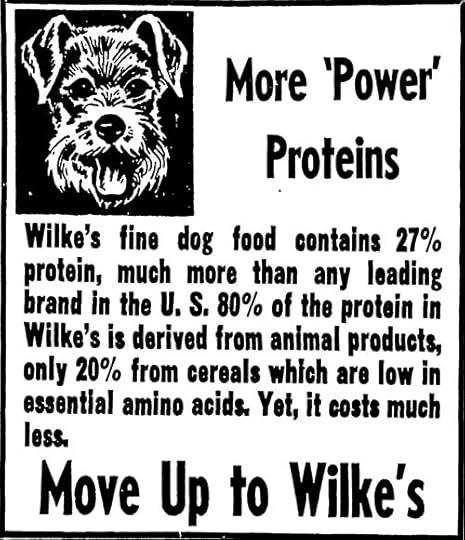

Working in all those chicken coops gave Wilke chronic bronchitis, so he switched careers in 1924. Taking what he’d learned about nutrition in the chicken business, he started Wilke’s Dog Food Plant at 8201 Fairview Avenue, where Boise Funeral Home is today. The establishment didn’t look like much, but the product was popular. Wilke sold the dog food all over Idaho and in adjoining states.

You can see in the photo that Wilke had a creed. The first point of the creed was to “Produce a superior product.” The second point can’t be read from the photo, but we know it involved nutrition and longevity. His third creed point was, “Love for all.” It almost sounds like he was building Subarus.

Wilke did love dogs. He bred and sold Irish setters and Airedales, “unprecedented guardians of the home,” in 1938.

One item in the picture to take special notice of is the landscape scene beneath the Wilke’s sign. Alfred Wilke was an amateur artist who participated in shows put on by the Boise Art Association and even had a show of his own in 1973 at Boise Blueprint, where they touted his “four decades of experience” in producing scenic Idaho art. No mention was made of his dog food or skill at checkers.

As everyone knows, the 1938 Idaho State Checkers Champion was Alfred Wilke who lived just outside of Boise about two miles west of the Cole School. That’s right, the Cole School that is no longer there.

It’s hard to pin down what Wilke was best known for, outside of his wicked checkers skill. Many would remember him as the man who bred white leghorn chickens at his home, which he called Wilketon Hatchery. In 1930 you could buy 1,000 “chix” for $95. Some would recall that his wife had a little bird business on the side, selling singing canaries, “the finest in a decade” if you believed her classified ads.

Working in all those chicken coops gave Wilke chronic bronchitis, so he switched careers in 1924. Taking what he’d learned about nutrition in the chicken business, he started Wilke’s Dog Food Plant at 8201 Fairview Avenue, where Boise Funeral Home is today. The establishment didn’t look like much, but the product was popular. Wilke sold the dog food all over Idaho and in adjoining states.

You can see in the photo that Wilke had a creed. The first point of the creed was to “Produce a superior product.” The second point can’t be read from the photo, but we know it involved nutrition and longevity. His third creed point was, “Love for all.” It almost sounds like he was building Subarus.

Wilke did love dogs. He bred and sold Irish setters and Airedales, “unprecedented guardians of the home,” in 1938.

One item in the picture to take special notice of is the landscape scene beneath the Wilke’s sign. Alfred Wilke was an amateur artist who participated in shows put on by the Boise Art Association and even had a show of his own in 1973 at Boise Blueprint, where they touted his “four decades of experience” in producing scenic Idaho art. No mention was made of his dog food or skill at checkers.

Published on August 28, 2022 09:30

August 27, 2022

A Twin Falls Grave (Tap to read)

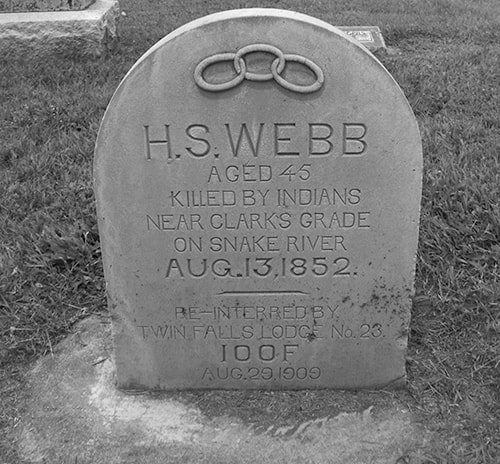

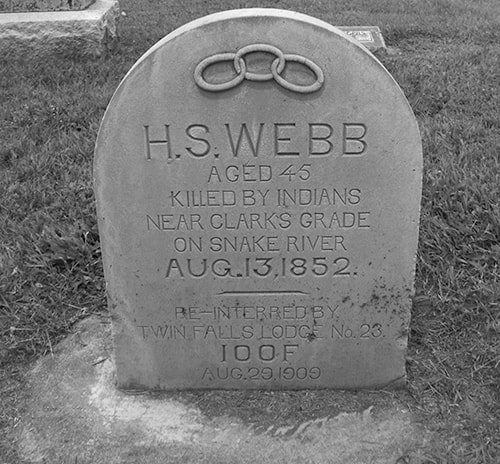

In June of 1908 someone found a gravesite associated with the Oregon Trail about seven miles from Twin Falls near the top of Clark’s Grade. Four graves were identified along with deteriorating wagon parts scattered in the area.

This seemed to tell the story of a massacre, probably by Indians, during which an immigrating family was killed, and their wagon destroyed. But there was more to the story. One of the gravesites was marked, pinning down the date of the massacre and giving the name of one of the victims.

The poplar marker had likely been cut from the family’s wagon. Because it faced east, and leaned slightly in that direction, the elements had not done its worst to the marker. It read, “H.S. Webb, August 13, ’52.” No markers were in evidence near the other graves. Speculation was that someone who knew Mr. Webb came along shortly after the massacre and buried he and his family.

But there was something else on the marker that piqued the interest of some in Twin Falls. Someone had carved three arching chain links into the wood. That symbol, connoting the motto, one word per link, of Friendship, Love, and Truth, is the symbol of the Odd Fellows. One of the tenants of the Odd Fellows fraternal organization is an ethic of reciprocity. Think Golden Rule. Some of the Twin Falls Odd Fellows apparently determined that what they would like for themselves if killed and buried where they fell, would be to have someone move their body to a dignified cemetery where a proper stone marker could be placed. In any case, that’s what they did, disinterring Mr. Webb and moving him to the Twin Falls Cemetery.

Upon digging up the fallen immigrant they discovered he had been buried in a three-foot hole. The upper half of his body was covered with barrel staves before dirt was added. Lava rocks had been placed over the grave to prevent it from being disturbed by wild animals.

From the bones the Odd Fellows determined that Webb was a large and powerfully built man about six feet tall and near 45 years of age when he was killed. From his jaw alone someone determined that he was probably “a determined and aggressive man.”

On August 29, 1909, just five years after the city was formed, the Odd Fellows and Rebekahs of Twin Fall Lodge 23 held a service in their hall, as well as a graveside service for H.S. Webb. One could only speculate whether or not the pioneer would have been pleased with his brothers for moving him away from the spot where his family is still buried.

This seemed to tell the story of a massacre, probably by Indians, during which an immigrating family was killed, and their wagon destroyed. But there was more to the story. One of the gravesites was marked, pinning down the date of the massacre and giving the name of one of the victims.

The poplar marker had likely been cut from the family’s wagon. Because it faced east, and leaned slightly in that direction, the elements had not done its worst to the marker. It read, “H.S. Webb, August 13, ’52.” No markers were in evidence near the other graves. Speculation was that someone who knew Mr. Webb came along shortly after the massacre and buried he and his family.

But there was something else on the marker that piqued the interest of some in Twin Falls. Someone had carved three arching chain links into the wood. That symbol, connoting the motto, one word per link, of Friendship, Love, and Truth, is the symbol of the Odd Fellows. One of the tenants of the Odd Fellows fraternal organization is an ethic of reciprocity. Think Golden Rule. Some of the Twin Falls Odd Fellows apparently determined that what they would like for themselves if killed and buried where they fell, would be to have someone move their body to a dignified cemetery where a proper stone marker could be placed. In any case, that’s what they did, disinterring Mr. Webb and moving him to the Twin Falls Cemetery.

Upon digging up the fallen immigrant they discovered he had been buried in a three-foot hole. The upper half of his body was covered with barrel staves before dirt was added. Lava rocks had been placed over the grave to prevent it from being disturbed by wild animals.

From the bones the Odd Fellows determined that Webb was a large and powerfully built man about six feet tall and near 45 years of age when he was killed. From his jaw alone someone determined that he was probably “a determined and aggressive man.”

On August 29, 1909, just five years after the city was formed, the Odd Fellows and Rebekahs of Twin Fall Lodge 23 held a service in their hall, as well as a graveside service for H.S. Webb. One could only speculate whether or not the pioneer would have been pleased with his brothers for moving him away from the spot where his family is still buried.

Published on August 27, 2022 04:00

August 26, 2022

Edward Pangborn (Tap to read)

In about 1919, St. Maries, that north Idaho logging town on the banks of the Shadowy St. Joe, was the site of a portentous meeting between famous aviators. Neither had yet risen to fame, but Edward Pangborn was well on his way.

Pangborn, who grew up in St. Maries and took civil engineering courses at the University of Idaho for a couple of years, learned to fly during World War I, becoming a flight instructor at Ellington Field in Houston. He gained a reputation there for stunt flying, earning the nickname “Upside Down Pang.”

It was stunt flying—barnstorming—that brought him back to St. Maries following the war. He was a pilot for Gates Flying Circus, and a partner in the operation. As barnstorming pilots often did, Pangborn offered short flights to local citizens. Little Gregory Boyington got his first ride in an airplane that day. He would later become famous as Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, a Medal of Honor winner, during World War II.

Pangborn’s fame grew during his nine years as a barnstormer. He was known particularly for changing planes in mid-air, walking out on the wing of one plane and slipping over to the wing of another flying wingtip to wingtip.

In 1931, Pangborn and co-pilot Hugh Herndon sought to break the record for circumnavigating the globe. Nasty weather over Siberia caused them to abandon their efforts. So, they set their sights on another record. The two flew to Japan where they hoped to win a $25,000 prize for being the first to complete a non-stop trans-Pacific flight.

Their attempt was plagued with problems. First, they were arrested for taking pictures while flying over Japanese naval installations. Paying a $1,000 fine got them released, but the Japanese kicked them out of the country. They could take off, but they would be arrested again if they tried to land in Japan because they didn’t have proper documentation.

One chance was all they needed. They filled their plane, a Bellanca CH-400 called Miss Veedol, with over 900 gallons of fuel, and took off on October 4, 1931. The term “flying by the seat of their pants” may not have been invented to describe this flight, but that is largely what they had to do. Their maps and charts had been stolen by a group who wanted a Japanese pilot to be the first to cross the Pacific non-stop.

Part of the plan to get across the ocean with limited fuel was to drop the landing gear from the plane so there would be less drag. The wheels fell away when the lever inside the cockpit was pulled, but a pair of struts stubbornly remained in place. Those caused unwanted drag, which would use precious fuel and make a belly landing—their plan—dangerous. Harkening back to his wing-walking days, Pangborn slipped out of the cockpit at 14,000 feet, barefoot, and removed the struts manually.

Everything went swimmingly from then on except for their inability to land and that time when the engine quit because the co-pilot had neglected to transfer fuel from the auxiliary tanks to the main on time. The plane, stripped of everything not absolutely necessary, didn’t have a starter. The plane also lacked survival gear, seat cushions, and a radio. Pangborn put the Bellanca into a nosedive to get the prop spinning fast enough to start the plane. We know that worked because I did not just write “and then they died.”

Weather was again their enemy, as it had been over Siberia during the global attempt. They planned to land in Seattle or Vancouver, B.C., but both airfields were socked in. So was Mt. Rainier, which they came close to kissing. So, on to Boise! But no, fog had Boise, Spokane, and Pasco closed.

All they wanted to do, badly, was land. And, eventually, they did. Badly, one could say. Of course, given that the plane had no landing gear any landing one could walk away from was perfect. Pangborn and Herndon belly-landed in the dirt field at Wenatchee, 41 hours and 13 minutes after taking off from Japan, officially becoming the first to fly non-stop across the Pacific.

Trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic flights would become routine for Pangborn, who joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939. He made 170 trans-oceanic flights in helping to recruit American pilots to the cause. When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, he signed up with the U.S. Army Air Force.

Pangborn passed away in 1958 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Pangborn, who grew up in St. Maries and took civil engineering courses at the University of Idaho for a couple of years, learned to fly during World War I, becoming a flight instructor at Ellington Field in Houston. He gained a reputation there for stunt flying, earning the nickname “Upside Down Pang.”

It was stunt flying—barnstorming—that brought him back to St. Maries following the war. He was a pilot for Gates Flying Circus, and a partner in the operation. As barnstorming pilots often did, Pangborn offered short flights to local citizens. Little Gregory Boyington got his first ride in an airplane that day. He would later become famous as Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, a Medal of Honor winner, during World War II.

Pangborn’s fame grew during his nine years as a barnstormer. He was known particularly for changing planes in mid-air, walking out on the wing of one plane and slipping over to the wing of another flying wingtip to wingtip.

In 1931, Pangborn and co-pilot Hugh Herndon sought to break the record for circumnavigating the globe. Nasty weather over Siberia caused them to abandon their efforts. So, they set their sights on another record. The two flew to Japan where they hoped to win a $25,000 prize for being the first to complete a non-stop trans-Pacific flight.

Their attempt was plagued with problems. First, they were arrested for taking pictures while flying over Japanese naval installations. Paying a $1,000 fine got them released, but the Japanese kicked them out of the country. They could take off, but they would be arrested again if they tried to land in Japan because they didn’t have proper documentation.

One chance was all they needed. They filled their plane, a Bellanca CH-400 called Miss Veedol, with over 900 gallons of fuel, and took off on October 4, 1931. The term “flying by the seat of their pants” may not have been invented to describe this flight, but that is largely what they had to do. Their maps and charts had been stolen by a group who wanted a Japanese pilot to be the first to cross the Pacific non-stop.

Part of the plan to get across the ocean with limited fuel was to drop the landing gear from the plane so there would be less drag. The wheels fell away when the lever inside the cockpit was pulled, but a pair of struts stubbornly remained in place. Those caused unwanted drag, which would use precious fuel and make a belly landing—their plan—dangerous. Harkening back to his wing-walking days, Pangborn slipped out of the cockpit at 14,000 feet, barefoot, and removed the struts manually.

Everything went swimmingly from then on except for their inability to land and that time when the engine quit because the co-pilot had neglected to transfer fuel from the auxiliary tanks to the main on time. The plane, stripped of everything not absolutely necessary, didn’t have a starter. The plane also lacked survival gear, seat cushions, and a radio. Pangborn put the Bellanca into a nosedive to get the prop spinning fast enough to start the plane. We know that worked because I did not just write “and then they died.”

Weather was again their enemy, as it had been over Siberia during the global attempt. They planned to land in Seattle or Vancouver, B.C., but both airfields were socked in. So was Mt. Rainier, which they came close to kissing. So, on to Boise! But no, fog had Boise, Spokane, and Pasco closed.

All they wanted to do, badly, was land. And, eventually, they did. Badly, one could say. Of course, given that the plane had no landing gear any landing one could walk away from was perfect. Pangborn and Herndon belly-landed in the dirt field at Wenatchee, 41 hours and 13 minutes after taking off from Japan, officially becoming the first to fly non-stop across the Pacific.

Trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic flights would become routine for Pangborn, who joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939. He made 170 trans-oceanic flights in helping to recruit American pilots to the cause. When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, he signed up with the U.S. Army Air Force.

Pangborn passed away in 1958 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Published on August 26, 2022 04:00

August 25, 2022

Placer Mining (Tap to read)

When you think of a miner, you probably picture some old Gabby Hayes character with a pinned back hat brim crouched over a stream with a pan, dreams of gold glittering in his eye. That’s not a bad picture of a prospector, because most miners (some of whom were also minors) started out that way. Panning for gold is slow and tedious. Shake, shake, shake, rinse, shake, shake, shake, rinse, and repeat until your beard grows down to your waist. Gold flecks are heavier than most of the surrounding material so they sink to the bottom of the pan. A good panner could sift through about a yard of sand and gravel a day. If they turned up $3 or $4 worth of gold, that was excellent. It was about what they might make for a day as, say, a captain in the army in the 1860s, or your average bricklayer in the East.

But miners did not dream of bricklayer wages. They wanted more. That’s why prospectors were typically testing the waters, so to speak, in search of a vein higher upstream. Let’s assume for a moment that they couldn’t find that ledge of quartz, but the quantity of gold in the stream gravel was pretty good. They were stuck with mining the streambed itself or an alluvial fan where water once ran. That’s called “placer mining.” In that case they needed a way to sift more sand and gravel faster in order to have more gold at the end of the day.

Rockers were boxes into which the miner dumped gravel and sand scooped from a stream bottom or alluvial deposit. At the top of the box was a sieve where the larger bits of gravel were screened out. Below that was an incline set up with a series of bumps or ribs down the length of the box over which sand would run when the worker poured water into the device while rocking it back and forth, the equivalent of shaking a gold pan. A piece of draping canvas helped filter out the gold from the lighter stuff. Rockers were especially useful if the material a miner was working with was partially cemented, meaning sticky clay had to be washed away. A good rocker operator could triple his day’s take over panning, meaning he was up close to what a major general might make.

Still, it was pretty tedious work and the miner was not making the fortune he was dreaming of. A faster production method was called for.

The quickest way to pull gold out of a streambed for one or two men was a sluice running into a rocker. The downside was that you needed a downside. That is, you needed some elevation for water to pick up some speed to wash over the material you were working. Sometimes that meant digging a ditch, which was a lot of work. A sluice was only practical if the bits of gold were fairly large. Gold “dust” would float right out.

A sluice running through a giant could handle 500 yards of gravel a day, compared with that one yard a man with a pan could process. That meant a miner could work material that was a lot less rich and still pull much more gold out in a day.

This sloshing escalation of mining methods could be carried to ends that a single miner couldn’t handle, such as hydraulic mining and large-scale dredging.

No matter the method, the idea behind placer mining was to rinse away the rubble and expose the gold in the remaining sand. It’s a fairly benign operation at the lower end of the scale, but the more material an operation uses the more a streambed or ancient deposit is disturbed. See the aerial below of the windrows of gravel left by the Yankee Fork Dredge.

This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.

This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.  Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

But miners did not dream of bricklayer wages. They wanted more. That’s why prospectors were typically testing the waters, so to speak, in search of a vein higher upstream. Let’s assume for a moment that they couldn’t find that ledge of quartz, but the quantity of gold in the stream gravel was pretty good. They were stuck with mining the streambed itself or an alluvial fan where water once ran. That’s called “placer mining.” In that case they needed a way to sift more sand and gravel faster in order to have more gold at the end of the day.

Rockers were boxes into which the miner dumped gravel and sand scooped from a stream bottom or alluvial deposit. At the top of the box was a sieve where the larger bits of gravel were screened out. Below that was an incline set up with a series of bumps or ribs down the length of the box over which sand would run when the worker poured water into the device while rocking it back and forth, the equivalent of shaking a gold pan. A piece of draping canvas helped filter out the gold from the lighter stuff. Rockers were especially useful if the material a miner was working with was partially cemented, meaning sticky clay had to be washed away. A good rocker operator could triple his day’s take over panning, meaning he was up close to what a major general might make.

Still, it was pretty tedious work and the miner was not making the fortune he was dreaming of. A faster production method was called for.

The quickest way to pull gold out of a streambed for one or two men was a sluice running into a rocker. The downside was that you needed a downside. That is, you needed some elevation for water to pick up some speed to wash over the material you were working. Sometimes that meant digging a ditch, which was a lot of work. A sluice was only practical if the bits of gold were fairly large. Gold “dust” would float right out.

A sluice running through a giant could handle 500 yards of gravel a day, compared with that one yard a man with a pan could process. That meant a miner could work material that was a lot less rich and still pull much more gold out in a day.

This sloshing escalation of mining methods could be carried to ends that a single miner couldn’t handle, such as hydraulic mining and large-scale dredging.

No matter the method, the idea behind placer mining was to rinse away the rubble and expose the gold in the remaining sand. It’s a fairly benign operation at the lower end of the scale, but the more material an operation uses the more a streambed or ancient deposit is disturbed. See the aerial below of the windrows of gravel left by the Yankee Fork Dredge.

This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.

This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.  Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

Published on August 25, 2022 04:00

August 24, 2022

James Hart (Tap to read)

Things can get noisy when a fire is raging. That’s why the foreman of the Ada Hook and Ladder Company would use a “speaking trumpet” when they were called out on a fire. Speaking Trumpets were essentially brass megaphones. They sometimes served a second purpose, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. They could be inscribed and awarded to honor firefighters for their service.

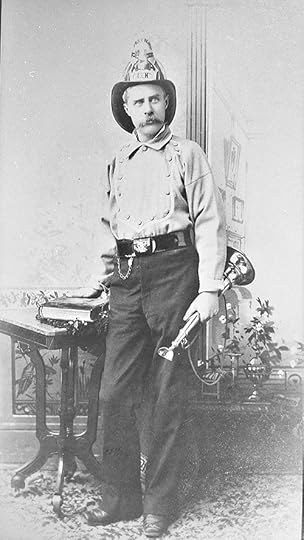

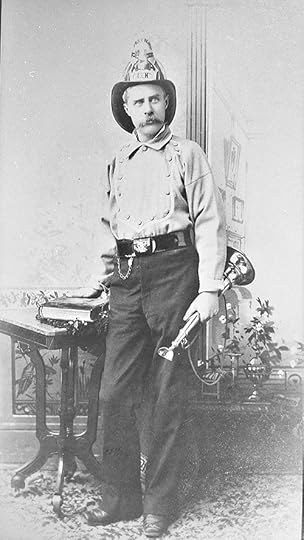

The fire foreman holding the speaking trumpet in this photo is James H. Hart. It was probably taken around 1900.

Hart was born in in New York City in 1834. He came west to earn his fortune in the gold fields and found that serving liquor to miners was a better way to get gold than digging for it. According to Hugh Hartman’s book, The Founding Fathers of Boise, Hart started Jim’s Drinking Saloon in Placerville in 1863 with $9.75. That first year he grossed $30,000 and netted $12,000. His business acumen may have been what got him elected city treasurer.

According to Hartman’s book, Jim Hart had a special way of building up the town treasury. He was quoted as saying, “We had a plaza in the center of the town, on which was a flag pole. I’d play a trick on some good marksman by hinting that he couldn’t hit the pole with his gun. In the meantime, I’d have the Sheriff stationed ready to make the arrest as soon as the man shot. Then the judge would fine him ten dollars, and to get even he’d play the trick on someone else. Then when we had about fifty dollars in the treasury, we would blow it on champagne.”

Hart and his family moved to Boise in 1871 where he was a saloon keeper, a city tax assessor, the proprietor of Jimmy Hart’s Grocery and Bakery Sample Room, and a volunteer firefighter, which is something to trumpet about.

The fire foreman holding the speaking trumpet in this photo is James H. Hart. It was probably taken around 1900.

Hart was born in in New York City in 1834. He came west to earn his fortune in the gold fields and found that serving liquor to miners was a better way to get gold than digging for it. According to Hugh Hartman’s book, The Founding Fathers of Boise, Hart started Jim’s Drinking Saloon in Placerville in 1863 with $9.75. That first year he grossed $30,000 and netted $12,000. His business acumen may have been what got him elected city treasurer.

According to Hartman’s book, Jim Hart had a special way of building up the town treasury. He was quoted as saying, “We had a plaza in the center of the town, on which was a flag pole. I’d play a trick on some good marksman by hinting that he couldn’t hit the pole with his gun. In the meantime, I’d have the Sheriff stationed ready to make the arrest as soon as the man shot. Then the judge would fine him ten dollars, and to get even he’d play the trick on someone else. Then when we had about fifty dollars in the treasury, we would blow it on champagne.”

Hart and his family moved to Boise in 1871 where he was a saloon keeper, a city tax assessor, the proprietor of Jimmy Hart’s Grocery and Bakery Sample Room, and a volunteer firefighter, which is something to trumpet about.

Published on August 24, 2022 04:00

August 23, 2022

Colonel Wright (Tap to read)

Fame and infamy today, all wrapped up in one name.

The first steamboat to reach Lewiston was the sternwheeler Colonel Wright in 1859, captained by Leonard White. As the first of what would be countless vessels to ply the Columbia and Snake Rivers to that inland port, the Colonel Wright deserves its fame.

The infamy comes in when one explores the provenance of the boat’s name. It was named after Colonel George Wright who was known as an Indian fighter in Washington and Oregon territories at the time the steamer was built. He is probably best-known today as the military officer who ordered the horse slaughter.

A monument at mile marker 2 on the Washington side of the Centennial Trail that runs from Spokane to Coeur d’Alene tells the story of Horse Slaughter Camp. It’s within walking distance of the Idaho border, though in 1858 there was no border and no Idaho. The northern part of today’s Gem State was part of Washington Territory.

The monument tells the story: “In 1858 Col. George Wright with 700 soldiers was sent from Walla Walla to suppress an Indian outbreak. After defeating the Indians in two battles he captured 800 Indian horses. To prevent the Indians from waging further warfare he killed the horses on the bank of the river directly north of this monument.”

The date of the slaughter was September 8, 1858. The animals belonged to the Palouse Tribe.

Col. Wright kept back 150 horses for use by his soldiers. They proved intractable and were later destroyed.

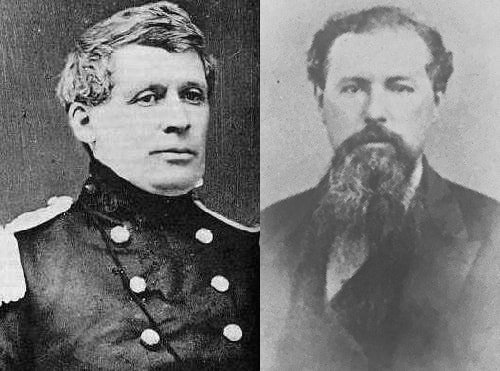

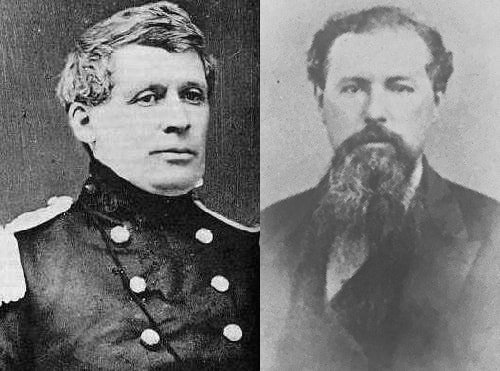

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

The first steamboat to reach Lewiston was the sternwheeler Colonel Wright in 1859, captained by Leonard White. As the first of what would be countless vessels to ply the Columbia and Snake Rivers to that inland port, the Colonel Wright deserves its fame.

The infamy comes in when one explores the provenance of the boat’s name. It was named after Colonel George Wright who was known as an Indian fighter in Washington and Oregon territories at the time the steamer was built. He is probably best-known today as the military officer who ordered the horse slaughter.

A monument at mile marker 2 on the Washington side of the Centennial Trail that runs from Spokane to Coeur d’Alene tells the story of Horse Slaughter Camp. It’s within walking distance of the Idaho border, though in 1858 there was no border and no Idaho. The northern part of today’s Gem State was part of Washington Territory.

The monument tells the story: “In 1858 Col. George Wright with 700 soldiers was sent from Walla Walla to suppress an Indian outbreak. After defeating the Indians in two battles he captured 800 Indian horses. To prevent the Indians from waging further warfare he killed the horses on the bank of the river directly north of this monument.”

The date of the slaughter was September 8, 1858. The animals belonged to the Palouse Tribe.

Col. Wright kept back 150 horses for use by his soldiers. They proved intractable and were later destroyed.

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Published on August 23, 2022 04:00

August 22, 2022

Leave the Chalk Home (Tap to read)

Idaho has a plethora of petroglyphs and pictographs. There. I mostly just wanted to use all those alliterative Ps. That alone doesn’t make much a of blog post, so I’d better scramble for a little information so you get your money’s worth.

First, what’s the difference between petroglyphs and pictographs? Petroglyphs are chipped or scratched into a rock’s surface. Pictographs are painted onto a stone surface using natural dyes and pigments. One handy way to confuse yourself when remembering what the difference is is to remember the “pic” in pictograph should mean that someone “picked” the image into the rock, except that it doesn’t. Helpful? No? That’s just the way my mind works.

Now that you’re about to quit reading because your brain hurts, let me assure you that a public service announcement is coming up. Please stand by.

Famous sites for petroglyphs and pictographs in Idaho include Hells Canyon, the Middle Fork of the Salmon, and numerous sites along the Snake River. If you’d like to see some terrific examples and learn more, visit Celebration Park near Nampa.

I’ve mentioned before that interpreting what is sometimes called “rock writing” is not an exact science. That’s because it’s not really writing. The indigenous people of what is now Idaho did not have a handy alphabet they could use to get their message across. The representations carved into or painted on rock often deviated with the artist. Still, they probably were trying to depict what they saw or tell some kind of story. Maybe you can figure out what they were trying to say. If only there was a way to make the images a little clearer. Hey! What if we traced on top of them with chalk so they would show up better in a photo?

And, here comes the PSA. Don’t do that. It’s illegal in many places and problematic everywhere. It used to be a standard practice, but scientists have learned that chalk dust can bake into the rock over the years helping to obliterate the rock art. It is especially damaging to pictographs, potentially destroying the dyes used to create them and leaving calcium behind in concentrations high enough to make them impossible to carbon date.

Another issue with chalking is that it shows the bias of the chalker. They trace what they “see.” The rock art is often faded so interpretation is sometimes dicey. In one famous example chalking the rock art in a Utah cave created the belief that the indigenous artist was depicting a winged monster, maybe even a pterosaur. That excited people who were eager to prove that dinosaurs and humans existed at the same time.

In 2015, scientists used a portable x-ray florescence device to bring out the original detail on the “winged monster.” It turned out that the rock art was originally a depiction of a couple of four-legged animals, maybe a sheep and a dog.

We humans are very good at identifying figures in clouds and wallpaper stains as various objects, animals, and people. That tendency is called pareidolia. And now I regret that I didn’t use that word in my alliterative first sentence. But, back to that Utah cave. When someone chalked those two critters, they “saw” variations in the color of the rock combined with the rock art that looked like a winged beast. Subsequent chalkers “saw” the same thing because of the original chalker’s pareidolia.

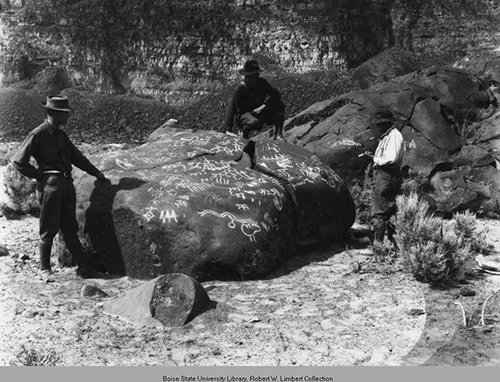

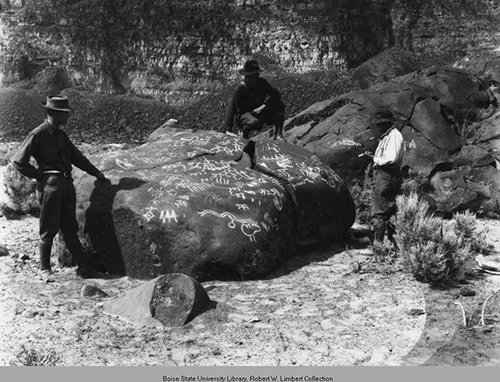

So, no chalking, please. It’s too bad, though. Look how well the rock art shows up in this picture of Map Rock near Murphy. That’s Robert Limbert in the white shirt on the right taking notes. We don’t know who the other two people are, perhaps because Limbert didn’t make note of that. The picture is courtesy of Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

First, what’s the difference between petroglyphs and pictographs? Petroglyphs are chipped or scratched into a rock’s surface. Pictographs are painted onto a stone surface using natural dyes and pigments. One handy way to confuse yourself when remembering what the difference is is to remember the “pic” in pictograph should mean that someone “picked” the image into the rock, except that it doesn’t. Helpful? No? That’s just the way my mind works.

Now that you’re about to quit reading because your brain hurts, let me assure you that a public service announcement is coming up. Please stand by.

Famous sites for petroglyphs and pictographs in Idaho include Hells Canyon, the Middle Fork of the Salmon, and numerous sites along the Snake River. If you’d like to see some terrific examples and learn more, visit Celebration Park near Nampa.

I’ve mentioned before that interpreting what is sometimes called “rock writing” is not an exact science. That’s because it’s not really writing. The indigenous people of what is now Idaho did not have a handy alphabet they could use to get their message across. The representations carved into or painted on rock often deviated with the artist. Still, they probably were trying to depict what they saw or tell some kind of story. Maybe you can figure out what they were trying to say. If only there was a way to make the images a little clearer. Hey! What if we traced on top of them with chalk so they would show up better in a photo?

And, here comes the PSA. Don’t do that. It’s illegal in many places and problematic everywhere. It used to be a standard practice, but scientists have learned that chalk dust can bake into the rock over the years helping to obliterate the rock art. It is especially damaging to pictographs, potentially destroying the dyes used to create them and leaving calcium behind in concentrations high enough to make them impossible to carbon date.

Another issue with chalking is that it shows the bias of the chalker. They trace what they “see.” The rock art is often faded so interpretation is sometimes dicey. In one famous example chalking the rock art in a Utah cave created the belief that the indigenous artist was depicting a winged monster, maybe even a pterosaur. That excited people who were eager to prove that dinosaurs and humans existed at the same time.

In 2015, scientists used a portable x-ray florescence device to bring out the original detail on the “winged monster.” It turned out that the rock art was originally a depiction of a couple of four-legged animals, maybe a sheep and a dog.

We humans are very good at identifying figures in clouds and wallpaper stains as various objects, animals, and people. That tendency is called pareidolia. And now I regret that I didn’t use that word in my alliterative first sentence. But, back to that Utah cave. When someone chalked those two critters, they “saw” variations in the color of the rock combined with the rock art that looked like a winged beast. Subsequent chalkers “saw” the same thing because of the original chalker’s pareidolia.

So, no chalking, please. It’s too bad, though. Look how well the rock art shows up in this picture of Map Rock near Murphy. That’s Robert Limbert in the white shirt on the right taking notes. We don’t know who the other two people are, perhaps because Limbert didn’t make note of that. The picture is courtesy of Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Published on August 22, 2022 04:00

August 21, 2022

Pappy Boyington (Tap to read)

Gregory Hallenbeck was born in Coeur d’Alene in 1912, but at age three he moved with his family to the logging town of St. Maries. It was there, at age 6, that Gregory had his first airplane ride with barnstormer Clyde Pangborn. He would cruise the clouds many times after that.

The Hallenbeck family moved to Tacoma when he was twelve. Gregory attended the University of Washington, graduating in 1934 with a BS in aeronautical engineering. He married and went to work for Boeing as an engineer and draftsman.

Gregory wanted to fly, not just work on airplane design. In 1935 he applied for a slot with the Navy as an aviation cadet. They rejected him because he was married. He wasn’t going to get a divorce, so that path into the air seemed closed. That is, until he got a copy of his birth certificate and learned that Ellsworth Hallenback, his father, was not really his father. Gregory’s father was a dentist by the name of Charles Boyington. Boyington and Gregory’s mother had divorced when Gregory was a baby.

Finding out your personal history was not what you thought it was might have been traumatic for the young man, but Gregory changed his name to his birth name and reapplied to the Navy program. Under that new/old name he didn’t bother to mention that he was married. They accepted him as an aviation cadet.

In 1937, Gregory Boyington became second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. Then in 1941, Boyington took what might have seemed to be a detour. He resigned his commission in the Marine Corps and went to work for the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company. The company was real, but the job was a ruse. American entrepreneur William Pawley ran the company in China. In 1941 he began recruiting American pilots for his American Volunteer Group, also known as the Flying Tigers. President Franklin Roosevelt had authorized the covert operation where the US pilots would fly airplanes marked with the colors of China, fighting the Japanese. Ironically, they didn’t see their first action until 12 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Boyington was credited with the destruction of three Japanese aircraft during his brief stint with the Flying Tigers, two in the air and one on the ground. In September of 1942 he rejoined the Marine Corps where his story would become legendary. A year later he would become the commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 214, nicknamed the Black Sheep Squadron.

It was while he was with the Black Sheep that he earned a nickname. They called him “Gramps” because at 31 was years older than most of the pilots. That morphed into “Pappy,” giving him the moniker that would stay with him in the history books, Gregory “Pappy” Boyington,

During his first tour “Pappy” took down 14 enemy fighters in 32 days. He shared the bravura and a bit of the PR man with Pangborn, the barnstormer who first took him into the skies. Boyington and his men would buzz enemy airfields luring fighters into the sky where they could be picked off. The PR man appeared when he boasted that he and his squadron would shoot down a Japanese Zero for every cap the ball players in the World Series would send them. They got 20 hats. The Japanese lost 20 aircraft, and then some.

But his luck didn’t hold. In January, 1944, Boyington was shot down over the Pacific just after making his own 26th kill. He was presumed dead, but he had actually been plucked out of the water by a Japanese submarine. For nearly two years Boyington was a POW, freed finally when American forces liberated the Omori Prison Camp.

For his wartime heroics Gregory “Pappy” Boyington received the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross. His 1958 autobiography, Baa Baa Black Sheep was used as the basis for the TV series that ran for a couple of years in the 70s.

Boyington, a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer in 1988 at age 75.

The Hallenbeck family moved to Tacoma when he was twelve. Gregory attended the University of Washington, graduating in 1934 with a BS in aeronautical engineering. He married and went to work for Boeing as an engineer and draftsman.

Gregory wanted to fly, not just work on airplane design. In 1935 he applied for a slot with the Navy as an aviation cadet. They rejected him because he was married. He wasn’t going to get a divorce, so that path into the air seemed closed. That is, until he got a copy of his birth certificate and learned that Ellsworth Hallenback, his father, was not really his father. Gregory’s father was a dentist by the name of Charles Boyington. Boyington and Gregory’s mother had divorced when Gregory was a baby.

Finding out your personal history was not what you thought it was might have been traumatic for the young man, but Gregory changed his name to his birth name and reapplied to the Navy program. Under that new/old name he didn’t bother to mention that he was married. They accepted him as an aviation cadet.

In 1937, Gregory Boyington became second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. Then in 1941, Boyington took what might have seemed to be a detour. He resigned his commission in the Marine Corps and went to work for the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company. The company was real, but the job was a ruse. American entrepreneur William Pawley ran the company in China. In 1941 he began recruiting American pilots for his American Volunteer Group, also known as the Flying Tigers. President Franklin Roosevelt had authorized the covert operation where the US pilots would fly airplanes marked with the colors of China, fighting the Japanese. Ironically, they didn’t see their first action until 12 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Boyington was credited with the destruction of three Japanese aircraft during his brief stint with the Flying Tigers, two in the air and one on the ground. In September of 1942 he rejoined the Marine Corps where his story would become legendary. A year later he would become the commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 214, nicknamed the Black Sheep Squadron.

It was while he was with the Black Sheep that he earned a nickname. They called him “Gramps” because at 31 was years older than most of the pilots. That morphed into “Pappy,” giving him the moniker that would stay with him in the history books, Gregory “Pappy” Boyington,

During his first tour “Pappy” took down 14 enemy fighters in 32 days. He shared the bravura and a bit of the PR man with Pangborn, the barnstormer who first took him into the skies. Boyington and his men would buzz enemy airfields luring fighters into the sky where they could be picked off. The PR man appeared when he boasted that he and his squadron would shoot down a Japanese Zero for every cap the ball players in the World Series would send them. They got 20 hats. The Japanese lost 20 aircraft, and then some.

But his luck didn’t hold. In January, 1944, Boyington was shot down over the Pacific just after making his own 26th kill. He was presumed dead, but he had actually been plucked out of the water by a Japanese submarine. For nearly two years Boyington was a POW, freed finally when American forces liberated the Omori Prison Camp.

For his wartime heroics Gregory “Pappy” Boyington received the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross. His 1958 autobiography, Baa Baa Black Sheep was used as the basis for the TV series that ran for a couple of years in the 70s.

Boyington, a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer in 1988 at age 75.

Published on August 21, 2022 04:00

August 20, 2022

The Boise Shoshoni (Tap to read)

Boise was known for its trees long before it was a city, or even a town. The first people who lived where what is now the City of Trees is located, the Northern Shoshoni, called it Subu Wiki, meaning something like “willows in many rows.” The Nez Perce, who knew it as a home of the Shoshoni called it Cup cop pa ala, or “the much feast cottonwood valley,” probably in recognition of the rendezvous many bands held along the Boise River. Hudson’s Bay trapper Donald McKenzie witnessed one of those rendezvous in 1819 and reported the crowd gathered to be “more than 10,000 souls” camped along the river between Table Rock and Eagle Island.

We recognize Boise as a good place to live today for many of the same reasons the indigenous people did. It has mild winters and mostly moderate summers. There are hot springs to keep sweat lodges steaming or the capitol heated. The river provides a good fishery.

In those days, the Boise River provided an outstanding fishery that was essential to the subsistence of the Shoshoni. When the first white settlers came into the valley, they wrote of raking salmon out of the river with forked willow branches the fish were so plentiful.

Prior to pioneer settlement the Shoshoni hunted bison on the Snake River Plain, especially after 1700 when they acquired horses, the first Northwest Tribe to do so.

Compare this life of plenty the Northern Shoshoni led with their miserable last few years in the Boise Valley.

In 1864 the Boise Shoshoni signed a treaty with Idaho Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, whom it is always pointed out hailed from Lyonsdale, New York, largely because he never failed to mention it. The treaty gave the natives a never-defined amount of money and a not described place to live in the indistinct future in exchange for their homeland of hundreds of years. Though their land was gobbled up, the exchange went only that far. Lyon disappeared along with $50,000 meant for the Indians. Lyon insisted thieves had stolen the money from him while he was en route to Washington, D.C. Why he had the money with him in the first place was never explained. Possibly for safe keeping.

What followed, for the Shoshoni, were several years of waiting on the outskirts of Boise for the promises of the treaty to be kept. It was never ratified by the U.S. Senate, though that would probably not have made much difference.

This encampment of Indians is seldom mentioned in Boise history. Carol Lynn MacGregor brought it to light in her excellent book, Boise, Idaho, 1882-1910 from which much of the information for this post was taken.

Over 1,000 Shoshoni and 150 Bannock awaited promises just outside of town. They did what they could to make a living, fishing and hunting as they always had, but with much reduced opportunity. Some took odd jobs in town to earn money for food. Disease in the Shoshoni camp was rampant, with many of the natives suffering from measles and consumption (tuberculosis).

Finally, in 1869, after five years of being homeless in their traditional homeland, the Indians were moved to the reservation at Fort Hall. Today, few but the willows and cottonwoods remember the people who first gave a name to the valley.

Castle Rock, near the old Idaho Penitentiary, held special significance to the Boise Shoshoni.

We recognize Boise as a good place to live today for many of the same reasons the indigenous people did. It has mild winters and mostly moderate summers. There are hot springs to keep sweat lodges steaming or the capitol heated. The river provides a good fishery.

In those days, the Boise River provided an outstanding fishery that was essential to the subsistence of the Shoshoni. When the first white settlers came into the valley, they wrote of raking salmon out of the river with forked willow branches the fish were so plentiful.

Prior to pioneer settlement the Shoshoni hunted bison on the Snake River Plain, especially after 1700 when they acquired horses, the first Northwest Tribe to do so.

Compare this life of plenty the Northern Shoshoni led with their miserable last few years in the Boise Valley.

In 1864 the Boise Shoshoni signed a treaty with Idaho Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, whom it is always pointed out hailed from Lyonsdale, New York, largely because he never failed to mention it. The treaty gave the natives a never-defined amount of money and a not described place to live in the indistinct future in exchange for their homeland of hundreds of years. Though their land was gobbled up, the exchange went only that far. Lyon disappeared along with $50,000 meant for the Indians. Lyon insisted thieves had stolen the money from him while he was en route to Washington, D.C. Why he had the money with him in the first place was never explained. Possibly for safe keeping.

What followed, for the Shoshoni, were several years of waiting on the outskirts of Boise for the promises of the treaty to be kept. It was never ratified by the U.S. Senate, though that would probably not have made much difference.

This encampment of Indians is seldom mentioned in Boise history. Carol Lynn MacGregor brought it to light in her excellent book, Boise, Idaho, 1882-1910 from which much of the information for this post was taken.

Over 1,000 Shoshoni and 150 Bannock awaited promises just outside of town. They did what they could to make a living, fishing and hunting as they always had, but with much reduced opportunity. Some took odd jobs in town to earn money for food. Disease in the Shoshoni camp was rampant, with many of the natives suffering from measles and consumption (tuberculosis).

Finally, in 1869, after five years of being homeless in their traditional homeland, the Indians were moved to the reservation at Fort Hall. Today, few but the willows and cottonwoods remember the people who first gave a name to the valley.

Castle Rock, near the old Idaho Penitentiary, held special significance to the Boise Shoshoni.

Published on August 20, 2022 04:00

August 19, 2022

The ONLY State Flag (Tap to read)

In doing research for my book, Symbols, Signs, and Songs, (see the column on the left) ran across a little interesting history on Idaho’s state flag. Since it is largely the state seal centered on a blue background, one would think we would have had an Idaho state flag for as long as we’ve had a seal since 1891. Not so.

It took the Legislature 17 years to pass a law creating an Idaho State Flag. Even then they punted to the adjutant general, delegating the duty of coming up with the design and specifying that the flag would be blue and have the word Idaho on it. They appropriated 100 dollars to make that happen on March 12, 1907.

It seemed odd to me that they put 100 dollars in the adjutant general’s budget. Why would he need anything? He could just send a flag company a picture of the state seal and tell them how it was supposed to appear on flags. Voila! Make some flags!

My misunderstanding was that the 100 dollars was for the cost of making a single flag. The state wasn’t planning on waving a flag from every courthouse in Idaho. The Legislature had the adjutant general design then order one flag.

Idaho got along with a single official state flag for years. It made the headlines in 1926 that the flag was traveling out of state with Governor C.C. Moore so that both could attend the governors’ conference in Cheyenne. The stay-at-home flag had only travelled out of state a couple of times before that. It lived in the governor’s office when not visiting other states. Today that original flag is in the possession of the Idaho State Historical Society. I am one of thousands who fly the flag—the mass-produced flag (below)—every day.

It took the Legislature 17 years to pass a law creating an Idaho State Flag. Even then they punted to the adjutant general, delegating the duty of coming up with the design and specifying that the flag would be blue and have the word Idaho on it. They appropriated 100 dollars to make that happen on March 12, 1907.

It seemed odd to me that they put 100 dollars in the adjutant general’s budget. Why would he need anything? He could just send a flag company a picture of the state seal and tell them how it was supposed to appear on flags. Voila! Make some flags!

My misunderstanding was that the 100 dollars was for the cost of making a single flag. The state wasn’t planning on waving a flag from every courthouse in Idaho. The Legislature had the adjutant general design then order one flag.

Idaho got along with a single official state flag for years. It made the headlines in 1926 that the flag was traveling out of state with Governor C.C. Moore so that both could attend the governors’ conference in Cheyenne. The stay-at-home flag had only travelled out of state a couple of times before that. It lived in the governor’s office when not visiting other states. Today that original flag is in the possession of the Idaho State Historical Society. I am one of thousands who fly the flag—the mass-produced flag (below)—every day.

Published on August 19, 2022 04:00