Rick Just's Blog, page 88

July 29, 2022

The State Dance (Tap to read)

Our state’s claim to the “Hokey Pokey” aside, the dance was snubbed when in 1989 the Legislature declared the square dance Idaho’s official state dance. It came out of the Senate Commerce and Labor Committee with a “Do Pass—with enthusiasm!” recommendation.

The National Folk Dance Committee tried to make the square dance the official national dance in 1988, without success. As often happens when something fails on the national level, the group aimed their sites at the states. Idaho couldn’t resist the lobbyists from Big Dance. It became one of 19 states to decide, suddenly, that it just had to have a state dance.

I dance only in the shower, so have not participated in this particular passion. I am told that the name comes from the beginning placement of couples. Two face each other, let’s say, north and south, and two east and west. In the American version of the dance, a caller calls out instructions to the dancers while the music plays. Apparently without revulsion the couples, for instance, do si do on command.

The square dance has its roots in 16th-century England, though it has become associated most strongly with Western—as in cowboy Western—culture. When the bill to make it the state dance was introduce, Idaho Senator Claire Wetherell, (d for Democrat and Dance) said, “Square dancing is typical of Idaho’s lifestyle.” Well, okay. I’m not sure I can get seven other people in the shower, though.

The National Folk Dance Committee tried to make the square dance the official national dance in 1988, without success. As often happens when something fails on the national level, the group aimed their sites at the states. Idaho couldn’t resist the lobbyists from Big Dance. It became one of 19 states to decide, suddenly, that it just had to have a state dance.

I dance only in the shower, so have not participated in this particular passion. I am told that the name comes from the beginning placement of couples. Two face each other, let’s say, north and south, and two east and west. In the American version of the dance, a caller calls out instructions to the dancers while the music plays. Apparently without revulsion the couples, for instance, do si do on command.

The square dance has its roots in 16th-century England, though it has become associated most strongly with Western—as in cowboy Western—culture. When the bill to make it the state dance was introduce, Idaho Senator Claire Wetherell, (d for Democrat and Dance) said, “Square dancing is typical of Idaho’s lifestyle.” Well, okay. I’m not sure I can get seven other people in the shower, though.

Published on July 29, 2022 04:00

July 28, 2022

The Fortune Teller (Tap to read)

Countless people have tried to find the loot from what is sometimes called the “Robbers’ Roost Holdup,” somewhere between $40,000 and $86,000 worth. Note those were 1865 dollars, which would be worth north of $2 million today. Calculating just where that gold from a stagecoach robbery might be buried has kept many a treasure hunter up at night.

In 1929 there was only one man alive who knew where the gold was. At least, that’s what A.B. Meyer told Agnes Schwabe of McCammon. The original robbery took place not far from McCammon. The 1929 theft took place in Mrs. Schwabe’s house.

Meyer received his unique knowledge by way of clairvoyancy. During a séance he told Mrs. Schwabe all about the hidden loot. She was excited enough to give Meyer the $500 he needed for “excavations.” Once he had the money he took a hurried departure.

The fortune teller, who worked out of Pocatello, was also exceedingly helpful to Mrs. H.C. Lyon Harris of that city. It was fame, not fortune, that lured Mrs. Harris. Meyer promised that he could use his clairvoyancy, somehow, to secure a motion picture contract for her daughter. When the seer skipped with Mrs. Harris’ $250, she joined the complaint of Mrs. Schwabe and an arrest warrant was issued. Meanwhile, Meyer had convinced an American Falls man to give him $200 on the promise of a job at Henry Ford’s marvelous, and fictional, mine in Idaho.

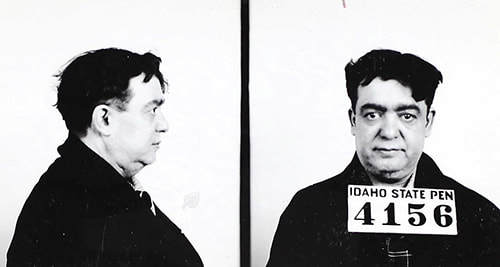

A.B. Meyer, which was actually the alias of Sam Stevens, was caught in Salem, Oregon and brought back to Idaho for trial. Stevens was convicted of fraud and appealed his conviction to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court looked into their crystal ball and envisioned him spending the next 5 to 14 years in prison.

Which he didn’t.

Eighteen months after he entered the Idaho State Penitentiary, Sam Stevens, aka A.B. Meyer, was pardoned by the board of pardons and paroles and told to leave the state and join his wife and child in Colorado.

But he wasn’t quite done with fortune telling.

“Pardoned Prison Clairvoyant Reveals Future for Warden,” read the headline on the front page of the July 9, 1931 Idaho Statesman. Stevens left a note for Warden R.E. Thomas that predicted that Governor C. Ben Ross would be re-elected and that the warden would be reappointed. Ross was re-elected. Thomas was not reappointed. So, batting .500. The note also had something of an apology because Stevens had “a presentiment about Lyda Southard leaving but (was) afraid to reveal it for fear you would think me silly.” Southard had escaped, but that’s another story.

Stevens’ prison records describe him as just short of 5’ 4” and 159 pounds. He was short, “very stout,” with bad teeth and a double chin. His listed occupation was Fortune Teller.

In 1929 there was only one man alive who knew where the gold was. At least, that’s what A.B. Meyer told Agnes Schwabe of McCammon. The original robbery took place not far from McCammon. The 1929 theft took place in Mrs. Schwabe’s house.

Meyer received his unique knowledge by way of clairvoyancy. During a séance he told Mrs. Schwabe all about the hidden loot. She was excited enough to give Meyer the $500 he needed for “excavations.” Once he had the money he took a hurried departure.

The fortune teller, who worked out of Pocatello, was also exceedingly helpful to Mrs. H.C. Lyon Harris of that city. It was fame, not fortune, that lured Mrs. Harris. Meyer promised that he could use his clairvoyancy, somehow, to secure a motion picture contract for her daughter. When the seer skipped with Mrs. Harris’ $250, she joined the complaint of Mrs. Schwabe and an arrest warrant was issued. Meanwhile, Meyer had convinced an American Falls man to give him $200 on the promise of a job at Henry Ford’s marvelous, and fictional, mine in Idaho.

A.B. Meyer, which was actually the alias of Sam Stevens, was caught in Salem, Oregon and brought back to Idaho for trial. Stevens was convicted of fraud and appealed his conviction to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court looked into their crystal ball and envisioned him spending the next 5 to 14 years in prison.

Which he didn’t.

Eighteen months after he entered the Idaho State Penitentiary, Sam Stevens, aka A.B. Meyer, was pardoned by the board of pardons and paroles and told to leave the state and join his wife and child in Colorado.

But he wasn’t quite done with fortune telling.

“Pardoned Prison Clairvoyant Reveals Future for Warden,” read the headline on the front page of the July 9, 1931 Idaho Statesman. Stevens left a note for Warden R.E. Thomas that predicted that Governor C. Ben Ross would be re-elected and that the warden would be reappointed. Ross was re-elected. Thomas was not reappointed. So, batting .500. The note also had something of an apology because Stevens had “a presentiment about Lyda Southard leaving but (was) afraid to reveal it for fear you would think me silly.” Southard had escaped, but that’s another story.

Stevens’ prison records describe him as just short of 5’ 4” and 159 pounds. He was short, “very stout,” with bad teeth and a double chin. His listed occupation was Fortune Teller.

Published on July 28, 2022 04:00

July 27, 2022

A Towering Story (Tap to read)

This is a story of towering historical importance. It is, perhaps, the first not-very-comprehensive account of radio towers in the Treasure Valley. It is the “good parts version” as William Golding would say, of an otherwise grindingly boring technical history that no one ever asked for. You’re welcome.

This abbreviated historical account was prompted by the installation of Idaho’s tallest radio tower. That occurred in December 2018 when KWYD installed a 605-foot tower near the Firebird Raceway to beam “Wild 101.1” into the Treasure Valley. For comparison, that’s nearly twice the height of Idaho’s tallest building, the Zion’s Bank tower in Boise which tops out at 323 feet.

I had recently run across a story about a collapsed radio tower in Boise, so decided to pluck what gems there might have been in the history of local radio towers. Though the KWYD tower going up is news, most of the news about towers occurred when they came down.

I was surprised to learn that the first radio tower story reported by the Idaho Statesman was in the March 20, 1923 issue. That was surprising, because at that time KFAU (which would later become KIDO) was a radio station project at Boise High School and the only station in Idaho. The toppling of that tiny tower would not have made headlines.

The tower that came down in 1923 was one of two huge ham radio towers at the Rawson Ranch about 16 miles southwest of Boise. The 165-foot tower collapsed in a windstorm, leaving a 200-foot tower intact. The ranch was sometimes called the Towers Ranch because H.A. Rawson, a wealthy hog farmer, was an amateur radio buff. When war broke out on April 6, 1917, Rawson was sitting at his receiving table listening to international reports. When he heard the war had begun, he “dragged off his headphones, mounted his motorcycle and was at the state house in 14 minutes” giving the news to state officials.

The next towering story came in 1933 when Nampa’s 106-foot KFXD tower came down in a windstorm.

In 1946, Boise’s third radio station, KGEM, was about to go on the air. Several things delayed the first broadcast, including the collapse of a 100-foot section of tower during construction.

KATN was the next to have tower troubles. In 1970 most of the 205-foot tower which also served sister station KBBK came down in a windstorm.

Then in 1975 one of KBOI’s directional towers crumpled in a storm, though wind was not the entire cause. Static electricity built up and arced across one of the insulators severing a guy wire. That turned the 367-foot tower into twisted metal good only for recycling.

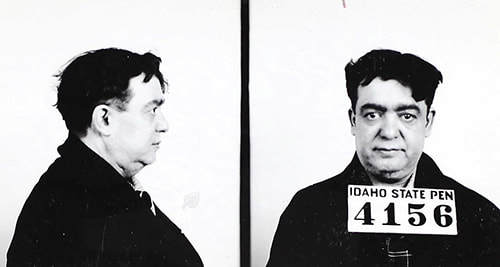

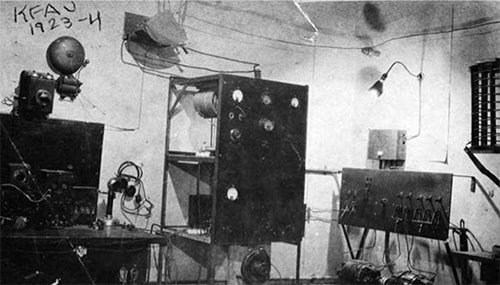

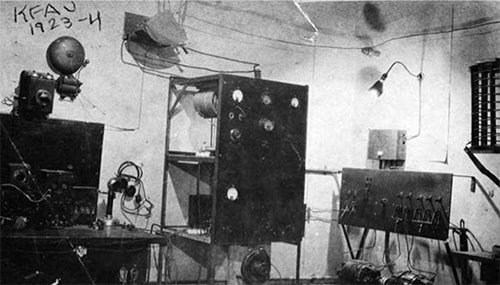

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1922. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1922. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This abbreviated historical account was prompted by the installation of Idaho’s tallest radio tower. That occurred in December 2018 when KWYD installed a 605-foot tower near the Firebird Raceway to beam “Wild 101.1” into the Treasure Valley. For comparison, that’s nearly twice the height of Idaho’s tallest building, the Zion’s Bank tower in Boise which tops out at 323 feet.

I had recently run across a story about a collapsed radio tower in Boise, so decided to pluck what gems there might have been in the history of local radio towers. Though the KWYD tower going up is news, most of the news about towers occurred when they came down.

I was surprised to learn that the first radio tower story reported by the Idaho Statesman was in the March 20, 1923 issue. That was surprising, because at that time KFAU (which would later become KIDO) was a radio station project at Boise High School and the only station in Idaho. The toppling of that tiny tower would not have made headlines.

The tower that came down in 1923 was one of two huge ham radio towers at the Rawson Ranch about 16 miles southwest of Boise. The 165-foot tower collapsed in a windstorm, leaving a 200-foot tower intact. The ranch was sometimes called the Towers Ranch because H.A. Rawson, a wealthy hog farmer, was an amateur radio buff. When war broke out on April 6, 1917, Rawson was sitting at his receiving table listening to international reports. When he heard the war had begun, he “dragged off his headphones, mounted his motorcycle and was at the state house in 14 minutes” giving the news to state officials.

The next towering story came in 1933 when Nampa’s 106-foot KFXD tower came down in a windstorm.

In 1946, Boise’s third radio station, KGEM, was about to go on the air. Several things delayed the first broadcast, including the collapse of a 100-foot section of tower during construction.

KATN was the next to have tower troubles. In 1970 most of the 205-foot tower which also served sister station KBBK came down in a windstorm.

Then in 1975 one of KBOI’s directional towers crumpled in a storm, though wind was not the entire cause. Static electricity built up and arced across one of the insulators severing a guy wire. That turned the 367-foot tower into twisted metal good only for recycling.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1922. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1922. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on July 27, 2022 04:00

July 26, 2022

The Hokey Pokey's Idaho Connection (Tap to read)

“You put your right foot…” And that’s about all you need to get your mind humming the “Hokey Pokey” if you’ve heard it even once. The rest of the song is a simultaneous instruction manual for how to do the dance.

You would think the origins of such a song would be fairly easy to trace. And you’d be right. The trouble is, there are multiple origins.

According to a 2018 article written for “Mental Floss” by Eddie Deezen, there were similar songs popping up all over the world, nearly at the same time. That would be called going viral, today, but this was back in the 1940s. Were all the similar songs original, or had the catchy tune earwormed into the composer’s heads and come out later as their own creations?

There was much haggling among those who had written songs called “The Hoey Oka” (1940) and “The Hokey Cokey” (1942), both published in the United Kingdom. Another composer was entertaining the troops with his “Hokey Pokey” in wartime London.

Those British songs were news to two composers in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1946 when they came out with their dance tune called, “The Hokey Pokey Dance.”

Though similar, none of those songs was quite the one you’ve likely heard. That one came out of Sun Valley, which is why we’re rattling on about a song that you’ve never pulled up on Spotify (note: you could).

Charles Mack, Taft Baker, and Larry Laprise, known as The Sun Valley Trio, played “The Hokey Pokey” for skiers at Sun Valley in 1949. The Scranton composers sued, but Laprise won the court case and the right to claim “The Hokey Pokey” as his.

In 1953, Ray Anthony’s Orchestra recorded and released the version you are likely familiar with.

It went to number 13 on the charts. The flip side was also a hit, called “The Bunny Hop.”

So, there’s a solid Idaho connection to “The Hokey Pokey,” but don’t start moving those celebrating feet yet. There’s more to the story. Even those early 40s versions were about 114 years after the fact. A similar dance with similar instructions was published in 1826 in Robert Chambers' Popular Rhymes of Scotland. Speculation is that the traditional folk dance had been around since the 1700s. The song, or something like it, showed up in 1857 in the United States when a couple of sisters from England were visiting New Hampshire and passed along the steps to locals there. You know the steps. “You put your right foot…”

We don't know what foot these three might have put out first, but there's a solid connection between Sun Valley and The Hokey Pokey.

We don't know what foot these three might have put out first, but there's a solid connection between Sun Valley and The Hokey Pokey.

You would think the origins of such a song would be fairly easy to trace. And you’d be right. The trouble is, there are multiple origins.

According to a 2018 article written for “Mental Floss” by Eddie Deezen, there were similar songs popping up all over the world, nearly at the same time. That would be called going viral, today, but this was back in the 1940s. Were all the similar songs original, or had the catchy tune earwormed into the composer’s heads and come out later as their own creations?

There was much haggling among those who had written songs called “The Hoey Oka” (1940) and “The Hokey Cokey” (1942), both published in the United Kingdom. Another composer was entertaining the troops with his “Hokey Pokey” in wartime London.

Those British songs were news to two composers in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1946 when they came out with their dance tune called, “The Hokey Pokey Dance.”

Though similar, none of those songs was quite the one you’ve likely heard. That one came out of Sun Valley, which is why we’re rattling on about a song that you’ve never pulled up on Spotify (note: you could).

Charles Mack, Taft Baker, and Larry Laprise, known as The Sun Valley Trio, played “The Hokey Pokey” for skiers at Sun Valley in 1949. The Scranton composers sued, but Laprise won the court case and the right to claim “The Hokey Pokey” as his.

In 1953, Ray Anthony’s Orchestra recorded and released the version you are likely familiar with.

It went to number 13 on the charts. The flip side was also a hit, called “The Bunny Hop.”

So, there’s a solid Idaho connection to “The Hokey Pokey,” but don’t start moving those celebrating feet yet. There’s more to the story. Even those early 40s versions were about 114 years after the fact. A similar dance with similar instructions was published in 1826 in Robert Chambers' Popular Rhymes of Scotland. Speculation is that the traditional folk dance had been around since the 1700s. The song, or something like it, showed up in 1857 in the United States when a couple of sisters from England were visiting New Hampshire and passed along the steps to locals there. You know the steps. “You put your right foot…”

We don't know what foot these three might have put out first, but there's a solid connection between Sun Valley and The Hokey Pokey.

We don't know what foot these three might have put out first, but there's a solid connection between Sun Valley and The Hokey Pokey.

Published on July 26, 2022 04:00

July 25, 2022

A Broadcasting Pioneer (Tap to read)

As I wrote a few days ago, KIDO radio is celebrating its 100th year of broadcasting this month. Curtis Phillips, who was one of the original owners, became so associated with Idaho’s first radio station that everyone called him “Kiddo.” Important as he was to broadcasting history in Idaho, I’m going to focus on his partner and wife today. She became a broadcasting legend in her own right.

Georgia Marie Newport was born in Notus, Idaho in 1907. She met Curtis Phillips in Eugene when she was attending the University of Oregon. Phillips was running KORE in Eugene when she stepped in for a piano player performing on the radio with a quartet.

Shortly after they were married, Georgia and Curtis were visiting her parent’s home in Parma. They read that Boise High School student station KFAU was up for auction. They entered a bid and won.

Mr. and Mrs. Phillips made a go of it, moving the new station to ever-better headquarters, first to the top floor of the Boise Elks Lodge, then to the basement of the new Hotel Boise. Later KIDO moved to the mezzanine of the same hotel. The station was such a part of the community that hardly a day went by that it wasn’t mentioned in the newspaper.

C.G. “Kiddo” Phillips died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1942. He was 44. That left his wife, Georgia, to run the radio station and raise two kids. If there was ever any doubt that she was up to the task, she swept that away quickly.

Georgia Phillips became Georgia Davidson in 1946, when she married R. Mowbray Davidson, the owner of Peasley Transfer and Storage. In 1947, she out KIDO FM on the air, one of the state’s earliest FM radio stations. Then, in 1953 the radio pioneer brought television to Idaho. KIDO TV went on the air on July 12, 1953. Its call letters changed to KTVB in 1959 when Davidson sold KIDO radio.

For years Georgia Davidson was the only woman running one of the 120 NBC affiliates across the country. She served as president of the company until 1972 when she became chairman of the board.

Davidson cared about her viewers, not just the business side of television. In 1969, when Sesame Street came on the air, she was determined to include the program on KTVB’s schedule. Running a non-profit program on a commercial TV station didn’t set well with NBC or PBS, but Davidson made it happen. Later, she was instrumental in creating Idaho’s first public television station.

Georgia Davidson passed away in 1997 at age 89.

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Georgia Marie Newport was born in Notus, Idaho in 1907. She met Curtis Phillips in Eugene when she was attending the University of Oregon. Phillips was running KORE in Eugene when she stepped in for a piano player performing on the radio with a quartet.

Shortly after they were married, Georgia and Curtis were visiting her parent’s home in Parma. They read that Boise High School student station KFAU was up for auction. They entered a bid and won.

Mr. and Mrs. Phillips made a go of it, moving the new station to ever-better headquarters, first to the top floor of the Boise Elks Lodge, then to the basement of the new Hotel Boise. Later KIDO moved to the mezzanine of the same hotel. The station was such a part of the community that hardly a day went by that it wasn’t mentioned in the newspaper.

C.G. “Kiddo” Phillips died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1942. He was 44. That left his wife, Georgia, to run the radio station and raise two kids. If there was ever any doubt that she was up to the task, she swept that away quickly.

Georgia Phillips became Georgia Davidson in 1946, when she married R. Mowbray Davidson, the owner of Peasley Transfer and Storage. In 1947, she out KIDO FM on the air, one of the state’s earliest FM radio stations. Then, in 1953 the radio pioneer brought television to Idaho. KIDO TV went on the air on July 12, 1953. Its call letters changed to KTVB in 1959 when Davidson sold KIDO radio.

For years Georgia Davidson was the only woman running one of the 120 NBC affiliates across the country. She served as president of the company until 1972 when she became chairman of the board.

Davidson cared about her viewers, not just the business side of television. In 1969, when Sesame Street came on the air, she was determined to include the program on KTVB’s schedule. Running a non-profit program on a commercial TV station didn’t set well with NBC or PBS, but Davidson made it happen. Later, she was instrumental in creating Idaho’s first public television station.

Georgia Davidson passed away in 1997 at age 89.

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Georgia Davidson. Photo by Ansgur Johnson, courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Published on July 25, 2022 04:00

July 24, 2022

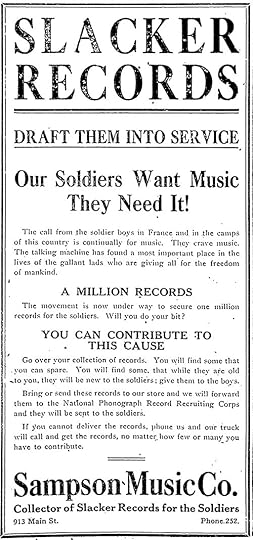

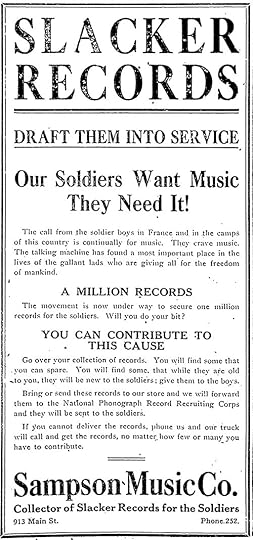

Slacker Records (Tap to read)

In 1918 there was a national effort to collect one million phonograph records for soldiers and sailors serving overseas. Organizers called for communities across the country to collect “slacker records.”

In Boise, the effort was led by C.B. Sampson, the music dealer who had a passion for marking what became known as the Sampson Roads.

Why “slacker”? As the Idaho Statesman article announcing the Boise drive on October 30, 1918 said, “All citizens who have records that have grown old to them are asked to contribute these records.” They were “classed as slacker records inasmuch as they are seldom played in the homes where they have been supplanted by newer records of popular music.”

Sampson started the drive off with a donation of two Victrolas and two dozen records. He also committed to have the records packed and shipped at his own expense. That first article stated that “Music is a war weapon. Army commanders have proved by experience that music is as important to the morale of the army as any single force in the soldier’s life.”

The goal was 1,000 records. On November 5, the drive was 107 records short. The article that day said that, “The donors had apparently gone through their own records, not with the idea that they would give what no longer pleased them, but what they thought would most appeal to the boys.” It ended with the note that the drive would end soon, so it would be “necessary to round up the dilatory records at once.”

The headline on November 11, 1918 read “Boise Responds Liberally in Drive for Canned Music for Boys in France.” The drive had brought in 1281 records valued at $1,102.50.

No doubt Sampson shipped the records off at once, in spite of the headlines the next day announcing that the signing of the armistice with Germany had taken place the very day the results of the slacker record drive were reported.

In Boise, the effort was led by C.B. Sampson, the music dealer who had a passion for marking what became known as the Sampson Roads.

Why “slacker”? As the Idaho Statesman article announcing the Boise drive on October 30, 1918 said, “All citizens who have records that have grown old to them are asked to contribute these records.” They were “classed as slacker records inasmuch as they are seldom played in the homes where they have been supplanted by newer records of popular music.”

Sampson started the drive off with a donation of two Victrolas and two dozen records. He also committed to have the records packed and shipped at his own expense. That first article stated that “Music is a war weapon. Army commanders have proved by experience that music is as important to the morale of the army as any single force in the soldier’s life.”

The goal was 1,000 records. On November 5, the drive was 107 records short. The article that day said that, “The donors had apparently gone through their own records, not with the idea that they would give what no longer pleased them, but what they thought would most appeal to the boys.” It ended with the note that the drive would end soon, so it would be “necessary to round up the dilatory records at once.”

The headline on November 11, 1918 read “Boise Responds Liberally in Drive for Canned Music for Boys in France.” The drive had brought in 1281 records valued at $1,102.50.

No doubt Sampson shipped the records off at once, in spite of the headlines the next day announcing that the signing of the armistice with Germany had taken place the very day the results of the slacker record drive were reported.

Published on July 24, 2022 04:00

July 23, 2022

A Spud Contest (Tap to read)

December 7, 1937. It was a day that would go down in obscurity. Obscurity is practically my middle name, so let’s take a closer look at the news of that day.

The big story on the front page of the Idaho Statesman was that Douglas Van Vlack, convicted of a triple homicide in Twin Falls, was likely to hang for it. In world news Japan was marching on Nanking and police in Kansas City were using tear gas on strikers at the Ford plant.

But those page one stories didn’t bring us here today. It was a page two story that caught my attention. Datelined Washington, the headline read “Maine Accepts Idaho’s Challenge To Showdown Spud Eating Contest.” Idaho’s congressional delegation had challenged the one from Maine to a contest to take place the next day in the House restaurant.

Representative Owen Brewster (R), Maine, demanded a “blindfold test,” saying that “a Maine potato would be humiliated if its eyes saw an Idaho potato in the same oven.” Nasty politics, it seems, are not a recent invention.

Idaho’s potatoes would be served on Tuesday and Maine’s spuds would be on the Wednesday menu. The judges for the contest were to be delegates from Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Alaska. Those were all territories at that time, so their delegates were probably eager to volunteer for any duty.

The gravity of the decision was not lost on the judges. Would it impact their chances for statehood? Who would want to take a chance?

When it came time to show their cards, each of them was blank. The judges had punted. This gave the press an opportunity to call the decision “half-baked.” The speaker of the House, who was from Alabama, took the opportunity to complain that “This was an Irish potato contest. If it were one to decide the potency of the sweet potato the vote would go unanimously for Alabama yams.”

As the Statesman reported, both camps issued bristling post-potato statements. “’It was a raw decision,’ snarled Maine’s Representative Brewster. ‘Anybody ought to be able to tell those potatoes from Aroostook were best.’”

“’Idaho’s are the best in the world,’ barked Idaho’s Representative D. Worth Clark, ‘those judges must have paralyzed palates.’”

After the advertising stunt, the representatives all enjoyed baked potatoes. Idaho got a bill for $52 worth of butter that had to be purchased locally after the Idaho butter that was being flown in failed to arrive.

A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant.

A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant.

The big story on the front page of the Idaho Statesman was that Douglas Van Vlack, convicted of a triple homicide in Twin Falls, was likely to hang for it. In world news Japan was marching on Nanking and police in Kansas City were using tear gas on strikers at the Ford plant.

But those page one stories didn’t bring us here today. It was a page two story that caught my attention. Datelined Washington, the headline read “Maine Accepts Idaho’s Challenge To Showdown Spud Eating Contest.” Idaho’s congressional delegation had challenged the one from Maine to a contest to take place the next day in the House restaurant.

Representative Owen Brewster (R), Maine, demanded a “blindfold test,” saying that “a Maine potato would be humiliated if its eyes saw an Idaho potato in the same oven.” Nasty politics, it seems, are not a recent invention.

Idaho’s potatoes would be served on Tuesday and Maine’s spuds would be on the Wednesday menu. The judges for the contest were to be delegates from Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Alaska. Those were all territories at that time, so their delegates were probably eager to volunteer for any duty.

The gravity of the decision was not lost on the judges. Would it impact their chances for statehood? Who would want to take a chance?

When it came time to show their cards, each of them was blank. The judges had punted. This gave the press an opportunity to call the decision “half-baked.” The speaker of the House, who was from Alabama, took the opportunity to complain that “This was an Irish potato contest. If it were one to decide the potency of the sweet potato the vote would go unanimously for Alabama yams.”

As the Statesman reported, both camps issued bristling post-potato statements. “’It was a raw decision,’ snarled Maine’s Representative Brewster. ‘Anybody ought to be able to tell those potatoes from Aroostook were best.’”

“’Idaho’s are the best in the world,’ barked Idaho’s Representative D. Worth Clark, ‘those judges must have paralyzed palates.’”

After the advertising stunt, the representatives all enjoyed baked potatoes. Idaho got a bill for $52 worth of butter that had to be purchased locally after the Idaho butter that was being flown in failed to arrive.

A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant.

A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant.

Published on July 23, 2022 04:00

July 22, 2022

Initial Point (Tap to read)

Everything has to start somewhere. In surveying terms, Idaho starts 16 miles south of the city of Meridian at a place called Initial Point.

Lafayette Cartee was the first Surveyor General of Idaho Territory, and it was he who established that first point for his survey. The north/south survey line that runs through Initial Point is called the Boise Meridian. One might think that it was a trick of fate that the Boise Meridian is so close to the town of Meridian. If one were a fool. The term Boise Meridian was first, with the town named after it coming along in 1893.

So, if you find an old deed that includes a description with the words Boise Meridian, it doesn’t mean the property is in either Boise or Meridian, only that the description is in relation to that feature of the survey.

Lafayette Cartee was the first Surveyor General of Idaho Territory, and it was he who established that first point for his survey. The north/south survey line that runs through Initial Point is called the Boise Meridian. One might think that it was a trick of fate that the Boise Meridian is so close to the town of Meridian. If one were a fool. The term Boise Meridian was first, with the town named after it coming along in 1893.

So, if you find an old deed that includes a description with the words Boise Meridian, it doesn’t mean the property is in either Boise or Meridian, only that the description is in relation to that feature of the survey.

Published on July 22, 2022 04:00

July 21, 2022

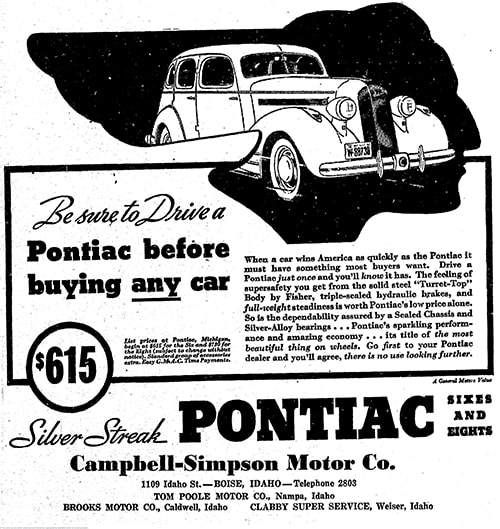

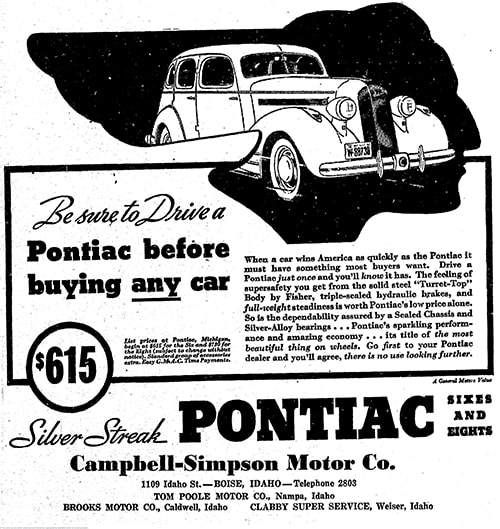

An Idaho Driver's License (Tap to read)

The first mention of a driver’s license for Idahoans that I could find was in an Idaho Statesman editorial on July 8, 1911. The paper was proposing a city driver’s license ordinance after the death of a young girl on the streets. She was killed by a streetcar. The Statesman called for licensing streetcar operators and operators of automobiles, as well.

Boise was behind at least one other Idaho city when it came to licensing. Those driving automobiles in Twin Falls in 1912 were reminded in the Twin Falls Times that they must take out a license to drive. It would cost them $1.

In 1917 the City of Boise passed an ordinance requiring livery drivers to purchase a license. The city council revoked at least a couple of licenses that year, one for drunk driving.

1924 was the first year a bill to require drivers to be licensed came up in the Idaho Legislature. One Statesman headline touted the “Examination of Drivers to Eliminate all Evils.” Requiring drivers to obtain a license was seen as a safety measure, not because they had to take a test, but because the state would then have the ability to take away a license from a driver who proved to be reckless. The bill went nowhere.

In 1927, the idea was back in the Idaho Legislature. National organizations were pushing for universal automobile legislation state by state. Idaho legislators then were about as ready to accept anything that smelled like federal government meddling as they are now. Nada on the driver’s license bill.

By 1928 there were 12 states requiring driver’s licenses. Only five of them required a test to obtain a license. That year the Idaho Statesman ran an article from a national motor club pointing out that “in all too many states, any boy or girl, any deaf person, any insane person at large is allowed to drive.”

The original bill requiring a driver’s license in Idaho, as proposed in 1935, prohibited those who were deaf from driving. The Idaho Association for the Deaf pointed out that many of its members had been driving safely for years. That prohibition was removed.

Meanwhile, the Idaho Statesman had switched sides in the intervening decades. The paper published at least three editorials opposing the bill on the grounds that it was just another way for the state government to take 50 cents or a dollar out of taxpayers’ pockets. “The administration of the act would only mean the establishment of one more bureau to add to the countless others in the state house, more inspectors, more clerks, more examiners to support from the general fund. As a matter of fact, one cannot be blamed for suspecting that this is the reason why many of the politicians like the proposed law.”

Some of those politicians felt the same way. On February 16, 1935, the Statesman reported on debate on S.B. 1, the driver’s license bill. “Senator Clark, Bonneville, tore into the bill with a whirlwind attack in which he said the measure was just one more of the encroachments of bureaucracy on the rights of the common people, just taking a little nick out of the family purse here and there.”

Boise was behind at least one other Idaho city when it came to licensing. Those driving automobiles in Twin Falls in 1912 were reminded in the Twin Falls Times that they must take out a license to drive. It would cost them $1.

In 1917 the City of Boise passed an ordinance requiring livery drivers to purchase a license. The city council revoked at least a couple of licenses that year, one for drunk driving.

1924 was the first year a bill to require drivers to be licensed came up in the Idaho Legislature. One Statesman headline touted the “Examination of Drivers to Eliminate all Evils.” Requiring drivers to obtain a license was seen as a safety measure, not because they had to take a test, but because the state would then have the ability to take away a license from a driver who proved to be reckless. The bill went nowhere.

In 1927, the idea was back in the Idaho Legislature. National organizations were pushing for universal automobile legislation state by state. Idaho legislators then were about as ready to accept anything that smelled like federal government meddling as they are now. Nada on the driver’s license bill.

By 1928 there were 12 states requiring driver’s licenses. Only five of them required a test to obtain a license. That year the Idaho Statesman ran an article from a national motor club pointing out that “in all too many states, any boy or girl, any deaf person, any insane person at large is allowed to drive.”

The original bill requiring a driver’s license in Idaho, as proposed in 1935, prohibited those who were deaf from driving. The Idaho Association for the Deaf pointed out that many of its members had been driving safely for years. That prohibition was removed.

Meanwhile, the Idaho Statesman had switched sides in the intervening decades. The paper published at least three editorials opposing the bill on the grounds that it was just another way for the state government to take 50 cents or a dollar out of taxpayers’ pockets. “The administration of the act would only mean the establishment of one more bureau to add to the countless others in the state house, more inspectors, more clerks, more examiners to support from the general fund. As a matter of fact, one cannot be blamed for suspecting that this is the reason why many of the politicians like the proposed law.”

Some of those politicians felt the same way. On February 16, 1935, the Statesman reported on debate on S.B. 1, the driver’s license bill. “Senator Clark, Bonneville, tore into the bill with a whirlwind attack in which he said the measure was just one more of the encroachments of bureaucracy on the rights of the common people, just taking a little nick out of the family purse here and there.”

Published on July 21, 2022 04:00

July 20, 2022

The Howdy Partner (Tap to read)

At a time when there are Twitter wars over fast food chicken sandwiches let us pause and remember a simpler time when distinguishing one burger joint from another was as simple as putting on staged productions on the roof of a drive-in.

Those simple times were in the 1950s, the go-to decade of simple times. The drive-in trying to sell you burgers was the Howdy Pardner Drive-In, located on Fairview Avenue, kind of kitty-corner from where KTVB is today. In the 50s a parking lot for the Western Idaho Fair was across the street from the drive-in, so advertising mentioned that the establishment was on Highway 30 across from the fairgrounds.

And, they did a lot of advertising, much of it aimed at letting people know what was going on up on the roof (cue the Drifters). That roof extended out over the cars pulled up to order from the curbside menu boards ready to serve drivers. It doubled as a stage for acrobatic artists, a tiny tots style show, 11-year old local TV and radio singer Gene Capps, spring follies, tap dancers, a ballet, the Twisters “teenage jazzmen,” ventriloquists, and the “Miss Howdy Pardner” contests in two divisions, one for those 3-5 years old and the other for girls 3-18. One hundred and fifty students in costume from the Maysco school of dance in Nampa gave a recital on the roof in June, 1955.

The “stage in the air” was well used, mostly on Wednesday and Thursday evenings from 1952 into the late 50s when owner Al Travlestead sold out to Chuck Peterson. Peterson kept the rooftop stage performances going for a few years, but they stopped after Ed Pollard took over the operation in 1962, bringing to an end the “roof shows.”

It was years later that we learned the true reason the Howdy Partner went out of business. Al Travlestead, the marketing genius behind the Show on the Roof, left town in a hurry because he was about to get caught up in the infamous Boys of Boise scandal. For most, this came to light for the first time in the documentary The Fall of ’55. In 2022, Tom Ford and Alex Syiek premiered the musical The Show on the Roof that took a loving look at Travlestead and the Howdy Partner.

Totally gratuitous sidebar: Delene Strawn, 17, Boise, drove into the Howdy Pardner, 5250 Fairview, and knocked her sister, Mrs. Elaine Doris, 18, a curb girl taking a break and seated on a chair, through a plate glass window. Strawn’s brakes apparently failed. Mrs. Doris was treated for cuts and bruises. That the two were sisters was apparently just one of those serendipitous tricks the universe plays on car hops from time to time.

George Ogden shakes hands with “Miss Kay-Gem” in front of the drive-in in 1956. She regularly broadcast from the booth atop the roof. A decade later “Miss Kay-Gem” would be identified as Bernice Beckwith in the Statesman. Comparing the pictures, it seems this lady was an earlier “Miss Kay-Gem.” Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

George Ogden shakes hands with “Miss Kay-Gem” in front of the drive-in in 1956. She regularly broadcast from the booth atop the roof. A decade later “Miss Kay-Gem” would be identified as Bernice Beckwith in the Statesman. Comparing the pictures, it seems this lady was an earlier “Miss Kay-Gem.” Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Those simple times were in the 1950s, the go-to decade of simple times. The drive-in trying to sell you burgers was the Howdy Pardner Drive-In, located on Fairview Avenue, kind of kitty-corner from where KTVB is today. In the 50s a parking lot for the Western Idaho Fair was across the street from the drive-in, so advertising mentioned that the establishment was on Highway 30 across from the fairgrounds.

And, they did a lot of advertising, much of it aimed at letting people know what was going on up on the roof (cue the Drifters). That roof extended out over the cars pulled up to order from the curbside menu boards ready to serve drivers. It doubled as a stage for acrobatic artists, a tiny tots style show, 11-year old local TV and radio singer Gene Capps, spring follies, tap dancers, a ballet, the Twisters “teenage jazzmen,” ventriloquists, and the “Miss Howdy Pardner” contests in two divisions, one for those 3-5 years old and the other for girls 3-18. One hundred and fifty students in costume from the Maysco school of dance in Nampa gave a recital on the roof in June, 1955.

The “stage in the air” was well used, mostly on Wednesday and Thursday evenings from 1952 into the late 50s when owner Al Travlestead sold out to Chuck Peterson. Peterson kept the rooftop stage performances going for a few years, but they stopped after Ed Pollard took over the operation in 1962, bringing to an end the “roof shows.”

It was years later that we learned the true reason the Howdy Partner went out of business. Al Travlestead, the marketing genius behind the Show on the Roof, left town in a hurry because he was about to get caught up in the infamous Boys of Boise scandal. For most, this came to light for the first time in the documentary The Fall of ’55. In 2022, Tom Ford and Alex Syiek premiered the musical The Show on the Roof that took a loving look at Travlestead and the Howdy Partner.

Totally gratuitous sidebar: Delene Strawn, 17, Boise, drove into the Howdy Pardner, 5250 Fairview, and knocked her sister, Mrs. Elaine Doris, 18, a curb girl taking a break and seated on a chair, through a plate glass window. Strawn’s brakes apparently failed. Mrs. Doris was treated for cuts and bruises. That the two were sisters was apparently just one of those serendipitous tricks the universe plays on car hops from time to time.

George Ogden shakes hands with “Miss Kay-Gem” in front of the drive-in in 1956. She regularly broadcast from the booth atop the roof. A decade later “Miss Kay-Gem” would be identified as Bernice Beckwith in the Statesman. Comparing the pictures, it seems this lady was an earlier “Miss Kay-Gem.” Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

George Ogden shakes hands with “Miss Kay-Gem” in front of the drive-in in 1956. She regularly broadcast from the booth atop the roof. A decade later “Miss Kay-Gem” would be identified as Bernice Beckwith in the Statesman. Comparing the pictures, it seems this lady was an earlier “Miss Kay-Gem.” Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on July 20, 2022 04:00