Rick Just's Blog, page 89

July 19, 2022

Dugout Dick (Tap to read)

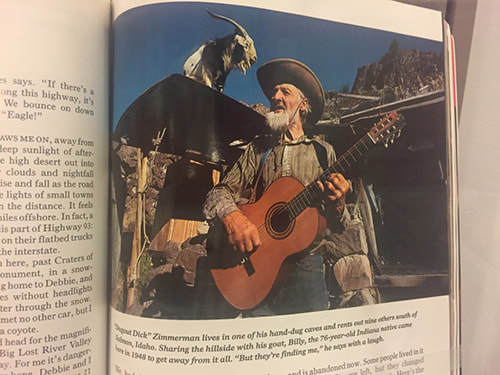

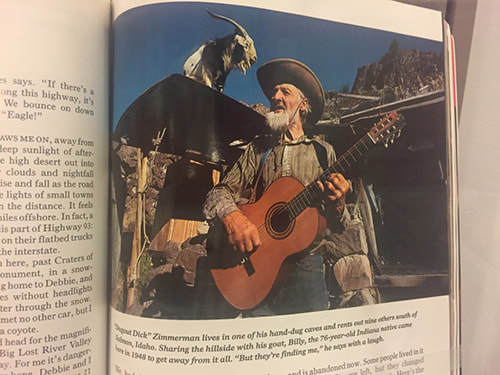

Dick Zimmerman’s story was in National Geographic and Life Magazine. He got an invitation to appear on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show and turned it down. His obituary was in the Wall Street Journal. So how did Zimmerman end up getting all that publicity and more? Well, for the latter, he had to die, but not just anyone who stops breathing makes the cut.

What Dick Zimmerman did was live in something like a cave alongside Idaho’s Salmon River.

Zimmerman had ridden the rails for a few years, bouncing around the country and working odd jobs when, at age 32, he decided to become a hermit. There may be no better place to do that than Idaho. He picked a boulder strewn slope along the river about 20 miles south of the city of Salmon.

He made himself a home by moving rocks around and forming boulder and shale walls tucked back into a rockslide with a log front. The four-room rock-sheltered house featured a natural refrigerator in back, taking advantage of a vein of ice that had formed over the centuries beneath the talus slope.

Zimmerman decided to make a little money by building more dugouts in the rocks and renting them out to people who wanted the experience of sleeping in a cave in Idaho’s backcountry. Against common sense, there was no shortage of such people.

Eventually, Zimmerman earned the name “Dugout Dick” for his 20 some rental properties scattered up and down the hillside, none of which would likely make the grade for Air B n B. He used whatever building materials he could scrounge, old tires, worn out carpeting, pieces of siding from an abandoned trailer. Floors were often concrete overlaid with linoleum scraps. Each had a wood stove and a bed or two. For windows he used scrap glass, even car windshields. The roofs were typically rough-cut logs topped with scraps of siding and carpeting and covered with sod. You could have the experience of sleeping in one of those hand-built dugouts for a couple of dollars a night, with a discount if you wanted to stay for 30 days. To get a sense of what the rentals were like, check this little YouTube podcast.

Dugout Dick married once in 1968. He met his wife through a lonely-hearts club. They corresponded, got hitched, and she came to live with him along the Salmon. She didn’t take to the life and eventually drifted away. Zimmerman later had a girlfriend from Idaho Falls, according to Cort Conley’s Idaho Loners . She spent time with Dick off and on, but came to a sad ending, murdered by her roommate in town.

Dugout Dick was less of a hermit than one might suppose. He went to town regularly, traveled a little, and didn’t live a life all that secluded. You could throw a rock from his home in the hillside across the river and nearly hit highway 93. Still, his odd lifestyle made him famous. A Scandinavian company did a documentary about the man. The magazine stories drew the curious to his “caves.”

Dick’s home, and the rentals he built, were on land under the purview of the Bureau of Land Management. While he was alive, they tolerated the ramshackle little town he had built on and in the hillside. After his death at age 94 in 2010 the BLM took down all but one of his constructions. Today there is an interpretive sign near that old dugout.

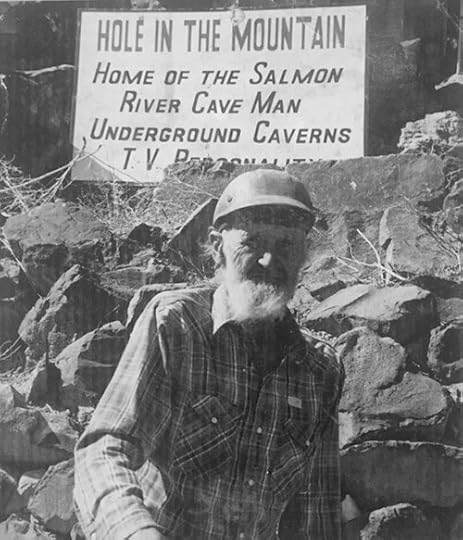

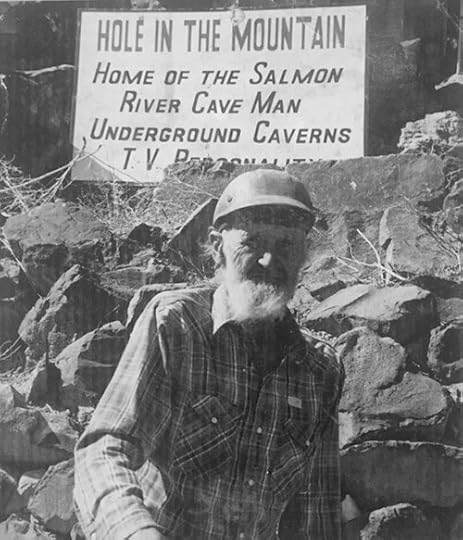

Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”

Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”  Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

What Dick Zimmerman did was live in something like a cave alongside Idaho’s Salmon River.

Zimmerman had ridden the rails for a few years, bouncing around the country and working odd jobs when, at age 32, he decided to become a hermit. There may be no better place to do that than Idaho. He picked a boulder strewn slope along the river about 20 miles south of the city of Salmon.

He made himself a home by moving rocks around and forming boulder and shale walls tucked back into a rockslide with a log front. The four-room rock-sheltered house featured a natural refrigerator in back, taking advantage of a vein of ice that had formed over the centuries beneath the talus slope.

Zimmerman decided to make a little money by building more dugouts in the rocks and renting them out to people who wanted the experience of sleeping in a cave in Idaho’s backcountry. Against common sense, there was no shortage of such people.

Eventually, Zimmerman earned the name “Dugout Dick” for his 20 some rental properties scattered up and down the hillside, none of which would likely make the grade for Air B n B. He used whatever building materials he could scrounge, old tires, worn out carpeting, pieces of siding from an abandoned trailer. Floors were often concrete overlaid with linoleum scraps. Each had a wood stove and a bed or two. For windows he used scrap glass, even car windshields. The roofs were typically rough-cut logs topped with scraps of siding and carpeting and covered with sod. You could have the experience of sleeping in one of those hand-built dugouts for a couple of dollars a night, with a discount if you wanted to stay for 30 days. To get a sense of what the rentals were like, check this little YouTube podcast.

Dugout Dick married once in 1968. He met his wife through a lonely-hearts club. They corresponded, got hitched, and she came to live with him along the Salmon. She didn’t take to the life and eventually drifted away. Zimmerman later had a girlfriend from Idaho Falls, according to Cort Conley’s Idaho Loners . She spent time with Dick off and on, but came to a sad ending, murdered by her roommate in town.

Dugout Dick was less of a hermit than one might suppose. He went to town regularly, traveled a little, and didn’t live a life all that secluded. You could throw a rock from his home in the hillside across the river and nearly hit highway 93. Still, his odd lifestyle made him famous. A Scandinavian company did a documentary about the man. The magazine stories drew the curious to his “caves.”

Dick’s home, and the rentals he built, were on land under the purview of the Bureau of Land Management. While he was alive, they tolerated the ramshackle little town he had built on and in the hillside. After his death at age 94 in 2010 the BLM took down all but one of his constructions. Today there is an interpretive sign near that old dugout.

Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”

Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”  Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Published on July 19, 2022 04:00

July 18, 2022

Radio Centennial (Tap to read)

Idaho marks the 100th anniversary of broadcasting this month, though there is some debate about whether the date to celebrate is July 18 or July 20. Stay tuned for the explanation.

The story of radio in Idaho began in September 1917 when Harry Redeker was hired as a chemistry and physics teacher at Boise High School. In the evenings, he taught Morse Code to young men who were about to head into the maw of World War I.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

Student radio station KFAU received its license on July 18, 1922—the date the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation marks as the official start of broadcasting in the state—though the first official broadcast didn’t begin until July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support, the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU to become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station at that time, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the station’s fate, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September 1928, the school district sold KFAU to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kiddo.”

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School is long gone. Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc. for their help on this story. KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.

KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.

Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc.

The story of radio in Idaho began in September 1917 when Harry Redeker was hired as a chemistry and physics teacher at Boise High School. In the evenings, he taught Morse Code to young men who were about to head into the maw of World War I.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

Student radio station KFAU received its license on July 18, 1922—the date the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation marks as the official start of broadcasting in the state—though the first official broadcast didn’t begin until July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support, the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU to become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station at that time, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the station’s fate, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September 1928, the school district sold KFAU to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kiddo.”

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School is long gone. Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc. for their help on this story.

KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.

KIDO’s chief engineer, Harold Toedtemeier, operates the controls atop the overhang on the Hotel Boise while announcer Roy Civille conducts an interview on the street. The picture was taken sometime after 1937. That was the year KIDO became an NBC affiliate. Boise’s first radio station moved out of the Hotel Boise in 1949.Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation Inc.

Published on July 18, 2022 04:00

July 17, 2022

The Boise Songs (Tap to read)

There is, perhaps, no quicker way to set a long-time resident of Boise’s teeth to grinding than to call the town “Boy-zee.” If you don’t pronounce it “Boy-see,” slap yourself in the face with your iPad right now.

Even so, audiences usually overlook the faux pas when the star on stage panders out to the audience, “Hello, Boy-zee!” Unless, of course, they happen to be on stage in Pocatello at the time.

In the summer of 2010, Jewel played at Outlaw Field in Boise and endeared herself to the audience, in spite of a couple of false starts, by singing a newly penned title, The Boise Song . The lyrics list letters you can find in the names of certain cities, i.e., an A in Atlanta, a Y in Kansas City, etc., but ending each verse with “But there is no Z in Boise.”

You can easily find it with Google, but if you missed that concert, you might never hear her perform it live, unless she comes back to Idaho. According to setlist.com, which covers concert statistics, Jewel has performed it just that one time in public.

If you do a search for Boise in the lyrics of songs you’ll come up with about 50 occurrences. Many are versions of the same song brought out on different albums. Most are obscure.

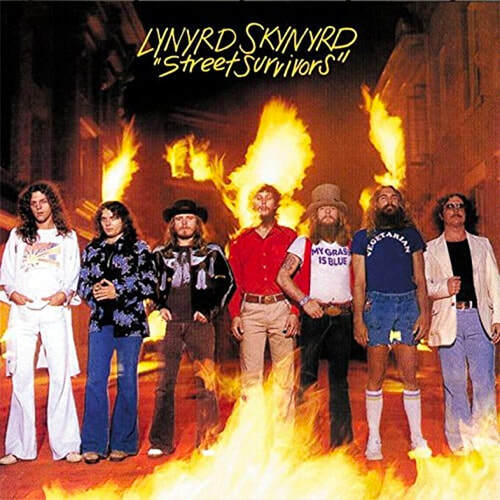

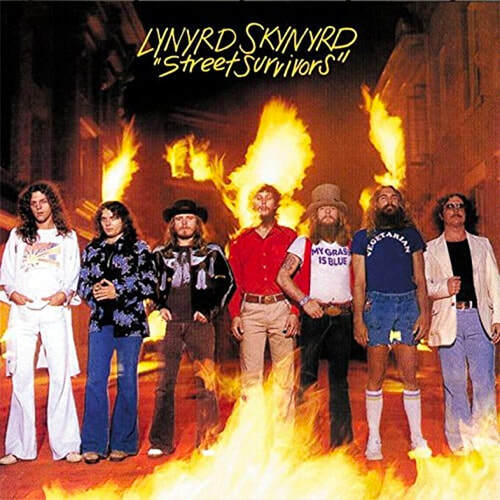

What’s Your Name by Lynyrd Skynyrd made a big splash with the opening line, “It’s 8 o’clock in Boy-zee, Idaho,” released in 1977. According to songfacts.com the original line to that song was “It’s 8 o’clock and boys it’s time to go.” Ronnie Van Zant’s brother, Don Van Zant was opening the national tour of his band .38 Special in Boise. Ronnie, who wrote the song, changed the line to fit the venue. Three days after the album containing the song was released, three members of Lynyrd Skynyrd, including Ronnie Van Zant, were killed in a plane crash. What’s Your Name, peaked on the Billboard chart at number 13 in March, 1978, probably making it the most popular song containing a reference to the state. It appeared on nine Lynyrd Skynyrd albums.

Boise popped up in the lyrics to a Harry Chapin song, WOLD.” Those were the call letters of the Boise radio station where the singer/DJ had hit rock bottom. As a former Boise DJ, I probably resent the implication. Chapin ignored the fact that all radio station call letters west of the Mississippi begin with a K. In the east, you’ll find W call letters, with the exception of KDKA in Pittsburgh. But I digress. Oh, the song made it to number 34 on the Hot One Hundred.

Drake (featuring Lil Wayne and Andre 3000) mentioned Boise, obliquely, in the 2011 song, The Real Her . It was a little hat-tip to the Blue Turf. The word was a little on the fence Z-S-wise but would probably make a native smile.

Even so, audiences usually overlook the faux pas when the star on stage panders out to the audience, “Hello, Boy-zee!” Unless, of course, they happen to be on stage in Pocatello at the time.

In the summer of 2010, Jewel played at Outlaw Field in Boise and endeared herself to the audience, in spite of a couple of false starts, by singing a newly penned title, The Boise Song . The lyrics list letters you can find in the names of certain cities, i.e., an A in Atlanta, a Y in Kansas City, etc., but ending each verse with “But there is no Z in Boise.”

You can easily find it with Google, but if you missed that concert, you might never hear her perform it live, unless she comes back to Idaho. According to setlist.com, which covers concert statistics, Jewel has performed it just that one time in public.

If you do a search for Boise in the lyrics of songs you’ll come up with about 50 occurrences. Many are versions of the same song brought out on different albums. Most are obscure.

What’s Your Name by Lynyrd Skynyrd made a big splash with the opening line, “It’s 8 o’clock in Boy-zee, Idaho,” released in 1977. According to songfacts.com the original line to that song was “It’s 8 o’clock and boys it’s time to go.” Ronnie Van Zant’s brother, Don Van Zant was opening the national tour of his band .38 Special in Boise. Ronnie, who wrote the song, changed the line to fit the venue. Three days after the album containing the song was released, three members of Lynyrd Skynyrd, including Ronnie Van Zant, were killed in a plane crash. What’s Your Name, peaked on the Billboard chart at number 13 in March, 1978, probably making it the most popular song containing a reference to the state. It appeared on nine Lynyrd Skynyrd albums.

Boise popped up in the lyrics to a Harry Chapin song, WOLD.” Those were the call letters of the Boise radio station where the singer/DJ had hit rock bottom. As a former Boise DJ, I probably resent the implication. Chapin ignored the fact that all radio station call letters west of the Mississippi begin with a K. In the east, you’ll find W call letters, with the exception of KDKA in Pittsburgh. But I digress. Oh, the song made it to number 34 on the Hot One Hundred.

Drake (featuring Lil Wayne and Andre 3000) mentioned Boise, obliquely, in the 2011 song, The Real Her . It was a little hat-tip to the Blue Turf. The word was a little on the fence Z-S-wise but would probably make a native smile.

Published on July 17, 2022 04:00

July 16, 2022

A Double Hanging (Tap to read)

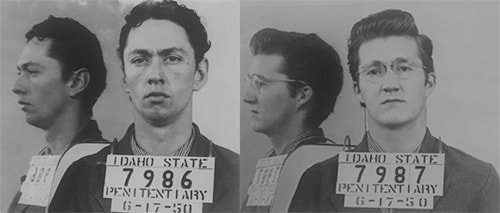

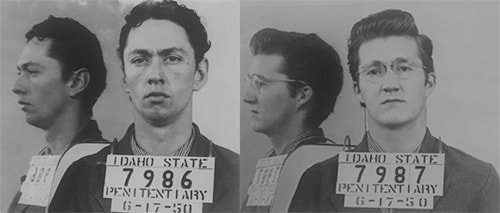

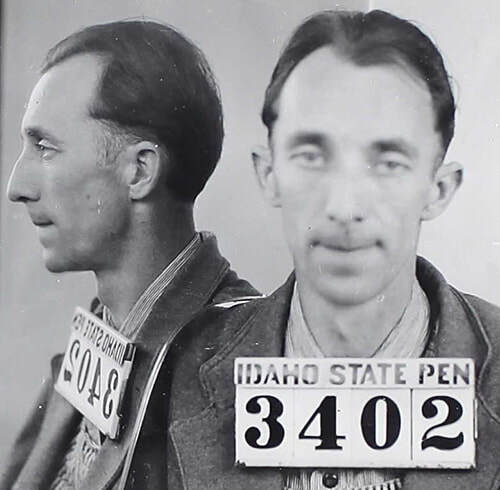

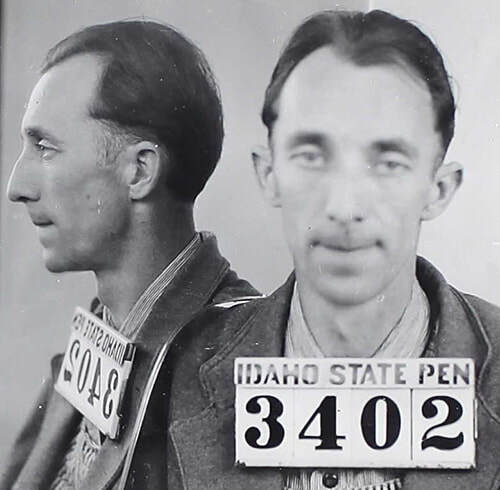

Friday the 13th is thought by some to be an unlucky day. That was certainly the case for Ernie Walrath. 21, and Troy Powell, 20, when Friday, April 13 1951 rolled around. That was the day the two young men met their end in a double hanging at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Justice was swift in the murder of Boise Grocer Newton Wilson. He was killed on May 8, 1950 behind his small store at 1401 E State Street, a couple of doors down from the home of Troy Powell. Walrath and Powell were arrested six hours after the murder, and by June 16 had pleaded guilty to bludgeoning and stabbing the man to death in a botched robbery. The next day they were sentenced to hang.

Having little to appeal, attorneys for the pair petitioned the Idaho Supreme Court to commute their sentences on the grounds that the State Pardon Board was illegally constituted and lacked a member who was a psychiatrist. The court didn’t buy the last-minute arguments.

When Powell and Wilson died on that Friday the 13th in 1951, it was the first hanging in Idaho since 1926. It was also the only double hanging ever carried out in the state.

The mugshots of Tony Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho.

The mugshots of Tony Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho.

Justice was swift in the murder of Boise Grocer Newton Wilson. He was killed on May 8, 1950 behind his small store at 1401 E State Street, a couple of doors down from the home of Troy Powell. Walrath and Powell were arrested six hours after the murder, and by June 16 had pleaded guilty to bludgeoning and stabbing the man to death in a botched robbery. The next day they were sentenced to hang.

Having little to appeal, attorneys for the pair petitioned the Idaho Supreme Court to commute their sentences on the grounds that the State Pardon Board was illegally constituted and lacked a member who was a psychiatrist. The court didn’t buy the last-minute arguments.

When Powell and Wilson died on that Friday the 13th in 1951, it was the first hanging in Idaho since 1926. It was also the only double hanging ever carried out in the state.

The mugshots of Tony Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho.

The mugshots of Tony Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho.

Published on July 16, 2022 04:00

July 15, 2022

Crash (Tap to read)

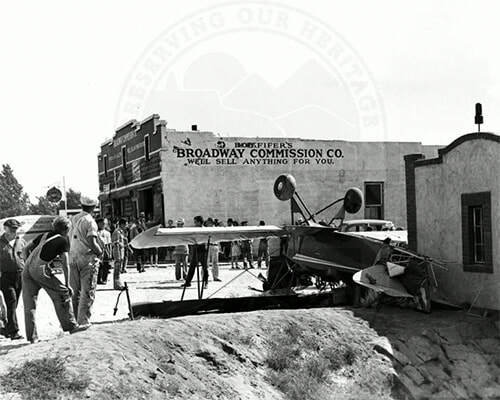

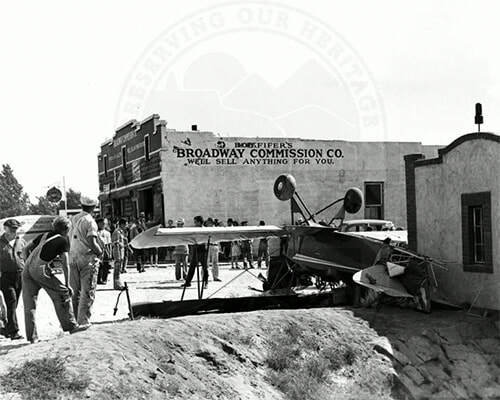

Imagine the embarrassment of being the state aeronautics director and crashing your plane into a building in the capital city. Now, imagine the added awkwardness of doing the same thing with a federal flying inspector on board. Okay, now imagine that you’d been introduced to Boise a week earlier in the local paper as the new state aeronautics director who, by the way, had taught Charles Lindberg to fly.

That’s what happened to W.H. “Pete” Hill on July 13, 1939. Hill, with inspector Robert Gardner in the back seat of a new open biplane, was attempting a spiral landing at the old Boise Airport where BSU is now located. A spiral or corkscrew landing is often performed when a pilot is hoping to avoid anti-aircraft fire coming into an airport. It became SOP, for instance, when landing at Baghdad International after a cargo plane was struck by a surface-to-air missile a few years ago.

Why was Hill performing this particular type of landing? News accounts don’t say. They do say that he essentially ran out of sky toward the end, coming in too low over one of the buildings on Broadway near the airport. Hill gunned the plane to get some altitude, but the landing gear hit the top of the front wall of the Broadway Commission building, sheared off an airport warning light, somersaulted into a row of mailboxes, and landed upside down in the street.

Both men had some injuries, Hill’s the worst. He had a fractured pelvis and a hurt shoulder. The inspector had a broken toe along with scrapes and bruises.

Whether or not the crash was an early blight on Hill’s record as the state director of aeronautics is open to speculation. He lasted in the position a couple of years.

This Fleet two-seat biplane made the front page of the Statesman on July 14, 1939. Miraculously both of the men aboard the plane when it crashed survived. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This Fleet two-seat biplane made the front page of the Statesman on July 14, 1939. Miraculously both of the men aboard the plane when it crashed survived. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

That’s what happened to W.H. “Pete” Hill on July 13, 1939. Hill, with inspector Robert Gardner in the back seat of a new open biplane, was attempting a spiral landing at the old Boise Airport where BSU is now located. A spiral or corkscrew landing is often performed when a pilot is hoping to avoid anti-aircraft fire coming into an airport. It became SOP, for instance, when landing at Baghdad International after a cargo plane was struck by a surface-to-air missile a few years ago.

Why was Hill performing this particular type of landing? News accounts don’t say. They do say that he essentially ran out of sky toward the end, coming in too low over one of the buildings on Broadway near the airport. Hill gunned the plane to get some altitude, but the landing gear hit the top of the front wall of the Broadway Commission building, sheared off an airport warning light, somersaulted into a row of mailboxes, and landed upside down in the street.

Both men had some injuries, Hill’s the worst. He had a fractured pelvis and a hurt shoulder. The inspector had a broken toe along with scrapes and bruises.

Whether or not the crash was an early blight on Hill’s record as the state director of aeronautics is open to speculation. He lasted in the position a couple of years.

This Fleet two-seat biplane made the front page of the Statesman on July 14, 1939. Miraculously both of the men aboard the plane when it crashed survived. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This Fleet two-seat biplane made the front page of the Statesman on July 14, 1939. Miraculously both of the men aboard the plane when it crashed survived. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on July 15, 2022 04:00

July 14, 2022

Boxcar and the Beatles (Tap to read)

An Associated Press story that ran in the August 4, 1966 Idaho Statesman, began, “A campaign to ‘ban the Beatles,’ the mop-haired quartet that harnessed the screams and cheers of teen-agers to make millions, spread rapidly from its Southern base across the nation, Wednesday.”

It’s a good bet that KGEM radio personality Marty Martin read that story. The very next day the Statesman had an article headlined “Bonfire Set For Beatles Near Boise.” They probably used that “Near Boise” line because “in Garden City” wouldn’t fit in the space they had for the headline.

But let’s back up. Why was anyone burning records by the Beatles? It was because John Lennon had been quoted in a British magazine interview as saying the group was “more popular than Jesus.” The quote didn’t raise a stir in the UK, but the Beatles were headed to the US for a nationwide tour. A Birmingham, Alabama radio station started the “burn the Beatles” movement and it quickly caught on, even in Boise. Um, Garden City.

Marty Martin’s record-burning session was to take place during a remote broadcast at Mica Trailer Sales in Garden City. Free hotdogs were more common at remotes than record burnings, but one changes with the times.

Fifty Boise teens showed up to pitch their records into Martin’s fire. The first to do so was Billy Cutshaw. She received a replacement LP from Martin who had offered less controversial vinyl in exchange for every Beatles record thrown onto the fire. They were probably country western records, as KGEM wasn’t playing music by the Beatles in the first place.

So, what happened next? Well, as everyone knows the Beatles went down in flames never to be heard from again. Oh, wait. That wasn’t in this dimension. Here on earth the Beatles sold several more records and changed the course of rock and roll history.

What also happened, many years later, is that John Lennon was murdered by a crazed gunman reportedly in part because of that 1966 remark.

Marty Martin went on to have a highly successful recording career of his own under his stage name, Boxcar Willie.

It’s a good bet that KGEM radio personality Marty Martin read that story. The very next day the Statesman had an article headlined “Bonfire Set For Beatles Near Boise.” They probably used that “Near Boise” line because “in Garden City” wouldn’t fit in the space they had for the headline.

But let’s back up. Why was anyone burning records by the Beatles? It was because John Lennon had been quoted in a British magazine interview as saying the group was “more popular than Jesus.” The quote didn’t raise a stir in the UK, but the Beatles were headed to the US for a nationwide tour. A Birmingham, Alabama radio station started the “burn the Beatles” movement and it quickly caught on, even in Boise. Um, Garden City.

Marty Martin’s record-burning session was to take place during a remote broadcast at Mica Trailer Sales in Garden City. Free hotdogs were more common at remotes than record burnings, but one changes with the times.

Fifty Boise teens showed up to pitch their records into Martin’s fire. The first to do so was Billy Cutshaw. She received a replacement LP from Martin who had offered less controversial vinyl in exchange for every Beatles record thrown onto the fire. They were probably country western records, as KGEM wasn’t playing music by the Beatles in the first place.

So, what happened next? Well, as everyone knows the Beatles went down in flames never to be heard from again. Oh, wait. That wasn’t in this dimension. Here on earth the Beatles sold several more records and changed the course of rock and roll history.

What also happened, many years later, is that John Lennon was murdered by a crazed gunman reportedly in part because of that 1966 remark.

Marty Martin went on to have a highly successful recording career of his own under his stage name, Boxcar Willie.

Published on July 14, 2022 04:00

July 13, 2022

Arley Latham (Tap to read)

Countless men from lands far away came to Idaho to seek their fortune in the late 19th and early 20th century. Such was the case with two men from Austria, Dan Eliuk and Fred Kobyluik. They came to the Gem State in 1924 by way of Utah. While mining near Park City they met a young man from Idaho who said that he could get them jobs working on a ranch near his hometown of Carey. It sounded good to the Austrians, so they withdrew their savings from a local bank, piled in Kobyluik’s car with the Idaho native, and set out for a western adventure.

On their way to Carey the three stayed overnight at a hotel in Paul. Dan Eliuk would later say that he had noticed the young man who had promised them jobs sign his name as I. Hart on the guest register. That was a little strange, because his name was Arley Latham, a name that would soon be infamous.

The next day Latham had them stop the car near the boundary of Craters of the Moon which had become a national monument just a couple of weeks earlier on June 15. The terrain was black rocks and blacker rocks and crevices with more rocks scattered around. Even so, Latham told Dan Eliuk to stay with the car while he and Kobyluik headed out on foot just a short distance to the ranch which was over a little rise of lava rocks.

With Eliuk waiting behind them the men set out across the rugged landscape, soon disappearing over the ridge. About 15 minutes later Eliuk heard three shots. Not long after Latham came back to get him, saying that Kobyluik had gone on ahead to the ranch and would meet them there. What about the shots? Rabbits, said Latham.

So, Dan and Arley—I’m using first names now because I’m tired typing those Austrian surnames—set out for the ranch. When they got there Fred wasn’t in evidence. Neither was the ranch manager. The two made themselves at home and waited for someone to show up.

The night passed without the arrival of anyone else. Arley seemed unconcerned and suggested a walk in the lavas to Dan. He declined. How about a trip to Fish Lake? Dan wasn’t interested. Dan was interested only in finding a phone, which he did. He called authorities in Hailey and told them about the worrisome disappearance of his partner.

A search party was put together. Arley joined the men in the search for Fred. When they found no sign of the man, Arley suddenly changed his story. He said that Dan had killed Fred. That seemed a little too convenient to the sheriff. He and a deputy questioned Arley vigorously, resulting in another story coming forth.

Arley Latham had planned all along to murder Fred, the man with the cash. When they were out of sight of Dan and the car, he shot Fred in the back. Fred turned toward Arley who shot him in the left eye and a third time in the chest. Now, it should have been a simple thing to lean over and remove the dead man’s wallet. This was Craters of the Moon, though. When Fred fell, he fell into one of thousands of cracks in the lava rock. He fell in such a way as to solidly wedge the wallet between his body and the wall of the crevice.

Latham was able to stretch his arm down into the crack in the lava and rip the dead man’s clothing enough that he got $5 for his efforts. He gave up and kicked some rocks over the body so it would be more difficult to see, then went back to the car to retrieve Dan.

Arley Latham confessed to the sheriff and to the editor of the Arco Advertiser, C.A. Bottolfsen, saying he had planned to kill both of the Austrians and make off with their car and money. They were foreigners. Who would miss them?

Justice was swift. The murder had taken place on July 1. Latham was arrested and confessed late on July 2. He was in prison on August 8, serving a sentence of 25 years to life for the murder of Fred Kobyluik.

But Latham would stay in prison only 16 years, ultimately to be set free by one of the men he had confessed to. C.A. Bottolfsen had become governor. He pardoned Latham not because the justice system had made a mistake, but because Arley Latham was dying from tuberculosis. He was released on the 13th of November 1940 on the recommendation of the prison doctor who said he didn’t have long to live.

The story could end there, all of us assuming that Latham passed away unnoticed shortly after his release. Actually, he married not long after his release, in February 1942. He was soon divorced and remarried in 1948. That marriage lasted until 1958. Latham passed away in Boise in 1963 at the age of 60. What he did for a living during the 23 years after his release is unknown. In the obituary for Latham’s father it mentioned a grandchild. Since Latham was an only child it seems likely the grandchild was the offspring from one of his marriages.

Latham is buried at the Dry Creek Cemetery in Boise. Fred Kobyluik’s body was retrieved from the crevice by the county coroner and buried a short distance away.

Arley Latham

Arley Latham

On their way to Carey the three stayed overnight at a hotel in Paul. Dan Eliuk would later say that he had noticed the young man who had promised them jobs sign his name as I. Hart on the guest register. That was a little strange, because his name was Arley Latham, a name that would soon be infamous.

The next day Latham had them stop the car near the boundary of Craters of the Moon which had become a national monument just a couple of weeks earlier on June 15. The terrain was black rocks and blacker rocks and crevices with more rocks scattered around. Even so, Latham told Dan Eliuk to stay with the car while he and Kobyluik headed out on foot just a short distance to the ranch which was over a little rise of lava rocks.

With Eliuk waiting behind them the men set out across the rugged landscape, soon disappearing over the ridge. About 15 minutes later Eliuk heard three shots. Not long after Latham came back to get him, saying that Kobyluik had gone on ahead to the ranch and would meet them there. What about the shots? Rabbits, said Latham.

So, Dan and Arley—I’m using first names now because I’m tired typing those Austrian surnames—set out for the ranch. When they got there Fred wasn’t in evidence. Neither was the ranch manager. The two made themselves at home and waited for someone to show up.

The night passed without the arrival of anyone else. Arley seemed unconcerned and suggested a walk in the lavas to Dan. He declined. How about a trip to Fish Lake? Dan wasn’t interested. Dan was interested only in finding a phone, which he did. He called authorities in Hailey and told them about the worrisome disappearance of his partner.

A search party was put together. Arley joined the men in the search for Fred. When they found no sign of the man, Arley suddenly changed his story. He said that Dan had killed Fred. That seemed a little too convenient to the sheriff. He and a deputy questioned Arley vigorously, resulting in another story coming forth.

Arley Latham had planned all along to murder Fred, the man with the cash. When they were out of sight of Dan and the car, he shot Fred in the back. Fred turned toward Arley who shot him in the left eye and a third time in the chest. Now, it should have been a simple thing to lean over and remove the dead man’s wallet. This was Craters of the Moon, though. When Fred fell, he fell into one of thousands of cracks in the lava rock. He fell in such a way as to solidly wedge the wallet between his body and the wall of the crevice.

Latham was able to stretch his arm down into the crack in the lava and rip the dead man’s clothing enough that he got $5 for his efforts. He gave up and kicked some rocks over the body so it would be more difficult to see, then went back to the car to retrieve Dan.

Arley Latham confessed to the sheriff and to the editor of the Arco Advertiser, C.A. Bottolfsen, saying he had planned to kill both of the Austrians and make off with their car and money. They were foreigners. Who would miss them?

Justice was swift. The murder had taken place on July 1. Latham was arrested and confessed late on July 2. He was in prison on August 8, serving a sentence of 25 years to life for the murder of Fred Kobyluik.

But Latham would stay in prison only 16 years, ultimately to be set free by one of the men he had confessed to. C.A. Bottolfsen had become governor. He pardoned Latham not because the justice system had made a mistake, but because Arley Latham was dying from tuberculosis. He was released on the 13th of November 1940 on the recommendation of the prison doctor who said he didn’t have long to live.

The story could end there, all of us assuming that Latham passed away unnoticed shortly after his release. Actually, he married not long after his release, in February 1942. He was soon divorced and remarried in 1948. That marriage lasted until 1958. Latham passed away in Boise in 1963 at the age of 60. What he did for a living during the 23 years after his release is unknown. In the obituary for Latham’s father it mentioned a grandchild. Since Latham was an only child it seems likely the grandchild was the offspring from one of his marriages.

Latham is buried at the Dry Creek Cemetery in Boise. Fred Kobyluik’s body was retrieved from the crevice by the county coroner and buried a short distance away.

Arley Latham

Arley Latham

Published on July 13, 2022 04:00

July 12, 2022

Naming Craigmont (Tap to read)

I recently posted a piece about William Craig, the first white settler in what became Idaho. Because of his prominence a couple of things have been named in his honor. The most prominent is the Craig Mountain Plateau, that high country that stretches between the Snake, Salmon, and Clearwater rivers, and Craig Mountain or Craig Mountains.

Craigmont, Idaho is also named after William Craig, but has a longer naming history according to Lalia Boone, who wrote Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary. Part of Craigmont started out as Chicago, Idaho in 1898, then became known as Ilo. Ilo was on one side of the railroad tracks, while the town of Vollmer, incorporated in 1906, was on the other side. Populated largely by human beings, the towns were, of course, bitter rivals for a time. They came together in 1920 under the name of Craigmont.

Craig Creek, which empties into the Clearwater River, is named after a different Craig. George W. Craig settled on the creek in 1905.

Craigmont, Idaho is also named after William Craig, but has a longer naming history according to Lalia Boone, who wrote Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary. Part of Craigmont started out as Chicago, Idaho in 1898, then became known as Ilo. Ilo was on one side of the railroad tracks, while the town of Vollmer, incorporated in 1906, was on the other side. Populated largely by human beings, the towns were, of course, bitter rivals for a time. They came together in 1920 under the name of Craigmont.

Craig Creek, which empties into the Clearwater River, is named after a different Craig. George W. Craig settled on the creek in 1905.

Published on July 12, 2022 04:00

July 11, 2022

Idaho's Muffler Men (Tap to read)

You’d think a 25-foot-tall man born in 1967 would have enough documentation behind him to have his story told accurately, wouldn’t you?

Not so with the lumberjack that stands at 1405 Main Avenue in St. Maries. You’ll see stories about him that say he’s standing in front of the High School, where the sports teams are called the Lumberjacks. Well, the high school isn’t far away, but he’s really on the lawn of an elementary school. And, is he standing? He’s not sitting, but he also doesn’t have feet, so…

Often, you’ll see the lumberjack referred to as Paul Bunyan. He’s really a generic lumberjack. He’s also a Muffler Man.

What? It turns out that giant Fiberglass men are referred to in general as “Muffler Men.” The St. Maries man is holding an axe, but many of the early giants held mufflers in their hands to advertise automotive service shops. The vast majority of them were made in California by International Fiberglass, a boat builder, beginning in 1962. The first “Muffler Man” was actually a lumberjack. Specifically, it was a Paul Bunyan statue used to advertise a restaurant in Arizona on Route 66.

Thousands of them were made over the years from the same mold, but with some variations. They were cheap—$1,000 to $3,000—and they caught your attention. They held all kinds of jobs, promoting gas stations, restaurants, and roadside attractions. They were dressed as Vikings, football players, astronauts, pirates, soldiers, chefs, and cowboys. There’s a cowboy along the interstate near Wendell holding a stop sign in his hands, hoping you’ll stop by an RV dealership.

The third known Muffler Man in Idaho has a cushy job. He doesn’t even have to stand outside in the weather. Big Don, as he’s known, towers inside Pocatello’s Museum of Clean, where he wields a giant mop. Needless to say, he’s spotless. Word is that he has a cowboy hat, too, but he doesn’t wear it indoors.

But back to that lumberjack. Although he’s generically a Muffler Man, he’s specifically a Texaco “Big Friendly.” There were originally some 500 of them, but only a half dozen exist today. He’s a little taller than the average Muffler Man, although there’s the issue of the feet. There’s a story that says he arrived with his feet on backwards so those were chopped off and he was mounted in concrete. There’s also a rumor that the lumberjack fell off a truck or was found in the woods.

Wherever the St. Maries lumberjack came from, he’s not the only one of his kind in Idaho. His brothers in Wendell and Pocatello also have at least one sister in the state, a Jackie Kennedy Onassis lookalike in Blackfoot. Her name is Martha and she advertises Martha’s Café. She was “born” a Uniroyal Gal. There are maybe a dozen of them left around the country. Martha is conservatively dressed, but she originally hit the streets wearing a bikini.

Alert readers who are certain there’s another Muffler Man or woman in the state are requested to send photographic evidence of same. Maybe we’ll put together a reunion.

The "muffler man" in St. Maries.

The "muffler man" in St. Maries.  The "muffler man" at the Museum of Clean in Pocatello.

The "muffler man" at the Museum of Clean in Pocatello.

Not so with the lumberjack that stands at 1405 Main Avenue in St. Maries. You’ll see stories about him that say he’s standing in front of the High School, where the sports teams are called the Lumberjacks. Well, the high school isn’t far away, but he’s really on the lawn of an elementary school. And, is he standing? He’s not sitting, but he also doesn’t have feet, so…

Often, you’ll see the lumberjack referred to as Paul Bunyan. He’s really a generic lumberjack. He’s also a Muffler Man.

What? It turns out that giant Fiberglass men are referred to in general as “Muffler Men.” The St. Maries man is holding an axe, but many of the early giants held mufflers in their hands to advertise automotive service shops. The vast majority of them were made in California by International Fiberglass, a boat builder, beginning in 1962. The first “Muffler Man” was actually a lumberjack. Specifically, it was a Paul Bunyan statue used to advertise a restaurant in Arizona on Route 66.

Thousands of them were made over the years from the same mold, but with some variations. They were cheap—$1,000 to $3,000—and they caught your attention. They held all kinds of jobs, promoting gas stations, restaurants, and roadside attractions. They were dressed as Vikings, football players, astronauts, pirates, soldiers, chefs, and cowboys. There’s a cowboy along the interstate near Wendell holding a stop sign in his hands, hoping you’ll stop by an RV dealership.

The third known Muffler Man in Idaho has a cushy job. He doesn’t even have to stand outside in the weather. Big Don, as he’s known, towers inside Pocatello’s Museum of Clean, where he wields a giant mop. Needless to say, he’s spotless. Word is that he has a cowboy hat, too, but he doesn’t wear it indoors.

But back to that lumberjack. Although he’s generically a Muffler Man, he’s specifically a Texaco “Big Friendly.” There were originally some 500 of them, but only a half dozen exist today. He’s a little taller than the average Muffler Man, although there’s the issue of the feet. There’s a story that says he arrived with his feet on backwards so those were chopped off and he was mounted in concrete. There’s also a rumor that the lumberjack fell off a truck or was found in the woods.

Wherever the St. Maries lumberjack came from, he’s not the only one of his kind in Idaho. His brothers in Wendell and Pocatello also have at least one sister in the state, a Jackie Kennedy Onassis lookalike in Blackfoot. Her name is Martha and she advertises Martha’s Café. She was “born” a Uniroyal Gal. There are maybe a dozen of them left around the country. Martha is conservatively dressed, but she originally hit the streets wearing a bikini.

Alert readers who are certain there’s another Muffler Man or woman in the state are requested to send photographic evidence of same. Maybe we’ll put together a reunion.

The "muffler man" in St. Maries.

The "muffler man" in St. Maries.  The "muffler man" at the Museum of Clean in Pocatello.

The "muffler man" at the Museum of Clean in Pocatello.

Published on July 11, 2022 04:00

July 10, 2022

Jane Timothy Silcott (Tap to read)

If you’re looking for that one moment when Idaho began, you could do worse than picking the second the sun first glinted off a speck of gold in the pan of W.F. Bassett in August of 1860. But let’s not give all credit to that one man, one among a handful of prospectors who might have come up with that three-cents-worth of ore that marked the beginning of the gold rush in what is today Northern Idaho. Let’s step back and honor the woman who led the men there to seek their fortune in the first place. That woman was Jane Timothy, 18-year-old daughter of Chief Timothy who the Nez Perce knew better as Ta-moot-sin.

Jane was known by many names among those in her tribe, Princess Like the Fawn, Princess Like the Dove, Princess Like Running Water, according to L.E. Bragg’s book, Idaho’s Remarkable Women . Jane’s uncle was Old Chief Joseph, so she was a cousin of the Chief Joseph who outwitted the military time after time in 1877.

But this was before that time. It was a time when, by treaty, whites weren’t allowed on the Nez Perce reservation without permission. Many of the Tribe were adamant about not letting white men into their home lands, but Chief Timothy had long been a friend of the whites.

So, when Elias D. Pierce approached the chief about helping him find his way into the back country to search for gold, Chief Timothy was amenable. Timothy knew that other tribal members had told Pierce and his party of six to turn back more than once and that they were watching the party with suspicion. He reasoned that they were also watching Timothy’s men to make sure they did not help Pierce.

There was a roundabout way to get into the country Pierce wanted to explore. They would need someone who knew the trail well. With the men being closely watched, who could serve as guide to the Pierce party? Jane spoke up. She knew the trail as well as anyone and volunteered to show the prospectors the way.

Pierce and his men made a show of beginning a trek by turning back east away from the reservation. At night, they doubled back and met up with Jane who lead them to the trail. She was stealthy, taking the men on a parallel path so that no one would find any sign of their passage. They traveled at night and listened to Jane when she told them how to move silently through the brush to avoid detection.

Jane “knew every hill and stream, every mountain meadow and possible camping place; almost she knew the very trees,” wrote W.A. Goulder, an early pioneer, in his 1909 Reminiscences.

Once word got out about the find on Orofino Creek (named such for the “fine gold” panned there), prospectors came to the country in numbers too large for the Nez Perce to deal with. They were overwhelmed by the inevitable rush.

There is little doubt the Pierce party would not have made it to what would become the townsite of Pierce without the help of Jane Timothy. Pierce, who had an elevated opinion of his own prowess in all things, failed to mention her at all in his writings. He noted that, “We procured a guide who was familiar with the country.” That it has been Wilbur Bassett who found the first sparkle of gold also went un-noted by Pierce.

Jane Timothy met and married the Harvard-educated John Silcott not long after leading the Pierce Party to their historical find. They would later operate the first commercial ferry across the Clearwater.

Jane was known by many names among those in her tribe, Princess Like the Fawn, Princess Like the Dove, Princess Like Running Water, according to L.E. Bragg’s book, Idaho’s Remarkable Women . Jane’s uncle was Old Chief Joseph, so she was a cousin of the Chief Joseph who outwitted the military time after time in 1877.

But this was before that time. It was a time when, by treaty, whites weren’t allowed on the Nez Perce reservation without permission. Many of the Tribe were adamant about not letting white men into their home lands, but Chief Timothy had long been a friend of the whites.

So, when Elias D. Pierce approached the chief about helping him find his way into the back country to search for gold, Chief Timothy was amenable. Timothy knew that other tribal members had told Pierce and his party of six to turn back more than once and that they were watching the party with suspicion. He reasoned that they were also watching Timothy’s men to make sure they did not help Pierce.

There was a roundabout way to get into the country Pierce wanted to explore. They would need someone who knew the trail well. With the men being closely watched, who could serve as guide to the Pierce party? Jane spoke up. She knew the trail as well as anyone and volunteered to show the prospectors the way.

Pierce and his men made a show of beginning a trek by turning back east away from the reservation. At night, they doubled back and met up with Jane who lead them to the trail. She was stealthy, taking the men on a parallel path so that no one would find any sign of their passage. They traveled at night and listened to Jane when she told them how to move silently through the brush to avoid detection.

Jane “knew every hill and stream, every mountain meadow and possible camping place; almost she knew the very trees,” wrote W.A. Goulder, an early pioneer, in his 1909 Reminiscences.

Once word got out about the find on Orofino Creek (named such for the “fine gold” panned there), prospectors came to the country in numbers too large for the Nez Perce to deal with. They were overwhelmed by the inevitable rush.

There is little doubt the Pierce party would not have made it to what would become the townsite of Pierce without the help of Jane Timothy. Pierce, who had an elevated opinion of his own prowess in all things, failed to mention her at all in his writings. He noted that, “We procured a guide who was familiar with the country.” That it has been Wilbur Bassett who found the first sparkle of gold also went un-noted by Pierce.

Jane Timothy met and married the Harvard-educated John Silcott not long after leading the Pierce Party to their historical find. They would later operate the first commercial ferry across the Clearwater.

Published on July 10, 2022 04:00